- Department of Business Management, Faculty of Business and Law, The British University in Dubai, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Introduction: Crises in higher education institutions (HEIs) often demand authentic care, responsibility, and ethical leadership. However, leaders with psychopathic traits–such as superficial charm, manipulativeness, and a lack of empathy–may strategically deploy ethical rhetoric to protect their self-interest. In the context of Emirati HEIs, where hierarchical norms and institutional prestige shape leader-follower dynamics, this “calculated compassion” can mask harmful decision-making and undermine organizational well-being.

Methods: This qualitative study drew on semi-structured interviews with 18 employees working across public and private HEIs in the United Arab Emirates. Interviews explored participants’ experiences with leadership behavior during institutional crises, such as layoffs, program closures, and organizational restructuring. Data were analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis to identify recurring patterns of crisis-time manipulation embedded within ethical discourse.

Results: Three major themes emerged. (1) Moral Theatre: Staged Compassion During Layoffs and Closures—leaders publicly enacted empathy and ethical concern while privately endorsing decisions that intensified employee vulnerability. (2) Strategic Sympathy: Selective Use of Ethics to Shield Reputations—ethical language was mobilized defensively to maintain institutional legitimacy and leader image, particularly during contentious decisions. (3) Aftershocks of Betrayal: Trust Erosion and Long-Term Disengagement–employees described profound disillusionment, leading to reduced morale, diminished organizational commitment, and persistent relational distrust.

Discussion: Findings demonstrate that psychopathic traits enable leaders to transform ethical rhetoric into a tool of manipulation during crises. This “calculated compassion” produces a deceptive moral façade that obscures self-serving decision-making and harms employee trust. By highlighting how crisis-time ethics can be strategically weaponized, the study extends leadership ethics and crisis management scholarship and contributes a regional perspective on the hidden costs of destructive leadership in HEIs operating under global and national policy pressures.

1 Introduction

This paper examines crisis leadership in higher education institutions (HEIs) in the United Arab Emirates, with a particular focus on how leaders with psychopathic traits manipulate ethical rhetoric during times of organizational stress. While crises in HEIs often provide opportunities for leaders to demonstrate responsibility and care, psychopathic leaders instead exploit these situations, borrowing the vocabulary of morality and compassion while making decisions that primarily serve their own interests. This paper is prepared to extend the argument of Alowais and Suliman (2025a), which showed that Dark Triad traits are not only imposed by leaders but also mirrored by employees, creating cycles of ethical erosion. Building on that insight, this study shifts the focus to crisis contexts, examining how psychopathic leaders weaponize ethics as a façade of compassion while pursuing self-serving agendas.

Ethical leadership is a crucial need in modern organizations, and this determines how employees, stakeholders and people in general follow leaders in terms of credibility and their accountability to them. Research shows that ethical conduct leads to the increase of trust, engagement and organizational resiliency in the long-term. In recent times, when stakeholders have become more conscious and demanding of corporate conduct than ever, responsible actions by leaders are not just a matter of moral discretion but a necessity of legitimacy and success. Ethics is, therefore, the fulcrum of organizational leadership, especially during times of crisis, when the consequences and scrutiny of such decisions are higher. Crises are turning points in organizations; they present both dangers and opportunities (Gkeredakis et al., 2021). It reveals vulnerabilities and questions accountability. Furthermore, they allow leaders to show their integrity, empathy, and decision-making ability. Literature on crisis management indicates that open communication, ethical integrity and participatory decision-making promote trust and increased recovery. Ethical leadership during crises is thus not simply about avoiding reputational damage but about affirming an organization’s values when they matter most (Ng and vanDuinkerken, 2021). In the same breath, crises exacerbate the leadership paradox: some leaders will demonstrate responsibility and compassion, and some will take advantage of such situations to benefit themselves or their organizations.

This contradiction is more evident when there are psychopathic leaders within corporate settings. Although psychopathy is more often associated with criminal acts, it can still be found in the organizational environment and is frequently manifested in non-obvious and destructive ways. The characteristics of manipulativeness, shallow charm, and lack of empathy can make psychopathic leaders’ candidates to move through hierarchies since they can manage their impressions and bend systems to their own benefit (Babiak and Hare, 2006). However, in times of crisis, their indifference to the well-being of others can be the most dangerous since their actions can significantly impact the safety of employees and the organization’s stability. Such leaders tend to use the rhetoric of ethics and compassion, positioning themselves as sober stewards masking self-seeking decisions. This leads to a paradox where compassion is not real but artificial, which makes ethics a performance instead of a practice. Thus, Alowais and Suliman (2025a) portrayed higher education institutions (HEIs) as vulnerable ecosystems where Dark Triad traits are not only projected by leaders but also mirrored by employees, creating cycles of ethical erosion. They argued that HEIs risk institutional integrity when toxic leadership and dark followership reinforce one another, normalizing unethical conduct across organizational levels. To address this, the authors called for leadership profiling, cultural audits, and systemic reform to safeguard psychological safety and accountability.

1.1 Statement of the problem

This problem is escalated by the increasing use of ethical narratives in corporate communication. Corporations have become more value-oriented in the last 20 years, especially during crises (Dzoba, 2024). Ethical narratives have become a key part of crisis messages in that organizations have sought to assure stakeholders and safeguard reputations. However, these accounts are susceptible to manipulation. Authorities without true ethical integrity can use ethical rhetoric as a protection against reality, hiding choices in favor of cost-reduction, brand survival, or personal gain when those choices endanger the welfare of many. Employees, in their turn, will directly feel the effects of these decisions and will often be aware of the disjunction between the statements and the reality. The outcome is an increasing distance between business communication and staff confidence. This disconnect weakens organizational culture, leaving a sense of suspicion and disengagement that makes recovery much more difficult well beyond the first days of the crisis. The issue, however, is not solely in the unethical decisions or acts but instead in the deception behind the use of the language of compassion that masks evil actions as a duty. This study confronts the neglected paradox of crisis leadership in how psychopathic leaders manipulate the language of ethics to mask self-serving agendas, projecting compassion while deepening harm. The risks of such behavior are acute in higher education, where credibility, trust, and integrity are central to institutional legitimacy. Alowais and Suliman (2025a) demonstrated that HEIs are not immune to these dynamics; on the contrary, they are especially vulnerable to ethical contagion, as Dark Triad traits in leaders are mirrored and reinforced by employees, creating cycles of misconduct. Their call for systemic reform highlights an urgent need: to move beyond assuming ethics is inherently genuine, and instead to interrogate how it can be weaponized as a tool of control.

1.2 Research objectives and questions

This study is inspired by the necessity to comprehend how psychopathic leaders use ethical stories in times of crisis and how this behavior leads to the risks of organizational cultures. It answers three primary objectives. Research Objective (1) To investigate how psychopathic leaders present harmful choices as ethical descriptions. Followed by Research Objective (2) To investigate how employees interpret the gap between corporate “compassion” and personal or collective loss. Finally, Research Objective (3) To assess the long-term impact of such moral trickery on trust and organizational healing. These objectives are framed to answer the following questions: Research Question (1) What are the methods used by psychopathic leaders to justify evil choices in moral terms? Research Question (2) How do employees make sense of corporate “compassion” that results in personal loss? Research Question (3) Does this paradox exacerbate post-crisis cultural recovery?.

1.3 Importance of the study

The value of the study is both theoretical and practical. Theoretically, it can add to scholarship in leadership ethics and paradox theory, since it points to the moral rhetoric as a manipulative and strategic tool. Although many studies have focused on the advantage of ethical leadership (Brown et al., 2005), there has been little emphasis on how other leaders without moral conviction may appropriate the notion of ethical leadership. This paper thus brings complexity to the debate on ethical leadership because it demonstrates how ethics might serve as a sincere guide to action and a cynical performance. The study provides a clue to organizations that aim to safeguard their cultures against such manipulations. By recognizing patterns of “moral theater” and “strategic sympathy,” organizations can develop safeguards that ensure ethical claims are supported by authentic behavior. This affects governance, human resource policy, and crisis management procedures to help organizations better identify and address performative ethics. This study is important because it challenges the prevailing assumption that ethical discourse in leadership is always authentic and constructive. By exposing how psychopathic leaders weaponize ethics during crises, it equips organizations with a sharper lens to distinguish genuine care from calculated compassion. The findings not only advance theory on dark leadership and crisis management but also provide practical insights for safeguarding institutional integrity and protecting employees from ethical manipulation.

1.4 Outline of the paper

The paper systematically expounds on these themes. The literature review entails an analysis of the current literature on psychopathy in leadership, the use of ethical narratives in crises, and the implications of betrayal on organizational culture. The section “3. Methodology” describes the qualitative research used in this study, consisting of interviews to describe employees’ experiences with ethical paradoxes. The section “4. Results” outlines significant findings grouped under themes like moral theater, strategic sympathy, and aftershocks of betrayal. This discussion interprets these findings regarding the available literature on the theoretical implications of leadership studies and the practical implications of organizational management. Lastly, the conclusion addresses the overall contribution of the research, the importance of increased attention to ethical statements in crises, and how to protect organizational cultures from calculating leadership. In exploring the paradox of calculated compassion, the current paper will shed light on the fact that ethical discourse is a source of both resilience and deception. The lessons learnt here add to academic discussions and the practical concern of ensuring that business ethics are not just a pretense, especially during a crisis when they are needed the most.

2 Literature review

Research on leadership and ethics shows a troubling paradox: the very language of care can be weaponized by leaders with psychopathic traits. Studies on psychopathy, Corporate social responsibility (CSR), and crisis communication reveal how ethical narratives often mask self-interest, while employees experience these contradictions as moral theater and betrayal. This review traces how dark traits, ethical façades, and organizational sensemaking collide, setting the stage for a deeper investigation into ethics as both a shield and a tool of manipulation. Recent contributions by Alowais and Suliman (2025a,b,c) have expanded the understanding of Dark Triad dynamics in higher education, revealing how toxic leadership traits not only influence employee behavior but also manipulate ethical climates and sustainability initiatives. These works provide critical insights into the institutionalization of unethical conduct and inform the current study’s exploration of psychopathy’s role in crisis leadership.

2.1 Psychopathy in leadership: definitions, prevalence, and manifestations

Psychopathy in leadership reflects Jung’s Shadow Theory, where disowned destructive traits emerge in positions of power and influence. Within the Toxic Triangle framework, psychopathic leaders thrive in permissive contexts with susceptible followers and enabling environments. Psychopathy is usually defined as a set of interpersonal, affective, and behavioral characteristics, including superficial charm, manipulativeness, lack of affect, callousness, and the lack of remorse, assessed through clinical measures (such as PCL-R) and, in an organizational, through validated managerial ones (Joubert, 2022). Competitive, high-power occupations (including risks taking and impression managing) have disproportionate representation of subclinical psychopathic symptoms, misconstruing boldness and impression management as strategic acumen in the workplace (Brunell and Hermann, 2024). Quite the contrary, meta-analytic and field-based evidence associates these characteristics with abusive supervision, bullying, counterproductive work behavior, and non-functional unit climate despite gaining surface charisma (Bieńkowska and Tworek, 2023). This pattern lays the groundwork for a paradox in crises: the same leaders who project warmth and certainty can make cold, self-benefiting choices that offload harm onto employees and communities while preserving their own status.

2.1.1 Psychopathy’s communication profile and the rhetoric of care

Trait Activation Theory explains how psychopathic leaders adaptively deploy charm, empathy signals, and moral language when situational cues (like crises) demand it. Jung’s Shadow lens suggests this rhetoric masks deeper impulses of manipulation and control. According to impression-management research, psychopaths use superficial charm and rehearsed emotional mimicry to acquire resources and status (Blickle et al., 2018). Variously translated in the corporate environment, they include squarely rehearsed town halls, highly performed executive empathy, and timed philanthropy. The relevant experiments and SCCT explain the instruments at the disposal of leaders: controllable disclosures can be used to suppress a sense of culpability and perceived identity, and sympathy can be combined with biased factual presentations to dull indignation (Stephens et al., 2019). Related research on empathy in the crisis indicates that various kinds of empathy (cognitive and affective, claimed and demonstrated) may vary in their impact on perceived sincerity and reputation restoration- a finding also helps understand how empathy can be faked. In practice, strategic sympathy packages warm words with symbolic gestures such as small donations or temporary executive pay cuts while avoiding costly remedies, such as power-sharing with employees or independent monitoring (Stephens et al., 2019). The impact is best when accountability is unclearly defined and the outsiders are not openly investigated.

2.1.2 Leader traits in crisis: narcissism, psychopathy, and the appearance of care

Shadow projection seeps into organizational culture, where unethical conduct becomes normalized and replicated. The Toxic Triangle warns that once dark leadership is legitimized, its corrosive impact cascades into performance, trust, and long-term survival. The dark-trait leadership is heterogeneous. Most recent comparative studies indicate various patterns of moral signaling of different dark traits, with psychopathy characterized by affective dissonance preceding empathy language (Frankel, 2025). Psychopathy adds an element of coolness, the ability to play musician with perilous, dangerous verbal chatter, and broadening between the warm discourse and the harmful action (Spytska, 2025). Highly self-managed employees can perform at a higher rate of sustained performance, yet low empathy leads to doubtful authentic stakeholder interface (Mohd Fauzi, 2025). The consequence is an appearance but not commitment culture: Leadership communications with high communality but decisions in favor of personal status and short-term optics over long-term care. In the case of organizations, separating the two profiles is essential in screening, development, and crisis roles assignment.

2.1.3 Downstream effects on culture and performance

Shadow projection seeps into organizational culture, where unethical conduct becomes normalized and replicated. The Toxic Triangle warns that once dark leadership is legitimized, its corrosive impact cascades into performance, trust, and long-term survival. At the individual level, employees under dark-trait leaders report lower satisfaction and higher strain; at the team level, abusive supervision and perceived unfairness fuel conflict and withdrawal; organization-wide, trust and discretionary effort decline, and counterproductive behaviors rise (Blickle et al., 2018). Perceived integrity is particularly vulnerable to loss of confidence in leadership in cases where claims by the leaders are inconsistent with their actions; trust claims are more concentrated when they lose competence than when their integrity suffers (ISTSS, n.d.). Post-crisis cultural recovery depends on transparent admission of responsibility and the visible realignment of power and incentives; without these, moral language becomes noise, and employees anchor on peers—not leaders—for meaning, slowing learning and resilience (Williams et al., 2023).

2.2 Ethical narratives as instruments of manipulation

Ethical narratives function as strategic shadows — a projection of morality that conceals destructive intent (Jung). Trait Activation Theory shows how leaders exploit crises as cues to activate persuasive ethical rhetoric, protecting themselves while manipulating stakeholders. The expectations have a good deal to be exploited by psychopathic leaders. Research on moral disengagement shows how harm can be reframed as necessary or virtuous—via euphemistic labeling, advantageous comparison, diffusion of responsibility, and appeal to higher goals (Burhan and Malik, 2025). Ethical fading also clarifies how decision makers bracket moral issues in the short term to emphasize instead instrumental measures, and subsequently reframe moral language into external communication (Blickle et al., 2018). In this context, moral theater describes conspicuous displays of compassion—emotive speeches, symbolic donations, “family” metaphors—that mask simultaneous choices to externalize risk or cost. Studies in crisis communication demonstrate that, under ambiguity, sympathy can function almost like an apology in protecting one’s reputation, making it a tempting low-cost substitute for substantive repair (Stephens et al., 2019). Psychopathic traits—callousness, manipulativeness, shallow affect—amplify the effectiveness of such strategic sympathy, because the leader can simulate empathy without incurring the personal discomfort or resource sacrifice associated with genuine care (Frankel, 2025).

2.2.1 Ethics, CSR, crisis communication: shareholder expectations

Corporate social responsibility narratives often become stages for moral shadow projection, where leaders externalize care to hide internal exploitation (Jung). Trait Activation Theory highlights how external pressures, like shareholder scrutiny, activate leaders’ strategic use of ethics as performance. Research in crisis communication demonstrates that the public judges organizations on two dimensions, including liability for the harm and accountability in responding to it (Chunxia et al., 2022). Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) prescribes accommodative strategies—apology, compensation, and corrective action—when responsibility is high, and warns that denial or scapegoating backfires by intensifying anger and attribution of blame (Chunxia et al., 2022). Studies also show that expressions of sympathy and empathy improve post-crisis evaluations, particularly when responsibility is ambiguous or low (Stephens et al., 2018). Parallel streams in business ethics distinguish ethical leadership—leaders as moral persons and moral managers who model, communicate, and enforce norms—from rhetorical “ethics talk” that lacks behavioral backing (Zhou and Hamlet, 2025). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) scholarship suggests that disconnection between commitments and practices will attract the perception of hypocrisy and greenwashing, undermine credibility, and increase the skepticism of the stakeholder (Gatti et al., 2019). Collectively, these literatures provide a high standard: in crises, moral language can be normatively evidence but should be associated with visible, material acts to be credible.

2.2.2 CSR authenticity, greenwashing, and moral legitimacy

Greenwashing exemplifies the Shadow in corporate life, where organizations project virtue to hide exploitation. The Toxic Triangle adds that these narratives persist when followers and institutions collude in sustaining illusions of legitimacy. CSR communication and moral positioning are mainly carried out through CSR. Its identification and trust are developed when allied with operations, instigating skepticism and boycott desires when dissociated (Gatti et al., 2019). Such projects appear in greenwashing research that records cases of companies focusing on symbolic projects to overlook the actual harms. This strategy briefly appeases the stakeholders, but undermines them once discrepancies are unearthed (Feghali et al., 2025). These behaviors are more instrumental under psychopathic leadership: leaders will only make virtue claims when calculated based on reputational risk to make grace concessions, rather than on stakeholders’ needs. Repeated exposure to such tactic’s breeds learned skepticism inside organizations: employees begin to treat “we care” messages as signals of impending cuts or surveillance (Gatti et al., 2019). This destructive relationship damages the engagement, and further constructive care becomes difficult to express, despite the leadership change.

2.3 Moral disengagement, ethical fading, and “strategic sympathy”

Moral disengagement echoes Shadow Theory by rationalizing harm while preserving a moral self-image. Trait Activation Theory shows how crises trigger leaders’ selective sympathy to maintain appearances while advancing hidden self-interest. Three cognition processes maintain the sustained calculated compassion. Three cognition processes maintain the sustained calculated compassion. Moral disengagement re-socializes harm as an accomplishment of greater aims and scapegoats (Reamer, 2022). Second, ethical fading reduces the focus on the numbers, eliminating the evaluation of moral language in deliberation until it is searched again in the created stories. Third, later harm can be justified by moral licensing based on earlier ethical actions (Burhan and Malik, 2025). Psychopathic leaders take advantage of such processes effectively, as they do not have to pay much inner struggle to justify the harm and are capable of making such justifications look like care.

2.3.1 Aftershocks of betrayal: trust, culture, and recovery

The Shadow lingers after betrayal, embedding cynicism and mistrust into organizational memory. The Toxic Triangle illustrates how the destructive cycle persists as betrayed followers oscillate between silence, compliance, and disengagement. Trust repair theory establishes three elements of recovering following a wrongdoing: responsibility recognition and corrective response are investigable and satisfactory, and equitable procedures that provide a reflective voice to those harmed (ISTSS, n.d.). The stakeholders will assume an intention to deceive and be non-congruent in values, exhibiting a strong deterrent of forgiveness (Benedict et al., 2024). Studies of institutional betrayal indicate that failure of institutions that would take care of us to respond to damage adequately reinforces the adverse consequences: greater vigilance, enhanced whistleblowing, and weakening identification complicate recovery and make it even less amenable and more expensive. In organizations, lingering cynicism becomes cultural “scar tissue” that weakens resilience and slows post-crisis learning (ISTSS, n.d.). According to Blickle et al. (2018) Psychopathic leadership intensifies these aftershocks by delivering shallow apologies, shifting blame, and reverting to self-serving strategies once scrutiny eases, behaviors consistent with meta-analytic evidence that dark traits predict exploitation and unreliable prosocial conduct. The calculated compassion paradox, therefore, may lead firms down the rut of defensive practices and performative CSR that ensures reinforcement across an exterior label and empties interior trust.

2.4 Moral theater sensemaking by employees

Employees interpret leaders’ moral theater through Shadow dynamics, recognizing the gap between rhetoric and reality. Trait Activation Theory suggests situational cues like repeated hypocrisy activate skepticism and resistance in employee sensemaking. The disruption of routines and cues due to crises makes workplace employees even more dependent on the communication of their leader to make sense of what goes on Williams et al. (2023). Sensemaking research shows that people craft plausible narratives—rather than objective accounts—to preserve identity and restore order, especially under ambiguity and emotion (Williams et al., 2023). By placing framing of layoffs, safety shortcuts, or surveillance expansions as care, employees experience acute dissonance: the moral rhetoric asserts belonging and states personal loss. Such discrepancies are reserved for dialogue with time as hypocrisy, which foreshadows organizational groupthink, decreased commitment, and insubordination (Lapointe et al., 2022). Studies of psychological contract breach similarly show that perceived value violations—particularly when framed as benevolent—undermine trust in leadership, suppress citizenship behaviors, and increase turnover intentions. Internal crisis-communication studies add that employees rewards prompt disclosure, concrete support, and genuine accountability, but punish obfuscation and symbolic gestures detached from material relief (Li and Chen, 2018).

2.4.1 Boundary conditions, moderators, and mitigating practices

The Toxic Triangle framework highlights interventions (robust institutions, ethical cultures) as moderators that can disrupt dark leadership cycles. Shadow Theory suggests mitigation requires conscious recognition and integration of destructive tendencies rather than denial. Calculated compassion succeeds under ambiguity, leader-centric cultures, weak scrutiny, and pliable metrics; it fails where pluralistic oversight, employee voice, and verification are strong. The governance process in any institutions includes independent boards, a power audit committee, an ethics committee, robust whistle governance programs, and transparent actions, and it inflates the cost of being a hypocrite (Nguyen et al., 2023). Crisis-communication experiments have also proved that timing and message framing. Additionally, self-disclosure before external exposure can buffer reputational damage, and rational framing paired with crisis-type-matched strategies earns more credit from highly involved stakeholders than purely emotional appeals (ISTSS, n.d.). Trust-repair research recommends remedies beyond apology and compensation: shared governance in policy redesign, independent monitoring with public reporting, and acknowledgment of value-breach, not just rule-breach, to restore moral alignment.

2.5 Paradox theory and the ethics–performance tension

Paradox Theory aligns with Shadow Theory by showing how the coexistence of ethical language and unethical practice generates deep contradictions. The Toxic Triangle explains that these tensions are most dangerous when leaders, followers, and environments all normalize the paradox. The possibility of such a dynamic despite changes is explained through the theory of paradox. Organizations face enduring tensions between short-term performance and long-term stakeholder care, and between external legitimacy and internal integrity (Fayezi, 2022). Effective leaders surface and navigate these tensions—holding competing demands in view—rather than resolving them through one-sided gestures (Fayezi, 2022). In contrast, psychopathic leaders are able to defuse the manifestation of tension with rhetoric: they feign an appearance of caring so as to garner legitimacy at the cost of transferring pain to less powerful actors into a delicate state of what appears to be dynamic stability but is actually dependent on concealment and control. Over time, moral language functions less as a guide for action and more as a resource for impression management.

2.6 Theoretical framework

Carl Jung’s Shadow Concept Carl Jung’s analytical psychology posits that every individual harbors a “Shadow” the unconscious part of the psyche containing repressed weaknesses, desires, and instincts (Jung, 1959). In leadership contexts, particularly within hierarchical systems like higher education institutions (HEIs), this Shadow may manifest in unethical behaviors masked by socially desirable fronts. Jung argued that the repression of the Shadow leads to projection: individuals unconsciously assign their unacceptable traits to others. In toxic leadership, particularly in the Dark Triad constellation (narcissism, Machiavellianism, psychopathy), the Shadow is not merely suppressed but often harnessed for strategic manipulation. These leaders may present a facade of ethical leadership and compassion, especially during crises, yet their behaviors suggest underlying motives of power retention and self-interest. In the Emirati HEI context, where cultural decorum and public morality are emphasized, this duality can flourish unnoticed. Jung’s framework aids in explaining how calculated compassion emerges not from genuine care but from the leader’s shadow narrative that co-opts ethics as performance.

Trait Activation Theory (TAT) Trait Activation Theory (Tett and Burnett, 2003) posits that individual traits manifest behaviorally when relevant situational cues are present. TAT provides a lens to understand why psychopathic tendencies surface particularly during crises. While these traits may remain dormant in neutral environments, crises create high-stakes contexts that activate manipulative, emotionally detached, and dominance-seeking traits particularly beneficial for psychopathic leaders aiming to control narratives. The UAE HE sectors, marked by rapid reform, Emiratization policies, and global pressures, offers a fertile ground for trait activation. TAT helps explain the thematic findings such as moral theater and strategic sympathy where environmental stressors (e.g., layoffs, closures, institutional audits) activate dark leadership traits. Leaders then use ethical rhetoric selectively to appear empathetic while masking harmful decisions. TAT also explains variation in employee responses based on their own traits and situational interpretations, allowing for a contextualized understanding of organizational outcomes.

Ethical Climate Theory Victor and Cullen’s (1988) Ethical Climate Theory describes the shared perception among organization members of what ethically correct behavior is and how ethical issues should be handled. These climates influence employee decision-making and behavior by signaling organizational values. In toxic leadership environments, especially those with high-Dark Triad presence, ethical climates can become distorted. Leaders may construct what Alowais and Suliman (2025b,c) describe as an Ethics Mirage, a surface-level commitment to moral values that masks a culture of self-preservation and silence. In such climates, ethical cues become performative rather than guiding, reinforcing compliance over critical reflection. The theory is particularly relevant in the UAE context, where centralized authority structures and emphasis on social harmony may discourage whistleblowing or resistance. Ethical Climate Theory thus complements the Shadow and Trait Activation frameworks by focusing on the organizational level, mapping how climate cues mediate both leadership behavior and employee response.

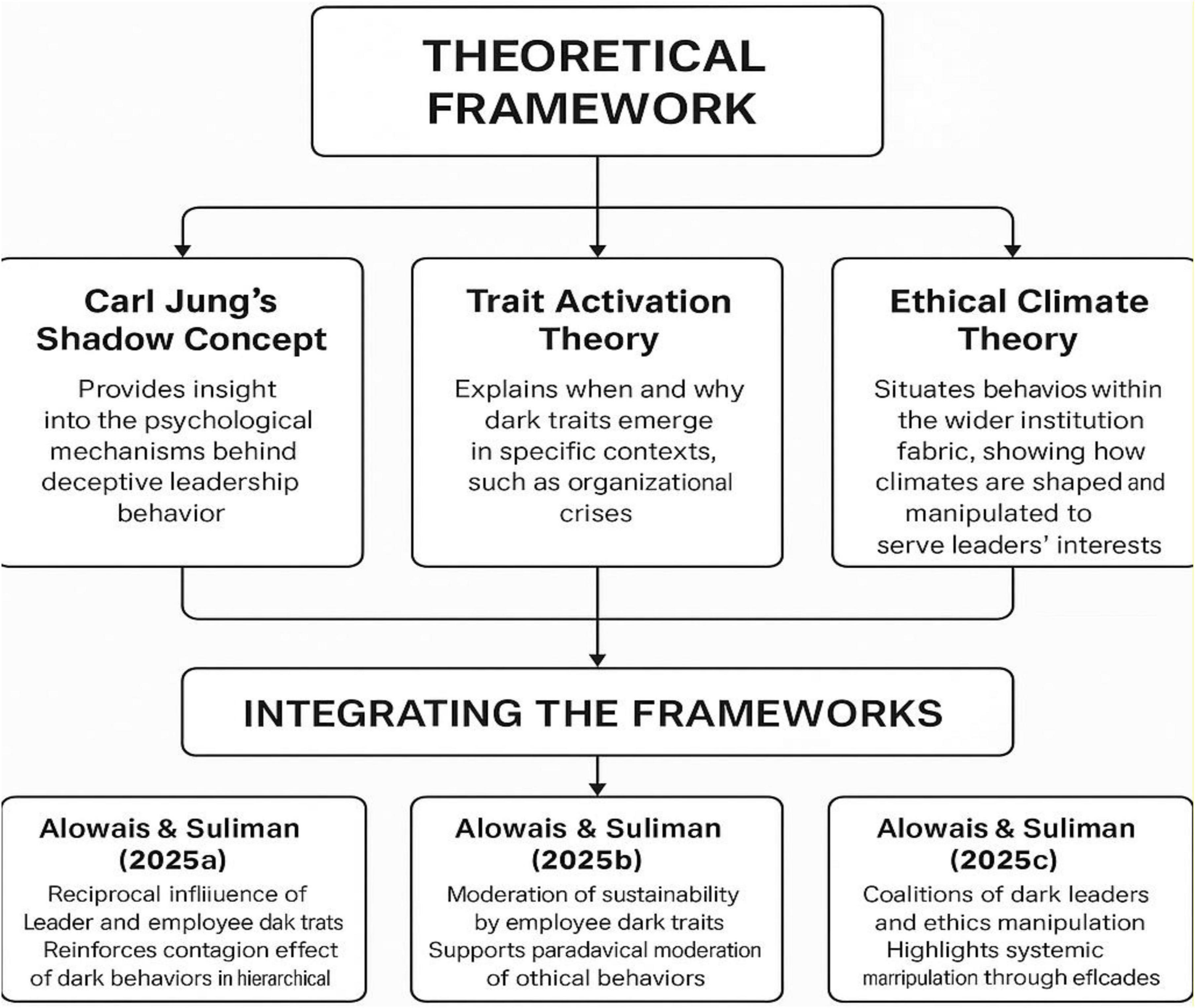

Integrating the Frameworks Combining these theories creates a multi-layered understanding of how psychopathic leadership operates during crises in HEIs. Jung’s Shadow concept provides insight into the psychological mechanisms behind deceptive leadership behavior. Trait Activation Theory explains when and why these dark traits emerge in specific contexts, such as organizational crises. Ethical Climate Theory situates these behaviors within the wider institutional fabric, showing how climates are shaped and manipulated to serve leaders’ interests. Together, these theories illustrate a dynamic model in which psychopathic leadership uses ethical rhetoric (the facade) to navigate crisis, exploiting institutional vulnerabilities and trait-sensitive environments. Alowais and Suliman’s (2025a,b,c) body of work reinforces this integrated approach, highlighting how leader-employee dynamics are not linear but recursive, shaped by culture, context, and character. This theoretical triangulation justifies the interpretivist stance of the study and supports the use of thematic analysis to capture lived experiences of betrayal, strategic ethics, and manipulated compassion. The brief explanation can be shown in Table 1 and followed by Figure 1 that shows maps the theoretical framework clearly.

This Table 1 maps foundational psychological and organizational theories alongside empirical insights from prior work by Alowais and Suliman. These theoretical anchors collectively form a scaffold to interpret the ethical paradoxes and dark leadership behaviors uncovered during crises in higher education.

Figure 1 visually integrates a framework combining Jung’s Shadow Concept, Trait Activation Theory (TAT), and Ethical Climate Theory to explain psychopathic leadership in higher education crises. Jung’s theory explores the psychological roots of manipulative behavior, TAT explains how dark traits are activated in high-stress contexts, and Ethical Climate Theory examines how organizational norms are shaped to mask unethical actions. The integration is supported by Alowais and Suliman (2025a,b,c), who show how dark traits spread through leader-employee dynamics, moderate ethical initiatives, and enable ethical manipulation through leadership coalitions. Together, the framework explains how toxic leaders exploit crises using ethical facades.

For full transparency and academic integrity, the literature reviewed in this study was sourced through Scispace.ai, a trusted research discovery platform that ensures access to peer-reviewed and current scholarly material. Additionally, the conceptual framework diagram was designed using Draw.io, a widely used visual diagramming tool. These tools were utilized to ensure that the theoretical foundations are ethically sourced, accurately represented, and visually mapped in alignment with accepted academic standards.

In examining how psychopathic or Machiavellian tendencies shape leadership behavior during crises, this study aligns with foundational scholarship on dark personality traits and unethical influence. Psychopathy and Machiavellianism share a core of manipulativeness, emotional detachment, and strategic impression management (Paulhus and Williams, 2002; Babiak and Hare, 2006), which enables leaders to present moral rhetoric while pursuing self-interest. Leadership communication research shows that persuasive ethical talk can function as a tool of control when used strategically (Clementson and Beatty, 2021; Fairhurst and Putnam, 2023). Crisis leadership theories further highlight that ethical narratives can be weaponized to maintain authority and deflect scrutiny during organizational turbulence (Coombs, 2007; Hannah et al., 2009). At the same time, ethical climate frameworks (Victor and Cullen, 1987, 1988; Brown and Treviño, 2006) emphasize that institutional norms can either constrain or enable manipulative leaders, especially when moral expectations are ambiguous. Social-cognitive theories of moral disengagement (Bandura, 1999) help explain how leaders justify harmful decisions while maintaining a façade of compassion. Methodologically, qualitative inquiry is particularly suited to uncover these hidden dynamics, as depth-oriented interviewing reveals implicit meanings and emotional contradictions that are often invisible in quantitative data (Hennink et al., 2017; Creswell and Poth, 2016). Collectively, this integrated theoretical lens explains how “calculated compassion” arises in HEIs: a convergence of dark traits, strategic moral communication, permissive ethical climates, and crisis pressures that create ideal conditions for morally deceptive leadership behavior (Padilla et al., 2007; Waldman and Bowen, 2016; Brown et al., 2005).

2.7 Methodological implications and research gap

Trait Activation Theory suggests studying crises as “natural laboratories” where dark traits surface under pressure. The identified gap lies in integrating Shadow dynamics, trait activation, and the Toxic Triangle to explain how ethics itself becomes a vehicle for manipulation. Despite converging evidence, only a few studies directly examine how psychopathic leaders instrumentalize ethical narratives in real-time crises. Corporate psychopathy research has primarily relied on cross-sectional surveys linking leader traits to climate and well-being (Gatti et al., 2019; Chunxia et al., 2022; Blickle et al., 2018). Crisis-communication scholarship has focused on message effects, seldom integrating leader personality (Coombs, 2007). A qualitative approach can bridge this gap by triangulating three levels: First leader traits (via multi-source assessments); secondly, message content (via systematic coding of empathy, identity frames, and responsibility management), and thirdly, employee sensemaking (via interviews that surface experiences of moral theater, strategic sympathy, and betrayal aftershocks). These designs can also define the impacts on the boundary conditions, including governance, media scrutiny, and voice climate, to identify whether ethical talk is translated into moral action.

Conclusively, in psychology, organizational behavior, ethics, and communication, the literature has focused on a sobering statement that crises provide psychopathic leaders with circumstances and resources to use the talk of care to make decisions that weaken the talk: classic theories, SCCT, and image repair. In every step of the mechanism, confusion and threat seek to elicit impression management; identification and sympathy frames afford moral cover; ritualistic actions replace structural solutions; the employees observe the disparities and conclude about hypocrisy and treachery; trust is undermined; the cultural amnesty stops. What the current study adds to the existing body of knowledge is the empirical mapping of this arc based on the inside, through the words of a sample of employees who experienced the paradox, and identifying organizational lever nodes, which translate professed compassion level of care into visible care when the pressure is on.

3 Methodology

This study adopts a qualitative design to explore how employees make sense of leaders who project compassion during crises while advancing self-serving agendas. Building on Alowais and Suliman (2025a), who demonstrated how Dark Triad traits spread reciprocally between leaders and employees, this paper extends the focus to crisis contexts where ethical narratives become tools of manipulation. Guided by Jung’s Shadow Theory (1959), the analysis emphasizes how hidden destructive motives are projected as moral façades, while thematic analysis provides a systematic approach to identify and interpret recurring patterns in participants’ accounts (Braun and Clarke, 2006).

3.1 Philosophical and methodological justification

This study adopts an interpretivist philosophical stance, which aligns with qualitative inquiry aiming to uncover the meanings and experiences of individuals within complex social settings. As per the qualitative layer of Saunders et al.’s (2019) research onion, the interpretivist paradigm is suitable when exploring subjective realities, particularly in sensitive topics like psychopathy in leadership, where participant narratives are nuanced and context bound. Accordingly, this research employed manual thematic analysis, following the protocol of Alowais and Suliman (2025a), who recommend this approach for Dark Triad research, due to its flexibility in capturing subtle psychological and behavioral cues that may be lost in formulaic coding.

While Participatory Action Research (PAR) is valuable in promoting organizational change and empowering participants, it is not the most appropriate design for this study. Firstly, PAR is rooted in a transformative or critical paradigm requiring participants’ active involvement in shaping the research agenda and implementing change (Reason and Bradbury, 2008). This is incompatible with the current study’s aim of understanding leadership behaviors retrospectively, rather than co-creating future interventions. Secondly, the ethical compliance requirements of the affiliated doctoral research program restrict iterative re-negotiation of roles and evolving methodologies inherent in PAR. Finally, introducing PAR would compromise methodological consistency, especially as this study forms one segment of a multi-paper thesis grounded in rigorously defined, interpretivist qualitative methods.

In sum, while PAR has merit in activism-oriented organizational studies, this research is intentionally designed to be non-interventionist, observational, and interpretive, thus making manual thematic analysis the more appropriate and epistemologically coherent method.

3.2 Research approach

This paper uses a qualitative, exploratory design to identify the mechanisms by which leaders use ethical narratives in crises and how employees respond to those narratives. Qualitative methods are appropriate when the goal is to capture lived experience, complex meaning-making, and context-specific dynamics rather than to estimate prevalence or causal effects (Creswell and Poth, 2016). The exploratory method is highly suitable for revealing hidden paradoxes and elegant rhetoric in attempts to study and uncover with the structuring instruments (Creswell and Poth, 2016). The study will prioritize depth, reflexivity, and contextual richness so that participants’ accounts drive theory refinement rather than test pre-specified hypotheses (Creswell and Poth, 2016).

3.3 Participants

The study sample consisted of 18 employees from higher education institutions (HEIs) in the UAE. This number was chosen to ensure sufficient depth and diversity of perspectives while remaining manageable for a qualitative, interview-based design. Following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) guidance on sample adequacy in thematic analysis, 18 participants allowed for the identification of recurring patterns without sacrificing the richness of individual narratives.

Participants represented a range of roles (faculty, administrative staff, and mid-level managers), genders (10 male, 8 female), and experience levels (ranging from 3 to over 15 years in academia). This variation provided insight into how employees at different organizational levels experience and interpret leaders’ use of ethical rhetoric during crises. Purposive sampling will identify information-rich cases that can speak to the research questions, and snowball referrals will extend reach to individuals who may be dispersed or reluctant to volunteer publicly (Palinkas et al., 2015).

3.4 Data collection

Data was collected through semi-structured, one-to-one interviews lasting approximately 20 min, conducted in person or via secure video conferencing according to participant preference (Kallio et al., 2016). Additionally, Kallio et al. (2016) states that semi-structured format balances consistency across respondents with flexibility to probe novel insights, emotional responses, and unanticipated themes. Interview topics will explore the content and timing of leader messages, observed managerial decisions, participants’ interpretations of “compassion” language, and the short- and longer-term effects on trust, morale, and behavior. Example prompts include: “Can you describe what senior leaders publicly said about responsibility during the crisis?”, “How did those statements match actions you observed?”, and “What impact did the messaging have on your trust and wellbeing?”

3.5 Data management and security

With participants’ consent, interviews will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a service bound to confidentiality. Transcripts will be de-identified by replacing organizational and personal with codes and stored on encrypted drives with access restricted to the core research team. All research procedures strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines of the British University in Dubai (BUiD). Prior to data collection, participants were informed of the study’s aims, their right to withdraw at any time, and the confidentiality of their responses. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and data were anonymized to protect identities. These measures ensured full compliance with BUiD’s ethics framework as well as broader international standards, including the Helsinki Declaration for research involving human participants.

3.6 Data analysis

Reflexive thematic analysis will uncover patterns associated with moral theater, strategic sympathy, paradoxical framing, and aftershocks of betrayal in transcripts (Braun and Clarke, 2021). According to Braun and Clarke (2021) analysis will proceed through iterative stages of familiarization, initial coding, theme generation, theme review, refinement, and write-up. Inductive coding will allow the participants’ language to give rise to the development of themes. At the same time, deductive attentiveness to the prevailing theory (e.g., moral disengagement, ethical fading) will specify interpretive overlay where warranted (Braun and Clarke, 2021).

3.7 Trustworthiness and reflexivity

To promote credibility and transparency, the study will note coding decisions in a living codebook and an audit trail of analytic memos and theme development (Guest et al., 2020). The triangulation will increase the resonance and reliance of the findings and participant-participant cross-industry and member checking with a subset of interviewees (Creswell and Poth, 2016). The research team will use reflexive journals to prevent the emergence of assumptions, positionality statements, and emotional reactions to sensitive disclosures (Braun and Clarke, 2021).

3.8 Ethical considerations

Recounting crisis experiences can be distressing, the research will follow trauma-informed recommendations that prioritize participant safety, community benefit, and researcher wellbeing (Jefferson et al., 2021). Consent documents will provide voluntary disclosure of the right to pause or withdraw, confidentiality protection, and concentration of confidentiality (where policies reveal harm or unlawful conduct at risk) limitations (Creswell and Poth, 2016). Interviewers will be trained in trauma-informed interviewing techniques to recognize and respond to distress and to provide signposting to support resources when needed (Jefferson et al., 2021).

3.9 Limitations

This study is limited by its relatively small sample of 18 HEI employees, which restricts generalizability. Findings are based on self-reported experiences, which may involve bias. In addition, the qualitative design provides depth but not causality, and the focus on selected theories may have overlooked other useful perspectives.

4 Results

The interviews were analyzed, dealing with three larger themes that also describe the perceptions and interpretation of the leadership behavior of employees who went through the organizational crisis. Such topics are the moral theater, strategic sympathy, and the Aftershocks of Betrayal. Both themes give insights regarding how those themes of compassion, ethics, and trust were negotiated in the workplace and what employees realized the irony of the leadership behavior in uncertain times.

4.1 Moral theater: staged compassion during layoffs and closures

The initial theme, moral theater, implies the idea that acts of goodwill by leaders were subjective to the attention of the employees, where they felt that the leaders tended to emulate or act in shows of compassion, particularly in times of organizational turmoil like layoffs or site closure. Respondents also explained how leaders were encouraging their expressions of care, whether through well-chosen words, the simple email that was sent to the whole company, or certain symbolic acts, which could not be connected to the experiences of victims and impacted people who were still alive. These acts created an illusion of kindness, but the reality was quite challenging since there were harsh consequences for employees.

As one respondent noted, the same participants were at the company town hall where the leadership was giving assurances of supporting the employees through the transition, but at the same time, reducing severance benefits. The dissociation between the professed abbreviation by the leader and the actual practices that had an adverse effect on employees made many doubt the truth of the statement. One respondent added that it would appear to us that we were watching a drama where the bosses were trying to appear like they had some compassion, but all the people in the room were aware that the result of the drama was written against us.

Employee 8 stated that “The announcement was filled with words like “family” and “care,” but within hours, half of my colleagues were gone. It felt like a performance, not compassion.” Which shows the care-washing relevance in the HEIs. Although this statement was not enough evidence as the employee could’ve been exaggerating. The next employee 9 “They spoke about protecting us and valuing our contributions, but the next slide showed which departments were closing. It was staged empathy.” In his defense, the whole university ended up closing down and relocating to another city with half the staff and with half of the current contracts already voided.

Few employees stated few quotes that were similar “It was as if the leaders were actors on a stage with their tone was soft, their words were gentle, but the decisions behind them were brutal.” The employees were usually kept in the dark and the fate of HEI employees were “dragged to the bottom of the ocean” as stated by the employees. The leaders used to deceive their employees as one employee stated, “We were told that “we are all in this together,” yet the layoffs only affected junior staff. The compassion felt scripted.” Moreover, the last employee nailed the coffin by stating “They held a town hall to explain the closures, and the whole thing felt rehearsed, the same phrases repeated over and over, like lines from a play.”

Moral theater is a concept that brings into involvement the incongruity presents about rhetoric and reality. In such cases, leaders aimed to uphold an ethical credit and reputation in the face of external parties like investors, the media, or the regulators, whilst internally the workers felt as though they were being left. Such symbolic compassion thyroid the sense of frustration and betrayal in employees and supports the view of ethics being a cover-up instead of sincere advice.

4.2 Strategic sympathy: selective use of ethics to shield reputations

The second theme, strategic sympathy, portrays the perception that employees had leaders ready to use compassion selectively and strategically to save their own image. Strategic sympathy, in contrast to moral theater, which focused on whether the act of compassion could be portrayed in a staged manner, meant applying ethical gestures in direction purpose either to go evasion in terms of escaping complaints, limit the extent of employee resistance, or retain control of an organization during a crisis. An employee stated that “They always stress “ethical responsibility” when speaking to the media, but internally they remind us that the priority is protecting the university’s image, not the people.” These are signs of care-washing when they are negatively impacting their own organizations. Moreover, “We only hear compassionate speeches when something risks going public. Otherwise, our concerns are ignored.” It is necessary to protect their own HEIs reputation, but it is necessary to question the harm the employees face in daily basis. Furthermore, employee 12 stated “It felt like sympathy was rationed; leaders expressed it only when cameras were around or stakeholders were watching.” It is believed that it is necessary to integrate ethical philosophies to please the stakeholders (Alowais, 2024) although HEIs leaders might enforce the performative acts (Alowais and Suliman, 2025a) which shows that caring is performative and not authentic. The first employee who interviewed stated that “The language of ethics was less about us and more about making sure their reputations stayed clean.” Now it sets the sarcastic attitude of the employees and psychopathic their leaders behavior. As an example, some participants explained how the leadership presented the layoffs as an act of Sympathy meant to safeguard the future wellbeing of the company, yet the impact of the crisis was not borne equally, as frontline workers were overwhelmed. The selective aspect of compassion manifested in the way the leaders stressed the adversity they had to endure in their lives, like the inability to make tough decisions, but condoned or claimed ignorance of the actuality of employees losing their lives. As Employee 3 stated, “They talked more about how hard it was for them to let people go than what it meant for us to be unemployed. Their sympathy seemed real, but only when it served their story.” They truly appeared to be sympathetic, except when it was convenient to their narrative. This point of view emphasizes the manner in which leaders position themselves as moral actors, at the same time determining the minimal number of material implications that the leaders impose on the employees. The results indicate that strategic sympathy acts as a defense mechanism of a leader. It helps leaders to maintain credibility in the media and, at the same time, shape the internal message. The employees realized this discriminative use of ethics and complained that morality was not applied as a rule to guide them, but instead as a rhetoric to control perceptions.

4.3 Aftershocks of betrayal: trust erosion and long-term disengagement

The last theme, Aftershocks of Betrayal, shows how betrayal by perceived insincerity and selective compassion is always experienced. Participants always cited trust in leadership and an organization as being deeply eroded after these experiences. The feeling of betrayal had very long-lasting impacts on many, even after the immediate crisis was already over, as they changed their way of dealing with the job and their perception of their employers.

The long-term disengagement starts with one employee stating that “After that so-called compassionate speech, I couldn’t believe anything they said again. The trust was gone, and it hasn’t come back.” Carrying more resentment for their leaders, few employees 7, 12 and 18 agree that “We kept working, but with half the energy. Once you see the gap between words and actions, your commitment just dies quietly.” Furthermore, two employees collectively stated that “Even now, months later, people don’t volunteer ideas anymore everyone feels it’s safer to stay silent than to risk another betrayal.”

Several participants narrated that being forced out of discretionary effort, withdrawal behavior, lack of involvement in organizational initiatives, and diminished loyalty occurred because of the staged selective application of ethics. One interviewee added that” “I stopped believing anything they said after that. I still did my job, but I stopped volunteering for extra projects or going the extra mile. Why should I, when they clearly didn’t care about us.” This is because too bad ethical response to a crisis can not only produce effects in the short term but also long-term effects like scars in employee morale and the toxic culture of an organization. The theme of Aftershocks of Betrayal highlights the irony of ethical leadership in times of crisis: whereas leaders might be willing to partake in the performance-based compassion in order to uphold reputation, the price in the long run would be a decline in trust, which reduces Organizational resilience. The lost trust was arduous to regain, and most of the participants stated a sense of distrust in future leadership activities. The net result was not just steps needed for bankruptcy but also augmented turnover intentions and cynicism, both of which diluted the strength of the organizational chord.

4.4 Interconnection of themes

Collectively, all three themes depict the trend of paradoxical leadership in a crisis. Moral theater emphasizes the symbolic quality of care employed in projecting an ethical image that does not have its workforce. Strategic sympathy shows that elements of compassion are selectively used to save the face of leadership, and they tend to undermine wellbeing among the employees. Lastly, the Aftershocks of Betrayal discloses the long-term results of such keenly felt patterns, since workers detract esteem and dedication in reaction to deceived sincerity.

The themes are not so individual; instead, they are connected. The corroding power of performative acts of compassion (moral theater) and compliance application (strategic sympathy) channels into the sustenance of shrinking trust and engagement (Aftershocks of Betrayal). The cycle illustrates the way in which the actions facing leadership decisions in crises have an effect that is more far-reaching than organizational survival in the short run and the process by which leadership decisions mold the cultural and ethical climate of the working environment. Conclusively, the results indicate the hypocritical nature of the role played by ethics in leadership under crisis. Instead of trust and cohesion, compassion was often perceived as fake or calculated, which annihilates the trust it is supposed to provide. The long-term side effects on the employees were disengagement and withdrawal of efforts, and loss of loyalty. These findings support the idea that leaders should not keep on adopting symbolic or selective ethics but adopt the types of practices that support aligning words and practices so that compassion is not only a rhetorical tool, but part of living organizational reality.

5 Discussion

The results of the current research provided an understanding of the conflicting overlap of psychopathy, ethics, and organizational leadership during crisis conditions. At the heart of this paradox lies what can be described as “calculated compassion”—a deliberate performance of ethical concern that often conceals self-serving motives. His duality tests and validates the literature on leadership ethics and darker aspects of leaders.

5.1 Interpretation of findings

Prior literature has determined that crises in organizations create pressures that increase oversight of leadership behavior, which frequently highlight dissonance within moral posturing and pragmatic decision making (Menghwar et al., 2025). Evidence shown in this work echoes with the view, with leaders purposefully applying moral theater when making layoffs and closure announcements, where they were caring about reputational protection but cared about layoffs being presented as caring. This is in line with the existing studies on moral licensing, which indicate that leaders increase in selective ethical behavior as a way to balance dubious choices (Merritt et al., 2019). Nevertheless, the implications of the findings work against the assumption that ethical rhetoric builds trust. Rather, respondents noted a profound betrayal, which indicated that feigned ethical action could produce more damage than silence.

The anomaly of measured compassion also adds complexity to the study of leadership. Although psychopathy in leaders is commonly equated with callousness (Boddy, 2017), the data presented here indicates that callousness was not the only weapon some leaders used, but ethics themselves were shaped into a weapon by compassion. This implies that psychopathic records are not merely pertaining to lack of sympathy, but also instrumentalization of sympathy when beneficial in a manipulative manner.

5.2 Theoretical implications

The findings of this study advance existing theoretical perspectives in several important ways. (1) Jung’s Shadow Theory: The results demonstrate how leaders project a façade of compassion during crises while concealing destructive motives, extending the Shadow concept beyond the individual psyche to organizational communication. This highlights how collective sensemaking can normalize shadow projections as “ethics,” deepening ethical erosion (2) Trait activation theory: The study shows that crises act as powerful situational cues that activate psychopathic traits, particularly manipulative communication and strategic sympathy. This advances Trait Activation Theory by illustrating how situational demands for “ethical leadership” paradoxically trigger toxic behaviors framed as morality. (3) The Toxic Triangle Theory: The findings refine the Toxic Triangle by emphasizing that followers are not only passive enablers but active interpreters of leaders’ moral theater. Employee sensemaking revealed how susceptibility is produced through betrayal, silence, and survival strategies, suggesting that the triangle is more dynamic and iterative than previously theorized. The findings refine the Toxic Triangle by emphasizing that followers are not only passive enablers but active interpreters of leaders’ moral theater. Employee sensemaking revealed how susceptibility is produced through betrayal, silence, and survival strategies, suggesting that the triangle is more dynamic and iterative than previously theorized.

5.3 Practical implications

To organizations, the findings have imminent lessons. Human Resources and crisis management units need to be aware of the indicators of performative ethics- which entail excessive use of symbolic gestures but there is no substantive warrantor to the affected employees. A leader training study should be designed in such a way that it embraces not only moral already updating reasoning but also reflexivity to discern the instances when ethical language is manipulated. Best practices like anonymous feedback by employees and external crisis audits might assist the organizations in knowing the difference between the concern and the fake care (Gurbanli, 2024). Secondly, HR policies are to place emphasis on the deliverance, which means that humane speech is backed by actual operations including honest communication, just severance, and psychological assistance. Organizations reduce long term disengagement and preserve trust by inbuilt measures of detecting performative ethics.

5.4 Future research

There are also a few areas of broadening present within the study. Cross-cultural research might show more about how moral theater and strategic sympathy contract has a different expression in different settings where cultural values of affection and powers are not endemic. As an example, collectivist cultures might perceive staged compassion often as compared to the individualist cultures. Moreover, the psychopathy-ethics paradox may be explored through quantitative studies that involve the quantification of the amounts of relationship between the dark traits of leaders and frequency of performative acts of ethics. This kind of research would help refine the leadership appointment screening, and provide predictive solutions about crisis behavior. Overall, these results indicate that the problem of the paradox of calculated compassion is a theoretical and real-world problem. Ethics can be used as a way of distraction by its leaders yet the ripple effects of betrayal are a testament yet to the fact that authenticity cannot be traded when it comes to leadership. Two implications on scholarship, practice, and further inquiry help to recognize the importance of entertaining the necessity to keep the real compassion in leadership practice on the ground.

6 Conclusion

This paper reviewed the psychopathy and ethics paradox in organizational management in the face of a crisis and with reference to the event of calculated compassion. The results showed that leaders tend to commit moral theater, involving a politically-aimed practice of acting compassionately to maintain reputations and avoid as much personal responsibility as possible. The latter paradox makes it more difficult to differentiate the ethics of leadership, making it clear that psychopathy is not merely the lack of empathy but the insurgence of using it as an instrument.

This study has three contributions. First, it adds to the literature base on leadership and the theory of paradox since it demonstrates how paradoxical features, such as being a psychopath and an ethical leader, can co-exist in calculated manners. Instead of perceiving them as mutually exclusive, this study demonstrates that leaders can manage tensions by maneuvering moral stories. Second, it highlights the devastating organizational consequences of such behavior, particularly trust erosion and long-term disengagement. The earthquakes of deceit that happened in this research support the notion that feigning compassion is not neutral but rather devastating. Third, the research provides HR, leadership training, and crisis management implications. To identify and avoid the presence of performative ethics, mechanisms of accountability, feedback loops, and independent audits are necessary.

Ultimately, the study points to a larger ethical challenge: safeguarding true compassion in leadership. Crises are the periods when the organizations become the most vulnerable, and employees seek leaders who will both make decisions and endorse it with sincerity. When caring is staged, then the ethical boundaries of the organization are broken. The responsibility, therefore, lies in cultivating structures that prioritize genuine care over reputational strategy. As leadership keeps changing in highly dynamic setting, the need to ensure that the an organization not only trains leaders in ethical reasoning, but also makes them answerable to a genuine application grows louder. It is only then that the paradox of calculated compassion can be tackled and trust can be put back in those places where it can have been the most.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because in accordance with the British University in Dubai (BUiD) Ethics Committee guidelines, the raw interview transcripts generated for this study cannot be made publicly available at this stage due to confidentiality and privacy restrictions. Access to the data is strictly limited to the principal investigator and supervisory team, as outlined in the approved ethics application. However, as part of the ongoing doctoral thesis project, refined and anonymized transcripts that cover the broader research (including the data relevant to this article) will be published alongside the final thesis. This thesis will be deposited in the university’s repository by next year, ensuring transparency and eventual public accessibility. Thus, while raw transcripts remain restricted in compliance with ethical regulations, the finalized and refined versions will become available through the thesis, providing a reliable source of verification and further scholarly use. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to AA, YWJkZWxheml6LmFsb3dhaXNAaWNsb3VkLmNvbQ==.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the British University in Dubai. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

AA: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. AS: Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alowais, A. A. (2024). The ethical dilemma of profit: Evaluating the triple bottom line and the role of moral conscience in business decisions. J. Ecohuman. 3:7143. doi: 10.62754/joe.v3i8.5310

Alowais, A. A., and Suliman, A. (2025a). Can the employee Dark Triad act as a moderator of sustainability? A PRISMA systematic review. TPM – Test. Psychometr. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 32, 669–685.

Alowais, A. A., and Suliman, A. (2025b). The influence of leader Dark Triad on employee Dark Triad in higher education institutions. TPM – Test. Psychometr. Methodol. Appl. Psychol. 32, 523–541.

Alowais, A. A., and Suliman, A. (2025c). When the darkness consolidates: Collective Dark Triad leadership and the ethics mirage. Merits 5:21. doi: 10.3390/merits5040021

Babiak, P., and Hare, R. D. (2006). Snakes in suits: When psychopaths go to work. Regan Books/Harper Collins Publishers.

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 3, 193–209. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3

Benedict, M., Quezada-Horne, N. M., Bender, D. A., Campbell, T., and Larkin, H. (2024). Breaking the chains: Understanding the damaging effects of institutional betrayal in social work. Families Soc. J. Contemp. Soc. Serv. doi: 10.1177/10443894241291104

Bieńkowska, A., and Tworek, K. (2023). Leadership styles and job performance: The impact of fake leadership on organizational reliability. England: Routledge.

Blickle, G., Schütte, N., and Genau, H. A. (2018). Manager psychopathy, trait activation, and job performance: A multi-source study. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 27, 450–461. doi: 10.1080/1359432X.2018.1475354

Boddy, C. R. (2017). Psychopathic leadership a case study of a corporate psychopath CEO. J. Bus. Ethics 145, 141–156. doi: 10.1007/s10551-015-2908-6

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Brown, M. E., and Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quar. 17, 595–616. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., and Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Proc. 97, 117–134. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.002

Brunell, A. B., and Hermann, A. D. (2024). Understanding and coping in social relationships with narcissists. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Burhan, Q. U. A., and Malik, M. F. (2025). The dark spiral: Exploring the impact of employee exploitation on cutting corners, unraveling the link through negative emotions and moral disengagement. Bus. Process Manag. J. 31, 556–577. doi: 10.1108/BPMJ-03-2024-0186

Chunxia, Z., Fei, W., and Wei, F. (2022). Exploring the antecedents to the reputation of Chinese public sector organizations during COVID-19: An extension of situational crisis communication theory. Front. Psychol. 13:818939. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.818939

Clementson, D. E., and Beatty, M. J. (2021). Narratives as viable crisis response strategies: Attribution of crisis responsibility, organizational attitudes, reputation, and storytelling. Commun. Stud. 72, 52–67. doi: 10.1080/10510974.2020.1807378

Coombs, W. T. (2007). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications.

Dzoba, O. (2024). Corporate management of enterprises: A value-oriented approach. Ekon. Anal. 34, 190–199. doi: 10.35774/econa2024.02.190

Fairhurst, G. T., and Putnam, L. L. (2023). Performing organizational paradoxes. England: Routledge.

Fayezi, S. (2022). “Paradox theory,” in Handbook of theories for purchasing, supply chain and management research, eds W. Tate, L. Ellram, and L. Bals (Seattle, WA: Association for Library and Information Science Education (ALISE)), 221–247.

Feghali, K., Najem, R., and Metcalfe, B. D. (2025). Greenwashing in the era of sustainability: A systematic. Corp. Governance Sustainabil. Rev. 9, 18–31. doi: 10.22495/cgsrv9i1p2

Frankel, M. (2025). Female narcissism is often misdiagnosed’: How science is finding women can have a dark streak too. London: The Guardian.

Gatti, L., Seele, P., and Rademacher, L. (2019). Grey zone in–greenwash out. A review of greenwashing research and implications for the voluntary-mandatory transition of CSR. Intern. J. Corp. Soc. Responsibil. 4, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s40991-019-0044-9

Gkeredakis, M., Lifshitz-Assaf, H., and Barrett, M. (2021). Crisis as opportunity, disruption and exposure: Exploring emergent responses to crisis through digital technology. Inform. Organ. 31:100344. doi: 10.1016/j.infoandorg.2021.100344

Guest, G., Namey, E., and Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One 15:e0232076. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

Gurbanli, J. (2024). Impression management following a major crisis event: Structured literature review. Master thesis. Available online at: https://unitesi.unive.it/handle/20.500.14247/16571

Hannah, S. T., Uhl-Bien, M., Avolio, B. J., and Cavarretta, F. L. (2009). A framework for examining leadership in extreme contexts. Leadership Quar. 20, 897–919. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.09.006

Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., and Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qual. Health Res. 27, 591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344

ISTSS (n.d.). International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies - guidance used for crisis-related trauma frameworks.

Jefferson, K., Stanhope, K. K., Jones-Harrell, C., Vester, A., Tyano, E., and Hall, C. D. X. (2021). A scoping review of recommendations in the English language on conducting research with trauma-exposed populations since publication of the Belmont report; thematic review of existing recommendations on research with trauma-exposed populations. PLoS One 16:e0254003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0254003

Joubert, K. (2022). A Systematic review: Psychopathy and personality in subclinical populations. Doctoral dissertation, New Zealand: The University of Waikato.

Jung, C. G. (1959). Aion: Researches into the phenomenology of the self. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kallio, H., Pietilä, A. M., Johnson, M., and Kangasniemi, M. (2016). Systematic methodological review: Developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J. Adv. Nurs. 72, 2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031

Lapointe, É, Vandenberghe, C., and Fan, S. X. (2022). Psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism and commitment among self-initiated expatriates vs. host country nationals in the Chinese and Malaysian transnational education sector. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 39, 319–342. doi: 10.1007/s10490-020-09729-7

Li, S., and Chen, Y. (2018). The relationship between psychological contract breach and employees’ counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effect of organizational cynicism and work alienation. Front. Psychol. 9:1273. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01273

Menghwar, P. S., Homberg, F., Zaidi, Z., and Alam, A. (2025). Rethinking crisis as expected: Stakeholder leadership in navigating ethical dilemmas and avoiding polycrises. J. Bus. Ethics doi: 10.1007/s10551-025-06037-2

Merritt, A. C., Effron, D. A., and Monin, B. (2019). Moral self-licensing: When being good frees us to be bad. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Comp. 4, 344–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00263.x

Mohd Fauzi, P. S. L. (2025). The influence of emotional intelligence on project leadership effectiveness. Available online at: https://digitalcommons.harrisburgu.edu/dandt/72/. (accessed August 20, 2025).