- 1Département des Sciences Exactes, Ecole Normale Supérieure d’Oran, Oran, Algeria

- 2Laboratoire de physique des matériaux et des fluides, Université des Sciences et de la Technologie d’Oran, Oran, Algeria

- 3Instituto Pluridisciplinar, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain

- 4Escuela de Arquitectura, Ingeniería, Ciencia y Computacón, Universidad Europea de Madrid, Villaviciosa deOdón, Spain

We reflect here on some aspects of interfacial transport phenomena, surfactants, and related flows. First, we recall concepts basic to the rest of the content. Then we highlight the extraordinary success of the concept of active, self-propelling drops thanks to the availability of microelectronic technologies and microelectromechanical systems that were not readily available in 1994 when the pioneering theoretical predictions by Rednikov, Ryazantsev, and Velarde were published. A digression about the ascent of sap in trees is presented, illustrating conflicting views in the botanical community. Surfactant spreading transport is also discussed, illustrating the conflicting views that exist about the superspreading phenomenon in the scientific community. In all cases, we provide suggestions for further research.

1 Interfaces and surfactants: surface tension/interfacial tension gradients and transport consequences

If processes at the strict phenomenological thermodynamic equilibrium level occur in the bulk range only, far from the boundaries, one form of thermodynamic pressure (P) is sufficient, depending on two independent variables, such as temperature and volume, which suffice for the complete description of a homogeneous phase. If curved surface boundaries are taken into account, then due to interfaces, another pressure component, σ (otherwise termed “surface” or “interfacial tension”), enters, as postulated by Laplace. Following the theory independently proposed by Derjaguin–Landau and Verwey–Overbeek (the “DLVO theory”), yet another pressure concept, here denoted “Derjaguin” (or “DLVO”) pressure (Π) appears useful in accounting for equilibrium when regions at the nanoscale range (102 nm, 1 nm = 10−9 m: thin liquid films and the like) are involved in a system. Quantity Π can have different components, acting singly or together: Van der Waals force, electrostatic force, and structural force/entropic force/orientation of water molecules, which are particularly relevant in confined geometries. Π is also denoted as “disjoining/conjoining pressure,” a terminology disregarded here. Π is considered as “surface” force, and we shall use “forces” in the plural (Derjaguin et al., 1987; Verwey and Overbeek, 1948; Starov and Velarde, 2020; Butt et al., 2006). Thus, the knowledge for thermodynamic equilibria is completed when we have their corresponding equations of state—P = P(T, V), σ = σ(T, A), and Π = Π(T, h) —with V, A, and h denoting volume, surface area, and nanometric film thickness, respectively (Starov and Velarde, 2009; Velarde M. G., 2011). Flow and/or transport (non-equilibrium) are generally associated with a gradient of the corresponding pressure. To complete the reference to the DLVO theory, we recall the quantum electrodynamics approach to the interaction problem of two parallel conducting plates (in a capacitor-like geometry with an internal fluctuating electromagnetic medium) taken by Casimir and Polder (1948) and Dzyaloshinskii et al. (1960) (for a review see Kardar and Golestanian, 1999).

For most liquids (e.g., water), surface tension (σ) decreases with increasing temperature. However, liquids, such as certain alcohol mixtures like dodecanol in alkane and others and some liquid crystalline fluids, exhibit a minimum or maximum in their surface tension with temperature variation. For instance, the solution n-heptanol in water shows a surface tension minimum at approximately 40 °C, and the mixture of 2-butoxyethanol–water exhibits an inverted miscibility gap with an increase in interfacial tension with increasing temperature. If a surfactant is soluble in a liquid solvent, the latter’s surface tension generally increases. The same happens when salt is added to a water layer or drop; there is an increase in its surface tension. However, if the solute is insoluble, it tends to lower its tension. The latter is the case when adding powder, dust, grease/fat, or oil. In general, surface-active agents (surfactants) do alter the surface tension of a liquid (open to ambient atmosphere), the interfacial tension between two liquids, or a liquid and a solid (Miller and Neogi, 2008; Rosen and Kunjappu, 2012).

Typical surfactants are organic compounds formed by amphiphilic molecules that contain both hydrophilic (water-soluble) and hydrophobic (water-insoluble) components, which can be schematically represented with a “head” and a “tail” (Figure 1). According to the nature of a polar hydrophilic part (usually “head”), they are classified as anionic (a negatively charged surface-active component such as RCOO−Na+—soap), cationic (a positively charged surface-active component such as RNH3+Cl−—salt of a long-chain amine), zwitterionic (positive and negative charges may be present in the surface-active component: RN+H2CH2COO−—long-chain amino acid), or nonionic (no apparent ionic charge: R(OC2H4)xOH—polyoxyethylenated alcohol). Differences in the nature of the hydrophobic group are usually less pronounced than those of the hydrophilic group. Generally, they are long-chain hydrocarbon residues. Noteworthy as a significant exception are trisiloxane surfactants, whose hydrophobic part is a trisiloxane group (more on this below). The orientation of surfactant molecules on the surface of an aqueous solution is such that a hydrophobic tail sticks out from the liquid into the ambient atmosphere, while the hydrophilic head is submerged in the water. Surfactants have widespread applications, such as helping create microemulsions, acting as foaming agents, emulsifiers, dispersing traits, detergents, wetting, and antimicrobial activity, tailored as per industrial requirements.

Figure 1. Surfactant molecules in various typical configurations. Extreme left panel: as free surfactant monomers and molecules gathered together forming a micelle. Right four panels: (a) representation of an amphiphilic surfactant molecule consisting of a hydrophilic head that preferentially partitions in the aqueous phase and a hydrophobic tail that preferentially partitions in the oil phase. Different architectures of surfactants in differently arranged multiphase systems: (b) oil droplet in the water phase; (c) aqueous droplet in the oil phase; (d) vesicle consisting of a phospholipid bilayer. After Čejková et al. (2017).

Insoluble surfactants are those that reside/adsorb on the surface of the liquid and are not absorbed in the bulk. For those soluble at a low surfactant concentration, their molecules exist in a solution in the form of individual monomers (Figure 1) (Čejková et al., 2017). They tend to dissolve in the bulk, but as they adsorb onto interfaces they also form monolayers. Such monolayers delineate an equilibrium point between surfactants adsorbing at the interface and dissolving in the bulk. At increased surfactant concentrations, different molecular aggregates form in addition to monomers: spherical micelles, bilayers, and spherical vesicles (Figure 1). These aggregates are formed when surfactant concentration exceeds some critical value, which is called “critical micelle concentration” (CMC) or “critical aggregation concentration” (CAC). The adsorption of additional layers of surfactant molecules on interfaces and the formation of multilayered lamellar structures and cylindrical aggregates are also possible.

There is no doubt that phenomena occurring at interfaces such as fluid–fluid or fluid–solid play a significant role in a wide variety of biophysico-chemical and other technological–industrial fields. There is the exotic albeit real possibility of growing crystals (from liquid to solid state) of pharmaceutical/medical applications or electronic interest aboard an orbiting space station or other spacecraft under quite low effective gravity (say 10−4 gEarth) or under practically similar conditions in drop towers, parabolic flights, or sounding rockets. On the one hand, for fixed surface tension and density (or density contrast with two media), capillary length is determined by the effective gravity (this is monitored by the so-called Bond–Eötvös dimensionless group). On the other hand, for fixed geometry, viscosity, heat diffusivity, and thermal expansion, buoyancy is significant, depending on the value of the effective gravity. As the value of the latter is drastically reduced aboard a spacecraft, so it is significantly reduced in the role of buoyancy in the crystal growth process (here the ratio of forces is, for example, the Rayleigh dimensionless group; on occasion, the Grashof group is invoked, although it is not a ratio of forces). In all cases, the drastic interference from containers is practically ruled out, and interfaces play a dominant role over that of bulk phases (Ryazantsev et al., 2017). Down on earth, it is well accepted that interfacial phenomena affect factors such as adhesion, wetting, adsorption–desorption kinetics, and film formation. In pharmacological/medical care, interfacial phenomena coupled with bulk processes such as diffusion, addition of surfactants, flow-convection, and chemical reactivity play a significant role in the selective mechanism of the drug delivery of active substances.

In particular, the use of surfactants brings us straight to processes involved in the spreading of complex liquid drops. Two accepted differences between surfactant solutions and pure liquids are, on the one hand, the possibility of generating large differences in interfacial tension between adjacent parts of the spreading drop, and on the other hand, the possibility of molecular orientation influencing interactions between the liquid and the substrate in the case of the latter being a solid. Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) is a surfactant phospholipid with a phosphate group. It significantly reduces surface tension in the liquids over lung alveoli, thus permitting the latter to appropriately remain open and hence allow normal respiration. This is relevant for prematurely born babies and for adults with respiratory disease syndrome. It is a clear case of pulmonary-surfactant therapy (Jobe and Jobe, 1993). The preparation of plasmonic membranes, at the basis of cellular life, requires an expert knowledge of interactions at the interface of immiscible liquids. In the beauty care sector, designing appropriate textures requires an understanding of intricate interfacial phenomena (Tadros, 2018).

In food processing, preservation, or other technologies used, for instance, with milk or sauces, emulsification is a key process (Berton-Carabin and Schroën, 2019). Drop spreading of surfactant aqueous solutions on the surface of fluid layers allows for fast and efficient transport for many natural and technological–industrial applications ranging from inkjet printing to pesticide spraying in agriculture and cleaning (e.g., in the manufacturing of chips on silicon wafers). The presence of surfactants generally enhances the spread of a liquid on a solid surface or on some other difficult-to-wet, often hydrophobic, substrates. It is known that the epicuticular wax on leaves acts as a barrier to wetting. Water alone on leaf velvet gives a contact angle over 90° and offers little spreading action. If the addition of a surfactant reduces surface tension, it leads to a lower contact angle with a corresponding increase of the spread area on the leaf. This finding is particularly relevant for pesticide transfer. When pesticides are applied to crops after dew has formed, the pesticide, mixed with a surfactant, enters the dew droplets, allowing the pesticide to spread effectively over the leaf surface (Stenens et al., 1989; Gaskin et al., 1989; Zabkiewicz et al., 1989; Knoche et al., 1991).

The study of interfaces between immiscible liquids, such as water and oil, is crucial for understanding and addressing real-world issues like hydrocarbon spills. These spills, occurring in oceans, lakes, and rivers, present a significant environmental challenge, and the development of effective decontamination technologies relies heavily on understanding the interactions between these immiscible liquids. The same applies to trying to remedy the situation after accidental or inadequate handling of industrial or domestic oils, whether water-based substrates or others are involved. Consider also the complex technology of oil recovery in the so-called “tertiary phase” (Sch et al., 1964; Churaev et al., 2001a; Barron et al., 2020; Sheng, 2020).

Referring to temperature, mathematically we may have

where σ0 and

Such quadratic dependence (Equation 2) is exhibited by some aqueous solutions of high-molecular-weight alcohols, some metal alloys, and some liquid crystalline fluids.

A surface tension gradient then brings a thermocapillary force/pressure gradient (aka “Marangoni force”), usually in the range 0.1 μN/10−7 N—several orders of magnitude larger than other (surface-influencing) forces generated from electric fields or optical tweezers (ca. picoNewtons/10−12 N). For water-like standard liquids, flow motion proceeds from the hot (low surface tension) to the cold (high surface tension) region. This also occurs when there is a surfactant concentration gradient or when the gradient is produced chemically, electrically, or magnetically. For instance, if a drop is placed in another fluid under a temperature gradient, it will experience flow along its surface from the hot to the cold side. Eventually, this flow produces a matching flow in the outer fluid from the hot to the cold region, which necessarily leads to propulsion of the drop toward the hot region. It seems pertinent to clarify that thermocapillarity arises from (dσ/dT) under ΔT, whereas Marangoni propulsion can be driven by temperature or surfactant concentration heterogeneity at the interface (Schmitt and Stark, 2016).

Note that contrary to intuition, surfactant-induced interfacial tension gradients can persist transiently in dynamic systems. This persistence is explained by the relative kinetics of the underlying processes: the characteristic time scales of Marangoni flows and interfacial adsorption are significantly shorter than for molecular diffusion. Consequently, diffusion, although present, is quite a slow process and does not have time to homogenize the gradients before they are sustained by the flows which they themselves generate. On the other hand, evaporation, heat, mass, and more complex heat and mass cross-transport processes (e.g., Soret thermal diffusion), adsorption–desorption, and chemical reactions tend to affect surface/interfacial tensions, thus also creating tension gradients leading to flow. Furthermore, the abovementioned Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces at the hundred-nanometer down-region near a solid surface, as in the so-called “interfacial water,” where the role of electric double layers with a balance of electrostatic repulsion and Van der Waals attraction may be significant, or thin enough liquid layers where a gradient of film thickness, leads to a gradient of pressure. The interaction of water with solid surfaces is important in geochemistry, soil science, corrosion processes, tribology, atmospheric chemistry, environmental science, and even in some life processes (Illien et al., 2017; Hiemenz and Rajagopalan, 1997; Pollack, 2001). More on this below when dealing with the ascent of sap in trees.

Fluid motions driven by surface/interfacial tension gradients have been thoroughly studied and well documented for over a century. In particular, there is a wealth of literature on the paradigmatic Bénard–Marangoni and Rayleigh–Bénard convection setups (buoyancy-driven convection, coupled or not to surface tension gradient) when heat or mass transfer are involved or when combinations of both (Soret effect mentioned above) exist, and even when chemical reactions generate density differences and/or altering surface/interfacial tensions (Normand et al., 1977; Colinet et al., 2001), not to mention evaporation, electric fields, magnetic fields, and other affects. It is worth exploring the behavior of particles added to thin films, like nanoparticles (may act as surfactants) or where the particle size is comparable to the film thickness and may adsorb simultaneously at both interfaces (Gandhi et al., 2025).

2 Drops (passive, active, self-propelling)

Although it is textbook knowledge, the interfacial/surface tension is an intensive thermodynamic quantity, independent of geometry, but can vary with surface coverage in surfactant solutions. It is the major factor leading to the formation of drops or bubbles. It corresponds to the tension which confines and retains the fluid (liquid or gas/air) in its interior. Its action is situated in a surface layer where the tension apparently plays a similar role to a thin elastic film (e.g., Gibbs’ surface model). However, this comparison is misleading and conceptually wrong. The surface stress at each point of the interface does not depend on the elongation (stretching/extension or shrinking/contraction) of the surface. If the volume of drop or bubble changes due to alteration in mass contents, then the radii and lengths of all lines on the surface also change due to the transfer of molecules from volume to surface. Nevertheless, the interfacial tension remains the same; it depends on the fluids under consideration joining volumes at the interface of the drop or bubble.

Drops can be observed free, hanging, suspended in air, sessile, aggregating, coalescing, disintegrating/splitting, or spreading in nature in engineering processing or domestic settings. Similar is dew and fogs with drops of diameters in the range approximately 20 µm (1 μm = 10−6 m), rain with drops—the main component of clouds—that may attain one or more millimeters in diameter, aerosols, emulsions, and colloids. Similar too are small enough drops (in the microliter range) being transported over the surface of another liquid by means of surface acoustic waves (piezo electric substrate involved). Their motions offer beauty and challenges from scientific, engineering, and artistic perspectives. On the other hand, a drop has been and continues to be a model for many natural systems as disparate as planets, bacteria and other microorganisms, and atomic nuclei. Adding surfactants may help prevent drop coalescence, thus ensuring the stability of single drops, when the surfactant itself does not interact or exchange with the chemicals inside a drop. However, drops are seldom completely sealed, and molecules can traverse in and out in their surface, particularly if this is a bilayer. Surfactant transfer from a drop to the surrounding liquid can be accompanied by drop motion and deformation of its interface, which can promote coalescence. Drops, like solid spheres, may be affected by electric fields when charged. Although electric charge is normally induced passively on a drop or particle and there is no preferred direction associated with an individual sphere, there are dilute suspensions in which charged drops or particles actually “swim” in the direction of the applied electric field (Ryazantsev et al., 2017; Maass et al., 2024; Michelin, 2023).

2.1 Self-propulsion of isotropic drops in a homogeneous surrounding

The self-propulsion of an isotropic drop (with no deformation of its surface) immersed in a uniform environment (Ryazantsev et al., 2017; Rednikov et al., 1994; Velarde et al., 1996) (Figure 2, in upper left block, subpanel a shows arrows of identical size) may be the consequence of a spontaneous symmetry-breaking mechanism. For instance, it is possible for a drop, initially stationary in an isothermal surrounding, to start moving (darker solid arrow in upper left block subpanel b) due to the action, for example, of a uniform source of heat within the drop or the uniform generation of heat at the surface of the drop due to an inside or surface chemical reaction. A disturbance that causes a slight movement of the drop will lead to a temperature variation on the surface of the drop because of the non-uniform heat transport between the drop and the surrounding fluid arising from the convective transport along its surface. Once the motion is initiated (indicated by longer right arrow in subpanel b of upper left block), it may disappear due to viscous drag as time passes, or it could be maintained, for instance, by the appearance of an appropriately sustained surface tension gradient. Under the right conditions, the drop will continue to move in the same direction due to the action of thermocapillary stress (recall the Marangoni flow), sustaining the motion indefinitely (Figure 2). Passive drops move when they are subject to external forces. Active drops self-propel—that is, they swim autonomously with zero net resultant force. In Illien et al. (2017), the concept of self-phoresis is introduced, and a thorough discussion of various phoretic effects leading to drop propulsion is provided. Note that oscillatory motions and the directed self-propulsion of drops, such as in an aqueous solution, have been attributed to the periodic formation and destruction of a surfactant monolayer at the interface due to the way surfactant molecules present in the aqueous solution transit through the interface. We note too that a gradient of surface surfactant concentration, arising from interfacial motion, may lead to an interfacial tension gradient which opposes that caused by temperature variation (Figure 3). Finally, a redistribution of surfactant at the drop’s surface may induce an additional resistance force, thus adding to viscous drag. Indeed, for a drop in motion surrounded by surfactant molecules, if the latter accumulate at the rear of the drop, they tend to lower the drop’s surface tension there; as the surface tension decreases at the front of the drop, there is a slowing of the motion and eventually a complete stop (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Drops under various circumstances induced by the action of surfactants and surface tension gradients, self-propelled active drop motions, and associated flows. Upper left panel: schematic illustration (Rednikov et al., 1994) indicating eventual drop self-propulsion from subpanel (a) to subpanel (b) (see main text for details). Upper right (colored) panel: more complete picture (Michelin, 2023). Again, with initial isotropic and uniform conditions, there is rest or motion (zero versus non-zero velocity) depending on activity inside or at the surface of the drop; reacting (subpanel a) and solubilizing (subpanel b) drops. A chemical (red) is produced inside the drop, thus reducing surface tension due to the adsorption of the surfactant molecules. Regions of converging surface flows are rich in altered (red) surfactant molecules (increased surface tension), while diverging surface flows replenish the surface in pristine (black) surfactant (reduced surface tension), thus enhancing the fluid and drop motions. In self-solubilizing drops, the drops’ fluid is transferred near the surface into swollen micelles, reducing the local surfactant concentration. The accumulation of swollen micelles in the wake of the moving drop thus maintains interfacial stress (red arrows) and Marangoni flow (blue arrows) driving the drop motion (velocity is not zero). Lower left panel: competition between gravity (g) and “activity” leading to surfactant concentration tension gradient and surface tension gradient showing flows (not zero v; under appropriate condition, drop could stand still) inside and outside the drop, as in the preceding colored panel. Lower right panel: schematic of an isolated micelle prone to decompose and subsequent surfactant molecule adsorption at a drop, leading to surface tension gradient causing Marangoni flows and drop motion (inside and out according to corresponding arrows). After Michelin (2023).

Figure 3. Surface tension gradient-driven (Marangoni) flows are not always as simple as depicted in Figure 2. The three-figure panel depicts stream lines of the flow inside and outside an active drop. The actual pattern depends on the different material parameters of fluid and flow, in and out, affecting the action of the gradient. Thus, from right to left in the panel, we could have flow as in Figure 2, behavior of the drop as a solid particle/no-flow inside the drop, or super-resistance (added to the usual viscous drag) to flow.

As noted by Maass et al. (2024) and Michelin (2023), self-propelled active drops were already discovered by Otto Bütschli in the 1890s (Bütschli, 1892), who studied the physics of the protoplasm in a protocell model of oil-in-water emulsions, or Olseifensch aume. Science forgot about these curiosities for a century until spontaneous self-propulsion by interfacial instabilities was proposed in the 1990s by Rednikov et al. (1994) and Velarde et al. (1996) without an experimental stimulation. In the 2000s, these started to arrive, quite often from chemical engineering, and with intricate dynamics and reaction schemes going beyond what can be mapped by a simple reaction–diffusion scenario. It seems that the first experimental demonstration of self-propulsion of drops was offered in 2014 by Izri et al. (2014).

2.2 Directed drop propulsion via micellar adsorption

Consider an initial surfactant-free drop which adsorbs micelles formed by surfactant (Figure 2). The adsorbed micelle not only induces Marangoni flow in the proximity of the drop but also radial flow toward the adsorption site. The radial flow enhances the chance that other micelles adsorb at the same site. This mechanism leads to the directed propulsion of an initially isotropic emulsion drop if the micellar adsorption rate is sufficiently high. Clearly, the mechanism is favored when surfactants are adsorbed through micelles. Single surfactants would not produce a sufficiently strong radial flow to spontaneously break the initial isotropic symmetry of the drop.

2.3 Scale-dependent challenges in drop self-propulsion

Clearly, if a chemical reaction inducing self-propulsion occurs all over the surface of too small a drop (micrometer size), it may be difficult or impossible to identify the point where the reaction starts. As motion develops quickly, it may proceed in an uncontrolled direction. Size really matters as the surfactant concentration diminishes with the scale imposed by the ratio of surface to volume, and there would be increasingly fewer surfactant molecules at a drop’s surface, so that their role may become negligible. Additionally, when a drop moves in a gas or in air, evaporation may occur. If this is the case, its radius evolves with a rate as the inverse square (a−2) so that evaporation tends to proceed faster as size diminishes. Finally, for sizes below 1 μm, the role of Brownian motion is predominant.

2.4 Key factors in drop behavior on substrates

For a sessile drop or a drop sliding on another liquid or on a solid substrate (excluding now spreading, to be considered later), wettability conditions such as wettability gradient/difference in contact angles, using magnetic fields or other agents as well as the degree of hydrophilicity (wettability or hydrophobicity/no wettability and not solely surface tension difference) is of critical influence, and hence the chemical/mechanical inhomogeneity of the substrate becomes significant. To the above, we must add the dominant role that Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces can play.

2.5 Active drops as biomimetic systems and microfluidic tools

Active drops are morphologically and dynamically similar to living cells and sensitive to their chemical environment, so their potential as biomimetic artificial protocells has already been noted. Examples include walking grains, rolling or skating colloids, and various swimmers like bacteria, flocking birds, and cytoskeletal networks, as well as synthetic cases such as Janus particles and robotic swarms. The continuous consumption of energy drives active entities out of (thermodynamic) equilibrium (Ryazantsev et al., 2017; Maass et al., 2024; Michelin, 2023).

Drops can be natural candidates for use as microfluidic carriers, or even as microfluidic reactors, when appropriate control of their formation and transport can be achieved (Ryazantsev et al., 2017; Maass et al., 2024; Michelin, 2023). In microfluidics, bulk phenomena are secondary to surface effects. Encapsulation, such as of a cell into picoliter drops, not only permits the cell to be confined but also reagents the secreted molecules of desired reactivity. For instance, Escherichia coli can be encapsulated and manipulated inside a water-in-oil drop in microfluidic chips. On the other hand, it is possible for a micro-swimmer encaged in a drop to propel its viscous cage and co-swim with it. This setup can be of interest for drug delivery under appropriate circumstances. Indeed, drops containing smaller drops or bubbles (compound drops) are of practical interest in engineering (heat exchangers) or biology (mimicking eukaryotic cells). During the motion of compound drops, heat and/or mass transport from one to the other may occur as the surface of the encapsulated drop may be active—for example, a surfactant may be secreted from it. Aqueous drops from a few picoliters to sub-femtoliters (1 femto = 10−15) can serve as reaction vessels for the chemical manipulation of single cells, individual sub-cellular organelles, and single molecules.

3 Digression: the ascent of sap in trees

Another interesting problem where interfacial phenomena, surfactants, and Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces may play a significant role—the latter not duly acknowledged—is water/sap ascent in trees (approximately dm/hour to m/hour in human scale; laminar flow, genuine microfluidics carrying several hundred liters to leaves) (Tyree and Zimmermann, 2002; Jensen et al., 2016; Venturas et al., 2017). Sap is mostly water or, more precisely, approximately a 10 mol m-3 aqueous solution of minerals, hormones, and some nutrients (surface tension is lower than pure water as pH values are of the order of 5–6; the presence of fixed negative charges in xylem is to be considered). The channels which carry such water from the roots to the leaves are formed from dead tissue known as xylem/wood which is made of lignin, unlike the transport of nutrients in the other direction via living phloem/tree bark. Xylem “tubes” vary in diameter from several to a few hundred micrometers and in length from millimeters to meters. The variation in this is between species as well as within a tree. The inner zone of the xylem is denoted “lumen”. Water transports along the walls or within the lumen. Lignified walls are partially hydrophobic, but some trees have xylem inner wall surfaces covered with a lipid film that influences wettability and water flow. Xylem cells are born wet. In a water-like liquid, it is clear that capillarity as established by Jurin’s law is manifestly unable to account for sap rise in trees (beyond approximately a meter in height).

Xylem “tubes,” ascending together by the thousands in a tree, do not run parallel. They are divided into sections of disparate length that have end caps separating the sections and pit pores in the walls that permit water to pass from one portion to another (pits seem to protect against air entry). In tall trees, initially intact portions of xylem tubes break down in the summer. Xylem sap transport can also be disrupted by cavitation, an abrupt liquid–vapor change that results in air-filled xylem tubes. Furthermore, the freezing of water in the xylem of trees in cold climates causes the formation of air bubbles in all vessels, as air is practically insoluble in ice. Later, the air bubbles are supposed to be reabsorbed as the ice melts and flow in the xylem ensues. It is thus clear that as no xylem tubes are continuous from bottom to top, the liquid water columns are also not continuous along. However, it does seem that the xylem structure can conduct sap despite gaps along the path.

No topic in plant physiology has a longer history with a voluminous research literature than water ascent in trees against gravity. Not surprisingly, there have been conflicting opinions about this, and over the past century there has been “hot” controversy regarding the mechanism of xylem sap transport. At present, most plant scientists seem to agree on a so-called “cohesion–tension theory.” A large part of this scientific community considers it an absolute truth, as publicized in a 2004 letter signed by 45 scientists from seven countries published in the New Phytologist: “The cohesion–tension theory is widely supported as the only theory consistent with the preponderance of data on water transport in plants” (Angeles et al., 2004). The letter was followed by an editorial in New Phytologist indicating “…that views expressed in any review or paper appearing in the journal belong to the authors alone”. According to Tyreee (2003): The cohesion–tension mechanism works in spite of the high probability of millions of cavitations in conduits because there are billions to trillions of conduits in a tree and because adjacent conduits are isolated from each other and other primary cell walls in pits. Conduits are interconnected by multiple adjacent conduits, providing redundancy in multiple pathways for water movement should one conduit cavitate (see, however, Preston and Frey-Wyssling, 1952; Mackay and Weatherley, 1973).

The cohesion–tension theory, assuming continuity in the sap column, supposes both the adhesion of water to the xylem walls and the cohesion of water molecules to each other due to the long-range attractive Derjaguin (DLVO) forces (adhesion of water molecules to the assumed hydrophilic surface xylem wall; incidentally, the same adhesion is responsible for the ready absorption of water by the cellulose fibers of paper towels). The driving force is generated by surface tension at the evaporating surface of leaves, with energy coming from the sun overcoming the latent heat of evaporation of the water molecules. Thus, transpiration at the leaf surface pulls water through the xylem conduits along a gradient of negative pressure (also known as “sub-atmospheric pressure”/”sub-vapor pressure”; water flows in metastable conditions) —the so-called tension up to 1–10 MPa, 20 MPa (an estimation exists of 1 atm at the base of the trunk to approximately −20 to −30 atm at the crown). Confusingly, different estimates appear in different studies under different conditions: simplified drastically, 1 MPa

There are suggestions, hypothesized alternatives, and complementary mechanisms for this multifaceted process which appeal to osmotic/hydrostatic pressure gradients, interfacial tension gradients or, rarely considered so far in plant studies, Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces. Thin liquid films are expected to wet xylem surface walls along the path. It is well established that nanoscale thin liquid films of below 100 nm on a surface exhibit properties significantly different from those of their bulk form. Thus, Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces, which as noted earlier are the key quality controlling nanoscale liquid films, can support an upward lift to spreading nanometer-thin films of variable thickness along the walls of broken xylem portions (a gradient of film thickness leads to a gradient of pressure). Sap is a weak electrolyte, and hence the electrostatic interaction between sap with expected fixed charges to the inner wall surfaces of xylem conduits. Additionally, electrical double layers can form at the inner wall surfaces, provided that these are kept wet so that ionogenic groups are in a dissociated state (Amin, 1982). The exchange of materials, including water, between xylem and neighboring tissues can fulfill this condition ideally. The latter can take up water from xylem when it is present there in excess and release it when it is deficient (Gouin, 2012). There is also the entropic effect in confined geometries (Thompson, 2018).

4 Surfactant spreading transport: a succinct overview of recent findings and discussion of conflicting views

It seems well accepted that drops spreading, whether on a solid or on another liquid substrate, implies a diversity of phenomena in the interaction with the surroundings (Starov and Velarde, 2020; Velarde, 2011b). This has been of particular interest since the 1964 discovery (Sch et al., 1964) of the so-called “superspreaders” (Patents US 3299112, 1967; Stoebe et al., 1997). Superspreading is where, under appropriate conditions, certain liquids become extraordinarily high spreaders/superwetters. An accepted difference between a superspreader and a normal spreader or a non-spreader is complete wetting for the former against partial wetting for the latter. Among the so-called superspreaders, the trisiloxanes have been considered archetypal (Hill, 1998; Venzmer, 2011; Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024; Marques Silva et al., 2023 constitute a succession of well documented and insightful critical reviews). A typical example of superspreading is described by Venzmer: A 50-μL droplet of a 0.1% aqueous solution of a superspreading surfactant gives within 1 min a wetted area of approximately 70 mm in diameter on a hydrophobic substrate such as polypropylene film. In contrast, there are structurally quite similar trisiloxane surfactants, which do not superspread, but only give a much smaller spreading area with a defined contact angle (Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024).

Trisiloxanes currently used in experiments include (CH3)3SiO)2Si(CH3)-(CH2)3(OCH2CH2)nOH, otherwise noted as M(D'EnOH)M [-(CH2 CH2O)nOH], with n being the number of oxyethylene groups—in shorthand referred as T6 and T8, in the cases of n = 6 and 8, respectively. M is a trimethyl unit [CH3)3-SiO-], and D’ = [CH3SiO(CH2)3]; as noted earlier, siloxane is the bulky hydrophobic part, and ethoxy is the long hydrophilic tail. Though the latter both are superspreaders, the specific role played by the molecular structure and its corresponding spreading behavior is not fully understood, as T6 and T8 only differ in the length of the ethoxy chain. The molecular weight of T6 is 606.0 g/mol and that of T8 is 694.1 g/mol. T4 is highly hydrophobic and to our knowledge is a non-superspreader; T12 is certainly not a superspreader. As Venzmer (2021) emphasized, in terms of surface tension, there is no difference between T6, T8, and T12 except in terms of molecular structure/phase and spreading behavior, and “…only the slightly more hydrophilic, non-superspreading trisiloxane surfactants form spherical micelles; the superspreading trisiloxanes are somewhat less hydrophilic and form bilayer aggregates such as vesicles.” Venzmer (2024) insisted, “The bulk phase behavior of the two kinds of trisiloxane surfactants is significantly different: spherical micelles (i.e., curved aggregates) for the non-superspreaders, and bilayers (vesicles, L3 phase, i.e., zero mean curvature aggregates) in case of the superspreaders.”

The literature on superspreaders is considerable, including several reviews providing “evidence,” arguments, suggestions, and conclusions in conflict (Stoebe et al., 1997; Hill, 1998; Venzmer, 2011; Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024; Marques Silva et al., 2023; Churaev et al., 2001b; Lee et al., 2008; Ivanova et al., 2010; Starov et al., 2010; Kovalchuk et al., 2016; Kovalchuk et al., 2020; Nikolov et al., 2002; Nikolov and Wasan, 2011; Nikolov et al., 2013; Nikolov and Wasan, 2015; Nikolov et al., 2021; Kovalchuk et al., 2024; Svitova et al., 1998; Svitova et al., 2001). According to Venzmer (2021), “Hardly any other topic in the field of wetting has yielded such controversial and mutually incompatible opinions and hypotheses” (Figure 4). According to Kovalchuk et al. (2024), “The question of why aqueous solutions of some surfactants demonstrate a rapid spreading (superspreading) over hydrophobic solid substrates, while solutions of other similar surfactants do not, has no definitive explanation despite numerous studies.” Starov et al. (2010), writing “Why do aqueous surfactant solutions spread over hydrophobic substrates?”, observe, …a mechanism behind the spreading of surfactant solutions over hydrophobic substrates … has not been understood yet. No doubt that (a) both capillary and surface forces (Derjaguin’s or disjoining pressure) are involved, but the presence of surfactants (b) modifies surface forces, (c) causes surface tension gradients, and (d) adsorption/desorption of surfactant molecules on all interfaces involved change dramatically events in a vicinity of the three-phase contact line. A detailed understanding of phenomena involved (a)–(d) is far from being complete. This is followed by a thorough discussion of spreading on highly hydrophobic solid substrates.

Figure 4. Stoebe et al. (1997); see also Hill (1998) versus Venzmer (2011). Left panels (Stoebe et al., 1997): schematic representation of the events postulated as responsible for surfactant-enhanced spreading of aqueous mixtures on mineral oil substrates. Spreading is driven by Marangoni flow due to surface tension gradients along the air–water and mineral-oil–water interfaces that are created by spatial gradients in surfactant concentration along these interfaces. Right panels (Venzmer, 2011): suggested situation at the leading edge of a drop of aqueous surfactant solution on a hydrophobic substrate; (A) non-spreading micelle-forming surfactant: suboptimal reduction of interfacial tension solid/water; (B) superspreading bilayer-forming surfactant: best reduction of interfacial tension solid/water and efficient transport of surfactant to the leading edge.

Churaev et al. (2001b) treated various cases of superspreading, including film climbing over a hydrophobic inclined plane, by appealing to gradients of Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces on wetting films (recall comments made about xylem in trees). Rapid spreading was explained by the formation of extremely thick wetting films stabilized by the mutual repulsion of vesicles and, partially, by long-range electrostatic forces. Nevertheless, they concluded that the problem demands further investigation, suggesting computer simulation as useful tool for studying different items, stepwise, involved in the superspreading process.

Nikolov et al. (2002) contributed “Superspreading drive by Marangoni flow.” In a 2015 review, Nikolov and Wasan (2015) continued with the assertion that “…the Marangoni stress is the most reasonable explanation of the faster spreading rate.” They also stated: “No experimental evidence has been presented for the role of bilayer formation on superspreading.” They further continued, “…it is amazing to see how many different concepts have been proposed to explain the superspreading phenomenon.” They concluded that “…despite many attempts and studies to present a simple understanding of the mechanisms governing superspreading, the answer is still uncertain.” Kovalchuk et al. (2020) stated, “Bilayer formation was also observed in molecular dynamics simulations,” and continued, “The contribution of Marangoni flow to the superspreading mechanism is now broadly accepted, but many questions remain unanswered.”

Venzmer (2021), in a critical review entitled “Superspreading: Has the mystery been unraveled?”, made alternative suggestions, opinions, and conclusions based on solid thermodynamics and other factors: Two of the most popular concepts under discussion are A) a positive spreading coefficient and B) Marangoni flow. These are mutually excluding each other, because S > 0 requires a low surface and/or interfacial tension at the three-phase contact line (TPCL), while Marangoni flow requires a high surface tension at the leading edge. However, a process going on for 60 s against thermodynamics, i.e., complete wetting, although S < 0? How could possibly a surface tension gradient be created and maintained for the duration of the spreading process? Hypothesized has been surfactant adsorption to the substrate at the TPCL, leading to an increase in air/water surface tension to maintain the surface tension gradient causing the area expansion. The driving force must be a “sustainable” one, being present for the duration of the entire spreading process, but 1 min is not the typical timescale for surface tension gradients to exist. Subsequently, Venzmer (2024) insisted on the above argument, making it clear: “Local differences in surface tension have been cited repeatedly as the most likely driving force for superspreading, although this is in contradiction with experimental evidence showing that superspreading only starts after a surface tension gradient has been eliminated.” For a liquid drop over a solid substrate, S = σS-σSL-σL, with σS being the surface tension of the solid, σSL the interfacial tension between solid and liquid, and σL the surface tension of the liquid.

Venzmer rightly recalled that, …according to Popper, it is not possible to prove scientific hypotheses; instead, they can only be falsified. This leads to two important consequences: on the one hand, the maximum in spreading velocity at intermediate surfactant concentrations is not a proof that Marangoni flow has any relevance for superspreading (apart from the fact that there are alternative explanations of the peculiar concentration dependence, even based on experimental facts, but not involving surface tension gradients). On the other hand, there is experimental proof that shows that superspreading only starts after an initial surface tension gradient has been eliminated. Summarizing the discussion about surface tension dynamics, there does not seem to be anything unusual concerning the surface tension behavior of the superspreading trisiloxane surfactants. The surface tension dynamics are orders of magnitude faster than the superspreading process, so any surface tension gradient does not have a chance to sustain (Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024). To complete citation, we note that, on occasion, Venzmer criticized not the validity of results observed but rather their interpretation.

A more recent contribution is by Kovalchuk et al. (2020). Like many other contributors to the study of superspreading, although there seems to be consensus that a positive spreading coefficient is necessary for complete wetting and that surfactants play a vital role in reducing interfacial tension, yet they continue diverging on the driving force behind superspreading. Nikolov et al. (2013) and Kovalchuk et al. (2020) debated about the spreading coefficient and the potential role of Marangoni flow, while Venzmer, as noted above, clearly dismissed Marangoni flow to maintain his proposed mechanism involving “rolling action” and the “unzippering” of dangling bilayers. Thompson (2018) stated, “The superspreading process could happen via a rolling action at the drop’s three-phase contact line, whereas the surfactant molecules are supplied through unzipping of bilayers formed by the superspreading surfactants.”

5 A drastically simplified model problem dealing with a couple of superspreaders provides unexpectedly acceptable results that fit well with experimental data: pros and cons and suggestions for future work

In view of the reflections presented in the preceding Section 4, we now focus attention on evolutionary aspects of archetypical superspreaders. Normally, we would predict results comparable with accepted experimental data. However, as noted earlier, there is no straightforward consensus on this phenomenon, although some clear concepts and conclusions are offered by Venzmer (2011), Venzmer (2021), Venzmer (2024), and Marques Silva et al. (2023) that we have discussed in extenso in Section 4.

The experimental and theoretical problem is an apparently complex interplay of several factors that influence the spreading process, such as surfactant properties (the molecular structure/phase behavior of the trisiloxane surfactants seems to be the crucial difference between a superspreader and a non-superspreader), surfactant transport, drop volume, oil layer thickness, Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces, Marangoni stresses, three dimensional (3D) geometry, and the presence of additional fluid at the leading edge. We focus on experimental data reported by Svitova et al. (1998) and Svitova et al. (2001).

In view of such complexity, we have also reduced to a minimum the problem in a first step in our exploration, with other steps to follow in the future. Thus, our minimal model is a drop made of surfactant in order to just explore the influence of surfactant properties, drop volume, and oil layer thickness. Another additional simplification was the consideration of two dimensional (2D) geometry that neglects azimuthal curvature; we understood that this limitation may significantly affect drop coalescence behavior in the liquid layer. Other items not considered, in this first approach, are surfactant solubility and the Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces. Such limitations drastically reduce the problem with the intention, as earlier noted, of exploring results in this first step, with other steps to follow in the future. We thus did not expect agreement with experimental data but merely indicated how the model can be improved in subsequent exploration of the superspreading problem.

We employed a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) approach using the volume of fluid (VOF) method with piecewise linear interface calculation (PLIC) to simulate the superspreading of trisiloxane surfactants (T6, T8) on hydrophobic liquid substrates. This method is well suited for the study of superspreading as it accurately resolves the considerable topological changes and complex interfacial dynamics inherent in the process. This computational framework provides key advantages that complement experiments: (i) the ability to systematically isolate and vary individual physical parameters, (ii) complete spatiotemporal resolution of flow fields and concentration gradients; (iii) cost-effective exploration of parameter spaces that are impractical to empirically investigate (Hirt and Nichols, 1981; Brackbill et al., 1992; Renardy et al., 2002; Zahaf et al., 2020; Gunjal et al., 2005; Lun et al., 1996; James and Lowengrub, 2004).

While results will be presented and discussed later, it appears that such computer-based simulation results show that drops of T6 and T8 surfactant only spread on mineral oil substrates when their concentrations exceed their respective critical wetting concentration (CWC). CWC is the minimum surfactant concentrations required for a solution to completely wet a hydrophobic substrate. For T6, the CWC is 0.03wt%, and for T8 it is 0.05wt%. The experimental study by Starov et al. (2010) provided CWCs of 5.52 × 10-4 mol/L (0.0335 wt%) and 7.9 × 10-4 mol/L (0.0548 wt%) for T6 and T8, respectively, resulting in a positive initial spreading coefficient.

In view of the commonly used typical experimental configurations and results reported in the literature, particular in Svitova et al. (1998) and Svitova et al. (2001), Figure 5 illustrates the computational domain and grid refinement used in our computer simulations. Restriction to a 2D geometry greatly reduces computer exploration while being accurate enough for homogeneous spreading conditions. The (x, y) quadratic grid computational area chosen is large enough to ensure that the geometric limits of the calculation do not interfere with the spreading boundary. The grid cells are refined to 10−4 by 10−4 units. A constant pressure boundary condition is imposed. The symmetry of the sides is adjusted to define a symmetrical model and minimize the size of the examination domain, which should result in increasing accuracy.

Figure 5. Computational domain and grid refinement used in a simulation of surfactant spreading on a mineral oil bilayer. Main panel shows 1 u × 1 u (arbitrary units) square domain representing a 1/100 u thick mineral oil layer (in red) and 1/10 u thick aqueous solution (in blue) containing surfactant, where u is an arbitrary unit. The smaller panel b) offers a zoom of a single cell within the domain, revealing a grid of smaller square cells with a spacing of 10−8 u2, providing a high resolution to accurately capture the fine-scale details of surfactant movement and distribution during spreading.

The surface tension at the mineral oil/air interface is 28.6 mN/m. The mineral oil/water interfacial tension is 52.4 mN/m. The surface tension of trisiloxanes at the air interface is 21 mN/m. However, the values used in the computer simulation are effective empirical inputs consistent with the surface tension of the mineral oil/air interface in the presence of a monolayer of adsorbed surfactant, which can be as low as a few tenths of a mN/m. A circular area of the same size as the experimental drop and quadratic regions corresponding to the mineral oil and water layers is marked with a volume fraction of 1; that is, the liquid phase. The computations have been performed with Δt = 3.10−6s time steps fixed.

The initial spreading velocities of the drops measured were 0.008 m/s for 0.5wt% T6 and 0.002 m/s for 0.1wt% T8. Courant number C = u.Δt/Δx is a crucial dimensionless quantity in CFD, which is a tool for evaluating the numerical scheme’s ability to produce stable and accurate results. C is the ratio of flow distance (uΔt/Δx) to cell size (Δx) in one-time step. When the time step Δt equals 3 × 10-6s and the space step Δx equals 10−4, then the two Courant numbers of T6 and T8 are 0.24 and 0.06, respectively. The fact that the Courant numbers of T6 and T8 surfactants are less than 1 is a good sign, as this suggests that the numerical simulations are stable and give accurate results.

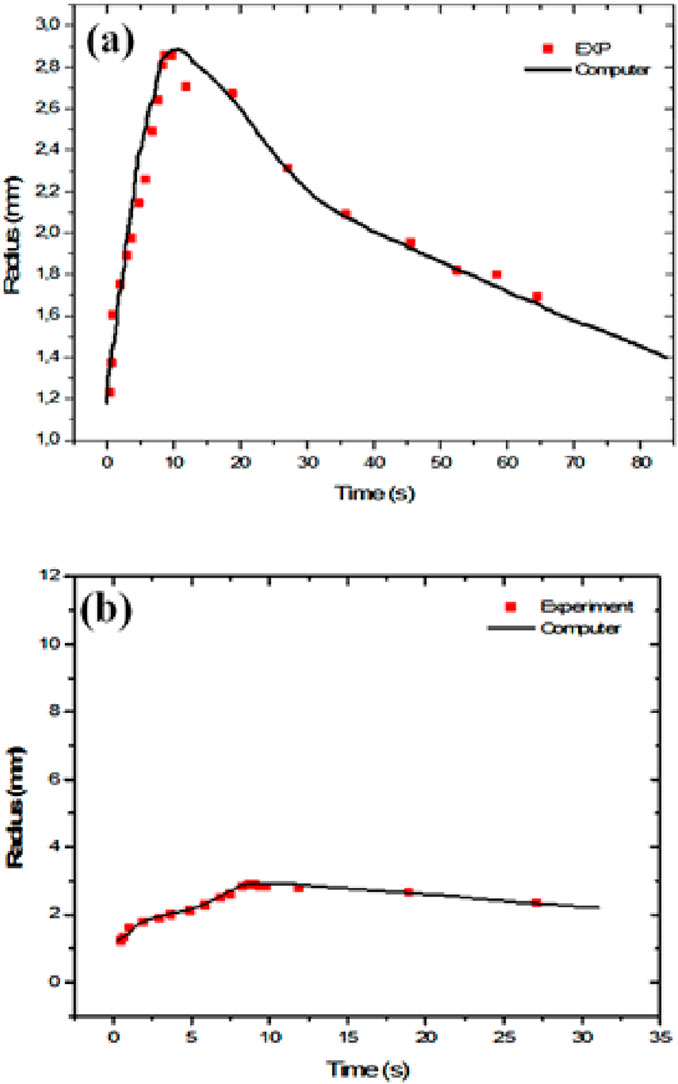

Figures 6, 7 depict computer-based predicted spreading behavior (solid lines) for trisiloxane T8. Our results are comparable with the reported experimental time evolution of the radii of the moving fronts after deposition of the trisiloxane surfactants T8 over a water layer thickness of h = 0.32 mm (Lee et al., 2008) and mineral oil layer thickness of h = 10 mm (Svitova et al., 2001).

Figure 6. Trisiloxane T8: time evolution of the spreading radius. Computer-based predicted spreading behavior versus experimental data for a 0.1wt% T8 surfactant solution (volume V = 1 mm3) (i) on a water layer h = 0.32 mm thick: computer results (blue solid line) and experimental data (red triangles) from Lee et al. (2008), and (ii) on an oil layer of thickness h = 10 mm: computer results (black solid line) and experimental data (red squares) at ambient relative humidity (35%–55%) from Svitova et al. (2001).

Figure 7. Trisiloxane T8: time evolution of the spreading radius. Computer predictions (solid line) of V = 1 mm3, 0.1wt% T8 drops on a h = 10 mm mineral oil layer compared with experimental data (red squares, from Svitova et al., 2001). Experiments conducted at 33%–35% ambient humidity. (a) Upper panel: long-term evolution scale. (b) Lower panel: behavior focusing on a shorter time lapse.

The spreading of a drop of trisiloxane T8 with a volume of 1 mm3, initially deposited with a quasi-spherical shape on water, has a rapid initial stage where the drop spreads considerably, quickly altering its shape and reaching a maximum surface area in a few seconds. This evolutionary behavior contrasts with that of the spreading of a similar drop (V = 1 mm3) on mineral oil, which is much slower, the drop having a more gradual progression and not reaching such an extensive surface area within the same time lapse. This difference in behavior highlights the significant influence of the substrate’s viscosity on the spreading dynamics (oil, 24 mPa s; water, 1 mPa s).

Numerical study of surfactant drop-spreading on mineral oil, performed using Ansys Fluent, tracks the temporal evolution of the drop radius

While Figures 6 (oil layer) and 7 share similarities in terms of surfactant, substrate, and comparison methodology, they differ in their focus on drop volume, time scales, and experimental humidity. Together, they offer a comprehensive picture of how the trisiloxane surfactant spreads over oil layers under varying conditions. In all cases, we note the unexpected but excellent agreement between our computer simulations and the reported experimental data. This is most remarkable in view of the drastic simplicity of our approach, which uses a drop composed only of surfactant.

Figures 8, 9 depict computer-predicted spreading behavior for T6. The former concerns the spreading behavior as drop volume changes, while the latter examines the spreading behavior as the thickness of the oil layer is varied.

Figure 8. Trisiloxane T6: time evolution of the spreading radius. Comparison of the experimental data (black squares) and computer-based predicted time evolutions (solid lines) of the radii on (a) upper panel, linear scale of the moving front for volumes V = 0.5 mm3 (blue line), V = 0.7 mm3 (red line), and V = 1 mm3 (black line) of the surfactant T6 drops onto mineral oil with h = 10 mm and at saturated relative humidity (100%). (b) Lower panel: replotted results and experimental data on a log–log scale. Experimental data for V = 1 mm3 for T6 are from Svitova et al. (2001).

Figure 9. Trisiloxane T6: time evolution of the spreading radius. Comparison of experimental data (black squares) and computer-based predicted time evolution (solid lines) of the radii on (a) upper panel, linear scale, and (b) lower panel, log–log scale of the moving front for thickness h = 5 mm (red solid line), h = 7 mm (green solid line), and h = 10 mm (blue solid line) for 0.5wt% surfactant T6 drops (V = 1 mm3) onto mineral oil at saturated relative humidity (100%). Experimental data for h = 10 mm reported by Svitova et al. (2001).

In Figure 8 (see also Table 1), our results show both the predicted and experimentally observed effects of increasing drop volume (V = 0.5 mm3, V = 0.7 mm3, V = 1 mm3) for the same mineral oil layer thickness h = 10 mm. Only the case of V = 1 mm3 corresponds to experiments (Svitova et al., 2001). The spreading parameters are detailed in Table 1. During the first stage, an exponential variation shows the increase of exponent α1 from 0.860 to 0.922, with an increasing drop volume from 0.5 mm3 to 1 mm3. In the second stage, the drop volume also controls the spreading exponent α2 by decreasing its value from −0.017 to −0.049 when the drop volume increases from 0.5 mm3 to 1 mm3. Accepting as reference values those given by Svitova et al. (2001), case V = 1 mm3 achieves a form of calibration of our computer simulation approach using a drop made of surfactant only.

Table 1. Computer-based predicted spreading parameter values derived from the temporal evolution of the spreading front for various T6 surfactant drop volumes on a thin mineral oil layer (h = 10 mm).

In Figure 9 (see also Table 2), we consider the influence of increasing mineral oil layer thickness (h = 5 mm, h = 7 mm, h = 10 mm) for drops of the same given volume (V = 1 mm3). Only the case h = 10 mm corresponds to experiments (Svitova et al., 2001).

Table 2. Computer-based predicted spreading parameter values derived from the temporal evolution of the spreading front for T6 surfactant drops on mineral oil layers of thicknesses h = 5, 7, 10 mm.

On a log–log scale (Figure 9B), no significant distinctions can be detected between the three curves since they are approximately parallel. The values of the spreading parameters are given in Table 2. For the first rapid stage of spreading, the exponential law exponent α1 depends on the oil layer thickness. The exponent decreases from 0.90 to 0.95 as the thickness increases from 5 to 10 mm. Moreover, in the subsequent retraction regime, the power law exponent α2 decreases from −0.023 to −0.049 as the thickness increases from 5 to 10 mm. As earlier mentioned, the spreading behavior depends on the length of the hydrophobic ethoxy chain/oxyethylene (CH2-CH2-O-). A thinner substrate allows for faster spreading due to the smaller volume of mineral oil. The spreading of T6 surfactant on the mineral oil increases the thickness of the substrate while decreasing the surface tension of the oil, ultimately resulting in a decrease in the power law exponent until saturation of the substrate occurs, from which the spreading coefficient decreases to a negative value. Thus, in the second stage, the values of the exponent are negative. Case h = 10 mm again provides a means of calibrating or checking our computer simulation approach using a drop composed of surfactant only.

Figure 10 (see also Table 3) depicts computer-predicted spreading behavior (solid lines) for both trisiloxanes T6 and T8. Focusing on spreading onto oil layers and subsequent retraction, the log–log plots in Figure 10 (upper and lower panels) permit easy identification of two different power law

Figure 10. Trisiloxanes T6 and T8: time evolution of the spreading radius. Computer-based predicted time evolution (log–log plots) of the radii of drops (V = 1 mm3) of (a) upper panel, 0.5wt% T6 (black triangles) and (b) lower panel, 0.1wt% T8 (black squares) for spreading on mineral oil layer with same thickness h = 10 mm and at saturated and ambient relative humidity >95% and 35%–55%, respectively. The two stages are fitted by power laws illustrating qualitative and quantitative differences between the two trisiloxanes.

Table 3. Computer-based predicted spreading parameter values (numerical) derived from the temporal evolution of the spreading front of T6 and T8 surfactant drops on a thin water layer compared with those derived from experimental data reported by Svitova et al. (2001).

A key distinction between the spreading behaviors of T6 and T8 lies in the presence and timing of the plateau phase. The T6 curve (Figure 10a) shows a distinct peak at approximately 10 mm and transitions into a clearly defined plateau phase within the first second, indicating a relatively rapid stabilization of the spreading. The increased number of oxyethylene groups (n = 6) in T6 is likely to promote faster initial spreading due to the enhanced hydrophilicity of this trisiloxane, leading to the earlier establishment of a stable contact line. In contrast, the T8 curve (Figure 10b) with a longer oxyethylene chain (n = 8) reaches its peak at approximately 2.8 mm and lacks a pronounced plateau. The absence of a clear plateau in T8 could also be related to the increased hydrophilicity imparted by the longer oxyethylene chain, which may delay the establishment of a stable contact line or promote greater sensitivity to the lower humidity conditions (35%–55%) compared to the saturated humidity (>95%) of the T6 experiment.

We now complete our presentation with a pictorial view (Figures 11–13) of the evolution of the spreading drop corresponding to the previous figures with their quantitative presentation of results (Figures 6, 8, 9). Figure 11 (companion to Figure 10b) depicts the computer-based predicted spreading behavior (solid line and corresponding attached illustrations) for trisiloxane T8, illustrating both quantitative and qualitative behavior observed in the simulations for a time lapse of approximately 90 seconds. Comparing these results to the experimental data of Svitova et al. (2001) confirms the validity of our computer simulation approach using a drop composed of surfactant only.

Figure 11. Trisiloxane T8: qualitative and quantitative time evolution of the spreading radius. Computer-based predicted temporal snapshot profile sequence for time instants t = 0 s, 4 s, 8 s, 10 s, 35 s, and 85 s of 0.1wt% T8 (volume V = 1 mm3) drop spreading on a mineral oil layer of thickness h = 10 mm at ambient relative humidity (35%–55%). Comparison is made with experimental data (black squares) from Svitova et al. (2001). Colors: yellow for surfactant, red for mineral oil, and cyan for water.

Figure 12 (companion to Figure 8) depicts the computer-predicted spreading time evolution of trisiloxane T6 drops of different volumes (V = 0.5 mm3, 0.7 mm3, and 1 mm3), illustrating their qualitative behavior observed in the simulations for a 1 sec. time lapse. Due to the hydrophobic nature of T6, its first spreading stage is such that a liquid film forms in the center, differing as the volume is increased, so that at time t = 1s it practically disappears for a volume greater than 1 mm3, agreeing with the results reported by Svitova et al. (2001).

Figure 12. Trisiloxane T6 (companion to Figure 6): computer-based predicted temporal snapshot profile sequence for time instants t = 0 s, 0.2 s, 0.35 s, 0.6 s, and 1 s of 0.5 wt% T6 drops spreading on a mineral oil layer of thickness h = 10 mm and saturated relative humidity (100%) for drop volumes V = 0.5 mm3, 0.7 mm3, and 1 mm3. Color labels: blue for air, yellow for surfactant, red for mineral oil, and cyan for water.

Figure 13 (companion to Figure 9) depicts the computer-predicted spreading time evolution of equal volume (V = 1 mm3) trisiloxane T6 drops spreading onto mineral oil layers of different increasing thickness: h = 5 mm, h = 7 mm, and h = 10 mm. It clearly illustrates the qualitative behavior observed in the simulations for a 1 s time lapse.

Figure 13. Trisiloxane T6 (companion to Figure 9): computer-based predicted sequence of snapshot profile sequence for time instants t = 0 s, 0.2 s, 0.35 s, 0.6 s, and 1 s of a 0.5wt% T6 drop spreading onto mineral oil layers h = 5 mm, 7 mm, and 10 mm thick at saturated relative humidity (100%) with volume V = 1 mm3. Color labels: blue for air, yellow for surfactant, red for mineral oil, and cyan for water.

Although our computer simulations provide valuable information, their conclusions should be considered as preliminary rather than definite, given the existing severe constraints of our minimal modeling framework. Moreover, the abovementioned Popper’s argument applies in principle. T12 has similar surface tension and other properties almost identical to T6 and T8, and it is not a superspreader. The minimal model we have used cannot provide this discrimination and, if applied to T12, will indicate a superspreading character, thus providing a strong con to the use of such minimal model. In terms of surface tension, as emphasized by Venzmer (2011), Venzmer (2021), and Venzmer (2024), there is no difference between T6, T8, and T12 except in terms of phase and spreading behavior. However, we may consider as a pro the fact that the minimal model captures, with unexpected precision, aspects of the experimental evolutionary trend in the superspreading process. We may thus hope that, in trying to explore a more physically acceptable model, we can build upon the approach followed here by completing the minimal model used with the addition of molecular structure and other factors after a first step, with other steps to follow.

6 Discussion and concluding remarks

Interfacial transport phenomena, particularly surface tension gradient-driven (Marangoni) flows with and/or without surfactants exhibiting diverse behavior, form a complex yet scientifically vital research domain with broad implications. We have tried to highlight some of their key mechanistic insights, knowledge gaps, and methodological advances in this research area, focusing on various specific cases.

Concerning insoluble surfactants—which have a tendency to dissolve in the bulk, but as they adsorb onto interfaces, they also form monolayers—two approaches exist, denoted as Gibbs and Langmuir monolayers with corresponding isotherms. Most studies overlook the kinetics of adsorption when the interface is at equilibrium, focusing instead on volatile surfactant-instigated surface instability. Among the few exceptions is Shkadov et al. (2004), who considered the adsorption–desorption kinetics for a falling aqueous solution along a vertical slope with Fick’s equation for the surfactant concentration profile. Further studies might provide a more complete picture of the role of surfactants in surface tension gradient-driven flows and transport.

Concerning self-propelled active drops, Rednikov et al. (1994) did not invent microfluidics in 1994. However, while their proposal passed practically unnoticed, if not deemed unfeasible, they pioneered a path currently used today by the microfluidics community. Clearly, microfluidics was “invented” in nature by trees and other plants, and they were the “masters” of microfluidics much earlier than humans. Microfluidics can deal with processing and manipulating small amounts of fluid using channels with dimensions 10–100 μm (recall xylem conduits in trees) and velocities in the range 1–10 μm/s or higher (recall dm to m per hour in trees). Microelectronic technologies and microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) not readily available in the 1990s have been indispensable for the development of microfluidics. With miniature devices, we can manipulate volumes of fluids in the order of nano- to microliters. There is today a huge diversity of microfluidic devices used in scientific and technological applications. Nanofluidics dealing with fluids moving along, such as in 102 nm and lower scale channels, is now developing well.

Concerning sap ascent in the trees, in 1952, R. D. Preston (Preston and Frey-Wyssling, 1952) investigated the effects of pairs of transverse cuts separated longitudinally but coming from opposite sides and overlapping (Mackay and Weatherley, 1973). Little effect on transpiration took place if the distance between such cuts was greater than a critical distance, which is roughly double the typical length of the xylem conduits in the given tree. Tall trees survived, and so it is clear that overlapping cuts in trunks geometrically destroying the continuity of all portions of conduits do not abolish normal water uptake; this confirms the ability of plants to enable water flow despite gaps along the xylem. A related question is how grafted trees solve this problem. Adding to the cohesion-tension theory, the role of Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces might prove useful for a more complete understanding of the overall process of sap ascent. Note the final sentence in the 2016 review (Jensen et al., 2016): “From the point of view of a physicist, plants remain full of mysteries.” For a 2017 review see Venturas et al. (2017).

Concerning the phenomenon of superspreading, we have already noted challenging and intriguing if not confusing comments. As Venzmer (Venzmer, 2011; Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024; Marques Silva et al., 2023) insisted, molecular structure critically influences superspreading results, noticeable by contrasting, for instance, trisiloxanes T6 and T8 against T12 performance, where the hydrophilicity–hydrophobicity balance dictates their functionality. Future research should systematically explore structural factors, including ethoxy chain length, molecular aggregation (bilayers vs. micelles), and solubility–adsorption kinetics.

Additionally, while many (Nikolov et al., 2002; Nikolov and Wasan, 2011; Nikolov et al., 2013; Nikolov and Wasan, 2015; Nikolov et al., 2021; Venzmer, 2011; Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024; Marques Silva et al., 2023) have focused on solid substrates, Kovalchuk et al. (2024) (also Ivanova et al., 2010) utilized liquid substrates. Care is to be taken if the results obtained from spreading on a liquid substrate are to be compared to those obtained from spreading on a solid substrate for various reasons. i) On a solid, the TPCL experiences the “no-slip” condition, which leads to complex hydrodynamic effects, whereas a liquid substrate lacks this condition. ii) On a solid, surface roughness and heterogeneity disrupt the adsorption of the surfactant, resulting in heterogeneous propagation, whereas on a liquid with its smooth and homogeneous interface, there is uniform adsorption, except in the particular case of self-solubilizing surfactants. iii) Measuring interfacial tensions on a solid surface is inherently more challenging (e.g., not measured directly) than on a liquid surface. The above arguments demonstrate the need for a multifaceted approach to unraveling the apparent complexity of the superspreading phenomenon.

It should be kept in mind that the ultimate stress test for any theory, model or hypothesis is to explain the difference in spreading performance between two chemically quite similar classes of trisiloxane surfactants superspreaders which are forming bilayer aggregates in aqueous solutions, and the more hydrophilic, micelle-forming non-superspreaders, which are carrying somewhat longer polyethers (Venzmer, 2011; Venzmer, 2021; Venzmer, 2024). In Venzmer (2024), he also stated, “There is nothing unusual in the case of the superspreaders; all findings can be explained by basic physical chemistry,” and, “Fortunately, upon taking a closer look at the interfacial behavior of trisiloxane surfactants, one can conclude that there is nothing mysterious behind trisiloxane superspreading.” He did clarify in Venzmer (2024) that the “mystery” concept in connection with superspreading comes from Nikolov et al. (Venzmer, 2011). The final statement in Venzmer (2024) is

The transport of the surfactant molecules over macroscopic distances, which is one of the challenges during the superspreading process would then be a combination of a “rolling action” at the leading edge with a supply of the surfactants by “unzippering” of the hanging bilayers all over the surface of the drop.

As already noted by Churaev et al. (2001b), the role of Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces demands consideration, particularly when approaching the final stage of superspreading (we earlier recalled that, for example, a gradient of film thickness leads to gradient of Derjaguin pressure). As they noted: “The problem demands further investigation in more detail with application of different structure-sensitive methods and computer simulations” (Churaev et al., 2001b). Note that gradients of Derjaguin (DLVO) pressure/surface forces stabilize ultrathin precursor films and drive lateral extension; hence, DLVO is important even though often neglected.

Indeed, it seems overall that research on the superspreading phenomenon could benefit from integrating different methodologies for a more comprehensive understanding. Specifically, combining the simulation approach like that used in this study with that of the CWC and CAC determination methods of Ivanova et al. (2010) could provide a more complete picture of the superspreading phenomenon. Simulating spreading across a range of surfactant concentrations, as in Ivanova et al. (2010), would reveal more intricate details of the spreading behavior, and comparing simulations of spreading on both liquid and solid substrates could offer valuable insights into the mechanisms that drive this phenomenon. From a naïve approach, is it that we have one too many variations on the superspreading phenomenon?

Finally, numerical modeling offers unparalleled advantages in studying interfacial phenomena, combining precision, efficiency, and insight. Its accuracy is validated through experimental agreement (e.g., drop radius evolution within <5% error in CFD simulations), while cost-effectiveness eliminates the need for laborious laboratory work. Simulations reveal sub-resolution mechanisms—such as nanoscale surfactant adsorption—inaccessible to experiments. The flexibility to test hypotheses (e.g., substrate wettability and surfactant structure) and integrate multi-scale physics (continuum CFD with molecular dynamics) is expected to enhance predictive power. Although simplifications (e.g., 2D geometry and equilibrium assumptions) exist, sensitivity analyses and adaptive methods mitigate the limitations. Coupled with experimentation, numerical tools can bridge theory and application. This synergy underscores numerical modeling as indispensable for unraveling complex interfacial dynamics.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

HZ: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Software, Formal Analysis, Validation, Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. HA: Formal Analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Software. MGV: Validation, Visualization, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Software.

Funding

The authors declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgements

Hanene Zahaf and Hocine Alla are indebted to Prof. Olaf Deutschmann, Director of the Institute for Chemical Technology and Polymer Chemistry and at the Institute of Catalysis Research and Technology (National Lab) at Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), for allowing them access to his laboratory and especially to Martin Wörner, Head of the Multiphase Flow Group (from KIT, Germany). They also wish to express their appreciation to Thibault Roques Carmes (from ENSIC-Nancy, France) and to Prof. Marco Marengo (University of Pavia, Italy) for many valuable and inspiring discussions. The authors are also grateful to Joachim Venzmer and Prof. Ilia Roisman for information and suggestions that assisted a better understanding of basic aspects of the superspreading phenomenon. Hocine Alla is grateful to Prof. Marisol Fernandez, Director of the Instituto Pluridisciplinar, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, for the hospitality offered during two visits to her institute that permitted the research collaboration leading to the present contribution. Finally, the authors wish to express their gratitude to the referee for invaluable suggestions that helped improve the presentation of our arguments.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note