- School of International Education, Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot, China

Although China has become an increasingly attractive destination for international education, the determinants of international students’ post-graduation retention remain underexplored. This study analyzed survey data from 643 international students to assess how perceptions of Chinese culture influence intentions to work, invest, or immigrate after graduation. Using exploratory factor analysis (EFA), three cultural dimensions—Tangible Culture, Intangible Culture, and Cultural Education—were identified. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) verified the factor structure, demonstrating high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.90) and strong construct validity. Structural equation modeling (SEM) revealed that Tangible Culture was the strongest predictor of intentions to work (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) and invest (β = 0.24, p < 0.001) in China, followed by Intangible Culture and Cultural Education, which also exerted significant positive effects. Stay intention was shaped directly by these cultural dimensions and indirectly through work and investment intentions. The findings suggest that integrating cultural immersion with education–employment pathways can strengthen China’s capacity to attract and retain international talent.

1 Introduction

China has emerged as a major global destination for international education, ranking third worldwide with over 492,000 international students in 2023 (Ajzen, 1991). This growth aligns with national initiatives such as the “Tell China’s Story Well” program, which aims to attract more internations students and improve China’s international status among international students (Ang et al., 2007). This expansion reflects a broader global trend in which nations compete for international talent, often using cultural soft power as a key mechanism for attraction and retention.

Cultural influence plays a critical role in shaping global talent mobility, foreign investment, and immigration patterns. Developed countries such as the United States, Japan, and several European nations have effectively leveraged cultural soft power—through media, education, and supportive policy incentives—to attract and retain skilled professionals and investors (Hofstede, 2011). The United States retains nearly 60% of international students through post-study work opportunities such as the OPT and H-1B programs, while Japan’s cultural exports, including anime and corporate work culture, enhance its appeal to foreign workers (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2023). Similarly, the European Union’s Erasmus+ program promotes cultural integration, with approximately 40% of exchange students considering long-term residency in their host countries (Mulvey and Lo, 2021). This highlights the potential of cultural perception, reinforced by enabling policies, to influence global talent retention.

China, with its 5,000-year-old civilization, possesses a rich cultural heritage that contributes to its international appeal. Confucian values emphasizing harmony, education, and social stability (Nye, 2004), along with traditional arts such as calligraphy and Peking opera and modern cultural exports like TikTok and globally successful media productions, enhance China’s soft power (Ram et al., 2025). Government efforts, including Confucius Institutes, talent visas, and post-study work permits, further aim to integrate cultural appeal with academic and career opportunities (Georgoudaki et al., 2025; You, 2025).

Despite these initiatives, retention rates remain low, with only 20–25% of international graduates choosing to work or settle in China (Zitong et al., 2025). Existing research on international students in China has primarily focused on academic adaptation, satisfaction, and institutional support (Guangmei, 2022; Lien and Miao, 2023; Mao, 2025). Few studies have quantitatively examined how cultural perceptions influence post-study intentions, even though evidence from migration research in Western contexts shows that cultural affinity, social integration, and economic optimism are strong predictors of long-term settlement (Azram et al., 2025; Jeremie et al., 2024; Jin, 2025). Chai and Park (2025) demonstrated that cultural adaptation predicts international students’ career decisions, while Rienties et al. (2014) found that social integration mediates academic persistence and post-graduation plans. However, such relationships remain underexplored in China, where societal norms, policy frameworks, and economic conditions differ markedly from those of Western countries.

Understanding how cultural perceptions influence students’ long-term intentions requires analytical approaches capable of capturing indirect pathways and mediating effects. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) is particularly suited for this purpose, as it allows the simultaneous estimation of complex relationships among latent variables and has been widely applied in migration, education, and behavioral studies (Chai and Park, 2025; Wang and Li, 2025).

To address this gap, this study applies SEM to examine how perceived cultural attractiveness, cultural engagement, and cultural integration influence international students post post-study intentions in China. Grounded in Acculturation Theory and the Theory of Planned Behavior, the analysis integrates both theoretical reasoning and empirical validation. While the model is theoretically informed, it also follows a prediction-oriented design that emphasizes empirical robustness over strict theory testing. The blend approach allows the study to identify the most influential cultural predictors of post-study behavioral outcomes while maintaining theoretical coherence.

2 Theoretical framework and hypotheses

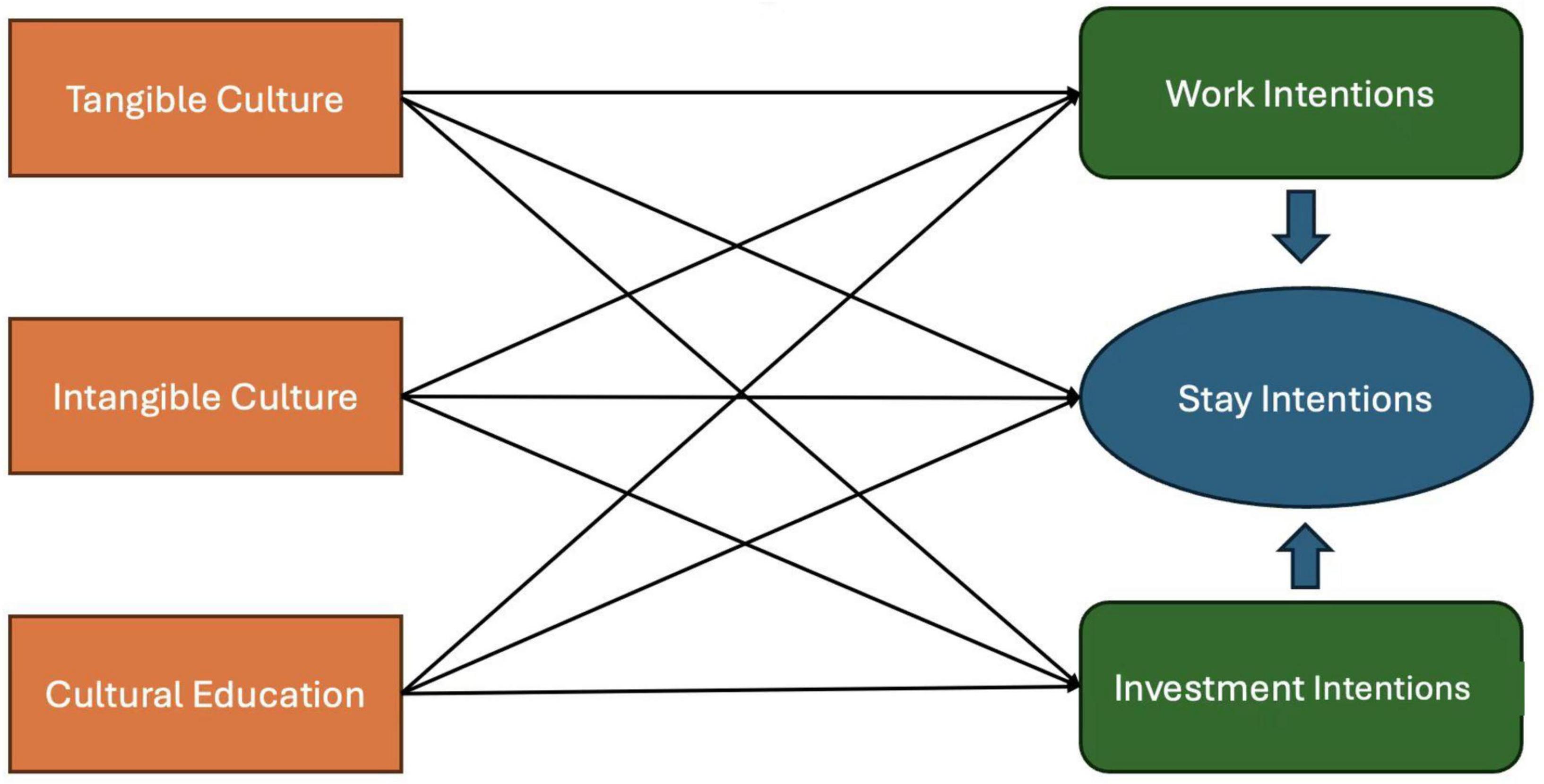

Building on the theoretical foundations outlined above, the study develops a conceptual model (Figure 1) and hypotheses (H1–H5) linking cultural dimensions to international students’ post-study intentions. This study draws on Acculturation Theory (Rienties et al., 2014) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Marsh et al., 2009) to explain how cultural engagement influences international students’ post-study intentions. Acculturation Theory emphasizes that cultural adaptation processes shape migrants’ long-term decisions, while the Theory of Planned Behavior posits that attitudes and perceived behavioral control influence behavioral intentions. These perspectives suggest that cultural experiences can affect career and investment aspirations, which subsequently shape decisions to remain in a host country.

Figure 1. The tri-cultural influence framework on international students stay intentions in china: mediating roles of work and investment intentions.

Building on these frameworks, three cultural dimensions are theorized as independent variables: Tangible Culture (T), Intangible Culture (U), and Cultural Education (E). These dimensions are expected to influence two mediating variables—Work Intentions (W) and Investment Intentions (B)—which in turn affect the ultimate outcome variable, Stay Intentions (S).

The hypotheses are as follows (Figure 1):

H1: Tangible Culture positively influences Work Intentions and Investment Intentions.

Rationale: Exposure to physical cultural symbols fosters place attachment, which can translate into career or investment interests (Berry, 2017; Muthén and Beyond, 2002).

H2: Intangible Culture positively influences Work Intentions and Investment Intentions.

Rationale: Participation in rituals and social traditions enhances cultural belonging, a key predictor of migration decisions (Ajzen, 1991).

H3: Cultural Education positively influences Work Intentions and Investment Intentions.

Rationale: Formal cultural training reduces acculturative stress and improves perceived employability (Dang and Weiss, 2021; Li et al., 2025).

H4: Work Intentions and Investment Intentions mediate the relationship between cultural dimensions (T, U, E) and Stay Intentions.

Rationale: Career and economic aspirations often act as bridges between cultural adaptation and long-term residency (Hagen-Zanker et al., 2023).

H5: Tangible Culture, Intangible Culture, and Cultural Education directly influence Stay Intentions.

Rationale: Cultural affinity can independently drive settlement intentions, as shown in studies of diaspora communities (Xu, 2020).

This conceptual framework integrates multiple theoretical perspectives to provide a comprehensive understanding of how cultural experiences shape international students’ post-study plans. By examining both direct and mediated pathways, the study contributes to literature on cultural adaptation, migration economics, and the role of educational institutions in student mobility (Bano and Liu, 2025).

3 Methodology

3.1 Data collection and measurement

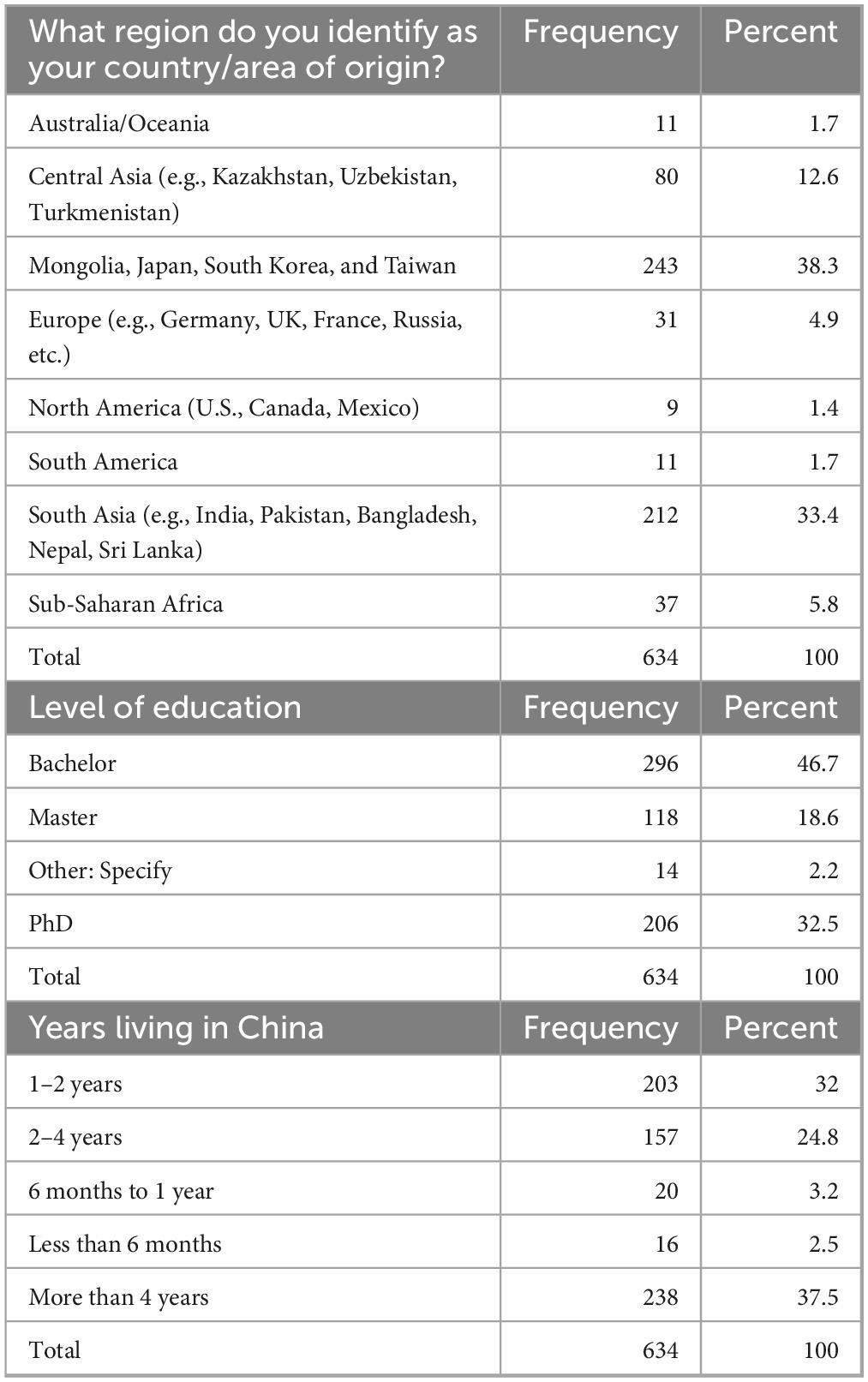

This study employed a quantitative, cross-sectional survey design to investigate how international students’ cultural experiences in China influence their post-study intentions. The descriptive statistics of the survey respondents are summarized in Table 1. A cross-sectional design was chosen because it efficiently examines relationships between variables at a single point in time, making it suitable for studying current attitudes and behavioral intentions (Dustmann and Okatenko, 2014). SEM model was selected as the primary analytical method because it simultaneously estimates multiple dependent relationships, incorporates both observed and latent variables, and accounts for measurement error (Dustmann and Okatenko, 2014). These capabilities make SEM well-suited for testing the proposed theoretical model, which includes multiple interrelated cultural dimensions and behavioral outcomes.

A structured questionnaire was developed to measure six key constructs using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree), which reliably captures subjective attitudes and perceptions (Safran, 1991).

The questionnaire items were primarily adapted from a validated instrument grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Marsh et al., 2009), Cultural Intelligence Theory (Ang et al., 2007; Gutema et al., 2024), and Hofstede’s cultural dimensions framework (Hofstede, 2011; Zhang et al., 2021). Minor contextual adjustments were made to ensure relevance to international students in China, such as modifying “host country” references to “China.” New items were generated only when no suitable existing measures were available, following standard item-generation procedures that emphasize clarity, relevance, and conceptual alignment. The instrument underwent expert review by two scholars in cross-cultural psychology to assess face and content validity, followed by a pilot test with 30 international students to refine item wording and ensure comprehension. The three cultural dimensions—Tangible Culture, Intangible Culture, and Cultural Education—represent the independent variables. Tangible Culture measures interaction with physical cultural elements such as architecture, historical landmarks, traditional arts, clothing, and cuisine. Intangible Culture assesses participation in festivals, appreciation of cultural performances, and understanding of social norms. Cultural Education evaluates institutional efforts to facilitate cultural learning through language courses, history classes, and organized cultural activities.

This study’s questionnaire consists of 33 questions in total. Among them, questions 2–25 are used for the SEM analysis, with the following variable mappings. Questions q2t–q6t measure the influence of tangible culture on international students. Questions q7u–q11u assess the impact of intangible culture on international students. Questions q12e–q14e examine the role of education in shaping students’ experiences. Questions q15w–q18w relate to international students’ intentions to work in China. Questions q19b–q21b capture students’ willingness to invest in China. Questions q22s–q25s measure long-term residency intentions in China.

Two mediating constructs—Work Intentions and Investment Intentions—capture students’ aspirations to work or invest in China after graduation. The outcome variable—Stay Intentions—assesses long-term plans to remain in China through employment, investment, or immigration. The questionnaire underwent pilot testing with 30 international students to assess clarity, content validity, and reliability. Feedback led to minor wording refinements, a standard practice to improve item interpretation before full-scale deployment (Solymosi et al., 2018).

Inclusion criteria required respondents to be non-Chinese citizens currently enrolled in Chinese universities with at least three months of residency. This ensured participants had sufficient cultural exposure to provide meaningful evaluations, as cultural adaptation typically begins after the initial adjustment period (Van Dyne et al., 2016). The final sample size exceeded the recommended various rules-of-thumb, e.g., minimum of 10 cases per estimated parameter (Ferreira et al., 2014), a minimum sample size of 100 or 200, and 5 or 10 observations per estimated parameter, ensuring sufficient statistical power for SEM (Hawe et al., 2004; Lau, 2006). Data were collected using Wenjuanxing, China’s leading academic survey platform, which provides secure storage, prevents duplicate responses, and complies with national data protection regulations. Strict anonymity was maintained by excluding personally identifiable information, addressing ethical concerns about privacy and data protection. Participants were recruited online through international student networks, social media platforms (WeChat International community groups), and university association channels across China. The survey link was distributed widely without targeting any specific university to capture a diverse range of international students studying in different regions and institution types. All participants were informed about the purpose and voluntary nature of the study, assured of confidentiality, and provided electronic informed consent before completing the questionnaire. This open, community-based recruitment approach ensured representation from various provinces and disciplines while maintaining anonymity.

Missing data accounted for less than 3% of responses and were handled using full information maximum likelihood (FIML), which yields less biased estimates than listwise or pairwise deletion when data are missing at random (Wolf et al., 2013).

3.3 Analytical procedures

3.3.1 Exploratory factor analysis

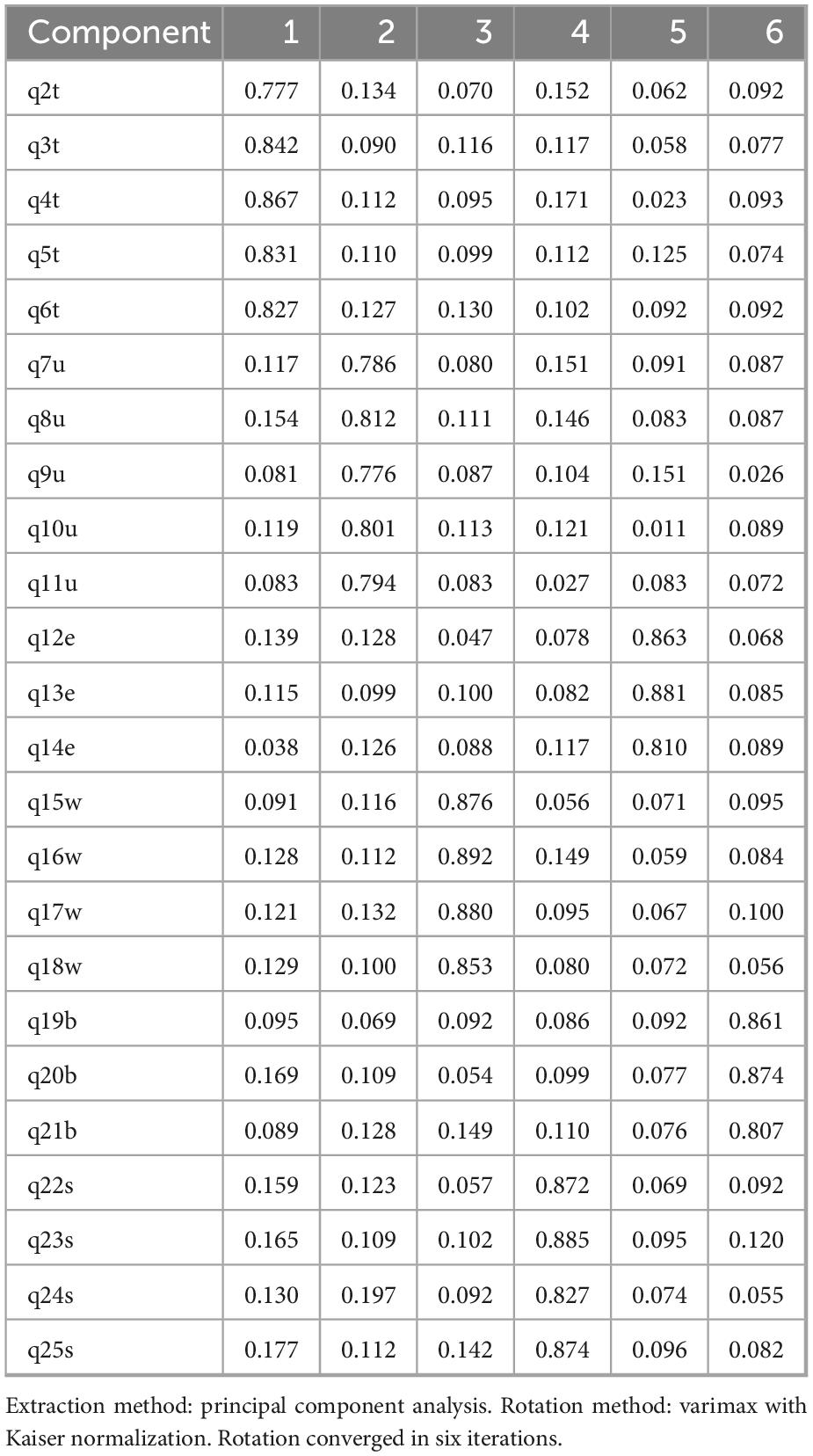

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) with Varimax rotation was conducted to examine the underlying structure of the measures and verify that items aligned with their theoretical constructs. Varimax rotation was selected because it maximizes variance among factors, providing a clear interpretation of factor structures. Items with factor loadings > 0.70 were considered strong, and cross-loadings < 0.20 were taken as acceptable (Boomsma and Hoogland, 2001).

3.3.2 Reliability analysis

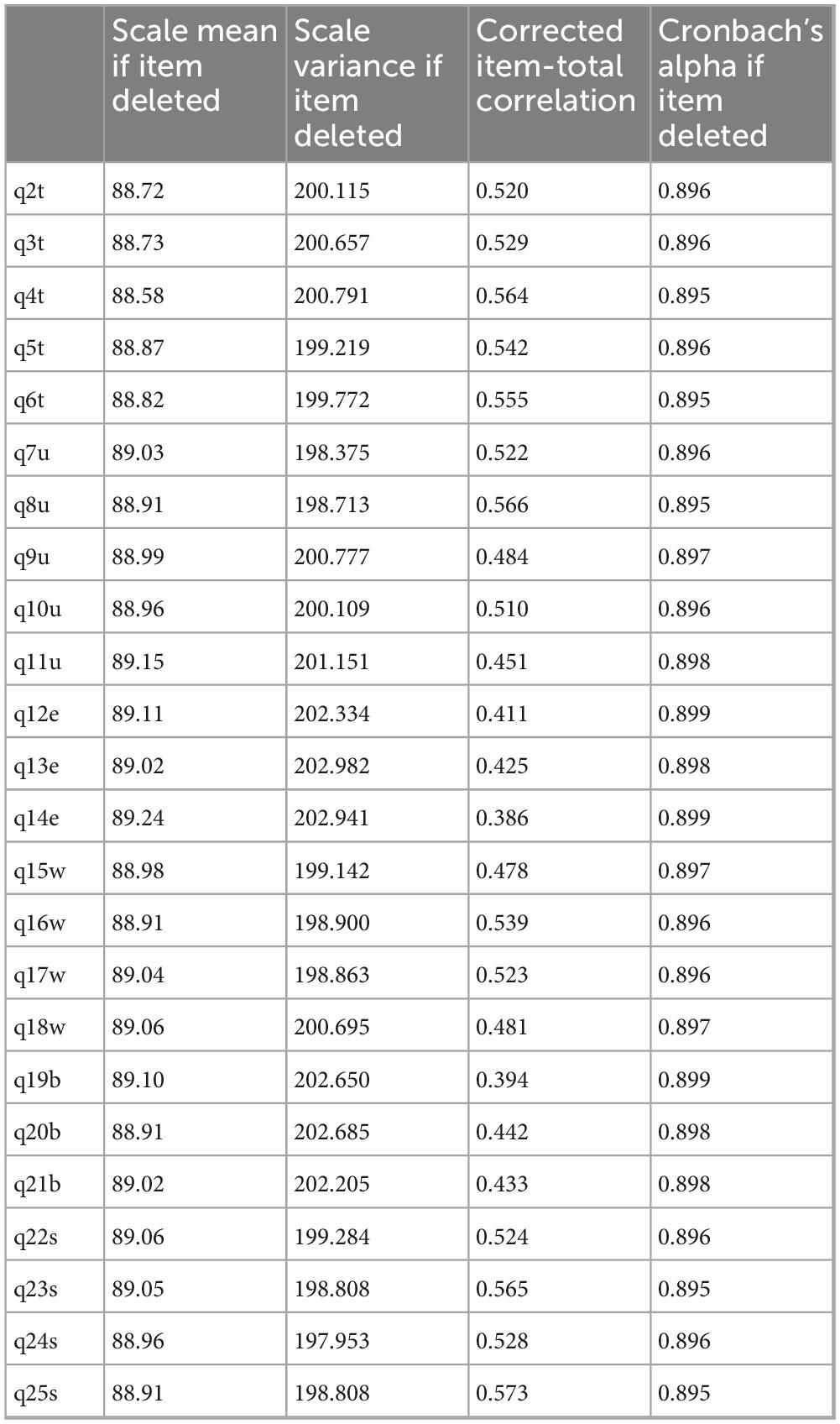

Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and corrected item–total correlations for each construct. A threshold of α ≥ 0.70 was used for acceptable reliability, with higher values indicating stronger internal consistency. Item–total correlations > 0.30 were considered acceptable. Corrected item–total statistics were also examined to assess whether deleting any item would improve reliability (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988).

3.3.3 Correlation analysis

Bivariate Pearson correlations were calculated to examine relationships among the six constructs. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.001. Coefficients < 0.40 were interpreted as moderate, indicating discriminant validity.

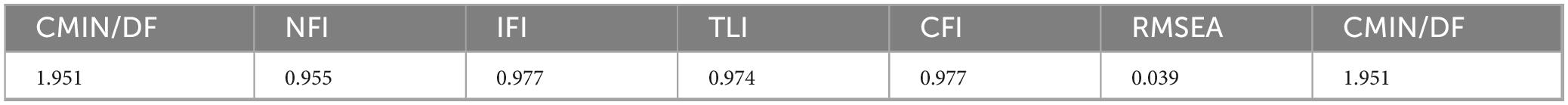

3.3.4 Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA was performed to test the measurement model’s validity before examining structural relationships. Convergent validity was evaluated using standardized factor loadings (>0.70), composite reliability (CR ≥ 0.70), and average variance extracted (AVE ≥ 0.50) (Baraldi and Enders, 2010; Park et al., 2002). Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, ensuring that each construct shared more variance with its own indicators than with other constructs (Nunnally, 1978). Model fit was evaluated with indices including RMSEA (<0.05 indicating close fit) (Brown, 2015; Fornell and Larcker, 1981), CFI, TLI, and χ2/df ratios, following recommended thresholds.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Measurement model evaluation

4.1.1 Exploratory factor analysis

The results of the EFA showed excellent psychometric properties (KMO = 0.877; Bartlett’s test p < 0.001) (Table 2). A six-factor solution explained 76.24% of the total variance (Table 3). The initial unrotated component matrix showed several items with moderate cross-loadings, such as q15w, which loaded 0.525 on

Component 1 and 0.544 on Component 2. After applying Varimax rotation, a clear and interpretable factor structure emerged, with all items loading strongly (>0.77) on their intended constructs and minimal cross-loadings (<0.20) (Table 4). Tangible culture items loaded exclusively on Factor 1 (0.777–0.867), intangible culture items clustered on Factor 2 (0.776–0.812), and stay intention items loaded clearly on Factor 4 (0.827–0.885). Rotation converged in six iterations, demonstrating a stable factor solution.

4.1.2 Reliability analysis

All constructs demonstrated high internal consistency (α > 0.90), exceeding the recommended threshold for established scales. Corrected item–total correlations ranged from 0.386 to 0.573 (Table 5), confirming that each item contributed meaningfully to its respective construct. Deleting any item did not substantially alter Cronbach’s alpha, further supporting the reliability of the scales. Items q23s and q25s exhibited particularly strong item–total correlations (0.565 and 0.573, respectively), underscoring their importance in measuring stay intentions.

4.1.3 Correlation analysis

Bivariate Pearson correlations revealed significant positive relationships among all constructs (p < 0.001), with coefficients ranging from 0.209 to 0.363 (Table 6). Tangible culture showed the strongest association with stay intentions (r = 0.363). The moderate correlations (all < 0.40) indicate that the constructs are related yet distinct, providing evidence of discriminant validity.

4.2 Confirmatory factor analysis

The CFA confirmed that the measurement model fit the data well. Strong standardized factor loadings (>0.70, p < 0.001) confirmed that all indicators effectively represented their intended constructs. Composite reliability values ranged from 0.83 to 0.92, and average variance extracted (AVE) values exceeded 0.50 for all constructs, demonstrating excellent convergent validity. The Fornell–Larcker criterion supported discriminant validity, showing that each construct’s AVE exceeded its squared correlations with other constructs. The model fit indices met recommended thresholds for good model fit (Table 7), with RMSEA < 0.05 indicating close fit.

Figure 2 illustrates the CFA results, which demonstrate excellent psychometric properties for all constructs in the measurement model. All standardized factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.716 to 0.925, and were statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating strong relationships between observed variables and their respective latent constructs. Composite reliability scores ranged from 0.8526 to 0.9248, and AVE values ranged from 0.6123 to 0.7553. All values surpassed the recommended minimum thresholds of 0.70 for CR and 0.50 for AVE, confirming strong internal consistency and convergent validity (Table 8).

Work Intentions and Stay Intentions displayed particularly robust measurement properties, with composite reliability exceeding 0.92 and AVE above 0.75, demonstrating exceptional measurement quality. Tangible Culture and Intangible Culture also exhibited high reliability (CR > 0.88). The slightly lower AVE for Intangible Culture (0.6123) suggests some shared variance among its indicators, but the factor still met the minimum threshold for convergent validity. All critical ratios for factor loadings were highly significant, ranging from 18.774 to 31.684, further confirming the adequacy of the measurement model. These results provide strong evidence that the items effectively represent their intended theoretical constructs, supporting their use in subsequent SEM.

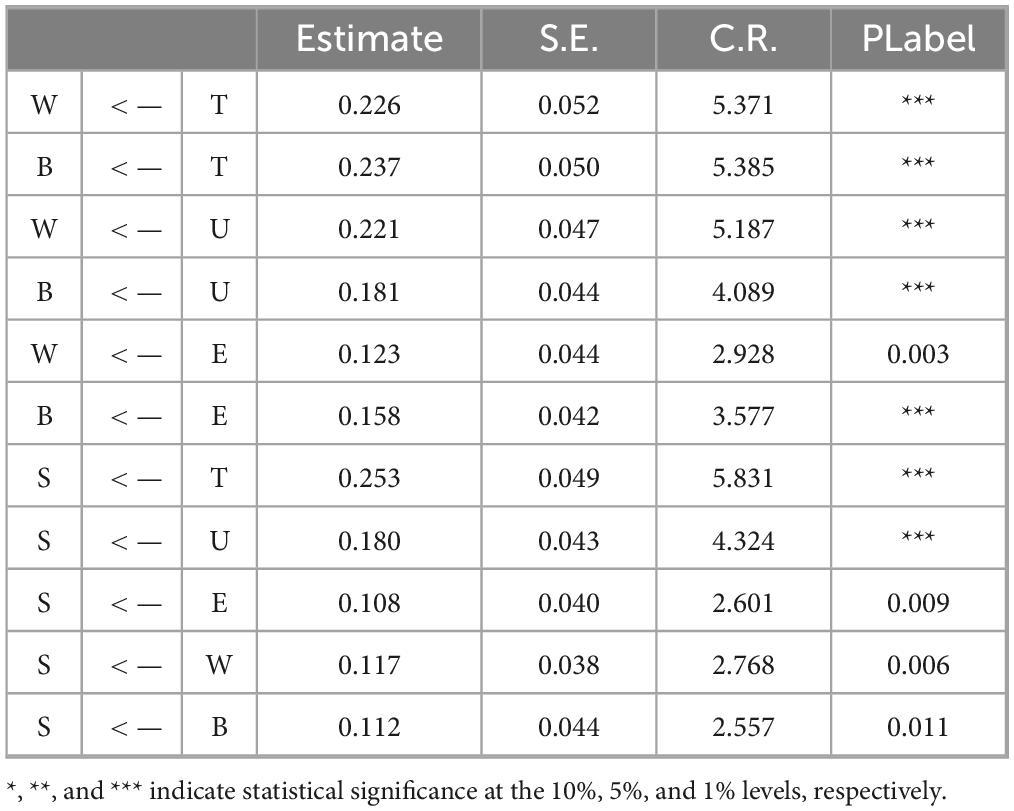

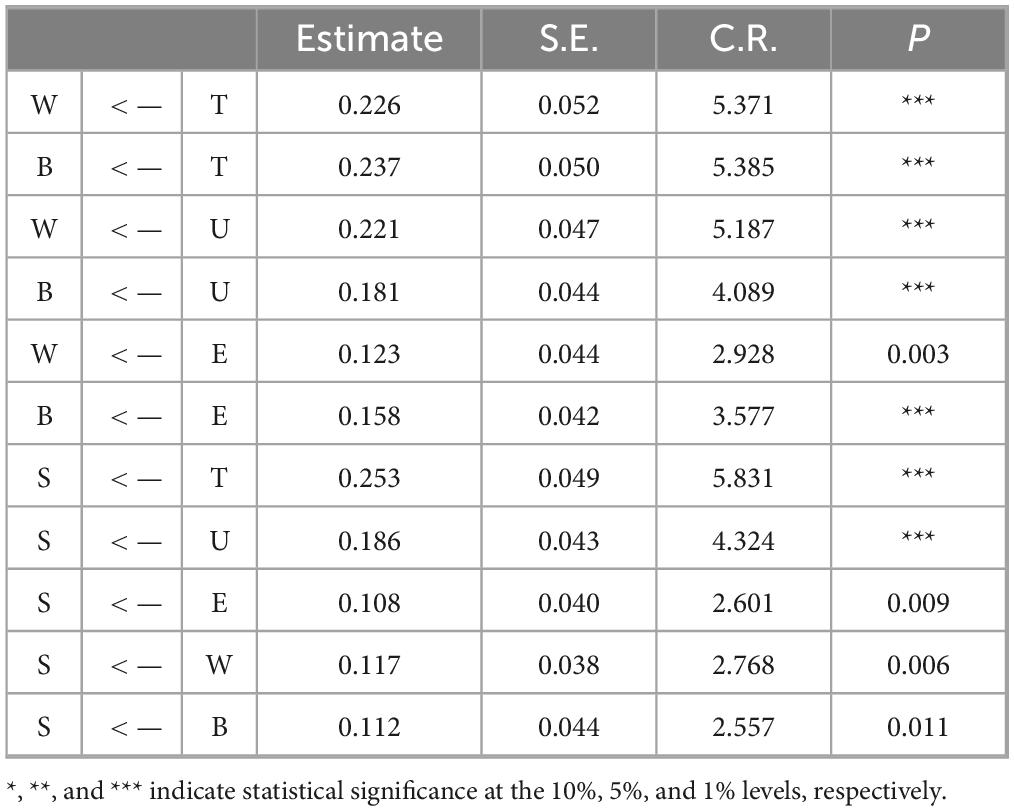

4.3 Structural model results

The standardized regression weights from the structural equation model reveal distinct patterns in how various cultural experiences influence international students’ post-study intentions (Table 9). Tangible cultural experiences emerged as the most influential factor, exerting the strongest effects on work intentions (β = 0.226) and investment intentions (β = 0.237), as well as the most substantial direct impact on stay intentions (β = 0.253). These results suggest that engagement with the physical aspects of Chinese culture—such as visiting historical sites, experiencing traditional arts, and interacting with cultural artifacts—plays a pivotal role in shaping students’ decisions after graduation.

Intangible cultural experiences showed slightly weaker yet still significant effects across all three intention types (β = 0.181–0.221), indicating that participation in festivals, traditions, and social customs meaningfully contributes to these decisions. Formal cultural education, although exerting more modest effects (β = 0.108–0.158), added unique value—particularly for investment intentions, where its influence was nearly comparable to that of intangible culture. The mediated pathways through work intentions (β = 0.117) and investment intentions (β = 0.112) were significant but relatively small, suggesting that while employment and investment considerations matter, cultural experiences primarily shape stay intentions directly rather than indirectly through these mediators. Overall, the findings indicate a clear hierarchy of influence: tangible cultural experiences are the primary driver, supported by intangible cultural participation and formal cultural education. This underscores the central role of cultural engagement in shaping international students’ intentions to work, invest, and remain in China after graduation.

4.4 Path analysis

Path analysis was conducted to examine the direct and indirect relationships between international students’ cultural experiences and their post-study intentions in China. The standardized path coefficients indicate significant relationships between cultural factors and students’ intentions to work, invest, and stay in the country (Figure 3; Tables 10, 11). Tangible cultural experiences demonstrated the strongest influence across all outcomes, exerting the highest effects on work intentions (β = 0.226) and stay intentions (β = 0.253). Intangible cultural experiences showed slightly weaker but still substantial effects (β = 0.181–0.221), while cultural education exhibited more modest yet statistically significant impacts (β = 0.108–0.158).

The mediated pathways through work intentions (β = 0.117) and investment intentions (β = 0.112) were significant but relatively small compared with the direct effects of cultural experiences. These results suggest that cultural engagement influences students’ post-study intentions primarily through direct mechanisms rather than being heavily mediated by work or investment considerations. Across all three cultural dimensions, the consistent pattern of influence (T > U > E) underscores the hierarchical importance of different cultural experiences in shaping international students’ decisions to remain in China after graduation. These findings support the design of comprehensive cultural programs that emphasize immersive, tangible experiences while also incorporating intangible cultural elements and formal educational components to maximize international student retention.

5 Discussion

The findings of this study provide strong empirical evidence that cultural engagement significantly shapes international students’ post-study intentions in China. A clear hierarchy of influence emerged, with tangible cultural experiences exerting the strongest effects on work, investment, and stay intentions, followed by intangible culture and formal cultural education. Tangible cultural experiences—such as visits to historical landmarks, participation in traditional arts, and exposure to local cuisine—appear to foster powerful place attachment, aligning with previous research showing that physical cultural symbols enhance destination loyalty and retention (Browne and Cudeck, 1993; Hair et al., 2019). These immersive experiences create emotional bonds that directly influence students’ intentions to remain in the host country. Intangible cultural engagement, while slightly less influential, also played a significant role. Participation in traditions, festivals, and social customs contributed to a sense of belonging and social integration, echoing earlier studies highlighting the role of cultural participation in migrants’ long-term settlement decisions (Hu and Bentler, 1999; Lewicka, 2011; Alba and Nee, 2015; De Leon and Cohen, 2005). Although formal cultural education demonstrated a more modest influence, its effects were statistically significant, suggesting that structured academic initiatives—such as language courses and cultural history classes—complement experiential learning and provide an additional pathway for cultural integration (Berry and Sam, 1997; Yoon and Uysal, 2005).

The mediating effects of work and investment intentions were present but relatively small compared to the direct influence of cultural engagement. This indicates that retention intentions are shaped primarily through intrinsic cultural and emotional attachment rather than being wholly dependent on practical or economic considerations. These results extend the literature on cultural adaptation and migration decision-making by underscoring the direct role of cultural factors, beyond career-related motives, in influencing students’ long-term settlement plans (Hagen-Zanker et al., 2023). The study’s implications are relevant for both policymakers and higher education institutions aiming to enhance international student retention. The strong influence of tangible cultural experiences suggests that universities should incorporate more immersive cultural programs into curricula, such as credit-bearing modules involving visits to UNESCO World Heritage sites or discipline-specific projects linking cultural heritage to professional applications. For example, business students might analyze Confucian principles in corporate governance, while architecture students could examine traditional design principles in real-world contexts.

Similarly, intangible cultural engagement could be strengthened through structured participation in community events and festivals, supported by preparatory workshops to explain cultural significance and post-event reflection sessions to consolidate learning. Interdisciplinary projects—such as marketing campaigns for traditional crafts or initiatives to preserve intangible heritage—could link cultural immersion with the development of practical skills. At the policy level, retention prospects could be improved through measures such as streamlined visa processes, expanded eligibility for the R Visa, and extended post-study work permits. Cross-cultural mentorship programs, targeted language training in specialized fields, and culturally informed career development initiatives could further support students in transitioning into the Chinese workforce. At a broader scale, the results highlight how cultural soft power can be leveraged as a strategic tool for talent retention, with potential for partnerships between universities, heritage institutions, and industries to create integrated cultural and professional experiences.

5.1 Limitations and future research

Despite these contributions, the study has several limitations. Its cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, as the relationships identified reflect associations at a single point in time rather than changes over the student experience. Moreover, reliance on self-reported data introduces social desirability or recall bias, as participants might overstate positive cultural experiences or intentions to remain in China. The sample was also limited to respondents from major Chinese universities, which may not fully capture the diversity of international student experiences across regions and institution types.

Future research should employ longitudinal designs to examine how cultural engagement and retention evolve, and comparative studies across different host countries or regions to explore contextual differences. In addition, qualitative methods—such as interviews or focus groups—could provide richer insights into how international students interpret and internalize their cultural experiences. These approaches would deepen understanding of the mechanisms linking cultural adaptation to post-study decisions and further validate the findings of this study.

6 Conclusion

This study examined how perceptions of Chinese culture influence international students’ intentions to work, invest, or remain in China after graduation. Three dimensions of cultural engagement—tangible culture, intangible culture, and cultural education—were found to significantly predict retention intentions, with a clear hierarchy of influence (tangible > intangible > education) and tangible cultural experiences exerting the strongest effects. These results highlight the importance of immersive cultural exposure in shaping students’ emotional attachment to China and their long-term commitment to stay. By integrating cultural factors into the study of global talent mobility, this research expands understanding of how cultural soft power can enhance talent retention beyond academic and economic considerations. The findings provide practical insights for universities and policymakers seeking to align cultural immersion initiatives with career pathways to improve retention outcomes. Building on these results, future studies can further explore how cultural engagement interacts with other factors, such as institutional support and labor market opportunities, to influence international students’ long-term decisions. This study underscores the strategic potential of cultural engagement as a tool for strengthening China’s position as a leading destination for global talent.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Jiyagatai: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. SC: Conceptualization, Supervision, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project, “A Survey Study on International Students’ Understanding and Communication of Chinese Culture” (Project No. 2024NDB120).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decision Proc. 50, 179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

Alba, R., and Nee, V. (2015). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Anderson, J. C., and Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103, 411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., et al. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Manag. Organ. Rev. 3, 335–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00082.x

Azram, M., Hong, M., Ahmad, W., Sohail, A., and Ahmad, B. (2025). The influence of language proficiency, acculturation stress, and institutional support in enhancing personal development of international students in China. PLoS One 20:e0315040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0315040

Bano, N., and Liu, Y. (2025). Cross cultural adaptation challenges: A study on Chinese expatriates in Muslim countries along Belt and road. Int. J. Cross Cultural Manag. 25:14705958251325689. doi: 10.1177/14705958251325689

Baraldi, A. N., and Enders, C. K. (2010). An introduction to modern missing data analyses. J. Sch. Psychol. 48, 5–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.10.001

Berry, J. W. (2017). “Theories and models of acculturation,” in The Oxford handbook of acculturation and health, eds S. J. Schwartz and J. B. Unger (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 15–28.

Berry, J. W., and Sam, D. L. (1997). “Acculturation and adaptation,” in Handbook of cross-cultural psychology. social behavior and applications, 2nd Edn, eds J. W. Berry, M. H. Segall, and C. Kagitcibasi (Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon).

Boomsma, A., and Hoogland, J. J. (2001). “The robustness of lisrel modeling revisited,” in Structural equation models: Present and future. a festschrift in honor of karl jöreskog, eds R. Cudeck, S. du Toit, and D. Sörbom (Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International), 139–168.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: Guilford publications.

Browne, M. W., and Cudeck, R. (1993). “Alternative ways of assessing model fit,” in Testing structural equation models, eds K. A. Bollen and J. S. Long (Newbury Park, CA: Sage), 136–162.

Chai, D. S., and Park, S. (2025). Personal factors and career decision self-efficacy of postsecondary international students: The moderating role of cultural adjustment. Career Dev. Quar. 73, 162–171. doi: 10.1002/cdq.12381

Dang, L., and Weiss, J. (2021). Evidence on the relationship between place attachment and behavioral intentions between 2010 and 2021: A systematic literature review. Sustainability 13:13138. doi: 10.3390/su132313138

De Leon, J. P., and Cohen, J. H. (2005). Object and walking probes in ethnographic interviewing. Field Methods 17, 200–204. doi: 10.1177/1525822X05274733

Dustmann, C., and Okatenko, A. (2014). Out-migration, wealth constraints, and the quality of local amenities. J. Dev. Econ. 110, 52–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2014.05.008

Ferreira, M. P., Serra, F. A. R., and Pinto, C. S. F. (2014). Culture and Hofstede (1980) in international business studies: A bibliometric study in top management journals. REGE-Rev. Gestão 21, 379–399. doi: 10.5700/rege536

Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Market. Res. 18, 39–50. doi: 10.2307/3151312

Georgoudaki, E., Stavropoulos, S., and Skuras, D. (2025). Regional Pathways to Internationalization: The Role of Erasmus+ in European HEIs. Urban Sci. 9:144. doi: 10.3390/urbansci9050144

Guangmei, H. (2022). Analysis of the tiktok (china)’s traditional culture communication innovation. Med. Commun. Res. 3, 43–48. doi: 10.23977/mediacr.2022.030108

Gutema, D. M., Pant, S., and Nikou, S. (2024). Exploring key themes and trends in international student mobility research—A systematic literature review. J. Appl. Res. Higher Educ. 16, 843–861. doi: 10.1108/JARHE-05-2023-0195

Hagen-Zanker, J., Hennessey, G., and Mazzilli, C. (2023). Subjective and intangible factors in migration decision-making: A review of side-lined literature. Migrat. Stud. 11, 349–359. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnad003

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., and Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–4. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hawe, P., Shiell, A., Riley, T., and Gold, L. (2004). Methods for exploring implementation variation and local context within a cluster randomised community intervention trial. J. Epidemiol. Commun. Health 58, 788–793. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014415

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Culture 2:8. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Hu, L. T., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. A Multidiscipl. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Jeremie, M., Maimaiti, G., and Ru, N. (2024). Examining international graduate students’ career willingness in China: Influencing factors and integration of professional development. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 28, 835–856. doi: 10.1177/10283153241262463

Jin, C. (2025). Aspire, Adapt, Anchor: Young Talents’ Migration and Housing Decisions in China’s Metropolitan Cities. Delft.

Lau, A. S. (2006). Making the case for selective and directed cultural adaptations of evidence-based treatments: Examples from parent training. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 13, 295–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2006.00042.x

Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 31, 207–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

Li, J., Peng, X., Liu, X., Tang, H., and Li, W. (2025). A study on shaping tourists’ conservational intentions towards cultural heritage in the digital era: Exploring the effects of authenticity, cultural experience, and place attachment. J. Asian Arch. Build. Eng. 24, 1965–1984. doi: 10.1080/13467581.2024.2321999

Lien, D., and Miao, L. (2023). International student mobility to China: The effects of government scholarship and Confucius Institute. Int. J. Chin. Educ. 12:2212585X231213787. doi: 10.1177/2212585X231213787

Mao, Y. (2025). Exploring factors associated with international students’ academic adjustment in mainland China: A systematic review from 2005 to 2023. J. Cross-Cultural Psychol. 56, 558–581. doi: 10.1177/00220221251320348

Marsh, H. W., Lüdtke, O., Robitzsch, A., Trautwein, U., Asparouhov, T., Muthén, B., et al. (2009). Doubly-Latent models of school contextual effects: Integrating multilevel and structural equation approaches to control measurement and sampling error. Multivariate Behav. Res. 44, 764–802. doi: 10.1080/00273170903333665

Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (2023). National education expenditure in 2023. Beijing: Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China.

Mulvey, B., and Lo, W. Y. W. (2021). Learning to ‘tell China’s story well’: The constructions of international students in Chinese higher education policy. Global. Soc. Educ. 19, 545–557. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2020.1835465

Muthén, B. O., and Beyond, S. E. M. (2002). General latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika 29, 81–117. doi: 10.2333/bhmk.29.81

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). “An overview of psychological measurement,” in Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders, ed. B. B. Wolman (Boston, MA: Springer).

Nye, J. S. Jr. (2004). Soft power and American foreign policy. Pol. Sci. Quar. 119, 255–270. doi: 10.1007/978-981-99-0714-4_7

Park, H. S., Dailey, R., and Lemus, D. (2002). The use of exploratory factor analysis and principal components analysis in communication research. Hum. Commun. Res. 28, 562–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2958.2002.tb00824.x

Ram, F. S. F., McDonald, E. M., Kuttan, A., and Sudarsan, I. (2025). Nursing brain drain, how do we retain our internationally qualified nurses: A close examination of push and pull factors. Pol. Polit. Nurs. Pract. 26, 136–143. doi: 10.1177/15271544251314338

Rienties, B., Luchoomun, D., and Tempelaar, D. (2014). Academic and social integration of Master students: A cross-institutional comparison between Dutch and international students. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 51, 130–141. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2013.771973

Safran, W. (1991). Diasporas in modern societies: Myths of homeland and return. Diaspora: A J. Trans. Stud. 1, 83–99. doi: 10.1353/dsp.1991.0004

Solymosi, R., Bowers, K. J., and Fujiyama, T. (2018). Crowdsourcing subjective perceptions of neighbourhood disorder: Interpreting bias in open data. Br. J. Criminol. 58, 944–967. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azx048

Wang, W., and Li, X. (2025). Remain or return? The effect of social network and engagement on settlement intentions among high skilled migrants in Northeast China. PLoS One 20:e0320013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0320013

Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., and Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 76, 913–934. doi: 10.1177/0013164413495237

Xu, D. (2020). To identify issues that impact upon the acculturation and adaptation of Chinese Mandarin-speaking students taking undergraduate studies in British business schools. United Kingdom: University of Salford.

Yoon, Y., and Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: A structural model. Tour. Manag. 26, 45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016

You, N. (2025). Comparative study on the path of building national communities in China and European countries from the perspective of cultural identity. J. Interdiscipl. Insights 3, 01–10. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.15769147

Zhang, K. C., Fang, Y., Cao, H., Chen, H., Hu, T., Chen, Y., et al. (2021). Behavioral intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination among chinese factory workers: Cross-sectional online survey. J. Med. Int. Res. 23:e24673. doi: 10.2196/24673

Keywords: international students, cultural perceptions, post-graduation intentions, talent retention, China, higher education, migration decisions

Citation: Jiyagatai and Chenfang S (2025) Tangible and intangible cultural drivers of international students’ retention in China. Front. Educ. 10:1702910. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1702910

Received: 13 September 2025; Accepted: 24 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Suo Yanju, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaMargaret Anthoney, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Jiyagatai and Chenfang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiyagatai, NzUwOTYyODdAcXEuY29t

Jiyagatai*

Jiyagatai* Shi Chenfang

Shi Chenfang