- 1Department of Psychology, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nuremberg, Germany

- 2Gifted Education Program, Department of Special Education, College of Education, Administrative and Technical Sciences, Arabian Gulf University, Manama, Bahrain

- 3Department of Special Education, Faculty of Education, Arish University, El-Arish, Egypt

- 4Faculty of Media, Ansbach University of Applied Sciences, Ansbach, Germany

This study explores a resource-based perspective on subjective wellbeing in educational contexts by introducing the concept of happiness capital. Building on the educational and learning capital approach, we adapted existing measures to assess how personal and environmental resources contribute to students’ wellbeing. In a sample of 1,528 Egyptian secondary school students, perceived happiness capital significantly predicted life satisfaction, positive and negative emotions across all age groups. These findings suggest that the same resource structures supporting learning can foster emotional flourishing. We briefly discuss implications for resource-based models of wellbeing in education and propose directions for future research.

1 Introduction

This paper presents preliminary findings from an empirical study that explores a resource-based perspective on subjective wellbeing (SWB) in educational contexts. Following Su et al. (2014), we conceptualize SWB as a multidimensional construct encompassing life satisfaction, positive and negative emotions, as assessed by the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT).

A resource-based view of SWB posits that individuals experience greater wellbeing when they can access and mobilize personal and environmental resources that support happiness. While this idea resonates with broader frameworks such as the conservation of resources theory (COR) (Hobfoll, 1989), it remains underutilized in educational research. Recent theoretical developments further highlight the relevance of resource-based models for educational contexts. In particular, the Academic and Social–Emotional Flourishing Framework (ASEFF, Collie and Martin, 2024) integrates insights from motivational and social–emotional theories to emphasize how contextual and personal resources jointly contribute to students’ academic and emotional flourishing. ASEFF delineates adaptive and maladaptive pathways based on resource and demand structures, offering a comprehensive student development model. Our study aligns with this broader movement by proposing a more targeted operationalization of resources for SWB through the concept of “happiness capitals,” adapted from the educational and learning capital approach (ECLA, Ziegler et al., 2019).

Originally developed to explain the conditions for advanced learning, ECLA defines 10 resource types—five personal (learning capital) and five contextual (educational capital)—that jointly shape learning outcomes. However, the theory explicitly allows applying these resource categories to other goals.

This study proposes that each of these 10 capitals can be reinterpreted as a “happiness capital”—a resource that supports SWB in educational settings. Although the outcome shifts from academic achievement to wellbeing, the structure of relevant resources remains the same. For example, social capital may foster positive emotions through feelings of connectedness, while telic (motivational) capital may enhance life satisfaction by sustaining meaningful goal pursuit. Infrastructural and economic capitals can buffer against negative emotions by providing stability and predictability in students’ lives. The examples illustrate how the structure of the ECLA is sufficiently general to be redirected toward wellbeing, thereby offering a theoretically grounded yet flexible framework for modeling resource-based flourishing in educational contexts.

The present study explores the applicability of the ECLA as a learning resource-based framework to SWB in educational contexts. By proposing the concept of “happiness capitals,” we seek to contribute to the conceptual foundation of resource-based models of SWB in educational contexts.

2 Method

2.1 Sample

With the permission of the relevant ministry, N = 1528 Egyptian students from the Cairo region participated in the anonymized questionnaire and gave their informed consent. All students were educated in public schools. There were 47% female and 53% male students in the study. Based on the age distribution of the students, there were three approximately equal subsamples of 16-year-olds (n = 510), 17-year-olds (n = 511), and 18-year-olds (n = 508).

2.2 Measurement instruments

When translating the instruments, we adapted the scales in accordance with the recommendations of the International Examinations Committee for use in environments other than those in which the scale was originally developed (Hernández et al., 2020). This involved initial translation from English into Arabic, followed by reverse translation from Arabic into English. Experts reviewed the translations to avoid linguistic and cultural bias.

2.2.1 Subjective wellbeing

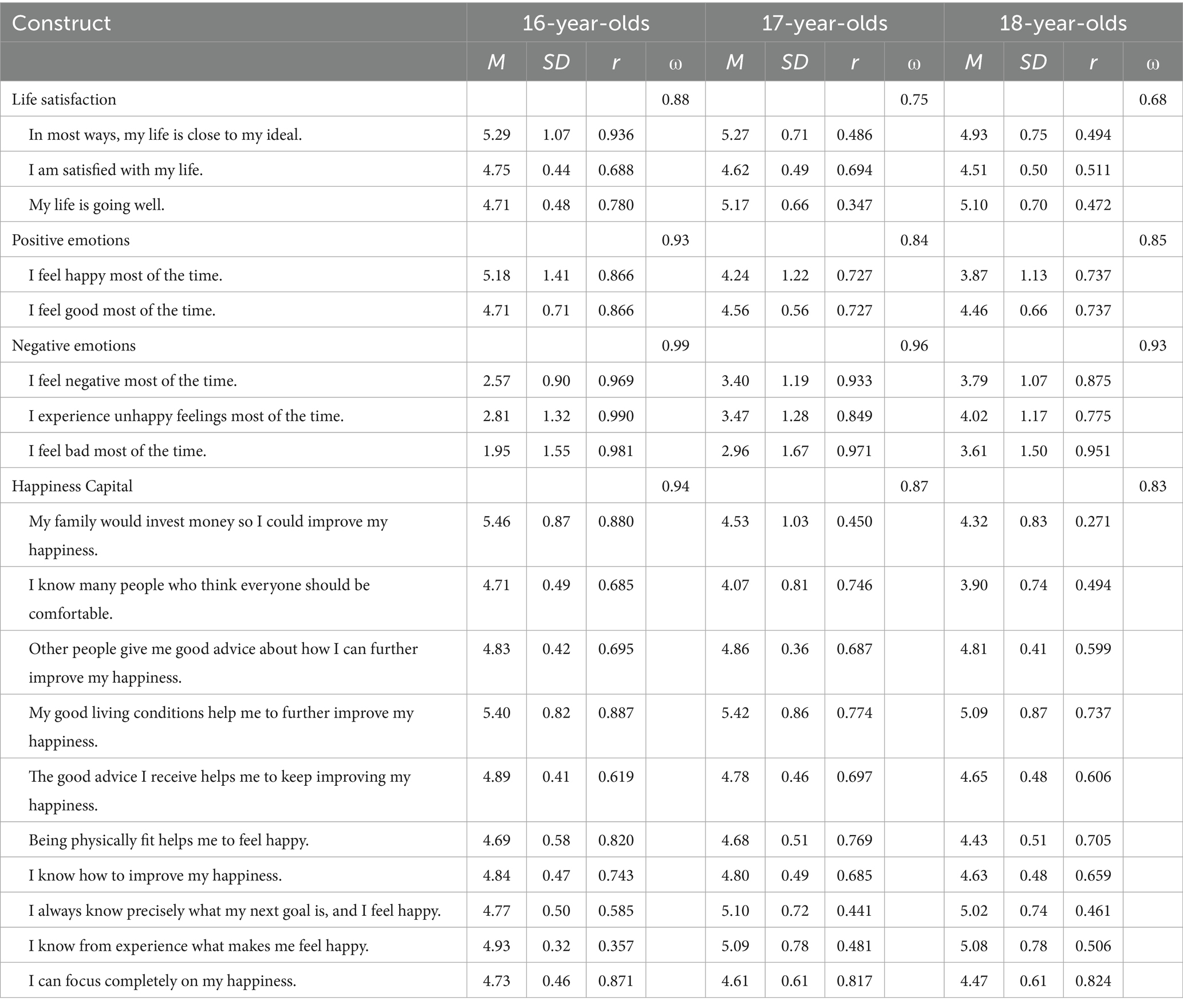

To assess students’ SWB, we implemented three subscales of the CIT (CIT, Su et al., 2014). The three subscales, life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions, represent the subconstruct of SWB. Students answered three items per scale and indicated their agreement with statements regarding the measured construct on a 6-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat disagree, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = agree, and 6 = strongly agree. Despite satisfying scores for internal consistency in the original publication, the scale on positive emotions showed low reliability scores across all age groups (see Table 1). Taking a closer look at the items, the problems emerged from low correlations between two items of the scale that can be traced back to a low range of students’ answers (3–5). Therefore, we calculated the following analysis using a modified scale for positive emotions with two items, and the first item of the original scale was removed.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables and items (M, SD), corrected item-total correlations (r), and reliability coefficients (α) in the three age groups.

2.2.2 Happiness capital

Happiness capital was assessed via an adaption of the established Questionnaire of Educational and Learning Capital (QELC) (Vladut et al., 2013). The original QELC asked students to rate the availability of educational and learning resources as a means of their learning progress. The questionnaire is based on the Actiotope Model of Giftedness (Ziegler and Baker, 2013) and distinguishes 10 learning resources (termed capitals) that need to be available and used by students to enable optimal learning (see Table 2). In the current study, students selected the extent to which they agreed with the items on a 6-point Likert scale, where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = somewhat disagree, 4 = somewhat agree, 5 = agree, and 6 = strongly agree. All items were written in a positive voice, meaning that responses of 4 to 6 corresponded with increased availability of the corresponding capital. The QELC has been validated across numerous cultures and age groups of students (Paz-Baruch, 2015; Leana-Taşcılar, 2016; Coronel et al., 2021; Gari et al., 2021; Lafferty et al., 2021; Mendl et al., 2021). In the current adaption of the QELC to happiness, the resources are means to experiencing happiness rather than learning success, as seen in the items in Table 1. The construct showed sufficient overall reliability, and McDonald’s omega indicated a one-factor solution with one item for each resource, ω = 0.86. Additionally, it showed good internal consistency across all age groups (see Table 1).

2.3 Data analysis

To take into account the ordinal scale level of the collected data, the relationships between happiness capital and the three aspects of SWB were analyzed using path analyses. The robust weighted least square estimator WLSMV, which is recommended for ordinal data, was used for this purpose. Since some response categories were empty in certain age groups, a measurement invariance test was not recommended, as too much information would have been lost due to the collapse of the response options. Therefore, a separate path model was calculated for each age group. In order to control for other factors influencing SWB, a binary gender variable and the students’ performance in Arabic were included in the model as covariates. The analyses were performed in R version 4.5.1 and using the lavaan package.

3 Results

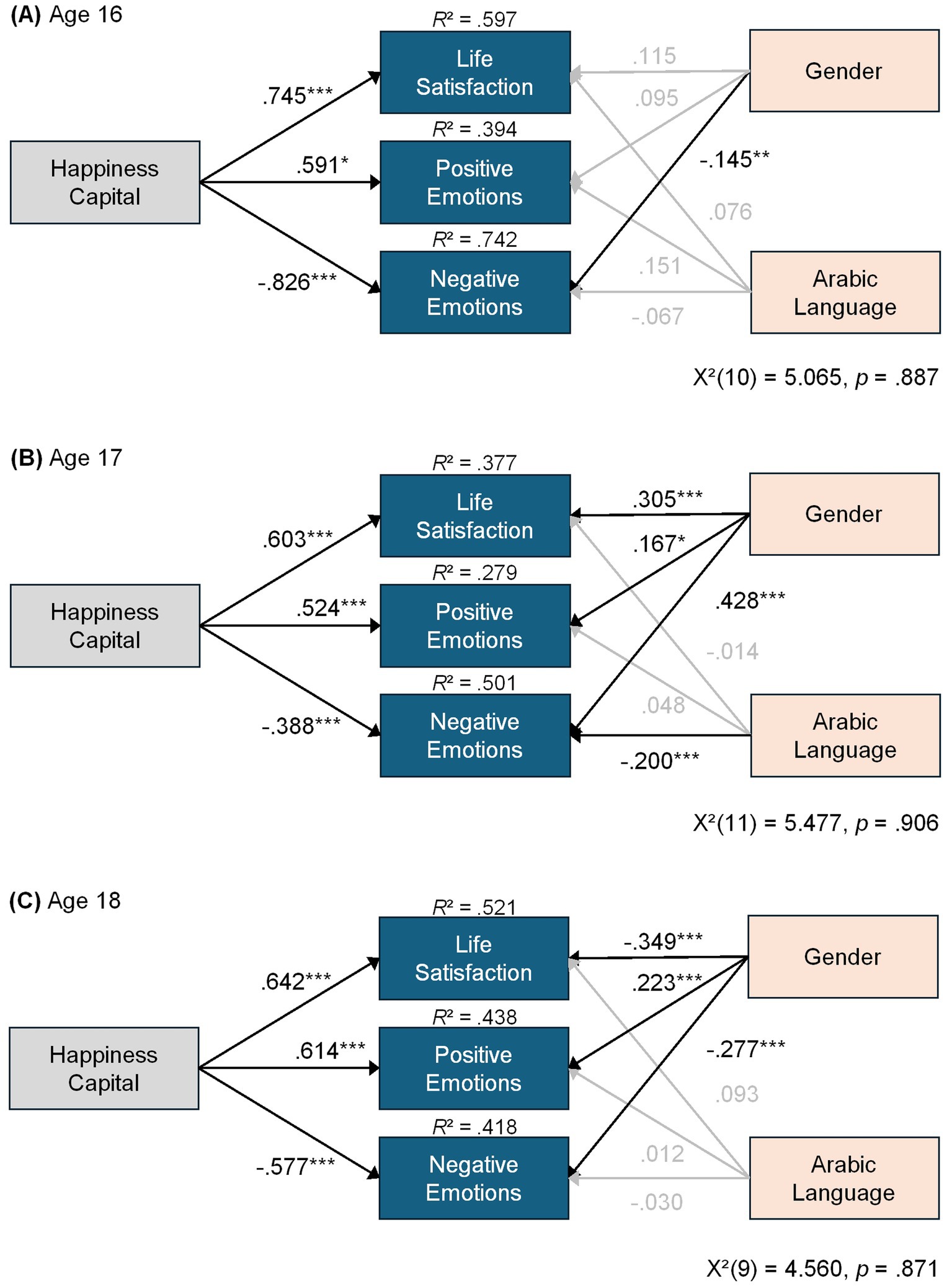

Across all three age groups (16-, 17-, and 18-year-olds), perceived happiness capital significantly predicted the three SWB dimensions of life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions (see Figure 1). With a higher perceived availability of resources for their happiness, Egyptian adolescents in Cairo also reported greater satisfaction with their lives, experienced more positive emotions, and less negative emotions. Exact p-values and standard errors of the estimates can be found in the Supplementary material. Overall, all models showed appropriate fit, and happiness capital explained a substantial proportion of variance in the SWB factors, indicating a strong role of personal and environmental resources during early adolescence in Cairo schools (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Path analyses regarding happiness capital (IV), subjective wellbeing (DV), and gender and performance in the subject Arabic language (covariates) with standardized path coefficients. (A) Age 16. (B) Age 17. (C) Age 18. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, gray paths are nonsignificant.

The covariates showed differential effects (see Figure 1). Only gender showed a significant negative relation to the experience of negative emotions among 16-year-olds. Therefore, the female students in the sample were more likely to experience more negative emotions. Seventeen-year-old boys in our sample showed significantly higher life satisfaction and experienced significantly more positive and negative emotions than their female counterparts. Among the 18-year-old girls, life satisfaction was significantly higher, but they also experienced more negative emotions than boys of their age. The only significant path regarding performance in the subject Arabic became visible among the 17-year-old students, who experienced significantly fewer negative emotions as their performance in Arabic improved.

4 Discussion

By reconceptualizing educational and learning capital as happiness capital, we showed in a first empirical exploration that the same categories of resources facilitating learning may also support SWB. These relationships were also significant in the context of adolescents in urban schools in Cairo, even when controlling for relevant covariates of SWB such as gender (Momin and Rolla, 2024), which underscores the relevance of resources in this setting. These findings also resonate with broader theoretical perspectives that underscore the role of resources in promoting wellbeing. Specifically, ASEFF (Collie and Martin, 2024) posits that adaptive academic and social–emotional outcomes emerge from mobilizing personal and contextual resources. The happiness capital framework introduced here provides a focused operationalization within this broader paradigm, highlighting how 10 categories of resources—initially developed for learning—can also foster emotional and psychological flourishing. We offer a multilevel view that links general psychological mechanisms with specific educational applications by connecting our empirical findings to both the COR (Hobfoll, 1989) and ASEFF (Collie and Martin, 2024). Future research may build on this approach by exploring how different forms of capital interact over time to support academic success and emotional flourishing, aligning resource-based interventions with the broader goals of holistic student development. Although the validity and completeness of the theoretically proclaimed capitals can be guaranteed based on the items used in this study, future research faces the challenge of further developing the measuring instrument so that the factorial structure can also be statistically tested. To this end, the authors recommend using more items (at least four) per capital to enable clearer distinctions. An analysis of the data structure using rating scale models could also prove useful in connection with the expansion of the measuring instrument (Alamer et al., 2023). Furthermore, the generalizability of the study’s results is limited by its cross-sectional design and the restriction of the sample to students from urban schools in Cairo. Future studies that seek to examine the results in other contexts and samples should pursue longitudinal approaches in order to more accurately examine the assumed directions of effect between happiness capital and SWB. As a conclusion, just as resources can cultivate learning, they may also cultivate happiness.

Data availability statement

The raw data on which the conclusions of this article are based will be made available by the authors upon request without undue reservations.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg Institutional Review Board Educational Psychology. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

AZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. AI: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. YE: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. NN-S: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SB: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI was used for translation purposes.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1684397/full#supplementary-material

References

Alamer, S. M., Phillipson, S. N., Phillipson, S., and Al Fafi, A. I. (2023). The Saudi gifted educational and learning environment: parents and student perspectives. High Abil. Stud. 34, 109–130. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2022.2072273

Collie, R. J., and Martin, A. J. (2024). The academic and social-emotional flourishing framework. Learn. Individ. Differ. 114:102523. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2024.102523,

Coronel, G. E. O., Sierra, M. D. V., Heredia, M. E. R., Garduño, M. L. V., González, Ó. U. R., and Balderrama, J. F. (2021). Validation of the educational and learning capital questionnaire (QELC) on the Mexican population. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 63, 227–238.

Gari, A. D., Mylonas, K., Nikolopoulou, V., and Mrvoljak, I. (2021). Educational and learning resources in a Greek student sample: qELC factor structure and methodological considerations. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 63, 205–226.

Hernández, A., Hidalgo, M., Hambleton, R., and Gómez-Benito, J. (2020). International test commission guidelines for test adaptation: a criterion checklist. Psicothema 3, 390–398. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2019.306,

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 44, 513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513,

Lafferty, K., Phillipson, S. N., and Costello, S. (2021). Educational resources and gender norms: an examination of the actiotope model of giftedness and social gender norms on achievement. High Abil. Stud. 32, 171–187. doi: 10.1080/13598139.2020.1768056

Leana-Taşcılar, M. Z. (2016). Turkish adaptation of the educational-learning capital questionnaire: results for gifted and non-gifted students. Gift. Talented Int. 31, 102–113. doi: 10.1080/15332276.2016.1305863

Mendl, A., Harder, B., and Vialle, W. (2021). Moderating effects of educational and learning capital on the consequences of performance feedback. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 63, 239–269.

Momin, M. M., and Rolla, K. P. (2024). Exploring the multi-faceted nature of wellbeing across genders: evaluating the antecedence of psychological capital and life satisfaction. Gend. Issues 41:11. doi: 10.1007/s12147-024-09328-6

Paz-Baruch, N. (2015). Validation study of the questionnaire of educational and learning capital (QELC) in Israel. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 57, 222–235.

Su, R., Tay, L., and Diener, E. (2014). The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving and the brief inventory of thriving. Appl. Psych Health Well 6, 251–279. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12027

Vladut, A., Liu, Q., Leana-Tascila, M., Vialle, W., and Ziegler, A. (2013). A cross-cultural validation study of the questionnaire of educational and learning capital (QELC) in China, Germany and Turkey. Psychol. Test Assess. Model. 55, 462–478.

Ziegler, A., and Baker, J. (2013). “Talent development as adaption: the role of educational and learning capital” in Exceptionality in East-Asia: Explorations in the Actiotope model of giftedness. eds. H. Phillipson, H. Stoeger, and A. Ziegler (London, UK: Routledge), 18–39.

Keywords: subjective well-being, learning resources, happiness, actiotope, multivariate regression

Citation: Ziegler A, Bakhiet SFA, Issa ANA, Essa YAS and Naujoks-Schober N (2025) Happiness capital: resources for student wellbeing. Front. Educ. 10:1684397. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1684397

Edited by:

Aikaterini Vasiou, University of Crete, GreeceReviewed by:

Mujtaba Momin, American University of the Middle East, KuwaitMarcin Kolemba, Faculty of Education University of Bialystok, Poland

Copyright © 2025 Ziegler, Bakhiet, Issa, Essa and Naujoks-Schober. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Albert Ziegler, YWxiZXJ0LnppZWdsZXJAZmF1LmRl

Albert Ziegler

Albert Ziegler Salaheldin Farah Attallah Bakhiet

Salaheldin Farah Attallah Bakhiet Ahmed Nabawy Abdou Issa3

Ahmed Nabawy Abdou Issa3 Yossry Ahmed Sayed Essa

Yossry Ahmed Sayed Essa Nick Naujoks-Schober

Nick Naujoks-Schober