- 1 Economic and Technological Research Institute of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd., Hefei, China

- 2 Anhui Mingsheng Hengzhuo Technology Co., Ltd., Hefei, China

Under the guidance of the “dual carbon” target, rural distribution systems are increasingly affected by power fluctuations and voltage violations owing to the growing penetration of distributed photovoltaic (PV) generation. To address these issues, we propose an optimization planning method for rural distribution systems by considering on-load tap changers (OLTCs), energy storage systems (ESSs), and auxiliary flexible interconnection devices such as soft open points (SOPs). Accordingly, we developed a two-level optimization model: the upper level minimizes the total planning and operational costs by determining the optimal deployment of OLTCs and ESSs under technical and economic constraints; the lower level evaluates the system reliability by calculating the expected energy not supplied (EENS) based on the fault impact matrix (FIM) while ensuring network connectivity and exclusive transfer paths. We also propose an iterative strategy to solve the two-level optimization model, where the planning decisions of the upper level and reliability evaluation solutions of the lower level interact until the convergence condition is satisfied. The framework of the iterative strategy was implemented in the AMPL modeling tool along with the Gurobi solver to ensure computational efficiency. The simulation results indicate that the proposed method achieves 100% PV accommodation, reduces the EENS by over 50%, and reduces the power system costs by approximately 16%, thereby improving both the economic performance and reliability effectively.

1 Introduction

Under the “dual carbon” strategy, the increasing penetration of distributed photovoltaic (PV) generation in rural areas has become a key challenge that restricts low-carbon transition of the distribution networks (Schum and Lin, 2012). The inherent randomness and volatility of PV generation significantly intensify the fluctuations in the net load. Moreover, the traditional radial network structures expose other limitations such as insufficient supply margins, reverse power flow, and voltage violations under multisource operation scenarios (Lin et al., 2023). To address these issues, flexible interconnection technologies based on intelligent soft open points (SOPs) have been demonstrated to offer notable advantages via reconfiguring the network topology through multiterminal power transfer, thereby improving the power balance between supply areas and enhancing the integration of renewable energy (Ji et al., 2019). However, relying solely on SOPs cannot fully mitigate the renewable energy fluctuations; hence, energy storage systems (ESSs) with fast responses and energy-shifting capabilities have become essential for enhanced resilience and economic efficiency of distribution networks (Guo et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2024).

Flexible loads, owing to their adjustable characteristics, can dynamically shift energy consumption in terms of quantity, duration, and timing. This flexibility enables them to optimize load profiles, reduce peak-valley differences, enhance system economy, and alleviate energy supply-demand imbalances. Regarding flexible load research, an irrigation load model that was treated as reserve capacity was established in reference (Cheng, 2021), while delayable load scheduling strategies were designed in reference (Ravikumar et al., 2022). In reference (Fu et al., 2024), an energy-carbon synergy optimization method for agricultural microgrids was proposed by establishing carbon flow and greenhouse load models to reduce costs and emissions. A bi-level optimization model for facility agriculture loads and energy systems based on crop growth mechanisms was developed in reference (Fu et al., 2024). In reference (Li et al., 2025), a two-stage stochastic scheduling method for multi-energy rural microgrids considering biomass fermentation and irrigation systems was introduced. Furthermore, in reference (Zhang et al., 2025), a coordinated energy-carbon management mechanism for agricultural integrated energy systems through electricity-carbon trading was formulated. In summary, although existing studies have advanced the coordination of agricultural flexible loads and energy systems, most have focused on load scheduling or microgrid scenarios, lacking joint optimization with distribution network regulation resources, such as SOPs, ESSs, and on-load tap changers (OLTCs). This limits the full utilization of load flexibility and hinders effective management of high PV penetration in rural areas.

As fast-response and energy-shifting technologies, ESSs have been widely used to mitigate renewable energy fluctuations while enhancing system flexibility and economic efficiency (Peng et al., 2023). In this context, several authors have explored the role of long-term energy storage in improving the temporal flexibilities of energy systems (Pan et al., 2020; Li et al., 2023; Li et al., 2018). Seasonal hydrogen storage within a power-to-hydrogen framework under high renewable integration was explored by Pan et al. (2020), while the computational challenges of long-term scheduling were addressed by Li et al. (2023) through efficient decomposition and decoupling methods. Li et al. (2018) developed a multilevel coplanning framework for active distribution networks by integrating investment and operational scheduling across multiple timescales. Wei et al. (2022) and Qiao et al. (2025) studied the applications of ESSs in enhancing system adaptability under uncertainties. A reserve capacity model that supported demand-side emergency scheduling was proposed by Wei et al. (2022). Qiao et al. (2025) incorporated source–load uncertainties and metaheuristic optimization to improve PV integration and voltage stability. Additionally, the efficacies of ESSs in frequency support and inertia responses were validated by Qian et al. (2022) through a trajectory-based control strategy, further expanding their roles in dynamic grid operations.

Flexible interconnection devices such as SOPs play supporting roles in enhancing the flexibility of a distribution network. Pamshetti et al. (2023) and Pamshetti and Singh (2022) proposed two-layer coordinated optimization frameworks considering SOPs with distributed energy resources or storage systems. Jiang et al. (2022) presented a comprehensive review of SOP technologies and applications, while Saaklayen et al. (2023) and Tao et al. (2023) investigated multiscenario or robust optimizations for SOP siting and sizing. Furthermore, Diao et al. (2025) addressed the joint planning of multiport SOPs and storage systems. However, most of the above studies have focused on static SOP planning and often neglected integration with ESSs, flexible loads, and OLTCs.

Some authors have presented simplified methods based on topology and information link characteristics for reliability assessments (Xiang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2020). Furthermore, Jooshaki et al. (2020) and Li et al. (2020) explored optimization-based reliability models by considering the topology variables and device operations. The scope of these works was further extended by other researchers (Cheng et al., 2020; Yin et al., 2023; Wei et al., 2019; Timalsena et al., 2021), who have addressed electric vehicle uncertainties, storage scheduling, AC/DC hybrid networks, and circuit breaker failures. However, most of these studies focus on urban grids and lack systematic models for evaluating the reliability impacts of flexible interconnections and energy storage in rural distribution systems.

Thus, in this work, we propose an integrated planning method for rural distribution systems that jointly considers the deployment and regulation of ESSs, OLTCs, SOPs, and rural-specific flexible loads. The proposed method incorporates reliability indicators, such as the expected energy not supplied (EENS), in a two-level optimization framework with the aim of enhancing the economic performances, operational flexibilities, and supply securities of rural networks under high renewable energy penetration. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

1. A two-level planning framework is proposed for rural distribution systems, where the upper-level model jointly optimizes the siting and sizing of SOPs and ESSs under technical and economic constraints, while the lower-level model evaluates the system reliability based on the fault impact matrix (FIM).

2. PV consumption and voltage regulation are taken into account in the proposed planning model. Accordingly, the simulation results show that PV consumption and voltage regulation can be greatly improved by integrating SOPs, ESSs, and OLTC regulation.

3. The economic factor and reliability index are considered in the proposed upper-level and lower-level models, respectively. Thus, the simulation results show that the proposed method is beneficial in reducing EENS by more than 50% and total system cost by approximately 16% to achieve balance between economic performance and operational resilience.

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the detailed formulations of the two-level planning model and its solution strategy. Section 3 provides an analysis of the numerical results to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. Finally, Section 4 presents the conclusions of this work and outlines some directions for future research.

2 Two-level planning model and its solution strategy

To better capture the interactions between the planning decisions and system reliability, a two-level optimization framework is developed herein. Accordingly, the upper-level model focuses on coordinated planning of the ESSs and SOPs along with auxiliary consideration of the OLTCs to minimize the total costs while satisfying the technical and operational constraints; the lower-level model then evaluates the reliability performance of the system under various planning configurations by calculating reliability indices such as the EENS. The resulting reliability metrics are then fed back to the upper level to guide planning decisions, thereby forming a closed-loop optimization structure.

2.1 Upper-level model

2.1.1 Objective function

The upper-level model aims to minimize the total costs related to the investment and operations of the ESSs, OLTCs, and SOPs under technical and economic constraints, which can be represented by Equation 1:

where

The voltage violation penalty coefficient

where

2.1.2 Constraints

2.1.2.1 Constraint on the investment cost

where

2.1.2.2 Constraints on the nodal power balance

where x

ij

is the reactance associated with line ij;

2.1.2.3 Constraints on the distribution system operation

Here, M is a sufficiently large positive constant used in the big-M formulation;

2.1.2.4 Constraints on the power system security

Here,

2.1.2.5 Operational constraints of the SOPs

Herein, the SOPs are modeled to operate in the PQ control mode under normal conditions along with the transmitted active power and reactive power injection at each terminal being treated as control variables. The constraints are thus formulated to limit the active power transfer while ensuring that the transmission capacity is not exceeded.

where

2.1.2.6 Operational constraints of the OLTCs

Here, k

0 is the rated tap ratio of the stepped winding of the OLTC;

2.1.2.7 Constraints on the flexible agricultural irrigation loads

Here,

In Equation 26, the equality between the procured power at the agricultural nodes and aggregated power consumption over all water delivery paths is enforced. In Equation 27, we show the relationship between the actual power consumption of the pumps and their corresponding water flow rates. In Equation 28, the total irrigation water volume is calculated as the time-integrated sum of the water flow rates. In Equation 29, constraints are imposed on the flow rate limits and pump ramping rate to ensure feasible operation. In Equation 30, we express the coupling between the irrigation water flow rate and associated pump power consumption to the link water demand with electrical energy usage.

2.1.2.8 Constraints on the ESSs

Here,

In Equations 31, 32, the charging and discharging actions are permitted only if an ESS is installed at node i. In Equations 33, 34, the time-coupled energy dynamics of the ESS are formulated such that the energy level is updated on the basis of the previous charging/discharging actions and maintained within the allowable bounds. In Equations 35, 36, the constraints on the charging and discharging power limits are imposed. In Equation 37, mutual exclusivity is enforced so that simultaneous charging and discharging cannot occur. As per Equation 38, the initial and final energies of the ESS are equal.

2.2 Lower-level model

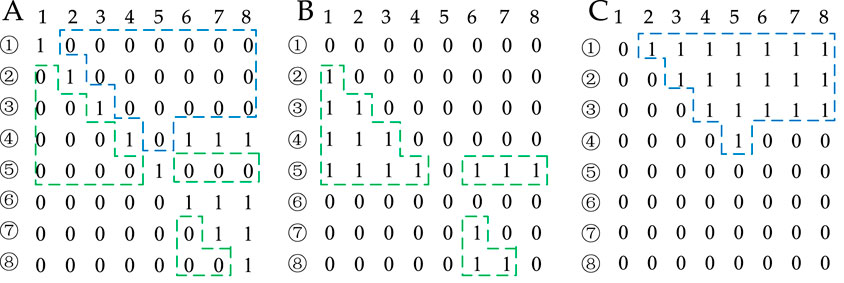

The distribution network structures operating radially can generally be summarized as “M-segment N-linkage switching” reliability calculation units, which allow the FIM-based reliability assessment method to be applied to a wide range of operational conditions in distribution systems. Specifically, the FIM is an associative matrix used to describe the impact of each branch fault event on the load nodes. Here, the rows of the matrix represent the number of branches, while the columns represent the number of load nodes. The FIM can be categorized into three types based on the power supply modes to the load nodes after a fault, namely FIMA, FIMB, and FIMC. In this work, we introduce two fault-induced power supply modes to the load nodes, namely the main network supply and SOP supply corresponding to the FIMB and FIMC, respectively. There are various approaches for improving the EENS. In this study, we specifically adopted the enhancement of system reliability through the SOPs, which can increase the interconnection capacity and enable power exchange among different areas. Accordingly, after fault isolation, if a load node remains without power until the faulty branch is repaired, then that node is classified under FIMA. In FIMB and FIMC, if a load point is supplied by the main power source or the SOP after fault isolation, then the corresponding matrix element is “1”; otherwise, it is “0.” In FIMA, if the load point remains without supply after fault isolation and supply is restored only after the fault is repaired, the corresponding matrix element is “l”; otherwise, it is “0.”

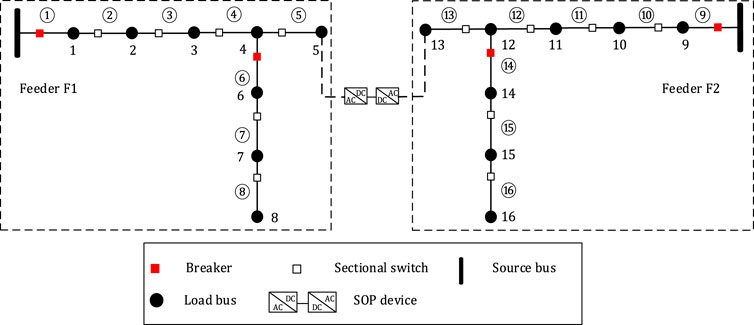

In this study, the system reliability indices are calculated using the method reported by Wang et al. (2018). Taking Feeder F1 in the distribution network shown in Figure 1 as the example, the corresponding FIMA, FIMB, and FIMC matrices are illustrated in Figure 2. In the case of FIMA and FIMB, by configuring the sectionalizing switches on branches ②–⑤, ⑦, and ⑧, certain elements that originally belong to FIMA (with values of “1”) are transferred to FIMB, as indicated by the green dashed boxes. For instance, when branch ④ fails, since there is no sectionalizing switch installed on it, load nodes 1 and 2 will remain unsupplied until the fault is repaired. However, if a sectionalizing switch is installed, these nodes can be isolated from the faulty section and resupplied with the main power source. In this work, the locations of the sectionalizing switches are not optimal, and it is assumed that the switches are preinstalled on the aforementioned branches. Therefore, all corresponding elements in FIMB are set to 1 by default. In the case of FIMA and FIMC, the addition of an SOP allows some elements originally belonging to FIMA to be reassigned to FIMC, as indicated by the blue dashed boxes in Figure 2. Taking the example of a fault on branch ④, if no SOP is available, then load node 5 must wait until fault clearance to be reenergized; with the addition of an SOP here, load 5 can be transferred to another feeder section for supply. However, SOPs are often constrained by capacity limitations in practical cases. Thus, not all elements within the blue dashed box in Figure 2 can be directly considered as “1.” The corresponding elements in FIMC are represented using decision variables that may have additional constraints.

Figure 1. Topological diagram of a modified distribution network with two feeders (F1 and F2) interconnected by a soft open point (SOP).

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the fault impact matrices (A,B) and (C) corresponding to feeder F1 in Figure 1.

The lower-level model focuses on system reliability assessments by considering the fault scenarios, restoration processes, and time-varying load profiles comprehensively. Here, the EENS measured in kilowatt hour per year is adopted as the key reliability indicator and is calculated using the analytically derived expressions from the FIMs. To ensure model feasibility and accuracy, some essential operational constraints are incorporated, including unique restoration paths, SOP capacity limits, and network connectivity requirements.

2.2.1 Objective function

where

2.2.2 Constraints

Here,

2.3 Solution strategy

To achieve an optimal configuration of the ESSs while enhancing the economic efficiency, voltage security, and reliability of a rural distribution network, we propose a two-level iterative optimization framework. Here, the upper-level model determines the key planning decisions, including the siting and sizing of the ESSs and OLTCs, with auxiliary consideration of the SOPs; the lower-level model then evaluates the EENS under a set of predefined fault scenarios by determining whether each load point can be resupplied through one of several feasible strategies, namely branch repair, sectionalizing switch isolation, and SOP-assisted transfer. The lower-level model receives the SOP deployment decisions from the upper level and returns the computed EENS value for inclusion in the upper-level objective function. An iterative solution strategy is thus adopted to coordinate the interactions between the upper- and lower-level models. In each iteration, the upper-level model is solved to obtain a candidate planning scheme; this scheme is passed to the lower-level model to evaluate the reliability performance. The calculated EENS is then fed back to the upper-level objective function, and the process is repeated until convergence is achieved. The condition for iteration termination is that the calculated reliability index meets the requirements. The complete optimization framework was implemented in the AMPL modeling environment, and the mathematical models were solved using the Gurobi commercial solver that provides efficient support for large-scale convex programming problems involved in both models.

3 Results analysis

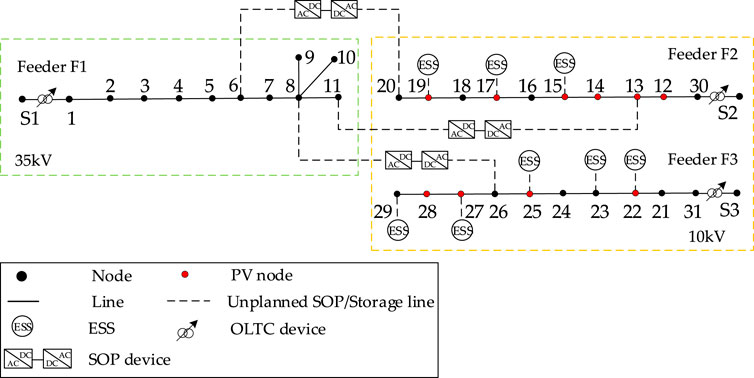

In this study, we used a modified 31-node distribution system to verify the effectiveness of the proposed coordinated planning approach integrating SOPs and ESSs while accounting for the OLTCs and flexible agricultural loads.

3.1 Parameter settings

The topology of the modified 31-node distribution system is illustrated in Figure 3, where S1, S2, and S3 denote the three substations. This system was modified by adding OLTCs in the substations and three candidate SOP locations (6–20, 8–26, and 11–13), in addition to integrating 10 distributed PV units to reflect high-penetration renewable access. The set of voltage levels is given by

3.2 Analysis of the planning results

To assess the proposed coordinated planning method, three comparative cases were designed as follows:

• Case 1: No planning measures are implemented

• Case 2: SOP and ESS planning is carried out without OLTC regulation

• Case 3: SOP and ESS planning is combined with OLTC regulation.

3.2.1 Optimization results

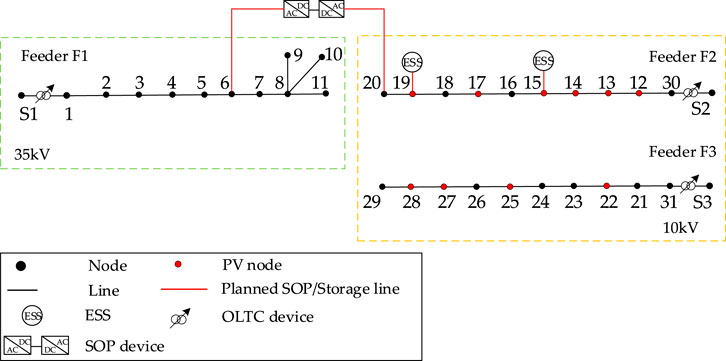

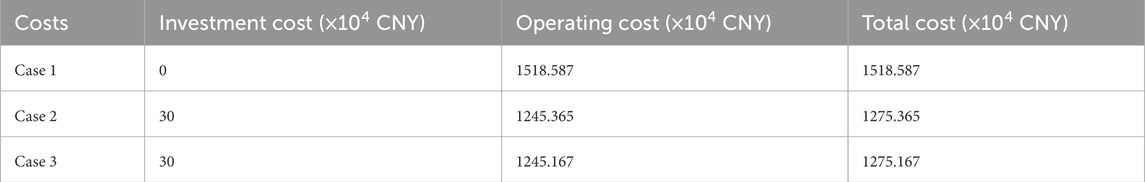

The optimal planning configuration obtained using the proposed method is shown in Figure 5. Here, a single SOP device is installed between nodes 5 and 19 to manage the power flows and maintain voltage balance across different regions. In addition, two ESSs are deployed at nodes 14 and 18 to enhance system flexibility and improve operational reliability. The newly installed SOP and ESS units are highlighted in red in the figure. A comparative analysis of the total costs under different scenarios is presented in Table 1. In Case 1, the absence of investment planning leads to a high operating cost of 15.18587 billion RMB, resulting in significantly elevated overall cost. In Case 2, the coordinated planning of SOPs and ESSs reduces the operating costs to 12.45365 billion RMB, yielding a cost savings of approximately 2.732 billion RMB; this clearly illustrates the economic benefits achieved through optimization-based infrastructure investment. In Case 3, further incorporation of OLTC regulation leads to a marginal reduction in the operating cost to 12.45167 billion RMB and a total cost of 12.75167 billion RMB, reflecting a modest improvement in economic efficiency through enhanced voltage control.

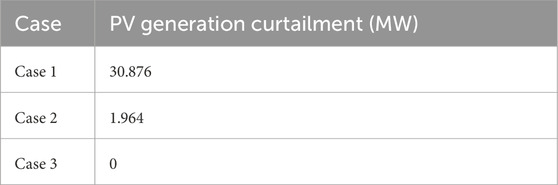

3.2.2 Curtailment of PV generation

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed planning method, Table 2 presents a comparison of PV generation curtailment for the three cases. In Case 1, where no flexible resources are deployed, the system exhibits a substantial PV curtailment of 30.876 MW, highlighting the limited capacities of traditional distribution networks to integrate high proportions of renewable generation. In Case 2, the deployment of SOPs and ESSs significantly reduces the curtailed PV power to 1.964 MW, indicating improved load accommodation capabilities. In Case 3, the introduction of OLTC regulation eliminates PV curtailment, enabling full utilization of renewable generation. These results confirm that coordinated deployment of SOPs and ESSs enhances the renewable energy hosting capacity of the distribution network. Moreover, the integration of OLTC control provides further benefits with regard to voltage regulation. Thus, the proposed method demonstrates practical effectiveness in accommodating high levels of PV integration in rural distribution systems.

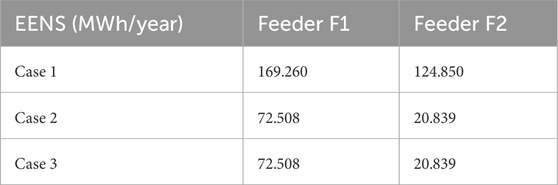

3.3 Reliability assessment

Table 3 summarizes the EENS results under two different planning scenarios at both the 35 kV and 10 kV levels. In Case 1, where flexible resources such as SOPs or ESS are absent, the system exhibits relatively high EENS values of 169.260 MWh/year at the 35 kV feeder and 124.850 MWh/year at the 10 kV feeder. These figures reflect the limited fault-tolerance capabilities of conventional radial topologies, where supply interruptions caused by faults cannot be mitigated efficiently. In Case 2, the coordinated deployment of SOPs and ESSs leads to significant reductions in the EENS values, which decrease to 72.508 MWh/year at the 35 kV feeder and 20.839 MWh/year at the 10 kV feeder. This reduction is particularly evident at the 10 kV level, where the EENS decreases by approximately 83%, highlighting the positive impacts of flexible resources in ensuring supply continuity for rural end-users. Note that the difference between Case 3 and Case 2 lies in the presence of OLTCs. However, both cases result in the same planning outcome, which has no impact on the EENS. These results confirm the effectiveness and practicality of the proposed integrated planning strategy for rural distribution networks.

4 Conclusion

A two-level optimization planning method is proposed for rural distribution systems that integrate ESSs, OLTCs, SOPs, and rural flexible loads within a two-level optimization framework. The simulation results verify the effectiveness of the proposed method, and the following conclusions can be drawn:

1. The integration of SOPs and ESSs significantly reduces PV curtailment and enhances renewable energy utilization. The simulation results show that compared to the case without SOPs and ESSs, the curtailed PV output is reduced from 30.876 MW to 1.964 MW and further eliminated when combined with OLTC control.

2. OLTC regulation effectively enhances the voltage control capacity of the distribution system to enable full absorption of renewable energy without additional investment. The results demonstrate excellent cost-effectiveness under high penetration conditions.

3. The proposed method improves the system reliability and operational flexibility. The simulation results show that the proposed method reduces the EENS by more than 50% at both feeders F1 and F2 as well as the total cost by approximately 16%.

Future research efforts will focus on detailed modeling of the selector and divertor switches of the OLTCs and their applications in the planning model. Moreover, we intend to investigate resilience-oriented planning strategies to address extreme-weather and climate challenges in the future.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Author contributions

XY: Methodology, Writing – review and editing, Conceptualization. YZ: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. FZ: Data curation, Writing – review and editing. RX: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. FJ: Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Writing – review and editing. JX: Visualization, Software, Writing – review and editing, Validation.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work is supported by the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd. (No. B3120924000C). The funder was involved in providing technical guidance and project background information during the research process.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Science and Technology Project of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd for the funding.

Conflict of interest

Authors XY, YZ, FZ, and RX were employed by the Economic and Technological Research Institute of State Grid Anhui Electric Power Co., Ltd.

Authors FJ and JX were employed by Anhui Mingsheng Hengzhuo Technology Co., Ltd.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Cheng, J. (2021). “Capacity evaluation of agricultural irrigation load participating in sustainable power and energy operating reserve of power system,” in 202l IEEE conference (iSPEC). Nanjing, China, 2511–2517. doi:10.1109/iSPEC53008.2021.9735435

Cheng, S., Wei, Z., Shang, D., Zhao, Z., and Chen, H. (2020). Charging load prediction and distribution network reliability evaluation considering electric vehicles’ spatial-temporal transfer randomness. IEEE Access 8, 124084–124096. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3006093

Diao, H., Li, P., Tu, C., and Che, L. (2025). Optimal co-planning of multi-port soft open points and energy storage systems for improving hosting capacity and operation efficiency in distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 40 (1), 459–471. doi:10.1109/TPWRD.2024.3503662

Fu, X., Bai, J., Sun, H., and Zhang, Y. (2024). Optimizing agro-energy-environment synergy in agricultural microgrids through carbon accounting. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 15 (5), 4819–4834. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3397990

Guo, H., Wang, Q., Wang, Y., Liu, S., Tang, L., and Li, L. (2022). “Capacity allocation of energy storage system improving high penetration renewable energy accommodation,” in 2022 5th international conference on power and energy applications (ICPEA). Guangzhou, China, 504–509. doi:10.1109/ICPEA56363.2022.10052291

Ji, H., Wang, C., Li, P., Ding, F., and Wu, J. (2019). Robust operation of soft open points inactive distribution networks with high penetration of photovoltaic integration. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 10 (l), 280–289. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2018.2833545

Jiang, X., Zhou, Y., Ming, W., Yang, P., and Wu, J. (2022). An overview of soft open points in electricity distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 13 (3), pp1899–pp1910. doi:10.1109/TSG.2022.3148599

Jooshaki, M., Abbaspour, A., Fotuhi-Firuzabad, M., Muñoz-Delgado, G., Contreras, J., Lehtonen, M., et al. (2020). Linear formulations for topology-variable-based distribution system reliability assessment considering switching interruptions. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 11 (5), 4032–4043. doi:10.1109/TSG.2020.2991661

Li, R., Wang, W., and Xia, M. (2018). Cooperative planning of active distribution system with renewable energy sources and energy storage systems. IEEE Access 6, 5916–5926. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2785263

Li, Z., Wu, W., Tai, X., and Zhang, B. (2020). Optimization model based reliability assessment for distribution networks considering detailed placement of circuit breakers and switches. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 35 (5), 3991–4004. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2020.2981508

Li, B., Qin, C., Yu, R., Dai, W., Shen, M., Ma, Z., et al. (2023). Fast solution method for the large-scale unit commitment problem with long-term storage. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 9 (3), 39–49. doi:10.23919/CJEE.2023.000033

Li, W., Zou, Y., Yang, H., Fu, X., Xiang, S., and Li, Z. (2025). Two-stage stochastic energy scheduling for multi-energy rural microgrids with irrigation systems and biomass fermentation. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 16 (2), 1075–1087. doi:10.1109/TSG.2024.3483444

Lin, L., Jia, Q., Lv, C., Liang, J., and Luo, P. (2023). Partitional collaborative mitigation strategy of distribution network harmonics based on distributed model predictive control. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 14 (3), 1998–2009. doi:10.1109/TSG.2022.3211008

Liu, W., Lin, Z., Wang, L., Wang, Z., Wang, H., and Gong, Q. (2020). Analytical reliability evaluation of active distribution systems considering information link failures. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 35 (6), 4167–4179. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2020.2995180

Pamshetti, V. B., and Singh, S. P. (2022). Coordinated allocation of BESS and SOP in high PV penetrated distribution network incorporating DR and CVR schemes. IEEE Syst. J. 16 (1), 420–430. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2020.3041013

Pamshetti, V. B., Singh, S., Thakur, A. K., Singh, S. P., Babu, T. S., Patnaik, N., et al. (2023). Cooperative operational planning model for distributed energy resources with soft open point in active distribution network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59 (2), 2140–2151. doi:10.1109/TIA.2022.3223339

Pan, G., Gu, W., Lu, Y., Qiu, H., Lu, S., and Yao, S. (2020). Optimal planning for electricity hydrogen integrated energy system considering power to hydrogen and heat and seasonal storage. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 1l (4), 2662–2676. doi:10.1109/TSTE.2020.2970078

Peng, Y., Yang, Y., Chen, M., Wang, X., Xiong, Y., Wang, M., et al. (2023). Value evaluation method for pumped storage in the new power system. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 9 (3), 26–38. doi:10.23919/CJEE.2023.000029

Qian, Y., Wang, H., Zhou, M., Lv, H., and Liu, Y. (2022). Frequency trajectory planning-based frequency regulation strategy for wind turbines equipped with energy storage system. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 8 (2), 52–61. doi:10.23919/CJEE.2022.000014

Qiao, J., Meng, X., Zheng, W., Huang, P., Xu, T., and Xu, Y. (2025). Optimization configuration method of energy storage considering photovoltaic power consumption and source-load uncertainty. IEEE Access 13, 9401–9412. doi:10.1109/access.2025.3528050

Ravikumar, R., Srinivasan, M. V., Karunakaran, R. V., Srikanth, A., and Vijayaraghavan, V. (2022). “Deferrable irrigation load optimization in rural microgrid clusters,” in 2022 IEEE conference on technologies for sustainability (SusTech). Corona, CA, USA, 125–131. doi:10.1109/SusTech53338.2022.9794162

Saaklayen, M. A., Shabbir, M. N. S. K., Liang, X., Faried, S. O., and Janbakhsh, M. (2023). A two-stage multi-scenario optimization method for placement and sizing of soft open points in distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 59 (3), 2877–2891. doi:10.1109/TIA.2023.3245588

Schum, S., and Lin, A. (2012). China's renewable energy law and its impact on renewable power in China: progress, challenges and recommendations for improving implementation. Energy Policy 5l, 89–109. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2012.06.066

Tao, A., Zhou, N., Chi, Y., Wang, Q., and Dong, G. (2023). Multi-stage coordinated robust optimization for soft open point allocation in active distribution networks with PV. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 1l (5), 1553–1563. doi:10.35833/MPCE.2022.000373

Timalsena, K. R., Piya, P., and Karki, R. (2021). A novel methodology to incorporate circuit breaker active failure in reliability evaluation of electrical distribution networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 36 (2), 1013–1022. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2020.3010529

Wang, C., Zhang, T., Luo, F., Li, P., and Yao, L. (2018). Fault incidence matrix based reliability evaluation method for complex distribution system. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 33 (6), 6736–6745. doi:10.1109/TPWRS.2018.2830645

Wei, W., Zhou, Y., Zhu, J., Hou, K., Zhao, H., Li, Z., et al. (2019). Reliability assessment for AC/DC hybrid distribution network with high penetration of renewable energy. IEEE Access 7, 153141–153150. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2947707

Wei, W., Ye, Z., Wang, Y., Dai, S., Chen, L., and Liu, X. (2022). An economic optimization method for demand-side energy-storage accident backup assisted deep peaking of thermal power units. Chin. J. Electr. Eng. 8 (2), 62–74. doi:10.23919/CJEE.2022.000015

Xiang, Y., Su, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, J., and Zhang, X. (2020). An explicit formula based estimation method for distribution network reliability. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 35 (4), 2109–2112. doi:10.1109/TPWRD.2019.2949887

Yan, J., Liu, S., Yan, Y., Liu, Y., Han, S., and Zhang, H. (2024). How to choose mobile energy storage or fixed energy storage in high proportion renewable energy scenarios: evidence in China. Appl. Energy 376, 124274. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124274

Yin, H., Wang, Z., Liu, Y., Qudaih, Y., Liu, D. T., Liu, J., et al. (2023). Operational reliability assessment of distribution network with energy storage systems. IEEE Syst. J. 17 (1), 629–639. doi:10.1109/JSYST.2021.3137979

Keywords: rural distribution system, coordinated planning approach, on-load tap changer (OLTC), energy storage, reliability

Citation: Yang X, Zhong Y, Zhou F, Xu R, Jiao F and Xu J (2025) An optimization planning method for rural distribution systems considering on-load tap changers and energy storage. Front. Energy Res. 13:1692415. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2025.1692415

Received: 25 August 2025; Accepted: 03 November 2025;

Published: 04 December 2025.

Edited by:

Hao Yu, Tianjin University, ChinaReviewed by:

Changsen Feng, Zhejiang University of Technology, ChinaWentao Yang, Guangxi University, China

Copyright © 2025 Yang, Zhong, Zhou, Xu, Jiao and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xin Yang, MTc0MjUwNzE4MUBtYWlsLmhmdXQuZWR1LmNu

Xin Yang

Xin Yang Yalin Zhong1

Yalin Zhong1