- 1Universidad Bolivariana del Ecuador, Durán, Ecuador

- 2Centro Universitario de Desarrollo Intelectual, Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico

- 3Universidad de La Guajira, Riohacha, La Guajira, Colombia

Maker education has emerged as an innovative pedagogical approach that promotes active learning through creation, collaboration, and technological experimentation. This study analyzed the conceptual evolution, beneficiary groups, access barriers, and STEM skills developed within makerspaces, with special attention to gender equity and educational sustainability. A systematic literature review was conducted in Scopus and Web of Science following the PRISMA protocol, including 202 documents published between 1983 and 2025, processed using R software and Zotero to identify trends, authors, themes, and theoretical gaps. The findings show a sustained increase in scientific production since 2015, a transformation of makerspaces into hybrid physical-virtual ecosystems, and an expansion of beneficiaries to more diverse communities. Although structural and cultural barriers continue to limit female participation, inclusive models mediated by artificial intelligence and design thinking are emerging. It can be stated that Maker education is evolving toward an interdisciplinary, ethical, and equitable paradigm, providing evidence of its potential to democratize innovation and strengthen STEM competencies with a social focus, while also identifying theoretical gaps related to the lack of integrative evaluative models and longitudinal studies that measure its sustainable impact.

Introduction

Maker education arises from the movement of the same name and is based on hands-on learning, in which students actively participate in the creation of tangible projects (Kwon, 2023). It focuses on the development of an innovative mindset (Scharon et al., 2024), as it fosters idea generation and the search for creative solutions to real-world problems (Mehto and Kangas, 2023). This promotes creativity and self-directed learning, cultivating an environment in which students act as creators of knowledge rather than mere consumers (Geser et al., 2019; Jeng et al., 2020).

The importance of Maker education lies in its ability to prepare students to face the challenges of an ever-changing society, since involving them in design and creation processes helps to foster an innovative mindset (Santos et al., 2024), which is highly demanded in globalized labor markets (Yang, 2022; Gratani and Capolla, 2023). Among its key features is its focus on learning by doing, a principle that motivates students to take an active role in their learning process (Liu, 2023). Unlike traditional methods, Maker education values experimentation and error as essential parts of learning (Yang, 2020), enabling students to develop resilience and adaptability (Lyon et al., 2023).

Another important feature is its emphasis on collaborative work and the development of social skills, as Maker projects are typically team-based activities that require cooperation, communication, and leadership (Pan and Chou, 2024). This collaborative environment facilitates the integration of digital and technological competencies, which are essential in the contemporary world (Peppler et al., 2022). Through the use of tools such as computer-aided design and basic programming, students acquire technical skills that are useful both in the workplace and in the creation of their own projects (Saavedra Munar et al., 2025).

Among its main components are makerspaces (Irie et al., 2019), which provide a setting where students can experiment and collaborate on multidisciplinary projects (Kalogeropoulos et al., 2020). In these spaces, learning through practice is encouraged, and the integration of knowledge from different fields such as science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics is made possible (Schaber et al., 2021; Lobato et al., 2023). Makerspaces not only provide access to physical and digital tools but also foster a culture of innovation and collaboration—fundamental skills in the entrepreneurial realm (An et al., 2020).

Although various studies have explored Maker education, its characteristics, and its components, as well as makerspaces as creative environments, it is necessary to examine how they have conceptually evolved—both their key elements and the competencies they promote—along with the institutional conditions that enable their sustainable implementation in diverse educational contexts. Therefore, this research is guided by the following question: How has international scientific production on Maker education and makerspaces evolved regarding their conceptualization, beneficiary groups—especially women—access barriers, and the development of STEM skills?

Method

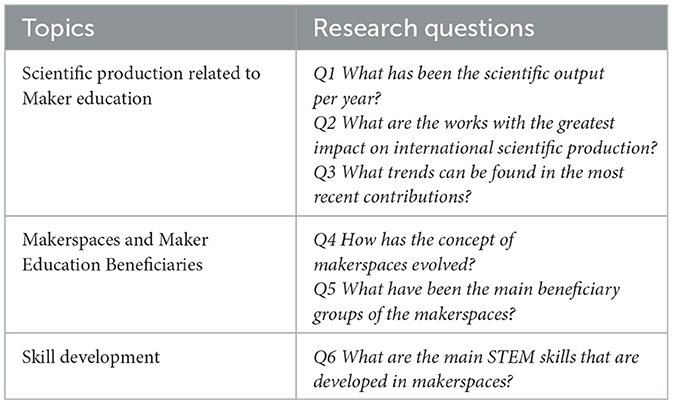

Systematic literature reviews have been widely used to identify, analyze, and rigorously synthesize the available evidence on a given phenomenon, with the aim of detecting trends, knowledge gaps, and research opportunities (Balakrisnan et al., 2023). One of the most useful methods for conducting such reviews is the PRISMA protocol (Petersen et al., 2008; Page et al., 2021). Several studies agree that the most important stages in conducting this type of research are as follows: (1) definition of research questions, (2) identification of scientific production, (3) screening and selection of studies, (4) creation and refinement of a bibliographic database, and (5) analysis of information (George-Reyes, 2022; Junior et al., 2025). Based on these stages, the research questions presented in Table 1 were developed.

Identification and screening of scientific production

Scientific documents were located and selected from two databases: Web of Science and Scopus. The search terms used were: Maker AND Women, Maker AND (STEM OR STEAM), Women AND (STEM OR STEAM), Maker AND pedagogy, Maker AND Education Invention AND pedagogy, and Skills AND (STEM OR STEAM). The results were refined based on the following criteria:

The studies had to be related to Maker education within the educational field.

They had to explicitly or implicitly refer to STEM as a skill developed through Maker education.

The works had to be articles, book chapters, or complete books in their final published versions.

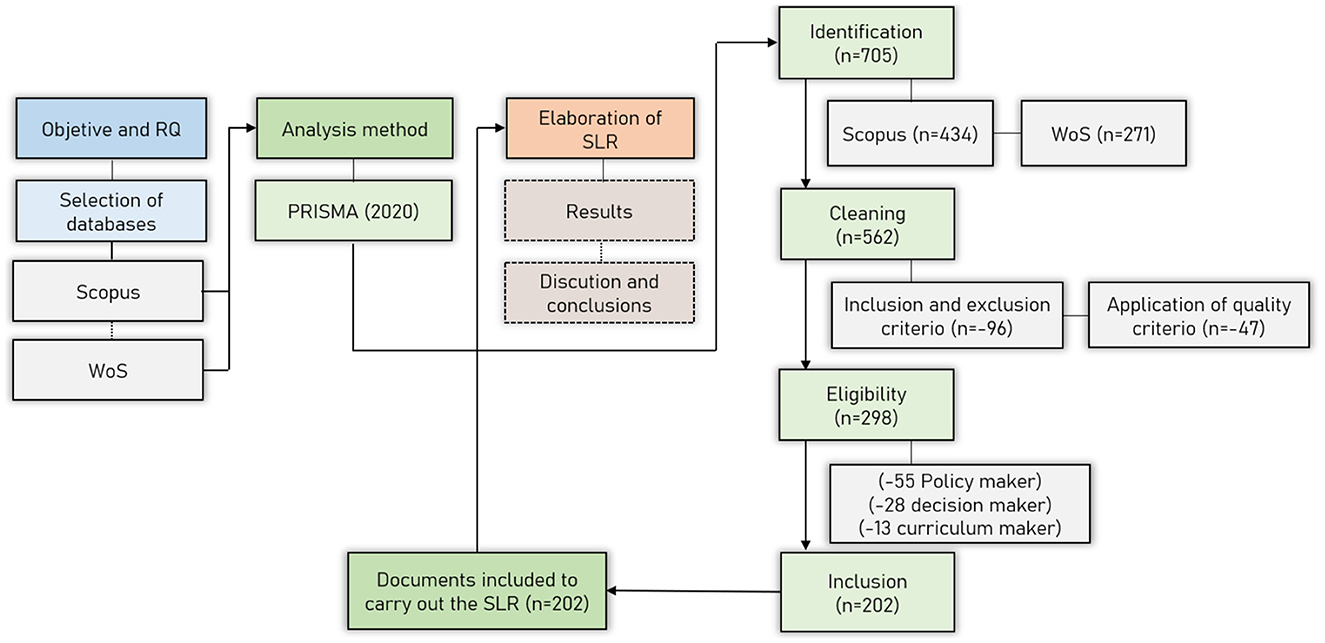

After the selection process, a systematic mapping was conducted to determine which studies met the established criteria and their relevance for addressing the research questions. Figure 1 illustrates the process carried out. At the eligibility stage, several records were excluded because the term maker was used in a different sense from Maker education: 55 papers focused on policy makers, 28 on decision makers, and 13 on curriculum makers, all of which addressed issues of governance or management rather than the Maker movement or educational makerspaces. In addition, duplicate documents appearing in both Scopus and Web of Science were removed. This refinement resulted in a final corpus of 202 documents strictly aligned with the objectives of the systematic literature review.

Database adjustment and creation

Once the screening of the documents was completed, it was concluded that the study should include 202 records (https://n9.cl/8v2nrb). A database was created in plain text (CSV) format with the following fields: author, title of the work, year, source details such as journal name, volume, year, article number, pages, DOI, abstract, keywords, references, publisher, country, language, type of document, and type of access.

Information analysis

The analysis of the information was carried out using R software, together with its specialized bibliographic libraries, mainly bibliometrix, dplyr, ggplot2, and tidyverse, which made it possible to process and systematically visualize the data obtained from the database. These tools facilitated the generation of descriptive indicators, the detection of publication trends, the identification of authors and works with greater impact, as well as the thematic and evolutionary analysis of keywords over time. Complementarily, the Zotero reference manager was used as a support tool for the organization, classification, and validation of the sources. This software made it possible to remove duplicates, standardize metadata (authors, years, titles, DOI, type of document, and keywords), and ensure consistency in the format of the references according to APA standards.

Results

Q1. Scientific production by year.

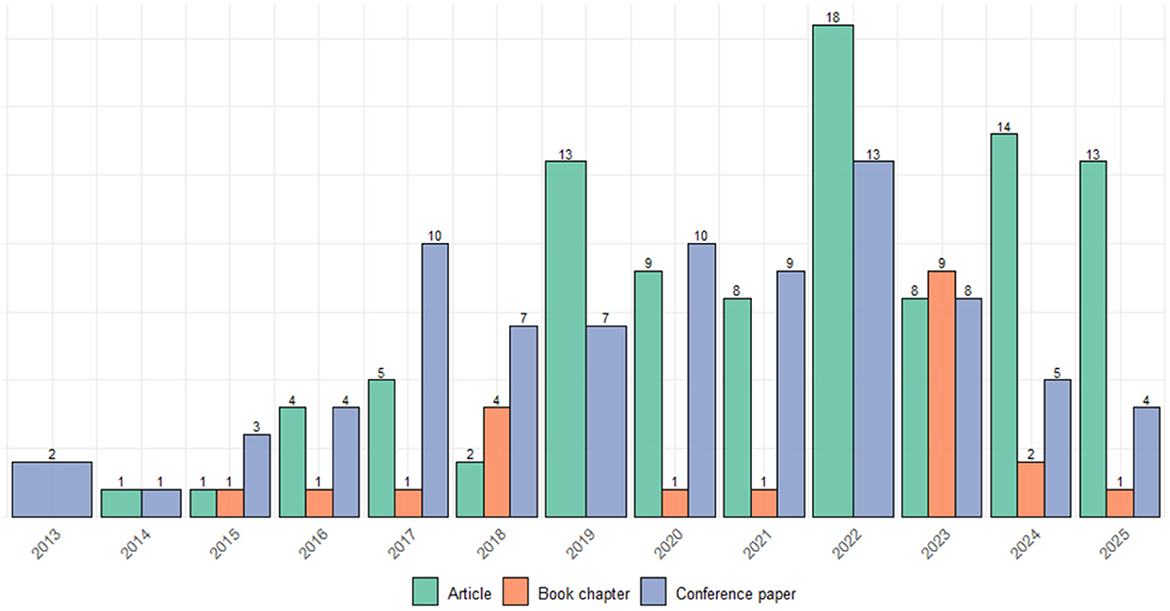

Scientific production in Maker education shows a significant upward trend since 2015. In Figure 2 it can be seen that its highest point is in 2022 with 31 publications, which reflects a sustained increase in academic interest in this field. Between 2017 and 2025 the majority of research activity is concentrated, consolidating this period as the stage of greatest maturity and thematic expansion. In the early years (2012–2015) production was incipient, with fewer than five works per year, which shows an exploratory phase of the movement. From 2016 onward, a diversification in the types of publications can be observed, highlighting the growth of journal articles and conference papers as the main channels of scientific dissemination. The peak in 2022 coincides with the proliferation of studies on educational innovation and gender equity in STEM. This temporal pattern reveals that research in Maker education has been consolidated as a stable line of interdisciplinary scientific production.

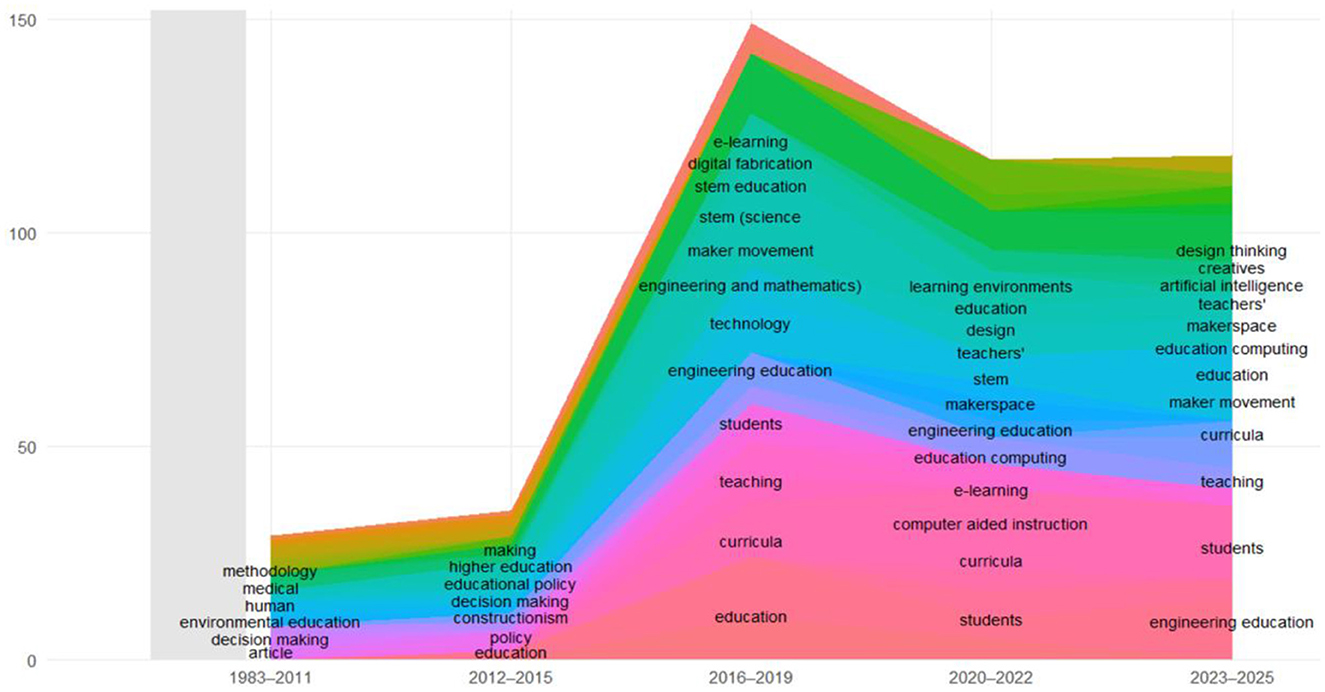

In Figure 3, the conceptual and methodological transformation of research in Maker education from 1983 to 2025 can be observed through the keywords of the scientific production, revealing a process of progressive expansion and diversification of thematic axes. In the first period (1983–2011), production focused on general methodological approaches without an explicit reference to the Maker movement, which reveals a pre-emergent stage. Between 2012 and 2015, the emergence of terms such as making, educational policy, and constructionism is observed, marking the beginning of the link between the practice of “making” and educational models. The most pronounced growth occurs in the period 2016–2019, when the frequency of keywords reaches its highest point with the incorporation of concepts such as STEM education, digital fabrication, technology, students, and maker movement. This rise reflects the consolidation of the Maker approach as an interdisciplinary field of study, associated with the teaching of science, engineering, and technology, as well as with educational innovation.

In the 2020–2022 phase, production maintains high activity but with a thematic reorientation toward learning environments, online education, and collaborative spaces (makerspaces), evidencing the influence of the pandemic context and the adaptation of Maker education to the digital sphere. Finally, in the 2023–2025 period, research lines emerge focusing on artificial intelligence, design thinking, creativity, and teacher training, suggesting a transition from a technical approach to a cognitive, inclusive model centered on twenty-first-century competencies. In this way, the analysis demonstrates a theoretical and methodological maturation of the field, which has evolved from epistemological foundations toward emerging complex pedagogical applications.

Subsequently, an analysis of the abstracts was carried out, classifying them by periods (see Figure 4). In the first period (1972–2018), the predominant topics are grouped into basic knowledge quadrants, highlighting concepts such as STEM, technology, innovation, curriculum, and engineering education. This stage evidences the consolidation of the conceptual and methodological foundations of the Maker education, oriented toward the integration of technological innovation in teaching and the strengthening of scientific competencies. During the period 2019–2021, a transition toward new topics such as curriculum design, makerspaces, and skills development is observed, reflecting the expansion of the Maker movement into formal learning contexts. This growth coincides with the proliferation of empirical research focused on the practical implementation of Maker environments in schools, teacher training, and the incorporation of emerging digital technologies. At the same time, new topics such as innovation processes and learning-based development emerge, revealing a shift in the epistemological orientation of the field, moving from material creation to the construction of collaborative and digital knowledge.

The period 2022–2026 marks conceptual maturity and thematic diversification, where topics such as artificial intelligence, creativity, design thinking, project-based learning, and teacher development are identified. This suggests a deeper integration between Maker education and artificial intelligence, as well as an emphasis on creativity, practical experience, and pedagogical reflection. Topics such as policy and learners' engagement show a shift toward more applied perspectives, while themes such as knowledge-based processes and future learning point to the development of innovative and sustainable approaches. The foregoing reveals a process of transition from technical experimentation to pedagogical consolidation, in which Maker education is redefined as an interdisciplinary field that articulates innovation, active learning, and teacher development.

Q2. Most influential works in international scientific production.

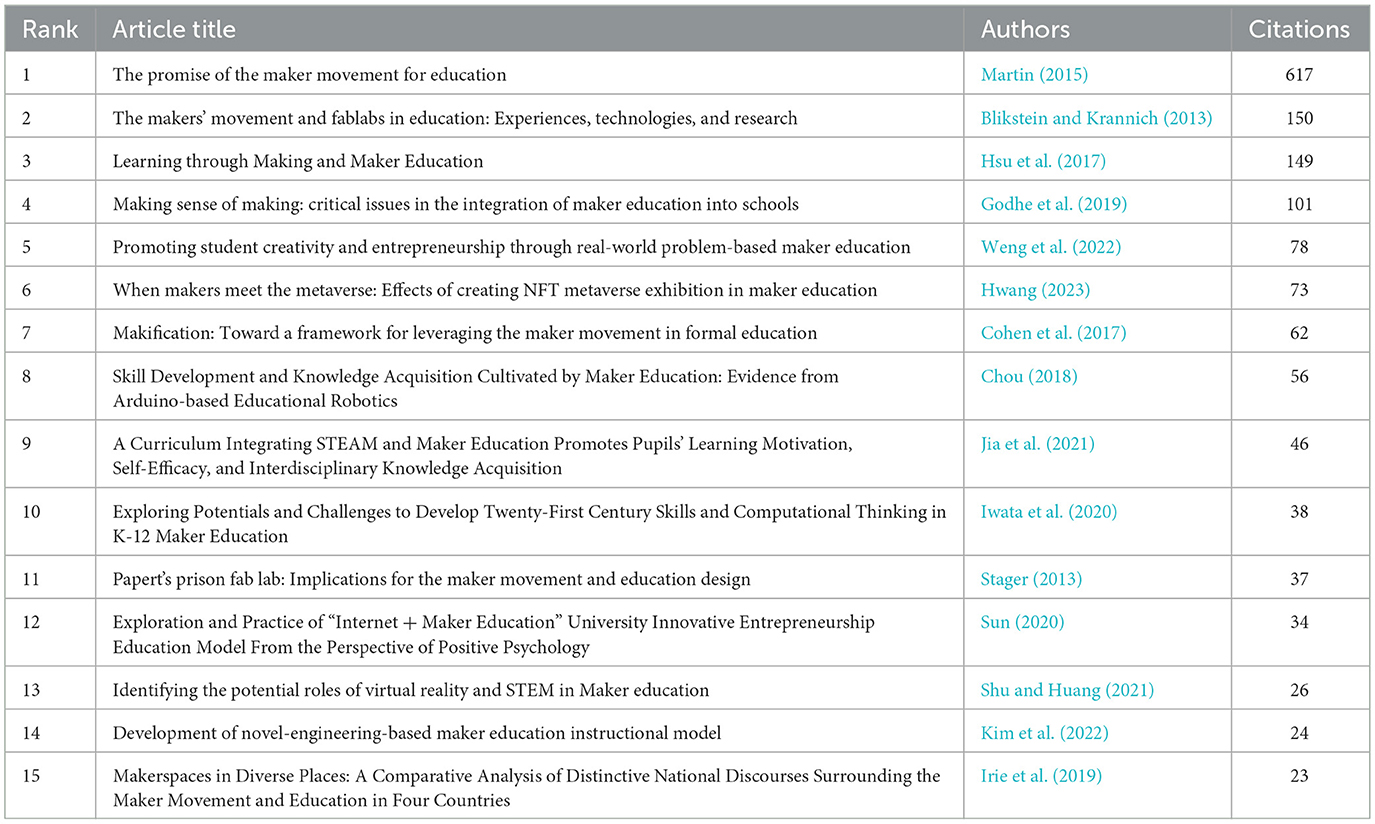

The most highly cited works were analyzed to identify the foundations of Maker education (see Table 2). In this regard, it was found that integrating the principles of Maker education places the student at the center of the knowledge construction process through design and the resolution of real-world problems Iwata et al., (2020), which breaks with traditional disciplinary fragmentation and promotes a holistic understanding of phenomena Jia et al., (2021). Likewise, according to Martin (2015), the Maker education brings the do it yourself philosophy into the educational sphere, fostering learning experiences based on design, digital fabrication, and collaborative problem-solving, which encourages the development of a Maker mindset characterized by curiosity, autonomy, and a willingness to experiment and learn from error.

Furthermore, makerspaces represent the operational core of Maker education. They are defined as collaborative learning spaces equipped with analog and digital tools (such as 3D printers, laser cutters, robotics kits, or recycled materials) that enable interdisciplinary experimentation and educational innovation. Irie et al. (2019) explain that makerspaces embody the values of the Maker education, creativity, cooperation, design, and resilience and that their implementation in schools and universities fosters autonomy, innovation, and critical thinking. In this sense, it has been stated that programs based on educational robotics, Arduino programming, and digital fabrication significantly improve students' problem-solving skills and technical knowledge (Chou, 2018).

The findings of Godhe et al. (2019) indicate that integrating Maker technologies and practices in school contexts requires a profound pedagogical reconfiguration, where teachers take on the role of mediators and facilitators of creative experiences (Stager, 2013). The authors argue that makerspaces should be conceived as communities of practice that promote peer collaboration, critical reflection, and co-evaluation of the process rather than the final product. As for their fundamental components, these include the maker mindset, project-based learning, iterative design, and collaboration. In this regard, Hsu et al. (2017) highlight that the maker mindset involves curiosity, resilience, autonomy, and openness to error values consolidated through continuous learning by doing. From a constructivist and constructionist perspective, students are encouraged to build knowledge through the manipulation of materials and technologies, fostering conceptual appropriation through tangible experience and collective work (Cohen et al., 2017).

Research by Kim et al. (2022) and Shu and Huang (2021) shows that integrating models based on design thinking and virtual reality within makerspaces can broaden their impact, especially in rural contexts or those with technological limitations. These models help democratize access to digital learning, reduce infrastructure gaps, and strengthen equitable education, turning makerspaces into sustainable and inclusive ecosystems that connect education with social and technological innovation. Weng et al. (2022) expand this perspective by demonstrating that Maker education based on real-world problems enhances creativity and student entrepreneurship. By linking the design of technological solutions with the application of the 5E learning model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate), the generation of innovative ideas, responsible decision-making, and cooperative work are stimulated.

Q3. Trends identified in recent scientific production.

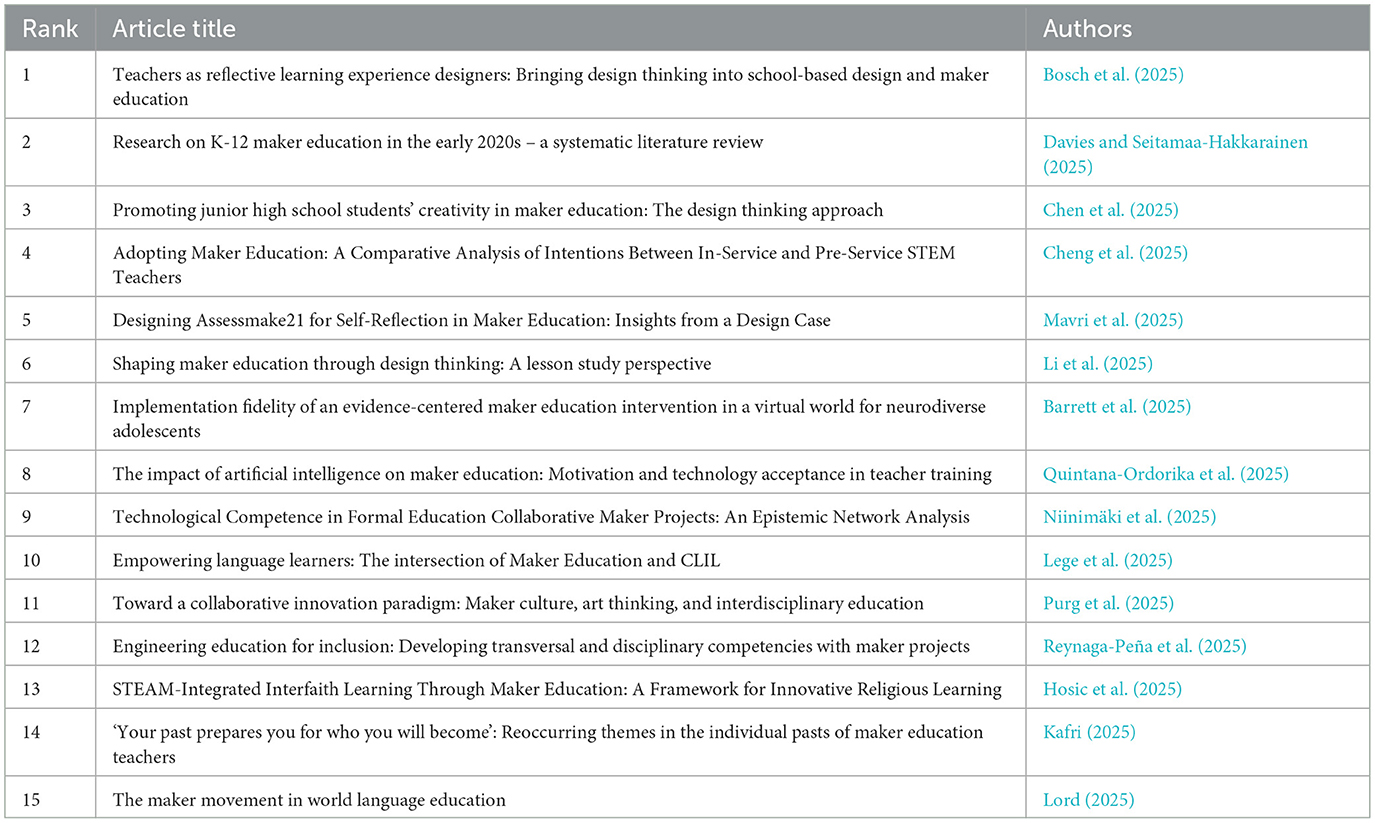

To analyze how Maker education has evolved, the scientific production corresponding to the year 2025 was reviewed. Table 3 presents a summary of the most significant contributions. The full-text analysis revealed a transformation compared to its initial formulations in the 2010s, consolidating it as a complex, interdisciplinary, and inclusive educational approach (Mavri et al., 2025). In its beginnings, Maker education focused on manual creation and digital fabrication as means to foster creativity and critical thinking; however, the latest generation of studies shows a paradigmatic shift toward the development of more structured teaching strategies with solid theoretical foundations and orientations toward equity, sustainability, and educational artificial intelligence (Reynaga-Peña et al., 2025).

In this context, Davies and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen (2025) emphasize that while earlier works focused on student motivation and engagement, current research examines implementation fidelity, cognitive impacts, and the integration of emerging technologies in learning processes. Thus, Maker education has evolved from being an experimental and extracurricular practice to becoming a formal methodology within education, particularly in early education (K−12). Likewise, recent evolution reflects an openness to new sociocultural and inclusive contexts, expanding its reach beyond traditional STEM disciplines. In this regard, Hosic et al. (2025) demonstrate that Maker education now incorporates frameworks such as intercultural learning, which use design and creation as means to foster empathy, cooperation, and ethical thinking. In this new stage, makerspaces are no longer limited to technological laboratories but are conceived as hybrid physical and virtual ecosystems capable of integrating science, art, and the humanities. Barrett et al. (2025) complement this view by showing that even neurodiverse populations actively participate in Maker environments mediated by virtual worlds, expanding the notion of accessibility and democratization of knowledge.

Therefore, Maker education today is characterized by profound evolution compared to its early stages. In this sense, Quintana-Ordorika et al. (2025) point out that the incorporation of generative AI into Maker projects increases motivation, technological acceptance, and creativity among future teachers, consolidating a pedagogical model in which technology is not only a tool but also a cognitive and ethical mediator in the educational design process (Chen et al., 2025). This evolution represents a substantial shift from the previous decade, which focused on material manipulation and physical experimentation (Cheng et al., 2025). Furthermore, Purg et al. (2025) highlight that Maker culture has evolved into a paradigm of collaborative innovation that combines technological creativity with artistic thinking and interdisciplinary education. Kafri (2025) shows that today's Maker teachers emerge from personal trajectories marked by experimentation, reflection, and the pursuit of pedagogical autonomy (Li et al., 2025), establishing themselves as agents of change within formal education, and their teaching practices are more humanized and flexible (Bosch et al., 2025).

Compared with its original components, Maker education has shifted from a model primarily centered on manual creation and digital fabrication—grounded in Papert's and Dewey's constructivist and learning by doing principles—to an interdisciplinary, inclusive, and technologically expanded approach (Niinimäki et al., 2025). In its initial conception, the three fundamental axes were the maker (the creator), the making (the process of creation), and the makerspace (the physical environment for experimentation), focused on developing technical skills and individual creativity. In contrast, the current components incorporate new dimensions: artificial intelligence and computational thinking as cognitive mediators; artistic and ethical thinking as the guiding principles of creative processes; and hybrid, collaborative environments as spaces for social and reflective learning.

Q4. How has the concept of makerspaces evolved?

Initially, makerspaces were conceptualized as physical environments for fabrication and experimentation that brought the do it yourself/do it with others (DIY/DIWO) philosophy into the educational sphere, enabling learning by doing through digital fabrication technologies such as 3D printing, laser cutting, and robotics (Zawieska and Sprońska, 2017) under constructivist frameworks (Tay and Eng, 2024). In this view, the makerspace functions as a community of practice that enables iterative design, student agency, and the solving of real-world problems (Blikstein and Krannich, 2013; Hsu et al., 2017; Martin, 2015). Moreover, its role is emphasized as an interdisciplinary hub for the development of STEM/STEAM competencies through projects and curricula that integrate science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics (Li, 2016; Iwata et al., 2020; Jia et al., 2021).

The figure shows that the concept of maker is embedded within a network of notions that expand the original meaning of the movement and help explain the evolution of makerspaces from a more comprehensive perspective. At the center, maker and makerspaces connect with nodes such as constructionism, learning, design thinking, STEM/STEAM, collaboration, and innovation, illustrating that these spaces involve not only the manipulation of tools but also a convergence of cognitive, pedagogical, and creative frameworks. The link to constructionism reinforces the idea that learning occurs through the creation of meaningful artifacts, while the connection with design thinking reflects the incorporation of iterative, reflective, and problem-oriented processes. Likewise, the association with STEM, skills, and education indicates that makerspaces function as hubs that integrate disciplines and strengthen scientific and technological competencies in authentic contexts.

The links connecting them to collaboration, innovation, and creativity reveal that these environments operate as communities of practice where knowledge is socially constructed and experimentation becomes a driver of agency, autonomy, and critical thinking. Taken together, the figure demonstrates that the evolution of the makerspace concept involves its transition from a physical fabrication site to a complex educational ecosystem where cognitive, socio-emotional, technological, and cultural processes intersect to redefine the experience of learning by making.

That is, the makerspace is described as an equipped and collaborative school laboratory oriented toward tangible products and the consolidation of a Maker mindset (curiosity, resilience, openness to error) (Tian et al., 2020). In contrast, emerging studies reconfigure makerspaces as hybrid (physical–virtual) and socio-technical ecosystems, where digital infrastructures, virtual worlds, and learning analytics are as relevant as the pedagogical frameworks of design thinking, self-reflection, and formative assessment (Cerrón-Salcedo et al., 2024). Metrics for implementation fidelity, self-assessment instruments (Assessmake21), and epistemic network analyses are introduced to map collaboration, shifting the focus from “what is made” to “how learning, collaboration, and evidence-building occur” (Feng et al., 2024; Niinimäki et al., 2025).

Thus, in a contemporary scenario, the makerspace is conceived as a reflective learning infrastructure where the teacher acts as a designer of experiences and the continuous improvement cycle guides practice (Gahoonia, 2024). Another key difference is the expansion of domains and populations served. While in previous decades they focused on STEM and tangible products (Tabarés and Boni, 2023), current studies situate makerspaces at the intersection with generative AI (Ou and Chen, 2024) as well as inclusion, broadening their purposes toward advanced learning (Lo, 2024). In this way, the impacts of AI as a cognitive mediator are explored in relation to motivation and technological acceptance among future teachers (Davies and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, 2025; Mavri et al., 2025); virtual interventions are described; and projects are articulated that integrate language and creation to strengthen communication and interdisciplinary thinking (Lord, 2025). This indicates that the makerspace has evolved from a fabrication workshop into an inclusive educational innovation platform with purposes created and shared with the community (Xu et al., 2024).

Q5. Who have been the main beneficiary groups of makerspaces?

The beneficiary groups of makerspaces have evolved over time, expanding from initial approaches focused on engineering and technology students to more diverse and inclusive communities (Gu and Yang, 2023). Initially, the beneficiaries were identified as students in basic and higher education within STEM areas, with an emphasis on developing critical thinking, creativity, and technical skills (Blikstein and Krannich, 2013). In this sense, Hsu et al. (2017) and Martin (2015) identify young people and university students as the main actors in these environments, highlighting their role in knowledge construction and technological literacy. In studies from the 2020s onward, the beneficiary population expands to include groups at risk of exclusion and diverse communities, showing a social shift in Maker education (Kim et al., 2022).

The works published in 2025 consolidate this inclusive trend. Barrett et al. (2025) highlight the benefits for neurodiverse adolescents through immersive virtual environments that promote self-expression and participation. Lord (2025) expands the beneficiaries to include foreign language learners, integrating Maker education with Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) methodologies to foster communicative competence and interdisciplinary thinking. Similarly, Mavri et al. (2025) identify its impact on engineering students and populations with disabilities by linking Maker projects with inclusive education and the development of transversal competencies. Other studies, such as those by Hosic et al. (2025), show how makerspaces benefit interreligious and multicultural communities through empathetic and creative STEAM learning.

Studies such as Premyanov et al. (2022) propose circular makerspaces as platforms for the development of urban entrepreneurs in smart and sustainable cities. Therefore, it can be stated that the beneficiaries of makerspaces have shifted from academic groups linked to STEM disciplines to include diverse populations (Lege et al., 2025). This expansion reflects a maturation of the Maker education, moving away from mere technological literacy to become an inclusive and transformative educational strategy oriented toward human development, equity, and global citizenship (Russo et al., 2022; Weng et al., 2022; Barrett et al., 2025).

Q6. What are the main STEM skills developed in makerspaces?

The main STEM skills focus on the integration of scientific, technological, engineering, and mathematical competencies with transversal skills such as creativity, problem-solving, and interdisciplinary collaboration (Rosenheck et al., 2021). In several studies, it is observed that makerspaces promote learning based on experimentation, iterative design, and reflection on the creation process, leading to the strengthening of higher-order cognitive skills (Blikstein and Krannich, 2013; Martin, 2015; Hsu et al., 2017). According to these authors, makerspaces allow students to learn science and engineering by doing, through projects involving programming, modeling, and digital fabrication. This active learning develops competencies such as logical thinking, the application of the scientific method, and the understanding of complex technological systems—fundamental pillars of STEM disciplines (Weiner et al., 2020).

From a contemporary perspective, makerspaces are noted for promoting a STEAM approach by integrating art and creativity as essential components of innovation. Weng et al. (2022) demonstrate that participation in Maker projects improves design thinking, creative problem-solving, and self-evaluation of technological processes, fostering the development of a scientific and entrepreneurial mindset. By combining digital tools such as Arduino, 3D printing, or IoT programming with collaborative processes, these spaces strengthen both technical (hard) skills—design, prototyping, coding—and soft skills related to communication, leadership, empathy, and critical thinking (Lobato et al., 2023; Shu and Huang, 2021).

Studies published in 2025 expand the understanding of STEM skills toward a more inclusive, digital, and reflective vision. For example, Li et al. (2025) use epistemic network analysis to demonstrate that makerspaces strengthen interdisciplinary technological competence by promoting collaboration among students from different fields of knowledge. Barrett et al. (2025) show that virtual Maker education environments designed for neurodiverse adolescents enhance skills such as self-regulation, complex problem-solving, and cognitive autonomy. Likewise, formative assessment and self-reflection are highlighted as mechanisms to consolidate scientific understanding and knowledge transfer (Yueh-Min et al., 2022).

Furthermore, integrating artificial intelligence as a cognitive mediator in teacher training within Maker environments strengthens advanced digital competencies such as algorithm management, data interpretation, and technological ethics (Cox, 2024; Jang, 2024). Similarly, inclusive engineering projects in makerspaces have been identified to reinforce both transversal and disciplinary competencies by linking real-world problem-solving with sustainable design and interdisciplinary collaboration (Reynaga-Peña et al., 2025). Moreover, Purg et al. (2025) broaden the notion of STEM skills by including artistic creativity, critical thinking, and empathy as necessary dimensions for educational innovation in multicultural contexts. Therefore, it can be affirmed that, today, makerspaces develop a set of expanded STEM skills ranging from technical competencies such as programming, 3D design, electronics, robotics, and mathematical modeling to cognitive and social competencies such as critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and creativity (Pols and Hut, 2023).

Discussion

This study revealed that the scientific production on Maker education demonstrates a process of theoretical and methodological consolidation that transforms an experimental movement into an interdisciplinary field of educational study. This finding is supported by the upward trend observed from 2015 to its peak in 2022, where Figure 2 shows sustained growth marking the maturity of the field. In this regard, Martin (2015) highlights that Maker education represents a transformative promise for educational systems, while Davies and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen (2025) recognize its transition toward systematized and inclusive approaches. The temporal expansion of scientific production shows that Maker education has evolved from an emerging phenomenon into a consolidated domain of educational innovation.

It was also observed that the most influential studies in the field establish a reference framework for Maker education by articulating knowledge construction with tangible experimentation and interdisciplinary collaboration. This finding was supported by the works identified in Table 2, where authors such as Martin (2015), Blikstein and Krannich (2013), and Hsu et al. (2017) lead the most cited publications for integrating the do it yourself philosophy with constructivist and STEAM frameworks. Likewise, Godhe et al. (2019) point out that the incorporation of Maker technologies requires a reconfiguration of the teacher's role, and Cohen et al. (2017) propose a formal framework for educational “makification.” Thus, the seminal texts shape the epistemic foundation of the field and demonstrate the need to advance toward integrative evaluative models that transcend the mere replication of experiences and promote longitudinal assessments of their real impact on teaching.

When analyzing recent research, it is evident that there is an evolution from manual creation toward expanded cognition mediated by artificial intelligence and design thinking. This finding is confirmed in Table 3, where the 2025 studies show the incorporation of emerging technologies, inclusion, and sustainability within the Maker discourse. Quintana-Ordorika et al. (2025) demonstrate that AI enhances teacher motivation and creativity, while Hosic et al. (2025) integrate ethical and intercultural dimensions into STEAM projects. Therefore, the convergence between AI, art, and design thinking redefines Maker education as a cognitive and socially responsible pedagogy, opening new paths for research on equity and teacher training that connect technological innovation with the development of emerging capabilities.

Regarding makerspaces, it was identified that they have evolved from physical digital fabrication laboratories into hybrid reflective learning ecosystems, where collaboration, self-assessment, and inclusion constitute their pedagogical core. Figure 3 illustrates this transition, showing the shift from material environments to socio-technical infrastructures with digital mediation and learning analytics. In addition, Figure 5 complements this interpretation by depicting the conceptual network in which maker and makerspaces are connected to nodes such as constructionism, learning, design thinking, STEM/STEAM, collaboration, and innovation, reinforcing their characterization as complex educational ecosystems rather than mere technical workshops. In this regard, early descriptions such as those by Hsu et al. (2017) define makerspaces as communities of practice centered on experimentation, whereas Bosch et al. (2025) redefine them as spaces for teacher self-reflection and iterative design. This conceptual evolution implies a profound reconfiguration of active learning toward sustainable models of educational innovation, requiring teacher training in emerging digital competencies with a gender perspective.

Moreover, the beneficiaries of makerspaces have shifted from traditional STEM populations to diverse communities that include women, cultural minorities, and neurodiverse learners. However, structural and cultural gaps persist that restrict women's participation in Maker environments, where technological biases and the lack of equity policies limit their leadership. It should be noted that since the 2010s, inequalities derived from the initial technocentric culture and the underrepresentation of women have been analyzed. In this regard, Martin (2015) and Blikstein and Krannich (2013) warned of this foundational bias, while Quintana-Ordorika et al. (2025) highlight the emergence of models that position women educators as designers and mediators of learning experiences.

Concerning the STEM skills promoted by makerspaces, these have evolved from programming and 3D design to self-regulation and empathy. Weng et al. (2022) emphasize the development of creativity and entrepreneurship, while Li et al. (2025) demonstrate the consolidation of interdisciplinary technological competencies. In the educational field, this means that makerspaces have ceased to be simple fabrication environments and have become laboratories for scientific citizenship and technological ethics, where STEM education is intertwined with social inclusion, gender equity, and continuous teacher development.

Conclusions

The systematic review on Maker education allows us to affirm that this field has evolved from an empirical practice based on experimentation toward a more complex form of education grounded in interdisciplinary frameworks and technological integration. The analysis of scientific production reveals theoretical maturity that consolidates Maker education as an approach to educational and social innovation, capable of articulating creativity, critical thinking, and STEM competencies in diverse contexts. A fundamental contribution of this study lies in the evolutionary conceptualization of makerspaces as hybrid ecosystems of reflective learning, where iterative design, self-assessment, and inclusion are integrated as structural components. This conceptual advancement redefines the boundaries of active learning, overcoming the initial technocentric vision to incorporate artificial intelligence, artistic creativity, and gender equity as essential dimensions of an education of making.

From the perspective of equity and inclusion, the results highlight that makerspaces have become spaces of empowerment for diverse communities, particularly women, neurodiverse students, and learners of different languages. This inclusive shift positions Maker education as a tool for social justice that contributes to closing structural gaps in STEM education. In the field of STEM skills, this study provides evidence that makerspaces generate transversal learning experiences that integrate technical, cognitive, and socio-emotional dimensions. The convergence of science, art, engineering, and design fosters creative problem-solving and self-reflection—essential components for sustainable innovation.

Although gender is mentioned throughout the text, a deeper conceptual clarification is necessary to understand its role within Maker education. From a theoretical standpoint, gender equity refers to the fair distribution of opportunities, resources, and participation conditions between women and men, recognizing the sociocultural determinants that historically restrict female access to STEM fields such as stereotypes about technical competence, limited early exposure to technological tools, and the persistence of male-dominated learning environments.

The results of this review show that, while recent studies incorporate inclusive frameworks and expand the range of beneficiaries, there is still limited empirical evidence on whether Maker education actively challenges or unintentionally reproduces gendered expectations in STEM. For example, although makerspaces promote collaboration, creativity, and hands-on experimentation, some research continues to document disparities in tool use, leadership roles within projects, and self-efficacy perceptions among women. This underscores the need to critically examine not only participation rates but also the cultural dynamics and pedagogical practices that shape gendered experiences within Maker environments, as well as to strengthen models that leverage design thinking, AI-mediated scaffolding, and reflective teaching to foster equitable learning conditions.

Among the study's limitations, it is acknowledged that, although the systematic review made it possible to identify global trends and patterns, it did not explore in depth the longitudinal impacts of Maker practices nor compare results across regions. Finally, future studies should be directed toward the creation of evaluative and longitudinal methodologies that analyze the real impact of Maker education on competency development and gender equity. It is recommended to promote collaborative research among universities, governments, and educational communities that integrates artificial intelligence, data analysis, and design thinking as axes of pedagogical innovation. Likewise, further exploration is suggested regarding the teacher's role as a designer of hybrid and reflective learning experiences, capable of mediating between technology and humanity.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CG-R: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. TT-B: Data curation. LB: Formal analysis, Visualization. RC-Q: Investigation, Funding acquisition. AP-S: Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Universidad Bolivariana del Ecuador and especially the WISE AI Research Group: Women in Smart Education: Complexity & AI Literacy Hub for their contributions to the development of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

An, B. D., Ulku, E. E., Bas, A., and Erdal, H. (2020). The role of the maker movement in engineering education: student views on key issues of makerspace environment. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 36, 1161–1169. Available online at: https://www.ijee.ie/contents/c360420.html

Balakrisnan V. Kamarudin N. Mar'of A. M. Hassan A. (2023). Maker-centred learning approach to craft STEM education in primary schools: a systematic literature review. ASM Sci. J. 18:1430. doi: 10.32802/asmscj.2023.1430

Barrett, A., Ke, F., Zhang, N., and Sokolikj, Z. (2025). Implementation fidelity of an evidence-centered maker education intervention in a virtual world for neurodiverse adolescents. Comput. Educ. X Real. 7:100106. doi: 10.1016/j.cexr.2025.100106

Blikstein, P., and Krannich, D. (2013). “The makers' movement and fablabs in education: experiences, technologies, and research,” in IDC ‘13: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, 613–616.

Bosch, N., Härkki, T., and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2025). Teachers as reflective learning experience designers: bringing design thinking into school-based design and maker education. Int. J. Child Comput. Interact. 43:100695. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcci.2024.100695

Cerrón-Salcedo, J., León Lucano, J., Hinostroza, A., Rubén Ríos Quispe, A., and Del Aguila Ramos, J. A. (2024). “Factors affecting the use of “Maker Route” E-learning management systems for the development of digital manufacturing skills in higher education-Engineering,” in Proceedings of the LACCEI international Multi-conference for Engineering, Education and Technology. Boca Raton, FL: LACCEI

Chen, P., Wang, R., and Ma, Y. (2025). Promoting junior high school students' creativity in maker education: the design thinking approach. Think Skills Creat. 56:101764. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2025.101764

Cheng, Y., Chen, C., and Chen, N. (2025). Adopting maker education: a comparative analysis of intentions between in-service and pre-service STEM teachers. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 10, 1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10763-025-10547-w

Chou, P. (2018). Skill development and knowledge acquisition cultivated by maker education: evidence from arduino-based educational robotics. Eurasia J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ. 14, 1–15. doi: 10.29333/ejmste/93483

Cohen, J., Jones, W. M., Smith, S., and Calandra, B. (2017). Makification: towards a framework for leveraging the maker movement in formal education. J. Educ. Multimedia Hypermedia 26, 217–229. Available online at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-54961-001

Cox, G. M. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the aims of education: makers, managers, or inforgs? Stud. Philos. Educ. 43, 15–30. doi: 10.1007/s11217-023-09907-2

Davies, S., and Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2025). Research on K-12 maker education in the early 2020s – a systematic literature review. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 35, 763–788. doi: 10.1007/s10798-024-09921-6

Feng, X., Zhang, Y., Tong, L., and Yu, H. (2024). A bibliometric analysis of domestic and international research on maker education in the post-epidemic era. Library Hi Tech. 42, 33–53. doi: 10.1108/LHT-04-2022-0187

Gahoonia, S. (2024). Makers, not users: inscriptions of design in the development of postdigital technology education. Postdigit. Sci. Educ. 6, 98–113. doi: 10.1007/s42438-023-00431-7

George-Reyes, C. E. (2022). Imbricación del pensamiento computacional y la alfabetización digital en la enseñanza. Modelación a partir de una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Revista Española de Documentación Científica 46:e345. doi: 10.3989/redc.2023.1.1922

Geser, G., Hollauf, E., Hornung-Prähauser, V., Schön, S., and Vloet, F. (2019). Makerspaces as social innovation and entrepreneurship learning environments: the DOIT learning program. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 10, 60–71. doi: 10.2478/dcse-2019-0018

Godhe, A-. L., Lilja, P., and Selwyn, N. (2019). Making sense of making: critical issues in the integration of maker education into schools. Technol. Pedag. Educ. 28, 317–328. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2019.1610040

Gratani, F., and Capolla, L. (2023). Maker education and semplexity. rethinking education to address emerging complexity. Form@re-Open J. per la formazione in rete 23, 101–111. doi: 10.36253/form-13643

Gu, J., and Yang, Q. (2023). Case studies of maker education in China. En Int. Technol. Educ. Stud. 19, 107–119. doi: 10.1163/9789004681910_008

Hosic, R., Abrori, F. M., Lavicza, Z., Kasti, H., Houghton, T., Ulbrich, E., et al. (2025). STEAM-integrated interfaith learning through maker education: a framework for innovative religious learning. Relig. Educ. 120, 239–258. doi: 10.1080/00344087.2025.2508569

Hsu, Y., Baldwin, S., and Ching, Y. (2017). Learning through making and maker education. TechTrends 61, 589–594. doi: 10.1007/s11528-017-0172-6

Hwang, Y. (2023). When makers meet the metaverse: effects of creating NFT metaverse exhibition in maker education. Comput. Educ. 194:104693. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104693

Irie, N. R., Hsu, Y., and Ching, Y. (2019). Makerspaces in diverse places: a comparative analysis of distinctive national discourses surrounding the maker movement and education in four countries. TechTrends 63, 397–407. doi: 10.1007/s11528-018-0355-9

Iwata, M., Pitkänen, K., Laru, J., and Mäkitalo, K. (2020). Exploring potentials and challenges to develop twenty-first century skills and computational thinking in K-12 maker education. Front. Educ. 5:87. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00087

Jang, S. (2024). Development of a maker education program based on designing contents with generative AI: TMSI model for the curriculum of visual communication design. Arch. Des. Res. 37, 387–440. doi: 10.15187/adr.2024.05.37.2.387

Jeng, Y., Lai, C., Huang, S., Chiu, P., and Zhong, H. (2020). To cultivate creativity and a maker mindset through an Internet-of-Things programming course. Front. Psychol. 11:1572. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01572

Jia, Y., Zhou, B., and Zheng, X. (2021). A Curriculum integrating STEAM and maker education promotes pupils' learning motivation, self-efficacy, and interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition. Front. Psychol. 12:725525. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.725525

Junior, E. L., Lopes Camargo, C. E., de Oliveira Alves, J. A., Maia, D. F., Bimestre, T. A., Moreira, M. D., et al. (2025). Systems thinking as a support tool in teaching electronics: an approach through a systematic literature review and proposal of a framework for integrating maker culture and IoT in technical education. Procedia Comput. Sci. 266, 778–788. doi: 10.1016/j.procs.2025.08.098

Kafri, R. (2025). ‘Your past prepares you for who you will become': reoccurring themes in the individual pasts of maker education teachers. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 31, 345–356. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2023.2265832

Kalogeropoulos, N., Walker, P., Hale, C., Hellgardt, K., MacEy, A., Shah, U. V., et al. (2020). Facilitating independent learning: student perspectives on the value of student-led maker spaces in engineering education. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 36, 1220–1233. Available online at: https://www.ijee.ie/contents/c360420.html

Kim, J., Seo, J. S., and Kim, K. (2022). Development of novel-engineering-based maker education instructional model. Educ. Inform. Technol. 27, 7327–7371. doi: 10.1007/s10639-021-10841-4

Kwon, H. (2023). Connecting maker education to secondary school technology education in Korea: a case of the technology teachers' learning community in Republic of Korea. Int. Technol. Educ. Stud. 19, 96–106. doi: 10.1163/9789004681910_007

Lege, R., Bonner, E., and Frazier, E. (2025). Empowering language learners: the intersection of maker education and CLIL. J. Immers. Content-Based Lang. Educ. doi: 10.1075/jicb.23037.leg

Li, C. (2016). Maker-based STEAM education with Scratch tools. World Transac. Eng. Technol. Educ. 14, 151–156. Available online at: https://www.wiete.com.au/journals/WTE&TE/Pages/Vol.14,%20No.1%20(2016)/25-Li-C.pdf

Li, J., Goei, S. L., van Joolingen, W., and Raijmakers, M. (2025). Shaping maker education through design thinking: a lesson study perspective. Think Skills Creat. 59:101957. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2025.101957

Liu, Y. (2023). An innovative talent training mechanism for maker education in colleges and universities based on the IPSO-BP-enabled technique. J. Innov. Knowl. 8:100424 . doi: 10.1016/j.jik.2023.100424

Lo, N. P. (2024). From theory to practice: unveiling the synergistic potential of design and maker education in advancing learning. SN Comput. Sci. 5:360. doi: 10.1007/s42979-024-02726-3

Lobato, P., Santos, I., Araújo, M., De Freitas Jorge, E., Filho, A., and Saba, H. (2023). Maker Culture: Dissemination of Knowledge and Development of Skills and Competencies for the 21st Century. London: Concilium.

Lord, G. (2025). “The maker movement in world language education,” in The Handbook of Research in World Language Instruction (England: Routledge), 505–514.

Lyon, E. G., Kochevar, R., and Gould, J. (2023). Making it in undergraduate STEM education: the role of a maker course in fostering STEM identities. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 45, 946–967. doi: 10.1080/09500693.2023.2179376

Martin, L. (2015). The promise of the maker movement for education. J. Precoll. Eng. Educ. Res. 5, 30–39. doi: 10.7771/2157-9288.1099

Mavri, A., Ioannou, A., and Kitsis, A. (2025). Designing assessmake21 for self-reflection in maker education: insights from a design case. Int. J. Human Comput. Interact.41, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2025.2482752

Mehto, V., and Kangas, K. (2023). Dynamic roles of materiality in maker education. Maker Educ. Meets Technol. Educ. 19, 149–164. doi: 10.1163/9789004681910_011

Niinimäki, N., Sormunen, K., Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P., Davies, S., and Kangas, K. (2025). Technological competence in formal education collaborative maker projects: an epistemic network analysis. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 41:e13114 . doi: 10.1111/jcal.13114

Ou, Q., and Chen, X. (2024). Investigation and analysis of maker education curriculum from the perspective of artificial intelligence. Sci. Rep. 14:52302 . doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-52302-1

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 88:105906. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906

Pan, A., and Chou, P. (2024). A qualitative analysis of student learning after the completion of maker education programs: influences on the choice of engineering majors. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 40, 295–302. doi: 10.54855/ijee.2024.40.295

Peppler, K., Keune, A., Thompson, N., and Saxena, P. (2022). Craftland is Mathland: mathematical insight and the generative role of fiber crafts in maker education. Front. Educ. 7:1029175. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1029175

Petersen, K., Feldt, R., Mujtaba, S., and Mattsson, M. (2008). “Systematic mapping studies in software engineering,” in Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering (Swinton, UK: British Computer Society), 68–77.

Pols, F., and Hut, R. (2023). Maker education in the applied physics bachelor programme at delft university of technology. Int. Technol. Educ. Stud. 19, 120–128. doi: 10.1163/9789004681910_009

Premyanov, N., Metta, J., Angelidou, M., Tsoniotis, N., Politis, C., Athanasiadou, E., et al. (2022). “Circular Makerspaces as entrepreneurship platforms for smart and sustainable cities,” in 2022 7th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech) (Piscataway, NJ: IEEE), 1–6.

Purg, P., Pranjić, K., and Gerbec, J. C. (2025). Toward a collaborative innovation paradigm: Maker culture, art thinking, and interdisciplinary education. Creat. Indus. J. 18, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/17510694.2025.2525648

Quintana-Ordorika, A., Camino-Esturo, E., Garay-Ruiz, U., and Portillo-Berasaluce, J. (2025). The impact of artificial intelligence on maker education: motivation and technology acceptance in teacher training. J. Educ. Elearn. Res. 19, 295–305. doi: 10.20448/jeelr.v12i2.6893

Reynaga-Peña, C. G., Aguilar-Mejía, J. R., Santillan-Rosas, I. M., Tamayo-Preval, D., Torres-Sánchez, P., Olais-Govea, J. M., et al. (2025). Engineering education for inclusion: developing transversal and disciplinary competencies with maker projects. Eur. J. Eng. Educ. 50, 1–10 doi: 10.1080/03043797.2025.2502470

Rosenheck, L., Lin, G. C., Nigam, R., Nori, P., and Kim, Y. J. (2021). Not all evidence is created equal: assessment artifacts in maker education. Inf. Learn. Sci. 12, 171–198. doi: 10.1108/ILS-08-2020-0205

Russo, R., Fuhrmann, T., Goya, A., and Blikstein, P. (2022). “Can schools fix the gender gap in STEM? A comparative study in the global south about gender participation in maker education,” in Proceedings of the 16th International Conference of the Learning Sciences—ICLS 2022, eds. C. Chinn, E. Tan, C. Chan and Y. Kali (Bloomington: International Society of the Learning Sciences), 2168–2169.

Saavedra Munar, L. S., González-Jiménez, D., Lopez-Sotelo, J. A., and Pradilla, J. (2025). Opportunities for Integrating Generative AI, Service-Learning and Maker Movement for Transformative Learning in Engineering Education (Montevideo, Uruguay: IEEE Engineering Education World Conference (EDUNINE)), 1–6.

Santos, P., Calvera-Isabal, M., Rodríguez, A., and El Aadmi, K. (2024). The impact of design thinking, maker education, and project-based learning on self-efficacy of engineering undergraduates. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 40, 851–862. Available online at: https://www.ijee.ie/contents/c400424.html

Schaber, F., Fakoussa, R., Redfern, C., Farrugia, H., and Wright, M. (2021). “Embedding changemaker skills and social innovation into design student learning,” in DS 110: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Engineering and Product Design Education (EandPDE 2021), VIA Design, VIA University in Herning, Denmark (Glasgow: The Design Society), 1–6.

Scharon, C. J., Phillips, A., and Jones-Davis, D. (2024). The mind of a maker: a learning framework for a continuum of K-12 invention education. Front. Educ. 9. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1352274

Shu, Y., and Huang, T. (2021). Identifying the potential roles of virtual reality and STEM in Maker education. J. Educ. Res. 114, 108–118. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2021.1887067

Stager, G. S. (2013). “Papert's prison fab lab: Implications for the maker movement and education design,” in IDC ‘13: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children (New York: Association for Computing Machinery), 487–490.

Sun, X. (2020). Exploration and practice of “Internet + Maker Education” University innovative entrepreneurship education model from the perspective of positive psychology. Front. Psychol. 11:891. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00891

Tabarés, R., and Boni, A. (2023). Maker culture and its potential for STEM education. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 33, 241–260. doi: 10.1007/s10798-021-09725-y

Tay, K. S., and Eng, J. L. (2024). Integrating maker education into the research project of undergraduate chemistry program: low-cost arduino-based 3D printed autotitrator. J. Chem. Educ. 101, 5430–5436. doi: 10.1021/acs.jchemed.4c00486

Tian, Q., Zhang, J., Tang, C., Wang, L., Fang, J., Zhang, Z., et al. (2020). Research topics and future trends on maker education in China based on bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Inform. Educ. Technol. 10, 135–139. doi: 10.18178/ijiet.2020.10.2.1352

Weiner, S., Lande, M., and Jordan, S. S. (2020). Designing (and) making teachers: Using design to investigate the impact of maker-based education training on pre-service STEM teachers. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 36, 702–711. Available online at: https://www.ijee.ie/contents/c360220.html

Weng, X., Chiu, T. K. F., and Tsang, C. C. (2022). Promoting student creativity and entrepreneurship through real-world problem-based maker education. Think Skills Creat. 45:101046. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2022.101046

Xu, W., Chen, J-. C., Lou, Y-. F., and Chen, H. (2024). Impacts of maker education-design thinking integration on knowledge, creative tendencies, and perceptions of the engineering profession. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 34, 75–107. doi: 10.1007/s10798-023-09810-4

Yang, Y. (2020). Exploration and practice of maker education mode in innovation and entrepreneurship education. Front. Psychol. 11:1626. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01626

Yang, Y. (2022). “Construction mechanism and path of innovative entrepreneurship and education practice platform based on maker education,” in Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Education and Training Technologies (New York: Association for Computing Machinery).

Yueh-Min, Y., Cheng, A., and Wu, T. (2022). Analysis of learning behavior of human posture recognition in maker education. Front. Psychol. 13:868487. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.868487

Keywords: higher education, maker, makerspaces, STEM, women

Citation: George-Reyes CE, Tapia-Bastidas T, Sandoval-Benitez LF, Caicedo-Quiroz R and Pinto-Santos AR (2025) Rethinking maker education: makerspaces, gender, and STEM skills in the era of inclusive educational intelligence. Front. Educ. 10:1729067. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1729067

Received: 20 October 2025; Revised: 17 November 2025;

Accepted: 18 November 2025; Published: 11 December 2025.

Edited by:

Patrick Johnson, University of Limerick, IrelandReviewed by:

Noelia Morales-Romo, University of Salamanca, SpainJan-René Schluchter, Ludwigsburg University of Education, Germany

Copyright © 2025 George-Reyes, Tapia-Bastidas, Sandoval-Benitez, Caicedo-Quiroz and Pinto-Santos. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlos Enrique George-Reyes, Y2VnZW9yZ2VyQHViZS5lZHUuZWM=

†ORCID: Tatiana Tapia-Bastidas orcid.org/0000-0001-9039-5517

Luisa Fernanda Sandoval-Benitez orcid.org/0009-0008-2007-1283

Rosangela Caicedo-Quiroz orcid.org/0000-0003-0737-9132

Alba Ruth Pinto-Santos orcid.org/0000-0001-8414-544X

Carlos Enrique George-Reyes

Carlos Enrique George-Reyes Tatiana Tapia-Bastidas1†

Tatiana Tapia-Bastidas1†