- 1Department of Forest Biomaterials, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, United States

- 2Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, United States

- 3Department of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, United States

- 4National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, United States

- 5IBM Corporation, Durham, NC, United States

- 6Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, United States

The accumulation of municipal solid waste (MSW) continues to rise due to burgeoning population, rapid global urbanization and economic growth, intensifying ecological concerns associated with landfills and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Over the past 2 decades, global waste generation has surged by 50%, with one-third remaining uncollected and about 70% sent to landfills. This review examines the critical role of integrating emerging technologies, such as advanced sensors and artificial intelligence (AI), into end-to-end MSW management to alleviate landfill burdens. The suitability of various AI tools for different stages of MSW management is assessed, alongside the deployment of advanced sensors including hyperspectral cameras, computer vision systems, and internet of things (IoT) devices for material identification. Applications of genetic algorithms and reinforcement learning for optimizing collection routes, reducing costs, and lowering emissions are highlighted. Life cycle assessment (LCA) across all stages of MSW management is also reviewed, along with future trends in leveraging generative AI, natural language processing (NLP), and agent-based AI systems to analyze waste generation patterns and public sentiment. Efficient collection and handling can be enhanced through route optimization with geographic information systems and real-time bin-level monitoring. Furthermore, sensor-embedded, real-time object detection systems paired with robotics enable material characterization and automated sorting, thereby lowering costs and diverting waste from landfills into value-added products for diverse industrial sectors including packaging, chemicals, textiles, metals and glass, transportation, and electronics industries. Without intervention, global waste is projected to reach 4.54 billion tons by 2050, contributing direct economic costs of $400 billion and roughly 2.38 billion tons of CO2-equivalent emissions annually. This review demonstrates how AI-driven, end-to-end solutions for MSW management can mitigate economic and environmental challenges, while directly supporting the United Nations Sustainable Development (UNDP) goals related to innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), sustainable cities (SDG 11), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), and climate action (SDG 13).

1 Introduction

Municipal solid waste (MSW) generation is increasing due to a burgeoning population, and urbanization. Globally, approximately 2.0–2.3 billion tons of MSW is generated annually, out of which, nearly one-third is neither collected nor managed (Kaza et al., 2018). Among the collected waste, approximately 11% is incinerated for energy recovery, 19% is recycled, and 70% is landfilled (Kumar and Samadder, 2023). By 2050, global MSW generation is projected to reach 4.54 billion tons, resulting in approximately 2.38 billion tons of CO2 equivalent emissions annually (Maalouf and Mavropoulos, 2023). Beyond the environmental burden, the economic impact is substantial as inefficient waste management is estimated to cost $640 billion annually driven by an increase in landfill development costs, loss of resources and public health expenditures (MRW, 2024). Addressing these challenges alignes directly with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially SDG nine (industry, innovation and infrastructure), SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities), SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and SDG 13 (Climate action). To put these global goals into practice requires a systematic approach across the entire MSW management cycle.

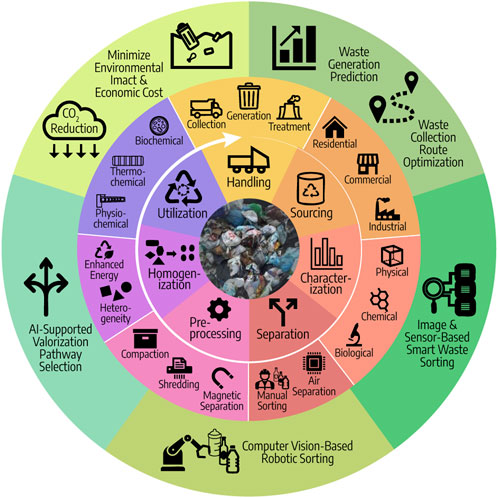

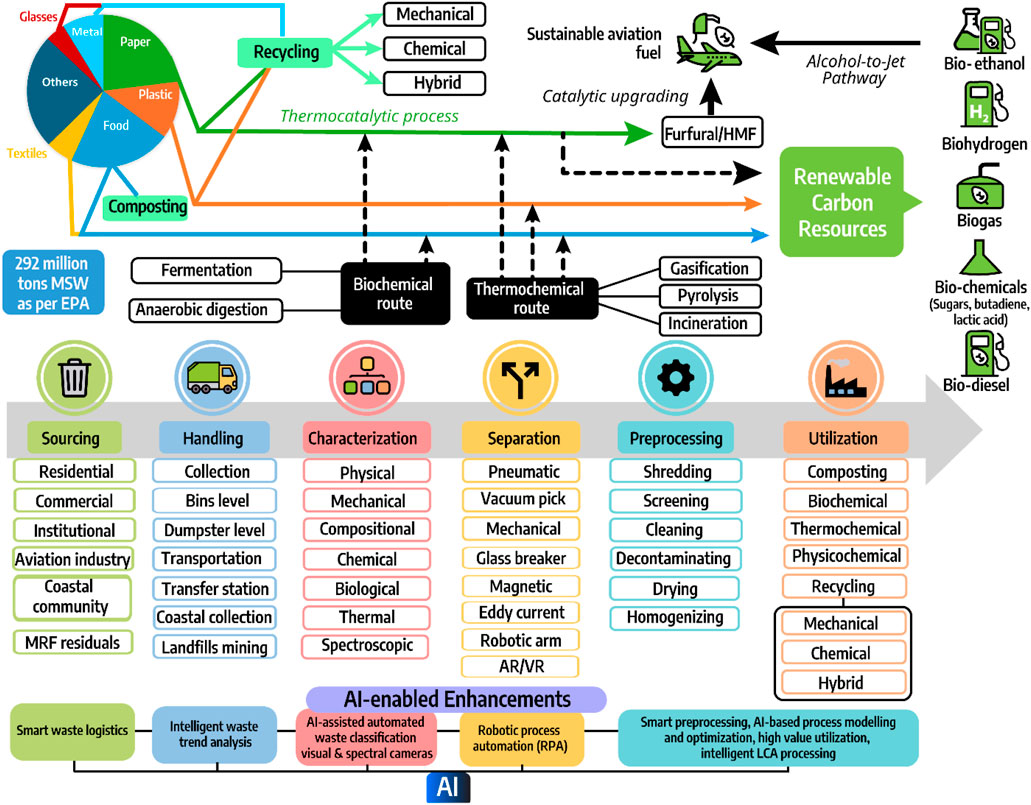

The end-to-end process is illustrated in Figure 1, highlighting both conventional methodologies and AI-driven enhancements at each stage. Each stage in the cycle plays a critical role in valorization, including energy recovery, material recycling, and safe disposal. The first stage, handling and sourcing encompasses the generation and collection of MSW. The second stage involves characterization, separation and preprocessing, key steps for identifying, sorting, decontaminating, and reducing the size of waste to produce a uniform, conversion-ready feedstock. The final stage, utilization, focuses on expanding potential applications of this feedstock as a sustainable resource, thereby maximizing overall resource efficiency. The pie chart in Figure 1 illustrates the composition of MSW, highlighting the necessity of efficient processing for various material fractions (US EPA, 2023). Biochemical, thermochemical, and catalytic upgrading processes hold significant potential for converting waste into renewable carbon resources to support the production of low-carbon energy products such as sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), biogas, biohydrogen, and biodiesel, contributing to the development of a circular and low-carbon economy (Saravanan et al., 2025).

Figure 1. Overview of an AI-driven smart waste management system. This system integrates sourcing, handling, characterization, separation, preprocessing, and utilization of MSW within a circular bioeconomy. The accompanying pie chart excludes hazardous waste; the other category represents inorganic waste, rubber, leather, wood and yard trimmings.

MSW management comprises a set of complex actions, including waste sourcing, collection, characterization and separation into different streams, recycling, energy recovery, and waste treatment processes. In recent years, various energy generation technologies have been developed for managing non-recyclable MSW, including thermochemical, biochemical, and physicochemical approaches (Yaashikaa et al., 2020; Varjani et al., 2022). The selection of a particular process is determined by many factors including composition and quantity of MSW, environmental regulations, end-product requirements, economic feasibility, and geographical context. The growing dependency on landfilling highlights the need for innovative solutions for MSW management. Addressing this challenge requires advanced technologies to optimize waste handling, sourcing, and transportation, while also improving resource recovery.

Over the past decade, emerging smart manufacturing (SM) technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), cloud computing, and materials informatics have shown promise in advancing process and materials innovations, circularity, decarbonization, and digitization. ML, with its ability to generalize and perform well across various domains such as waste sorting, recycling, waste-to-energy conversion, and sourcing prediction, offers significant potential to reduce landfill dependency (Hoy et al., 2024). ML techniques can enhance each stage of the MSW management pipeline, including waste collection, handling, transportation, characterization, sorting, preprocessing, homogenization, and utilization into valuable products and energy. Multiple studies have implemented the use of ML techniques to predict waste generation within specific geographic regions, which help in creating waste management strategies (Golbaz et al., 2019). ML algorithms can enable real-time monitoring of waste collection sites and transfer stations. MSW can be automatically sorted into various categories, such as organics, recyclables, and hazardous materials, using sensors and robotics at materials recovery facilities (MRFs) (Andeobu et al., 2022). Additionally, real-time monitoring and diagnosis by analyzing sensor data can be employed for the maintenance of waste management systems (Gundupalli et al., 2017; Salem K. et al., 2023).

The integration of ML and AI with currently available technologies can enhance their performance in real-time applications, while overcoming current limitations. For instance, ML techniques can reduce the dimensionality of spectral information obtained during spectroscopic analysis, making it useful for waste management applications (Kale et al., 2017). This enables smarter decision-making by reducing data processing time and extracting only the most useful features. In addition, ML models can offer insights into public perception towards waste generation and management. Natural language processing (NLP) techniques, such as sentiment analysis of social media posts and digital content, can support the development of more effective public outreach programs (Munir et al., 2023).

Studies related to the application of AI in waste management generally focus on the use of different technologies within the overall waste management process, while overlooking operational analysis at each stage. For example, Abdallah et al., 2020 provided a potential application of AI in addressing solid waste management challenges (Abdallah et al., 2020). However, this work did not investigate the core components of MSW management process, such as collection, transportation, characterization, sorting, and disposal. The use of advanced technologies such as visual imaging (VI) and hyperspectral imaging (HSI), and robotics equipped with AI and computer vision for enhancing real-time characterization and separation of MSW has also not been fully explored. Similarly, another study examined the application of AI and Internet of Things (IoT) in solid waste management but did not provide detailed insights about AI’s application in individual operational units (Lakhouit, 2025). Moreover, existing reviews have largely overlooked the role of AI in integrated system design for sustainable MSW management, such as the use of AI-driven life cycle assessment (LCA) and techno-economic analysis (TEA) to simultaneously optimize the environmental and economic outcomes. Emerging AI technologies are rapidly advancing but remain unexplored in the domain of waste management.

To address this gap, this review highlights the dual benefits of integrating AI into each stage of MSW management processes to make the system robust, along with the potential of AI to optimize end-to-end system operations and reduce environmental impacts. Section 2 introduces AI and its categories, outlining studies that utilize algorithms, such as artificial neural networks (ANN), support vector machine (SVM), genetic algorithms (GA), decision tree (DT), and Linear Regression (LR) to analyze and understand MSW generation patterns. Section 3 focuses on the application of AI within the MSW management and valorization pipeline, including collection, transportation, and characterization using advanced sensor technologies. Section 4 reviews the applicability of AI in designing integrated systems across the MSW management pipeline, addressing both economic and environmental aspects. Finally, Section 5 discusses the outlook for implementing AI technologies in future MSW management systems.

2 Overview of AI and ML techniques for MSW management

AI techniques, particularly ML, enable computers to acquire knowledge and expertise through data-driven learning and subsequently use this knowledge for prediction or the execution of specific tasks (Li et al., 2022). In the context of MSW, AI enables intelligent data-driven decision making across forecasting, logistics optimization, and material classification pipelines. In this section, we first provide an overview of AI applications, followed by a detailed discussion of how these tools are applied at each stage of the MSW management process.

In this context, AI can be defined as the design of intelligent systems that are capable of processing and interpreting data related to MSW and take actions to optimize or enhance MSW management. ML, a subset of AI, has been defined as “A set of techniques that allow computers to learn from data and improve their performance over time without being explicitly programmed.” (Bristol et al., 2024). In scenarios where the best action is clearly defined by mathematical models or defined rules, traditional approaches may be used. However, MSW management often involves situations where such models are incomplete or require simplifying assumptions. For example, while the biogenic and fossil carbon content of individual waste fractions is documented, the heterogeneous and variable composition of MSW entering incinerators is rarely known with precision in real time. This uncertainty makes direct calculation of greenhouse gas emissions from first principles difficult in practice. In such cases, ML algorithms trained on available datasets can capture complex nonlinear relationships and provide more accurate estimates (Xia et al., 2022). This category of ML algorithms, trained using a dataset of inputs and corresponding outputs, is called supervised learning.

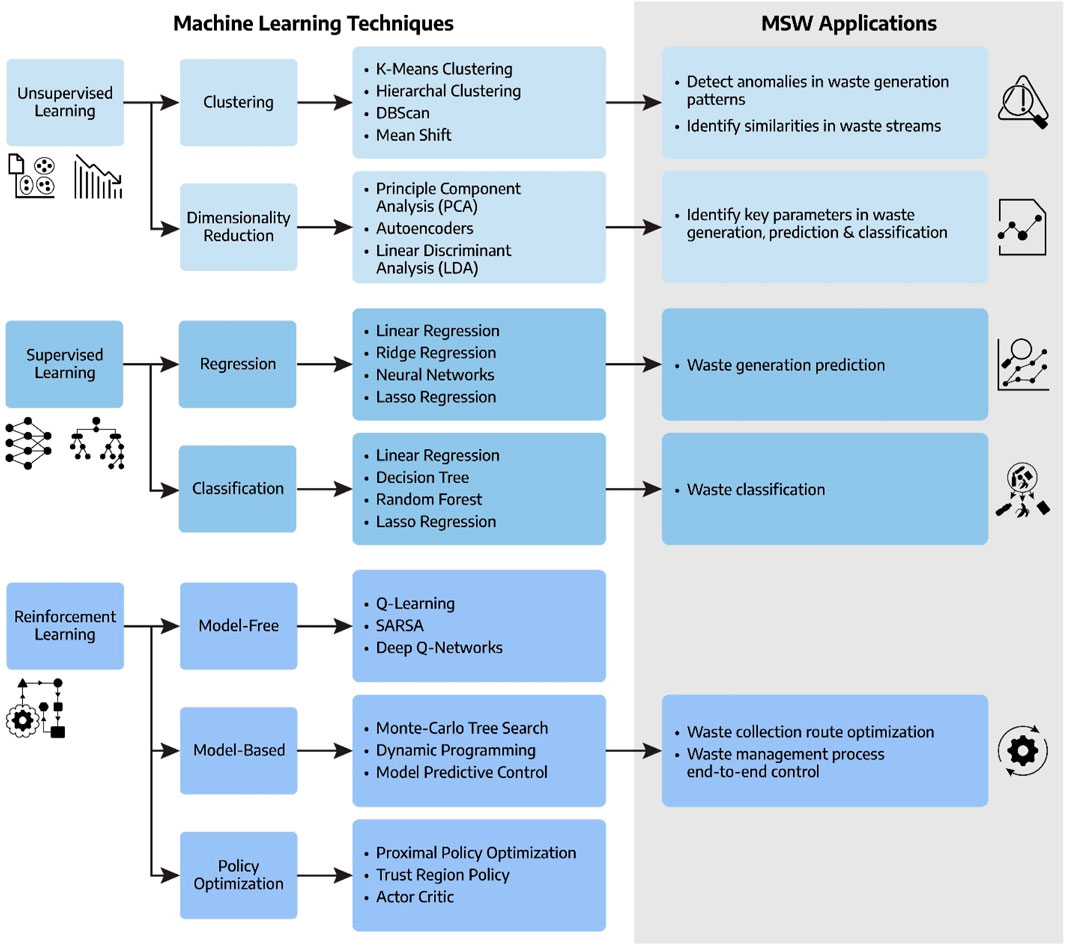

In certain cases where the labeled datasets are not available, ML algorithm employs unsupervised learning techniques to classify input data into categories based on the similarities and differences in their features. For example, unsupervised learning can group geographical regions based on their waste generation trends, enabling targeted waste management strategies. Another branch of ML is reinforcement learning, wherein the ML algorithm interacts with the environment, starting with random actions, and gradually learn the best actions to follow by observing the results of the actions, i.e., beneficial actions are reinforced based on rewards, while bad decisions are discouraged through penalties (Shakya et al., 2023). Figure 2 shows the ML categories in detail, along with their corresponding MSW applications.

Figure 2. Overview of ML techniques such as unsupervised, supervised, and reinforcement learning and their roles in MSW management. Together, these ML techniques represent a fusion of innovative and data driven solutions for revolutionizing MSW management.

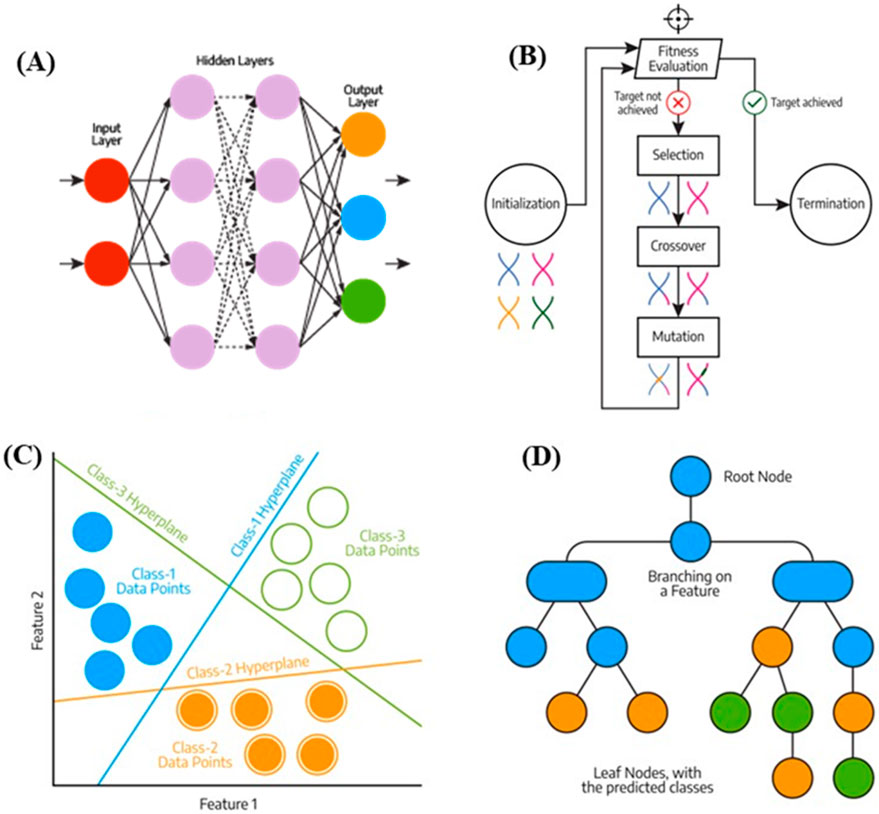

Among the various ML techniques, supervised learning models are the most widely used to address MSW management challenges. Specifically, ANN, GA, SVM, DT and LR are the most frequently employed are among the best approaches because they, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Schematic representations of four key ML models for MSW management (A) Artificial Neural Network (ANN), inspired by the human brain to identify complex patterns in waste data (Red = input nodes, purple = hidden layers, orange/blue/green = outputs). (B) Genetic Algorithm (GA), mimicking natural selection for resource allocation, including initialization, selection, crossover, and mutation. (C) support vector machine (SVM), which separates waste categories based on features and hyperplanes (blue = Class 1, orange = Class 2, green = Class 3). (D) Decision Tree (DT), which splits data by features into branches, with leaf nodes representing predicted classes (blue = Class 1, orange = Class 2, green = Class 3).

ANNs mimic the structure of the human brain by modelling neurons connected in layers to form a neural network (NN) (Abiodun et al., 2018). Each neuron processes multiple inputs into a weighed sum, which is passed through an activation function (e.g., sigmoid, softmax, hyperbolic tangent) to generate an output. (Oliveira et al., 2019). A typical NN consists of three layers: an input layer that receives the data, a hidden layer for processing, and an output layer that generates predictions. In MSW management, ANNs have been applied to predict bin levels, waste generation patterns, waste classification, and route optimization (Mounadel et al., 2023). Despite their strength, ANNs can struggle with the challenges such as overfitting, difficulty handling highly precise logical tasks and inability to assess relative importance of inputs in sensitivity analysis (Abiodun et al., 2018). NNs have shown good performance in MSW characterization studies, due to flexibility in adjusting diverse relation between input (waste type, composition, texture) and output classifications (Azadi and Karimi-Jashni, 2016).

GA simulates natural evolution to solve search and optimization problems by generating candidate solutions, evaluating them against a goal, merging the best solutions, and introducing random mutations until an optimum is reached (Sree and Kanmani, 2024). It has been applied in MSW management for route optimization, waste classification, generation forecasting and energy recovery predictions (Thaseen Ikram et al., 2023). For instance, a GA reduced collection distance by 66% and time from 7 h to 2.3 h per trip (Assaf and Saleh, 2017), while a hybrid GA lowered operation cost with 7.3% reduction in distance and 1.28% drop in carbon emission cost (Wang et al., 2025). SVMs follow a geometrical approach to identify the hyperplane that best separates data into classes while minimizing classification errors and model complexity. It has been used for bin occupancy estimation, waste classification, generation forecasting, energy recovery and heating value estimation (Bagheri et al., 2019). Trained on MSW data from 1997 to 2019, one SVM achieved an R2 of 0.97 with 4.8% forecasting error, showing its robustness (Jassim et al., 2022). However, their performance depends upon suitable kernel selection and parameters tuning (Dixon and Candade, 2008; Abdallah et al., 2020).

DTs classify data by generating a logical flowchart, offering interpretability, low computational costs and tolerance for missing data. It has been applied in waste forecasting, densification, categorization and identifying illegal dumping with studies showing effectiveness in predicting household waste collection and processing based on socioeconomic factors (Solano Meza et al., 2019). LR is a statistical method of finding the parameters of a straight line to interpolate and extrapolate between data points, with the minimum error. It is interpretable and computationally efficient though less effective for nonlinear data (Sree and Kanmani, 2024). It has been used in waste forecasting, leachate formation and route optimization. Studies have shown strong predictive performance, with models achieving R2 values up to 0.93 using long-term MSW data (Johnson et al., 2017). In conclusion, the AI models discussed here play a pivotal role in optimizing preprocessing and feedstock preparation in solid waste management.

3 AI applications in the MSW management and valorization pipeline

3.1 Forecasting and generation pattern prediction

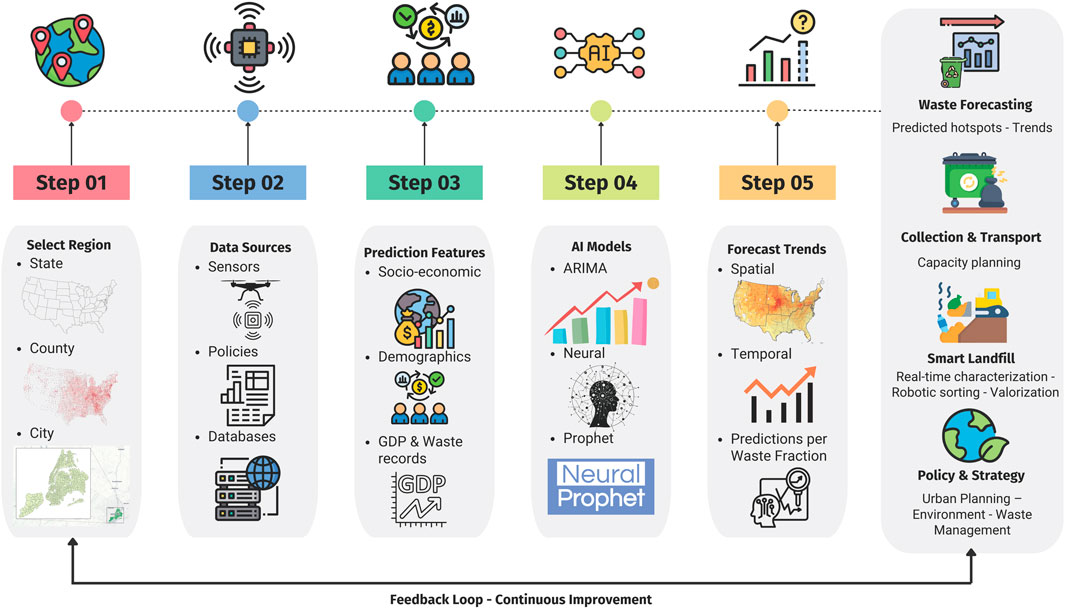

Forecasting waste generation is a prerequisite for demand-responsive MSW systems, enabling dynamic resource allocation and infrastructure scaling which is important for SDG 11 and SDG 9. The generation of solid waste has significantly increased due to rapid urbanization and population growth. This trend has prompted numerous attempts in the field of AI for accurately forecasting waste generation (Sharma and Vaid, 2021; Izquierdo-Horna et al., 2022). Accurate prediction of MSW generation holds great importance as it can assist urban environmental planning, operations, and oversight. This, in turn, facilitates the development of efficient strategies for waste collection, transportation, and treatment aligning with SDG 12. Hence, forecasting MSW forms the basis for effective waste management. The process of MSW generation is complex, as it is influenced by a range of factors such as demographic trends, economic development, and individual behaviors. The general process followed in research studies is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Overview of the general process in research studies to forecast the generated waste quantity. A geographical region of study is chosen. A dataset for prediction is created from governmental reports, open-source databases and real-time sensors such as bin-levels or remote monitoring. Relevant predictors are extracted from this dataset, and used to train AI models to predict waste, which then guide governmental policies and waste management strategies.

Multiple approaches have been suggested for the estimation of waste generation. These methodologies encompass diverse models which include statistical, ML, deep learning, and fuzzy models (Kolekar et al., 2016). The ML techniques (ANNs, SVM, DT, GA), described previously have been utilized to construct effective predictive models, particularly for datasets with limited instances primarily composed of categorical variables (Cha et al., 2022). Several models have been employed at various geographical scales, including municipality, provincial, and regional levels. Initially, simple methodologies such as linear regression, group comparisons, input-output analysis, mass balance, and correlation analysis were popular due to their straightforward mathematical foundations and easy interpretation of outcomes (Towa et al., 2020). However, the progression of research has led to the adoption of ML techniques such as Gradient Boosting, SVM, Random Forest and ANN to predict MSW generation in various regions (Lu W. et al., 2022). Advanced data analysis techniques, based on consumer waste levels in metropolitan regions, were utilized to create waste generation profiles. A data-based approach, utilizing self-organizing maps and k-means algorithms, was utilized and evaluated on extensive container-level waste inventory. The generated profiles revealed temporal trends, by forming clusters with peak waste generations in different seasons. Results were interpreted using a socio-economic grid and provided a means of implementing efficient waste management operations (Niska and Serkkola, 2018).

MSW generation rate varies across municipalities and therefore predictive models are important for estimating quantities from socio-economic and demographic variables. For example, a model for predicting MSW quantity across Canada, based on MSW generation rates, socio-economic and demographic factors from 220 Ontario municipalities was built and an ANN approach achieved an R2 of 0.72 and root mean square error of 20%, outperforming the decision tree method. However, the models showed lower performance for paper diversion with R2 of 0.31 and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 32%–34% due to the lack of suitable predictor variables (Kannangara et al., 2018). A study analyzed MSW generation trends on a much more localized level, predicting the waste generation trends of buildings in New York City using gradient boosted decision trees (GBRT). The result found that GBRTs offer robust generalization and interpretability, often outperforming ANN (Kontokosta et al., 2018).

A neural network was created to predict plastic generation of 27 European countries (EU-27) in 2030, as a function of energy consumption, circular material use rate, economic complexity index, population, and real gross domestic product. The study also considered the environmental impact of the projected plastic waste generation (17 Mt per year was predicted to be generated by EU-27 in 2030). Even with the European Union aiming for a 55% recycling rate by 2030, environmental impacts like global warming and marine pollution are expected to surpass the 2018 level, highlighting the importance of SDG 13 (Fan et al., 2022).

The above studies conclude that MSW generation is a complex process, influenced by demographic, economic, and behavioral factors, and require advanced prediction techniques. Linear models often fall short due to the nonlinear nature of these relationships, motivating the use of ML. Despite the accuracy of ML models, the main challenge lies in the availability of sufficient historical and relevant data, especially at the level of households and communities. Inadequate waste management practices can also contribute to data scarcity (Ayeleru et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2022). In scenarios where datasets exist, faulty sensors and suboptimal collection methods can contribute to inaccuracies. Additionally, the application of models across diverse cities is complex due to variations in population and infrastructure. Future forecasting systems must account for heterogeneous data sources, incorporate adaptive learning to manage concept drift, and include uncertainty quantification to inform risk-aware policy design.

3.2 MSW collection and transportation

The process of MSW management begins with collection and transportation of waste from source bins to a segregation site, where both manual and smart technologies are employed for efficient sorting. This practice is important to achieve SDG 11 and ensure clean and more sustainable urban communities. ML approaches assist by first estimating the waste level and composition in smart bins and then planning an optimal route for vehicles to collect and transport waste to segregation sites.

3.2.1 MSW bin filled-level detection

Efficient waste management requires accurate prediction of waste bin fill levels to prevent issues such as improper waste disposal and bin overloading. Addressing temporal variations in disposed quantities is crucial for the performance of smart waste collection systems. To achieve this, various bin level detection models have been developed, often utilizing real-time data from sensors embedded in smart waste bins (Abdallah et al., 2020). Image-based detectors are the most common, which are deployed on edge computing devices such as Raspberry Pis and utilize IoT communication technologies such as LoRa. Gray level aura matrix (GLAM) systems have been employed to detect bin level by extracting image textures, which are then classified using multi-layer Perceptions (MLP) and KNN classifiers. MLP achieved classification rates of 98.98% for bin levels and 90.19% for grades (e.g., low, medium, high), while KNN achieved 96.91% and 89.14%, respectively (Hannan et al., 2012). Dynamic time warping and Gabor Wavelet have also been used to train an MLP for accurate bin level prediction (98.5%) (Islam et al., 2014). Another study proposed a low-cost image-based method for detecting bin levels for electronic waste through wall entropy perturbation by evaluating multiple classifiers. The approach achieved the highest accuracy of 97.4% with MLP in assessing bin status (Ao, 2013).

Smart bin systems based on ultrasonic sensors have also been proposed to classify waste materials, monitor bin fill levels, and optimize waste collection routes using image processing and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Ultrasonic sensors identify filled bins, and a mobile app generates optimal collection routes (Abeygunawardhana et al., 2020). Commonly used AI techniques to detect waste bin status include CNNs, SVM, naive Bayes, and LR. A deep learning based smart waste bin system was developed for real-time waste classification that simultaneously detects and segregates waste materials. The system integrated Raspberry Pi, LoRa communication and servo-motors for compartmentalized lid control and automatic segregation (Sheng et al., 2020). An architecture supported by solar-powered cameras, a raspberry Pi mobile microprocessor, and LoRa communications have also been investigated (Jadli and Hain, 2020). Waste bin levels are generally monitored by applications that optimize collection schedules. These AI-driven systems pave the way for smarter waste management solutions by accurately predicting bin fill levels and enabling optimal waste collection strategies.

3.2.2 Vehicle route optimization

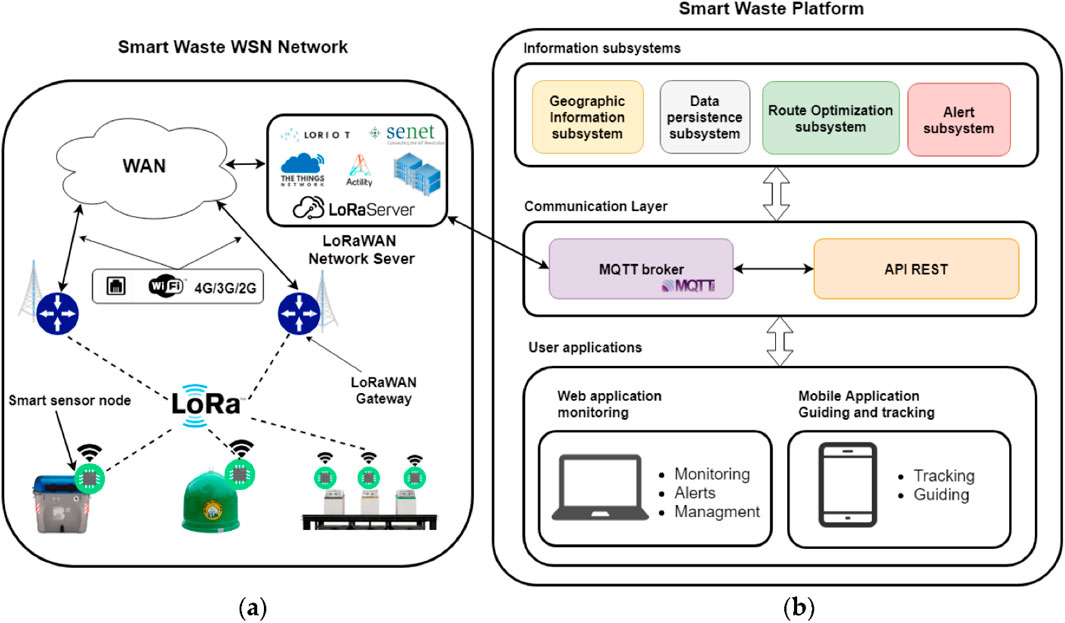

The general approach to waste collection route optimization (Figure 5) begins once the geographic scope of collection is defined and a route update frequency is set. Several factors determine the planning of routes. The most critical are location of waste bins and their real-time fill levels, which guide both spatial path and temporal collection frequencies (Folianto et al., 2015; Saha and Chaki, 2023). These systems could be further enhanced by integrating additional dynamic factors such as traffic flow, holidays, weather and special events.

Figure 5. Architecture of a smart waste management platform integrating IoT sensor nodes, LoRaWAN gateways, and cloud-based subsystems for monitoring, alerting, and route optimization. (a) Wireless Sensors Network (WSN) of smart sensors and (b) Information system, communication and user applications. Communication is enabled through an MQTT broker and REST APIs, linking information subsystems to web and mobile applications for guiding and tracking waste collection. Reproduced from (Lozano et al., 2018) under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license.

Based on these predictors, AI models generate optimized collection routes and resources such as vehicles and personnel are allocated to maximize efficiency aligning with SDG nine on innovative infrastructure and SDG 13 on climate action. An efficient collection and transportation system is central to MSW management, serving as the link between waste sources, disposal facilities, and resource recovery operations (Yadav and Karmakar, 2020). However, the sharp rise in MSW generation has strained treatment capacities and expanded the operational scope of collection systems, creating increasingly complex management requirements.

The notably high expenses linked to waste collection typically constitute 70%–85% of total cost of MSW management, making cost reduction a priority (Rodrigues et al., 2016). Personnel shortages and poor scheduling lead to inefficiencies, leading to delays, congestion, and underutilization of vehicles (Andeobu et al., 2022). Thus, the optimization of MSW collection frequency and routing is important to decrease transport cost and improve system effectiveness (Xia et al., 2022).

Approaches were developed to plan waste collection routes, based on real-time waste level values obtained from sensors in waste collection bins (de Morais et al., 2024). The routing problem was framed as dynamic reverse inventory routing problem, solved using a dynamic rolling horizon approach. The proposed approach was evaluated on a real-world dataset of sensor bin levels and was found to achieve a balance between collection efficiency and minimizing bin overflows. Similarly, advanced data analysis techniques of consumer waste levels in metropolitan regions, was used to create waste generation profiles (Niska and Serkkola, 2018).

GA has been widely applied for optimizing waste collection routes. For example, GA has reduced collection costs for electronic waste (Ma et al., 2025) and improved route efficiency with user participation, though service time was extended by 85% compared to the non-optimized approach (Krol et al., 2016). Hybrid GA–GIS approaches were used for real-world constraints such as road inclinations and traffic directions, producing routes closely aligned with optimal values (Duzgun et al., 2015). A specialized GIS-based GA called SGA further improved performance, cutting operating distance by 8%, travel time by 28%, and fuel consumption by 3% (Amal et al., 2018).

Another study combined ANN time series, GIS-Network Analysis, and VRP models to analyze routing and emissions. The ANN model performed better with less extreme waste data, with MAPE ranging from 10.92% to 16.51%. VRP models considered garbage and recyclables composition, showing significant changes in travel distances for recyclables collection trucks (Lan Vu et al., 2019). Yet another study suggests that robust regression models can be used to forecast fats, oils and grease (FOG) generation across multiple collection sites in the agro-food industry (Montecinos et al., 2018).

More advanced systems extend optimization to complex decision-making. In one study, a custom-built software called RouteSW successfully optimized routes using GA with path constraints such as left-hand turns, lane limits and multiple disposal sites (Duzgun et al., 2015). For infectious waste, a case study found that hybrid goal programming (HGP) and hybrid GA (HGA) can effectively optimized facility locations and vehicle routes, thus balancing interpretability, cost, and resource use (Wichapa and Khokhajaikiat, 2018). Fuzzy logic has also been incorporated with GA to optimize routes for electrical waste collection (Krol et al., 2016). AI has further supported bin placement optimization, with ANN models improving allocation strategies to enhance collection efficiency (Purkayastha et al., 2019). Collectively, these studies demonstrate how AI through GA, ANN, regression and hybrid frameworks can improve routing and infrastructure planning in MSW management.

3.3 MSW characterization and classification

Once MSW is collected and reaches its destination, it may be characterized and classified into desired categories such as paper, plastics, metals, textiles, hazardous materials, etc., before each category can be valorized. However, in many current systems, especially those depending upon direct landfilling or incineration, this level of categorization is not performed (Salem K. S. et al., 2023). Traditional methods struggle with accuracy and consistency, leading to suboptimal disposal, inefficient resource allocation, and environmental impact, which directly affects progress towards SDG 11 and SDG 12 (Munir et al., 2023). These shortcomings are particularly evident in heterogeneous and fast-changing waste streams, where contamination, mixed materials, and varying moisture levels complicate sorting processes. ML algorithms may potentially address these challenges by efficiently handling the dynamic waste stream, optimizing sorting and recycling, reducing resource usage, and making data-driven decisions. ML models can learn from large, annotated datasets and handle the variability inherent in MSW, thereby improving classification accuracy and enabling real-time decision-making. This optimization improves recycling rates, reduces landfill dependency and reduces operational costs, supporting SDG nine on innovation driven infrastructure and SDG 13 on climate action (Shakya et al., 2023).

Various ML techniques, particularly CNNs based models, have been applied to address the challenges of waste management (Shakya et al., 2023). Computer-vision based approaches, such as the You Only Look Once (YOLO) algorithm family, have gained significant attention for their real-time object detection capabilities. Unlike traditional two-stage detectors that first identify regions of interest before classification, YOLO introduced a single-step framework that processes the entire image in one pass, simultaneously detecting and localizing objects. Over the years, YOLO has undergone rapid and diverse evolutions, with variants from YOLOv3 to YOLOv9, and YOLOv12. These models have been deployed across a wide range of tasks such as trash sorting, plastic detection, and illegal dumping identification (Ghatkamble et al., 2022; Reddy et al., 2024). However, the latest YOLO model is not necessarily the most suitable for every application. Therefore, the adoption of YOLO model must balance accuracy, speed, computational requirements and robustness. YOLO-Green, an algorithm tailored for waste management, demonstrated better performance compared to YOLOv4, achieving higher mean average precision (78.4% vs. 45.3%), faster inference speed (2.72 frames per second vs. 1.33), and a reduced smaller size (117 MB vs. 257 MB) (Lin, 2021). Furthermore, a YOLO network integrated with IoT devices was utilized within an intelligent MSW management system, enabling efficient waste detection and classification in real time (Ghatkamble et al., 2022). Another customized YOLO variant, termed Skip-YOLO, was specifically designed for domestic garbage detection, achieving a 22.5% increase in accuracy and an 18.6% increase in recall compared to YOLOv3 (Lun et al., 2023). YOLOv5s models have also been used for real-time garbage detection (Jiang et al., 2022). Newer iterations, such as YOLOv8 and YOLOv9, have introduced advanced functionalities and achieved improved performance metrics. However, earlier versions like YOLOv5 remain highly relevant, as they often provide greater stability and, in some cases, superior performance in resource-constrained environments (Trisna Gelar, 2025).

Variants of YOLO have been integrated with a nature-inspired parameter tuning method, the Kestrel-based Search Algorithm (KSA), to optimize learning rate parameters for waste object classification. Among these, YOLOv3 achieved the highest average precision of 80% on a dataset of 3,171 images spanning eight waste categories (Agbehadji et al., 2022). Similarly, a dataset of 13,000 waste images was developed, and using object detection models such as ResNet and YOLOv5, researchers achieved 73% classification accuracy across 12 waste categories (Ahmed Chowdhury et al., 2022). Hybrid approaches combining ML algorithms, such as ANN and SVM, have also been explored to improve MSW management. A deep learning-based higher heating value (HHV) prediction model was developed to estimate the HHV of MSW from its elemental composition, outperforming traditional methods in error reduction (Jose and Sasipraba, 2022). Collectively, these studies underscore the significance of ML algorithms, particularly CNN based models like YOLO, in advancing MSW characterization. These algorithms enable real-time and accurate waste detection, classification, and segregation, thereby enhancing the efficiency, sustainability, and environmental impact of waste management systems.

Beyond pre-trained YOLO models, other advanced neural network architectures have also been adopted for waste object detection such as Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNNs) (Faisal et al., 2022), Swin Transformers and Detection Transformers (DETR) (Wang et al., 2024; Madhavi et al., 2025). A two-stage neural network architecture, using EfficientDet variants in each stage was designed, where the first stage functioned as the detector and the second stage as the classifier. Trained and evaluated on a benchmark comprising over ten publicly available datasets featuring waste images from indoor, outdoor, and underwater settings, this architecture achieved a classification accuracy of 75% (Majchrowska et al., 2022). Swin Transformers were further used to identify five plastic subcategories such as polypropylene (PP), polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polystyrene (PS) in real-life deployments, attaining a mean average precision of 80% (Wang et al., 2024). Active learning was combined with DETR to prioritize the most impactful unlabeled images for annotation and inclusion in training, eliminating the need to annotate all samples as required by YOLO-based models. This system achieved state-of-the-art performance in classifying kitchen waste while annotating only 80% of the dataset (Qin et al., 2024). More recently, hybrid networks combining Swin Transformers, ConvNext, and spatial attention mechanisms successfully classified waste into 12 categories from a dataset exceeding 15,000 images (Madhavi et al., 2025).

In recent years, advanced MRFs have started using advancements for real-time characterization and sorting recyclables to increase the efficiency of sorting. These advancements include high-resolution visual cameras for identifying brown grade and multicolored papers (Ken Mcentee, 2018), robotic arm-based collection and sorting integrated with optical sorters, use of ballistic separators in place of screen for sorting papers (Satav et al., 2023), use of hyperspectral cameras in integration with NIR technology for contamination detection or identifying complex multi-layered objects (Tao et al., 2023).

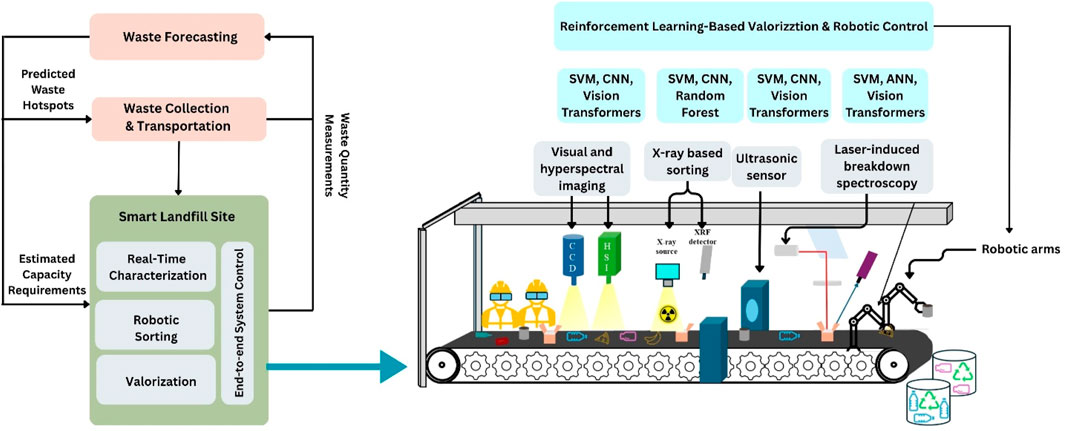

Few MRFs in the US have upgraded their recycling facilities by integrating X-ray based sorting and ultrasonic sensors for real-time monitoring and differentiating between materials based on their density or composition (Zhao and Li, 2022). Figure 6 highlights the automation framework along with technological components of cutting-edge technologies, to enhance recycling operations. Cameras are used for capturing RGB images in the visible light spectrum, while hyperspectral cameras provides both spatial and spectral information of each pixel in a sample across a wide range of the spectrum. X-ray sensors in dual energy mode are used for in-depth analysis and high sorting efficiency. Ultrasonic sensors are used for real-time material sorting by separating the objects based on their density and identifying internal defects in waste objects. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) is another technique used for recovering different types of plastics and aluminum alloys from mixed waste streams. The robotic arm is designed for the collection and separation of waste and typically involves a vacuum gripper for holding lightweight objects, plastic films, paper, and mechanical fingers for grasping heavy or irregular-shaped objects. These innovations contribute to the progress towards achieving SDG 9, as they modernize the infrastructure and strengthen waste management practices.

Figure 6. Schematic illustration of industrial level automation systems for real time characterization, separation and monitoring of MSW streams.

3.3.1 AI based electronic waste (E-waste) characterization and metal recovery

In the United States, approximately 6.9 million tons of e-waste are generated annually, equivalent to nearly 46 pounds per person each year (World Economic Forum, 2023). Although the existing recycling system recovers part of this stream, a significant fraction remains nonrecycled, including residuals from MRFs, and ultimately ends up in landfills. While collection rates have improved in recent years, a substantial share remains unaccounted. For example, only 56% of e-waste in the United States was collected in 2022, leaving the remaining fraction either informally processed or disposed of with general MSW in landfills (Global E-waste Monitor, 2024). Residual waste streams from MRFs often contain electronic components or fragments that cannot be recovered due to contamination, size or mixed composition (Bradshaw et al., 2025). These residuals, along with nonrecycled fraction, contribute not only to landfill burden and environmental risk such as leaching of heavy metals and toxic materials but also represent lost opportunities for recovering valuable materials (Ankit et al., 2021). The rise in e-waste generation is outpacing the increase in formal recycling by a factor of nearly fiver (Baldé et al., 2024). To fully assess the potential of AI-based characterization and metal recovery, it is essential to include these nonrecycled and residual e-waste flows in analyses. This is particularly important given that e-waste accounts for almost two-thirds of the heavy metals present in landfills, underscoring the urgent need for detailed characterization of its elemental composition to enable efficient recovery of metals, critical minerals, and rare earth elements (REEs). On average, e-waste consists of 30% organics, 30% ceramics and 40% inorganics (Debnath et al., 2018). The inorganic fraction includes base metals such as aluminum, copper, iron alongside hazardous heavy metals such as cadmium, zinc, mercury and lead which shows its highly complex nature along with wide range of plastics, ceramics, glass and different metals (Tansel, 2017). This highly heterogeneous composition, further complicated by plastics, ceramics, and glass, makes accurate and scalable characterization challenging. Conventional analytical methods often fall short in addressing this complexity, which has accelerated research into AI-based approaches for quantitative assessment and predictive modeling.

AI techniques have emerged as powerful tools to enhance material identification, optimize recovery processes, and promote sustainable recycling pathways. These advancements align closely with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 on responsible consumption and production and SDG nine on industry, innovation, and infrastructure. For instance, AI frameworks such as response surface methodology, genetic algorithms, computer vision models, predictive modeling, and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS) have been successfully applied to predict and optimize copper recovery from printed circuit boards (Choubey et al., 2020). Such methods demonstrate the capacity of AI to bridge process modeling and experimental optimization, providing actionable insights for large-scale implementation.

Recent studies show how AI can support real time recognition of mixed MSW streams. In a related study, a CNN based deep learning model for real time classification of mixed MSW fraction including metal, plastic and glass was used directly on conveyor belts. Although the study focused on general MSW, the conveyor-based framework is highly relevant to residual streams in MRFs where non-recycled E-waste fragments are often present. The study achieved 97.5% accuracy which was better than models such as YOLOv3 and Random Forest (Li and Chen, 2023). Similarly, Sarswat et al. specifically targeted E-waste and developed a YOLOv7-based model capable of detecting copper, PCBs, plastics, steel, aluminum, and glass with a mean average precision of 0.96. While tested on dedicated e-waste datasets rather than mixed MSW, the approach illustrates how AI can precisely identify valuable components within e-waste fractions (Sarswat et al., 2024).

AI also plays a central role in the automated sorting and classification of e-waste. A hybrid deep learning framework integrating EfficientNet, MobileNet, and sequential neural networks was recently proposed, trained on a dataset of approximately 3,800 images spanning twelve e-waste categories (e.g., circuit boards, batteries, mobile devices, printers, speakers, keyboards, televisions, and computers). This system achieved an impressive accuracy of 98%, outperforming standalone models such as YOLOv8 (Oise and Konyeha, 2025). Similarly, deep learning classifiers combined with dynamic optimization algorithms, employing feature extraction and federated training achieved an efficiency of 98.9%, significantly higher than conventional deep learning baselines (Selvakanmani et al., 2024). These hybrid approaches highlight the scalability of AI-driven classification frameworks for real-world recycling applications.

AI-driven predictive models have also been applied to optimize metal recovery. ANNs and boosting algorithms have been used to model copper recovery through hydrometallurgical leaching, accounting for key parameters such as acid concentration, oxidant volume, solid–liquid ratio, and reaction time. These models achieved up to 94% copper recovery under optimized conditions (Srivastava and Shrivastava, 2025). In parallel, ANFIS approaches demonstrated nearly 88% recovery, with a prediction error of only 6%, outperforming conventional technologies and underscoring the ability of AI to reduce experimental burden and improve reproducibility (Srivastava and Dhaker, 2024).

Computer vision-based methods further complement material recovery by enabling precise recognition of electronic components. For example, the YOLOv5 framework, coupled with hierarchical algorithms, achieved a detection precision of 95% for circuit board components, representing a 38% improvement over baseline YOLOv5 performance (Chen et al., 2022). These improvements in recognition accuracy are critical for the automated dismantling and selective recovery of valuable materials from complex assemblies. Beyond recycling, innovations are emerging at the materials design stage, where AI and bio-inspired approaches are used to enable preemptive recyclability. For instance, recyclable solid-state lithium-ion conductive nanomaterials have been developed via molecular self-assembly using non-covalent interactions (Cho et al., 2025). These materials provide a blueprint for the next-generation of electronic devices, where end-of-life recovery is designed into the material itself.

3.3.2 Role of visual and hyperspectral imaging in MSW characterization

Characterizing and classifying materials within the solid waste stream is a critical first step in effective handling, disposal and valorization of waste for high-value products, thereby supporting the principle of a circular economy (Hoang et al., 2022). Visual imaging and HSI are valuable tools for real-time, non-destructive detection and sorting of materials from MSW (Manopapapin et al., 2024). Visual imaging facilitates the detection of key characteristics such as color, shape, and surface texture of an object. This imaging technique has been successfully applied for identifying materials like bottles, cans, and electronic boards. Visual images are further used as a tool for computer vision models to develop an ML model for the detection and classification of various materials (Vrancken et al., 2017). For instance, sorting of poly-coated plastic bottles using machine vision technology was done based on specular components, rather than the shape and size of the object (Nawrocky et al., 2010). Furthermore, analyzing the particle size distribution of objects within MSW stream is important for assessing the physio-mechanical properties and flowability of waste, which is essential for its transportation and handling (Chang and Chung, 2012). Computer vision technology has significantly advanced in recent years, enabling the automation of waste-sorting processes, significantly improving efficiency. For example, a deep learning multi-modal approach using data from RGB and multispectral sensors was used to detect plastics and wood waste. The YOLOv8 model, trained using data from seven types of plastic and oak wood samples, achieved an impressive 95% accuracy for most classes of materials (Konstantinidis et al., 2023). RGB images of approximately 27,000 discarded garments were utilized to develop a garment classification model, successfully employing CNNs to train the dataset (Tian et al., 2024).

Unlike visual imaging, HSI leverages the principle that different materials reflect, absorb, and emit light in distinct ways across various wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum. By capturing multiple spectral bands, HSI generates a detailed hyperspectral cube for each pixel in the image (Sun and Hsiao, 2024; Salas et al., 2025). Unlike traditional cameras, which typically capture images in only RGB, HSI systems provide a much broader range of data, typically covering wavelengths from the visible to the infrared spectrum. This allows for the detection of subtle differences in materials that are often invisible to the naked eye. HSI, non-destructively characterize and sort MSW in real-time, enhancing material valorization. For example, materials such as ceramic glass, which are difficult to sort using traditional methods, can be sorted effectively using HSI, due to its unique spectral peaks (Serranti et al., 2010). In addition, HSI systems can be used to identify plastic resin in waste with an efficiency of 99%, making it a powerful tool for improving recycling efficiency. This technology can also be employed for identifying natural fibers from synthetic ones in the textile industry (Huang et al., 2022). HSI, along with ML models, offer rapid characterization and contamination detection of materials within MSW, which is critical for producing high-quality, conversion-ready feedstocks for valorization. The effect of liquid contamination, such as water, oil, and various leachates, on end-member spectral signature has also been investigated, where it was found that water contamination caused a nonlinear decrease in reflectance, while oil contamination exhibited no clear alteration rule. Detection of contamination on glossy surfaces was found to be difficult due to the shiny surface (Lan et al., 2024).

HSI is now being used beyond sorting, e.g., to identify impurities and the quality of feedstock of secondary plastics, enabling the development of a real-time, low-cost system that improves recycling yield and quality. This could pave the way for the application of quality-inspection-control-strategies-logics (QICSL) in the solid waste management sector (Bonifazi et al., 2025). Principal component analysis (PCA) of the HSI spectra has been shown to be effective in detecting and localizing impurities in the waste stream (Serranti et al., 2010). Visual imaging and HSI techniques, combined with spectral unmixing algorithms, enhance waste characterization through extraction of representative endmembers (Salas et al., 2025; Thiyagarajan et al., 2025). This supports better decision-making in waste management processes and optimizes material recovery in recycling operations.

In addition to material sorting, HSI can also be employed for real time monitoring and management of landfills and can assist with remote sensing for quantitative analysis. Airborne HSI can aid in contamination detection and monitoring (Ottavianelli et al., 2005). Furthermore, HSI can be used to detect illegal or improper MSW disposal sites. Earth observation (EO) satellite, equipped with HSI technology and other accessories and sensors, can give valuable information for remote sensing and detection of MSW. Visual images captured by the EO satellite can be analyzed by humans to assess the extent and spatial distribution of disposal sites. These images can be used to measure their surface area and volume growth over time and detect mismanagement such as illegal dumpsites. Computer vision techniques, based on both visual and HSI, can be applied for multi-label classification, object-based classification, and segmentation. However, a standardized database for MSW detection and monitoring, which covers the complexity and heterogeneity of solid waste, is still lacking (Fraternali et al., 2024).

3.4 AI for MSW sorting

Once the waste is classified, it needs to be physically separated and sorted into distinct streams, by category, for further processing. Enhancing the efficiency of this MSW separation is a critical aspect of modern waste management. Traditional methods of waste sorting, often reliant on stationary sorting plants and specialized trucks for waste compaction during transportation, have drawbacks in terms of process complexity and reduced sorting effectiveness. For example, compaction can cause cross contamination between food waste and recyclables such as paper and plastics, lowering recovery rates and purity of sorted materials (Arina et al., 2019; Goutam Mukherjee et al., 2021). To address these challenges, the adoption of AI-driven sorting technologies, ML algorithms and computer vision systems has been proposed as a promising solution. By automating the sorting process, ML and AI-driven technologies accelerate waste separation, leading to increased separation efficiency (Chen, 2021).

An important advancements at MRFs is the integration of AI systems to accurately identify and separate different types of materials in MSW in real time. These systems, trained on extensive datasets, ensure that each material is directed to its specific processing area with high precision. For instance, a CNN-based AI-assisted system was developed to digitalize manual MSW sorting using transfer learning, achieving real-time object identification with an accuracy of 81%. (Aberger et al., 2025). This study emphasized the importance of balanced datasets for effective AI model training, enabling efficient real-time waste sorting. The integration of IoT sensors with sorting equipment at MRFs has further facilitated the development of smart sorting systems that manage recycling operations based on real-time data. These IoT sensors monitor waste composition and volume, providing continuous feedback about processed materials, which is particularly beneficial during sudden changes in waste composition (Olawade et al., 2024).

Recent studies show that recycling rates have improved with AI-enabled sorting systems, which can recognize and separate new materials without requiring significant reconfiguration. This adaptability is especially valuable for MRFs, where waste streams vary daily. For example, AI-driven sensors have enhanced sorting precision by visually distinguishing between similar objects made of the same material (e.g., PET trays versus bottles) (Lubongo et al., 2024). Some advanced MRFs even use AI algorithms to forecast future waste composition based on historical operational data (Lin et al., 2022). Robotics also plays a significant role in MSW sorting, offering opportunities to improve efficiency and precision. In specialized sorting facilities, robots equipped with AI and computer vision capabilities have demonstrated high sorting accuracy. Current trends include physical automation systems that integrate advanced gripping technologies, sensors, and adjustable grasping mechanisms to handle and sort materials based on color, shape, composition, and size (Gal et al., 2021).

By leveraging AI and ML algorithms, these robots can analyze and categorize waste based on parameters such as material composition, shape, color, and size, facilitating precise separation of distinct waste fractions (Koskinopoulou et al., 2021). These technologies aim to increase recycling rates and the purity of recovered materials. Cutting-edge methods, such as laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy combined with ML algorithms, are further accelerating the identification and categorization of diverse waste components (Wilts et al., 2021). Through the automation of sorting, robots enhance the speed and precision of waste separation, leading to increased separation efficiency (Wilts et al., 2021). Agile manipulation and rapidly trainable detectors enable robots to adapt to various waste compositions and manipulate objects efficiently (Kiyokawa et al., 2024).

To increase the effectiveness of waste sorting, the integration of robotics with other technologies is imperative. For instance, embedding radio frequency identification (RFID) tags in individual packaging items allows precise sorting of different types of plastic (Ali et al., 2012). However, this approach might increase packaging costs and require industry wide adoption, which packaging manufacturers may be reluctant to implement despite the technical feasibility. HSI-based cascade detection methods can be employed to detect contaminants in post-consumer plastic packaging waste (Bonifazi et al., 2021). These technologies collectively enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of sorting.

Waste sorting improvement can be addressed at both the household and facility levels. While some studies indicate that residents prefer to undertake waste separation themselves if provided with the option, underscoring their pro-environmental preferences (Czajkowski et al., 2014), in practice single stream collection systems are generally more cost-effective and logistically efficient since they simply collection and reduce household burden This places greater importance on MRFs, where AI- and ML-driven sorting technologies are being developed to achieve high-purity separation from a single commingled stream. Emerging tools such as robotics may have niche application in specific cases, but the main trajectory of innovations lies in enabling efficient centralized sorting (Teplická et al., 2021).

In conclusion, robotics, combined with AI and ML technologies, offers substantial potential for improving the sorting of MSW. By enabling automated waste sorting and accurate material categorization, robots can bolster recycling rates, enhance material purity, and contribute to the circular economy. Furthermore, the amalgamation of technologies such as RFID tagging and HSI increases the accuracy and efficiency of waste sorting.

3.5 AI for waste-to-energy (WtE) conversion

WtE represents a mature field that amalgamates waste management and energy generation. Its core objective is to transform waste materials into practical energy forms, encompassing electricity, heat or fuel (Basak et al., 2023). The integration of AI introduces the potential to elevate the efficiency of waste-to-energy processes, optimizing resource allocation and enabling predictive modeling. One paramount application of AI in WtE revolves around optimizing the energy recovery process within WtE facilities. AI algorithms, leveraging real-time sensor data and processing information, proficiently identify patterns and enhance the operation of diverse equipment and processes within the plant (Salem K. et al., 2023). For instance, AI can optimize the combustion process in waste incineration plants, fostering efficient energy recovery and minimal emissions (Sharma and Vaid, 2021).

Furthermore, AI contributes to the optimization of biofuel production from waste materials. For example, in hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass, a machine learning based decision support system was trained on 400 samples and tested on 20 test datasets to optimize process parameters such as temperature, catalyst loading, carbon and hydrogen content and lower moisture, ash and oxygen. The experimental validation matched with the prediction, achieving 94% accuracy (Gopirajan et al., 2023). Continuous analysis and adjustment of process parameters by AI results in improved energy recovery efficiency and a reduced environmental footprint in WtE processes.

Another critical facet where AI plays an indispensable role is in the modeling of waste composition and heating value where multiple nonlinear regression models were developed to estimate the high heating value of MSW. The best performed model achieved R2 of 0.919 using ultimate analysis data (Amen et al., 2021). ML models can predict the higher heating value of MSW by scrutinizing various waste characteristics, including composition and moisture content. This predictive capability facilitates more effective utilization of waste feedstock in WtE facilities, ultimately enhancing energy production.

Several data-driven studies highlight the role of AI in WtE conversion. Data driven platforms have also been applied directly to WtE facilities. Operational optimization and control within WtE plants are substantially fortified by the implementation of AI and ML in adherence to Industry 4.0 principles which focus on the integration of cyber-physical system, IoT, real time data analytics and automation to create smart industrial processes. These technologies facilitate real-time data analytics for plant operations monitoring and optimization. Consequently, they lead to heightened energy recovery efficiency, reduced downtime, and an overall enhancement in plant performance.

WtE is conventionally practiced as mass-burn combustion, where mixed MSW is directly incinerated for energy recovery. However, emerging technologies, such as gasification, pyrolysis, methanolysis are increasingly being explored, and AI techniques are playing a key role in their development. Gasification can undergo substantial improvements with AI, for example, in one study, neural network techniques significantly improved the performance of gasifiers, showing prediction accuracy with R2 0.99 for forecasting gas composition trends. The waste material such as coal bottom ash was used as a catalyst (Shahbaz et al., 2020). This enhancement results in cleaner syngas production, which can be harnessed for energy generation. Additionally, AI has been applied successfully to convert waste peanut shells into liquid biofuel, wherein researchers employed a hybrid methodology incorporating ANNs and GAs to model and optimize methanolysis, achieving higher product yield of 17.61% (Li et al., 2020). A system integrating Industry 4.0, cloud computing, big data analytics and soft sensors were used to predict syngas heating value and flue gas temperature using partial least squares regression, principal component regression and neural networks. The study further established the value of data-drive soft-sensors as alternative tools for predictive analysis, in scenarios where real-world process knowledge is scarce (Kabugo et al., 2020).

Machine-learning based data-driven studies for waste utilization can be segregated according to the targeted process (such as waste combustion or gasification, pyrolysis, anaerobic digestion) and specific goal of either prediction or optimization. The data sources considered in these studies vary from real-world feedstock composition data and sensor-based process environmental measurements to external knowledge databases and research articles. Studies have predicted the calorific value of mixed waste streams before combustion, based on feedstock composition data (Kumar and Samadder, 2023). Going one step further, the combustion process was controlled to maximize energy recovery while minimizing emissions, by utilizing real-time operation data of furnace temperature, oxygen levels, air-to-fuel ratio, and flue gas composition (Tang et al., 2024). Similar predictions and optimization approaches have been studied for pyrolysis and anaerobic digestion. In pyrolysis, AI models have been used to predict syngas and biogas yields based on feedstock characteristics and to optimize reactor parameters for maximum fuel output (Bu et al., 2025). The methane generation potential of anaerobic digestion was predicted based on feedstock data such as food waste composition, pH, and nutrients (Jeong et al., 2021; Mougari et al., 2021; Yildirim and Ozkaya, 2023). Anaerobic digestion process conditions, such as digester pH, retention rate, and loading rate, were controlled for maximizing methane yield (Ling et al., 2024). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that data-driven AI approaches provide measurable gains in predictive accuracy, process control, and energy recovery across diverse WtE pathways.

In the context of waste incineration, researchers have developed a surrogate reaction mechanism to predict gas composition and pollutant formation during waste incineration. This comprehensive model accounts for the decomposition of waste components and the formation of tar, gases, and char, providing valuable insights for optimizing incineration processes (Netzer et al., 2021). Furthermore, waste combustion control and prediction using AI has garnered substantial attention within the WtE field. These technologies facilitate the optimization of combustion processes by dynamically adjusting parameters to maximize energy production while minimizing emissions.

SVMs and random forests have also been utilized to analyze historical data and develop models for optimizing the combustion process (Wilts et al., 2021). These models consider variables like waste feed rate, airflow, and furnace temperature to make real-time adjustments, ensuring optimal combustion efficiency and emission reduction. To enhance the accuracy of waste combustion control predictions, data from multiple sources can be integrated. Historical data on waste composition, combustion parameters, and energy production can be combined with real-time sensor data from the combustion system. This holistic approach enables more comprehensive and precise predictions, leading to better control and optimization of the combustion process.

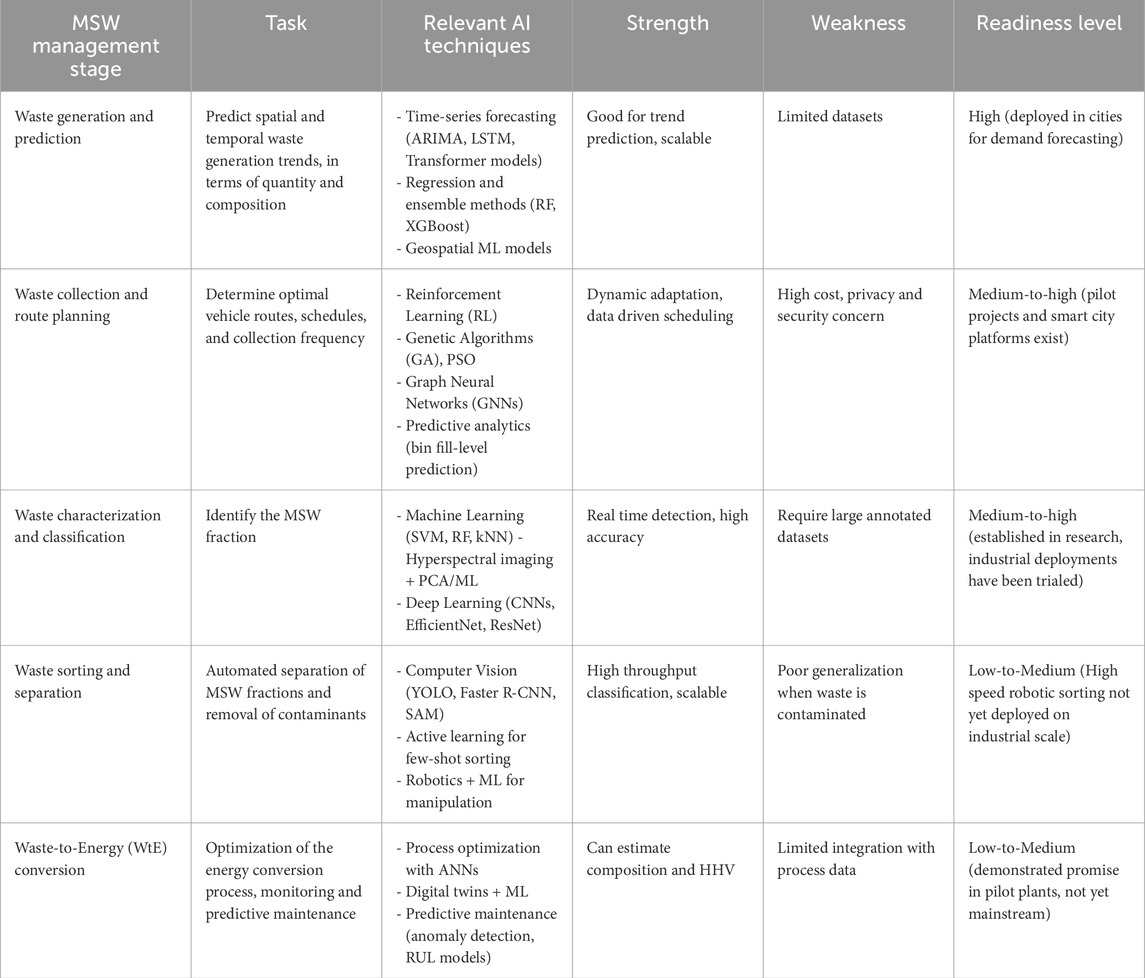

Waste combustion control through AI can be complemented by composition analysis and characterization, which provide valuable inputs for combustion control models by considering the energy content and composition of different waste streams (Patel et al., 2023). This allows models to optimize the combustion process based on the specific characteristics of the waste being processed. To summarize the diverse application discussed above, Table 1 shows the comparative framework mapping AI techniques to different stages of MSW management. The table discusses technology readiness levels, specific task performed and strength and weakness of each approach.

Table 1. Overview of AI Applications in MSW Management: stages, readiness levels, strength and weakness (Abbasi and El Hanandeh, 2016; Kabugo et al., 2020; Lin, 2021; Faisal et al., 2022).

4 AI deployment challenges in MSW management

4.1 Data availability

The application of ML algorithms in MSW characterization, as discussed above, presents several critical aspects that need to be analyzed. These aspects include the challenges posed by datasets with no contamination, class imbalance, model overfitting, and the absence of multilabel objects (Xia et al., 2022). Training AI/ML models for waste management requires availability of comprehensive and standardized datasets. However, existing datasets suffer from limitations.

First, there is a lack of uniformity in data collection practices, leading to inconsistencies across studies. Second, class imbalance is common, with certain categories (e.g., plastics, paper) being overrepresented while others (e.g., hazardous waste) remain underrepresented. Third, visual data often contains noise and variability caused by factors such as lighting, background contamination, and camera angle during image acquisition of waste objects (Yevle and Mann, 2025). Datasets without contamination, as encountered in waste management, can hinder the robustness of ML models. The absence of real-world variations, such as different lighting conditions and diverse waste compositions, might lead to models that perform well only in controlled environments (Qiao et al., 2023).

Fourth, model generalization across environments remains a major challenge. AI systems trained under controlled or static conditions often fail in real-world sorting facilities, where waste items may be dirty, torn, occluded, or presented under inconsistent lighting and fifth AI models require large, diverse, and well-annotated datasets to perform reliably, yet such datasets are scarce (Ahmad et al., 2025). In addition, datasets particularly for tasks like predicting generation rate and composition are scarce. Much of the data used in previous studies is either inaccessible or not publicly shared, hindering reproducibility and the development of multiple AI models (Abbasi and El Hanandeh, 2016).

The available data such as TrashNet (Aral et al., 2018) are insufficient for training deep neural networks without augmentation or transfer learning, resulting in overfitting when applied to large architectures like CNNs. Other datasets, including Trash Annotations in Context (TACO), exhibit strong bias, offering only narrow range of categories or the distribution across the categories is highly skewed due to bias towards frequent categories (Das et al., 2023). Although these benchmark datasets have driven early progress, their limited scale and bias toward certain categories raise concerns about reproducibility and generalizability. Furthermore, high-quality annotations for labelling waste objects/images are rarely available in conventional datasets, making it difficult to recover material from the MSW stream (Gautam and Arashpour, 2025).

This could be due to the fact that waste characterization studies conducted by the counties typically report aggregated data under broad material categories, rather than detailed, high-resolution composition required for robust model training. This low granularity limits the usefulness of such datasets and leads to overfitting in deep learning models. With small or non-diverse training data, models are more likely to memorize examples rather than learn generalizable features, while class imbalance further skews recognition toward dominant waste types (Xia et al., 2022; Grassel et al., 2025). Such shortcomings reduce performance in real-world applications, where MSW streams are diverse and dynamic. With complex models like YOLO and CNNs, there is a risk of capturing noise and irrelevant patterns present in the training data, resulting in reduced generalization to unseen data (Yevle and Mann, 2025). Another limitation is the absence of multilabel objects in waste datasets, which can limit the model’s ability to handle scenarios where multiple waste types are present within the same image (Olawade et al., 2024).

Mitigation strategies include data augmentation (e.g., rotation, flipping, cropping, color jittering) which can artificially enhance dataset diversity and improve model adaptability without frequent retraining (Yevle and Mann, 2025). Although techniques like transfer learning, class weights, and data augmentation have been used to solve this problem, imbalanced data without careful handling can still lead to skewed model prediction and reduce the overall effectiveness of waste characterization systems (Chen et al., 2024).

Beyond augmentation, advanced learning paradigms provide additional solutions. The data quality issue can be resolved by using semi supervised learning (SSL), weakly supervised learning (WSL) and multiple instance learning (MIL). Domain specific frameworks for data driven AI system design have also been developed as a way to overcome such limitations and better align AI with requirements of waste management (Singh et al., 2025). SSL combines small, labelled datasets with large pool of unlabeled data using techniques like pseudo-labeling and consistency regularization. WSL explores coarse labels such as image-level tags, refined through methods like MIL and attention mechanisms to improve classification (Yevle and Mann, 2025).

4.2 Economic barrier and cost implications

The deployment of AI-driven MSW management systems presents significant economic challenges, particularly for municipalities with limited budgets. The primary barrier is the high initial capital expenditure required for hardware (e.g., cameras, sensors, robotics), IoT-enabled monitoring networks, supporting infrastructure, cloud services, and workforce training. This cost not only discourages adoption, despite potential long-term savings from operational efficiencies and reduced disposal costs but also delays the transition to more sustainable and cost-effective waste management practices. Overcoming these financial constraints is critical for municipalities to realize the environmental, economic, and social benefits offered by AI-enabled waste management technologies (Lakhouit, 2025).

Workforce implications are also critical, as automation may reduce manual sorting needs but simultaneously create opportunities for reskilling in system management and oversight roles. Practical implementation of such models demonstrates both the opportunities and limitations of such systems. For example, a case study in Australia showed that AI-enabled monitoring eliminated reliance on sparse manual audits by providing real-time, full-stream coverage improving decision-making granularity. Cost optimization was achieved by targeted interventions, such as education or warnings to persistent contamination hotspots, reducing truck traffic, and manpower expenses.

Although these initial investments in digital infrastructure, hardware integration and personnel training are substantial, the system yielded cost optimization and improved compliance, suggesting a favorable long-term return on investment (Yevle and Mann, 2025). Despite these promising outcomes, the economics for AI based MSW management are still in the nascent phase. Current estimates of cost benefit are limited, with most evidence derived from small-scale pilots rather than long-term deployments.

4.3 Policies and socio-economic constraints

AI models can effectively forecast regional waste trends and predict suitable sustainable strategies such as recycling and waste-to-energy conversion (Gupta et al., 2019). Predictive performance improves when socioeconomic indicators such as income levels, population density, and consumption behavior are incorporated into modeling frameworks. Integrating these variables with time series analysis improves forecasting accuracy helping policymakers in technology selection, collection logistics, and waste treatment strategies (Rimaityte et al., 2012). Evidence also suggests that cities exceeding the expected MSW performance for their socioeconomic level highlight opportunities to overcome systemic inefficiencies and unlocking broader development potential across urban governance sectors (Velis et al., 2023).

However, disparities in socioeconomic conditions and data availability limit the effectiveness of AI solutions in many regions. Regions with limited data or inadequate technological infrastructure face reduced benefits, emphasizing the need for context-specific model adaptation. Apart from technical barriers, the broader deployment of AI-driven MSW management is hindered by the absence of formal policies and regulatory frameworks, with existing efforts in digital oversight and compliance still in early stages (Alsabt et al., 2024).

For example, recent legislation in New York State requires public disclosure of AI use in state agencies and restricts certain applications such as automated eligibility decisions unless subject to consistent human monitoring (Office of the New York State Comptroller, 2023). Although this legislation represents an important step toward transparency, it remains generic and does not address sector-specific requirements of MSW management, such as data privacy for household-level consumption patterns. Privacy and security issues also complicate the adoption. Data on consumption and MSW generation are sensitive, as there is growing concern about the risk associated with the misuse of sensitive data of residents (Lakhouit, 2025).

These initiatives represent initial steps toward regulating AI in public services, but comprehensive frameworks are still lacking. This can also help in gaining the confidence of the people for building trust with the municipalities. Establishing clear policy guidelines and regulatory oversight will be essential to ensure that AI-driven waste management systems are implemented responsibly, equitably, and sustainably, directly aligned with SDG 10 (reduced inequalities).

The deployment of AI in MSW management is constrained by several factors: limited and biased datasets, insufficient variability in available data, high implementation costs, uncertain return on investment, and the absence of comprehensive regulatory frameworks. Addressing these obstacles through collaborative data-sharing initiatives, development of diverse and standardized datasets, adoption of advanced learning strategies, economic assessments, policy support and interdisciplinary integration will be critical for realizing AI’s transformative potential in sustainable MSW management.

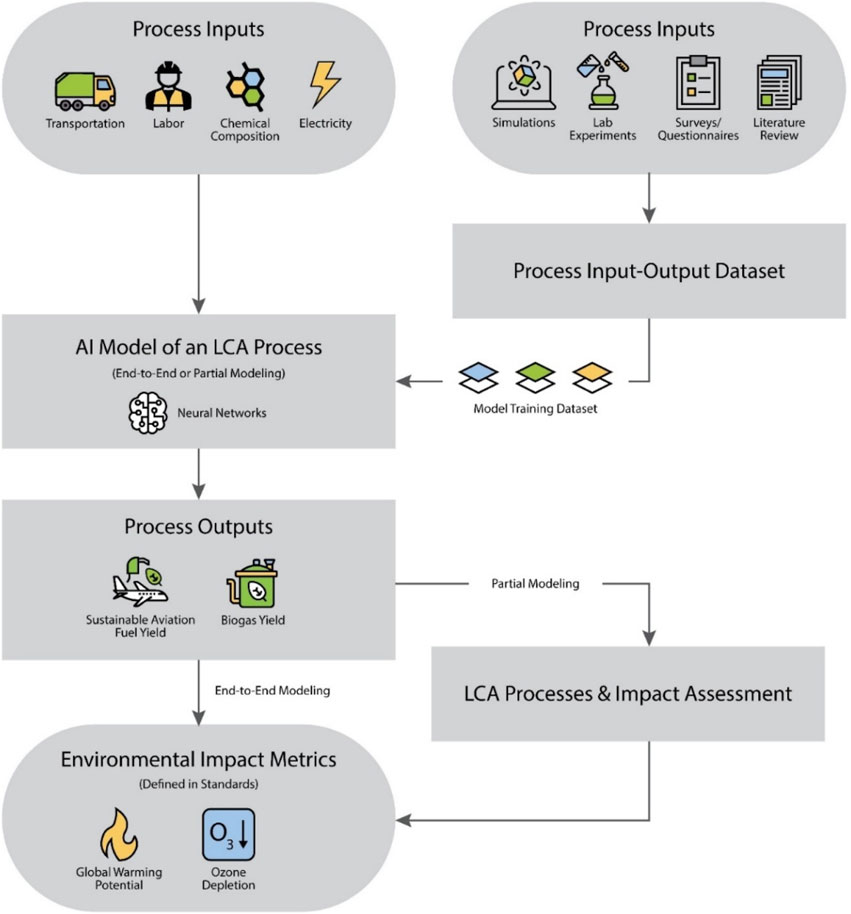

4.4 Circular economy