- 1Department of Software Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Ankara University, Ankara, Türkiye

- 2Department of Computer Education and Instructional Technology, Faculty of Education, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Türkiye

Social media has become a pervasive element of higher education; however, the experiences of faculty and students with its educational use remain underexplored. This study employed a transcendental phenomenological design to investigate the lived experiences of three faculty members and 12 students who used Facebook as a learning tool. Data were collected through in-depth, semi-structured interviews and analyzed using Moustakas’ transcendental phenomenological method, which allowed for the identification of the essence of participants’ experiences while minimizing researcher bias. Findings indicate that Facebook facilitates communication, supports collaborative learning, and provides flexible access to educational resources, enhancing academic engagement. Participants reported benefits, including immediate information sharing and interactive peer support. However, challenges were also noted, including privacy concerns, potential distractions, and the informal nature of interactions, which may affect structured learning. These findings suggest that while Facebook can supplement formal education meaningfully, it should not replace traditional instruction. The study offers practical guidance on balancing engagement, privacy, and curriculum integration, providing educators with insight into thoughtfully leveraging social media in higher education. By presenting both benefits and limitations, this research contributes to a nuanced understanding of Facebook’s educational role and informs strategies for its practical use.

Introduction

In recent decades, social media has emerged as a revolutionary force reshaping communication, collaboration, and information dissemination across multiple disciplines, including education. Platforms such as Instagram and Facebook have become integral to everyday digital interaction, shaping how individuals connect, learn, and express themselves. Although social media platforms were initially designed for social networking, they have evolved into a multifaceted digital ecosystem offering functionalities such as group creation, real-time messaging, content curation, and asynchronous discussions. These features have sparked considerable interest among educators exploring creative and innovative approaches to enhance student engagement, promote collaborative learning, and extend educational experiences beyond traditional classroom boundaries (Qassrawi and Karasneh, 2023; Woodford et al., 2022; Salas-Rueda, 2021; Liljekvist et al., 2020).

Despite the increasing prevalence of social media in educational contexts, most empirical research has predominantly employed quantitative methodologies, focusing on variables such as academic performance, user behavior, and platform engagement (Dule et al., 2023; Hoi and Hang, 2021a; Fu and Li, 2020; Low and Wong, 2021). While these studies have produced valuable insights into measurable outcomes, they often overlook the complex experiential and emotional realities that accompany social media use in academic life. For instance, how educators and students feel, reflect, and construct meaning through these digital interactions remains largely unexplored. Prior research has tended to treat social media as a tool rather than a lived environment that shapes affective, cognitive, and social dimensions of learning. Notably, there is a scarcity of qualitative research that dives into the lived experiences of faculty members and students, who represent key stakeholders in implementing technology-enhanced pedagogical practices (Dennen et al., 2020). Addressing this underexplored dimension is essential to understand not only how social media supports learning but also how it affects users’ sense of connection, motivation, and professional identity within higher education.

This study addresses this gap by employing a phenomenological research design to investigate how Facebook is perceived and experienced by educators and students in higher education. Specifically, the research examines how faculty members and students manage the affordances and constraints of Facebook in their academic work, the pedagogical rationales underlying their use of the platform, and the socio-technical dynamics that influence their engagement. In doing so, this research aligns with recommendations in the field of educational technology for more contextualized, interpretive, and experience-driven approaches to understanding digital learning environments (Kumi-Yeboah et al., 2020; Stickler and Hampel, 2019).

The study aims to provide practical insights into how Facebook can be meaningfully integrated into higher education. To achieve these aims, the study is guided by the following research questions:

1) What are faculty members’ lived experiences with the educational use of Facebook?

2) What are students’ lived experiences with the educational use of Facebook?

Literature review

Social media in educational contexts

Educational research has extensively explored the pedagogical integration of social media platforms, with studies highlighting their potential to support active learning, peer collaboration, learner autonomy, and improved academic performance (Astleitner and Schlick, 2024; Qureshi et al., 2021; Ansari and Khan, 2020). Social media tools provide learners ubiquitous access to educational content, facilitate communication across time and space boundaries, and support participatory pedagogies emphasizing learner autonomy and interaction (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022; Hamadi et al., 2021; Poshka, 2020).

Social media platforms have attracted interest for their capacity to enhance both formal and informal learning. Previous research has reported the utilization of Facebook groups to sustain academic discussions, collaboratively develop knowledge artifacts, and foster communities of inquiry (Duha et al., 2022; Vázquez-Cano and Díez-Arcón, 2021; Liljekvist et al., 2020). These online environments enable learners to exchange feedback, share relevant resources, and engage in reflective conversation, thereby reinforcing constructivist pedagogical approaches that view learning as a socially situated process (Alismaiel et al., 2022; Virtanen et al., 2022; Timonen and Ruokamo, 2021).

However, much of this body of work remains descriptive, focusing primarily on reported benefits rather than critically comparing how different methodological or theoretical approaches conceptualize the role of social media in learning. Recent meta-analyses (Greenhow and Askari, 2015; Manca, 2019) suggest that while quantitative studies often emphasize engagement and performance metrics, qualitative or phenomenological research foregrounds emotional, relational, and contextual dimensions that remain underexplored. This divergence underscores a conceptual gap that this study directly addresses.

Affordances and constraints of using social media in education

Numerous studies have identified unique affordances of using social media for educational purposes, including enhanced teacher-student communication, increased student engagement, and the development of supportive learning communities (Hoi, 2021; Ansari and Khan, 2020; Muls et al., 2019). For instance, Chen and Ramzan (2024) found that social media posts can boost learners’ motivation and performance in learning English as a second language. Similarly, studies show that class groups created on Facebook promote social bonding and learning among high school students, fostering a sense of solidarity and unity among them (Muls et al., 2019). Furthermore, the interactive nature of social media allows students to collaborate more effectively, exchange ideas, and receive immediate feedback, further enhancing the overall learning experience (Ali, 2023; Hoi, 2021).

However, integrating social media into educational environments also introduces significant challenges. Informal nature often these platforms blur the distinctions between personal and academic spaces, raising concerns about professionalism, data privacy, and the ethical use of resources (Brown, 2020; Rukavina et al., 2021). Furthermore, potential distractions and multitasking on social media have been associated with reduced academic performance, especially when their use is not integrated into well-structured educational frameworks (Hamadi et al., 2021; Masood et al., 2020).

Researchers have also noted that students and educators may exhibit resistance to use commercial social media platforms in academic contexts due to concerns of surveillance, exposure, and identity conflict (Al-Qaysi et al., 2023; Balushi et al., 2022; Dzara et al., 2021; Haşiloğlu et al., 2020). These fears highlight the necessity of intentional instructional design, clear communication of expectations, and the development of digital literacy competencies to support meaningful and ethical social media use in education.

In sum, these studies reveal a fragmented landscape where positive affordances and negative constraints are often treated separately. A more integrative synthesis, such as the one pursued in this study, helps reveal how these tensions manifest in the lived experiences of educators and students navigating the pedagogical use of social media.

Pedagogical design and implementation

Researchers suggest using social media as a supplementary tool that aligns with constructivist and connectivist learning concepts to enhance its educational potential (Ali, 2023; Hoi and Hang, 2021a, 2021b; Todorovic et al., 2020). For example, instructors may use closed Facebook groups to facilitate asynchronous discussions, crowdsource ideas, and share multimedia content relevant to course objectives (Woodford et al., 2022; Todorovic et al., 2020; Chen and Bryer, 2012). When combined with explicit guidelines and support structures, such practices can foster engagement and inclusivity while reducing risks associated with unregulated use.

However, existing studies primarily reflect general usage trends and self-reported results, lacking an in-depth and comprehensive understanding of how faculty and students experience these tools in their daily academic activities. By adopting a phenomenological lens, this research advances the field by integrating fragmented insights into a coherent framework focused on lived experience and meaning-making in higher education.

Theoretical framework

Three theoretical lenses guide this study: sociocultural theory, constructivism, and the Community of Inquiry (CoI) model. Together, they offer a foundation for understanding the pedagogical dynamics of Facebook in higher education.

Sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1980) claims that learning is primarily social and mediated by cultural instruments. These platforms serve as a mediational tool facilitating learners’ co-constructing knowledge through interaction, negotiation, and collaborative engagement. These interactions are shaped by the sociocultural contexts in which learning occurs, making it essential to consider how institutional norms, disciplinary practices, and digital literacies influence the utilization of technology.

Constructivist theory (Piaget, 1971) supports this perspective and emphasizes learners’ active involvement in meaning-making processes. With its support for learner-generated content, peer feedback, and self-directed exploration, social media aligns with constructivist pedagogies by allowing learners to take initiative in knowledge construction, engage with multiple perspectives, and connect learning to real-world contexts.

Finally, the CoI framework (Garrison et al., 1999) offers a model for understanding online learning environments through the interaction of cognitive, social, and teaching presence. Social media platforms provide opportunities to support all three presences: cognitive presence through discussion and inquiry, social presence through relationship-building and identity expression, and teaching presence through instructor facilitation and guidance. However, the informal design of these platforms requires precise integration to maintain a balanced and productive learning community.

By integrating these theoretical perspectives, this study aims to explore how faculty and students experience and interpret the educational use of Facebook. The findings are expected to contribute to ongoing debates in educational technology by highlighting the contextual, pedagogical, and experiential factors that shape digital learning practices in higher education.

Methodology

Research design

This study adopts a transcendental phenomenological framework to examine the lived experiences of faculty members and students in utilizing Facebook as a social media platform for educational purposes. Although a variety of platforms (e.g., Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn) were available during the study period, Facebook was chosen as the focal context because it served as the one of the most commonly used and pedagogically structured environment among participants for group discussions, content sharing, and course-related communication. To minimize personal bias and enhance objectivity, the researcher practiced epoche, or bracketing, throughout the study by maintaining a reflexive journal documenting personal assumptions and reflections (Husserl, 1970).

The choice of phenomenology aligns with the study’s aim to provide a nuanced exploration of participants’ interactions with social media in educational settings. By prioritizing their lived experiences, this approach seeks to uncover the fundamental meanings and structures that shape the use of Facebook as a learning platform. This study is particularly significant as it addresses gaps in the literature, offering insights into how social media is used across diverse academic disciplines and educational levels, an area that previous studies (e.g., Dabbagh and Kitsantas, 2011; Hew, 2011) have only partially explored. Additionally, this method facilitates a nuanced understanding of the interplay between technological affordances and pedagogical practices, thereby contributing to the growing body of literature on the role of social media in education.

Participants and sampling

This study employed criterion sampling, a purposeful sampling strategy in qualitative research, to recruit participants who met predefined criteria aligned with the research purpose (Patton, 2002). Specifically, participants were required to have prior experience using Facebook for educational purposes, such as facilitating communication, sharing academic content, or engaging in learning-related interactions. This criterion ensured that participants could provide rich, relevant, and reflective insights into the phenomenon under investigation.

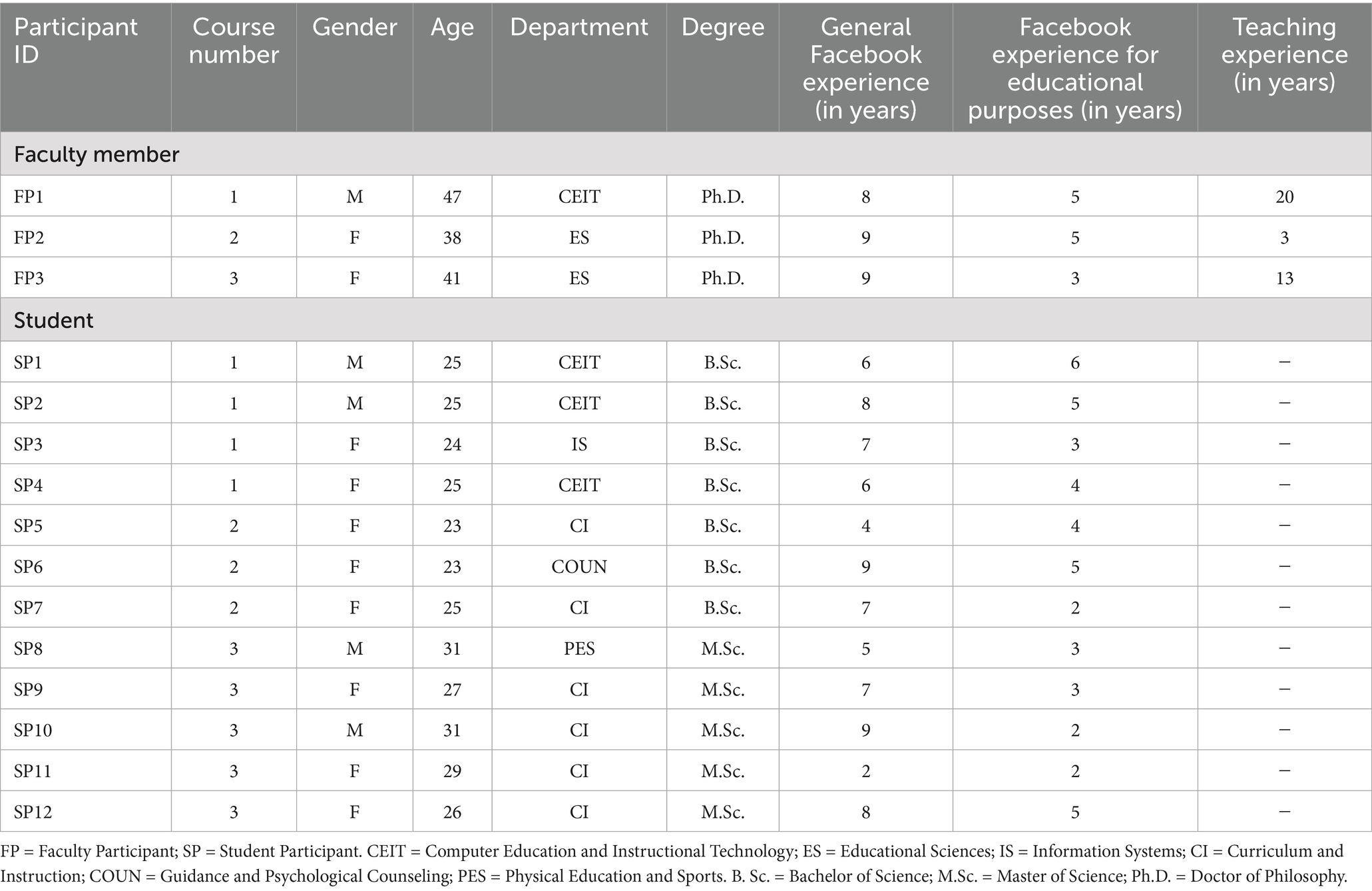

The final sample consisted of three faculty members and 12 students from a public university in Turkey. Faculty members were selected from various academic fields, including Computer Education and Instructional Technology, Educational Sciences, and Social Sciences. This disciplinary diversity allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of how social media is perceived and utilized for educational purposes in higher education settings.

The student participants were enrolled in either bachelor’s or master’s programs across a range of departments, including Curriculum and Instruction, Guidance and Psychological Counseling, Information Systems, and Physical Education and Sports. Their inclusion broadened the scope of perspectives, particularly in terms of academic level and field-specific expectations concerning digital educational tools.

The sample size of 15 participants was deemed sufficient to reach data saturation, which is considered a standard indicator of adequacy in phenomenological research (Creswell and Poth, 2018). Saturation was observed when recurring themes and patterns began to emerge consistently across interviews, indicating that additional data were unlikely to yield novel insights. While phenomenological studies do not aim for statistical generalization, the findings are contextually situated within the Turkish higher education environment, and their transferability should be considered in relation to similar institutional settings.

Table 1 provides detailed demographic and experiential information about the participants, including age, gender, academic discipline, level of education, general social media usage, use of social media for educational purposes, and teaching experience.

Data collection

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Middle East Technical University, Türkiye. All participants provided informed consent, and participation was voluntary. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured, and data were securely stored with identifying information removed during transcription and analysis. Data were collected through a series of in-depth, semi-structured interviews with faculty members and students. The interviews were designed to elicit detailed descriptions of the participants’ experiences with Facebook-mediated educational practices. The interview questions focused on the participants’ perceptions of Facebook as a learning tool, the challenges they encountered, and how Facebook impacted their teaching or learning practices. The open-ended and flexible questions allowed participants to share their unique experiences. Follow-up questions were used to probe deeper into emerging themes or issues that participants had not initially addressed. A sample set of interview questions is provided in Appendix A to enhance methodological transparency.

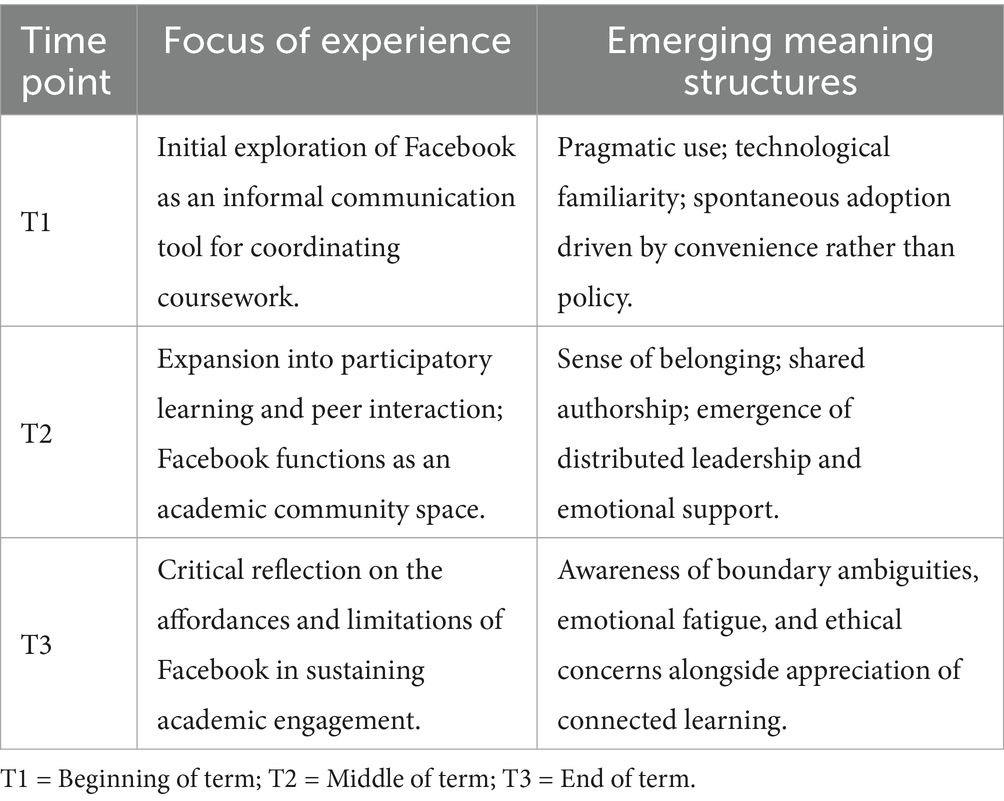

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the evolving experiences of participants, the interviews were conducted at three different points throughout the academic term: at the beginning, middle, and end of the term. This longitudinal approach enabled a deeper exploration of how the use of Facebook as an educational tool evolves over time and in response to various stages of the academic process. Each interview lasted approximately 60–90 min and was conducted in person. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. In addition to the interviews, field notes were taken to capture nonverbal cues and contextual information, further enriching the analysis. Table 2 summarizes the longitudinal progression of participants’ engagement with Facebook across three data collection points, reflecting how their practices evolved from pragmatic use toward participatory engagement and critical reflection.

Table 2. Summary of longitudinal evolution in participants’ experiences with Facebook for educational purposes.

Data analysis

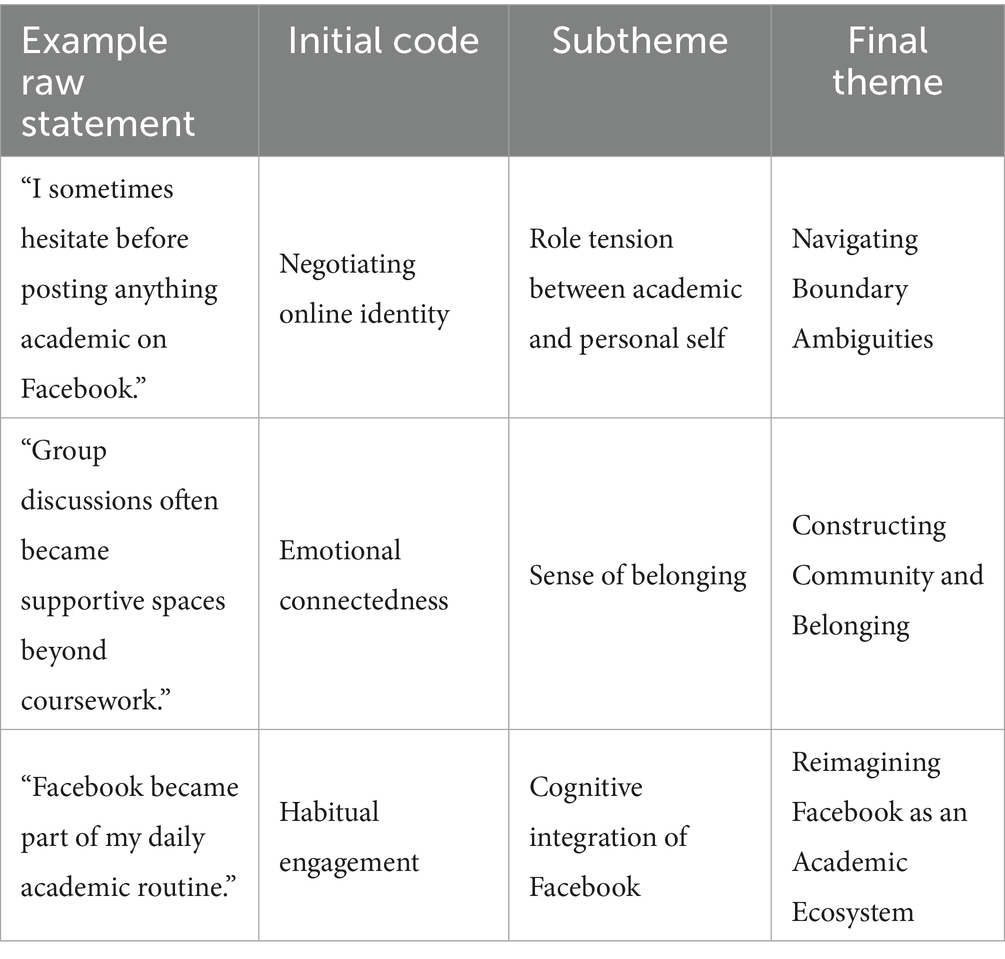

Data were analyzed using Moustakas (1994) transcendental phenomenological analysis framework, which is designed to uncover the essence of participants’ lived experiences through a structured, multi-step process. The first step, epoche, involved the researcher intentionally bracketing personal preconceptions and biases regarding the use of Facebook in educational settings. This process of bracketing, integral to transcendental phenomenology, allowed the researcher to approach the phenomenon with a fresh, unbiased perspective and focus solely on the meanings conveyed by the participants (Moustakas, 1994). To ensure ongoing reflexivity throughout the study, the researcher maintained a detailed reflexive journal, documenting emerging assumptions, analytical decisions, and personal reflections.

Following epoche, the researcher engaged in horizontalization, a process in which significant statements from the participants’ descriptions were identified and listed. These statements were then treated as having equal value and analyzed to form meaning units. The analysis was conducted using MAXQDA 2022 qualitative analysis software (VERBI Software, 2022), which facilitated systematic organization of the data, coding, and theme development. Initial codes were inductively generated from the participants’ verbatim statements and then grouped into subthemes based on conceptual similarity. The resulting meaning units were organized into broader thematic clusters that reflected common structures and patterns across the participants’ experiences (Moustakas, 1994). To enhance analytical transparency and rigor, Table 3 presents a sample excerpt from the coding structure used in MAXQDA, illustrating how raw statements were progressively clustered into subthemes and final themes.

At this stage, imaginative variation was applied to move beyond the surface description of experiences toward the identification of the underlying structures of consciousness. Through iterative reflection, the researcher explored how participants’ experiences of using Facebook were intentionally constituted — that is, how meaning arose through their perceptions, interactions, and reinterpretations of digital space. This process enabled the articulation of both the textural (what was experienced) and structural (how it was experienced) dimensions of the phenomenon.

In the final stage of analysis, the researcher synthesized the emergent themes into a textural description and a structural description. During synthesis, representative quotations supporting each theme were identified and used in the Results section to illustrate how these abstract meanings were grounded in participants’ lived experiences. Finally, these descriptions were integrated into a composite synthesis of essence — a statement capturing the invariant meaning that transcends individual differences and reflects the shared experiential core of participants’ engagement with Facebook as a pedagogical space. This reflective and iterative process ensured phenomenological integrity by maintaining fidelity to participants’ lived meanings and grounding all themes in empirical evidence (Creswell and Poth, 2018).

Trustworthiness and rigor

To ensure the trustworthiness and rigor of this study, several strategies were employed, reflecting both qualitative research best practices and the principles of phenomenology. As Lincoln and Guba (1985) argue, trustworthiness in qualitative research is crucial to demonstrate that the findings are both credible and grounded in the data. One of the primary methods used in this study was member checking, which allowed participants to verify the accuracy of the interview transcripts and the researcher’s interpretations. Participants were invited to review their transcripts and provide feedback or corrections, ensuring that their perspectives were accurately represented and enhancing the credibility of the findings (Shank, 2002).

In addition to member checking, the researcher engaged in peer debriefing to further strengthen the study’s trustworthiness. This process involved structured discussions with colleagues familiar with qualitative research methods, providing an opportunity for critical reflection on the findings and the analytical process. Peer debriefing helped identify potential biases and ensured that the study’s analysis was credible and well-supported by the data.

To enhance the rigor of the study, the researcher maintained a reflexive journal throughout the research process. This journal documented personal reflections, potential biases, and assumptions that emerged during data collection and analysis. By engaging in reflexivity, the researcher sought to remain aware of how individual perspectives might influence the study and consciously tried to mitigate these biases (Creswell and Poth, 2018). The journal also allowed the researcher to track changes in data interpretation throughout the study, providing a more nuanced understanding of the participants’ evolving experiences.

Furthermore, an audit trail was maintained to document each step of the data analysis process, ensuring transparency and facilitating the replication of the study. This audit trail included detailed records of the coding process, thematic development, and decisions made during the analysis, reinforcing the study’s rigor and accountability (Moustakas, 1994).

By employing these strategies – member checking, peer debriefing, reflexive journaling, and maintaining an audit trail – the study adhered to trustworthiness and rigor, ensuring that the findings were credible and rooted in participants’ authentic experiences.

Results

This section presents the study’s findings through the lens of transcendental phenomenology, grounded in the lived experiences of faculty members and students who engaged with Facebook for educational purposes. Utilizing Moustakas (1994) structured analytical approach, including epoche, horizontalization, clustering of meaning units, and synthesis of textural and structural descriptions, the analysis revealed a nuanced and layered understanding of how Facebook was experienced, reimagined, and negotiated as a pedagogical space in higher education.

Through rigorous thematic coding and interpretation, three comprehensive themes were identified: (1) Reimagining Facebook as an Academic Ecosystem, (2) Constructing Community and Belonging through Participatory Culture, and (3) Navigating Boundary Ambiguities and Emotional Labor in Hybrid Learning Spaces. These themes reflect both shared perceptions across participants and deeper intentional structures through which participants constituted meaning within their digital academic worlds.

Reimagining Facebook as an academic ecosystem

This theme illuminates how participants’ consciousness of Facebook shifted from perceiving it as a social medium to constituting it as an academic “lifeworld.” Participants described how Facebook originally used for informal interaction was gradually transformed into an academic infrastructure through user-led experimentation and adaptation. This transformation involved both behavioral and perceptual reorientation, revealing the intentional process through which a familiar digital environment became imbued with academic meaning. Several participants noted that their prior experiences with Facebook and Learning Management Systems (LMSs) enabled them to repurpose new platforms with minimal friction. As one faculty member reflected:

“Before I ever used Facebook for anything academic, I already had years of experience with MSN, Skype, and Moodle. The structure was familiar—groups, chats, file sharing. It didn’t feel like I was learning something new.” (FP3)

From a textural standpoint, participants’ adoption of Facebook stemmed from everyday pragmatic needs; structurally, it reflected an intentional reinterpretation of technological affordances as pedagogical possibilities. Particularly in situations where official LMSs were perceived as rigid or cumbersome, Facebook offered a responsive and integrated alternative. What began as informal use sharing - reminders or clarifications - gradually deepened into dialogic engagement, resource sharing, and assignment coordination.

“Initially, I used Facebook for the same reason everyone else did –social stuff, catching up with friends. But then, without realizing it, it became the main tool I used to manage class updates.” (SP6)

As Facebook became routine, participants used it to share academic content, post questions, conduct group work, and interact with faculty asynchronously. One student likened checking the Facebook group to a daily ritual:

“I check the Facebook group as part of my morning routine – just like checking email or my calendar.” (SP1)

In essence, participants’ experience demonstrates a process of domestication not only of technology but of meaning—Facebook became part of their academic being-in-the-world, where communication, identity, and learning intertwined in pre-reflective routines.

Constructing community and belonging through participatory culture

This theme reveals how participants’ sense of belonging and community were constituted through affective and intersubjective engagement within the Facebook environment. Facebook became a participatory academic community where emotional connection, collaboration, and peer learning flourished. This transformation was not merely organizational but experiential — students’ agency reflected a shift in intentionality from compliance to co-authorship of the learning space.

“We asked our professor to start a Facebook group because everyone was already checking Facebook. It just made sense to use one platform instead of switching between e-mail, WhatsApp, and the official LMS.” (SP9)

Students’ earlier initiatives to establish and administer Facebook groups demonstrated their ability to influence the cultural and emotional aspects of their learning environments. However, it is important to note that, for the courses examined in this study, faculty members had already created the Facebook groups for pedagogical purposes rather than students initiating them.

Faculty members reported that the Facebook setting allowed for more authentic interactions and provided more profound insight into student thinking. The informality of Facebook fostered a sense of mutual presence and encouraged contributions from students who typically remained silent in more formal settings. These accounts indicate that authenticity and presence were not only outcomes but phenomenological conditions of participation — moments in which the self was experienced as both visible and connected within a shared lifeworld:

“What surprised me was how much more I got to know my students when we were interacting on Facebook. It wasn’t just about the course; it was about building relationships and community within the Facebook group.” (FP1)

Students described how the group culture shifted from instructor-led discussions to peer-driven dialogue. Facebook enabled them to initiate threads, share links, and engage in interdisciplinary knowledge exchange, without needing explicit permission or centralized control.

“We didn’t wait for someone to post anymore. We started the discussions ourselves and invited others to join. It became a habit, like checking the Facebook group with our morning coffee.” (SP8)

A form of distributed leadership emerged, where students played active roles in shaping the learning process. Knowledge was not merely transmitted by faculty but co-constructed through interaction, reflection, and collective sense-making:

“Someone would post a relevant TED Talk or a news article, and the conversation would take off from there. We weren’t just learning from the professor—we were learning from each other in the Facebook group.” (SP10)

Faculty participants described a shift in pedagogical positions—from content delivery to facilitation and synthesis – highlighting their evolving role in this decentralized environment:

“My role changed. Instead of managing every post, I found myself curating and redirecting the energy that students brought to the Facebook group.” (FP2)

Importantly, the Facebook groups functioned as emotional support and belonging spaces, particularly during stressful academic periods. Participants recalled moments when the Facebook group served not only as an educational hub but as a source of empathy and encouragement.

Structurally, this theme captures how participants’ consciousness of community emerged through mutual recognition, emotional resonance, and habitual engagement — the lived essence of participatory belonging in digital academia.

Navigating boundary ambiguities and emotional labor in hybrid learning spaces

Although Facebook facilitated access and community-building, it simultaneously blurred personal and academic boundaries, raising ethical and professional concerns. This theme explores how participants experienced the tension between accessibility and exposure — a lived ambiguity between the personal and the professional self. Faculty members expressed concern about the ambiguity of their roles and the pressure to manage both pedagogical and social expectations. The informal nature of Facebook sometimes made it difficult to maintain an appropriate professional distance. The reflective hesitation in their accounts illustrates the oscillation between freedom and vulnerability that marks the phenomenological texture of digital presence:

“Sometimes I would write a comment and then second-guess whether it was too informal. I didn’t want to come across as too friendly or too distant.” (FP3)

While students experienced emotional labor mostly in managing visibility and performative aspects, faculty members faced additional burdens related to pedagogical responsibilities and ongoing student support. Participants also reported a sense of emotional fatigue caused by Facebook’s 24/7 connectivity. This expectation was reported to be more intense among faculty than students, with female faculty noting a particularly high burden of emotional labor, intersecting with societal expectations around gendered care:

“I often felt I had to respond immediately, even outside work hours. The constant need to support students emotionally was exhausting, especially as a female faculty member.” (FP3)

Students reported similar pressures, although their experiences were shaped more by performative concerns and privacy management than by pedagogical responsibilities:

“Even though it wasn’t mandatory, it felt like I had to check Facebook every day, just in case something came up. It was like being on-call all the time.” (SP9)

Students described an ongoing tension between the desire to engage and the sensation of vulnerability. The visibility of their personal profiles, combined with academic expectations, produced discomfort and performative anxiety. This ambivalence shows the structural conditions under which participants’ self-consciousness was heightened — the gaze of others, the visibility of one’s profile, and the performative nature of participation:

“I was always wondering if I should clean up my profile, untag old photos, or change my privacy settings. It made the experience feel less academic and more performative.” (SP6)

Beyond personal boundaries, participants raised broader concerns about platform governance and institutional oversight. Faculty members questioned the ethical implications of requiring students to use a commercial platform like Facebook for educational purposes:

“There’s a policy vacuum. I wasn’t sure what the rules were. Was I even allowed to require students to use social media for coursework?” (FP3)

At a deeper level, it unveils the internal dialectic of empowerment and exposure that constituted participants’ lived experience of Facebook as a pedagogical lifeworld. While Facebook offered immediacy, flexibility, and community, it also demanded emotional labor co-shaped by role, gender, platform affordances, and academic culture, ethical navigation, and ongoing negotiation. Overall, emotional labor in this hybrid context reflects the complex interplay between personal and professional boundaries. Facebook’s success as an educational tool depended not only on how it was used but also on how it was framed, moderated, and institutionally supported.

Essence of the experience

Synthesizing the textural and structural descriptions, the essence of the experience lies in the participants’ gradual attunement to a hybrid digital-academic lifeworld. Through habitual engagement, intentional reinterpretation, and affective resonance, they constituted Facebook not merely as a tool but as an extension of their academic consciousness — a space where learning, identity, and emotion coalesced. Its significance resided not in the technology itself but in the evolving awareness through which participants made sense of, and were transformed by, their participation.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore how faculty members and students experience the educational use of Facebook through a transcendental phenomenological lens. The findings revealed three major themes: (1) Reimagining Facebook as an Academic Ecosystem, (2) Constructing Community and Belonging through Participatory Culture, and (3) Navigating Boundary Ambiguities and Emotional Labor in Hybrid Learning Spaces. These themes illuminate the complex, layered, and often contradictory ways in which a mainstream social media platform like Facebook can be appropriated for academic purposes.

Reimagining Facebook as an academic ecosystem

Participants in this study described a bottom-up, user-driven process in which Facebook evolved into a functional academic space. This aligns with previous findings suggesting that digital tools are often appropriated in unplanned ways to meet users’ needs (Coggins et al., 2021). Rather than following institutionally mandated approaches, faculty and students integrated Facebook naturally into their academic routines, driven by its familiarity, accessibility, and immediacy.

This theme also resonates with the concept of “technology domestication” (Hynes and Richardson, 2009), where users incorporate technologies into everyday life through adaptation, rather than formal training. Similar to findings by Mpungose and Khoza (2020), participants bypassed the official LMS, which they often perceived as rigid or bureaucratic, in favor of Facebook, which they were already using in their daily lives.

However, this study extends prior research by demonstrating that this transition was not merely technical but deeply cultural. It emerged from shared digital fluency and was sustained by ongoing social negotiation among users, suggesting that pedagogical innovation can arise from the informal rather than the institutional. This process can be interpreted through a constructivist lens, as faculty and students collectively co-construct knowledge and redefine learning spaces (Vygotsky, 1978; Piaget, 1971). This finding aligns with constructivist principles, showing how users actively shape the learning ecosystem according to their needs. Additionally, recent post-pandemic literature confirms the acceleration of informal, user-driven technology adoption (Kniffin and Greenleaf, 2024).

Constructing community and belonging through participatory culture

The findings also highlighted the role of Facebook in cultivating a participatory learning culture characterized by relational connectedness, co-constructed knowledge, and emotional support. This aligns with Jenkins et al.'s (2009) concept of “participatory culture,” which emphasizes low barriers to expression, strong support for creating and sharing content, informal mentorship, and a sense of social connection among participants. Similarly, Greenhow and Lewin (2015) discuss how social media platforms can bridge formal and informal learning, fostering participatory digital cultures. Greenhow et al. (2009) further note that such platforms support collaborative knowledge construction and provide emotional support among learners.

Faculty members shifted from content deliverers to facilitators and community builders, similar to what Garrison et al. (1999) describe as the “teaching presence” in the CoI framework. These observations illustrate how the CoI model’s components—teaching presence, social presence, and cognitive presence—can be applied to understand students’ and faculty’s experiences on Facebook. This aspect is consistent with social presence theory, emphasizing relational and cognitive engagement.

While previous research has acknowledged the potential of Facebook to support academic interaction (Vázquez-Cano and Díez-Arcón, 2021; Sacks et al., 2021; Hoi and Hang, 2021a; Tess, 2013), this study enriches that understanding by revealing the emotional dimensions of community building, especially in moments of academic stress. Participants viewed the Facebook as a safe space not only for intellectual engagement but also for empathy and motivation, suggesting that Facebook can help mitigate the isolating aspects of academic life when framed appropriately. This aligns with theories of social presence and digital well-being, highlighting the pedagogical importance of relational and emotional support in online learning environments. This perspective also integrates recent post-pandemic evidence on digital well-being and emotional labor (Romero-Rodríguez et al., 2023).

Importantly, the study also revealed subtle inequalities and power dynamics within these instructor-created Facebook groups. Variations in students’ digital literacy, comfort with online visibility, or willingness to engage shaped participation. Faculty-mandated use of a commercial platform raises questions regarding digital privacy, potential marginalization of less proficient or less willing students, and broader ethical implications. Addressing these dynamics deepens the understanding of participatory culture and emphasizes that educational technology use is never neutral but embedded within relational and institutional power structures.

Navigating boundary ambiguities and emotional labor in hybrid learning spaces

Despite its benefits, participants expressed concerns regarding the blurred boundaries between personal and academic domains. Faculty struggled with role ambiguity, while students felt exposed and anxious about their online identities – issues frequently noted in the literature (Van Den Beemt et al., 2019; Heidari et al., 2020; Abdous, 2019; Carpenter and Harvey, 2019; Joiner et al., 2005). These experiences can be interpreted through the lens of digital labor and emotional labor theories (Bayne et al., 2020), emphasizing the hidden pedagogical and emotional work involved in online academic engagement.

The expectation of constant availability on social media created emotional fatigue for many participants, leading to perpetual connectedness (Sheng et al., 2022; Zheng and Ling, 2021; Bright et al., 2014; Fox and Moreland, 2014; Tuğteki̇n, 2023). Moreover, ethical concerns about institutional policies and privacy were raised, reflecting broader debates around platform governance and educational responsibility (Lachheb et al., 2023; Finefter-Rosenbluh and Perrotta, 2022; Berry, 2019). Applying CoI and constructivist perspectives helps explain how these boundary ambiguities and emotional labor affect the learning experience and social interactions in hybrid educational spaces.

This theme contributes to the growing discourse on “invisible labor” in digital education, particularly emotional and relational labor that goes unrecognized but significantly shapes users’ experiences (Bayne et al., 2020). The findings emphasize that without institutional guidance or digital literacy training, the use of Facebook in education may reinforce inequalities and emotional burden rather than alleviate them. These findings are consistent with recent post-pandemic literature highlighting technostress, digital labor, and emotional fatigue (Daud, 2025).

Conclusion

This study offers an in-depth phenomenological understanding of how faculty members and students experience the use of Facebook in higher education. By examining participants’ lived experiences, the study revealed that Facebook is not merely a communication platform but an evolving academic ecosystem co-constructed through habitual use, relational dynamics, and pedagogical adaptation. The findings indicate that while Facebook facilitates collaborative learning, knowledge sharing, and a sense of community, it simultaneously introduces challenges related to boundary ambiguity, emotional labor, and ethical uncertainty. These dynamics can be conceptualized as a “dual-edged sword,” reflecting the simultaneous affordances and constraints of social media in academic contexts.

The study highlights that the educational use of Facebook is more influenced by users’ shared digital practices than by institutional directives. Faculty and students redefined the platform’s purpose through culturally embedded routines and collective negotiation, transforming Facebook into a hybrid academic space. This organic appropriation suggests that educational innovation can emerge not only through formal structures but also through informal, user-led practices that reflect contextual needs. The findings further advance the concept of “digital boundary management,” theorizing how faculty and students navigate and negotiate the blurred lines between personal and academic spheres.

In addition, the blurred boundaries between personal and academic life present persistent tensions, highlighting the emotional and ethical complexities of using Facebook in educational settings. These findings suggest that while Facebook can effectively complement formal learning environments, it should not be considered a primary educational platform without thoughtful design and institutional support.

Practical implications for educators and institutions

For instructors, leveraging Facebook may foster increased student engagement and relational connectedness, particularly when used to supplement formal instruction. However, instructors should be mindful of workload management and privacy considerations when integrating Facebook or similar social platforms into their courses.

For higher education institutions, it is critical to establish detailed policies that specify data ownership, acceptable usage hours, and the right to opt for alternative platforms, and to offer targeted digital literacy programs covering privacy management, ethical online behavior, and informed consent for educational social media use. Institutions should also develop clear procedures for reporting and addressing privacy breaches or boundary violations.

For policymakers and instructional designers, this study highlights the importance of contextualizing digital tools within the lived realities of educators and learners. Technology adoption should not be based solely on functionality but should also consider the social and emotional implications of platform use.

Additionally, institutions are encouraged to develop structured digital literacy programs that address technical competence and ethical social media use. These programs should establish transparent guidelines for responsible communication and data privacy and design workload management strategies that prevent faculty burnout in hybrid and online learning environments. Collectively, these strategies provide a theoretically informed framework for balancing the benefits and challenges of Facebook or similar social media integration in higher education.

Recommendations for future research

Future studies could explore comparative analyses of different social media platforms [e.g., WhatsApp, Discord, Instagram, Twitter (X)] and their pedagogical affordances. Longitudinal research involving a more diverse set of institutions and cultural contexts would enrich understanding of how social media use evolves over time. Additionally, research on faculty development programs that include social media pedagogy may yield practical frameworks for ethical and sustainable integration. Further research could also test and refine the “dual-edged sword” and “digital boundary management” frameworks in different educational contexts, contributing to higher-level theoretical development.

Limitations and future directions

While this study offers valuable insights into the lived experiences of faculty members and students who use Facebook for educational purposes, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small (n = 15) and drawn from a single public university in Turkey. While this is consistent with phenomenological research, which emphasizes depth over breadth, it limits the generalizability of the findings to other institutional or cultural contexts. Second, the study focused exclusively on a specific social media platform, Facebook, excluding other social media platforms that are also commonly used in educational contexts. Future research could adopt a comparative approach to examine how different platforms are experienced and appropriated by diverse user groups. Third, although efforts were made to bracket the researcher’s assumptions through epoche and reflexive journaling, the interpretive nature of qualitative inquiry always carries the risk of subjective influence. Triangulation with other data sources, such as classroom observations or participant diaries, could enhance future research. Fourth, the study focused on students and faculty members, excluding under perspectives or those of administrators and instructional designers, whose experiences could provide a more comprehensive picture of institutional dynamics.

When interpreting the findings, it is important to consider the unique characteristics of the Turkish higher education system, including its institutional hierarchies, workload expectations, and digital infrastructure, which may differ from those in other countries. These factors may affect how social media practices and pedagogical innovations develop and persist across institutions. Future research could build upon these findings by exploring cross-cultural comparisons, examining the evolution of social media use in post-pandemic hybrid learning environments, or investigating the role of emotional labor in maintaining digital academic spaces over time.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Applied Ethics Research Center of Middle East Technical University, Türkiye, on 17 August 2015 (Approval No: 28620816). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Software, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Validation, Data curation, Project administration. SY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

This article is derived from research conducted as part of the author’s doctoral dissertation at Middle East Technical University, Turkey. The author gratefully acknowledges the valuable guidance and support provided by the co-author during the dissertation process.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdous, M. (2019). Influence of satisfaction and preparedness on online students’ feelings of anxiety. Internet High. Educ. 41, 34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.01.001

Ali, R. (2023). E-tutor: understanding the use of Facebook for informal learning through the lens of uses and gratifications theory. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 20, 385–402. doi: 10.1108/itse-12-2022-0180

Alismaiel, O. A., Cifuentes-Faura, J., and Al-Rahmi, W. M. (2022). Online learning, mobile learning, and social media technologies: an empirical study on constructivism theory during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 14:11134. doi: 10.3390/su141811134

Al-Qaysi, N., Granić, A., Al-Emran, M., Ramayah, T., Garces, E., and Daim, T. U. (2023). Social media adoption in education: a systematic review of disciplines, applications, and influential factors. Technol. Soc. 73:102249. doi: 10.1016/j.techsoc.2023.102249

Al-Rahmi, A. M., Shamsuddin, A., Wahab, E., Al-Rahmi, W. M., Alyoussef, I. Y., and Crawford, J. (2022). Social media use in higher education: building a structural equation model for student satisfaction and performance. Front. Public Health 10:1003007. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1003007,

Ansari, J. A. N., and Khan, N. A. (2020). Exploring the role of social media in collaborative learning the new domain of learning. Smart Learn. Environ. 7. doi: 10.1186/s40561-020-00118-7

Astleitner, H., and Schlick, S. (2024). The social media use of college students: exploring identity development, learning support, and parallel use. Act. Learn. High. Educ. 26, 231–254. doi: 10.1177/14697874241233605

Balushi, W. A., Al-Busaidi, F. S., Malik, A., and Al-Salti, Z. (2022). Social media use in higher education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 17, 4–24. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v17i24.32399

Bayne, S., Evans, P., Ewins, R., Knox, J., and Lamb, J. (2020). The manifesto for teaching online. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Berry, S. (2019). Non-institutional learning technologies, risks and responsibilities: a critical discourse analysis of university artefacts. Res. Learn. Technol. 27. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v27.2284

Bright, L. F., Kleiser, S. B., and Grau, S. L. (2014). Too much Facebook? An exploratory examination of social media fatigue. Comput. Human Behav. 44, 148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.048

Brown, A. J. (2020). Should I stay or should I leave?: Exploring (dis)continued Facebook use after the Cambridge Analytica Scandal. Soc. Media Soc. 6. doi: 10.1177/2056305120913884

Carpenter, J. P., and Harvey, S. (2019). There’s no referee on social media: challenges in educator professional social media use. Teach. Teach. Educ. 86:102904. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2019.102904

Chen, B., and Bryer, T. (2012). Investigating instructional strategies for using social media in formal and informal learning. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 13:87. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v13i1.1027

Chen, Z., and Ramzan, M. (2024). Analyzing the role of Facebook-based e-portfolio on motivation and performance in English as a second language learning. Int. J. Engl. Lang. Lit. Stud. 13, 123–138. doi: 10.55493/5019.v13i2.5002

Coggins, S., McCampbell, M., Sharma, A., Sharma, R., Haefele, S. M., Karki, E., et al. (2021). How have smallholder farmers used digital extension tools? Developer and user voices from sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Glob. Food Secur. 32:100577. doi: 10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100577

Creswell, J. W., and Poth, C. N. (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Incorporated.

Dabbagh, N., and Kitsantas, A. (2011). Personal learning environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: a natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning. Internet High. Educ. 15, 3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.06.002

Daud, N. M. (2025). From innovation to stress: analyzing hybrid technology adoption and its role in technostress among students. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 22. doi: 10.1186/s41239-025-00529-x

Dennen, V. P., Choi, H., and Word, K. (2020). Social media, teenagers, and the school context: a scoping review of research in education and related fields. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 68, 1635–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11423-020-09796-z

Duha, M. S. U., Richardson, J. C., Ahmed, Z., and Yeasmin, F. (2022). The use of community of inquiry framework-informed Facebook discussion activities on student speaking performances in a blended EFL class. Online Learn. 26. doi: 10.24059/olj.v26i4.3490

Dule, A., Abdu, Z., Hajure, M., Mohammedhussein, M., Girma, M., Gezimu, W., et al. (2023). Facebook addiction and affected academic performance among Ethiopian university students: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 18:e0280306. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0280306,

Dzara, K., Kelleher, A., and Ramani, S. (2021). Fostering educator identity through social media. Clin. Teach. 18, 607–613. doi: 10.1111/tct.13414,

Finefter-Rosenbluh, I., and Perrotta, C. (2022). How do teachers enact assessment policies as they navigate critical ethical incidents in digital spaces? Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 44, 220–238. doi: 10.1080/01425692.2022.2145934

Fox, J., and Moreland, J. J. (2014). The dark side of social networking sites: an exploration of the relational and psychological stressors associated with Facebook use and affordances. Comput. Human Behav. 45, 168–176. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.083

Fu, S., and Li, H. (2020). Understanding social media discontinuance from social cognitive perspective: evidence from Facebook users. J. Inf. Sci. 48, 544–560. doi: 10.1177/0165551520968688

Garrison, D., Anderson, T., and Archer, W. (1999). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: computer conferencing in higher education. Internet High. Educ. 2, 87–105. doi: 10.1016/s1096-7516(00)00016-6

Greenhow, C., and Askari, E. (2015). Learning and teaching with social network sites: a decade of research in K-12 related education. Educ. Inf. Technol. 22, 623–645. doi: 10.1007/s10639-015-9446-9

Greenhow, C., and Lewin, C. (2015). Social media and education: reconceptualizing the boundaries of formal and informal learning. Learn. Media Technol. 41, 6–30. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2015.1064954

Greenhow, C., Robelia, B., and Hughes, J. E. (2009). Learning, teaching, and scholarship in a digital age. Educ. Res. 38, 246–259. doi: 10.3102/0013189x09336671

Hamadi, M., El-Den, J., Azam, S., and Sriratanaviriyakul, N. (2021). Integrating social media as cooperative learning tool in higher education classrooms: an empirical study. J. King Saud Univ. - Comput. Inf. Sci. 34, 3722–3731. doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.12.007

Haşiloğlu, M. A., Çalhan, H. S., and Ustaoğlu, M. E. (2020). Determining the views of the secondary school science teachers about the use of social media in education. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 29, 346–354. doi: 10.1007/s10956-020-09820-0

Heidari, E., Salimi, G., and Mehrvarz, M. (2020). The influence of online social networks and online social capital on constructing a new students’ professional identity. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31, 214–231. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2020.1769682

Hew, K. F. (2011). Students’ and teachers’ use of Facebook. Comput. Human Behav. 27, 662–676. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2010.11.020

Hoi, V. N. (2021). Augmenting student engagement through the use of social media: the role of knowledge sharing behaviour and knowledge sharing self-efficacy. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31, 4021–4033. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2021.1948871

Hoi, V. N., and Hang, H. L. (2021a). Understanding students’ behavioural intention to use Facebook as a supplementary learning platform: a mixed methods approach. Educ. Inf. Technol. 26, 5991–6011. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10565-5

Hoi, V. N., and Hang, H. L. (2021b). Student engagement in the Facebook learning environment: a person-centred study. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 60, 170–195. doi: 10.1177/07356331211030158

Husserl, E. (1970). The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Hynes, D., and Richardson, H. (2009). What use is domestication theory to information systems research?. Hershey, PA: IGI Global eBooks, 482–494.

Jenkins, H., Purushotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K., and Robison, A. J. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press eBooks.

Joiner, R., Brosnan, M., Duffield, J., Gavin, J., and Maras, P. (2005). The relationship between internet identification, internet anxiety, and internet use. Comput. Human Behav. 23, 1408–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2005.03.002

Kniffin, L. E., and Greenleaf, J. (2024). Hybrid teaching and learning in higher education: an appreciative inquiry. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 35:136–146.

Kumi-Yeboah, A., Sallar, A., Kiramba, L. K., and Kim, Y. (2020). Exploring the use of digital technologies from the perspective of diverse learners in online learning environments. Online Learn. 24:42–63. doi: 10.24059/olj.v24i4.2323

Lachheb, A., Abramenka-Lachheb, V., Moore, S., and Gray, C. (2023). The role of design ethics in maintaining students’ privacy: a call to action to learning designers in higher education. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 54, 1653–1670. doi: 10.1111/bjet.13382

Liljekvist, Y. E., Randahl, A., Van Bommel, J., and Olin-Scheller, C. (2020). Facebook for professional development: pedagogical content knowledge in the Centre of teachers’ online communities. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 65, 723–735. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2020.1754900

Lincoln, Y. S., and Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 9, 438–439. doi: 10.1016/0147-1767(85)90062-8

Low, W. W., and Wong, K. S. (2021). The status quo of Facebook usage among young generations in civil engineering education. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 23, 1471–1483. doi: 10.1080/15623599.2021.1976453

Manca, S. (2019). Snapping, pinning, liking, or texting: investigating social media in higher education beyond Facebook. Internet High. Educ. 44:100707. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2019.100707

Masood, A., Luqman, A., Feng, Y., and Ali, A. (2020). Adverse consequences of excessive social networking site use on academic performance: explaining underlying mechanism from stress perspective. Comput. Human Behav. 113:106476. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106476

Mpungose, C. B., and Khoza, S. B. (2020). Post students’ experiences on the use of Moodle and canvas learning management systems. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 27, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10758-020-09475-1

Muls, J., De Backer, F., Thomas, V., Zhu, C., and Lombaerts, K. (2019). Facebook class groups of high school students: their role in establishing social dynamics and learning experiences. Learn. Environ. Res. 23, 235–250. doi: 10.1007/s10984-019-09298-7

Piaget, J. (1971). Science of education and the psychology of the child. New York, NY: Viking Press.

Poshka, A. (2020). Digital culture and social media versus traditional education. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 5, 201–205. doi: 10.15503/jecs20141.201.205

Qassrawi, R. M., and Karasneh, S. M. A. (2023). Benefits of Facebook usage (as a web 2.0 application) in foreign language instruction in higher education: a meta-analysis study. Cogent Arts Humanit. 10. doi: 10.1080/23311983.2023.2185447

Qureshi, M. A., Khaskheli, A., Qureshi, J. A., Raza, S. A., and Yousufi, S. Q. (2021). Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31, 2371–2391. doi: 10.1080/10494820.2021.1884886

Romero-Rodríguez, J., Hinojo-Lucena, F., Kopecký, K., and García-González, A. (2023). Fatiga digital en estudiantes universitarios como consecuencia de la enseñanza online durante la pandemia Covid-19. Educación XX1 26, 165–184. doi: 10.5944/educxx1.34530

Rukavina, T. V., Viskić, J., Poplašen, L. M., Relić, D., Marelić, M., Jokic, D., et al. (2021). Dangers and benefits of social media on e-professionalism of health care professionals: scoping review. J. Med. Internet Res. 23:e25770. doi: 10.2196/25770,

Sacks, B., Gressier, C., and Maldon, J. (2021). #REALTALK: Facebook confessions pages as a data resource for academic and student support services at universities. Learn. Media Technol. 46, 550–563. doi: 10.1080/17439884.2021.1946559

Salas-Rueda, R. (2021). Analysis of Facebook in the teaching-learning process about mathematics through data science. Can. J. Learn. Technol. 47. doi: 10.21432/cjlt27895

Shank, G. D. (2002). Qualitative research: A personal skills approach. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall.

Sheng, N., Yang, C., Han, L., and Jou, M. (2022). Too much overload and concerns: antecedents of social media fatigue and the mediating role of emotional exhaustion. Comput. Human Behav. 139:107500. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107500

Stickler, U., and Hampel, R. (2019). Qualitative research in online language learning: what can it do? Int. J. Comput.-Assist. Lang. Learn. Teach. 9, 14–28. doi: 10.4018/ijcallt.2019070102

Tess, P. A. (2013). The role of social media in higher education classes (real and virtual) – a literature review. Comput. Human Behav. 29, A60–A68. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.032

Timonen, P., and Ruokamo, H. (2021). Designing a preliminary model of coaching pedagogy for synchronous collaborative online learning. J. Pac. Rim Psychol. 15:1–22. doi: 10.1177/1834490921991430

Todorovic, M., Coyne, E., Gopalan, V., Oh, Y., Landowski, L., and Barton, M. (2020). Twelve tips for using Facebook as a learning platform. Med. Teach. 43, 1261–1266. doi: 10.1080/0142159x.2020.1854708,

Tuğteki̇n, U. (2023). Factors influencing online learning fatigue among blended learners in higher education. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 6, 16–32. doi: 10.31681/jetol.1161386

Van Den Beemt, A., Thurlings, M., and Willems, M. (2019). Towards an understanding of social media use in the classroom: a literature review. Technol. Pedagog. Educ. 29, 35–55. doi: 10.1080/1475939x.2019.1695657

Vázquez-Cano, N. E., and Díez-Arcón, N. P. (2021). Facebook or LMS in distance education? Why university students prefer to interact in Facebook groups. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 22, 119–141. doi: 10.19173/irrodl.v22i3.5479

VERBI Software 2022 MAXQDA 2022 [computer software] VERBI Software. Available online at: https://www.maxqda.com (Accessed September 20, 2022).

Virtanen, A., Lauritsalo, K., Mäkinen, T., Hurskainen, H., and Tynjälä, P. (2022). The role of positive atmosphere on learning generic skills in higher education—experiences of physical education students. Front. Educ. 7:886139. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.886139

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman, Eds. & Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press eBooks.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1980). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Woodford, H., Southcott, J., and Gindidis, M. (2022). Lurking with intent: teacher purposeful learning using Facebook. Teach. Teach. Educ. 121:103913. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103913

Zheng, H., and Ling, R. (2021). Drivers of social media fatigue: a systematic review. Telemat. Inform. 64:101696. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2021.101696

Appendix A

Sample interview questions

This appendix presents a sample of the semi-structured interview questions used to explore participants’ lived experiences of using Facebook for educational purposes. Questions were organized around three key domains reflecting the study’s longitudinal design: (1) initial adoption and expectations, (2) evolving practices and community formation, and (3) boundary management and emotional experiences. The phenomenological approach allowed participants to elaborate freely, with follow-up prompts as needed.

1.Initial Adoption and Expectations (Time 1)

o How did you first begin using Facebook for academic purposes?

o What motivated you or your peers to use it rather than formal learning platforms (e.g., LMSs)?

o What were your initial feelings or expectations about its usefulness for teaching or learning?

o Can you describe an early moment when you realized Facebook might support your educational goals?

2. Evolving Practices and Community Formation (Time 2)

o How has your use of Facebook changed over time in your courses or study groups?

o What kinds of interactions (posts, comments, discussions, file sharing, etc.) became most valuable to you?

o In what ways, if any, did you feel a sense of belonging or community within your academic Facebook groups?

o How did participation or collaboration differ from your experiences in more formal settings?

3. Boundary Management and Emotional Experiences (Time 3)

o How do you balance personal and academic identities while using Facebook?

o Have you experienced any form of stress, fatigue, or emotional tension related to constant connectivity?

o How do you decide what to share publicly versus privately in academic interactions?

o What concerns do you have about privacy, professionalism, or institutional support when using social media for education?

Keywords: transcendental phenomenology, digital pedagogy, educational use of Facebook, higher education, lived experiences, online learning environments

Citation: Kadirhan Z and Yildirim S (2025) The educational use of Facebook: a phenomenological exploration of faculty members’ and students’ lived experiences. Front. Educ. 10:1719345. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1719345

Edited by:

Jiayi Wang, De Montfort University, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ninggui Duan, Youjiang Medical University for Nationalities, ChinaNurgün Gençel, Bartin University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Kadirhan and Yildirim. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zafer Kadirhan, emFmZXJrYWRpcmhhbkBnbWFpbC5jb20=; emthZGlyaGFuQGFua2FyYS5lZHUudHI=

†ORCID: Zafer Kadirhan, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7839-5319; Soner Yildirim, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3167-2112

Zafer Kadirhan

Zafer Kadirhan Soner Yildirim2†

Soner Yildirim2†