- 1Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Amman Arab University, Amman, Jordan

- 2Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Yarmouk University, Amman, Jordan

- 3Yarmouk University, Amman, Jordan

The purpose of the study was to investigate the degree to which language teachers in Jordan t use linguistic artificial intelligence (AI) applications in the teaching process, considering some demographic and professional characteristics. A descriptive analytic methodology was used. The population of the study included all language teachers at the Education Directorate of the Amman District (N = 304). The study sample comprised (128) language teachers from primary and secondary schools. A questionnaire was developed and distributed electronically; 54 of them were retrieved, yielding a response rate of 42.1%. The study tool consisted of (43 items) divided into eight domains: smart electronic educational games applications, augmented reality, smart chatbots, virtual reality, smart evaluation and tests, the Internet of Things, adaptive learning environment applications, and smartphone applications. The study results indicated that the level of use of linguistic artificial intelligence technology applications among language teachers was high, and that there were statistically significant differences in the use of technology applications by language teachers. Linguistic artificial intelligence is attributed to gender differences in favor of females, and the educational stage in favor of primary and secondary school teachers, while there are no statistically significant differences in the use of linguistic artificial intelligence technology applications by language teachers due to differences in academic qualifications or years of experience.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) applications play a vital role in personalizing education by guiding learners based on their individual needs, analyzing big data to improve performance and reduce effort. Research by Faqih (2023) and recommendations from the 2019 AI Conference in Beijing highlight its positive impact on skill development and learning experiences. AI, as described by Salem and Abu Jadayel (2023), mimics human cognitive abilities, making it a foundational technology in modern education. Studies by Farani and Fatani (2020) and Azmy et al. (2014) emphasize the role of smart and expert systems in enhancing teaching processes, simulating real teachers through knowledge-based tools. For instance, Mutair (2022) confirms AI’s role in enriching language education at Yemeni universities, while Hajjiah and Shaib (2020) highlight its strategic advantage in private schools. The effectiveness of AI-powered chatbots for skill development and self-efficacy is supported by several studies like Ardimansyah and Widianto (2021), Abdel-Barr and Abdel-Hamid (2020), and Rashed (2022), which show benefits in skill development and academic self-efficacy. Researchers agree on several AI tools used in education, such as smart content, chatbots, educational games, augmented and virtual reality, IoT, adaptive learning, and smartphone apps (Hajili and Farani, 2022; Huang et al., 2022; Morten, 2018). In language instruction specifically, AI applications enhance teaching and skill development (Shen and Shen, 2020; Nakrin and Rayer Van, 2020), though usage varies across studies. For example, Farani and Fatani (2020) reported low AI use among secondary teachers, while Huwaiti and Bani Ahmad (2022) found high usage among faculty at Princess Noura University. Given these mixed findings, this study investigates the extent to which language teachers across various educational levels employ AI applications, considering the factors that influence their integration.

1.1 Research problem

Based on previous studies recommending expanded research on artificial intelligence (AI) in education (Yajzi, 2019; Abdel-Barr, 2020; Huwaiti and Bani Ahmad, 2022), and supported by findings that show high levels of AI usage among teachers (Hajjiah and Shaib, 2020), including female teachers in public schools (Omari, 2022), and evidence of AI’s effectiveness in language learning environments (Fitria, 2021), there is a clear need to explore AI integration in teaching. Furthermore, this aligns with global educational goals promoting inclusive, quality education and lifelong learning through AI, as emphasized by the G20 principles and international calls for AI to serve humanity (UNESCO, 2019; UNESCO.org, 2021). Despite growing global interest and international summits (e.g., the 2022 World AI Summit) highlighting AI’s potential, a gap remains regarding its application in language instruction, especially given students’ underperformance in international assessments.

Although students use AI tools in daily life, effective integration in education depends primarily on teachers. Therefore, this study investigates the extent to which language teachers use AI-based educational applications such as smart educational games, AI-augmented reality, smart chatbots, virtual reality, intelligent assessment tools, IoT applications, adaptive learning environments, and smartphone apps while considering variables like gender, academic qualifications, teaching level, years of experience, and technology-related training.

1.2 Research questions

• What is the level of use of AI-based educational applications among language teachers?

• What is the perceived importance of using AI-based educational applications from the perspective of language teachers?

• Do variables (gender, academic qualification, educational level, years of teaching experience, and number of training courses in the field of technology) affect language teachers’ use of AI-based educational applications?

1.3 Research objectives

The study aims to investigate the extent of use and the frequency of utilization of AI-based educational applications by language teachers. It also aims to identify the perceived significance of using these applications according to the teachers. Also, the research examines how these factors affect the use of AI-based educational applications by language teachers to a large extent, including gender, academic qualification, educational level and years of teaching experience and the number of training courses in the field of technology.

1.4 The importance of research

The findings of this study are expected to have several practical implications. First, they guide curriculum designers to appreciate the need to integrate applications of artificial intelligence in education in general and learning of languages in particular, since they have proved to facilitate the acquisition of self-directed learning skills among learners. Second, the findings will help the decision-makers identify which AI tools are most frequently used by language teachers, thus allowing them to prioritize and deliver the tools, and devices in the most effective manner. Lastly, the results of the study will be useful to educational stakeholders to recognize the most important variables that define how language teachers utilize AI applications in the classroom that can enable them to develop targeted interventions to enhance these variables and to maximize the application of AI in teaching and learning process.

1.5 Research definitions

1.5.1 Artificial intelligence (AI)

Systems that use technologies that can collect and use data to predict, recommend, or make decisions with varying levels of autonomy, selecting the best course of action to achieve specific goals.

1.5.2 Artificial intelligence applications

Yajzi (2019) defines artificial intelligence (AI) as a broad family of diverse applications aimed at serving humanity, including expert systems, smart learning systems, virtual reality, Internet of Things, intelligent chatbots, and more. In this study, AI systems are designed to simulate human intelligence and rely on various technologies and tools to help English language teachers perform tasks efficiently. These applications encompass smart educational games, AI-powered augmented reality, smart chatbots, virtual reality, smart assessment tools, IoT applications, adaptive learning environments, and smartphone apps.

2 Literature review

This review synthesizes the literature on AI in education according to its thematic approach, (i.e., attention to important areas of its applications and their effects but not references them separately). Given the significant impact of artificial intelligence (AI) applications in education—as demonstrated by studies such as Mutair (2022) and Ghoneim and Elghotmy (2021), it has become essential in learning due to its advanced capabilities in handling massive data and enhancing educational processes. Shahata (2022) defines AI as a science that enables electronic systems to simulate human intelligence, including thinking, decision-making, and task execution. Similarly, Muqatil and Hosni (2021) describe it as a branch of computer science that equips systems with human-like intelligence and behavior.

AI applications possess distinctive features, as highlighted by Shahata (2022) and Kol et al. (2018). These include their ability to support educators, learners, and administrators; operate continuously with high efficiency and accuracy; manage large datasets; and learn and adapt to solve new problems. Specifically, Farani and Fatani (2020) emphasize that using AI in teaching languages creates an engaging, interactive environment that facilitates language acquisition. Additionally, Huang et al. (2022) demonstrate how smart chatbots, a form of AI, can provide a low-anxiety, dialogue-based learning space for practicing languages, along with timely, level-appropriate feedback tailored to learners’ linguistic needs.

Given the multiplicity of educational applications based on AI, the applications used in the current research, and the most important previous related studies, will be highlighted below:

2.1 Smart educational game applications

Artificial intelligence algorithms enhance gameplay by analyzing players’ behavior, adapting skill levels, and automatically adjusting game difficulty accordingly. AI also enables the design of human-like characters, creating more realistic gaming environments. According to Zare (2014), smart games serve as valuable tools for cognitive learning by activating learners’ cognitive processes and developing multiple skills, especially problem-solving, through personalized feedback that improves their performance.

2.2 Virtual reality and augmented reality applications

The use of virtual reality (VR) applications in education fosters active and interactive learning, helping students develop deeper understanding by providing an immersive environment that encourages exploration and independent learning across all educational levels, from kindergarten to secondary and beyond (UNESCO, 2021). Lampropoulos (2023) adds that AI-powered VR integrates virtual and real environments interactively in three dimensions, using sensors and cameras to gather environmental data for a seamless experience.

2.3 Smart chatbots

Subhi (2020) explains that smart chatbots enable interactive communication between users and programs through platforms like messaging apps, websites, and mobile or smart device applications. Learners can engage with chatbots via text, audio, or both to ask subject-related questions, receiving tailored support and advice based on their educational needs. These chatbots operate by leveraging human knowledge across various fields through machine learning and advanced AI technologies.

2.4 Smart assessment and testing applications

Many smart applications are used to assess and evaluate learners’ performance. Studies by Farani and Fatani (2020), Kol et al. (2018), and Faggella (2019) conclude that smart assessment tools and testing applications perform these tasks with high accuracy and efficiency. They offer various methods to solve problems, present questions that identify learners’ weaknesses and mental readiness, and monitor learning strategies, ultimately supporting students’ academic excellence and enabling informed decision-making by educational authorities.

2.5 Internet of Things applications

The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to a group of devices connected via the Internet wirelessly through sensors that can interact, send and receive data from the surrounding environment (Dahshan, 2019). It is a network of devices capable of interacting with the surrounding environment, in addition to collecting and analyzing data. These technologies are used in the field of education in various aspects, including developing services, managing smart classrooms and classrooms, and recording the automatic attendance of students and faculty. The results of Younis’s study Younis (2022) revealed positive attitudes among faculty members toward the use of Internet of Things applications in university education.

2.6 Adaptive learning environments

Farani and Fatani (2020) indicate that adaptive learning environments are primarily based on interaction between the learner and the electronic environment, where the learner works independently with computer programs to learn new concepts. Adaptive learning environments differ from traditional educational environments in that they adapt to the learner’s needs and learning style. Therefore, they independently discover the requirements of each learner and adapt appropriate content to him according to his abilities and level of achievement, which contributes to reducing cognitive burdens and works to increase the efficiency of the educational process.

2.7 Synthesis of previous studies

Previous research presents a mixed picture of AI adoption. For instance, Omari (2022) identified an average rate of the use of AI application among female teachers in Jordan, explaining that difficulties such as the need to monitor students and the necessity to train occurred. Positively, in contrast, high levels of use and high benefit were indicated in Yemeni universities and Jordanian private schools by Mutair (2022) and Hajjiah and Shaib (2020), respectively. Kina et al. (2021) highlighted the necessity of ethical frameworks and training of teachers. Subhi (2020) and Shen and Shen (2020) on the other hand reported low facial and use of AI among faculty and science education practitioners and identified workload and lack of training as barriers. These conflicting results support the situational specificity of AI integration and explain why the given study is focused on investigating the impact of individual variables on the use of AI by language teachers.

3 Research methodology and procedures

The descriptive approach was used due to its suitability for achieving the current research objectives and answering its questions. The current research community comprised all language teachers in the Education Directorate of the Qasaba Amman District. The sample size of 54 teachers of language was used, and they were chosen out of the schools that were ready to participate.

3.1 Primary research sample

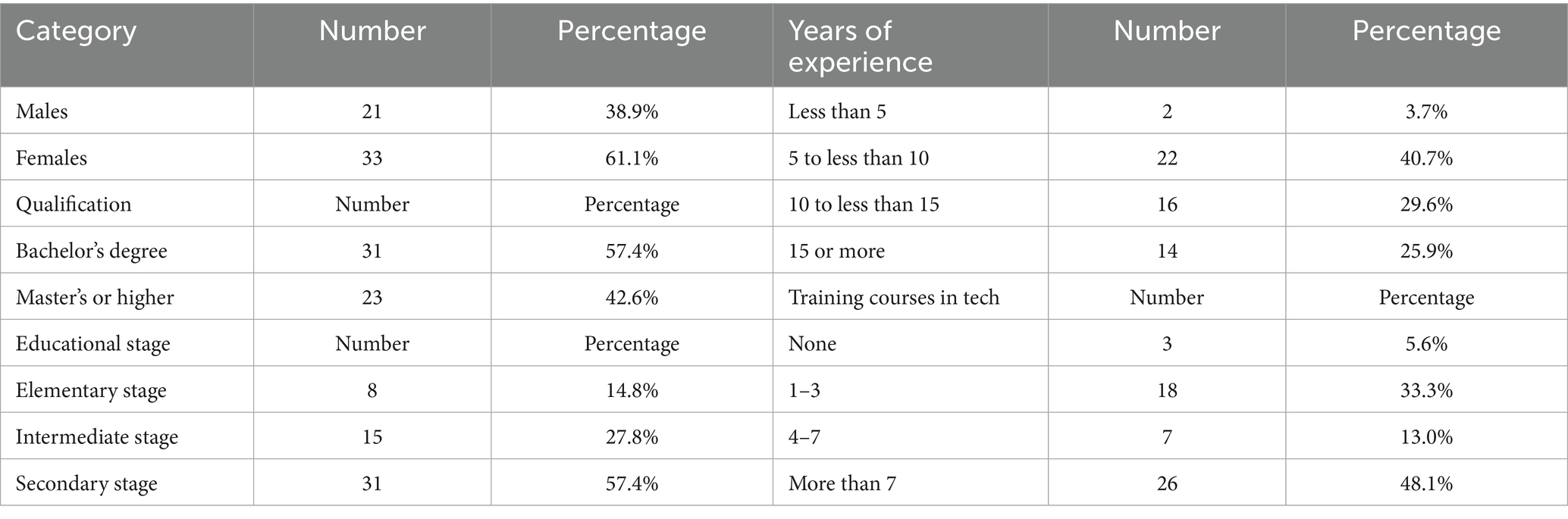

The final number of teachers in the current research sample was 54 language teachers, who were randomly selected from the population and administered the survey at the end of the second semester (2024–2025). Table 1 shows the distribution of the research sample according to the various variables:

The previous table shows that the largest percentage of the research sample members were females at 61.1%, while the percentage of males was 38.9%. The largest percentage of them had a bachelor’s degree at 57.4%, while the percentage of those with a master’s degree or higher was 42.6%. According to the educational level, the largest percentage was secondary school teachers at 57.4%, followed by intermediate schoolteachers at 27.8%, while the percentage of primary school teachers was 14.8%. According to the years of experience, the largest percentage was those with years of teaching experience “from 5 to less than 10 years” at 40.7%, followed by those with years of experience “from 10 to less than 15 years” at 29.6%, then those with years of experience “from 15 years or more” at 25.9%, then those with years of experience “less than 5 years” at 3.7%. It also shows that the largest percentage of the research sample members were those who 48.1% of respondents attended more than 7 technology training courses, followed by 33.3% who attended 1–3 courses, 13.0% who attended 4–7 training courses, and 5.6% who did not attend any training courses.

3.2 Research tool

The research tool was a questionnaire titled: Level of Use of Artificial Intelligence Applications in Education (prepared by the researcher). Several related studies were consulted to extract the questionnaire’s items, including (Subhi, 2020), (Hajjiah and Shaib, 2020), and (Omari, 2022). The questionnaire consisted of three parts. The first part collected the basic data, the second part listed the most important applications used by teachers, and included the following applications: (smart educational game applications, augmented reality applications supported by artificial intelligence, smart chatbots, virtual reality applications, smart assessment and testing applications, Internet of Things applications, adaptive learning environments, smartphone applications), and the third part measured the level of use. The questionnaire consisted of (47) items.

3.3 Psychometric validity of the questionnaire

The questionnaire was presented to several expert referees specializing in the field of educational technology. They were asked to study the questionnaire and express their opinions regarding its relevance to the dimension to which it pertains, the clarity of the phrases, the soundness of their linguistic formulation, and their suitability for achieving the objective for which they were designed. They were also asked to suggest ways to improve them by deleting, adding, or rephrasing. The referees provided valuable comments that informed the research, enhanced the questionnaire, and helped produce it in a good manner. The phrases that achieved agreement with more than 80% of the referees were retained, with all the amendments indicated.

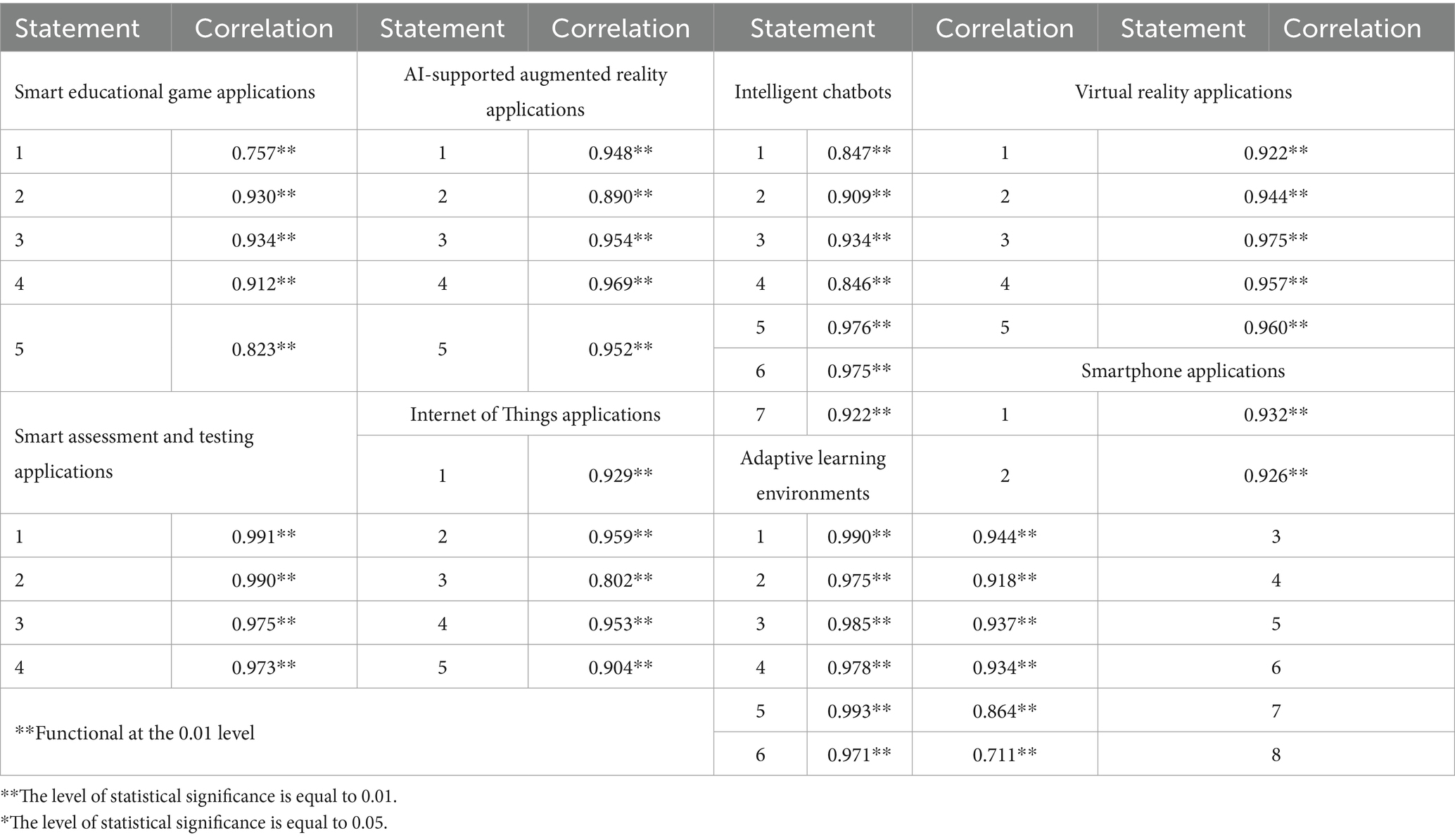

The questionnaire’s validity was also verified through internal consistency using Pearson’s correlation coefficient to calculate the correlation coefficients between the score of each questionnaire statement and the total score of the dimension to which the statement belongs. This was done to ensure the degree of coherence and consistency between the statements of each dimension. The correlation coefficients were as shown in the following table (Table 2):

Table 2. Correlation coefficients between the scores of the questionnaire statements and the total score of the dimension to which the statement belongs.

The previous table shows that the correlation coefficients between the questionnaire item scores and the total score of the dimension to which the item belongs are positive and statistically significant at the 0.01 level, confirming the consistency and homogeneity of the items in each dimension and their coherence with each other.

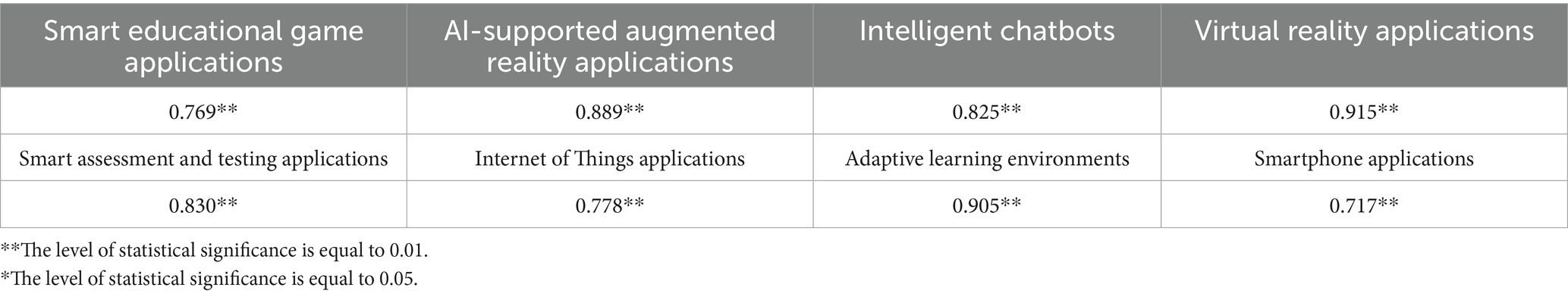

The homogeneity of the questionnaire’s sub-dimensions was also confirmed by calculating the correlation coefficients between the item scores and the total score. The correlation coefficients were as shown in the following table (Table 3).

Table 3. Correlation coefficients between the scores of the sub-dimensions of the questionnaire and the total score of the questionnaire.

It is clear from the previous table that the correlation coefficients between the dimension scores and the total score of the questionnaire are positive and statistically significant at the 0.01 level, which confirms the consistency and homogeneity of the questionnaire dimensions among themselves and their coherence with each other.

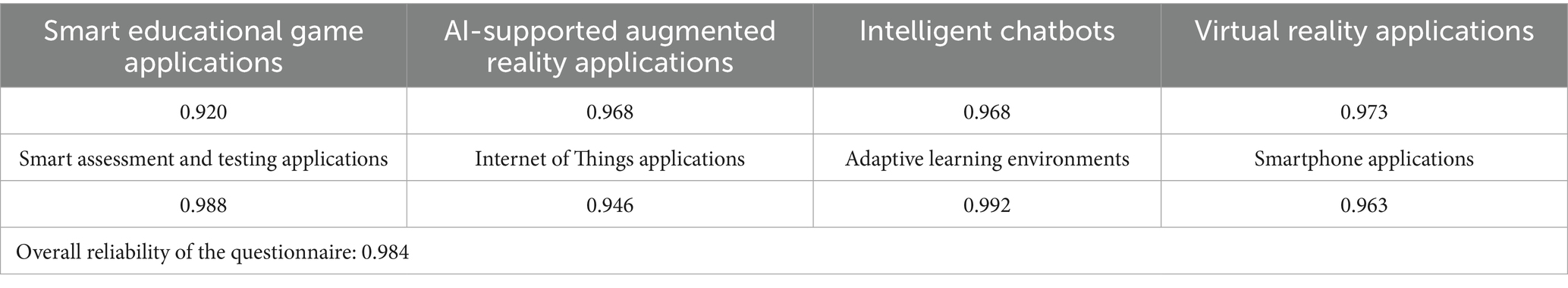

3.4 Reliability

The reliability of the questionnaire scores and its sub-dimensions was verified using Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient. The reliability coefficients were as shown in the following table (Table 4):

Table 4. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the questionnaire scores and its sub-dimensions.

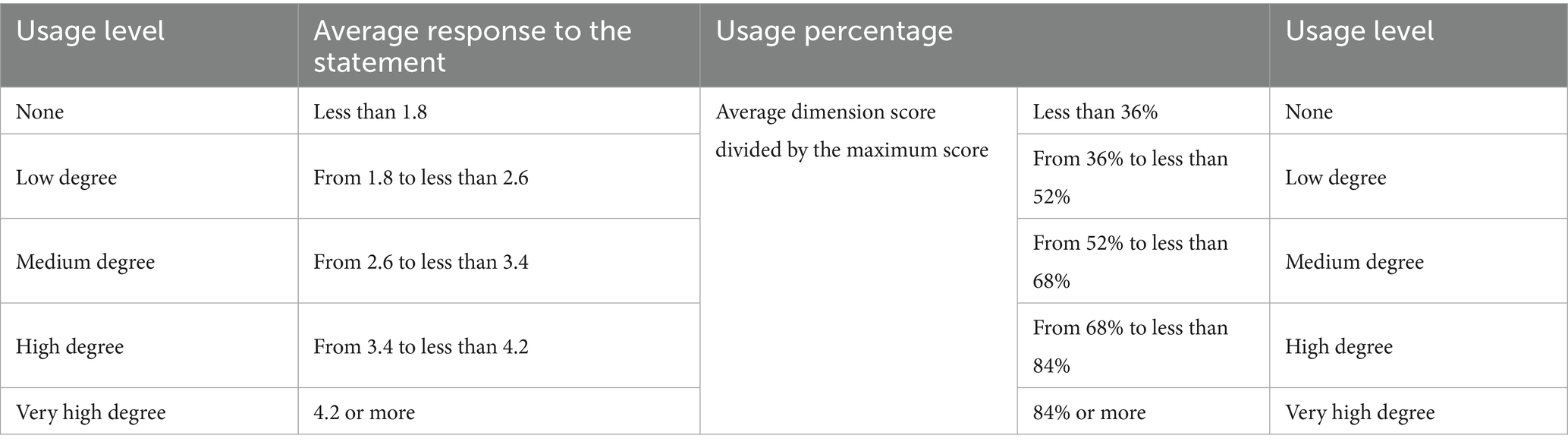

It is clear from the previous table that the questionnaire and its sub-dimensions have high and statistically acceptable reliability coefficients. From the above, the questionnaire has good statistical indicators (validity, reliability), which confirms its suitability for use in current research. It should also be noted that the questionnaire phrases used in the current research are responded to by choosing between five options that express the degree of use, which are (non-existent, weak, medium, large, very large), to correspond to the grades (1, 2, 3, 4, 5) respectively. The criteria shown in Table 5 were relied upon in judging the level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers:

Table 5. Criteria for judging the level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies by language teachers.

In the current study, several statistical methods were used using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) V. 22, as follows:

First, to ensure the validity and reliability of the tools used in the current research, the following were used

• Pearson Correlation Coefficient to ensure the internal consistency of the statements and dimensions of the questionnaire used in the current research.

• Cronbach’s Alpha Reliability Coefficient to ensure the reliability of the questionnaire scores and its sub-dimensions used in the current research.

Second, to answer the research questions, the following were used

• Means and standard deviations (Std.) to identify the level of use and importance of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers.

• Mann–Whitney U test to detect the significance of differences in the level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers according to (academic qualification and gender).

• Kruskal–Wallis H tested to detect the significance of differences in the level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers according to (study stage, years of experience, training courses).

4 Research results and interpretations

4.1 First: Results of the first question

The first question of the current research was “What is the level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers?” To answer this question, the means and standard deviations of the research sample’s responses to each questionnaire statement were calculated to reveal the level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers. The results were as shown below:

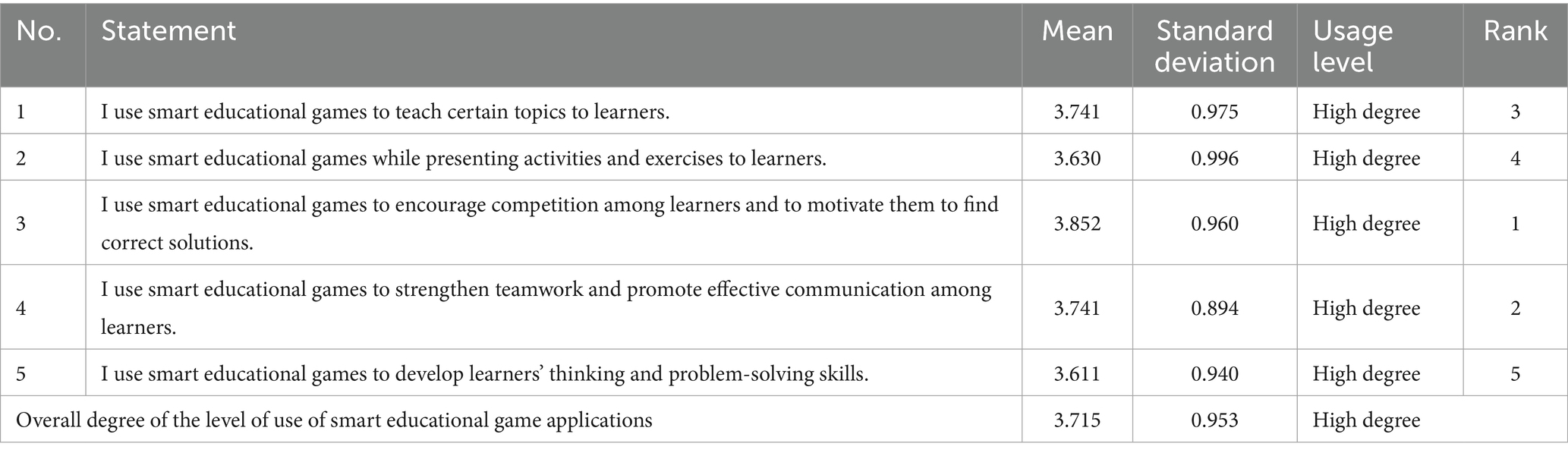

4.1.1 Smart educational game applications

Table 6 shows that language teachers largely use AI-based smart educational game applications, with an overall mean of 3.715 out of 5. All statements were rated largely achieved, with means ranging from 3.611 to 3.852. The highest-rated use was promoting competition to motivate learners toward correct solutions (M = 3.852), followed by fostering teamwork and effective communication (M = 3.741), using games to teach subjects (M = 3.741), incorporating games into activities and exercises (M = 3.630), and developing learners’ thinking and problem-solving skills (M = 3.611).

Table 6. Means and standard deviations of the research sample’s responses regarding the level of use of smart educational game applications.

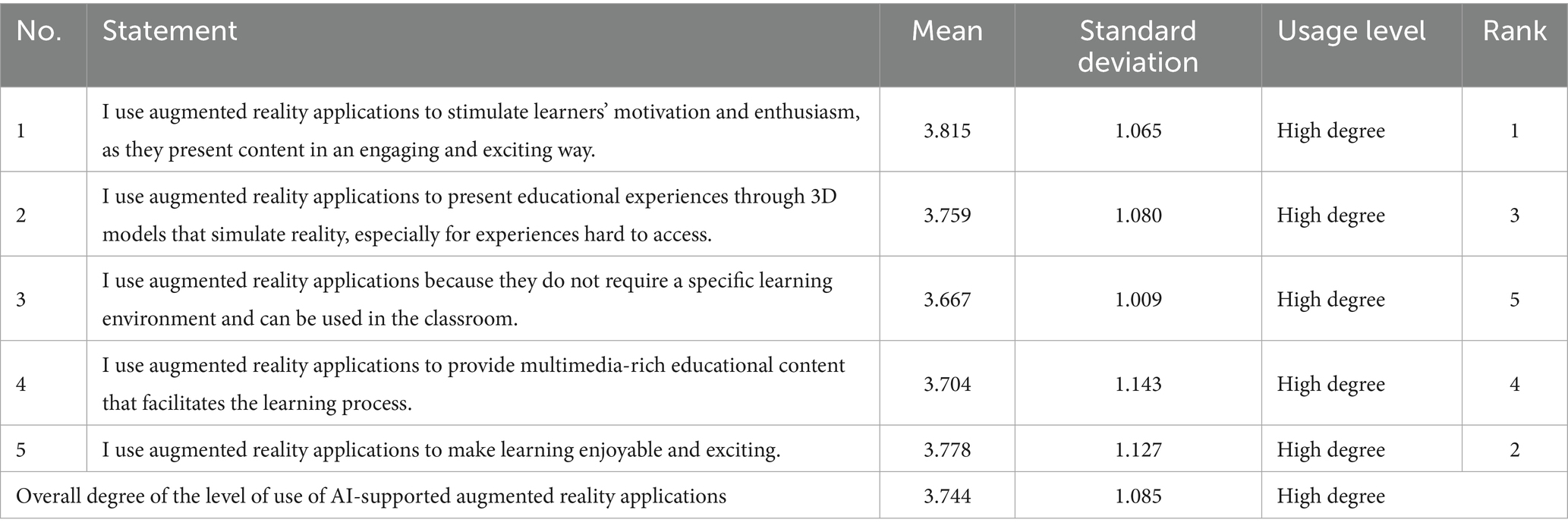

Artificial Intelligence-Powered Augmented Reality Applications.

Table 7 shows that language teachers largely use AI-supported augmented reality applications, with an average score of 3.744 out of 5. The highest-rated use was to motivate learners by presenting material attractively (M = 3.815), followed by making learning fun (M = 3.778), offering 3D educational experiences (M = 3.759), providing multimedia-rich content (M = 3.704), and the flexibility of use in any classroom environment (M = 3.667).

Table 7. Means and standard deviations of the research sample members’ responses regarding the level of use of artificial intelligence-powered augmented reality applications.

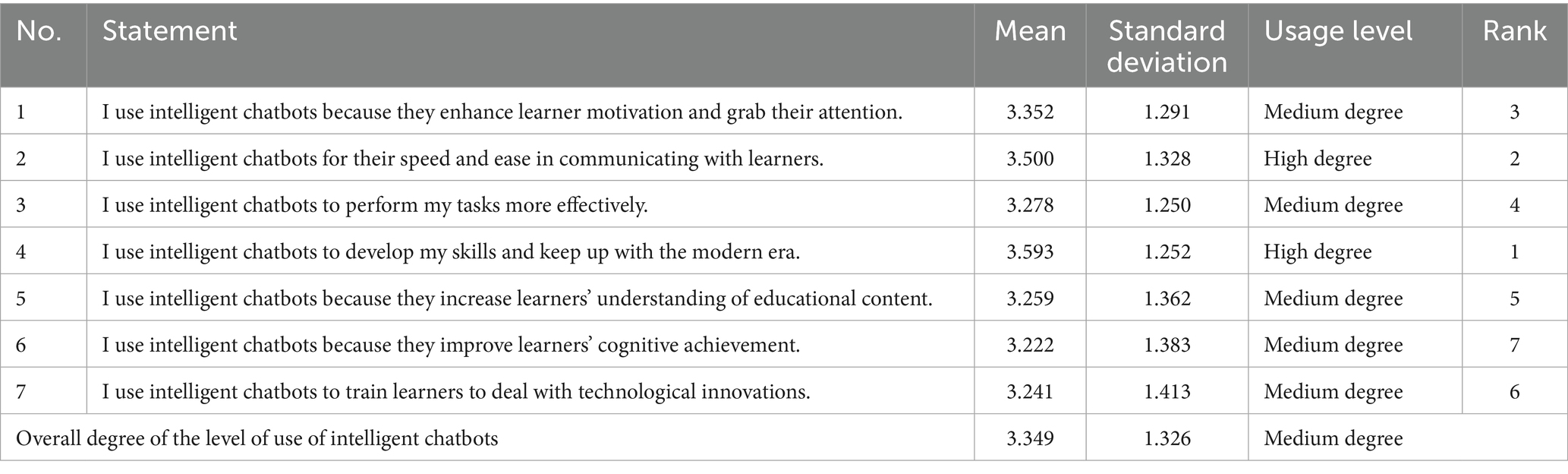

4.1.2 Smart Chatbots

Table 8 indicates that language teachers’ use of AI-based smart chatbots is moderate, with an overall mean of 3.349 out of 5. Two statements were rated highly, while five were rated moderately, with averages ranging from 3.222 to 3.593. The highest-rated use was developing teachers’ skills and keeping up with modern trends (M = 3.593), followed by facilitating quick communication with learners (M = 3.500), and enhancing learner motivation and attention (M = 3.352). Other uses included task efficiency, improving content understanding, training learners on technology, and improving cognitive achievement, with the lowest rating for cognitive achievement (M = 3.222).

Table 8. Means and standard deviations of the research sample members’ responses regarding the level of use of smart chatbots.

4.1.3 Virtual reality applications

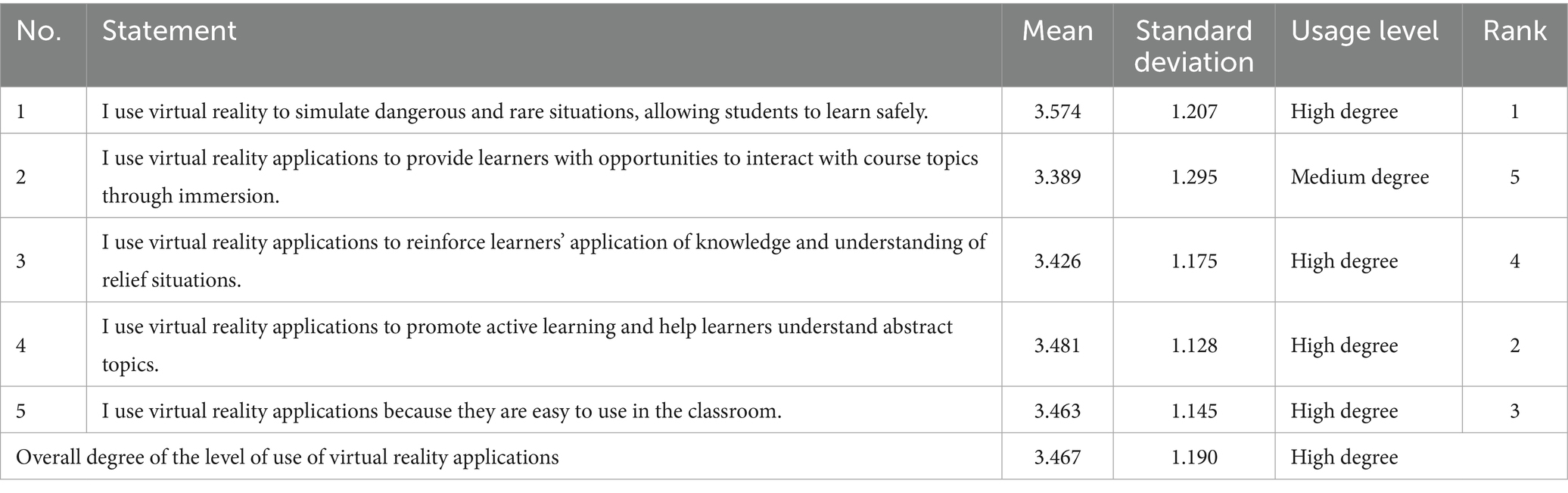

Table 9 shows that language teachers largely use AI-based virtual reality applications, with an average score of 3.467 out of 5. Most statements were largely achieved, including using VR to simulate safe learning of dangerous situations (M = 3.574) and enhancing active learning (M = 3.481). Other uses included ease of classroom use, applying knowledge to real life, and immersive interaction, with the last rated moderately (M = 3.389).

Table 9. Means and standard deviations of the research sample members’ responses regarding the level of use of virtual reality applications.

4.1.4 Smart assessment and testing applications

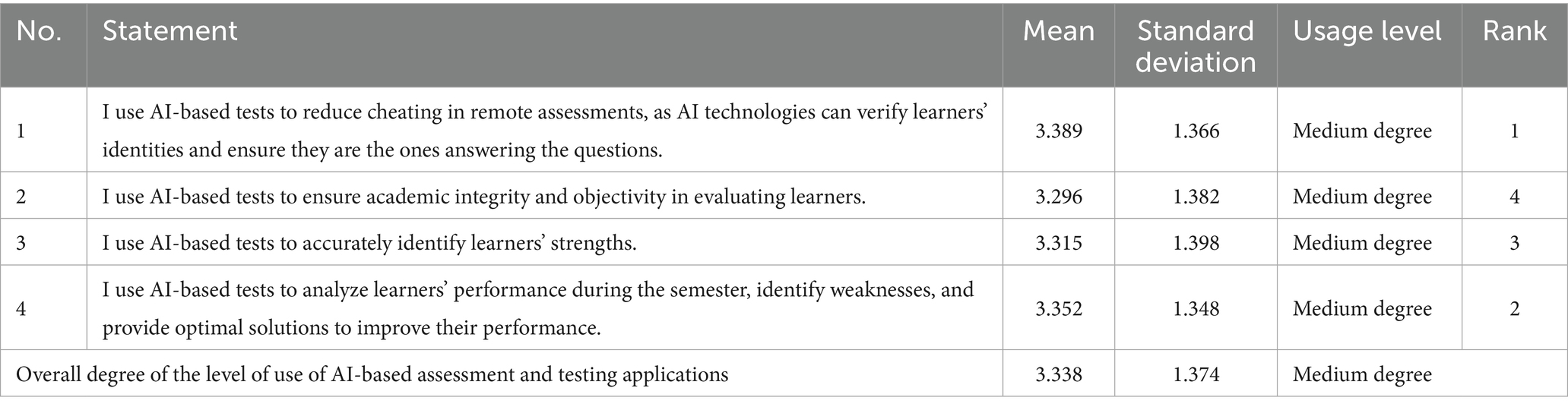

Table 10 shows that language teachers’ use of AI-based assessment and smart testing applications is moderate, with an average score of 3.338 out of 5. All statements were rated moderately, including using AI tests to reduce cheating (M = 3.389), analyze learner progress and weaknesses (M = 3.352), identify strengths (M = 3.315), and ensure integrity and objectivity in assessments (M = 3.296).

Table 10. Means and standard deviations of the research sample members’ responses regarding the level of use of smart assessment and testing applications.

4.1.5 Internet of Things applications

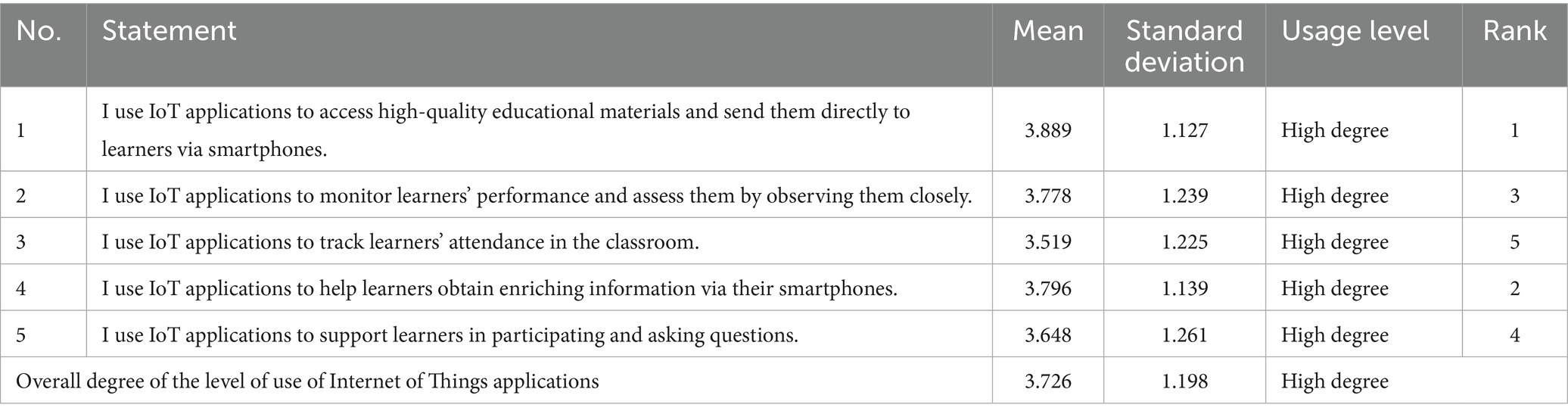

Table 11 shows that language teachers largely use AI-based Internet of Things (IoT) applications, with an average score of 3.726 out of 5. The highest-rated use was accessing and delivering high-quality educational materials via smartphones (M = 3.889), followed by helping learners obtain enriching information (M = 3.796), monitoring and evaluating learner performance (M = 3.778), encouraging learner participation and questions (M = 3.648), and tracking classroom attendance (M = 3.519).

Table 11. Means and standard deviations of the research sample’s responses regarding the level of use of Internet of Things applications.

4.1.6 Adaptive learning environments

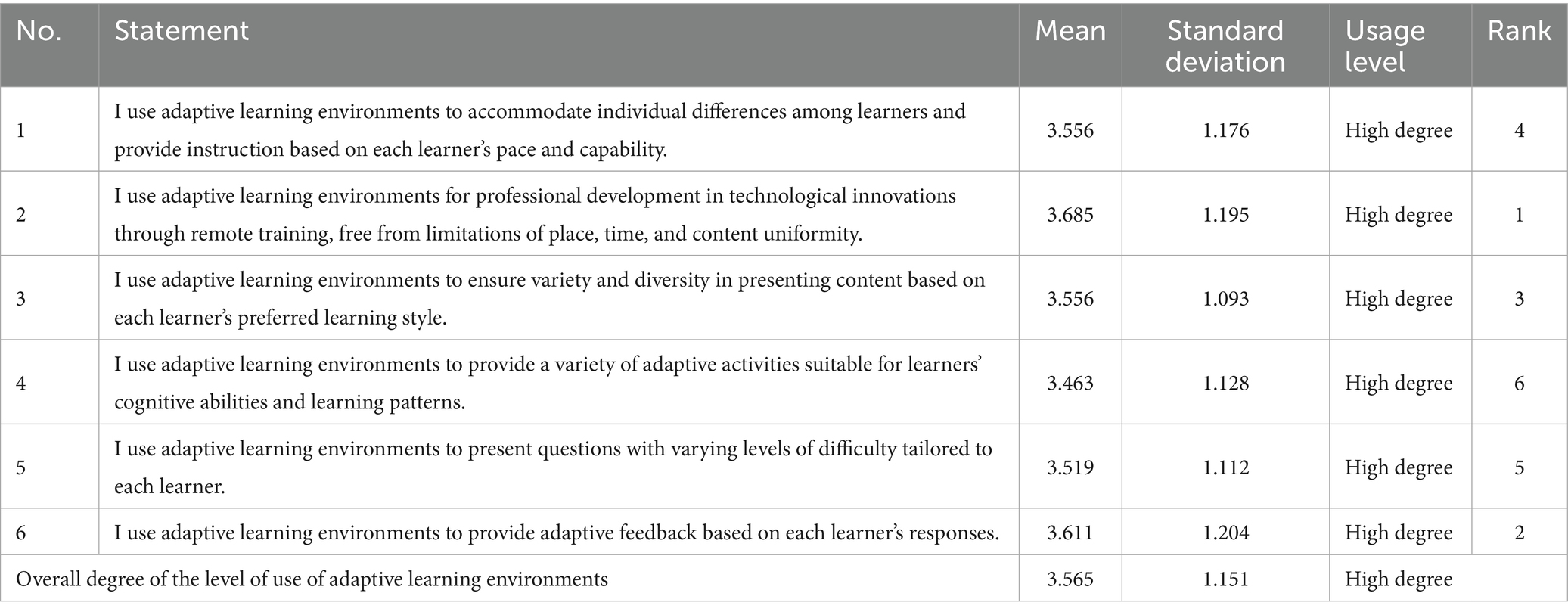

Table 12 shows that the use of adaptive learning environments—one of the AI-based educational applications—is largely achieved among language teachers, with a weighted mean of 3.565 out of 5 and a standard deviation of 1.151. All statements under this dimension were rated as largely achieved, with mean scores ranging from 3.463 to 3.685. The highest-rated statement was the use of adaptive learning environments for professional development through distance training, free from the constraints of time, place, and rigid content (M = 3.685). This was followed by providing adaptive feedback based on learners’ responses (M = 3.611), diversifying content presentation according to learning methods (M = 3.556), addressing individual differences and adapting to learners’ pace and abilities (M = 3.556), offering questions with varying difficulty levels (M = 3.519), and finally, providing a variety of adaptive activities suited to learners’ styles and mental abilities (M = 3.463). These results reflect a strong integration of adaptive learning environments in language instruction.

Table 12. Means and standard deviations of the responses of the research sample members regarding the level of use of adaptive learning environments.

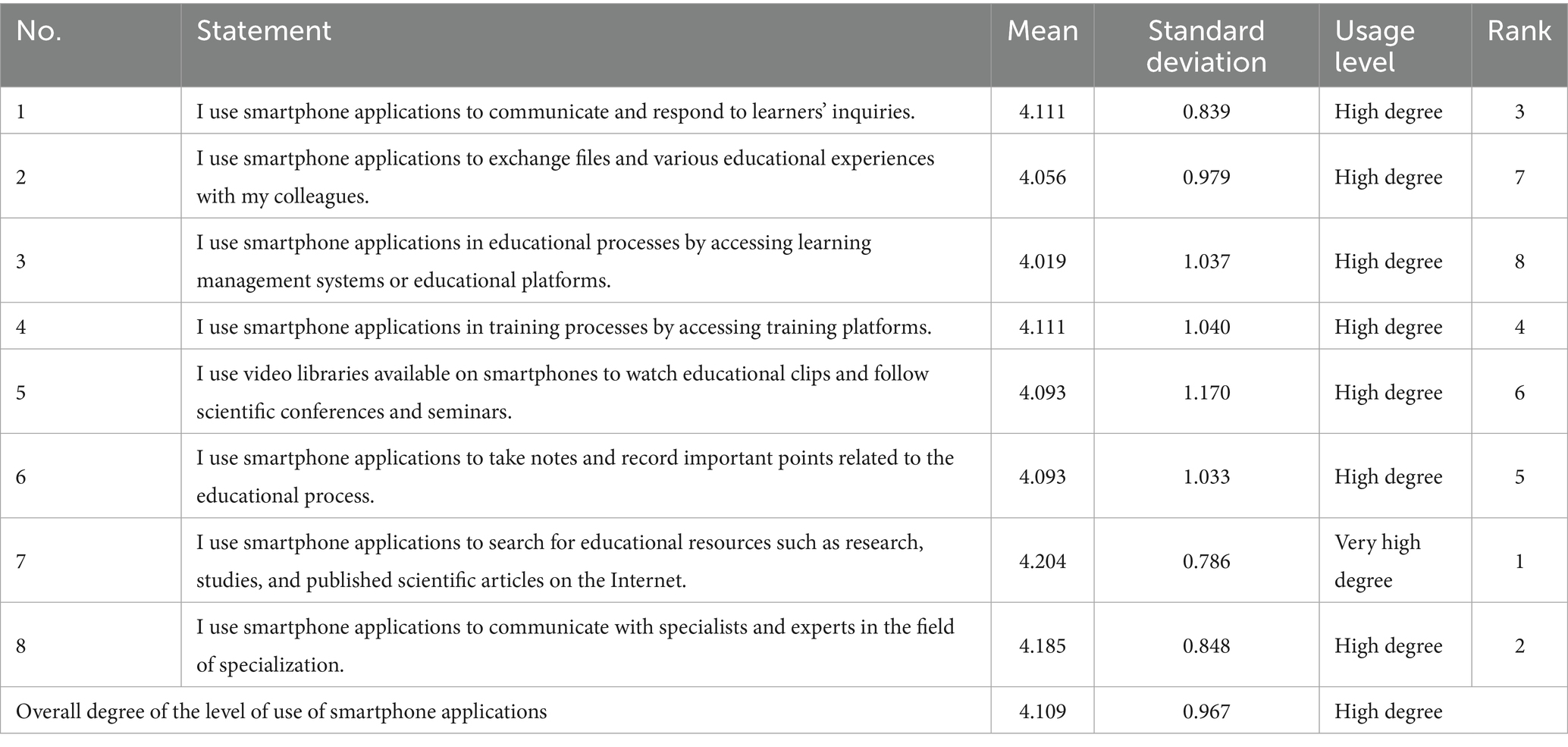

4.1.7 Smartphone applications

Table 13 shows that language teachers largely use AI-based smartphone applications, with an overall mean of 4.109 out of 5. The highest use was for searching educational resources (M = 4.204), followed by communicating with experts (M = 4.185) and answering learners’ inquiries (M = 4.111). Other common uses included notetaking, watching educational videos, sharing files, and accessing educational platforms, with the lowest use for learning management systems (M = 4.019). This indicates widespread adoption of smartphone apps in language teaching.

Table 13. Means and standard deviations of the research sample members’ responses regarding the level of smartphone application use.

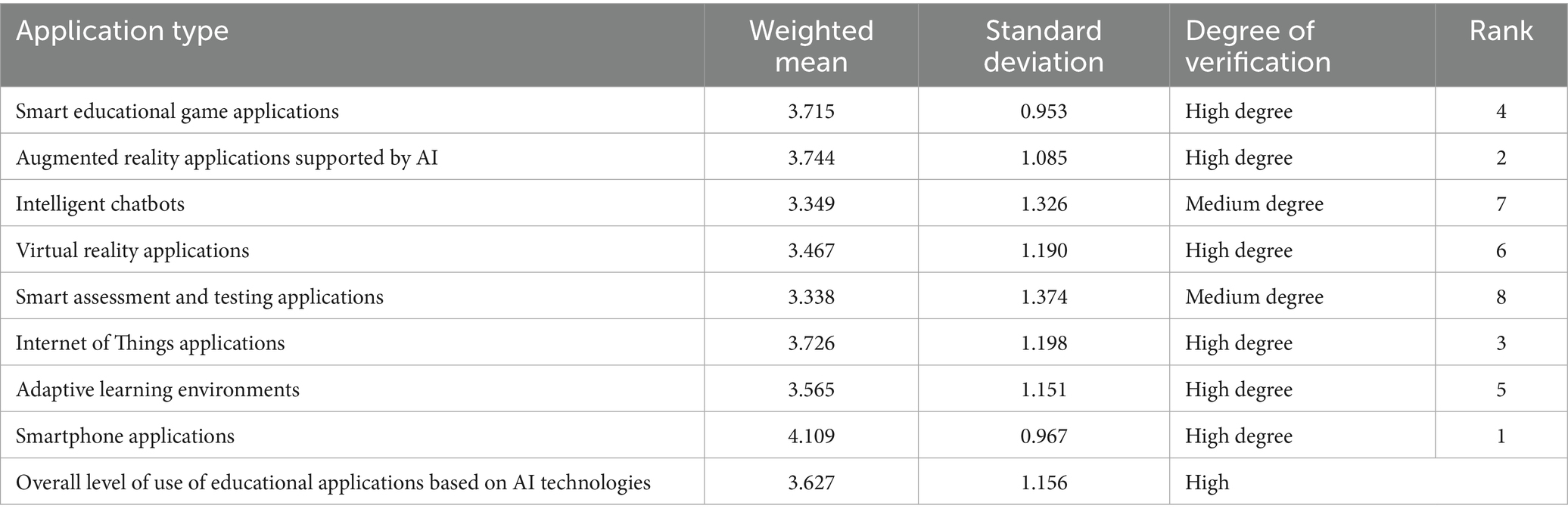

The results indicate that language teachers’ overall use of educational applications based on AI technologies is largely achieved, with an average score of 3.627 out of 5 and a standard deviation of 1.156. Smartphone applications ranked first in usage (M = 4.109), followed by AI-supported augmented reality (M = 3.744), Internet of Things (M = 3.726), and smart educational game applications (M = 3.715)—all rated as largely achieved. Adaptive learning environments (M = 3.565) also showed high usage, while virtual reality applications (M = 3.467) were slightly lower but still highly achieved. Smart chatbots (M = 3.349) and smart assessment and testing applications (M = 3.338) were rated as moderately achieved, ranking seventh and eighth, respectively.

The researcher attributes the high overall level of use of AI-based educational applications among language teachers to their strong awareness of the importance of these technologies in education. These applications create an engaging, interactive environment that encourages students’ participation and communication, allowing learners to interact freely without fear or embarrassment and receive responses anytime and anywhere. Additionally, AI applications support individualized learning by adapting to students’ different levels and needs. These findings align with previous studies, including those by Mutair (2022), Hajjiah and Shaib (2020), and Chen et al. (2020), which confirm that AI technologies enhance language instruction, improve teaching methods, and develop language skills.

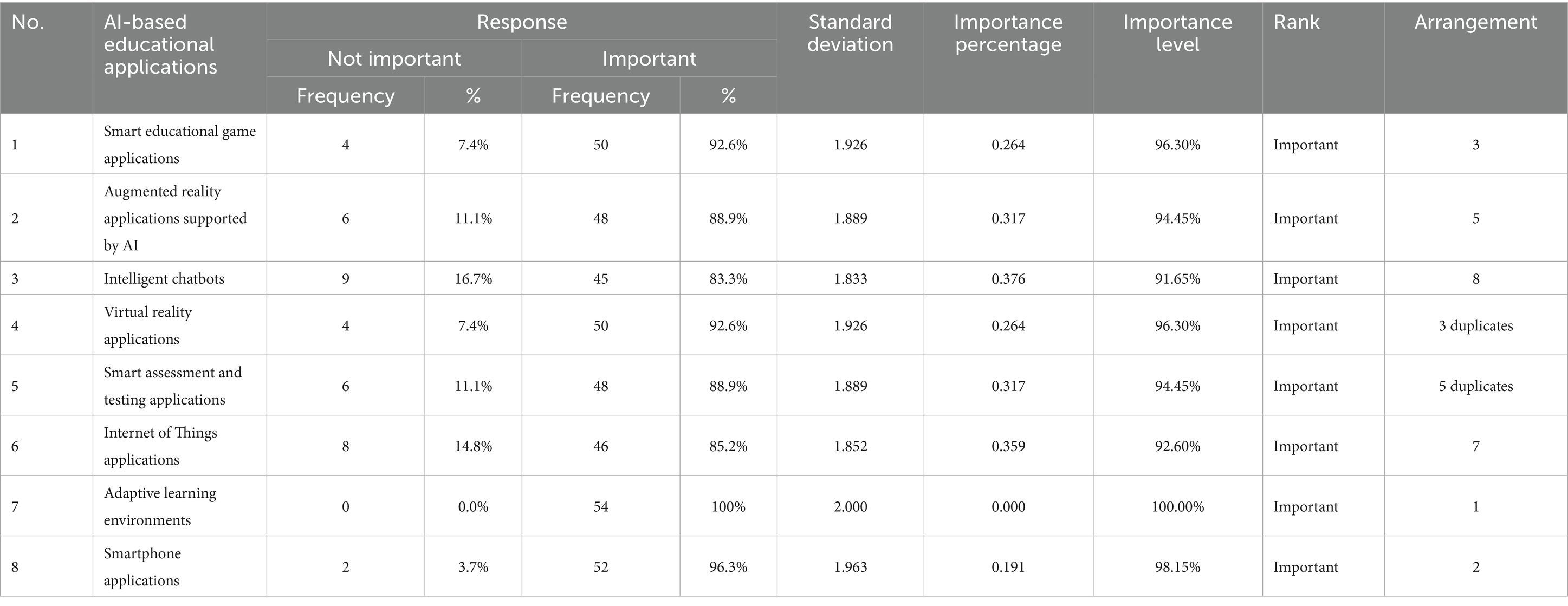

4.2 Second: Results of the second question

To assess language teachers’ perspectives on the importance of using AI-based educational applications, means and standard deviations were calculated. The results showed that all applications were considered important, with average scores above 1.5 and importance rates exceeding 91%. Adaptive learning environments ranked highest in importance, followed by smartphone applications, then smart educational game applications and virtual reality applications (tied), followed by AI-supported augmented reality and smart assessment/testing applications (also tied), then Internet of Things (IoT) applications. Smart chatbots ranked last in perceived importance.

The researcher attributes the findings of the second question regarding the importance of using educational applications based on AI technologies from the perspective of language teachers. This finding indicated that adaptive learning environments are the most important, from their perspective. This is due to the nature of the language courses, which require practicing the language in a safe environment that matches the level and needs of each student, considering their characteristics and previous experiences in the language. This environment allows students to interact with the language at any time. Furthermore, it increases learners’ motivation to learn the language due to the attractive and engaging multimedia it contains. These results are consistent with the results of the following studies (Naguib et al., 2020; Azmy et al., 2014).

4.3 Third: Results of the third question

The third question investigated the effect of selected variables on AI application use.

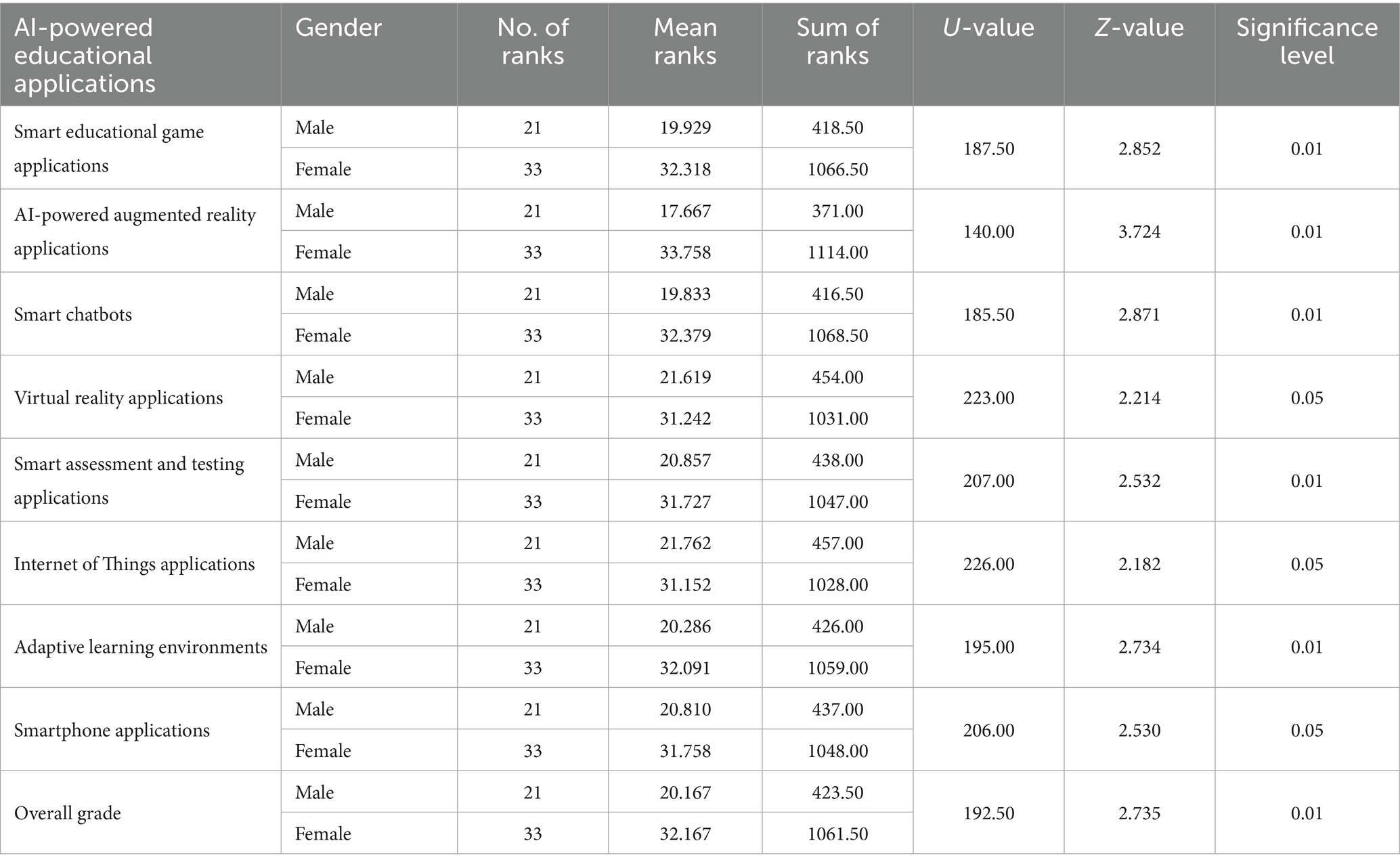

4.3.1 A-gender variable

The Mann–Whitney U test for independent groups was used in the case of a small number of groups to detect the significance of differences in the language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in gender. The results were as shown in the following table:

Table 14 shows that there are statistically significant differences at a significance level of 0.01 or 0.05 in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to gender differences, with the differences in all cases favoring females.

Table 14. Significance of differences in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in gender.

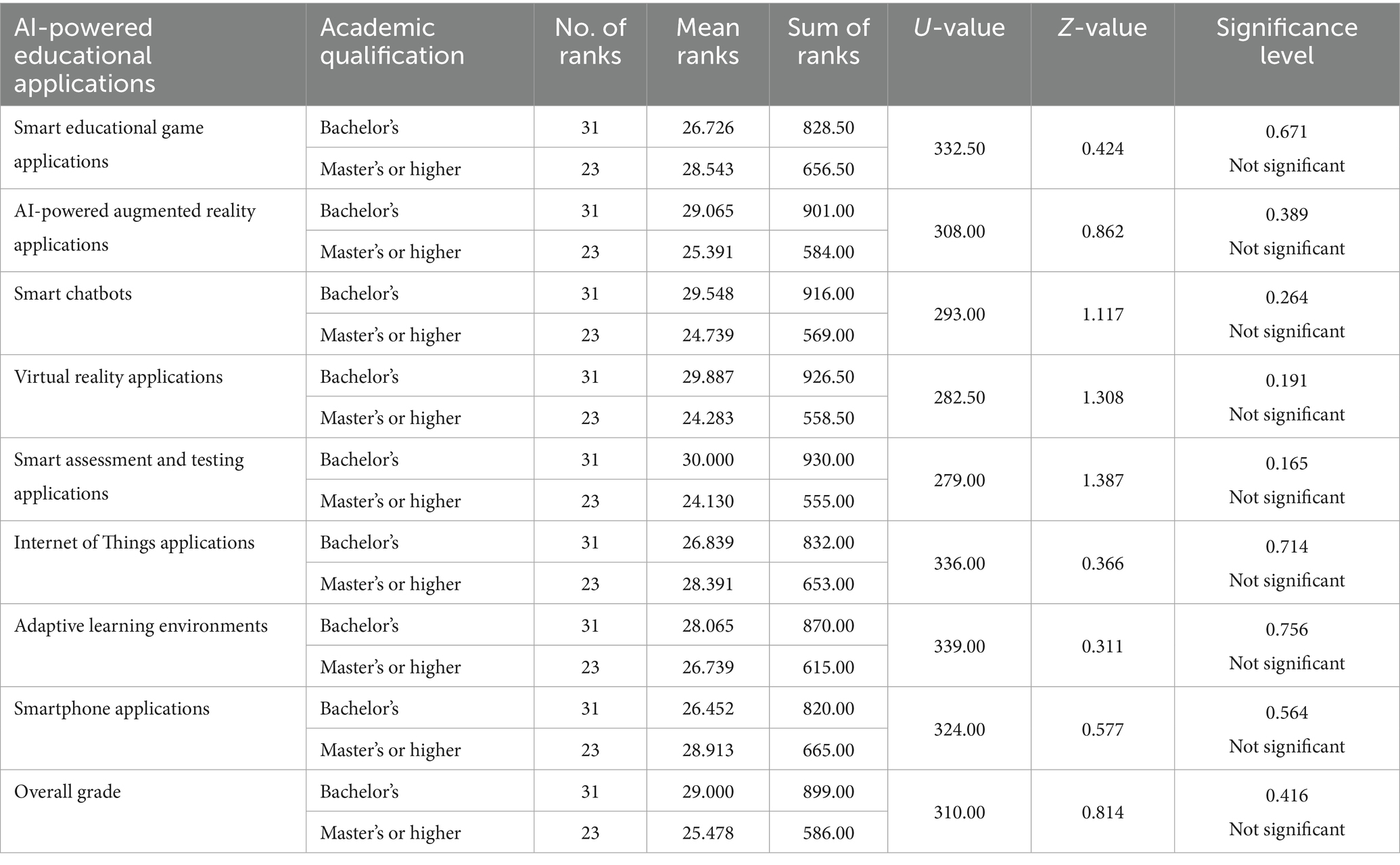

4.3.2 B-academic qualification variable

The Mann–Whitney U test for independent groups was used in the case of a small number of groups to detect the significance of differences in the language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in academic qualifications. The results were as shown in the following table:

Table 15 shows that there are no statistically significant differences in the language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in academic qualifications.

Table 15. Significance of differences in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in academic qualifications.

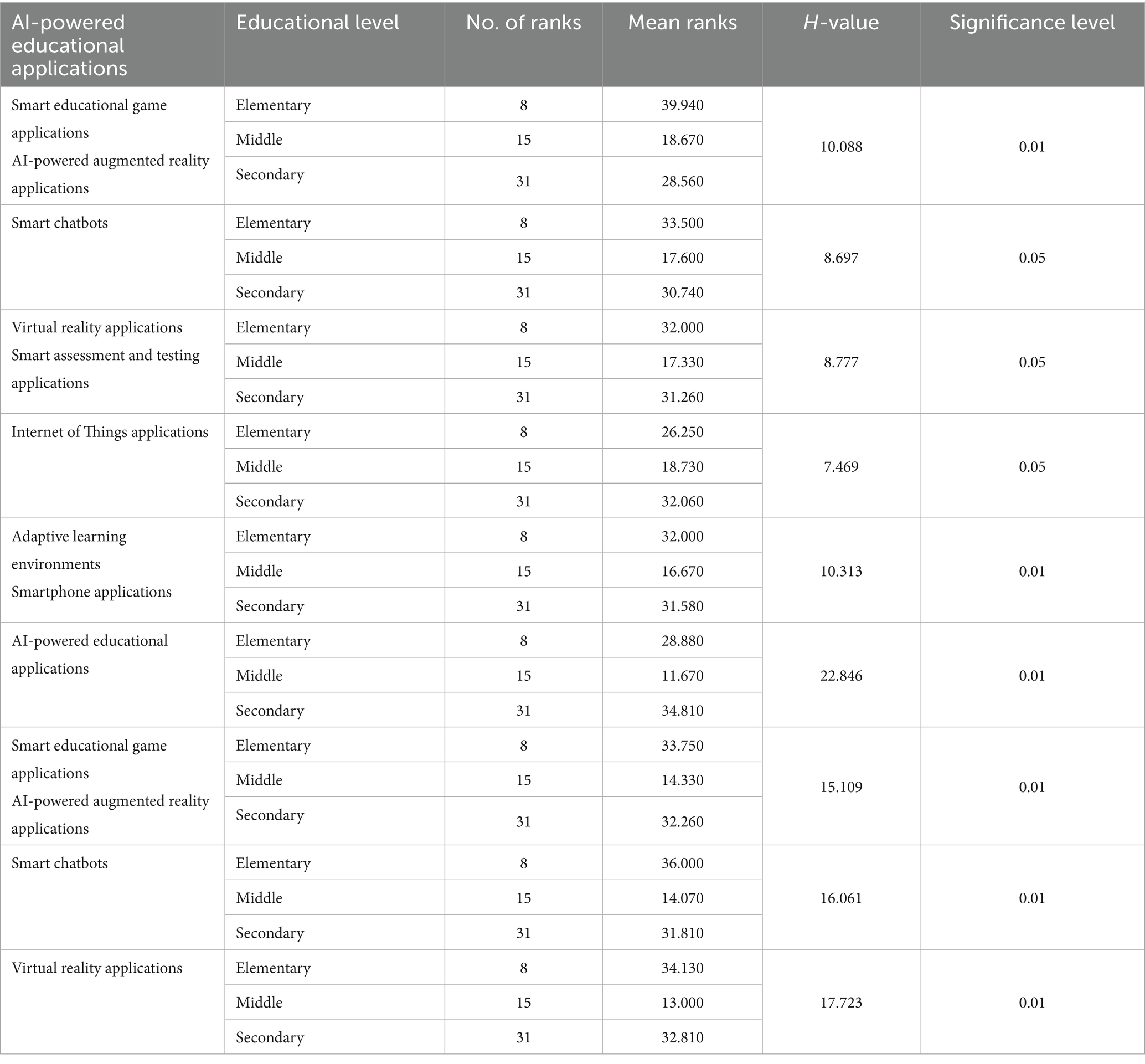

4.3.3 C-educational level variable

The Krusk–Wallis H test, used in the case of small groups, was used to detect the significance of differences in the language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in the educational level in which the teacher works. The results were as shown in the following table:

Table 16 shows that there are statistically significant differences at a significant level of 0.01 or 0.05 in the language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies, due to differences in educational level. By observing the average ranks, we note that the teachers who use educational AI technologies are the least of the teachers who use them, while the teachers who use them the most are primary and secondary school teachers.

Table 16. Significance of differences in the language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in the educational level.

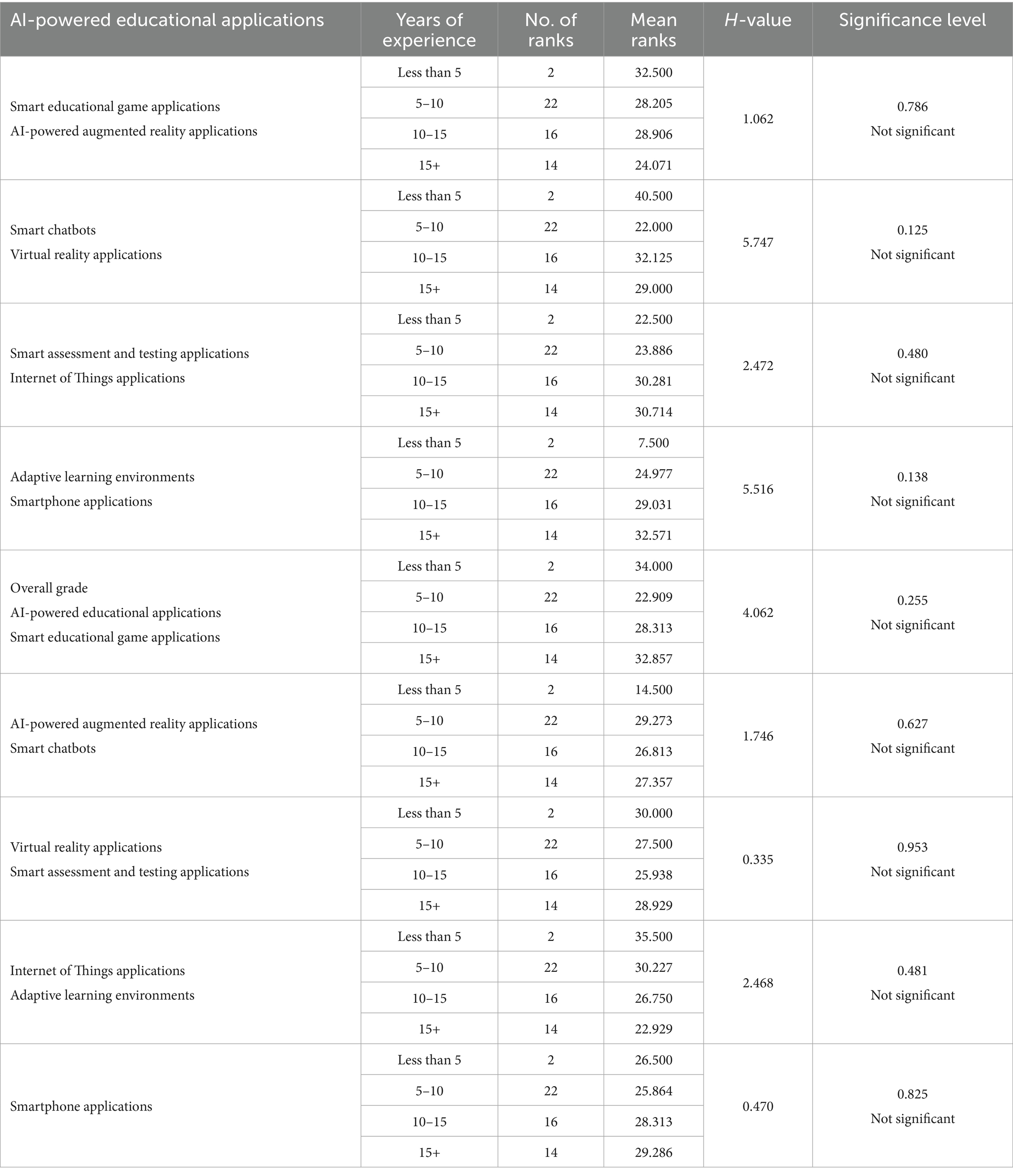

4.3.4 D-years of experience variable

The Krush–Wallis H test, used in small groups, was used to reveal the significance of differences in the language teachers’ use of educational AI technologies, due to differences in years of teaching experience. The results were as shown in the following table:

Table 17 shows that there are no statistically significant differences in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in years of experience.

Table 17. Significance of differences in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies, due to differences in years of teaching experience.

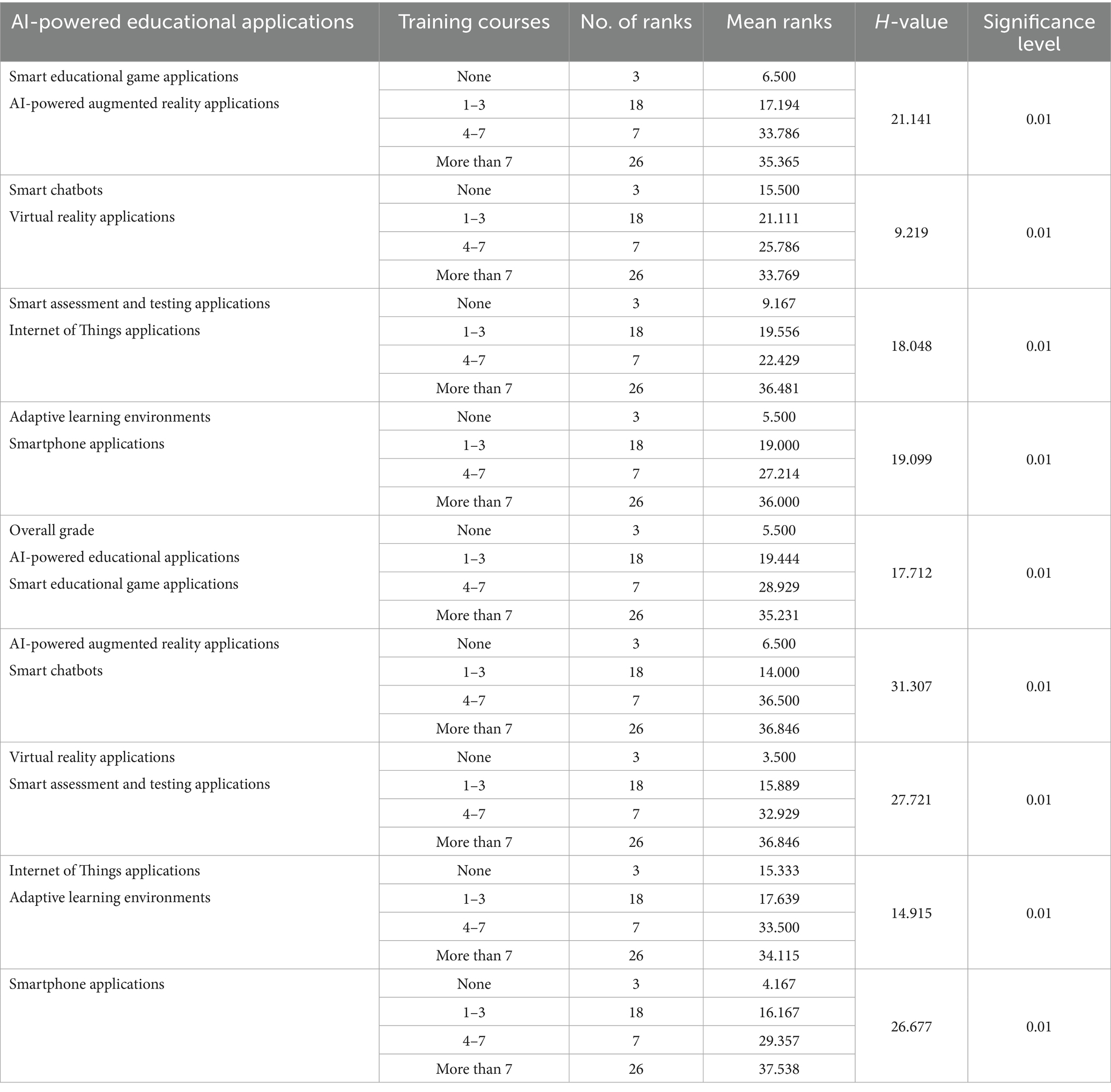

4.3.5 E-training course variable

The Krusk–Wallis H test was used, used in the case of small groups, to detect the significance of differences in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in training courses in the field of technology. The results were as shown in the following table:

Table 18 shows statistically significant differences (at the 0.01 level) in language teachers’ use of AI-based educational applications based on the number of training courses in technology, with usage increasing as training increases. The study found no significant differences related to academic qualifications or teaching experience, as AI tools are generally easy to use regardless of experience. However, female teachers were found to use AI tools more than males, possibly due to a stronger motivation to develop and showcase their skills. Additionally, primary and secondary school teachers used AI applications more than intermediate-level teachers, likely because younger students require more engaging environments and older students need language enhancement before university. Teachers who participated in multiple technology training sessions showed greater AI use, as such training builds confidence, practical skills, and familiarity with effective integration strategies.

Table 18. Significance of differences in language teachers’ use of educational applications based on AI technologies due to differences in training courses in the field of technology (degrees of freedom = 3).

5 Discussion

The current research explored how well language teachers utilize the artificial intelligence (AI)-based education apps, their vision of the relevance of the education apps, and how demographic and professional factors affect using the apps. The findings indicate that the adoption of AI tools is mostly large, with significant differences in their use based on the nature of applications and the traits of the teacher.

5.1 Application of AI-based educational applications

The results showed that the general usage of AI-based educational applications among language teachers was high, and the average was 3.627 (Table 19). Smartphone application (M = 4.08) was the most adopted, then augmented reality (M = 3.96), the Internet of Things (M = 3.92), and smart educational games (M = 3.91) (Table 13). These findings indicate that educators feel most at ease with those technologies which are either available or those that are easy to use and those that are already a part of their routine professional activities. The widespread popularity of smartphones, specifically, is in line with worldwide tendencies in mobile-assisted language learning, the mobile apps of which have become flexible, connected, and can give instant access to resources (Mutair, 2022; Chen et al., 2020). In contrast, the smartest chatbots (M = 2.72) and smart assessment/testing applications (M = 2.93) were the least used and were rated at a moderate level (Table 20). This finding might be explained by the fact that teachers are not well acquainted with these tools, fear that they are less reliable pedagogical tools, or the fact that they will require extra technical skills to make them effective. Past research has also shown that although chatbots have the potential to improve communication and deliver real-time feedback, educators are reluctant to use them because of a perceived lack of accuracy and authenticity (Hajjiah and Shaib, 2020). Similarly, AI based tests, which can be of good value in terms of objectivity and detection of academic dishonesty, might be opposed due to lack of trust and ethical concerns related to data usage (Azmy et al., 2014). A second tendency is the active use of adaptive learning environments (M = 3.91, Table 19), which demonstrates the awareness of teachers about the necessity to individualize teaching to fit the abilities of students with varying abilities. This observation reinforces the thesis that adaptable AI technologies can be especially useful in language instruction in which the conditions of the learner can differ significantly in terms of proficiency, learning approach, and speed (Naguib et al., 2020).

Table 19. Level of use of educational applications based on AI technologies among language teachers.

Table 20. Frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations of the responses of the research sample members regarding the importance of using educational applications based on AI technologies.

5.2 Perceived significance of AI uses

Although usage levels were different, all AI-based applications were rated by teachers as significant, and the percentage of importance was over 91% (Table 20). Adaptive learning environments had the highest ranking (100%), and then smartphone applications (98.15%). It means that educators give more importance to the tools that can assist in personal learning and increase access to resources. The high value of adaptive environments also indicates the pedagogic character of language teaching, which involves differentiated learning and safe and engaging language-learning spaces. These results are consistent with the existing studies which indicate that AI can promote motivation, autonomy and learner-centered teaching in language classes (Azmy et al., 2014; Naguib et al., 2020). Interestingly, chatbots, even though they were not widely adopted, were still perceived to be important (91.7%, Table 20), but they ranked last in importance perceptions. This implies that teachers have the potential and might not have the training, infrastructure, or confidence that they can integrate them together.

5.3 Teacher characteristics

The findings also indicated that there were considerable disparities in the adoption of AI depending on gender, level of education, and previous training, but not academic qualifications and years of teaching experience. The usage of all AI applications was reported to be significantly higher among female teachers (Table 14), which can be explained by the fact that they are more interested in interactive and communicative pedagogical approaches. This result confirms previous evidence that gender difference can affect the attitude toward technology adoption in education (Mutair, 2022). In the educational level, primary and secondary school teachers expressed more adoption of AI applications compared to middle school teachers (Table 16). This can be in accordance with curriculum demands or more institutional encouragement of innovation at the upper and lower ends of schooling. Training also played an important role, and the highest rates of use were reported by teachers who had taken over seven training courses related to technology (Table 18). This highlights the relevance of professional growth toward technological integration which is highly highlighted in the literature (Chen et al., 2020). Conversely, academic credentials (Table 15) or years of professional experience (Table 17) did not have a significant impact on the adoption of AI. This observation means that technological participation is less related to educational attainment or experience and more related to situational and incentive influences like training availability and organizational culture. Implications Altogether, the results highlight the increased adoption of AI technologies in language education, especially in the domain associated with accessibility, adaptability, and interactivity as its core elements. But they also point out that there are still unresolved gaps in the application of sophisticated AI tools like chatbots and evaluation tools. To combat these gaps, schools need to invest in specific professional growth, infrastructure and ethical frameworks that instill confidence in teachers on the use of such tools. In addition, the apparent differences based on gender and training factor indicate that there is a need to have equal access to training opportunities that will help teachers equally enjoy the gain of AI innovations.

6 Research limitation

The study focused on selected AI applications used by language teachers and examined how factors like gender, qualifications, teaching level, experience, and technology training affect their use. It was conducted with 54 teachers from public schools in Qasaba Amman, Jordan, during the second semester of the 2024–2025 academic year.

7 Recommendations

One way of improving the quality of education is to intensify training courses to make teachers develop the ability to use applications of artificial intelligence in education, particularly those who are middle school teachers. Also, of importance is guiding language teachers toward the use of smart educational game applications, AI-powered augmented and virtual reality applications, the Internet of Things, adaptive learning environments, and smartphone applications that are relevant and matching with curricula which, to a large extent, is capable of enhancing such teaching methods. Also, it is important to raise more awareness among male teachers in the language of using educational applications supported by artificial intelligence technologies to encourage innovativeness and effective implementation of AI in learning.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This research involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ammam Arab University (Approval No. 43698). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, as well as with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants' legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

KF: Writing – original draft, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. BY: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. HA: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. MA-K: Writing – review & editing, Validation. SA-F: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel-Barr, A., and Abdel-Hamid, M. (2020). A program based on interactive chatbots and Egyptian knowledge bank trips to develop some educational research skills and academic self-efficacy among graduate students at the college of education. J. College Educ. 31, 347–416.

Ardimansyah, M., and Widianto, M. (2021). Development of online learning media based on telegram chatbot (case studies: programming courses). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1987:012006. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1987/1/012001

Azmy, N., Ismail, A., and Mubarez, M. (2014). The effectiveness of an artificial intelligence-based e-learning environment for solving computer network problems for educational technology students. J. Educ. Technol. Stud. Res. 22, 235–279.

Chen, L., Chen, P., and Lin, Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence in education: a review. IEEE Access, 8, 75264–75278. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2988510

Dahshan, J. (2019). Employing the internet of things in education: justifications, areas, and challenges. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 2, 49–92. doi: 10.29009/ijres.2.3.1

Faqih, N. (2023). Developing literacy and critical thinking with AI: What students say. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on Islamic Education (AICIED), Vol. 1 (pp. 16). Institut Studi Islam Muhammadiyah Pacitan. Available online at: https://prosiding.iainponorogo.ac.id/index.php/aicied

Farani, L., and Fatani, H. (2020). Integrating artificial intelligence applications in intermediate schools: from adaptation to accreditation. Compr. Multi-Knowl. Electron. J. Publ. Sci. Educ. Res. 21, 1–38. doi: 10.55606/icesst.v1i2.491

Fitria, T. (2021). The use of technology based on artificial intelligence in English teaching and learning. J. Engl. Lang. Teach. For. Lang. Context 6, 52–68.

Ghoneim, N., and Elghotmy, H. (2021). Using an artificial intelligence-based program to enhance primary stage pupils’ EFL listening skills. Sohag J. Educ. 83, 1–324. doi: 10.21608/edusohag.2021.140694

Hajili, S., and Farani, L. (2022). Artificial intelligence in education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Arab J. Spec. Educ. 11, 71–84. doi: 10.59400/fes.v2i3.1379

Hajjiah, A., and Shaib, (2020). The degree of use of artificial intelligence applications and its relationship to competitive advantage in private schools in the capital Amman. (unpublished master’s thesis). Mafraq: Al al-Bayt University.

Huang, W., Hew, K. F., and Fryer, L. K. (2022). Chatbots for language learning—are they useful? A systematic review of chatbot-supported language learning. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 38, 237–257. doi: 10.1111/jcal.12610

Huwaiti, H., and Bani Ahmad, F. (2022). The degree of acceptance of faculty members in Jordanian universities to the use of artificial intelligence applications considering the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). (unpublished master’s thesis). Amman: Middle East University.

Kina, Y., Propova, V., Goroka, S., and Vysotskaya, S. (2021). Digital technologies and artificial intelligence technologies in education. Eur. J. Contemp. Educ. 10, 285–296. doi: 10.13187/ejced.2021.2.285

Kol, S., Schcolnik, M., and Spector-Cohen, E. (2018). Google translate in academic writing courses? EuroCALL Rev. 26, 50–58. doi: 10.4995/eurocall.2018.10140

Lampropoulos, G. (2023). “Augmented reality and artificial intelligence in education: toward immersive intelligent tutoring systems” in Augmented reality and artificial intelligence: the fusion of advanced technologies, vol. 2 (Berlin: Springer Nature), 137–146. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-27166-3_8

Morten, G. (2018). The role of artificial intelligence in social media big data analytics for disaster management. In 5th international conference on information and communication technologies for disaster management (ICT-DM).

Muqatil, L., and Hosni, H. (2021). Artificial intelligence and its educational applications to develop the educational process. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 10, 109–127. doi: 10.12691/wjssh-10-1-2

Mutair, A. (2022). The role of artificial intelligence in developing the educational process in Arabic language departments at Yemeni universities. Isbah J. Yemen 7, 114–129. doi: 10.58223/al-wazan.v3i1.345

Naguib, W., Abdullah, M., Omar, A., and Mahmoud, G. (2020). An adaptive learning environment for developing English language listening skills and learnability among secondary school students. J. Qual. Educ. Res. 60, 157–177.

Nakrin, S., and Rayer Van, D. (2020). Trustworthy artificial intelligence in education: opportunities and challenges (S. Nakrin and D. Rayer Van, Trans.). King Abdul-Aziz and his companions foundation for giftedness and creativity. Paris: OECD Education.

Omari, Z. (2022). The extent of using artificial intelligence applications in Namas learning schools from the teachers' perspective. J. College Educ. 86, 66–98.

Rashed, S. (2022). Designing interactive chat-based educational activities in the family education course and measuring their impact on academic achievement among second-year secondary school students in Taif. J. Curricula Teach. Methods 1, 63–84. doi: 10.26389/AJSRP.N100322

Salem, D., and Abu Jadayel, M. (2023). The effectiveness of using artificial intelligence technologies by the National Cybersecurity Authority in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as a future direction: a prospective study. J. Arab Res. Fields Spec. Educ. 30, 138–239.

Shahata, N. (2022). Employing artificial intelligence applications in the educational process. Sci. J. Egyptian Soc. Educ. Comput. 10, 205–214.

Shen, S., and Shen, H. (2020). A study on the application of artificial intelligence in elementary science education. J. Korean Element. Sci. Educ. 39, 117–132.

Subhi, S. (2020). The reality of Najran University faculty members' use of artificial intelligence applications in education. J. College Educ. Educ. Sci. 44, 319–368. doi: 10.21608/JFEES.2020.147725

Yajzi, F. (2019). Using artificial intelligence applications to support university education in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Arab Stud. Educ. Psychol. 113, 257–282.

Younis, M. (2022). Faculty members' attitudes towards the use of internet of things applications in university education: an analytical study considering the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). J. Fac. Educ. Educ. Sci. 46, 15–94.

Keywords: artificial intelligence applications, functional teaching applications, language teachers (English and Arabic language), language teaching, L1/L2 (first and second language)

Citation: Fayyoumi KAR, Yassin B, Almarashdi H, Al-Khawaldeh M and Al-Fayyoumi SK (2025) The extent to which language teachers use linguistic artificial intelligence applications: an analysis based on selected variables. Front. Educ. 10:1683845. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1683845

Edited by:

Mustafa Erol, Yıldız Technical University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Nadya Afdholy, Airlangga University, IndonesiaSibel Kahraman-Ozkurt, Pamukkale University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Fayyoumi, Yassin, Almarashdi, Al-Khawaldeh and Al-Fayyoumi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Baderaddin Yassin, YmFkZXIueWFzc2luQHl1LmVkdS5qbw==

†ORCID: Khalil Abdel Rahman Fayyoumi, orcid.org/0000-0003-1803-2070

Baderaddin Yassin, orcid.org/0009-0001-9753-5612

Somayyah Khalil Al-Fayyoumi, orcid.org/0009-0001-9753-5612

Khalil Abdel Rahman Fayyoumi1†

Khalil Abdel Rahman Fayyoumi1† Baderaddin Yassin

Baderaddin Yassin