- 1Life Span Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

- 2Special Education, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, United States

- 3Elementary and Special Education, Georgia Southern University, Statesboro, GA, United States

Introduction: Advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have the potential to augment and alter writing instruction and the supports available to struggling writers and those with learning disabilities. Yet research continues to show that special education teachers do not feel prepared to integrate technology into writing instruction, despite evidence supporting its use to improve writing outcomes for students with disabilities.

Methods: This study surveyed 420 high-incidence special education teachers nationwide using the Preparation to Integrate Writing and Technology in Special Education for Teachers Scale (PIWTSE-T), a validated measure. Data analysis included descriptive statistics, Pearson and Spearman correlations, multiple regression, and ANOVA to examine AI integration and its predictors.

Results: Descriptive results indicated that special education teachers rarely use AI tools at any stage of the writing process. Multiple regression revealed that teachers' attitudes toward AI were the strongest predictor of AI use. A final regression model identified three significant predictors—AI use to support student learning (AISS), AI use to support teaching practice (AITP), and preparation to integrate technology into writing (PITW), explaining 53% of the variance in AI integration.

Discussion: This study adds to the growing body of literature highlighting the need for special education teacher preparation programs to strengthen their efforts to prepare educators to leverage technology, specifically AI, as a tool for evidence-based writing instruction. Future research should focus on developing and refining teacher-training models that leverage technology to improve writing outcomes for students with disabilities.

Introduction

In K-12 education, writing serves as the primary medium through which students demonstrate content mastery, whether through the analysis of literary themes, the articulation of historical arguments, or the solution of scientific problems. By the middle and high school years, writing becomes the principal means by which teachers assess student comprehension, and writing proficiency is directly linked to academic achievement, access to higher education, and long-term career prospects. For students with disabilities (SWDs), however, writing presents persistent challenges. Decades of national data, such as the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), highlight persistent gaps in writing achievement, with SWDs disproportionately underperforming their peers (2012). These difficulties are rooted in barriers present throughout the writing process, including encoding skills, executive functioning demands (e.g., organization), and higher-order composition skills (Batorowicz et al., 2012). Without explicit writing instruction and support, SWDs are at a significant disadvantage, as this impedes their ability to participate meaningfully in the curriculum, demonstrate their understanding, and acquire the skills vital for post-secondary success and employment. The lack of effective writing instruction, compounded by teachers' limited preparation to teach writing, exacerbates challenges with writing expectations and, overall, student learning outcomes.

Technology as a solution

For decades, technology has been viewed as a key solution to these challenges. When paired with evidence-based writing practices, tools such as speech-to-text, predictive spelling, and digital graphic organizers have shown promise for improving students' writing outcomes (Rowland et al., 2020). However, despite increased access to one-to-one devices and digital tools, the integration of these supports into writing instruction has lagged, as research consistently reports a lack of meaningful integration of technology into writing instruction (Freedman et al., 2016). Studies reveal that teachers, including special educators, often use technology for surface-level tasks such as word processing rather than embedding it into the writing process to support planning, drafting, and revising (Flanagan et al., 2024).

For effective technology integration in writing instruction, research suggests adopting the Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework (Mishra and Koehler, 2006). The framework necessitates intentional application, ensuring technology use is purposeful and aligned with learning goals (Goldman et al., 2024). The TPACK framework supports teachers in deliberately integrating the technologies students use (e.g., text-to-speech, adaptive learning platforms) by considering their pedagogical approach (e.g., explicit modeling, direct instruction) and content understanding (e.g., genre types, how to hold writing conferences). Research shows that instruction in the TPACK framework increases teachers' confidence, knowledge, and use of technology in their classrooms (Rodríguez Moreno et al., 2019) and is positively correlated with teaching effectiveness (Colón et al., 2023). However, many teachers are more confident and comfortable with pedagogy and content knowledge than with technology, which affects their TPACK integration (Yue et al., 2024).

The rapid emergence of generative AI further complicates the already complex intersection of writing and technology. Tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and MagicSchool.AI have rapidly altered writing instruction in K-12. When first released, many districts immediately banned AI (Klein, 2024), viewing it as a threat to authentic assessment that raised questions about plagiarism, authorship, and academic integrity, a belief still held by many educators (Graham et al., 2025; Ng et al., 2023). Many school districts have since reversed these initial bans (Bushweller, 2025) and are now working with technology companies to support teachers in integrating AI into their practice (Langreo, 2025).

This shift from fear to acceptance highlights the urgent need for clarity. However, policy and guidance related to the ethical and effective integration of AI are still evolving. While 33 states now have official AI guidance (AI for Education, 2025) and 45% of surveyed principals report having school or district policies, these measures do not necessarily translate to comprehensive professional development (PD). A recent RAND survey indicated that only roughly half of districts nationwide provided any training on AI tools (Diliberti et al., 2025). Furthermore, district leaders shared that these trainings often focused on improving teachers' comfort and views of AI rather than on meaningful integration, forcing many to resort to a “do-it-yourself” approach due to a lack of external AI integration experts (Diliberti et al., 2025).

Challenges with teacher training

The primary way to improve writing outcomes for SWDs is to prepare well-trained special education teachers who can deliver explicit, evidence-based writing instruction (Finlayson and McCrudden, 2020; Graham et al., 2022). But, teachers report dedicating only a quarter of the recommended hour to writing instruction (Graham, 2019; Harris and McKeown, 2022). However, research on teacher education highlights persistent limitations in how special educators are prepared to integrate technology into instruction, particularly for writing (Taylor et al., 2020). Over 80% of teachers report feeling underprepared to teach writing, according to a recent national survey of more than 1,350 general and special education teachers (Galiatsos et al., 2019). Teachers often receive minimal, if any, writing-specific coursework (Brindle et al., 2016; Gillespie Rouse et al., 2021; Troia and Graham, 2016). Just 10% of special education programs offer a standalone course on the subject (Harris and McKeown, 2022). This lack of specialized training is clearly underscored by a survey from Flanagan et al. (2024), which found that only about one-third of the 336 special education teachers surveyed had completed a writing instruction course in their undergraduate program. While some teachers receive writing instruction through language arts or reading methods courses (Myers et al., 2016; Brenner and McQuirk, 2019), the content is rarely comprehensive (Galiatsos et al., 2019). In many cases, this instruction constitutes little more than a brief, dedicated module on writing. The absence of this coursework can be attributed to several factors: limited time for credit hours, insufficient instructor expertise, and a lack of veteran teachers to serve as writing models. Few states require dedicated writing methods coursework (Freedman et al., 2016). As a result of this training gap, most teachers enter K-12 classrooms without the necessary skills to improve writing outcomes.

The lack of high-quality writing instruction for special education teachers is not an isolated issue. Technology coursework often focuses on broad educational technology rather than providing explicit guidance on leveraging tools to meet the specific needs of students with disabilities, particularly in writing instruction. This inconsistency leaves teachers underprepared to use technology effectively (Johnson et al., 2016). The current methods for teaching technology integration, whether as standalone courses or a more programmatic approach, also have significant limitations for future teachers. While standalone technology courses can build confidence (Falloon, 2020; Ottenbreit-Leftwich et al., 2018), they often fail to prepare teachers to overcome key internal factors, such as technology anxiety, that hinder effective classroom integration (Falloon, 2020). This course design also rarely provides pre-service teachers with opportunities to apply course content to students with disabilities (Foulger et al., 2017).

On the other hand, a more programmatic approach offers the opportunity to embed technology integration coursework throughout a teacher's preparation (Voithofer and Nelson, 2021). Empirical studies show that targeted interventions, such as embedding practice with assistive technologies like speech-to-text, word prediction, and digital graphic organizers into methods courses, significantly improve teacher candidates' knowledge and confidence (Edyburn, 2001; Flanagan et al., 2024; Regan et al., 2019). However, this level of meaningful integration remains the exception rather than the norm across preparation programs. As a result, many teachers enter the field underprepared to support the writing development of SWDs.

Limited professional development opportunities

Research on teacher professional learning reinforces these findings, showing that special education teachers' lack of preparation leads to their underutilization of technology, even when devices and digital tools are widely available. Studies have shown that teachers primarily use technology for surface-level tasks, such as word processing, rather than supporting the deeper aspects of the writing process, including brainstorming, drafting, and revising (Rowland et al., 2020; Regan et al., 2019). Barriers such as limited time, inadequate training, and a lack of administrative support remain significant factors impeding more meaningful use (Anderson and Putman, 2020).

This lack of opportunity to learn about emerging technologies and how to integrate them into the writing process is even more alarming when considered alongside the fact that AI is augmenting what writing is and how it is taught. PD that provides hands-on experience with assistive technologies and aligns with evidence-based writing practices enhances teachers' self-efficacy and classroom use (Little et al., 2018). Yet consistent, practice-based PD opportunities are limited in scope and reach, leaving many teachers unable to implement technology in ways that improve students with disabilities' writing outcomes.

Effective AI-focused professional development (PD) must first establish a clear understanding of AI and its instructional purpose. Research confirms that, like any high-quality PD, AI training should be hands-on, contextualized, and offer ongoing support (Meylani, 2024). More specifically, for AI, successful PD builds foundational AI literacy, explores classroom applications, and addresses ethical and privacy issues (Brandão et al., 2024; Yau et al., 2022). Despite this, PD focused on meaningful integration of AI is often missing in schools (Al-Ali and Miles, 2025). Teachers advocate for training that aligns AI-powered tools with curriculum learning goals and guides their pedagogical decision-making, rather than reiterating technical or policy guidance (Al-Ali and Miles, 2025). Thus, teachers should be empowered to form committees to evaluate and augment current instructional and assessment methods using AI, and to engage in peer-to-peer collaborations to continuously refine their AI practice (Al-Ali and Miles, 2025). Current challenges in delivering high-quality PD include limited awareness and technical and ethical obstacles (Aljemely, 2024). The need for this training is particularly relevant in writing instruction, where generative AI tools have demonstrated the ability to differentiate practice, deliver immediate and individualized feedback, and increase student engagement (Kong and Yang, 2024; Ng et al., 2023).

Although research directly examining AI use in PD for students with disabilities is still emerging, several studies point to AI's potential to personalize instruction, adapt materials, and provide accessible supports that may benefit learners who need additional scaffolding (Ng et al., 2023; Kong and Yang, 2024). This includes AI-supported writing interventions, real-time feedback tools, and platforms that offer information aligned with students' individual learning profiles. The literature also indicates that teachers need guidance on adapting AI tools for use in inclusive classrooms, highlighting a significant gap in current PD offerings.

Purpose

Given the limited instructional preparation teachers receive in writing and technology, coupled with the persistent struggles students face in writing, it is important to determine if a link exists between this preparatory training and teachers' use of innovative technologies to support student writing outcomes. While AI holds promise as a tool to help students brainstorm, draft, revise, and share their writing, its use depends largely on how teachers are prepared, what they believe, and the contexts in which they teach. By examining both current practices and the factors that predict whether teachers incorporate AI into their writing instruction, this study aims to shed light on where teacher preparation and professional learning are falling short and where they can be strengthened. The goal is to provide practical insights that teacher educators, school leaders, and policymakers can use to support teachers in making informed, meaningful use of AI so that students with disabilities have greater opportunities to succeed as writers and learners. Thus, this study examines the role of AI in writing instruction for SWDs, focusing on three key areas: its integration into the writing process, the influence of teacher preparation, and the predictive beliefs and practices of integration. The following research questions guide this study:

1. What is the extent of special education teachers' current use of AI tools in the various phases of the writing process?

2. To what extent do teachers' self-reported scores on the PIWTSE-T predict their use of AI tools in the writing process?

3. Which teacher-related factors (e.g., preparation, beliefs, and contextual conditions) are associated with their use of AI to support writing instruction for students with disabilities?

Method

Sample and recruitment

This pilot study included a convenience (i.e., professional contacts and in-service special education teachers enrolled in a Midwestern university's online high incidence special education Master's program) and random (i.e., the use of a purchased email list from Market Data Retrieval (MDNR), social media postings, and flyers at conferences and PD sessions) sampling of 420 special education teachers who met the following criteria: (a) hold a high-incidence special education license (or the equivalent, e.g., mild/moderate credential, that allows individuals to teach students with learning disabilities, emotional/behavioral disabilities, etc.; Congressional Research Service, 2020) and (b) currently teach students in grades K-12. To maintain data integrity, we excluded all surveys completed by non-teachers or automated programs (bots).

The survey was initiated by 666 participants, of whom 420 met the inclusion criteria. Surveys were excluded from analysis if they were blank (n = 98), were not completed by high-incidence special education teachers (n = 28), or were duplicate submissions (n = 60). Additionally, due to the nature of online surveys, 58 were found to be fraudulent or fake. Those who indicated they student taught during COVID and had more than 6 years of teaching experience were removed, as this combination is impossible (n = 54). COVID school closures occurred at most 5 years before this study, meaning teachers could have at most 4 years of classroom experience. Other responses were removed because participants completed all multiple-choice sections but left blank short-answer questions (n = 3). Research supports that bots tend to skip open-ended questions (Griffin et al., 2021). Finally, participants who submitted an incomplete W-9, an Internal Revenue Service tax form for independent contractors (e.g., missing information or no “wet” signature; n = 1) were also removed. The secondary coder, a first-year doctoral student in special education, confirmed the exclusion counts.

The sample included teachers who taught in resource (n = 215), co-taught (n = 168), and special day (n = 88) classrooms. They had teaching experience ranging from 2 years to more than 30 years (M = 14.24; MDN = 12). Nearly 90% stated they had one device per student in their classrooms, with Chromebooks being the most common device, indicating that their classrooms were equipped with the technology needed to support the writing process. When asked to reflect on their pre-service training, surveyed teachers obtained their training in master's programs with licensure (n = 160), 4-year bachelor's degree programs combined with licensure (n = 147), intern or alternate route programs (n = 29), and licensure programs independent of a degree (n = 16). Most participants did not have standalone technology (n = 215) or standalone writing (n = 233). Table 1 shares the demographics for the participants and their preparation programs.

Instrument and scale development

This study piloted the Preparation to Integrate Writing and Technology in Special Education for Teachers Scale (PIWTSE-T), a valid and reliable measure both as individual subtests and as a whole measure. Current AI for Teaching Practice (AITP; α = 0.93), Current Use of AI for Student Support (AISS; α = 0.91), Current Use of AI in the Writing Process (AIW; α = 0.92), Preparation to Teach Writing (PTW; α = 0.94), Preparation to Integrate Technology into Teaching (PITT; α = 0.97), Preparation to Integrate Technology into Writing (PITW; α = 0.90) and the Reflection of Abilities to Integrate Technology into Writing Instruction (PITWR; α = 0.91) scales (see Table 2 for descriptive statistics and internal consistency).

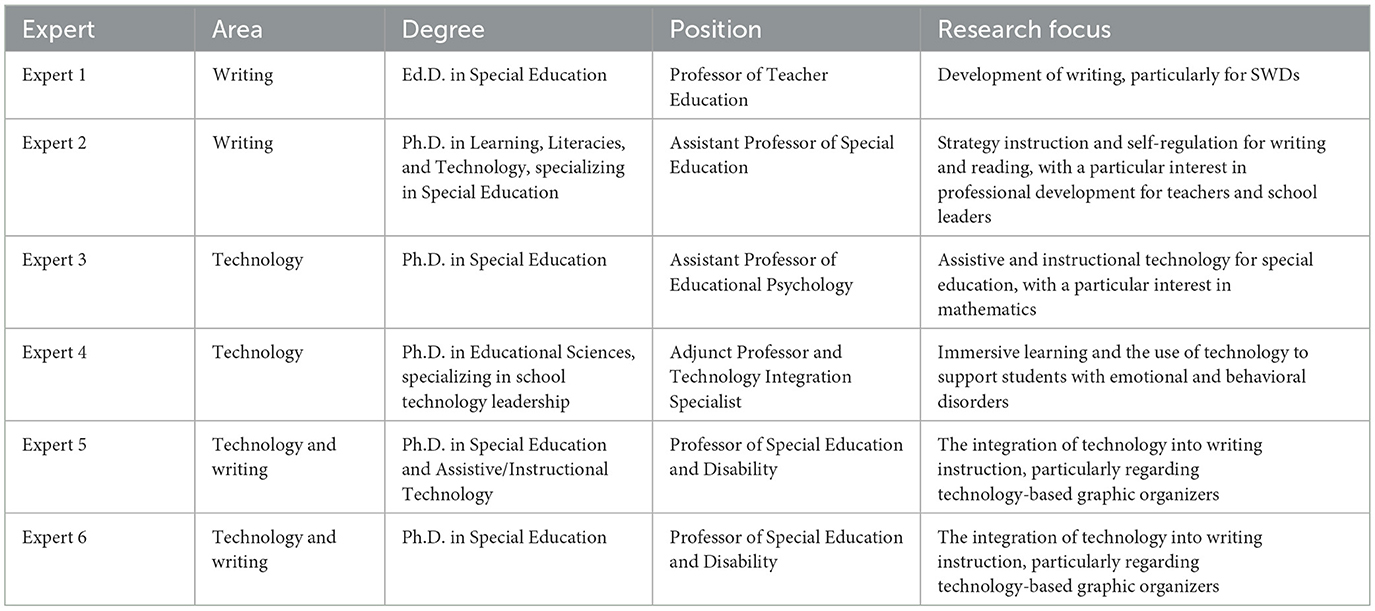

Items were validated through expert reviews and cognitive focus groups. Created in Qualtrics, the scales used a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. Complete measure can be found in Table 3. To establish criterion validity, items on the PIWTSE-T were generated to align with existing guidance on evidence-based writing instruction, technology integration recommendations, and AI guidance. A crosswalk of the guidance used for item generation and the corresponding subtest is shown in Table 3. Next, expert reviews of the items established test content validity. The experts included two in writing, two in technology integration, and two in technology integration into writing. For more information on the experts, see Table 4. Experts were asked to rate items as “samples well,” “samples okay,” and “does not sample well. The survey was refined based on their feedback. Next, three cognitive focus groups and one cognitive interview with special education teachers were conducted to establish response-process validity. Based on their responses, the survey was refined. Throughout the process, a methodologist was involved to ensure the survey development followed best practice.

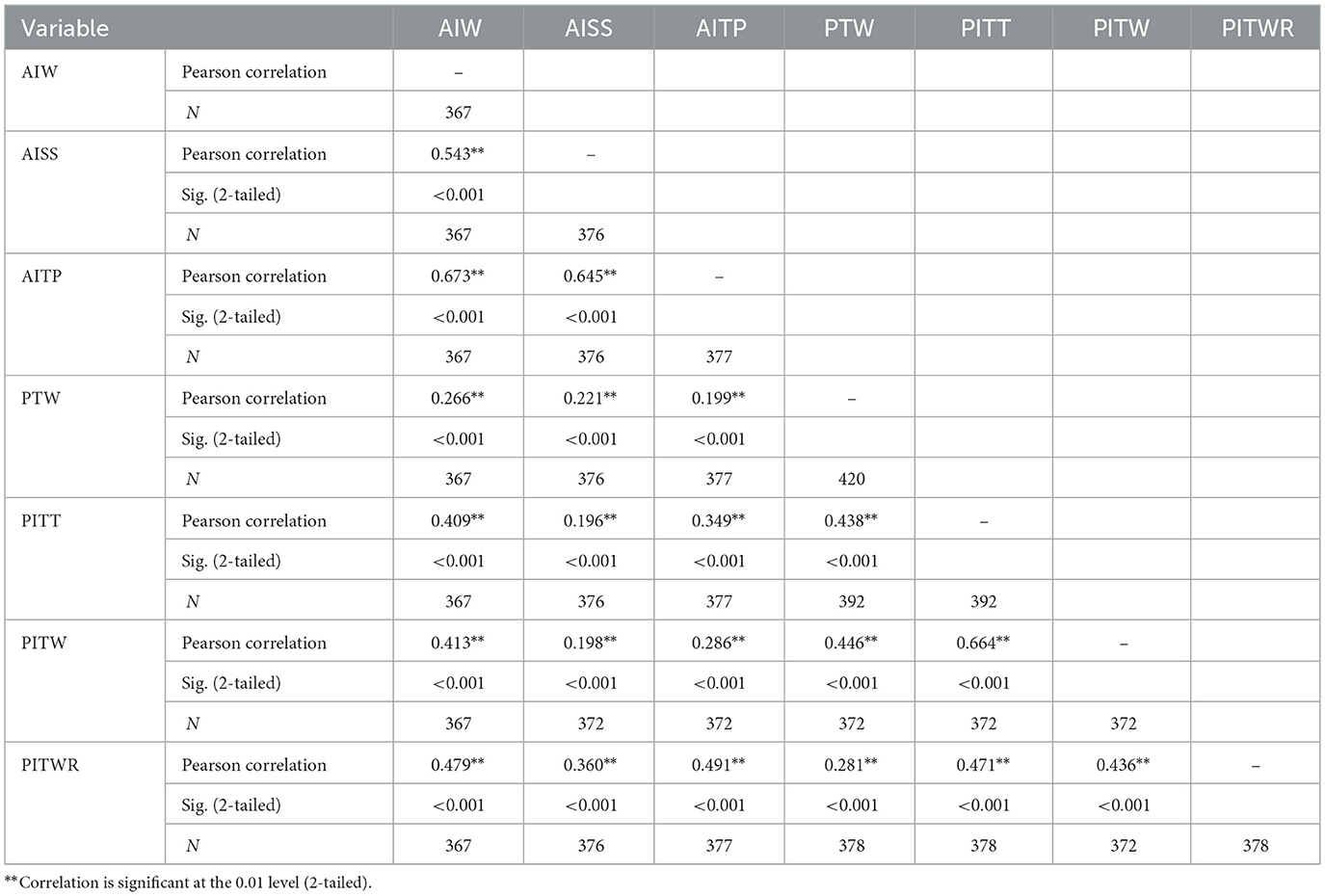

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted to determine internal structure validity. The exploratory factor analysis yielded a clear seven-factor solution, with each subscale loading as a distinct, separate dimension. Additionally, several subtests were correlated with existing measures to assess convergent validity. Correlations are shown in Table 5. Overall, there was a statistically significant, positive correlation coefficient for each subscale.

Procedures

Participants accessed the survey using the Qualtrics platform. Before beginning, all participants were presented with the Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved informed consent. Once consent was provided, participants were asked to respond to a series of items using a five-point Likert scale. The survey took approximately 20 min to complete. Participants who completed at least 80% of the survey and submitted a W-9 form received a $20 Amazon gift card. Survey data were collected via a Qualtrics survey and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29.

Data analysis

To answer research question one, descriptive statistics, including means and medians, were used. The questions used a common stem to ask participants about their use of AI for each stage of the writing process. On a scale of 1–5, participants were asked to rate their agreement with the following statement for each of the four items: “In my current teaching of Students with Disabilities (SWDs), I use Artificial Intelligence (AI; e.g., CoPilot, ChatGPT, Gemini, MagicSchool.AI, Brisk) for…” The four separate items were: brainstorming, drafting and text generation, editing and revising, and publishing.

Research question two was answered with a multiple regression analysis to investigate how teachers' attitudes and preparation for teaching writing, their integration of technology into teaching, and their use of AI in the classroom influence their use of AI tools in the writing process. Multicollinearity diagnostics were conducted to assess the degree of overlap among predictors.

Research question three explored the factors that influence teachers' use of AI to support the writing process in their teaching of SWDs. This was done using regression analysis to examine predictors of AI use in writing instruction. A Pearson's correlational analysis was conducted to determine the relationship between teachers' perceptions and attitudes toward integrating technology into the writing process and the extent to which they integrate technology into the writing process. A Spearman's rank-order correlation was conducted to examine the relationship between teachers' preparation to incorporate technology into the writing process (PITW) and their current use of AI to support writing instruction (AIW). Item-level analyses were performed by aligning corresponding elements of the writing process, brainstorming, drafting, editing/revising, and publishing, from two subscales: PITW and AIW, which allowed for comparison of teacher responses across matched instructional stages. Independent Samples T-Tests were used to determine if standalone technology courses, standalone writing courses, and one-to-one classroom devices impact the use of AI in the writing process. Finally, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to determine the main effects of a standalone technology course, a standalone writing course, and being in a one-to-one classroom, as well as their interaction effects, on teachers' use of AI for writing instruction.

Results

This study investigated teachers' self-rated abilities to integrate AI into their writing instruction, as measured by the PIWTSE-T, a five-point Likert scale. Survey items are presented in Table 3. Most teachers agreed that they were prepared to teach writing (M = 3.76), positively perceived their abilities to integrate technology into writing instruction (M = 3.69), and were using AI for student supports (M = 3.53). Teachers expressed a neutral stance on their preparedness to integrate technology into their teaching (M = 3.45) and into writing instruction (M = 3.19). They neither agreed nor disagreed with statements regarding the current use of AI to support their teaching practices (M = 2.97) or for integrating it into writing instruction (M = 2.63). To sum up, this study found that special education teachers are not using AI to support their writing instruction. In the following sections, we explore each research question further to understand the extent of AI integration in writing instruction, the predictors of its use, and the factors that contribute to its use.

RQ1: integration of AI into teaching the writing process

Findings reveal most teachers are not using AI in the writing process (M = 2.63; MDN = 2.75; SD = 1.42). Looking more closely at the various components of the writing process, 33.8% of surveyed teachers indicated they do not integrate AI into brainstorming (n = 367, M = 2.71, MDN = 3.00; SD = 1.58), with 119 respondents sharing they do to some extent and 64 sharing they strongly agree with the statement. Most respondents (n = 147) reported not using AI during the drafting and text generation phase (n = 366, M = 2.69; MDN = 2.00; SD = 1.60), with 147 strongly disagreeing and 37 disagreeing. Survey participants' ratings revealed that 144 (n = 372) are not using AI for editing and revising (M = 2.71; MDN = 2.00; SD = 1.61). Eighty-five respondents agreed that they used AI in editing and revising, with 68 strongly agreeing. Finally, the survey results indicate that 163 teachers reported seldom using AI for publishing (n = 364; M = 2.41; MDN = 2.00; SD = 1.51). Sixty-three teachers shared they agreed with the statement regarding AI use, and 48 strongly agreed. In summary, most respondents are not using AI in the writing process. Complete results are presented in Table 3.

RQ2: attitudes and preparation for integrating AI into writing instruction

The multiple regression model was designed to determine the current use of AI to support student learning, current use of AI for teacher practices, teachers' preparation to integrate technology into their teaching, teachers' preparation to teach writing, teachers' preparation to incorporate technology into writing instruction, and how they perceive their abilities to integrate technology into writing instruction collectively influence their use of AI in instruction of the writing process (see Table 6). The overall model was statistically significant, F(6, 360) = 68.14, p < 0.001. The model explained 53.2% of the variance in the use of AI tools in the writing process, R2 = 0.53, Adj. R2 = 0.52, indicating a large effect size (f2 = 1.14). Of the predictors included in the model, the AITP (β = 0.45, t = 8.68, p < 0.001), AISS (β = 0.18, t = 3.71, p < 0.001), and PITW (β = 0.18, t = 3.62, p < 0.001) were all statistically significant contributors. For example, AITP had an unstandardized coefficient of B = 0.47 (95% CI [0.37, 0.58]), indicating that for each one-unit increase in AITP, predicted AI tool use increased by 0.47 units, holding other variables constant. The other predictors did not significantly contribute to the model: PITT (β = 0.48, t = 0.93, p = 0.36), PITWR (β = 0.69, t = 1.51, p = 0.13), and PTW (β = 0.01, t = 0.28, p = 0.78).

Visual inspection of the residual scatterplot suggested heteroscedasticity, as it showed a clear funnel shape, rather than random scatter. This means the homoscedasticity assumption was not fully met. The absence of strong curvature in the scatterplot suggests that the linearity assumption was reasonably met, although the heteroscedasticity pattern warrants caution in interpreting standard errors. The Normal P-P plot showed that the residuals closely followed a straight line, and the histogram displayed an approximately normal distribution, supporting the normality assumption. The Durbin-Watson statistic was 1.88, indicating no evidence of autocorrelation. This means that the regression residuals are independent. Multicollinearity diagnostics (VIF and tolerance) were within acceptable ranges, indicating no multicollinearity concerns.

Variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged from 1.33 to 2.07, and tolerance values were all above 0.48, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern in the model. The PITT had a VIF of 2.07 and a tolerance of 0.48, indicating low multicollinearity. The PTW had a VIF of 1.33 and a tolerance of 0.75, indicating low multicollinearity. The PITW had a VIF of 1.98 and a tolerance of 0.51, indicating low multicollinearity. PITWR with Technology had a VIF of 1.63 and a tolerance of 0.61, indicating low multicollinearity. The Perceptions and Implications of AI had a VIF of 2.07 and a tolerance of 0.48, indicating low multicollinearity. Finally, the Use of AI in Teaching and Learning had a VIF of 1.77 and a tolerance of 0.57, indicating low multicollinearity. These predictors contributed uniquely to the model, allowing the regression coefficients to be interpreted with confidence. In other words, given that all tested variables had low VIFs and low multicollinearity, each variable is unique and independent of the others. Additionally, the regression coefficient is more stable and reliable. Overall, teachers' attitudes toward AI were the strongest predictor of AI tool use, followed by their integration of AI into student support and writing instruction (see Table 6 for regression coefficients, including unstandardized and standardized estimates, standard errors, and confidence intervals).

RQ3: factors that influence use of AI in the writing process

A regression analysis showed that significant predictors of special education teachers' use of AI in writing instruction were the use of AI to support student learning (AISS), teachers' use of AI to support their teaching practice (AITP), and their preparation to integrate technology into writing (PITW), explaining 53% of the variance. These data were further explored using Pearson and Spearman rank-order correlations, an Independent Samples T-Test, and an ANOVA.

A Pearson correlation showed a strong, positive, statistically significant relationship between the use of AI in the writing process and the use of AI in teaching (r = 0.67, p < 0.001) and the use of AI in teaching and learning (r = 0.54, p < 0.001), meaning that those that think AI is an essential topic in teaching and learning are more likely to integrate AI into the writing process (see Table 7). Statistically significant, moderate, positive relationships exist between the use of AI in the writing process and PITW (r = 0.41, p < 0.001), PITT (r = 0.41, p < 0.001), and PITWR (r = 0.48, p < 0.001). In other words, special education teachers who are prepared to integrate technology into their teaching and the writing process, and who are confident in their ability to do so, are more likely to integrate AI into their writing instruction. A statistically significant, weak relationship exists between the integration of AI into writing instruction and the PTW (r = 0.27, p < 0.001). This means that special education teachers who are prepared to teach writing are more likely to integrate AI into writing instruction.

All correlations were statistically significant and positive. There was a weak association between PITW brainstorming and AIW brainstorming (ρ = 0.39, p < 0.001), PITW drafting and AIW drafting (ρ = 0.25, p < 0.001), and PITW editing/revising was associated with AIW editing/revising (ρ = 0.37, p < 0.001). There was a statistically significant, moderate, positive relationship between the PITW and AIW publishing processes (ρ = 0.42, p < 0.001). This indicates a relationship between teachers who were trained to integrate technology into writing instruction and those who are using AI in their writing instruction.

After that, we focused on specific course preparation efforts to determine whether standalone writing or technology courses affect the use of AI in writing instruction. Independent Samples T-Tests showed that taking standalone writing t(348) = 7.11, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 1.33, or technology courses t(348) = 5.10, p < 0.001, Cohen's d = 1.37, have a statistically significant impact on AI use in the writing process, with very large effect sizes. Then, we explored the effect that having one-to-one devices in their classrooms had on the use of AI in writing instruction. Independent-samples t-tests found that this did not have a statistically significant impact on the use of AI in writing instruction, t(346) = −0.49, p = 0.62, Cohen's d = 1.42.

The ANOVA found that the overall model was statistically significant, F(7, 340) = 10.80, p < 0.001, explaining 18.2% of the variance in AI use for writing instruction. Main effects for both standalone technology courses [F(1, 340) = 15.40, p < 0.001] and standalone writing courses [F(1, 340) = 4.46, p = 0.035] were statistically significant, indicating that both types of preparation independently influence a teacher's use of AI in writing instruction. The interaction between taking a standalone technology course and having a one-to-one classroom was also statistically significant [F(1, 340) = 6.93, p = 0.009]. The effect of technology preparation was small-to-moderate (η2 = 0.04). In contrast, the effect of writing preparation was small (η2 = 0.01). The effect of the interaction of having a standalone technology course and having a one-to-one classroom was small (η2 = 0.01). This suggests that the positive effect of having a standalone technology course in their teacher preparation coursework on a teacher's use of AI in writing instruction is significantly influenced by their access to classroom devices. The remaining interaction terms were not statistically significant. These data are presented in Table 8.

Discussion

This study investigated the link between special education teachers' pre-service training in writing and technology and their self-reported integration of AI into their writing instruction. Survey results indicated that teachers feel moderately prepared for writing instruction and integrating technology, yet they report limited use of AI. These findings help determine if foundational training influences their use of innovative technologies like AI. This pattern reflects broader trends in AI-in-education research: teachers report interest and perceived value, but challenges related to preparedness, confidence, ethical concerns, and contextual barriers inhibit classroom integration (Celik et al., 2022; Meylani, 2024; Walter, 2024). The study's findings, therefore, underscore the field's recognition that teacher readiness, not tool availability, is the primary driver of meaningful AI implementation.

The extent of AI use in the writing process

Results from research question 1 revealed that most teachers do not use AI throughout the writing process. Nearly 40% of respondents strongly disagreed with statements about the use of AI in instruction for drafting, editing, revising, and publishing. Given the novelty of AI in education, these results are not surprising. While the promise of AI-supported tools to impact student writing outcomes may be new, researchers have been praising the use of other educational technologies (e.g., interactive graphic organizers, word prediction software) to support and improve writing outcomes for individuals with learning disabilities for decades (Edyburn, 2001; Little et al., 2018). Thus, to understand why our data show such limited use, it would make sense to step back within the educational technology spectrum to examine how teachers are prepared to use these more thoroughly researched tools, which should be permeating teacher preparation coursework. While the corpus of literature indicates that increased access to technology in K-12 special education classrooms is not translating to improved preparation efforts (Regan et al., 2019), participants in this current study felt somewhat positive about their preparation to integrate technology into writing instruction. Recent data on the integration of technology into writing indicates that the most common use of these tools is typing and word processing (Flanagan et al., 2024), specifically during the publishing stage (Regan et al., 2019). Our survey explicitly excludes the use of technology simply for typing and word processing from the definition of technology integration, which may explain why teachers showed the lowest agreement with that statement.

Additionally, surveying practicing teachers about their integration of AI into the writing process assumes they are spending time providing evidence-based writing instruction. Research continues to show, however, that teachers are not providing this instruction to struggling writers (Graham, 2019). Most teachers report spending only 15 min a day on teaching writing (Brindle et al., 2016; Gilbert and Graham, 2010), which is well below the recommended 1 h (Graham, 2019). Reasons for this include a lack of time, resources, and training (Alston and Eagle, 2024). Given the limited writing instruction occurring in today's classrooms, it is difficult to determine if participant ratings reflect a lack of AI integration or an absence of structured, process-based writing instruction.

Finally, our quantitative results demonstrate that teachers' preparation to teach writing and to integrate technology are both related to how they use AI across different stages of the writing process (e.g., brainstorming, drafting, revising, publishing). This aligns with research showing that AI integration depends heavily on foundational instructional knowledge, digital literacy, and pedagogical content knowledge (Yue et al., 2024; Rachbauer et al., 2025). Teachers in this study reinforce the literature's claim that AI literacy is now a prerequisite for leveraging generative tools effectively (Walter, 2024). Without a grounding in evidence-based writing instruction, AI tools risk being used superficially rather than to improve students' writing outcomes.

Predictors of integrating AI into writing instruction

Results from research question 2 found that teachers' use of AI for writing instruction is primarily shaped by their views on AI's usefulness and by their training in integrating technology into writing instruction. Consistent with existing research on the perceived benefits of AI for teachers, specifically its potential to save time, assist with curricular design, and personalize learning (Alwaqdani, 2025; Chounta et al., 2022), the use of AI for student support was identified as the second strongest predictor of AI integration into writing instruction. As this finding is supported by our participants' moderate agreement with the AI for student support subtest, it suggests that teachers who are trained to integrate technology into writing instruction are more likely to utilize AI to support their students' learning outcomes. While teachers may access these devices in their personal lives (e.g., social media, email) and professional lives (e.g., Learning Management Systems, digital textbooks), this does not necessarily mean they know how to use them effectively in their teaching. Therefore, it is essential to continue teaching pre-service teachers how to integrate technology into their instruction in a meaningful way.

Despite being the strongest predictor, the use of AI for the teaching profession had the second-lowest mean score among all subtests. Participants recognized the importance of students using AI, yet were more apprehensive about its use in supporting their own professional needs. Current research suggests that these apprehensions frequently stem from a fear of losing their jobs and being replaced by AI (Ng et al., 2023), ethical concerns (Graham et al., 2025), and a lack of training in utilizing AI for these tasks (Langreo, 2024). This suggests that, to improve the integration of AI into the writing process, teachers need to be exposed to its use in supporting their own tasks, as a lack of familiarity with AI tools is a significant barrier to their adoption in the classroom (Walter, 2024).

The findings also reinforce that PD is essential for building teacher capacity. Teachers' limited use of AI in writing instruction reflects gaps in PD on both writing and technology integration (Zimmer and Matthews, 2022). The broader literature emphasizes that effective AI-related PD must include: (a) explicit instruction in AI literacy, digital ethics, and privacy; (b) hands-on, practice-based learning; (c) ongoing coaching and collaborative support; and (d) alignment to local instructional contexts (Brandão et al., 2024; Jambunathan, 2025; Al-Ali and Miles, 2025). The study also aligns with findings that indicate technology-related PD must be customized and responsive to differing teacher needs and levels of knowledge (Kitcharoen et al., 2024; Aljemely, 2024).

Factors influencing teachers' use of AI in the writing process

The final research question analyzed the factors that influence a teacher's use of AI in the writing process. Varying degrees of positive relationships were found between the use of AI in the writing process and (1) the use of AI in Teaching Practices, (2) the use of AI for Student Support, (3) the preparation to integrate technology into writing, (4) the preparation to integrate technology, (5) a teachers attitudes and perceptions about their abilities to integrate technology into writing instruction, and (6) the preparation to teach writing.

Our analysis suggests that having a dedicated technology course, a dedicated writing course, and/or teachers' access to classroom devices results in a more statistically significant interaction with AI in the writing process than each source alone. Surprisingly, the interaction between AI use in the writing process and having one-to-one devices alone does not appear to affect usage. In fact, 90% of our respondents reported having one device per student in their classrooms, yet access to one-to-one devices was not a statistically significant factor in the use of AI in writing instruction. Our results align with existing research suggesting that an increase in classroom technology availability is not correlated with greater meaningful and effective use (Rowland et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2020; Harcourt, 2021).

With the increase in these technologies and their implications for classroom instruction and student learning, one might assume that greater availability leads to effective implementation and instructional use. Based on our findings, this assumption is false. Results suggest that the positive effect of having one-to-one devices in the classroom may not be realized without standalone technology or writing coursework. These findings highlight a missed opportunity to capitalize on the unique affordances of innovative technologies to support struggling writers, underscoring the need for a more meaningful integration that leverages their full potential. Furthermore, teachers continue to require explicit, intentional instruction in higher education on how to effectively use and integrate classroom devices into their writing instruction, thereby shaping their use of AI in writing instruction.

One challenge with the significance of standalone technology coursework is that preparation programs are moving away from these courses toward a more integrated approach. These integrated courses increase opportunities to implement course material in classroom experiences (Falloon, 2020). While research shows that the lack of practical experience in standalone courses hinders effective technology-integration training, our results indicate that the benefits of standalone courses may outweigh these drawbacks. In these standalone courses, teachers have the opportunity to build confidence in their use of technology (Falloon, 2020), more thoroughly explore emerging technologies, and understand best practices for technology integration. The programmatic approach to technology integration may be a positive step toward more intentional and impactful usage; however, our data suggest that this change may inadvertently hinder the integration of AI into the writing process.

In addition to the need for a technology course, our findings also point to the importance of standalone writing courses on the integration of AI into the writing process. However, very few preparation programs offer standalone writing methods courses (Flanagan et al., 2024). In fact, less than half of the high-incidence special education teacher preparation programs in the U.S. offer writing instruction coursework as either a standalone course or as an embedded component of other literacy-based classes (Brenner and McQuirk, 2019). While this lack of coursework in writing may explain why teachers feel underprepared to teach writing, it can also add to the discussion of why these courses are absent from preparation programs. In line with K-12 teachers' feelings, teacher-educators also report not feeling prepared to instruct pre-service teachers in writing instruction. Suppose the teacher-educators, who are supposed to be preparing future special education teachers, are avoiding teaching writing because they feel underprepared. How are pre-service teachers going to gain the skills and confidence necessary to teach writing when they have their own classrooms? Our findings reveal that instruction in standalone writing courses directly influences the use of AI in writing. If access to technology, and by extension AI, has the potential to impact student writing outcomes directly, it is paramount to offer evidence-based and high-quality writing methods courses.

Limitations

This study provides a snapshot of current AI use among special education teachers and examines its relationship with their preparation programs. The cross-sectional design limits causal inference because it cannot track changes over time, a characteristic of a longitudinal study. Additional limitations of this study, common to survey research, include volunteer bias, in which only highly interested or passionate individuals participate (Marcus and Schütz, 2005), and social desirability bias, in which respondents tend to answer in ways they believe are expected (Rosenthal and Rosnow, 2009). The compensation may also have influenced participation patterns. Since this survey collected teachers' self-reported preparation and use of AI in writing instruction, there was no way to verify the accuracy of their reported experiences or the extent of their AI integration. Future studies should aim to validate this self-reported data by analyzing submitted AI-integrated lesson plans or conducting follow-up interviews.

Participants may have been affected by survey fatigue due to the length of the pilot survey, which can cause people to stop before finishing and lead to a high rate of incomplete surveys (Ghafourifard, 2024). It is essential to acknowledge that, while the inclusion criteria required all participants to be high-incidence special education teachers, some respondents may not have been truthful in their responses. The likelihood of this increases because compensation was offered to survey finishers.

The final limitation concerns the survey's configuration in Qualtrics, where open-ended questions were used instead of a more effective multiple-choice format to collect course data. This lack of standardization led to inconsistent data, preventing reliable analysis. Responses lacked consistency, ranging from specific subject titles (e.g., “writing”) and broad discipline names (e.g., “ELA” or “Language Arts”) to vague student group labels (e.g., “varying exceptionalities”).

Recommendations for the future of teacher preparation and professional development

There are several implications for the future of teacher preparation based on this study's findings. First and foremost, to increase the use of AI in the writing process, teachers should receive adequate training in evidence-based writing instruction, including the use of technology. Teachers continually request training in both writing instruction and technology integration because of the proven benefits for SWDs. This points to two gaps in teacher preparation.

Teachers need additional support in integrating technology into their classrooms. With the rapid evolution of technology, the sheer volume of new tools, and continued advances in research, teachers need more and continued opportunities to learn about and practice with these technologies than could be offered in their preparation programs. Instead, teacher preparation programs and school districts should consider offering regular PD, led by both technology integration researchers and classroom teachers, on new and innovative technologies, considerations for their classroom use, and use cases for effective implementation and integration.

The second gap is the availability of evidence-based writing instruction in teacher preparation programs. There is a pressing need to provide teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to teach SWDs to write. However, there is a shortage of teacher-educators with expertise in writing instruction. As such, efforts to provide teachers with evidence-based writing instruction to further improve writing outcomes for SWDs could include integrating virtual coaching and simulated practice.

By prioritizing ongoing, collaborative PD and training in technology and writing, teachers will be better equipped to leverage AI and other innovations that can truly impact student outcomes, particularly those of SWDs. With the advancement of AI technologies, such as personalized chatbots, teacher preparation programs can collaborate to develop and refine models explicitly designed to train teachers to deliver evidence-based writing instruction (Beyer and Arndt, 2024). This will allow all teachers to receive evidence-based writing training, regardless of the course offerings in their training program. PD in technology integration for writing instruction, including virtual coaching and simulations, has meaningful potential to improve student writing outcomes and warrants further exploration (Zimmer and Matthews, 2022).

As for the integration of AI into writing instruction, widespread adoption is hindered by the fact that schools, districts, and states are still navigating the ethical and privacy implications of its use. Even with emerging state-level AI policies, many districts are still developing PD to guide teachers on the ethical, responsible use of AI, relevant policies, and tool integration. Teachers are often required to locate relevant tools independently, self-train on their use, and integrate them into existing classroom workflows. Therefore, future PD and pre-service training must prioritize instruction on high-quality, ethical, and safe AI use, accompanied by open discussions among educators and administrators about AI's impact on instruction and specific site needs.

Recommendations for the future of research

Given that so many teachers cite a lack of preparation in writing, an absence of writing coursework, and limited expertise in writing instruction, research should explore alternative methods to support teachers in writing instruction. This includes developing research-based Retrieval-Augmented Generation AI systems trained to be virtual writing coaches. This would allow both teachers and teacher educators to gain the knowledge and confidence needed to teach this critical skill.

Future research should further explore the findings of this quantitative study through a qualitative lens. The Likert scale, while allowing for hundreds of responses, does not capture the nuances or the rationale behind respondents' ratings. Through focus groups and interviews, researchers will better understand the teachers who have adopted AI practices, including the tools they use, how they implement them, and where they find and learn about them. Additionally, it is also critical to include teachers who are not integrating AI into their writing instruction to understand their rationale (e.g., uncertainty about where to learn about AI, fear of AI, etc.) and the training and support they need to begin implementing it. Identifying these data will inform the field about the key components necessary for high-quality, effective AI-integration training for educators.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, research into AI and writing should continue to explore the available tools and how they can be used to support struggling writers. Results from this study indicate that teachers' integration of AI into the writing process is currently limited. More research is needed to explore the various AI-supported technologies available and how they can be used during the writing process to improve student outcomes. Additionally, research should develop and validate tools that equip students with high-quality, evidence-based writing components to improve writing outcomes. The potential to leverage AI not only to support teacher development in writing instruction but also to personalize and extend the supports available to struggling writers is too great not to pursue further research.

Conclusion

This research aims to expand the current literature on teacher preparation and AI integration by determining how pre-service preparation influences the use of AI as a writing support for students. This study established the current extent of AI integration in writing instruction for struggling writers and identified factors in pre-service teacher preparation and classroom technology that predict its use. Findings add to the ongoing conversation about how technology, particularly AI, can be both a valuable resource and a frustrating challenge for special education teachers. To address the findings, teachers need training focused on integrating AI and, more broadly, educational technology into writing instruction. This training includes knowing which technology tools are effective and how to teach students to implement these tools to support their learning outcomes, as well as high-quality training in evidence-based writing practices. AI has the potential to augment the writing process and provide new and innovative tools to support struggling writers in expressing their knowledge, understanding, and ideas, with proper training and ongoing PD.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University of Kansas Institution Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SG: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. SS: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft. AC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported in part by a grant received from the Office of Special Education Programs [H327S240022].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Generative AI assisted with editing and revision, and provided procedural guidance for SPSS.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

AI for Education (2025). State AI Guidance for K12 Schools. Available online at: https://www.aiforeducation.io/ai-resources/state-ai-guidance (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Al-Ali, S., and Miles, R. (2025). Upskilling teachers to use generative artificial intelligence: the TPTP approach for sustainable teacher support and development. Austral. J. Educ. Technol. 41, 88–106. doi: 10.14742/ajet.9652

Aljemely, Y. (2024). Challenges and best practices in training teachers to utilize artificial intelligence: a systematic review. Front. Educ. 9:1470853. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1470853

Alston, C. L., and Eagle, J. L. (2024). Squeezed in: writing instruction over time. J. Literacy Res. 56, 190–212. doi: 10.1177/1086296X241266854

Alwaqdani, M. (2025). Investigating teachers' perceptions of artificial intelligence tools in education: potential and difficulties. Educ. Inf. Technol. 30, 2737–2755. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12903-9

Anderson, S. E., and Putman, R. S. (2020). Special education teachers' experience, confidence, beliefs, and knowledge about integrating technology. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 35, 37–50. doi: 10.1177/0162643419836409

Batorowicz, B., Missiuna, C. A., and Pollock, N. A. (2012). Technology supporting written productivity in children with learning disabilities: a critical review. Can. J. Occup. Ther. 79, 211–224. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2012.79.4.3

Beyer, S., and Arndt, K. (2024). Teachers' perceptions of a Chatbot's role in school-based professional learning. Open Educ. Stud. 6:20240015. doi: 10.1515/edu-2024-0015

Brandão, A., Pedro, L., and Zagalo, N. (2024). Teacher professional development for a future with generative artificial intelligence – an integrative literature review. Digital Educ. Rev. 45, 151–157. doi: 10.1344/der.2024.45.151-157

Brenner, D., and McQuirk, A. (2019). A snapshot of writing in elementary teacher preparation programs. New Educ. 15, 18–29. doi: 10.1080/1547688X.2018.1427291

Brindle, M., Graham, S., Harris, K. R., and Hebert, M. (2016). Third and fourth grade teacher's classroom practices in writing: a national survey. Read. Writ. 29, 929–954. doi: 10.1007/s11145-015-9604-x

Bushweller, K. (2025). Is there a healthy middle ground on AI in schools? Try skeptical optimism. Education Week. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/technology/is-there-a-healthy-middle-ground-on-ai-in-schools-try-skeptical-optimism/2025/09 (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Celik, I., Dindar, M., Muukkonen, H., and Järvelä, S. (2022). The promises and challenges of artificial intelligence for teachers: a systematic review of research. TechTrends 66, 616–630. doi: 10.1007/s11528-022-00715-y

Chounta, I. A., Bardone, E., Raudsep, A., and Pedaste, M. (2022). Exploring teachers' perceptions of artificial intelligence as a tool to support their practice in Estonian K-12 education. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 32, 725–755. doi: 10.1007/s40593-021-00243-5

Colón, A. M. O., Rus, T. I., Moreno, J. R., and Montoro, M. A. (2023). TPACK model as a framework for in-service teacher training. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 15:ep439. doi: 10.30935/cedtech/13279

Congressional Research Service (2020). The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act: A Comparison of State Eligibility Criteria. Available online at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46566 (Accessed December 03, 2025).

Diliberti, M. K., Lake, R. J., and Weiner, S. R. (2025). More districts are training teachers on artificial intelligence: Findings from the American School District Panel (Research Report No. RR-A956-31). RAND Corporation. Available online at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA956-31.html (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Edyburn, D. L. (2001). 2000 in review: a synthesis of the special education technology literature. J. Spec. Educ. Technol. 16, 5–25. doi: 10.1177/016264340101600201

Falloon, G. (2020). From digital literacy to digital competence: the teacher digital competency (TDC) framework. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 2449–2472. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09767-4

Finlayson, K., and McCrudden, M. T. (2020). Teacher-implemented writing instruction for elementary students: a literature review. Read. Writ. Q. 36, 1–18. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2019.1604278

Flanagan, S. M., Miller, K. M., and Lee, J. Y. (2024). Special education teachers' writing instructional practices. Read. Writ. Q. 41, 218–235. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2024.2413992

Foulger, T. S., Graziano, K. J., Schmidt-Crawford, D., and Slykhuis, D. A. (2017). Teacher educator technology competencies. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 25, 413–448.

Freedman, S. W., Hull, G. A., Higgs, J. M., and Booten, K. P. (2016). Teaching writing in a digital and global age: toward access, learning, and development for all. Handb. Res. Teach. 5, 1389–1450. doi: 10.3102/978-0-935302-48-6_23

Galiatsos, S., Kruse, L., and Whittaker, M. (2019). Forward together: helping educators unlock the power of students who learn differently. Natl. Center Learn. Disabil.

Ghafourifard, M. (2024). Survey fatigue in questionnaire based research: The issues and solutions. J. Caring Sci. 13, 148–149. doi: 10.34172/jcs.33287

Gilbert, J., and Graham, S. (2010). Teaching writing to elementary students in grades 4–6: a national survey. Elem. Sch. J. 110, 494–518. doi: 10.1086/651193

Gillespie Rouse, A., Kiuhara, S. A., and Kara, Y. (2021). Writing-to-learn in elementary classrooms: a national survey of US teachers. Read. Writ. 34, 2381–2415. doi: 10.1007/s11145-021-10148-3

Goldman, S. R., Carreon, A., and Smith, S. J. (2024). Exploring the integration of artificial intelligence into special education teacher preparation through the TPACK framework. J. Spec. Educ. Prepar. 4, 52–64. doi: 10.33043/6zx26bb2

Graham, S. (2019). Changing how writing is taught. Rev. Res. Educ. 43, 277–303. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821125

Graham, S., Hsiang, T. P., Ray, A. B., Zheng, G., and Hebert, M. (2022). Predicting efficacy to teach writing: the role of attitudes, perceptions of students' progress, and epistemological beliefs. Elem. Sch. J. 123, 1–36. doi: 10.1086/720640

Graham, S., Skar, G. B., Kvistad, A. H., and Jeffery, J. V. (2025). Secondary teachers' use and beliefs about generative artificial intelligence and writing in school. Read. Writ. 1–31. doi: 10.1007/s11145-025-10699-9

Griffin, M., Martino, R. J., LoSchiavo, C., Comer-Carruthers, C., Krause, K. D., Stults, C. B., et al. (2021). Ensuring survey research data integrity in the era of internet bots. Qual. Quant. 1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11135-021-01252-1

Harcourt, H. M. (2021). 7th Annual Educator Confidence Report. Available online at: https://prod-hmhco-vmg-craftcms-private.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/2021-Educator-Confidence-Report.pdf?X-Amz-Content-Sha256=UNSIGNED-PAYLOAD&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIAJMFIFLXXFP4CBPDA%2F20251203%2Fus-east-1%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20251203T224001Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=3600&X-Amz-Signature=d3a29922f341493e9e779d6eb4fb342302954b8095845191519051a7d7f5445c (Accessed December 03, 2025).

Harris, K. R., and McKeown, D. (2022). Overcoming barriers and paradigm wars: powerful evidence-based writing instruction. Theory Pract. 61, 429–442. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2022.2107334

Jambunathan, S. (2025). Integrating artificial intelligence into early childhood teacher education. Contemp. Iss. Early Childhood. doi: 10.1177/14639491251340141

Johnson, A. M., Jacovina, M. E., Russell, D. G., and Soto, C. M. (2016). “Challenges and solutions when using technologies in the classroom,” in Adaptive Education Technologies for Literacy Instruction, 1st ed., eds. M. E. Jacovina, and D. G. Russell (New York, NY: Taylor & Francis), 18. doi: 10.4324/9781315647500-2

Kitcharoen, P., Howimanporn, S., and Chookaew, S. (2024). Enhancing teachers' AI competencies through artificial intelligence of things professional development training. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 18, 4–15. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v18i02.46613

Klein, A. (2024). Does your district ban ChatGPT? Here's what educators told us. Education Week. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/technology/does-your-district-ban-chatgpt-heres-what-educators-told-us/2024/02 (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Kong, S. C., and Yang, Y. (2024). A human-centered learning and teaching framework using generative artificial intelligence for self-regulated learning development through domain knowledge learning in K−12 settings. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 17, 1562–1573. doi: 10.1109/TLT.2024.3392830

Langreo, L. (2024). Most teachers are not using AI. Here's why. Education Week. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/technology/most-teachers-are-not-using-ai-heres-why/2024/01 (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Langreo, L. (2025). More teachers say they're using AI in their lessons. Here's how. Education Week. Available online at: https://www.edweek.org/technology/more-teachers-say-theyre-using-ai-in-their-lessons-heres-how/2025/03 (Accessed November 26, 2025).

Little, C. W., Clark, J. C., Tani, N. E., and Connor, C. M. (2018). Improving writing skills through technology-based instruction: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. 6, 183–201. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3114

Marcus, B., and Schütz, A. (2005). Who are the people reluctant to participate in research? Personality correlates of four different types of nonresponse as inferred from self-and observer ratings. J. Pers. 73, 959–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00335.x

Meylani, R. (2024). Artificial intelligence in the education of teachers: a qualitative synthesis of the cutting-edge research literature. J. Comput. Educ. Res. 12, 600–637. doi: 10.18009/jcer.1477709

Mishra, P., and Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 108, 1017–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x

Myers, J., Scales, R. Q., Grisham, D. L., Wolsey, T. D., Dismuke, S., Smetana, L., et al. (2016). What about writing? A national exploratory study of writing instruction in teacher preparation programs. Literacy Res. Instruct. 55, 309–330. doi: 10.1080/19388071.2016.1198442

Ng, D. T. K., Leung, J. K. L., Su, J., Ng, R. C. W., and Chu, S. K. W. (2023). Teachers' AI digital competencies and twenty-first century skills in the post-pandemic world. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 71, 137–161. doi: 10.1007/s11423-023-10203-6

Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A., Liao, J. Y. C., Sadik, O., and Ertmer, P. (2018). Evolution of teachers' technology integration knowledge, beliefs, and practices: how can we support beginning teachers use of technology? J. Res. Technol. Educ. 50, 282–304. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2018.1487350

Rachbauer, T., Graup, J., and Rutter, E. (2025). Digital literacy and artificial intelligence literacy in teacher training. Forum Educ. Stud. 3:1842. doi: 10.59400/fes1842

Regan, K., Evmenova, A. S., Sacco, D., Schwartzer, J., Chirinos, D. S., and Hughes, M. D. (2019). Teacher perceptions of integrating technology in writing. Technol. Pedagogy Educ. 28, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2018.1561507

Rodríguez Moreno, J., Agreda Montoro, M., and Ortiz Colon, A. M. (2019). Changes in teacher training within the TPACK model framework: a systematic review. Sustainability 11:1870. doi: 10.3390/su11071870

Rosenthal, R., and Rosnow, R. L. (2009). “The volunteer subject,” in Artifacts in Behavioral Research, 2009, 48–92.

Rowland, A., Smith, S. J., Lowrey, K. A., and Abdulrahim, N. A. (2020). Underutilized technology solutions for student writing. Interv. Sch. Clin. 56, 99–106. doi: 10.1177/1053451220914893

Taylor, D. B., Handler, L. K., FitzPatrick, E., and Whittingham, C. E. (2020). The device in the room: technology's role in third grade literacy instruction. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 52, 515–533. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2020.1747577

Troia, G. A., and Graham, S. (2016). Common core writing and language standards and aligned state assessments: a national survey of teacher beliefs and attitudes. Read. Writ. 29, 1719–1743. doi: 10.1007/s11145-016-9650-z

Voithofer, R., and Nelson, M. J. (2021). Teacher educator technology integration preparation practices around TPACK in the United States. J. Teach. Educ. 72, 314–328. doi: 10.1177/0022487120949842

Walter, Y. (2024). Embracing the future of Artificial Intelligence in the classroom: the relevance of AI literacy, prompt engineering, and critical thinking in modern education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. Higher Educ. 21, 1–29. doi: 10.1186/s41239-024-00448-3

Yau, K., Chai, C., Chiu, T., Meng, H., King, I., and Yam, Y. (2022). A phenomenographic approach on teacher conceptions of teaching artificial intelligence (AI) in K-12 schools. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 1041–1064. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11161-x

Yue, M., Jong, M. S. Y., and Ng, D. T. K. (2024). Understanding K−12 teachers' technological pedagogical content knowledge readiness and attitudes toward artificial intelligence education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 29, 19505–19536. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12621-2

Keywords: artificial intelligence, writing, teacher preparation, special education, professional development

Citation: Goldman SR, Smith SJ and Carreon A (2025) Special education teachers' use of AI to support students with disabilities in writing. Front. Educ. 10:1710974. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1710974

Received: 22 September 2025; Accepted: 20 November 2025;

Published: 10 December 2025.

Edited by:

Steve Graham, Arizona State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Angelique Aitken, The Pennsylvania State University (PSU), United StatesZoi Traga Philippakos, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, United States

Albert Li, University of California, Irvine, United States

Copyright © 2025 Goldman, Smith and Carreon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Samantha R. Goldman, c2FtYW50aGEuZ29sZG1hbkBrdS5lZHU=

Samantha R. Goldman

Samantha R. Goldman Sean J. Smith

Sean J. Smith Adam Carreon

Adam Carreon