- 1English Department, Osaka Jogakuin University, Osaka, Japan

- 2Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Hiroshima University, Higashi Hiroshima, Japan

Evaluation of English as an additional language (L2) speech comprehensibility in classroom and standardized test situations is important for students’ academic and career success. While previous research has found phonetic differences between male and female speech, as well as disparities in language learning ability and academic achievement, little is known about how these gender-related factors affect listener evaluations of L2 speech. This study examined responses of 201 raters from 23 first language (L1) backgrounds to the question of whether or not there are differences in male and female English L2 speaker comprehensibility. The results indicated that 66.7% perceived no difference, 27.9% judged female speakers to be easier to understand, and only 5.5% judged male speakers to be easier to understand. Written comments were coded and frequencies of codes compared in terms of rater sex and teaching experience. While overall likelihood of perceiving gender effects did not differ, the reasons given did. Male raters and teachers tended to reject gender differences on philosophical grounds, whereas students more often reported never noticing them. Among those who perceived gender differences, lower male voice pitch was seen as hindering intelligibility, while females were thought to make greater efforts at clarity and correction. Greater familiarity with female L2 speech was also cited, highlighting potential gender bias in listener judgments of comprehensibility. Based on these findings, implications and recommendations for ensuring fairness in L2 assessment are presented.

1 Introduction

English as an additional language (L2) speech comprehensibility is important for communication success. Moreover, English L2 speech is evaluated by listeners in both informal daily interactions with other English-speaking peers, as well as in more formal educational and work settings. In addition, high stakes standardized speaking tests such as the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), can have large impacts on future educational, career, and immigration opportunities (The International English Language Testing System (IELTS), n.d.). Thus, how an L2 speaker’s comprehensibility is judged by listeners is of great importance, and it is essential that formal evaluation of L2 speech is performed in a consistent and fair manner regardless of the background of the speaker. However, listener background variables such as familiarity with L2 English speech may influence the ratings given in formal evaluations (Carey et al., 2011). In addition, biases (whether conscious or unconscious) on the part of the listener may influence their evaluations.

One important source of bias in listener evaluations is gender bias, defined as systematic differences in judgments based on gender rather than actual performance (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012). In language education, gendered assumptions have been shown to influence teaching practices and evaluations of learners (Sunderland, 2000). Research in speech perception further indicates that judgments of comprehensibility are not determined solely by linguistic features but can also be shaped by social perceptions. For example, undergraduates’ ratings of non-native English-speaking teaching assistants were influenced by perceived identity rather than actual speech quality (Rubin, 1992). Taken together, these findings suggest that listener evaluations of English L2 comprehensibility may likewise be affected by gender-related perceptions, raising important questions about fairness in assessment. With this in mind, this paper examines potential gender1 biases in comprehensibility judgments of English L2 speech, focusing on raters differentiated by gender and teaching experience.

First, this paper reviews observed differences between male and female speech performance, then examines perceptions of gender in language learning and production, and finally presents our specific research questions and findings in light of previous studies.

2 Literature review

2.1 L1 phonetic sex differences

Previous studies have found numerous differences in the phonology of L1 speech of males and females (Moyer, 2016). These can include differences in pitch (also referred to as fundamental frequency, or F0, and measured in Hertz) and pitch range, with females having higher pitch and larger range than males (Pépiot, 2014). This is likely due to physical differences in the average vocal tract lengths of males and females post-puberty, with longer vocal tracts and pharyngeal cavities in males resulting in lower frequency (F0) speech (Fitch and Giedd, 1999; Simpson, 2009). Female speech rate may also be lower than that of males (Pépiot, 2014) and there are differences in vowel space and voice-onset time (Simpson, 2009). However, some of these gender differences may be language-dependent in addition to physical (Pépiot, 2014).

There is some debate regarding what role these physical differences may have in speech intelligibility, with some studies concluding that female speakers are more intelligible, while other found males to be more intelligible, and still others found no differences in intelligibility between genders (Yoho et al., 2019). For example, Bradlow et al. (1996) found English L1 intelligibility to be higher for females than for males, although this study focused on transcription accuracy of controlled single sentences rather than spontaneous speech (conversations or monologues). Bradlow et al. (1996) did not find a relationship between F0 and intelligibility independent of gender, although a wider F0 range was associated with higher intelligibility (and females had a greater F0 range in the study). Similarly, a speech intelligibility study of Korean L1 speakers subjectively rated by trained speech pathologists indicated that women had significantly higher speech intelligibility scores than men (Kwon, 2010). Kwon (2010) concluded that this may be due to sex differences in vowel working spaces, with males having a smaller vowel working space (a typical feature of reduced or casual speech). However, there was a low correlation between F0 and F0 range and subjective speech intelligibility in this experiment (Kwon, 2010).

In addition, higher pitch may be more pronounced in women as a result of cultural factors. For example, Loveday (1981) found that female Japanese L1 speakers have a very high pitch which acoustically separates them from male Japanese L1 speakers when using polite speech, whereas English L1 speakers show much less difference in pitch between males and females, with both sexes using higher pitch to show politeness. Likewise, van Bezooijen (1995) found that Japanese women have much higher pitches compared to Dutch women, due to distinct sociocultural preferences rather than physical differences. In addition, a study of Japanese/English bilinguals living in London and Tokyo found that their pitch range varied between the two languages (Passoni et al., 2022).

In terms of the effect of listener gender on speech intelligibility, Yoho et al. (2019), note that previous studies have found differences in how male and female brains process speech, as well as anatomical differences in areas of the brain associated with different aspects of speech. In terms of evaluations of L1 speech, Ellis et al. (1996) found that male listeners found female speakers more intelligible and vice versa. Meanwhile, Yoho et al. (2019) found that while female speakers were more intelligible based on objective measures like PWC (i.e., the percentage of words correctly repeated by the listener), there was no significant differences based on listener sex. However, subjective ratings of intelligibility in laboratory settings found that male listeners were more likely than female listeners to rate female speaker as difficult to understand, although this did not occur in online crowd-sourced evaluations (Yoho et al., 2019). Yoho et al. (2019) concluded that homogeneous listener samples of convenience (such as university students) may be more sensitive to bias than more diverse samples.

Based on these studies, while there are physical differences between males and females that result in differences in voice quality, it is unclear if differences in L1 speech intelligibility are due to these physical sex characteristics rather than gendered social conditioning.

2.2 Gender and academic achievement

The stereotype that women are better at learning languages may have some basis in fact, as Cordua and Netz (2022) examined data from the German School Leavers Survey and found that women were much more likely than men to study languages and culture, as well as to report having good foreign language skills. This may partly be due to girls receiving more encouragement from teachers to study foreign languages (Kissau, 2007). Cordua and Netz (2022) also report that in Germany, female students are more likely to attend academic post-secondary schools and achieve slightly higher grades at the end of secondary school than males. Likewise, in England, boys are much less likely to study foreign languages than girls, and a higher proportion of girls receive top grades (Mills and Tinsley, 2020). In addition, Jamet (2022) reports that the 10-year average enrolment in females in foreign language courses in a Venetian university was 83.5%, while the percentage for all Italian universities was 81.7%.

In Japan, women are more likely than males to study foreign languages and have better grades (Morizumi, 2002). Furthermore, in Japan, there is a higher ratio of females to males in English as a medium of instruction (EMI) courses (Shimauchi, 2018). Women in Japan are also much more likely than males to study abroad, with 65% of Japanese studying abroad in 2021 being female (Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO), 2024). In addition, among Japanese junior high school teachers, 19.3% of female teachers have a licence to teach English (the highest percentage of all school subjects), whereas only 9.5% of male teachers have an English teaching license (Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office, 2018). However, the gender divide in English proficiency in Japan has changed over time: males born between 1913 and 1923 were 15.7 times more likely than females to have high English skills, a gap that narrowed to 0.5 times for those born between 1974 and 1983 (Terasawa, 2012). This trend may partly explain why, in 2007, young English teachers at junior high schools (under 45 years old) and high schools (under 40 years old) in Japan are more often female, whereas older English teachers are more often male (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), 2007). At present, however, disparities in English achievement in Japan are largely due to socioeconomic status (Terasawa, 2017). Moreover, Terasawa (2015) also noted that females may have fewer chances to use English in the workplace in Japan, although such opportunities are generally limited for both genders—a point also raised by Kubota (2011).

In conclusion, currently women appear to be more inclined than men to study foreign languages, although this was not always the case. In addition, women appear to excel in the language classroom in comparison to men. The next section will examine studies of differences in language performance between males and females.

2.3 Sex and L2 ability

Studies have identified many differences in L2 performance and motivation between males and females. For example, Denies et al. (2022) looked at European L2 language learners, and generally, females perform better than males, but the effect size is not large. Also, for English in particular, there was little gender advantage for males or females. Denies et al. (2022) conclude that the performance gap is due primarily to social rather than biological factors, as there is variation in the gender gap between L2 learners in different European countries.

Looking at the gender influences on interactions between teachers and students, Rahimpour and Yaghoubi-Notash (2008) examined monologues by 20 male and 20 female Iranian university English majors addressed to either male or female teachers. Rahimpour and Yaghoubi-Notash (2008) found that students’ speech was more fluent when speaking to a female teacher, while students were more grammatically accurate when talking to a male teacher. In addition, female students were more grammatically accurate in general than male students, although they were more accurate when addressing a male teacher than a female one. However, no differences in the complexity of speech were found.

In terms of motivation to learn a foreign language, Mori and Gobel (2006) found that among university Japanese EFL learners, females had significantly higher integrativeness (interest in the target language group). Similarly, female L2 learners in secondary schools in Hong Kong were also more likely to adopt a native speaker pronunciation model, while males were more accepting of local pronunciation (Chan, 2018).

Looking at speech performance differences, a study of Japanese L1 oral English test takers by O’Sullivan (2000) found that males used significantly more minimal responses, fillers, and rephrasing of questions, while women were significantly more likely to use expressions of interest in their responses. In addition, a study of Spanish and Japanese L1 English learners in the U.S.A. (Major, 2004) found males used more casual speech forms. Duryagin and Dal Maso (2022) also reported that with gender, regression modeling of survey responses showed that males were more likely to see pronunciation as less important than grammar and vocabulary, as well as to prioritize communication over pronunciation accuracy.

A review by Moyer (2016) concluded that there are many differences in male and female language learning and processing, but it is unclear if it is significant when separated from age and exposure. Moyer (2016) also notes that females have a consistent advantage over male L2 learners in terms of phonology, and this may be due to a combination of differences in response styles, differences in motivation to sound native-like, and differences in the amount of feedback and encouragement that they receive from teachers. Similarly, in a review of the effect of social factors on L2 phonology, Hansen Edwards (2008) concluded that biological gender has no effect on L2 pronunciation accuracy, but that gender as a social construct can effect the opportunities that L2 learners have to interact in the L2.

Finally, Bryła-Cruz (2021) found that, while females are often thought to have better L2 pronunciation, there is no difference in the ability of male and female Polish students to correctly perceive English segmentals. This difference between stereotypical expectations of gender performance differences and observed results indicates the need to explore the types of beliefs people may have regarding male and female L2 proficiency.

2.4 Perceptions of gender differences in L2 performance

In terms of the gender of English L2 speakers, a review article (Hansen Edwards et al., 2021) concluded that gender has no effect on language learning ability, but there are many people who believe females are better at language learning. Hansen Edwards et al. (2021) claim “That females are better at learning languages than males is a pervasive myth in L2 teaching despite a lack of conclusive evidence to demonstrate that this is the case” (p. 38). The article lists several social factors that may result in pronunciation differences between males and females. For example, men and women may have different pronunciations because they notice differences in the speech patterns of men and women and try to sound like the group they identify with. Also, women try to match native speech more than men because it is more advantageous for them to assimilate into the community. In addition, women may make more connections with the target language community and thus have more standard speech. Finally, different work environments for men and women affect language exposure.

Główka (2014) found that among Polish EFL learners in secondary schools, both teachers and students strongly believed that there was no major role for gender in learning English. However, girls in the study had significantly higher English scores than males. Główka (2014) also mentions that teachers may feel uncomfortable talking about gender differences in foreign language learning due to political correctness and wishing to avoid gender stereotypes.

In conclusion, while the evidence is not settled, many people believe that females are better at language learning than males, but others may consciously reject that notion. The next section looks at how gender may impact speech evaluation by listeners.

2.5 Gender and speech evaluation

Regarding the effect of gender on post-secondary student evaluations of peer speeches in an English L1 environment, Sellnow and Treinen (2004) concluded that the sex of the speaker and listener did not affect ratings of competence. Likewise, O’Loughlin (2002) found that for IELTS oral interviews, there were no gender effects in the interviews (i.e., the number of overlaps, interruptions, and minimal responses was similar for males and females, whether or not the examinee or the examiner shared the same gender) or ratings (i.e., the test scores were not influenced by the gender of the rater or interviewee). However, O’Loughlin (2002) mentions that this was a small study, and gender differences may be more apparent in a setting that does not use highly trained language teacher raters like IELTS does. O’Loughlin (2002) notes that many studies have found gender effects in oral interviews, however there is a great deal of inconsistency, with some studies suggesting interviewees will score higher when interviewed by a male, while others found the opposite effect.

2.6 Research questions

Previous research has observed differences between male and female speech (e.g., pitch, clarity) and also differences in learning ability and academic achievement. However, little research has examined whether these gender differences affect listener evaluations of L2 speech. This is particularly important in classroom situations where English L2 speakers are evaluated by teachers or peers, as it is important to be aware of the amount of potential gender bias that exists among listeners, as well as the reasons underlying these biases.

This mixed-methods study explored the following areas:

1. Do listeners perceive differences in the comprehensibility of male and female speakers?

2. What reasons do listeners provide for any such perceived differences?

3. Do these responses vary according to listener gender or teaching experience?

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

All participants in this study gave their written informed consent before beginning the study and were paid (50 Canadian Dollars or 5,000 Japanese Yen) upon task completion. All research methods were approved by the authors’ institutional ethics committees. Participants were recruited using advertisements posted on school bulletins and social media, personal connections, and snowball sampling. Participants completed a background questionnaire and a survey online at the participants’ homes according to their own schedule. The survey asked participants about their confidence rating English L2 speakers (and reasons for the answer given), which aspects of speech were most difficult to evaluate (and why), and are men and women equally easy to understand (and why)? This paper focuses on responses to this final survey question.

Listener participants were teachers (experienced raters) and post-secondary students (inexperienced raters) recruited from Japan and Canada with various L1s (see Table 1 for breakdown). Participant ages were not asked, as this is not the focus of this study. As shown in Table 1, there were more female than male participants (131 females and 70 males). There were also similar numbers of experienced and inexperienced raters (108 and 93). In addition, the number of years of teaching experience means and range were similar for both male and female teachers. Finally, 42 percent of participants were English L1 speakers (n = 84), 47 percent were Japanese L1 speakers (n = 94), and 11 percent were other L1 speakers (n = 23). Although this distribution provided diversity, the sample was not balanced across L1 groups. Ideally, future research would recruit more evenly distributed samples to reduce potential overrepresentation effects. Nonetheless, given that the study was conducted in Japan, where Japanese and English are the most accessible rater populations, this distribution reflects the practical constraints of the research context.

3.2 Coding method for Q1 (gender and comprehensibility)

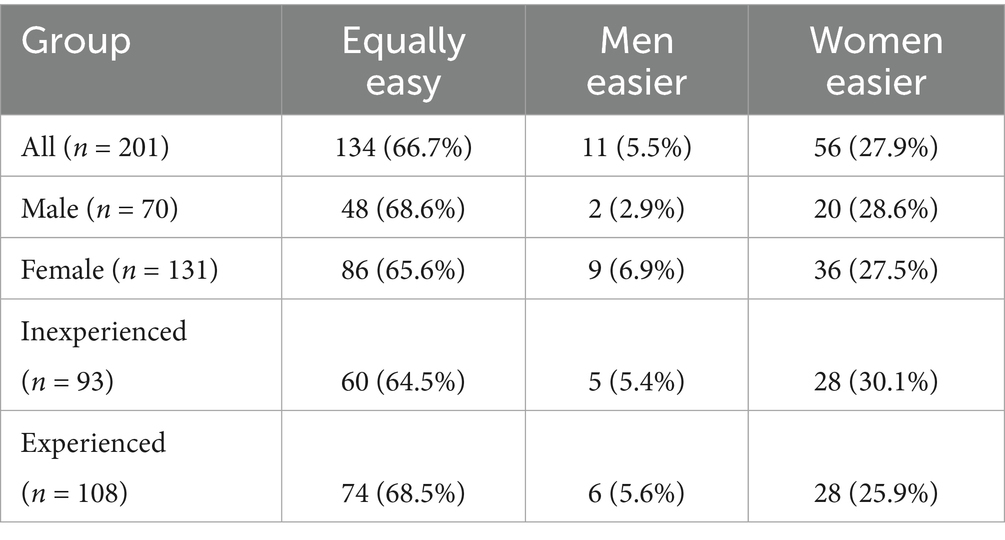

Participants were given three options to respond to the survey statement “Men and women are equally easy to understand when speaking a second language”: (1) Agree, (2) Disagree, women are easier to understand, or (3) Disagree, men are easier to understand (see Table 2 for a breakdown of response frequencies). The participants were then asked, “Why do you think so?” and given a space to write their reasoning for the selection. Results of the survey were imported from Google Forms into Microsoft Excel. Attributive coding (Saldaña, 2021) of participants (L1, sex, location, and teaching experience) was then applied. Data was cleaned to verify participant identities, remove or consolidate replicated entries, and remove entries from participants who had not completed the procedure properly.

Table 2. Participant responses to the statement “men and women are equally easy to understand when speaking a second language”.

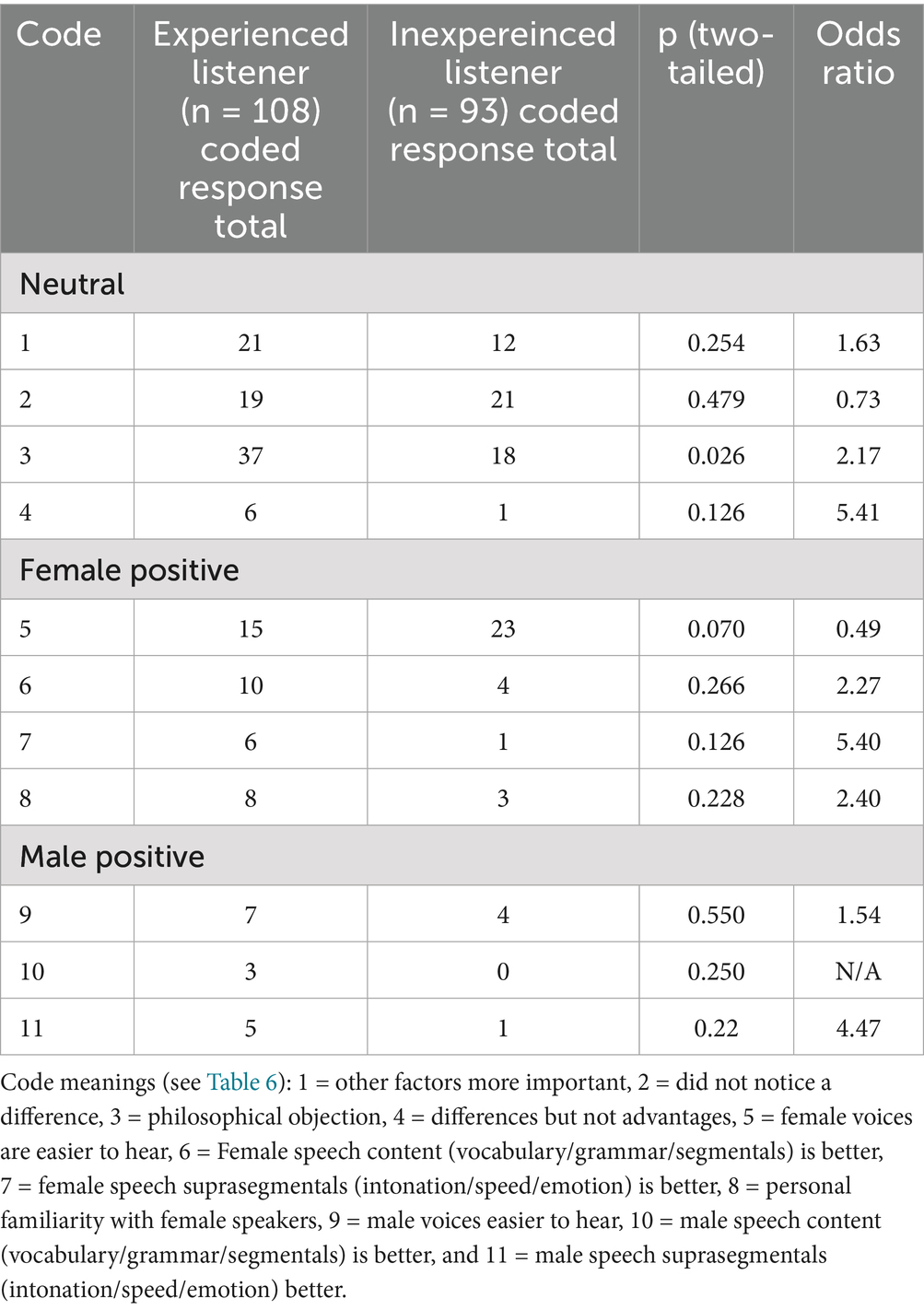

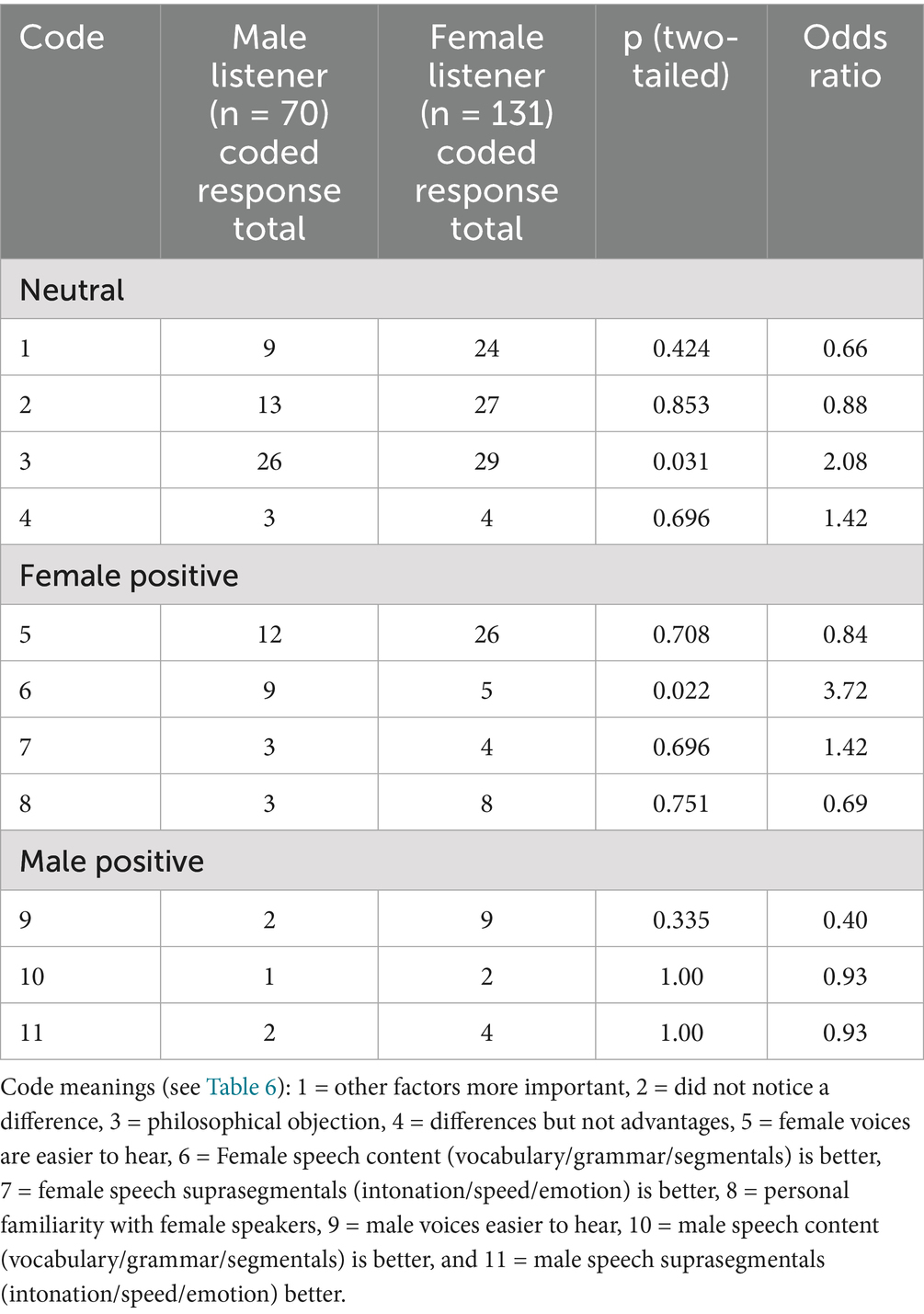

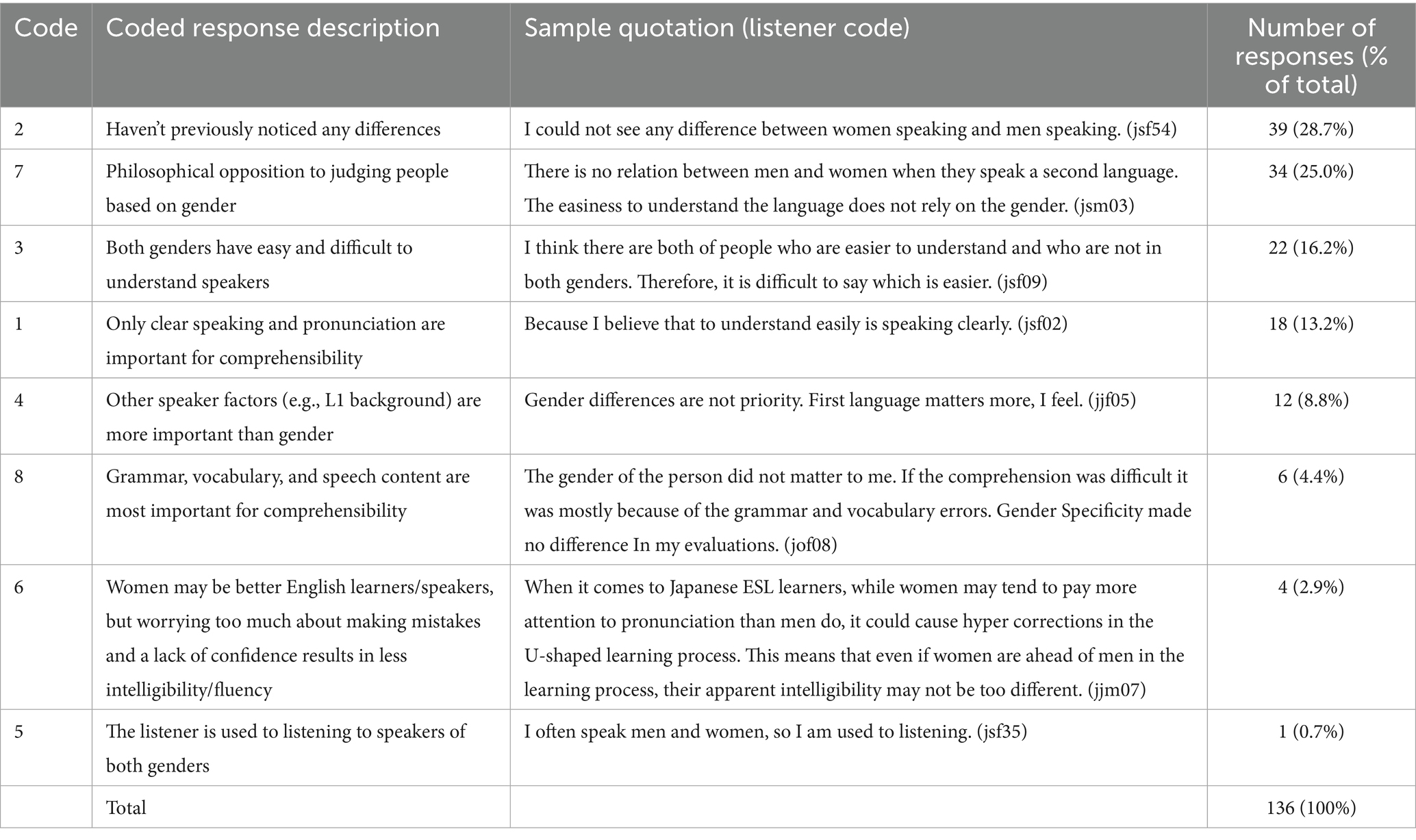

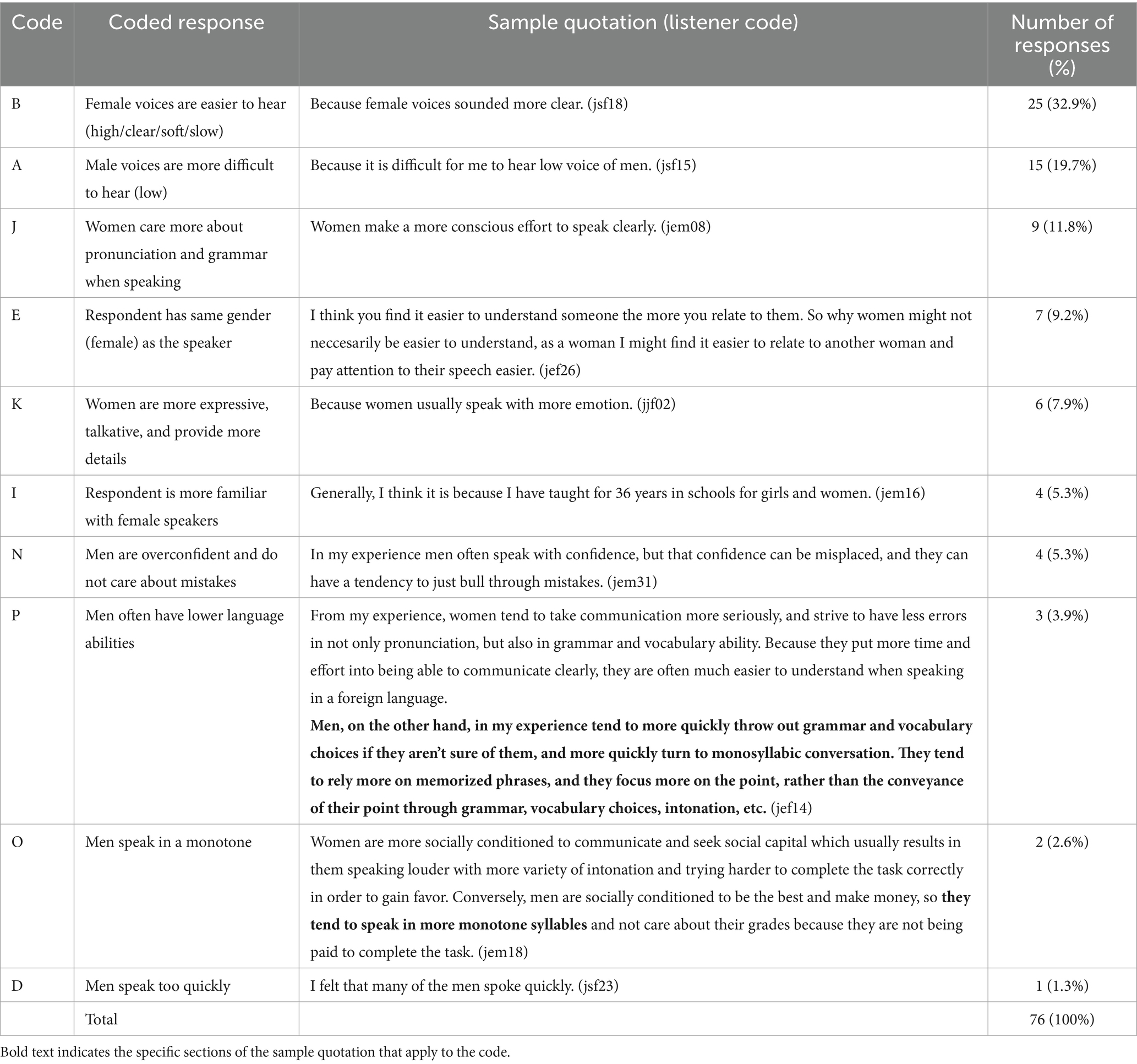

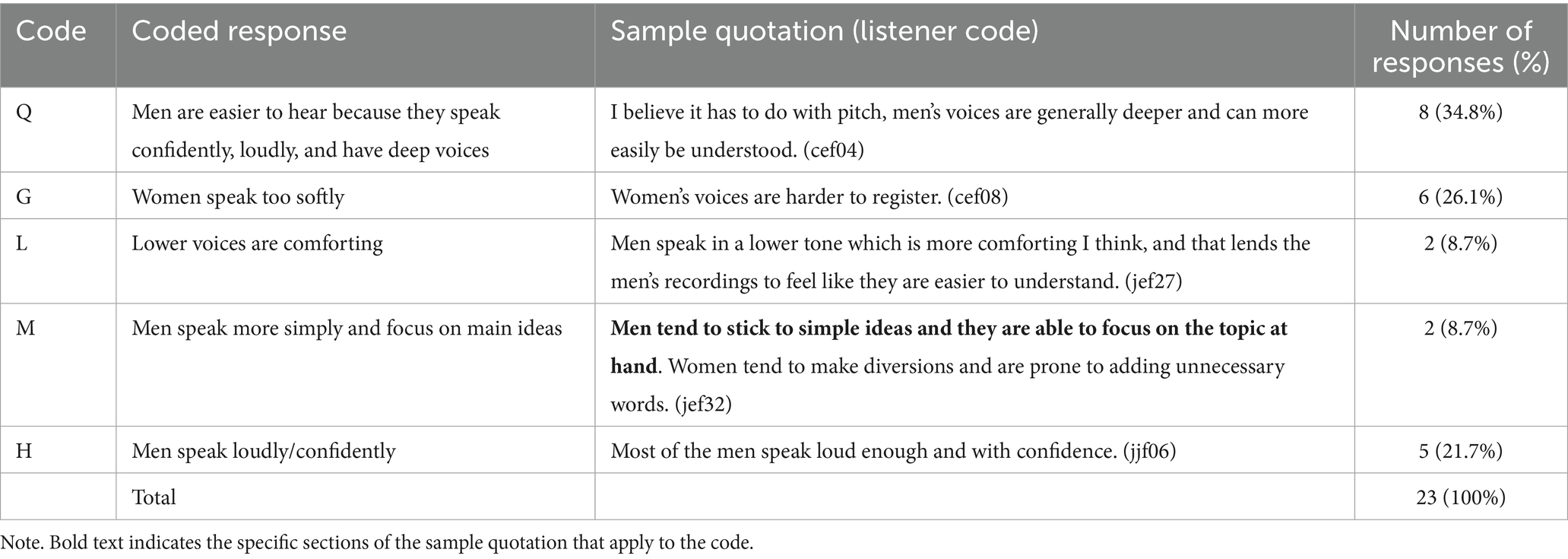

The free-written qualitative reasons were manually coded inductively following the procedures outlined by Saldaña (2021). The initial coding utilized a “splitter” or microcoding approach, with new codes created when a response did not fit existing codes (see Tables 3–5 for initial codes and example quotations). A total of 201 participants responded, but some provided free-written responses that covered more than one type of code, and others provided no response, so the number of coded response types does not match the number of participants.

Table 3. Initial coding of reasons for stating that men and women are equally easy to understand when speaking a second language.

Table 4. Initial coding of reasons for stating that women are easier to understand when speaking a second language.

Table 5. Initial coding of reasons for stating that men are easier to understand when speaking a second language.

Multiple codes were assigned if the response covered multiple code themes. For example, participant jof13 wrote “It’s not the gender but the voice and how clear the pronunciation is. However girls, especially shy Japanese girls, tend to speak softer.” In this case, the first part of the response was recorded as code 1 (only clear speaking and pronunciation are important for comprehensibility, see Table 3), while the second sentence was recorded as code G (women speak too softly, see Table 5). In another example, participant jef12 stated “If I am listening to Japanese, which is my second language, I tend to find female speech easier to understand. I think that’s because I’ve heard more of it. In terms of assessing students who are speaking English as their second language, I have noticed no difference at all.” Here, the first two sentences were coded together as code I (respondent is more familiar with female speakers, see Table 4), while the third sentence was coded as code 2 (have not previously noticed any differences, see Table 3). These codes were then revised as necessary and merged when appropriate in a secondary round of coding (see Table 6). For example, in the neutral response category (Table 3), codes 3 (both genders have easy and difficult to understand speakers) and 7 (philosophical opposition to judging people based on gender) were combined into a new code called philosophical objection because both state a conscious belief that gender does not impact comprehensibility. Responses written in Japanese were translated into English using Google Translate for coding by the English L1 researcher. Both researchers independently coded the data and resolved discrepancies through discussion. For responses originally in Japanese, the Japanese L1 researcher’s interpretation was used as the final reference in cases of disagreement. This process yielded a set of stable and conceptually coherent codes that formed the basis for subsequent qualitative analysis.

4 Result

4.1 Gender and comprehensibility: findings of research question #1

Below is a summary of the quantitative results broken down by gender and teaching experience. Two-thirds of respondents (66.7%) reported that men and women are equally easy to understand when speaking an L2, while just under one-third (27.9%) found women easier to understand and only 5.5% found men easier (Table 2).

This suggests that although most participants perceived no effect of speaker gender on comprehensibility, those who did perceive a difference showed a stronger preference for female speakers. Female respondents were more than twice as likely as male respondents to report that men were easier to understand (6.9% vs. 2.9%), whereas teaching experience showed virtually no difference (5.6% for teachers and 5.4% for students, Figure 1). However, Fisher’s exact tests, which are useful for smaller sample sizes (Field et al., 2012), revealed no significant differences in the proportions of responses between male and female respondents (p = 0.553) or experienced and inexperienced respondents (p = 0.796).

Figure 1. Participant responses to the statement “men and women are equally easy to understand when speaking a second language”.

4.2 Reasons of their perceived differences: findings of research question #2

4.2.1 Initial coding result

To better understand the reasoning behind these quantitative results, initial coding was performed on participants’ open-ended responses. The responses were initially categorized into three groups: Reasons for perceiving no difference (Table 3), reasons why women are perceived to be easier to understand (Table 4), and reasons why men are perceived to be easier to understand (Table 5).

Overall, the qualitative data provided deeper insight into how listeners conceptualize gender-related variation in comprehensibility. These responses reveal the perceptual criteria and sociolinguistic assumptions that may influence listeners’ judgments, complementing the quantitative findings presented in the previous section.

While the majority of responses indicated that there is no real difference between male and female L2 speakers, it is interesting to note that even among people claiming that there is no difference (see Table 3), a small subset (3%) commented that female speakers tend to be better speakers, but that their greater concern about making mistakes leads to disfluency compared to male speakers.

4.2.2 Second round of coding result

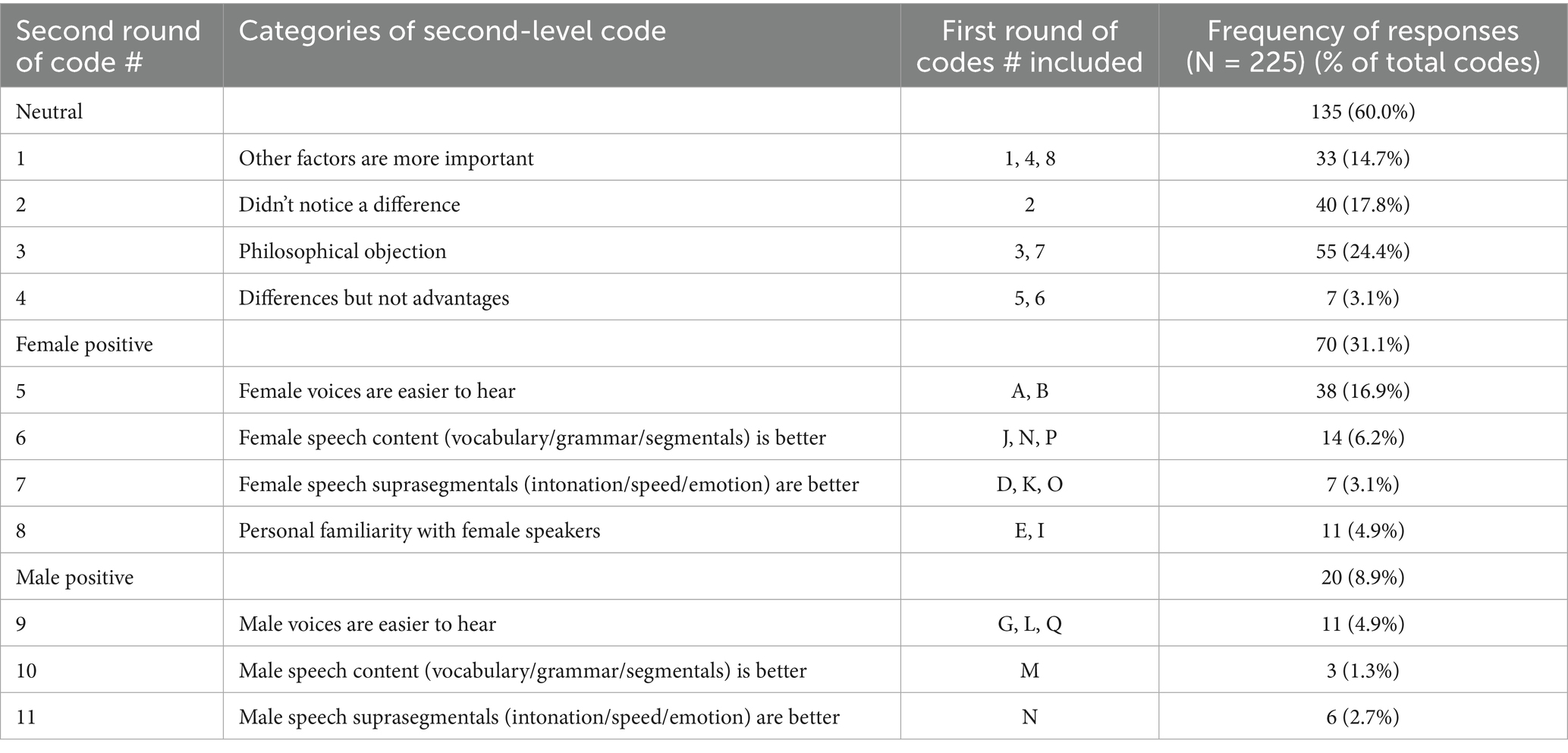

The initial coding result revealed that some response categories reflect similar perceptions from opposite directions. For example, as shown in Table 4, statements that female voices are easier to hear has the same implication as saying that male voices are difficult to hear. Likewise, the claim that women care more about speaking correctly mirrors comments that men do not care as much about making errors.

Based on these conceptual overlaps, a secondary round of coding was done to merge the initial codes into broader, thematically representative categories (see Table 6). During this process, the original three categories—neutral (Table 3), female positive (Table 4), and male positive (Table 5)—were reorganized into higher-order themes reflecting shared underlying rationales. A Fisher’s exact test, rather than a chi-squared test, was performed to compare likelihoods of the survey responses for each grouping variable because some of the cells had an expected frequency of less than 5 (Field et al., 2012; McHugh, 2013). A separate Fisher’s exact test was performed for each code (see Tables 7 and 8) due to the fact that some respondents did not provide a reason or provided responses that cover multiple distinct codes. In addition, descriptive statistics are reported below.

Table 6. Second-level coding of reasons for responses to the statement “men and women are equally easy to understand when speaking a second language”.

4.3 Differences by gender or teaching experience: findings of research question #3

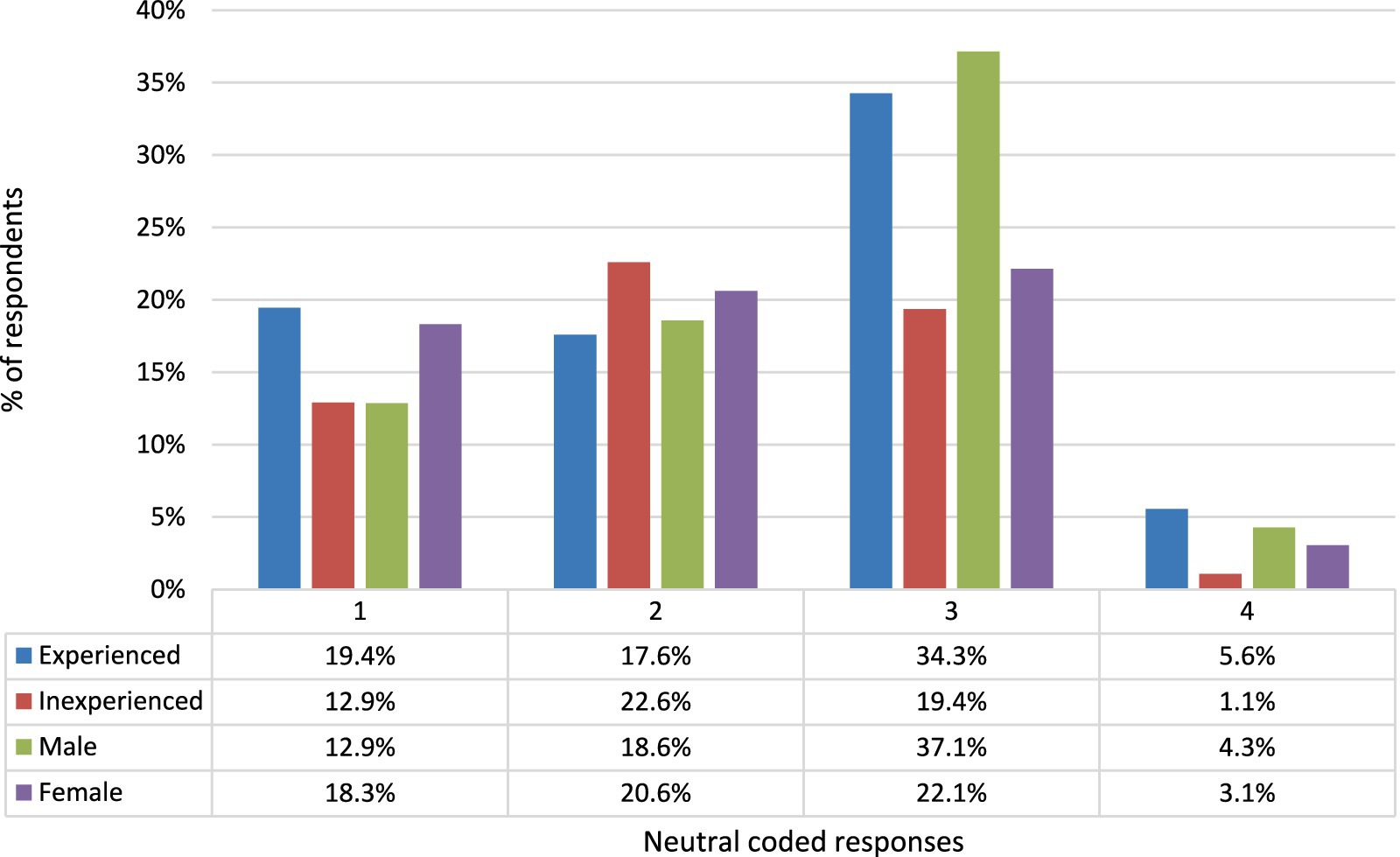

As shown in Table 6 above, the most common reason for stating that there is no difference between male and female L2 speaker comprehensibility is a philosophical objection to the notion that speaker sex is related to speech comprehensibility (code 3). As illustrated in Figure 2 and Tables 7 and 8, males were significantly more likely than females (p = 0.026) and teachers significantly more likely than students (p = 0.031) to object philosophically to the idea that there are differences in ease of understanding male and female speakers.

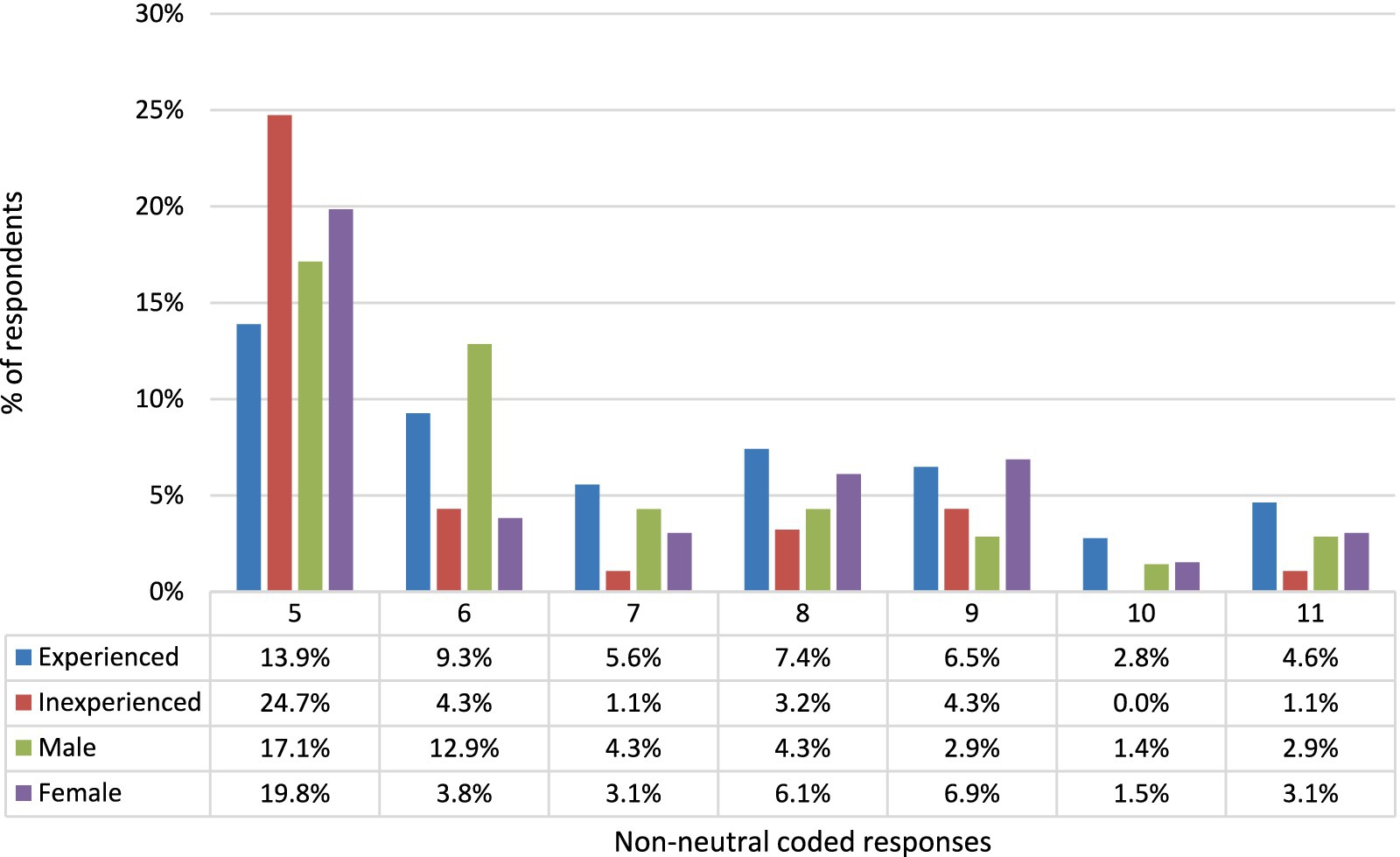

Figure 2. Breakdown of neutral-coded responses by teaching experience and sex of participants. Code meanings (see Table 6): 1 = other factors more important, 2 = did not notice a difference, 3 = philosophical objection, 4 = differences but not advantages.

While the other neutral-coded categories did not show significant differences between male and female or experienced and inexperienced participants in the Fisher’s exact tests (Tables 7 and 8), the relative prevalence of the responses is informative. The second most common neutral-coded response (Table 6) was that the listener had simply never noticed a difference (code 2), followed by code 1, stating that factors other than speaker sex were more important for comprehensibility, and code 4, that there are differences in comprehensibility, but that these differences do not advantage one group or another.

Taken together, these responses indicate that when differences are perceived, they are attributed primarily to performance-related tendencies — namely, that female speakers may produce fewer errors but also exhibit greater hesitancy due to their efforts to avoid mistakes.

As shown in Table 6, within the non-neutral category, the highest number of comments referred to the physical characteristics of voices, such as pitch, tone, and softness, on comprehensibility. Female voices were more than three times as likely to be mentioned as easy to hear (16.9% for code 5) compared to male voices (4.9% for code 9). Interestingly, while not statistically significant, Figure 3 shows that while female raters were slightly more likely than male raters (18.3% vs. 14.5%) to say that female voices are easier to hear (code 5), they were more than twice as likely to comment (6.3% vs. 2.4%) that male voices are easier to hear (code 9). Inexperienced student raters were more likely than experienced teacher raters to claim that male voice tone was difficult to understand (26.1% vs. 10.9% for code 5), whereas experienced raters were slightly more likely than inexperienced ones to mention that female voices were more difficult to understand (5.1% vs. 4.5% for code 9).

Figure 3. Breakdown of non-neutral coded responses by teaching experience and sex of participants. Code meanings (see Table 6): 5 = female voices are easier to hear, 6 = Female speech content (vocabulary/grammar/segmentals) is better, 7 = female speech suprasegmentals (intonation/speed/emotion) is better, 8 = personal familiarity with female speakers, 9 = male voices easier to hear, 10 = male speech content (vocabulary/grammar/segmentals) is better, and 11 = male speech suprasegmentals (intonation/speed/emotion) better.

Table 6 further indicates a generally more favourable impression of female speakers’ communicative ability —including grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation — than male speakers (6.2% for code 6 vs. 1.3% for code 10). However, some comments showed that male speakers might be more likely to use simple and direct vocabulary, which makes them easier to comprehend, despite this also reflecting lower foreign language abilities. This perception was particularly common among male listeners, with the only statistically significant differences in frequencies of non-neutral responses (Table 8) being between male and female listeners for code 6 (p = 0.022). As shown Figure 3, male listeners produced three times as many comments labelled with code 6 as females (10.8% vs. 3.5%).

Differences between male and female speakers was less pronounced in terms of suprasegmental features such as speed and intonation (3.1% for code 7 vs. 2.7% for code 11, see Table 6). Nevertheless, comments often indicated that female speakers were perceived as more emotionally expressive, while male speakers were seen as more confident.

Finally, in terms of familiarity (code 8, see Table 6), comments referred only to female speakers — noting that personal familiarity with female voices made their speech more comprehensible. Interestingly, no male respondents reported finding male speakers easier to understand due to shared gender, whereas several female respondents stated that they understood female speakers better because they were also female. Male raters, by contrast, often attributed their greater ease in understanding female speakers to teaching experience — particularly in women’s universities, where they interacted more frequently with female students.

Taken together, these findings reveal that listeners’ perceptions of male and female L2 speakers are shaped by a combination of acoustic, behavioural, and experiential factors rather than by inherent differences in speech ability. While female speakers were often described as clearer and more careful, this perception was intertwined with gendered expectations of diligence. Male speakers, on the other hand, were occasionally viewed as more confident or direct, though sometimes at the expense of linguistic accuracy. Overall, the qualitative data suggest that judgments of comprehensibility reflect socially mediated beliefs about gender and communication style. These patterns will be further examined in the following section in relation to broader sociolinguistic and pedagogical implications.

5 Discussion

This study examined the extent to which listeners perceived differences in the L2 English speech comprehensibility of male and female speakers, as well as whether these responses differ based on listener gender and teaching experience.

Regarding the first research question concerning the prevalence of perceived gender-based comprehensibility differences, results indicated that two-thirds of participants either did not consciously notice differences in comprehensibility between male and female speakers, or they consciously rejected the notion that inherent gender-based differences exist. Furthermore, no significant differences were found between male and female listeners, nor between experienced (teacher) and inexperienced (student) participants. This pattern is broadly consistent with Główka (2014), in that teachers and students both strongly rejected gender as a factor in language attainment, although that study did not specifically address comprehensibility.

However, the absence of significant gender effects in subjective listener perceptions of comprehensibility contrasts previous findings from L1 intelligibility studies (Ellis et al., 1996; Yoho et al., 2019). Among listeners who noticed a difference in comprehensibility, the majority had a negative view of male speaker comprehensibility, with participants five times more likely to say that female speakers are easier to understand than male speakers. This result reflects earlier L1 studies that identified higher intelligibility for female speech (Bradlow et al., 1996; Yoho et al., 2019) and aligns with the prevailing sentiment that women are better language learners in general (Hansen Edwards et al., 2021).

The second research question investigated the reasons for perceived differences, or lack of differences, in male and female L2 speech comprehensibility. Among those who reported no differences, the most common explanation was a conscious philosophical rejection of the idea that gender should influence comprehensibility, followed by the simple observation that they had never noticed such differences. Male listeners and teachers were significantly more likely to hold the philosophical view that gender plays no role, echoing Główka’s (2014) observation that teachers may be particularly cautious about reinforcing gender stereotypes. In contrast, inexperienced listeners were more likely to report having simply never noticed any differences, possibly because they have less experience evaluating speech systematically in instructional or testing contexts.

Among listeners who did perceive differences, explanations focused on both biological and behavioural factors. Many associated male speech with lower fundamental frequency (F0), perceived as hard to hear, and associated female speech with greater care and self-monitoring. However, these comments also reveal attitudinal and sociocultural assumptions about male and female learning and speaking styles. While some listeners attributed comprehensibility differences to pitch, previous research has not conclusively linked F0 to intelligibility (Bradlow et al., 1996; Kwon, 2010). Notably, while not statistically significant, inexperienced listeners were more likely than experienced ones to comment on voice-related aspects, whereas experienced listeners were more likely to comment on differences in speech content (vocabulary and grammar) and suprasegmental features. This may reflect teachers’ greater metalinguistic awareness and experience in formal assessment, allowing them to attend to more specific aspects of speech production.

Listener gender also influenced perceptions. Male listeners were significantly more likely than female listeners to mention that female speakers had better speech content, while (although the difference is not statistically significant) female listeners were more likely to say that male voices are easier to hear. This pattern seems to reflect previous findings that men focus on linguistic content and grammatical accuracy, whereas women may be more attentive to aspects of vocal delivery (Duryagin and Dal Maso, 2022).

Another factor mentioned by several participants was familiarity with female speakers. This may reflect the overrepresentation of females in EFL classes in general (Mills and Tinsley, 2020; Cordua and Netz, 2022; Jamet, 2022; Morizumi, 2002; Shimauchi, 2018), as well as the presence of women-only universities in Japan. Interestingly, only female listeners mentioned that sharing a gender with the speaker facilitated comprehension. The lack of similar comments by male listeners could stem from the slightly smaller male sample size, or from a greater tendency among male participants to reject gender-based explanations altogether.

Overall, listener responses largely correspond to views in previous studies, with female speakers seen as being more careful with pronunciation (Bryła-Cruz, 2021; Moyer, 2016) and grammar (Rahimpour and Yaghoubi-Notash, 2008), while men were thought to use simpler vocabulary, but speak more confidently (Duryagin and Dal Maso, 2022). Yet, the same features were sometimes evaluated in opposite ways. Detailed and lexically rich speech by female speakers was praised as clear by some listeners but criticized as overly complex by others. Similarly, soft-spoken delivery was considered either pleasant and clear or too quiet, and male confidence was viewed as either promoting fluency or leading to carelessness regarding accuracy.

These mixed evaluations suggest that perceived gender-based differences in L2 comprehensibility may be shaped less by objective speech characteristics and more by socially mediated expectations that listeners have accumulated over time regarding gender and communication style. In other words, while gender may serve as a perceptual frame through which listeners interpret speech behaviour, it does not necessarily confer an advantage to speakers of either gender.

These findings also highlight the value of perceptual data even in the absence of acoustic measurements. Listeners’ stated beliefs reflect their cumulative real-world experience with spoken English, shaped through long-term exposure to teachers, classmates, coworkers, media voices, and everyday interactions. As such, their perceptions represent ecologically grounded evaluations that cannot be replicated through small sets of controlled stimuli. Examining belief patterns therefore provides insight into the social and experiential factors guiding judgments of spoken English and offers a meaningful foundation for future work that will compare such perceptions with acoustic evidence.

5.1 Pedagogical implications

The findings of this study have several pedagogical implications for L2 pronunciation teaching and assessment. First, it is important to consider whether male speakers might be unintentionally penalized on speaking tests due to lower voice pitch, a physical characteristic beyond their control that may make them more difficult to hear. Similarly, perceptions of gender-related differences in pronunciation effort or lexical and grammatical knowledge could influence how raters judge speech performance. For instance, if listeners hold lower expectations for male speaker comprehensibility, male participants might appear to perform better simply by exceeding this lower baseline. Furthermore, as women are more likely to study foreign languages and humanities, male speakers may stand out due to their relative rarity, though whether this greater visibility benefits or disadvantages them in classroom or testing settings remains unclear.

Second, because some listeners associated female speech with greater accuracy and male speech with greater confidence, educators and assessors should remain mindful of such stereotypes when providing feedback or evaluating performance. Training teachers and raters to recognize and minimize implicit gender bias can help ensure fairer and more reliable evaluation practices and classroom interactions.

Third, since experienced raters tended to focus on linguistic and suprasegmental features, while inexperienced raters paid more attention to overall voice quality, teacher education programs could emphasize balanced approaches to assessing comprehensibility, integrating both detailed phonetic and broader communicative aspects. Explicit discussion of how acoustic properties such as pitch and speech rate shape listener perception may also enhance rater consistency and pedagogical awareness.

Finally, given that familiarity with particular speaker types may have influenced perceived comprehensibility, instructors should aim to provide diverse listening exposure. Encouraging students to engage with voices of varying genders, accents, and speaking styles can promote perceptual flexibility and reduce bias. Ultimately, those evaluating L2 speech should be aware of the existence of gender L2 speech comprehensibility stereotypes and corresponding potential for gender bias in their judgments and take steps to ensure that ratings reflect linguistic performance rather than socially constructed expectations about gendered communication styles.

5.2 Limitations and future directions

There are several limitations to this study. First, the number of participants was not balanced in terms of gender, with female participants (n = 131) outnumbering male participants (n = 70). This imbalance may have influenced the distribution of responses and limited the ability to generalize certain gender-related patterns. Likewise, differences in age, particularly between experienced and inexperienced listeners, may be a confounding variable. In addition, the large proportion of participants living in Japan, or with Japanese L1 backgrounds, may make the findings less generalizable to non-Japanese English L2 speaker contexts. Second, as data were collected through written responses rather than interviews, it was not possible to probe participants for clarification or elaboration on their reasoning. Consequently, some nuanced interpretations of their perceptions may not have been fully captured and there is some inherent subjectivity in the coding of responses by the researchers. Future studies could address these limitations by recruiting a more balanced sample and incorporating semi-structured interviews or focus groups to gain deeper insights into listeners’ reasoning processes. Finally, finding differences in beliefs does not necessarily mean that there are differences in behaviour when evaluating speakers. Therefore, future studies should examine whether there are differences in actual comprehensibility scores given to L2 speakers based on the gender of the listener or if there is a match in the speaker and listener gender.

Future research could extend these findings by examining the interplay between perceptual, acoustic, and sociocultural factors influencing gender-related judgments of L2 speech comprehensibility. Experimental designs incorporating controlled speech stimuli (for example, using digitally manipulated pitch or speech rate), could help disentangle the relative contributions of biological voice characteristics and listener bias. In addition, qualitative methods such as interviews or think-aloud protocols could provide richer insight into how raters form their impressions and whether these are driven by linguistic performance, social expectations, or both. Cross-linguistic comparisons and larger, more gender-balanced samples would also enable stronger generalizations and reveal whether these perceptual tendencies are culturally specific or universal.

6 Conclusion

Overall, the findings of the study suggest that most listeners do not perceive gender-based differences in L2 speech comprehensibility, but those that do tend to favor female speakers. The gender or teaching experience of the listener did not significantly influence the likelihood of perceiving such differences, nor did shared gender between speaker and listener affect comprehensibility judgments. These results indicate that perceived differences in male and female L2 speech are primarily social and perceptual rather than inherent or biological. Continued attention to awareness and fairness in evaluation will help promote more equitable practices in language teaching and assessment.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Co-creation Center for Hiroshima’s Future, Hiroshima Shudo University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PH: Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. NY: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP19K00931.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. ChatGPT was used during editing to enhance the stylistic quality of the writing. All AI-suggested revisions were checked by the authors for accuracy.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^In this paper, like others in this field (e.g., Bryła-Cruz, 2021;Moyer, 2016), gender (in the social construct sense) and sex (the biological differences sense) are used interchangeably. Participants in this study self-identified as either male or female.

References

Bradlow, A. R., Torretta, G. M., and Pisoni, D. B. (1996). Intelligibility of normal speech I: global and fine-grained acoustic-phonetic talker characteristics. Speech Comm. 20, 255–272. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(96)00063-5,

Bryła-Cruz, A. (2021). The gender factor in the perception of English segments by non-native speakers. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 11, 103–131. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2021.11.1.5

Carey, M. D., Mannell, R. H., and Dunn, P. K. (2011). Does a rater’s familiarity with a candidate’s pronunciation affect the rating in oral proficiency interviews? Lang. Test. 28, 201–219. doi: 10.1177/0265532210393704

Chan, J. Y. H. (2018). Gender and attitudes towards English varieties: implications for teaching English as a global language. System 76, 62–79. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.04.010

Cordua, F., and Netz, N. (2022). Why do women more often intend to study abroad than men? High. Educ. 83, 1079–1101. doi: 10.1007/s10734-021-00731-6

Denies, K., Heyvaert, L., Dockx, J., and Janssen, R. (2022). Mapping and explaining the gender gap in students’ second language proficiency across skills, countries and languages. Learn. Instr. 80:101618. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101618

Duryagin, P., and Dal Maso, E. (2022). “Students’ attitudes towards foreign accents: general motivation, the attainability of native-like pronunciation, and identity issues” in SAIL. eds. D. Newbold and P. Paschke, vol. 23 (Venice, Italy: Edizioni Ca’ Foscari - Venice University Press), 33–62.

Ellis, L., Fucci, D., Reynolds, L., and Benjamin, B. (1996). Effects of gender on listeners’ judgments of speech intelligibility. Percept. Mot. Skills 83, 771–775. doi: 10.2466/pms.1996.83.3.771,

Field, A., Field, Z., and Miles, J. (2012) “Discovering statistics using R.” Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, and Washington DC: Sage.

Fitch, W. T., and Giedd, J. (1999). Morphology and development of the human vocal tract: a study using magnetic resonance imaging. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106, 1511–1522. doi: 10.1121/1.427148,

Główka, D. (2014). The impact of gender on attainment in learning English as a foreign language. Stud. Second Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 617–635. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.4.3

Hansen Edwards, J. G. (2008). “Social factors and variation in production in L2 phonology” in Phonology and second language acquisition. eds. J. G. Hansen Edwards and M. L. Zampini, vol. 36 (Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company), 251–279.

Hansen Edwards, J., Chan, K. L. R., Lam, T., and Wang, Q. (2021). Social factors and the teaching of pronunciation: what the research tells us. RELC J. 52, 35–47. doi: 10.1177/0033688220960897

Jamet, M.-C. (2022). “Learner profiles and attitudes towards accent in the foreign language: the role of language backgrounds” in SAIL. Edizioni Ca’ Foscari - eds. D. Newbold and P. Paschke, vol. 23 (Venice University Press, Venice, Italy: Fondazione Università Ca’ Foscari), 3–32.

Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO) (2024). 2022(令和4)年度日本人学生留学状況調査結果 [2022 (Reiwa 4) survey results on study abroad by Japan students]. Japan Student Services Organization. Available online at: https://www.studyinjapan.go.jp/ja/_mt/2024/04/data2022n.pdf

Kissau, S. (2007). Is what’s good for the goose good for the gander? The case of male and female encouragement to study French. Foreign Lang. Ann. 40, 419–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02867.x

Kubota, R. (2011). “Immigration, diversity and language education in Japan: toward a glocal approach to teaching English” in English in Japan in the era of globalization. ed. P. Seargeant (Houndmills, UK, and New York, USA: Palgrave Macmillan UK), 101–122.

Kwon, H.-B. (2010). Gender difference in speech intelligibility using speech intelligibility tests and acoustic analyses. J. Adv. Prosthodontics 2, 71–76. doi: 10.4047/jap.2010.2.3.71,

Loveday, L. (1981). Pitch, politeness and sexual role: an exploratory investigation into the pitch correlates of English and Japanese politeness formulae. Lang. Speech 24, 71–89. doi: 10.1177/002383098102400105

Major, R. C. (2004). Gender and stylistic variation in second language phonology. Lang. Var. Chang. 16, 169–188. doi: 10.1017/S0954394504163059

McHugh, M. L. (2013). The chi-square test of independence. Biochem. Med. 23, 143–149. doi: 10.11613/bm.2013.018,

Mills, B., and Tinsley, T. (2020). Boys studying modern foreign languages at GCSE in schools in England. London: British Council. Available online at: https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/boys-languages-report.pdf (Accessed April 19, 2025).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) (2007). 中学校英語教員数(推計値)(Number of junior high school English teachers (estimated)) 高等学校英語教員数(推計値)(Number of high school English teachers (estimated)) (p. 1) Available online at: https://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/shingi/chousa/shotou/082/shiryo/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2011/02/18/1301726_03.pdf#page=1.00

Mori, S., and Gobel, P. (2006). Motivation and gender in the Japanese EFL classroom. System 34, 194–210. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2005.11.002

Morizumi, F. (2002). Does gender matter in language learning? Int. Christ. Univ. Educ. Stud. 44, 223–235. doi: 10.34577/00001071

Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., and Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 16474–16479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211286109,

Moyer, A. (2016). The puzzle of gender effects in L2 phonology. J. Second Lang. Pronunc. 2, 8–28. doi: 10.1075/jslp.2.1.01moy

O’Loughlin, K. (2002). The impact of gender in oral proficiency testing. Lang. Test. 19, 169–192. doi: 10.1191/0265532202lt226oa

O’Sullivan, B. (2000). Exploring gender and oral proficiency interview performance. System 28, 373–386. doi: 10.1016/S0346-251X(00)00018-X

Passoni, E., De Leeuw, E., and Levon, E. (2022). Bilinguals produce pitch range differently in their two languages to convey social meaning. Lang. Speech 65, 1071–1095. doi: 10.1177/00238309221105210,

Pépiot, E. (2014). Male and female speech: a study of mean f0, f0 range, phonation type and speech rate in Parisian French and American English speakers. In Speech Prosody 7, May 2014, Dublin, Ireland, HAL SHS. 305–309. Available online at: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-00999332v1

Rahimpour, M., and Yaghoubi-Notash, M. (2008). Examining teacher and student gender influence in task-prompted oral L2 variability. Issues Appl. Linguist. 16, 133–150. doi: 10.5070/L4162005097

Rubin, D. L. (1992). Nonlanguage factors affecting undergraduates’ judgments of nonnative English-speaking teaching assistants. Res. High. Educ. 33, 511–531. doi: 10.1007/BF00973770

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 4th Edn. Los Angeles, London, New Delhi, Singapore, and Washington DC: Sage.

Sellnow, D. D., and Treinen, K. P. (2004). The role of gender in perceived speaker competence: an analysis of student peer critiques. Commun. Educ. 53, 286–296. doi: 10.1080/0363452042000265215

Shimauchi, S. (2018). Gender in English-medium instruction programs: Differences in international awareness. In English-medium Instruction in Japanese Higher Education: Policy, Challenges and Outcomes. eds. A. Bradford and H. Brown, (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 180–194. doi: 10.2307/jj.22730641.16

Simpson, A. P. (2009). Phonetic differences between male and female speech. Lang Ling Compass 3, 621–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-818X.2009.00125.x

Sunderland, J. (2000). Issues of language and gender in second and foreign language education. Lang. Teach. 33, 203–223. doi: 10.1017/S0261444800015688

Terasawa, T. (2012). The ‘English divide’ in Japan: a review of the empirical research and its implications. Lang. Inf. Sci. 10, 109–124. Available online at: https://repository.dl.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/record/16550/files/lis01007.pdf

Terasawa, T. (2015). 「日本人と英語」の社会学 [Sociology of Japanese people and English language]. Tokyo: Kenkyusha.

Terasawa, T. (2017). Has socioeconomic development reduced the English divide? A statistical analysis of access to English skills in Japan. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 38, 671–685. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2016.1221412

The International English Language Testing System (IELTS). (n.d.). What can IELTS do for you? IELTS. Available online at: https://ielts.org/take-a-test/why-choose-ielts/what-can-ielts-do-for-you (Accessed May 4, 2025).

van Bezooijen, R. (1995). Sociocultural aspects of pitch differences between Japanese and Dutch women. Lang. Speech 38, 253–265. doi: 10.1177/002383099503800303,

Yoho, S. E., Borrie, S. A., Barrett, T. S., and Whittaker, D. B. (2019). Are there sex effects for speech intelligibility in American English? Examining the influence of talker, listener, and methodology. Atten. Percept. Psychophysiol. 81, 558–570. doi: 10.3758/s13414-018-1635-3,

Gender Equality Bureau Cabinet Office. (2018) 平成30年度男女共同参画社会の形成の状況:特集 多様な選択を可能にする学びの充実 男女共同参画白書 平成30年版 (White Paper on Gender Equality 2018: Special feature—Enhancing learning opportunities to enable diverse choices). Available online at: https://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/h30/gaiyou/index.html (Accessed June 1, 2025).

Keywords: L2 speech comprehensibility, gender, bias, L2 speech assessment, listener backgrounds

Citation: Head P and Yamane N (2025) Perceptions of male vs. female English L2 speaker comprehensibility. Front. Educ. 10:1726243. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1726243

Edited by:

Mohammad Najib Jaffar, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Engku Muhammad Syafiq Engku Safruddin, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, MalaysiaMargaret Anthoney, Islamic Science University of Malaysia, Malaysia

Copyright © 2025 Head and Yamane. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Philip Head, aGVhZEB3aWxtaW5hLmFjLmpw

Philip Head

Philip Head Noriko Yamane

Noriko Yamane