- School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow, Dumfries, United Kingdom

From the outset of my doctoral enquiry, a persistent reflexive question has guided my scholarly trajectory: how might educators authentically engage with contexts shaped by intersectional marginalisation—the overlapping and compounding forms of exclusion structured across ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, age, and health status? This enquiry unfolds through two interrelated domains. First, in my role as a facilitator of qualitative methodology workshops within UK higher education (HE), I have observed discomfort among students when introduced to decolonial perspectives. This resistance often arises not merely from individual reluctance but from deeply entrenched epistemic hierarchies rooted in neoliberal, individualistic, and rationalist ideologies that shape the hidden curriculum. Second, as a critical feminist researcher, I have engaged with the ethical and methodological complexities of working with marginalised participants—specifically, female Black South African women confronting gendered health inequities. These experiences underscore the need to bridge epistemic and affective divides between privileged and marginalised groups in educational settings. This study argues that embedding radical empathy within pedagogical praxis and deliberately integrating intersectional positionalities into curriculum design are vital for cultivating transformative, justice-oriented educational environment. Radical empathy, understood as a sustained ethical–political engagement rather than sentimentality, enables classrooms to function as dialogic and emancipatory spaces where silenced voices are recognised and epistemic comfort is challenged. By reconceptualising classrooms as laboratories of empathy, equity, and democratic renewal, educators can resist market-driven and positivist imperatives, promote critical reflexivity, and cultivate the relational capacities necessary for inclusive, plural, and socially just societies. Although grounded in the UK HE context, the proposed model of pedagogy embedded in radical empathy holds global applicability, offering transferable insights for reimagining education as an emancipatory practice in increasingly divided and commodified academic landscapes.

Introduction

From the outset of my doctoral enquiry, a persistent reflexive question has guided my scholarly trajectory exploring how educators can authentically engage with contentious contexts shaped by intersectional marginalisation across diverse axes, including ethnicity, class, gender, sexuality, and health conditions. This question has unfolded through sustained critical reflexivity across two distinct yet interconnected domains. First, my pedagogical practice as a facilitator of qualitative methodology workshops, particularly oriented towards decolonial approaches informed by Smith (2021), for undergraduate honours students majoring in social and political sciences in UK higher education (HE). Second, an ongoing interrogation of my own differentiated positionalities, as a female, cisgender, highly educated East Asian raised in a middle-class household, juxtaposed with those of my research participants—female, cisgender, less formally educated, Black South Africans raised in low-income households.

In teaching qualitative methods, discomfort has been repeatedly observed among both UK and UK-based international students when introduced to Smith’s (2021) decolonial perspectives. In line with Smith’s ideas, this resistance, or passive engagement, can be interpreted as symptomatic of knowledge-power dynamics: the dominance of Western modernist epistemologies and the historical marginalisation or erasure of other voices. This highlights the need for students’ critical engagement with entrenched epistemic structures that unconsciously or tacitly privilege positivist, essentialist, and reductive viewpoints (Hesse-Biber, 2017).

Recent studies, however, reveal more complex configurations of intersectional marginalisation among UK students (Prior et al., 2024; Martinussen and Lahiri-Roy, 2025). These studies suggest imaginaries that extend beyond decolonial frames alone, aligning with Ali’s (2022) call to move pedagogical efforts on “decolonial” topics beyond racial classification. Educators must therefore address intersectionality not only as identity labels but also as multi-layered dynamics. For example, students from mixed or counter-stereotypical social backgrounds, such as poorer white gay men or affluent Asian and Black elite women, demonstrate the limits of treating Crenshaw’s (1989) foundational insights as exhaustive. This is because experiences of marginalisation and capacities for empathy are unevenly distributed and context-dependent. Receptiveness to decolonial approaches is thus not a given and must be cultivated by educators who invite students to engage with the assemblages of others’ identities and lived realities. Otherwise, identity hierarchies and epistemic power reproduce classroom evaluations as matters of individual success or failure rather than structurally mediated outcomes.

Furthermore, my position as a tutor-researcher is central—not peripheral—to this praxis. Intersecting dimensions of biography (nationality, ethnicity, language, socioeconomic background, educational attainment, sexual orientation, and health status) shape how I interpret classroom tensions, engage students, and read participants’ narratives. Crucially, developing analytical competence requires imaginaries beyond academic comfort zones, given my own training within Westernised institutions and modernist epistemic that privilege binary gender constructs, positivist assessment regimes, and neoliberal logic of individual accountability. Without sustained critical engagement, the classroom risks becoming a relay of modernist/colonial domination, where students are socialised to defend inherited epistemic hierarchies rather than recognise and respond to lived realities of others.

To address these challenges, the study proposes advancing critical feminist methodologies within HE contexts. These approaches can cultivate reflexive scrutiny of the structural conditions of knowledge production and centre marginalised voices, echoing critiques of symbolic liberalism (Harding, 1991; Lather, 2007). They reject putative neutrality and thin objectivity, as well as a merely identity-indexed liberalism, and instead foreground reflexivity of relationality, embodiment, and affective accountability. As Noddings (1984, pp. 5–6) reminded us, ‘The ethical self is, for me, a self-in-relation. It is a self that responds, that feels responsibility, and that assumes an ethical burden because it lives in relation to others’.

Building on Noddings’s position, radical empathy can be embedded as a pedagogical strategy for contentious classrooms. Radical empathy, as articulated by Givens (2021), is a more deliberate and sustained engagement than conventional empathy, which is typically fleeting and spontaneous. Radical empathy urges educators and students to proactively engage with different positionalities and roleplays to interrogate one’s complicity in structures of privilege and oppression. This stance aligns with Sellars and Imig’s (2021) emphasis on an instructor’s practice. In critical reflexive work, radical empathy can help reduce defensiveness among students who feel implicated in critiques of Western epistemologies, validate the marginalised lived experience of students, and convert discomfort into opportunities for deeper relational and critical engagement.

Ultimately, when classrooms forgo this reparative function and fail to practise radical empathy, they default to structural conformity with neoliberal, commercialised demands (Serra Undurraga, 2025), thereby entrenching zones of non-empathy that mask intersectional complexity. In contrast, approached as miniature public spheres and laboratories, classrooms can sustain an ethically balanced politicality, which is rigorous enough to contest inequity and capacious enough to sustain care, cultivating the intellectual and affective capacities required not only to diagnose systemic injustice but also to re-imagine and remake the social demands that sustain it.

Power-driven legitimacies in higher education

Aligning with strands of critical pedagogy, pedagogical frameworks in UK higher education (HE) and teacher training are often critiqued for being embedded within entrenched power dynamics. These power dynamics include neoliberal, market-driven ideologies (Serra Undurraga, 2025), a rationalist discourse that privileges reason as the central marker of legitimate knowledge (Smith, 2021), essentialist assumptions about knowledge and identity (Şahin, 2018), and heteronormative content that marginalises non-normative sexualities, including LGBTQI+ identities (Shlasko, 2005; Stonewall, 2018). Consequently, a sense of belonging is imperative to all students’ mental health and engagement in education environments, while institutional silence on marginalised matters can exacerbate isolation and invisibility (Quinlivan and Town, 1999).

Economist Stiglitz (1999, p. 27) had stated that ‘Knowledge and information [are] being produced today like cars and steel were produced a hundred years ago’, reflecting a factory-like conceptualisation of universities. Within this paradigm, knowledge can be easily commodified and education framed as an objectified investment, with skills valued primarily as ‘capacities that contribute to economic growth’ (Stiglitz, 1999). From a critical perspective, this economistic framing diminishes the civic and democratic dimensions of education. Giroux (2011, p. 45) argued that interrogating how power circulates through such dominant discourses, which marginalise economically and racially oppressed youth, is essential to challenging ‘regressive social policies that undermine … education’ and its promise of pluralised democracy. Thus, the neoliberal paradigm, reinforced by government policies and economists, is critiqued by critical scholars for intensifying competition and inequality in the UK higher education system, reframing the public good of education as a private commodity and narrowing pedagogical focus to what is measurable and profitable (Ball, 2012).

In addition to market logic, UK pedagogical frameworks often operate within a rationalist and individualised discourse. Scholars in critical studies argue that this rational-centric pedagogy renders and reproduces rigid legitimacies of being dispassionate, objective, and governed by generalised reasoning and elite universalism (Harding, 1991). Scientific rationality and linear logic are valued above other epistemologies, which can result in privileging Western knowledge systems and marginalising experiential, indigenous, or emotional knowledge (Boler, 1999). Foucault’s (2002) influence is evident in critiques of academic dominant discourse: While universities present themselves as spaces of open enquiry, they frequently reproduce societal power hierarchies under the guise of neutrality. Read (2023, p. 3) further conceptualises the university as a heterotopia (after Foucault, 1978), a space that ‘implicitly represent[s] and legitimise[s] established dynamics of power’ related to ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality, even as it ostensibly stands apart from society.

Possible repercussions I: exclusion and democracy’s regression

Prioritising a linear, value-free model over a more pluralistic debate in the classroom can produce many unintended, yet profound, social consequences. First, this narrow focus tacitly endorses the pre-existing power structures that critical pedagogy seeks to challenge. By emphasising efficient outcomes and operational measures, education transforms into a setting that reproduces social hierarchies rather than interrogating them (Giroux, 2011). For instance, a metrics-driven approach to student assessment may disadvantage learners whose strengths lie in critical reflection, narrative analysis, and/or creative synthesis—competencies that are difficult to quantify but are essential for democratic citizenship (Biesta, 2007).

Second, value-free exercises risk fostering epistemic injustice. As Fricker (2007) argued, when certain ways of knowing, particularly those rooted in lived experience or community traditions, are devalued, dissonant groups are silenced and their knowledge rendered invisible. In HE systems, this can result in the de-legitimation of locally derived knowledge, thereby reinforcing colonial legacies of exclusion, as Harrison and Clarke (2022) suggested, within and beyond the classroom.

Third, essentialist and positivist paradigms tend to treat identities as fixed and decontextualised, simplifying the complexity of diverse human lives (Hesse-Biber, 2017). Liasidou (2012, p. 168) noted a ‘belated interest in questioning normative assumptions’ only after such assumptions have already shaped exclusionary policy. When disability, ethnicity, or gender are considered innate rather than a social construct, students lose the opportunity to understand the process of identities that can be negotiated within social practice (Ainscow, 2005), and instead, recognise the socially marginalised burden as an individual accountability.

Finally, privileging technocratic decision-making in schools can normalise state and corporate surveillance. In the name of evidence-based science or policy, teachers risk becoming data collectors rather than facilitators of dialogue, turning classrooms into sites of compliance rather than critical enquiry (Apple, 2018). In the context of fundamental British values (FBV), scholars in critical ethnicity and multicultural education highlight a policy paradox: framed as safeguarding, the FBV agenda positions teachers as quasi-security operatives and forecloses genuine discussion of difference (Elton-Chalcraft et al., 2017). In short, while purporting to universalise civic virtues rooted in Western norms, such approaches often narrow the scope of cultural literacy and encourage navigational strategies that mark marginalised identities (O’Neill, 2025), including Black students (Osbourne et al., 2023) and minority ethnic students (Chiu et al., 2025), as perpetual outsiders or as possessing only conditional belonging within the UK HE system.

Possible repercussions II: intersectional exclusions via digital pedagogy

Neoliberal market-driven pedagogical logic can be intensified in digital pedagogical settings. Within UK higher education, platforms such as MS Teams, LinkedIn, and Zoom are widely considered professional and convenient, yet they can compound marginalisation when students’ academic performance is shaped by unequal digital access and literacy. For example, this inequality affects those in rural, disadvantaged households (Treanor and Troncoso, 2022) and older learners (mature students) who are insufficiently equipped with digital competence and sociality (Nor, 2011; Kara et al., 2019; Homer, 2022). Hence, socio-economic and age-based disparities translate into unequal opportunities to access and engage with digital tools, leading to stratified patterns of academic achievement.

As digital environments are not immune to power dynamics rooted in physical environments (Bell, 2001), digital pedagogies may reproduce dominant cultures of surveillance, self-branding, and image commodification. Students, for instance, are encouraged to present marketable selves on LinkedIn, often underpinned by gendered and sexualised norms, while incidents of harassment and objectification have been documented across learning platforms (Karami et al., 2020). Critiques of postfeminism (Banet-Weiser et al., 2020) further articulate how neoliberal ethics in digital realms frame gender and sexuality as commodities to be marketed, consumed, and regulated, even in educational realms, often with little attention to collective responsibility, consent, or safeguarding. These patterns underscore the need for digital literacy education, covering etiquette, performance, and critical awareness. This education is essential to ensure that students, who are vulnerable to dominant norms, do not internalise risk-laden objectifying narratives about bodies and minds.

Recent studies also report that online teaching can operate exclusively for international, ethnically minoritised, Muslim, and LGBTQ+ students. First, online teaching often embeds surveillance-by-design through remote proctoring or camera-on expectations. Empirical research shows measurable disparities in automated proctoring systems: facial detection and identity checks fail more often for students with darker skin tones (and can misread gender/sexual presentation), creating friction at the gateway to assessment (Yoder-Himes et al., 2022). Across various contexts, students report switching cameras off for reasons of privacy, anxiety, and safety concerns linked to home circumstances, cultural-religious norms, gender/sexual identity safety, and bandwidth constraints (Uygur and Kahyaoğlu Erdoğmuş, 2025; Gherheș et al., 2021). Visibility mandates can undermine well-being, reproduce inequities, and create hierarchies of visual idealism, which is the opposite of fostering inclusion (Jayasundara et al., 2023).

International students are also more easily marginalised in online discussions, assessment, and peer networks when native-speaker fluency, dominant cultural references, and individualised accountability are treated as the norm (Dennen et al., 2024). Research on female Arab students’ experiences with Zoom teaching highlights the tensions around social presence, comfort with video, and culturally specific expectations of modesty and domestic privacy (Assaly and Atamna, 2023). For LGBTQ+ students, digital learning intersects with safety in two directions. First, remote study can eliminate access to campus-based safety nets and confidential spaces (Kwapisz et al., 2024). Second, the broader shift to digital monitoring risks profiling that may harm student well-being (Tanni et al., 2024).

Altogether, these confluences disrupt the authentic participation of students facing intersectional marginalisation in online discussions. These discussions need to be more inclusive and co-designed, requiring an intentional digital pedagogy (Isbell et al., 2023). In the absence of these efforts, educational environments risk reinforcing broader social conditions of fragmentation, insecurity, and mistrust, as warned by Zygmunt Bauman (Best, 2020).

Future suggestions: radical empathy pedagogy and praxis

This section proposes four pragmatic strategies for embedding intersectionality and radical empathy into higher education pedagogy, offering readers practical examples to contextualise these frameworks within their own educational settings in the near future. By integrating these concepts into curriculum design and pedagogical practice, educators can facilitate reflective learning that challenges structural injustices, cultivates critical reflexivity, and fosters inclusive, justice-oriented educational environments.

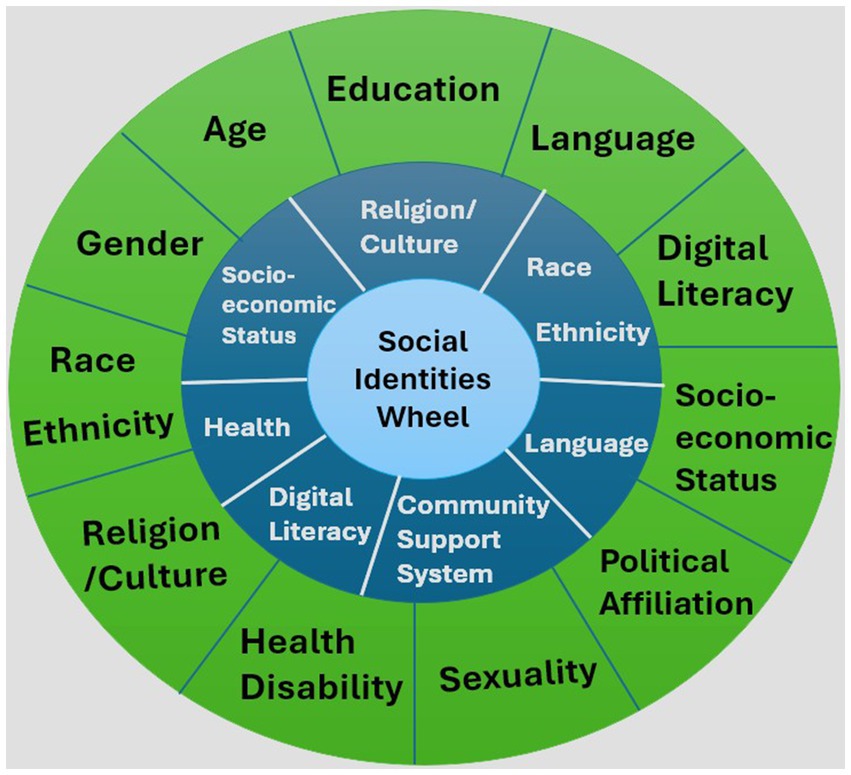

Grounded on Goffman’s (1969) dramaturgy theory, four kinds of pragmentic strategies are suggested, reflecting intersectionality and radical empathy within the classroom. For instance, a visualised tool, social identity wheels1 (Figure 1), enables students to assume diverse social roles and imagine complex situational dynamics.

First, Dialogic Case Libraries, derived from the concept of layered narratives (Bell, 2020 [2010]), function as practical pedagogical tools for deepening intersectional understanding. By assembling anonymised first-person narratives that illustrate intersecting forms of marginalisation—across age, gender, ethnicity, class, health, and language—educators can design interactive activities that promote deeper analysis, role-play, and critical policy discussion. For example, I drew upon a friend’s case involving cross-identities as a disabled queer South Asian Muslim male PhD student navigating gender-affirming healthcare in the UK. This approach enabled me, in my role as a tutor-researcher, to collaboratively draft proposals for integrating new readings, reflective exercises, and inclusive assessment tasks, thereby embedding intersectionality as a sustained pedagogical commitment rather than a tokenistic inclusion.

Second, Rigorous Positional Self-Interrogation requires systematic reflection on one’s social location, privileges, and internalised biases. Reflexive empathy is not instinctive; it must be consciously cultivated through structured, sustained engagement and training. This aligns with hooks’s (1994) concept of ‘engaged pedagogy’, which emphasises educators’ critical self-reflection on the power dynamics they bring into classroom environments. Similarly, Collins (2000 [2009]) argued that unexamined standpoints limit an individual’s ability to interpret others’ experiences. I used this self-interrogation through annotated positionality statements, peer-facilitated feedback circles, and reflexive journaling, which supported me as a learner and educator in tracing how my multiple identities shape my interpretations, responses, and interactions. By incorporating these methods, the classroom can become a space of mutual reflexivity and ethical engagement.

Third, Attentive Listening Practice foregrounds intersectional voices through the principle of radical empathy, requiring deliberate, sustained engagement with narratives, highlighting intersecting marginalisation. As Ahmed (2014 [2004]) observed, emotions circulate within social structures, shaping and being shaped by dominant narratives. Engaging critically with emotionally charged stories around ethnicity, gender, class, and sexuality is thus essential for dismantling normalised discourses that sustain entrenched power structures. In the qualitative method workshop, incorporating first-person testimonies, such as memoir excerpts by raped women of colour or multimedia narratives from disabled trans youth, allowed students to apprehend the layered complexities of intersectional oppression. Such activities transform listening into an active, ethical practice of recognition and accountability.

Finally, Transformative Collective Action is crucial to the praxis of radical empathy, aligning with Guajardo et al.'s (2008) notion of education as a (re)constructive pathway to social justice. Freire’s (2000 [1970]) concept of conscientisation underscores that critical awareness realises its transformative potential only through collective and practical action. Within this framework, classroom dialogues evolve into collaborative projects such as curriculum redesign, policy advocacy, and student-led initiatives that address systemic inequalities. For instance, my students in a qualitative method course co-designed intersectional health modules, proposed gender-inclusive policy changes, and/or delivered community workshops on digital sexual citizenship. These collective endeavours amplified marginalised voices and promoted structural transformation, realising the inherent emancipatory potential in radical empathy.

Similar examples are as follows:

• Empathy workshops with reflective storytelling: Art-based methods suggested by Leavy (2015 [2009]) and storytelling approaches by Bell (2020 [2010]) support multimedia workshops in which students produce digital diaries, collages, or short films expressing their positionalities. Peers practise radical listening, foregrounding questions of power and representation over personal interpretation.

• Community-engaged projects: Scottish partnerships with social care organisations—LGBT Youth Scotland for young people aged 13–25; Unity (asylum seekers organisation), a volunteer-based centre in Glasgow; and Hemat Gryffe Women’s Aid for minority ethnic communities—enable co-authored projects. Students collaboratively develop awareness campaigns and educational materials grounded in intersectional research and radical empathy principles (Case, 2017).

Concluding remarks

From the outset, this study has examined how educators can authentically engage with contentious contexts shaped by intersectional marginalisation: the overlapping and compounding forms of exclusion structured through age, ethnicity, class, religion, gender, sexuality, health status, and other dimensions of difference. Returning to this question, the discussion has demonstrated that integrating intersectionality as an analytical framework with radical empathy as a pedagogical praxis can reposition higher education from a site of normative reproduction to one of critical social transformation. Rather than preparing students to conform to neoliberal or market-oriented expectations, educators should cultivate learners’ capacities for deep listening, critical reflexivity, and collective ethical action. These pedagogical orientations allow students to recognise how power operates through knowledge systems, institutional structures, and identity hierarchies. As a result, classrooms become dialogic spaces for exploring relationality, ethical accountability, and social imagination, as Noddings (1984) reminded us.

As Greenwood and Ferrie (2025) suggested, autoethnographic approaches that interweave educators’ experiences with those of marginalised learners reveal both the limits and possibilities of contemporary higher education. Within such spaces, radical empathy moves beyond sentimentality. Through deliberate engagement with intersectional narratives, radical empathy enables classrooms to function as emancipatory microcosms—sites where silenced voices are recognised and where emotional and intellectual labour intersect to challenge epistemic hierarchies.

Nevertheless, such practice requires vigilance, as Ahmed (2012) warns that institutionalised, tokenistic deployments of intersectionality risk diluting its transformative power, and as Zembylas (2012) cautioned against empathy’s reduction to superficial emotional display. To avoid these pitfalls, aligning with the stance of Greenwood and Ferrie (2025), it is imperative to anchor pedagogy in feminist and decolonial frameworks and link self-reflection to structural critique, positioning radical empathy as disruption—unsettling epistemic comfort and inviting ethical risk for justice.

In conclusion, within a neoliberal academy marked by commodification, algorithmic governance, and global precarity, it is essential to adopt a socio-politically engaged and culturally responsive pedagogy. Embedding radical empathy within intersectional analysis equips educators and students to resist normative hierarchies, contest intersectional exclusion, and build the relational capacities needed for plural, inclusive, democratic learning. Although this study was grounded in the UK higher education settings, these suggestions may be globally transferable as identity configurations become more complex: sustained attention to intersectional marginalisation can turn classrooms into laboratories of empathy, equity, and democratic renewal. Future research should test the impacts of these interventions on attitudes, cultural practices, and policy, building the evidence to reshape the landscape of intersectional, justice-oriented pedagogies across contexts and realise higher education’s transformative potential.

Author contributions

SA: Project administration, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to express my gratitude to colleagues who provided valuable comments during a conference at the University of Glasgow, where the initial ideas for this paper were developed, as well as to the reviewers whose insightful feedback helped strengthen the rigor of the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer AF declared a shared affiliation with the author to the handling editor at the time of review.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was utilised in the preparation of this manuscript solely for proofreading purposes and for assisting in the visualisation of the concept depicted in Figure 1.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^The University of Michigan’s Program on Intergroup Relations (IGR) and the Spectrum Centre refined the worksheet and posted it openly on their LSA Inclusive Teaching site, helping the term go mainstream in higher-education DEI training.

References

Ahmed, S. (2012). On being included: Racism and diversity in institutional life. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ainscow, M. (2005). Developing inclusive education systems: what are the levers for change?J. Educ. Change 6, 109–124. doi: 10.1007/s10833-005-1298-4

Ali, S. (2022). Managing racism? Race equality and decolonial educational futures. Br. J. Sociol. 73, 923–941. doi: 10.1111/1468-4446.12976

Assaly, I., and Atamna, U. (2023). Who needs zoom? Female Arab students’ perceptions of face-to-face learning and learning on zoom. Sustainability 15:8195. doi: 10.3390/su15108195

Ball, S. J. (2012). Global education Inc.: New policy networks and the neoliberal imaginary. London: Routledge.

Banet-Weiser, S., Gill, R., and Rottenberg, C. (2020). Postfeminism, popular feminism and neoliberal feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in conversation. Fem. Theory 21, 3–24. doi: 10.1177/1464700119842555

Bell, L. A. (2020 [2010]). Storytelling for social justice: connecting narrative and the arts in antiracist teaching. London; New York, New York: Routledge.

Best, S. (2020). Zygmunt Bauman on education in liquid modernity. New York; Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Biesta, G. (2007). WHY "what works" won't work: evidence-based practice and the democratic deficit in educational research. Educ. Theory 57, 1–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-5446.2006.00241.x

Chiu, Y.-L. T., Wong, B., Murray, Ó. M., Horsburgh, J., and Copsey-Blake, M. (2025). I deserve to be here’: minority ethnic students and their conditional belonging in UK higher education. High. Educ. doi: 10.1007/s10734-025-01469-1

Collins, P. H. (2000 [2009]). Black feminist thought: knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. London; New York: Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: a black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chicago Legal Forum 1989:Article 8.

Dennen, V., Choi, H., He, D., and Arslan, Ö. (2024). Course design, belonging, and learner engagement: meeting the needs of diverse international students in online courses. TechTrends 68, 922–935. doi: 10.1007/s11528-024-00983-w

Elton-Chalcraft, S., Lander, V., Revell, L., Warner, D., and Whitworth, L. (2017). To promote, or not to promote fundamental British values? Teachers' standards, diversity and teacher education. Br. Educ. Res. J. 43, 29–48. doi: 10.1002/berj.3253

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gherheș, V., Șimon, S., and Para, I. (2021). Analysing students’ reasons for keeping their webcams on or off during online classes. Sustainability 13:3203. doi: 10.3390/su13063203

Givens, T. E. (2021). Radical empathy: finding a path to bridging racial divides. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

Greenwood, S., and Ferrie, J. E. (2025). Making space for positionality stories in higher education: using embodied feminist and critical pedagogies in practice. Teach. High. Educ. 30, 1546–1555. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2025.2487763

Guajardo, M., Guajardo, F., and Casaperalta, E. C. (2008). Transformative education: chronicling a pedagogy for social change. Anthropol. Educ. Q. 39, 3–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1492.2008.00002.x

Harding, S. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge?: Thinking from women’s lives. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Harrison, N., and Clarke, I. (2022). Decolonising curriculum practice: developing the indigenous cultural capability of university graduates. High. Educ. 83, 183–197. doi: 10.1007/s10734-020-00648-6

Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2017). The practice of qualitative research: Engaging students in the research process. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Homer, D. (2022). Mature students’ experience: a community of inquiry study during a COVID-19 pandemic. J. Adult. Contin. Educ. 28, 333–353. doi: 10.1177/14779714221096175

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: education as the practice of freedom, vol. 17. New York: Routledge, 270–271.

Isbell, D. R., Kremmel, B., and Kim, J. (2023). Remote proctoring in language testing: implications for fairness and justice. Lang. Assess. Q. 20, 469–487. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2023.2288251

Jayasundara, J., Gilbert, T., Kersten, S., and Meng, L. (2023). Why should i switch on my camera? Developing the cognitive skills of compassionate communication for online group/teamwork management. Front. Psychol. 14:1113098. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1113098

Kara, M., Erdogdu, F., Kokoç, M., and Cagiltay, K. (2019). Challenges faced by adult learners in online distance education: a literature review. Open Praxis 11, 5–22. doi: 10.5944/openpraxis.11.1.929

Karami, A., White, C. N., Ford, K., Swan, S., and Yildiz Spinel, M. (2020). Unwanted advances in higher education: uncovering sexual harassment experiences in academia with text mining. Inf. Process. Manag. 57:102167. doi: 10.1016/j.ipm.2019.102167

Kwapisz, M. B., Kohli, A., and Rajivan, P. (2024). Privacy concerns of student data shared with instructors in an online learning management system. In: Proceedings of the 2024 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, pp. Article 661. Association for Computing Machinery.

Lather, P. (2007) Getting lost: Feminist efforts toward a double(d) science. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Leavy, P. (2015 [2009]). Method meets art: arts-based research practice. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Liasidou, A. (2012). Inclusive education and critical pedagogy at the intersections of disability, race, gender and class. J. Crit. Educ. Policy 10:168. Available online at: https://jceps.com/archives/698/

Martinussen, M., and Lahiri-Roy, R. (2025). The politics of intersectional (un)belonging: a duoethnographic mapping study with academic women. Gend. Educ., 1–19. doi: 10.1080/09540253.2025.2546055

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: a feminine approach to ethics & moral education. London; Berkeley: University of California Press.

Nor, N. M. M. (2011). Understanding older adult learners in distance education: the case of Universiti Sains Malaysia. Turk. Online J. Distance Educ. 12, 229–340. Available online at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Understanding-Older-Adult-Learners-In-Distance-The-Nor/463fbddd3501dc8dfc47abd33e8fe3decd9205db

O’Neill, S. (2025). Racially minoritised students’ strategies for navigating and resisting racism in higher education. Ethnic Racial Stud. 48, 997–1018. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2024.2337047

Osbourne, L., Barnett, J., and Blackwood, L. (2023). Black students' experiences of “acceptable” racism at a UK university. J. Community Appl. Soc. Psychol. 33, 43–55. doi: 10.1002/casp.2637

Prior, L., Evans, C., Merlo, J., and Leckie, G. (2024). Sociodemographic Inequalities in Student Achievement: An Intersectional Multilevel Analysis of Individual Heterogeneity and Discriminatory Accuracy (MAIHDA). Sociol. Race Ethn. 11, 351–369. doi: 10.1177/23326492241267251

Quinlivan, K., and Town, S. (1999). Queer pedagogy, educational practice and lesbian and gay youth. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 12, 509–524. doi: 10.1080/095183999235926

Read, B. (2023). The university as heterotopia? Space, time and precarity in the academy. Access 11, 1-11. Available online at: https://novaojs.newcastle.edu.au/ceehe/index.php/iswp/article/view/192 (Accessed November 02, 2025).

Şahin, M. (2018). Essentialism in philosophy, psychology, education, social and scientific scopes. J. Innov. Psychol., Educ. Didact. 22, 193–204. Available online at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED593579.pdf

Sellars, M., and Imig, S. (2021). School leadership, reflective practice, and education for students with refugee backgrounds: a pathway to radical empathy. Intercult. Educ. 32, 417–429. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2021.1889988

Serra Undurraga, J. K. A. (2025). Once you see it, you cannot unsee it: the contradictions of ‘decolonising’ in the UK university. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2025.2539368

Shlasko, G. D. (2005). Queer (v.) pedagogy. Equity Excell. Educ. 38, 123–134. doi: 10.1080/10665680590935098

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonising methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. London [England]: Zed Books.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1999). “Knowledge as a global public good” in Global public goods: International cooperation in the 21st century. eds. I. Kaul, I. Grunberg, and M. A. Stern (New York: Oxford University Press), 308–325.

Stonewall (2018) LGBT in Britain: University Report. Available online at: https://files.stonewall.org.uk/production/files/lgbt_in_britain_universities_report.pdf

Tanni, T. I., Akter, M., Anderson, J., Amon, M. J., and Wisniewski, P. J. (2024) Examining the unique online risk experiences and mental health outcomes of LGBTQ+ versus heterosexual youth. In: Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, pp.Article 867. Association for Computing Machinery.

Treanor, M., and Troncoso, P. (2022). Digitally excluded: inequalities in the access and use of online learning technologies in Scottish secondary schools. Int. J. Popul. Data Sci. 7:48. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v7i3.1819

Uygur, S. S., and Kahyaoğlu Erdoğmuş, Y. (2025). (In)visible students: investigating why students turn off their cameras during live lessons. Int. J. Educ. Res. 132:102638. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2025.102638

Yoder-Himes, D. R., Asif, A., Kinney, K., Brandt, T. J., Cecil, R. E., Himes, P. R., et al. (2022). Racial, skin tone, and sex disparities in automated proctoring software. Front. Educ. 7, 7–2022. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.881449

Keywords: radical empathy, intersectionality, decolonial and feminist pedagogy, inclusive practices, cultural intelligence, UK higher education

Citation: Ahn SH (2025) Radical empathy as pedagogical praxis: an intersectional feminist approach to building inclusive curriculums and societies. Front. Educ. 10:1683896. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1683896

Edited by:

Veruska De Caro-barek, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, NorwayReviewed by:

Ailsa Foley, University of Glasgow, United KingdomCopyright © 2025 Ahn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sun Ha Ahn, cy5haG4uMUByZXNlYXJjaC5nbGEuYWMudWs=; c3N1bmhhMDIxNUBsaXZlLmNvbQ==

Sun Ha Ahn

Sun Ha Ahn