- Department of Special Education, College of Education, Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

Background: Effective implementation of the Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) depends largely on teachers' knowledge, attitudes and preparedness. This study assesses teachers' perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement the MTSS for students with disabilities.

Method: This study employed a cross-sectional descriptive survey design using descriptive analysis. Data were collected from 413 teachers from kindergarten, elementary, intermediate, and secondary mainstream schools across Riyadh, Saudi Arabia who were recruited using the simple random sampling method.

Result: The findings revealed that teachers have a high level of knowledge of (M = 3.95, SD = 0.679), a positive attitude toward (M =3.93, SD= 0.717), and a strong readiness to (M =4.08, SD = 0.709) implement MTSS.

Conclusion: The findings highlight the need for ongoing professional development to translate teachers' positive perceptions into effective MTSS practices. Future research should examine how these factors translate into practices. The application of qualitative methods would provide deeper insights into how teachers apply MTSS in practice.

1 Introduction

The extended reach of inclusion has given rise to the need to develop multiple systems to support and meet the needs of all students. Teaching methods started to be developed that were directed at modifying student behaviors and confronting the challenges related to reading for students with learning disabilities (Sailor et al., 2009). In the mid-1980s, positive behavior modification programmes were initiated to provide teachers with educational practices for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) to assist them with educational environment problems (Sailor et al., 2009). PBIS can be defined as an implementation framework designed to enhance behavioral, academic, and social outcomes for all students through: (a) emphasizing the use of information to make and implement decisions, as well as monitoring the progress of evidence-based behavioral practices, and (b) organizing resources and systems to improve the accuracy of permanent implementation (Sugai and Simonsen, 2012), as the Response to Intervention (RTI) model becomes the main intervention method related to academic and behavioral aspects (Sailor et al., 2009). RTI is defined as a model that examines all students for academic and behavioral problems, monitors the progress of students at risk of difficulties in identified areas, and provides increasingly intensive interventions based on progress-responsive monitoring assessments (Vaughn and Fuchs, 2003).

In 2008, strong evidence emerged suggesting the importance of merging the PBIS and RTI systems into one system, forming the multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) in order to support all students, including students with disabilities (Kozleski and Waitoller, 2010). MTSS is defined as an incessant framework of system-wide practices rooted in research that uses data-driven decision-making to address the academic, behavioral, social, and emotional needs of all students (Batsche, 2014, p. 183). MTSS is a model of preventative and differential instruction designed to meet the needs of all learners (Burns et al., 2016). Recently, MTSS has received increasing worldwide attention in the field of education. Its application is helping schools achieve the aims of inclusive education (Sailor et al., 2021). MTSS models usually rely on research, practice, and establishing partnerships between the school and the local community. They are often integrated into school health services, which allows for greater flexibility and responsiveness when meeting the needs of different students (Collins et al., 2019). Key features of MTSS include shared leadership, holistic examination and progress monitoring evaluation, scaffolded learning in which the intensity is adjusted according to the needs of the students, data-driven team decisions, family–school–community partnerships, and continuous support (Pentimonti et al., 2017).

The MTSS framework is structured as a three-tiered continuum, relying on evidence-based practices to provide varying levels of support according to students' needs. At the universal level, Tier 1 delivers high-quality instruction and preventive strategies for all students. Tier 2 offers targeted interventions for students at risk, while Tier 3 provides intensive, individualized support for those with significant needs. By integrating data-driven decision-making and evidence-based interventions, MTSS seeks to ensure equitable access to education and promote positive outcomes for all learners (Sailor et al., 2021). There are six basic intervention components related to MTSS. These are (a) complementary evidence-based interventions, (b) a continuous gradual support system with increasing intensity, (c) problem-solving protocols for evaluating educational decisions, (d) progress monitoring and data-based decision rules, (e) integrity of implementation, and (f) systematic screening for early follow-up with students. These elements enhance prevention, identification, and intervention processes (Sugai and Horner, 2009). Collecting information by observing the student's behavior is crucial in assessing them and, accordingly, determining the required level of support. Therefore, information gathering is important to ensure that all students receive support services (Sailor et al., 2021).

Several models and evaluation tools have been developed to ensure effective implementation and strengthen teachers' knowledge of MTSS from both the theoretical and practical perspective, including one such model is the Forword Model, which emphasizes building teachers' knowledge, abilities, and skills (Forward et al., 2011). Among the assessment tools that have been developed to support MTSS implementation, is the Schoolwide Integrated Framework for Transformation (SWIFT), the Implementation Fidelity Rubric for the Response to Intervention Framework (Ruffini et al., 2016) and the Self-Assessment of Multi-Tiered System of Supports Implementation (Florida Department of Education, 2025). These tools provide structured mechanisms for evaluating fidelity, readiness, and effectiveness, thereby supporting schools in sustaining MTSS implementation across diverse educational contexts.

The importance of MTSS has been widely discussed in the literature, with many studies highlighting its advantages for improving students' academic achievement, fostering early behavioral development, addressing academic and behavioral challenges, and eliminating barriers to learning (Guest et al., 2024). Research has also demonstrated the value of MTSS in responding to emergency circumstances and addressing long-term disparities, such as those that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kearney and Childs, 2021). In this context, MTSS has been shown to broadly support social-emotional learning and promote good mental health (Vetter et al., 2024). Additionally, several studies have emphasized the value of incorporating the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) framework into MTSS implementation (Thomas et al., 2023; Choi et al., 2019; Alquraini and Rao, 2020). UDL provides a flexible instructional design approach that aligns with MTSS by ensuring that diverse student needs are met proactively. Similarly, Novak and Williams (2022) highlighted the importance of MTSS in meeting the wide-ranging educational needs of all learners, further reinforcing its role as a comprehensive framework for equity and inclusion. Further studies have shown the importance of MTSS in dealing with students' mental health issues (Sulkowski and Michael, 2014) and confronting psychological and behavioral problems, such as bullying of students with disabilities or students at risk (Robinson et al., 2023). However, service providers in schools have indicated that the provison of mental health services through MTSS is quite informal and needs to be more systematic (Nygaard et al., 2024). Thus, some studies have recommended launching educational–mental health system partnerships to improve the services provided within MTSS (Weist et al., 2022).

1.1 Teachers' role and challenges in implementing MTSS

Teachers serve as the primary agents of support within the MTSS framework. As Forman et al. (2013) note, the success of MTSS depends on the teachers' ability to apply strategies that address behavioral challenges and enhance students' academic and social skills, including identifying students' needs early, implementing evidence-based interventions, and collaborating with colleagues and families to ensure continuous progress. Pentimonti et al. (2017) also emphasize the fact that MTSS relies on systematic progress monitoring and data-based team decision-making, while Sailor et al. (2021) confirm that consistent data collection is essential to enable students to access appropriate support services. While the literature offers valuable insights into models of teacher development and evaluation tools, effectively meeting the students' diverse needs remains a challenge. Strengthening teachers' understanding, motivation, and preparedness to implement MTSS is therefore crucial for translating into inclusive practice.

Research has shown that the lack of knowledge and competency, negative attitudes among teachers, and insufficient training hinder the successful implementation of MTSS (Eagle et al., 2014, Werts et al., 2014; Castro-Villarreal et al., 2014). This has particularly negative consequences for students with behavioral difficulties or those diagnosed with emotional and behavioral disorders, who often struggle to meet social and behavioral expectations (Gresham et al., 2004; Maag, 2006). Such challenges are often exacerbated by teachers' limited knowledge of how to apply evidence-based practices and align with professional teaching standards (Almutairi and Alsuwayl, 2023). To address these issues effectively, teachers must develop familiarity with a wide range of strategies and methods for managing behavioral problems, fostering academic and social skills, and implementing diverse interventions (Forman et al., 2013).

Supportive school policies are also essential for implementation. When such policies are insufficient, the delivery of academic, social, and behavioral outcomes is compromised. Many schools continue to struggle with MTSS implementation due to the limited integration of evidence-based interventions into curricula, underestimation of the importance of the school environment, lack of emphasis on behavioral support, and over-reliance on assessment and classification at the expense of intervention (Dillard, 2017). As Bruggink et al. (2014) observe, when teachers lack the necessary knowledge, attitudes, or readiness to address or prevent challenging behaviors, valuable instructional time is diverted toward classroom management rather than teaching academic content.

Researchers have also noted how strongly teachers' attitudes shape their willingness to adopt MTSS practices. Studies (Jones, 2009; Paynter et al., 2017) indicate that positive beliefs enhance the application of evidence-based practices, whereas negative perceptions restrict them (Paynter and Keen, 2015). Prasse et al. (2012) and Sailor et al. (2021) state that developing appropriate knowledge, skills, and beliefs is essential for translating MTSS principles into effective practice. Thus, teachers must possess adequate knowledge, readiness, and attitudes (Reddy and Sujathamalini, 2006; Hollenweger, 2011; Nitz et al., 2023). These factors are crucial not only for accurately interpreting student behavior but also for fostering supportive teacher–student relationships and promoting inclusive practice.

Empirical research on teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS for students with disabilities remains limited, particularly within the Middle Eastern context. This gap points to the need for further investigation to better understand the factors that influence effective MTSS implementation, especially within Saudi educational settings.

1.2 The context of Saudi Arabia

Inclusion has been internationally recognized as a guiding principle for educational development and is considered essential to promoting equity and equal learning opportunities for all students. In Saudi Arabia, the right of students with disabilities to learn alongside their peers is firmly embedded in the National Education Development Plan, which emphasizes equitable access and the establishment of comprehensive support systems within mainstream and inclusive schools. These national efforts are closely aligned with the objectives of the (Saudi Vision 2030, 2016) and the Ministry of Education's first strategic goal of improving educational quality and outcomes (Ministry of Education, 2021). In support of these reforms, the Education and Training Evaluation Commission (ETEC) has integrated the MTSS into the National Professional Standards and Career Pathways for Teachers (NPSCPT) to ensure that teachers are adequately equipped with the knowledge and competencies necessary for effective implementation to meet all student's needs (Education Training Evaluation Commission, 2021).

According to the General Authority for Statistics (2022), there are approximately 1,349,585 individuals with disabilities in Saudi Arabia representing 5.9% of the total population of 32,175,224. Of these, an estimated 200,000 students with disabilities aged 6–18 years are enrolled in general education schools. This growing integration reflects the national commitment to providing equal educational opportunities and comprehensive support for all learners, in line with the National Education Development Plan. Yet, despite these notable advancements, empirical research within the Saudi context has largely focused on teachers' understanding of related models, particularly the Response to Intervention (RTI) framework, with limited attention to MTSS. For instance, Aljohani (2019) found that educational supervisors in early childhood and learning-difficulties programmes possessed high levels of RTI knowledge. Conversely, Alanazi (2023) reports that teachers of students with learning disabilities exhibited varying perceptions of RTI, indicating the absence of a consistent or standardized implementation framework. Similarly, Almutairi and Alagiri (2024) observed that teachers demonstrated moderate knowledge and neutral attitudes toward RTI application. Collectively, these findings underscore the need for broader investigations into teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS as an integrated framework to support diverse learners within Saudi schools.

This study addresses this gap and contributes to the growing body of literature in several ways. First, the study sought to establish baseline data on teachers' overall knowledge, attitudes, and readiness for implementation, within the Saudi educational context. Therefore, it was essential to first determine whether teachers possess sufficient knowledge or hold favorable attitudes and readiness toward MTSS implementation before examining the sociodemographic that may influence them. Second, it identifies the factors requiring enhancement in teacher professional development to strengthen MTSS implementation. Third, the findings offer evidence-based insights to support the ETEC in designing in-service training programmes, guiding the efficient allocation of resources, and informing practical recommendations for policymakers.

Thus, this study aims to assess teachers' perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness toward MTSS implementation in mainstream schools by addressing the following research questions:

1. What is the level of teachers' perceived knowledge of MTSS?

2. What are teachers' attitudes toward MTSS implementation?

3. To what extent are teachers ready to apply MTSS in practice?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research design

This study adopted a cross-sectional descriptive survey design to examine teachers' perceptions of their knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS for students with disabilities in mainstream schools. A cross-sectional approach is suitable for obtaining a snapshot of participants' perceptions at a specific point in time (Cummings, 2018). This design allowed for the efficient collection of data from a sample without the need for longitudinal follow-up.

2.2 Sampling technique

A random sampling method was used to recruit participants for this study. A comprehensive list of mainstream schools (kindergarten, elementary, intermediate, and secondary) across Riyadh, along with their contact information, was obtained from the General Administration of Education, Ministry of Education. The researchers then contacted the principals of the selected schools to explain the study's purpose and objectives and to obtain permission to distribute the survey. Upon approval, principals facilitated the distribution of the electronic survey link to teachers. In total, 413 teachers from mainstream schools across Riyadh participated in the study. Data collection took place during the third semester of the 2023/2024 academic year. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study participants.

2.3 Instruments

To achieve the objectives of the study, three research instruments were developed: Teachers' Perceived Knowledge MTSS Questionnaire, Teachers' Attitudes Toward MTSS Questionnaire, and Teachers' Readiness to Apply to MTSS Questionnaire.

2.3.1 The first instrument

The first instrument, which measured perceived knowledge, was developed based on relevant literature (e.g., Sailor et al., 2021; Almutairi and Alagiri, 2024). It consisted of 16 items that measured teachers' self-assessed understanding of MTSS, including its tiered structure, associated models (RTI and PBIS), instructional and monitoring strategies, relevant legislation, and collaboration with colleagues and parents. The teachers responded to the survey items using a five-point Likert scale: strongly agree (5), agree (4), neutral (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). In accordance with the study's predefined scoring scale, the questionnaire results were interpreted as follows: knowledge level: very low (1.00–1.79), low (1.80–2.59), moderate (2.60–3.39), high (3.40–4.19), and very high (4.20–5.00).

2.3.2 The second instrument

The second instrument, which measured teachers' attitudes toward MTSS, was developed based on relevant literature (e.g., Bruggink et al., 2014; Castro-Villarreal et al., 2014). It consisted of 10 items that measured teachers' attitudes toward implementing MTSS and barriers related to MTSS implementation. The teachers responded to the survey items using a five-point Likert scale: strongly agree (5), agree (4), neutral (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). In accordance with the study's predefined scoring scale, the questionnaire results were interpreted as follows: attitude type: very negative (1.00–1.79), negative (1.80–2.59), neutral (2.60–3.39), positive (3.40–4.19), and very positive (4.20–5.00).

2.3.3 The third instrument

The third instrument, which measured teachers' readiness to apply MTSS, was developed based on relevant literature (e.g., Alshaddadi and Alhossein, 2022; Alquraini and Rao, 2020). It consisted of 10 items that measured teachers' readiness to apply MTSS and share information with their colleagues, make modifications to the content of the curriculum, apply evidence-based practices, self-monitoring strategies, behavioral and academic interventions, spend additional time with students, and collaborate with teachers and parents. The teachers responded to the survey items using a five-point Likert scale: strongly agree (5), agree (4), neutral (3), disagree (2), and strongly disagree (1). In accordance with the study's predefined scoring scale, the questionnaire results were interpreted as follows: Readiness level: very weak (1.00–1.79), weak (1.80–2.59), moderate (2.60–3.39), strong (3.40–4.19), and very strong (4.20–5.00).

2.3.4 Content validity

Content validity was assessed through expert review, following recommended best practices for questionnaires development (Mengual-Andrés et al., 2016). Eight specialists in special education from academic institutions in Saudi Arabia reviewed the initial versions of the three questionnaires to evaluate their conceptual consistency, and linguistic clarity and the overall flow of these questionnaires. Based on their evaluations, one item was removed from the first questionnaire (“I have knowledge of effective teaching methods and diverse interventions for all students”) due to redundancy with other items. No items were removed from the second or third questionnaires; however, several concepts were simplified, and minor wording adjustments were made to maintain clarity. The experts agreed that the instruments were appropriate for achieving the study's objectives.

2.3.5 A pilot testing

After the expert review, a pilot test was conducted with 22 teachers working in mainstream schools to evaluate clarity, feasibility and the overall flow of the three questionnaires. Based on their feedback, several items were reworded to clarify their meaning, including adding examples and simplifying certain concepts. For the third questionnaire, one item was removed (“I am willing to use different effective instructional methods and interventions to meet students' needs”) due to redundancy with other items.

2.3.6 Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and reliability

To determine the construct validity and internal consistency of the final three instruments, analyses were performed on the main study sample (n = 413). The Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and reliability were conducted as follows.

2.3.6.1 First-instrument-teachers-perceived-knowledge-mtss-questionnaire]First instrument: teachers' perceived knowledge MTSS questionnaire

The EFA was conducted on the 15-item instrument to examine the underlying factors of teachers' perceived knowledge. Principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was employed to extract the principal factors. Sampling adequacy was confirmed by a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.926, exceeding the recommended minimum of 0.60 (Kaiser, 1974). Bartlett's test of sphericity was statistically significant (p < 0.000), indicating that the correlation matrix was appropriate for factor analysis.

The EFA extracted three factors with eigenvalues greater than one, collectively explaining 72.36% of the total variance. The first factor, “procedural knowledge related to MTSS” (eight items), accounted for 31.71% of the variance. The second factor, “conceptual knowledge” (four items), explained 24.60%, while the third factor, “knowledge of MTSS processes” (three items), accounted for 16.05%. All 15 items demonstrated factor loadings above 0.40 (Pallant, 2020), confirming the adequacy of the three-factors. Details of the factor loadings are presented in Table 2.

2.3.6.1.1 Reliability

To examine the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to assess its reliability. The results demonstrated a high level of internal consistency across the three factors, for the first factor was (α = 0.921), the second factor was (α = 0.921), the third factor was (α = 0.791), and the total score was (α = 0.934).

2.3.6.2 Second-instrument-teachers-attitudes-toward-mtss-questionnaire]Second instrument: teachers' attitudes toward MTSS questionnaire

The EFA was performed on the 10-item instrument to examine the underlying factors. Principal axis factoring with varimax rotation was used to extract the principal factors. Sample adequacy was confirmed by a KMO value of 0.898, which is greater than 0.60. Bartlett's test of sphericity was statistically significant (p < 0.000), indicating that the correlation matrix was valid for factor analysis. Two factors with eigenvalues greater than one were extracted, which together explained 82.055% of the total variance. The first factor “Attitudes toward implementing MTSS” consisting of 7 items explained 49.272% of the variance, while the second factor “barriers related to MTSS implementation” consisting of three items explained 32.783% of the variance. All items showed 10 factors loadings greater than 0.40, and thus the questionnaire consisted of two factors as shown in Table 3.

2.3.6.2.1 Reliability

To examine the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated to assess its reliability. The results of internal consistency across the two factors revealed that the first factor was (α = 0.944), the second factor was (α = 0.688), and the total score was (α = 0.912).

2.3.6.3 Third-instrument-teachers-readiness-to-apply-mtss-questionnaire]Third instrument: teachers' readiness to apply MTSS questionnaire

The EFA was conducted on the nine-item instrument to examine its underlying factor structure. Principal axis factoring was used. Sample adequacy was confirmed by a KMO value of 0.936, exceeding the recommended minimum threshold of 0.60. Bartlett's test of sphericity was also statistically significant (p < 0.000), indicating that the correlation matrix was appropriate for factor analysis. The analysis yielded a single factor with an eigenvalue greater than 1, accounting for 70.585% of the total variance. All nine items demonstrated factor loadings above 0.40, thus the questionnaire consisted of one factor as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Summary of exploratory factor analysis Summary of the exploratory factors analysis for the readiness questionnaire.

2.3.6.3.1 Reliability

To assess the reliability of the questionnaire, Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated. The results indicated a high level of internal consistency for the factor (α = 0.942).

2.4 Data collection

Ethical approval was obtained from the Center for Research and Education Policy at the Saudi Ministry of Education under No. 1129299. School principals in Riyadh were contacted and provided with the description, objectives, and purpose of the study and the electronic survey for distribution among teacher. A Google Forms Survey was used as online surveys are clearly advantageous in terms of speed of collecting data and ease of answering questions compared to traditional face-to-face or paper-based survey formats (Nayak and Narayan, 2019). The survey consisted of five sections. The first section provided an overview of the study, including its objectives, instructions for completing the survey, and a consent form outlining participants' rights and clarifying that the data would be used solely for research purposes. The second section gathered demographic information from participants, such as gender and school level. The third section included 15 items measuring perceived knowledge, while the fourth section contained 10 items assessing attitudes toward implementing MTSS. The fifth section comprised nine items evaluating teachers' readiness to apply MTSS.

Reminder emails were sent to school principals on a weekly basis over a two-month period to boost participation, resulting in a total of 413 teacher responses being received. To ensure objectivity and minimize participant bias, the administration procedures were standardized. Participant anonymity and data confidentiality were maintained. Direct interaction during questionnaire completion was eliminated, as the survey was administered through electronic links.

2.5 Data analysis

The survey data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS-27). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for this study.

3 Results

3.1 Teachers' perceived knowledge about MTSS

To address the first research question concerning teachers' perceived knowledge of MTSS, as shown in Table 5.

The overall mean and standard deviation for teachers' perceived knowledge were (M = 3.95, SD = 0.679), indicating a high level of perceived knowledge based on the study's predefined scale.

The results for the first dimension showed that teachers demonstrated a high level of knowledge in procedural related to MTSS, with an overall mean of 4.01 (SD = 0.725), which was the highest among the MTSS dimensions. The highest mean score was observed for teachers' knowledge of ways to cooperate and participate with colleagues (M = 4.17, SD = 0.784), followed by their understanding that MTSS enhances parent engagement (M = 4.14, SD = 0.871) and knowledge of methods and strategies for monitoring student progress (M = 4.12, SD = 0.791).

In addition, teachers demonstrated a high level of knowledge regarding the availability of MTSS resources (M = 4.04) and showed familiarity with the PBS model and its uses (M = 4.02). However, the lowest mean score within this dimension was recorded for knowledge of MTSS-related decisions and legislation (M = 3.85, SD = 1.036), followed by academic and behavioral interventions (M = 3.97, SD = 0.850), and evidence-based practices (M = 3.98, SD = 0.923).

For the second dimension, conceptual knowledge, teachers reported a high level of understanding, with an overall mean score of 3.79 (SD = 0.588).

Item-level analysis showed that the highest mean was recorded for teachers' awareness that MTSS considers the individual differences of all students (M = 3.97, SD = 1.006). This was followed by knowledge of the different MTSS levels (M = 3.75, SD = 1.067). Teachers also demonstrated a comparable level of understanding regarding MTSS requirements related to curriculum modifications, assessments and instructional methods (M =3.72, SD = 1.023). However, the lowest mean reported within this dimension was understanding RTI as one of the MTSS models and its role in meeting students' needs (M = 3.71, SD = 1.029).

The results for the third dimension, knowledge of MTSS processes, showed that teachers reported a high level of knowledge, with an overall mean of 3.93 (SD = 0.783). The highest-rated item within this dimension was teachers' knowledge of cooperation and communication methods with students' parents (M = 4.10, SD = 0.859), indicating confidence in family engagement practices. This was followed by teachers' awareness of their responsibilities within the MTSS problem-solving team that provides student support (M = 3.93, SD = 0.944). However, the lowest mean score reported in this dimension was knowledge of how to use data to make decisions about students (M = 3.76, SD = 0.991). These results suggest that, although teachers demonstrated an overall a high level of perceived knowledge, certain areas still require additional training and support.

3.2 Teachers' attitudes toward implementing MTSS

To address the second research question concerning teachers' attitude toward implementing MTSS, as shown in Table 6.

The overall mean and standard deviation for teachers'attitude were (M = 3.93, SD= 0.717), reflecting a positive attitude toward MTSS implementation based on the study's predefined scale. The results for the first dimension, teachers' attitudes toward implementing MTSS revealed a high level of agreement across all items, with an overall mean of 4.07 (SD = 0.735). Teachers expressed strong beliefs in the benefits of MTSS, particularly in enhancing their teaching skills (M = 4.11, SD = 0.819), reducing students' academic and behavioral problems (M = 4.11, SD = 0.829), and supporting the early and accurate identification of students' needs (M = 4.11, SD = 0.819). Although slightly lower, teachers also reported high levels of agreement regarding MTSS's role in promoting integration between general and special education (M = 4.06, SD = 0.838), facilitating collaboration between teachers (M = 4.05, SD = 0.830), providing high-quality education for all students (M = 4.03, SD = 0.874), and reducing teacher burden (M = 4.02, SD = 0.932). However, the second-dimension, barriers related to MTSS implementation, showed a lower an overall mean score of 3.58 (SD = 0.923) compared to the first one, indicating notable challenges perceived by teachers. Teachers agreed that schools have a sufficient number of teachers to implement MTSS (M = 3.76, SD = 1.099) and that MTSS requires additional time for effective implementation (M = 3.71, SD = 1.162). The lowest score emerged was for the availability of necessary school resources and supplies (M = 3.32, SD = 1.262). These findings suggest that although teachers held positive attitudes toward MTSS, they also recognized a practical barrier particularly in the availability of necessary school resources and supplies resource, which may hinder successful implementation.

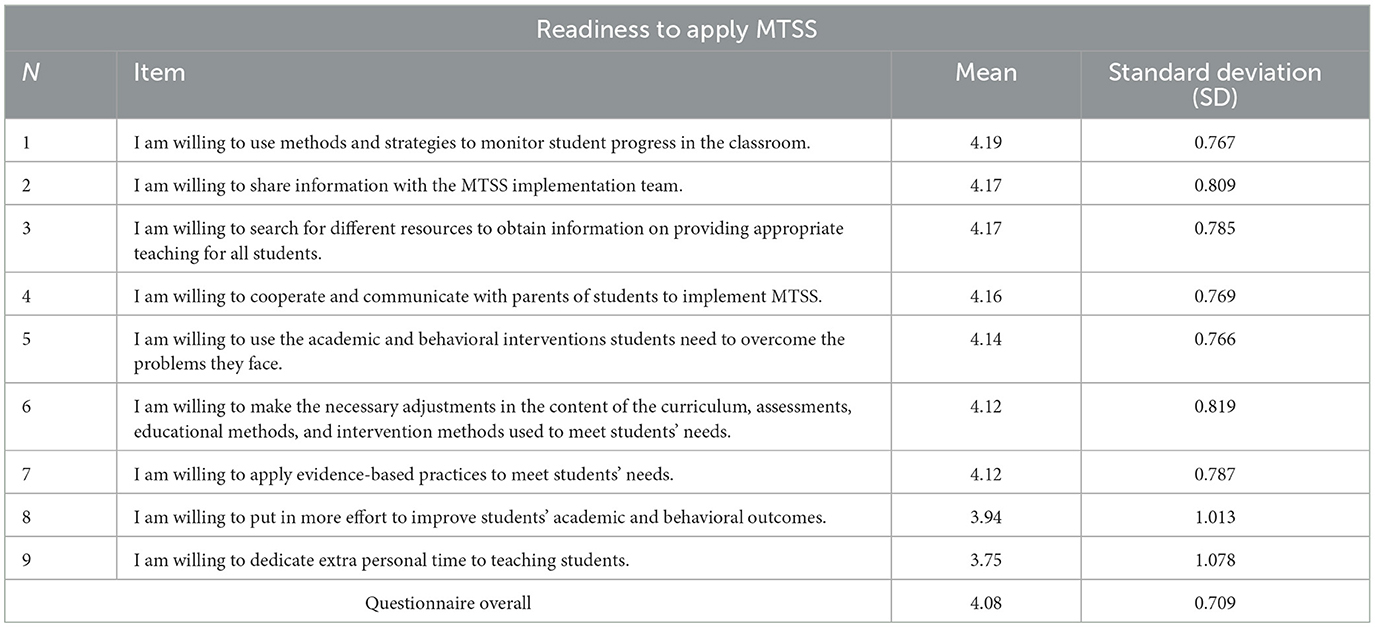

3.3 Teachers' readiness to apply MTSS

To address the third research question concerning the level of teachers' readiness to apply MTSS, as shown in Table 7.

The results for teachers' readiness to apply MTSS indicate a generally high level of preparedness, with an overall mean and standard deviation score of 4.08 (SD = 0.709) according to the study's predefined scale. Examination of the individual items shows consistently strong willingness across most readiness indicators. Teachers reported the highest levels of readiness in their willingness to use methods and strategies to monitor student progress (M = 4.19, SD = 0.767), followed by their willingness to share information with the MTSS implementation team (M = 4.17, SD = 0.809) and to search for different resources to support appropriate teaching for all students (M = 4.17, SD = 0.785). Similarly, teachers expressed strong readiness to cooperate with parents in the implementation process (M = 4.16, SD = 0.769) and to apply academic and behavioral interventions to help students overcome challenges (M = 4.14, SD = 0.766). They also indicated a high willingness to make necessary adjustments in curriculum, assessment practices, and teaching methods to meet students' needs (M = 4.12, SD = 0.819) and to use evidence-based practices (M = 4.12, SD = 0.787). However, two items showed relatively lower mean scores, though still within the high range. Teachers' willingness to put in additional effort to enhance students' academic and behavioral outcomes had a mean of 3.94 (SD = 1.013), suggesting some variability in this aspect of readiness. The lowest score was observed for willingness to dedicate extra personal time to teaching students (M = 3.75, SD = 1.078), indicating that time-related demands may pose a barrier to full MTSS readiness.

4 Discussion

The study assessed teachers' perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS for students with disabilities in mainstream schools. The statistical analysis of the first research question revealed that the overall mean and standard deviation for teachers' perceived knowledge were (M = 3.95, SD = 0.679), indicated that teachers have a high level of perceived knowledge. This finding contradicts with the results of Al-Wazzan and Al-Harkan (2023), who reported that mainstream teachers' overall level of MTSS knowledge was moderate. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that teachers' understanding of MTSS may have improved over time. This potential improvement may be associated with the incorporation of MTSS principles into the NPSCPT, which has increased teachers' exposure to the framework through ongoing professional development initiatives. As a result, teachers may have participated in training programs or workshops aligned with these standards, contributing to the higher levels of perceived knowledge observed in the present study. A similar pattern was noted in the study by Almutairi and Alsuwayl (2023), who found that a sample of 152 teachers demonstrated a moderate understanding of RTI, a key component within the broader MTSS framework. Since MTSS encompasses other practices and support beyond RTI, direct comparison should be interpreted with caution as RTI represents only one element of MTSS and may not capture the full scope of multi-tiered supports. Nonetheless, this contrast may suggest that teachers feel more knowledgeable about MTSS as a general framework than they do about RTI alone, or that the broader construct of MTSS elicits higher perceive familiarity.

Although teachers demonstrated a high level of MTSS knowledge across all dimensions, evidence in the literature indicates that awareness of MTSS may not guarantee effective implementation. Alnoaim (2021) notes that although mainstream teachers reported being aware of MTSS Tier 1 strategies, they lacked the practical skills necessary to apply these strategies effectively in classroom settings. This suggests that having a high level of MTSS knowledge may not necessarily translate into the ability to apply its principles effectively in school or classroom practice. Therefore, further research examining how teachers implement MTSS in real educational settings would provide deeper insights into the practical application of the framework.

With regard to the second research question, which examined teachers' attitudes toward applying MTSS with students with disabilities, the result of overall mean and standard deviation for teachers' attitude were (M = 3.93, SD = 0.717), indicating a positive attitude toward MTSS implementation. Their responses reflected a willingness to adopt MTSS practices and a recognition of its value in supporting inclusive education. They believe that the framework enhances their teaching skills, reduces students' academic and behavioral problems, facilitates the early and accurate identification of students' needs, promotes integration between general and special education, provides appropriate support to both general and special education teachers, ensures high-quality education for all students within the learning environment, and reduces the burden placed on teachers. Collectively, these perceptions demonstrate a positive attitude toward MTSS, which is essential for the success of its implementation in schools. This finding aligns with earlier research, as Jones (2009) and Paynter et al. (2017) emphasize that teachers' attitudes directly influence their willingness to adopt and use such practices. Similarly, Paynter and Keen (2015) noted that positive teacher attitudes foster greater knowledge and encourage the application of evidence-based practices, whereas negative attitudes can serve as a barrier to their use.

However, the second-dimension, barriers related to MTSS implementation showed the lowest mean score compared to the first dimension, with an overall mean of 3.58 (SD = 0.923), indicating notable challenges perceived by teachers. In particular, teachers expressed uncertainty about whether schools were sufficiently equipped with the necessary resources to implement MTSS effectively. This finding aligns with previous studies highlighting those adequate resources are a key determinant of successful MTSS implementation. As Norton (2022) notes, insufficient resources remain one of the major obstacles to the effective application of MTSS. This challenge is further supported by evidence from the broader literature, which shows that when schools adopt an MTSS framework, they often underestimate the extensive coordination and alignment required, while simultaneously overestimating the extent to which MTSS practices are implemented with fidelity (Arden et al., 2017; Coyne et al., 2016). Moreover, several studies suggest that partial implementation of RTI or MTSS may not lead to improve all student outcomes (Balu et al., 2015). Together, these findings underscore that resource limitations, combined with challenges in ensuring full and accurate implementation, remain significant barriers to the successful adoption of MTSS in schools.

With regard to teachers' readiness to apply MTSS with students with disabilities, the results showed that the overall mean and standard deviation for the readiness dimension were (M = 4.08, SD = 0.709), indicating a generally high level of preparedness among teachers. Participants expressed high motivation to engage in various practices, including monitoring student progress, sharing information with colleagues, consulting diverse resources, collaborating and communicating with parents, applying academic interventions, and making necessary adjustments to curriculum content, assessments, instructional methods, and intervention strategies. These findings align with those of (Alshaddadi and Alhossein, 2022), who report that most teachers in mainstream schools in Saudi Arabia demonstrate a high level of preparedness to implement MTSS. This may be attributed to two reasons: first, the financial incentives provided to teachers may increase their motivation and readiness to adopt MTSS practices; second, the ETEC has integrated MTSS principles into the NPSCPT, serving as a key policy driver that encourages continuous professional learning and promotes the use of MTSS-based strategies in practice.

Taken together, the findings of this study can be linked through the lens of implementation and behavior-change theories. Drawing on the Concerns-Based Adoption Model (Hall and Hord, 2015) and the Stages of Concern, teachers typically progress through developmental stages as they adopt and internalize new educational practices. The high level of perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness observed among participants suggest that many teachers are moving from the informational to the management stage of adoption. Continuous professional development and practical training may support teachers' progression toward the collaboration and refocusing stages, especially for new teachers to support full implementation of MTSS. In addition to the ongoing in-service training, the integration of MTSS-related content into pre-service teacher education programmes at Saudi universities becomes crucial. This has been highlighted by Forman et al. (2013) who indicated that teachers' limited knowledge and lack of confidence when it comes to teaching MTSS concepts may stem from how these topics are presented in academic coursework. This underscores the importance of providing systematic training for both pre-service and in-service teachers and evaluating the impact of such training on implementation and skill development (DeLuca and Bellara, 2013; Fuchs et al., 2012; Sailor et al., 2021), thereby ensuring sustained and long-term professional support.

Furthermore, this finding can also be interpreted through the lens of the behavioral perspective, aligning with the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), which posits that behavior is guided by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. The results of this study suggest that teachers' high level of perceived knowledge and readiness reflect a strong sense of perceived behavioral control, reinforced by national initiatives. For example, the ETEC has incorporated MTSS principles into the NPSCPT, serving as a key policy lever that motivates teachers to engage in continuous in-service teachers learning and apply MTSS-based strategies in practice. Likewise, teachers' positive attitudes toward MTSS reflect favorable evaluations of the framework, further strengthening their intention to implement it effectively. Framing these results within both psychological and national policy perspectives deepens the understanding of the mechanisms that drive teachers' engagement with MTSS and highlights the pathways necessary for sustaining educational reform in Saudi schools. However, these interpretations should be made with caution, as reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response bias and social desirability effects, which would influence how the teachers represented their perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness.

While the findings of this study are primarily descriptive and provide baseline insights, they should be interpreted with caution due to several limitations that may affect their generalizability. First, the use of a cross-sectional descriptive survey design limits the study's ability to draw conclusions about the actual effectiveness of MTSS implementation. The results are based on self-reported data collected through a questionnaire, which may be subject to social desirability bias, with participants potentially overstating their knowledge, attitudes, or readiness. Consequently, the findings reflect teachers' perceptions rather than direct observations of their practices. Therefore, future research should examine how these factors are enacted in practice. Employing a mixed-methods design and incorporating observational approaches could provide deeper insights into how teachers apply MTSS, thereby enhancing both the empirical and practical significance of future studies. Second, the current study focused on teachers' perceptions specifically their knowledge, attitudes, and readiness toward MTSS rather than on sociodemographic variables such as years of experience, or teaching specialty. This focus was intentional, as perceptions may represent the most immediate and meaningful indicators of teachers' readiness to implement MTSS practices. Nevertheless, future research is encouraged to explore how sociodemographic factors interact with teachers' perceptions to influence MTSS adoption or examine relationships between knowledge, attitudes, and readiness. Third, the study was conducted in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia, where educational resources and professional development opportunities are generally more available than in other regions. This highlights the need for future research to investigate teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS across different geographical areas, as variations in resources and institutional support may significantly influence outcomes. Furthermore, the legislative and systemic frameworks governing education and practices in Saudi Arabia differ from those in other countries, which may affect the transferability of the findings to other educational contexts.

5 Conclusions

The study's results demonstrated that the participants have a high level of perceived knowledge about MTSS, have a positive attitude toward its implementation, and feel prepared to integrate it into their practice. These positive outcomes can be linked to the professional development opportunities related to MTSS that have become increasingly widespread and accessible to teachers. This progress is supported by the ETEC, which has incorporated MTSS principles into the NPSCPT, a significant step toward ensuring that all teachers possess the competencies required for effective implementation. Such national initiatives are closely aligned with the objectives of the (Saudi Vision 2030, 2016), particularly the Ministry of Education's first strategic goal of improving teacher effectiveness and educational outcomes.

Previous research has largely examined isolated components of MTSS such as RTI or PBIS rather than examine teachers' perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness toward MTSS as a unified, comprehensive framework. Although these studies offer valuable insights, a notable gap remains in assessing teachers' perception and preparedness to implement MTSS as an integrated model, particularly within Middle Eastern contexts. This gap is especially evident in Saudi Arabia, where empirical investigations on teachers' perceptions of MTSS are still limited. To address this need, the present study provided a comprehensive overview of teachers' perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS across kindergarten, elementary, intermediate, and secondary mainstream schools in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. A key outcome of this study is its potential to inform educational officials with the implication of MTSS framework with regards to teachers' knowledge, attitudes, and readiness. The study also offers the following recommendations. First, MTSS-related content should be systematically integrated into pre-service teacher preparation programmes within universities and colleges of education to ensure that future teachers are adequately equipped with the necessary knowledge and skills. Second, the ETEC should continue to provide ongoing professional development and support, which are essential for teachers to reinforce existing knowledge of MTSS and maintain awareness of MTSS development.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from the Center for Research and Education Policy at the Saudi Ministry of Education under No. 1129299. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

NA: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. AA: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. RA: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ME: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported and funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Mohammad Ibn Saud Islamic University (IMSIU) (grant number IMSIU-DDRSP2502).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. The authors used an AI tool only to improve the clarity, coherence, and academic wording of this manuscript. All content was critically reviewed and verified by the author(s) to ensure accuracy, originality, and alignment with the research objectives. No generative AI was used to create, analyze, or interpret the study's data.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alanazi, A. (2023). How do specialists understand Response to Intervention (RTI) and use it to support children with learning difficulties? Digital Repository. Available online at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.14154/68698 (Accessed January 11, 2025).

Aljohani, B. H. (2019). The knowledge of Response to Intervention (RTI) model among early elementary levels supervisors and learning disabilities supervisors and the obstacles to its applications in Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Educ. Pract. 10, 40–47. doi: 10.7176/jep/10-26-03

Almutairi, N., and Alagiri, H. (2024). Assessing teachers' knowledge and attitudes toward implementing a response to intervention approach in the classroom. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 11, 143–153. doi: 10.21833/ijaas.2024.09.016

Almutairi, N., and Alsuwayl, A. (2023). Assessing the knowledge of elementary school teachers on universal design for learning in Saudi Arabia. Cogent. Educ. 10:2270295. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2023.2270295

Alnoaim, J. A. (2021). The Knowledge and Use of Multi-Tiered System of Supports Tier 1 Behavioral Management Strategies by Teachers in Saudi Arabia When Students with Behavioral Challenges are Included in the Classroom [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Northern Colorado. Available online at: https://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations/764 (Accessed May 7, 2025).

Alquraini, T., and Rao, S. (2020). Assessing teachers' knowledge, readiness, and needs to implement Universal Design for Learning in classrooms in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 24, 103–114. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2018.1452298

Alshaddadi, D. M., and Alhossein, A. H. (2022). The level of teachers' readiness to implement the multi-tiered system of support in inclusive schools. Int. J. Res. Educ. 46, 114–140. doi: 10.36771/ijre.46.5.22-pp114-140

Al-Wazzan, A., and Al-Harkan, M. (2023). The level of learning disabilities teachers' knowledge of Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) in schools: a descriptive study. J. Educ. Sci. Hum. Stud. 34, 150–171. doi: 10.55074/hesj.vi34.861

Arden, S. V., Gandhi, A. G., Zumeta, R., and Danielson, L. (2017). Toward more effective tiered systems: lessons from national implementation efforts. Except. Child. 83, 269–280. doi: 10.1177/0014402917693565

Balu, R., Zhu, P., Doolittle, F., Schiller, E., Jenkins, J., and Gersten, R. (2015). Evaluation of Response to Intervention Practices for Elementary School Reading (NCEE 2016–4000). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

Batsche, G. (2014). “Multi-tiered system of supports for inclusive schools,” in Handbook of Effective Inclusive Schools, eds. J. McLeskey, F. Spooner, B. Algozzine, and N. L. Waldron (London and New York: Routledge), 183–196.

Bruggink, M., Meijer, W., Goei, S. L., and Koot, H. M. (2014). Teachers' perceptions of additional support needs of students in mainstream primary education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 30, 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2013.11.005

Burns, M. K., Jimerson, S. R., VanDerHeyden, A. M., and Deno, S. L. (2016). “Toward a unified response-to-intervention model: multi-tiered systems of support,” in Handbook of Response to Intervention: The Science and Practice of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support, eds. S. R. Jimerson, M. K. Burns, and A. M. VanDerHeyden (Boston, MA: Springer US), 719–732. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-7568-3_41

Castro-Villarreal, F., Rodriguez, B. J., and Moore, S. (2014). Teachers' perceptions and attitudes about Response to Intervention (RTI) in their schools: a qualitative analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 40, 104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.02.004

Choi, J. H., McCart, A. B., Hicks, T. A., and Sailor, W. (2019). An analysis of mediating effects of school leadership on MTSS implementation. J. Spec. Educ. 53, 15–27. doi: 10.1177/0022466918804815

Collins, T. A., Dart, E. H., and Arora, P. G. (2019). Addressing the internalizing behavior of students in schools: applications of the MTSS model. Sch. Ment. Health 11, 191–193. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-09307-9

Coyne, M. D., Oldham, A., Leonard, K., Burns, D., and Gage, N. (2016). “Delving into the details: implementing multi-tiered K-3 reading supports in high priority schools,” in Challenges and Solutions to Implementing Effective Reading Intervention in Schools. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, Number 154, ed. B. Foorman (New York, NY: Wiley), 67–85. doi: 10.1002/cad.20175

Cummings, C. L. (2018). “Cross-sectional design” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of communicATion Research Methods, ed. M. Allen (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc).

DeLuca, C., and Bellara, A. (2013). The current state of assessment education: aligning policy, standards, and teacher education curriculum. J. Teach. Educ. 64, 356–372. doi: 10.1177/0022487113488144

Dillard, C. (2017). Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) and Implementation Science. Long Beach, CA: California State University.

Eagle, J. W., Dowd-Eagle, S. E., Snyder, A., and Holtzman, E. G. (2014). Implementing a Multi-Tiered System of Support (MTSS): collaboration between school psychologists and administrators to promote systems-level change. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 25, 160–177. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2014.929960

Education and Training Evaluation Commission (2021). National Academy for Evaluation, Measurement and Accreditation. Available online at: https://acpd.etec.gov.sa/Home/evaluationDefineEn (Accessed February 3, 2025).

Florida Department of Education. (2025). Multi-tiered System of Supports (MTSS). Florida Department of Education. Available online at: https://www.fldoe.org/schools/k-12-public-schools/sss/multi-tiered-sys.stml (Accessed March 5, 2025).

Forman, S. G., Shapiro, E. S., Codding, R. S., Gonzales, J. E., Reddy, L. A., Rosenfield, S. A., et al. (2013). Implementation science and school psychology. Sch. Psychol. Q. 28:77. doi: 10.1037/spq0000019

Forward, L., Killion, J., and Crow, T. L. (2011). Standards for Professional Learning. Available online at: https://cte-s.education.illinois.edu/documents/standards_pllf.pdf

Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L., and Compton, D. L. (2012). Smart RTI: a next generation approach to multilevel prevention. Except. Child. 78, 263–279. doi: 10.1177/001440291207800301

General Authority for Statistics (2022). Overall Count of Population. Available online at: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/home (Accessed February 3, 2025).

Gresham, F. M., Cook, C. R., Crews, S. D., and Kern, L. (2004). Social skills training for children and youth with emotional and behavioral disorders: validity considerations and future directions. Behav. Disord. 30, 32–46. doi: 10.1177/019874290403000101

Guest, J. D., Ross, R. A., Childs, T. M., Ascetta, K. E., Curcio, R., Iachini, A., et al. (2024). Embedding social emotional learning from the bottom up in multi-tiered services and supports frameworks. Psychol. Sch. 61, 2745–2761. doi: 10.1002/pits.23183

Hall, G. E., and Hord, S. M. (2015). Implementing Change: Patterns, Principles, and Potholes, 4th Edn. London: Pearson.

Hollenweger, J. (2011). Teachers' ability to assess students for teaching and supporting learning. Prospects 41, 445–457. doi: 10.1007/s11125-011-9197-3

Jones, M. L. (2009). A study of novice special educators' views of evidence-based practices. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 32, 101–120. doi: 10.1177/0888406409333777

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39, 31–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02291575

Kearney, C. A., and Childs, J. (2021). A multi-tiered systems of support blueprint for re-opening schools following COVID-19 shutdown. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 122:105919. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105919

Kozleski, E. B., and Waitoller, F. R. (2010). Teacher learning for inclusive education: understanding teaching as a cultural and political practice. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 14, 655–666. doi: 10.1080/13603111003778379

Maag, J. W. (2006). Social skills training for students with emotional and behavioral disorders: a review of reviews. Behav. Disord. 32, 4–17. doi: 10.1177/019874290603200104

Mengual-Andrés, S., Roig-Vila, R., and Mira, J. B. (2016). Delphi study for the design and validation of a questionnaire about digital competences in higher education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 13:12. doi: 10.1186/s41239-016-0009-y

Ministry of Education (2021). Equality in Education for Students with Disabilities. Available online at: https://moe.gov.sa/en/education/generaleducation/pages/peoplewithspecialneeds.aspx (Accessed March 02, 2025).

Nayak, M., and Narayan, K. A. (2019). Strengths and weakness of online surveys. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 24, 31–38.

Nitz, J., Brack, F., Hertel, S., Krull, J., Stephan, H., Hennemann, T., et al. (2023). Multi-tiered systems of support with focus on behavioral modification in elementary schools: a systematic review. Heliyon 9:e17506. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e17506

Norton, C. (2022). Barriers when Implementing A Multi-Tiered System of Supports [Master's thesis]. Marquette, MI: Northern Michigan University.

Novak, M., and Williams, A. (2022). Demystifying MTSS: A School and District Framework for Meeting Students' Academic and Social-Emotional Needs (Your essential guide for implementing a customizable framework for multitiered system of supports). Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Nygaard, M. A., Renshaw, T. L., Ormiston, H. E., Komer, J., and Matthews, A. (2024). Importance, quality, and engagement: school mental health providers' perceptions regarding within-district transition care coordination practices. Sch. Psychol. 39, 366–376. doi: 10.1037/spq0000569

Pallant, J. (2020). SPSS Survival Manual: A Step-by-Step Guide to Data Analysis using IBM SPSS. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003117452

Paynter, J. M., Ferguson, S., Fordyce, K., Joosten, A., Paku, S., Stephens, M., et al. (2017). Utilisation of evidence-based practices by ASD early intervention service providers. Autism 21, 167–180. doi: 10.1177/1362361316633032

Paynter, J. M., and Keen, D. (2015). Knowledge and use of intervention practices by community-based early intervention service providers. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 45, 1614–1623. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2316-2

Pentimonti, J. M., Walker, M. A., and Edmonds, R. Z. (2017). The selection and use of screening and progress monitoring tools in data-based decision making within an MTSS framework. Perspect. Lang. Lit. 43, 34–40.

Prasse, D., Breunlih, J., Giroux, D., Hunt, J., Morrison, D., and Thier, K. (2012). Embedding multi-tiered system of supports/response to intervention into teacher preparation. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 10, 75–93.

Reddy, G. L., and Sujathamalini, J. (2006). Children with Disabilities: Awareness, Attitude and Competencies of Teachers. New Delhi: Discovery Publishing House.

Robinson, L. E., Clements, G., Drescher, A., El Sheikh, A., Milarsky, T. K., Hanebutt, R., et al. (2023). Developing a multi-tiered system of support-based plan for bullying prevention among students with disabilities: perspectives from general and special education teachers during professional development. Sch. Ment. Health 15, 826–838. doi: 10.1007/s12310-023-09589-8

Ruffini, S. J., Miskell, R., Lindsay, J., McInerney, M., and Waite, W. (2016). Measuring the Implementation Fidelity of the Response to Intervention Framework in Milwaukee Public Schools. REL 2017-192. Regional Educational Laboratory Midwest.

Sailor, W., Dunlap, G., and Horner, R. (2009). Handbook of Positive Behavior Support. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-09632-2

Sailor, W., Skrtic, T. M., Cohn, M., and Olmstead, C. (2021). Preparing teacher educators for statewide scale-up of multi-tiered system of support (MTSS). Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. 44, 24–41. doi: 10.1177/0888406420938035

Saudi Vision 2030. (2016). National Transformation Program 2020. Available online at: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa

Sugai, G., and Horner, R. (2009). Responsiveness-to-intervention and school-wide positive behavior supports: integration of multi-tiered system approaches. Exceptionality 17, 223–237. doi: 10.1080/09362830903235375

Sugai, G., and Simonsen, B. (2012). Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports: History, Defining Features, and Misconceptions. Storrs, CT: Center for PBIS and Center for Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports. University of Connecticut.

Sulkowski, M. L., and Michael, K. (2014). Meeting the mental health needs of homeless students in schools: a multi-tiered system of support framework. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 44, 145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.06.014

Thomas, E. R., Lembke, E. S., and Gandhi, A. G. (2023). Universal design for learning within an integrated multitiered system of support. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 38, 57–69. doi: 10.1111/ldrp.12302

Vaughn, S., and Fuchs, L. S. (2003). Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: the promise and potential problems. Learn. Disabil. Res. Pract. 18, 137–146. doi: 10.1111/1540-5826.00070

Vetter, J. B., Fuxman, S., and Dong, Y. E. (2024). A statewide multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) approach to social and emotional learning (SEL) and mental health. Soc. Emot. Learn.: Res. Pract. Policy 3:100046. doi: 10.1016/j.sel.2024.100046

Weist, M. D., Splett, J. W., Halliday, C. A., Gage, N. A., Seaman, M. A., Perkins, K. A., et al. (2022). A randomized controlled trial on the interconnected systems framework for school mental health and PBIS: focus on proximal variables and school discipline. J. Sch. Psychol. 94, 49–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2022.08.002

Keywords: MTSS, teacher, perceived knowledge, attitude, readiness, mainstream school

Citation: Alsudairy NA, Alkeraida A, Alhilfi RA and Eltantawy MM (2025) Teachers' perceived knowledge, attitudes, and readiness to implement MTSS for students with disabilities in Saudi Arabia. Front. Educ. 10:1700274. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1700274

Received: 06 September 2025; Revised: 21 November 2025;

Accepted: 24 November 2025; Published: 12 December 2025.

Edited by:

Farah El Zein, Emirates College for Advanced Education, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Mohamed Ahmed Said, University of Jendouba, TunisiaHoucine Benlaria, Jouf University, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2025 Alsudairy, Alkeraida, Alhilfi and Eltantawy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ali Alkeraida, YWFhbGtlcmFpZGFAaW1hbXUuZWR1LnNh

Nouf Abdullah Alsudairy

Nouf Abdullah Alsudairy Ali Alkeraida

Ali Alkeraida Mahmoud Mohamed Eltantawy

Mahmoud Mohamed Eltantawy