- 1Department of Applied Language Studies, Hong Kong Metropolitan University, Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China

- 2Wuhan City Polytechnic, Wuhan, China

This study examines how drama pedagogy supports core competency development among Chinese pre-service teachers, focusing on the mediating and moderating roles of psychological well-being. Grounded in positive psychology and social–emotional learning (SEL), a convergent mixed-methods design combined quantitative analyses (t-tests, structural equation modeling (SEM), and moderated regression) with qualitative focus groups. Participants were vocational college students who were divided into an experimental group receiving a drama-integrated curriculum and a control group with traditional instructions. The results showed that drama pedagogy significantly enhanced communication, collaboration, critical thinking, creativity, and cultural awareness. Psychological well-being fully mediated these effects, while moderation was non-significant. The qualitative findings revealed emotional catharsis, peer support, and embodied collaboration as mechanisms for growth. The study reconceptualizes well-being as an active pedagogical force, highlights the value of mixed methods, and suggests embedding structured drama and well-being support into teacher education. Implications extend beyond China to international debates on arts-based pedagogy.

1 Introduction

Teacher education has increasingly been recognized as a cornerstone of educational reform worldwide. Across diverse systems, the preparation of pre-service teachers is no longer confined to subject knowledge and pedagogical techniques but extends to the cultivation of broader professional competencies. International policy frameworks, such as those advanced by the OECD (Asia Society, 2018) and UNESCO (2021), emphasize competencies in collaboration, critical thinking, creativity, cultural awareness, and social–emotional capacities as foundational for teachers navigating complex, diverse, and rapidly changing classrooms. In this context, teacher education programs are being called to integrate innovative pedagogical approaches that address both cognitive and affective dimensions of learning. Yet the challenge remains: How can pre-service teachers be prepared not only as knowledge transmitters but also as resilient, empathetic, and adaptive professionals?

Drama pedagogy—an umbrella term encompassing process drama, creative drama, and theater-based approaches—has emerged as a promising pathway for addressing this challenge. Building on traditions of experiential and embodied learning, drama-based pedagogy provides opportunities for pre-service teachers to learn through performance, improvisation, and collaborative storytelling (Nicholson, 2015; Flynn, 2025). Studies conducted in various contexts suggest that drama fosters communicative competence, enhances collaborative problem-solving, and strengthens intercultural awareness (Moar et al., 2024). Importantly, it situates learning within embodied, affective, and dialogic experiences, which align closely with the developmental needs of future teachers. Unlike traditional lecture-based methods, drama pedagogy engages the whole person—mind, body, and emotion—creating spaces for both skill acquisition and identity exploration (Sawyer, 2012; Lashley and Nott, 2025). Despite this potential, the precise mechanisms through which drama pedagogy influences teacher competencies remain underexplored, particularly in non-Western contexts.

Internationally, the effectiveness of drama pedagogy in developing key competencies—such as communication, collaboration, creativity, and empathy—has been well established for decades (Neelands, 2009; Sawyer, 2012; Mayer, 1996a). For this reason, the current study does not claim global novelty in confirming the efficacy of drama as a pedagogical tool. Instead, the originality lies in situating drama pedagogy within the Chinese teacher education system, where constructivist and arts-based methods remain marginal compared to more didactic traditions. In this context, drama offers a distinct pathway for bridging the gap between policy expectations of “core competencies” (OECD, 2019) and the reality of classroom practice.

Furthermore, while international research has frequently examined drama pedagogy in relation to cognitive and social skills, few studies have systematically investigated the psychological mechanisms—particularly the role of well-being—that may underlie these outcomes in China. Psychological well-being is especially relevant given the high levels of stress, identity uncertainty, and emotional exhaustion faced by Chinese pre-service teachers (Zhao and Zhang, 2017). Therefore, this study contributes by examining whether well-being mediates or moderates the impact of drama pedagogy on competency development, offering insights into how established global findings may translate into—and be adapted for—distinctive educational cultures.

A growing body of literature has identified psychological well-being as a critical factor shaping teacher effectiveness, resilience, and professional identity. Drawing on frameworks from positive psychology (Seligman, 2011) and multidimensional models of well-being (Ryff, 1989), research demonstrates that teachers with higher well-being are more likely to exhibit adaptive coping, creative engagement, and effective classroom management (Turner et al., 2021; Hascher and Waber, 2021). In pre-service contexts, well-being contributes to the development of confidence, empathy, and reflective capacity, all of which are essential for sustainable professional growth (Törmänen et al., 2022). Recent meta-analyses further confirm that interventions aimed at enhancing social–emotional skills and well-being positively affect both academic performance and interpersonal relationships (Van Pham, 2024). However, well-being has typically been conceptualized as an outcome of educational experiences rather than an active mechanism mediating learning processes. The present study departs from this assumption by examining well-being as a pedagogical bridge—transforming embodied participation in drama into durable competency gains.

Despite advances in arts-based and social–emotional learning (SEL) research, several gaps persist. First, although there is a growing body of international literature on drama pedagogy, relatively few studies have systematically linked its effects to the multidimensional competency frameworks that now guide teacher education worldwide. Much of the evidence remains descriptive, emphasizing positive experiences without fully testing explanatory models (Moar et al., 2024). Second, the mediating and moderating roles of psychological well-being in drama pedagogy remain under-investigated. While a small number of studies have hinted at connections between arts participation, emotional flourishing, and skill acquisition (Fancourt and Finn, 2020; Flynn, 2025), few have explicitly examined whether well-being functions as a mediator (an enabling pathway) or a moderator (a conditional amplifier) in pre-service teacher education. Third, the majority of research originates from Western or high-income contexts, limiting generalizability. Considering that teacher education systems in non-Western contexts face distinct challenges—such as large student populations, exam-driven curricula, and constrained resources—it is vital to investigate how innovative pedagogies operate across diverse cultural environments. China, with its rapidly expanding higher vocational sector and increasing emphasis on competency-based teacher preparation, provides a particularly relevant context for such inquiry.

The present study responds to these gaps by investigating the role of drama pedagogy in fostering core competencies among Chinese pre-service teachers, with particular attention to the mediating and moderating functions of psychological well-being. By adopting a mixed-methods design, the research combines quantitative analyses (structural equation modeling (SEM), moderated regression, and paired sample t-tests) with qualitative insights from focus group interviews. This integration allows not only for the testing of hypothesized pathways but also for a deeper exploration of students’ lived experiences of drama as emotionally liberating, socially connective, and cognitively stimulating. Furthermore, the study situates its contribution within international debates on arts-based pedagogy, SEL, and teacher well-being, thereby strengthening its relevance beyond the Chinese context.

To guide the investigation, two central hypotheses were formulated:

H1 (Mediation Hypothesis): Psychological well-being mediates the relationship between drama pedagogy and core competency development. Specifically, participation in drama-based instruction enhances psychological well-being, which, in turn, promotes improvements in communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and cultural awareness.

H2 (Moderation Hypothesis): The influence of drama pedagogy on competency development is moderated by baseline levels of psychological well-being, such that students with higher initial well-being benefit more strongly from drama participation than those with lower initial well-being.

In testing these hypotheses, the study not only provides empirical evidence on the mechanisms linking drama pedagogy to teacher competencies but also advances the theoretical understanding of well-being as a pedagogical process. At the same time, it provides actionable insights for curriculum designers and policymakers seeking to cultivate more resilient, creative, and socially attuned educators.

2 Literature review

2.1 Drama pedagogy and core competency development

Drama pedagogy, encompassing creative drama, process drama, and theater-in-education approaches, has long been recognized as an effective means of fostering key competencies such as communication, collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, and cultural awareness (Neelands, 2009; Sawyer, 2012). International research has provided extensive evidence that drama-based interventions enhance both cognitive and socio-emotional skills. For instance, Näykki et al. (2024) demonstrated that drama pedagogy strengthened interpersonal communication and creative problem-solving among teacher students. Moar et al. (2024) and Flynn (2025) reported that drama-based modules improved reflective practice, empathy, and cultural competence in the UK and Australian contexts, while Lashley and Nott (2025) showed that embodied role-play supports meta-cognitive awareness and professional identity formation.

However, some critics argue that these benefits are already well established and risk being overstated (Mayer, 1996b). Moreover, such findings predominantly stem from Western, constructivist-oriented systems, leaving unanswered questions about the applicability of drama pedagogy in examination-driven or hierarchical educational contexts, such as China. Recent calls for cross-cultural validation stress the need to examine how drama operates in different cultural environments, where norms of expression, collaboration, and authority may significantly shape students’ engagement (Moar et al., 2024; Flynn, 2025).

2.2 The role of psychological well-being in teacher education

Psychological well-being, conceptualized as a multidimensional construct including autonomy, positive relations, and personal growth (Ryff, 1989), has become central in teacher education research. High levels of well-being are linked to resilience, reflective practice, and sustained professional motivation (Turner et al., 2021; Hascher and Waber, 2021). Recent evidence supports its role as an enabler of learning: Törmänen et al. (2022) found that Finnish teacher students with stronger well-being displayed superior collaboration and self-regulation; Miller (2024) reported that SEL-based curricula promoted resilience and self-efficacy among teacher candidates under stress.

Despite these advances, the role of well-being as a mechanism remains underexplored. While drama and other arts-based interventions have been shown to enhance well-being (Fancourt and Finn, 2020; Flynn, 2025), few studies have examined whether well-being mediates the relationship between pedagogy and competency development, or whether baseline well-being moderates the effects of such interventions. Addressing these questions is essential for understanding how emotional and cognitive dimensions interact in professional growth.

2.3 Integrating quantitative and qualitative evidence

Research on drama pedagogy has often emphasized positive outcomes, yet less attention has been given to divergent or resistant voices. Some students experience discomfort in role-play, skepticism about drama’s professional relevance, or difficulties with group dynamics (Braund, 2015). Such tensions indicate that drama pedagogy is not universally effective and must be understood as context-sensitive. At the same time, reliance on simplified self-report instruments raises concerns about whether complex emotional and relational processes are adequately captured.

To overcome these challenges, scholars recommend integrating quantitative measures with qualitative insights, enabling a more nuanced understanding of affective, embodied, and relational learning processes (Lashley and Nott, 2025). Mixed-methods approaches can illuminate not only measurable gains in competencies but also the lived experiences of participants, including ambivalence and resistance.

Taken together, these strands highlight several gaps that justify the present study. First, most evidence on drama pedagogy originates from Western contexts, with limited attention to Chinese teacher education. Second, the mediating and moderating roles of well-being remain largely untested. Third, few studies employ rigorous mixed-methods designs that capture both statistical patterns and subjective experiences. The present research addresses these gaps by investigating drama pedagogy in China using a convergent mixed-methods design, testing both mediation and moderation models of well-being, and incorporating focus group interviews to reflect diverse perspectives.

3 Significance and contribution

3.1 Theoretical contribution

This study advances theoretical understanding in several ways. First, it reconceptualizes psychological well-being not as a peripheral outcome but as an active pedagogical mechanism that mediates the effect of drama pedagogy on core competencies. While previous research has primarily treated well-being as a consequence of educational interventions (Ryff, 1989; O'Toole and Dunn, 2002), recent international studies suggest a more dynamic role (Seligman, 2011; Noddings, 2005; Moar et al., 2024). The current study provides empirical support for this perspective by demonstrating that drama-based activities foster affective states—emotional catharsis, social connectedness, and reflective engagement—which, in turn, enhance communication, collaboration, creativity, and cultural awareness among pre-service teachers.

Second, the study extends embodied learning and social–emotional learning (SEL) frameworks. While Sawyer (2012) emphasized the cognitive and meta-cognitive dimensions of role-play, and Zins (2004) highlighted the social–emotional aspects of classroom interaction, this research integrates these perspectives to show that drama pedagogy simultaneously engages cognitive, affective, and relational domains. Focus group narratives reveal that students rely on embodied practices—gesture, voice modulation, and movement—to regulate emotions, negotiate group dynamics, and internalize collaborative norms. This supports the notion that core competencies develop through psychosocial mediation rather than direct instruction alone, thereby bridging gaps between theory and observed practice.

Third, the study contributes to the literature by explicitly testing both mediation and moderation mechanisms within a convergent mixed-methods design. Although international studies (Flynn, 2025) have documented positive associations between arts-based pedagogy and teacher well-being, few have employed SEM to quantify indirect effects or examined whether baseline well-being moderates these relationships. By showing full mediation but non-significant moderation, the research clarifies the conditions under which drama pedagogy influences professional competencies and advances theoretical precision in understanding arts-based teacher education.

3.2 Methodological contribution

The study demonstrates methodological innovation in several dimensions. The use of a convergent mixed-methods design (Creswell and Clark, 2017) integrates quantitative rigor with qualitative depth. Quantitatively, structural equation modeling (SEM) with mediation analysis, moderated regression, and paired sample t-tests offers robust evidence on causal pathways and effect sizes. The addition of a control group and a pre-post design align with the strengthening of internal credibility. Diligent reporting of reliability coefficients and model fit indices contributes in favor of measurement transparency.

Broadly, the focus group discussions substantiate the statistical findings by providing an in-depth understanding of the experiential, emotional, and relational components that are key to observed competency progression. By employing reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), the study identifies five interrelated themes: emotional management, emotion control, collaborative empowerment, thriving under pressure, and achievement of resonance. The findings go beyond the boundaries of quantitative methods and demonstrate the subtle ways in which students react to peer pressure or form psychosocial ties, thereby revealing the specific mechanisms.

The model provides a framework for future research that balances the quantitative and qualitative aspects of intervention in healthcare. The evaluation of arts-based pedagogy against international standards is supported through a mixed-methods approach, wherein measured outcomes and lived experiences enhance ecological validity and overcome the limitations commonly associated with self-report instruments.

3.3 Practical and policy contribution

Practically speaking, this study demonstrates practical steps that can be applied by teacher preparation programs. Initially, a core inclusion of structured drama training and modules within the curriculum, as opposed to treating them as extra-curricular activities, should be advocated. This leads not only to improvements in cognitive and social skills, but such programs also focus on the development of emotional intelligence, cultural competence, and professional identity. The research shows that even in the contexts of cultural collectivism, drama can enable the individual voice and intra-group harmony, elements that are essential, hence implying the universality of this mechanism in educational settings.

Such an idea denotes the point of view that mental health issues should be treated as a foundational element in program setup. Institutions can unfold this reflection by embedding mindfulness, reflective writing, and peer conversation within drama pedagogy. By addressing the prevention level of emotional self-regulation, empathy, and resilience, these interventions can be linked to contemporary SEL frameworks (Lawlor, 2016) and provide measurable insights relevant to the employer landscape.

Next, creating networks of peer support alongside a sense of common identity is key to success. The research confirms that mutual roles, shared assessment, peer coaching of the kind, and the overall community of learning help strengthen both motivation and perseverance, thereby fostering the development of resilient groups. Teacher educators can refer to cooperative learning in these dynamics to fuel students’ interest, cultivate self-awareness, and support the development of professional identity.

Finally, the study has implications for culturally responsive pedagogy. Drama-based approaches offer flexible, emotionally adaptive strategies suitable for vocational and teacher education settings where students may face low self-concept or high stress. Symbolic role-play, narrative construction, and expressive freedom can be tailored to specific cultural or institutional contexts, ensuring relevance and impact.

4 Research design

4.1 Research objectives

The main objectives of this study are threefold:

1. To examine the effects of drama pedagogy on the development of core competencies among Chinese pre-service teachers.

2. To investigate the mediating role of psychological well-being in the relationship between drama pedagogy and core competencies.

3. To test whether psychological well-being moderates the relationship between drama pedagogy and competency development.

4.2 Participants and context

Participants were second-year pre-service teachers from a vocational college in China (experimental group: n = 76; control group: n = 84). Sampling combined convenience and purposive methods to ensure that the focus group and survey sample included participants with varied expressive styles and engagement levels. The average age of the participants was 20.3 years (SD = 1.2), with an approximate 1:1 gender ratio. All participants had completed foundational education courses and reported no physical or psychological disabilities.

The experimental group participated in a semester-long teacher education program that integrated drama into the curriculum. Students engaged in activities such as role-play, improvisation, and collaborative storytelling. These activities were incorporated across all aspects of teacher training and were facilitated by instructors trained in the field of drama pedagogy. The control group had normal curriculum schedules. Group assignment was not randomized but based on the existing gaps in classes, and potential selection bias is addressed in the analysis section.

Furthermore, the program was built around the idea of formal peer debriefing at the end of each class, where students could express emotional reactions, write teaching practice experiences, and receive feedback from both instructors and peers. Drama activities were not solely circumscribed by performance but collided with professional practice and reflective discourse through this approach.

4.3 Instruments and measurement validity

1 Core competency scale

The scale consists of 15 items based on the OECD 5C framework—communication, collaboration, critical thinking, creativity, and cultural awareness—adapted to the Chinese teacher education context.

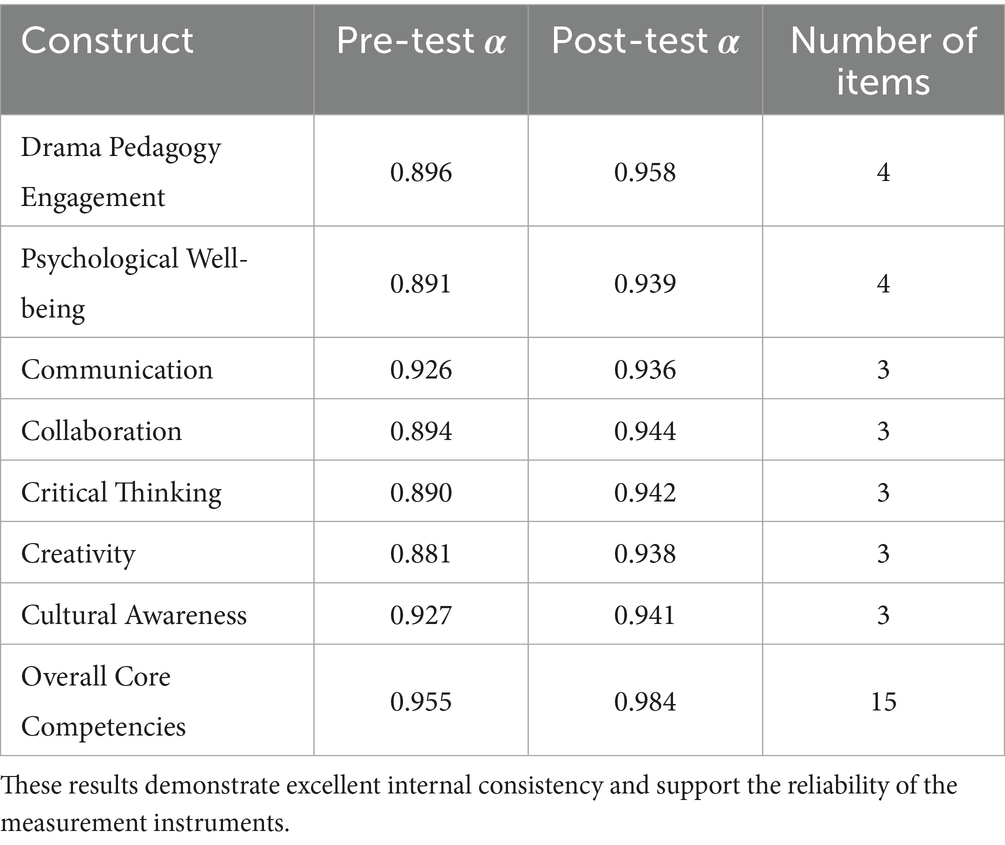

Internal consistency: Cronbach’s α = 0.955 (pre-test), 0.984 (post-test).

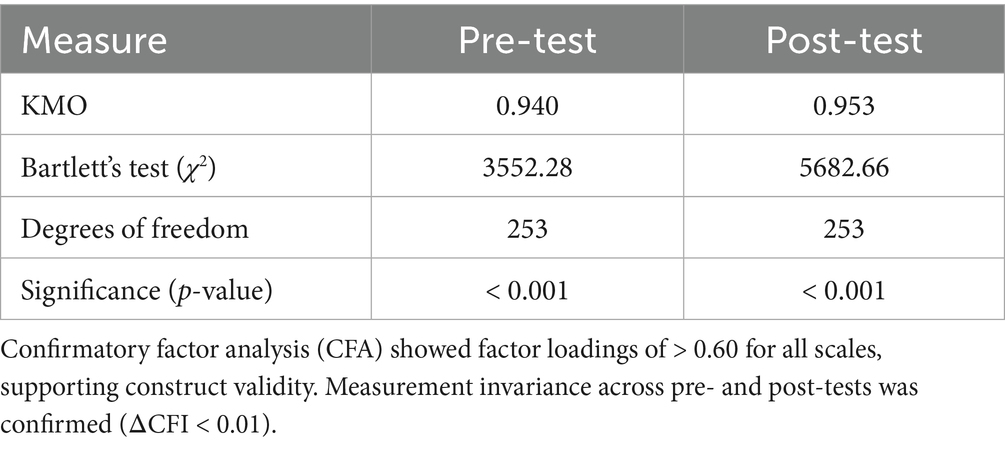

Construct validity: Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) verified the five-dimensional structure, with factor loadings > 0.60. Model fit indices: CFI = 0.962, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.087.

2 Psychological well-being scale

The scale was adapted from Ryff (1989), covering emotional balance, autonomy, and self-efficacy.

Internal consistency: α = 0.891 (pre-test), 0.939 (post-test).

CFA: factor loadings > 0.55; fit indices: CFI = 0.958, TLI = 0.946, RMSEA = 0.092.

3 Drama pedagogy engagement scale

The scale consists of four items assessing emotional immersion, performance engagement, and reflective participation.

Internal consistency: α = 0.896 (pre-test), 0.958 (post-test).

CFA: factor loadings > 0.60; fit indices: CFI = 0.964, TLI = 0.952, RMSEA = 0.089.

4.3.1 Measurement invariance and bias control

Pre- and post-test measurement invariance (configural, metric, scalar) was confirmed (CFI < 0.01), supporting temporal stability.

Common method bias was controlled using Harman’s single-factor test and the common latent factor approach.

4.4 Data collection procedure

A pre-test–post-test design was employed. Quantitative data were collected at the beginning and end of the semester using questionnaires. A focus group of 20 experimental group students was conducted using a semi-structured interview guide, covering emotional expression, teamwork, and mental adaptation. Each session lasted approximately 120 min, was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and anonymized, and consent was obtained. Ethics approval was granted by the institution, and data storage adhered to confidentiality requirements.

4.5 Data analysis

4.5.1 Quantitative analysis

Descriptive statistics, independent samples t-tests, and paired sample t-tests were used to assess changes in core competencies.

SEM (AMOS 24.0) was conducted to test mediation, reporting standardized path coefficients, indirect effects, and 95% bootstrap confidence intervals.

Moderation was analyzed using SPSS 26 PROCESS macro with mean-centered variables and interaction plots.

SEM fit indices: χ2/df = 2.677, CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.103, RMR = 0.013; model fit limitations are discussed.

4.5.2 Qualitative analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) was used inductively, generating five themes: emotional catharsis, emotion regulation, collaborative agency, resilience, and post-performance affective resonance.

Trustworthiness procedures included researcher reflexivity journals, audit trails, and the search for negative cases.

4.5.3 Quantitative–qualitative integration

In the convergent mixed-methods framework, qualitative findings contextualized and explained quantitative results, illustrating how psychological well-being is related to emotional release, peer support, and social interaction.

5 Results

5.1 Descriptive statistics and reliability

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients confirmed high internal consistency for all constructs, consistent with the Chinese data (Table 1).

5.2 Construct validity

The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to confirm suitability for factor analysis (Table 2).

5.3 Group comparisons

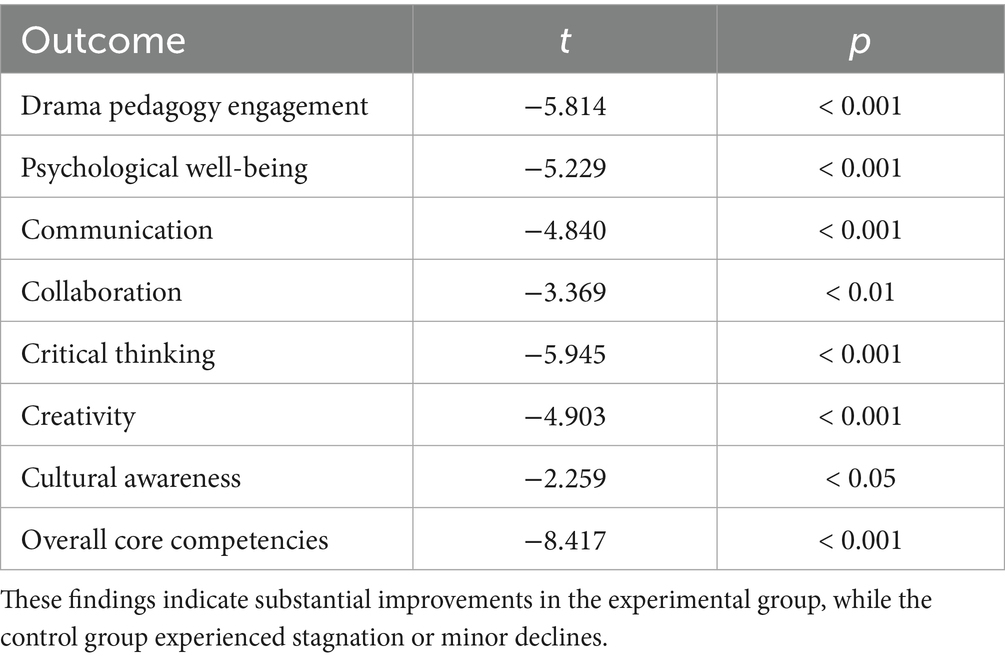

Independent samples t-tests: The experimental group showed significantly higher post-test scores than the control group for cultural awareness and overall competencies.

Paired sample t-tests: Changes from pre-test to post-test in the experimental group were statistically significant (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) (Table 3).

5.4 Mediation analysis

SEM was conducted to assess the hypothesized mediation effect of psychological well-being:

Model fit: χ2/df = 2.677, GFI = 0.860, CFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.959, RMSEA = 0.103, RMR = 0.013.

Path coefficients:

Drama → Well-being: β = 0.935

Well-being → Core Competencies: β = 0.761

Drama → Core Competencies: β = 0.215

Bootstrapped indirect effect (5,000 samples):

Direct effect: 0.202 (ns)

Indirect effect: 0.669 (95% CI: 0.512–0.808)

Total effect: 0.872

The results indicate full mediation, confirming that psychological well-being explains the link between drama pedagogy and competency development.

5.5 Moderation analysis

Moderated regression analysis using PROCESS was employed to assess the interaction of drama pedagogy × psychological well-being:

β = 0.047, p = 0.136 (non-significant)

Model summary: R2 = 0.880, Adjusted R2 = 0.878, F(3,156) = 381.664, p < 0.001

No evidence was found for moderation. Interaction plots confirmed the stability of effects across well-being levels.

5.6 Focus group analysis

To enhance the qualitative findings, focus group interviews were conducted with 20 participants. Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006) identified the converged sub-themes. This is important as it shows both the benefits and the challenges associated with learning through drama.

5.6.1 Emotional catharsis and expressive safety

Drama students have repeatedly described the feeling of being in a safe space where they are able to let their emotions out. It was like putting on a cloak—not for their own sake, but as a way to express emotions that are usually hidden in ordinary learning contexts. In sharing their experiences and feelings, one participant said: “I never talk about my pressure in front of classmates, but acting as another character allowed me to cry and laugh without decision” (Participant 4). Another participant recalled: “It was not just me alone, but I could be somebody else, my own shadow for a moment” (Participant 9). This concept of esthetic distance (Casebier, 1971) supports the idea that playing fictional roles assists in creating a safe space for emotional exploration.

5.6.2 Emotion regulation and interpersonal repair

Both rehearsals and improvisations provided opportunities to share some concerns and tensions, helping to rebuild relationships among group members. Several students reported that initial tensions with group members who did not collaborate were reduced through collaborative performances. “Before I was sad with the teammate, this was the time we were laughing together during rehearsal, so it felt like the conflict was gone” (Participant 11). These examples indicate that theater, applied just like an emotional co-regulation expression (Zaki and Williams, 2013), facilitates reconciliation among group members, fostering collaboration and helping to alleviate stress.

5.6.3 Collaborative agency and social engagement

One challenge the group faced was the fast-paced negotiation of roles and responsibilities, which reduced the students’ sense of ownership within the team. However, several students shared that working in a team became more comfortable for them, although such an experience was rare for them. “Usually, other people are so vocal and dominant in the class, so I keep silence. But when we co-created a story, I noticed, my ideas matter” (Participant 6). “It wasn’t just about me, but as we worked together, making joint contributions, my individual confidence began to strengthen” (Participant 14). Such instances exemplify the capability of drama to stimulate social action and unity.

5.6.4 Resilience and task commitment

Although students began the course by playing what they later realized was a pretty challenging role, many reported that, over time, they learned to be persistent learners, becoming resilient: “The first time was frightening, but I chose to challenge myself. After a few rehearsals, I knew the performance wasn’t so bad” (Participant 2). Others stated that because of the group task, they were unable to quit even when they had the wish to do so: “It was agony to me to do construing to the group, but the group needed me” (Participant 13). These statements emphasize that drama-based tasks foster resilience and frame one’s anxiety as a shared challenge rather than a personal burden.

5.6.5 Affective resonance and post-performance reflection

The performances consistently evoked powerful collective emotions among participants, including enjoyment, cheerfulness, sadness, and remorse. “Once we finished our play, I felt a personal bond to my team. It seemed like we had lived already pretty long together” (Participant 8). The post-play reflections fueled these feelings even more, adding a dimension of career orientation. One participant reflected, “I connected that performance to my ambition for my future work with children.” A classmate declared: “I started wondering how kids feel in class after being nervous and triumphant” (Participant 16). Such realizations point to the fact that shared affective experiences extend beyond performance into everyday life, contributing to the development of identity and empathy.

5.6.6 Integration with quantitative results

The qualitative results add to the quantitative findings by highlighting the psychological processes leveraged in drama pedagogy to support the development of skills. Narratives of purging emotions, student reconciling, and collective attention correspond with the statistical evidence that psychological well-being acts as the mediator of the relationship between drama and skills. Nevertheless, contrasting opinions were also explored. a few expressed skepticism about the long-term benefits of theater-based role-playing: “the games were interesting, but whether they fit in real life teaching is something that remains unclear to me” (participant 15). Similarly, another participant stated, “there were times when I did not take the acting well, and that made me feel ashamed” (participant 18).

While acknowledging opposing views, the paper respectfully presents and values the diversity of participants’ opinions. All things considered, the research indicates that the theatrical guide for educational purposes is effective in promoting mental health and skills, but its impact is not the same for everyone everywhere; it is significantly influenced by classroom environments, group dynamics, and cultural composition.

6 Discussion and theoretical integration

6.1 Integrated summary of the major findings

This study explored the impact of drama pedagogy on the core competency development of pre-service teachers in China, focusing on the mediating role of psychological well-being. Integrating diverse tools of quantitative and qualitative research, the study employed a mixed-methods design that included statistical analyses such as SEM, moderated regression, and paired sample t-tests, along with focus group interviews.

Furthermore, quantitative and qualitative strands supported the contention that learning through the body, feelings, and interactions is at the core of learning in arts-based teacher education. Importantly, the intervention group showed greater progress in integrating soft skills compared to the control group, which remained at baseline levels. However, in the case of the SEM results, where SEM mediated the relationship between psychological well-being and competency development, it must be emphasized that these relationships are only professional conclusions due to the inability of the quasi-experimental design to establish the causal reason behind the associations.

The students described the drama classes as “emotionally liberating” and “socially supportive,” which, in turn, created a culture of communication and an opportunity to collaborate. Recent studies also demonstrate that creative drama has an empathetic, social, and resilience-building effect on teachers, largely supporting the results of this research (Moar et al., 2024; Flynn, 2025). Overall, the data indicate an effective pathway from arts-based pedagogy to professional competence and highlight the requirement for replication of these findings in different contexts.

6.2 Theoretical implications

6.2.1 Reconceptualizing psychological well-being as a pedagogical mechanism

The fact that the moderation effect is negligible implies that such pedagogies could be utilized widely, irrespective of the initial well-being level. This observation emphasizes the strength of drama as an educational approach, but it also calls for further research into the boundary conditions of drama pedagogy, such as sessions or prior arts experience. It is worth mentioning that this is one of the concerns of the international literature, which argues that the amplification of results will not be uniform (Fox et al., 2023).

6.3 Practical implications

Beyond recommending the inclusion of structured drama modules within teacher education, this study emphasizes that drama provides a meaningful space for the holistic development of both professional competencies and psychological well-being, consistent with global frameworks such as STEAM and SEL (Moar et al., 2024; Flynn, 2025). However, the implementation of a comprehensive approach must be gradual and, importantly, context-sensitive, taking into account cultural beliefs, school settings, and global standards.

6.4 Reflexivity and divergent perspectives

Although the overwhelming majority of the respondents looked at drama pedagogy as an enriching and revolutionary experience, it is still necessary to note that the responses can hardly be considered ideal or uniform. A number of learners raised an issue of shyness during the impersonation part of the class, stating that role-playing in front of classmates was embarrassing and not easy. Some questioned the professional significance of drama when teaching schoolchildren, arguing that such playful methods were inappropriate for serious classes. A few participants reported challenges with classroom management, particularly when some students took on leadership roles and actively engaged in group work, while others remained passive.

These criticisms show that drama pedagogy is an approach that may not be readily accepted or easily implemented. It depends on the context, the personality of students being exposed to arts-based learning for the first time, their level of confidence in public performance, and the prevailing culture of learning in the class, which can either promote or inhibit reasonable risk-taking. Instead of merely swaying in favor of one side or the other, we empower ourselves to present a more nature-like, conjectural picture of how and why drama pedagogy takes place in teacher training.

This study also has its limitations when it comes to the self-report scales used, which must be acknowledged from a methodological standpoint. As a matter of fact, the quantitative instruments obtained some trends, but these instruments were not able to capture the depth and complexities of the experiences reflected in the qualitative data. Future studies should combine psychometric measurements with qualitative methods, such as ethnographic observation, peer reports, or even physiological evidence, to enrich learning data and data triangulation.

Therefore, by incorporating the perspectives of people with different backgrounds and being reflexive-minded for all aspects of the process, this study builds up scientific knowledge by proving that drama pedagogy is a promising tool but not a universal remedy. Instead, it is a teaching device that is effective only in some social conditions that can be studied in a broader context.

6.5 Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations of the study that should be acknowledged. First, the quasi-experimental study design and the use of a single-institution sample limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the SEM model showed relatively low CFI and TLI values, while the RMSEA exceeded the acceptable threshold. This suggests potential model misspecification or sensitivity to the small sample size. Future researchers can countercheck the validity of these findings by replicating the model with larger and more diverse populations. Third, because self-report measures are subject to potential bias, future research should employ triangulation with additional methods, such as behavioral observations or physiological indicators. Finally, determining whether well-being continues to function as a mediator in competency development requires a longitudinal research design.

6.6 Concluding remarks

This study contributes to the relevant body of research on arts education pedagogy by illustrating that drama education can lead to significant development in pre-service teachers’ competencies, with psychological well-being as a mediator. The interpretations should be regarded as provisional and suggestive rather than a confirmation of a cause-and-effect relationship. The study underscores that these results are not simply limited to China and can therefore be used in the contexts of other nations’ teacher training programs.

7 Conclusion

Through this research, the vital relationship between drama pedagogy and the development of core competencies in teacher applicants is unveiled, identifying psychological well-being as the key mediating factor. Although the study offers suggestive results, they should still be interpreted with caution, owing to the quasi-experimental nature of the study. The mediation process of psychological well-being was significant, while no moderation effect was found between the groups, suggesting that drama pedagogy had a similar, unclouded effect, irrespective of the extrapolated well-being levels.

This study presents psychological well-being as a vibrant and dynamic force of arts-based education and indicates that it is an active factor of educational outcomes. Its main contribution lies in demonstrating that psychological well-being functions as a mediating mechanism, thereby extending the body of literature on emotional and social learning in pre-service teacher education. In addition, the findings show that the function of drama pedagogy is not limited to intellectual comprehension, but it also implicitly promotes the emotional and relational development of the student, which is key to efficient teaching.

Supporting the points made, international curricular contexts illustrate the value of the transferable results belonging to them. For example, drama in STEAM teacher education programs has been used to allow both creative thinking and social–emotional skills to flourish, as seen in Europe. Such creativity and social–emotional skills are also uncovered in this analysis. In the US, case studies of school-based social–emotional learning programs incorporating drama, as reflected in this research, have demonstrated enhancements in emotional regulation and empathy and strengthened connections between students and teachers (Moar et al., 2024; Flynn, 2025). The international examples mentioned show the applicability of our findings across different education systems around the world, where drama and arts-based learning can be adapted to increase the competence level and well-being of teachers.

Bearing this in mind, we propose that drama modules be more practically integrated into teacher education courses worldwide, with a particular focus on fostering emotional development and peer relations as central elements. Further studies should aim to extend these findings to broader and more diverse student populations and assess the continuing effect that drama pedagogy has on teacher development. On the other hand, additional research is required to identify other potential interveners or operators that may influence the effective implementation of art-based learning programs.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Hong Kong Metropolitan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

YH: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Software, Resources, Validation, Data curation, Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology. JS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1683681/full#supplementary-material

References

Asia Society (2018). Teaching for global competence in a rapidly changing world. France: OECD Publishing.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Braund, M. (2015). Teacher educators’ professional journeys: pedagogical and systemic issues affecting role perceptions. Afr. Educ. Rev. 12, 309–330. doi: 10.1080/18146627.2015.1108010

Creswell, J. W., and Clark, V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. New York: Sage publications.

Fancourt, D., and Finn, S. (2020). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. Copenhagen: WHO.

Flynn, R. M. (2025). Drama as Embodied Learning: Moving from Theory into Action. doi: 10.33682/h9b9-57qu

Fox, H. B., Walter, H. L., and Ball, K. B. (2023). Methods used to evaluate teacher well-being: a systematic review. Psychol. Sch. 60, 4177–4198. doi: 10.1002/pits.22996

Hascher, T., and Waber, J. (2021). Teacher well-being: a systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educ. Res. Rev. 34:100411. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100411

Lashley, M., and Nott, M. (2025). Building arts-based social-emotional learning practices through embodied learning. Wisconsin: WCER.

Lawlor, M. S. (2016). “Mindfulness and social emotional learning (SEL): a conceptual framework” in Handbook of mindfulness in education: Integrating theory and research into practice. eds. K. Schonert-Reichl and R. Roeser (New York, NY: Springer New York), 65–80.

Mayer, R. E. (1996a). Learners as information processors: legacies and limitations of educational psychology's second. Educ. Psychol. 31, 151–161.

Mayer, R. E. (1996b). Learning strategies for making sense out of expository text: the SOI model for guiding three cognitive processes in knowledge construction. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 8, 357–371. doi: 10.1007/BF01463939

Miller, M. (2024). Re-imagining professional development for social and emotional learning: A case study. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia.

Moar, S., Burke, K., and Watson, M. (2024). Teacher perspectives on enhancing wellbeing education through integrating arts-based practices. Br. Educ. Res. J. 50, 2422–2440. doi: 10.1002/berj.4029

Näykki, P., Pyykkönen, S., Latva-aho, J., Nousiainen, T., Ahlström, E., and Toivanen, T. (2024). Pre-service teachers' collaborative learning and role-based drama activity in a virtual reality environment. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 40, 3264–3277. doi: 10.1111/jcal.13079

Neelands, J. (2009). The art of togetherness: reflections on some essential artistic and pedagogic qualities of drama curricula. NJ 33, 9–18. doi: 10.1080/14452294.2009.12089351

Noddings, N. (2005). Identifying and responding to needs in education. Camb. J. Educ. 35, 147–159. doi: 10.1080/03057640500146757

OECD (2019). An OECD learning framework 2030: the future of education and labor. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 23–35.

O'Toole, J., and Dunn, J. (2002). Pretending to learn-helping children learn through drama. Australia: Pearsons.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 57, 1069–1081. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Sawyer, K. (2012). Extending sociocultural theory to group creativity. Vocat. Learn. 5, 59–75. doi: 10.1007/s12186-011-9066-5

Seligman, M. E. P. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. New York: Free Press.

Törmänen, T., Järvenoja, H., Saqr, M., Malmberg, J., and Järvelä, S. (2022). A person-centered approach to study students’ socio-emotional interaction profiles and regulation of collaborative learning. Front. Educ. 7:866612. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.866612

Turner, K., Thielking, M., and Meyer, D. (2021). Teacher wellbeing, teaching practice and student learning. Issues Educ. Res. 31, 1293–1311.

UNESCO (2021). Reimagining our futures together: a new social contract for education. France: UNESCO.

Van Pham, S. (2024). The influence of social and emotional learning on academic performance, emotional well-being, and implementation strategies: a literature review. Saudi J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 9, 381–391. doi: 10.36348/sjhss.2024.v09i12.001

Zaki, J., and Williams, W. C. (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion 13, 803–810. doi: 10.1037/a0033839

Zhao, H., and Zhang, X. (2017). The influence of field teaching practice on pre-service teachers’ professional identity: a mixed methods study. Front. Psychol. 8:1264. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01264

Keywords: drama pedagogy, pre-service teacher education, psychological well-being, core competencies, social–emotional learning, embodied learning, mixed-methods research

Citation: Hu Y and Shu J (2025) Drama pedagogy and the core competency development of pre-service teachers: the mediating and moderating roles of psychological well-being. Front. Educ. 10:1683681. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1683681

Edited by:

Benjamin Dreer-Goethe, University of Erfurt, GermanyReviewed by:

Raquel Flores-Buils, University of Jaume I, SpainMateu Pérez Rosa, University Jaume I. Castellón, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Hu and Shu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yaxin Hu, czEzNTAwMzRAbGl2ZS5oa211LmVkdS5oaw==

Yaxin Hu

Yaxin Hu Jack Shu1

Jack Shu1