- 1Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Katowicach, Katowice, Poland

- 2Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Akademia Śląska, Katowice, Poland

1 Introduction

Since electrification, economic development has increasingly relied on electricity. Automation, mass production, and increasing consumption have increased the demand for electricity, which has long been met mainly by fossil fuels. Increasing consumption generates not only production costs but also external costs, including health and environmental costs, resulting from ecosystem degradation (Strojny et al., 2023). This, in turn, strengthens the need to seek more sustainable energy sources.

The transition toward renewable energy sources responds to the global increase in demand and resource constraints and simultaneously reduces dependence on fossil fuels (Elkhatat and Al-Muhtaseb, 2024). However, a simple one-to-one replacement of fossil energy sources with renewable energy sources (RESs) will not, by itself, ensure sufficient supply or system stability. An effective transition requires a systems approach involving grid expansion, storage, and demand-side management.

The European Union does not fully meet its own energy demand. Import dependence reached 60.6%, creating risks for supply security (Rabbi et al., 2022). Policy should balance the energy technology portfolio and pursue gradual, coordinated decarbonization. A one-sided and overly rapid shift exclusively to RES may increase the risk of energy shortages and price volatility. Poland is a particularly interesting case because its power sector is among the most coal-dependent in the European Union. According to Statistics Poland (2025) data, Poland ranks first in terms of the share of coal in electricity generation, and distinct investments in RES are directed toward the energy transition to achieve the goals of the European Green Deal (Kubiczek and Przedworska, 2024).

This article examines the course of the energy transition in Poland and assesses the associated risks to energy security. We indicate that a rapid change in the generation structure (without proper coordination at the levels of infrastructure, the market, and regulation) may generate supply tensions. We also point out that the balance of energy trade affects the actual “carbon footprint” of consumption: imported energy is often generated from fossil fuels outside the country’s borders, which suggests that local emission reductions do not necessarily translate into real decarbonization in global terms.

2 Energy market conditions amid the war in Ukraine

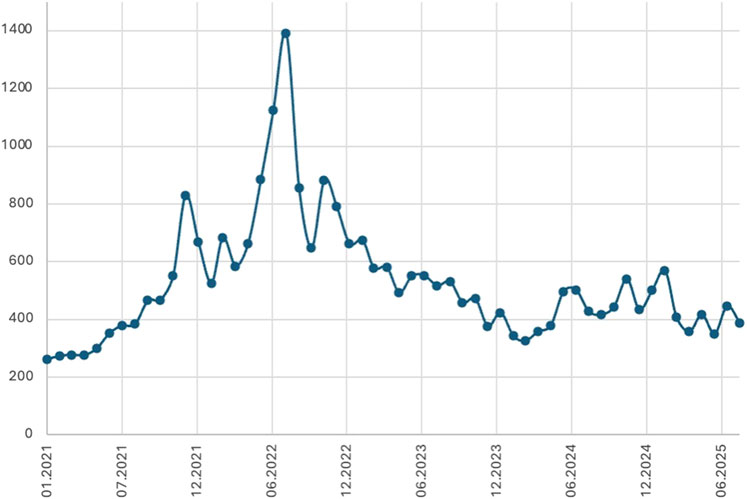

In Poland, electricity prices remained stable for a long time; however, the 2022 crisis, triggered by the war in Ukraine, led to a destabilization of prices in the energy market. The changes in electricity prices in Poland during the period 2021–2025 are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Electricity prices in Poland (TGeBASE). Source: Authors’ elaboration based on TGE Group data.

The observable pace of price growth accelerated significantly in Q2 2022, reaching its peak in August 2022. Additionally, as one of the first European Union countries, Poland experienced a suspension of gas supplies from the Russian Federation in April 2022, which had direct consequences for national energy security. However, the supply disruption did not translate into a significant increase in domestic coal generation. Diversified imports and higher commodity prices drove record energy spending on energy carriers in Poland: PLN 193 billion in 2022 compared to PLN 100 billion in 2021 (Lagurashvili, 2024).

At the household level, higher prices do not always lead to behavior change. Half of Poles declare that they are not ready to undertake the energy transition, even in the face of a significant increase in energy bills (Hadasik et al., 2025). The entrenched attachment to coal and modernization barriers coexist with relatively moderate public support for transition measures, estimated at approximately 60% (Lagurashvili, 2024). Under these conditions, it is justified to carry out the transition in a systemic manner, based on coherent regulatory frameworks and stable financing mechanisms, to translate declarative support into lasting changes on the consumer side.

3 Energy policy and security: Poland’s mix profile

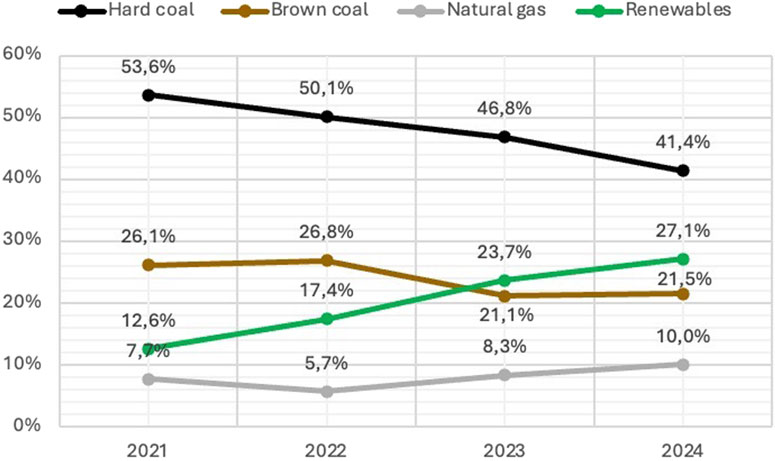

The geopolitical situation shifted government priorities toward the security of the energy supply. This was expressed in the Energy Policy of Poland until 2040 (EPP 2040) (Ministry of Climate and Environment, 2021) adopted in February 2021, in which the high dependence on a single supplier of natural gas and crude oil was indicated as a barrier to competitive price formation and as a source of vulnerability in the area of foreign policy. The strategy shows cross-government continuity, evidenced by accelerated RES investments and observable shifts in the energy mix. The detailed dynamics of the shares of individual energy sources are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Structure of the energy mix in Poland. Source: Authors’ elaboration based on the Polish Transmission System Operator data.

The share of renewables nearly doubled from 12.6% (2021) to 27.1% (2024), while the share of hard coal decreased from 53.6% to 41.4%. The key turning point came in 2023, when renewables (23.7%) overtook brown coal (21.1%) for the first time, while natural gas remained marginal (∼8–10%). This structural shift, most visible between 2022 and 2023, reflects the combined effects of regulatory measures, increasing CO2 prices, and the geopolitical shock of the energy crisis. The change in the structure of the energy mix has contributed to a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Since 1990, these emissions in Poland have decreased by 29.2% (and by 38.4% in the European Union as a whole). Since 2005, i.e., since the launch of the emissions trading system, they have decreased by 9.9%. According to data presented by the Polish Transmission System Operator, the average annual power demand in 2023 amounted to 23,052 MW and in 2024 to 23,200 MW. In parallel, the energy efficiency of the economy has improved. The current level of indicators is approximately 70% of the values recorded in 2000 (Statistics Poland, 2025).

At the same time, dependence on imports of energy carriers is increasing, which widens the gap in the trade balance. According to Statistics Poland (2025), in 2023, Poland already imported over 40% of the electricity used. The increase in imports increases vulnerability to external factors and limits control over the emissions footprint of domestically energy consumed as its generation occurs outside the national regulatory framework.

4 Energy security dimensions

Energy security is a complex and multidimensional concept. Under the Polish Energy Law, energy security is meeting current and prospective fuel and energy demand in a technically and economically justified way while complying with environmental requirements (International Monetary Fund. European Dept, 2023). According to the Asia Pacific Energy Research Centre, energy security is often framed around the four As:

• Availability—reliable access to adequate quantities and quality of energy resources within the system.

• Accessibility—the practical ability to obtain energy resources and services, shaped by infrastructure, regulation, and geopolitics.

• Affordability—energy prices and costs at levels users can bear while keeping the system economically viable.

• Acceptability—social and environmental acceptability of how energy is produced and used, including emissions and other impacts.

In the literature, energy security is often conceptualized through the “4As”; this approach is worth broadening by treating energy security as a special case of security in general—that is, low vulnerability of vital energy systems to threats (Cherp and Jewell, 2014).

From an international perspective, energy security is analyzed in conjunction with other dimensions of the energy sector. An example is the World Energy Trilemma Index, which emphasizes the interdependence and possible synergies among three pillars: environmental sustainability, energy equity, and energy security. Improving one area may, after all, trigger tensions in the others; therefore, public policies should be designed in a consistent and complementary manner to minimize trade-offs and strengthen their combined effects (Elkhatat and Al-Muhtaseb, 2024).

5 Blackouts and their consequences

Before the war in Ukraine, the generation did not threaten the security of supply (Dołęga, 2023). However, consumption continues to grow, and dependence is increasing, particularly as supply chains have been disrupted. According to PEP 2040, RES plays a central role; many energy suppliers align their strategies accordingly. State-owned enterprises are implementing PEP 2040 and moving toward RES, aiming for zero emissions. However, relying exclusively on RES poses risks to energy security (Harjanne and Korhonen, 2019).

• Intermittency and adequacy. Variable RESs require balancing capacity and storage.

• Grid integration. Scaling up RESs needs transmission reinforcement and ancillary services.

• Economics/institutions. Despite the falling LCOE, diffusion depends on market design and policy frameworks.

In the context of RES, the key challenge for energy security is weather variability. The climate crisis hampers reliable forecasting of production, which forces greater system flexibility and the maintenance of capacity reserves, reducing economic efficiency. Studies indicate that weather factors account for over 32% of power outages (Stankovski et al., 2023). One response is large-scale energy storage although it entails high investment and operating costs.

Extensive RES deployment without adequate grids, flexibility, and balancing may increase import dependence. Poland exhibits heightened vulnerability in this respect, and growing imports limit control over the generation profile and the emissions footprint of energy consumed domestically. The literature emphasizes a conflicting policy mix in which support for RES promotes decarbonization, while capacity mechanisms often compensate for the instability of sources with solutions based on fossil fuels. Shifting the emphasis from such solutions to low-emission technologies, demand-side response, and storage may reduce this contradiction (Kozlova et al., 2023).

A pragmatic approach is to combine RES with other low-emission sources. Natural gas emits less than 60% of CO2 per MWh compared to coal, which is why it can serve a dispatchable function in the transition period (Rabbi et al., 2022). Scenarios for Poland foresee complementarity between RES and gas, taking into account domestic demand, weather conditions, and the need to limit the risk of shortages (International Monetary Fund. European Dept, 2023).

Capacity shortages and blackouts have serious economic and social consequences, including disruptions to production, greater uncertainty, and interruptions in services essential to a digitized economy. Enterprises can invest in backup sources and energy storage, but higher costs are passed on to prices and weaken competitiveness. To minimize these risks, the transition in Poland should combine the deployment of modern technologies, long-term planning and infrastructure expansion, social participation, and interregional and international cooperation, which strengthens both decarbonization and security of supply (Krawczyńska et al., 2024; Lagurashvili, 2024).

6 Conclusion

The energy transition is a necessary response to climate change, but its implementation must be planned, coordinated, and evidence-based. Actions carried out without order increase the risk of shortages, price volatility, and social costs. The variability of weather conditions limits the possibility of rapidly replacing the entire generation with renewable sources, which is why, in the transitional phase, it is justified to combine RES with dispatchable, low-emission technologies, including gas. In the longer horizon, nuclear power may complement the mix, although in Poland, this requires time and significant preparations.

Policy implications point to the need to accelerate nuclear project preparation and delivery—or, at a minimum, to ensure that no further delays occur—while simultaneously undertaking a deep modernization of national power grids to reduce technical losses and enhance system flexibility. At the same time, it is important to strengthen civic education on electricity sources, their costs and constraints, and the trade-offs inherent in the transition. Taken together with a planned expansion of renewables and dispatchable low-emission resources, these steps would help sustain energy security, cost stability, and continuity of supply while keeping decarbonization on a trajectory aligned with the economy’s real capacities.

Author contributions

JK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. AK: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. AB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This paper has been written within the scope of the project “Regulation and Sustainability in Finance: Challenges and Opportunities for the Stability of the Financial System” (uniri-iz-25-33), funded by European Union – NextGenerationEU via the Croatian National Recovery and Resilience Plan 2021-2026, in conjunction with the University of Rijeka, Faculty of Economics and Business Programme Financing. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the European Union or the European Commission. Neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be held responsible for them.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript. Authors used OpenAI ChatGPT-5 for language editing only. Authors verified all outputs and accept full responsibility for the content.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Cherp, A., and Jewell, J. (2014). The concept of energy security: beyond the four as. Energy Policy 75 (December), 415–421. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2014.09.005

Dołęga, W. (2023). Ocena krajowego technicznego poziomu bezpieczeństwa dostaw energii elektrycznej. Zesz. Nauk. Inst. Gospod. Surowcami Miner. i Energią Pol. Akad. Nauk. 111 (1), 65–80. doi:10.33223/zn/2023/06

Elkhatat, A., and Al-Muhtaseb, S. (2024). Climate change and energy security: a comparative analysis of the role of energy policies in advancing environmental sustainability. Energies 17 (13), 3179. doi:10.3390/en17133179

Hadasik, B., Kubiczek, J., Ryczko, A., Krawczyńska, D., and Przedworska, K. (2025). From coal to clean energy: economic and environmental determinants of household energy transition in Poland. Energy Econ. 148 (August), 108697. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2025.108697

Harjanne, A., and Korhonen, J. M. (2019). Abandoning the concept of renewable energy. Energy Policy 127 (April), 330–340. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2018.12.029

International Monetary Fund. European Dept (2023). “Balancing decarbonization with energy security in Poland,” in Republic of Poland: selected issues.

Kozlova, M., Huhta, K., and Lohrmann, A. (2023). The interface between support schemes for renewable energy and security of supply: reviewing capacity mechanisms and support schemes for renewable energy in Europe. Energy Policy 181 (October), 113707. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2023.113707

Krawczyńska, D., Hadasik, B., Ryczko, A., Przedworska, K., and Kubiczek, J. (2024). Pursuing European green deal milestones in times of war in Ukraine – a context of energy transition in Poland. Econ. Environ. 88 (1), 736. doi:10.34659/eis.2024.88.1.736

Kubiczek, J., and Przedworska, K. (2024). Towards a green future: the Polish energy market and the potential of renewable energy sources. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Ser. (195), 2024. doi:10.29119/1641-3466.2024.195.21

Ministry of Climate and Environment (2021). Energy policy of Poland until 2040 (EPP2040). Ministry of Climate and Environment. Available online at: https://www.gov.pl/web/climate/energy-policy-of-poland-until-2040-epp2040.

Rabbi, M. F., Popp, J., Máté, D., and Kovács, S. (2022). Energy security and energy transition to achieve carbon neutrality. Energies 15 (21), 8126. doi:10.3390/en15218126

Stankovski, A., Gjorgiev, B., Locher, L., and Sansavini, G. (2023). Power blackouts in Europe: analyses, key insights, and recommendations from empirical evidence. Joule 7 (11), 2468–2484. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2023.09.005

Statistics Poland (2025). Energy 2025. Statistics Poland. Available online at: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/environment-energy/energy/energy-2025,1,13.html.

Keywords: energy transition, energy security, renewable energy, res, energy policy, energy mix

Citation: Kubiczek J, Kaliszuk A and Bochenek A (2025) Dynamics of energy transition in the context of Poland’s energy security. Front. Energy Res. 13:1701904. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2025.1701904

Received: 09 September 2025; Accepted: 22 October 2025;

Published: 10 November 2025.

Edited by:

Luan Santos, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, BrazilReviewed by:

Abdulmelik Alkan, Webster University, United StatesCopyright © 2025 Kubiczek, Kaliszuk and Bochenek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jakub Kubiczek, amFrdWIua3ViaWN6ZWtAdWVrYXQucGw=

Jakub Kubiczek1*

Jakub Kubiczek1* Amelia Bochenek

Amelia Bochenek