- 1Disaster Management Study Program, Postgraduate Program, University of Riau, Riau, Indonesia

- 2Department of Aquaculture, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, University of Riau, Riau, Indonesia

- 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Teacher Training and Education, University of Riau, Riau, Indonesia

Digital ecoliteracy, the ability to access, critically evaluate, and apply environmental information through digital platforms, is increasingly recognized as a critical competency for addressing twenty first-century sustainability challenges. This study aims to explore how critical and creative thinking predict digital ecoliteracy among Indonesian university students. Two independent samples of university students (Sample 1: N = 45; Sample 2: N = 60) participated in the study. The relationship between critical thinking, creative thinking, and digital ecoliteracy was examined using Pearson and Spearman correlations. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to assess the predictive power of these cognitive skills on digital ecoliteracy. The analysis revealed that critical thinking had strong positive correlations with digital ecoliteracy (r = 0.717–0.755, p < 0.01), while creative thinking showed moderate to strong correlations (r = 0.233–0.709, p < 0.05–0.01). Multiple regression analysis confirmed that both cognitive skills significantly predicted digital ecoliteracy, jointly explaining 72–75% of the variance (Sample 1: R2 = 0.721, β = 0.689 for critical, β = 0.394 for creative; Sample 2: R2 = 0.750, β = 0.457 for critical, β = 0.592 for creative; p < 0.001). The results indicate that fostering higher-order cognitive skills such as critical and creative thinking is a robust pathway for enhancing sustainability-oriented digital competencies. These findings align with UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development and the OECD's Learning Framework 2030, emphasizing the pivotal role of educators in facilitating digital ecological engagement. The study also highlights the need for mixed-methods research to explore the causal mechanisms underlying these relationships and addresses the limitations of a quantitative-only approach.

1 Introduction

In the 21st century, educational paradigms are increasingly emphasizing not only technological proficiency but also cognitive and environmental competencies. The digital era has transformed the way students access and process environmental information, making digital ecoliteracy a vital competency for nurturing sustainable, informed citizens. Digital ecoliteracy refers to the ability to access, evaluate, and apply environmental information through digital tools, enabling students to utilize technology for environmental awareness, problem-solving, and decision-making (Dewiyana et al., 2023). This form of literacy extends the concept of traditional ecoliteracy into the digital age, encapsulating ecological understanding within digital contexts.

Critical thinking and creative thinking stand out among the 21st-century cognitive skills that bolster digital literacy and ecoliteracy. Critical thinking involves analytical and evaluative abilities, enabling learners to assess credibility, recognize bias, and make informed decisions (Golden, 2023). Creative thinking, on the other hand, empowers learners to generate novel solutions and foster innovation in navigating complex ecological and digital challenges (Rizal et al., 2023; Kesici, 2022). Together, these skills complement one another critical thinking sharpens judgment while creativity drives adaptability and ideation (Kaufman and Beghetto, 2014; Thornhill-Miller et al., 2023).

Prior studies affirm that integrating digital literacy with critical and creative thinking fosters deeper analytical and innovative capacities in higher education. For instance, digital creativity initiatives positively influence learners' critical thinking and environmental engagement (Cojocariu and Boghian, 2024), while ecoliteracy-integrated project-based learning has been shown to significantly improve students' creative thinking and environmental awareness (Ural and Dadli, 2020). Similarly, digital media use in education contributes to ecoliteracy development, and problem-based learning strategies enhance both critical thinking and sustainability awareness (d'Escoffier et al., 2024; Wahyuni et al., 2023). Complementary findings also suggest that digital literacy positively affects creative thinking disposition, both directly and indirectly through lifelong learning (Kesici, 2022).

The integration of digital tools in education has further emphasized the importance of these competencies. Digital platforms not only facilitate access to vast information resources but also enable students to engage with diverse perspectives and complex sustainability issues (Hajj-Hassan et al., 2024). Innovative methods such as digital storytelling and virtual simulations have proven effective in enhancing ecological literacy and fostering creative engagement with environmental content (Hajj-Hassan et al., 2024). Moreover, research highlights how digital tools transform sustainability education into more interactive, data-driven, and collaborative processes, thereby strengthening students' ecoliteracy and problem-solving skills.

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of digital literacy and cognitive skills, empirical investigations that comprehensively examine their combined predictive power on digital ecoliteracy remain scarce. Previous research has demonstrated relationships between digital literacy and higher-order thinking skills, yet few studies integrate correlation and regression analyses across multiple samples (Meirbekov, 2022).

Addressing this gap, the present study explores the roles of critical and creative thinking as predictors of digital ecoliteracy among university students, contributing to the discourse on sustainable education in the digital age. Thus, the research questions of this study are:

• What is the relationship between critical thinking and digital ecoliteracy among university students?

• What is the relationship between creative thinking and digital ecoliteracy among university students?

• To what extent do critical thinking and creative thinking jointly predict students' levels of digital ecoliteracy?

• How do the findings of this study extend existing digital literacy frameworks by integrating the perspectives of UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and the OECD Learning Compass 2030 in the context of curriculum innovation and institutional strategies?

2 Theoretical background

This study addresses a critical gap at the convergence of three rapidly evolving educational domains: cognitive development, digital literacy, and sustainability education. Recent meta-analyses demonstrate that higher-order thinking skills significantly predict academic achievement and digital competencies (Liao et al., 2023; Scherer et al., 2023), yet few studies have examined their role in sustainability-oriented digital learning. The urgency of this investigation is underscored by global frameworks UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development Roadmap (2024) and the updated OECD Learning Framework 2030 (OECD, 2023), which explicitly call for empirical research linking cognitive competencies with digital sustainability education (Cervi et al., 2024; Vare et al., 2023).

The novelty of this research lies in three contributions: (1) operationalizing and validating digital ecoliteracy as an integrated construct merging digital and ecological literacy within higher education contexts (Tomczyk et al., 2023); (2) empirically testing cognitive predictors using rigorous quantitative methods across two independent samples, providing replication strengthening generalizability (Makel and Plucker, 2014); and (3) demonstrating alignment between empirical findings and global sustainability frameworks through substantial effect sizes (R2 > 0.72), offering evidence-based guidance for curriculum innovation and institutional strategy (Redecker, 2017; UNESCO, 2024).

2.1 Digital ecoliteracy: an emerging competency for sustainability

Digital ecoliteracy represents a multidimensional competency integrating digital literacy with ecological literacy to enable individuals to access, critically evaluate, and apply environmental information through digital technologies for sustainable decision-making and action (Cervi et al., 2024; Tomczyk et al., 2023). This conceptualization extends beyond traditional digital literacy focused primarily on technical proficiency (Ng, 2012), and conventional ecological literacy emphasizing environmental understanding (Capra, 2007), by positioning digital platforms as mediators of ecological knowledge and sustainability action. Digital ecoliteracy synthesizes three theoretical traditions: (1) information literacy theory, emphasizing critical evaluation of digital sources (Breakstone et al., 2021; McGrew et al., 2019); (2) media ecology, examining how digital technologies shape environmental discourse and perception (Cervi et al., 2024); and (3) Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), promoting transformative learning for sustainability (UNESCO, 2024; Vare et al., 2023).

We operationalize digital ecoliteracy through three interrelated dimensions derived from recent frameworks (Tomczyk et al., 2023; Redecker, 2017):

• Access: Capacity to locate and retrieve environmental information from diverse digital sources, including institutional databases, citizen science platforms, satellite imagery repositories, and social media, while understanding algorithmic curation and platform affordances shaping information availability (Pangrazio and Sefton-Green, 2021);

• Evaluation: Ability to critically assess credibility, relevance, accuracy, and bias of digital environmental content through source verification, lateral reading, data interpretation, and recognition of misinformation tactics such as greenwashing (Breakstone et al., 2021; McGrew et al., 2019);

• Application: Competence in translating digital environmental knowledge into sustainable practices, innovative solutions, and ecologically informed actions through creative use of visualization tools, simulation software, collaborative platforms, and digital advocacy (Liao et al., 2023).

Recent research demonstrates that digital ecoliteracy correlates positively with environmental behavior, sustainability attitudes, and civic environmental engagement among youth and young adults (Cervi et al., 2024; Tomczyk et al., 2023), underscoring its practical significance for addressing global sustainability challenges.

2.2 Critical thinking and its role in digital ecoliteracy

Critical thinking is widely regarded as the foundation of higher-order cognition. It involves logical reasoning, evaluation of evidence, and reflective judgment (Facione, 2020). Within the context of digital ecoliteracy, critical thinking is indispensable for filtering environmental information in an age of misinformation, fake news, and algorithmic biases. Students must be able to discern credible sources, evaluate data validity, and make informed judgments about environmental issues (Paul and Elder, 2019). Research indicates that critical thinking significantly predicts digital competencies, including information evaluation and digital problem-solving (Saavedra and Opfer, 2019). In sustainability contexts, students with strong critical thinking skills demonstrate greater ability to challenge unsustainable practices and advocate for evidence-based environmental actions (Rieckmann, 2018). Consequently, critical thinking serves as a bridge between raw digital information and actionable ecoliteracy, ensuring that environmental decisions are grounded in sound reasoning.

2.3 Creative thinking and innovative problem-solving

While critical thinking ensures accuracy and logical rigor, creative thinking introduces flexibility, originality, and adaptability into problem-solving processes. Creative thinking involves generating novel ideas, exploring alternative solutions, and elaborating on existing concepts to address complex challenges (Beghetto, 2021). In the digital ecoliteracy framework, creativity allows learners to harness digital tools innovatively for environmental advocacy, data visualization, and sustainable design.

Studies in educational psychology suggest that creative thinking complements critical thinking by enabling students to adapt to uncertainty and complexity, particularly in sustainability-related contexts (Robinson, 2017). For example, creative digital storytelling has been shown to enhance environmental awareness and motivate collective action (Vesala et al., 2024). Thus, fostering creative thinking in higher education equips students with the capacity to envision transformative pathways toward sustainability, thereby enriching the practice of digital ecoliteracy.

2.4 Bridging cognitive skills and environmental awareness

The synergy of critical and creative thinking forms the cornerstone of higher-order cognitive engagement in sustainability education. When applied together, these skills foster reflective, analytical, and imaginative approaches to environmental challenges in digital contexts. Critical thinking ensures that students validate the accuracy of environmental data, while creative thinking encourages innovative application of such data for solutions (Ghanizadeh, 2017). This bridge between cognitive skills and environmental awareness is crucial in an era characterized by global ecological crises and digital hyperconnectivity. Digital ecoliteracy becomes the medium through which cognitive skills are operationalized into sustainable practices, cultivating not only informed digital citizens but also environmentally responsible global citizens (Pangrazio and Sefton-Green, 2021).

2.5 Institutional and pedagogical implications

Higher education institutions play a pivotal role in embedding digital ecoliteracy within curricula and pedagogical practices. The integration of critical and creative thinking into digital ecoliteracy education requires curriculum innovation, pedagogical transformation, and institutional strategies. Project-based learning, interdisciplinary approaches, and digital simulations are effective methods for cultivating these competencies (Thomas, 2020). Moreover, aligning curricula with frameworks such as ESD and the Learning Compass 2030 ensures that students are prepared not only with technical digital skills but also with the transformative competencies necessary for sustainable futures (UNESCO, 2020; OECD, 2019). Institutions must also provide professional development for educators, ensuring that teaching strategies promote both critical analysis and creative exploration in digital environmental contexts.

3 Methods

3.1. Research design

This study employed a quantitative, correlational, and predictive design to investigate the extent to which critical thinking and creative thinking predict digital ecoliteracy among university students. Correlation and regression analyses were conducted to examine both the individual and combined effects of cognitive skills on digital ecoliteracy. Therefore, the hypotheses of this study are as follows:

H1. There is a significant positive relationship between critical thinking and digital ecoliteracy among university students.

H2. There is a significant positive relationship between creative thinking and digital ecoliteracy among university students.

H3. Critical thinking and creative thinking, when considered together, significantly predict students' levels of digital ecoliteracy.

H4. The findings will extend existing digital literacy frameworks by demonstrating that the integration of critical and creative thinking strengthens the alignment with UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) and the OECD Learning Compass 2030, providing implications for curriculum innovation and institutional strategies.

3.2. Participants

Data were collected from two independent samples of undergraduate students enrolled in a public university in Indonesia. Sample 1 (N = 45) was a group of students from the Faculty of Agriculture. Sample 2 (N = 60) was a group of students from the Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science. Both samples took an environmental science and disaster mitigation. Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling strategy. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained.

3.3. Instruments

Three validated scales were employed: (1) Digital Ecoliteracy Scale, there are: a. Adapted from prior measures of digital literacy (Ng, 2012) and ecological literacy (Lo Iacono et al., 2024); b. Assessed students' ability to access, evaluate, and apply environmental information using digital tools; c. 20 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree); and Cronbach's α = 0.89. (2) Critical Thinking Disposition Scale, there are: a. Adapted from the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (Facione, 2020); b. 15 items measuring logical reasoning, evidence evaluation, and reflective judgment; and c. Cronbach's α = 0.86. (3) Creative Thinking Scale, there are: a. Based on Torrance's framework (fluency, flexibility, originality, elaboration) (Beghetto, 2021); b. 18 items assessing students' creative problem-solving tendencies; and c. Cronbach's α = 0.84.

All instruments were administered in Bahasa Indonesia, following a translation and back-translation procedure to ensure cultural validity.

3.3.1 Digital ecoliteracy (Y)

The dependent variable of this study is Digital Ecoliteracy, which refers to students' ability to access, evaluate, and apply environmental information through digital tools. The instrument was adapted from previously validated questionnaires and covers the following aspects: (1) Access: the ability to search for and locate environmental information from digital sources; (2) Evaluate: the ability to assess the credibility, relevance, and accuracy of information; and (3) Apply: the ability to use digital information to support environmental understanding and actions. The instrument uses a Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

3.3.2 Critical thinking (X1)

The first independent variable is Critical Thinking, measured using items related to students' ability to think logically, conduct analysis, and solve problems. The indicators include: (1) Logical reasoning: the ability to draw conclusions based on evidence; (2) Analysis: the skill to identify arguments, assumptions, and evidence; and (3) Problem-solving: the ability to formulate alternative solutions and select the most rational one. The instrument employs a 5-point Likert scale.

3.3.3 Creative thinking (X2)

The second independent variable is Creative Thinking, measured through the following dimensions: (1) Fluency: the ability to generate many ideas within a short period; (2) Originality: the ability to create unique and novel ideas; and (3) Flexibility: the ability to view problems from multiple perspectives and generate diverse alternatives. The measurement was conducted using a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire.

3.3.4 Instrument reliability

All instruments were tested for reliability using Cronbach's alpha. The results showed alpha values greater than 0.7 for each construct, indicating an adequate and acceptable level of internal consistency for social research.

3.4. Procedure

Questionnaires were administered online. Data were analyzed using Pearson and Spearman correlations to examine relationships, followed by multiple linear regression to predict digital ecoliteracy from critical and creative thinking.

3.5. Data collection procedure

Data were collected in two phases during the academic year 2024/2025. Participants completed online surveys distributed via institutional learning management systems. Responses were anonymized to ensure confidentiality. Data screening procedures included handling missing values (< 5% per dataset) and checking for outliers using Mahalanobis distance.

3.6. Data analysis

Descriptive Statistics, means, standard deviations, and normality tests (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, Shapiro–Wilk) were calculated for all variables. Correlation analyses, pearson correlation was used for normally distributed data. Spearman correlation was employed for non-normally distributed data. Analyses were conducted separately for both samples (N = 45; N = 60).

Regression analyses, Multiple linear regression tested the predictive power of critical thinking (X1) and creative thinking (X2) on digital ecoliteracy (Y). Regression equations: sample 1 (N = 45): Y = −25.243 + 0.619X1 + 0.504X2 and sample 2 (N = 60): Y = 3.021 + 0.410X1 + 0.488X2. Significance level set at p < 0.05. Effect sizes were interpreted using Cohen's (1988) guidelines. Ethical considerations, this study adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional review board (IRB) of the participating universities. Students were informed of their rights to withdraw at any stage without academic penalty.

4 Results

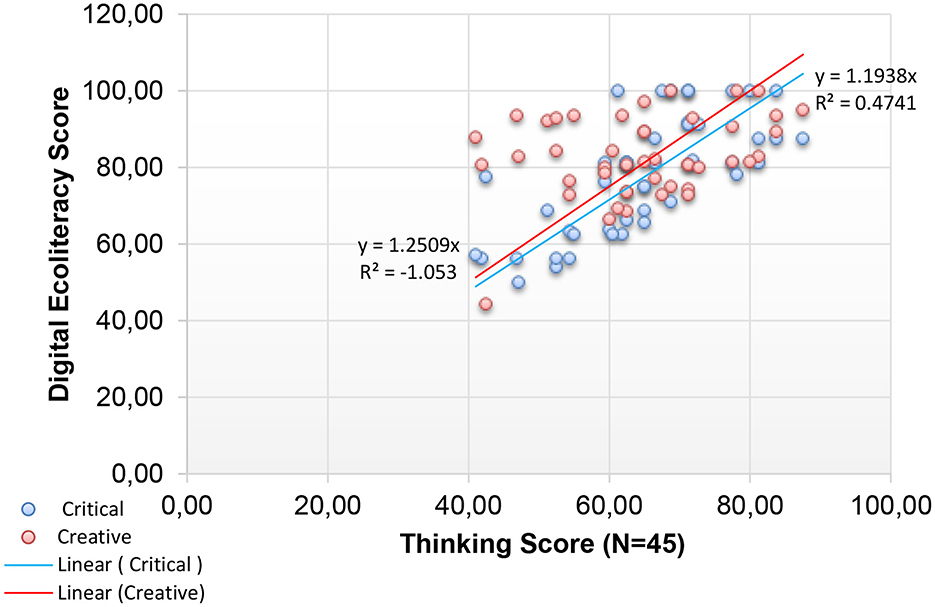

The relationship between cognitive skills and digital ecoliteracy was examined across two independent samples, as illustrated in Figures 1, 2.

Figure 1 demonstrates the distribution patterns between critical thinking, creative thinking, and digital ecoliteracy scores among 45 agricultural students. Critical and creative thinking scores ranged from 44.29 to 100.00, while digital ecoliteracy scores ranged from 41.00 to 87.50. This broad variance indicates substantial individual differences in both cognitive abilities and digital ecological competencies, suggesting that students enter higher education with diverse preparedness levels for engaging with environmental information through digital platforms (Hatlevik et al., 2018). The scatterplot reveals a positive trend: students with higher cognitive skill scores tended to demonstrate correspondingly higher digital ecoliteracy. This visual pattern suggests that critical and creative thinking may serve as foundational competencies for developing digital ecological engagement (Facione, 2020).

Figure 2 presents data from 60 marine science students, showing thinking scores ranging from 40.00 to 100.00 and digital ecoliteracy scores from 47.14 to 100.00. Notably, this sample exhibited a higher minimum digital ecoliteracy score (47.14) compared to Sample 1 (41.00), potentially reflecting greater integration of digital technologies within marine science curricula (Mogias et al., 2019). The positive relationship between cognitive skills and digital ecoliteracy appears consistent across both samples, with students demonstrating higher critical and creative thinking achieving better digital ecoliteracy outcomes. This replication strengthens confidence in the generalizability of the relationship within Indonesian higher education contexts.

4.1. Correlation and regression analysis

Based on Table 1, it can be interpreted that critical thinking shows strong positive correlations with digital ecoliteracy, whereas creative thinking has moderate correlations. The relationship between critical and creative thinking is generally weak and nonsignificant 0.3.

Based on Table 2, it can be interpreted that both critical and creative thinking significantly predict digital ecoliteracy in both samples. Critical thinking exhibits slightly higher predictive power in the N = 45 sample, while creative thinking has comparable influence in N = 60.

4.2 Discussion

Based on Figure 1, the observed ranges indicate that while some students demonstrate high levels of critical and creative thinking, others remain at moderate levels. Such disparities may be influenced by differences in prior educational experiences, digital exposure, or individual learning styles (Facione, 2020; Lai, 2011). Critical thinking involves logical reasoning, evaluation, and problem-solving skills, which are essential in analyzing environmental problems. Creative thinking, on the other hand, emphasizes originality and flexibility, allowing students to design innovative solutions to ecological challenges (Sternberg, 2012).

The variation in digital ecoliteracy scores suggests that while some students are proficient in accessing, evaluating, and applying environmental information through digital platforms, others may lack the necessary skills. Previous studies emphasize that digital ecoliteracy is not only about technical abilities but also about integrating environmental knowledge with digital problem-solving (Ng, 2012; Tang and Chaw, 2016). Higher levels of digital ecoliteracy have been linked with enhanced environmental awareness, sustainable behavior, and the capacity to mitigate ecological disasters (Koltay, 2011; Siddiq et al., 2016).

Moreover, the correlation between thinking skills and digital ecoliteracy suggests that students with stronger critical and creative thinking abilities tend to perform better in utilizing digital resources for ecological learning. This aligns with findings from research indicating that higher-order thinking skills serve as predictors of students' digital learning competencies (Tondeur et al., 2017). In agricultural education specifically, these skills are crucial for addressing complex issues such as climate change, sustainable land use, and peatland ecosystem management (Altieri, 2018).

Thus, the results highlight the importance of fostering both cognitive and digital competencies in higher education curricula. Integrating digital ecoliteracy training with activities that enhance critical and creative thinking can help prepare students to address real-world ecological challenges more effectively.

Based on Figure 2, this relationship aligns with previous studies showing that critical thinking skills contribute significantly to digital literacy and digital ecoliteracy development, as students must analyze, evaluate, and interpret digital environmental information effectively (Ennis, 2018; Facione, 2020). Creative thinking, on the other hand, supports the ability to apply digital tools innovatively for ecological problem-solving, reflecting fluency, originality, and flexibility in idea generation (Runco and Acar, 2019).

The observed range in scores indicates variability among students, which may be influenced by differences in exposure to digital technologies, educational background, and individual learning styles. Research has shown that digital ecoliteracy is not only a technical competence but also requires higher-order thinking skills such as reasoning, problem-solving, and creativity to interpret environmental challenges (Ng, 2012; Lee and Hannafin, 2016). Thus, strengthening both critical and creative thinking in the academic curriculum is essential to foster students' digital ecoliteracy, especially in addressing sustainability issues within agricultural contexts.

Overall, the distribution of scores from 40.00 to 100.00 for thinking skills and from 47.14 to 100.00 for digital ecoliteracy demonstrates a strong potential for synergy between cognitive competencies and digital ecological knowledge. These results reinforce the importance of integrating higher-order thinking into digital learning strategies to prepare students for complex environmental problem-solving in the digital age (Paul and Elder, 2019; McGuinness and Fulton, 2019).

The observed range of scores for digital ecoliteracy (47.14–100.00) compared to critical and creative thinking (40.00–100) suggests that while digital skills are relatively high among students, critical and creative thinking vary more widely. This aligns with prior research indicating that digital skills may be supported by familiarity with technology, whereas higher-order thinking requires deeper cognitive engagement and instructional scaffolding (Kong, 2014; Voogt and Roblin, 2012).

Moreover, in agricultural education, the integration of digital ecoliteracy is particularly important, as students must analyze environmental issues, interpret digital data, and propose innovative solutions to complex ecological challenges (Tilbury, 2011; UNESCO, 2021). Enhancing critical and creative thinking through problem-based learning, project work, and digital collaboration can therefore strengthen ecoliteracy and prepare students for future sustainability challenges (OECD, 2018; Zylstra et al., 2014).

Overall, Figure 2 illustrates that the development of digital ecoliteracy among agricultural students is interconnected with their higher-order thinking abilities. Educational interventions that foster critical reflection, problem-solving, and creativity are likely to enhance students' competence in navigating digital environmental information effectively.

The results of this study demonstrate that both critical and creative thinking significantly predict digital ecoliteracy, with critical thinking exhibiting slightly stronger predictive power in one sample, while creative thinking shows comparable influence in the other. These findings highlight the multidimensional role of higher-order thinking skills in fostering students' capacity to engage with environmental issues through digital platforms.

From the perspective of UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) framework, digital ecoliteracy aligns with the broader objective of equipping learners with the knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes needed to make informed decisions for environmental sustainability (UNESCO, 2020). Critical thinking enables students to evaluate the reliability and validity of digital environmental information, while creative thinking allows them to innovate and design sustainable solutions. Together, these skills empower learners to translate digital knowledge into meaningful ecological practices, which are central to the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Similarly, the OECD Learning Compass 2030 emphasizes the importance of transformative competencies, such as critical thinking, creativity, and responsibility, to navigate complex global challenges (OECD, 2019). The present study's findings provide empirical support for this framework, suggesting that higher education institutions should embed these competencies into curricula, particularly in disciplines such as agriculture, where ecological awareness and sustainable practices are vital.

The integration of digital ecoliteracy with higher-order thinking also resonates with the 21st-century skills framework, which underscores the need for students to master “4Cs”: critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and communication (Trilling and Fadel, 2009). By linking critical and creative thinking to ecoliteracy, the study confirms that sustainability education should not be limited to content acquisition, but must also prioritize cognitive and metacognitive competencies.

Moreover, higher education serves as a crucial platform for cultivating ecological citizenship among future professionals. For students in the Faculty of Agriculture, the ability to critically analyze environmental data and creatively propose solutions is particularly urgent, given the sector's vulnerability to climate change, resource depletion, and ecological degradation. As highlighted by Tilbury (2011), sustainability in education requires transformative pedagogies that encourage students not only to think critically but also to act responsibly in local and global contexts.

In sum, the integration of digital ecoliteracy with critical and creative thinking reflects a convergence of global educational agendas that seek to prepare students for a sustainable future. Higher education institutions must, therefore, design curricula that simultaneously enhance digital competencies and higher-order thinking skills, thereby supporting the development of graduates capable of addressing ecological challenges with both analytical rigor and innovative capacity.

4.2.1. Empirical validation of global sustainability education frameworks

This study's findings provide robust empirical support for recent iterations of global sustainability education frameworks. The substantial variance explained by cognitive skills (R2 = 0.72–0.75) validates UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development Roadmap (2024), which identifies critical thinking, creativity, and digital competence as “core competencies for sustainability transformation” (UNESCO, 2024, p. 47). Similarly, the OECD Learning Framework 2030, updated in 2023 to emphasize digital ecological integration positions higher-order thinking as foundational for “anticipatory competence” and “systems thinking” required for navigating sustainability challenges (Cohen, 1988).

4.2.2. Cognitive skills as transformative competencies

Recent scholarship distinguishes between functional digital literacy (technical proficiency) and transformative digital literacy (critical-creative engagement enabling societal change) (Cervi et al., 2024; Vare et al., 2023). Our findings suggest that critical and creative thinking serve as catalysts transforming functional digital skills into transformative digital ecoliteracy. Students possessing strong cognitive skills don't merely use digital tools; they critically interrogate digital environmental information, creatively repurpose technologies for sustainability advocacy, and engage in informed environmental decision-making (Tomczyk et al., 2023; Redecker, 2017).

4.2.3. Implications for curriculum design

International frameworks increasingly advocate for competency-based, interdisciplinary approaches integrating digital literacy with sustainability education (Cohen, 1988; UNESCO, 2024). Our empirical evidence supports this integration by demonstrating that cognitive competencies bridge these domains. Curriculum designers should therefore move beyond siloed instruction teaching digital skills in computer science, critical thinking in philosophy, environmental content in science toward integrated learning experiences simultaneously cultivating multiple competencies (Liao et al., 2023; Vare et al., 2023).

The European Digital Competence Framework for Educators (DigCompEdu 2.2, updated 2024) now explicitly includes “facilitating learners‘ digital and ecological competence” as a core educator competency (Redecker, 2017). Our findings validate this framework evolution by demonstrating that student digital ecoliteracy depends not only on individual cognitive abilities but also as multilevel research would reveal on educators' capacities to scaffold integrated skill development (Caena and Redecker, 2019).

5 Limitations and future research directions

5.1. Methodological limitations

This study's exclusive reliance on quantitative methodology, while enabling robust statistical analysis of predictive relationships (R2 = 0.72–0.75), presents significant limitations in understanding how and why critical and creative thinking enhance digital ecoliteracy. Cross-sectional correlational designs demonstrate associations but cannot illuminate underlying cognitive, metacognitive, or social processes mediating these effects (Creswell and Plano Clark, 2018; Greene, 2007). Critical questions remain unanswered: How do students actually deploy critical thinking when evaluating environmental websites? What metacognitive strategies differentiate high from low performers? These process-oriented questions require methodological approaches beyond numerical measurement (Scherer et al., 2019).

Quantitative surveys reduce complex educational phenomena to aggregate scores, obscuring instructional contexts, pedagogical practices, and institutional cultures shaping digital ecoliteracy development (Hatlevik et al., 2018; Tondeur et al., 2017). The cross-sectional design prevents examining how cognitive skills and digital ecoliteracy co-develop over time. Longitudinal designs tracking students across their university careers would illuminate developmental trajectories and optimal intervention timing (Fraillon et al., 2020; Siddiq et al., 2017).

Future research should integrate mixed-methods approaches: think-aloud protocols revealing real-time cognitive processes (Ericsson and Simon, 1993), semi-structured interviews exploring enabling factors (Patton, 2015), classroom ethnography documenting pedagogical facilitation (Merriam and Tisdell, 2016), and digital artifact analysis examining student work for evidence of critical evaluation and creative application (Pink et al., 2016).

Emerging methodological innovations offer additional promising avenues. Recent advances in learning analytics enable fine-grained tracking of students' digital environmental engagement patterns, such as search strategies, source evaluation behaviors, and tool usage providing behavioral data complementing self-reports (Scherer et al., 2023). Eye-tracking studies examining visual attention during evaluation of environmental websites could reveal cognitive processes underlying critical assessment (McGrew et al., 2019). Experience sampling methods using mobile apps could capture real-time digital ecoliteracy practices in naturalistic contexts (Cervi et al., 2024).

Design-based research approaches testing pedagogical interventions iteratively across multiple cycles, would illuminate effective strategies for cultivating digital ecoliteracy while generating theoretical insights about learning mechanisms (Bakker, 2018; McKenney and Reeves, 2019). Such approaches align with calls for “engaged scholarship” bridging research and practice in sustainability education (Vare et al., 2023). Social network analysis could examine how digital ecoliteracy diffuses through peer networks, revealing whether students with strong cognitive skills serve as “hubs” influencing peers‘ digital environmental engagement (Liao et al., 2023). Computational text analysis of students' digital environmental communications (e.g., blog posts, social media advocacy) could provide unobtrusive measures of critical evaluation and creative application without relying solely on self-report (Scherer et al., 2023).

5.2. Omission of educator variables

A critical limitation is the absence of educator-level variables, despite substantial evidence that teachers serve as essential mediators between student cognitive skills and learning outcomes (Hattie, 2018). While findings demonstrate cognitive skills predict digital ecoliteracy at the student level, these relationships are facilitated—or constrained—by educators' digital competencies and pedagogical expertise. Educators who possess strong digital skills model critical evaluation of online environmental information, demonstrating source credibility assessment and distinguishing evidence-based science from misinformation (Breakstone et al., 2021; McGrew et al., 2019). They design authentic learning activities integrating digital tools with environmental content and provide scaffolding enabling progressive skill development (Koehler and Mishra, 2009; Redecker and Punie, 2017).

Research in Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) demonstrates that effective technology integration requires synthesizing content, pedagogical, and technological knowledge—a complex integration few teachers achieve without professional development (Mishra and Koehler, 2006; Voogt et al., 2013). Effective programs should address digital environmental competencies, pedagogical strategies for higher-order thinking, critical digital literacy, and assessment of integrated competencies (Caena and Redecker, 2019; Pedaste et al., 2015). Future studies should employ multilevel modeling to partition variance across student, instructor, and institutional levels (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002), revealing how educator competencies explain outcomes beyond individual cognitive skills.

5.3. Study strengths and recommendations

Despite limitations, this study addresses a timely topic at the intersection of cognitive development, digital literacy, and sustainability education (Liao et al., 2022; UNESCO, 2020). The novelty lies in empirically testing cognitive predictors across two independent samples, providing replication strengthening confidence (Makel and Plucker, 2014). Substantial effect sizes indicate fostering higher-order thinking represents a robust pathway for enhancing digital ecoliteracy, providing quantitative evidence supporting UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development and OECD Learning Compass 2030 (OECD, 2019).

Educators should design inquiry-based activities requiring critical evaluation from multiple sources, facilitate project-based challenges integrating analytical and creative skills, and model lateral reading strategies. Students should actively practice critical evaluation, experiment with diverse digital tools, and engage in citizen science. Institutions should invest in professional development, provide supporting infrastructure, and establish interdisciplinary communities of practice. Researchers should conduct mixed-methods studies, employ longitudinal designs, investigate educator variables as mediators, and examine cross-cultural generalizability.

6 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that critical and creative thinking significantly predict digital ecoliteracy among Indonesian university students, with critical thinking showing stronger effects (r = 0.58–0.76) than creative thinking (r = 0.31–0.71) across two independent samples. Critical thinking's dominance reflects its role in enabling students to evaluate environmental information sources, identify biases, and make evidence-based judgments competencies essential for navigating digital misinformation and “greenwashing” rhetoric. Creative thinking contributes complementary value by fostering innovative applications of digital tools and alternative problem-solving approaches. These findings align with UNESCO's Education for Sustainable Development and the OECD Learning Compass 2030, which position higher-order thinking and digital competencies as foundational for sustainability education. As digital technologies increasingly mediate environmental engagement, fostering both analytical rigor and creative innovation becomes imperative for preparing environmentally responsible digital citizens capable of contributing meaningfully to global sustainability goals.

7 Recommendations

1. Curriculum Integration – Embed critical and creative thinking into digital literacy and environmental education through project-based and interdisciplinary approaches.

2. Pedagogical Innovation – Use inquiry-based learning, debates, and collaborative problem-solving to strengthen analytical and creative skills for sustainability challenges.

3. Digital Competency Development – Provide structured training on digital tools (e.g., GIS, remote sensing, citizen science platforms) to enhance ecoliteracy.

4. Policy and Institutional Support – Recognize digital ecoliteracy as a key competence in national education frameworks and invest in infrastructure and faculty development.

5. Future Research – Conduct longitudinal and cross-cultural studies to examine the long-term impact of critical and creative thinking on digital ecoliteracy.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/supplementary material.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Riau, and Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, Universitas Riau. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants.

Author contributions

SH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YY: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – original draft. RW: Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by LPPM Universitas Riau Indonesia under the scheme of DRTPM KEMDIKTISAINTEK with the Grant Number: 20684/UN19.5.1.3/AL.04/2024.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Altieri, M. A. (2018). Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture, 2nd edn. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. doi: 10.1201/9780429495465

Bakker, A. (2018). Design Research in Education: A Practical Guide for Early Career Researchers. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203701010

Beghetto, R. A. (2021). Creative Thinking in Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. Abingdon: Routledge.

Breakstone, J., Smith, M., Wineburg, S., Rapaport, A., Carle, J., Garland, M., et al. (2021). Students' civic online reasoning: a national portrait. Educ. Res. 50, 505–515. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211017495

Caena, F., and Redecker, C. (2019). Aligning teacher competence frameworks to 21st century challenges: the case for the European Digital Competence Framework for Educators (DigCompEdu). Eur. J. Educ. 54, 356–369. doi: 10.1111/ejed.12345

Capra, F. (2007). The Science of Leonardo: Inside the Mind of the Great Genius of the Renaissance. New York, NY: Doubleday.

Cervi, L., Pérez Tornero, J. M., and Tejedor, S. (2024). Digital ecoliteracy and environmental communication in the post-pandemic era: a systematic review. Sustainability 16:1247.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd Edn. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. doi: 10.4324/9780203771587

Cojocariu, V-. M., and Boghian, I. (2024). A literature review on digital creativity in higher education: toward a conceptual model. Educ. Sci. 14:1189. doi: 10.3390/educsci14111189

Creswell, J. W., and Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

d'Escoffier, L. N., Guerra, A., and Braga, M. (2024). Problem-based learning and engineering education for sustainability: where we are and where could we go? J. Problem Based Learn. Higher Educ. 12, 18–45. doi: 10.54337/ojs.jpblhe.v12i1.7799

Dewiyana, H., Muda, I., and Silalahi, A. S. (2023). Digital literacy, technological literacy, and ecological literacy as predictors of attitudes towards ICT G-readiness [As recommendation to the drafting of the personal data protection law (PDP)]. Russian Law J. 11, 811–830.

Ennis, R. H. (2018). Critical thinking across the curriculum: a vision. Topoi 37, 165–184. doi: 10.1007/s11245-016-9401-4

Ericsson, K. A., and Simon, H. A. (1993). Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data, Rev. edn. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. doi: 10.7551/mitpress/5657.001.0001

Facione, P. A. (2020). Critical Thinking: What it is and why it Counts. Millbrae, CA: Insight Assessment.

Fraillon, J., Ainley, J., Schulz, W., Friedman, T., and Duckworth, D. (2020). Preparing for Life in a Digital World: IEA International Computer and Information Literacy Study 2018 International Report. Cham: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-38781-5

Ghanizadeh, A. (2017). The interplay between critical thinking, creative thinking, and emotional intelligence in higher education. Thinking Skills Creat. 23, 44–55.

Golden, B. (2023). The Power of Critical Thinking for Learners. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hajj-Hassan, M., Chaker, R., and Cederqvist, A-. M. (2024). Environmental education: a systematic review on the use of digital tools for fostering sustainability awareness. Sustainability 16:3733. doi: 10.3390/su16093733

Hatlevik, O. E., Throndsen, I., Loi, M., and Gudmundsdottir, G. B. (2018). Students' ICT self-efficacy and computer and information literacy: determinants and relationships. Comp. Educ. 118, 107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.11.011

Hattie, J. (2018). Visible Learning: The Sequel. A Synthesis of Over 1,600 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kaufman, J. C., and Beghetto, R. A. (2014). In praise of Clark Kent: creative metacognition and the importance of teaching kids when (not) to be creative. Roeper Rev. 35, 155–165. doi: 10.1080/02783193.2013.799413

Kesici, A. (2022). The effect of digital literacy on creative thinking disposition: the mediating role of lifelong learning. Thinking Skills Creat. 44:101052. doi: 10.53850/joltida.1063509

Koehler, M. J., and Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge? Contemp. Issues Technol. Teacher Educ. 9, 60–70.

Koltay, T. (2011). The media and the literacies: media literacy, information literacy, digital literacy. Media Cult. Soc. 33, 211–221. doi: 10.1177/0163443710393382

Kong, S. C. (2014). Developing information literacy and critical thinking skills through domain knowledge learning in digital classrooms: an experience of practicing flipped classroom strategy. Comp. Educ. 78, 160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.05.009

Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical Thinking: A Literature Review. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Research Report.

Lee, E., and Hannafin, M. J. (2016). A design framework for enhancing engagement in student-centered learning: own it, learn it, and share it. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 64, 707–734. doi: 10.1007/s11423-015-9422-5

Liao, Y. K. C., Chang, H. W., and Chen, Y. W. (2022). Effects of computer programming on cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysis. J. Educ. Comp. Res. 60, 251–282.

Liao, Y. K. C., Chang, H. W., and Chen, Y. W. (2023). Meta-analysis of digital competence and higher-order thinking: implications for 21st-century learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 71, 487–512.

Lo Iacono, L., Valastro, A. L., and Veneziano, E. P. (2024). Testing the effectiveness of an ecomedia-literacy lesson: fostering pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Soc. Sci. 13:645. doi: 10.3390/socsci13120645

Makel, M. C., and Plucker, J. A. (2014). Facts are more important than novelty: replication in the educational sciences. Educ. Res. 43:304–316. doi: 10.3102/0013189X14545513

McGrew, S., Breakstone, J., Ortega, T., Smith, M., and Wineburg, S. (2019). Can students evaluate online sources? Learning from assessments of civic online reasoning. Theory Res. Soc. Educ. 46, 165–193. doi: 10.1080/00933104.2017.1416320

McGuinness, C., and Fulton, C. (2019). Digital literacy in higher education: a case study of student engagement with e-tutorials using blended learning. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innovations Pract. 18, 1–28. doi: 10.28945/4190

McKenney, S., and Reeves, T. C. (2019). Conducting Educational Design Research, 2nd edn. Abingdon: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781315105642

Meirbekov, B. (2022). Digital literacy and higher-order thinking skills: correlational perspectives in university learning. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 17, 145–158.

Merriam, S. B., and Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation, 4th edn. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mishra, P., and Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. College Record 108, 1017–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Mogias, A., Boubonari, T., Realdon, G., Previati, M., Mokos, M., Koulouri, P., et al. (2019). Evaluating ocean literacy of elementary school students: preliminary results of a cross-cultural study in the Mediterranean region. Front. Marine Sci. 6:396. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2019.00396

Ng, W. (2012). Can we teach digital natives digital literacy? Comp. Educ. 59, 1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.016

OECD (2023). Education and Innovation for the Digital and Green Transitions: How Higher Education Can Support Effective Curriculum Development in Schools (Education Policy Perspectives No. 81). OECD Publishing. Available online at: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/11/education-and-innovation-for-the-digital-and-green-transitions-how-higher-education-can-support-teachers-and-school-leaders_6b45614c/6407e9f4-en.pdf (Accessed August 1, 2025).

Pangrazio, L., and Sefton-Green, J. (2021). Digital Media and Literacies: Learning in an Age of Digital Participation. Abingdon: Routledge.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative Research Evaluation Methods: Integrating Theory and Practice, 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Paul, R., and Elder, L. (2019). The Miniature Guide to Critical Thinking Concepts and Tools, 8th edn. Dillon Beach, CA: Foundation for Critical Thinking. doi: 10.5771/9781538133842

Pedaste, M., Mäeots, M., Siiman, L. A., de Jong, T., van Riesen, T., Kamp, E. T., et al. (2015). Phases of inquiry-based learning: definitions and the inquiry cycle. Educ. Res. Rev. 14, 47–61. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2015.02.003

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., Tacchi, J., et al. (2016). Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Raudenbush, S. W., and Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods, 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Redecker, C. (2017). European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu, ed. Y. Punie. Publications Office of the European Union. doi: 10.2760/178382

Redecker, C., and Punie, Y. (2017). European Framework for the Digital Competence of Educators: DigCompEdu. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Rieckmann, M. (2018). “Learning to transform the world: key competencies in education for sustainable development,” in Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development, eds. A. Leicht, J. Heiss, and W. J. Byun (Paris: UNESCO Publishing), 39–59.

Rizal, M., Hidayat, R., and Supriyanto, A. (2023). Creative thinking skills in digital learning: a case study in Indonesian universities. Int. J. Instruction 16, 251–270.

Runco, M. A., and Acar, S. (2019). Divergent thinking as an indicator of creative potential. Creat. Res. J. 26, 66–75. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2012.652929

Saavedra, A. R., and Opfer, V. D. (2019). Learning 21st-Century Skills Requires 21st-Century Teaching. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

Scherer, R., Howard, S. K., Tondeur, J., and Siddiq, F. (2023). Synthesizing research on teachers' technology integration: a meta-aggregation of qualitative evidence. Comp. Educ. 201:104832.

Scherer, R., Siddiq, F., and Tondeur, J. (2019). The technology acceptance model (TAM): a meta-analytic structural equation modeling approach to explaining teachers' adoption of digital technology in education. Comp. Educ. 128, 13–35. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.09.009

Siddiq, F., Gochyyev, P., and Wilson, M. (2017). Learning in digital networks - ICT literacy: a novel assessment of students' 21st century skills. Comp. Educ. 109, 11–37. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.01.014

Siddiq, F., Scherer, D., and Tondeur, J. (2016). The role of digital competence in students' learning outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Comput. Educ. 94, 36–55. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2015.11.001

Sternberg, R. J. (2012). The assessment of creativity: an investment-based approach. Creat. Res. J.24, 3–12. doi: 10.1080/10400419.2012.652925

Tang, C. M., and Chaw, L. Y. (2016). Digital literacy: a prerequisite for effective learning in a blended learning environment? Electron. J. e-Learning, 14, 54–65.

Thomas, J. W. (2020). A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning. Novato, CA: Buck Institute for Education.

Thornhill-Miller, B., Camarda, A., Mercier, M., Burkhardt, J-. M., Morisseau, T., Bourgeois-Bougrine, S., et al. (2023). Creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration: assessment, certification, and promotion of 21st-century skills for the future of work and education. J. Intell. 11:54. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence11030054

Tilbury, D. (2011). Education for Sustainable Development: an Expert Review of Processes and Learning. Paris: UNESCO.

Tomczyk, L., Fedeli, L., Wloch, A., Limone, P., Frania, M., Guarini, P., et al. (2023). Digital competences of pre service teachers in Italy and Poland. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 28:651–681. doi: 10.1007/s10758-022-09626-6

Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., Ertmer, P. A., and Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2017). Understanding the relationship between teachers' pedagogical beliefs and technology use in education: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 65, 555–575. doi: 10.1007/s11423-016-9481-2

Trilling, B., and Fadel, C. (2009). 21st Century Skills: Learning for Life in Our Times. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

UNESCO (2020). Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap. UNESCO Publishing. doi: 10.54675/YFRE1448

UNESCO (2021). Reimagining our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education. Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

UNESCO (2024). Digital Learning Week 2024: Concept Note - Education at the Intersection of the Digital and Greening Transitions. UNESCO. Available online at: https://www.unesco.org/sites/default/files/medias/fichiers/2024/04/digital-learning-week-2024-concept-note.pdf (Accessed August 3, 2025).

Ural, E., and Dadli, G. (2020). The effect of problem-based learning on 7th-grade students' environmental knowledge, attitudes, and reflective thinking skills in environmental education. J. Educ. Sci. Environ. Health 6, 177–192. doi: 10.21891/jeseh.705145

Vare, P., Arro, G., Hamer, d. e., Del Gobbo, A., de Vries, G., Farioli, G., et al. (2023). Devising a competence-based training program for educators of sustainable development: lessons learned. Sustainability 15:3633.

Vesala, T., Pál, Á., and Kóris, R. (2024). Fostering sustainability competences through co-creation of digital storytelling: effects of COVID-19 on higher education students' reflective learning. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 21:4. doi: 10.53761/3va1xt56

Voogt, J., Fisser, P., Pareja Roblin, N., Tondeur, J., and van Braak, J. (2013). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a review of the literature. J. Comp. Assist. Learn. 29, 109–121. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2012.00487.x

Voogt, J., and Roblin, N. P. (2012). A comparative analysis of international frameworks for 21st century competences: implications for national curriculum policies. J. Curriculum Stud. 44, 299–321. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2012.668938

Wahyuni, R., Purnomo, E., and Astuti, T. (2023). Enhancing critical thinking skills through sustainability-oriented STEM education. J. Sci. Educ. Res. 14, 166–178.

Keywords: correlation, creative thinking, critical thinking, digital ecoliteracy, higher-order thinking, regression analysis

Citation: Hasibuan S, Yustina Y and Wahyuni R (2025) Bridging cognitive skills and environmental awareness: critical and creative thinking as predictors of digital ecoliteracy. Front. Educ. 10:1705676. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1705676

Received: 15 September 2025; Revised: 18 October 2025;

Accepted: 17 November 2025; Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Rawad Chaker, Lumière University Lyon 2, FranceReviewed by:

Carla Morais, University of Porto, PortugalAminah Zuhriyah, STKIP Kusuma Negara, Indonesia

Copyright © 2025 Hasibuan, Yustina and Wahyuni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saberina Hasibuan, c2FiZXJpbmEuaGFzaWJ1YW5AbGVjdHVyZXIudW5yaS5hYy5pZA==

Saberina Hasibuan

Saberina Hasibuan Yustina Yustina

Yustina Yustina Resma Wahyuni

Resma Wahyuni