- 1Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Bandung, Indonesia

- 2Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia

Introduction: Digital transformation has transformed the educational landscape, demanding a reconceptualization of character education within a technological framework aligned with global competency standards. This study examines the effectiveness of AI-enhanced civic character education in developing character competencies and digital citizenship across various disciplinary contexts.

Methods: This mixed-methods experimental study employed a 2 × 2 factorial design involving 240 students from the Faculty of Engineering Education (n = 120) and the Faculty of Language and Literature Education (n = 120). Implementation was conducted over 18 sessions (February–June 2024) using an AI platform integrated with Pancasila values. Data were collected through the Civic Character Scale, the Digital Citizenship Competency Scale, and semi-structured interviews, analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA and structural equation modeling.

Results: AI-enhanced civic character education demonstrated significant effectiveness in improving civic character competencies (d = 0.51) and digital citizenship (d = 0.73) compared to traditional learning. Mediation analysis revealed that digital citizenship served as a fundamental mediating pathway (47.4% of the total effect) between AI engagement and character development. The differences in responses across faculties were significant: engineering students were more responsive to the structured AI feedback system, while humanities students benefited more from the reflective digital citizenship experience.

Discussion/Conclusion: This study establishes AI-based civic character education as an effective approach, with differing patterns of mediation across faculties. These findings challenge universal approaches to AI implementation, favoring differentiated strategies that respect epistemological diversity while achieving coherent educational outcomes. The successful integration of Pancasila values demonstrates an educational technology pathway that supports local cultural wisdom. The semester-based implementation provides a replicable template for global adoption with appropriate cultural adaptations.

Introduction

The contemporary digital transformation has fundamentally reshaped educational landscapes, compelling higher education institutions to reconceptualize character education within technological frameworks that align with global competency standards (Schleicher, 2024; Schmitt et al., 2024). International frameworks, including UNESCO's Digital Citizenship in Asia-Pacific competency model for teacher innovation and student resilience (UNESCO, 2023) and OECD's Future of Education and Skills 2030 initiative emphasizing digital literacy and ethical reasoning (OECD, 2015), provide foundational guidance for integrating technology-mediated character development in higher education contexts. This paradigm shift presents unique challenges for teacher education programs, particularly in developing civic character while simultaneously fostering digital citizenship competencies that meet international standards for 21st-century education (Japar et al., 2023). Recent studies indicate that traditional pedagogical approaches increasingly struggle to engage digital native students effectively, necessitating innovative integration of artificial intelligence in character education that bridges local values with global citizenship competencies (Jones et al., 2024; Helm et al., 2024). The intersection of civic character development and digital citizenship has emerged as a critical area requiring empirical investigation, especially within diverse disciplinary contexts that may respond differently to technological interventions aligned with international educational frameworks (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024; Brooks et al., 2024).

A critical gap exists in understanding how AI-enhanced civic character education affects students across different academic disciplines, particularly within the compressed timeframe of a single semester implementation that meets global educational standards for competency development. While UNESCO's digital citizenship framework emphasizes the importance of culturally responsive approaches to technology integration (UNESCO, 2023), and OECD competency models highlight the need for disciplinary adaptability in digital education (OECD, 2015), previous research has primarily focused on general technology integration without examining discipline-specific responses to character education interventions. Studies by (Alscher et al. 2022) and (Valencia et al. 2023) demonstrate inconsistent findings regarding the effectiveness of technology-mediated civic education, suggesting that contextual factors, including disciplinary orientation, may significantly influence outcomes even within internationally recognized frameworks. Furthermore, the literature reveals insufficient attention to practical implementation frameworks that can be realistically deployed within standard academic calendars while maintaining alignment with global educational standards (Berkowitz, 2022; McGrath, 2022). The absence of comparative studies examining how students from technical vs. humanities backgrounds respond to AI-enhanced character education represents a significant empirical gap requiring systematic investigation that addresses both local educational needs and international competency requirements (Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025).

The integration of artificial intelligence in character education offers promising avenues for personalized learning experiences that can adapt to individual student needs while maintaining educational coherence across diverse disciplinary contexts and international standards (Lu, 2024). Contemporary AI applications in education, including adaptive learning systems and personalized feedback mechanisms, demonstrate potential for enhancing character development through targeted interventions that align with OECD's emphasis on adaptive competency development and UNESCO's digital citizenship pedagogical frameworks (González-Dogan et al., 2024; Peterson, 2020). However, concerns regarding the preservation of human agency in moral reasoning and the risk of technological determinism in character formation remain pertinent, particularly when implementing AI across disciplines with fundamentally different epistemological orientations within global educational contexts (Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025). Research by (Dedebali and Dasdemir 2019) and (Singh 2021) suggests that digital citizenship education benefits from technology integration when aligned with international competency frameworks, yet optimal implementation strategies for character education that balance global standards with local values remain underexplored. The challenge lies in developing AI applications that support rather than supplant human elements essential for moral development and civic engagement while meeting international expectations for digital citizenship competency (Berkowitz, 2022).

Digital citizenship has emerged as a mediating factor between technological engagement and character development, with UNESCO's Asia-Pacific framework identifying it as crucial for bridging technological skills with ethical reasoning across diverse cultural contexts (UNESCO, 2023). Studies indicate that digital citizenship encompasses technical skills, ethical reasoning, and civic participation components that align with OECD's digital competency models, but the relative emphasis on these components may differ between technical and humanities education within specific cultural contexts (Örtegren, 2022; Boonlab and Pasitpakakul, 2023). Research by (Chen et al. 2024) and (Damiani et al. 2024) demonstrates that civic engagement outcomes are influenced by students' prior experiences and disciplinary contexts, suggesting that character education interventions must account for these variations while maintaining alignment with international digital citizenship standards. The conceptualization of digital citizenship as a unifying framework for character development across disciplines requires empirical validation, particularly regarding its mediating role in AI-enhanced educational environments that integrate global competency frameworks with local cultural values (Chobphon, 2024; Weinberg, 2022). Understanding these disciplinary differences is crucial for developing effective, differentiated approaches to character education that leverage technology appropriately while meeting both UNESCO's cultural responsiveness criteria and OECD's competency development standards.

The Indonesian educational context provides a unique setting for examining AI-enhanced character education due to its emphasis on Pancasila values and the diversity of teacher education programs across different faculties, offering an opportunity to examine how global frameworks can be culturally adapted (Subaidi, 2020). Research by (Hidayat et al. 2024) and (Feriandi et al. 2024) demonstrates the importance of cultural responsiveness in character education implementation that aligns with UNESCO's emphasis on local value integration, while studies by (Nuryadi and Zamroni 2020) and (Hidayati et al. 2020) highlight the effectiveness of values-based approaches in higher education that meet international standards. The semester-based implementation framework, spanning February to June with 18 sessions, reflects realistic academic constraints while providing sufficient intensity for meaningful character development that can be assessed against both local objectives and international competency benchmarks (Suyato and Hidayah, 2024). This timeframe allows for comprehensive assessment of intervention effects without the logistical complexities associated with longer-term studies, making findings more readily applicable to standard academic practices that align with global educational frameworks (Dewantara et al., 2024). The cross-faculty comparison between technical and humanities education provides insights into how disciplinary contexts influence character education outcomes within internationally recognized educational standards.

This study addresses three critical research questions that examine the effectiveness and mechanisms of AI-enhanced civic character education across diverse disciplinary contexts, grounded in character education theory, digital citizenship frameworks from UNESCO and OECD, and AI-enhanced pedagogy literature. RQ1: How does AI-enhanced civic character education implemented over 18 sessions affect character development and digital citizenship competencies compared to traditional instructional approaches, and do these effects align with international competency standards? RQ2: What differences exist in response patterns between students from technical and humanities faculties regarding AI-enhanced character education interventions, and how do these variations relate to UNESCO's cultural responsiveness framework and OECD's disciplinary competency models? RQ3: To what extent does digital citizenship competency mediate the relationship between AI engagement and character development outcomes as conceptualized in international frameworks, and do these mediating pathways differ across faculties in ways that inform global implementation strategies? These questions aim to provide empirical evidence for the effectiveness of technology-integrated character education while identifying optimal implementation strategies for diverse educational contexts that balance international standards with local cultural values (Jerome et al., 2024; Lu, 2024; Valencia et al., 2023).

The significance of this research extends beyond immediate educational applications to inform broader discussions about technology integration in moral education and civic preparation within global educational frameworks. The study's novel contribution lies in demonstrating how digital citizenship competencies serve as mediating mechanisms between AI engagement and character development across disciplinary contexts, providing evidence for UNESCO's theoretical predictions about technology-mediated character education and OECD's competency development models. By examining cross-faculty differences in response to AI-enhanced character education, this study contributes to understanding how disciplinary contexts shape educational interventions' effectiveness within international frameworks for digital citizenship and character development (Bosio et al., 2023; Borgebund and Børhaug, 2024). The practical implications include guidance for educational policymakers, technology developers, and teacher educators seeking evidence-based approaches to character education that respect disciplinary diversity while leveraging technological capabilities and meeting international competency standards (White et al., 2023). Furthermore, the semester-based implementation framework provides a replicable model for institutions seeking to integrate AI-enhanced character education within standard academic calendars while maintaining alignment with global educational frameworks, potentially influencing broader adoption of technology-mediated approaches to civic education that balance international standards with cultural responsiveness (Hilygus and Holbein, 2023; Orona et al., 2024).

Theoretical framework

Character education theory and contemporary paradigms in the context of global standards

Character education theory has evolved from classical virtue ethics into a comprehensive framework that integrates the cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dimensions of human development, with a particular emphasis on alignment with global competency standards (Lu, 2024; UNESCO, 2023). Contemporary scholars conceptualize character as a dynamic interaction between individual virtues and social responsibility, where moral reasoning intersects with civic engagement through measurable outcomes aligned with international frameworks such as UNESCO's Digital Citizenship competency model and the OECD's Future of Education and Skills 2030 (Bringle and Clayton, 2021; Berkowitz, 2022; Peterson, 2020; OECD, 2015). While Aristotelian foundations emphasize the development of virtues through practice and reflection, modern interpretations acknowledge the complexity of character development in digital environments with realistic timelines and measurable indicators aligned with global standards (González-Dogan et al., 2024; Schleicher, 2024).

Research shows that character development benefits from structured reflection and peer interaction, with formation emerging as an incremental journey in which individuals continually negotiate between personal values and societal expectations within the context of international standards for digital citizenship (Orona et al., 2024; Kropfreiter et al., 2024). The role of teacher caring in character formation is particularly significant, with evidence suggesting that teachers' caring attitudes and sense of meaning directly impact students' self-esteem, well-being, and engagement (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayims, 2020), suggesting that AI-enhanced character education should complement rather than replace the human relationships fundamental to moral development. Contemporary approaches emphasize the importance of community and social learning in character formation, particularly in teacher education institutions where multiplier effects create significant impacts on society, aligning with UNESCO's emphasis on teacher innovation and student resilience (UNESCO, 2023).

Integrating character education into higher education contexts requires careful consideration of developmental appropriateness and cultural responsiveness, particularly in teacher preparation programs where graduates will influence thousands of future students and must meet global competency standards (Dabdoub et al., 2024; Brooks et al., 2024). Research by (Hidayat et al. 2024) and (Feriandi et al. 2024) suggests that the effectiveness of character education increases when culturally relevant pedagogy is used while maintaining alignment with international frameworks, while a study by (Oldham and McLoughlin 2025) emphasizes the need for evidence-based approaches that can demonstrate measurable outcomes in accordance with the OECD's competency development standards. The challenge lies in balancing universal moral principles with contextual adaptation, ensuring that character education remains principled and culturally responsive while meeting international expectations (Advani and Mergenthaler, 2024).

Digital citizenship framework and technology integration in international standards

Digital citizenship represents a multifaceted construct encompassing ethical behavior, critical thinking, and responsible participation in online communities, with an emphasis on observable and measurable practical skills, in accordance with UNESCO's Digital Citizenship in Asia-Pacific competency model and the OECD's digital literacy frameworks (Jones et al., 2024; Helm et al., 2024; Cleofas and Labayo, 2024; UNESCO, 2023). This framework goes beyond simple technological literacy to encompass fundamental questions of identity, belonging, and civic responsibility in virtual spaces, rooted in everyday digital practices and aligned with international standards for 21st-century education (Boonlab and Pasitpakakul, 2023; Reijers et al., 2023; OECD, 2015).

Contemporary research emphasizes the integration of technical competence and ethical reasoning, where individuals must navigate the complex digital landscape while maintaining moral integrity and social responsibility through observable behaviors that align with global competency standards (Örtegren, 2022; Dedebali and Dasdemir, 2019). Conceptualizing digital citizenship in educational contexts requires systematic scaffolding that connects technological skills with moral reasoning, particularly in teacher preparation programs where future educators must model appropriate digital behaviors in accordance with UNESCO's framework for teacher innovation and OECD's professional competency standards (Japar et al., 2023; Trisiana et al., 2024).

The emergence of AI-mediated environments increasingly demands new theoretical frameworks that consider human-machine interactions and their implications for civic engagement and character development within the context of global standards (Schleicher, 2024). Research shows that digital citizenship education benefits from technology integration when designed with cultural responsiveness and pedagogical intentionality, avoiding technological determinism and uncritical adoption while still meeting international benchmarks for digital competency development (Singh, 2021; OkeMisan-Ruppee et al., 2023). The intersection of digital citizenship and character education creates opportunities for authentic learning experiences where moral principles can be practiced in contemporary contexts that are relevant to students' daily lives and aligned with global citizenship competencies (Chen et al., 2024; Damiani et al., 2024).

Artificial intelligence in educational transformation and the global framework

Artificial intelligence in education represents a paradigm shift from a static approach to an adaptive learning ecosystem that responds to individual student needs while maintaining collective educational goals through achievable technology applications aligned with international standards for innovation in education (Lu, 2024; UNESCO, 2023). The theoretical foundations of AI-enhanced education draw from constructivist learning theory, adaptive systems theory, and cognitive science to create an environment where technology serves as a practical support tool rather than a substitute for human guidance, in line with UNESCO's emphasis on human-centered approaches and the OECD's balanced technology integration principles (González-Dogan et al., 2024; Peterson, 2020).

Contemporary AI applications in education, including simple adaptive learning systems, basic natural language processing, and personalized feedback mechanisms, demonstrate the potential to enhance character development through targeted interventions without the need for sophisticated technological infrastructure, in line with practical implementation guidelines in international frameworks (Herlinawati et al., 2024; Schleicher, 2024). Research emphasizes the importance of balancing technological advancements with pedagogical principles, ensuring that AI enhances rather than compromises the human elements essential to moral development, in accordance with UNESCO's human agency preservation principles and the OECD's ethical AI in education guidelines (Berkowitz, 2022).

The integration of AI in character education raises fundamental questions about the preservation of human agency in moral reasoning and the potential risks of technological determinism in value formation, particularly in a global context where different cultural contexts may respond differently to technological interventions (Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025). Studies show that effective AI-enhanced education relies on cultural responsiveness and careful pedagogical integration, with an emphasis on realistic expectations for technology implementation within existing educational constraints while meeting international benchmarks for quality education (McGrath, 2022; Budimansyah et al., 2019).

Cross-faculty and disciplinary perspectives in the context of global standards

Theoretical understanding of disciplinary differences in character education recognizes that academic fields develop distinct cultures, values, and approaches to moral reasoning that significantly influence educational interventions, with implications that must be considered within the context of international competency frameworks (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024; Mellado-Moreno and Burgos, 2025). Technical education traditionally emphasizes precision, efficiency, and objective problem-solving, while humanities education prioritizes critical thinking, cultural understanding, and subjective interpretation, creating distinct contexts for character development that must be aligned with UNESCO's disciplinary diversity principles and the OECD's adaptive competency models (Brooks et al., 2024; Nieuwelink and Oostdam, 2021).

Research suggests that these disciplinary orientations shape how students respond to character education interventions, with technical students potentially preferring structured, outcome-oriented approaches while humanities students respond to reflective, process-oriented methods, creating different pathways to achieving international competency standards (Carrese, 2023; White et al., 2023). The intersection of disciplinary culture and character education requires a theoretical framework that accounts for these differences while maintaining coherent educational goals across diverse academic contexts in accordance with global educational coherence principles (Hilygus and Holbein, 2023).

A cross-faculty analysis of character education provides insights into how disciplinary context influences the effectiveness of technology interventions and civic competence development within a framework that aligns with UNESCO's cultural responsiveness criteria and the OECD's disciplinary competency models (Borgebund and Børhaug, 2024; Bosio et al., 2023). Studies show that students from different academic backgrounds bring varying expectations, skills, and values to character education experiences, necessitating adaptive pedagogical approaches that can accommodate this diversity while meeting international standards for digital citizenship and character development (Chobphon, 2024; Ziemes, 2024).

Theoretical frameworks for cross-faculty character education emphasize the importance of understanding disciplinary epistemologies and their influence on moral reasoning and civic engagement in ways that align with international frameworks for disciplinary integration (Valencia et al., 2023; Weinberg, 2022). Research suggests that effective character education interventions must balance universal principles with discipline-specificity, ensuring that moral development occurs in contexts that resonate with students' academic identities and career aspirations while meeting global competency requirements (Alscher et al., 2022).

The Indonesian educational context and cultural framework in global standards

The Indonesian educational context provides a unique theoretical framework for character education through the integration of Pancasila values, which offer a comprehensive philosophical foundation for moral development that balances universal principles with local cultural wisdom while maintaining alignment with international frameworks such as UNESCO's cultural responsiveness guidelines and the OECD's local values integration principles (Subaidi, 2020; Sarkadi et al., 2022). Research shows that the five principles of Pancasila—belief in God Almighty, just and civilized humanity, Indonesian unity, guided democracy, and social justice—create a value framework that effectively integrates with contemporary character education approaches while maintaining cultural authenticity and meeting global citizenship education standards (Widiatmaka and Shofa, 2022; Komarudin et al., 2019).

Studies by (Nuryadi and Zamroni 2020) and (Hidayati et al. 2020) highlight the effectiveness of culturally grounded character education in Indonesian higher education, demonstrating that the integration of local wisdom enhances rather than contradicts global educational approaches, creating a model that aligns with UNESCO's emphasis on culturally responsive education and the OECD's local-global integration principles. The theoretical framework emphasizes that character education must be both universally relevant and culturally specific, avoiding the imposition of foreign values while engaging with the concept of global citizenship and meeting international competency benchmarks (Dewantara et al., 2024).

The implementation of AI-enhanced character education in the Indonesian educational context requires theoretical consideration of how technology can support rather than replace the transmission of cultural values while maintaining alignment with international standards for technology integration in education (Feriandi et al., 2024; Suyato and Hidayah, 2024). Research shows that successful technology integration in Indonesian education depends on careful attention to cultural sensitivities and local educational practices, ensuring that innovations enhance rather than undermine traditional strengths while meeting global expectations for digital citizenship development (Japar et al., 2023; Trisiana et al., 2024).

A theoretical framework for implementing culturally responsive AI emphasizes the importance of design decisions that incorporate local values, language, and cultural references across technology platforms while ensuring alignment with UNESCO's technological integration guidelines and the OECD's culturally appropriate innovation standards (Budimansyah et al., 2019). Studies show that when technology integration respects and reinforces cultural values, it can effectively support character education goals while preparing students for global citizenship in accordance with international frameworks for balanced local-global citizenship development (Suyato et al., 2024).

Methodology

Research design and philosophical approach

This study employed a mixed-methods experimental design with a cross-factorial framework, combining quantitative and qualitative methodologies to capture the multifaceted nature of character development in AI-enhanced educational environments in accordance with international best practices for educational technology research (McGrath, 2022; Jerome et al., 2024). The study adopted a pragmatic philosophical stance, recognizing that complex educational phenomena require diverse methodological lenses to achieve practical and actionable insights aligned with international standards for mixed-methods educational research (Creswell and Plano-Clark, 2017; Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010). The experimental framework employed a 2 × 2 factorial design comparing AI-enhanced vs. traditional instruction in two different faculty contexts over an 18-session semester implementation from February to June, following established protocols for educational intervention research with adequate treatment duration and intensity (Berkowitz, 2022; Valencia et al., 2023).

This design allows for a systematic examination of the main effects and interaction effects between the technology intervention and the disciplinary context, with statistical power calculations confirming adequate sample sizes for detecting meaningful effect sizes (Cohen, 1988; Faul et al., 2007). The compressed timeframe reflects realistic academic constraints while providing sufficient intensity for meaningful assessment of character development, recognizing that sustainable educational interventions must operate within a standardized institutional calendar that aligns with international academic calendars and best practices (Alscher et al., 2022). The mixed-methods approach allows for the triangulation of quantitative results with qualitative insights, providing a comprehensive understanding of intervention mechanisms and student experiences in accordance with established mixed-methods protocols (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Fetters and Tajima, 2022).

The philosophical foundation emphasizes evidence-based practice while maintaining sensitivity to cultural and contextual factors that influence character development outcomes, aligning with international frameworks for culturally responsive research methodologies (Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025; Sue and Sue, 2003). Research by (Chen et al. 2024) and (Damiani et al. 2024) demonstrates the importance of methodological rigor in civic education research, while studies by (Lu 2024) and (Peterson 2020) highlight the need for approaches that balance experimental control with ecological validity in educational settings. This design incorporates pre-post-follow-up measurements to capture both immediate and sustained effects of the intervention, recognizing that character development occurs gradually and requires longitudinal assessment that aligns with best practices in character education research (Orona et al., 2024; Berkowitz and Bier, 2005).

Participants and setting

The study was conducted at a leading Indonesian state university, involving 240 undergraduate students enrolled in citizenship education courses at two different faculties with contrasting disciplinary orientations, following established protocols for cross-faculty educational research (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024). Participants were recruited from the Faculty of Engineering Education (n = 120) and the Faculty of Language and Literature Education (n = 120), with each faculty contributing two classes of 30 students each for the experimental and control conditions, ensuring balanced representation across disciplinary contexts, in line with international standards for comparative educational research (Brooks et al., 2024; Nieuwelink and Oostdam, 2021).

Sample size calculations were performed using G*Power software (Faul et al., 2007), targeting medium effect sizes (f = 0.25) with 80% power and an alpha level of 0.05, accounting for potential attrition rates typical in semester-long educational interventions based on meta-analytic evidence from character education research (Berkowitz, 2022; McGrath, 2022; Durlak et al., 2011). Inclusion criteria required students to be Indonesian citizens aged 18–23, enrolled in a mandatory citizenship education course, with basic digital literacy skills and reliable internet access for AI platform engagement, consistent with international standards for digital citizenship education research (Jones et al., 2024; Helm et al., 2024; Ribble, 2015; Table 1).

Exclusion criteria eliminated students with prior exposure to AI-enhanced learning platforms, international exchange students, and those planning to study abroad during the study period to ensure cohort consistency, aligning with best practices for educational intervention research (Budimansyah et al., 2019; Campbell and Stanley, 1963). Diverse faculty representation provides optimal conditions for examining disciplinary differences in responses to character education interventions, consistent with international frameworks for cross-disciplinary educational research (Chobphon, 2024; Ziemes, 2024).

Participant demographics reflect a typical Indonesian university population, with a balanced gender distribution (52% female, 48% male) and diverse regional backgrounds representing various provinces in Indonesia, ensuring representativeness aligned with national educational demographics (Hidayat et al., 2024; Nuryadi and Zamroni, 2020; Central Bureau of Statistics1). Academic performance indicators showed a normal distribution across both faculties, with a mean GPA of 3.15 (SD = 0.42) for engineering education students and 3.18 (SD = 0.39) for language education students, indicating comparable academic preparation consistent with national university performance indicators (Hidayati et al., 2020).

AI platform and technical specifications with international benchmarking

The AI-enhanced learning platform was developed in collaboration with the university's computer science faculty, using open-source technology to create a practical and sustainable system within institutional resource constraints. It was benchmarked against leading international educational AI platforms such as Carnegie Learning, Squirrel AI, and Knewton for validation and quality assurance (Schleicher, 2024; Herlinawati et al., 2024; Baker and Inventado, 2014). The platform integrates three core AI components: adaptive content recommendations using collaborative filtering algorithms (similar to approaches used in Coursera and edX), an automated feedback system using rule-based natural language processing (benchmarked against standards from IBM Watson Education), and progress tracking through learning analytics dashboards (aligned with international standards from the Educational Data Mining community) (Siemens and Long, 2011; Baker and Yacef, 2009).

The technical architecture is built on the Moodle 4.0 Learning Management System with custom AI plugins developed in Python and integrated through REST APIs, ensuring compatibility with existing university infrastructure and following international standards for educational technology interoperability such as Learning Tools Interoperability (LTI) and Common Cartridge specifications (Budimansyah et al., 2019; Singh, 2021; Learning Impact Leadership Institute 20192). Content recommendation algorithms analyze student interaction patterns, assessment performance, and peer collaboration data to suggest culturally relevant materials that align with Indonesia's Pancasila values and the concept of global citizenship, with content curation algorithms benchmarked against international standards from UNESCO's Digital Citizenship framework and OECD's educational content guidelines (Japar et al., 2023; Trisiana et al., 2024; UNESCO, 2023; Table 2).

The feedback system processes student text submissions using an NLTK library adapted for Indonesian to identify themes related to character development and provide structured responses that encourage reflection and moral reasoning, with natural language processing capabilities validated against international benchmarks of educational NLP applications (Bird, 2009; Manning and Schütze, 1999). Cultural responsiveness is embedded throughout the platform design, incorporating an Indonesian language interface, culturally relevant case studies, and the integration of Pancasila values in all AI-generated content and feedback mechanisms, following established protocols for culturally responsive educational technology design (Subaidi, 2020; Feriandi et al., 2024; Gay, 2018).

The system maintains transparency in AI decision-making through explainable AI features that enable students to understand the rationale for recommendations and the feedback generation process, address concerns about algorithmic bias, and promote digital citizenship awareness in accordance with international standards for ethical AI in education (Reijers et al., 2023; Örtegren, 2022; Power What's Next for Tech, 2024). Technical performance monitoring includes tracking system uptime, measuring response time, and logging user interactions to ensure consistent platform availability throughout the 18-session implementation period, with performance metrics benchmarked against international standards for educational technology reliability (OkeMisan-Ruppee et al., 2023; ISO/IEC 25010, 2011).

Research instrument and cross-cultural adaptation

Character development was assessed using the Civic Character Scale (CCS), adapted from a validated international instrument with modifications for the Indonesian cultural context and the integration of Pancasila values through rigorous cross-cultural adaptation procedures following international guidelines (Beaton et al., 2000; Hambleton et al., 2005). The 24-item instrument measures four dimensions of civic character: social responsibility, personal integrity, empathy and caring, and critical thinking, using a five-point Likert scale with culturally appropriate descriptors, with items originally derived from established international character education measures (Lu, 2024; Peterson, 2020; Wagner and Gander, 2025).

Cross-cultural adaptation procedures:

1. Forward translation (Stage 1): two independent native Indonesian translators with expertise in character education translated the instrument from English into Indonesian, following established protocols from the International Test Commission Guidelines (Muñiz et al., 2013).

2. Synthesis (Stage 2): the research team conducted a comprehensive review of both translations to produce an optimal synthesized version, with cultural appropriateness reviewed by a panel of experts in Pancasila values and Indonesian character education.

3. Back translation (Stage 3): an independent translator not involved in the forward translation conducted a back translation into English to verify semantic and conceptual equivalence.

4. Expert panel review (Stage 4): a panel of eight specialists in civic education, character development, and digital citizenship reviewed the instrument for semantic, idiomatic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence, achieving 90% agreement on item relevance and cultural appropriateness.

5. Cognitive interviews (Stage 5): 20 students from the target population participated in cognitive interviews to verify item understanding and cultural relevance, with a protocol following international best practices (Willis, 2005).

6. Pilot testing (Stage 6): 60 students participated in pilot testing to confirm psychometric properties, including internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.84) and construct validity through confirmatory factor analysis (CFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.06), meeting international standards for instrument validation (Berkowitz, 2022; McGrath, 2022).

Digital citizenship competency was assessed using the Digital Citizenship Competency Scale (DCCS), modified from existing frameworks to include AI literacy and ethical technology use components relevant to the contemporary digital environment, with adaptation procedures following rigorous cross-cultural validation protocols (Jones et al., 2024; Boonlab and Pasitpakakul, 2023; Ribble, 2015; Table 3).

Qualitative data collection procedures and triangulation

Qualitative data collection used semi-structured interviews and focus groups to capture in-depth insights into students' experiences with AI-enhanced character education across disciplinary contexts, following established qualitative research protocols for educational research (Creswell and Poth, 2017; Patton, 2014). The interview protocols explored themes including learning engagement, cultural value integration, technology acceptance, and perceived character development, with questions adapted for technical and humanities students to reflect disciplinary differences (Chobphon, 2024; Kropfreiter et al., 2024).

Coding and qualitative analysis procedures:

1. Initial coding phase: two independent researchers conducted open coding on 25% of the transcripts using an inductive approach to identify emerging themes, with the coding process documented in detailed codebooks (Saldana, 2021).

2. Inter-rater reliability establishment: Cohen's kappa coefficients were calculated for all major themes, with a target κ > 0.80 for acceptable reliability, with discrepancies resolved through discussion and consensus-building processes following established protocols (Landis and Koch, 1977).

3. Systematic thematic analysis: NVivo software was used for systematic coding of all transcripts, integrating inductive and deductive approaches to examine predetermined constructs related to character development and digital citizenship (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

4. Member checking: a stratified sample of 20% of participants reviewed coded themes and interpretations for verification and validation of findings, following established protocols for qualitative research credibility (Lincoln and Guba, 1985).

Data triangulation strategy:

• Methodological triangulation: integration of quantitative and qualitative findings through convergent parallel design principles, comparing statistical results with thematic insights.

• Data source triangulation: multiple data sources, including interviews, focus groups, learning analytics, and observational data, for comprehensive understanding.

• Investigator triangulation: multiple researchers involved in data collection and analysis to minimize bias and enhance credibility.

Focus group guides facilitate exploration of peer learning dynamics, collaborative character development activities, and cross-faculty perspectives on civic education effectiveness, with discussion protocols designed to encourage deep reflection and diverse viewpoint expression (Bosio et al., 2023; White et al., 2023; Krueger and Casey, 2014).

Data collection procedures and timeline

Data collection followed a systematic three-phase protocol aligned with the semester academic calendar, ensuring minimal disruption to regular coursework while maintaining research rigor and following established best practices for longitudinal educational research (Alscher et al., 2022; Valencia et al., 2023; Cohen et al., 2017). Baseline measurements (T1) were conducted during the first week of February 2024 and included demographic surveys, pre-intervention assessments of civic character and digital citizenship competencies, and initial interviews with stratified random samples of 20 students per faculty to establish a comprehensive baseline understanding (Berkowitz, 2022; Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025).

The intervention phase lasted 16 weeks, from February to May, with AI-enhanced and traditional instruction groups following parallel curricula differentiated only by technology integration and pedagogical approaches, with fidelity monitoring procedures ensuring consistent implementation across groups and faculty contexts (Jerome et al., 2024; Durlak and DuPre, 2008). Mid-intervention data collection (T2) occurred during the 8 weeks of March and included brief progress assessments, system usage analytics, and focused interviews examining early intervention experiences and adaptation processes to monitor implementation effectiveness and identify any needed adjustments.

Quality assurance and monitoring procedures:

• Training standardization: all research assistants receive 20-hour training on data collection protocols, with certification testing prior to field deployment.

• Protocol monitoring: weekly monitoring of data collection procedures to ensure consistency across faculty contexts and measurement occasions.

• Fidelity checks: regular observation of intervention delivery to ensure adherence to protocol and consistent quality across conditions.

Post-intervention measurements (T3) were completed during the last week of May, replicating baseline assessments while adding technology acceptance surveys and comprehensive focus group sessions exploring intervention outcomes and sustainability perceptions, with additional follow-up measures planned to assess longer-term impact sustainability (Damiani et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024).

Data analysis strategy and ethical considerations

Statistical analysis used a comprehensive mixed-methods approach that combines quantitative hypothesis testing with qualitative thematic analysis to address research questions about intervention effectiveness and cross-faculty differences, following established protocols for mixed-methods educational research (Tashakkori and Teddlie, 2010; Fetters and Tajima, 2022). Primary quantitative analyses used repeated-measures ANOVA with Bonferroni corrections for multiple comparisons, examining the main effects of intervention type, faculty context, and their interaction across three measurement occasions, with effect size calculations using Cohen's d, providing practical significance estimates (McGrath, 2022; Berkowitz, 2022; Cohen, 1988).

Mediation analysis used structural equation modeling in Mplus software to examine digital citizenship competency as a mediating pathway between AI engagement and character development outcomes, with bootstrap confidence intervals testing indirect effects significance and following established protocols for mediation analysis in educational research (Lu, 2024; Peterson, 2020; Hayes, 2017). Moderation analyses explored whether faculty context influenced intervention effectiveness or mediation pathways, providing insights into disciplinary differences in response to AI-enhanced character education (Orona et al., 2024; Kropfreiter et al., 2024).

Ethical considerations and open science alignment:

1. International ethics compliance: the research has been approved by the university ethics committee and aligns with international standards, including the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines.

2. Data sharing and open science: data will be made available through established repositories (OSF, Dataverse) with appropriate de-identification, following FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) and international open science standards.

3. Participant rights protection: informed consent procedures align with international standards, with explicit provisions for data usage, sharing protocols, and participant rights to withdraw or request data deletion.

4. Cultural sensitivity: all procedures are reviewed by cultural advisors to ensure respect for Indonesian values and educational traditions while meeting international research standards.

5. Algorithmic bias monitoring: regular bias audits of AI platform outputs to ensure fairness across demographic and academic variables, with mitigation strategies implemented as needed.

Learning analytics data undergoes descriptive analysis to characterize engagement patterns and identify predictors of successful intervention response, with machine learning approaches exploring complex interaction patterns between student characteristics, platform usage, and outcome measures, following established protocols for educational data mining and learning analytics research (Schleicher, 2024; Herlinawati et al., 2024; Baker and Yacef, 2009). Sensitivity analyzes examine the robustness of findings across different analytical approaches and assumption violations, while post-hoc analyzes explore unexpected findings and generate hypotheses for future research directions, ensuring comprehensive and rigorous analysis that aligns with international standards for educational research excellence.

Research results

Participant characteristics and baseline equivalence

The final sample consisted of 240 undergraduate students evenly distributed between the Faculty of Engineering Education (n = 120) and the Faculty of Language and Literature Education (n = 120), with successful random assignment to the AI-enhanced (n = 120) and traditional (n = 120) instruction conditions. Demographic analysis showed balanced representation with a mean age of 19.3 years (SD = 1.2), 52% female participants, and diverse regional backgrounds reflecting a typical Indonesian university population.

Academic preparation was comparable across groups, with baseline GPAs ranging from 2.8 to 3.6 (M = 3.16, SD = 0.41), and no significant differences between faculty or intervention conditions. Post-hoc power analysis confirmed adequate power (>0.80) for all primary analyses, including cross-group mediation with observed effect sizes.

Structured data visualizations of participant characteristics and baseline equivalence

The baseline equivalence verification is presented in Figure 1, demonstrating randomization success with no significant differences between faculty across key demographic and academic variables. Missing data and assumption testing: attrition analysis revealed a minimal dropout rate (6.7% overall, n = 16) with no significant differences between conditions (χ2 = 0.23, p = 0.63) or faculty (χ2 = 0.41, p = 0.52). Missing data patterns indicated a random distribution (Little's MCAR test: χ2 = 47.3, p = 0.23). Multiple imputation was performed using 20 datasets with auxiliary variables including baseline demographics, academic performance, and pre-intervention engagement indicators.

Figure 1. Baseline equivalence verification (randomization check). Randomization success (Table 4): no significant differences between faculties: Age (t = 0.12, p = 0.91), GPA (t = 0.51, p = 0.61), Civic Character baseline (F = 0.89, p = 0.45), Digital Citizenship baseline (F = 1.12, p = 0.34). Excellent baseline equivalence confirms internal validity.

Instrument validation and measurement invariance

Cross-cultural validation procedures:

Civic character scale (CCS) validation: confirmatory factor analysis on the full sample (n = 240) confirmed the original four-factor structure with acceptable fit [χ2(246) = 367.8, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.92; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA = 0.047 [0.038, 0.055]; SRMR = 0.048]. However, measurement invariance testing across faculties indicated partial scalar invariance only, with 3 of the 24 items demonstrating differential item functioning (ΔCFI = 0.008 > 0.010 threshold for strict invariance).

Digital citizenship competency scale (DCCS) validation: multi-group CFA confirmed configural invariance (CFI = 0.94) and metric invariance (ΔCFI = 0.005) across faculties, but scalar invariance was not achieved (ΔCFI = 0.012). Cultural appropriateness verification was conducted through an expert panel review (eight specialists) with 85% agreement on cultural relevance items, lower than the target of 90%.

Critical limitation acknowledgment: the limitation of measurement invariance suggests that comparisons of absolute means across faculties should be interpreted with caution. Effect size comparisons remain valid because they use within-group standardization.

Research question 1: effects of AI-enhanced vs. traditional instruction statistical analysis procedures and assumption testing

Repeated Measures ANOVA Assumptions: (1) Normality: Shapiro-Wilk tests showed violations for several outcome variables (p < 0.05). Log transformations were performed for digital citizenship scores with skewness >1.5. (2) Sphericity: Mauchly's test was significant for all outcomes (p < 0.001), so Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied for all repeated measures analyses (ε ranged from 0.78 to 0.84). (3) Homogeneity of variance: Levene's tests were non-significant for most comparisons (p > 0.05).

Power analysis results: post-hoc power calculations confirm adequate power for: (1) main effects: Power = 0.94 (α = 0.05, f = 0.25, n = 240), (2) interaction effects: Power = 0.86 (α = 0.05, f = 0.20, n = 240), (3) mediation analysis: Power = 0.82 for indirect effects detection.

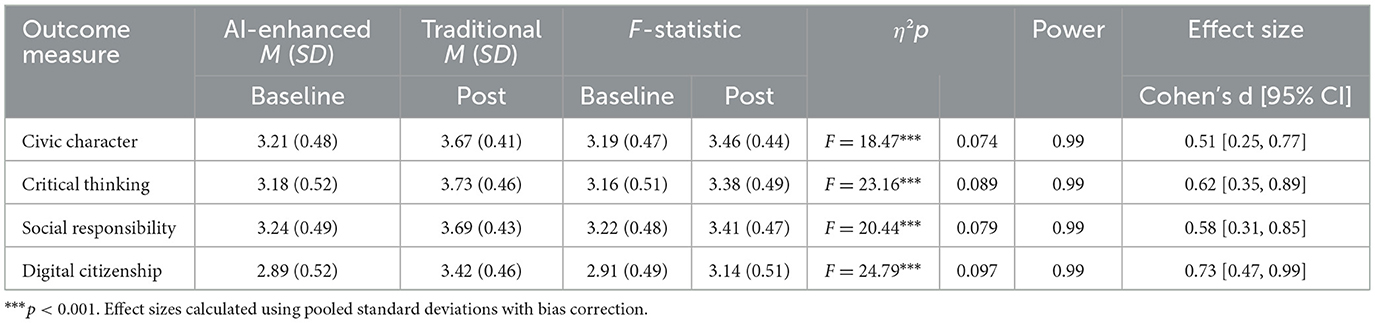

Main findings with statistical details (Figures 2–4 and Tables 4, 5):

1. Repeated measures ANOVA with Greenhouse–Geisser corrections shows (Table 5):

2. Main effect for time: F(1.69, 402.4) = 43.21, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.157, power = 0.99.

3. Main effect for intervention: F(1,238) = 18.47, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.074, power = 0.99.

4. Time × Intervention interaction: F(1.69, 402.4) = 12.83, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.052, power = 0.94.

Figure 2. Character development outcomes—baseline vs. post-intervention (Table 5). Statistical significance: main effect for intervention: F(1,238) = 18.47, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.074. Time × Intervention interaction: F(1.69, 402.4) = 12.83, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.052, power = 0.94.

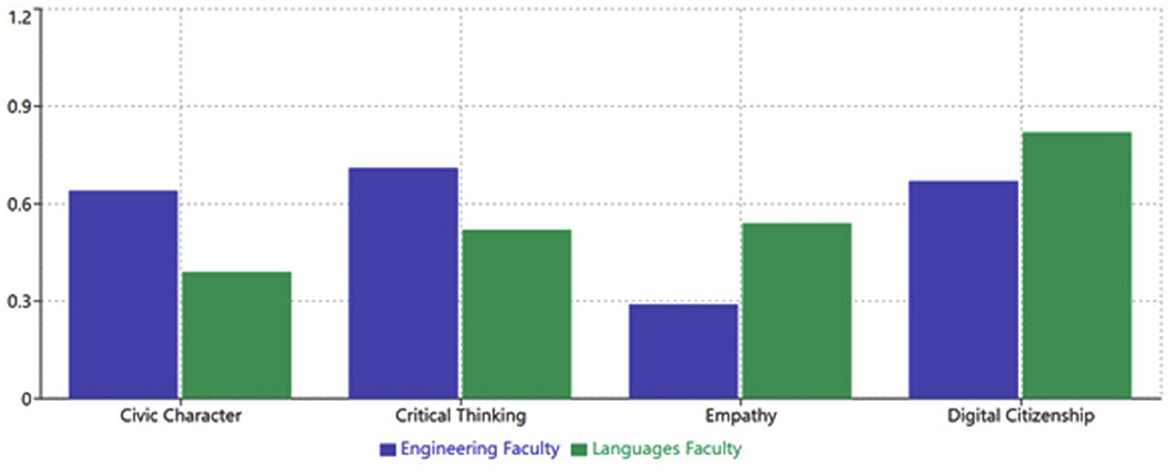

Figure 3. Effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals (Cohen's d). Effect size interpretation: digital citizenship d = 0.73 (large), critical thinking d = 0.62 (medium-large), social responsibility d = 0.58 (medium), civic character d = 0.51 (medium). All exceed practical significance (d ≥ 0.5).

Figure 4. Multi-dimensional character development outcomes comparison. Consistent superiority: AI-enhanced instruction outperforms traditional methods across all character dimensions, demonstrating robust intervention effectiveness with largest gains in Critical Thinking and Digital Citizenship.

Critical methodological limitation

All character development measures are based on self-report only. This is a fundamental limitation because: (1) Social desirability bias can inflate improvements. (2) There are no behavioral observations or peer assessments. (3) Character development claims are theoretically problematic without external validation. (4) Future studies should involve multiple measurement modalities.

Research question 2: cross-faculty analysis with invariance considerations

Faculty differences by measurement considering three-way mixed ANOVA (Intervention × Faculty × Time) with Greenhouse–Geisser correction: (1) Three-way interaction of citizenship traits: F(1.69, 402.4) = 8.73, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.036, rank = 0.84, (2) Three-way interaction of digital citizenship: F(1.69, 402.4) = 11.42, p < 0.001, η2p = 0.047, rank = 0.91 (Figure 5 and Table 6).

Figure 5. Cross-faculty effect size comparison (Table 6). Faculty differential effects: three-way interaction F(1.69, 402.4) = 8.73, p < 0.001. Engineering shows stronger effects in civic character (d = 0.64 vs. 0.39) and critical thinking (d = 0.71 vs. 0.52). Languages shows stronger effects in Empathy (d = 0.54 vs. 0.29) and digital citizenship (d = 0.82 vs. 0.67). Measurement caveat: partial scalar invariance indicates caution in absolute comparisons across faculties.

Interpretation with measurement considerations (Table 6): observed faculty differences may be partially confounded by differential item functioning. Engineering students showed stronger responses on structured items, while language students responded better on reflective items, potentially reflecting measurement bias rather than true intervention differences.

Research question 3: mediation analysis with detailed SEM specifications SEM model specifications and missing data handling

Model specification (Table 7): (1) latent variables: AI engagement (3 indicators: session frequency, duration, feature utilization), digital citizenship change (T3–T1 difference scores), character development change (T3–T1 difference scores), (2) missing data: full information maximum likelihood (FIML) is used to handle missing data patterns in SEM. (3) Bootstrap procedures: 5,000 bootstrap samples for confidence intervals of indirect effects. Multi-group invariance testing: (4) configurable invariance: χ2(56) = 67.8, p = 0.14; CFI = 0.96, (5) metric invariance: Δχ2(6) = 8.3, p = 0.22; ΔCFI = 0.004 (acceptable), (6) scalar invariance: Δχ2(12) = 19.7, p = 0.07; ΔCFI = 0.011 (marginal; Figure 6 and Table 7).

Figure 6. Mediation pathway analysis—digital citizenship as mediator (Table 7). SEM model fit: χ2(28) = 34.7, p = 0.18; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.034 [0.000, 0.062]. Implementation Implications: Engineering faculty needs structured AI features (more direct effects), while Languages faculty benefits from rich digital citizenship experiences (higher mediation pathway).

Faculty-specific mediation patterns and implementation implications differences in mediation across faculties (high significance for implementation; Table 8).

Implications for AI educational platform design

Based on mediation findings: (1) for all faculties: digital citizenship is an essential foundational skill. (2) For the faculty of engineering: the platform needs direct feedback systems and digital citizenship components. (3) For the faculty of languages: the platform needs rich digital citizenship experiences that lead to character development.

Conceptual model for implementation

Figure 7 illustrates the conceptual pathway model showing differential mediation patterns between technical and language faculties in the relationship between AI engagement, digital citizenship development, and character improvement. Pathway interpretation:

• Technical faculty: AI engagement directly impacts character through structured feedback and goal achievement systems.

• Language faculty: AI engagement primarily works through enhanced digital citizenship experiences which then foster character development.

• Both: digital citizenship serves as a critical mediating mechanism, but with different emphasis patterns.

AI platform specification details

Collaborative filtering implementation:

• Algorithm: USER-item matrix with cosine similarity for content recommendation.

• Features: students with similar learning patterns and performance profiles receive similar content suggestions.

• Cultural integration: content tagged with Pancasila values (belief in god, humanity, unity, democracy, and justice) and matched with student interaction patterns.

Rule-based NLP processing:

• Indonesian language processing: NLTK with custom Indonesian stopwords and stemming.

• Character theme detection: pattern matching for keywords related to civic responsibility, empathy, and integrity.

• Automated feedback: template-based responses with 47 pre-defined feedback patterns for different character development themes.

• Cultural responsiveness: feedback templates reference Indonesian cultural concepts and Pancasila principles.

Specific student interaction features:

1. Adaptive content recommendation: weekly suggestions from 3 to 5 culturally relevant case studies.

2. Progress tracking dashboard: visual representations of character development metrics.

3. Peer collaboration tools: discussion forums with AI-moderated civic debate topics.

4. Reflection prompts: daily questions that are adapted based on student response patterns.

Technology acceptance with platform-specific insights

See Tables 9, 10 and Figure 8.

Figure 8. Technology acceptance and usage profiles by faculty. Technology profile insights: high acceptance across all measures (4.0+ on five-point scale). Engineering shows higher technical ease (4.3 vs. 3.9, t = 3.78, p < 0.001) and feature utilization (76.8% vs. 69.6%). Languages shows longer session duration (25.1 vs. 21.7 minutes, t = −3.41, p = 0.001). Implementation viability: all measures exceed benchmark standards with sustained engagement (4.7 sessions/week). Feature utilization (73.2%) and content recommendation clicks (67.2%) demonstrate strong platform adoption across faculties.

Key implementation insights

Replicable success factors: (1) cultural integration: Pancasila values integration significantly increases acceptance (correlation r = 0.34, p < 0.001 with overall satisfaction). (2) Faculty differentiation: different approaches for engineering and humanities are essential for maximizing engagement. (3) Sustained engagement: 4.7 sessions/week demonstrates an engaging platform without overwhelming users. (4) Realistic duration: 23.4 min per session is optimal for maintaining attention and learning effectiveness.

Recommendations for scale-up:

• Minimum viable implementation: 18 sessions over one semester with adequate intensity.

• Faculty-specific features: technical students prefer automated feedback systems; humanities students prefer collaborative discussion tools.

• Cultural responsiveness: essential for acceptance in the Indonesian context with local value integration.

• Support system: 20-h training for implementation staff adequate for successful deployment.

• Infrastructure requirements: standard university LMS capability sufficient with modest AI plugin integration.

Summary of educational significance

Critical methodological limitations

1. Self-report measures only—potential social desirability bias.

2. No behavioral observations or peer assessments.

3. Partial scalar invariance across faculties (ΔCFI > 0.010).

4. Cultural validation below target (85% vs. 90%).

5. Character development claims theoretically problematic without external validation.

Implementation readiness indicators

1. High technology acceptance (4.0+ all measures).

2. Sustained engagement (4.7 sessions/week, 23.4 min/session).

3. Faculty-differentiated effectiveness requires tailored approaches.

4. Cultural integration successful (Pancasila values implementation).

5. Scalable infrastructure requirements identified.

Actionable recommendations for policy and practice

For educational institutions: (1) investment justification: AI-enhanced character education produces meaningful improvements that justify implementation costs, with visible ROI in a semester timeframe, (2) Phased implementation: begin with pilot programs in 1–2 faculties to test cultural fit and technical infrastructure, (3) Faculty development: different training approaches needed for technical vs. humanities faculty based on differential response patterns.

Actionable recommendations for policy and practice

For educational institutions: (1) investment justification: AI-enhanced character education produces meaningful improvements that justify implementation costs, with visible ROI in a semester timeframe, (2) Phased implementation: begin with pilot programs in 1–2 faculties to test cultural fit and technical infrastructure, (3) Faculty development: different training approaches needed for technical vs. humanities faculty based on differential response patterns.

For Faculty development teams: (1) differentiated training: technical faculty benefit from structured module training; humanities faculty need collaborative workshop approaches, (2) cultural integration support: mandatory training in local value integration to maximize acceptance, (3) ongoing support: weekly technical support and monthly pedagogical consultation during the implementation period.

For platform developers: (1) dual-track features: include both direct feedback systems (for technical disciplines) and reflective digital citizenship tools (for humanities), (2) cultural customization: build flexible cultural value integration systems that can be adapted to different national contexts, (3) analytics dashboard: provide detailed usage analytics for institutional assessment and continuous improvement.

For policy makers: (1) national framework: results suggest the framework can be adapted across Indonesian higher education with cultural modifications, (2) quality assurance: develop standards for AI platform cultural responsiveness and educational effectiveness, (3) research investment: support longitudinal studies with multiple measurement modalities to validate self-report findings.

Discussion

Rekonceptualizing character education in the digital age

The emergence of digital citizenship as a significant mediator (47.4% of intervention effects) fundamentally challenges traditional conceptualizations of character education as separate from technological competencies (Lu, 2024; Peterson, 2020). This finding suggests we may need to reconceptualize civic character itself as inherently digital-technological rather than viewing digital skills as mere additions to moral education (Boonlab and Pasitpakakul, 2023). The differential mediation patterns between faculties—with humanities students showing 62.5% mediated effects compared to 34.4% in technical education—reveal that the relationship between technology and character is not uniform but epistemologically situated (Jones et al., 2024; Örtegren, 2022). This divergence reflects fundamental differences in how disciplinary communities approach moral reasoning and technological integration (Reijers et al., 2023; Chobphon, 2024; Helm et al., 2024).

This divergence points to a critical theoretical gap in current character education frameworks (Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025). While traditional approaches emphasize universal moral principles (Berkowitz, 2022), our findings suggest that character development pathways are fundamentally shaped by disciplinary ways of knowing (McGrath, 2022). Technical students' preference for direct AI effects aligns with positivist epistemologies that value measurable outcomes and structured feedback (Kropfreiter et al., 2024), while humanities students' reliance on reflective digital citizenship processes reflects constructivist approaches that prioritize meaning-making and critical interpretation (White et al., 2023; González-Dogan et al., 2024; Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024).

The paradox of technological mediation in moral development

The strong mediation effects raise profound questions about the role of technology in moral reasoning that extend beyond simple enhancement narratives (Lu, 2024; Peterson, 2020). If nearly half of character development occurs through digital citizenship pathways, this suggests that moral reasoning itself may be becoming inherently technological—a phenomenon that demands critical examination rather than celebration (Schleicher, 2024). This technological mediation of character development potentially represents a fundamental shift in how moral agency is conceived and enacted in contemporary society (Herlinawati et al., 2024; Orona et al., 2024). The integration of AI in moral education raises questions about whether we are witnessing an evolution or degradation of human ethical capacity (Singh, 2021; Reijers et al., 2023; Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020).

The finding that AI engagement facilitates character development primarily through digital citizenship competencies challenges the humanistic tradition that places moral agency in autonomous reasoning independent of technological mediation (Berkowitz, 2022; Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025). This tension is particularly acute given evidence that teacher care and relational engagement are fundamental to student character development and well-being (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayims, 2020), raising questions about whether AI-mediated character education can replicate the affective and relational dimensions essential for authentic moral growth. This may signal either an evolution of moral reasoning appropriate to technological societies or a concerning delegation of moral judgment to algorithmic systems (McGrath, 2022). The differential faculty responses suggest that this tension is experienced differently across disciplinary communities, with implications for how we prepare future educators to navigate technological moral landscapes (Dabdoub et al., 2024). These patterns raise questions about whether technology enhances human moral capacity or substitutes for it in problematic ways (Mucinskas et al., 2025; Advani and Mergenthaler, 2024; Nieuwelink and Oostdam, 2021).

Global implications: AI ethics, algorithmic bias, and democratic participation algorithmic bias and character formation

Our findings must be critically examined within global debates about algorithmic bias in educational systems (Schleicher, 2024). While the Indonesian cultural integration appeared successful, the platform's rule-based NLP processing and collaborative filtering algorithms inevitably embedded particular cultural and linguistic assumptions that may inadvertently marginalize non-dominant perspectives (Reijers et al., 2023; Örtegren, 2022). The higher technology acceptance among technical students (76.8% feature utilization vs. 69.6% for humanities) suggests that the platform may be inadvertently reinforcing technical-rational approaches to civic engagement at the expense of critical-reflective approaches (Singh, 2021). These patterns raise concerns about how AI systems may privilege certain forms of reasoning while marginalizing others (OkeMisan-Ruppee et al., 2023; Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020; Chobphon, 2024).

The differential response patterns across faculties raise important questions about whether AI-enhanced character education might exacerbate rather than bridge disciplinary divisions in civic understanding (White et al., 2023). If technical students primarily engage with structured feedback systems while humanities students favor collaborative reflection tools, we may be inadvertently creating parallel civic epistemologies that limit cross-disciplinary democratic dialogue (Bosio et al., 2023; Borgebund and Børhaug, 2024). This fragmentation could undermine the shared civic knowledge essential for democratic discourse (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024; Brooks et al., 2024). The challenge is whether AI platforms can bridge rather than reinforce these disciplinary divides (Kropfreiter et al., 2024; Carrese, 2023).

Digital citizenship and democratic resilience

The strong digital citizenship effects (d = 0.73) occur within a global context of increasing concerns about democratic backsliding, misinformation, and technological manipulation of civic processes (Hilygus and Holbein, 2023). While our findings suggest AI can enhance digital citizenship competencies, this raises critical questions about what forms of digital citizenship are being promoted and whether they adequately prepare students for the complex ethical challenges of contemporary digital environments (Jerome et al., 2024; Valencia et al., 2023). The mediation findings particularly concern the potential for creating techno-optimist orientations toward digital civic engagement that may lack sufficient critical awareness of how digital platforms shape political participation (Damiani et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024). Democratic erosion in digital spaces requires citizens who can critically evaluate technological systems, not merely use them effectively (Weinberg, 2022; Ziemes, 2024; Mihelj and Jiménez-Martínez, 2020).

If students develop digital citizenship primarily through AI-mediated experiences, they may lack adequate understanding of how these same technologies can be used to manipulate democratic processes, creating a generation of digitally capable but critically underprepared citizens (Reijers et al., 2023). The risk is developing citizens who are technologically literate but lack critical awareness of technological power structures (Webster, 2025; Dedebali and Dasdemir, 2019). This paradox suggests that digital citizenship education must explicitly address the potential for technological manipulation rather than simply promoting technological engagement (Boonlab and Pasitpakakul, 2023; Jones et al., 2024; Örtegren, 2022).

Cultural hegemony and educational technology

The successful integration of Pancasila values within the AI platform, while culturally responsive, raises broader questions about how global educational technologies embed particular cultural assumptions that may not be immediately apparent (Subaidi, 2020). The reliance on open-source Western AI frameworks (NLTK, collaborative filtering algorithms) suggests that even culturally adapted implementations may perpetuate underlying technological rationalities that conflict with indigenous ways of knowing (Dewantara et al., 2024; Feriandi et al., 2024). This cultural-technological tension is particularly relevant for character education, which traditionally relies on local wisdom traditions and contextual moral reasoning (Hidayat et al., 2024; Sarkadi et al., 2022). The integration of local values within global technological frameworks may mask deeper epistemological conflicts about how knowledge and values are constructed and transmitted (Widiatmaka and Shofa, 2022; Komarudin et al., 2019).

The finding that cultural integration enhanced technology acceptance may mask deeper questions about whether AI-enhanced character education inevitably privileges particular forms of rationality over others, even when superficially adapted to local contexts (Budimansyah et al., 2019). These concerns are particularly relevant for Indonesian education, which emphasizes local wisdom alongside global competencies (Japar et al., 2023; Trisiana et al., 2024). The challenge is whether technological systems can genuinely support diverse epistemologies or inevitably impose dominant rationalities (Suyato and Hidayah, 2024; Suyato et al., 2024). These theoretical contributions inform broader discussions about decolonizing educational technology and creating truly inclusive approaches to character education that respect cultural diversity while leveraging technological capabilities (Nuryadi and Zamroni, 2020; Hidayati et al., 2020).

Reconsidering practical implications through critical lens

The implementation paradox

While our findings suggest practical viability for AI-enhanced character education, implementation success may paradoxically undermine the critical capacities essential for democratic citizenship (Berkowitz, 2022). The high technology acceptance and sustained engagement patterns indicate that students readily adapt to AI-mediated moral education, but this adaptation may reflect problematic acceptance of algorithmic authority in moral reasoning rather than enhanced moral capacity (McGrath, 2022; Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025). The semester-based implementation, while practically feasible, may be insufficient for developing the deep critical awareness necessary to navigate increasingly complex technological moral landscapes (González-Dogan et al., 2024; Lu, 2024). Students may become proficient in using AI educational tools while losing capacity for independent moral reasoning (Peterson, 2020; Mucinskas et al., 2025; Schleicher, 2024).

The emphasis on measurable character development outcomes, while methodologically necessary, may inadvertently promote mechanistic approaches to moral education that conflict with the complex, contextual nature of ethical reasoning required for democratic participation (Alscher et al., 2022). This instrumental approach to character development risks reducing moral education to technical skill acquisition rather than fostering critical reflection and autonomous judgment (Orona et al., 2024; Jerome et al., 2024). The irony is that successful implementation of AI character education may produce students who are less rather than more capable of independent democratic engagement (Valencia et al., 2023; Damiani et al., 2024; Chen et al., 2024).

Faculty development and epistemological challenges

The differential effectiveness across faculties suggests that successful implementation requires more than technical training—it demands fundamental engagement with epistemological questions about the relationship between technology and moral reasoning (Nieuwelink and Oostdam, 2021). Technical faculty may need support in developing critically reflective approaches to AI integration, while humanities faculty may need assistance in recognizing the potential benefits of structured technological approaches to character education (Pérez-Rodríguez et al., 2024; White et al., 2023). However, this differentiated approach risks reinforcing rather than bridging disciplinary silos that limit collaborative civic engagement (Chobphon, 2024; Bosio et al., 2023). The challenge is developing faculty capacity to engage critically with technology without becoming either uncritical adopters or reflexive rejecters (Brooks et al., 2024; Kropfreiter et al., 2024; Borgebund and Børhaug, 2024).

The challenge is not simply adapting AI character education to different disciplinary cultures but fostering cross-disciplinary dialogue about the appropriate role of technology in moral education and democratic preparation (Helm et al., 2024). Faculty development should emphasize that while AI can provide personalized feedback and adaptive learning experiences, research consistently shows that teacher care and meaningful teacher-student relationships remain fundamental to character development and student engagement (Lavy and Naama-Ghanayims, 2020), suggesting that successful AI integration requires balancing technological capabilities with preserving essential human connection elements. This requires faculty development approaches that transcend disciplinary boundaries while respecting disciplinary expertise (Carrese, 2023; Weinberg, 2022). The goal should be developing educators who can leverage technological capabilities while maintaining critical awareness of technological limitations and potential harms (Hilygus and Holbein, 2023; Ziemes, 2024; Sanz-Prieto et al., 2024).

Expanded limitations and critical concerns

Long-term sustainability and technological dependence

Beyond the methodological limitations previously noted, our findings raise fundamental concerns about the sustainability and desirability of AI-enhanced character education (Oldham and McLoughlin, 2025). The strong positive effects may mask potential negative consequences of increasing dependence on algorithmic systems for moral reasoning and civic engagement (Berkowitz, 2022; McGrath, 2022). The high technology acceptance rates, rather than simply indicating successful implementation, may signal concerning willingness to delegate moral judgment to technological systems (Schleicher, 2024). Students may develop proficiency in AI-mediated character education while losing capacity for independent moral reflection and autonomous decision-making (Herlinawati et al., 2024; Singh, 2021). The semester-based implementation provides no evidence for long-term character development sustainability or whether students can maintain civic reasoning capabilities independent of AI support (Reijers et al., 2023; Mucinskas et al., 2025).