- School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom

This paper presents an exploration of the lived experiences of parents whose children have been exposed to the use of restrictive practices (RPs) in schools in England. The research utilized Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis to provide a deep and interpretative understanding. Semi-structured interviews were used to elicit the lived experiences of five parents, whose children had experienced a range of RPs in school. The analysis produced three major themes which centered around the power imbalances, the emotional labor and the practical consequences of RP use. The findings are discussed in the context of neoliberalism, and key implications for practice, research, and policy are reflected.

Introduction

The current context

Behavior in schools is a persistent concern in the UK, and the data suggests that reports of challenges to behavior management continue to rise (Bett, 2024; Education Support and Public First, 2023; Education Support and YouGov, 2023, 2024; IFF Research and IOE and UCL's Faculty of Education and Society, 2024; McLean et al., 2024; Ofsted, 2023; Scales et al., 2024; Sharma and Tate, 2023). This has implications for the school community, with recent reports stating that behavior is impacting children's feelings of safety (Department for Education, 2024) and teacher retention (Teacher Tapp and SchoolDash, 2024), as well as teacher workload (McLean et al., 2024) and wellbeing (Education Support and YouGov, 2024). Additionally, research indicates that many teachers are struggling within the current context to meet the needs of children with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) (Fearon et al., 2024; Rainer et al., 2023; Teacher Tapp and National Education Union, 2024) and mental health needs (Burtonshaw and Dorrell, 2023; Education Support and YouGov, 2023; Rainer et al., 2023).

Faced with increased pressure to manage behavior, many schools have resorted to harsh and inflexible behavior policies (Atherton and Boyle, 2022; Rainer et al., 2023). This has led to a suspected rise in punitive discipline approaches, such as the use of restrictive practices (RPs). The Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) (2021, p. 4) defines a RP as “an act carried out with the purpose of restricting an individual's movement, liberty and/or freedom to act independently.” Within the context of schools, this can include:

• “Physical restraint – direct physical contact between the carer and person (e.g., being held on the floor);

• Seclusion – supervised containment or isolation away from others in a room the child is prevented from leaving (e.g., locking the person in a room);

• Mechanical restraint – materials or equipment used to restrict or prevent movement (e.g., arm splints);

• Blanket restrictions (including lack of access to certain places, belongings or activities);

• Chemical restraint – the use of medication in response to someone's behavior (e.g., the use of sedative or antipsychotic medication such as Risperidone in response to behavior that challenges rather than due to a diagnosis of psychosis)” [Challenging Behavior Foundation (CBF), no date].

Current guidance produced by the Department for Education and Department of Health and Social Care (2019, p. 15) promotes the use of proactive, evidence-based strategies to reduce the need for RPs and states that the use of restraint should be used as a last resort and when it is “necessary to prevent serious harm.” Although the UK government is currently reviewing the guidance on RPs following an open consultation in 2023 (Department for Education, 2023), at the time of writing, the guidance remains non-statutory. This means that government recommendations on best practices regarding the use of RPs in schools lack accountability and have resulted in inconsistent approaches across school settings (Equality and Human Rights Commission, 2021).

The impact of RPs on children

The evidence base examining the impact of RPs on children is in its infancy, and the majority of published research focuses on the use of seclusion specifically (Barker, 2019; Barker et al., 2010; Condliffe, 2023; Gilmore, 2013; Sealy et al., 2023). A recent survey of 560 parents and carers from across England, whose children have lived experience of restrictive practices being used against them in educational settings, found that:

• Ninety percentage of respondents reported that their child had been psychologically harmed from the use of restrictive practices in schools, and

• Forty eight percentage of respondents reported that their child had been physically harmed from the use of restrictive practices at school (International Coalition Against Restraint and Seclusion, 2023).

Previous UK reports support this. For example, a briefing paper by Wilton (2020) outlines how RPs can lead to a harmful cycle of trauma, behavioral escalation, increased use of RPs and further psychological damage.

However, the peer-reviewed research paints a more complex picture. Although the majority of articles indicate that children believe that RPs can be detrimental to their overall wellbeing (Barker, 2019; Condliffe, 2023; Gilmore, 2013; Hodgkiss and Harding, 2023; Sealy et al., 2023; Willis et al., 2021), some children also perceive the use of RPs to be fair, appropriate and necessary (Barker et al., 2010; Gilmore, 2013; Hodgkiss and Harding, 2023; Willis et al., 2021) and conducive to supporting feelings of safety in school (Hodgkiss and Harding, 2023; Willis et al., 2021). A more detailed analysis of this can be found in Christie and Harding (2025).

The impact of RPs on parents and carers

There is a notable lack of UK research focusing on how RPs impact parents and carers, highlighting a key gap in the literature (Christie and Harding, 2025). To the researcher's knowledge, there is only one peer-reviewed article which explores solely parental perspectives on RPs in the UK (Trippler et al., 2025). Data collected by the Challenging Behaviour Foundation (2019) indicates that RPs can harm the mental wellbeing of parents and may also contribute to increased financial strain and the breakdown of family relationships. Recent research by Trippler et al. (2025), which focuses exclusively on the use of seclusion, mirrors these findings, with parents frequently exhibiting emotional reactions to the use of seclusion. Furthermore, parents in the study reported that they mostly disagreed with the use of seclusion, which led to a breakdown in the relationship between the parents and their child's school (Trippler et al., 2025).

It is also worth noting that the use of RPs is likely to have implications for all those involved, including staff. Although there is a lack of existing evidence, it can be assumed that the use of RPs may contribute toward staff stress and challenges in maintaining trusting relationships with both parents and children. Such pressures, therefore, form part of the relational context within which parents' experiences are situated.

Aims and research question

The current research aims to add to the existing evidence base by exploring the lived experiences of parents whose children have been subjected to the use of RPs in schools. Recent data on home-school relationships indicate that relationships with parents is a major source of stress for school staff (Education Support and YouGov, 2024; Teacher Tapp, 2024) and there is an underlying narrative that places the blame on parents in regards to the challenges with responding to child behavior in school (Education Support and YouGov, 2024; Scales et al., 2024). Similarly, parental voice also indicates that home-school relationships are a cause for concern, however, many parents blame school staff for their children's worsening mental health needs (Burtonshaw and Dorrell, 2023). The majority of classroom teachers report having never received training on how to manage parent relationships (Teacher Tapp, 2024), and existing research indicates that this requires specific skills which may not be well-developed in school staff (Robinson and Le Fevre, 2011). Furthermore, a recent report has highlighted the importance of prioritizing home-school relationships in order to support the wellbeing of children (Rainer et al., 2023). As previously mentioned, Trippler et al. (2025) highlighted that the use of RPs can add further strain to home-school relationships. Therefore, it is essential that we develop an understanding of the lived experiences of parents whose children have been exposed to the use of RPs in school. With this in mind, the current study will explore the following research question:

What are the lived experiences of parents whose children have been exposed to the use of restrictive practices in schools?

Materials and methods

Design

This qualitative study utilizes Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) from a critical realist position. IPA is an inductive method which is underpinned by three key theoretical concepts: phenomenology, idiography and hermeneutics (Smith et al., 2022; Smith and Nizza, 2022).

IPA's commitment to phenomenology means that it places focus on exploring the lived experiences of individuals in the context of a personally significant event (Smith et al., 2022; Smith and Nizza, 2022). The researcher anticipated that parental experiences of RPs in schools would be complex and emotionally charged. Furthermore, IPA research involves a double hermeneutic in which the researcher actively attempts to make sense of the participant, who is trying to make sense of their own experience (Smith and Nizza, 2022). Hence, through a rich interpretative framework, IPA allows for a deep engagement with the participants' emotional and psychological meaning-making, enabling the researcher to illuminate how parents interpret and process these experiences, creating a personal, interpretative insight.

Additionally, in the context of the current study, a parent's meaning-making of their child's experiences with RPs in schools is likely to be deeply personal and different for each parent, based on their context. Hence, IPA's idiographic commitment means that the researcher was able to prioritize the uniqueness of each parent's experience, without the risk of oversimplifying the subjective nature of their accounts.

Alternative qualitative approaches were considered in the initial research design, however, IPA was chosen for its idiographic depth and its focus on the psychological meaning-making of lived experience, offering an original contribution to understand parents' perspectives on RPs.

Participant recruitment

The current study used purposive sampling to recruit participants, which is in line with the current study's aims and IPA's commitment to illuminate the individual experience of a common phenomenon (Smith et al., 2022; Smith and Nizza, 2022). Due to the idiographic focus of IPA studies, a small sample size is recommended to allow for a detailed analysis of each individual account (Smith et al., 2022). Hence, a sample size of 3–6 participants was decided as appropriate.

Participants were recruited through existing parent groups and networks. Initially, recruitment was limited to participants who lived in a specific local authority, however, due to difficulties, recruitment was eventually opened to participants from across the UK. The first author disseminated research invitations to a range of local and UK-wide parent groups and networks. The inclusion criteria for participants were as follows:

• Are or have been, a parent or carer of a child attending a UK school

• Currently lives in the UK

• Has experiences of communicating with schools about the use of restrictive practices with their child

• Is able to provide informed consent.

A self-selecting sample was utilized, drawn from people who responded to the invitation to participate. Following an expression of interest, participants were sent a participant information sheet and a copy of the consent form via email. Five participants were recruited in total. All five participants were based in England. Data collection was halted at the end of 2024 in order to provide the researcher with sufficient time to analyse the data.

Recruiting participants for the current study proved challenging, which likely reflects both the emotional sensitivity of the topic and potential concerns about confidentiality or repercussions when discussing school experiences. While this resulted in a small sample, the sample size was in line with IPA recommendations (Smith et al., 2022) and enabled the development of rich, detailed accounts that align with IPA's idiographic commitment.

Participants

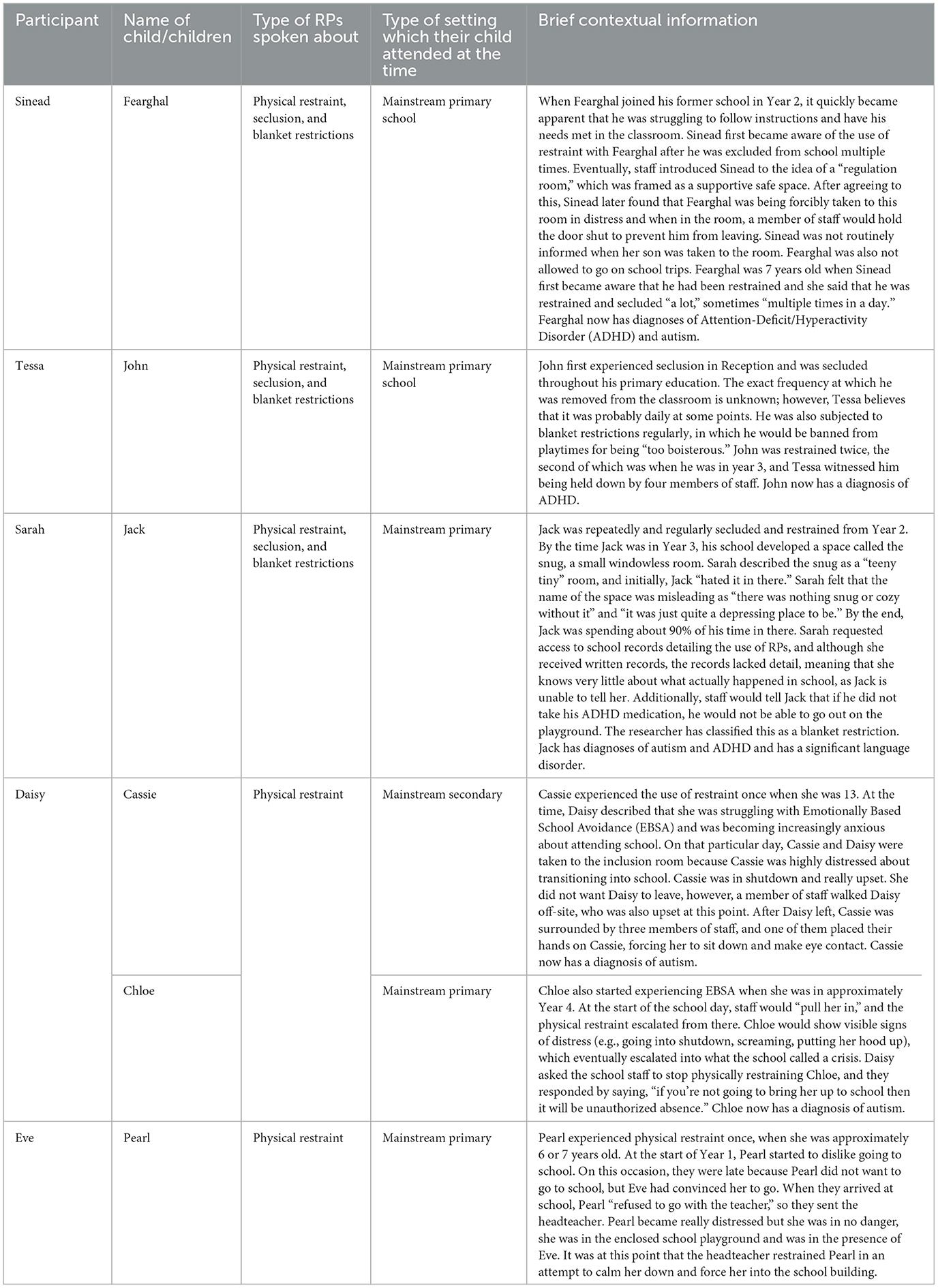

All participants were female, and their children, whom they spoke about, were all still of school age. Table 1 gives an overview of each participant's details. All participants and their children were given pseudonyms to protect their identities. A brief contextual account is provided to give the reader a summary of the participant's unique experiences. All the participants spoke about their experiences in detail, and it would be beyond the scope of the study to provide the reader with a detailed account of each participant's experiences. Hence, the researcher has attempted to highlight just some of the key details. Therefore, the length of the contextual information is not indicative of the detail which each participant provided.

Ethics

This study followed all guidelines set out by the Health and Care Professions Standards of Conduct, Performance and Ethics (Health and Care Professions Council, 2024) and the British Psychological Society Code of Human Research Ethics (British Psychological Society, 2021). The study also complied with the University of Manchester's policy on ethical involvement of human participants in research (University of Manchester, 2021) and full University Research Ethics Committee (UREC) approval was granted. A total of three amendments were made to the original ethics submission to support the recruitment of participants.

Due to the emotive nature of the topic, specific ethical considerations and rigorous procedures were in place to safeguard participants during the data gathering process. A distress protocol was utilized, and the researcher was mindful of safeguarding participants' emotional safety during the interviews. A clear safeguarding procedure was also in place to manage any potential disclosures and was followed as necessary when disclosures were made. Both the distress protocol and safeguarding procedures were developed in line with the British Psychological Society (2021) UREC guidance. A copy of the interview schedule was shared with the participants in advance, allowing them time to prepare. Participants were debriefed at the end of the interview sessions and given a debrief leaflet which contained contact details for support groups and any follow-up that they required. The support contacts provided to the participants were general wellbeing and SEND parent organizations, chosen for neutrality and accessibility. None of the organizations promoted specific educational pathways, such as home education. This approach aimed to ensure that participants could access emotional support and further advice without being influenced by any particular ideological stance.

Data collection

IPA is best suited to data collection methods “that will invite participants to offer a rich, detailed, first-person account of their experiences” (Smith et al., 2022, p. 53). Semi-structured interviews were chosen as an appropriate method as they provide flexibility, whilst ensuring that areas deemed as important are covered, which unstructured interviews may fail to do. An interview schedule (see Appendix 1) was designed to support participants in reflecting on important contextual factors, whilst ultimately encouraging participants to offer a detailed account of their experience. The interview schedule was applied flexibly as a rough guide and as a tool to help participants prepare prior to the interview. However, ultimately, the researcher was guided by the participants' responses. Data collection took place between July 2024 and December 2024. Interviews were conducted via Microsoft Teams and lasted approximately 1 to 2 h. Interviews were recorded using a digital recorder and were transcribed by the researcher.

Prior to the interviews, the researcher had no relationship with the participants. However, as a former teacher and a current Trainee Educational Psychologist (EP), the researcher was able to relate to the experiences of the participants, which is considered to be an important aspect of IPA research (Smith et al., 2022). During the interviews, the researcher was able to draw on key consultation skills, such as demonstrating empathy, deep listening and validating others' perspectives (Royle and Atkinson, 2025), which she had developed during her doctoral studies.

Analysis

Typical IPA data analysis is described as inductive and iterative (Smith et al., 2022; Smith and Nizza, 2022). IPA is primarily concerned with understanding the lived experience of each participant and has a psychological focus on individual meaning-making within their context (Smith et al., 2022). The analytical process of IPA involves a dual interpretation process, referred to as a double hermeneutic (Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2014). Hence, the researcher is actively engaged in interpreting participants' accounts, who are also actively engaged in interpreting and making sense of their own experiences (Smith and Fieldsend, 2021). This process is unique to IPA. The analysis for the current research followed Smith et al.'s (2022) seven-step process. Below is a description of the steps that were undertaken:

• Step one: Reading and re-reading each individual transcript, starting with the first transcript.

• Step two: Exploratory noting.

• Step three: Constructing experiential statements.

• Step four: Searching for connections across experiential statements.

• Step five: Naming the Personal Experiential Themes (PETs) and consolidating and organizing them in a table.

• Step six: Continuing the individual analysis of the other participants (i.e., repeating steps one to five in a linear order for each individual transcript before moving on to the next).

• Step seven: working with PETs to develop Group Experiential Themes (GETs) and subthemes across the participants.

Rigor, trustworthiness, and analysis evaluation

The Journal Article Reporting Standards for Qualitative Research (JARS-Qual) (Levitt et al., 2018) were developed to provide a recommended standard when reporting qualitative research. It was essential for the researcher to establish the validity of the current research for the reader. Hence, as recommended by Smith et al. (2022), the researcher utilized the JARS-Qual to ensure a structured approach to the research process.

The quality of the current study was evaluated using the four markers of high quality in IPA studies as described by Nizza et al. (2021). This was applied consistently throughout the research process to ensure rigor and validity. To further enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, transcripts, researcher reflections, and the various stages of the analysis process were reviewed collaboratively through the process of supervision with the second author.

Due to “the combined effects of amalgamation of accounts, interpretation by the researcher and the passage of time,” member-checking can be counter-productive in IPA studies with multiple participants (Larkin and Thompson, 2011, p. 112). Furthermore, member-checking can be said to contradict IPA's theoretical basis as a hermeneutic phenomenological approach, which emphasizes the researcher's interpretation of participants' lived experiences. Member-checking may therefore compromise this core principle by potentially leading to alterations of the researcher's interpretation based on the participants' feedback (McConnell-Henry et al., 2011). Rather, in line with the recommendations by McConnell-Henry et al. (2011, p. 33), the researcher found that it was preferable to seek clarification during the interview process, with the aim of “asking questions and illuminating the participant's experiences until both parties feel satisfied that a shared understanding has resulted.” The process of seeking clarification was familiar to the researcher, as this is something that she regularly does in her work as a Trainee EP when facilitating Educational Psychology consultations. Within the field of Educational Psychology, consultations are typically focused on “developing a collective understanding of a child and situation” (Nolan and Moreland, 2014, p. 71). Throughout the doctorate, the researcher received ongoing training and supervision in relation to consultation skills, such as summarizing and reformulating. Therefore, the researcher was able to draw on these skills when interviewing participants.

Reflective statement

“Researcher reflexivity implies being aware of our opinions and feelings in relation to the research in an attempt to monitor our influence on outcomes” (Smith and Nizza, 2022, p. 17). This is a core component of IPA, underpinned by its theoretical basis in phenomenology and hermeneutics. IPA researchers are encouraged to consider their own lived experiences and preconceptions, which may influence the interpretation of participants' accounts (Smith et al., 2022). To address this, researchers are encouraged to engage in bracketing, a process that involves acknowledging and setting aside these assumptions as much as possible (Smith et al., 2022). The first author supported this process by maintaining a research diary throughout, which provided a space to enhance self-awareness during data collection and analysis.

At the time of completing this research, the researcher was in her third year of completing a doctorate in Educational Psychology. Prior to commencing the doctorate, the researcher worked as an Assistant EP and, prior to that, as a secondary school teacher. Over the course of her career, the researcher had witnessed the emotional toll which the use of RPs had placed on both parents and children. Furthermore, she has had firsthand experience with the challenges faced by school staff in supporting child wellbeing and meeting the needs of all children. Additionally, the researcher had observed discontent among both school staff and parents regarding home-school relationships. As indicated within the introduction, these experiences align with the existing literature. Hence, when entering into this research, the researcher had to contend with the assumption that parents would experience the use of RPs with their children as ultimately distressing. Therefore, in order to avoid contaminating the research process with these preconceptions, the researcher had to remain mindful of her past experiences throughout the research process and remain open-minded, with a commitment to understanding participants' own lived experiences.

Theoretical orientation

The current study uses IPA as a theoretical framework. IPA is underpinned by phenomenology, hermeneutics and idiography, which together provide a lens for exploring how individuals make sense of personally significant experiences. Rather than imposing an external theoretical model in advance, IPA encourages the researcher to allow broader conceptual insights to emerge inductively from participants' meaning-making (Smith et al., 2022). Therefore, in the current study, theoretical ideas such as neoliberal discourse and Foucauldian understandings of power have been introduced after the analysis, as a consequence of the themes that arose naturally through participants' accounts, rather than serving prior assumptions.

Results

The IPA analysis generated three themes and three subthemes. These are shown in Table 2. The first theme was organized into three subthemes because it covered a wider range of related experiences. Breaking it down in this way helped to show the different parts that made up the overall theme, making the findings easier to follow. The other two themes focused on more specific ideas and therefore did not need to be divided further. This reflects the flexible nature of IPA, whereby the structure of themes depends on what best represents the data rather than the need for symmetrical thematic design.

Power imbalances within a “broken system”: “it's so dehumanizing”

A system which values conformity over compassion and understanding

When discussing their experiences, all parents referred to RPs being used disproportionately as a way to maintain and regain control, which staff prioritized over compassion and understanding. Daisy experienced staff acting in a way that prioritized their own feelings of frustration over the feelings of her daughter:

It was kind of like, they were, they were annoyed that she wasn't doing what they wanted her to do, you know, it was more kind of their frustration that she wasn't behaving the way that they wanted her to. It wasn't done out of, I don't feel it was done out of care. (Daisy)

Daisy speaks with compassion toward her daughter, who “was in shutdown and really upset” at the time of the restraint. Within her account, she describes her daughter as “very gentle” and is confident that she posed “no threat.” Her own compassion contrasts with that of the staff, who appeared “annoyed” at their lack of control over her daughter's actions. Daisy's correction of herself within the phrase “it wasn't done out of, I don't feel it was done out of care” may indicate a level of uncertainty. Likewise, Eve displays potential uncertainty, demonstrated through the use of “I don't know…,” when discussing the moment that her daughter was restrained:

Yeah, I don't know really what her thought process was. I think it was her way of regaining control, actually. I think she felt out of control and didn't… know how to handle it really, it was out of her depth and… as a headteacher, you know, the buck stops with you. (Eve)

In a similar way to Daisy, Eve makes meaning of her experience by attributing the headteacher's actions to a perceived loss of control. In both cases, hesitancy toward their meaning-making may also serve to distance themselves from the actions and decisions of staff. The use of RPs is something which they interpret as morally wrong, and restraining a child is not something which they would choose to do, so they have to guess as to why these choices were made. Despite this, both participants empathized with staff's own emotions and “frustration,” which helped them to tentatively make sense of the experience.

In contrast, Tessa finds it difficult to understand the staff's use of restraint and seclusion in response to her son. Despite recognizing that her son's behavior may have been a challenge to staff, she, like all other participants, believes that the use of RPs was disproportionate:

And historically, his behavior have been, you know, have been wild. It was wild, but at the time he was like 5. When they were… doing all that, holding him on the floor, and yeah, he was 5. I don't know what they thought he was going to do. He's hardly Charles Manson. You know, I don't know what they thought he was going to do (Tessa)

The comparison of her son to Charles Manson serves to highlight the perceived absurdity of her five-year-old son being restrained as if he were extremely dangerous. Her choice of Charles Manson, a well-known cult leader and convicted murderer, emphasizes the disproportionate and irrational response of the staff to her son's behavior. Her inability to empathize with staff in this situation is further reinforced by ending her account with “I don't know what they thought he was going to do.”

Sarah also believes that staff unfairly positioned her son as responsible for wrongdoing, which contrasts with her belief that her son is a “victim” of staff failures:

And as I say, I've got reams and reams and reams of logs, but it's all quite, this is what Jack did. Jack chose not to do this. Jack chose to do this. There was a lot of. It I felt there was a lot of almost victim blaming. (Sarah)

In a similar way to Daisy, Sarah corrects herself when explaining her meaning-making of the staff's treatment of her son. Whereas, Sinead speaks with assertion, despite discussing her own self-doubt throughout her interview, when she states:

It's not a punishment. It's not a threat… You shouldn't be punished for your disability. (Sinead)

This speaks to a wider problem. As a result of her experiences, Sinead appears to believe that children are not only being subjected to RPs disproportionately but that those with additional needs are being discriminated against. Rather than being used as a last resort, RPs were being used as a “threat” to control an unmet need. Tessa perceived this to be a result of a lack of skill on the part of the staff:

They were so inept at dealing with children that have a little bit of, you know, different needs and that their one and only solution was to take him out the classroom (Tessa)

The actions of staff were perceived as inflexible, highlighting the underlying discrimination present within her son's school, where conformity was enforced by actively removing anyone who sat outside the desired norm.

Sarah also discussed the exclusion of children with additional needs:

Somehow is it it was acceptable and you know, if my daughter had been in it, people would have gone, what they, what they doing. But because Jack had issues, it was acceptable. (Sarah)

The difference in how her children were treated and the acceptance of this treatment highlights a lack of tolerance for differences. The use of the word “somehow” highlights her disbelief, demonstrating a contrast with her own compassion toward her son.

During her interview, Daisy reflects on the lack of compassion within the education system as a whole:

If you put their human rights first, the rest follows because at the moment not, we're not doing that. We're not treating them as humans… it's so dehumanizing the system… it doesn't recognize their human rights, it can't see them as human. (Daisy)

The use of the word “we” indicates that we all have become victims of a system which dehumanizes children.

The difficulties of challenging

All participants discussed the difficulties they faced when challenging staff for various reasons. Sarah experienced staff to be defensive when challenged or questioned:

I did question things saying, is this? Are you sure? Yeah, but I didn't really get, you know they were very, they was quite defensive… And I would get wooly sort of responses about, like about the AB, Cs. I never quite got what I wanted to get (Sarah)

The phrase “I never quite got what I wanted to get” suggests that Sarah felt as though staff would give her just enough information to appease her temporarily, but avoided addressing the underlying issue. Tessa had similar experiences, in which she often felt as though she was pacified by staff:

I got a lot of that. Like, to like, they just try and, like, reassure you and pat you on the head and it, you know, we are dealing with that Tessa, for lots of stuff, which they weren't. (Tessa)

Tessa perceived staff to be condescending when interacting with her. Her use of the phrase “pat you on the head” highlights this and produces a visual image which emphasizes the power imbalance between her and the staff.

Similarly to Sarah, Sinead found staff to be defensive when challenged:

It was very hard to to challenge that because the school were quite prickly about. It's like, no, no, we've not pulled. We wouldn't do that. And I was, but I've I've walked in and seen… Two of you pulling him. (Sinead)

In order to avoid potentially difficult conversations, staff attempted to manipulate Sinead into doubting her own perception of reality by denying actions that Sinead had witnessed them doing.

In contrast to the other participants, Daisy takes some of the responsibility for the defensiveness “between parents and school”:

And also this sort of defensiveness that goes on between parents and school like it's your fault. It's your fault. So it makes it a culture where you can't say and discuss. (Daisy)

For Daisy, collaborative communication between school and parents is not just difficult; there is currently a “culture” of blame, which means that you “can't” openly discuss issues, making it impossible to move forward.

Feeling as though you can't challenge staff is something which Eve also discussed:

And she said to me like, why didn't you do anything? It's just like, I just felt like I couldn't because it's like headteacher and you know, it just felt like I had [no] territory. (Eve)

In the moment of experiencing the restraint of her daughter, challenging the headteacher did not feel like an option for Eve. However, her use of the past tense when describing her experience (“I just felt like I couldn't”) suggests that this may not be a feeling that Eve still identifies with and with hindsight, she acknowledges that challenge may have been possible. Eve perceived her daughters' school as a territory where she did not belong, which disempowered her at that moment, leaving her unable to identify alternative responses that challenged the norm of the headteachers' territory. Similarly to Eve, Sinead spoke about how she perceived staff to be “experts” in supporting her child, which disempowered her when she considered challenging them:

“I was kind of putting them a little bit as the experts on supporting my child.” (Sinead)

The statement also conveys a level of unquestioned trust. However, like Eve, Sinead speaks in the past tense, which may indicate that this trust has now been broken.

When discussing the difficulties with challenging staff, Daisy spoke about how power imbalances within the system make making complaints impossible for parents:

Complaints procedure means that you go to the head first. That's just not an option. It's just not an option. They're holding over you whether you get an EHCP, what support they give you in school, whether they're going to put forward for meetings, whether, you're just in such a weak place. (Daisy)

Her repetition of “just not an option” serves to emphasize the difficulties of challenging staff. The use of the phrase “they're holding over you” creates a visual metaphor of physical dominance, which depicts staff as a threatening body, highlighting the vulnerability and submission of the parents who are beneath them. Daisy later discusses how making complaints had very real repercussions for her, which gives weight to her worries about challenging staff:

The system Is that If you make any complaints at all, It disadvantages you… I put In a complaint to the local authority because they refused alternative provision and they put the Education Welfare Office on to me as a result of that. So I retracted the complaint. So I, you know, I said to Ofsted, there's no safe way to raise this (Daisy)

In Daisy's experience, making complaints was not just difficult, it posed a real threat to her psychological safety as she was subjected to additional scrutiny.

Eve also discussed the difficulties parents have when challenging schools, and in her case, the only way she felt she could regain power over the care of her child was to remove her from school:

I was like, right, let's just, like, leave this behind because this seems to be causing all the problems or a lot of the problems. But loads of people spend years like battling or trying to get, you know, especially kids with SEN. And, you know, they spend years kind of trying to work with the system and it's like exhausting. And it's really difficult for them and you know, I feel like in a way, just by removing ourselves from that, we kind of made life like easier (Eve)

Despite removing her and her daughter from the system, Eve empathizes with other parents who have to spend years “battling” to get support for their children.

Internalization and acceptance of constructed norms

Four out of the five participants discussed how the use of RPs has become a normalized response to non-conformity within educational settings. Daisy believes that the system encourages staff to accept that the use of RPs is the “right” way to respond to behavior which is considered to be undesirable:

The system is so powerful… but the system is so powerful and they're saying no, this is right, that you do it and this is happening time and time again to children. (Daisy)

Within this statement, Daisy highlights how common the use of RPs has become in schools (“this is happening time and time again”). For Daisy, the normalization of RPs has led to the “brainwashing” of individuals, who are now unable to consider alternatives to RPs:

And I mean the system, it's so powerful that you kind of need to re-brainwash people into actually even thinking that it could be different like could we question the education system that makes us feel all safe and our children are tucked up every day. (Daisy)

Daisy believes that the normalization and acceptance of RPs within education has led to the narrowing of perceived possibilities. Eve reflects on her own acceptance at the time of her daughter's restraint:

Then at the end of the school day, Pearl just seemed fine and I was so relieved that she wasn't, like, really upset that I just, I didn't say anything to the head. I just kind of went, ohh, I think I even said ohh like you know, thank you for dealing with it (Eve)

Even though Eve had been upset by witnessing the use of restraint, she knew that this was accepted within the boundaries of the school environment and therefore felt unable to say anything. The word “even” highlights her disbelief over her own acceptance at the time. Likewise, Sarah communicates disbelief regarding the acceptance of RPs within schools:

It's interesting, you know, so if you present that on the outside, if I saw a child being manhandled down the road and I could hear the child screaming out you're hurting me. What would I do? Well, I'd probably ring the police… Or I'd go over there, at the very least. Why is it that within a school environment it's it is acceptable? How? How is that acceptable when it's not acceptable? If I was in the garden, I heard my neighbor and I could hear this kid screaming. It would make me go Oh my God. Someone needs do a welfare check or something, make sure they're OK. I don't know where how we've got to the point where it's, because it's within school, it's it (Sarah)

By comparing RPs to child abuse, Sarah highlights how the disproportionate use of RPs has been completely normalized within educational settings. Similar to Daisy, who discussed the “brainwashing” of individuals, Sarah presents a contrast between what is considered “acceptable” in everyday life outside of school and what is considered acceptable within the boundaries of schools.

Sarah also talks about the normalization of RPs within schools:

I don't think they did it out spite. [I] don't think they did it out of hatred for my child. They did it out of complete naivety. (Sarah)

Sarah suggests that staff have internalized norms within educational systems, which present the use of RPs as a reasonable response to children who do not conform. Therefore, staffs are not able to see alternatives; they are naïve to other possibilities.

The normalization of RPs has also become internalized by children:

And I suppose I suppose he's… Always at school had those experiences where he's been like we've been talking about taking out the classroom or told to sit outside facing the wall or spent time in headmasters office and so to him that was just another thing that the school did that was a bit rubbish (Tessa)

Tessa's son appeared to be completely unaffected by the use of RPs and showed no visible signs of distress. For him, the use of RPs was just a normal part of the school day, and he had never known anything different. For Sarah's son, being placed in seclusion had become so normalized that he became almost institutionalized and was unable to cope within a mainstream environment:

So he was in the snug for about 2 years in total, by the end, Year 3 and 4, he was in the snug and then actually, after a time to be fair, he then became unable to leave the snug. You know it went the other way after a time because he just felt too overwhelmed going into classrooms. (Sarah)

Although in some cases spaces in school can be used to support the needs of children, Sarah did not interpret the use of “the snug” as supportive for her son. Instead, “the snug” was used as a seclusion space (see Table 1 for further details regarding “the snug”). Sarah's son appears to have internalized a belief that he was unable to cope in a classroom and had developed psychological and behavioral adaptations, which resulted in him feeling more comfortable when secluded. Daisy also indicates that her daughter had internalized the wider societal and educational discourse about what is acceptable in schools, leaving her unable to discuss and share her experiences:

Interviewer: Yeah. And so before, before this was she ever able to tell you about what was happening in school? Did she ever talk about it?

Daisy: No because I don't think anyone would think it's unacceptable.

The emotional labor of RPs: “it's a really emotive interview”

The use of RPs had an emotional impact on all participants, however, the range of emotions experienced by each of the participants differed. At the beginning of her interview, Sarah announces:

It's a really emotive interview for me because there's an enormous amount of guilt with it… and not that I should feel guilty, but I do feel incredibly guilty for the trauma that my child still has to this day. (Sarah)

By starting the interview in this way, it is clear that Sarah experiences an overwhelming amount of guilt, which stems from the responsibility that she feels as a parent to protect her child from harm. She also talks about the anger she feels as a result of her experience, however, she directs part of the anger inwards, which further reinforces her feelings of guilt:

I still feel it now, I can get really angry about it now, but you know… I think there's a guilt attached to it… guilt and shame… Oh, I feel so guilty. I feel so guilty. Why didn't I? Why? Why? Why did I not fight more? (Sarah)

Within this, it is evident that a conflict exists between what Sarah thinks she should feel (i.e., the cognitive truth) and what she actually feels (i.e., the emotional truth). She speaks in the present tense, which highlights that this is still a present feeling for her and something that she is still living with. Sinead, Daisy and Eve also explicitly describe the guilt that they feel as a result of the distress their children experienced when RPs were used in school. Eve says:

I just felt terrible. I felt like I'd failed my daughter as a parent. Yeah, it's just heartbreaking… which was just very, very upsetting. Really sad. Like you say, it was disempowering. Felt like I'd let her down. Just yeah, it felt really terrible (Eve)

Her use of “as a parent” emphasizes her role as a parent and indicates that she may have internalized societal expectations and pressures about parental responsibility. This was something which Sinead described explicitly when discussing her encounters with school staff:

But it felt a little bit like, this is your fault as a parent bringing this terrible child into school which perhaps made me more subservient in agreeing to things and wanting to… not be… judged as a bad parent. (Sinead)

Sinead internalized societal narratives about parenthood and parenting, which had resulted in an internalized feeling of blame. With time and space to reflect on the situation, Sinead has been able to see how her interactions with school staff often reinforced this internalized self-blame, leaving her feeling helpless and “subservient,” disclaiming that she “felt very isolated.”

Despite feeling morally responsible for their children's wellbeing, Sinead, Sarah, Daisy, and Eve all felt disempowered within their experiences, and therefore their guilt acts as a way to demonstrate that they care and are connected to the experience. Daisy expresses feelings of guilt that are so intense that they are difficult to live with:

I left the house and I just walked and I was sobbing, because I just can't believe it was happening again. Yeah, I don't know how you kind of live with the guilt (Daisy)

Her words depict an image of someone in such despair that they are unable to feel at ease in their own home. However, unlike the other participants, she expresses little doubt or conflict between the cognitive and emotional truth of the situation, and she assumes full responsibility:

I just feel really cross with myself that I've done it to them twice. How did I not learn… I don't know (Daisy)

Daisy blames herself for her children's experiences, and although she empathizes with alternative explanations which may place accountability with staff, she states:

It's a difficult one, isn't it, because I think every parent would like to believe that they haven't done anything wrong. But I think there is some accountability for us as well, you know… we have to kind of hold up our hands (Daisy)

The feelings of guilt experienced by Sinead, Sarah, Daisy, and Eve seem to influence how they perceive themselves as parents. However, despite the feelings of guilt that she feels, Sarah is still able to outwardly acknowledge some of her strengths as a parent:

Anyway, maybe he's a bit lucky that he's got me as a mum who won't give up. (Sarah)

Sarah appears to be able to acknowledge the positive difference that her own determination and resilience have made in her son's life. Whereas, the self-blame and responsibility that Daisy places upon herself have left her in a perpetual state of self-doubt (“you're always questioning if you're right and, yeah, it's not a great place to be”) and has impacted her view of herself as a loving parent:

I was just like, you know, I love you. But how could I tell her I loved her when I had done that to her. I just think it's really difficult. (Daisy)

Similarly to the other participants, Tessa alludes to her powerlessness in the situation, which leads to her becoming “disillusioned” with school:

I just really quickly became completely disillusioned with that school and was like, you know I want to, I have to move him. It's it's rubbish… I don't remember feeling anything other than… Just being really angry (Tessa)

However, in contrast to the other participants, Tessa does not describe feelings of guilt and instead her anger is directed toward the school rather than toward herself. This may be a consequence of her son's lack of visible distress as she repeatedly made reference to her son not being “bothered” by the use of RPs.

In contrast, other participants referenced the emotional impact which RPs had had on their children. For example, Sinead described how RPs left her son feeling scared:

“You know better than me but behavior is communication and that is very clear, loud and clear. You know, I'm, I'm scared.” (Sinead)

Tessa appears to have interpreted her son's behavior as a form of communication, which indicated that he felt unsafe and “scared” in school. Staff responded to this by using RPs, which only further threatened his feelings of safety.

In a similar way to which the use of RPs had led to feelings of guilt for some of the participants, Sarah believes that her son had internalized the dominant narrative about himself as a problem, which led to feelings of shame:

So I have to be absolutely clear, Jack feels an utter sense of shame… the shame which went with this. He didn't want to be like this (Sarah)

Staff's response to the behavior that her son displayed threatened his sense of identity and communicated that there was something wrong with him. This pushed him “very close to having [a] breakdown” and left him feeling as though he no longer wanted to live:

Toward the end he was under [the] desk telling me that he didn't want to be a monster anymore and he wanted to kill himself. So, you know, it really impacted him. (Sarah)

In these cases, there appears to be a link between the participants' guilt and the level of emotional impact that RP's had on their children. Similarly, Daisy's daughters also interpreted their experiences as a result of something wrong with them, leaving them questioning their own identity and feeling isolated, which mirrors Daisy's own self-doubt:

It's massive, massively isolating, because what happens is when as soon as they come out of school… is their confidence goes massively. Like what's wrong with me, you know? Why can't I do what other people can do? (Daisy)

The practical implications of RP use: “It all fell on me”

All of the participants spoke about the impact that RPs had on their day-to-day lives. They all discussed the various sacrifices that they had to make as a consequence of their children's experiences in school. All participants provided examples that indicated the use of RPs placed a strain on their time. Both Sinead and Tessa shared how it took a lot of their time and energy to attempt to work collaboratively with the schools. Sinead felt as though she had achieved some success, but acknowledged that it had taken a lot from her to make it work:

Oh, but it has taken a lot, but it's [a] kind of trusting relationship with communication… but that's also because I've got all the time and energy to do that (Sinead)

Her words suggest that she has had to make sacrifices in other aspects of her life to ensure that she has “all the time and energy” to build a trusting relationship, and without this, she would not be in the same situation. On the other hand, Tessa speaks with frustration as she feels that her efforts were wasted:

You know, and it wasn't like I was being airy fairy with, well, this might work. Well, why don't you try that? Because like I said, I went to town and I got all [the] paperwork from work and literally wrote behavior plans, I wrote, I gave them like ABC type forms for [them] to record incidents so as they could look back and see what might have been the trigger or the start of it so they could try and eliminate triggers and and therefore make the behaviors less frequent and I gave them, I gave them everything and nothing. They didn't use any of it at all (Tessa)

The length of Tessa's description and the phrase “I went to town” are indicative of the time and effort that she sacrificed to attempt to support school. The phrase “I gave them everything and nothing. They didn't use any of it at all” highlights again how much she feels she provided and how let down she feels by the staff.

For Eve, the use of RPs acted as a pivotal life moment which completely changed her day-to-day life as she now homeschools her daughter:

So I home educate my daughter now and and you know, that was like the best decision I've ever made. But after [the restraint], I was like… I'm not gonna force you, because if you get there and you're unhappy, I know what's gonna happen. And so I'm not, I don't wanna put you in that position again. It was definitely the beginning of the end for me. (Eve)

She describes the moment that her daughter was restrained as “the beginning of the end” of her alliance with the school. She later says:

For me it was just kind of, it was the start of the kind of a steeper decline, I think in that that it was just difficult to come back from that really. (Eve)

This demonstrates how her experience has completely impacted on her perception of school. Her words convey a distrust of school staff to keep her daughter safe, which ultimately resulted in her removing her daughter from school completely.

Sarah describes her experience as a battle:

We battled and battled and battled with the LA (Sarah)

Her repetition of the word “battled” emphasizes how difficult this was for her. She felt as though she was fighting for her son. Like Sinead and Tessa, Sarah describes her experience in a way which implies that it also placed a huge strain on her time and energy:

I had to go to tribunal… and I then wrote to every single director at my Council, I wrote to my MP, I wrote to my counselor, I wrote to everyone [at the local select committee] and I told them how they weren't applying the law. And how they were affecting my son (Sarah)

Her repetition of “I wrote” acts to emphasize the amount of time and energy she put into advocating for her son. On top of this, fighting for her son also had a huge financial impact:

We paid 10s of thousands of pounds for legal advice. I think we paid about 17,000 in the end to get him out of the school because I was quite angry. Yeah. Killed us. Luckily we've got some in-laws who helped us out. But yeah, it was pricey. Really pricey… I could barely work. I could barely work. (Sarah)

The phrase “killed us” is particularly prominent as it shows the level of impact the experience had on her day-to-day life, and the use of “us” suggests that the impact extended beyond her and to the wider family. Her words also shed light on how the experience impacted her career, which she reinforced through repetition. This likely placed a further financial strain on the family.

The impact on work is something that all the participants discussed. For Tessa, she was only able to continue working thanks to the support provided by friends and family:

In amongst all this, I'm, I'm trying to work full time and so is my husband. It was, it was hard. And I called in so many favors from like my mum, my friends, my brother, my sister-in-law. (Tessa)

For Eve, homeschooling her daughter limited her availability and restricted her freedom, which she described as “frustrating”:

I love home, home ed and it's like great like you know, we have a good time. But it is pretty restrictive in terms of like work and stuff. Yeah. And so yeah, that's the only downside. Just putting those sort of things on hold a bit or being or be, like, very limited in what I can do. So, yeah, yeah, that is a bit frustrating. Or makes it a bit tricky. (Eve)

Sinead describes how she had to completely stop working to manage the demands placed upon her time and energy from school:

But again, that's tricky because it means I can't work or because I need to be able to get to the school, instantly… and I would be worried to meet anyone what would take me too far away from being able to constantly get there (Sinead)

For Daisy, her experience was life-changing because not only had she lost her job, she lost her career:

I lost my career like because I couldn't, I can't work in schools anymore because that's all, it's tainted. It's, I don't believe in the system. I don't wanna be part of it anymore. (Daisy)

The impact which RPs had on the participants' time, energy and capacity to work did not appear to be acknowledged by the school staff. This unseen consequence further acts to reinforce power imbalances by placing additional strains on day-to-day life.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to illuminate the lived experiences of parents whose children have been exposed to the use of RPs in schools. The findings show how the manifestation of power imbalances between the parents and children in this study, and school staff, have had emotional and practical consequences for the participants. While this study focuses on parental experience, it is important to recognize that staff and senior leaders also operate under considerable emotional systemic pressures, which may influence their use of and response to RPs. Understanding these interacting pressures helps explain the relational tensions that parents describe.

All the participants discussed how RPs were used to exclude those who did not conform to the ideal norms within schools. Neoliberalism is an economic and political ideology that favors free markets, minimal government intervention, and deregulation. Since the 1980s, neoliberal values have influenced the UK education system, embedding market principles, individualism, and competition into policy and practice (Norris, 2022). As discussed by James et al. (2024), the neoliberalization of education in much of the Western world, including the UK, has resulted in a system which values efficiency, productivity and order. This has led to the development of “taken-for-granted assumptions, attitudes, and beliefs” (Fraser and Shields, 2010, p. 7), or discourses, which guide dominant social and educational practices and promote conformity.

The concept of discourse was introduced by Foucault (2013) as systems of knowledge and rules that define what is considered true and meaningful at a given time. Neoliberal discourses have encouraged a focus within education on individual impairment (Dudley-Hicks et al., 2024), which positions the individual teacher, parent or child at fault if they fail to conform to the constructed norm, meaning that schools maintain their power and protect their authority by placing blame on the individual (Foucault, 2019). Foucault related the idea of discipline with surveillance and believed that within a society in which we are constantly watched, those who compromise the integrity of the dominant discourse are judged and punished (Mauri, 2018). This has resulted in the rise of zero-tolerance disciplinary practices, which attribute behaviors that challenge to individual dysfunction (Weissman, 2015) and discourage compassionate approaches by obscuring attention to structural, systemic, and environmental barriers often faced by the individual (James et al., 2024; Weissman, 2015). This contrasted with participants' own compassion toward their children, resulting in a mismatch between parental warmth and care and the decontextualized professional objectivism conveyed by schools, as discussed by Hess et al. (2006).

One way to look at this is that the participants' experiences within the current study suggest that under increased pressure to maintain order, meet behavior targets and improve grades in line with neoliberal ideologies (Ball, 2003; Duarte and Brewer, 2022; Sturrock, 2022), school staff have likely internalized and reproduced the dominant discourses. This means that they may have interpreted behavior which challenges through the lens of threat and non-compliance, and therefore, the use of RPs has become a normalized routine response to this behavior. Furthermore, all the participants described their children as having additional needs which their children's schools failed to meet, resulting in the use of RPs. Existing research has explained the marginalization of children who are unable to conform as a manifestation of structural violence (Brissett et al., 2025; Weissman, 2015), referring to the systemic harm caused by institutions which disproportionately impact certain groups by limiting their access to opportunities. As described by Weissman (2015, p. 217), as a society, we are “bombarded with messages about individual merit and how anyone can make it if they try,” which further perpetuates a message of individual fault. Therefore, it is probable that parents and children are disempowered should they attempt to question or challenge the inequality which certain groups of children experience when in school.

Furthermore, staff defensiveness was identified as a key factor which contributed to the difficulties participants encountered when challenging the use of RPs. This could be interpreted using self-determination theory, which states that a person must experience three psychological core needs to promote motivation and overall wellbeing: autonomy, competence and relatedness (Deci and Ryan, 1985, 2000). The push toward inflexible behavior policies and the increased demands placed on teachers mean that the system may already threaten these core needs for teachers (Acton and Glasgow, 2015). When parents raise concerns with staff about the use of RPs, this may act as a further threat to their already fragile core needs, triggering defensiveness. This is in line with research by Addi-Raccah and Arviv-Elyashiv (2008), who found that the marketization of schools in line with neoliberal ideology gave weight to parental views, leaving staff feeling vulnerable to the influence of parental scrutiny, which threatened their professional domain.

The playout of power resulted in both emotional and practical consequences for the participants within the current study. Most of the participants discussed in detail the distress that RPs caused their children. The link between care receiver distress and caregiver distress has been shown in previous research (Dudley-Hicks et al., 2024; Paradiso and Quinlan, 2021). This link was evident in the current research, with the level of parental distress seeming to closely mirror the level of distress participants witnessed in their children. Most significantly, parental distress manifested as strong feelings of guilt (Challenging Behaviour Foundation, 2021). All participants discussed how they had been unable to effectively collaborate with school staff to enact change for their children, despite attempting to advocate for their children's unmet needs. This resulted in situations in which the participants felt that they were required to passively comply with systems which positioned their children as the problem (Hess et al., 2006). The parents within the current study conveyed a core need to protect their children from harm, which aligns with previous research (Dudley-Hicks et al., 2024). The guilt that the parents experienced is therefore unsurprising when contextualized within a system which disempowers them from fulfilling this core need.

In a similar way to that described by the parents in a report written by the Challenging Behaviour Foundation (2021), the participants in the current study received little emotional support from services or professionals, and their stress was further compounded by having to independently navigate complex educational systems. This acted as a burden on their time and, for some parents, had significant financial implications. Additionally, all participants discussed how the responsibility of advocating for their children, alongside a lack of support from school, placed a strain on their ability to work, which could only be managed by drawing on support from family and friends, if that support was available. These findings are in line with previous research findings which demonstrate how educational systems can act to further disempower parents (Bell and Craig, 2023; Bodfield and Culshaw, 2024; Challenging Behaviour Foundation, 2019, 2021; Dunleavy and Sorte, 2022; Feingold and Rowley, 2022; Gray et al., 2023; Martin-Denham, 2022).

Implications for practice and conclusions

This study offers an interpretative phenomenological account of how parents make sense of their children's experiences of RPs in schools. The findings reveal the emotional and relational impact of these practices, highlighting how inflexible behavior policies and an emphasis on individual impairment can disempower parents and strain home-school relationships. Consistent with previous research showing that positive collaboration between families and schools supports improved child outcomes (Fu et al., 2022; Kaplan Toren, 2025; Russell and Qiu, 2024), the current study stresses the importance of fostering mutual trust, empathy and partnership between parents and educational professionals. From an interactionist perspective, Bronfenbrenner's (1979) ecological systems theory reminds us that a child's development is influenced by multiple interconnected environments and, therefore, the impact of RPs extends beyond the classroom to shape family wellbeing.

As a consequence, the current study advocates for further criticality surrounding the use of RPs in schools and has several implications for professionals supporting children and families, including those within educational psychology practice. EPs are well placed to build authentic connections with school staff, which develop their feelings of relatedness, allowing them to challenge school practice without posing a threat to staff feelings of autonomy and competence (Deci and Ryan, 1985, 2000). A philosophy of curiosity has been shown to encourage staff thinking to move beyond deficit-based, within-child explanations, and is often learned through interactions with more experienced staff (Halliwell and Miller, 2025). Hence, when interacting with school staff, EPs may be able to support a philosophy of curiosity within school communities by modeling more inquisitive thinking, which may create greater flexibility in staff responses to behavior.

Furthermore, the manifestation of power was a significant finding within the current study, and therefore, in line with previous research (Bodfield and Culshaw, 2024), the findings suggest that it is essential for those working in education to spend more time reflecting on how power operations can impact individuals. The Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF) is a paradigm which offers a method for understanding emotional distress. It focuses on how power can manifest to impact an individual's life, the threat that power can pose to an individual and how an individual makes sense of these threats (Johnstone and Boyle, 2018). In their recent study, Nikopaschos et al. (2023) found that implementing the PMTF into team formulation in a clinical setting contributed to significant reductions in the use of restraint and seclusion with patients. However, although the PTMF was originally designed for use within clinical settings, researchers have also noted its application to the education system (Bodfield and Culshaw, 2024) with previous research recommending for “wider dissemination of the principles of the PTMF to the education system in the UK” (Bodfield and Culshaw, 2024, p. 13). In line with this, research by James et al. (2024) has found that the PMTF supports parents of children with additional learning needs in making sense of their threat responses in ways that reduced self-blame. When considering the development of positive home-school relationships, previous research has called for a shift away from parental blame (Broomhead, 2013) and has highlighted the importance of staff reflection on their own practice and approachability (Broomhead, 2018). The PMTF could therefore act as a useful lens to interpret the impact of power operations on both children and parents, to respectively, reduce the use of RPs, and encourage positive home-school relationships.

Limitations

While generalizability is not the primary aim of this research, the small sample size does limit the extent to which findings can be applied beyond the study context. However, in line with the aims of IPA research and guidance from Smith et al. (2022), the findings are situated within existing research in the discussion, which demonstrates their transferability.

Additionally, the recruitment process may have impacted the results. For example, the research was advertised through parent groups, many of which described themselves as supporting parents of children with SEND and neurodiversity. The participants in the current study discussed how their children's needs were often unidentified for many years. Hence, it is likely that many children experiencing the use of RPs in school do not have identified additional needs, and therefore, their parents may not be accessing parent groups. This means that many suitable participants may have missed out on the opportunity to express their interest in the current research.

Furthermore, within their accounts, many participants emphasized how their access to resources and social capital enabled them to challenge and respond to the use of RPs. However, they also acknowledged that for many parents, this is not the case, and it is often those parents who are most disempowered whose voices are missed within research. Despite the validity of this point, IPA research does not aim to recruit a representative sample (Smith et al., 2022) and therefore, these points are unlikely to impact the quality or validity of the findings.

Lastly, it should be noted that the above discussion presents the researchers' interpretation of the participants' interpretations of their experiences, in line with the double hermeneutics required within IPA research. Hence, the researcher recognizes that there are other possible ways in which the results of this study may have been interpreted, and the current paper presents only one interpretation.

Future research and policy considerations

In line with the limitations discussed above, future research may wish to examine parental experiences on a larger scale with the aim of producing generalizable findings. Additionally, future research may wish to expand the scope of the current study by considering the demographics of the sample and exploring other recruitment options.

The findings of the current study offer a unique insight into the experiences of parents, highlighting how current policy and guidance implemented in the education system often act in ways that disempower parents. This has implications for future policymakers who may wish to consider how parents can be protected, empowered and better informed in future education policy and guidance.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation. However as per the University of Manchester's Research Data Management Policy, the raw data will only be available for 5 years after the completion of the research.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by University Research Ethics Committee (UREC), University of Manchester. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

CC: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EH: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The research was conducted as part of the doctorate in educational psychology, which was funded by the Department for Education.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Acton, R., and Glasgow, P. (2015). Teacher wellbeing in neoliberal contexts: a review of the literature. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 99–114. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6

Addi-Raccah, A., and Arviv-Elyashiv, R. (2008). Parent empowerment and teacher professionalism: teachers' perspective. Urban Educ. 43, 394–415. doi: 10.1177/0042085907305037

Atherton, L., and Boyle, R. (2022). The Zero Tolerance Behaviour Policy Paper: Understanding Zero Tolerance Behaviour Policies: The National SEND Forum. Available online at: https://engageintheirfuture.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/16070-ZTP-Briefing-Paper-30.03.22-2.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Ball, S. J. (2003). The teacher's soul and the terrors of performativity. J. Educ. Policy 18, 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065

Barker, J. (2019). ‘Who cares?' Gender, care and secondary schooling: ‘accidental findings' from a seclusion unit. Br. Educ. Res. J. 45, 1279–1294. doi: 10.1002/berj.3562

Barker, J., Alldred, P., Watts, D. M., and Dodman, H. (2010). ‘Pupils or prisoners? Institutional geographies and internal exclusion in UK secondary schools'. Area 42, 378–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4762.2009.00932.x

Bell, C., and Craig, M. O. (2023). Suspended, restrained, and secluded: exploring the relationship between school punishment, disability, and black and white parents' health outcomes. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 153:107119. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2023.107119

Bett (2024). Student behaviour report 2024. Available online at: https://uk.bettshow.com/student-behaviour-report (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Bodfield, K. S., and Culshaw, A. (2024). Applying the power threat meaning framework to the UK education system. Pastor. Care Educ. 1–20. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2024.2316589

Brissett, D., Rankine, J., Mihaly, L., Barral, R., Svetaz, M. V., Culyba, A., et al. (2025). Addressing structural violence in school policies: a call to protect children's safety and well-being. J. Adolesc. Health 76, 752–756. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2025.01.027

British Psychological Society (2021). BPS Code of Human Research Ethics. Available online at: https://www.bps.org.uk/guideline/code-ethics-and-conduct-0 (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Broomhead, K. (2013). Blame, guilt and the need for ‘labels'; insights from parents of children with special educational needs and educational practitioners' Br. J. Spec. Educ. 40, 14–21. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12012

Broomhead, K. E. (2018). Perceived responsibility for developing and maintaining home–school partnerships: the experiences of parents and practitioners. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 45, 435–453. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12242

Burtonshaw, S., and Dorrell, E. (2023). Listening to, and learning from, parents in the attendance crisis: public first. Available online at: https://www.publicfirst.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/ATTENDANCE-REPORT-V02.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Challenging Behaviour Foundation (2019). Reducing restrictive intervention of children and young people: case study and survey results. Available online at: https://www.challengingbehaviour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/reducingrestrictiveinterventionofchildrenandyoungpeoplereport.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Challenging Behaviour Foundation (2021). Broken: the psychological trauma suffered by family carers of children and adults with a learning disability and/or autism and the support required. Available online at: https://www.challengingbehaviour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/brokencbffinalreportstrand1jan21.pdf (Accessed June 13, 2025).

Challenging Behaviour Foundation (n.d.). Restraint, seclusion and medication. Available online at: https://www.challengingbehaviour.org.uk/what-we-do/strategic-influencing/restraint-seclusion-and-medication/ (Accessed January 10, 2023).

Christie, C., and Harding, E. (2025). A scoping review of staff, student, and parent perspectives and experiences of restrictive practices in educational settings. Pastor. Care Educ. 1–17. doi: 10.1080/02643944.2025.2533286

Condliffe, E. (2023). 'Out of sight, out of mind': an interpretative phenomenological analysis of young people's experience of isolation rooms/booths in UK mainstream secondary schools. Emot. Behav. Diff. 28, 129–144. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2023.2233193

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. Perspectives in social psychology New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

Department for Education (2023). Use of reasonable force and restrictive practices in schools: GOV.UK. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/use-of-reasonable-force-and-restrictive-practices-in-schools (Accessed April 30, 2023).

Department for Education (2024). National behaviour survey: findings from Academic Year 2022/23. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6628dd9bdb4b9f0448a7e584/National_behaviour_survey_academic_year_2022_to_2023.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Department for Education and Department of Health and Social Care (2019). Reducing the need for restraint and restrictive intervention. Available online at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/812435/reducing-the-need-for-restraint-and-restrictive-intervention.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Duarte, B. J., and Brewer, C. A. (2022). “We're in compliance”: reconciling teachers' work as resistance to neoliberal policies. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 30. doi: 10.14507/epaa.30.6173

Dudley-Hicks, D., Gail, J., and Morgan, G. (2024). Parenting a child with an intellectual disability: mapping experiences onto the power threat meaning framework. Disab. Soc. 40, 1597–1621. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2024.2369646

Dunleavy, A., and Sorte, R. (2022). A thematic analysis of the family experience of British mainstream school SEND inclusion: can their voices inform best practice?. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 22, 332–342. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12571

Education Support and Public First (2023). 1970s Working Conditions in the 2020s: Modernising the Professional Lives of Teachers for the 21st Century. London: Education Support. Available online at: https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/resources/1970s-working-conditions-in-the-2020s/ (Accessed June 18, 2025).

Education Support and YouGov (2023). Teaching: the new reality: education support. Available online at: https://www.educationsupport.org.uk/media/cxkexon2/teaching-the-new-reality.pdf (Accessed June 18, 2025).