- 1Chengdu Aeronautic Polytechnic University, Chengdu, Sichuan, China

- 2Institute of Education, Xiamen University, Xiamen, Fujian, China

- 3Library of Qinghai University, Qinghai University, Xining, China

- 4School of International Education, Qinghai Minzu University, Xining, China

To explore the formation mechanism of college students' adoption intention of generative artificial intelligence (GAI)—i.e., the dynamic paths of direct/indirect effects of antecedent variables and interaction effects of moderating variables—this study integrates and extends the traditional Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2). The integration is necessary because traditional TAM focuses on rational cognition, while UTAUT2 lacks the emotional dimension in educational scenarios and the integration of multi-level contexts. A theoretical framework incorporating the “individual-family- institution-region” four-dimensional moderating and collaborative perspective was constructed, and an empirical analysis was conducted using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). A multi-stage stratified sampling method was adopted, with a sample of 842 college students from five universities in eastern and western China. The scales for UTAUT2 core variables and extended TAM variables in the questionnaire were adapted from previous studies that had undergone reliability and validity verification. Reliability was tested using Cronbach's α and Composite Reliability, while validity was tested using Average Variance Extracted, the Fornell-Larcker criterion, and Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio. Results showed that the measurement model had acceptable reliability and validity, with good explanatory power (R2 = 0.743) and predictive validity of the structural model. Specifically, perceived comfort (β = 0.112, p < 0.005), perceived security (β = 0.109, p < 0.05), and emotional dependence (β = 0.497, p < 0.005) all exerted positive effects on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Performance expectancy (β = 0.216, p < 0.005), social influence (β = −0.064, p < 0.05), facilitating conditions (β = 0.143, p < 0.005), and perceived ease of use (β = 0.469, p < 0.005) directly drove adoption intention, whereas the direct effect of perceived usefulness was not significant (β = −0.031, p = 0.523). This result challenges the core assumption of TAM—which emphasizes “priority of rational utility” and confirms the “de- instrumentalization” characteristic of generative AI adoption, meaning user decisions rely more on emotional experience and interactive fluency.Regarding moderating effects: gender negatively moderated the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = −0.207, p < 0.05); family structure negatively moderated the relationship between habit and adoption intention (β = −0.228, p < 0.05); university type positively moderated the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = 0.251, p < 0.05); and regional differences negatively moderated this relationship (β = −0.251, p < 0.05).In practice, it is suggested that educational authorities strengthen the construction of digital infrastructure in western universities, universities develop differentiated guidance strategies for students majoring in humanities/social sciences and science/engineering, and developers optimize emotional interaction design. This study provides theoretical support for context-adapted strategies for the educational application of generative AI.

1 Introduction

Generative artificial intelligence (GAI) has become a key technological driver of the new round of technological revolution (Alalaq, 2024) and is promoting structural transformations in the educational ecosystem and learning paradigms. Its ability to deconstruct and reorganize knowledge in the field of higher education can provide core support for the design of personalized learning paths for college students and interdisciplinary knowledge production (Tariq, 2024). The McKinsey Global Institute predicts that by 2030, this technology will create economic value of $2.6 trillion to $4.4 trillion globally, among which the education sector will become a core value area due to its knowledge-intensive nature (Matyushok et al., 2021; Pedro et al., 2019). This prediction underscores that, as core participants in the digital transformation of higher education, the adoption intention of “digital native” college students toward GAI not only directly determines the improvement of individual learning efficiency but also affects the scale and depth of value creation in the education sector (Kumar et al., 2024). In 2024, the total number of college students in China exceeded 48.46 million, with a gross enrollment rate of 60.80% (Feng and Li, 2025). The technology acceptance behavior of this large group is a key variable for the success of educational digital transformation.

Despite the broad application prospects of GAI, its promotion in higher education institutions still faces three types of significant barriers that can be clearly mapped to the core constructs of the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2 (UTAUT2).

Among them, technical barriers manifest as insufficient accuracy in natural language interaction and limited in-depth understanding of professional domain knowledge (Shrivastava, 2025), which directly corresponds to the “perceived ease of use” construct of TAM. Such technical limitations significantly increase the effort cost for college students to use GAI, thereby reducing their perceived ease of use of GAI; meanwhile, doubts about the information authenticity of generated content and the resulting academic integrity risks (Ziqi et al., 2024)are directly related to the extended “perceived security” variable in this study, and such risks will further exacerbate users' concerns about technology reliability. Sociocultural barriers are mainly reflected in the potential anxiety of students regarding technology replacing traditional teaching models (Henderson and Corry, 2021), as well as the differentiation in acceptance of GAI across different disciplines, which corresponds to the “social influence” construct of UTAUT2. The attitude tendencies of teachers and students and the implicit norms at the disciplinary level will significantly shape college students' adoption intention of GAI through the dual mechanism of “authoritative demonstration-peer imitation.” Institutional barriers manifest as the general lack of clear usage norms and ethical guidelines for GAI at the university level (Pushpanadham and Sarpong, 2024), which corresponds to the “facilitating conditions” construct of UTAUT2. The absence at the institutional level leaves college students without clear guidance when using GAI, which not only increases practical usage barriers but also further weakens their perception of the facilitating conditions for GAI use.

Against this background, existing studies still struggle to uncover the “black-box mechanism” of college students' GAI adoption behavior. Theoretically, this “black box” is specifically reflected in the fact that the anthropomorphic interaction characteristics of GAI have given rise to a “cognition-emotion” dual-driven adoption logic. However, existing studies have neither integrated the multi-level synergy of “individual cognition-meso environment-macro environment” nor incorporated the emotional dimension into the theoretical framework, making it difficult to explain the contradictory phenomenon where some college students recognize the utility of GAI but refuse to use it due to emotional discomfort or environmental constraints. Therefore, constructing a systematic theoretical framework that integrates multi-level factors and the emotional dimension has become the key to unlocking this “black box.”

Academically, the three unique characteristics of GAI—generativeness, interactivity, and emergence— determine that the traditional TAM/UTAUT2 models must undergo systematic expansion. Specifically, “interactivity” constructs a “quasi-social partner” relationship through anthropomorphic interfaces, giving rise to emotion-driven variables such as “perceived comfort” and “emotional dependency,” while the traditional TAM/UTAUT2 models only focus on rational cognitive dimensions such as perceived usefulness and cannot cover such emotional factors; meanwhile, the “generativeness” characteristic leads to prominent risks of content reliability and privacy security, requiring the addition of the “perceived security” variable to address users' risk perception needs; in addition, “emergence” enables AI functions to continuously optimize during use, so it is necessary to combine the core “habit” variable of UTAUT2 with environmental constraints such as family resources and regional infrastructure to explain the differences in the formation of usage inertia among different groups. These characteristics all exceed the explanatory boundaries of traditional models, and systematic expansion is urgently needed to adapt to the technical attributes of GAI.

Practically, the academic value of in-depth exploration of key variables and moderating effects needs to be closely aligned with the actual national conditions of Chinese higher education. There are significant imbalances in regional development, differences in family structures, and differentiation in university types in the field of Chinese higher education. Such national conditions highlight the key value of moderating effects (gender, family structure, university type, region). For example, the weak digital infrastructure of western universities may weaken the driving effect of “facilitating conditions” on adoption intention, and the device sharing situation in multi-child families may reduce the impact intensity of “habit.” If these moderating effects are ignored, relevant policy formulation and product design will fall into the dilemma of “one-size-fits-all.” Therefore, conducting moderating effect analysis based on the Chinese context is a core prerequisite for ensuring that practical recommendations have localized adaptability and accuracy.

In recent years, research on GAI acceptance has made phased progress in the technical dimension (Mutlu, 2024; Yilmaz et al., 2024), but there are still obvious theoretical limitations, specifically reflected in three aspects: firstly, the research paradigm shows a “two-dimensional” tendency, focusing only on the two dimensions of individual cognition and technical attributes, while ignoring the role of meso and macro environmental variables such as family, institution, and region; secondly, it generally ignores the emotional dimension implied by the interactive characteristics of GAI and fails to incorporate emotional variables such as perceived comfort into the theoretical analysis framework; thirdly, it mostly presupposes the homogeneity of influence paths and lacks systematic exploration of the moderating effects of demographic variables and contextual variables, making it difficult to explain the heterogeneity of adoption intention among different groups.

The “individual-family-institution-region” four-dimensional collaborative framework constructed in this study achieves breakthroughs in the traditional TAM/UTAUT2 models in three aspects (as shown in Figure 1). Firstly, it breaks through the “individual-technology” dual perspective and incorporates family resource endowments, institutional academic ecology, and regional digital infrastructure into the analysis model, filling the theoretical gap of the long-term absence of environmental variables; secondly, it expands the “emotion-cognition” dual-driven antecedent system and introduces variables such as perceived comfort, perceived security, and emotional dependency, making up for the neglect of the emotional dimension in traditional models; thirdly, it systematically reveals multi-level moderating effects and explains the heterogeneous characteristics of adoption intention among different groups, breaking through the homogeneity assumption of traditional models. Empirically, this study focuses on three aspects of analysis: revealing the transmission mechanism of emotion-cognition variables through mediating effect tests, quantifying the direct effect intensity of core variables such as performance expectancy, and systematically testing the mechanism of action of four types of moderating variables. Finally, the study provides practical recommendations closely linked to core variables for educational authorities, universities, and technology developers.

2 Theoretical foundation

2.1 Technology acceptance model (TAM)

This study is based on Davis' classic Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Chiu, 2025; Davis, 1989), retaining its two core constructs—perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Meanwhile, combining the anthropomorphic interaction characteristics of GAI and the needs of higher education scenarios, three extended variables—perceived comfort, perceived security, and emotional dependence—are introduced. The selection of these variables is not random but based on the logical extension of TAM constructs and the empirical needs of adoption intention in higher education scenarios, with specific arguments as follows.

Perceived comfort refers to users' comprehensive evaluation of GAI's interface friendliness, interaction fluency, and emotional resonance ability (Aggarwal et al., 2025). Its logical connection with TAM constructs is reflected in two aspects: on the one hand, it directly enhances perceived ease of use by reducing cognitive load. In higher education scenarios, when college students use GAI to complete tasks such as literature reviews and assignment assistance, if GAI interactions conform to the logic of academic expression and error feedback is inclusive, it will significantly reduce the extra effort required to “learn to use the tool” (Istiqomah and Alfansi, 2024); on the other hand, it indirectly strengthens perceived usefulness by improving trust. Empirical studies in Chinese universities show that when college students perceive GAI interactions as “non-oppressive,” their utility judgment that “GAI can continuously assist academic studies” increases (Bai and Wang, 2025), which verifies the driving effect of comfort on perceived usefulness.

Perceived security focuses on users' trust in GAI's data privacy protection, content reliability, and ethical compliance (Wang L. et al., 2025), and it is a key variable to fill the “lack of risk perception” in the TAM model. In the dimension of perceived usefulness, when college students use GAI to generate academic content, concerns about “content plagiarism markers” or “personal thesis data leakage” will directly negate the academic value of GAI. Empirical data show that only a small number of college students are willing to use AI without traceability functions to assist in thesis writing, while the usage rate of AI with content traceability functions is relatively high (Chen, 2025); in the dimension of perceived ease of use, high security can reduce additional operations for “verifying content authenticity.” Existing studies have confirmed that students with stronger security perceptions have significantly higher evaluations of AI's “ease of use” than those with security concerns (Wilson et al., 2021).

Emotional dependency reflects the deep psychological connection between users and GAI (Huang and Huang, 2025), and its connection with TAM constructs conforms to the “long-term learning” characteristic of higher education. On the one hand, long-term use of GAI to obtain personalized support will form “usage inertia,” making college students perceive that “there is no need to re-adapt to other tools,” thereby strengthening perceived ease of use (Wang, 2024); on the other hand, this dependency will be transformed into “utility recognition.” A survey conducted by a Chinese university shows that students who use GAI to assist learning more than five times a week have a 41% higher evaluation of perceived usefulness than occasional users due to “relying on its academic support” (Yang, 2025), which proves that emotional dependency is an important antecedent of TAM's core constructs (Nafees and Sujood, 2025). In summary, through the “emotion-cognition” dual pathway, the three extended variables make the TAM model more in line with the characteristics of “academic needs-risk concerns-long-term use” in higher education scenarios, rather than being limited to the simple instrumental rationality decision-making logic.

2.2 Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology 2

The adoption of GAI in educational scenarios needs to break through the limitations of UTAUT2 in consumer scenarios (Tang et al., 2025). The original version of this model (Venkatesh et al., 2012) includes seven constructs: performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, habit, price value, and hedonic motivation. Combining educational scenarios and the characteristics of Chinese samples, this study realizes model adaptation through “eliminating redundant constructs+emotion-cognition integration.” Specifically, firstly, redundant constructs are clearly eliminated, with the core basis being in line with the scenario characteristics of Chinese college students using GAI. Among them, the “price value” construct focuses on users' trade-off between technology costs and benefits, but this study focuses on college students' use of free/open-source AI tools. Chinese universities mostly provide free AI access resources through campus networks, so students have no economic cost pressure (Day, 2024), thus this construct is irrelevant to adoption decisions (Ongaro, 2015); the “hedonic motivation” construct refers to users' sense of pleasure in using technology, but in higher education scenarios, the core goal of college students using generative GAI is to improve academic performance rather than entertainment. A survey of 10 Chinese universities confirms that the explanatory power of hedonic motivation for the adoption intention of educational GAI is only 4.2%, which is far lower than that of performance expectancy (31.5%) (Liu et al., 2025), so it is also eliminated.

Secondly, the “emotion-cognition” cluster formed by integrating “perceived comfort, perceived security, and emotional dependency” strengthens the explanatory power of UTAUT2 in the Chinese educational context from three aspects, conforming to the learning environment and cultural characteristics of Chinese college students. Firstly, it adapts to the high academic pressure of Chinese college students, who face multiple pressures such as course papers, scientific research training, and employment preparation (Huang et al., 2024), and their demand for “completing tasks efficiently” is much higher than that of ordinary consumers. The emotion-cognition integration optimizes the “performance expectancy” construct of UTAUT2 through “perceived comfort reducing anxiety”; secondly, it responds to the dual influence system of Chinese families and schools—family resources and school norms have a significant impact on students' behavior (Wang et al., 2019), emotional dependency can capture “usage inertia under family support,” and perceived security conforms to school academic requirements (Sun Q. et al., 2025); thirdly, it fits the “trust-oriented” culture of Chinese education—Chinese students pay more attention to technology reliability and authoritative recognition, and the emotion-cognition integration makes the “social influence” construct of UTAUT2 more persuasive, filling the gap of “lack of emotional mediation in social influence.”

The adapted UTAUT2 framework forms a tripartite pathway of “rational decision-making (performance expectancy, facilitating conditions)—normative influence (social influence)—emotional experience (comfort, security, dependency)”. It not only retains the systematic explanatory power of the original model but also accurately conforms to the characteristics of Chinese higher education scenarios, providing a more suitable theoretical tool for the analysis of generative AI adoption mechanisms.

3 Research hypotheses development

3.1 Perceived comfort

As a key dimension of emotional experience, perceived comfort essentially reflects users' comprehensive evaluation of the interface friendliness, interaction fluency, and emotional resonance ability of AI systems (Dave et al., 2023). The rationality of including it in research hypotheses is supported by empirical studies in Chinese universities. When perceived ease of use is comparable, GAI systems that provide emotional feedback during interactions lead to a higher adoption intention among students than those without such feedback (Zhang and Wang, 2025). Additionally, students with higher perceived comfort scores exhibit a greater frequency of using GAI to support their academic pursuits (Gai, 2024). This result confirms the unique driving effect of perceived comfort on continuous usage behavior. Specifically, when students perceive that AI interaction meets the physiological comfort threshold and psychological comfort zone, the sense of emotional relaxation will significantly enhance their subjective perception of the technology's ease of use (Istiqomah and Alfansi, 2024; Topsakal, 2025); at the same time, the low-pressure interaction process will strengthen students' trust that “AI can continuously assist academic studies,” thereby improving perceived usefulness (Siu and White, 2025). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a. Perceived comfort positively affects perceived ease of use;

H1b. Perceived comfort positively affects perceived usefulness.

3.2 Perceived security

Perceived security focuses on “specific perceived risk of GAI in educational scenarios,” specifically covering three dimensions: data privacy, content reliability, and ethical compliance (Kim, 2025; Zhao et al., 2025). Its specific relevance to GAI applications in educational scenarios is confirmed by empirical studies. Survey data from Chinese universities reveals that 83% of students refuse to use GAI tools for academic paper writing that lack a “data encryption” function (Xiao et al., 2025), with their primary concern being “personal papers being used for model training.” Additionally, 76% of students majoring in humanities and social sciences explicitly deny the academic value of AI-generated content due to its “lack of citation sources (Zou et al., 2025).” These results indicate that perceived security is not a subordinate concept of general trust, but rather a critical antecedent condition for college students' GAI “perceived usefulness” in educational scenarios (Kim et al., 2025).

Perceived security affects GAI adoption decisions through the dual pathways of technology trust and risk avoidance (Zhang, 2024). When students are convinced that GAI can protect the privacy of thesis data and ensure the traceability of generated content, their psychological defense mechanism will be significantly weakened, and they will be more inclined to actively explore GAI functions; at the same time, low perceived risk can reduce the cognitive anxiety of “verifying content authenticity,” indirectly improve the fluency of human-computer interaction, and thus strengthen the perceived ease of use of the technology (Deng et al., 2025). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2a. Perceived security positively affects perceived ease of use;

H2b. Perceived security positively affects perceived usefulness.

3.3 Emotional dependency

The core of emotional dependency is the “deep psychological connection” between users and GAI (Wang, 2024). The rationality of regarding it as a core construct is reflected in two aspects: firstly, its strong correlation with continuous usage behavior; secondly, the risk of excessive dependency can be avoided through institutional guidance. From the perspective of continuous usage behavior, a longitudinal study conducted in Chinese universities shows that students who perceive GAI as a “learning partner” use it more frequently than those who view it merely as a “tool” (Wu H. et al., 2025). Furthermore, students with high emotional dependency on GAI demonstrate a greater depth of exploration into GAI functions. This result confirms the driving effect of such perception and emotional dependency on adoption intention.

By identifying the influence path of emotional dependency, targeted guidance strategies can be formulated. Emotional dependency affects cognitive evaluation through two pathways: firstly, it strengthens identity, making students more likely to perceive the academic value of GAI, thereby improving perceived usefulness (Naseer et al., 2025); secondly, it shortens the psychological distance, making users ignore initial operation obstacles and focus on interaction fluency instead, thus improving perceived ease of use (Guo, 2025). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a. Emotional dependency positively affects perceived ease of use;

H3b. Emotional dependency positively affects perceived usefulness.

3.4 Perceived ease of use

Perceived ease of use is users' subjective perception of the “effort cost required to use GAI” (Chiu, 2025; Davis, 1989). The three unique characteristics of GAI—natural language interaction, personalized response, and scenario- based adaptation—have fundamentally reshaped the perception of ease of use in higher education scenarios (Salammagari and Srivastava, 2024). Traditional technologies require learning professional skills, while GAI can complete tasks through dialogue, greatly reducing learning costs (Chen et al., 2024).

Specifically, the reshaping effect of GAI's characteristics on the perception of ease of use is reflected in three aspects: firstly, natural language interaction eliminates the “technical threshold”—students in humanities and social sciences can let GAI generate a literature review framework through daily language instructions without learning code (Tu and Chen, 2025); secondly, personalized response adapts to academic scenarios, avoiding the reduction of perceived ease of use due to professional barriers (Chiu, 2025); thirdly, the fast response speed meets the time constraints of college students under high-intensity academic tasks (Yin et al., 2025). When students perceive that the GAI interface is friendly, responses are timely, and tasks such as knowledge retrieval and content generation can be completed without mastering advanced technologies, their psychological resistance during use will be significantly reduced (Koroleva and Jogezai, 2025). Studies have shown that GAI with high perceived ease of use can reduce the time students spend on completing assignments. The characteristic of “seamless integration into the learning process” directly strengthens adoption intention. Meanwhile, the technology anxiety theory suggests that perceived ease of use can alleviate the anxiety of “being unable to use GAI,” thereby further promoting adoption intention (Kim et al., 2025). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H4. Perceived ease of use positively affects adoption intention.

3.5 Perceived usefulness

Perceived usefulness refers to students' subjective belief in “GAI's ability to improve academic outcomes” (Sun J. et al., 2025). Its theoretical basis needs to be strengthened through measurable student outcomes rather than relying on generalized “utility perception,” specifically covering four quantifiable dimensions: thesis completion efficiency, assignment quality, exam scores, and research capabilities (Zou et al., 2025). Empirical studies show a significant positive correlation between perceived usefulness and student outcomes (Yang et al., 2025).

In the context of GAI, perceived usefulness is specifically manifested as students' expected utility of GAI in promoting core learning goals (Eaton-Merkle, 2024)—for example, GAI effectively addresses academic pain points such as low literature review efficiency and difficulty in interdisciplinary knowledge integration by accurately locating research materials, generating multi-dimensional thesis frameworks, and simulating interdisciplinary debates (Namatovu and Kyambade, 2025). When students expect GAI to bring the above measurable academic outcomes, their adoption intention will be significantly enhanced (Hu L. et al., 2025). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5. Perceived usefulness positively affects adoption intention.

3.6 Performance expectancy

The conceptual difference between performance expectancy and perceived usefulness lies in category granularity. Perceived usefulness refers to a macro judgment of GAI's “overall academic value” (Koroleva and Jogezai, 2025), while performance expectancy focuses on specific expectations of GAI's “direct performance contribution” (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024). For example, a student may recognize GAI's “overall value” but hesitate to use it due to uncertainty about whether it can improve scores on a specific exam—this phenomenon confirms that the two need to be included in the analysis as independent constructs.

The empirical correlation between performance expectancy and adoption intention has been supported by studies on GAI adoption intention (Wang X. et al., 2025; Zheng et al., 2024). Research analysis shows that the impact coefficient of performance expectancy on GAI adoption intention is significantly higher than that of perceived usefulness (Mwakapesa, 2025). Studies by Chinese scholars also indicate that students who clearly recognize that “using GAI can improve academic performance” have a higher adoption rate than those without clear performance expectations (Cao and Wang, 2025). For college students, performance expectancy specifically covers three dimensions: firstly, efficiency improvement; secondly, quality optimization; and thirdly, capability adaptation (Sewandono et al., 2023). When students perceive that GAI features such as autonomous content generation and multi-modal interaction can directly reduce cognitive load and improve academic performance, their adoption intention will be significantly enhanced (Du and Lv, 2024). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6. Performance expectancy positively affects adoption intention.

3.7 Social influence

Social influence can be decomposed into three levels: peer influence, teacher influence, and institutional influence (Liu, 2025). The mechanism of action and empirical evidence of each level are different, collectively forming normative pressure in higher education scenarios. Among them, peer influence functions through the “observational learning” mechanism—if roommates or classmates frequently use GAI to assist learning (Korchak et al., 2025), it will trigger students' “imitation impulse”; teacher influence takes effect through the “authoritative demonstration” mechanism—when teachers use AI to explain knowledge points in class, it strengthens students' perception of GAI's “legitimacy”; institutional influence exerts its role through the “institutional support” mechanism—if universities provide GAI usage training and formulate ethical norms, it can reduce technical uncertainty (Nguyen et al., 2025). The influence of these three levels all contains implicit pressure, which collectively strengthens students' AI adoption intention (Silalahi, 2024). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H7. Social influence positively affects adoption intention.

3.8 Facilitating conditions

Facilitating conditions refer to students' perception of “infrastructure and support required for GAI use” (Sergeeva et al., 2025). China's unbalanced regional development and differences in university resources make facilitating conditions a key environmental variable affecting GAI adoption. From the perspective of the digital divide, the 5G coverage rate on the campuses of eastern universities reaches 98%, and laboratories are equipped with GAI-specific terminals; in contrast, the 5G coverage rate of some western universities is only 65%, and students need to rely on personal devices to access AI with a high network lag rate. Relevant surveys show that eastern students' scores on “resource accessibility” are significantly higher than those of western students. From the perspective of institutional readiness, facilitating conditions also include technical support and institutional guarantees; in universities that do not provide such training, students may give up using AI because they “do not master prompt usage methods”.

In addition, family resources also have a moderating effect on facilitating conditions—students from multi-child families need to share devices with family members, so the convenience of “using GAI at any time” is significantly lower than that of students from one-child families (Tian et al., 2024). Facilitating conditions enhance students' perception of control by eliminating usage barriers, thereby directly driving GAI adoption intention (Emon, 2023). Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H8. Facilitating conditions positively affect adoption intention.

3.9 Habit

Habit refers to the “unconscious behavioral tendency to use GAI repeatedly,” and its formation mechanism must be confirmed through specific academic scenarios of GAI rather than generalized “usage inertia.” For example, high-frequency scenarios such as students using GAI to query professional course knowledge points every day, revise course papers with GAI every week, and organize exam key points with GAI before exams will gradually solidify usage behavior into a habit (Tang et al., 2025). Habit also interacts with other constructs, specifically manifested in two aspects: firstly, it forms a positive cycle with perceived ease of use—students with stronger habits are more proficient in use, so they are more likely to perceive GAI's “ perceived ease of use,” thereby increasing usage frequency (Bendary and Al-Sahouly, 2018); secondly, it produces a synergistic effect with emotional dependence—students with strong habits and high emotional dependence will still maintain GAI usage behavior even in low-motivation scenarios, while students with weak habits are more likely to give up use. This mechanism of “scenario solidification-automation-synergistic reinforcement” makes habit an important factor driving GAI adoption intention. Based on the above analysis, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H9. Habit positively affects adoption intention.

3.10 Moderating variables

The selection of gender, family structure, university type, and region as moderating variables is supported by both theoretical and empirical evidence, and is highly consistent with the Chinese educational context. The gender difference theory in technology acceptance proposed by Venkatesh et al. (2012) points out that men pay more attention to the “functional utility” of technology, while women focus more on “emotion and social evaluation.” This theory has been empirically verified in the Chinese GAI context. In the context of Chinese universities, the impact of performance expectancy on adoption intention among male students is significantly higher than that among female students, while the impact coefficient of social influence among female students is significantly higher than that among male students; at the same time, Chinese female students pay more attention to GAI's “emotional security,” which further amplifies the moderating effect at the gender level, so it is included in the model.

Based on Marjoribanks (1991) resource dilution theory, resources in multi-child families will be dispersed, and the resource difference between “one-child” and “multi-child” families in China is particularly significant. The proportion of students from one-child families who own exclusive learning devices is higher than that of students from multi-child families, and students from multi-child families cannot form stable GAI usage habits because they “need to share devices with siblings,” resulting in the weakening of habit's impact on adoption intention. Therefore, family structure is included as a moderating variable.

The “academic cultural difference” between science and engineering universities and humanities and social sciences universities in China is prominent: science and engineering emphasize “instrumental rationality,” while humanities and social sciences pay more attention to “originality” (Xu, 2025). The impact coefficient of performance expectancy on adoption intention among science and engineering students is significantly higher than that among students in humanities and social sciences, while the impact coefficient of perceived security among students in humanities and social sciences is significantly higher than that among science and engineering students. This significant disciplinary difference makes university type a key moderating variable, so it is included in the model.

Combined with Sánchez-Torres' digital divide theory (Sánchez-Torres, 2019), the “digital infrastructure difference” between eastern and western universities in China is very prominent. The coverage rate of GAI laboratories in eastern universities is higher than that in western universities, and the score of eastern students on facilitating conditions is also higher than that of western students; moreover, the impact coefficient of performance expectancy on adoption intention among western students is higher than that among eastern students. Therefore, region is listed as a moderating variable.

In summary, these four types of moderating variables exert a moderating effect on the path relationship between core variables and adoption intention by shaping differentiated boundary conditions of “cognitive preference- resource constraint-environmental characteristic,” and their significance in the Chinese context has been supported by empirical evidence. Based on this, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H10. Gender, family structure, university type, and regional differences have partial moderating effects on the relationships between perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, performance expectancy, social influence, facilitating conditions, habit, and adoption intention.

4 Research instruments and data collection

4.1 Questionnaire design

Based on the UTAUT2 model proposed by Venkatesh et al. (2012) and the extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)(Davis, 1989), this study designed a structured questionnaire using the approach of “adapting mature scales + localized validation” to ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement tool and its adaptability to the context of GAI in education for Chinese college students. The questionnaire consists of three parts.

The first part is a research explanation, covering the research purpose, implementation process, and informed consent statement to protect respondents‘ right to information. The second part is a demographic information survey, involving variables such as gender, university type, region, and family structure, which provides data support for subsequent moderating effect analysis. The third part includes measurement items for latent variables, with a total of 44 items scored using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree). All items were adapted from existing mature scales and adjusted with localized expressions to fit the scenario of GAI assisting academic studies. The specific sources are as follows: performance expectancy (seven items), social influence (four items), facilitating conditions (three items), and habit (four items) were adapted from the UTAUT2 scale by Venkatesh et al. (2012); perceived usefulness (five items) and perceived ease of use (seven items) were adapted from Davis' TAM scale (Davis, 1989); perceived comfort (three items) referenced the research design by Siu and White (2025); perceived security (three items) referenced the scale by Balaskas et al. (2025); emotional dependency (four items) referenced the research by Sahin et al. (2022); and adoption intention (four items) referenced the scale by Shahzad et al. (2025a),b. To further enhance the content validity of the scale, all measurement items for latent variables in this study were referenced from mature domestic and international scales, with minor adjustments to fit the scenario of GAI in education. The original scale sources and reference items for each construct are shown in Table 1 below.

To further ensure the scale's adaptability to the cognitive characteristics and usage context of Chinese college students, a pre-survey was conducted in March 2025. One university each in Shandong and Qinghai (different from those in the formal survey) was selected to distribute 120 questionnaires, with 108 valid questionnaires recovered, resulting in an effective recovery rate of 90%. The questionnaire was optimized through three steps: 1. Item analysis: Items with a Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) < 0.5 were deleted; 2. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA): Results showed that the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of each latent variable was > 0.7, the p-value of Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was < 0.001, and the factor loadings of all items were >0.7, indicating good construct validity of the scale; 3. Reliability test: The Cronbach's α coefficient of each latent variable was > 0.7, confirming good internal consistency of the scale. After optimization through the pre-survey, the formal questionnaire was finally determined to consist of 44 items.

4.2 Data collection

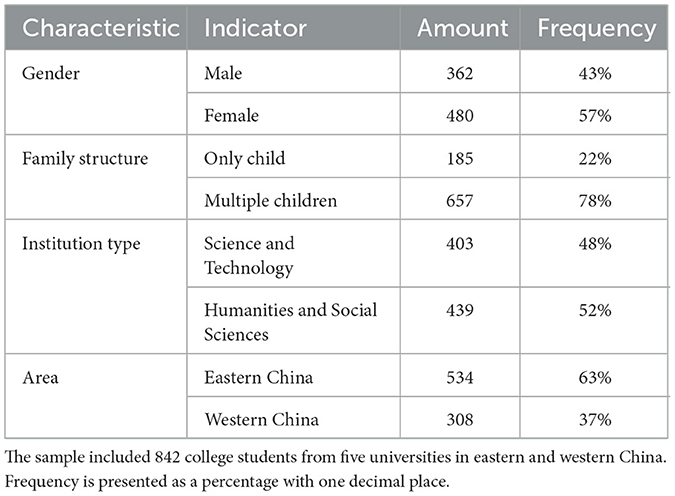

As shown in Table 2, this study conducted surveys in a total of five universities in eastern and western China (Eastern: Jining University, Qufu Normal University; Western: Qinghai University, Qinghai Normal University, Qinghai Minzu University). The selection of universities was based on three main considerations: firstly, to cover regional differences—eastern universities represent areas with well-developed digital infrastructure, while western universities represent areas with relatively limited resources, which is highly consistent with the research's need for the “region” moderating variable; secondly, to include diverse university types, covering normal universities (Jining University, Qufu Normal University, Qinghai Normal University), comprehensive universities (Qinghai University), and ethnic universities (Qinghai Minzu University). Universities with different orientations ensure sample disciplinary diversity, covering science and engineering, humanities and social sciences, and ethnic-related majors; thirdly, to ensure cooperation feasibility—all selected universities have research teams in educational technology or psychology, which can assist in questionnaire distribution and quality control, effectively avoiding sample bias that may occur in pure online surveys.

Sampling adopted a combination of multi-stage convenience sampling and random stratification, with the specific process as follows: In the first stage, 5 universities were selected based on cooperative relationships. Convenience sampling was mainly used because cross-regional joint surveys need to rely on internal university resources for implementation; in the second stage, stratified random sampling was conducted within each university by “grade (freshman to senior) × major (science and engineering/humanities and social sciences)” to ensure coverage of students from different grades and disciplines, thereby reducing sampling bias.

Data collection was carried out via the “Wenjuanxing” platform from April to May 2025. Before filling out the questionnaire, respondents were provided with detailed explanations of the research purpose, anonymity commitment, and filling guidelines through a pop-up window. Meanwhile, an online Q&A group with 10 researchers was established to answer respondents' questions in real time, avoiding data quality issues caused by misunderstanding. A total of 1,000 questionnaires were distributed in this survey. During the data cleaning stage, invalid questionnaires were excluded according to the following criteria: (1) completion time < 3 min; (2) obviously patterned responses; (3) key items left unanswered. Finally, 842 valid samples were obtained, with an effective recovery rate of 84%. The sample size adequacy test was based on the PLS-SEM sample size criterion proposed by Hair et al. (2021) (10 times the number of latent variable paths). There are 12 latent variable paths in this study, requiring a minimum sample size of 120. The actual valid sample size of 842 is far higher than this threshold, which can fully ensure the statistical power of model parameter estimation.

4.3 Sample characteristics and representativeness analysis

As shown in Table 3, the presented sample characteristics are highly consistent with the overall characteristics of the Chinese college student population in the 2024 National Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Education, which enhances the sample's representativeness and the research's validity. In summary, the sample is consistent with the characteristics of the national college student population in key demographic dimensions and has good representativeness, providing a basis for the generalization of the research conclusions.

5 Research results

As a multivariate statistical analysis method, Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) has many characteristics that align with this study. Firstly, the theoretical model constructed in this study involves a “individual-family-institution-region” four-dimensional moderating and collaborative perspective,resulting in a relatively complex overall structural model. PLS-SEM can effectively handle complex causal models containing multiple exogenous and endogenous variables, giving it an advantage in analyzing the complex interactive effects of multi-dimensional factors in this study. Secondly, in terms of data distribution, the data collected in actual surveys may not fully meet the strict assumption of normal distribution. PLS-SEM relaxes the requirement for data to be normally distributed and exhibits good estimation performance for non-normally distributed data, enabling it to provide reliable analysis results based on the data of this study. Thirdly, the purpose of this study is not only to explore the relationships between various factors but also to predict college students' adoption intention of GAI through the analysis results, thereby providing theoretical references for policymakers and developers to design context-adapted strategies, which is clearly prediction-oriented. PLS-SEM takes prediction as its core goal, finding the optimal predictive model paths and parameter estimates by minimizing the sum of squared prediction errors, which can better achieve the prediction-oriented analysis purpose of this study. In summary, PLS-SEM's advantages in handling complex models, adapting to non-normally distributed data, and meeting the needs of prediction-oriented analysis make it a reasonable and effective method for this study to analyze the formation mechanism of college students' adoption intention of generative artificial intelligence.

5.1 Measurement model test

The measurement model test is a key step to ensure the theoretical consistency and validity of the relationship between latent variables and observed indicators. This study uses PLS-SEM for the test, a method particularly suitable for complex models and small-sample analysis. It can strictly control measurement errors and verify theoretical hypotheses, with the test process focusing on three dimensions: reliability, convergent validity (and content validity), and discriminant validity.

5.1.1 Reliability test

Reliability was evaluated using two indicators: Cronbach's α and Composite Reliability. As shown in Table 4, all constructs meet psychometric standards (Cronbach's α > 0.7, CR > 0.7), though there are differences in the strength of reliability among different constructs. Among them, performance expectancy has the strongest reliability, with Cronbach's α = 0.965 and CR = 0.966, indicating the best internal consistency and stability among its items. Perceived Comfort has the weakest reliability, with Cronbach's α = 0.709 and CR = 0.711, which is at the critical threshold of 0.7. As an emotional experience variable, its items involve subjective feelings, leading to relatively large individual differences and slightly lower reliability. However, this construct still needs to be retained, based on three core reasons: firstly, the items meet quality standards—during the pre-survey, the Corrected Item-Total Correlation (CITC) of this construct was all >0.5, and factor loadings were all >0.7, with no redundant items; secondly, content validity is matched—the items accurately cover two dimensions of “physical discomfort in interaction” and “psychological discomfort,” which is consistent with the theoretical definition of perceived comfort (Cao and Peng, 2024); thirdly, convergent validity is qualified—the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) of this construct is 0.632 > 0.5, and its discriminant validity with other constructs meets standards, with no cross-loading issues. From the overall reliability performance, except for perceived discomfort which is at the critical threshold, other constructs (such as emotional dependence and adoption intention) have Cronbach's α > 0.8 and CR > 0.8, indicating that the measurement tool of this study has excellent overall internal consistency and construct stability, which can meet the needs of subsequent empirical analysis.

5.1.2 Validity test

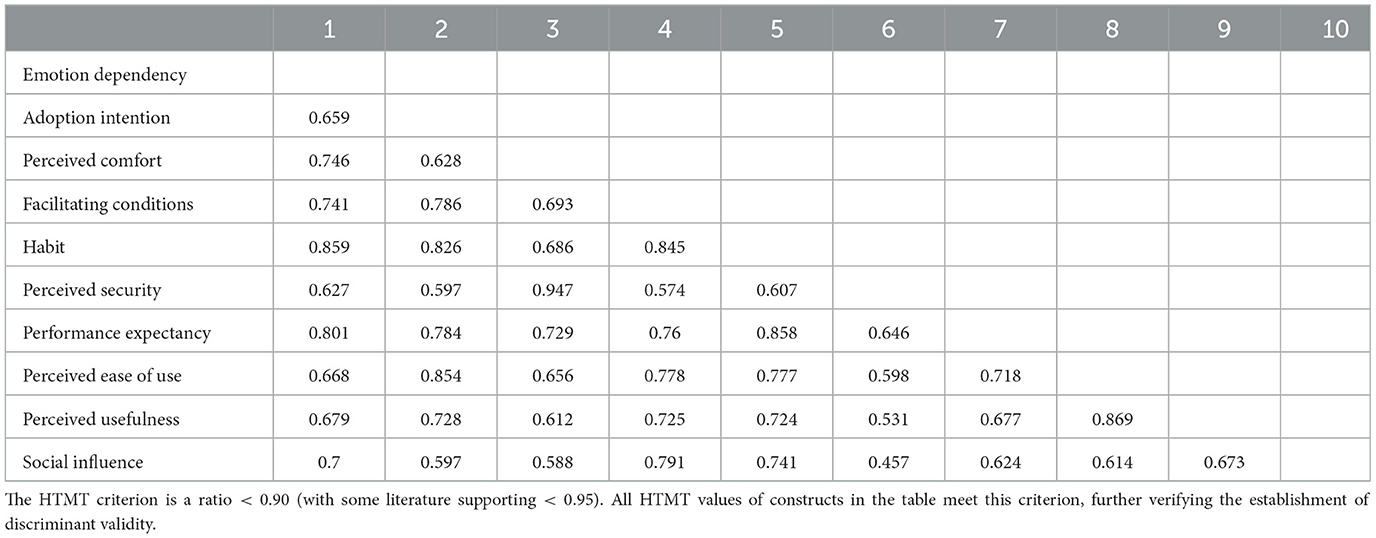

Validity test includes convergent validity and discriminant validity: the former is evaluated by factor loadings and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), while the latter is verified by the Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait- Monotrait Ratio (HTMT), with specific results as follows. In terms of convergent validity, the AVE values of all constructs range from 0.632 to 0.843 (Table 5), far exceeding the threshold of 0.5; moreover, during the pre-survey, the factor loadings of all items are >0.7, indicating that the observed indicators can effectively reflect the core connotation of latent variables and that the convergent validity meets the standard. In terms of discriminant validity, the results of the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Table 5) show that the square root of AVE of all constructs is greater than the inter-construct correlation coefficients of the corresponding rows/columns—for example, the square root of AVE of adoption intention is 0.918, and its correlation coefficient with emotional dependence is 0.614, while that with perceived ease of use is 0.806, both of which are < 0.918, confirming clear boundaries between constructs.

The results of the HTMT test (Table 6) show that the HTMT values of all constructs are < 0.95, among which the construct pair closest to the threshold is “perceived insecurity and perceived discomfort” with an HTMT of 0.947. Although this value is relatively high, the discriminant validity is still sufficient, based on three core reasons: in terms of differences in theoretical dimensions, perceived insecurity focuses on “data privacy and content reliability,” while perceived discomfort focuses on “interaction experience and psychological tension”—they belong to the dimensions of “ perceived risk” and “emotional dependency” respectively, with essentially different concepts; in terms of the logic of item design, items were distinguished through “scenario anchoring” during the pre-survey, and respondents had no confusion in understanding; in terms of evidence from other indicators, the Fornell-Larcker test for both constructs meets the standard, and the cross-loading test of PLS-SEM shows that each item has the highest loading only on its own construct (the minimum cross-loading difference is 0.12). In summary, the convergent validity and discriminant validity of all constructs meet the requirements, and the measurement model is valid.

5.2 Structural model test

After verifying the reliability and validity of the measurement model, this study used Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to conduct an empirical analysis of the hypothetical relationships between latent variables in the theoretical framework. The core objectives of structural model evaluation include hypothesis testing, relationship analysis, and model performance evaluation: hypothesis testing verifies theoretical hypotheses through the statistical significance of path coefficients; relationship analysis reveals the internal mechanism of action by quantifying the direct effects between latent variables; model performance is evaluated through R2 values and predictive relevance indicators (e.g., Q2), which together measure the explanatory power and predictive power of the model. Compared with traditional Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), PLS-SEM adopts a variance-based iterative algorithm and has flexibility in handling complex models, non-normal data, small samples, and multi-collinearity issues, making it particularly suitable for prediction-oriented analysis (Hair et al. (2017)).

5.2.1 Multicollinearity test

Multi-collinearity may lead to biases in path coefficient estimation and increased standard errors. This study diagnosed multi-collinearity using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), with results shown in Table 7. The VIF values of all latent variables range from 1.649 to 3.948, far below the critical threshold of 5.0 (Craney and Surles, 2002). This indicates no severe multi-collinearity in the model, and its impact on result robustness is reflected in two aspects: firstly, the parameter estimates are reliable, with no “overestimation” or “underestimation” of path coefficients caused by multi-collinearity; secondly, the model's explanatory power is unbiased—the R2 values of endogenous variables are not falsely inflated by multi-collinearity, which is consistent with theoretical expectations. For multi-collinearity control of higher-order constructs, this study implemented three strategies: first, splitting paths through the theoretical framework by defining all three variables as “antecedents of perceived usefulness/perceived ease of use” rather than treating them as antecedents of each other, thereby reducing direct correlations between constructs; second, verification through pre-survey—exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in the pre-survey showed that the factor variance explanation rates of the three variables were 68.2, 72.5, and 81.8% respectively, with no factor overlap; third, leveraging the methodological characteristics of PLS-SEM—this method adopts a “variance-based iterative algorithm,” which can reduce information overlap between constructs through weight optimization and has higher tolerance for moderate multi-collinearity than traditional SEM (Hair et al. (2021)).

5.2.2 Model explanatory power (R2) and predictive validity (Q2)

Table 7 presents the R2 values of endogenous variables, among which perceived usefulness (R2 = 0.417), perceived ease of use (R2 = 0.448), and adoption intention (R2 = 0.743) are all higher than the 0.4 threshold recommended in the social sciences (Chiu, 2025). Blindfolding analysis further shows that the Q2 values of all endogenous variables are positive (perceived usefulness: 0.307; perceived ease of use: 0.333; adoption intention: 0.621), indicating that the model has good predictive validity (Lin et al., 2020). According to Cohen's criteria (Cohen, 2016), the effect size (f2) is classified as follows: the impacts of emotional dependency on perceived ease of use/perceived usefulness, and the impact of perceived ease of use on adoption intention all fall into the category of medium effects (0.15 < f2 < 0.35); the impacts of facilitating conditions on adoption intention, habit on adoption intention, and perceived security on adoption intention all belong to small effects (f2 < 0.15); the impacts of comfort on perceived usefulness, perceived security on perceived usefulness, and perceived usefulness on adoption intention all are trivial effects (f2 < 0.15). These results indicate that the model has strong explanatory power and predictive ability under the paradigm of social science research.

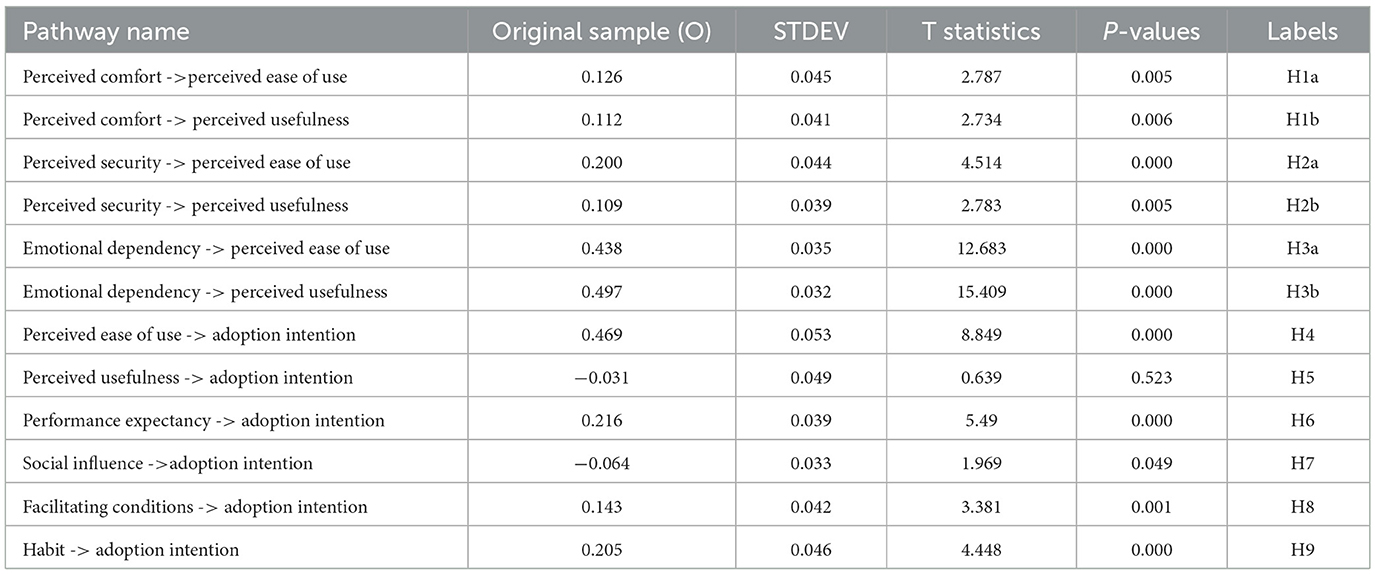

5.2.3 Path analysis and hypothesis testing

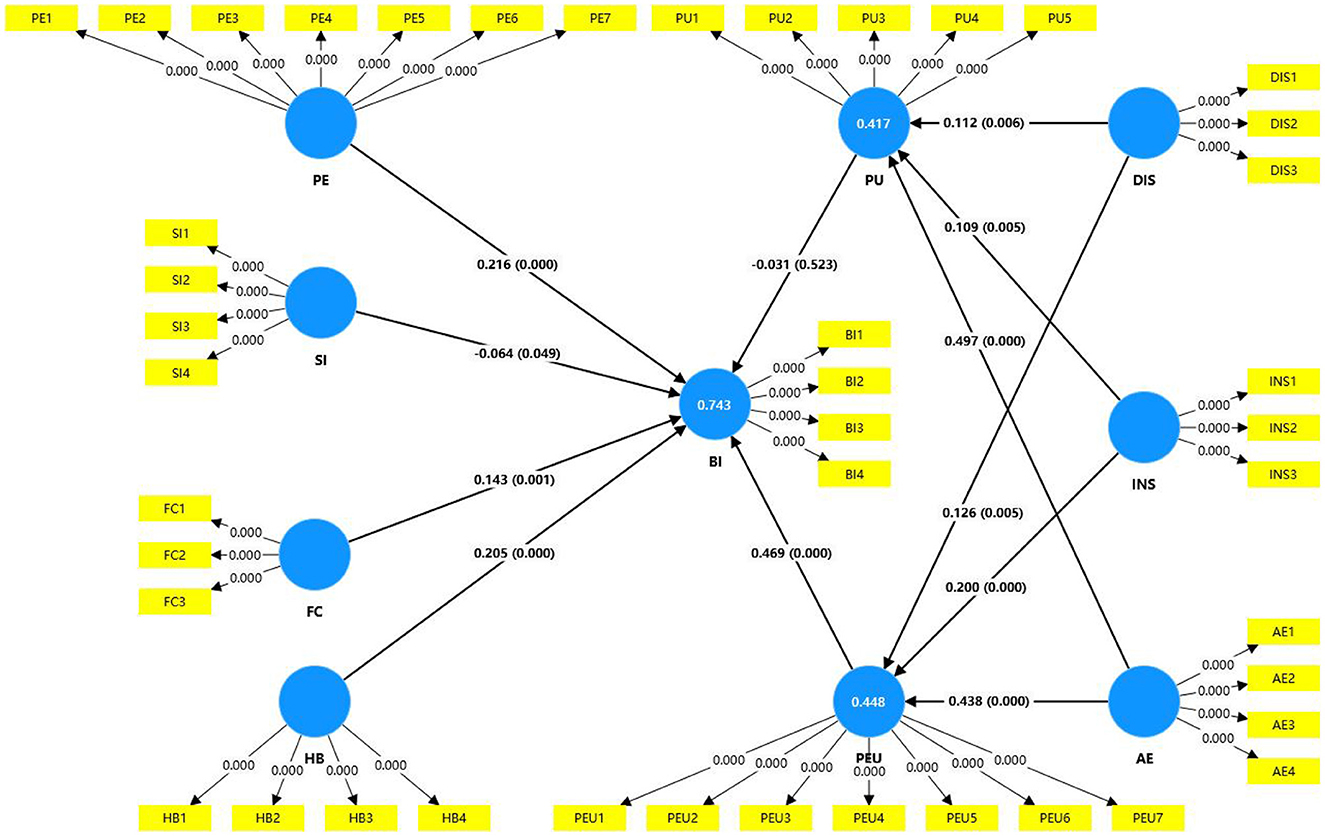

Based on the extended TAM-UTAUT2 theoretical framework, this study proposed 12 hypotheses. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to estimate path coefficients, and the Bootstrap resampling method (5,000 iterations) was applied to verify statistical significance (Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2019). The main research results are as follows (see Table 8 and Figure 2): perceived comfort exerts a positive impact on both perceived ease of use (β = 0.126, p < 0.005) and perceived usefulness (β = 0.112, p < 0.01), thus Hypotheses H1a and H1b are supported. Perceived security has a significant impact on both perceived ease of use (β = 0.200, p < 0.001) and perceived usefulness (β = 0.109, p < 0.05), so Hypotheses H2a and H2b are verified. Emotional dependency shows a strong positive impact on both perceived ease of use (β = 0.438, p < 0.001) and perceived usefulness (β = 0.497, p < 0.001), hence Hypotheses H3a and H3b are supported. Perceived ease of use (β = 0.469, p < 0.001), performance expectancy (β = 0.216, p < 0.001), social influence (β = −0.064, p < 0.05) and facilitating conditions (β = 0.143, p < 0.001) have a positive impact on adoption intention, leading to the verification of Hypotheses H4, H6, H7 and H8 are verified. The predictive effect of perceived usefulness on adoption intention is not significant (β = −0.031, p = 0.523), thus Hypothesis H5 is not supported.

Figure 2. Path analysis. AE, emotion dependency; BI, adoption intention; DIS, discomfort; FC, facilitating conditions; HB, habit; INS, insecurity; PE, performance expectancy; PEU, perceived ease of use; PU, perceived usefulness; SI, social influence.

Perceived ease of use has the stronger direct predictive effect on adoption intention (β = 0.469, p < 0.005), confirming Hypothesis H4; the direct effect of perceived usefulness is not significant (β = −0.031, p = 0.523), so Hypothesis H5 is not supported. This pattern is consistent with the core characteristics of GAI—“natural conversational interaction” and “emotional experience”—and can be explained through three mechanisms combined with literature: Firstly, the “de-instrumentalization” cognitive shift. The “perceived usefulness priority” in traditional TAM originates from the functional orientation of tool-based systems (Davis, 1989), while GAI constructs a “quasi-social partner” relationship through anthropomorphic dialogue, shifting users' decision-making to experience-based judgment of “whether it is easy to use”, which confirms the “de-instrumentalization” theory of intelligent systems proposed by Abikari (2024); Secondly, the priority of fluency experience. Although GAI lowers operational thresholds, implicit operational costs still exist, and fluency brought by perceived ease of use is the core to overcome such barriers; Thirdly, the alleviation of technological anxiety. The “black-box characteristic” of GAI triggers anxiety (Ziqi et al., 2024), and perceived ease of use reduces operational complexity to alleviate such anxiety. In contrast, perceived usefulness requires long-term utility verification, resulting in weakened short-term effects, which aligns with the finding of Casteleiro-Pitrez that technological anxiety weakens perceived usefulness (Casteleiro-Pitrez, 2024).

5.3 Moderating effect analysis

To ensure the equivalence of the measurement model across different subgroups in the moderating effect analysis, this study used the Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to test subgroups corresponding to four moderating variables (Low et al., 2025): gender (male/female), family structure (only-child/multi-child), university type (science and engineering/humanities and social sciences), and regional difference (eastern/western China).

The first step is to assess configural invariance, confirming that all subgroups use the same measurement items and latent variable structure; the second step is to assess metric invariance, verifying that there are no significant differences in item factor loadings across subgroups; the third step is to assess scalar invariance, verifying that there are no significant differences in item intercepts across subgroups. The test results (see Table 9) show that configural invariance holds for all subgroups (consistent factor structure); in metric invariance, there are no significant differences in item factor loadings across subgroups (p > 0.05); in scalar invariance, there are also no significant differences in item intercepts across subgroups (p > 0.05), meeting the MICOM full invariance criteria. This indicates that the measurement tool has consistent meaning and measurement standards across different subgroups, providing a prerequisite guarantee for the validity of subsequent subgroup comparisons and interaction effect analysis.

The moderating effect analysis focuses on the impact of four types of variables on the core paths. As shown in Table 10, all moderating effects passed the significance test at p < 0.05 and are highly consistent with the corresponding theories.

The results of the moderating effect analysis show that gender has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = −0.207, p < 0.05), that is, compared with males, the positive driving effect of performance expectancy on females' adoption intention is weaker (Strzelecki and ElArabawy, 2024). This mechanism can be explained by the dual logics of “risk ethics priority” and “social approval dependence,” and is significantly influenced by institutional policies. Females are more sensitive to the “non-transparency risks” and “academic ethics risks” of GAI (Vázquez-Madrigal et al., 2024); when performance expectancy conflicts with concerns about risk ethics, females prioritize risk avoidance over utility pursuit, thereby weakening the role of performance expectancy. This is consistent with the research conclusion of Gefen and Straub on females' technology acceptance behavior (Gefen and Straub, 1997), who found that females' perceived threshold for technology risks is significantly lower than that of males (β = 0.38 vs. β = 0.21). At the same time, females are more inclined to regard technology use as a “behavior to obtain social identity” rather than a purely “efficiency tool choice” (Yapp et al., 2018); if performance expectancy fails to match social approval, its driving effect on adoption intention will be significantly weakened. When universities issue clear usage norms for GAI, females' concerns about risk ethics will be significantly alleviated, and the criteria for judging social approval will also be clearer; in this case, the driving effect of performance expectancy will be enhanced.

Family structure has a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between habit and adoption intention (β = −0.228, p < 0.005), meaning that the positive impact of habit on adoption intention in multi-child families is significantly weaker than that in only-child families. The core logic lies in the dual constraints of “resource dilution” and “limited decision-making autonomy,” with a synergistic effect between the two. According to the resource dilution theory (Marjoribanks, 1991), family digital resources are limited, and in multi-child families, resources need to be distributed among siblings, which breaks the “continuity” of individuals' use of GAI. For example, only children can use GAI continuously for an average of 1.5 h per day, while children from multi-child families only use it for an average of 0.6 h per day with frequent interruptions. This “fragmented use” makes it difficult to form stable habits, thereby weakening the driving effect of habit on adoption intention (Tian et al., 2025). Parents in multi-child families exercise stricter supervision over technology use, leaving individuals with little autonomy to decide the frequency and purpose of use; by contrast, only children have greater autonomy in technology use decisions and can flexibly form habits based on learning needs. This difference in autonomy makes the “habit-intention” connection stronger for only children. The superposition of “inability to use” caused by resource dilution and “restriction from using” caused by limited decision-making further weakens the positive impact of habit on adoption intention in multi-child families. This is consistent with the research conclusion of Sánchez-Torres on family digital ecology, who confirmed that the dual lack of resources and autonomy reduces the behavioral driving effect of habit by 40% (Sánchez-Torres, 2019).

University type has a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = 0.251, p < 0.05), indicating that students majoring in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) are significantly more driven by performance expectancy than those majoring in humanities and social sciences. This difference is deeply rooted in the core divergence between “priority of instrumental rationality” and “priority of originality” in disciplinary cultures. Core tasks in STEM fields have extremely high demands for “efficiency improvement” and “result accuracy”, and GAI can directly meet these demands (Truong and Pham, 2025). This high alignment between “tool and demand” makes performance expectancy a strong driver of adoption intention. A study by Lavidas et al. shows that STEM students' perceived score of GAI's “tool utility” (mean = 5.8/7) is significantly higher than that of students in humanities and social sciences (mean = 4.2/7) (Lavidas et al., 2024). Core tasks in humanities and social sciences emphasize “originality of ideas” and “uniqueness of logic,” and the “homogeneous output” of GAI may threaten this core demand (Elliott and Lakin, 2021). Therefore, even if performance expectancy exists, students will carefully evaluate it due to “worries about originality,” weakening the driving effect of performance expectancy. The disciplinary evaluation system further strengthens this effect: STEM evaluation focuses more on “efficiency and accuracy of outcomes,” while humanities and social sciences evaluation emphasizes “depth of thought and originality” (Acosta-Enriquez et al., 2024).

Regional differences have a significant negative moderating effect on the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = −0.251, p < 0.05), meaning that students in eastern China are significantly less driven by performance expectancy than those in western China. The core mechanism involves “saturation of digital infrastructure” and “diminishing marginal returns of performance expectancy,” with a causal relationship between the two. Universities in eastern China have more complete digital infrastructure, and students have numerous opportunities to access efficient technical tools (Sánchez-Torres, 2019). In this context, the “performance improvement” brought by GAI is not irreplaceable, and the “scarcity” of performance expectancy decreases, thereby weakening its driving effect on adoption intention. According to the marginal utility theory, when the “performance supply” of technical tools exceeds “demand,” the “perceived utility” of each additional unit of performance improvement will decrease. For example, eastern students have already achieved “efficient literature retrieval” through other tools, so their perceived “additional performance improvement” from GAI is weak; by contrast, western universities have weak digital infrastructure, making the “performance improvement” of GAI a scarce resource, which leads to a strong “perceived utility” of performance expectancy and a significant driving effect. In addition, eastern students generally have higher digital literacy and a clearer understanding of the “performance ceiling” of GAI, which further reduces the driving effect of performance expectancy; while western students have higher expectations for technology's “performance improvement”, amplifying the driving effect of performance expectancy (Shrivastava, 2025).

6 Discussion

This study expands the TAM-UTAUT2 model from the “individual-family-university-region” four-dimensional collaborative perspective, systematically exploring the formation mechanism of college students' adoption intention of GAI. The empirical results not only address existing theoretical controversies but also provide a new explanatory framework for the educational application of intelligent technology. Innovatively, this study incorporates “affective- cognitive” variables such as perceived comfort, perceived security, and emotional dependency into the traditional technology acceptance model, and finds that all three variables exert a positive impact on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, with emotional dependency having the most prominent effect. This result verifies the applicability of the “affective-cognitive interaction model,” indicating that the anthropomorphic interaction characteristics of GAI have transcended the functional boundaries of traditional technical tools, and the emotional connection between users and technology has become a core antecedent of cognitive evaluation—this is highly consistent with the conclusion of “affective experience priority” in existing studies on natural interaction systems.

Notably, the direct effect of perceived usefulness on adoption intention is not significant. This differs from the classic conclusion of TAM that “perceived usefulness dominates” for traditional tool-based systems, but aligns with the user decision-making logic in intelligent interaction scenarios. From the perspective of technical characteristics, the “tool attribute” of traditional information systems requires users to evaluate utility first before forming intention, while the “conversational interaction attribute” of GAI makes “perceived ease of use” the primary decision-making basis—users pay more attention to low operational burden and smooth experience rather than mere utility. From the perspective of user demand hierarchy, although GAI reduces explicit operational thresholds, implicit operations may still trigger anxiety; in this case, perceived ease of use becomes the core driver by meeting the “low-burden demand,” and the “utility demand” corresponding to perceived usefulness needs to be based on smooth interaction, thus its direct effect is masked. This finding suggests that the assumption of “priority of rational utility” in traditional information system theories needs to be re-examined in intelligent scenarios.

The mechanism of action of core UTAUT2 variables presents differentiated characteristics.Performance expectancy, social influence, and facilitating conditions jointly constitute the direct path driving adoption intention, with strong explanatory power. Among them, the significant effect of social influence confirms the dual mechanism of “authority demonstration-peers imitation” in higher education scenarios—teachers' attitudes and classmates' behaviors jointly shape students' adoption intention; the impact of facilitating conditions highlights the importance of infrastructure support. Especially against the background of the digital divide, technical training, network environment, and ethical norms provided by universities directly reduce usage barriers. The direct effect of habit on adoption intention is not significant, which may be because GAI, as an emerging technology, has not yet enabled most students to form stable usage habits, or it may be related to the over-representation of science and engineering students in the sample—this group's technology exploration is more driven by task demands rather than habits.

The moderating effect analysis further reveals the group heterogeneity of adoption intention. The negative moderating effect of gender on the “performance expectancy-adoption intention” path reflects that females are more inclined to view technology use as a “socially embedded behavior” and are less sensitive to utility than males; the negative moderating effect of family structure on the “habit-adoption intention” path is consistent with the “resource dilution theory”—the constraints of resource allocation and decision-making autonomy in multi-child families weaken the driving effect of habit; the positive moderating effect of university type confirms disciplinary cultural differences—science and engineering students recognize the tool value of GAI more, while humanities and social sciences students weaken the impact of performance expectancy due to concerns about academic integrity; the negative moderating effect of regional differences reflects the difference in marginal utility of digital infrastructure—eastern students have reduced utility sensitivity due to sufficient technical exposure, while western students strengthen the driving effect of performance expectancy due to resource scarcity.

In summary, the theoretical contributions of this study lie in breaking through the “individual-technology” dualistic perspective, expanding the explanatory boundary of the TAM-UTAUT2 model, and clarifying contextual dependency. At the practical level, it can provide differentiated insights for educational management departments, universities, and developers, facilitating the precise application of generative artificial intelligence in the field of education.

7 Research conclusions

By integrating the TAM-UTAUT2 models, introducing a “individual-family-institution-region” four-dimensional moderating perspective, and conducting PLS-SEM analysis on a sample of 842 college students from eastern and western China, this study systematically reveals the formation mechanism of college students' adoption intention of GAI. The core findings and contributions are as follows.

7.1 Core empirical findings

In terms of core empirical findings, regarding the driving mechanism: three types of “affective-cognitive” variables —perceived comfort, perceived security, and emotional dependency—all exert a positive impact on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use. Among them, emotional dependency has the strongest effect, with β values of 0.497 and 0.438, respectively, and indirectly influences adoption intention through these two variables. Among the core UTAUT2 variables, performance expectancy (β = 0.216), social influence (β = −0.064, marginally significant), facilitating conditions (β = 0.143), and perceived ease of use (β = 0.469) directly drive adoption intention, jointly explaining 74.3% of the variance. However, the direct effect of perceived usefulness on adoption intention is not significant (β = −0.031, p = 0.523). This result confirms the “de-instrumentalization” acceptance characteristic of GAI, meaning users pay more attention to emotional experience and interactive fluency.

Regarding the moderating effect: Gender has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = −0.207), manifested in females being less sensitive to technology utility than males; family structure has a negative moderating effect on the relationship between habit and adoption intention (β = −0.228), with the habit-driven effect being weaker for students from multi-child families than for only children; university type has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = 0.251), with science and engineering students having a stronger perception of technology utility; regional differences have a negative moderating effect on the relationship between performance expectancy and adoption intention (β = −0.251), with eastern students having reduced sensitivity to utility due to technology saturation.

7.2 Novelty and theoretical contributions

In terms of novelty and theoretical contributions: Firstly, the study breaks through the limitations of the dualistic perspective, constructing a “individual-family-institution-region” four-dimensional collaborative framework. It is to incorporate family resource allocation, university disciplinary culture, and regional digital infrastructure into the technology acceptance model, breaking the traditional “individual-technology” dualistic research paradigm and revealing the interaction mechanism between meso/macro environments and individual psychology. Secondly, it expands the model boundary. Aiming at the “quasi-social partner” attribute of GAI, it introduces variables of perceived comfort, perceived security, and emotional dependency, verifying the shaping effect of “affective- cognitive” dual driving on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use, and making up for the explanatory gap of the UTAUT2 model in anthropomorphic interaction scenarios. Finally, it clarifies the contextual boundary. Through the analysis of four types of moderating variables, it quantifies the differentiated impacts of gender, family, discipline, and region on the adoption path, providing empirical evidence for the contextual application of the TAM-UTAUT2 model and avoiding theoretical deviations caused by the “homogenization assumption.”

7.3 Practical implications

At the practical level, based on the robust moderating effect results verified by the Measurement Invariance of Composite Models (MICOM) test, the research conclusions provide important implications for educational policy-making, the construction of university technology ecosystems, and the design of generative artificial intelligence products. The MICOM test has confirmed that different subgroups (e.g., eastern/western China, science and engineering/humanities and social sciences) have a consistent understanding of the measurement tool, so the conclusions on moderating effects can reliably guide differentiated practices: