- 1Department de Didàctica de l’Educació Física, Artística i Música, Universitat de València, València, Spain

- 2Institut Superior d’Ensenyances Artístiques de la Comunitat Valenciana, Generalitat Valenciana, València, Spain

Competency-based assessment has become a central focus in Higher Artistic Education (HAE) in Spain, yet its practical implementation in music conservatories remains underexplored. This study examines how teachers in Higher Conservatories of Music in the Valencian Community interpret and apply the evaluation principles outlined in Article 1, Chapter IV, of Decree 48/2011. An online questionnaire, specifically designed for this research, was completed by 39 teachers from various specializations. The instrument combined Likert-scale items assessing the adequacy of current systems for evaluating general competencies with multiple-choice questions on methodologies, perceived challenges, and perceptions of fairness, professional readiness, and improvement over traditional models. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, visualizations, and chi-square tests to explore relationships among key perception variables. Results indicate that while certain competencies are perceived as adequately assessed, others present significant challenges, particularly in aligning evaluation practices with professional preparation requirements. Perceptions of fairness are ambivalent, with many respondents selecting “partially” or “not sure,” and a significant proportion expressing doubts about the system’s capacity to fully prepare students for professional life. Competency-based assessment is viewed as an improvement over traditional models, but with important limitations. These findings underscore the need for targeted professional development and clearer institutional guidelines to bridge the gap between regulatory frameworks and educational practice.

1 Introduction

Higher Artistic Education (EAS) in Spain, following its incorporation into the education system through Organic Law 2/2006, of 3 May, on Education (LOE), has undergone a gradual adaptation to the European legislative frameworks of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). This transformation has entailed a reformulation of the teaching–learning model, with particular emphasis on competence-based assessment, as set out in the Spanish Qualifications Framework for Higher Education (MECES) and in various European quality standards (ANECA, ESG). Nevertheless, in the case of EAS—and particularly in the musical field—this transition has been partial and problematic (Vernia, 2019). EAS institutions have shown difficulties in effectively adapting to the competence-based paradigm, especially regarding the planning, implementation, and monitoring of assessment processes aligned with competences (Checa, 2022).

In the Valencian Community, Decree 48/2011, of 6 May, of the Consell, regulates the organization of Higher Artistic Education and, in Chapter IV, sets out the fundamental principles for assessment, stressing the need for it to be based on competence acquisition and to retain an integrative character. However, the effective implementation of these principles in everyday educational practice remains the subject of debate and critical analysis (Vernia, 2019). Despite the updated regulatory framework—which includes the recent Law 1/2024, of 7 June, which for the first time provides these studies with comprehensive regulation regarding institutions, faculty, and students—discrepancies persist between the declared objectives and the methodologies implemented.

These tensions become evident when observing the predominant pedagogical model in conservatories, historically grounded in a traditional approach centered on the figure of the master-performer as a benchmark and on teaching by imitation (Carey et al., 2021; Iglesias and Tejada, 2024). This model, which originated in the nineteenth-century Paris Conservatoire, has endured with few changes, retaining hierarchical structures, Eurocentric repertoires, and decontextualized assessment practices (Escorihuela et al., 2024). Various studies (Gaunt, 2010; Kingsbury, 1988; Nettl, 1995) have documented the limited integration between theory and practice, the lack of instructional planning, and the perpetuation of a canon that constrains educational innovation.

In a critical review of the professional musician training model, Iglesias and Tejada (2024) identify deep shortcomings in teachers’ pedagogical preparation, as well as an academic culture that inhibits students’ self-regulation, autonomy, and critical thinking. These limitations hinder the effective implementation of a competence-based approach to music teaching. Moreover, research points to a structural gap between theoretical subjects and instrumental training, which weakens curricular coherence and hampers truly integrative assessment.

Although the benefits of personalized guidance are recognized, current pedagogical practices rarely incorporate key elements of social constructivism, such as the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky, 1978), learning scaffolds (Wood et al., 1976), or models of self-regulated learning (Zimmerman, 1989). The lack of appropriation of these theoretical tools perpetuates a training system resistant to transformation and, in Harnoncourt’s (2006) words, one that trains “acrobats” rather than reflective musicians.

At the same time, assessment in education has evolved from a technical approach toward a more complex and comprehensive conception t+that includes pedagogical, social, and ethical functions (Ravela et al., 2017; Jornet-Meliá et al., 2012; Martín et al., 2006; Jorba and Sanmartí, 1993). Its formative and guiding character makes it a key tool for improving learning, especially when applied within a competence-based paradigm (Jornet et al., 2011; McArthur, 2019). This perspective requires rigorous planning, the design of performance standards and clear indicators, and a collegial, multidimensional methodological approach (Peralta-Jaen et al., 2020).

However, initial teacher education in Higher Conservatories presents serious shortcomings in this area. Analysis of the curricula regulated by Royal Decree 630/2010 reveals a scant presence of pedagogical competences in most specializations, except in Pedagogy (Iglesias and Tejada, 2024), even though a large share of faculty develop their professional careers by performing teaching functions (Vicente and Aróstegui, 2003).

Moreover, access to the teaching profession does not entail specific pedagogical certification, as occurs in other educational stages, which exacerbates the disjunction between musical training and teaching practice (Domínguez-Lloria and Pino-Juste, 2021).

In this regard, Royal Decree 631/2010, of 14 May, which regulates the basic content of Higher Artistic Education in music, establishes transversal, general, and specific competences, as well as professional profiles for each specialization. However, Vernia (2019) warns that these competences are not always clearly defined or adapted to the realities of the different specializations.

Vernia (2019) also points out that course syllabi in conservatories—which should function as tools for planning and transparency—are often drafted in an uncoordinated manner, disconnected from the degree plan and from other subjects. This situation generates duplication of content, methodological discoordination, and limited clarity for students regarding the competences they are expected to achieve. A lack of interdisciplinary work, collaborative projects, and clear assessment rubrics is also reported.

This research therefore aims to analyze how competence-based assessment is applied in music EAS in the Valencian Community, focusing on how faculty interpret Article 1 of Chapter IV of Decree 48/2011, as well as on the methodologies employed, the challenges perceived, and the resulting educational implications. To this end, key aspects have been considered, such as the extent to which faculty believe their current system enables adequate assessment of the acquisition of general competences, the main difficulties encountered, students’ perceptions of fairness, and the perceived impact on professional preparation.

In a context where the literature on competence-based assessment in EAS is still scarce (Escorihuela et al., 2025), this study helps fill a significant gap in the field of higher music education. Its aim is to move toward a more coherent, reflective, and student-centered training model that succeeds in articulating assessment, curriculum, and performance practice under the principles of the EHEA and in tune with the cultural and pedagogical demands of the twenty-first century. These demands are shaped by the impact of globalization and digitalization on knowledge and professional practice, the transition toward interdisciplinary curricula, and the emphasis on equity, diversity, and sustainability in higher education (López Jiménez, 1997). They also encompass the need to revitalize education through technology, foster digital competence among teachers and students, and promote high-quality, authentic, and constructivist learning experiences aligned with employability and the requirements of a global society (Arruti and Paños-Castro, 2025).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research design

This study adopted a quantitative, non-experimental, cross-sectional design aimed at analyzing how competency-based assessment is applied in Higher Artistic Education (HAE) in music within the Valencian Community, Spain. The focus was on teachers’ interpretation of Article 1, Chapter IV, of Decree 48/2011, as well as on the methodologies employed, perceived challenges, and educational implications. The approach combined descriptive statistical analysis with inferential methods (chi-square tests of independence) to explore relationships between key perception variables.

2.2 Participants

A total of 39 faculty members from publicly funded Higher Conservatories of Music in the Valencian Community (3 institutions) took part in the study, with specializations including piano, chamber music, composition, wind instruments, percussion, and music management and production, among others. Most participants had more than 10 years of teaching experience in the field of Higher Artistic Education. Sampling was non-probabilistic and incidental (convenience sampling), contacting faculty through institutional leadership (school directors) and department heads. Participation was voluntary and response anonymity was guaranteed. All participants were informed about the aims of the re-search, the confidential nature of the data, and their right to withdraw at any time, and they provided informed consent to participate, in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2015).

2.3 Materials

A questionnaire specifically designed for this research was used, titled Questionnaire on Competence-Based Assessment in Higher Music Conservatories. This instrument was developed by the research team after a review of the specialized literature and current regulations, in particular Decree 48/2011 of the Consell, which regulates assessment in Higher Artistic Education. The questionnaire included:

• A section on sociodemographic data and professional background.

• A block of 17 items on a Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) to assess the extent to which the current system allows for the adequate evaluation of each of the general competences established in the curriculum.

• Multiple-choice questions on assessment methodologies used, main difficulties encountered, and perceptions regarding fairness, improvement over traditional models, and preparation for professional life.

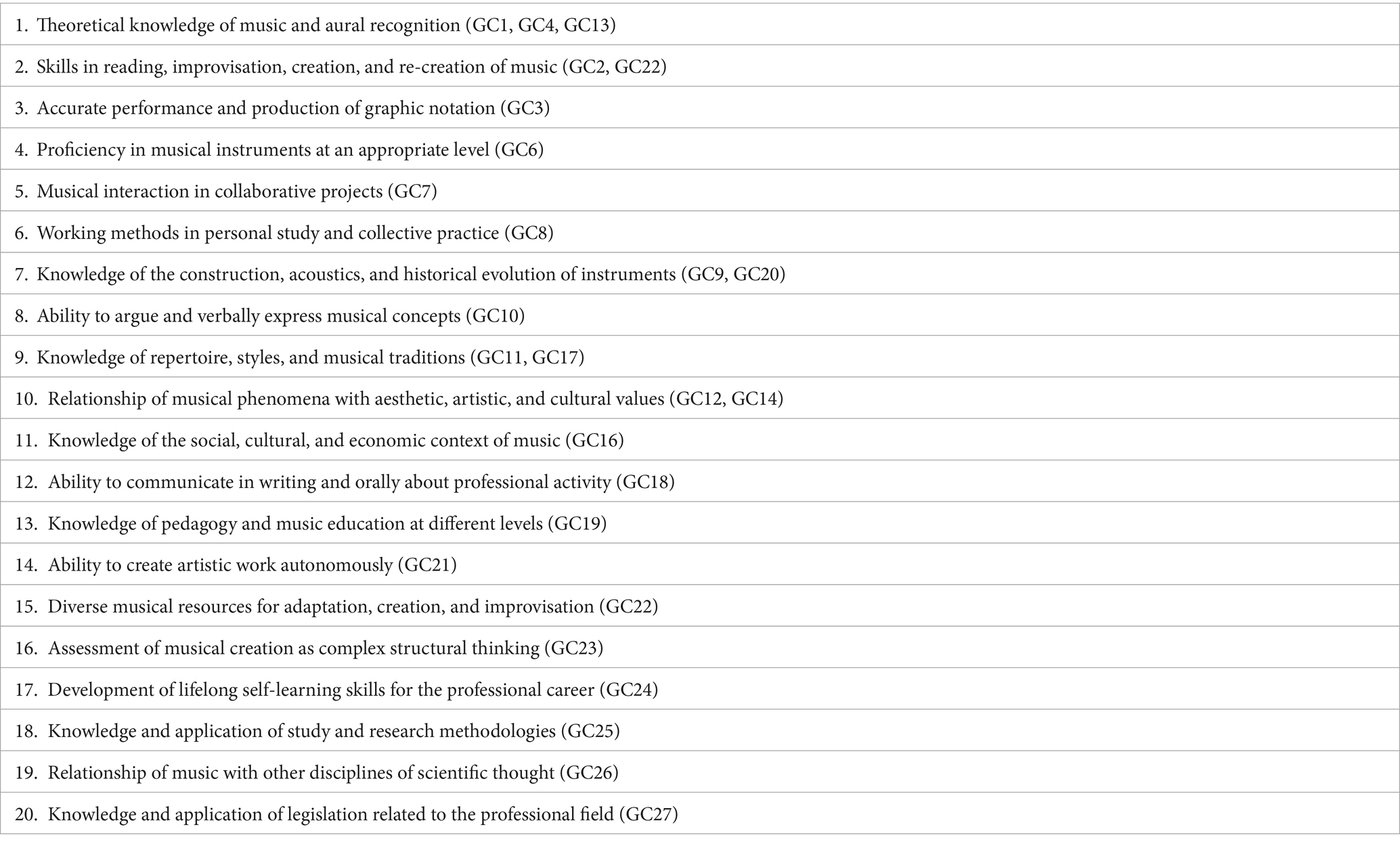

The general competences (GC) for the bachelor’s degree in Higher Artistic Education in Music number 27 and can be consulted in Royal Decree 631/2010. However, to facilitate responses to the questionnaire, these 27 competences were grouped into 20 dimensions (Table 1) that represent their content.

Table 1. Dimensions in which the general competences of the bachelor’s degree in artistic education in music have been grouped.

2.4 Procedure

Content validity was ensured through the review of the questionnaire by three university faculty members who are experts in music education and competence-based assessment. The final version was implemented in digital format to facilitate its distribution and data collection.

The questionnaire was administered online over a four-month period of the 2024–2025 academic year (January to April), using a link1 sent via institutional email and through direct contacts with conservatoire departments. The form included an introduction with the study’s objectives, instructions for completion, information on data processing, and an informed consent section. The estimated average completion time was between 8 and 10 min.

Care was taken with the order in which the questions were presented to enhance comprehension and the internal coherence of the questionnaire. The Likert-scale and multiple-choice questions were designed to be easily completed on mobile devices or computers, with a clear visual layout that minimized response fatigue.

2.5 Data analysis

The data were exported to Microsoft Excel for initial coding and subsequently analyzed with Python (pandas, matplotlib, seaborn, and scipy). The analysis included descriptive statistics (means, standard deviation, frequencies, and percentages) for the Likert-scale items, as well as frequency analysis for the multiple-choice questions. For result visualization, bar charts and heatmaps were generated.

Chi-square tests of independence were applied to explore relationships between key perceptions:

• Improvement in training vs. perception of fairness

• Improvement in training vs. professional preparation

• Fairness vs. professional preparation

The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and the corresponding effect sizes were calculated.

2.6 Ethical considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Higher Institute of Artistic Education of the Valencian Community (ISEACV). ISEACV is an autonomous body of the Valencian Regional Government that coordinates, supervises, and regulates the higher educational institutions in the arts of the Valencian Community. ISEACV does not have an established ethics committee; however, the research was approved and funded by its Research Coordination and Evaluation Commission (CCAI) [DOGV-V-2025-465]. Compliance with current data protection legislation was ensured, and the ethical principles applicable to research involving adult participants were respected.

3 Results

Thirty-nine responses were obtained from the 276 faculty members, representing a response rate of 14.1%. The number of valid responses per item ranged from 35 to 37 in the block on general competences, ensuring a sufficiently robust basis for analysis. Descriptive statistics are presented first in order to provide an overview of participants’ perceptions, followed by comparative analyses across faculty profiles where relevant. The results are structured into three main parts: (1) general competences, (2) domain-specific competences, and (3) open-ended responses, which offer complementary qualitative insights.

3.1 Faculty interpretation of decree 48/2011 (Art. 1): assessment of general competence development

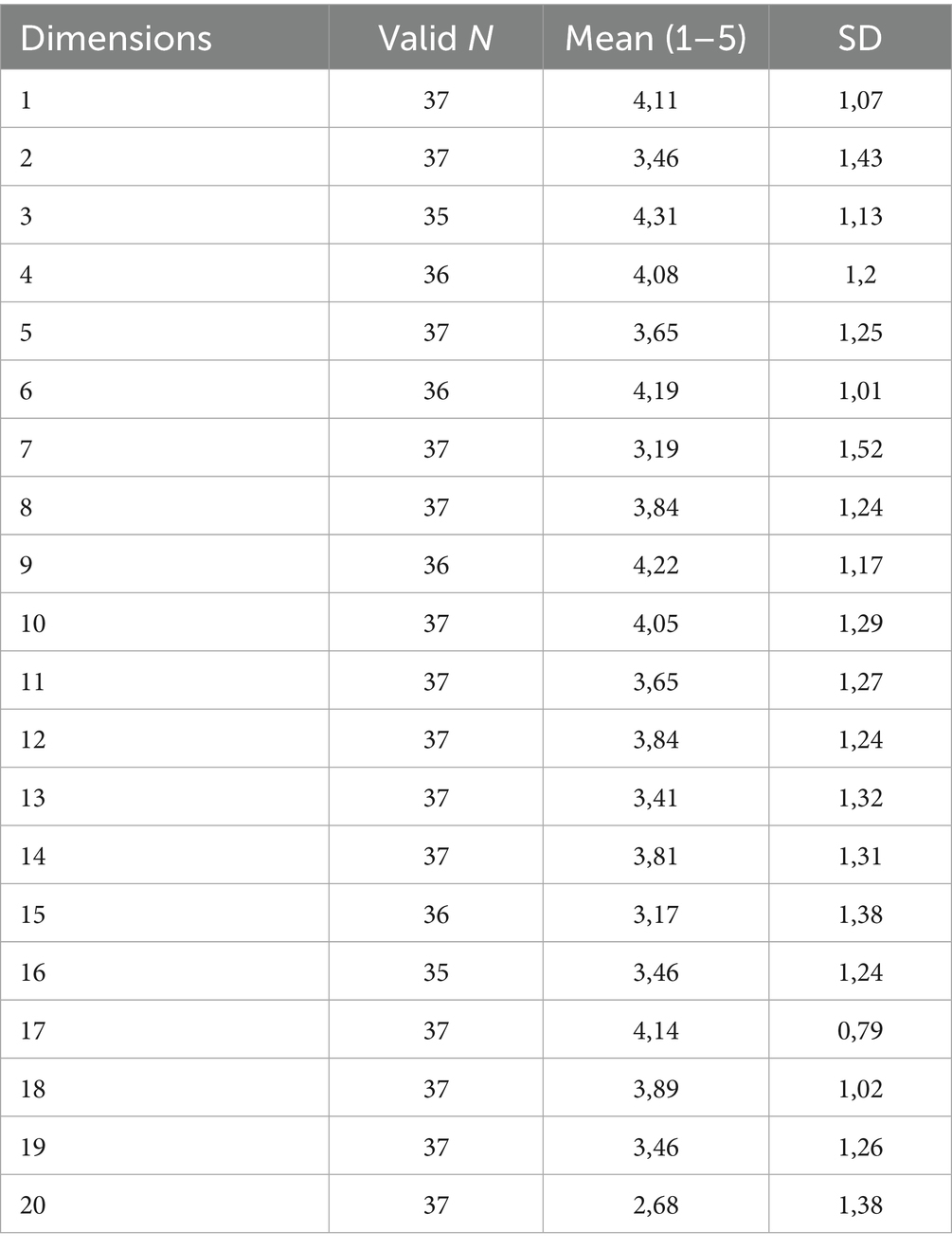

For each of the dimensions in which the general competences are operationalized, the questionnaire asked respondents to rate the extent to which the current assessment system allows their acquisition to be adequately evaluated (scale 1–5, 1 = not at all adequate, 5 = very adequate). Table 2 details the response distributions (frequencies) and the item-level descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation).

Table 2. Distribution of responses by competence dimension to the question on the perceived adequacy of the current assessment system for evaluating the acquisition of each general competence.

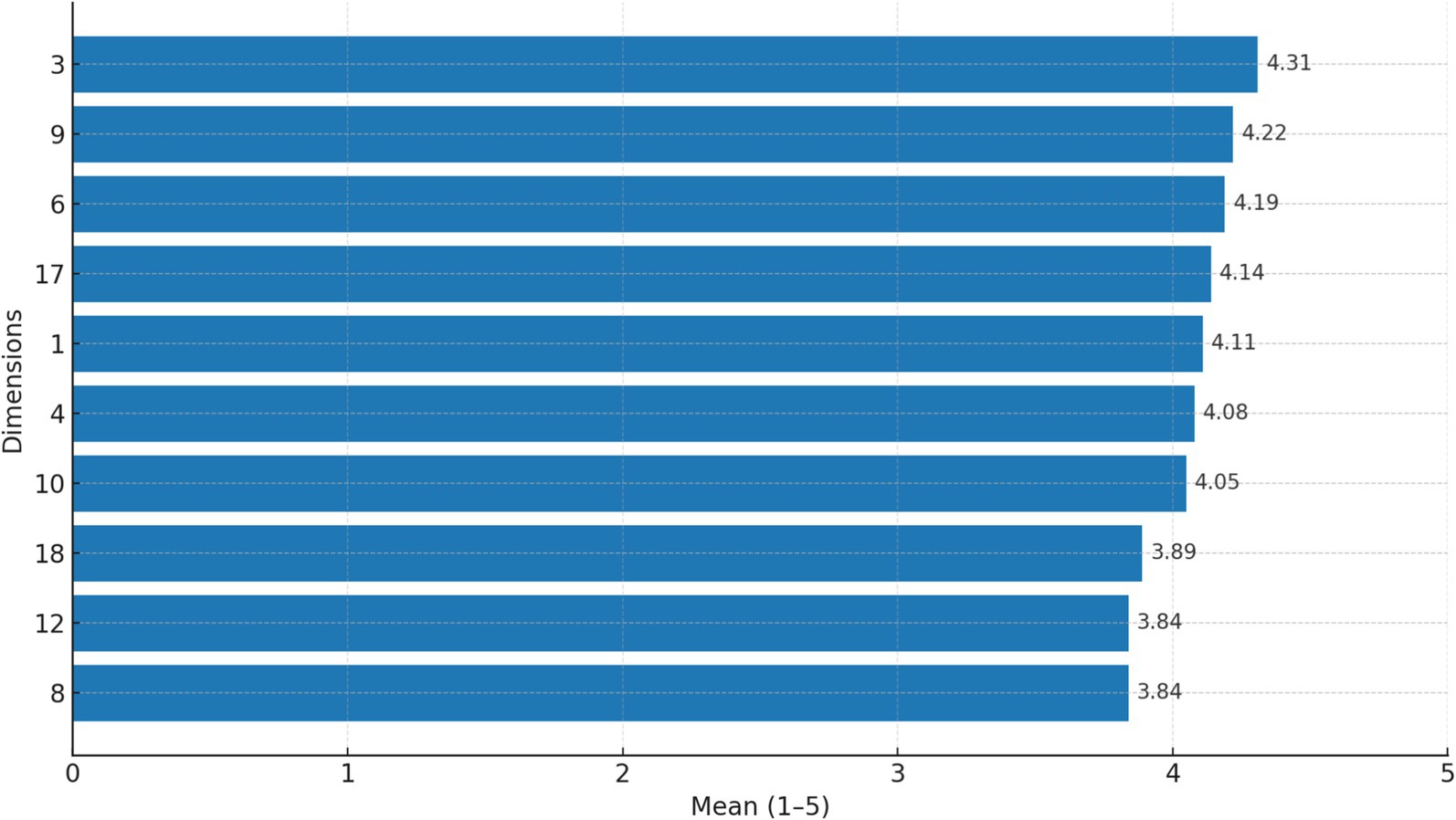

The three competences rated most highly by faculty have means between 4.19 and 4.31, indicating a high perceived adequacy of the current system for assessing them. Their SDs are around 1.00–1.17, reflecting some dispersion but a consensus toward higher scores.

The three lowest-scoring competences have means between 2.68 and 3.19, placing their ratings in the low–medium range. The higher SDs (up to 1.52) point to more heterogeneous, polarized perceptions among faculty.

This suggests that while some competences are viewed as well covered by the current assessment system, others exhibit significant shortcomings or uneven emphasis in how they are evaluated.

In sum, most adequacy means by competence fall within the 3–4 range (intermediate to high adequacy), with moderate variability. Figure 1 presents the top 10 competences with the highest adequacy means.

3.2 Assessment methodologies employed

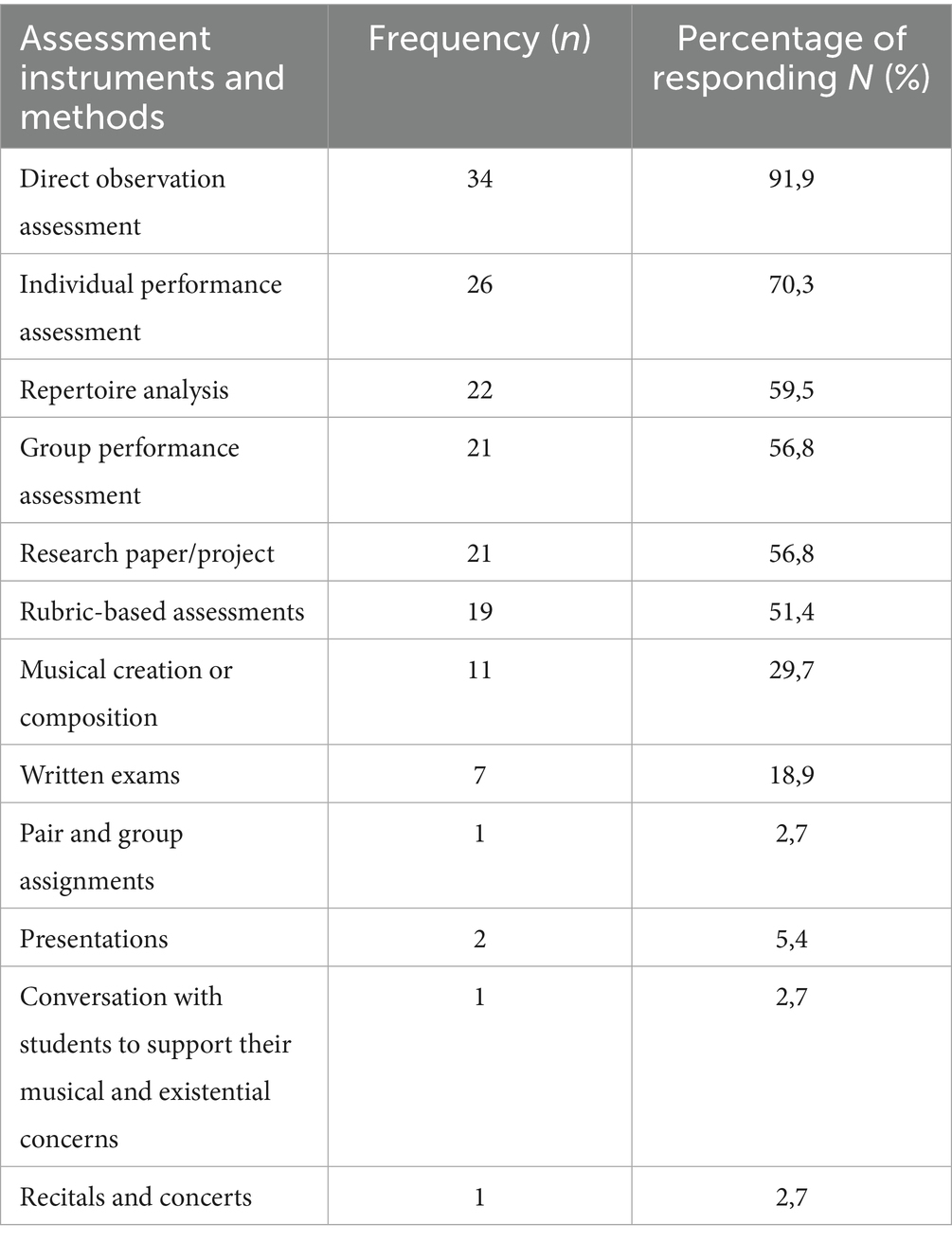

Regarding the assessment instruments and methods applied, the responses indicate a predominance of performance-based approaches and direct observation. The most frequently selected options were individual performance assessment, the use of rubrics, group performance assessment, direct observation in real performance contexts, and repertoire analysis or portfolios. This preference for performative methods and explicit criteria suggests a partial alignment with the spirit of competence-based assessment, although Table 3 shows a diversity of approaches by specialty and subject.

3.3 Perceived difficulties

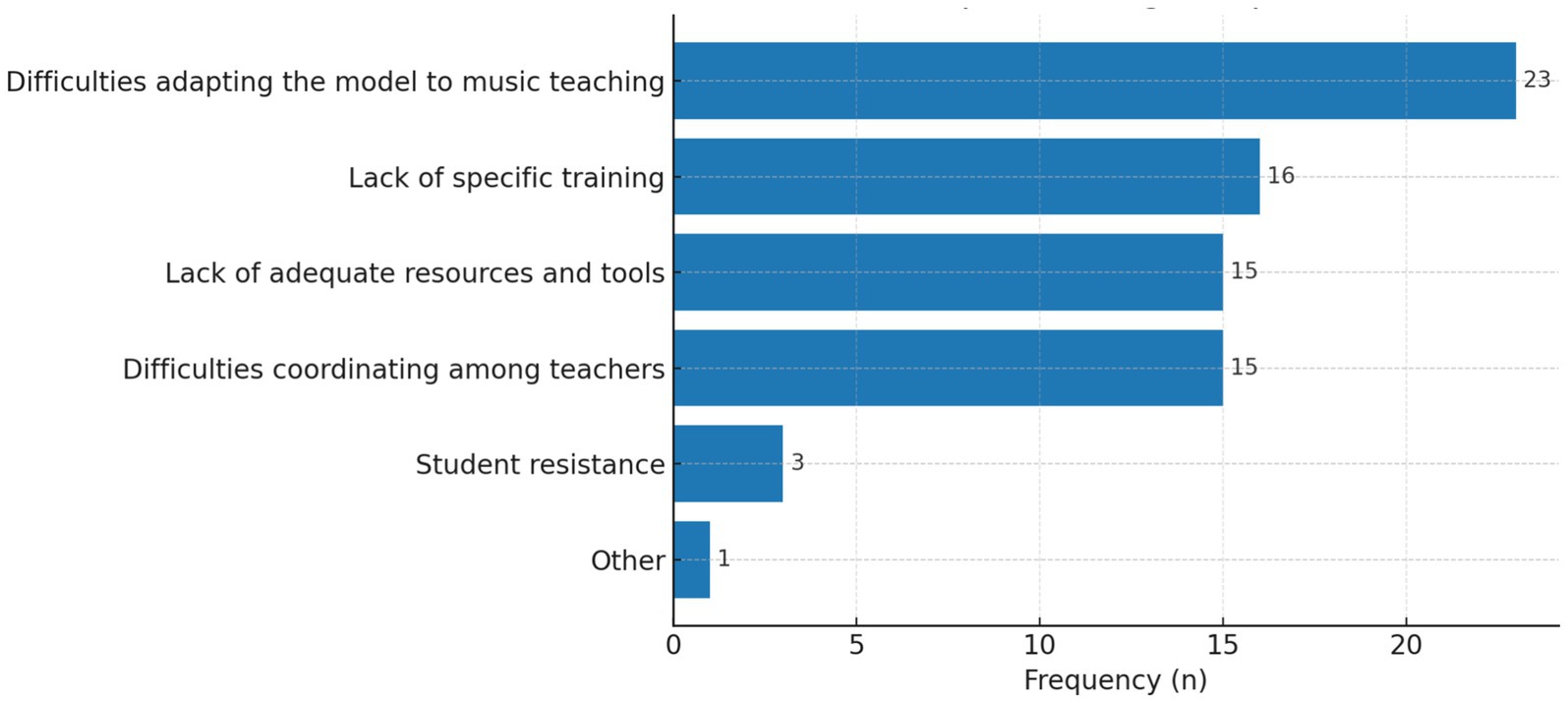

The effective implementation of competence-based assessment is constrained by a series of structural and training-related limitations (Figure 2). Among the difficulties most frequently cited by faculty are the high time burden and the need for coordination to develop authentic instruments; the lack of adequate resources (spaces, logistics, and student–teacher ratios); the heterogeneity of criteria across departments; and insufficient specific training in competence-based assessment and the use of rubrics. An excessive emphasis on numerical grading over qualitative feedback is also mentioned, which may limit the formative value of the assessment process (Figure 3).

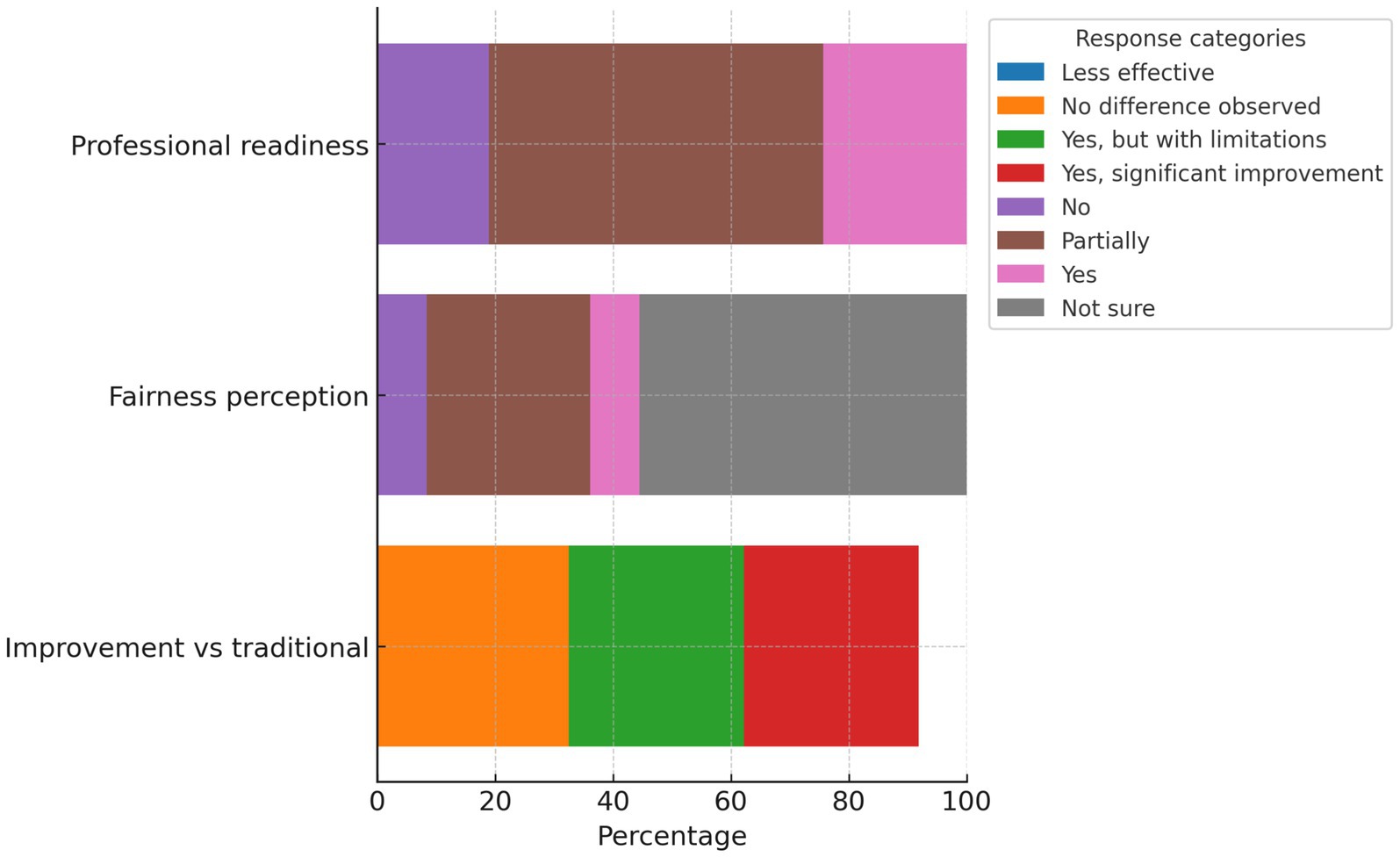

3.4 Perceptions of equity and professional preparation

Perceptions of equity in the system, from the faculty’s viewpoint, are ambivalent. In response to the question “Do you think students perceive competence-based assessment as a fair system?,” “Not sure” and “Partly” predominate, with smaller proportions of “Yes” and “No.” Regarding preparation for professional life, most instructors judge that the current system prepares students “Partly” or “No,” pointing to a gap between assessment practices and the demands of the musical labor market.

Comparison with traditional models yields a mixed picture: similar proportions believe that competence-based assessment significantly improves training and that it does so only with limitations, alongside a group that sees no major differences and a minority that considers it less effective.

The chi-square tests of independence among “improvement of training,” “perception of equity,” and “professional preparation” revealed distinct patterns. The relationship between the view that competence-based assessment improves training and perceived equity was statistically significant [χ2(9) = 16.98; p = 0.049], suggesting that opinions about formative improvement tend to vary in tandem with perceptions of fairness.

Similarly, there was a significant association between perceived improvement and judgments about professional preparation [χ2(6) = 16.75; p = 0.010], indicating that those who see greater formative value in the model also tend to regard it as more suitable for preparing students for professional life.

By contrast, the association between perceived equity and professional preparation [χ2(6) = 8.04; p = 0.235] was not statistically significant, suggesting that these judgments may rest on different criteria and are not necessarily linked in faculty opinions.

3.5 Educational implications

Taken together, the results show that although faculty employ methods aligned with competence-based assessment and view positively its capacity to measure certain general competences, significant challenges remain that affect the system’s coherence, equity, and professional relevance. The resulting recommendations include:

1. Consolidate common criteria and interdepartmental rubrics to strengthen evaluative coherence.

2. Increase resources and time for authentic assessments, fostering qualitative feedback.

3. Promote targeted faculty development in performance-based tasks, rubric design, and criterion calibration.

4. Reinforce the link between assessment and real professional contexts by integrating external stakeholders and simulations of briefs typical of musical practice.

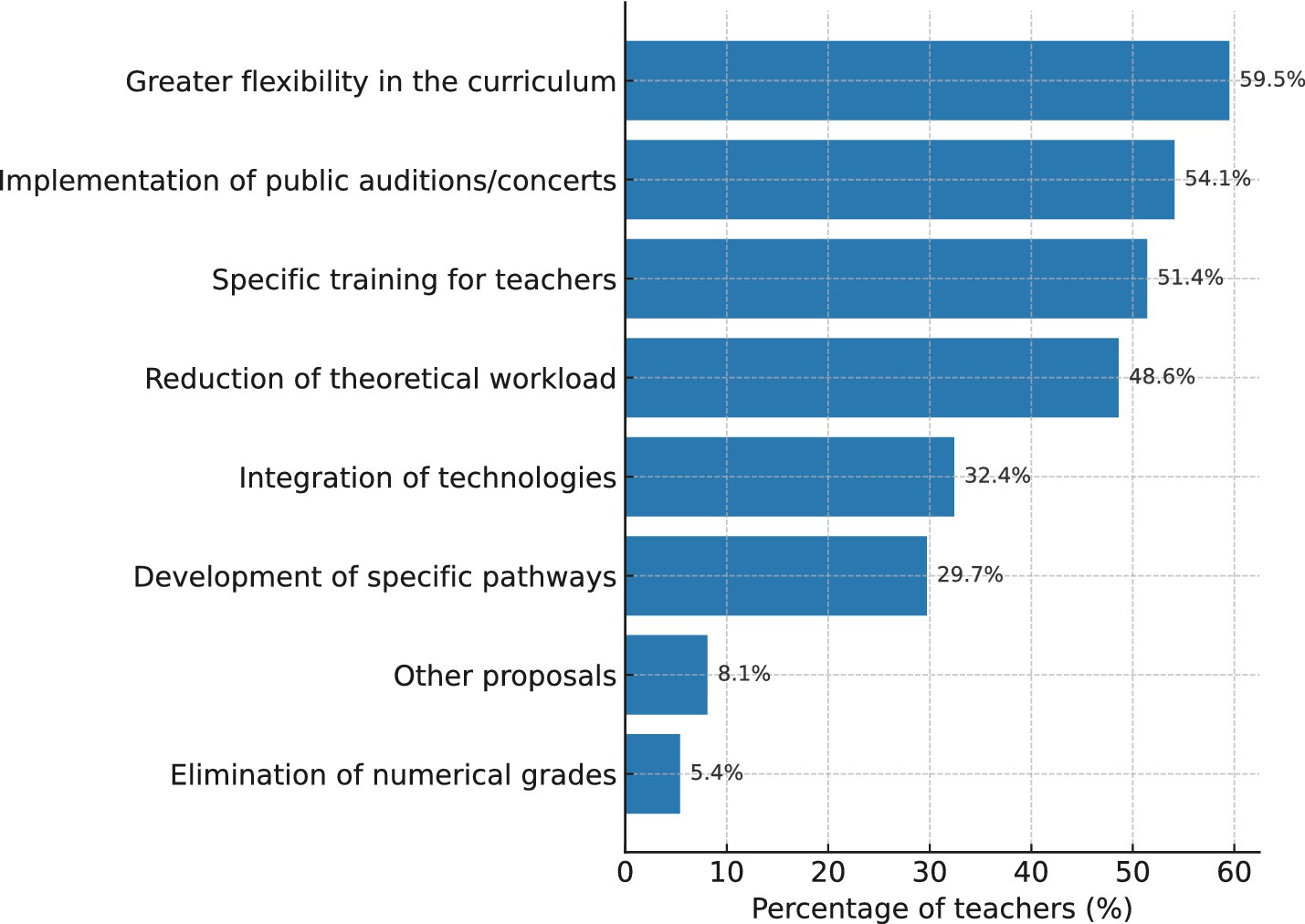

In relation to proposals for improvement (Figure 4), teachers’ responses highlight a set of priorities aimed at enhancing the coherence and relevance of the current system. Most frequently mentioned were the need for greater curricular flexibility (59.5%), the implementation of assessments based on public auditions and concerts (54.1%), and specific training for teachers in competence-based assessment (51.4%). Likewise, the reduction of theoretical workload in favor of practical activities (48.6%) and the integration of digital technologies into assessment processes (32.4%) also emerged as relevant areas for development.

4 Discussion

The results of this study show that, although faculty in Higher Artistic Education (EAS) in music in the Valencian Community employ assessment methods that are partially aligned with the competence-based paradigm, the effective implementation of this model remains incomplete and heterogeneous. The finding that some general competences—especially those linked to technical mastery and performance—receive high ratings, whereas others, such as those related to interdisciplinary integration or professional projection, obtain lower scores is consistent with previous research pointing to an incomplete transition toward authentic assessment in EAS (Vernia, 2019; Checa, 2022).

The preference for performative methods and direct observation confirms the persistence of the “one-to-one” model characteristic of this tradition (Gaunt, 2010; Carey et al., 2021), which limits the incorporation of more integrative and collaborative approaches. The lack of interdepartmental coordination and shared rubrics, together with limited specific training in competence-based assessment, reproduces structural barriers already described in other European contexts and undermines the internal coherence of the curriculum (Iglesias and Tejada, 2024).

The ambivalent perception of the system’s fairness and the limited confidence in its capacity to prepare students for professional life suggest a mismatch between the stated educational goals and the real demands of the music labor market. The statistically significant associations among perceived formative improvement, equity, and professional preparation reinforce the idea that implementing the competence-based model must be approached systemically, explicitly linking assessment to the professional competences demanded.

Faculty perceptions suggest that the misalignment between assessment practices and the demands of the music labor market manifests itself in several ways. First, assessments tend to prioritize technical mastery and individual performance in controlled academic contexts, but they seldom evaluate transversal competences such as teamwork, adaptability, creativity, or digital literacy, which are increasingly required in the professional music sector (Vicente and Aróstegui, 2003; Carey et al., 2021). Second, there is a limited integration of professional scenarios—such as auditions, collaborative projects, or interdisciplinary productions—into assessment processes, which reduces the authenticity of the competences being measured (Gaunt, 2010; Iglesias and Tejada, 2024). Third, the absence of common rubrics and interdepartmental coordination leads to fragmented evaluation criteria, making it difficult to connect academic achievements with the competences that employers expect from graduates. Finally, instructors themselves acknowledge that numerical grading often outweighs qualitative feedback, which restricts the formative and professionalizing value of assessment practices (Ravela et al., 2017; McArthur, 2019).

In the broader context of the EHEA, these results underscore the need to strengthen the assessment culture through shared criteria, enhanced faculty development, and the integration of authentic performance scenarios that connect with real professional practice. It would also be pertinent to explore collegial and interdisciplinary assessment strategies that overcome current fragmentation and promote students’ self-regulation and critical thinking.

The analysis highlights the inherent complexity of implementing competence-based assessment in higher artistic education in music. Beyond the specific results, the study confirms that this assessment model cannot be understood in isolation, but rather as part of a broader fabric that includes institutional culture, teacher training, resources, and social expectations.

The transition toward an effective competence-based approach requires time, collective commitment, and constant reflection on the aims of music education. In this sense, assessment should serve not only as a measurement tool but also as a space for students’ holistic development and for the transformation of teaching practices.

Future research should broaden the size and diversity of the sample, include the student perspective, and analyze longitudinally the impact of specific reforms on learning outcomes and graduates’ professional insertion. This would not only validate the findings presented here but also inform policies and practices that support the full adaptation of higher music education to the twenty-first-century competence-based paradigm. In addition, combining quantitative approaches with qualitative methodologies such as ethnography could provide new insights, as direct observation and participation in teaching and learning dynamics would capture nuances often overlooked by more rigid instruments. Incorporating these lived experiences from the field would enrich the understanding of how competence-based assessment is enacted in practice and how it resonates with the real demands of professional life.

The path undertaken offers significant opportunities to rethink the relationship between curriculum, teaching, and assessment in higher music education, and it poses challenges that can only be addressed through a shared vision sustained over time.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Higher Institute of Artistic Education of the Valencian Community (ISEACV). ISEACV is an autonomous body of the Valencian Regional Government that coordinates, supervises, and regulates the higher educational institutions in the arts of the Valencian Community. ISEACV does not have an established ethics committee; however, the research was approved and funded by its Research Coordination and Evaluation Commission (CCAI) [DOGV-V-2025-465]. Compliance with current data protection legislation was ensured, and the ethical principles applicable to research involving adult participants were respected. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was not obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article because the questionnaire included an informed consent statement indicating that participation was voluntary, that completion of the questionnaire implied consent for the use of responses within the framework of the research, and that participants could withdraw at any time without consequences.

Author contributions

GE: Software, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Visualization, Methodology. TM-B: Validation, Data curation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision, Resources. LM: Project administration, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by ISEACV-Generalitat Valenciana, grant number published in DOGV-V-2025-465 and the APC was funded by Conservatori Superior de Música “Salvador Seguí.”

Acknowledgments

We thank the directors, department heads, and administrative staff of the public Higher Conservatories of Music in the Valencian Community for facilitating the distribution of the survey, and the participating faculty for their time and thoughtful responses. We also acknowledge the iMUSED research group at the Universitat de València for expert review and validation of the questionnaire.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI; GPT-5 Thinking, August 2025) to assist with ES–EN translation and redrawing figures from author-provided data. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1697717/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

ANECA, National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation of Spain (Agencia Nacional de Evaluación de la Calidad y Acreditación); EAS, Higher Artistic Education in Spain (Enseñanzas Artísticas Superiores); CSM, Conservatorio Superior de Música; EHEA, European Higher Education Area; ESG, Standards and Guidelines for Quality Assurance in the European Higher Education Area; GC, General Competences; LOE, Organic Law 2/2006 on Education (Ley Orgánica 2/2006, de 3 de mayo, de Edu-cación); LOMLOE, Organic Law 3/2020 amending the LOE (Ley Orgánica 3/2020); MECES, Spanish Qualifications Framework for Higher Education (Marco Español de Cualificaciones para la Educación Superior); RD, Royal Decree (Real Decreto); ST, Standard Deviation.

Footnotes

References

Arruti, A., and Paños-Castro, J. (2025). 21st century educational challenges for a changing society: a bibliographic review. Qualit. Res. Educ. 14, 96–115. doi: 10.17583/qre.16374

Carey, G., Grant, C., and Valdebenito, M. (2021). Profesores de instrumento o profesores como instrumento? De lo transferencial a lo transformativo en los enfoques de la pedagogía uno-a-uno. Rev. Music. Chil. 75, 175–183. doi: 10.4067/s0716-27902021000200175

Checa, R. (2022). La evaluación de las Enseñanzas Artísticas Superiores. Avances Supervisión Educ. 38, 1–31. doi: 10.23824/ase.v0i38.769

Domínguez-Lloria, S., and Pino-Juste, M. (2021). Análisis de la formación pedagógica del profesorado de los Conservatorios Profesionales de Música y de las Escuelas Municipales de Música. Rev. Electrón. Complut. Investig. Educ. Mus. 18, 39–48. doi: 10.5209/reciem.67474

Escorihuela, G., Cotolí, J. E., Botella, A. M., and Porta, A. (2024). Exploring the assessment of musical praxis through ICT in the academic context. Front. Educ. 9:1438721. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1438721

Escorihuela, G., Martínez-Bayona, T., and Marzal-Raga, L. (2025). “La evaluación por competencias en el contexto del profesorado de educación musical superior” in I Congreso Internacional de Innovación en Educación: Innovando hoy, educando para el futuro. eds. P. Villaciervos-Moreno and F. J. Recio-Muñoz (Valencia: Universidad Internacional de Valencia), 200–201.

Gaunt, H. (2010). One-to-one tuition in a conservatoire: the perceptions of instrumental and vocal students. Psychol. Music 38, 178–208. doi: 10.1177/0305735609339467

Harnoncourt, N. (2006) La música como discurso sonoro: hacia una nueva comprensión de la música. Translated by Milán, J. L.. Barcelona: Acantilado.

Iglesias, P., and Tejada, J. (2024). El modelo formativo de músicos profesionales: cultura académica, prácticas pedagógicas y procesos cognitivos. OPUS 30, 1–22. doi: 10.20504/opus2024.30.12

Jorba, J., and Sanmartí, N. (1993). La función pedagógica de la evaluación. Rev. Aula Innov. Educ. 20, 20–30.

Jornet, J. M., González, J., Suárez, J. M., and Perales, M. J. (2011). Diseño de procesos de evaluación de competencias: consideraciones acerca de los estándares en el dominio de las competencias. Bordón Rev. Pedag. 63, 125–145.

Jornet-Meliá, J. M., Carmona, C., and Bakieva, M. (2012). Hacia una definición del constructo de colegialidad docente Estrategias metodológicas de evaluación. Rev. Iberoamericana Eval. Educ. 5, 179–185. doi: 10.15366/riee2012.5.1.012

Kingsbury, H. (1988). Music, talent and performance: A conservatory cultural system. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

López Jiménez, N. E. (1997). La educación superior desde las exigencias del siglo XXI (Lineamientos Curriculares). Rev. Paideia Surcolombiana 6, 7–19.

Martín, E., Mateos, M., Martínez, P., Cervi, J., Pecharromán, A., and Villalón, R. (2006). “Las concepciones de los profesores de primaria sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje”, in Nuevas formas de pensar la enseñanza y el aprendizaje: las concepciones de profesores y alumnos, eds. J. I. Pozo, N. Scheuer, M. P. Pérez Echevarría, M. Mateos, E. Martín, and M. Cruzde la (Barcelona: Editorial Graó), 143–159.

McArthur, J. (2019). La evaluación: Una cuestión de justicia social. Perspectiva crítica y prácticas adecuadas. Madrid: Narcea Ediciones.

Nettl, B. (1995). Heartland excursions: Ethnomusicological reflections on schools of music. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Peralta-Jaen, A. H., Bautista-Vallejo, J. M., Hernández-Carrera, R. M., and Vieira-Fernández, I. (2020). Aprendizaje y evaluación por competencias. Una experiencia de innovación en la formación del profesorado de Educación Primaria. Cuad. Pedagog. Univ. 17, 83–98. doi: 10.29197/cpu.v17i34.399

Ravela, P., Picaroni, B., and Loureiro, G. (2017). ¿Cómo mejorar la evaluación en el aula? Reflexiones y propuestas de trabajo para docentes. México: Aprendizajes Clave.

Vernia, A. M. (2019). Las competencias en educación y formación musical. La programación didáctica por competencias en los conservatorios y escuelas de música. Sevilla: Punto Rojo Libros.

Vicente, A., and Aróstegui, J. L. (2003). Formación musical y capacitación laboral en el grado superior de música, o el dilema entre lo artístico y lo profesional en los conservatorios. Rev. Elect. LEEME 12, 13–26. doi: 10.7203/LEEME.12.9746

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., and Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 17, 89–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

World Medical Association (2015). Declaration of Helsinki: medical research involving human participants. Available online at: https://www.wma.net/what-we-do/medical-ethics/declaration-of-helsinki/ [Accessed August 11, 2025].

Keywords: competency-based assessment, higher music education, music conservatories, teacher perceptions, educational evaluation, professional readiness, music education policy

Citation: Escorihuela G, Martínez-Bayona T and Marzal L (2025) Competence-based assessment in higher music education: faculty perceptions in the Valencian Community. Front. Educ. 10:1697717. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1697717

Edited by:

Paula Guerra, University of Porto, PortugalReviewed by:

Castellary Macarena, University of Almería, SpainLucas Wink, University of Porto, Portugal

Copyright © 2025 Escorihuela, Martínez-Bayona and Marzal. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guillem Escorihuela, Z3VpbGxlbS5lc2NvcmlodWVsYUB1di5lcw==

Guillem Escorihuela

Guillem Escorihuela Tíscar Martínez-Bayona

Tíscar Martínez-Bayona Lluís Marzal2

Lluís Marzal2