- Department of Child Development, Faculty of Health Sciences, Iğdır University Iğdır, Iğdır, Türkiye

In this study, which employed creative drama as a teaching method, was carried out with the participation of 36 first-year students enrolled in the elective course Communication Skills in the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics during the fall semester of the 2024–2025 academic year. A mixed-methods design was employed in the study. In the quantitative dimension, a single-group experimental design without a control group was used, while the qualitative data were collected through interviews. The analysis techniques applied to the dependent and independent variables in the study were: A t-test for dependent samples, a t-test for independent samples, and an ANOVA analysis. Qualitative data obtained from the interview questions posed at the end of the study were analyzed. Students’ responses were coded, and similar codes were aggregated to form themes. The findings were presented in tables and figures. At the end of the study, it was observed that the students developed greater awareness of communication, acquired strategies for resolving conflicts, and showed improvements in personal attributes such as self-confidence, self-awareness, and self-expression. Throughout the process, the students were energetic, actively engaged in the activities, and eager to participate in the lessons. The activities contributed to the enhancement of their communication skills, self-confidence, and social interactions. Additionally, students reported that they demonstrated increased respect for others’ opinions and made efforts to behave more impartially.

1 Introduction

Humans, as inherently social beings, begin cultivating the ability to form relationships from early childhood, first within the family and subsequently in school and the broader social environment. Effective communication is a fundamental skill that supports an individual’s social development (Mutlaq, 2023). Communication skills are essential abilities that enable individuals to interact effectively with others. These skills include expressing self-expression, asking questions, speaking, listening, forming friendships, respecting the rights of others, advocating for one’s own rights, showing appreciation, and addressing individuals by their names. Importantly, these skills can be developed and enhanced through education (Lavasani et al., 2011). These abilities constitute fundamental skills that support interaction with people and other living beings. They promote self-expression, the continuity of relationships, and respect for others in interpersonal contexts. Strong communication skills are associated with high levels of personal and professional success (Martin and Nakayama, 2013). Therefore, fostering communication skills is crucial to maintaining the wellbeing of society. Individuals who express themselves accurately are more likely to develop effective communication competencies and establish healthy relationships (Akkaya, 2018). Effective communication skills facilitate interactions in all types of human relationships and across all professional fields (Gökçearslan Çifci and Altinova, 2017). Communication skills are fundamental for personal development, social integration and effective participation in different social environments (Reith-Hall and Montgomery, 2023). Moreover, the workforce increasingly requires highly skilled employees who face more complex and interactive tasks. These employees are expected not only to possess a high level of knowledge but also to efficiently select and apply this knowledge effectively in both their professional and personal lives (Van Laar et al., 2017). Relationships and interactions among people are considered the foundation of communication. Throughout their lives, individuals engage in communication with their environment. The term “communication,” derived from the Latin word communis, signifies commonality, togetherness, and socialization (Kardaş, 2023). Because communication is not only a linguistic process but also a social and experiential phenomenon, educational approaches that incorporate active interaction and collaboration are crucial in teaching this concept. From this perspective, creative drama is one of the most effective methods that directly engages participants in communicative and social practices. As a teaching method, creative drama can be applied across nearly all fields of instruction and is particularly integrative within the domain of art education. It is emphasized that art education primarily involves the training of the senses, and that creative drama, as a form of art education, provides sensory training that spans all age groups, from early childhood to adulthood (Üstündağ, 2006). Drama, which fosters critical thinking and active participation, plays a significant role in the development of self-confidence and self-expression when integrated into education (Gönen and Dalkılıç, 2003). Although drama is essentially a social art, it also serves as an important educational tool within instructional methodology, creating a dramatic environment in which students learn by role-playing and employing other dramatic techniques related to the subject matter (Heathcote et al., 1984; Türkan and Dinç, 2020). The general objectives of drama align closely with communication skills, and therefore, participants in groups where the drama method is implemented also experience improvements in their communication abilities (Adıgüzel, 2013). Drama encompasses various techniques, including improvisation, role playing, simulation, skits, hot chair, corridor of consciousness, and pantomime. Role playing is the enactment of an idea, situation, problem, or event by an entire group or a select few on stage. In role playing, the participant portrays a different person or performance, aiming to teach a strategy or develop a skill or ability (empathy, communication, etc.). If a participant is hesitant to speak as themselves in front of group, they can more easily speak in the role of someone else through different techniques. Acting out the personality of others and thinking like others helps students develop more positive behavioral patterns (Kesici, 2014; Ulubey and Gözütok, 2015). Through individual or group activities employing diverse techniques, drama contributes to the development of empathy, experiential learning, self-recognition and self-discovery, as well as socialization. Traditional teaching methods characterized by teacher-centered lectures and passive student participation have been criticized for limiting student engagement, critical thinking, and active learning opportunities (Freeman et al., 2014; Prince, 2004). In response to these limitations, interactive and student-centered strategies have been increasingly emphasized because they foster collaboration, problem-solving, and effective communication skills (Bonwell and Eison, 1991; Weimer, 2013). Recent studies further emphasize the importance of such approaches: Kerimbayev et al. (2023) show that student-centered learning integrated with modern technologies improves engagement and learning outcomes in distance education (Kerimbayev et al., 2023). Furthermore, creative drama has been shown to enhance social interaction, communication competence, and creative self-efficacy (Arda Tuncdemir, 2025; Eyüp, 2023). Specifically, these participatory methods, including role-playing and experiential activities, address the limitations of traditional pedagogy by actively engaging students and fostering higher-order thinking and interpersonal skills (Heathcote et al., 1984; Michael, 2006). Overall, these findings highlight the critical role of interactive, student-centered teaching methods in supporting both communication skills and social-emotional development. These contributions play a crucial role in enhancing communication skills (Erdem, 2021).

Inspired by theater pedagogy, these practices are well received by nutrition and dietetics students; techniques such as case scenarios, role-playing, and forum theater support both professional and personal development. Research indicates that such drama-based approaches enable students to better understand clients’ perspectives, foster empathy and self-awareness, and develop effective communication skills. Therefore, drama-based education can be regarded as a powerful complementary method within nutrition and dietetics programs (Aslan, 2018).

Nutrition and dietetics is one of the professions in which human relations are experienced intensively. The communication established between the dietician and the patient is closely related to interpersonal skills such as empathy, recognizing emotions, and effectively conveying messages to ensure patients’ full understanding and to provide appropriate support. The drama method represents an effective instructional approach for students in the health sciences. Nutrition and dietetics students, by participating in drama-based activities within the course Effective Communication Techniques, actively engage in experiential learning to develop essential professional competencies such as communication, empathy, ethical decision-making, and counseling. This approach is grounded in Kolb and Fry’s experiential learning model, whereby students role-play real-life scenarios, strengthen their ability to build empathetic connections, and achieve meaningful learning through their own experiences (Hobson et al., 2019). Addressing the need to foster new skills in the Communication Skills course implies, at least in part, moving away from traditional teaching practices such as lecture-based methods and content-centered applications. Such approaches often fail to promote competencies like critical thinking, as they encourage rote learning in which students’ primary role is to memorize what the teacher provides. Consequently, students lack the challenging environment necessary to construct new knowledge and develop essential skills, thereby limiting their capacity for critical thinking. One of the methods used to enhance communication skills is creative drama. Numerous studies have examined the relationship between creative drama and communication skills across different age groups and educational levels (Afacan and Turan, 2012; Altınova, 2006; Arslan et al., 2010; Dere, 2019; Dikici et al., 2003; Erkan, 2005; Gökçearslan Çifci and Altinova, 2017; Karateke, 2006; Kılıç, 2012; Mantione and Smead, 2003; McNaughton, 2004; Okvuran, 1993; Rances, 2005; Saçlı, 2013; Tanrıseven and Aykaç, 2013; Wardrope, 2002; Yayla and Ömeroğlu, 2005).

1.1 The purpose of the research

The aim of this study is to examine the effects of using creative drama as an instructional approach on students’ communication skills. Specifically, the study seeks to determine whether creative drama activities contribute to students’ development of communication awareness, self-recognition and self-expression skills, enrichment of social relationships, and the adoption of attitudes within the framework of democratic values.

1.2 The importance of the research

This research is significant in that it examines the effects of the creative drama method on communication and personal development in higher education, supported by a qualitative approach. Creative drama is gaining increasing importance in the literature as an innovative teaching method that develops students’ self-confidence, self-expression, empathy, problem-solving and social interaction skills. Communication skills, professional competence, and values education play a critical role in the health sciences, as graduate students must establish effective communication with patients, clients, and colleagues in their professional lives. In this context, the research:

1. Demonstrates the concrete contribution of creative drama applications to the personal and professional development of university students,

2. Emphasizes the importance of social skills such as socialization, cooperation and democratic values in education,

3. Guides educators in terms of demonstrating the applicability and effective use of the creative drama method in teaching processes,

4. Sheds light on the program development and lesson planning process for the creative drama method in future health education and communication courses.

Therefore, this research aims to contribute to educational practices and scientifically prove the effects of the creative drama method on developing communication skills in university students.

1.3 Research questions

1. Is there a statistically significant difference between the pre-test and post-test communication skills scores of the participants in the study group, and what is the magnitude of this effect?

2. Do the pre-test and post-test communication skills scores of the participants in the study group differ significantly according to gender?

3. To what extent do the participants’ perceived skill levels influence their overall performance scores before and after the drama-based communication skills activities?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Research design

In the sequential explanatory design, one of the mixed research methods, quantitative data collection tools are used first, followed by qualitative data collection tools (Karasar, 2011). A mixed method is a research design or methodology used to collect, analyze, and mix quantitative and qualitative data across a single study or series of studies for the purpose of better understanding research problems (Creswell, 2009; Patton, 2002). The one-group quasi-experimental design was selected for this study because it allows researchers to examine the effects of an intervention within a single group when random assignment or the inclusion of a control group is not feasible. This design is particularly appropriate in educational and health-related settings where ethical, practical, or administrative constraints prevent the use of randomized controlled trials. It enables the evaluation of pre- and post-intervention changes, providing valuable insights into the potential impact of the applied program or treatment on the participants. Although this design has limitations regarding internal validity, it remains a widely accepted approach for preliminary or field-based studies aiming to assess intervention effectiveness in real-world contexts (Campbell and Stanley, 2015; Creswell, 2009; Harris et al., 2006). This study, which examines whether the creative drama training received by students in their communication course has an effect on participants’ communication skills, is structured using a mixed design. The quantitative dimension of the research was designed using a pre-test-post-test single-group quasi-experimental design, while the qualitative dimension was designed using semi-structured interviews at the end of the research. The students’ views on the development of their communication skills as a result of creative drama training were obtained.

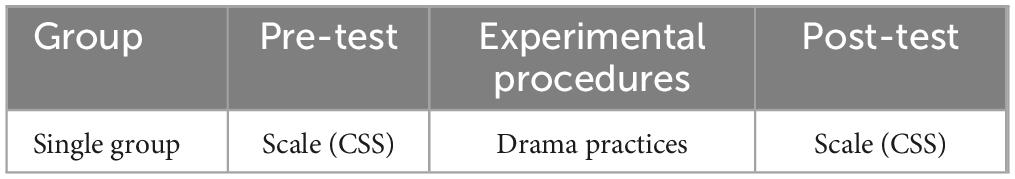

The drama applications prepared by the researcher were determined as the independent variable, while communication skills were determined as the dependent variable. For this reason, the study began with a pre-test involving a single group of volunteer participants. Drama activities were conducted with the group during a 12 week communication skills course. A post-test was administered to the group after the drama activities. Following these activities, analyses were conducted and the data were interpreted. A symbolic representation of the design created within the scope of the study is presented in Table 1.

2.2 Research group

The sample used in this study was determined through purposive sampling. Research is defined as “an economical method that minimizes the waste of labor, time, and money,” emphasizing efficiency and accessibility. In this study, the research group was described as a cohort identified through shared contact information. Being a group that takes the same course and gathers for a common purpose ensures both the organizational and economic feasibility of the study (Fraenkel and Wallen, 1990). The study was conducted with voluntary participants, consisting of 36 university students. The study group comprised first-year students from the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, including 26 female students (%72.2) and 10 male students (% 27.7).

2.3 Data collection instruments

The purpose of this study was to examine the effects of integrating drama-based activities into the Communication Skills course on university students’ communication abilities. To achieve this aim, the Communication Skills Scale (CSS) was selected as the primary data collection instrument.

Communication Skills Scale (CSS): Developed by Owen and Bugay (2014) to measure university students’ communication skills, the Communication Skills Scale (CSS) is a 5-point Likert-type measurement tool consisting of 25 items and has four factors. These four factors are named “Communication Principles and Basic Skills (CPBF),” “Self-Expression (SE),” “Active Listening and Non-Verbal Communication (ALNC)” and “Willingness to Communicate (WTC).” The internal consistency reliability coefficient for the scale was calculated as 0.94. The Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient for the scale was 0.88, while the internal consistency coefficients for the factors were determined as 0.79 for CPBF, 0.72 for SE, 0.64 for ALNC, and 0.71 for WTC. Higher scores on the scale indicate improved communication skills. The scale uses a rating scale ranging from “Never” to “Always,” with each question scored between 1 and 5. The total score on the scale ranges from a minimum of 25 to a maximum of 125 (Owen and Bugay, 2014).

Semi-Structured Interview Form: To develop the semi-structured interview form, a comprehensive review of the relevant literature was first conducted. Following the literature review, the researcher designed a semi-structured interview form. While preparing the interview questions, principles such as clarity, avoiding multidimensionality, and non-directiveness were taken into account (Bogdan and Biklen, 1997). The draft interview form was then submitted to field experts for evaluation regarding its usability, clarity, and applicability. Based on the feedback received from the experts, the final version of the interview form was prepared. The interview questions are presented below:

• What is the primary reason you want to improve your communication skills?

• Reflecting on your communication skills before participating in the activities implemented in this study, what overall benefits did engaging in the drama activities provide you throughout the process?

• How did you feel during the drama activities? In what ways did you find the process enjoyable, challenging, or thought-provoking?

• In what ways did participating in the drama activities affect your communication skills? Did you notice any changes in the way you interact with others?

• How did the drama activities influence your perspective toward people and events around you? Did you observe any changes in understanding yourself or others?

• How do you think the drama activities will impact your friendships, group work, and communication within your social environment?

2.4 Application

The drama training was conducted by the researcher with first-year students of the Department of Nutrition and Dietetics at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Iğdır University, in the classrooms of the Education Building. All necessary ethical and implementation permissions were obtained prior to the study. During the drama training sessions, attention was given to ensuring that all students actively participated. The researcher planned the drama activities based on a 12-week course schedule, with each week comprising 2 h of lessons, totaling 24 h of drama-based instruction within the Communication Skills course. The single designated group was informed about the study, the pre-test was administered, and the drama activities commenced. Following the 12-week implementation, the post-test was applied. The activities were designed to encourage students to assume various roles, analyze the actions associated with these roles, collaborate on assigned tasks, and share their emotions and thoughts experienced during the activities, with the aim of enhancing their communication skills. The instructional plans for the drama activities were developed considering relevant theses and studies in the literature. A sample lesson plan demonstrating teaching situations is provided in Supplementary Appendix 1.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Iğdır University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Committee (Approval No: E-37077861-900-152013). Additionally, written permission was obtained from the Rectorate of the university where the study was conducted. Participation was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all students.

2.5 Data analysis

All data collected from the participants were transferred to a digital environment and analyzed using the SPSS 23 software package. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted for the interpretation of the results. The analyses aimed to examine the effects of independent variables on the dependent variables. Accordingly, the statistical techniques applied to the dependent and independent variables included the paired-samples t-test, independent-samples t-test, and ANOVA. The analysis results are interpreted in the Findings section. Responses to the interview questions with students were recorded, then converted into common codes and grouped. The responses were subsequently tabulated and presented. To determine whether to use parametric or non-parametric tests, normality tests were conducted. Since the data met the assumptions of normality, parametric tests were applied. For the qualitative component of the study, content analysis was employed. During the analysis, meaningful statements were first extracted from students’ responses and coded. Similar codes were then grouped together to identify main themes for each question. The resulting themes and their frequencies were explained, and the findings were described accordingly.

3 Results

This section presents the analysis results of the data collected from participants during the pre-test and post-test measurements. The descriptive data related to the study are summarized in Table 2.

The mean pre-test score of the participants was 102.13, and the mean post-test score was 116.08, reflecting a 14-point improvement after the intervention. These findings indicate that the creative drama program effectively increased students’ communication skills, supporting the hypothesis that participation in drama-based activities enhances communication competence.

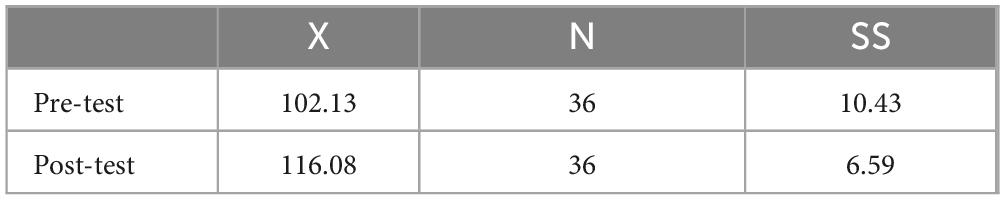

To answer the first research question regarding whether a significant difference exists between the pre-test and post-test scores and to determine the effect size, a paired-samples t-test was conducted. The results of this analysis are summarized in Table 3.

A paired-samples t-test was employed in the study to examine the impact of drama-based activities on the communication skills of university students. The results showed a significant difference between pre-test and post-test scores, t(35) = –10.553, p < 0.001, suggesting that participation in the drama program produced a statistically meaningful improvement in communication skills.

The effect size of the intervention was assessed using Cohen’s d. Following Cohen’s (1988) guidelines—where 0.2 denotes a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect, and 0.8 a large effect—the calculated value of d = 1.76 indicates a very large effect, highlighting the strong influence of the drama-based activities on students’ communication performance. These findings confirm that the implemented intervention substantially enhanced students’ communication competencies (Cohen, 1988; Lakens, 2013).

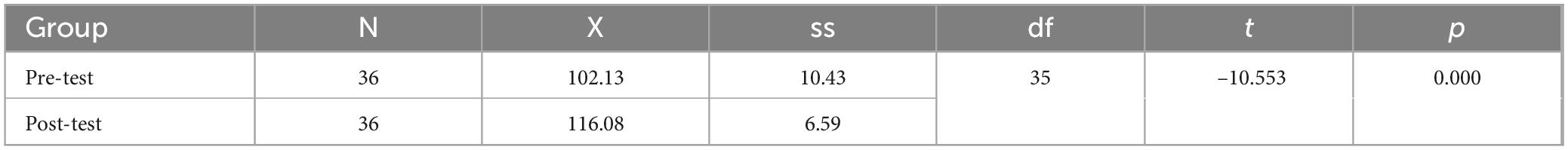

In order to assess whether gender influenced the study results, independent-samples t-tests were performed on the pre-test and post-test communication skills scores. The findings of these analyses are summarized in Table 4.

In this study, participants’ pre-test (total pre) and post-test (total post) scores were compared according to gender using independent-samples t-tests. For the pre-test scores, female participants ( = 104.73; SD = 8.35; n = 26) scored significantly higher than male participants ( = 95.40; SD = 12.64; n = 10). Levene’s test indicated that the variances of the groups were homogeneous (F = 2.123, p = 0.154). The independent-samples t-test confirmed that the difference in scores between females and males was statistically significant [t(34) = 2.59, p = 0.014]. Regarding post-test scores, female participants ( = 117.62; SD = 5.12) and male participants ( = 112.10; SD = 8.48) were analyzed. Levene’s test showed that the assumption of equal variances was violated (F = 7.733, p = 0.009), and therefore the “equal variances not assumed” result was considered. The t-test indicated that the gender difference in post-test scores was not statistically significant [t(11.62) = 1.93, p = 0.079]. Overall, when comparing pre-test and post-test scores by gender, no significant differences were observed in the post-test scores. Female students initially scored significantly higher than male students on the pre-test; however, the difference in post-test scores was not statistically significant. This suggests that male students showed greater improvement throughout the intervention. The initial gender difference observed at the pre-test diminished or disappeared by the end of the program.

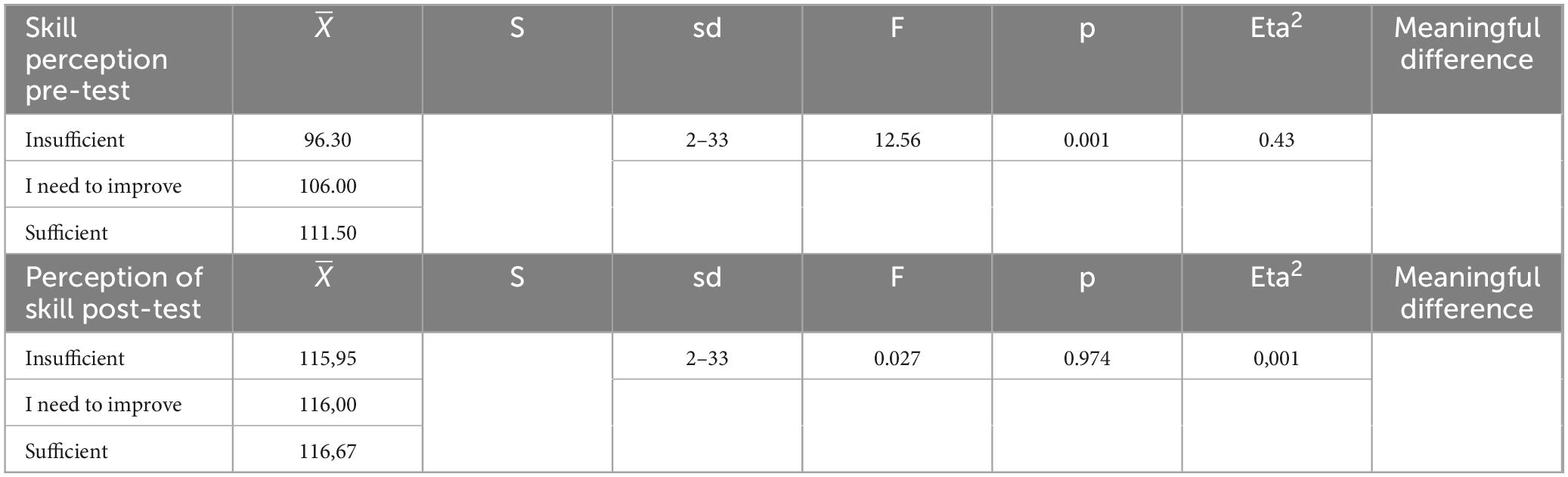

The study examined the relationship between students’ self-assessed skill levels (“insufficient,” “needs improvement,” and “sufficient”) and their total pre-test and post-test scores. A one-way ANOVA was performed, followed by Tukey HSD post hoc comparisons to identify significant differences between groups. The findings of these analyses are summarized in Table 5.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in pre-test scores based on students’ self-assessed skill levels, revealing a statistically significant effect, F(2, 33) = 12.56, p < 0.001. Post hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that participants who rated their skills as “insufficient” had significantly lower pre-test mean scores ( = 96.30) than those in the “needs improvement” ( = 106.00) and “sufficient” ( = 111.50) groups. No significant difference was observed between the “needs improvement” and “sufficient” groups (p = 0.314). These findings demonstrate that students with lower initial skill perception were disadvantaged in pre-test performance, while students with moderate or high skill perception exhibited similar baseline scores.

When examining post-test total scores according to students’ self-perceived skill levels, a one-way ANOVA revealed no significant differences, F(2, 33) = 0.03, p = .974. This finding indicates that after the intervention, students’ post-test performance did not vary based on their initial skill perception. Supporting this result, Tukey HSD post-hoc tests confirmed that the mean post-test scores for the “insufficient” ( = 0.95), “needs improvement” ( = 116.67), and “sufficient” ( = 116.00) groups fell within the same homogeneous subset, and the differences among them were not statistically significant (p = 0.971). These results suggest that following the intervention, students’ performance levels converged, reducing the initial differences in achievement. The findings indicate that variations in students’ initial skill perceptions were equalized over the course of the drama-based activities.

3.1 Analysis of the qualitative data

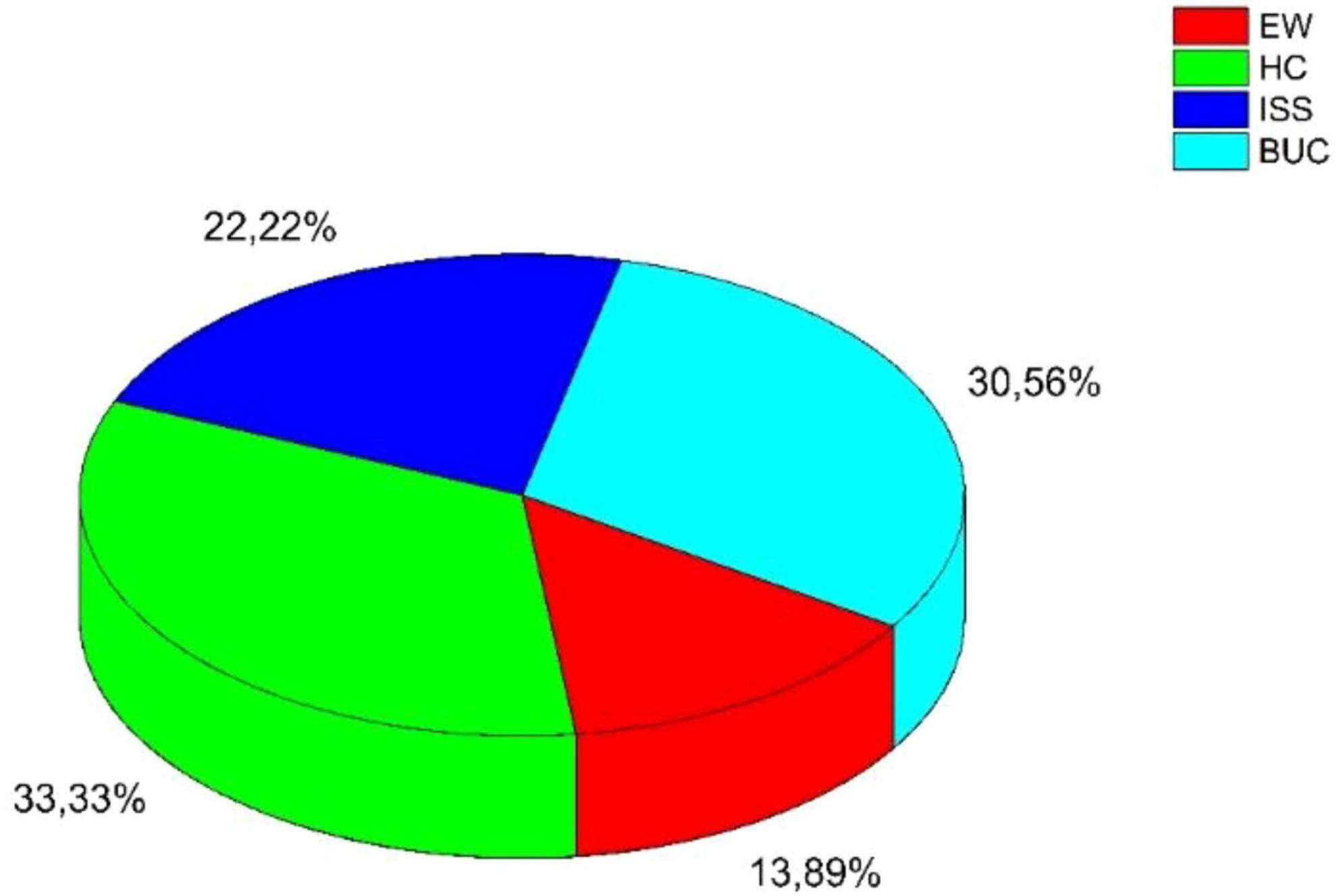

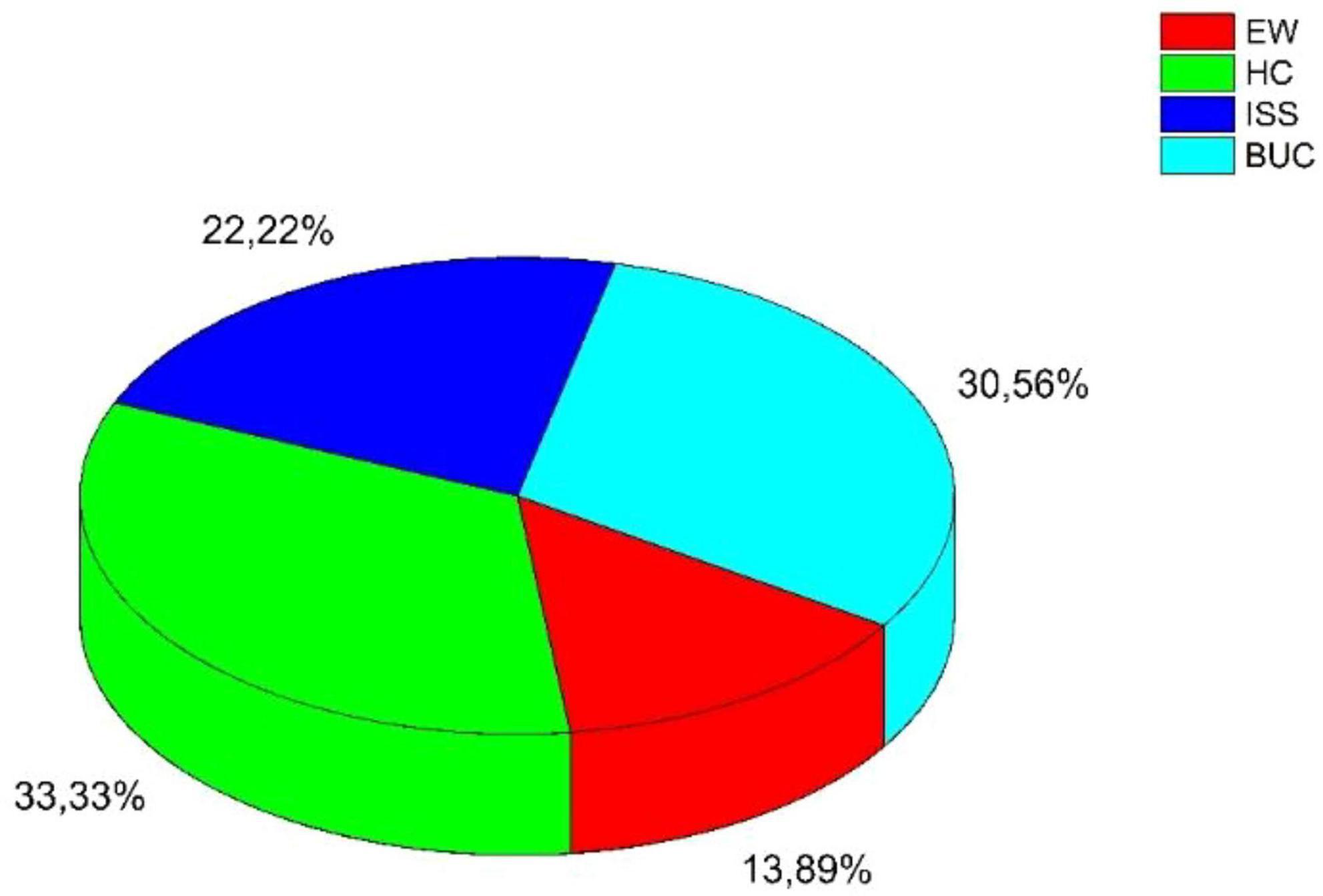

The students’ responses to the question, “What is the primary reason for your desire to improve your communication skills?,” were categorized into key themes and visually represented in a graph (Figure 1). The analysis revealed that students’ motivations encompassed both intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors included personal satisfaction, self-confidence, and a desire for self-improvement, reflecting students’ internal drive to enhance their communication abilities. Extrinsic factors involved academic achievement, professional development, and interpersonal relationships, highlighting the external benefits that students anticipated from improved communication skills. The distribution of responses showed that a majority of students emphasized intrinsic factors, particularly the enhancement of self-confidence and personal growth, while a substantial proportion also cited extrinsic benefits, such as better collaboration with peers and academic success. This finding suggests that the drama-based intervention not only addresses skill development but also aligns with students’ broader personal and social goals. As observed in Figure 1, the most frequently cited reason for students’ desire to improve their communication skills was “to support my career” (f = 12). This was followed by “to be correctly understood” (f = 11) and “to enhance my social skills” (f = 8). The least frequently mentioned reason was “to express myself well” (f = 5).

These findings indicate that students’ motivation to develop communication skills is primarily related to professional development and the need for accurate understanding, rather than purely personal expression.

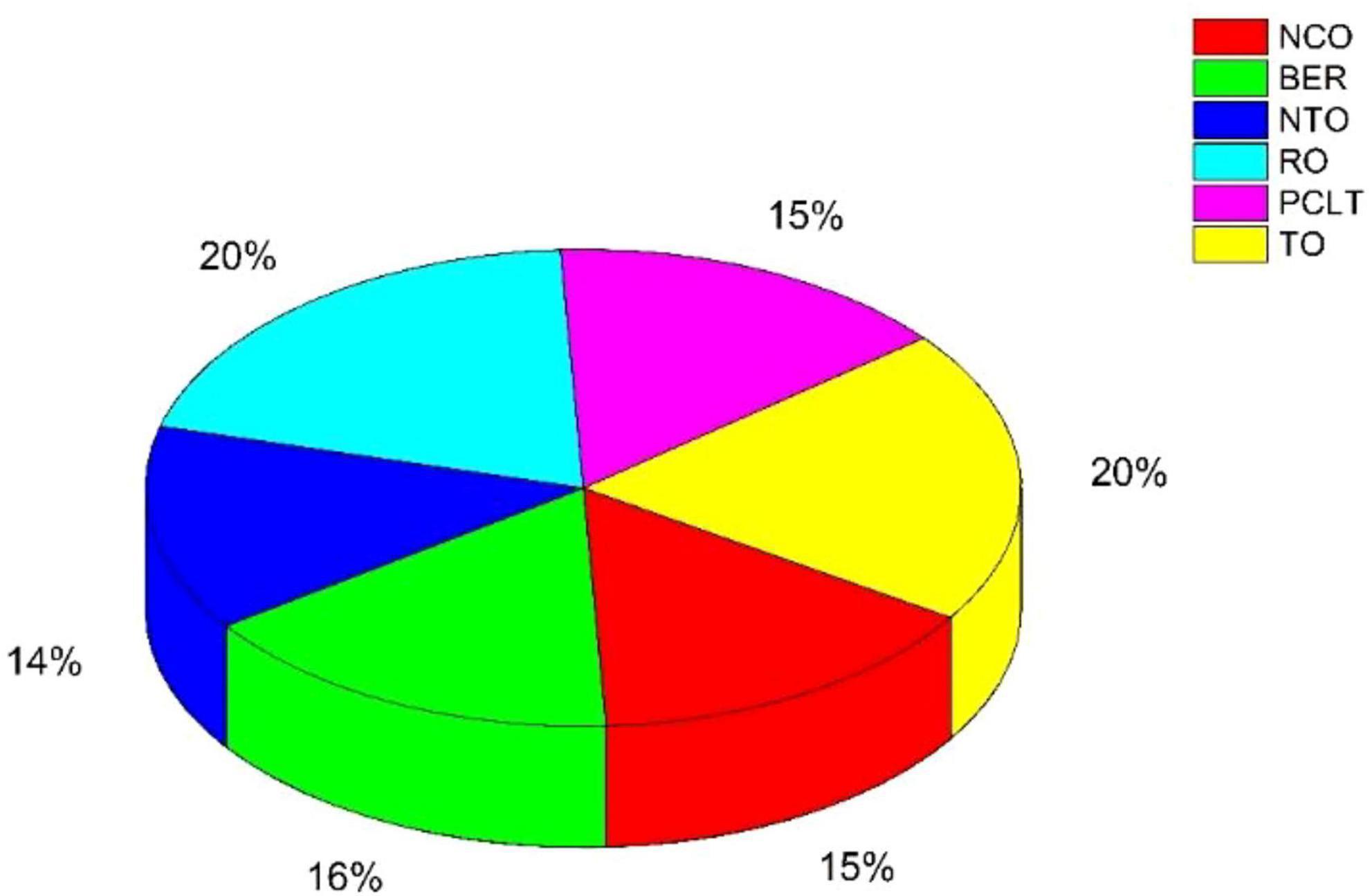

The data obtained from students’ responses to the question, “Considering your communication skills before participating in the activities conducted within the scope of this study, what did participating in the drama activities contribute to you throughout the process?,” are presented in Figure 2.

Examination of Figure 2 shows that the most frequently reported outcomes of the drama activities were improvements in “respecting others’ opinions” (f = 20) and “self-confidence” (f = 20). These results suggest that the drama-based intervention played a significant role in promoting students’ self-confidence and their capacity to acknowledge and appreciate differing viewpoints. Additionally, 16 students indicated that the drama activities enhanced their empathy skills. The responses also highlighted improvements in “caring for others” (f = 15) and “understanding the importance of communication in coexisting with others” (f = 15). In contrast, only 14 students emphasized the necessity of trusting others.

The data obtained from students’ responses to the question, “How did you feel during the drama activities?,” are presented in a graphical format (Figure 3).

As shown in Figure 3, the most frequently reported feeling during the drama activities was “feeling empathetic,” cited by 24 students. This was followed by “freely expressing oneself” (f = 20) and “feeling energetic” (f = 19). Additionally, 17 students reported experiencing the feeling of “being understood.” Although “volunteering willingly” (f = 13) and “patiently waiting” (f = 12) were less frequently mentioned, these findings indicate that the drama activities elicited a range of emotional experiences among students.

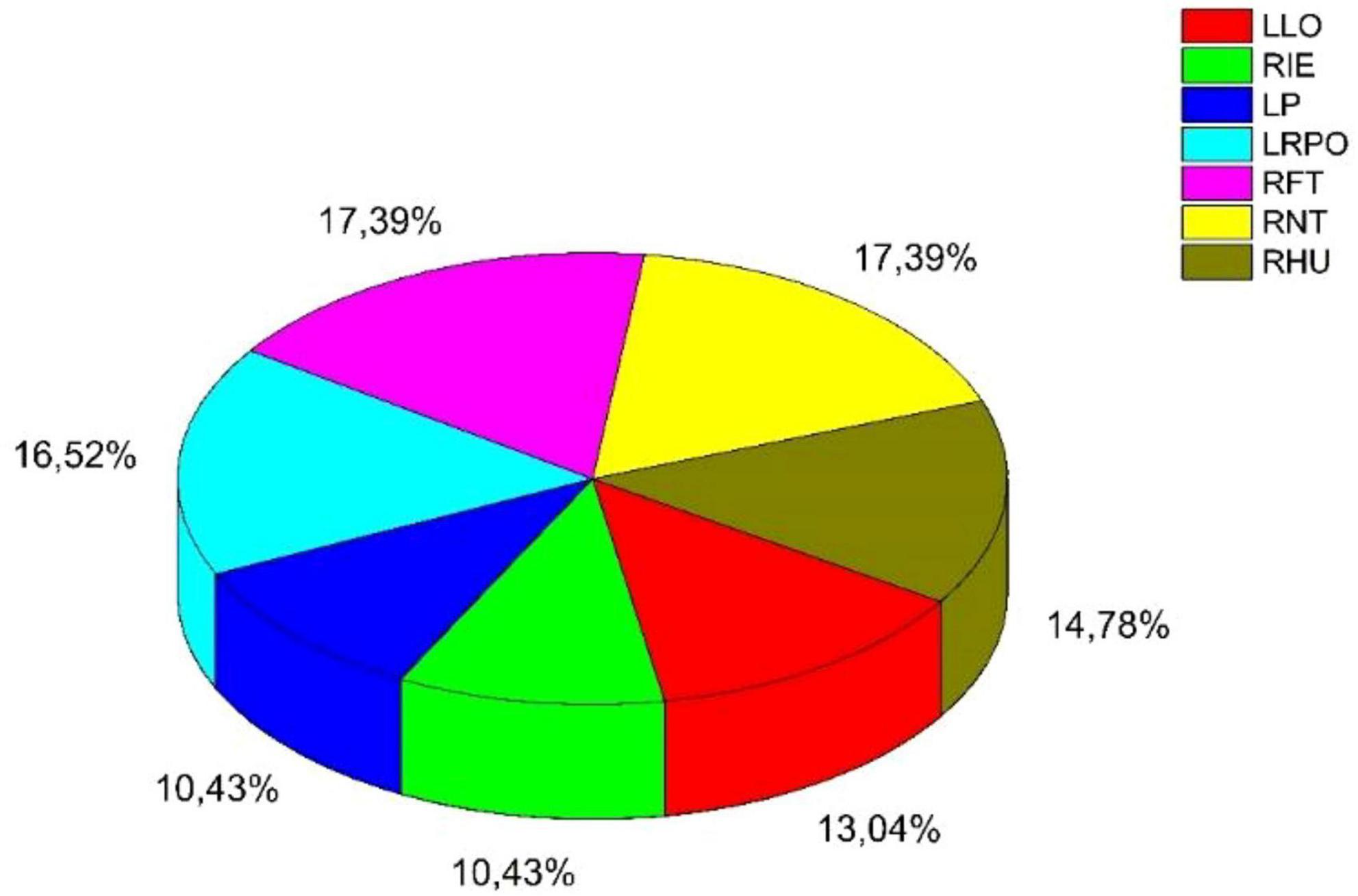

The data obtained from the students’ answers to the question, “How did participating in drama activities affect your communication skills? Did you notice any changes in the way you communicate with people?,” is presented in Figure 4.

Analysis of the students’ responses regarding the impact of participating in drama activities on their communication skills indicates that the majority of participants reported positive gains across different domains. According to the data, the most frequently cited statements were “I realized that I need to trust myself” (f = 20) and “I realized that freedom requires boundaries” (f = 20). In addition, students noted that “I learned to respect other opinions” (f = 19) and “I realized that I feel happier when I am understood” (f = 17). Less frequently reported, yet noteworthy, reflections included “I learned to listen to others” (f = 15), “I realized the importance of empathy” (f = 12), and “I learned to be patient” (f = 12).

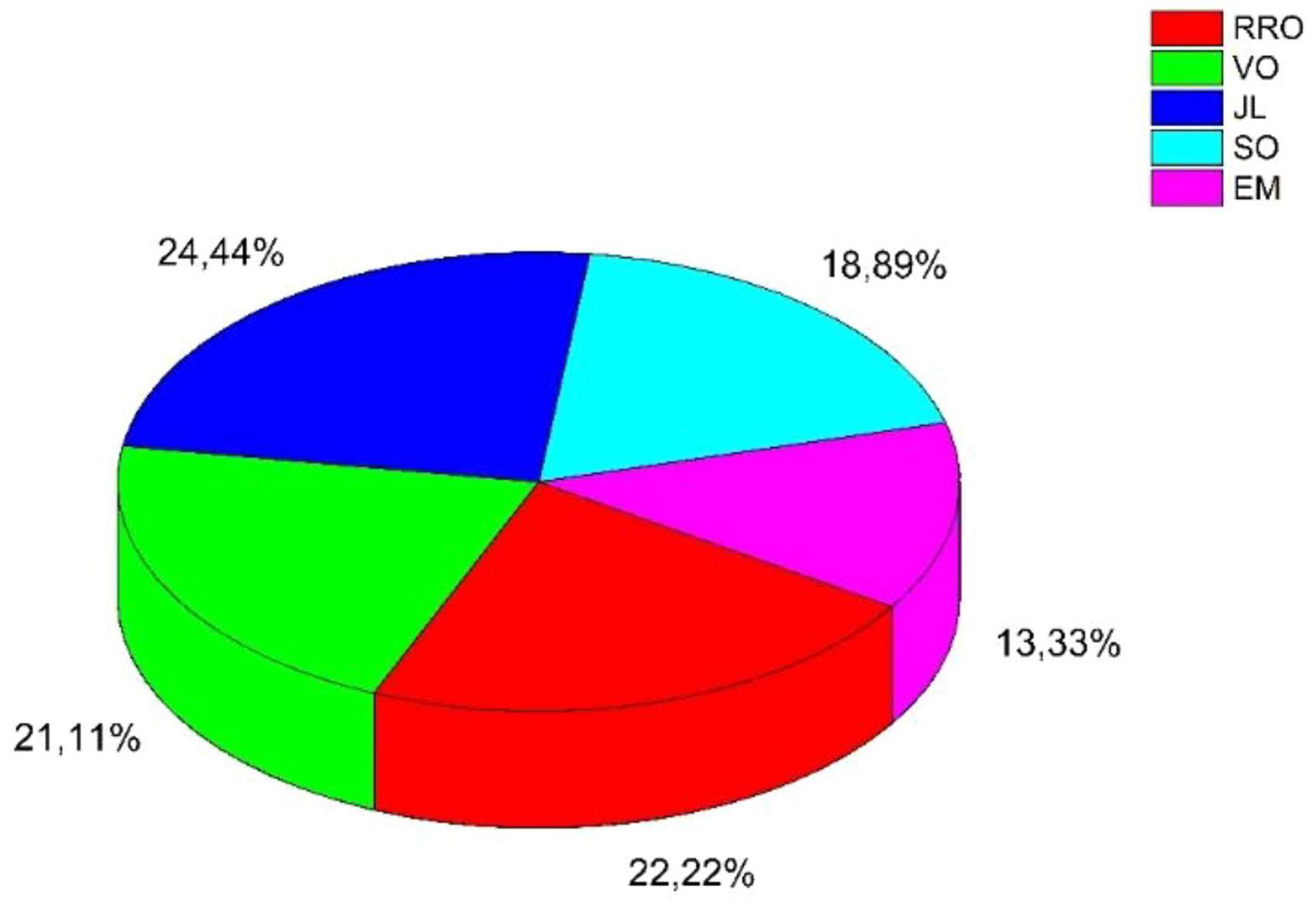

The responses to the question, “How did drama activities influence your perspective on the people and events around you? Did you notice any changes in understanding yourself or others?” were collected from the students and are presented in graphical form (Figure 5).

Analysis of the students’ responses regarding how drama activities influenced their perspectives on people and events in their surroundings revealed several noteworthy patterns. The most frequently reported response was “we should not judge without listening” (f = 22). This was followed by “we should respect the rights of others” (f = 20) and “we should value their opinions” (f = 19). Less frequently mentioned, yet still meaningful, were the views “we should be solution-oriented” (f = 17) and “we should be empathetic” (f = 12). These findings indicate that drama practices contributed to students’ ability to adopt more considerate, respectful, and constructive approaches in their interactions with others and in interpreting social situations.

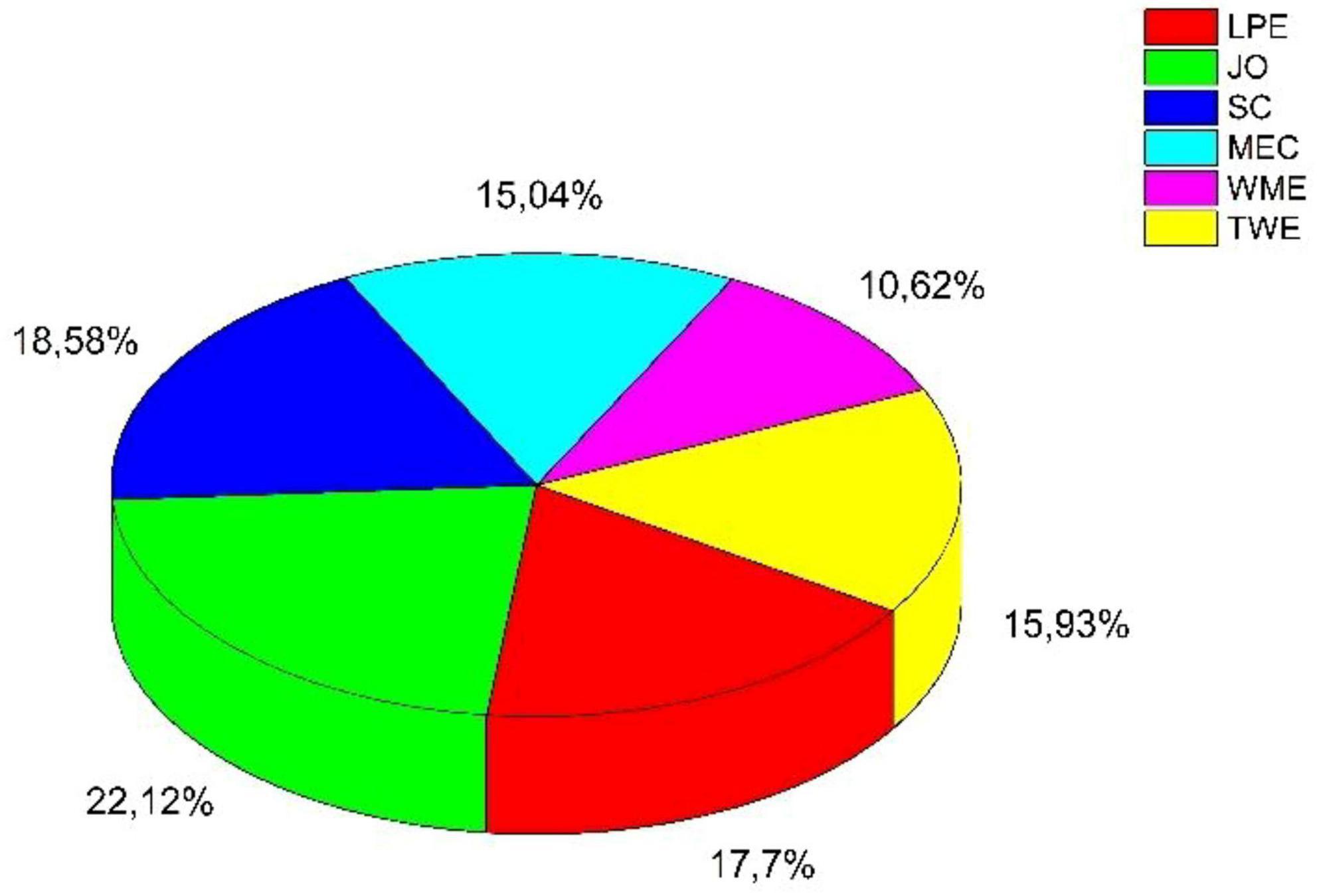

The graph presents the data obtained from the students’ answers to the question, “How will drama activities affect your friendships, group work and communication with your social circle?” (Figure 6).

When examining students’ responses regarding the effects of drama activities on their friendships, group work, and communication within their social environment, it is evident that the majority of participants reported positive gains. According to the data, the most frequently expressed response was “I will not judge people around me for their opinions” (f = 25). This was followed by “I will be more self-confident” (f = 21) and “I will listen to others more effectively” (f = 20). Less frequently, students stated that “I will be more harmonious with my environment” (f = 18), “I will manage my emotions better in communication” (f = 17), and “I will be more empathetic” (f = 12). The qualitative findings of this study indicate that drama activities have multidimensional effects on students’ communication and social skills development. Students primarily attributed their motivation to improve communication for professional growth and the desire for accurate understanding. During the activities, they experienced positive emotions, including empathy, uninhibited self-expression, and a sense of energy and connection. Additionally, these activities enhanced key communication skills such as self-confidence, respect for others’ opinions, patience, and active listening. Drama also shaped students’ perspectives on people and events, promoting behaviors like non-judgmental listening, respect for others’ rights, solution-oriented thinking, and social awareness. Within their social environments and peer interactions, students became more self-confident, empathetic, adaptable, and emotionally aware.

4 Discussion

In this study, the impact of a drama-based communication skills development program on undergraduate students’ communication competencies was examined. The findings indicate that creative drama activities significantly enhanced the communication skills of university students. A statistically significant difference was found between pre-test and post-test scores, demonstrating substantial improvement among participants. While gender-based differences were observed at the beginning, these disparities disappeared following the intervention. Moreover, variations in students’ initial self-perceived skill levels, which influenced pre-test performances, were equalized in the post-test results. This outcome suggests that creative drama activities reduce communication skill gaps among students and foster balanced development across participants (Eratay, 2021). The qualitative data confirm that drama activities enhance students’ empathy, free self-expression, self-confidence, respect for others’ opinions, and effective listening skills. Additionally, students developed social competencies such as non-judgmental listening, solution-focused approaches, and social awareness by changing their perspectives on people and events in their environment. Positive changes observed in group interactions indicate that drama activities are effective in improving students’ social relationships, collaboration, and communication competencies. These findings suggest that creative drama-based practices significantly enhance both students’ measurable communication skills and their social-emotional competencies, supporting similar findings in the literature (Günay and Dertli, 2024; Levett-Jones et al., 2024; Uçtu and Karahan, 2021). Overall, these results underscore the effectiveness of drama-based instructional methods in higher education for developing essential interpersonal competencies. The study highlights that engaging students in experiential, role-playing, and collaborative drama activities not only enhances their communication skills but also promotes self-confidence, empathy, and social awareness. Consequently, incorporating creative drama into university curricula may serve as a valuable pedagogical strategy to prepare students for both professional and social interactions, fostering holistic personal and professional development (Hu and Shu, 2025; Uçtu and Karahan, 2021).

When compared with the findings of previous literature, our study demonstrates that drama-based activities have a strong impact on students’ abilities to develop respect, empathy, collaboration, and self-confidence in communication. The activities were found to enhance students’ empathetic skills, provide freedom for self-expression, and promote positive emotional engagement. Overall, drama interventions contribute to the multidimensional development of communication competencies, particularly strengthening self-confidence, respect, empathy, and effective listening behaviors. In addition to increasing students’ social awareness and fostering understanding and respect for others, drama-based activities improve social relationships, intra-group communication, and essential social skills such as empathy and self-confidence (Altunay, 2023; Andersen, 2004; Arda Tuncdemir, 2025; Celume et al., 2020; Dereli, 2018; Goodman, 2017; Günay and Dertli, 2024; Hamzah and Gill, 2024; Hu and Shu, 2025; Kumar et al., 2022; Levett-Jones et al., 2024; Luo et al., 2024; Marzi et al., 2025; O’Toole and Dunn, 2002; Tekerek, 2007; Uçtu and Karahan, 2021).

The results of our study are consistent with previous research. Ljunggren et al. (2021) reported that in a drama-based communication program conducted with nursing students, the sessions significantly enhanced students’ verbal expression, active listening, empathy, and intra-group collaboration (Ljunggren et al., 2021). Similarly, Rusiecki et al. (2023) found that improvisation-based communication training for medical students improved trust, open communication, and problem-solving skills in doctor–patient interactions (Rusiecki et al., 2023). In addition, a psychodrama-based intervention study by Çataldaş et al. (2024) demonstrated sustained improvements in nursing students’ therapeutic communication skills and cognitive flexibility, even during a 12-month follow-up (Çataldaş et al., 2024). These findings parallel the results of our study, indicating that creative drama methods can provide sustainable development in communication competencies.

Another mechanism through which drama interventions enhance communication skills is by increasing empathic sensitivity. A study found that dietitians who participated in drama-based communication training performed better in understanding patients’ emotions, asking effective questions, and providing feedback. Similarly, Lee and Yoo (2024) emphasized that psychodrama-based reflective techniques enhanced participants’ empathic approach and body language awareness, thereby improving patient-centered communication skills (Lee and Yoo, 2024).

The findings of this study are particularly relevant for Nutrition and Dietetics students, as they suggest that more effective patient–dietitian communication can be achieved in clinical practice. Our research demonstrates that drama-based educational programs not only improve communication skills but also foster self-confidence, problem-solving, teamwork, and leadership competencies. Prueksapitak et al. (2025) highlighted that drama applications enhance perceived self-efficacy in professional communication contexts and contribute to the development of students’ professional identity, aligning with our findings (Prueksapitak et al., 2025). Furthermore, Buchholz et al. (2020) clearly demonstrated that patient simulations significantly improve the communication skills of both dietetics students and interns. These insights underscore the importance of drama-based programs in training healthcare professionals. While communication skills in dietetics, nursing, and medical faculties are often taught through theoretical courses, our results and supporting studies indicate that drama-based interventions provide experiential, lasting, and behaviorally impactful learning opportunities (Buchholz et al., 2020).

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, creative drama-based interventions were found to be effective in enhancing the communication skills of Nutrition and Dietetics students. Drama education was observed to foster students’ abilities in active listening, clear expression, and providing effective feedback during patient–dietitian interactions. The findings suggest that creative drama-based programs can positively contribute to communication competencies and interpersonal relationships. Qualitative data, demonstrate that drama activities strengthen students’ skills such as empathy, self-confidence, respect for others’ opinions, effective listening, and social awareness. These integrated findings demonstrate that drama-based practices not only measurably enhance students’ communication skills but also foster multidimensional gains such as awareness, respect, and cooperation in communication by supporting their social and emotional competencies. Future research is recommended to implement and evaluate these programs across different universities and larger sample groups. Additionally, longitudinal studies should examine how improvements in communication skills translate into clinical practice over time.

6 Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered, particularly when interpreting the quantitative findings. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the statistical power of the analyses and restrict the generalizability of the results beyond the studied group. Second, as the research was conducted within a specific educational context, the findings may not fully represent other populations or institutional settings. Third, although descriptive and inferential statistical analyses were applied, potential biases arising from participants’ self-reports and contextual factors may have influenced the accuracy of the results. Finally, as a case study, the findings should be interpreted cautiously and regarded as exploratory rather than definitive. Future research with larger and more diverse samples is recommended to validate and extend the results of this study.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Iğdir University Scientific Research and Publication Ethics Board Chairmanship. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

CC: Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Validation, Project administration, Resources.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. I declare that artificial intelligence was used only partially in the preparation of this manuscript, limited to language editing support, and all ideas and conclusions are my own.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2025.1708057/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

EW, Expressing myself well; HC, Helping my career; ISS, Improving my social skills; BUC, Being understood correctly; NCO, The necessity of caring for others; BER, The benefits of empathy in relationships; NTO, The necessity of trusting others; RO, Respecting other opinions; PCLT, The power of communication in living together; TO, Trusting ourselves; E, Empathic; V, Voluntary; FE, Free expression; PW, Patient waiting; EN, Energetic; U, Understood; LLO, I learned to listen to others; RIE, I realized the importance of empathy; LP, I learned to be patient; LRPO, I learned to respect other people’s opinions; RFT, I realized that freedom must have limits; RNT, Realized that I need to trust myself; RHU, I realized that I am happier when I am understood; RRO, We must respect the rights of others; VO, We must value their opinions; JL, We must not judge without listening; SO, We must be solution-oriented; EM, We must be empathetic; LPE, I will listen to people more effectively; JO, I will not judge those around me for their opinions; SC, I will be more self-confident; MEC, I will manage my emotions better in communication, WME, I will be more empathetic; TWE, I will be more in tune with my environment.

References

Adıgüzel, Ö (2013). Eğitimde yaratıcı drama. [Creative drama in education], 6. Baskı Edn. Ankara: Pegem Akademi. Turkish

Afacan, Ö, and Turan, F. (2012). Fen bilgisi öğretmen adaylarinin iletişim becerilerine ilişkin algilarinin belirlenmesinde yaratici drama yönteminin kullanilmasi. [Using creative drama method to determine the perceptions of science teacher candidates regarding communication skills]. Erciyes Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 1, 211–237. Turkish

Akkaya, M. A. (2018). Önce insan, önce iletişim: Bilgi ve belge yöneticileri için halkla ilişkiler. [People first, communication first: Public relations for information and document managers]. Türk Kütüphaneciliği 32, 59–61. Turkish

Altınova, H. (2006). Empati becerisinin yaratıcı drama yöntemiyle geliştirilmesi. [Developing empathy skills through creative drama]. Ankara: Yayınlanmamış proje raporu, Çağdaş Drama Derneği. Turkish

Altunay, S. (2023). Sosyal bilgiler dersinde yaratıcı drama yöntemi ile sorumluluk, saygı, çalışkanlık, duyarlılık ve dayanışma değerlerinin öğrencilere kazandırılması. [Teaching students the values of responsibility, respect, diligence, sensitivity and solidarity through creative drama in social studies classes.]. Türkiye: Sinop Üniversitesi. Turkish

Andersen, C. (2004). Learning in” as-if” worlds: Cognition in drama in education. Theory Into Pract. 43, 281–286. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip4304_6

Arda Tuncdemir, T. B. (2025). The power of creative drama: Integrating playful learning approaches in teacher education. Res. Drama Educ. J. Appl. Theatre Perform. 30, 1-22. doi: 10.1080/13569783.2025.2457745

Arslan, E., Erbay, F., and Saygın, Y. (2010). Yaratıcı drama ile bütünleştirilmiş iletişim becerileri eğitiminin çocuk gelişimi ve eğitimi bölümü öğrencilerinin iletişim becerilerine etkisinin incelenmesi. [Examining the effects of communication skills training integrated with creative drama on the communication skills of child development and education students]. Türkiye: Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi. Turkish

Aslan, B. (2018). Yaratıcı drama uygulamalarının okul öncesi dönemi öğrencilerinin besinler konusundaki öğrenmelerine ve sosyal uyum becerileri kazanmalarına etkisi. [The effects of creative drama practices on preschool students’ learning about food and gaining social adaptation skills]. Turkey: Bartin University. Turkish

Bogdan, R., and Biklen, S. K. (1997). Qualitative research for education, 368. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Bonwell, C. C., and Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC higher education reports. Sweden: ERIC.

Buchholz, A. C., Vanderleest, K., MacMartin, C., Prescod, A., and Wilson, A. (2020). Patient simulations improve dietetics students’ and interns’ communication and nutrition-care competence. J. Nutrit. Educ. Behav. 52, 377–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2019.09.022

Campbell, D. T., and Stanley, J. C. (2015). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. New York, NY: Ravenio books.

Çataldaş, S. K., Atkan, F., and Eminoğlu, A. (2024). The effect of psychodrama-based intervention on therapeutic communication skills and cognitive flexibility among nursing students: A 12-month follow-up study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 80:104118. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2024.104118

Celume, M.-P., Goldstein, T., Besançon, M., and Zenasni, F. (2020). Developing children’s socio-emotional competencies through drama pedagogy training: An experimental study on theory of mind and collaborative behavior. Eur. J. Psychol. 16, 707–726. doi: 10.5964/ejop.v16i4.2054

Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Appl. Psychol. Measurem. 12, 425–434. doi: 10.1177/014662168801200410

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research designs. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Dere, Z. (2019). Dramanın öğretmen adaylarının iletişim becerilerine etkisinin incelenmesi. [Examining the effect of drama on communication skills of prospective teachers]. Başkent Univ. J. Educ. 6, 59–67. Turkish

Dereli, E. (2018). Yaratıcı drama eğitimi ve yaratıcı drama temelli kişilerarası ilişkiler eğitim programının öğretmen adaylarının iletişim ve sosyal problem çözme becerilerine etkisinin incelenmesi. [Examining the effects of creative drama education and creative drama-based interpersonal relations training program on communication and social problem-solving skills of prospective teachers.]. Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 20, 95–119. doi: 10.32709/akusosbil.409590 Turkish

Dikici, H., Gündoğdu, R., and Koç, M. (2003). “Yaratıcı dramanın problem çözme becerilerine etkisi. [The effect of creative drama on problem-solving skills],” in işlemleri sekizinci Ulusal Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Kongresi. Malatya, 9–11. Turkish

Eratay, E. (2021). Özel eğitimde yaratici drama çalişmalarinin incelenmesi. [Examining creative drama studies in special education]. J. Uludag Univ. Faculty Educ. 34, 335–385. doi: 10.19171/uefad.865658 Turkish

Erdem, A. B. (2021). Iletişim becerilerinin geliştirilmesinde yaratici dramanin kullanimi. [The use of creative drama in developing communication skills]. J. Innov. Healthcare Pract. 2, 88–95. Turkish

Erkan, H. (2005). Yaş grubu çocukların yaratıcılıklarına drama ve rahatlama çalışmalarının etkisi. [The effects of drama and relaxation activities on the creativity of age-group children]. Yayınlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi, Ankara: Gazi Üniversitesi, Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü. Turkish

Eyüp, B. (2023). The effect of creative drama on the creative self-efficacy of pre-service teachers. J. Pedagogical Res. 7, 48–74. doi: 10.33902/JPR.202321418

Fraenkel, J. R., and Wallen, N. E. (1990). How to design and evaluate research in education. Sweden: ERIC.

Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., et al. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 8410–8415. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319030111

Gökçearslan Çifci, E., and Altinova, H. (2017). Sosyal hizmet eğitiminde yaratıcı drama yöntemiyle iletişim becerisi geliştirme: Ders uygulaması örneği. [Development of comunnication skills through creative drama at social work education: An example of an implementation of the course]. Element. Educ. Online 16, 1384–1394. Turkish

Gönen, M., and Dalkılıç, N. U. (2003). Çocuk eğitiminde drama: Yöntem ve uygulamalar. [Drama in child education: Methods and applications]. Irving, TX: Epsilon. Turkish

Goodman, D. S. (2017). Teamwork, communication and empathy: A case study examining social skills in drama class. Turkey: Bilkent Universitesi.

Günay, U., and Dertli, S. (2024). Thinking like a nurse: The power of drama on nursing students’ professional education and communication skills. J. Qual. Res. Educ. 39, 141–159. doi: 10.14689/enad.39.1968

Hamzah, M., and Gill, A. K. (2024). The impact of social-emotional competencies on drama students with dyslexia during the pandemic. Asia Pacific J. Dev. Differ. 11, 99–121. doi: 10.3850/S2345734124001990

Harris, A. D., McGregor, J. C., Perencevich, E. N., Furuno, J. P., Zhu, J., Peterson, D. E., et al. (2006). The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 13, 16–23. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1749

Heathcote, D., Johnson, L., and O’neill, C. (1984). Collected Writings on Education and Drama. France: Hutchinson.

Hobson, W. L., Hoffmann-Longtin, K., Loue, S., Love, L. M., Liu, H. Y., Power, C. M., et al. (2019). Active learning on center stage: Theater as a tool for medical education. MedEdPORTAL 15:10801. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10801

Hu, Y., and Shu, J. (2025). The effect of drama education on enhancing critical thinking through collaboration and communication. Educ. Sci. 15:565. doi: 10.3390/educsci15050565

Karasar, N. (2011). Bilimsel araştırma yöntemi. [Scientific research method], 11. baskı Edn. Ankara: Nobel Yayınevi. Turkish

Karateke, E. (2006). Yaratıcı dramanın ilköğretim II. kademede 6. sınıf öğrencilerinin yazılı anlatım becerilerine olan etkisi. [The effect of creative drama on the written expression skills of 6th grade students in the second stage of primary education.]. Yayımlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi, Hatay: Mustafa Kemal Üniversitesi. Turkish

Kardaş, S. (2023). A comprehensive review of forgiveness interventions in Türkiye. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 6, 289–321.

Kerimbayev, N., Umirzakova, Z., Shadiev, R., and Jotsov, V. (2023). A student-centered approach using modern technologies in distance learning: A systematic review of the literature. Smart Learn. Environ. 10:61. doi: 10.1186/s40561-023-00280-8

Kesici, A. E. (2014). Drama dersine ilişkin öğretmen görüşleri. [Teachers’ opinions on drama classes]. Abant Ýzzet Baysal Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 14, 186–203. doi: 10.17240/aibuefd.2014.14.2-5000091534 Turkish

Kılıç, B. (2012). Ýlköğretim okullarında uygulanan mesleki çalışmalarda yaratıcı drama uygulamasının öğretmenlerin iletişim becerilerine etkisi. [The effect of creative drama application on teachers’ communication skills in professional studies in primary schools.]. Yaratıcı Drama Dergisi 7, 38–47. Turkish

Kumar, T., Qasim, A., Mansur, S. B., and Shah, A. H. (2022). Improving EFL students’ speaking proficiency and self-confidence using drama technique: An action research. Cypriot J. Educ. Sci. 17, 372–383. doi: 10.18844/cjes.v17i2.6813

Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 4:863. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

Lavasani, M. G., Afzali, L., and Afzali, F. (2011). Cooperative learning and social skills. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 15, 1802–1805. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.006

Lee, S. H., and Yoo, H. J. (2024). Therapeutic communication using mirroring interventions in nursing education: A mixed methods study. Asian Nurs. Res. 18, 435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2024.09.012

Levett-Jones, T., Brogan, E., Debono, D., Goodhew, M., Govind, N., Pich, J., et al. (2024). Use and effectiveness of the arts for enhancing healthcare students’ empathy skills: A mixed methods systematic review. Nurse Educ. Today 138:106185. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106185

Ljunggren, C., Carlson, E., and Isma, G. E. (2021). Drama with a focus on professional communication–A phenomenographic study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 52:103022. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103022

Luo, S., Ismail, L., Ahmad, N. K. B., and Guo, Q. (2024). Using process drama in EFL education: A systematic literature review. Heliyon 10:e31936. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e31936

Mantione, R. D., and Smead, S. (2003). Weaving through words: Using the arts to teach reading comprehension strategies. Sweden: ERIC.

Martin, J. N., and Nakayama, T. K. (2013). Intercultural communication in contexts. 6. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Marzi, T., Adembri, C., Vignozzi, L., Innocenti, B., Cruciata, M. A., and Lippi, D. (2025). Medicine at theatre: A tool for well-being and health-care education. BMC Med. Educ. 25:258. doi: 10.1186/s12909-025-06793-9

McNaughton, M. J. (2004). Educational drama in the teaching of education for sustainability. Environ. Educ. Res. 10, 139–155. doi: 10.1080/13504620242000198140

Michael, J. (2006). Where’s the evidence that active learning works? Adv. Physiol. Educ. 30, 159–167. doi: 10.1152/advan.00053.2006

Mutlaq, A. S. (2023). The effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral counseling program in improving the level of social skills and reducing isolation behaviors among university students. Perspect. Sci. Educ. 60, 417–431. doi: 10.32744/pse.2022.6.25

Okvuran, A. (1993). Yaratıcı drama eğitiminin empatik beceri ve empatik eğilim düzeylerine etkisi. [The effect of creative drama education on empathic skills and empathic tendency levels]. Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara: Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü. Turkish

O’Toole, J., and Dunn, J. (2002). Pretending to Learn-Helping children learn through drama. London: Pearsons.

Owen, F., and Bugay, A. (2014). İletişim becerileri ölçeği’nin geliştirilmesi: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. [Development of the communication skills scale: A validity and reliability study]. Mersin Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergisi 10, 51–64. doi: 10.17860/efd.95021 Turkish

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods, 3rd. Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research. J. Eng. Educ. 93, 223–231. doi: 10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

Prueksapitak, P., Inchan, N., and Pakdeeronachit, S. (2025). Utilizing creative drama practices for enhancing communication skills of medical students: An applied theatre intervention. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 8, 253–265. doi: 10.37074/jalt.2025.8.1.4

Rances, J. N. (2005). Student perceptions of improving comprehension through drama as compared to poetry and fiction in college English freshman composition courses. Chester, PA: Widener University.

Reith-Hall, E., and Montgomery, P. (2023). Communication skills training for improving the communicative abilities of student social workers: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 19:e1309. doi: 10.1002/cl2.1309

Rusiecki, J. M., Orlov, N. M., Dolan, J. A., Smith, M. P., Zhu, M., and Chin, M. H. (2023). Exploring the value of improvisational theater in medical education for advancing the doctor–patient relationship and health equity. Acad. Med. 98, S46–S53. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000005183

Saçlı, F. (2013). Yaratıcı drama eğitiminin aday beden eğitimi öğretmenlerinin eleştirel düşünme becerileri ve eğiliml. [Effects of creative drama education on critical thinking skills and dispositions of candidate physical education teachers]. Turkey: Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü. Turkish

Tanrıseven, I., and Aykaç, M. (2013). Üniversite öğrencilerinin yaratici dramanin kişisel ve mesleki yaşantilarina katkisina ilişkin görüşleri. [University students’ views on the contribution of creative drama to their personal and professional lives]. Adıyaman Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 15, 329–348. Turkish

Tekerek, N. (2007). Yaratıcı dramanın özgürlüğü, alışkanlıkların kalıpları ve bir uygulama örneği. [The freedom of creative drama, patterns of habits and an example of application]. J. Uludag Univ. Faculty Educ. 20, 189–219. Turkish

Türkan, ÇÇ, and Dinç, A. (2020). 6. sınıf Türkçe dersinde drama yöntemini kullanmanın öğrencilerin sosyal beceri ve derse karşı tutumuna etkisi. [The effect of using drama method in 6th grade Turkish course on students’ social skills and attitudes towards the course.]. Iğdır Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi 36, 146–161. doi: 10.54600/igdirsosbilder.1437608 Turkish

Uçtu, A. K., and Karahan, N. (2021). The impact of communication education provided with creative drama method on midwifery undergraduates. Eur. J. Midwifery 5:42.

Ulubey, Ö, and Gözütok, F. (2015). Future citizenship, democracy and human rights education with creative drama and other interactive teaching methods. Educ. Sci. 40, 87–109. doi: 10.15390/EB.2015.4845

Üstündağ, E. (2006). Ýletişim becerilerini geliştirme programının güvenlik bilimleri fakültesi öğrencilerinin kendini açma davranışlarına etkisi. [The effect of communication skills development program on self-disclosure behaviors of security sciences faculty students]. Turkey: Ankara Universitesi. Turkish

Van Laar, E., Van Deursen, A. J., Van Dijk, J. A., and De Haan, J. (2017). The relation between 21st-century skills and digital skills: A systematic literature review. Comp. Hum. Behav. 72, 577–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.010

Wardrope, W. J. (2002). Department chairs’ perceptions of the importance of business communication skills. Bus. Commun. Quar. 65, 60–72. doi: 10.1177/108056990206500406

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Keywords: education, creative drama, communication skills, undergraduate students, active learning

Citation: Cam Turkan C (2025) Creative drama in higher education: effects on students’ communication skills. Front. Educ. 10:1708057. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1708057

Received: 18 September 2025; Accepted: 27 October 2025;

Published: 27 November 2025.

Edited by:

Rania Zaini, Umm Al-Qura University, Saudi ArabiaReviewed by:

Ika Lestari, Universitas Negeri Jakarta Fakultas Ilmu Pendidikan, IndonesiaPedro Bruno Silva Lemos, University of International Integration of Afro-Brazilian Lusophony, Brazil

Copyright © 2025 Cam Turkan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cigdem Cam Turkan, Y2lnZGVtdHVya2FuQGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; Y2lnZGVtLnR1cmthbkBpZ2Rpci5lZHUudHI=

Cigdem Cam Turkan

Cigdem Cam Turkan