- 1Metallurgical and Materials Engineering Department, Colorado Center for Advanced Ceramics, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, United States

- 2Shared Instrumentation Facility, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, United States

- 3Mechanical Engineering Department, Colorado Fuel Cell Center, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, United States

Proton-conducting ceramic electrochemical devices (PCCs) show promise for sustainable energy conversion, yet key challenges remain. This perspective highlights critical areas for advancing PCC research. The field requires standardized protocols for fabrication, testing, and results reporting. Improved electrolyte sintering techniques and minimized nickel-induced defects are imperative for stable, high-performing cells. Addressing materials criticality is essential for commercialization. A deeper understanding of electrolyte grain boundary properties, positrode-electrolyte interface characteristics, and distribution of relaxation times analysis has great potential to accelerate progress. The promising application of PCCs in electrolysis mode remains understudied and merits increased research attention.

1 Introduction

Proton-conducting ceramic electrochemical devices (PCCs) are an emerging technology for energy conversion. These efficient, fuel-flexible systems (Duan et al., 2018) operate reversibly (Duan et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019), enabling both power generation from fuel and fuel production from electricity. This bidirectional capability positions PCCs as key enablers of a sustainable economy.

Despite key advances in PCCs, challenges with fabrication, reproducibility, cross-lab performance comparison, testing standardization, and mechanistic interpretation remain. This article maps vital pathways toward PCC commercialization. We share our perspectives on key areas of PCC development requiring improvement and/or further investigation, including:

1. Benchmarking: Establishing standards across the field. This standardization will facilitate meaningful inter-laboratory comparison of results and accelerate research progress.

2. Electrolyte sintering: Developing facile sintering methods that do not depend on liquid phase sintering. These methods will enable consistent, high-performing electrolytes, enhancing PCC power density.

3. Material criticality: Addressing criticality of PCC materials and components. Reducing reliance on critical materials enhances commercial feasibility.

4. Electrolyte grain boundary characteristics: Understanding the impact of processing. Optimization of grain boundary properties can significantly improve electrolyte conductivity.

5. Mechanical strength: Strengthening PCCs to increase robustness. Enhanced mechanical properties enable rapid thermal cycling and broader applications.

6. Positrode-electrolyte interface: Enhancing comprehension of this important junction. Understanding and optimizing this interface is important for reducing overall cell resistance.

7. Distribution of relaxation times (DRT) peak analysis: Increased analysis on the mechanisms that underlie DRT peaks at different conditions. DRT analysis enables deconvolution of resistances from underlying electrochemical phenomena, providing insights that can augment the speed of research.

8. Electrolysis: Electrolysis operation of PCCs warrants increased research attention. Green hydrogen production represents a significant application of PCCs.

2 Discussion

2.1 Benchmarking

Progress in the PCC field is rapid, with new electrode and electrolyte compositions being reported almost daily. With this significant increase in research findings, the need for cross-laboratory experimental reproducibility and objective performance comparisons is becoming crucially important. The PCC field presently follows a “champion” cell model, where one or a few high performing cells utilizing a novel material/architecture are compared to a baseline cell. This selective reporting coupled with small reported sample sizes leads to poor reproducibility across laboratories. Additionally, testing ceramic fuel cells at 400–800°C presents significant challenges, with high performance variability stemming from complex cell fabrication (Meisel et al., 2024a) and diverse testing setups and procedures. Thus, there is a need for standardized testing protocols.

A critical yet often overlooked aspect requiring standardization is cell “wiring,” which is how the cell is electronically connected to the test stand. While current collection can significantly impact ohmic resistance, thorough description is rarely provided. Further, the interconnection between the ceramic-based electrodes and the metallic wiring can be very technique oriented, lacking consistency across developers. Wiring methods range from contact paste with wires (Choi et al., 2018; Bian et al., 2022; Meisel et al., 2024b; Meisel et al., 2024a) or meshes (Duan et al., 2015; Park et al., 2022), compressed metal foams (An et al., 2018), compressed contact paste (Le et al., 2022; Herradon et al., 2022; Duan et al., 2019; Liang et al., 2022; Okuyama et al., 2023), contact to a metal mesh (Han et al., 2018), and spring-loaded metal foils (Huang et al., 2023a). Materials used include platinum, gold, silver, and nickel. The field would greatly benefit from establishment of consistent, straightforward protocols for optimal wiring methods to minimize ohmic contact resistance.

The negatrode reduction process similarly demands standardization as it can impact performance (Li et al., 2010; Haanappel et al., 2006), but often goes unreported. Depending on the reduction protocol, remarkably different Ni-metal microsctrutures can be achieved (e.g., highly porous and spongy vs. smooth and dense). Essential parameters include reduction temperature, fuel gas flow rates, gas composition, and heating rates. These parameters impact negatrode morphology, which impacts performance. Likewise, negatrode thickness can significantly influence cell performance, especially at higher current densities where mass-transport effects become important.

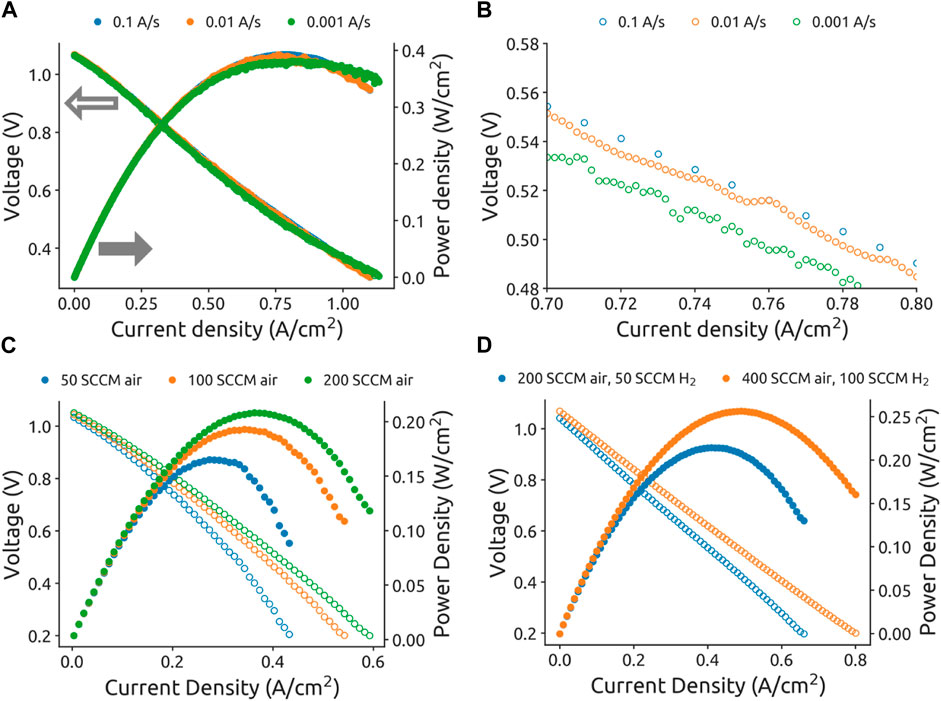

Testing protocols, particularly for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and polarization curves, also require consistent approaches. Figure 1A demonstrates how current scan rates can impact measured performance with a 3% difference in peak power density between fast (393 mW/

Figure 1. Fuel cell polarization curves taken at different conditions. (A) Full polarization curves with corresponding power curves at three different scan rates. (B) Magnified view of the IV-curve section. (C) Performance with different synthetic air (21%

Gas flow rates prove critically important to performance. Figure 1C shows that increasing air flow from 50 to 200 SCCM performance increased by 23%. The air utilization was 10, 6, and 3% for the 50, 100, and 200 SCCM conditions, respectively. Figure 1D demonstrates that doubling both the air and hydrogen flow can yield an 18% performance increase. The fuel utilization was 3% and 2% for the 50 SCCM and 100 SCCM fuel flow rate conditions, respectively. The large performance changes at low gas utilization conditions warrants the reporting of gas utilization with performance data. Furthermore, results acquired using pure

Benchmarking considerations should include a minimum active cell area requirement for literature reporting. Smaller areas can inflate performance due to disproportionate effects of active area measurement errors. For example, a ±500

To advance the field, we recommend establishing a third-party lab for performance validation, similar to photovoltaic certification (Reese et al., 2017). Additionally we recommend standard cell dimensions. This approach should be coupled with thorough reporting of key technical parameters and cell characteristics that impact performance, such as the electrolyte thickness to grain size ratio (Meisel et al., 2024a). Fortunately, benchmarking efforts are already underway in the solid-oxide fuel cell field (Auer et al., 2015; Bulfin et al., 2023; European Commission. Joint Research Centre, 2023), and can be used as a guide.

PCC development would greatly benefit from demonstration of repeatable results, rather than the champion-cell model. For example, we found a 67% peak power density variation (± one standard deviation of 93 mW/cm2) from a batch of 7 nominally identical cells tested in a single test station in our laboratory. This observation suggests that the apparent performance increases caused by new electrode materials or new cell fabrication procedures could in some cases be due simply to statistical cell-to-cell variability. Addressing these standardization and reproducibility needs and moving beyond the champion cell model will therefore greatly augment research precision and accelerate the commercialization potential of PCCs.

2.2 Electrolyte sintering

Forming thin, dense electrolytes with large grains is important for high-performing (Meisel et al., 2024a) and stable (Meisel et al., 2024b) PCC devices. The primary challenge lies in producing phase-pure, well-sintered electrolytes using low-cost precursor powders at reduced sintering temperatures while avoiding solid-state reactive sintering (SSRS) and minimizing reactions between the electrolyte and a predominantly nickel negatrode substrate.

The electrolyte, typically acceptor-doped (M)

SSRS enables dense, phase-pure BCZM formation from precursor oxides at lower temperatures through transition metal sintering aids (typically Ni) in a single combined phase-formation and sintering step (Tong et al., 2010a; Tong et al., 2010b; Tong et al., 2010c; Nikodemski et al., 2013). The process involves forming a transient liquid phase,

However, SSRS can impair performance through barium loss to the BMN phase in the negatrode (Huang et al., 2021a; Huang et al., 2023a; Deibert et al., 2022), electrolyte inhomogeneities from BMN phase breakdown (Deibert et al., 2022; Fang et al., 2015; Han et al., 2021b; Han et al., 2016), and incomplete BMN decomposition (Tong et al., 2010c; Han et al., 2020). All of these processes lower electrolyte conductivity. Additionally SSRS can lead to Ni segregation to grain boundaries (Huang et al., 2021a; Han et al., 2014). The Ni can form nanoparticles in the grain boundaries (Pan et al., 2016) that can crack the electrolyte upon re-oxidation. Furthermore, BMN formation itself has also been linked to electrolyte cracking (Kuroha et al., 2021).

Another key performance limiter in PCC electrolytes is the saturation of Ni from the negatrode during co-sintering. Higher Ni content in the lattice has been shown to decrease proton uptake (Huang et al., 2023a; Huang et al., 2021a; Han et al., 2021b) and bulk proton conductivity (Huang et al., 2023a; Han et al., 2018; Polfus et al., 2016; Han et al., 2014; Han et al., 2021b; Li et al., 2020; Nasani et al., 2017), while increasing the electronic conductivity of the electrolyte (Han et al., 2018; Han et al., 2021b; Kuroha et al., 2021; Kuroha et al., 2020). Ni can occupy interstitial sites (Han et al., 2014; Polfus et al., 2016; Dayaghi et al., 2023) or, less commonly, B-sites (Dayaghi et al., 2023). This can create barium vacancies and/or reduce the effective acceptor dopant concentration (Huang et al., 2021a; Huang et al., 2020; Dayaghi et al., 2023; Han et al., 2021b). Lower effective acceptor dopant concentration reduces proton uptake, leading to decreased proton conductivity. Additionally, barium vacancies lower proton mobility (Yamazaki et al., 2010), acting as proton traps (Polfus et al., 2016) and increasing the concentration of non-hydrated oxygen vacancies. More oxygen vacancies can distort the lattice and negatively impact proton mobility.

Thus, fabrication techniques need to be developed to produce phase-pure, well-sintered electrolytes using low-cost precursor powders. These methods should ideally occur at lower temperatures, avoid SSRS, and minimize reactions between the electrolyte and a predominantly nickel-oxide negatrode substrate.

SSRS can be suppressed using acceptor dopants with atomic radii

Decreasing the concentration of the common acceptor dopant Y to 12% or below can suppress BYN formation and SSRS (Li et al., 2023; Han et al., 2021b; Ueno et al., 2019). However, this reduction in acceptor dopant concentration lowers proton uptake and mobility in the electrolyte. Co-doping with Y below 12% and one of the 3+ elements smaller than Tm is a viable strategy, as employed in

Addressing BMN formation and SSRS does not resolve the negative effects of Ni saturation in the electrolyte. In order to reduce Ni saturation of the electrolyte, lower temperature or rapid sintering techniques must be developed. These techniques must form a dense, large-grained electrolyte that is crack and defect free. Cold sintering (Kindelmann et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2016), microwave sintering (Rybakov et al., 2013; Hagy et al., 2024), flash sintering (Cologna et al., 2010; Guillon et al., 2023; Rheinheimer et al., 2019), blacklight sintering (Porz et al., 2022a; Porz et al., 2022b), and carbothermal shock (Yao et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2022) could enable the formation of co-sintered materials with minimal Ni diffusion into the electrolyte.

In summary, co-sintering the negatrode and electrolyte requires careful materials selection and an appropriate sintering method to prevent transient BMN phase formation and mitigate Ni diffusion into the electrolyte. Conventional sintering methods necessitate reducing Y concentration below 12 mol% and co-doping with expensive alternatives. However, promising rapid sintering techniques may enable co-sintering at lower temperatures, potentially mitigating both Ni diffusion and BMN formation.

2.3 Material criticality

Critical materials are those valuable to society yet vulnerable to supply disruptions (IEA, 2024, Bleicher et al., 2020; Ku et al., 2024). Factors influencing criticality include future supply and technological demand, geopolitical risks of suppliers and refiners, geological and geographical distribution, vulnerability to disruptions, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations, and climate risks.

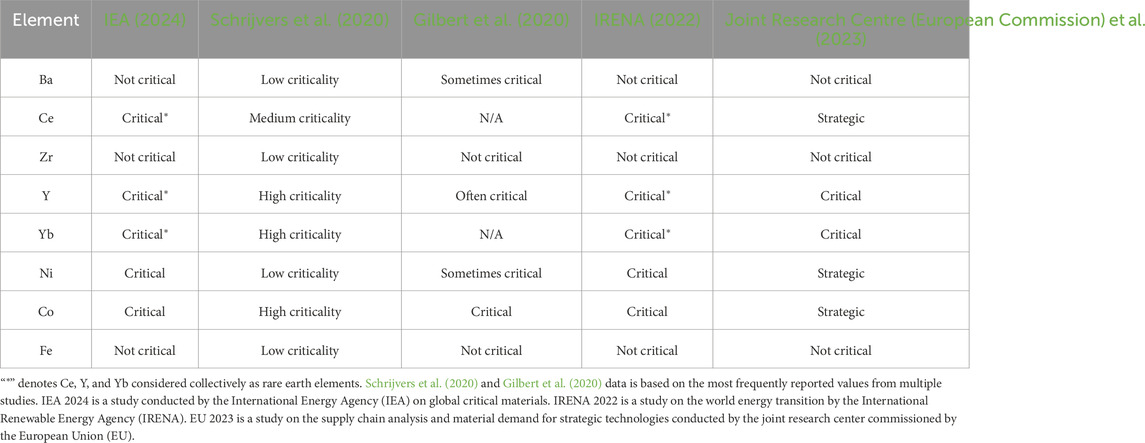

For PCCs, criticality considerations are consequential due to their reliance on rare earth elements in the electrolyte and transition metals in the electrodes. As shown in Table 1, Ba, Zr, and Fe consistently show low criticality. Rare earth elements (Ce, Y, Yb) and transition metals (Ni, Co) are generally classified as critical materials. Therefore, Ba, Zr, and Fe should be prioritized for use in PCC devices.

The criticality of rare earth elements Ce, Y, and Yb varies across studies. When grouped together (denoted by “*”), all rare earths are deemed critical. However, studies that assess individual elements often show Ce as less critical than Y or Yb, likely due to its higher relative abundance in earth’s crust (McLennan, 2001; Haynes, 2016), and its relatively higher abundance in many rare-earth ores. Both Ni and Co should be minimized in PCCs, though some Ni use may be unavoidable. As discussed in Section 2, the ideal acceptor dopants are rare earth elements, making some use of critical materials inevitable in PCC devices. Strategies should be developed to minimize rare earth usage without compromising performance.

2.3.1 Strategies to mitigate PCC criticality

The negatrode presents significant opportunities for reducing critical materials. While traditionally hundreds of microns thick (Dubois et al., 2017), the electrochemically active zone is likely only 5 to 50

Iron oxide, being much less critical than nickel oxide, could be a potential substitute. While Fe hinders sintering of BCZY-based materials when doped into the electrolyte at 4–5 mol% (Babilo and Haile, 2005; Nikodemski et al., 2013), it shows beneficial effects at

One additional strategy is to use less critical materials in the negatrode bulk. Based on Table 1, BZY10 is a better option than BCZYYb. A bi-layered negatrode design could incorporate a 10–50

Despite their name, rare earth elements are not scarce (Kim and Jariwala, 2023), with Ce being more abundant than Cu in the earth’s crust (McLennan, 2001; Haynes, 2016). Isolation of specific rare earth remains challenging due to dispersed deposits and similar chemical properties (Fray, 2000). Using concentrated, unseparated mixtures of 3+ rare earth elements in electrolytes could reduce cost and BMN formation while maintaining performance.

The positrode, though a small fraction of cell mass, significantly impacts criticality through cobalt usage. Cobalt enhances oxygen reduction reaction kinetics due to near-optimal transition metal and reaction intermediate electron orbital alignment and due to relatively weak M-O bonds that facilitate oxygen ion mobility (Lee and Manthiram, 2005). It also enables electronic conductivity through its facile oxidation state changes (Papac et al., 2021). However, cobalt can also reduce material stability, lower hydration ability (Zohourian et al., 2018), and undesirably increase the material’s coefficient of thermal expansion (Papac et al., 2021). Promising cobalt-free alternatives include

2.4 Electrolyte grain boundary characteristics

Grain boundaries in the electrolyte significantly impair performance through space charge defects and disorder that reduce conductivity (Kreuer, 2003; Kjølseth et al., 2010; Shirpour et al., 2012) and increase the activation energy for proton hopping (Iguchi et al., 2007; Babilo and Haile, 2005; Ricote et al., 2014Ricote et al., 2014). Ideal electrolytes would have a bamboo structure with grain sizes exceeding electrolyte thickness. This structure minimizes the number of resistive grain boundaries that protons must cross. Larger grains diminish the strength of ceramics (Rahaman, 2003), though grain size becomes less critical in the electrolyte of negatrode-supported PCCs where the negatrode provides the primary mechanical support.

The fabrication of thin, bamboo-structured electrolytes without defects remains a significant challenge (Meisel et al., 2024b). This is particularly evident when working with high-zirconium BCZM compositions. Understanding how different processing techniques and material sets affect grain boundary characteristics is key for engineering less-resistive grain boundaries.

While grain boundary resistivity can be studied via high-frequency polarization resistance at low temperatures (

A comprehensive, data-driven study (Meisel et al., 2025; Meisel et al., 2024a; Zhai et al., 2022), could determine how processing conditions and BCZM compositions affect grain boundary chemistry and electrostatic potential. This would potentially enable optimization of grain boundary characteristics for maximum cell performance. Current limitations include high costs and low throughput of advanced characterization techniques such as APT and TEM, along with uncertainty about required sampling sizes for accurate grain boundary property assessment across cells.

Electrolyte grain boundaries will likely plague PCC performance for the foreseeable future. Thus, understanding how to engineer more favorable grain boundaries is vital for improving future performance and repeatability.

2.5 Mechanical strength

BCZY-based materials, which are essential for PCCs, exhibit poor mechanical properties (Pirou et al., 2022), particularly after hydrogen exposure (Mercadelli et al., 2022). Enhanced mechanical strength enables the rapid thermal cycling of cells which greatly expands the potential applications of PCCs. Since the NiO-BCZY negatrode serves as the cell’s primary mechanical support, strengthening this layer is crucial for overall cell integrity. Further, PCCs are multi-layered systems, so coefficient of thermal expansion matching between layers is crucial for thermal cycle-ability.

Metal supports offer a promising solution for the negatrode, as discussed in Section 3. Metals provide superior toughness and resistance to brittle failure compared to ceramics. These properties significantly enhance the cell’s durability and thermal cycling capabilities (Matus et al., 2005). Additionally, reduction of the negatrode immediately after fabrication (NiO ceramic to Ni metal) has been shown to increase fracture toughness (Pirou et al., 2022).

Additionally, methods could be undertaken to increase the strength of the ceramic phase in the negatrode. Combining BCZY with

Modifying cell architecture and morphology offers another approach to enhance mechanical robustness. Tubular geometries provide superior mechanical strength and thermal cycling capability compared to planar cells (Bujalski et al., 2007). While tubular yttria-stabilized zirconia solid-oxide cells have demonstrated exceptional thermal cycling stability (Bujalski et al., 2007; Kendall et al., 1994; Kendall et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2019), this has not yet been achieved in PCCs. Additionally, reducing grain size can enhance mechanical properties, as ceramics with finer grains exhibit greater strength (Rahaman, 2003). Thus, fabricating negatrodes with smaller grains and post-sintered particle sizes particles could improve overall cell robustness.

2.6 Positrode-electrolyte interface

The positrode-electrolyte interface is likely a significant source of cell resistance, as it is a critical junction for proton transfer. Various studies have shown that tailoring this interface can greatly enhance cell performance. Effective strategies include both additive approaches, such as incorporating positrode functional layers (Choi et al., 2021; Akimoto et al., 2022; Choi et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2021; Shimada et al., 2019; Shimada et al., 2021a; Shimada et al., 2021b), and reductive methods like acid etching the electrolyte prior to positrode application (Bian et al., 2022). Understanding and tailoring the properties of this nano-scale juncture is pivotal for developing future high-performing PCCs.

The resistive impact of this interface can be approximated by plotting the dependence of cell ohmic resistance on electrolyte thickness. Ideally, this relationship is linear, with no resistance found when extrapolating to zero electrolyte thickness. However, this extrapolation yields a non-zero resistance in practice, generally attributable to the positrode-electrolyte interface (although ohmic resistance from the electrodes can also contribute). Akimoto et al. demonstrated that adding a positrode functional layer (PFL) reduced the

Choi et al. (2018) and Bian et al. (2022) point out that the electrolyte conductivity of negatrode-supported PCCs reported in literature is generally much lower than the intrinsic electrolyte conductivity. While Ni saturation in the electrolyte likely contributes, some of this reduction again likely stems from positrode-electrolyte interface resistance.

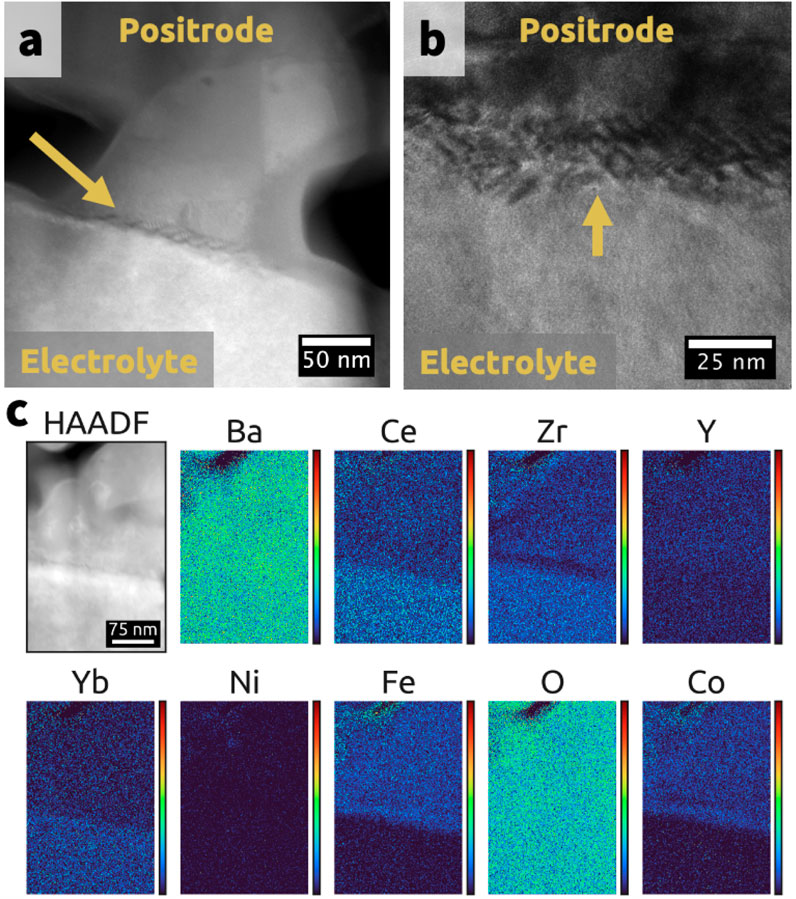

Similar to grain boundaries, the nanoscale disorder at the positrode-electrolyte interface likely impedes proton motion (Bian et al., 2022). The disorder, shown in Figures 2A, B, is evident in the highly non-uniform interfacial zone contrast. This disorder likely leads to space-charge layers and distorted proton transport.

Figure 2. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the positrode-electrolyte interface. (A) High-angle annular dark field (HAADF) image. (B) Bright-field image taken at a different spot on the cell at a different magnification. The electrolyte (bottom) is

Elemental segregation at the interface may also contribute to the space charge layer characteristics. This elemental segregation, shown in Figure 2C for elements Zr, Fe, and Co, likely impairs performance. The extent and nature of segregation are probably influenced by the initial electrolyte surface composition, positrode composition, and positrode sintering parameters.

Investigating the impact of processing parameters and material sets on the positrode-electrolyte interface would be valuable. Quantifying interface disorder thickness and space charge characteristics could provide measurable metrics to study. A machine learning approach, as found in (Meisel et al., 2025), could analyze these metrics across numerous cells, revealing how various material sets and processing parameters influence the interface. Unfortunately, much like for grain boundaries, the characterization techniques (APT/TEM) needed to quantify the space charge and disorder thickness of the positrode-electrolyte interface are expensive and low-throughput.

2.7 Distribution of relaxation times peak analysis

Presently, there is little agreement or clarity regarding the kinetic mechanism(s) and/or likely rate-determining steps (RDS) associated with the oxygen reduction and evolution reactions in PCCs. Recent advancements in impedance spectroscopy analysis, and specifically the rise of the distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis technique, may provide opportunities to clarify PCC electrochemical behavior. Furthermore, analyzing DRT spectra from diverse material sets can help to identify the most resistive processes, guiding targeted improvements in PCC design.

The DRT is a powerful tool for analyzing electrochemical signals, enabling enhanced process deconvolution without an a priori model (Huang et al., 2021b; Ivers-Tiffée and Weber, 2017; Huang et al., 2023b). DRT-based techniques excel at separating and quantifying losses from specific electrochemical processes in cells. However, a major challenge in the proton-conducting ceramics (PCC) field is identifying which DRT peak corresponds to which cell-level phenomenon. This task is complicated by peak overlap and shifts due to varying operating conditions (temperature, applied bias, pressure, and gas environment). Despite some attempts to characterize DRT response (Huang et al., 2024; Meisel et al., 2024b; Sumi et al., 2021; Herradon et al., 2022; Akimoto et al., 2022; Shimada et al., 2024; Hong et al., 2020; Osinkin, 2022), extensive systematic studies on PCC devices encompassing various material sets and operating conditions are needed to clarify the underlying processes distinguished by DRT.

To associate a specific DRT peak with a specific electrochemical process, several key parameters must be examined. The area under the curve of a DRT peak represents the resistance. The location of a DRT peak, determined by the center of the peak, gives the characteristic time constant

Ideally, DRT peak changes should be analyzed across various PCC-based electrochemical pressurization operating conditions, including temperature, pressure,

DRT inversion is an ill-posed problem, with multiple probable solutions for fitting any given EIS data set (Huang et al., 2021b; Ivers-Tiffée and Weber, 2017). Sourcing multiple related spectra increases the accuracy of the generated DRT spectra. This enhanced accuracy enables better deconvolution of overlapping signals. As a result, calculations of DRT peak resistances and time constants become more precise and reliable. Thus, to better understand and distinguish between multiple underlying electrochemical mechanisms, numerous DRT spectra need to be collected across a wide range of conditions and fit as one dataset.

These time-intensive experiments can be accelerated through a hybrid DRT approach as described in Huang et al. (2024). Hybrid-DRT accelerates data acquisition by 1–2 orders of magnitude, making extensive DRT peak analysis feasible. The hybrid-DRT package, developed by Huang et al. (2024), also includes tools for acquiring and plotting the DRT response as a function of applied bias, resulting in a 2-dimensional relaxation surface known as a “polarization map.” These polarization maps, taken under different operating conditions or with diverse cell material sets, enable multi-dimensional analysis of the DRT response, and hence cell electrochemistry.

Understanding the correlation between DRT peaks and electrochemical phenomena under specific operating conditions is vital for optimizing PCC technology. Analyzing DRT spectra from diverse material sets and operating conditions can identify the most resistive processes, guiding targeted improvements in PCC design.

2.8 Electrolysis

Hydrogen demand, driven by grid-scale storage systems, industrial decarbonization, and chemical feedstocks, is projected to increase from 95 Mt in 2022 to over 150 Mt by 2030 (Author Anonymous, 2023; Pivovar et al., 2018). Currently, most hydrogen comes from steam-methane reforming (“gray hydrogen,” 0.8–2 $/kg), with less than 1% from low-emission methods (Author Anonymous, 2023; Longden et al., 2022). The transition to “green hydrogen” via renewable-powered electrolysis (2.5–8 $/kg) requires technological advancement to become economically viable (Longden et al., 2022; Ajanovic et al., 2022).

The direction of chemical species transport in PCCs during electrolysis cell operation offers two key benefits. First,

Mirroring recent governmental initiatives on electrolysis R&D, there is a need for increased focus on protonic-ceramic electrolysis. While many papers in the PCC field report fuel cell peak power densities, fewer report electrolysis cell performance. Additionally, most EIS data is presented at OCV. While valuable, EIS at bias during electrolysis operation would provide a clearer picture of cell losses under real-world conditions. However, EIS under electrolysis bias generally results in low-frequency inductance loops (particularly at higher current densities) (Meisel et al., 2024b), which complicates the analysis of electrolysis-mode EIS data.

Water splitting via electrolysis inherently requires energy, costing at a minimum 32–33 kWh/kg of hydrogen produced (based on the lower-heating value) (Badgett et al., 2022). For low-temperature polymer electrolyte membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, electricity costs are the greatest contributor to water electrolysis expenses (Badgett et al., 2022). High-temperature systems like solid-oxide electrolysis cells (SOECs) and PCCs can produce hydrogen more efficiently than low-temperature systems. This increased efficiency is attributed to the higher operating temperature, and lower overpotentials of PCCs and SOECs compared to PEMs (Duan et al., 2019) and thus represents a compelling advantage should cost and durability challenges be overcome.

Hydrogen will serve as a key component of a sustainable future through chemical feedstocks, industrial decarbonization, and grid-scale energy storage. PCCs can fulfill a niche role in a sustainable economy due to their ability to continuously and efficiently generate pure, dry, electrochemically pressurizable hydrogen.

3 Conclusion

Standardizing aspects of cell fabrication, testing protocols, and results reporting will enable reproducibility and cross-laboratory comparisons. Novel electrolyte compositions and rapid sintering methods are needed to achieve phase-pure, stable, and highly conductive electrolytes. Fabricating PCCs with less rare earth elements, nickel, and cobalt is key for commercialization potential. Understanding how to form more conductive electrolyte grain boundaries and positrode-electrolyte interfaces can greatly enhance performance. Correlating distribution of relaxation times peaks with electrochemical mechanisms across operating conditions will augment research progress. PCCs show great promise for generating green hydrogen.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

CM: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. Y-DK: Data curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. DD: Investigation, Visualization, Writing–review and editing. RO’H: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. NS: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. CM was supported by the U.S. Department of Education under a Graduate Assistance in Areas of National Need (GAANN) Fellowship (Grant #P200A210134). RO’H and Y-DK gratefully acknowledge support from the US Army Research Office under grant number W911NF-22-1-0273.

Acknowledgments

Some of the work was performed in following core facility, which is a part of Colorado School of Mines’ Shared Instrumentation Facility RRID:SCR_022048.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Anthropic Claude AI were used in part to edit this manuscript. After using the generative AI tools, the authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdalla, A. M., Hossain, S., Nisfindy, O. B., Azad, A. T., Dawood, M., and Azad, A. K. (2018). Hydrogen production, storage, transportation and key challenges with applications: a review. Energy Convers. Manag. 165, 602–627. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2018.03.088

Ajanovic, A., Sayer, M., and Haas, R. (2022). The economics and the environmental benignity of different colors of hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 47 (57), 24136–24154. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.02.094

Akimoto, K., Wang, N., Tang, C., Shuto, K., Jeong, S., Kitano, S., et al. (2022). Functionality of the cathode–electrolyte interlayer in protonic solid oxide fuel cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 12227–12238. doi:10.1021/acsaem.2c01712

An, H., Lee, H.-W., Kim, B.-K., Son, J.-W., Yoon, K. J., Kim, H., et al. (2018). A 5 × 5 cm2 protonic ceramic fuel cell with a power density of 1.3 W cm2 at 600°C. Nat. Energy 3 (10), 870–875. doi:10.1038/s41560-018-0230-0

Auer, C., Lang, M., Couturier, K., Nielsen, E. R., McPhail, S. J., Tsotridis, G., et al. (2015). Solid oxide cell and stack testing, safety and quality assurance (SOCTESQA). ECS Trans. 68 (1), 1897–1905. doi:10.1149/06801.1897ecst

Author Anonymous (2023). Global hydrogen review 2023, tech. Rep. Paris: International Energy Agency IEA.

Azad, A. K., Savaniu, C., Tao, S., Duval, S., Holtappels, P., Ibberson, R. M., et al. (2008). Structural origins of the differing grain conductivity values in BaZr0.9Y0.1O2.95 and indication of novel approach to counter defect association. J. Mater. Chem. 18 (29), 3414–3418. doi:10.1039/b806190d

Babilo, P., and Haile, S. M. (2005). Enhanced sintering of yttrium-doped barium zirconate by addition of ZnO. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 88 (9), 2362–2368. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2005.00449.x

Babilo, P., Uda, T., and Haile, S. M. (2007). Processing of yttrium-doped barium zirconate for high proton conductivity. J. Mater. Res. 22 (5), 1322–1330. doi:10.1557/jmr.2007.0163

Badgett, A., Ruth, M., and Pivovar, B. (2022). “Chapter 10 - economic considerations for hydrogen production with a focus on polymer electrolyte membrane electrolysis,” in Electrochemical power sources: fundamentals, systems, and applications. Editors T. Smolinka, and J. Garche (Elsevier), 327–364. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819424-9.00005-7

Barthelemy, H., Weber, M., and Barbier, F. (2017). Hydrogen storage: recent improvements and industrial perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42 (11), 7254–7262. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.03.178

Bian, W., Wu, W., Wang, B., Tang, W., Zhou, M., Jin, C., et al. (2022). Revitalizing interface in protonic ceramic cells by acid etch. Nature 604 (7906), 479–485. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-04457-y

Bleicher, A., and Pehlken, A. (2020). “Chapter 1 - the material basis of energy transitions—an introduction,” in The material basis of energy transitions. Editors A. Bleicher, and A. Pehlken (Academic Press), 1–9. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819534-5.00001-5

Braun, A., Ovalle, A., Pomjakushin, V., Cervellino, A., Erat, S., Stolte, W. C., et al. (2009). Yttrium and hydrogen superstructure and correlation of lattice expansion and proton conductivity in the BaZr0.9Y0.1O2.95 proton conductor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95 (22), 224103. doi:10.1063/1.3268454

Bu, J., Jönsson, P. G., and Zhao, Z. (2014). Ionic conductivity of dense BaZr0.5Ce0.3Ln0.2O3-δ (Ln = Y, Sm, Gd, Dy) electrolytes. J. Power Sources 272, 786–793. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.09.056

Bujalski, W., Dikwal, C. M., and Kendall, K. (2007). Cycling of three solid oxide fuel cell types. J. Power Sources 171 (1), 96–100. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.01.029

Bulfin, B., Carmo, M., Van de Krol, R., Mougin, J., Ayers, K., Gross, K. J., et al. (2023). Editorial: advanced water splitting technologies development: best practices and protocols. Front. Energy Res. 11. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2023.1149688

Cai, Q., Adjiman, C. S., and Brandon, N. P. (2011). Investigation of the active thickness of solid oxide fuel cell electrodes using a 3D microstructure model. Electrochimica Acta 56 (28), 10809–10819. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2011.06.105

Choi, M., Kim, D., Lee, T. K., Lee, J., Yoo, H. S., and Lee, W. (2024). Interface engineering to operate reversible protonic ceramic electrochemical cells below 500°C. Adv. Energy Mater. 15, 2400124doi. doi:10.1002/aenm.202400124

Choi, M., Paik, J., Kim, D., Woo, D., Lee, J., Kim, S. J., et al. (2021). Exceptionally high performance of protonic ceramic fuel cells with stoichiometric electrolytes. Energy and Environ. Sci. 14 (12), 6476–6483. doi:10.1039/D1EE01497H

Choi, S., Davenport, T. C., and Haile, S. M. (2019). Protonic ceramic electrochemical cells for hydrogen production and electricity generation: exceptional reversibility, stability, and demonstrated faradaic efficiency. Energy and Environ. Sci. 12 (1), 206–215. doi:10.1039/C8EE02865F

Choi, S., Kucharczyk, C. J., Liang, Y., Zhang, X., Takeuchi, I., Ji, H.-I., et al. (2018). Exceptional power density and stability at intermediate temperatures in protonic ceramic fuel cells. Nat. Energy 3 (3), 202–210. doi:10.1038/s41560-017-0085-9

Clark, D. R., Zhu, H., Diercks, D. R., Ricote, S., Kee, R. J., Almansoori, A., et al. (2016). Probing grain-boundary chemistry and electronic structure in proton-conducting oxides by atom probe tomography. Nano Lett. 16 (11), 6924–6930. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02918

Cologna, M., Rashkova, B., and Raj, R. (2010). Flash sintering of nanograin zirconia in <5 s at 850°C. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 93 (11), 3556–3559. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2010.04089.x

Dayaghi, A. M., Polfus, J. M., Strandbakke, R., Pokle, A., Almar, L., Escolástico, S., et al. (2023). Effects of sintering additives on defect chemistry and hydration of BaZr0.4Ce0.4(Y,Yb)0.2O3-δ proton conducting electrolytes. Solid State Ionics 401, 116355. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2023.116355

Deibert, W., Ivanova, M. E., Huang, Y., Merkle, R., Maier, J., and Meulenberg, W. A. (2022). Fabrication of multi-layered structures for proton conducting ceramic cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 10 (5), 2362–2373. doi:10.1039/D1TA05240C

Demir, M. E., and Dincer, I. (2018). Cost assessment and evaluation of various hydrogen delivery scenarios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 43 (22), 10420–10430. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.08.002

Dogdibegovic, E., Wang, R., Lau, G. Y., Karimaghaloo, A., Lee, M. H., and Tucker, M. C. (2019). Progress in durability of metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells with infiltrated electrodes. J. Power Sources 437, 226935. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.226935

Duan, C., Huang, J., Sullivan, N., and O’Hayre, R. (2020). Proton-conducting oxides for energy conversion and storage. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7 (1), 011314. doi:10.1063/1.5135319

Duan, C., Kee, R., Zhu, H., Sullivan, N., Zhu, L., Bian, L., et al. (2019). Highly efficient reversible protonic ceramic electrochemical cells for power generation and fuel production. Nat. Energy 4 (3), 230–240. doi:10.1038/s41560-019-0333-2

Duan, C., Kee, R. J., Zhu, H., Karakaya, C., Chen, Y., Ricote, S., et al. (2018). Highly durable, coking and sulfur tolerant, fuel-flexible protonic ceramic fuel cells. Nature 557 (7704), 217–222. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0082-6

Duan, C., Tong, J., Shang, M., Nikodemski, S., Sanders, M., Ricote, S., et al. (2015). Readily processed protonic ceramic fuel cells with high performance at low temperatures. Science 349 (6254), 1321–1326. doi:10.1126/science.aab3987

Dubois, A., Ricote, S., and Braun, R. J. (2017). Benchmarking the expected stack manufacturing cost of next generation, intermediate-temperature protonic ceramic fuel cells with solid oxide fuel cell technology. J. Power Sources 369, 65–77. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.09.024

European Commission. Joint Research Centre (2023). EU harmonised testing protocols for high-temperature steam electrolysis. Office, LU: Publications.

Fan, W., Ren, Z., Sun, Z., Yao, X., Yildiz, B., and Li, J. (2022). Synthesizing functional ceramic powders for solid oxide cells in minutes through thermal shock. ACS Energy Lett. 7 (3), 1223–1229. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.1c02630

Fang, S., Wang, S., Brinkman, K. S., Su, Q., Wang, H., and Chen, F. (2015). Relationship between fabrication method and chemical stability of Ni–BaZr0.8Y0.2O3-δ membrane. J. Power Sources 278, 614–622. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.12.108

Fray, D. J. (2000). Separating rare earth elements. Science 289 (5488), 2295–2296. doi:10.1126/science.289.5488.2295

Gilbert, P. R. (2020). “Chapter 6 - making critical materials valuable: decarbonization, investment, and “political risk”,” in The material basis of energy transitions. Editors A. Bleicher, and A. Pehlken (Academic Press), 91–108. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819534-5.00006-4

Guillon, O., Rheinheimer, W., and Bram, M. (2023). A perspective on emerging and future sintering technologies of ceramic materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 25 (18), 2201870. doi:10.1002/adem.202201870

Guo, J., Guo, H., Baker, A. L., Lanagan, M. T., Kupp, E. R., Messing, G. L., et al. (2016). Cold sintering: a paradigm shift for processing and integration of ceramics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (38), 11457–11461. doi:10.1002/anie.201605443

Guo, Y., Ran, R., Shao, Z., and Liu, S. (2011). Effect of Ba nonstoichiometry on the phase structure, sintering, electrical conductivity and phase stability of Ba1±xCe0.4Zr0.4Y0.2O3-δ (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.20) proton conductors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 36 (14), 8450–8460. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.04.037

Haanappel, V. A. C., Mai, A., and Mertens, J. (2006). Electrode activation of anode-supported SOFCs with LSM- or LSCF-type cathodes. Solid State Ionics 177 (19), 2033–2037. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2005.12.038

Hagy, L. S., Ramos, K., Gelfuso, M. V., Chinelatto, A. L., and Chinelatto, A. S. A. (2024). Impact of microwave sintering and NiO additive on the densification and conductivity of BaCe0.2Zr0.7Y0.1O3-δ electrolyte for protonic ceramic fuel cell. Ceram. Int. 50, 40226–40236. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2024.06.410

Han, D., Jiang, L., and Zhong, P. (2021b). Improving phase compatibility between doped BaZrO3 and NiO in protonic ceramic cells via tuning composition and dopant. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46 (12), 8767–8777. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.12.075

Han, D., Kuramitsu, A., Onishi, T., Noda, Y., Majima, M., and Uda, T. (2020). Fabrication of protonic ceramic fuel cells via infiltration with Ni nanoparticles: a new strategy to suppress NiO diffusion and increase open circuit voltage. Solid State Ionics 345, 115189. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2019.115189

Han, D., Liu, X., Bjørheim, T. S., and Uda, T. (2021a). Yttrium-doped barium zirconate-cerate solid solution as proton conducting electrolyte: why higher cerium concentration leads to better performance for fuel cells and electrolysis cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (8), 2003149. doi:10.1002/aenm.202003149

Han, D., Otani, Y., Noda, Y., Onishi, T., Majima, M., and Uda, T. (2016). Strategy to improve phase compatibility between proton conductive BaZr0.8Y0.2O3-δ and nickel oxide. RSC Adv. 6 (23), 19288–19297. doi:10.1039/C5RA26947D

Han, D., Shinoda, K., Tsukimoto, S., Takeuchi, H., Hiraiwa, C., Majima, M., et al. (2014). Origins of structural and electrochemical influence on Y-doped BaZrO3 heat-treated with NiO additive. J. Mater. Chem. A 2 (31), 12552–12560. doi:10.1039/C4TA01689K

Han, D., Uemura, S., Hiraiwa, C., Majima, M., and Uda, T. (2018). Detrimental effect of sintering additives on conducting ceramics: yttrium-doped barium zirconate. ChemSusChem 11 (23), 4102–4113. doi:10.1002/cssc.201801837

Harkins, P., MacKenzie, M., Craven, A. J., and McComb, D. W. (2008). Quantitative electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) analyses of lead zirconate titanate. Micron 39 (6), 709–716. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2007.10.016

Hassan, I. A., Ramadan, H. S., Saleh, M. A., and Hissel, D. (2021). Hydrogen storage technologies for stationary and mobile applications: review, analysis and perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 149, 111311. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111311

Haynes, W. M. (2016). “CRC handbook of chemistry and physics,”. 97th Edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press. doi:10.1201/9781315380476

Herradon, C., Le, L., Meisel, C., Huang, J., Chmura, C., Kim, Y., et al. (2022). Proton-conducting ceramics for water electrolysis and hydrogen production at elevated pressure. Front. Energy Res. 10. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2022.1020960

Hinata, K., Sata, N., Costa, R., and Iguchi, F. (2020). High temperature elastic modulus of proton conducting ceramics Y-doped Ba(Zr,Ce)O3. ECS Meet. Abstr. MA2020-02 (40), 2617. doi:10.1149/MA2020-02402617mtgabs

Hong, J., Bhardwaj, A., Bae, H., Kim, I.-h., and Song, S.-J. (2020). Electrochemical impedance analysis of SOFC with transmission line model using distribution of relaxation times (DRT). J. Electrochem. Soc. 167 (11), 114504. doi:10.1149/1945-7111/aba00f

Huang, J., Papac, M., and O’Hayre, R. (2021b). Towards robust autonomous impedance spectroscopy analysis: a calibrated hierarchical Bayesian approach for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) inversion. Electrochimica Acta 367, 137493. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2020.137493

Huang, J., Sullivan, N. P., Zakutayev, A., and O’Hayre, R. (2023b). How reliable is distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis? A dual regression-classification perspective on DRT estimation, interpretation, and accuracy. Electrochimica Acta 443, 141879. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2023.141879

Huang, J. D., Meisel, C., Sullivan, N. P., Zakutayev, A., and O’Hayre, R. (2024). Rapid mapping of electrochemical processes in energy-conversion devices. Joule 8, 2049–2072. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2024.05.003

Huang, W., Finnerty, C., Sharp, R., Wang, K., and Balili, B. (2017). High-performance 3D printed microtubular solid oxide fuel cells. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2 (4), 1600258. doi:10.1002/admt.201600258

Huang, W., Finnerty, C., Wang, K., Sharp, R., and Balili, B. (2019). Operation of micro tubular solid oxide fuel cells integrated with propane reformers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 44 (60), 32158–32163. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.10.061

Huang, Y., Merkle, R., and Maier, J. (2020). Effect of NiO addition on proton uptake of BaZr1-xYxO3-x/2 and BaZr1-xScxO3-x/2 electrolytes. Solid State Ionics 347, 115256. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2020.115256

Huang, Y., Merkle, R., and Maier, J. (2021a). Effects of NiO addition on sintering and proton uptake of Ba(Zr,Ce,Y)O3-δ. J. Mater. Chem. A 9 (26), 14775–14785. doi:10.1039/D1TA02555D

Huang, Y., Merkle, R., Zhou, D., Sigle, W., van Aken, P. A., and Maier, J. (2023a). Effect of Ni on electrical properties of Ba(Zr,Ce,Y)O3-δ as electrolyte for protonic ceramic fuel cells. Solid State Ionics 390, 116113. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2022.116113

IEA (2024). Global critical minerals outlook 2024, tech. Rep. Paris: International Energy Agency IEA.

IRENA (2022). “World energy transitions outlook 1-5C pathway 2022 edition,” in Tech. rep.(Abu Dhabi: IRENA).

Iguchi, F., and Hinata, K. (2021). High-temperature elastic properties of yttrium-doped barium zirconate. Metals 11 (6), 968. doi:10.3390/met11060968

Iguchi, F., Sata, N., Tsurui, T., and Yugami, H. (2007). Microstructures and grain boundary conductivity of BaZr1-xYxO3 (x=0.05, 0.10, 0.15) ceramics. Solid State Ionics 178 (7), 691–695. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2007.02.019

Ivers-Tiffée, E., and Weber, A. (2017). Evaluation of electrochemical impedance spectra by the distribution of relaxation times. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 125 (4), 193–201. doi:10.2109/jcersj2.16267

Joint Research Centre (European Commission) Carrara, S., Bobba, S., Blagoeva, D., Alves Dias, P., Cavalli, A., Georgitzikis, K., et al. (2023). Supply chain analysis and material demand forecast in strategic technologies and sectors in the EU: a foresight study. Publications Office of the European Union.

Kang, S., Yao, P., Pan, Z., Jing, Y., Liu, S., Zhou, Y., et al. (2024). High-temperature mechanical–conductive behaviors of proton-conducting ceramic electrolytes in solid oxide fuel cells. Materials 17 (19), 4689. doi:10.3390/ma17194689

Kendall, K., Dikwal, C. M., and Bujalski, W. (2007). Comparative analysis of thermal and redox cycling for microtubular SOFCs. ECS Trans. 7 (1), 1521–1526. doi:10.1149/1.2729257

Kendall, K., and Sales, G. (1994). “A rapid heating ceramic fuel cell,” in The institute of energy’s second international conference on ceramics in energy applications. Editor P. Kirkwood (Oxford: Pergamon), 55–63. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-042133-9.50008-3

Kim, H.-M., and Jariwala, D. (2023). The not-so-rare earth elements: a question of supply and demand.

Kim, H.-S., Bae, H. B., Jung, W., and Chung, S.-Y. (2018). Manipulation of nanoscale intergranular phases for high proton conduction and decomposition tolerance in BaCeO3 polycrystals. Nano Lett. 18 (2), 1110–1117. doi:10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04655

Kindelmann, M., Ebert, J. N., Scheld, W. S., Deibert, W., Meulenberg, W. A., Rheinheimer, W., et al. (2023). Cold sintering of BaZr0.7Ce0.2Y0.1O3-δ ceramics by controlling the phase composition of the starting powders. Scr. Mater. 224, 115147. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2022.115147

Kjølseth, C., Fjeld, H., Prytz, Ø., Dahl, P. I., Estournès, C., Haugsrud, R., et al. (2010). Space–charge theory applied to the grain boundary impedance of proton conducting BaZr0.9Y0.1O3-δ. Solid State Ionics 181 (5), 268–275. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2010.01.014

Kreuer, K. D. (2003). Proton-conducting oxides. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 33 (1), 333–359. doi:10.1146/annurev.matsci.33.022802.091825

Krishnan, V. V. (2017). Recent developments in metal-supported solid oxide fuel cells. WIREs Energy Environ. 6 (5), e246. doi:10.1002/wene.246

Ku, A. Y., Alonso, E., Eggert, R., Graedel, T., Habib, K., Hool, A., et al. (2024). Grand challenges in anticipating and responding to critical materials supply risks. Joule 8 (5), 1208–1223. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2024.03.001

Kuroha, T., Niina, Y., Shudo, M., Sakai, G., Matsunaga, N., Goto, T., et al. (2021). Optimum dopant of barium zirconate electrolyte for manufacturing of protonic ceramic fuel cells. J. Power Sources 506, 230134. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230134

Kuroha, T., Yamauchi, K., Mikami, Y., Tsuji, Y., Niina, Y., Shudo, M., et al. (2020). Effect of added Ni on defect structure and proton transport properties of indium-doped barium zirconate. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 45 (4), 3123–3131. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.11.128

Lagaeva, J., Medvedev, D., Demin, A., and Tsiakaras, P. (2015). Insights on thermal and transport features of BaCe0.8-xZrxY0.2O3-δ proton-conducting materials. J. Power Sources 278, 436–444. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.12.024

Le, L. Q., Meisel, C., Hernandez, C. H., Huang, J., Kim, Y., O’Hayre, R., et al. (2022). Performance degradation in proton-conducting ceramic fuel cell and electrolyzer stacks. J. Power Sources 537, 231356. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.231356

Leah, R. T., Bone, A., Selcuk, A., Rahman, M., Clare, A., Lankin, M., et al. (2019). Latest results and commercialization of the ceres power SteelCell® technology platform. ECS Trans. 91 (1), 51–61. doi:10.1149/09101.0051ecst

Lee, K. T., and Manthiram, A. (2005). Characterization of Nd0.6Sr0.4Co1-yFeyO3-δ (0 ≤ y ≤ 0.5) cathode materials for intermediate temperature solid oxide fuel cells. Solid State Ionics 176 (17), 1521–1527. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2005.05.002

Li, J., Wang, C., Wang, X., and Bi, L. (2020). Sintering aids for proton-conducting oxides – a double-edged sword? A mini review. Electrochem. Commun. 112, 106672. doi:10.1016/j.elecom.2020.106672

Li, T. S., Wang, W. G., Miao, H., Chen, T., and Xu, C. (2010). Effect of reduction temperature on the electrochemical properties of a Ni/YSZ anode-supported solid oxide fuel cell. J. Alloys Compd. 495 (1), 138–143. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2010.01.103

Li, Y., Guo, S., and Han, D. (2023). Doping strategies towards acceptor-doped barium zirconate compatible with nickel oxide anode substrate subjected to high temperature co-sintering. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 48 (44), 16875–16884. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.01.171

Liang, M., Liu, D., Zhu, Y., Yang, G., Ran, R., Shao, Z., et al. (2022). Nickel doping manipulation towards developing high-performance cathode for proton ceramic fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 169, 094509. doi:10.1149/1945-7111/ac9088

Liu, Z., Chen, M., Zhou, M., Cao, D., Liu, P., Wang, W., et al. (2020). Multiple effects of iron and nickel additives on the properties of proton conducting yttrium-doped barium cerate-zirconate electrolytes for high-performance solid oxide fuel cells. ACS Appl. Mater. and Interfaces 12 (45), 50433–50445. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c14523

Løken, A., Svendsen Bjørheim, T., and Haugsrud, R. (2015). The pivotal role of the dopant choice on the thermodynamics of hydration and associations in proton conducting BaCe0.9X0.1O3-δ (X = Sc, Ga, Y, In, Gd and Er). J. Mater. Chem. A 3 (46), 23289–23298. doi:10.1039/C5TA04932F

Longden, T., Beck, F. J., Jotzo, F., Andrews, R., and Prasad, M. (2022). Clean’ hydrogen? – Comparing the emissions and costs of fossil fuel versus renewable electricity based hydrogen. Appl. Energy 306, 118145. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.118145

Luo, Z., Zhou, Y., Hu, X., Kane, N., Li, T., Zhang, W., et al. (2022). Critical role of acceptor dopants in designing highly stable and compatible proton-conducting electrolytes for reversible solid oxide cells. Energy and Environ. Sci. 15 (7), 2992–3003. doi:10.1039/D2EE01104B

Magrez, A., and Schober, T. (2004). Preparation, sintering, and water incorporation of proton conducting Ba0.99Zr0.8Y0.2O3-δ: comparison between three different synthesis techniques. Solid State Ionics 175 (1), 585–588. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2004.03.045

Malerød-Fjeld, H., Clark, D., Yuste-Tirados, I., Zanón, R., Catalán-Martinez, D., Beeaff, D., et al. (2017). Thermo-electrochemical production of compressed hydrogen from methane with near-zero energy loss. Nat. Energy 2 (12), 923–931. doi:10.1038/s41560-017-0029-4

Matus, Y. B., De Jonghe, L. C., Jacobson, C. P., and Visco, S. J. (2005). Metal-supported solid oxide fuel cell membranes for rapid thermal cycling. Solid State Ionics 176 (5), 443–449. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2004.09.056

Mazloomi, K., and Gomes, C. (2012). Hydrogen as an energy carrier: prospects and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16 (5), 3024–3033. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.02.028

McLennan, S. M. (2001). Relationships between the trace element composition of sedimentary rocks and upper continental crust. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2 (4). doi:10.1029/2000GC000109

Medvedev, D. A., Gorbova, E. V., Demin, A. K., and Antonov, B. D. (2011). Structure and electric properties of BaCe0.77-xZrxGd0.2Cu0.03O3-δ. Russ. J. Electrochem. 47 (12), 1404–1410. doi:10.1134/S1023193511090138

Meisel, C., Huang, J., Kim, Y.-D., O’Hayre, R., and Sullivan, N. P. (2024b). Towards improved stability in proton-conducting ceramic fuel cells. J. Power Sources 615, 235021. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.235021

Meisel, C., Huang, J. D., Kim, Y.-D., Stockburger, S., O’Hayre, R., and Sullivan, N. P. (2025). Insights on proton-conducting ceramic electrochemical cell fabrication. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. n/a 108 (n/a), e20321. doi:10.1111/jace.20321

Meisel, C., Huang, J. D., Le, L., Kim, Y.-D., Stockburger, S., Luo, Z., et al. (2024a). Data-driven insights into protonic-ceramic fuel cell and electrolysis performance under Reivew.

Mercadelli, E., Gondolini, A., Ardit, M., Cruciani, G., Melandri, C., Escolástico, S., et al. (2022). Chemical and mechanical stability of BCZY-GDC membranes for hydrogen separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 289, 120795. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2022.120795

MilliporeSigma (2024). Life science products and service solutions. Available at: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/US/en.

Mortalò, C., Boaro, M., Rebollo, E., Zin, V., Aneggi, E., Fabrizio, M., et al. (2020). Insights on the interfacial processes involved in the mechanical and redox stability of the BaCe0.65Zr0.20Y0.15O3-δ–Ce0.85Gd0.15O2-δ composite. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3 (10), 9877–9888. doi:10.1021/acsaem.0c01589

Mortalò, C., Santoru, A., Pistidda, C., Rebollo, E., Boaro, M., Leonelli, C., et al. (2019). Structural evolution of BaCe0.65Zr0.20Y0.15O3-δ-Ce0.85Gd0.15O2-δ composite MPEC membrane by in-situ synchrotron XRD analyses. Mater. Today Energy 13, 331–341. doi:10.1016/j.mtener.2019.06.004

Nasani, N., Pukazhselvan, D., Kovalevsky, A. V., Shaula, A. L., and Fagg, D. P. (2017). Conductivity recovery by redox cycling of yttrium doped barium zirconate proton conductors and exsolution of Ni-based sintering additives. J. Power Sources 339, 93–102. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.11.036

Nielsen, J., Persson, Å. H., Muhl, T. T., and Brodersen, K. (2018). Towards high power density metal supported solid oxide fuel cell for mobile applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 165 (2), F90–F96. doi:10.1149/2.0741802jes

Nikodemski, S., Tong, J., and O’Hayre, R. (2013). Solid-state reactive sintering mechanism for proton conducting ceramics. Solid State Ionics 253, 201–210. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2013.09.025

O’Hayre, R., Cha, S.-W., Colella, W., and Prinz, F. B. (2009). Fuel cell fundamentals. 2nd Edition. Hoboken, N.J: John Wiley and Sons.

Okuyama, Y., Harada, Y., Mikami, Y., Yamauchi, K., Kuroha, T., Shimada, H., et al. (2023). Evaluation of hydrogen ions flowing through protonic ceramic fuel cell using ytterbium-doped barium zirconate as electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 170 (8), 084509. doi:10.1149/1945-7111/acef64

Osinkin, D. A. (2022). Detailed analysis of electrochemical behavior of high–performance solid oxide fuel cell using DRT technique. J. Power Sources 527, 231120. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2022.231120

Pan, L., Zhu, G., Coors, W. G., Manerbino, A., and Ricote, D. M. a. S. (2016). “Perovskite materials - synthesis, characterisation, properties, and applications,” in Perovskite materials - synthesis, characterisation, properties, and applications (IntechOpen). doi:10.5772/60469

Papac, M., Stevanović, V., Zakutayev, A., and O’Hayre, R. (2021). Triple ionic–electronic conducting oxides for next-generation electrochemical devices. Nat. Mater. 20 (3), 301–313. doi:10.1038/s41563-020-00854-8

Park, K., Bae, H., Kim, H.-K., Choi, I.-G., Jo, M., Park, G.-M., et al. (2022). Understanding the highly electrocatalytic active mixed triple conducting NaxCa3–xCo4O9–δ oxygen electrode materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 13 (2), 2202999. doi:10.1002/aenm.202202999

Pirou, S., Wang, Q., Khajavi, P., Georgolamprou, X., Ricote, S., Chen, M., et al. (2022). Planar proton-conducting ceramic cells for hydrogen extraction: mechanical properties, electrochemical performance and up-scaling. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 47 (10), 6745–6754. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.12.041

Pivovar, B., Rustagi, N., and Satyapal, S. (2018). Hydrogen at scale (H2@Scale): key to a clean, economic, and sustainable energy system. Electrochem. Soc. Interface 27 (1), 47–52. doi:10.1149/2.F04181if

Polfus, J. M., Fontaine, M.-L., Thøgersen, A., Riktor, M., Norby, T., and Bredesen, R. (2016). Solubility of transition metal interstitials in proton conducting BaZrO3 and similar perovskite oxides. J. Mater. Chem. A 4 (21), 8105–8112. doi:10.1039/C6TA02377K

Porz, L., Scherer, M., Huhn, D., Heine, L.-M., Britten, S., Rebohle, L., et al. (2022a). Blacklight sintering of ceramics. Mater. Horizons 9 (6), 1717–1726. doi:10.1039/D2MH00177B

Porz, L., Scherer, M., Muhammad, Q. K., Higuchi, K., Li, Y., Koga, S., et al. (2022b). Microstructure and conductivity of blacklight-sintered TiO2, YSZ, and Li0.33La0.57TiO3. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 105 (12), 7030–7035. doi:10.1111/jace.18686

Rahaman, M. (2003). “Ceramic processing and sintering,” in Materials engineering. 2nd Edition. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor and Francis Group.

Reese, M. O., Marshall, A. R., and Rumbles, G. (2017). “Reliably measuring the performance of emerging photovoltaic solar cells,” in Nanostructured materials for type III photovoltaics. Editors P. Skabara, and M. A. Malik (The Royal Society of Chemistry), 1–32. doi:10.1039/9781782626749-00001

Rheinheimer, W., Phuah, X. L., Wang, H., Lemke, F., Hoffmann, M. J., and Wang, H. (2019). The role of point defects and defect gradients in flash sintering of perovskite oxides. Acta Mater. 165, 398–408. doi:10.1016/j.actamat.2018.12.007

Ricote, S., Bonanos, N., Manerbino, A., Sullivan, N. P., and Coors, W. G. (2014). Effects of the fabrication process on the grain-boundary resistance in BaZr0.9Y0.1O3-δ. J. Mater. Chem. A 2 (38), 16107–16115. doi:10.1039/C4TA02848A

Rybakov, K. I., Olevsky, E. A., and Krikun, E. V. (2013). Microwave sintering: fundamentals and modeling. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 96 (4), 1003–1020. doi:10.1111/jace.12278

Schrijvers, D., Hool, A., Blengini, G. A., Chen, W.-Q., Dewulf, J., Eggert, R., et al. (2020). A review of methods and data to determine raw material criticality. Resour. Conservation Recycl. 155, 104617. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104617

Sharma, P., Burolia, A. K., Mandal, A., and Neogi, S. (2024). “Chapter 4.2 - commercially available resources for physical hydrogen storage and distribution,” in Towards hydrogen infrastructure. Editors D. Jaiswal-Nagar, V. Dixit, and S. Devasahayam (Elsevier), 225–256. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-95553-9.00010-8

Shen, C.-T., Lee, Y.-H., Xie, K., Yen, C.-P., Jhuang, J.-W., Lee, K.-R., et al. (2017). Correlation between microstructure and catalytic and mechanical properties during redox cycling for Ni-BCY and Ni-BCZY composites. Ceram. Int. 43, S671–S674. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2017.05.250

Shima, D., and Haile, S. M. (1997). The influence of cation non-stoichiometry on the properties of undoped and gadolinia-doped barium cerate. Solid State Ionics 97 (1), 443–455. doi:10.1016/S0167-2738(97)00029-5

Shimada, H., Mikami, Y., Yamauchi, K., Kuroha, T., Uchi, T., Nakamura, K., et al. (2024). Improved durability of protonic ceramic fuel cells with BaZr0.8Yb0.2O3–δ electrolyte by introducing porous BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3–δ buffer interlayer. Ceram. Int. 50 (2), 3895–3901. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.11.150

Shimada, H., Yamaguchi, T., Sumi, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Nomura, K., Mizutani, Y., et al. (2019). A key for achieving higher open-circuit voltage in protonic ceramic fuel cells: lowering interfacial electrode polarization. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2 (1), 587–597. doi:10.1021/acsaem.8b01617

Shimada, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Matsuda, R. M., Sumi, H., Nomura, K., Shin, W., et al. (2021a). Protonic ceramic fuel cell with Bi-layered structure of BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3–δ functional interlayer and BaZr0.8Yb0.2O3–δ electrolyte. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 124504. doi:10.1149/1945-7111/ac3d04

Shimada, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Sumi, H., and Mizutani, Y. (2021b). Enhanced La0.6Sr0.4Co0.2Fe0.8O3–δ-based cathode performance by modification of BaZr0.1Ce0.7Y0.1Yb0.1O3–δ electrolyte surface in protonic ceramic fuel cells. Ceram. Int. 47 (11), 16358–16362. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.02.123

Shirpour, M., Rahmati, B., Sigle, W., van Aken, P. A., Merkle, R., and Maier, J. (2012). Dopant segregation and space charge effects in proton-conducting BaZrO3 perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 116 (3), 2453–2461. doi:10.1021/jp208213x

Snijkers, F. M. M., Buekenhoudt, A., Cooymans, J., and Luyten, J. J. (2004). Proton conductivity and phase composition in BaZr0.9Y0.1O3-δ. Scr. Mater. 50 (5), 655–659. doi:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2003.11.028

Staffell, I., Scamman, D., Abad, A. V., Balcombe, P., Dodds, P. E., Ekins, P., et al. (2019). The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system. Energy and Environ. Sci. 12 (2), 463–491. doi:10.1039/C8EE01157E

Sumi, H., Shimada, H., Yamaguchi, Y., Mizutani, Y., Okuyama, Y., and Amezawa, K. (2021). Comparison of electrochemical impedance spectra for electrolyte-supported solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) and protonic ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs). Sci. Rep. 11 (1), 10622. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-90211-9

Tang, C., Akimoto, K., Wang, N., Fadillah, L., Kitano, S., Habazaki, H., et al. (2021). The effect of an anode functional layer on the steam electrolysis performances of protonic solid oxide cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 9 (24), 14032–14042. doi:10.1039/D1TA02848K

Tong, J., Clark, D., Bernau, L., Sanders, M., and O’Hayre, R. (2010c). Solid-state reactive sintering mechanism for large-grained yttrium-doped barium zirconate proton conducting ceramics. J. Mater. Chem. 20 (30), 6333–6341. doi:10.1039/C0JM00381F

Tong, J., Clark, D., Bernau, L., Subramaniyan, A., and O’Hayre, R. (2010b). Proton-conducting yttrium-doped barium cerate ceramics synthesized by a cost-effective solid-state reactive sintering method. Solid State Ionics 181 (33), 1486–1498. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2010.08.022

Tong, J., Clark, D., Hoban, M., and O’Hayre, R. (2010a). Cost-effective solid-state reactive sintering method for high conductivity proton conducting yttrium-doped barium zirconium ceramics. Solid State Ionics 181 (11), 496–503. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2010.02.008

Ueno, K., Hatada, N., Han, D., and Uda, T. (2019). Thermodynamic maximum of Y doping level in barium zirconate in co-sintering with NiO. J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (12), 7232–7241. doi:10.1039/C8TA12245H

Vafaeenezhad, S., Sandhu, N. K., Hanifi, A. R., Etsell, T. H., and Sarkar, P. (2019). Development of proton conducting fuel cells using nickel metal support. J. Power Sources 435, 226763. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.226763

Wang, C., Ping, W., Bai, Q., Cui, H., Hensleigh, R., Wang, R., et al. (2020). A general method to synthesize and sinter bulk ceramics in seconds. Science 368 (6490), 521–526. doi:10.1126/science.aaz7681

Wang, M., Hua, Y., Gu, Y., Yin, Y., and Bi, L. (2024b). High-entropy design in sintering aids for proton-conducting electrolytes of solid oxide fuel cells. Ceram. Int. 50 (2), 4204–4212. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.11.104

Wang, Z., Luo, Z., Xu, H., Zhu, T., Guan, D., Lin, Z., et al. (2024a). New understanding and improvement in sintering behavior of cerium-rich perovskite-type protonic electrolytes. Adv. Funct. Mater. n/a 34 (n/a), 2402716. doi:10.1002/adfm.202402716

Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Wang, J., Song, Y., Robson, M. J., Seong, A., et al. (2022). Rational design of perovskite ferrites as high-performance proton-conducting fuel cell cathodes. Nat. Catal. 5 (9), 777–787. doi:10.1038/s41929-022-00829-9

Yamazaki, Y., Hernandez-Sanchez, R., and Haile, S. M. (2010). Cation non-stoichiometry in yttrium-doped barium zirconate: phase behavior, microstructure, and proton conductivity. J. Mater. Chem. 20 (37), 8158–8166. doi:10.1039/C0JM02013C

Yao, Y., Huang, Z., Xie, P., Lacey, S. D., Jacob, R. J., Xie, H., et al. (2018). Carbothermal shock synthesis of high-entropy-alloy nanoparticles. Science 359 (6383), 1489–1494. doi:10.1126/science.aan5412

Zhai, S., Xie, H., Cui, P., Guan, D., Wang, J., Zhao, S., et al. (2022). A combined ionic Lewis acid descriptor and machine-learning approach to prediction of efficient oxygen reduction electrodes for ceramic fuel cells. Nat. Energy 7 (9), 866–875. doi:10.1038/s41560-022-01098-3

Zhang, J., Ricote, S., Hendriksen, P. V., and Chen, Y. (2022). Advanced materials for thin-film solid oxide fuel cells: recent progress and challenges in boosting the device performance at low temperatures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32 (22), 2111205. doi:10.1002/adfm.202111205

Zheng, K., Li, L., and Ni, M. (2014). Investigation of the electrochemical active thickness of solid oxide fuel cell anode. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39 (24), 12904–12912. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2014.06.108

Zhou, W., Malzbender, J., Zeng, F., Deibert, W., Winnubst, L., Nijmeijer, A., et al. (2022). Mechanical properties of BaCe0.65Zr0.2Y0.15O3-δ – Ce0.85Gd0.15O2-δdual-phase proton-conducting material with emphasis on micro-pillar splitting. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 42 (9), 3948–3956. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2022.03.020

Zhu, H., and Kee, R. J. (2008). Modeling distributed charge-transfer processes in SOFC membrane electrode assemblies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 155 (7), B715. doi:10.1149/1.2913152

Zohourian, R., Merkle, R., Raimondi, G., and Maier, J. (2018). Mixed-conducting perovskites as cathode materials for protonic ceramic fuel cells: understanding the trends in proton uptake. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28 (35), 1801241. doi:10.1002/adfm.201801241

Zou, D., Yi, Y., Song, Y., Guan, D., Xu, M., Ran, R., et al. (2022). The BaCe0.16Y0.04Fe0.8O3-δ nanocomposite: a new high-performance cobalt-free triple-conducting cathode for protonic ceramic fuel cells operating at reduced temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. A 10 (10), 5381–5390. doi:10.1039/D1TA10652J

Keywords: fuel cell, electrolysis, proton-conducting ceramic, benchmarking, critical materials, sintering, distribution of relaxation times (DRT), fabrication

Citation: Meisel C, Kim Y-D, Diercks D, O’Hayre R and Sullivan NP (2025) Advancing proton-conducting ceramic electrochemical devices: perspectives on benchmarking and barriers to progress. Front. Energy Res. 13:1565315. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2025.1565315

Received: 23 January 2025; Accepted: 14 February 2025;

Published: 04 June 2025.

Edited by:

David Marrero-López, University of Malaga, SpainReviewed by:

Min Chen, Foshan University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Meisel, Kim, Diercks, O’Hayre and Sullivan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Charlie Meisel, Y21laXNlbEBtaW5lcy5lZHU=; Neal P. Sullivan, bnN1bGxpdmFAbWluZXMuZWR1

Charlie Meisel

Charlie Meisel You-Dong Kim

You-Dong Kim David Diercks

David Diercks Ryan O’Hayre

Ryan O’Hayre Neal P. Sullivan

Neal P. Sullivan