- Department of Curriculum and Instruction, Faculty of Education, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia

The sustainable integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in education is crucial for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4). However, its potential is frequently undermined by a critical, often overlooked barrier: student resistance to technological change, which can hinder learning outcomes and derail the sustainable adoption of digital tools. This study investigates the potential of chatbots as a targeted intervention to mitigate this resistance among high school students. The research involved 52 first-year high school students from a school in Al-Ahsa, selected based on high levels of technology resistance. Using a randomized controlled pre-test/post-test design, participants were divided into an experimental group (n = 26), which interacted with a dedicated chatbot, and a control group (n = 26), which was exposed to traditional teaching methods about the technology. Conducted over two weeks during the 2024/2025 academic year, resistance was measured using a validated 17-item scale assessing four dimensions: routine adherence, emotional reactions, cognitive rigidity, and short-term thinking. Data were analyzed using independent samples t-tests. The analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction in overall technology resistance for the experimental group compared to the control group (t(50) = 11.21, p < 0.001), with a large effect size (d = 2.87). The findings offer clear practical implications. For schools, chatbots represent a scalable strategy to ease digital transformation; for teachers, they are a tool to reduce student anxiety and ease instructional transitions; and for students, they provide a low-stakes environment to build technological confidence. This study provides one of the first empirical evidence that chatbots can be a targeted intervention for reducing student resistance, thereby offering a practical mechanism for supporting the sustainable and frictionless integration of new technologies in line with national visions like Saudi Vision 2030.

1 Introduction

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) in education is a cornerstone of global efforts toward sustainable and equitable learning, as embodied by Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4). According to Celik et al. (2022), AI technology has undergone substantial development in the education sector, proving to offer numerous new opportunities and a positive impact on learning activities, fostering a more interactive and dynamic educational environment. Similarly, Dwivedi et al. (2023) note that with the rapid advancement of technological revolutions, AI has gained significant attention and widespread application across various fields.

However, its adoption presents a persistent paradox, particularly evident among high school students: while this generation are digital natives, many demonstrate significant resistance to pedagogical applications of technology (Selwyn, 2019; Zaky, 2023). This resistance creates a critical barrier to implementing educational innovations, undermining the potential for lasting technological integration. This challenge is especially salient in contexts of rapid digital transformation, such as that outlined in Saudi Vision 2030, which prioritizes the modernization of education as a key national objective.

This resistance to technological change can be understood through the lens of established frameworks that cite factors such as routine adherence, emotional reactions, and cognitive rigidity (Pfaltzgraf and Insch, 2021; Stevenson et al., 2020). Conversely, Social Constructivist Theory (Vygotsky, 1978) provides a compelling foundation for addressing this resistance, positing that learning is an active process where knowledge is constructed through social interaction and scaffolding. We propose that chatbots, as AI-powered conversational agents, are uniquely positioned to operationalize this theory to mitigate resistance. Their familiar, interactive interfaces can provide the low-stakes, personalized scaffolding, immediate feedback, and affective support necessary to reduce anxiety (addressing emotional reactions), guide users through new processes (overcoming cognitive rigidity and routine adherence), and make learning feel more accessible (countering short-term thinking) (Pérez et al., 2020; Smutny and Schreiberova, 2020).

A growing body of research explores the educational benefits of chatbots for learning outcomes and engagement (e.g., Deng and Yu, 2023; Wollny et al., 2021). However, these streams of research have not directly empirically tested the core proposition: whether the direct interaction with a chatbot can serve as an effective intervention to reduce students’ pre-existing resistance to technological change itself. This is a critical gap, as reducing initial resistance is a prerequisite for sustainable adoption. While studies have shown that chatbots can be engaging, we lack robust evidence that they can cause a reduction in the specific psychological dimensions of resistance.

To address this gap, the present study is guided by the following research question: What is the effect of using a chatbot-based intervention on reducing technological change resistance among high school students?

This study aims to bridge this gap by investigating the efficacy of a chatbot intervention in mitigating resistance to technological change among high school students in Saudi Arabia. Using a randomized controlled trial, this research directly tests the hypothesis that interaction with a chatbot significantly reduces students’ levels of resistance, as measured across its core dimensions. The findings promise to offer valuable insights for educators and policymakers seeking to foster resilient and adaptive learning environments, thereby supporting the sustainable integration of technology in line with both national and global educational goals.

2 Literature review

2.1 Technological resistance in education: a barrier to sustainable integration

The integration of technology into education, while essential for progress, often encounters significant resistance from its key stakeholders. Resistance to technological change is defined as the hesitation or opposition to the adoption of new technological tools, systems, or procedures (Yılmaz and Kılıçoğlu, 2013; Șerban et al., 2020). This resistance presents a major barrier to achieving sustainable educational development goals, including those outlined in Saudi Vision 2030, which emphasizes digital transformation as a national priority (National Transformation Program, 2020; Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA), 2025).

To understand this phenomenon, it is crucial to examine its underlying dimensions. Stewart et al. (2009) provide a foundational framework, identifying four key dimensions of resistance:

• Routine adherence: A preference for familiar methods and a reluctance to alter established practices.

• Emotional reactions: Feelings of anxiety, stress, or frustration triggered by the change.

• Cognitive rigidity: A fixed mindset and unwillingness to acquire new knowledge or skills.

• Short-term thinking: A focus on the immediate effort required rather than the long-term benefits.

This resistance is particularly nuanced and multi-layered in the Saudi educational context. A persistent paradox exists where students, despite being digital natives, frequently resist educational technologies that appear rigid, misaligned with their learning preferences, or lacking meaningful human interaction (Selwyn, 2019; Zaky, 2023). Conversely, teachers often exhibit reluctance due to concerns about increased workload, inadequate professional development, and perceived threats to pedagogical autonomy (Barak, 2018; Crompton et al., 2022). Recent studies highlight that educators’ willingness to engage with AI tools is further shaped by complex factors such as trust dynamics, ethical considerations, and the extent of institutional support (Cukurova et al., 2023).

The Saudi context adds unique cultural and infrastructural layers to this challenge. National initiatives led by the Ministry of Education and Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (2025) actively promote AI integration, yet implementation is uneven. Urban schools may face resistance rooted in pedagogical misalignment, while rural schools often grapple with infrastructural challenges that amplify perceptions of impracticality (Abdel-Moula and Al-Ayyeb, 2021). Furthermore, cultural and religious perspectives that emphasize the humanistic nature of education can shape skepticism toward AI tools that appear to depersonalize learning, and concerns regarding data privacy are frequently cited by educators and parents alike (Selwyn, 2019; UNESCO, 2022). These factors collectively underscore that resistance is not merely a technical hurdle but a complex socio-cultural challenge that must be addressed for successful and sustainable technology integration.

2.2 Chatbots in education: pedagogical affordances for support and engagement

As educational institutions seek scalable solutions to overcome resistance and foster sustainable technology integration, AI-powered chatbots have emerged as a promising tool. Chatbots are conversational agents that use natural language processing to simulate human-like dialog, providing personalized academic support and guidance (Winkler and Söllner, 2018; Hobert, 2019). Their fundamental nature combines advanced algorithms with machine learning to create responsive, adaptive learning companions (Armstrong, 2022).

The pedagogical value of chatbots is strongly rooted in Vygotsky’s (1978) Social Constructivist Theory. They act as always-available tutors that provide dynamic scaffolding, guiding learners through their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) by breaking down complex tasks, offering hints, and delivering explanations (Al-Salk, 2016; Al-Najjar and Habib, 2021). Research by Al-Shenqiti (2022) has shown that this constant availability of support significantly reduces learning anxiety while increasing both technology acceptance and academic confidence.

This theoretical grounding translates into several key, empirically-supported affordances that are critical for enhancing the learning experience. These include 24/7 availability and self-paced interaction, which allows students to engage with material outside of classroom hours and supports differentiated instruction (Al-Shenqiti, 2022; Cunningham-Nelson et al., 2019). Furthermore, chatbots provide immediate and personalized feedback, helping to correct misunderstandings in real-time and structure learning experiences effectively (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019; Abdulghani, 2023). Their conversational interface also creates a low-stakes, private practice environment where students can ask questions without fear of social embarrassment, which is crucial for mitigating anxiety and fostering exploration (Adamopoulou and Moussiades, 2020). Finally, through structured guidance and engagement, chatbots help students navigate new processes via interactive dialogs, with the use of localized language and multimedia integration demonstrating remarkable success in boosting engagement and making learning more immersive (Pérez et al., 2020; Smutny and Schreiberova, 2020).

Empirical research, including meta-analyses by Deng and Yu (2023), confirms that these chatbot interventions significantly increase learning achievement and content retention. Consequently, chatbots are not merely information delivery systems but are interactive partners capable of creating more adaptive, supportive, and engaging learning environments—characteristics that are directly antithetical to the drivers of technological resistance.

2.3 Synthesizing the framework

Building upon the established understanding of technological resistance (Section 2.1) and the pedagogical affordances of chatbots (Section 2.2), this study proposes a conceptual framework that positions chatbots as a targeted intervention to mitigate student resistance. This synthesis is grounded in Vygotsky’s Social Constructivist Theory, which posits that learning is facilitated through social interaction and scaffolding within a learner’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) (Vygotsky, 1978; Al-Salk, 2016). Chatbots, as interactive agents, provide this essential scaffolding in a manner that directly addresses the core psychological dimensions of resistance.

The proposed conceptual framework explicitly maps the hypothesized relationships between specific chatbot affordances and the resistance dimensions they are theorized to mitigate. This model posits that the 24/7 availability and self-paced interaction of chatbots counter Routine Adherence by allowing students to engage with new technology outside the fixed structure of a traditional classroom, thereby reducing the pressure to abandon familiar routines (Al-Shenqiti, 2022; Cunningham-Nelson et al., 2019). Simultaneously, the low-stakes, private practice environment and the provision of immediate, personalized feedback mitigate Emotional Reactions by reducing anxiety and fear of judgment, thus fostering psychological safety (Adamopoulou and Moussiades, 2020; Al-Shenqiti, 2022). Furthermore, the structured guidance and scaffolding provided by chatbots help overcome Cognitive Rigidity by breaking down complex technological tasks into guided, conversational steps, making new knowledge and skills less daunting (Winkler and Söllner, 2018; Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). Finally, the efficiency and just-in-time support offered by chatbots address Short-Term Thinking by demonstrating the immediate utility and time-saving benefits of the new technology, shifting the student’s focus from initial effort to tangible advantages (Pérez et al., 2020; Smutny and Schreiberova, 2020). This direct mapping provides a testable model for how a chatbot intervention can effect behavioral change.

Therefore, this framework posits that interaction with a chatbot does not merely teach a skill but fundamentally alters the student’s experience of technological adoption. By making the process less threatening, more manageable, and immediately beneficial, the intervention is hypothesized to lead to a significant reduction in overall resistance.

2.4 Hypothesis development

Based on the synthesized theoretical framework above, the following hypotheses are formally proposed:

H1 predicted a between-groups difference post-intervention. It was formulated as follows:

H1: Participants in the experimental group who receive the chatbot intervention will show a significantly greater reduction in overall resistance to technological change than participants in the control group.

To provide a more nuanced understanding of this between-groups effect, the following sub-hypotheses pertaining to the specific dimensions of resistance were also proposed:

H1a: The chatbot intervention will lead to a significantly greater reduction in routine adherence compared to the control group.

H1b: The chatbot intervention will lead to a significantly greater reduction in emotional reactions compared to the control group.

H1c: The chatbot intervention will lead to a significantly greater reduction in cognitive rigidity compared to the control group.

H1d: The chatbot intervention will lead to a significantly greater reduction in short-term thinking compared to the control group.

H2 predicted a within-group change for the experimental group following the intervention. It was formulated as follows:

H2: Participants in the experimental group will show a significant reduction in overall resistance to technological change from pre-test to post-test.

To examine the within-group effect across the different dimensions, the following sub-hypotheses were also proposed:

H2a: The experimental group will show a significant reduction in routine adherence from pre-test to post-test.

H2b: The experimental group will show a significant reduction in emotional reactions from pre-test to post-test.

H2c: The experimental group will show a significant reduction in cognitive rigidity from pre-test to post-test.

H2d: The experimental group will show a significant reduction in short-term thinking from pre-test to post-test.

3 Materials and methods

3.1 Participants

The 17-item Resistance to Change Scale (adapted from Stewart et al., 2009)—scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree; total score range = 17–85)—was administered to all 98 first-year students. The population mean score was 43 (SD = 23.4), indicating a moderate level of technological-change resistance in this cohort. To focus the study on students exhibiting substantive resistance, only those scoring above the population mean (>43) were selected. This mean-cutoff classification is a validated approach in attitudinal and technology-adoption research when normative cutoffs are unavailable and aids in forming a more homogeneous sample (Tadese and Mihretie, 2021). The final sample comprised 52 students. Following selection, participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental (chatbot) or control (traditional instruction) groups (n = 26 each) using a computer-generated random number sequence to ensure a randomized controlled pre-test/post-test design.

This sampling strategy enhances internal validity by reducing variability in base-line resistance levels, though it may limit generalizability to students with lower or average resistance to technological change.

3.2 Research approach

This study belongs to the category of research that examines and tests causal relationships between variables. Given this objective (Thomas, 2024), the experimental methodology is one of the most suitable approaches for achieving this type of inquiry. Consequently, the present study employs an experimental design to ensure rigorous investigation. The independent variable in this research is the use of chatbots, while the dependent variable is students’ resistance to technological change.

3.3 Experimental treatment design and production

The development of an effective educational chatbot requires a rigorous instructional design approach grounded in established pedagogical principles. Following the systematic ADDIE model (Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, Evaluation) (Branch, 2009), this study implemented a comprehensive framework for creating an experimental chatbot treatment aimed at reducing technological resistance among learners.

3.3.1 Analysis phase

The analysis phase established three critical foundations for the chatbot’s development. First, the learning problem was precisely defined as investigating how chatbot integration affects technological resistance among first-year high school students in Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia, with particular attention to impacts on learning motivation and academic persistence. Second, detailed learner profiling was conducted, identifying students with shared developmental characteristics (cognitive, affective, and psychomotor) and comparable technological resistance levels, all without prior exposure to the HTML programming content. Third, a thorough resource assessment was performed, identifying essential technical requirements (Adobe Creative Suite, Telegram Bot API), infrastructure needs (computer lab with high-speed internet), and human resource considerations (the researcher conducting all development phases).

3.3.2 Design phase

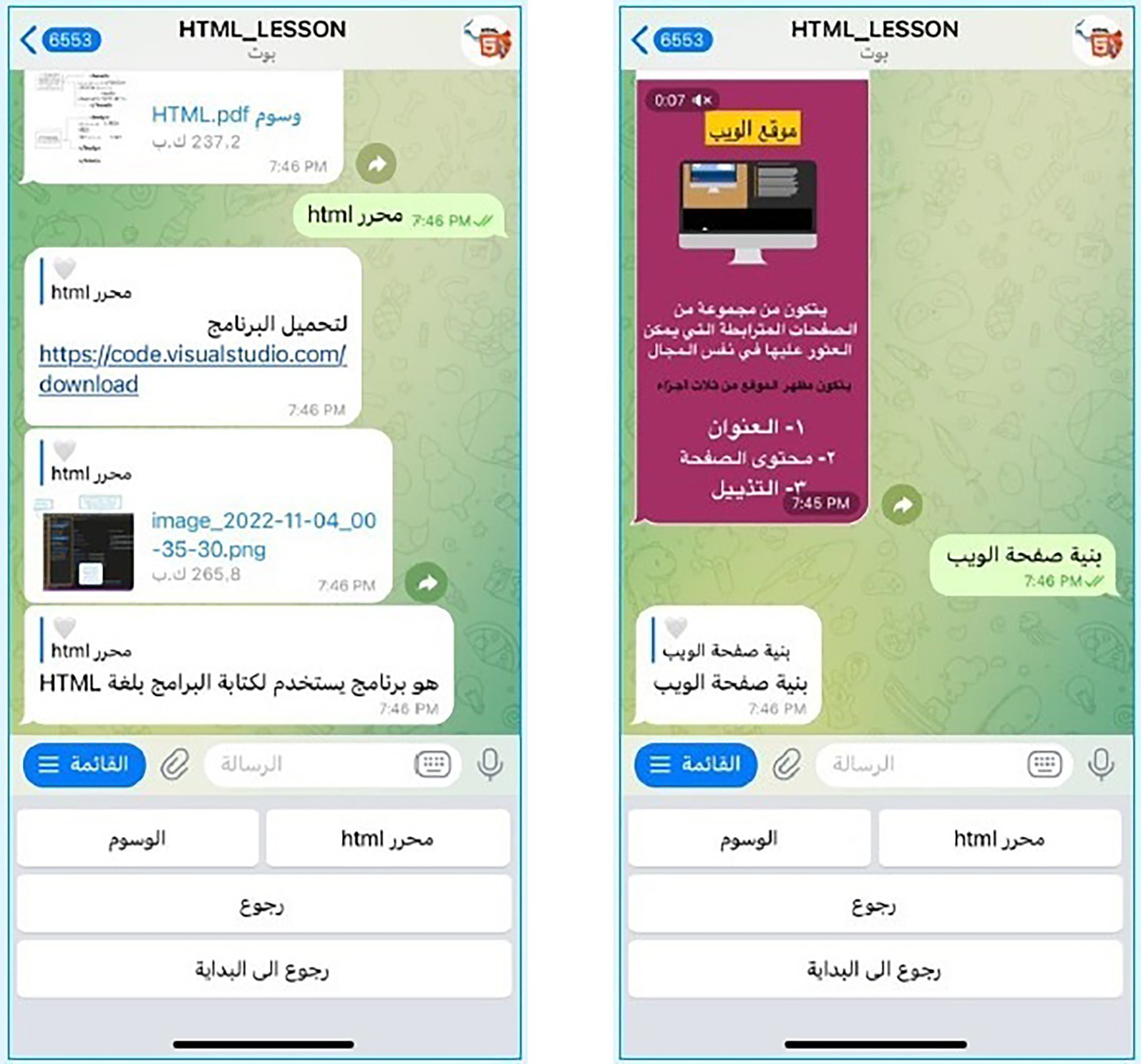

During the design phase, the instructional architecture was carefully constructed through multiple iterative processes. The researcher first derived specific learning objectives from the Digital Technology 1–1 curriculum, focusing on HTML programming concepts. These objectives underwent expert validation, achieving 93% inter-rater agreement before being organized into hierarchical learning tasks. Existing textbook material was then adapted for conversational delivery, maintaining a careful balance between theoretical and practical components while integrating multimedia elements. The interaction design employed screen-by-screen storyboarding to create a three-module structure (Website Creation, Content Structure, and Assessment) featuring button-based navigation and formative assessments through Wordwall integration.

3.3.3 Development phase

The development phase transformed these designs into a functional system through meticulous technical implementation. Multimedia components were created using Adobe Photoshop for graphics, Premiere Pro for video production, and Microsoft Word for textual content. These elements were then integrated into the Telegram Bot platform, creating a cohesive learning environment with modular content organization and responsive dialog flows (Figure 1). The developed chatbot underwent rigorous validation from educational technology experts during review confirming its readiness for application. Pilot testing further confirmed the system’s effectiveness, demonstrating 100% usability approval among test users, with only minor graphical refinements (font sizes, color schemes) required before final implementation.

3.3.4 Implementation phase

A detailed account of this stage will be provided in the section describing the execution of the pilot study.

3.3.5 Evaluation phase

A comprehensive formative evaluation completed the development process, incorporating feedback from all previous phases and the pilot study to ensure the chatbot’s pedagogical integrity and technical robustness. This systematic approach resulted in a validated educational chatbot specifically designed to measure technology resistance reduction while maintaining instructional effectiveness for the target Saudi learner population. The final product represented a carefully balanced integration of pedagogical principles and technological innovation, ready for deployment in the main experimental study.

3.4 Data collection

3.4.1 Development and validation of the Technology Change Resistance Scale

This study developed and validated a comprehensive scale to measure resistance to technological change (Figure 2) among first-year high school students. The instrument consists of carefully constructed statements requiring respondents to indicate their level of agreement using a five-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree). The scale was adapted from Stewart et al.’s (2009) resistance to change instrument, with modifications made to align with the specific technological context of this research. While this foundational protocol provided a validated framework for measuring resistance constructs (e.g., routine adherence, cognitive rigidity), the researchers acknowledge that technological advancements—particularly in AI and chatbots—may introduce nuances not fully captured by older instruments. To address this, our adaptation process included item rewording to reflect contemporary educational technology (e.g., replacing generic “technology” with “AI-driven tools”), expert validation focusing on relevance to chatbot interfaces (e.g., evaluating emotional reactions to non-human interaction), and pilot testing with students exposed to chatbots to ensure face validity for modern contexts. Despite these efforts, we recognize that rapid technological evolution may necessitate further scale refinements for future AI-specific studies (see Limitations, Section 7).

The scale’s theoretical foundation incorporates four key dimensions of resistance: adherence to routine (5 items), emotional reactions (4 items), cognitive rigidity (4 items), and short-term thinking (4 items). These dimensions collectively capture the multifaceted nature of technological resistance through 17 total items, including 15 positively-worded and 2 negatively-worded statements to mitigate response bias. Scoring follows standard Likert procedures, with positive items scored 5–1 (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree) and negative items reverse-scored 1–5 to ensure consistent interpretation.

To establish content validity, the scale underwent rigorous review by expert panels in educational psychology and instructional technology. These experts evaluated the instrument’s items for representativeness of the construct, dimensional alignment, linguistic precision, and overall appropriateness for the research objectives. The validation process yielded strong inter-rater agreement (94%), indicating excellent content validity. Based on expert feedback, minor wording refinements were implemented to enhance item clarity before pilot testing.

Reliability was assessed using the test–retest method with a two-week interval between administrations to the pilot sample. The Spearman-Brown correlation coefficient (Ahmed, 2014) demonstrated high temporal stability (r = 0.93), confirming the scale’s reliability for research purposes. In addition to temporal stability, the internal consistency of the scale was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha. The overall scale demonstrated excellent reliability (α = 0.91). The reliability for each sub-dimension was also strong: Routine Adherence (α = 0.87), Emotional Reactions (α = 0.85), Cognitive Rigidity (α = 0.83), and Short-Term Thinking (α = 0.82). Practical administration considerations were also addressed, with pilot testing indicating the instrument requires approximately 30 min for completion, making it feasible for implementation in school settings.

This psychometrically sound instrument provides the researcher with a valid and reliable tool for assessing students’ resistance to technological change, particularly in educational contexts where technology integration initiatives are being implemented. The scale’s development followed established measurement principles while addressing the specific needs of the target population, ensuring both scientific rigor and practical applicability.

3.4.2 Data collection procedure

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at King Faisal University (approval no. KFU-REC-2023-AUG-ETHICS1074) prior to the commencement of data collection. Informed consent was secured from all participants and their guardians. The students were divided into two groups according to the experimental research design. The Technology Change Resistance Scale was administered as a pre-test to measure their resistance to technological change, and their scores were recorded to ensure homogeneity between the experimental and control groups. These scores were later used to calculate gain scores. The scale was administered separately to each group, with students instructed to read the guidelines carefully, and any questions were addressed during the session.

The experimental group followed the same procedures as the pilot study, except that the Technology Change Resistance Scale was allotted 30 min. Meanwhile, the control group received instruction through the traditional lecture-based method in the computer lab.

For the main experiment, the researcher first held an introductory session in the computer lab with the experimental group to explain the study’s purpose, the use of chatbot, and strategies for interacting with it. Students then received an email with a link to join the Telegram-based chatbot and were instructed to download the app, join the bot, and use it to study the HTML programming module. In contrast, the control group was taught HTML programming using the conventional lecture method in the computer lab. After the experimental intervention, the Technology Change Resistance Scale was administered as a post-test to both groups. The experiment was conducted over 2 weeks during the first semester of the 2024/2025 academic year, from October 30 to November 10, 2024. Upon completion, the researcher compiled the post-test resistance scores for statistical analysis.

3.5 Data analysis plan

All quantitative data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29). The analysis followed a structured workflow. First, the dataset was screened for missing values and outliers; no missing data were found, and no extreme outliers (z > ±3.29) were identified that required removal (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2019). Subsequently, descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, were calculated for all pre-test and post-test scores for both groups. Next, the assumptions for parametric tests were rigorously checked. The Shapiro–Wilk test indicated that the data did not significantly deviate from normality (all p > 0.05), a finding supported by visual inspection of Q-Q plots and acceptable values for skewness (all < |2.0|) and kurtosis (all < |7.0|) (Byrne, 2016). Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances was non-significant (p > 0.05) for all between-group comparisons, confirming the assumption of homogeneity of variance. Finally, after confirming these assumptions, inferential analyses were conducted: independent-samples t-tests to compare post-test scores between groups (H1) and paired-samples t-tests to compare pre-post scores within the experimental group (H2), with effect sizes calculated using Cohen’s d.

4 Data analysis and results

This section presents the findings of the statistical analyses, which were designed to test the study’s hypotheses regarding the effect of a chatbot intervention on student resistance.

4.1 Homogeneity of the experimental and control groups

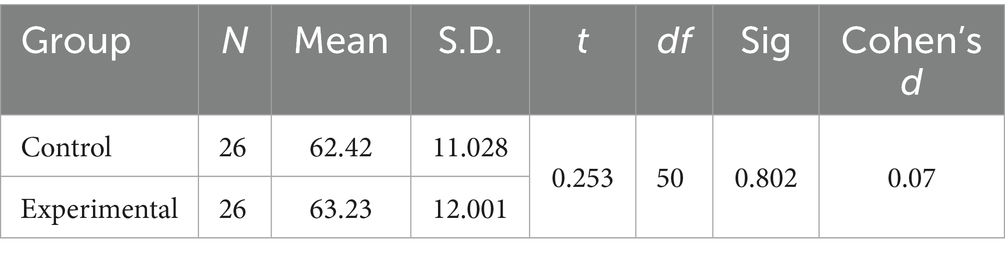

To assess the initial equivalence of the two groups, an independent samples t-test was conducted on the pre-test scores of the Technology Change Resistance Scale for both the control and experimental groups (Table 1).

The results revealed a t-value of 0.253, which was not statistically significant (p = 0.801). Cohen’s d was calculated to quantify the magnitude of pre-test differences (d = 0.07), confirming a negligible effect size and reinforcing group equivalence (Cohen, 1988). The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference was [−2.92, 3.76], containing zero, which further supports the lack of a significant difference. This indicates no meaningful difference between the control and experimental groups in their pre-test resistance to technological change. Consequently, the two groups can be considered equivalent in their baseline levels of technology change resistance prior to the experiment.

4.2 Hypothesis one testing

To examine the validity of the first hypothesis, an independent samples t-test was employed to compare the mean scores between the control group (taught via traditional methods) and the experimental group (using chatbots) in the post-test administration of the Technology Change Resistance Scale (Table 2).

As demonstrated in Table 2, the analysis yielded a statistically significant t-value of 11.211 (p < 0.001), indicating a meaningful difference between the experimental and control groups. The experimental group, which received chatbot-assisted instruction, achieved a lower mean resistance score (M = 34.46; SD = 6.048) compared to the control group (M = 61.15; SD = 7.692), supporting the effectiveness of the intervention. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference [22.07, 31.31] does not include zero, confirming the significance of the finding. Furthermore, the very large effect size (d = 2.87) underscores the high degree of practical significance of the findings, suggesting that chatbots may serve as a powerful tool for mitigating student resistance in educational settings.

A post-hoc power analysis was conducted using G*Power 3.1 with the observed effect size (d = 2.87) and α = 0.05. The analysis revealed a statistical power (1 − β) of >0.99, far exceeding the conventional 0.80 threshold. This confirms that despite the focused sample size (N = 52), the study was more than adequately powered to detect the large effect of the intervention.

Dimensional analysis (Table 3) revealed significant reductions across all resistance facets (all p < 0.001), with the largest effects for emotional reactions (d = 1.45) and adherence to routine (d = 1.12). Cognitive rigidity and short-term thinking showed moderate but meaningful improvements (d = 0.62, 0.54), suggesting chatbots address both affective and cognitive barriers. Consequently, the first alternative hypothesis (H1) was accepted.

4.3 Hypothesis two testing

The second hypothesis was tested using a paired-samples t-test to compare the experimental group’s pre-test and post-test mean scores following the chatbot intervention. Table 4 presents these findings.

Table 4. Paired samples t-test for pre-treatment and post-treatment technology change resistance of the experimental group.

The results revealed a statistically significant t-value of 11.497 (p < 0.001), indicating a meaningful difference between the experimental group’s pre-test and post-test scores on the Technology Change Resistance Scale. The post-test mean score (M = 34.46; SD = 6.048) was significantly lower than the pre-test score (M = 61.15; SD = 7.692), reflecting a reduction in resistance following the chatbot intervention. The 95% confidence interval for the mean reduction [22.29, 30.99] confirms the significance of the change. The paired-samples analysis yielded a large effect size (d = 2.91), reinforcing the substantial practical significance of the intervention.

Paired t-tests for each resistance dimension (Table 5) revealed significant pre-post reductions (all p < 0.001). The largest effects were observed for emotional reactions (d = 1.82) and adherence to routine (d = 1.32), while cognitive rigidity and short-term thinking showed strong but slightly smaller improvements (d = 0.98, 0.87). Accordingly, the second alternative hypothesis (H2) was accepted.

5 Discussion

This study provides robust experimental evidence that a chatbot-based intervention can serve as a powerful tool to mitigate student resistance to technological change. The findings illuminate the specific psychological mechanisms through which chatbots operate and hold significant implications for the sustainable integration of educational technology, particularly within the context of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

5.1 Interpretation of key findings and theoretical implications

The conversational nature of chatbots appears to be uniquely effective in disarming the affective barriers that underpin technological resistance. The largest effect sizes were observed in reducing emotional reactions and routine adherence, suggesting that chatbots primarily function as affective and behavioral regulators. This can be interpreted through the lens of Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). The chatbot provided a scaffolded, low-stakes environment where students could engage with new technology without the fear of public failure. This “scaffolding for affect” likely reduced anxiety and built the confidence necessary to step outside familiar routines, a challenge noted in prior resistance literature (Stewart et al., 2009). Our findings thus extend social constructivist theory by demonstrating its application not just to cognitive development, but to the crucial domain of emotional readiness for learning.

Beyond affective support, the chatbot served as a cognitive partner that systematically dismantled rigid thinking patterns. The significant, though slightly smaller, reductions in cognitive rigidity and short-term thinking indicate that the intervention also engaged students on a conceptual level. The chatbot’s structured guidance and immediate feedback provided a form of cognitive scaffolding, breaking down the complex process of learning a new technology (HTML) into manageable, conversational steps. This mitigated the overwhelm that often leads to cognitive shutdown and short-term focus on effort. This aligns with findings from Kuhail et al. (2023), who noted that chatbots can make complex subjects more approachable, and suggests that with longer exposure, these cognitive shifts could deepen further.

5.2 Contribution to the literature and sustainable educational change

Our findings position chatbots as a viable intervention in a landscape with few direct analogues for reducing student resistance. While studies have extensively documented chatbots’ benefits for learning outcomes (Deng and Yu, 2023) and teacher adoption (Ogunleye et al., 2024), this study directly addresses the initial barrier of student resistance. The observed effects are notably larger than those typically seen in general technology acceptance studies, underscoring the targeted efficacy of a conversational AI interface. This contribution is critical because mitigating resistance is the first and most crucial step toward sustainable educational change. By lowering the initial barrier to adoption, chatbots can help ensure that technology integration leads to sustained use, reduced student dropout from digital courses, and more equitable access to quality educational tools—core tenets of SDG 4.

5.3 Practical implications for the Saudi Arabian educational context

The results offer a concrete strategy for advancing the digital transformation goals of Saudi Vision 2030. For Saudi educators and policymakers, this study demonstrates that chatbots are not merely content-delivery tools but are powerful instruments for shaping student attitudes and fostering a culture of innovation. The specific reduction in emotional resistance is particularly relevant, as it addresses a key hurdle in a rapidly modernizing educational landscape.

To leverage these findings, we propose several evidence-based strategies. To capitalize on the reduced emotional reactions, chatbots can be implemented as “onboarding buddies” for new software or digital platforms, providing a safe space for initial exploration. To address routine adherence, chatbots can be used to introduce and guide students through new, technology-enhanced pedagogical models, such as flipped classrooms or project-based learning, making the transition away from lecture-based routines less abrupt. Furthermore, to foster system-wide change, chatbot-based modules should be integrated into national professional development programs for teachers, showcasing them as a proven method to reduce student resistance and smooth the path for other digital initiatives.

In conclusion, this study moves beyond establishing that chatbots reduce resistance to beginning to explain how and why. By acting as both an affective scaffold and a cognitive guide, chatbots address the root causes of resistance. This positions them as a key enabler for building resilient, adaptable, and sustainable educational ecosystems in Saudi Arabia and beyond.

6 Limitations

While this study offers compelling evidence that a chatbot-assisted learning environment can reduce student resistance to technological change, its findings must be interpreted within the context of several methodological limitations.

First, the generalizability of the findings is constrained by the study’s scope. The sample was drawn from a single school in Al-Ahsa, was relatively small (N = 52), and the intervention was brief (2 weeks). Furthermore, the sample was selected based on high pre-existing resistance, which, while strengthening internal validity, limits the applicability of the results to the general student population. The specialized nature of the chatbot, focused on teaching HTML via Telegram, also raises questions about whether similar effects would be observed with other subjects, age groups, or more advanced chatbot platforms like generative AI.

Second, the potential for bias exists despite the experimental design. Students in the experimental group were aware of their participation in a novel technology intervention, which may have introduced expectancy effects (Hawthorne Effect) that positively influenced their responses, independent of the chatbot’s specific qualities.

Third, the strictly quantitative design and data limitations prevent a deeper understanding of the “why” behind the results. The absence of qualitative data, such as student interviews or focus groups, means we lack rich insights into the cognitive and emotional processes students experienced. This makes it difficult to fully corroborate the theoretical links to Social Constructivism or to understand precisely which chatbot features students found most supportive.

Finally, the study lacks long-term data. Without follow-up measures, it is impossible to determine whether the observed reductions in resistance were sustained over time or if they led to lasting changes in technology adoption behavior.

To address these limitations, future research should pursue several directions. Future studies should employ mixed-methods designs, integrating qualitative approaches such as focus groups and in-depth interviews to explore the student experience in rich detail and validate quantitative findings. Longitudinal studies tracking student resistance and technology use over extended periods (e.g., a full academic year) are needed to assess the long-term retention of intervention effects. Furthermore, enhancing generalizability through scaling—by replicating this study across multiple schools in different regions of Saudi Arabia and including teacher-student comparisons—would provide valuable insights into resistance dynamics across different stakeholders. Finally, there is a need to refine the measurement tool by developing and validating a resistance scale specifically designed for the age of AI, incorporating modern constructs like trust in AI, perception of social presence, and data privacy concerns.

By addressing these avenues, future research can build upon the present findings to develop more nuanced, effective, and scalable strategies for fostering sustainable educational technology integration.

7 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that chatbots are not merely pedagogical tools for delivering content but are powerful interventions for fostering positive student attitudes toward technological change. By providing empirical evidence that chatbots significantly reduce key dimensions of resistance—especially emotional reactions and routine adherence—this research moves the conversation beyond technical implementation to address the critical human factors that determine the success or failure of educational technology initiatives.

7.1 Implications for educational practice

For educators and school administrators, these findings offer a clear strategy for smoothing digital transitions. We recommend implementing chatbots as “onboarding guides” to introduce new software or digital platforms, providing students with a safe, private environment to overcome initial anxiety and build confidence before full-scale implementation. Furthermore, educators should adopt chatbots for differentiated support, leveraging their 24/7, self-paced nature to provide targeted scaffolding for students who struggle with cognitive rigidity, allowing them to master new technological processes at their own speed. Finally, chatbot integration should be positioned as a low-risk method for encouraging flexibility and breaking habitual resistance, thereby fostering a culture of innovation around new teaching and learning methods.

7.2 Policy-level consequences and recommendations

The results necessitate a strategic shift in educational policy, particularly in contexts like Saudi Arabia pursuing ambitious digital transformation under Vision 2030. First, in the domain of Teacher Education and Professional Development, policy should integrate AI literacy and chatbot facilitation skills into national training programs. This is crucial to equip teachers not only to use technology but to manage student resistance and effectively integrate chatbot-based scaffolding into their pedagogy. Second, regarding Information Technology Pedagogies, policy must move beyond traditional IT curricula to develop frameworks that incorporate AI tools like chatbots to teach digital literacy, problem-solving, and adaptive learning skills. The rationale is to evolve technology education from simple tool mastery toward developing the cognitive flexibility and emotional resilience needed for a changing digital landscape. Third, for AI Ethics and Governance, clear ethical guidelines must be established to address data privacy, algorithmic bias, and the balance between AI-driven and human-led instruction. This proactive policy is required to ensure equitable, transparent use that protects student well-being, builds trust, and sustains long-term adoption.

In conclusion, this study provides a compelling evidence base for policymakers and practitioners to leverage chatbots as strategic assets. By doing so, they can directly address the human element of technological change, thereby accelerating progress toward sustainable, inclusive, and resilient educational systems as envisioned by SDG 4.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Research Ethics Committee at King Faisal University (KFU-REC-2023-AUG-ETHICS1074). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

EA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia (project no. KFU253970).

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author declares that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdel-Moula, W., and Al-Ayyeb, S. (2021). Technological change in the institution and the problem of workers’ cultural identity: A socio-cultural reading. Algerian Journal of Human Security, 6, 1–23. Available at: https://www.asjp.cerist.dz/en/article/157880

Abdulghani, S. A. F. (2023). Chatbots and their use in information institutions: an analytical exploratory study. Sci. J Lib Doc Inf 5, 269–310. doi: 10.21608/jslmf.2022.172768.1147

Adamopoulou, E., and Moussiades, L. (2020). Chatbots: history, technology, and applications. Mach. Learn. Appl. 2:100006. doi: 10.1016/j.mlwa.2020.100006

Al-Najjar, M., and Habib, A. (2021). An artificial intelligence program based on chat robots and training environment learning style and its impact on developing skills in using e-learning management systems for preparatory stage teachers. Educ Technol Stud Res 31, 91–201. doi: 10.21608/tesr.2021.149030

Al-Salk, D. A. I. (2016). Two patterns of electronic performance support systems in educational computer games (verbal and proxy) and their impact on developing wayfinding skills for preschool children. Educational Technology: Studies and Research, 26, 241–293. doi: 10.21608/tesr.2016.306959

Al-Shenqiti, O. M. (2022). Teachers’ attitudes towards using interactive chat robots (Chatbots) in teaching students with disabilities in Medina. Arab Journal of Disability and Gifted Sciences, 6, 51–80. doi: 10.21608/jasht.2022.248044

Armstrong, N. (2022). Investigating digital agility: using a chatbot to scaffold learning opportunities for students [doctoral dissertation, Lancaster University]. Lancaster: Lancaster University.

Barak, M. (2018). Are digital natives open to change? Examining flexible thinking and resistance to change. Comput. Educ. 121, 115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2018.01.016

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. 3rd Edn. New York: Routledge.

Celik, I., Dindar, M., Muukkonen, H., and Järvelä, S. (2022). The promises and challenges of artificial intelligence for teachers: a systematic review of research. TechTrends 66, 616–630. doi: 10.1007/s11528-022-00715-y

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd Edn. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Crompton, H., Burke, D., and Lin, Y. (2022). The disruptive power of artificial intelligence: a review of the literature. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 70, 1801–1825. doi: 10.1007/s11423-022-10132-w

Cukurova, M., Miao, X., and Brooker, R. (2023). “Adoption of artificial intelligence in schools: unveiling factors influencing teachers' engagement” in Artificial intelligence in education, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 13916. eds. N. Wang, G. Rebolledo-Mendez, N. Matsuda, O. C. Santos, and V. Dimitrova (Cham: Springer), 151–163.

Cunningham-Nelson, S., Boles, W., Trouton, L., and Margerison, E.. (2019). A review of chatbots in education: practical steps forward. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference for the Australasian Association for Engineering Education. AAEE; Available online at: https://aaee.net.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/AAEE2019_Annual_Conference_paper_184.pdf (Accessed June 26, 2025).

Deng, X., and Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis and systematic review of the effect of chatbot technology use in sustainable education. Sustainability 15:2940. doi: 10.3390/su15042940

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., et al. (2023). Opinion paper: “so what if ChatGPT wrote it?” multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 71:102642. doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102642

Hobert, S.. (2019). How are you, chatbot? Evaluating chatbots in educational settings - results of a literature review. In Proceedings of DeLFI - e-Learning Fachtagung Informatik. Gesellschaft für Informatik. Available online at: https://dl.gi.de/bitstreams/63fce548-ec83-4e82-848d-41393ac1bbc5/download (Accessed April 26, 2025).

Kuhail, M. A., Alturki, N., Alramlawi, S., and Alhejori, K. (2023). Interacting with educational chatbots: a systematic review. Educ. Inf. Technol. 28, 973–1018. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-11177-3

Ministry of Education and Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority. (2025). Saudi Arabia announces national AI curriculum for schools as part of vision 2030 reforms. Saudi Press Agency. Available online at: https://www.spa.gov.sa/en/w2355495 (Accessed 31 July, 2025).

National Transformation Program. (2020). Vision 2030 programs. Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Available online at: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/ (Accessed May 30, 2025).

Ogunleye, B., Zakariyyah, K. I., Ajao, O., Olayinka, O., and Sharma, H. (2024). A systematic review of generative AI for teaching and learning practice. Educ. Sci. 14:636. doi: 10.3390/educsci14060636

Pérez, J. Q., Daradoumis, T., and Puig, J. M. M. (2020). Rediscovering the use of chatbots in education: a systematic literature review. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 28, 1549–1565. doi: 10.1002/cae.22326

Pfaltzgraf, D., and Insch, G. S. (2021). Technological illiteracy in an increasingly technological world: methods to help employees create with rather than simply consume technology. Dev. Learn. Organ. 35, 4–6. doi: 10.1108/DLO-12-2020-0235

Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority (SDAIA). (2025). Saudi academic framework for AI qualifications (education intelligence) 2023–2024. Available online at: https://sdaia.gov.sa/en/Research/Documents/SaudiAcademicFramework.pdf (Accessed 7 August, 2025).

Selwyn, N. (2019). Should robots replace teachers? AI and the future of education. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Șerban, A., Aviana, A. E., and Popescu, D. M. (2020). Resistance to change and ways of reducing resistance in educational organizations. Ovidius Univ. Ann., Ser. Econ. Sci. 20, 785–788. Available at: https://stec.univ-ovidius.ro/html/anale/RO/2020/Section%204/34.pdf (Accessed February, 2025).

Smutny, P., and Schreiberova, P. (2020). Chatbots for learning: a review of educational chatbots for the Facebook messenger. Comput. Educ. 151:103862. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103862

Stevenson, N. A., VanLone, J., and Barber, B. R. (2020). A commentary on the misalignment of teacher education and the need for classroom behavior management skills. Educ. Treat. Child. 43, 393–404. doi: 10.1007/s43494-020-00031-1

Stewart, W. H. Jr., May, R. C., McCarthy, D. J., and Puffer, S. M. (2009). A test of the measurement validity of the resistance to change scale in Russia and Ukraine. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 45, 468–489. doi: 10.1177/0021886309338813

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics. 7th Edn. New York: Pearson.

Tadese, M., and Mihretie, A. (2021). Attitude, preparedness, and perceived self-efficacy in controlling COVID-19 pandemics and associated factors among university students during school reopening. PLoS One 16:e0255121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255121

Thomas, L. (2024). Quasi-experimental design | definition, types and examples. Scribbr. Available online at: https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quasi-experimental-design/ (Accessed 16 April, 2025).

UNESCO (2022). Technology in education: a tool on whose terms? Global education monitoring report. Available online at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381566 (Accessed March 2, 2025).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Winkler, R., and Söllner, M. (2018). Unleashing the potential of chatbots in education: a state-of-the-art analysis. Acad. Manage. Proc. 2018:15903. doi: 10.5465/AMBPP.2018.15903abstract

Wollny, S., Schneider, J., Di Mitri, D., Weidlich, J., Rittberger, M., and Drachsler, H. (2021). Are we there yet? – a systematic literature review on chatbots in education. Front Art Intell 4:654924. doi: 10.3389/frai.2021.654924

Yılmaz, D., and Kılıçoğlu, G. (2013). Resistance to change and ways of reducing resistance in educational organizations. Eur J Res Educ 1, 14–21. Available at: https://studylib.net/doc/8664662/resistance-to-change-and-ways-of-reducing-resistance-in (Accessed January 23, 2025).

Zaky, Y. A. M. (2023). Chatbot positive design to facilitate referencing skills and improve digital well-being. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 17, 106–126. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v17i09.38395

Keywords: chatbots, resistance to technology, sustainable education, sustainable development goal, student behavior

Citation: Al Mulhim EN (2025) Mitigating student resistance: the role of chatbots in sustainable educational technology integration. Front. Educ. 10:1711832. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1711832

Edited by:

Sami Heikkinen, LAB University of Applied Sciences, FinlandReviewed by:

Tapas Sudan, Shri Mata Vaishno Devi University, IndiaTommy Tanu Wijaya, Beijing Normal University, China

Copyright © 2025 Al Mulhim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ensaf Nasser Al Mulhim, ZWFsbXVsaGltQGtmdS5lZHUuc2E=

Ensaf Nasser Al Mulhim

Ensaf Nasser Al Mulhim