- 1Department of Health Promotion, Education, and Behavior & Office of Research, Arnold School of Public Health, Columbia, SC, United States

- 2Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics and Cancer Prevention and Control Program, Arnold School of Public Health, Columbia, SC, United States

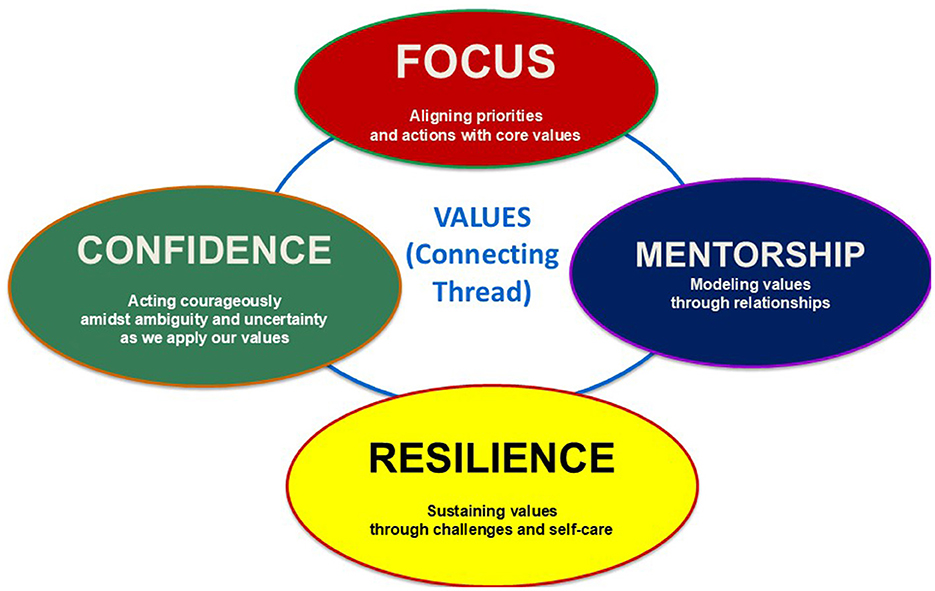

Leadership rarely follows a clear path. It often emerges from the choices we make, the people we encounter (and who encounter us), relationships we foster, and the values that guide us in our work. In this commentary, we draw on our experiences as researchers, educators, mentors, mentees, and administrators to describe four interconnected themes. We begin with the alignment of our work with personal and professional values, which serves as the anchor for the other three: engaging in mentorship as both mentors and mentees, maintaining resilience through self-care, and leading with confidence in times of uncertainty. These reflections illustrate that leadership is not the outcome of following a detailed “blueprint” or “manual of operations.” Rather than chasing the elusive goal of perfection, leadership should involve showing up grounded in our values and supported by networks of colleagues and communities. Although our experiences are based in public health, we work and thrive in contexts beyond the conventional boundaries of public health, thus the themes we describe have relevance across disciplines. We hope the description of these experiences encourages leaders at different stages to consider values that will strengthen their relationships and prioritize wellbeing, and to act with confidence and courage when facing uncertainty.

Introduction

Aspiring toward leadership in public health, as in many other professions, often follows a non-linear path. It evolves through the decisions we make, the people we meet, the relationships we nurture, and the values that guide us. It takes an effective leader or leadership team to set the tone and encourage a growth mindset. However, lasting success does not come from a top-down approach; it results from cultivating shared ownership (Johnson et al., 2022; Yelton et al., 2025).

We view leadership as a relational process that involves motivating and influencing people around us—and, in turn, being motivated by them to contribute actively and willingly toward the collective success of a group, community, or organization. Consistent with Brown's conceptualization, this involves an inclusive style grounded in empathy, connection, and courage. Above all, it requires having clarity about one's values in order to lead and serve others (Brown, 2015, 2018). Given the community-engaged nature of our work in public health, we also embrace and practice leadership with a focus on social responsibility and commitment to the partners with whom we collaborate and serve (Richardson et al., 2025).

When invited recently to speak with doctoral students about our academic journeys, we resisted the urge to offer “advice.” Advice suggests that there is a right way and a wrong way to do things, when it is really more of a messy, unpredictable and, hopefully, exhilarating ride. Instead, we shared stories, strategies, and lessons learned across our professional roles as researchers, teachers, administrators, and mentors. We considered these alongside our personal and family experiences that guide our actions and provide additional models for mentees (Friedman, 2022). We also made space for interactive discussion, recognizing that leadership is not done in isolation but in relationships with others (Friedman et al., 2024; Yelton et al., 2025). As we shared with the students, the rare time that one of us recalled giving advice was on the topic of toilet training and it's this: never buy a house with carpeted floors. It works! Another important bit of advice, which we didn't share with the class, is that one should always endeavor to live east of one's work if commuting during conventional business hours is involved! Beyond that, we've learned that advice in leadership, much like in parenting and choosing one's residence, is less about rules and more about learning, listening, and adapting to change—the only thing in this life that remains constant.

This perspectives piece, informed by our guest lecture and reflections on decades-long experiences in academia, highlights four themes that are critical for emerging leaders both within and beyond academia:

• Anchoring focus that aligns with personal and professional values,

• Seeking out and engaging in mentoring relationships throughout one's life—as both mentee and mentor,

• Prioritizing resilience through self-care, and

• Developing confidence to navigate and lead through uncertainty.

Although presented separately for clarity, these themes are deeply interwoven. Values provide the lens that weaves them together (Chang et al., 2021). Taken together, they form a way of leading that is both personal and shared, grounded in values that are not only our own but also those of mentors, colleagues, and communities who shape our perspectives and guide our actions.

Finding your focus by aligning with your values

In academia, we are constantly pulled in numerous directions. Faculty members juggle research, teaching, and service. Administrative responsibilities such as directing a center, chairing a department, or stepping into school- or university-wide leadership roles increase the number and variety of those directions and competing priorities exponentially—or at least it quickly feels that way. For doctoral students and early-career professionals, the pressure to define a clear path can be overwhelming (Rosal et al., 1997; Alhaj et al., 2024). The unspoken message often seems to be that you are never doing enough, that you must know exactly where you are headed, and that you must be moving at full speed straight toward some, often ill-defined, but laudable goal.

In our experience, focusing does not mean attempting to do everything or abruptly cutting things out. It means making intentional choices about what matters most in a given moment and ensuring those choices align with our core values. Values are the principles that ground us and influence how we lead, communicate, and make decisions with clarity and purpose even under pressure and amidst uncertainty (Chang et al., 2021; Brown, 2025). Continually reflecting on our values allows us to move from ideas to action and make decisions that are thoughtful and consistent with who we are (Schwartz, 2012).

Integrity, community, growth mindset, optimism, compassion, and collaboration are often the reasons why people enter public health in the first place. Yet those values frequently require revisiting. When we ask ourselves whether to spend an afternoon editing a manuscript, saying yes to a new opportunity to serve on a committee, or mentoring a student, the answer is clearer when framed through values. Does this choice reflect who we are and who we want to become? Does it benefit others? Does it expand or constrict our sphere of influence? Does it give us pleasure? Is it more important or satisfying than something else that we may have done on this particular afternoon? Do we first just need a mindful walk in nature to calmly reflect before moving forward?

Our earliest leadership experiences illustrate that values guide us long before we have formal leadership titles on our business cards. One of us ran a “library” out of our parents' home in high school, loaning out books to classmates, organizing raffles for the most books read, and building a small community of readers. It was a short-lived venture (the books stopped being returned!) but it planted a seed about creating something for others and bringing people together around a common interest. Another time, we ran a music and drama program at summer camp. On the surface, it was about teaching songs and staging Broadway plays. In reality, though, it was about organizing teams and building a sense of belonging and growing confidence in children. Other examples are more kinesthetic in nature. We started a club focused on building tree forts and flotilla in local ponds. The activities entailed enlisting local children to organize “supply chains.” This included finding discarded wood and other materials from building sites and going into the adjacent state forest to obtain natural materials, developing architectural plans, and assigning tasks. You could say those were our first leadership laboratories.

Our mentors, colleagues, and community partners bring their own values into our lives. When we consider their commitments alongside our own, we grow our understanding of what matters most and how our efforts fit into a larger context (Felder et al., 2015). A mentor who personifies generosity or justice may push us to prioritize collaboration over personal recognition and achievement (Friedman et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2022; Tenorio-Lopes, 2023). A community partner grounded in equity or trust may help us clarify why certain projects deserve our energy even if they do not yield immediate rewards such as publications or career promotions or may not even seem superficially germane to our mission (Hebert et al., 2009; Friedman et al., 2014; Troy et al., 2022).

This push and pull between academic metrics and relational leadership is real. CVs grow with publications, grants, and committee work. However, some of the most meaningful leadership qualities such as supporting a student through a personal crisis, brainstorming with a community partner experiencing funding cuts, or choosing rest over overwork, does not show up on resumes. Focus actually requires the courage to recognize that not everything of value can be measured and not all things that we can measure hold equal value.

Identifying and clarifying our values can involve guided reflection, journaling, or value-sorting exercises such as Brown's “Living Into Our Values Exercise” that link values with practicing behaviors (Brown, 2018, 2025). Another strategy is to ask trusted mentors or colleagues what values they observe us espousing in our daily work and interactions and discussing how these values align and/or conflict with our behaviors and actions.

Mentorship and collaboration: success is not a solo celebration

While values help shape our focus, mentorship ensures we have support along our path. Public health is inherently collaborative. No project, program, or grant proposal succeeds without a network of mentors, colleagues, and partners. When one of us interviewed for a faculty position nearly two decades ago, we were asked which people outside the department we wanted to meet. We named several. Those conversations were the beginning of lifelong mentoring relationships that grew into friendships and collaborations. These individuals were not just technical advisors. They modeled a way of being across both their academic and professional lives. They were curious, they had integrity, they valued collaborative work, and they took the time to have fun—both at work and outside of the office. Their mentorship was supportive and it showed us how to find our own way, set an example for others, and ultimately pay it forward.

Mentorship is not limited to faculty-student relationships. It can be peer-to-peer with our colleagues (Friedman et al., 2021). It can come from community partners who challenge us to align academic research with priorities that reflect lived realities (Yelton et al., 2025). It can come from professional associations or from those in practice settings. A mentor-mentee relationship does not always last forever or need to last forever. Importantly, even if it endures for a long time it will change as we evolve and exigencies arise. Some mentors guide us for a specific period or project; others remain a consistent presence for decades.

Our own professional relationship reflects this evolution. When we first met, one of us served as the other's formal mentor, offering guidance on how to navigate academia, grantsmanship, and work-life pressures. As careers moved forward, the relationship morphed into peer mentorship, characterized by co-leadership and greater shared decision making and idea generation. The mentorship never disappeared as we continue to seek input from each other and share encouragement on professional and personal matters. These changes emphasize that, over time, mentorship is guided by our shared values of Trust, Integrity, Collaboration, and a shared commitment to Growth, and less about titles and roles.

We encouraged the doctoral students in class to map their mentorship networks across three spheres: peer mentors, senior mentors, and community or practice mentors. This exercise helps reveal gaps. If all your mentors are senior mentors, perhaps it is time to reach outward laterally. If you have only peer mentors, perhaps it is time to seek those who can open new doors for you or model different stages of the career journey. The values that we may choose to describe our own existential reality may be different from those that we ascribe to our mentees. For example, we may aspire to exhibit Balance, Courage, Optimism, and Truth in our own life. In contrast, when reflecting on what we want for our mentees we might choose Humility, Recognition, Success, and Wisdom. Of course all these values are admirable. However, they may not apply equally to those people we mentor as they apply to ourselves. This makes perfect sense because these individuals are at a different stage of life and often need the recognition and success that we just take for granted.

Mentorship, then, becomes a way values are shared across generations. We often find ourselves guided by values we first observed in our mentors such as Humility, Service, Care, and Excellence. At the same time, our mentees may see in us examples of values they wish to cultivate in themselves—or maybe ones they do not want to prioritize at this time. This reciprocal exchange reminds us that leadership is not a solitary endeavor. Negative exemplars also can be formative. For example, observing someone senior misbehaving in a way that violates our own sense of decency or stated values can serve as a powerful motivator.

Mentorship can also play a key role in helping individuals navigate potential conflicts between their competing values. For example, mentors can model how to balance compassion with accountability or ambition and success with humility. Through regular open dialogue, mentors help mentees examine tensions between such values so they can make more intentional decisions. Modeling how we reconcile apparent conflicts can provide a strong values-based approach to mentoring. Such lessons impart much more than information, they provide a way to model the productive tension that can, and often does, arise in academia—and the world beyond our work.

Mentorship is not just about helping others get ahead. It helps prepare students and more junior colleagues to be mentors themselves. Some of our most important mentors have been community leaders who have reminded us that relationships outlast projects, and that the measure of success is not always an academic product but the trust built along the way. Their values of commitment to justice, trust, and teamwork inspire us to hold ourselves accountable not just to our funders and academic colleagues but to the people we serve (Yelton et al., 2025). Questions to consider are: Do our mentors reflect the kind of colleagues and leaders we aspire to be? Do they encourage us to uphold integrity, be collaborative, and seek growth opportunities? Are we offering those same values and opportunities to others who look to us for mentorship?

Resilience for self-care: it's not about being tough

Just as mentorship supports our growth through relationships, resilience helps sustain us on challenging journeys. Rejection is universal. In academia, rejection comes in the form of grant reviews, journal submissions, or job applications. In public health practice, rejection comes through proposals denied, partnerships that don't materialize or fizzle, or programs that fail to launch. Resilience is not the absence of rejection but the ability to recover, learn, and get back out there to collaborate, compete, and serve.

We remember our own papers as students that faced new reviewers with every revision cycle. In a similar vein, as early-career faculty members we vividly recall the time that the presentation of an innovative breakthrough took nine different journals over four years to finally be published and a grant application required five submissions before it was funded. These processes dragged on and on leaving us discouraged and exhausted. Those experiences now shape how we approach our journal editorial responsibilities, how we advise students and junior faculty to stick with innovative ideas, and find equanimity in taking the good and the bad to shape new ideas into grant proposals. Behind every academic product are human beings—both the authors and the reviewers. We strive to lead with empathy and fairness, remembering that our editorial and other decisions affect not just listings on resumes, but entire career trajectories and the richness of our lives, which intersect with and extend beyond our roles as academicians and administrators.

At the other extreme, we recall two papers from our cancer network group that were accepted immediately without revisions. Students witnessing that success assumed such outcomes were the norm. When the next student-led paper came back with a request for major revisions, the experience was jarring. That became a teaching moment for us to impart the importance of being resilient. Resilience is not about believing you will always succeed easily but about preparing oneself to navigate inevitable setbacks.

One of the most powerful illustrations of resilience came in a chance airport encounter. After one of us heard news of a rejected grant, we unexpectedly crossed paths while traveling. To a colleague overhearing our conversation, she thought it sounded like we were talking about a serious personal or familial illness or bereavement. In many ways, we were. Rejection, like grief, may require mourning. By naming the disappointment, by allowing ourselves to feel it, we gave one another permission to cope and then move on. The next day, emails were flying again from different airplanes headed overseas. The disappointment had softened—in part because of the supportive relationship we had cultivated in the years before this setback. Drawing on our previous experiences in working together that were based on our shared values of empathy, caring, compassion, hope, and commitment, our relationship was strengthened and deepened by what, on the surface, would have been seen as a purely negative experience.

We have also learned hard lessons about boundaries. Once, while experiencing a medical emergency, one of us continued to work on a manuscript to ensure a colleague had the chance to be first author. The effort was unacknowledged and the work dragged on. That experience underscored that resilience cannot come at the expense of our own health or the health of our families. Boundaries are not selfish. They are acts of self-care, ensuring that we have the energy to continue leading for the long term. Resilience is not just about being tough, a perspective that we shared with the students. It is the combination of being vulnerable, recovering, taking the time for self-care, and showing courage. It is the recognition that failure happens and that what matters most is how quickly we get over the hump, not only for ourselves but for those around us—both at home and at work.

Resilience encourages us to ask: Are we giving ourselves time to sit with disappointment before moving on? Are we modeling compassion for ourselves when we experience setbacks? Are we setting healthy boundaries so that we also prioritize our self-care?

Leading through uncertainty: confidence without certainty

Resilience gives us strength and continued momentum while confidence helps us lead while navigating uncertainty. Some uncertainties are personal, like the grief of losing a colleague. Others are global like the sudden upheaval from a worldwide pandemic. In these situations, leadership is less about having the “right” answers and more about projecting care and confidence and creating conditions for others to succeed despite the unknowns.

We recall the difficulty of leading when our dear colleague and friend passed away. There was no handbook for what to do next. The day after her death, walking into the office and facing the team felt daunting. Yet leadership required showing up, vulnerable and in tears, and creating space for others to grieve, remember, and eventually move forward. Leading during the COVID-19 pandemic carried similar weight. Decisions had to be made with incomplete information. Leadership in that context was more about transparency—listening deeply, keeping in contact with people so they knew we were there for them, and making decisions with courage, knowing these decisions would need to be revised within the week or the month. And when it came time to decide whether to apply for leadership roles, the challenges have been personal. The choice required balancing ambition with fear of deserting family, projecting confidence with humility, and making decisions that reflected not just professional aspirations but also values and commitment to the people we serve and who depend on us in many ways.

Leadership in uncertainty involves creating some balance for us and others. Values of empathy, collaboration, patience, and perseverance are essential in both good and, especially, bad times. Having close friends and confidants is essential for conserving one's energy and avoiding making mistakes that have implications far into the future. This applies to good times as well as bad. We are both optimists but we also realize that the one flaw of the optimist is to downplay risk. So, we also need to be willing to provide a measure of restraint and good counsel when the other is euphoric about a recent success or ebullient about a new opportunity that just seems too good to believe. This is just as important as buoying a colleague who has recently experienced rejection or loss.

Leadership under uncertainty raises these questions: Are we leading in a manner that reflects empathy, humility, and courage? Are we balancing optimism with reality? Are we helping to create conditions under which others feel supported to thrive even if the path forward is unclear? Do our leadership decisions during uncertain times align with our values?

Linking the themes

Although we have presented focus, mentorship, resilience, and confidence as distinct themes, they are interdependent. Values provide the thread that ties them together as presented in Figure 1. For example, kindness, empathy, courage, humility, integrity, and collaboration are all essential ingredients in launching a successful career and, even more importantly, a satisfying and fulfilling life. Focus helps us decide what matters most and those decisions are sharpened when tested against the values of our mentors and communities. Equanimity in determining focus provides the necessary balance to keep us from falling in the first place and to make it easier to get up when we do fall. Mentors provide advice and support. They also model how values can be lived out in practice. Resilience allows us to recover from setbacks, sustained by norms that emphasize rest, care, and perseverance. Confidently leading through uncertainty requires drawing on both our own values and those we have seen modeled, weaving them into practices that empower others. Taken together, these themes remind us that leadership is relational and driven by values. The choices we make reflect the foundation we inherit from others and principles we share with those who will follow us. Professional development in these areas should not be siloed within the walls of academia. Some of the most important lessons we've learned about teamwork and team science have come from coaching offered by leaders in industry, nonprofits, and communities. By remaining open to learning across disciplines, we expand our ability to grow and lead creatively and with the flexibility to adapt.

Why we ended with “when to say yes or no?”

At the close of the lecture, we asked students to reflect on a deceptively simple question: How do you know when to say yes and when to say no? We saved this question for last because it is where all four themes intersect. Saying yes or no requires aligning our choices with our values and our short-term and long-term goals. It requires mentorship, seeking input from those whose wisdom and values can help guide us. It requires resilience and recognizing that each yes or no could involve conflict, regret, rejection, and needing to recover when things may not go as planned. A well-placed “no” can save us countless hours of agony, resentment, and regret. Likewise, a well-placed “yes” can lead us into a whole new realm of joy and satisfaction. By contrast, inappropriately saying “no” can cut us off from opportunity and saying “yes” inappropriately can waste time and poison relationships. We reminded the students that whatever decision they make will require acting with confidence in uncertainty and accepting that, though they may never have perfect information, they still must make choices with courage and care. To not make a decision when one is required is to shirk responsibility in a way that violates our values of caring, empathy, generosity, and grace.

The question of when to say yes or no is a values-based question and not a technical one. Boundaries protect our wellbeing and remind us of our important commitments. Saying no is not necessarily closing a door on an opportunity. It is choosing which doors we can walk through now and, perhaps, which doors open at a future time. We asked this question at the end of the lecture because it cannot be answered in isolation. We have noticed, with frustration, that this question is often discussed out of context or in a flippant manner that can undermine its importance. We encourage students to consider it after reflecting on values, mentorship, resilience, and confidence amidst uncertainty. Only then can we really begin to make effective decisions about what to take on and what to decline. Knowing when and how to say no can become an act of leadership in itself.

We want our students to know that life and work after graduation will look different for each of them. What should be constant is the need to live out our values, nurture supportive relationships, and engage in practices that ensure our wellbeing. We wish we had shouted this from the rooftops earlier on in our careers—but, alas, we know that proclamations of that sort are rarely effective. So, moving forward. we are determined to keep working on role modeling as best we can. Values-based leadership focused on mentorship, resilience, and confidence imbues everything we do—with relevance extending beyond public health—to other disciplines and professions and into all of life's complexity. By modeling these principles, we can help prepare emerging leaders to carefully define and articulate their values and apply them to all aspects of their lives.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DF: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JH: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by an Academic Leadership Career Award (K07AG088128) to DF from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging. JH was supported by grant P20GM155896 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of our mentors and mentees whose values and experiences have inspired our work and enriched our lives.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

Alhaj, O. A., Elsahoryi, N. A., Fekih-Romdhane, F., Wishah, M., Sweidan, D. H., Husain, W., et al. (2024). Prevalence of emotional burnout among dietitians and nutritionists: a systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-regression, and a call for action. BMC Psychol. 12:775. doi: 10.1186/s40359-024-02290-8

Brown, B. (2015). Daring Greatly: How the Courage to Be Vulnerable Transforms the Way We Live, Love, Parent, and Lead. New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to Lead: Brave Work. Tough Conversations. Whole Hearts. New York, NY: Random House.

Brown, B. (2025). Living in Our Values Exercise. Available online at: https://brenebrown.com/resources/living-into-our-values-3/ (accessed October 31, 2025).

Chang, S. M., Budhwar, P., and Crawshaw, J. (2021). The emergence of value-based leadership behavior at the frontline of management: a role theory perspective and future research agenda. Front. Psychol. 12:635106. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635106

Felder, T. M., Braun, K. L., Brandt, H. M., Khan, S., Tanjasiri, S., Friedman, D. B., et al. (2015). Mentoring and training of cancer-related health disparities researchers committed to community-based participatory research. Progr. Commun. Health Partnersh. 9(Suppl. 0), 97–108. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0020

Friedman, D. B. (2022). In the words of my mother: “I'm fighting hard for me but mostly for you”. J. Cancer Educ. 37, 1261–1263. doi: 10.1007/s13187-022-02175-7

Friedman, D. B., Donelle, L., Levkoff, S. E., Neils-Strunjas, J., Porter, D. E., Tanner, A., et al. (2024). Mentoring in developing, engaging with, and sustaining research teams that aligns with health and risk communication principles: apples and oranges or apples and apples? Ment. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 32:2299383. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2023.2299383

Friedman, D. B., Owens, O. L., Jackson, D. D., Johnson, K. M., Gansauer, L., Dickey, J., et al. (2014). An evaluation of a community-academic-clinical partnership to reduce prostate cancer disparities in the South. J. Cancer Educ. 29, 80–85. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0550-5

Friedman, D. B., Yelton, B., Corwin, S. J., Hardin, J. W., Ingram, L. A., Torres-McGehee, T. M., et al. (2021). Value of peer mentorship for equity in higher education leadership: a school of public health focus with implications for all academic administrators. Ment. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 29, 500–521. doi: 10.1080/13611267.2021.1986795

Hebert, J. R., Brandt, H. M., Armstead, C. A., Adams, S. A., and Steck, S. E. (2009). Interdisciplinary, translational, and community-based participatory research: finding a common language to improve cancer research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 18, 1213–1217. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1166

Johnson, C. L., Friedman, D. B., Ingram, L. A., Ford, M. E., McCrary-Quarles, A., Dye, C. J., et al. (2022). Reflections on mentorship from scientists and mentors in an Alzheimer's disease focused research training program. J. Appl. Gerontol. 41, 2307–2315. doi: 10.1177/07334648221109514

Richardson, S. D., Parker, M., and Bon-Ami, L. (2025). Leadership education for social responsibility. Front. Educ. 10:1580097. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1580097

Rosal, M. C., Ockene, I. S., Ockene, J. K., Barrett, S. V., Ma, Y., and Hebert, J. R. (1997). A longitudinal study of students' depression at one medical school. Acad. Med. 72, 542–546. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199706000-00022

Schwartz, S. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2:1116. doi: 10.9707/2307-0919.1116

Tenorio-Lopes (2023). Mentor-mentee relationships in academia: insights toward a fulfilling career. Front. Educ. 8:1198094. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1198094

Troy, C., Brunson, A., Goldsmith, A., Noblet, S., Steck, S. E., Hebert, J. R., et al. (2022). Implementing community-based prostate cancer education in rural South Carolina: a collaborative approach through a statewide cancer alliance. J. Cancer Educ. 37, 163–168. doi: 10.1007/s13187-020-01800-7

Keywords: public health leadership, peer mentorship, growth mindset, self-care, resilience

Citation: Friedman DB and Hebert JR (2025) Value-guided mentoring produces great leaders. Front. Educ. 10:1715688. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1715688

Received: 03 October 2025; Revised: 15 November 2025;

Accepted: 17 November 2025; Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Casey Cobb, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Roger Fillingim, University of Florida, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Friedman and Hebert. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Daniela B. Friedman, ZGJmcmllZG1hbkBzYy5lZHU=

†ORCID: Daniela B. Friedman orcid.org/0000-0002-9359-093X;

James R. Hebert orcid.org/0000-0002-0677-2672;

Daniela B. Friedman

Daniela B. Friedman James R. Hebert2†

James R. Hebert2†