- 1Center for Yunnan Plateau Biological Resources Protection and Utilization & Yunnan International Joint Laboratory of Fungal Sustainable Utilization in South and Southeast Asia, College of Biology and Food Engineering, Qujing Normal University, Qujing, China

- 2Center of Excellence in Microbial Diversity and Sustainable Utilization, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- 3Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- 4Zest Lanka International (Private) Limited, Polonnaruwa, Sri Lanka

- 5Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Eastern University Sri Lanka, Chenkalady, Sri Lanka

- 6Office of Research Administration, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand

- 7Department of Botany, Faculty of Natural Sciences, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nugegoda, Sri Lanka

- 8College of Biodiversity Conservation, Southwest Forestry University, Kunming, China

Pigmented Basidiomycete fungi are emerging as multifunctional and environmentally friendly substitutes to man-made food coloring. In addition to their bright colors, pigments from these fungi, including melanin, pulvini acids, carotenoids, and phenoxazines, also exhibit potent antioxidant, anti-microbial, and even potential therapeutic effects. Fungal pigments offer greater stability under processing conditions compared to those of plant origin and can be cost-effectively produced by biotechnological culture, particularly agro-waste-based fermentation systems. This review provides an overview of the chemical diversity, biosynthesis, and extraction of pigments from food and non-food Basidiomycetes such as the genera Cantharellus, Pycnoporus, Boletus, Pleurotus, and others. Particular emphasis is on their applications in the food and nutraceutical industries, challenges in scaling up and regulatory aspects, and future prospects of fungal biotechnology as a renewably available source of natural pigments.

1 Introduction

Natural pigments derived from microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, have garnered increasing attention due to their biocompatibility, bioactivity, and potential for sustainable production (Delna et al., 2025). Among these, fungal pigments, especially those from Basidiomycetes, are often more promising than bacterial pigments due to their higher stability, broader color range, and easier scalability through fermentation. The global food market is witnessing unprecedented shifts toward clean-label, plant-based, and sustainable foods, of which natural colorants form a rapidly growing market. This shift is driven by growing consumer aversion toward artificial food colorants, such as tartrazine, sunset yellow, and erythrosine, that have been linked with health problems ranging from child behavioral abnormalities, allergies, and potential carcinogenicity (European Food Safety Authority, 2021; de Oliveira et al., 2024). Thus, regulatory agencies like the FDA and EFSA are increasingly certifying natural alternatives (European Food Safety Authority, 2025; FDA, 2025). The scale of additive use is substantial; while the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lists over 3,000 food additives, industry estimates put 8,000 to 10,000 individual chemicals in the American food system when including GRAS-classified and self-confirmed ingredients (Neltner et al., 2011; Leasca, 2024).

This can be observed in the global pigment market, worth around 9.7 million metric tons in 2024 and expected to grow from a worth of USD 26.6 billion in 2025 to more than USD 41 billion in 2033. While a lot of volume previously headed to the paint and textile industries, pigment use in food items has risen substantially due to the need for safer, microbe- or plant-derived colorants (Venil et al., 2014; Chatragadda and Dufossé, 2021; Pillai et al., 2024; Pigments market, 2024; IndexBox, 2025). However, most plant colorants are still handicapped by problems like seasonality of supply, geographically restricted availability, and process condition instability. While bacterial pigments offer a microbial alternative, they often face limitations in color diversity, yield, and scalability compared to fungal alternatives. In this context, Basidiomycete fungal pigments are a perfect, multi-purpose, and ecologically friendly choice. Basidiomycete pigments are more stable to heat, light, and pH than the majority of plant and Ascomycete pigments. Apart from that, they possess a rich variety of classes that vary from melanin, pulvini acid derivatives, styrylpyrone derivatives, terphenylquinones, phenoxazines, to carotenoids, which possess intrinsic bioactive activity such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory activities (Velíšek and Cejpek, 2011; Stadler and Hoffmeister, 2015; Lin and Xu, 2020; Negi, 2025).

While pigmentogenic bacteria and Ascomycetes have been widely studied (Nigam and Luke, 2016), Basidiomycete pigments offer distinct advantages of greater environmental stability and economic scalability through fermentation. Basidiomycetes can be cultivated year-round on agro-industrial wastes, such as sugarcane bagasse, corn husk, and coffee grounds, through solid-state or submerged fermentation, making scalable, sustainable production and a circular bioeconomy feasible (Zhang et al., 2021). Fungi like Pleurotus ostreatus, Cantharellus cibarius, Pycnoporus cinnabarinus, and Laetiporus sulphureus are of particular interest due to their pigment composition and GRAS potentiality, as compounds like cinnabaric acid and laetiporic acid show intense coloration as well as potent bioactivity (Velíšek and Cejpek, 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2017; Singh et al., 2025). The relatively underexploited value of pigment-producing Basidiomycetes, combined with their inherent functionality and scalable production, positions them at the forefront of future natural food coloring. This review provides a comprehensive analysis of the chemical diversity, biosynthesis, and extraction of pigments from a range of edible and inedible Basidiomycetes. Special emphasis is given to applications in the food and nutraceutical industries, the issues encountered at the scale-up and regulatory approval stages, and the future prospects of fungal biotechnology as a sustainable and functional natural pigment source.

2 Major pigment classes from basidiomycetes: chemistry and biosynthesis

2.1 Pulvinic acids and derivatives (yellow to orange)

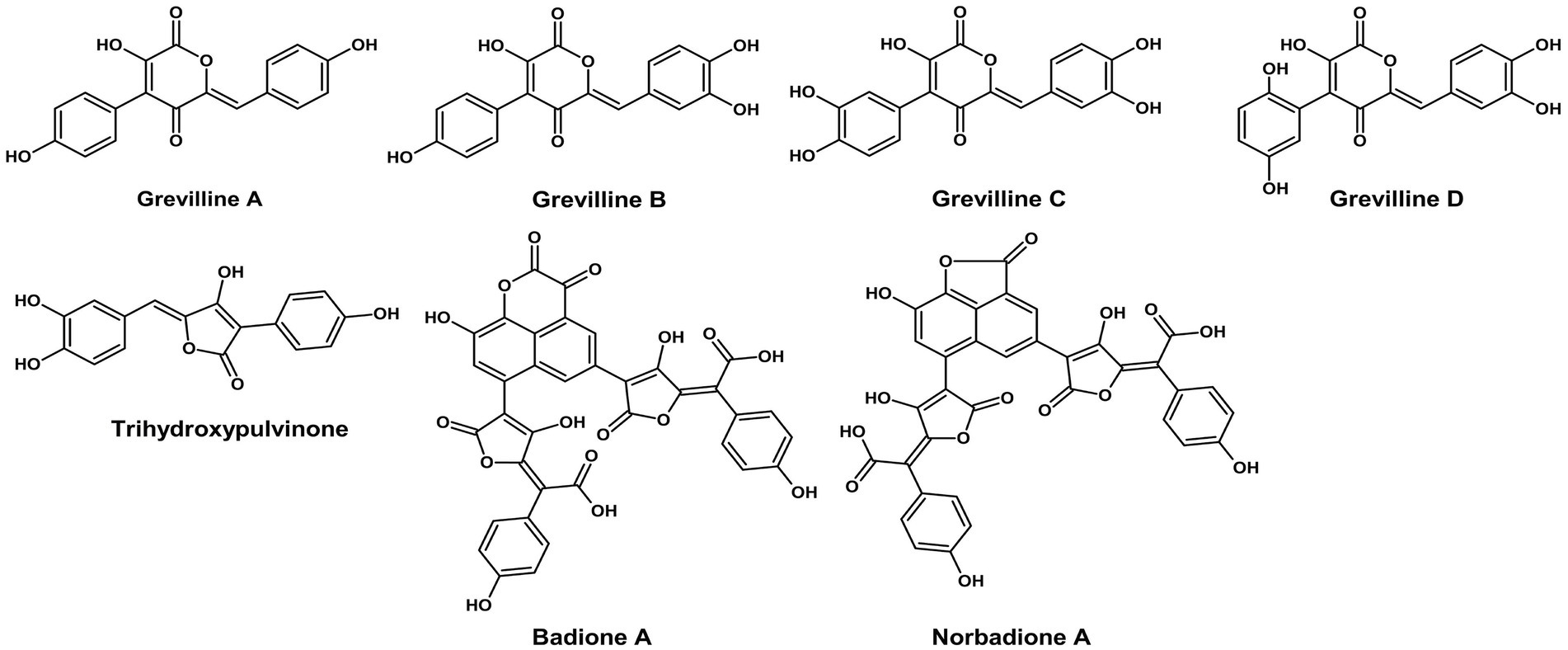

Pulvinic acid derivatives are yellow-orange pigments predominantly found in Basidiomycetes. For instance, Suillus grevillei produces grevillins and trihydroxy pulvinic acid, while Boletus badius yields badione A and norbadione A, which create bright yellow to golden brown hues (Figure 1). These compounds exhibit strong metal-chelating and antioxidant properties, making them highly suitable for natural food applications, such as snack coatings, cheese substitutes, and spice powders. Relative to the pigments of Ascomycetes, the distinctive structure and dual purpose of the pulvinic acids reflect the sophisticated biosynthetic abilities of the Basidiomycetes. According to Lin and Xu (2023), these pigments are included within the broad classes of fungal pigments and represent a characteristic group of the Basidiomycota.

2.2 Polyketide pigments biosynthesis in basidiomycota

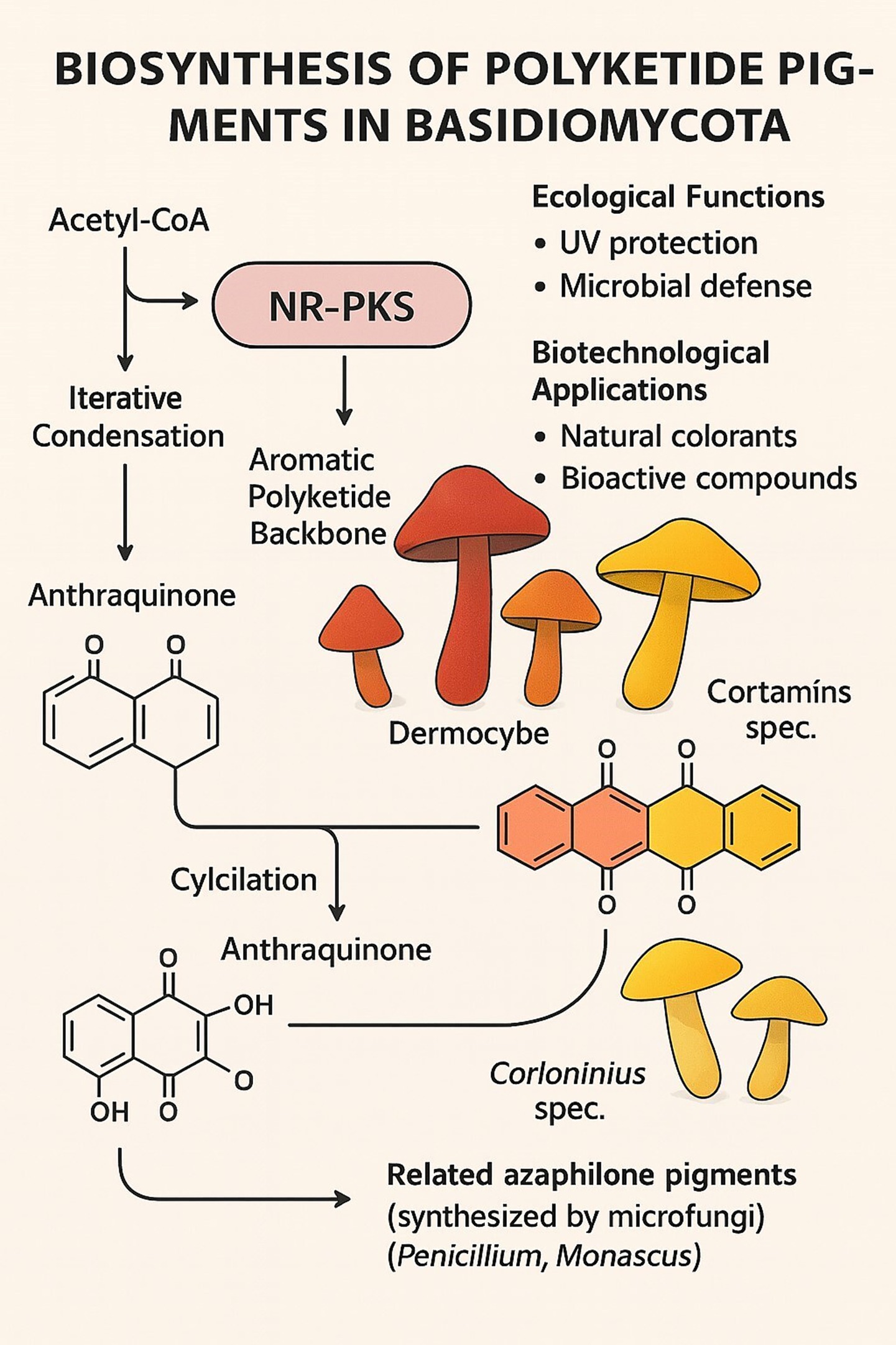

Basidiomycota polyketide pigments are primarily biosynthesized by the action of type I non-reducing polyketide synthases (NR-PKSs), which drive the synthesis of complex aromatic compounds (Figure 2). This section details the major classes of these pigments and the unique biosynthetic machinery that produces them.

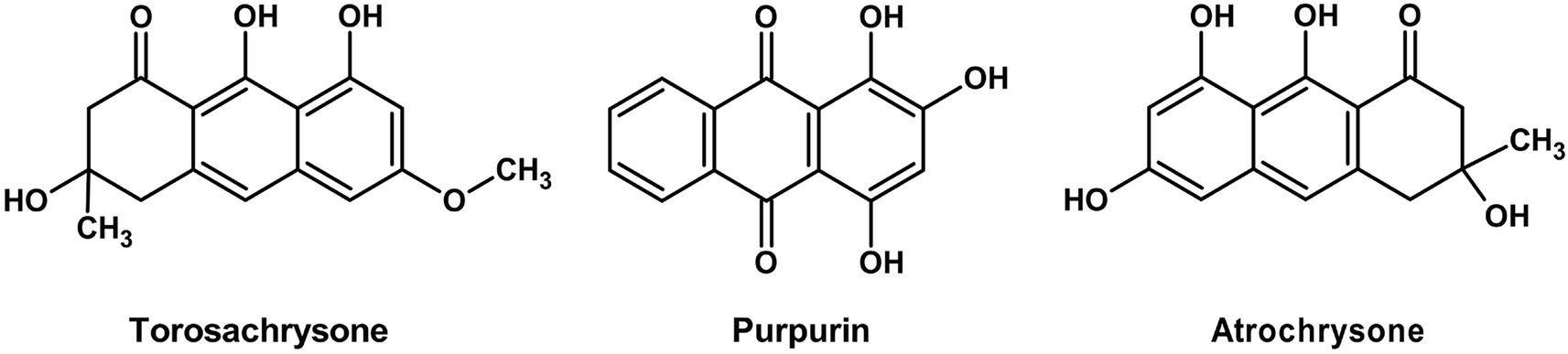

2.2.1 Anthraquinones

Anthraquinones are very typical polyketide pigments responsible for the deep red, orange, and yellow fruiting body colors in species such as Dermocybe and Cortinarius (Gill et al., 1992; Haritha and dos Santos, 2021). The pigments are biosynthesized through iterative condensation of acetate units derived from acetyl-CoA using NR-PKS enzymes as catalysts. The resultant polyketide backbone is then subjected to typical cyclization and oxidation reactions, which in most instances are catalyzed by tailoring enzymes, to yield the characteristic anthraquinone structure. Besides their role in coloration, pigments play ecological roles as UV screens and predators- and microbes-defense compounds and hold valuable biotechnological potential as natural dyes and bioactive molecules (Haritha and dos Santos, 2021).

2.2.2 Styrylpyrones

A significant class of polyketide-derived pigments in Basidiomycota is the styrylpyrones, notably produced by therapeutically relevant genera such as Phellinus and Inonotus (Lee and Yun, 2011). Their biosynthesis proceeds through a type III polyketide synthase (PKS) that catalyzes the condensation of malonyl-CoA with a cinnamoyl-CoA starter unit, followed by cyclization (Löhr et al., 2023). These yellow pigments are polyphenolic compounds with demonstrated antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Structurally, they exhibit convergence with plant flavonoids (Lee and Yun, 2011). While often overlooked in favor of high-molecular-weight polysaccharides like β-glucans, styrylpyrones represent a fascinating group of natural products with potential for functional food formulation and synergistic applications with other fungal polyketides (Olennikov and Gornostai, 2023).

2.2.3 Biosynthetic machinery of basidiomycete polyketides

The core enzymatic machinery for polyketide pigment synthesis in Basidiomycota consists of non-reducing PKSs (NR-PKSs). These mega synthases construct aromatic polyketide backbones with limited reduction, which facilitates the formation of quinone and aromatic structures found in pigments like anthraquinones and styryl pyrones.

A key feature of many basidiomycete NR-PKSs, such as Cortinarius odorifer CoPKS1/4, is their distinct domain architecture (KS-AT-PT-ACP-TE; Löhr et al., 2022). This architecture includes a product template (PT) domain that guides specific cyclization and a thioesterase (TE) domain that catalyzes the release of the full-length polyketide chain. This iterative catalytic mode generates remarkable structural diversity, which is not easily achieved by plant or bacterial PKS systems. These enzymes tend to catalyze the formation of hepta- and octaketides, yielding precursors of the ubiquitous pigments emodin and rufoolivacin.

Evolutionarily, the NR-PKSs of basidiomycetes belong to a divergent clade from their ascomycete counterparts. This is highlighted by comparison with azaphilone pigments, the homologous polyketides, which are produced by microfungi such as Penicillium and Monascus (Keller et al., 2015). Similar biosynthetic pathways notwithstanding, the hallmark difference lies in the fact that many ascomycete anthraquinone synthases rely on external thioesterases, whereas many basidiomycete enzymes possess an integrated TE domain. This enzymic divergence emphasizes a divergence in fungal secondary metabolism that occurs during evolution, even as both groups converge to the formation of intricate aromatic pigments.

2.3 Carotenoids (golden yellow)

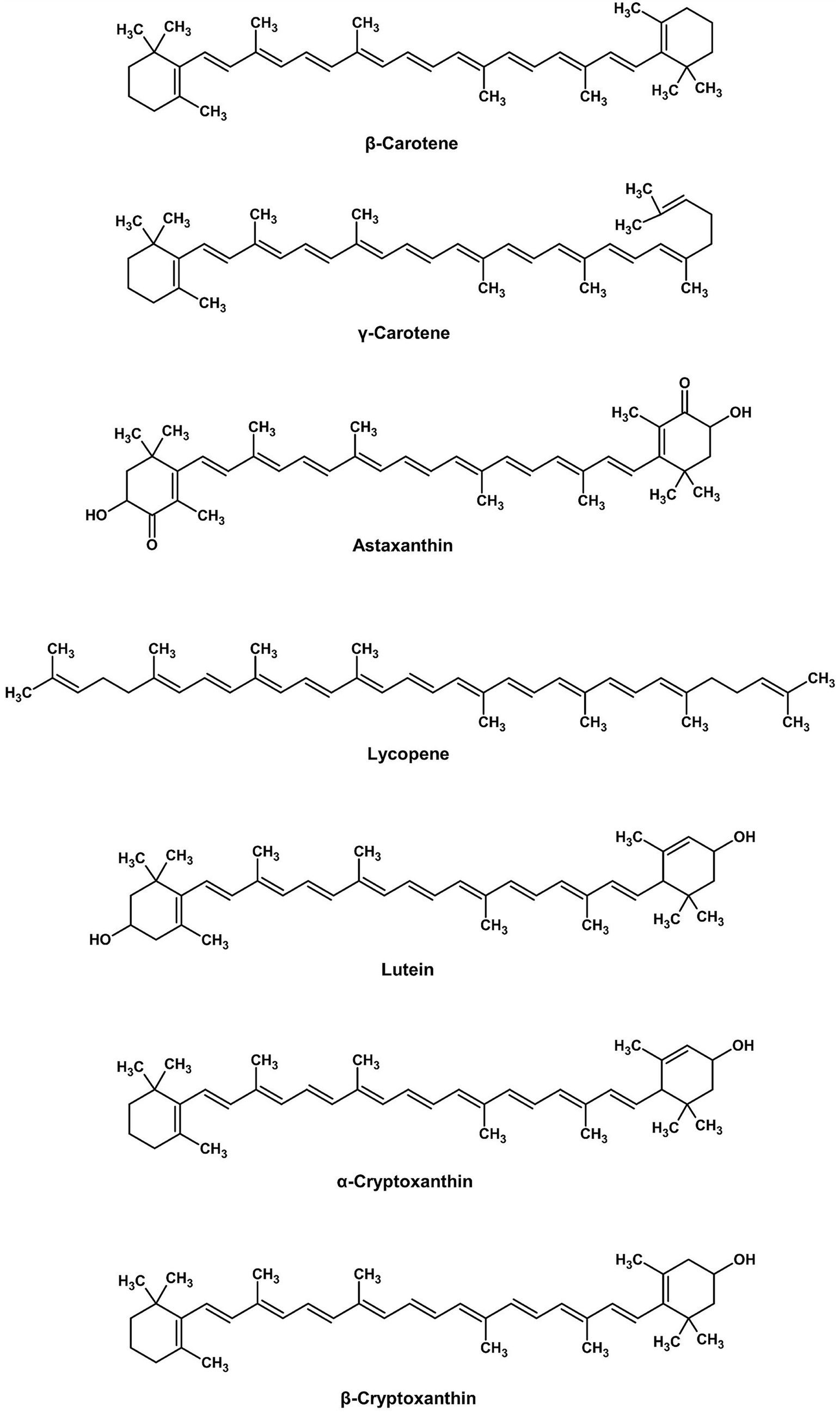

Cantharellus cibarius produces β-carotene and lycopene (Figure 3), lipid-soluble pigments that have excellent antioxidant activity, enhancing fat-containing foods such as butter substitutes and sauces. These pigments have good thermal and light stability over plant origins. Besides direct coloring, fungal metabolites interact synergistically with other pigments, enhancing the total effect. Moreover, even non-pigment fungal compounds can significantly improve the stability of industrial colorants, thereby extending their shelf life and performance.

2.3.1 Carotenoid biosynthesis in basidiomycota

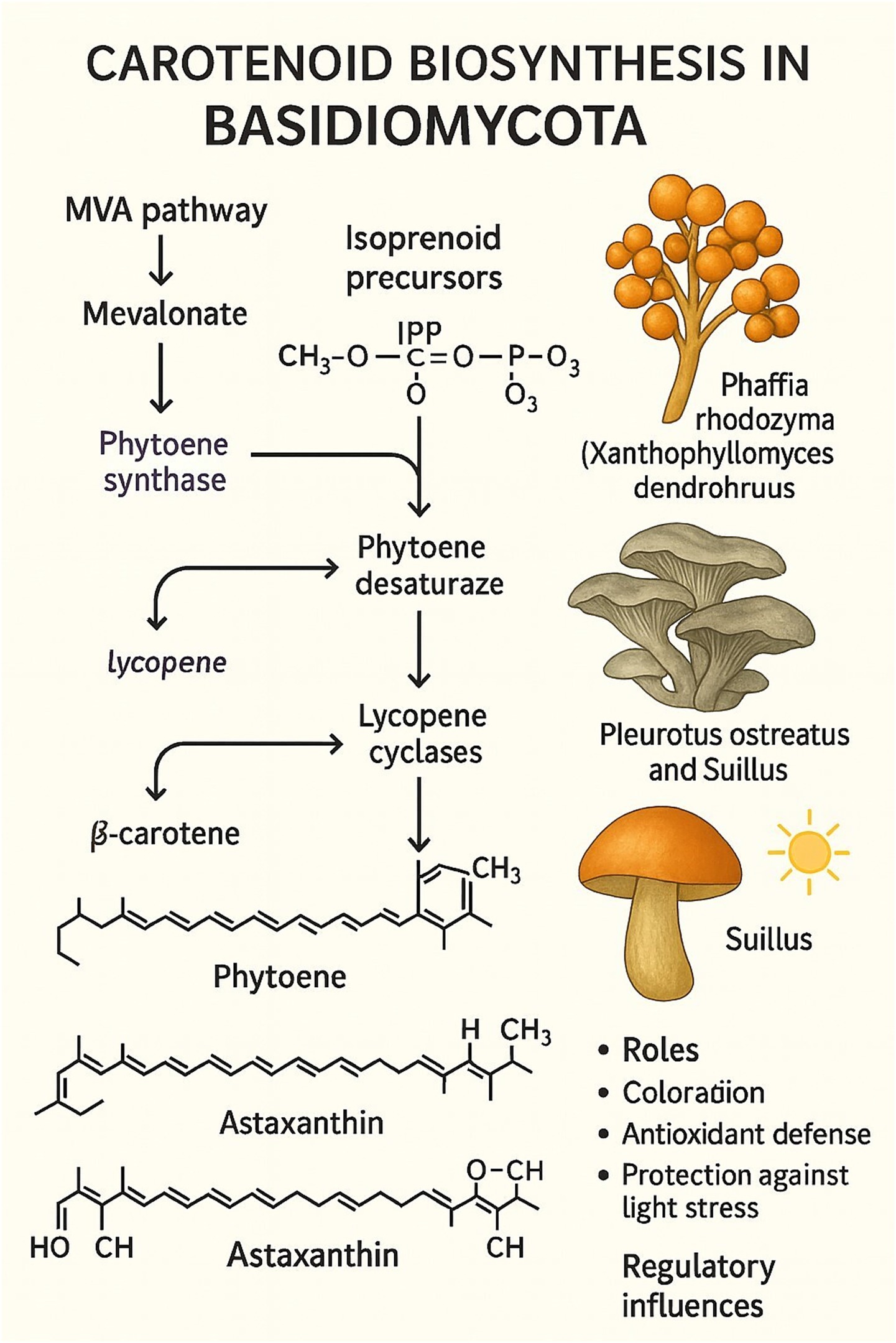

Carotenoids in Basidiomycota are terpenoid pigments synthesized from the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, which produces the essential isoprenoid precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP). The subsequent biosynthetic pathway proceeds through a defined series of enzymatic reactions to form colored carotenoids (Figure 4). The pathway begins with the condensation of IPP and DMAPP to form the C20 backbone, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP). Two molecules of GGPP are then condensed tail-to-tail by the enzyme phytoene synthase to produce the first colorless carotenoid, phytoene. This compound is subsequently desaturated by phytoene desaturase, a series of reactions that introduce double bonds to form the red pigment lycopene. Finally, lycopene cyclase enzymes catalyze the formation of cyclic end groups, converting lycopene into colored carotenoids such as γ-carotene and β-carotene.

Apart from contributing yellow, orange, or red pigmentation to basidiomycete fruiting bodies, these pigments are critical for antioxidant protection and light stress protection (Avalos and Limón, 2015; Haritha and dos Santos, 2021). One of the most extensively researched carotenoid-producing Basidiomycota is Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous (teleomorph of Phaffia rhodozyma), a producer of astaxanthin that exhibits strong antioxidant activity and has extensive applications in aquaculture, cosmetics, and functional food products (Martínez-Moya et al., 2021).

Species such as Pleurotus ostreatus and those in the genus Suillus sequester β-carotene, a pigment that regulates their antioxidative stress protection and coloration (Haritha and dos Santos, 2021). The biosynthetic regulation of these compounds is typically linked to environmental stimuli such as light and oxidative stress, but their regulatory mechanisms are less characterized than in microfungal models. While Basidiomycota-specific carotenoid pathways tend to preserve their core enzymology, they exhibit characteristic pigment compositions and ecological and physiological roles. In contrast with the model microfungal targets of industrial pigment production, carotenoid-producing basidiomycetes represent under-exploited but promising sources of biotechnological pigments.

2.4 Phenoxazines (orange to red)

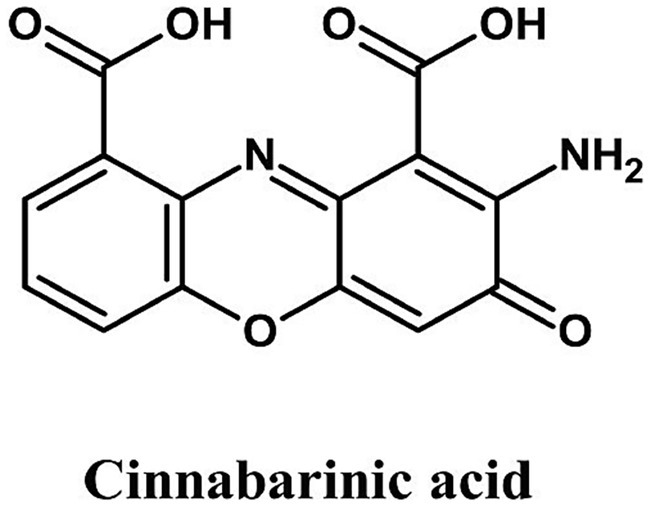

Phenoxazines are tricyclic heterocyclic compounds whose core structure consists of a fused ring system containing oxygen and nitrogen atoms. In fungi, they are typically synthesized through the enzymatic oxidation and dimerization of precursor compounds. A well-known biosynthetic route involves the laccase-mediated coupling of ortho-aminophenols, resulting in the formation of the distinctive phenoxazine ring. A prominent example is Pycnoporus cinnabarinus, which produces cinnabarinic acid (Figure 5), an orange-red pigment with applications in bakery toppings, fruit glazes, and confectionery. This type of pigment, however, has yet to be fully exploited since wild-type strains produce it in low yield.

2.5 Melanins (black to brown) and UV-responsive pigments in basidiomycetes

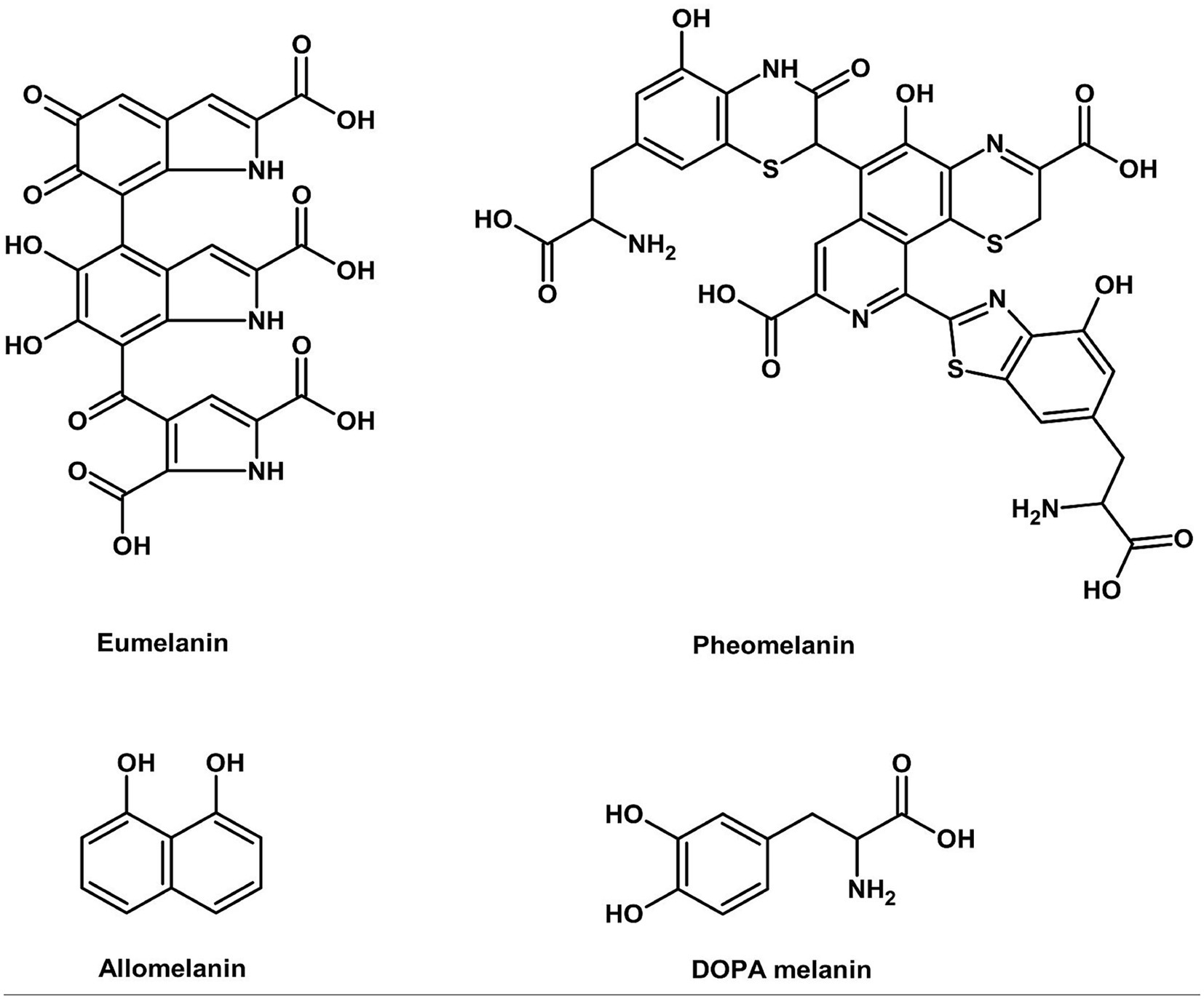

Fungal melanins (Figure 6) are one of nature’s most functional biomaterials with exceptional antioxidant and radioprotective activities through efficient free radical scavenging and electromagnetic wave absorption (Mattoon et al., 2021).

The superior function of the melanin is attributed to the stable phenolic radicals within its complex polymeric network, while multiple carboxyl groups enable exceptional heavy metal chelation, broadening its functional applications from pigmentation to medical radiation shielding and environmental remediation (Mattoon et al., 2021).

In Basidiomycetes, P. ostreatus (black, yellow, and pink strains) and Auricularia auricula-judae produce melanins of different colors depending on the eumelanin to pheomelanin ratio. The melanins also possess potential applications as natural substitutes for caramel colorants used in soft drinks and sauces, with the added benefit of protection against UV light and extended shelf life. The enzymatic melanin biosynthetic pathway in such fungi shares fundamental similarities with that of human tyrosinase, tyrosine hydroxylase, and DOPA oxidase activities (Hornyak, 2018). There are, however, substrate binding pocket variations between fungal and human tyrosinases and the absence of cross-kingdom efficacy of thiamidol-type inhibitors, which suggests Basidiomycete melanins are more resistant to degradation by human skin enzymes and potentially more stable food colorants.

Besides UV protection, Basidiomycete melanins have strong radioprotective activity. Accordingly, in murine models, A. auricula-judae melanin provided 80% survival after lethal 9 Gy irradiation, better than synthetic melanin by dual Compton scattering and free radical scavenging mechanisms (Revskaya et al., 2012). All of this makes them promising bioactive materials for radiotherapy adjuvants, food for space missions, and nuclear event emergency rations. Functional variation is important in melanins: the darker-gray P. ostreatus exhibits greater anticancer activity toward HT-29 colon carcinoma cells, but its antioxidant activity is surpassed by that of yellow P. cornucopiae, illustrating how biological activity and functional trade-offs are influenced by pigment class (Kim et al., 2009).

Some Basidiomycetes also produce UV-reactive pigments in photoprotection. Melanized fungi, such as Cryomyces antarcticus (Pacelli et al., 2020) and dark-pigmented forms of Pleurotus, produce UV-protecting melanins that could be applied as natural alternatives to chemical UV protectants in functional foods and biodegradable packaging materials. Carotenoid- and mycosporine-producing mushrooms, such as Pycnoporus, and high-altitude yeasts (Libkind et al., 2009) exhibit enhanced carotenoid and mycosporine production under UV stress. These traits could be utilized in outdoor or controlled-environment systems for production. Control of the light regime is a useful method for optimizing pigment production and activity. Shiraia bambusicola, for example, grown under alternating 24-h light/dark cycles, showed an improvement of 73% in hypocrellin pigment production (Sun et al., 2018). Parallel approaches would stimulate phenoxazine accumulation in Pycnoporus or carotenoid levels in Cantharellus. Observe that light-dependent pigment responses are taxon-specific; in Monascus, red light causes pigment production and blue light inhibits it, while Basidiomycete pigments such as cinnabarinic acid show contrary responses. This emphasizes the necessity for taxon-specific light regulation in controlled fermentation and industrial biotechnological processes. Combined, these attributes demonstrate the multifaceted potential of Basidiomycete melanins and UV-inducible pigments as sustainable, bioactive dyes with potential applications in food conservation, health enhancement, and the development of green materials.

2.5.1 Melanin biosynthesis pathways in basidiomycota

Eumelanin-type pigments in mushrooms such as Agaricus bisporus and Russula nigricans are produced via the gamma-glutaminyl-4-hydroxybenzene (GHB) pathway. The biosynthetic pathway is identical to melanin biosynthesis in animal tissues. Cata-lytic oxidation of GHB by tyrosinase results in the formation of eumelanin pigments, with nitrogen being relocated from the glutaminyl unit, but not to the glutamyl moiety, to the pigment molecule. Such new nitrogen supplements have nutritional significance when melanins are employed as food functionality or pigment, bestowing nitrogenous value to foods and enhancing pigmentation. Despite having been documented since 1980, the mechanism remains unexplained (Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012; Upadhyay and Xu, 2018).

Fungal melanin pigments are black, high-molecular-weight polymers whose primary protective functions are against environmental stresses, including ultraviolet (UV) light, oxidative stress, and desiccation. Melanin biosynthesis (Figure 7) in Basidiomycota typically occurs via two biosynthetic pathways: the L-DOPA (3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine) pathway and the DHN (1,8-dihydroxynaphthalene) pathway (Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012; Upadhyay and Xu, 2018). The pathway of L-DOPA starts with the enzymatic oxidation of L-tyrosine to L-DOPA, which is oxidized to dopaquinone. Spontaneous and enzymatic conversion results in DOPA-melanin, a eumelanin-type melanin.

The process is enzymatically catalyzed by tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1), which hydroxylates tyrosine and oxidizes L-DOPA, and by laccase (EC 1.10.3.2), which oxidizes phenolic intermediates to polymerize (Bell and Wheeler, 1986; Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012). Various Basidiomycota contain this pathway, e.g., Auricularia auricula-judae causes L-DOPA-induced precipitation of melanin in fruiting bodies (Upadhyay and Xu, 2018). Blue light significantly stimulates the genes of melanin laccase and tyrosinase in Morchella sextelata (a morel fungus with a Basidiomycota-like habit), linking melanogenesis to photomorphogenesis in mushroom-forming fungi (Wang F, et al., 2021). It is important to note that while Morchella produces a mushroom-like fruiting body, it is taxonomically a member of the Ascomycota, not the Basidiomycota. This indicates that the L-DOPA melanin pathway, while predominant in Basidiomycota, can also be present and functionally significant in certain Ascomycetes.

The common DHN pathway of Ascomycota, including Aspergillus and Fusarium, starts with a pentaketide skeleton formed by the action of polyketide synthases (PKSs). The dehydration skeleton is reduced to yield precursors such as scytalone and Verme lone, which are then oxidized and polymerized to form DHN-melanin (Bell and Wheeler, 1986). Less common in Basidiomycota, some members of the orders Tremellales and Auriculariales within this group contain hybrid or partial DHN pathways (Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012; Upadhyay and Xu, 2018). Compared to Ascomycota, well-investigated DHN-melanin pathways, genetics, and enzymes (e.g., Fusarium graminearum and Aspergillus nidulans). Basidiomycota are highly reliant on the L-DOPA pathway; however, genomic data suggest that metabolic plasticity can be achieved, and a few basidiomycetes possess PKS-like genes involved in DHN-melanin biosynthesis, a case of convergent evolution and biochemical divergence (Gadd, 1982; Eisenman and Casadevall, 2012).

Cryptococcus neoformans pheomelanin is a fluorescent hydrophobic pigment granule derived from homogentisic acid (HGA) by HGA oxidation that increases fungal pathogenicity. The fungus also produces neuromelanin-like pigments in the brain using catecholamines, such as norepinephrine and dopamine, from the host and increases its pathogenicity.

With the exception of most of the Ascomycota, most of them produce DHN-melanin by the pentaketide pathway, but some basidiomycetous yeasts (e.g., Phaeococcomyces) also produce DHN-melanin, but very infrequently in Basidiomycota. The majority of the basidiomycetes are non-Ascomycota and utilize the hydroxynaphthalene pathway typical of Ascomycota. One of the most important distinctions between these phyla, therefore, is that Ascomycota biosynthesize predominantly DHN-melanin, while Basidiomycota biosynthesize predominantly tyrosinase-dependent eumelanin (GHB → eumelanin) or pheomelanin (HGA → pheomelanin). Biotransformation of two pigments, Cryptococcus neoformans, differs from other fungi in that it biotransforms host neurotransmitters into pyomelanin and neuromelanin-like pigments.

On the contrary, Basidiomycete fungal melanins are more resistant to degradation compared to the synthetic ones. Naturally produced fungal melanins are robust molecules that are less susceptible to photo-degradation, heat denaturation, and pH instability, and thus are superior natural food colorants and functional ingredients for food additives. Synthetic melanins are most commonly associated with unreproducible polymer molecular structures and low antioxidant activities, and thus are limited to food uses. Basidiomycete melanins, however, confer deep pigmentation and exhibit antioxidant, UV-screening, and possibly health-promoting activities, and can be marketed as renewable, multicomponent food additives (Lin and Xu, 2020; Nguyen et al., 2024).

Pigmented Basidiomycetes, being primarily mushroom genera, are also increasingly being revealed, besides filamentous fungi, for antioxidant activity. A comparative examination of six Pleurotus species revealed that pigmented species, such as the pink P. djamor and P. ostreatus, were more effective antioxidants than the white ones, and this was correlated with their phenolic content. Significantly, the high radical-scavenging activity of P. citrinopileatus at low phenolic content, suggesting a probable contribution from non-phenolic pigments or polysaccharides. These results confirm the commodity value of mushroom pigments as food bioactive, justifying their consideration for use in cultivation programs for the production of bioactive products (Mansuri et al., 2017).

2.5.2 Biotechnological and pathogenic significance of melanin

Melanin in C. neoformans enhances virulence by protecting against host immune responses. Mushroom tyrosinases (e.g., those from A. bisporus) are widely utilized in both commercial and research applications. It is important to clarify that other compounds studied in pigmented mushrooms, such as agaritine from A. bisporus, are not melanin intermediates. Agaritine is a phenylhydrazine derivative investigated for its potential antiviral effects, but it is also a known toxicant. Some mushroom melanin intermediates (e.g., agaritine) have been studied for potential antiviral (anti-HIV) effects, though they may also inhibit melanin formation. Beyond canonical melanin pathways, oyster mushrooms employ specialized chromoproteins for pigment stabilization. The P. salmoneostramineus pink chromoprotein (23.7 kDa) binds a 3H-indol-3-one prosthetic group and interacts with Mg2+—suggesting a novel metal-coordinated melanin assembly mechanism (Valdez-Solana et al., 2023). Its constitutive production enables consistent coloration regardless of cultivation lighting.

2.5.3 Melanin-mediated spore longevity in saprotrophic basidiomycetes

Melanin’s protective role is not confined to fruiting bodies but also involves spore resistance. Nguyen (2018) demonstrated that pigmented saprotrophic mushroom-forming fungal basidiospores remain viable for as long as 2.8 years—far longer than unpigmented spores. This is consistent with the UV-absorbing and antioxidant roles of melanin (Section 2.5.1) and reveals an ecological cost–benefit: melanized spores enable long-distance dispersal and delayed germination, while depigmented spores optimize rapid local colonization on good conditions.

At the biotechnological level, it is crucial for inoculum production and strain preservation. Pigmented fungi (such as melanized-spored Pycnoporus spp.) can offer intrinsic advantages to industries where culture stability is critical. On the other hand, light-spored fungi (such as Pleurotus albinus) require optimized storage protocols. These findings substantiate accounts of melanin’s radioprotective roles in Auricularia (Section 2.5.2) and suggest that spore pigmentation could serve as a predictor of stress tolerance upon screening pigment-forming strains.

2.6 Isoindole/non-nitrogen heterocyclic pigments (purple to pink)

Recent discoveries have expanded the diversity of Basidiomycete pigments beyond classical categories. Aragezolone from Auricularia cornea represents a structurally unique hybrid pigment with pH-responsive color shifts (purple→pink) for smart packaging, antidiabetic potential (anti-α-glucosidase activity 3 × > rutin), and light stability but heat sensitivity, suggesting cold-processing applications (Onuma et al., 2025). The flavonoid-like pigments in Auricularia spp. (e.g., biochanin A) exemplify how mushroom secondary metabolites blur traditional classification boundaries. While some studies attribute these compounds to fungal biosynthesis via modified PKS pathways (Pukalski and Latowski, 2022), others caution that environmental absorption may contribute to detected levels (Gil-Ramírez et al., 2016).

2.7 Phenolic pigments (brown to red)

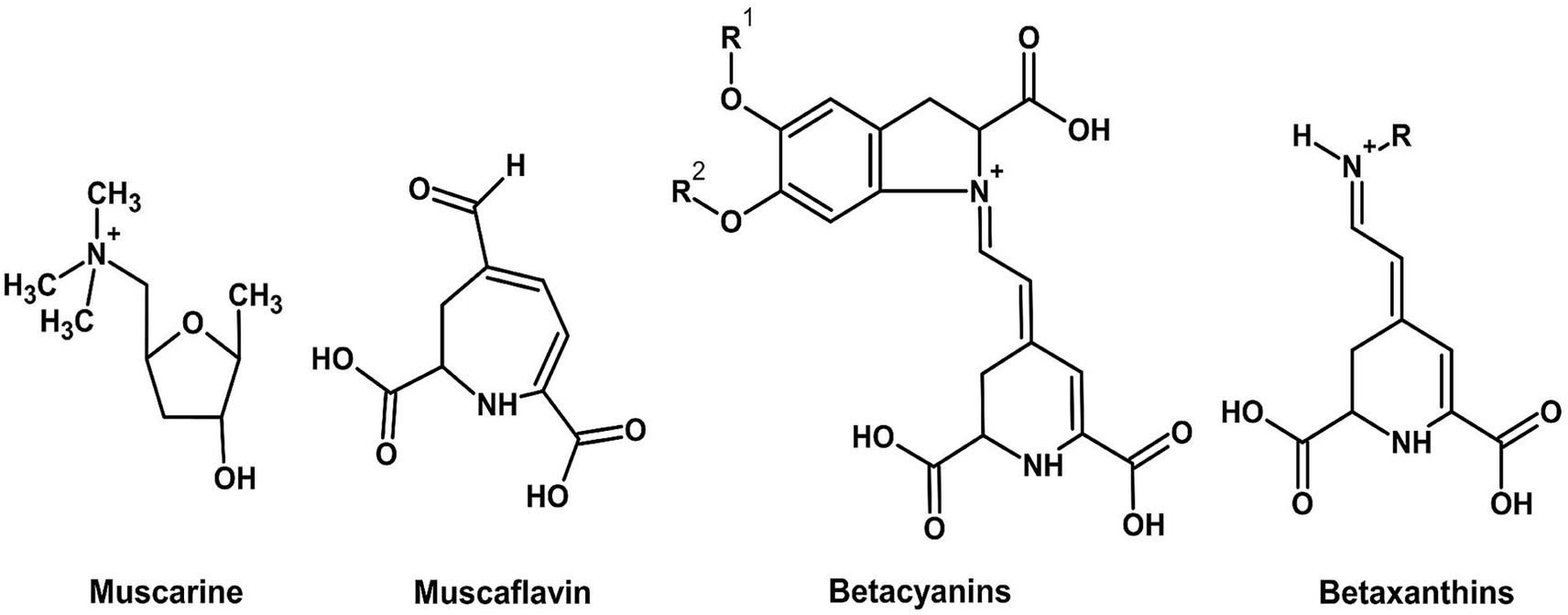

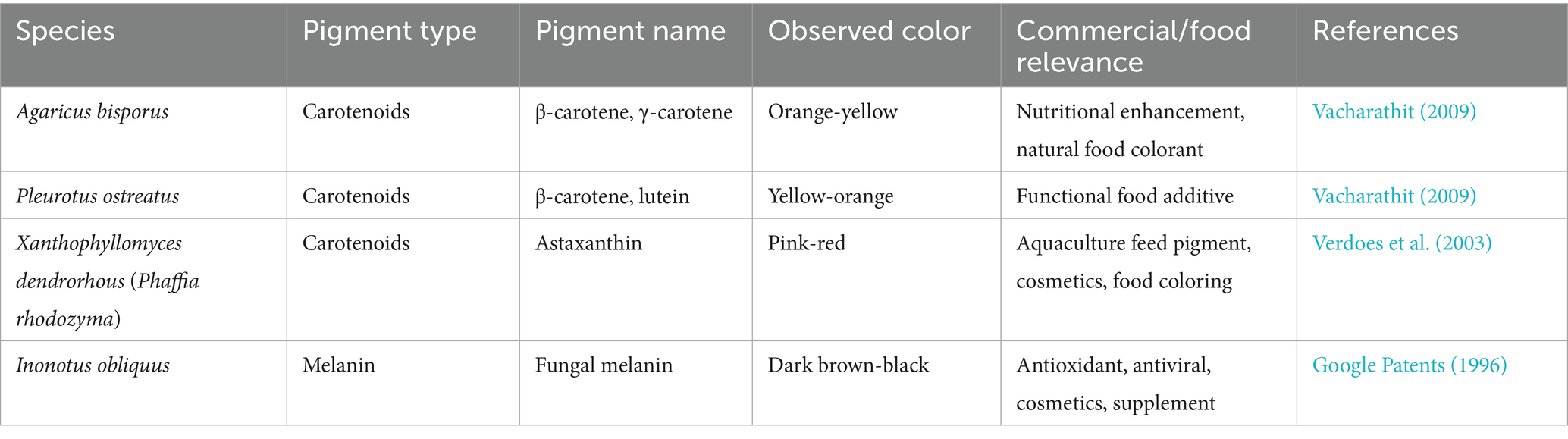

Lentinula edodes mycelium exudates represent a promising novel source of phenolic-based food color, which provides intense reddish-brown pigments and exceptional stability. A new scientific investigation by Jin (2010) thoroughly examined these exudates, verifying their composition (~5.82% dry weight phenolics) through highly advanced FTICR MS analysis and determining their improved thermal/light stability compared to that of artificial caramel coloring. Key, Jin’s toxicological assays with murine models established a no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) of 1,000 mg/kg/day for the pigments, indicating that they are safe for food application. Exudate stability—retaining color integrity during high-temperature treatment (e.g., baking, pasteurization)—addresses an important shortcoming of plant phenolics, such as antho-cyanins. Herein, it is also emphasized that production of L. edodes pigments through submerged fermentation is scalable, offering a viable pathway to industrial production. Regulatory clearance can be facilitated by the absence of detectable mycotoxins or allergenic proteins in purified fractions. The characteristic chemical structures of betalain and anthocyanin pigment classes are presented in Figures 8, 9, respectively. Table 1 compares the biosynthetic pathways, enzymatic machinery, and taxonomic distribution of major natural pigment classes, highlighting both the unique capabilities of Basidiomycetes and convergent evolution with microfungal producers.

Table 1. Biosynthetic origins, key enzymes, and representative fungal taxa involved in the production of major natural pigment types, comparing pigment-producing basidiomycetes with microfungal analogs.

3 Applications of basidiomycete pigments

Basidiomycete fungi are a valuable yet underexploited source of natural pigments with high potential for use in the food and aquaculture industries. Pigments, including carotenoids, melanins, pulvinic acid derivatives, and phenolic compounds, exhibit both strong coloration and bio functional activity, such as antioxidant and antimicrobial activity. Unlike synthetic dyes, which are also facing regulatory and consumer resistance, Basidiomycete pigments can be produced on a sustainable large scale through fermentation and exhibit higher stability under process conditions (Mattoon et al., 2021; Zschätzsch et al., 2022).

3.1 Pigments for hue replacement

In foods, mushroom pigments are increasingly sought after as natural colorants, being clean-label and sustainability-friendly. Laetiporus sulphureus, for example, a yellow-orange polypore, provides pulvinic acid-type pigments that are thermally and acidically stable to a very high extent, making them a possible application in flavored beverages, breads, and fermented foods (Bergmann et al., 2022). In addition, Pycnoporus cinnabarinus yields phenoxazinone and cinnabarinic acid pigments from synthesis that exhibit high oxidative and light stability in preliminary food-model systems and offer good alternatives for man-made dyes like Red 40 or Yellow 5 (Gawel, 2024). Basidiomycete pigments are particularly favored as they are more process-stable than their plant counterparts. Unlike the breakdown of anthocyanins from fruits or betalains from beets under alkaline or neutral pH or high temperature, most fungal pigments are not lost in color upon extrusion, pasteurization, or long-term storage (Gawel, 2024). Such stability is desirable in applications in plant-based meat, dairy alternatives, or convenience foods. Regulatory acceptance for hue replacement is also incrementally widening. In Asia, Japan and South Korea have accepted certain pigments of Schizophyllum commune and T. versicolor in food additive safety frameworks. In the EU, the EFSA is currently reviewing other fungal metabolites for placement in its list of approved colors, i.e., those with low toxicity and well-documented thermal stability (European Food Safety Authority, 2021). This regulatory drive will open up new markets in functional foods, especially in the EU and North America.

3.2 Multifunctional additives

Conversely, melanins from food-grade Basidiomycetes, such as A. auricula-judae or L. edodes, contribute a deep brown to black color and high antioxidant activity, making them suitable for application in functional food coatings, protein bars, and beverage powders (Yin et al., 2022). From the marketing and industry perspective, natural food colors across the globe are likely to reach USD 3.5 billion in 2027, and mushroom pigments are going to hold higher market share because they can act as both color additives and health supplements (Market Data Forecast, 2024). Compatibility with veganism, free-from allergens, and clean-label tag enhances brand reputation, specifically among millennials and Gen Z consumers. Startups and ingredients firms are now looking at branded Basidiomycete pigment extracts, e.g., “MycoHue™” or “FungiTint™,” to develop identity-driven products that offer consumers sustainable sourcing and biotechnology narratives. In addition, fungal fermentation dyes from, e.g., Hericium erinaceus, Marasmius spp., and P. ostreatus enable round-the-year harvests with no seasonality or enormous land and water requirements as with botanical dye plants (Zschätzsch et al., 2022).

3.3 Aquaculture feed applications

In aquaculture, fungal pigments, in particular carotenoids, are gaining regulatory and market acceptance as clean-label color intensity enhancers. Astaxanthin, the pigmentation compound for salmonids, is traditionally synthesized from petrochemical precursors or obtained from Haematococcus pluvialis. Fungal sources, such as X. dendrorhous, offer a 40–60% cost reduction for fermentation-based production compared to artificial approaches (Zantioti et al., 2025). Astaxanthin from X. dendrorhous has been accepted by EFSA for salmon and trout diets (European Food Safety Authority, 2021), while Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and Sporidiobolus pararoseus are found to be beneficial to tilapia, shrimp, and aquatic ornamental fish. The fungi improve the flesh color and oxidative resistance of fish as well as immune responses (Chen et al., 2019; Van Doan et al., 2023). Industry-wise, the aquaculture pigment market exceeds USD 1 billion annually, with more than 75% of the market allocated to salmonids. With increasing consumer resistance to artificial colorants, natural fungal pigments are now being promoted as “clean seafood colorants,” which also provide value through immunomodulation. Furthermore, the positioning can also be utilized by manufacturers to market products as “naturally pigmented,” and this has already been shown to influence consumers’ purchase behavior in North America and Europe (Zantioti et al., 2025). Scale-up is nevertheless limited by fermentation bottlenecks, particularly in optimizing production of lipid-soluble carotenoids. Bioreactor-based solutions using agro-waste substrates and metabolic engineering are being investigated to address this limitation (Li et al., 2022).

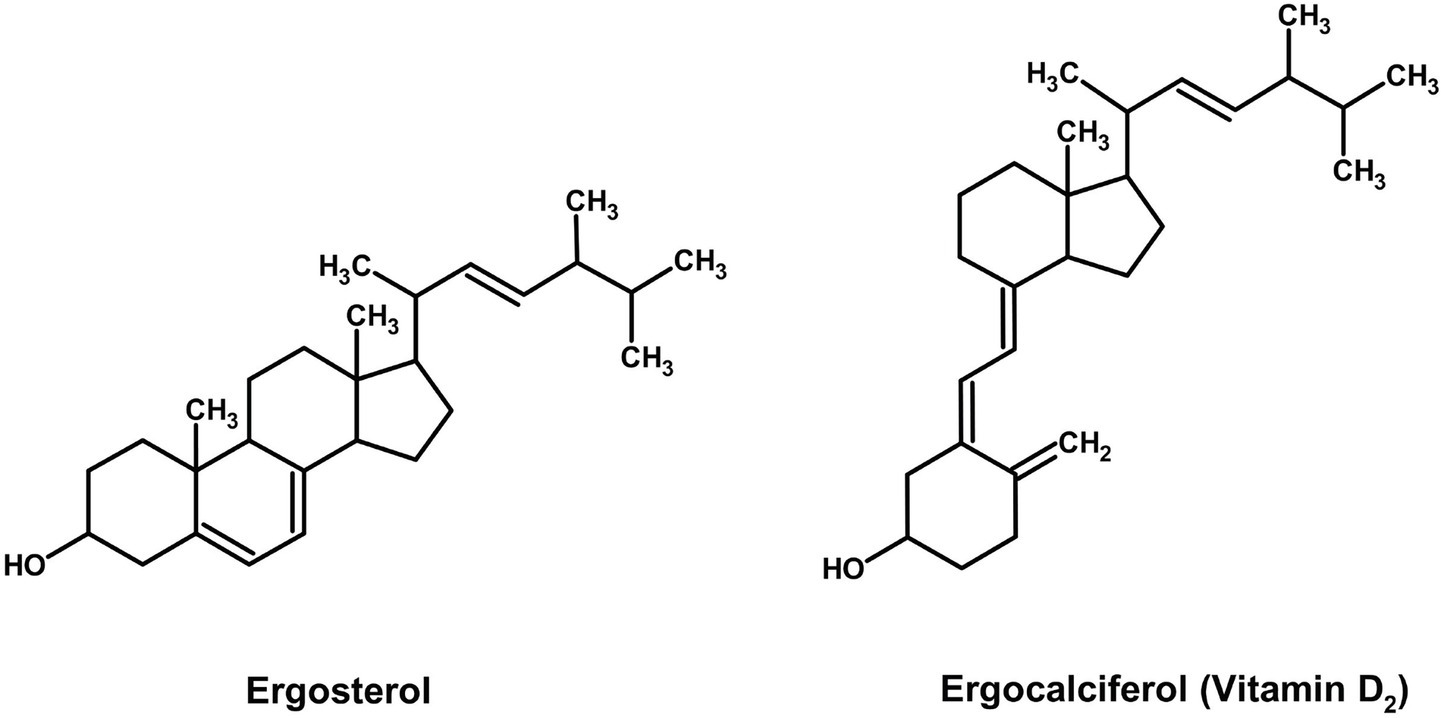

3.4 Vitamin D₂ biofortification as a value-added co-product

The value of pigmented Basidiomycetes extends beyond their chromatic properties to include significant nutraceutical potential. A prime example is ergocalciferol (Vitamin D₂), a secosterol synthesized from the fungal membrane sterol ergosterol upon exposure to UV light. While distinct from pigment pathways, the ability to enhance Vitamin D₂ content through post-harvest UV treatment adds a compelling functional food dimension to mushroom-based colorants. For instance, while Cantharellus cibarius is primarily studied for its carotenoid pigments, its fruiting bodies also contain ergocalciferol (Vitamin D₂), which is formed from the photo-conversion of ergosterol upon UV irradiation (Figure 10).

Rangel-Castro et al. (2002) demonstrated that dried chanterelles retain substantial Vitamin D₂ levels (0.12–6.30 μg g−1 DW; mean 1.43 μg g−1 DW) with great stability even after 2–6 years of storage. The wide variation in concentration—attributable to differential sunlight exposure and not pigmentation (no difference was observed between pigmented and albino strains), highlights the limitations of pooled-sample food tables. Mechanistically, UV-B irradiation is particularly effective at breaking the B-ring of ergosterol to form pre-Vitamin D₂, thereby enhancing the photo-conversion efficiency. This supports the recommendation of controlled UV irradiation during processing to normalize and boost yield. These findings are consistent with research on A. bisporus, where post-harvest UV treatment significantly increases Vitamin D₂ content (Koyyalamudi et al., 2009), positioning C. cibarius as a species of dual functional relevance for pigment and nutraceutical production via mycelial fermentation. Like carotenoids, UV-inducible vitamin D₂ (ergocalciferol) in Cantharellus cibarius, albeit its biosynthesis is from ergosterol precursors, not terpenoid metabolism (Rangel-Castro et al., 2002; Cardwell et al., 2018). Such dual UV responsiveness renders pigmented mushrooms both a nutraceutical and a colorant source.

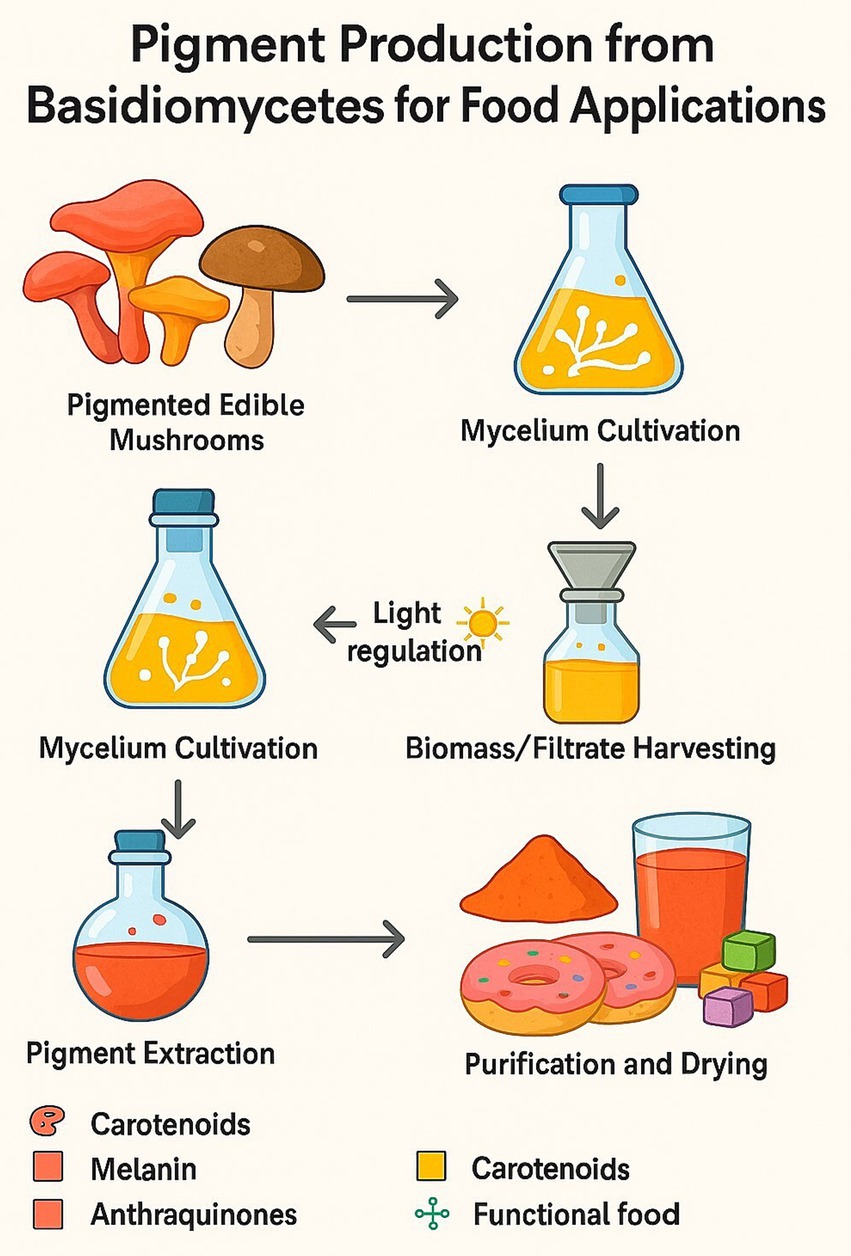

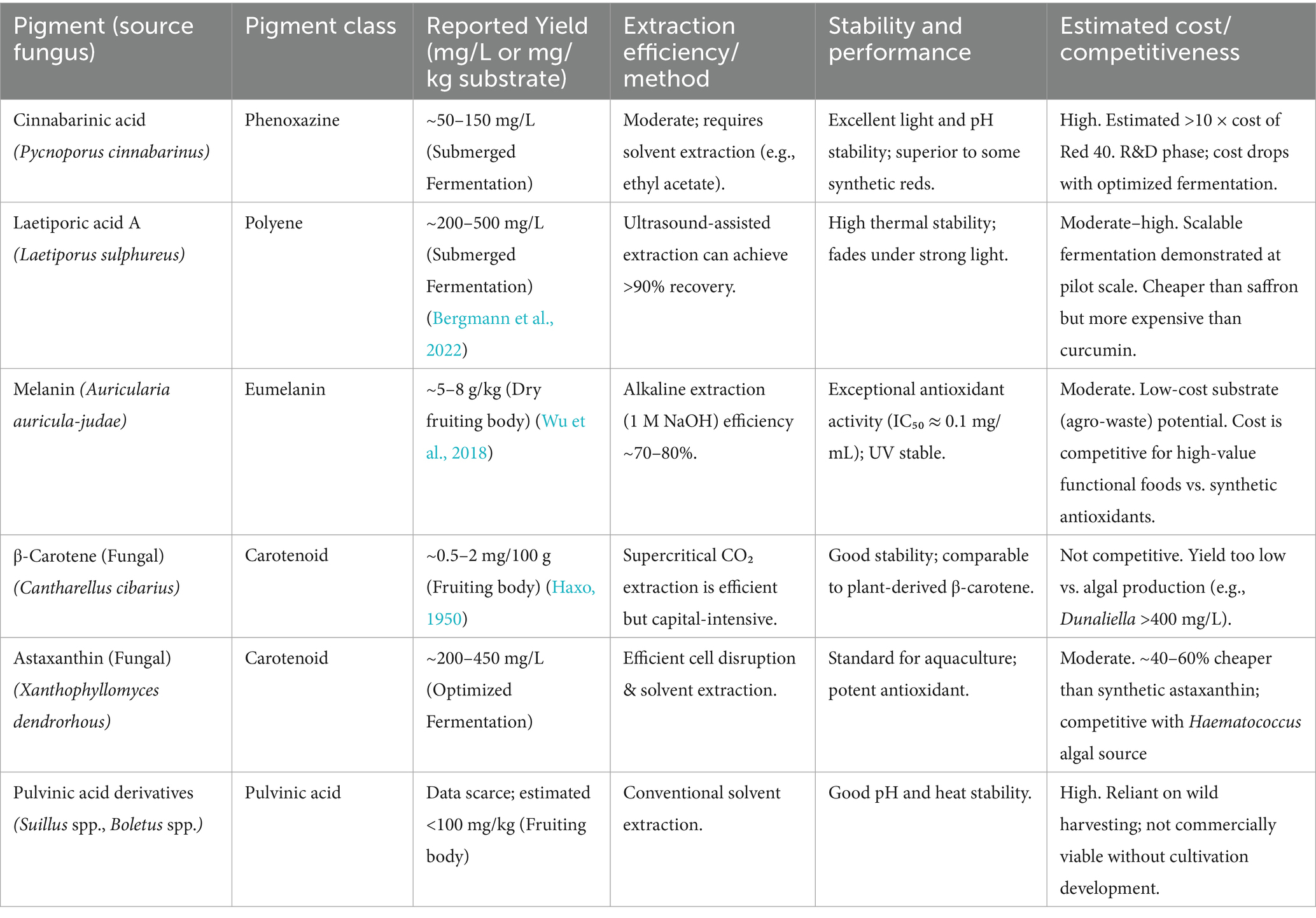

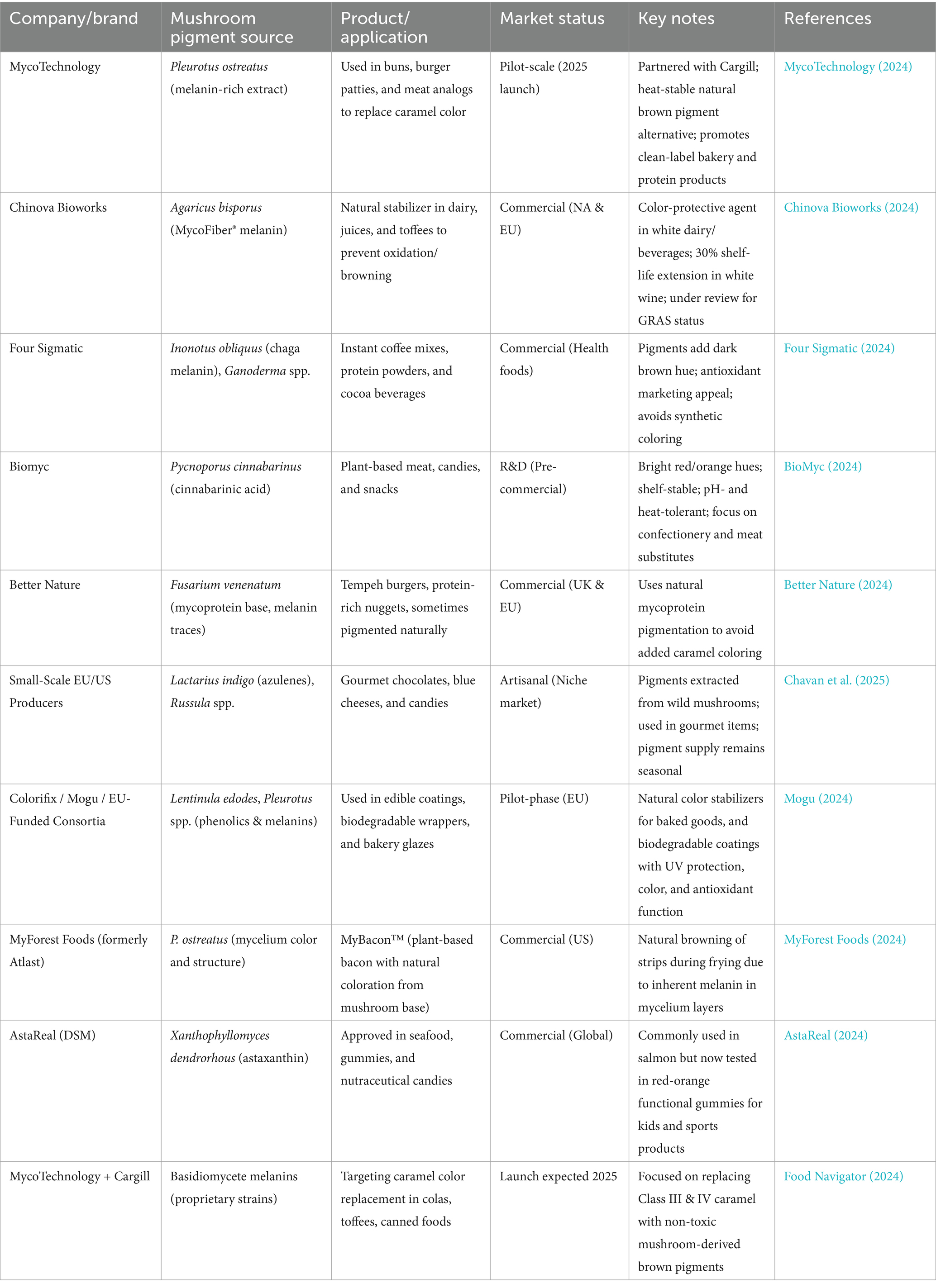

Table 2 summarizes the taxonomic distribution of pigment-forming Basidiomycetes with dominant species, their pigment color and type, and known or possible uses in food and commercial products. Figure 11 illustrates the role of Basidiomycetes as a source of natural food pigments. Table 3 summarizes current commercial and emerging mushroom-derived pigments and stabilizers for food applications, highlighting their sources, industrial uses, and market readiness to demonstrate the growing viability of Basidiomycete-based solutions in the food industry.

Table 3. Commercial and emerging mushroom-derived food colorants and stabilizers for food applications.

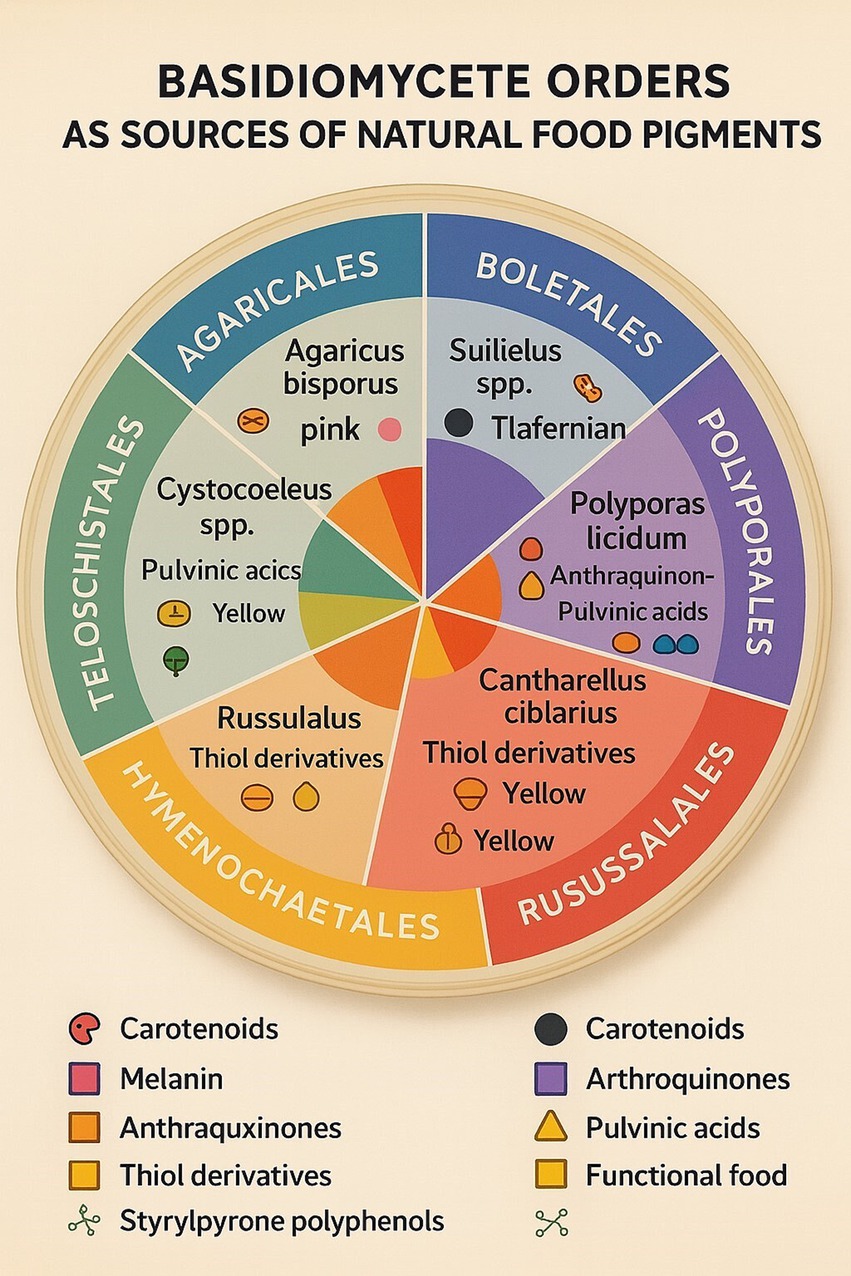

4 Extraction and production strategies

Green and sustainable extraction methods are critical to the economic feasibility of Basidiomycete pigments and adhere to green chemistry principles. The general process for producing these pigments, from cultivation to a finished, usable product, is outlined in Figure 12.

Solvent-free, energy-efficient processing with low environmental impact compared to traditional solvent-based processes typically utilized in synthetic dyes is characteristic of such processing methods as supercritical CO₂ extraction. Supercritical CO₂ not only avoids the chemical waste of traditional extraction, but preserves pigment integrity, particularly for thermal- and oxygen-sensitive carotenoids from taxa such as C. cibarius (Tauber et al., 2018). Traditional extraction approaches for fungal pigments vary by compound class and fungal species. Alkaline extraction is widely used for melanins from Pleurotus species due to the pigment’s insolubility and complex polymeric nature. For more labile pigments such as phenoxazinones and pulvinic acids, ultrasound-assisted and microwave-assisted extraction techniques enable rapid recovery at lower temperatures, minimizing thermal degradation (Kim, 2020). Emerging in situ methods, such as Raman spectroscopy, provide non-destructive, real-time monitoring of pigment synthesis and accumulation during fermentation or cultivation, as demonstrated for polyenes like laetiporic acid and pulvinic acids in Laetiporus and Boletus species (Tauber et al., 2018). This real-time quality control helps optimize harvest timing and extraction efficiency, thereby reducing waste.

The application of controlled oxidative stress, such as hydrogen peroxide treatment, has been shown to significantly enhance pigment production. This treatment often activates stress-response transcription factors (e.g., AP-1, Yap1) that bind to antioxidant response elements (AREs) in the promoters of genes involved in pigment biosynthesis. For instance, pigment yields in Shiraia bambusicola increased by 27% following exposure to H₂O₂ (Deng et al., 2016). Such stress-induced upregulation is a promising avenue for boosting the yields of Basidiomycete pigments, such as laetiporic acid or cinnabarinic acid, from Pycnoporus and Boletus. Temperature also plays a key regulatory role; melanization in Pleurotus species is temperature-sensitive, allowing tunable pigment profiles through controlled cultivation parameters (Kim, 2020). Similar to Monascus purpureus, where yellow pigment production increases above 45 °C and red pigment biosynthesis is stimulated by NaCl addition, Basidiomycetes show potential for targeted pigment modulation by environmental cues. Cultivation techniques for pigment production include solid-state fermentation using agro-industrial wastes, such as corncobs and banana peels, which offer low-cost and sustainable substrates that also contribute to waste valorization. Submerged fermentation is preferred for standardized and scalable pigment yields, and can be optimized by strain selection, mutation breeding, or metabolic engineering to enhance pigment biosynthesis pathways (Lin and Xu, 2023). Environmental stresses proven to induce pigment production in Ascomycetes, including nitrogen starvation and oxidative stress, also increase Basidiomycete pigment production. Nitrogen starvation, for example, triggers a global stress response that can derepress secondary metabolite pathways, diverting carbon flux toward the synthesis of pigments like cinnabarinic acid in P. cinnabarinus (Temp and Eggert, 1999). In contrast to the production of synthetic dyes, which often requires hazardous solvents, high energy inputs, and toxic waste, these biotechnological methods offer cleaner, more environmentally friendly alternatives. Integration of green extraction methods with fermentation processes powered by renewable feedstocks positions Basidiomycete pigments as environmentally responsible solutions for the natural colorant market.

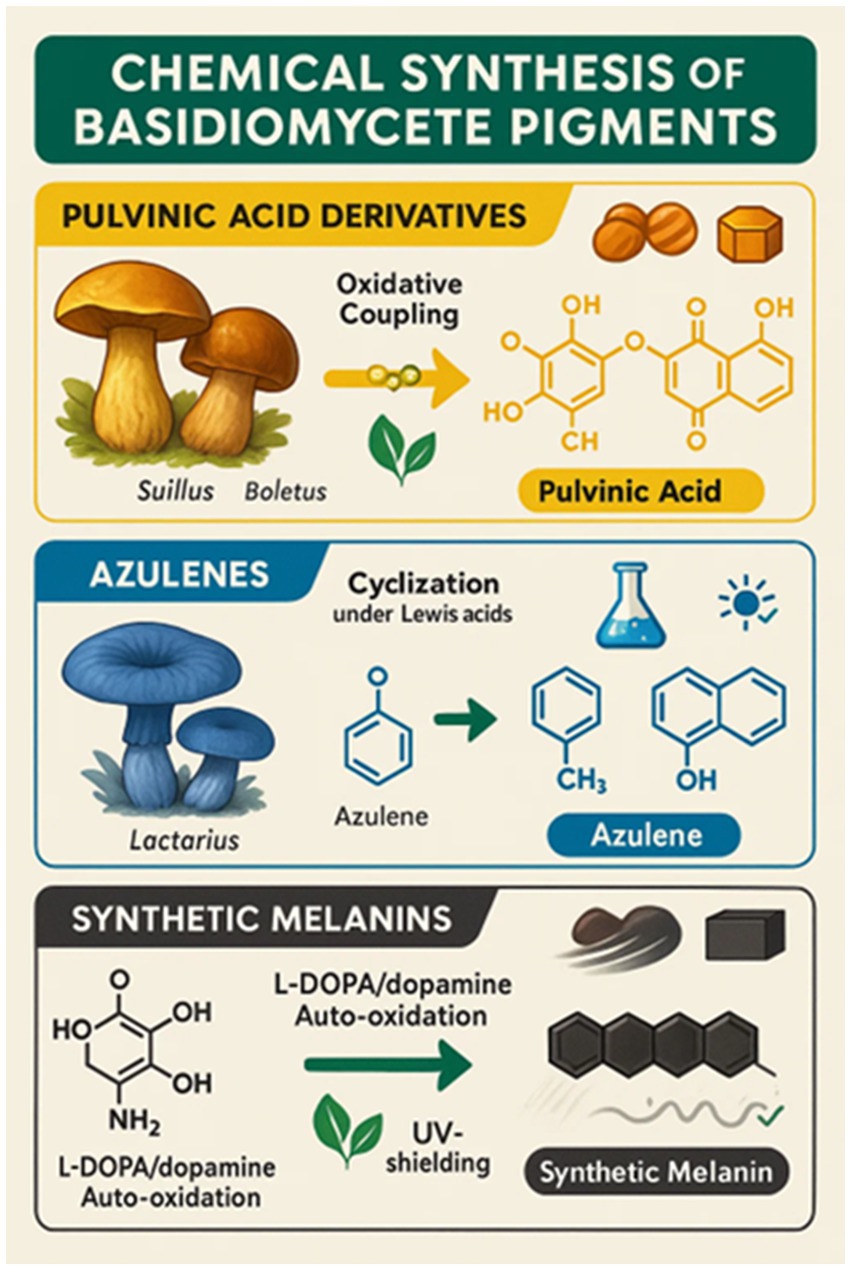

5 Synthetic and semi-synthetic approaches

Basidiomycete fungal pigment chemical manufacture is a new multidisciplinary research discipline at the intersection of mycology, organic chemistry, and food science. Natural harvesting from mushroom fruiting structures has been the primary source to date of melanins, carotenoids, and pulvinic acid derivative pigments. This is plagued with inherent limitations of yield, seasonality, and scale-up, nevertheless. Thus, chemical synthesis and semi-synthetic modification of fungal pigments are being researched as viable means to enable standardized, cost-effective, and scalable manufacture suitable for food industry requirements. The rationale of chemical synthesis is to avoid the shortcomings of natural extraction typically plagued by low concentration of the pigment, heterogeneous mixtures, and reliance on agricultural conditions. Chemical pathways yield pure pigments with reproducible properties, allowing for structural modification for enhanced pigment stability, solubility, and color tunability. Moreover, semi-synthetic approaches, naturally occurring fungal precursors chemically converted, provide middle-ground solutions for maximizing pigment characteristics without de novo synthesis.

An example is the synthesis of pulvinic acid-type yellow pigments, which were first isolated from organisms such as Suillus and Boletus species. They are aromatic acids of polyphenolic character with bright yellow-orange color, of great interest as food pigments. Synthetic pathways typically involve oxidative coupling reactions of catechol-type precursors under mild oxidizing conditions, allowing for fine-tuning of the pigment’s color and stability. Atromentin, a key pulvinic acid precursor, was first synthesized by Steglich et al. (1972) via oxidative dimerization of substituted phloroglucinols, establishing the foundation for methods that are still applied in modified form today.

Another class of interest is azulenes, which are aromatic non-benzenoid hydrocarbons containing fused ring systems valued for their unique blue color. These pigments are rare among Basidiomycetes, with Lactarius indigo being a particularly prominent natural source. Chemical synthesis of azulenes typically involves the cyclization of substituted cyclopentadiene derivatives with electrophilic aromatic partners, usually under Lewis acid catalysis, to yield these deep blue molecules. While fungal biosynthesis occurs via unique, largely uncharacterized enzymatic pathways, synthetic analogs have been developed that mimic the core structural motifs of fungal azulenes rather than their true biosynthetic routes. These synthetic analogs show promising antioxidant activity and thermal stability, as reported by Wang L, et al. (2021), making them candidates for food-grade colorants.

Melanin pigments, which are polymeric and heterogeneous in nature, have also been synthetically mimicked through the auto-oxidation of L-DOPA or dopamine under alkaline, aerobic conditions. The primary chemical synthesis routes for recreating major Basidiomycete pigment classes, including pulvinic acid derivatives, azulenes, and synthetic melanins, are summarized in Figure 13.

These synthetic melanins reproduce key physicochemical properties of natural fungal melanins, such as UV protection and radical scavenging, and have therefore been of interest for use in food packaging and edible coating systems. Their deep dark color, along with low solubility, however, has deterred their direct utilization as food colorants. Still, synthetic melanins offer valuable models for studying structure–function relationships and for developing functional materials (Aman Mohammadi et al., 2022).

Despite progress, regulatory clearance of synthetic or semi-synthetic fungal pigment analogs for food applications remains a major hurdle. Compounds must demonstrate non-toxicity, biodegradability, and stability under various food processing conditions to meet safety standards established by agencies such as the FDA and EFSA. Therefore, modern synthetic routes increasingly adopt principles of green chemistry—minimizing the use of toxic solvents, energy, and aggressive reagents—in alignment with sustainability goals.

While the majority of chemical synthesis work is at the pilot or laboratory scale, it represents a critical foundation. Growing consumer demand for natural, consistent food colorants, combined with the inherent limitations of extraction-based supply chains, positions synthetic and semi-synthetic approaches as a promising frontier for the scalable production of Basidiomycete pigments. Further elucidation of fungal biosynthetic gene clusters and metabolite pathways provides insight into stable intermediates and functional motifs that can be tapped or mimicked synthetically, thereby bridging the gap between biology and chemistry in the synthesis of new pigments (Aman Mohammadi et al., 2022).

6 Legislation of basidiomycete bio-pigments

As with any food additive, biopigments derived from Basidiomycete fungi will also undergo rigorous regulatory testing prior to acceptance for use in foods. These natural pigments of fungi, i.e., pulvinic acid derivatives, melanins, and mushroom betalain-like pigments such as in Suillus, Cortinarius, and Inonotus, will be examined thoroughly for toxicity, allergenicity, purity, and stability (Poorniammal et al., 2021; Dufossé, 2024). Of greatest relevance to safety assurance is the establishment of extraction and purification methods that effectively eliminate undesirable or potentially toxic fungal metabolites, such as mycotoxins and immunogenic compounds (Kaur and Anand, 2025).

Globally, the regulatory framework for natural colorants is evolving in response to rising consumer demands and technological advances. In the United States, the FDA has historically approved mainly synthetic color additives, such as FD&C Red No. 40 and Yellow No. 5, as well as a few mineral-based color additives, including titanium dioxide (E171) and iron oxides (E172). Still, growing consumer demand for naturally and microbiologically sourced colorants has led to the recent approval and consideration of plant- and microbe-source colorants, such as gardenia blue and butterfly pea flower extract, approved in 2025, as a move toward naturally sourced products gets underway (European Food Safety Authority, 2025; FDA, 2025). In the European Union, food additives, such as colorants, are regulated by Regulation (EC) No. 1333/2008. There are 43 approved colorants permitted for use in foods, and they are predominantly of synthetic or vegetable origin (Nigam and Luke, 2016). Basidiomycete pigments have not yet been sold on an industrial basis as food colorants, but certain compounds, such as mushroom-derived melanins and pulvinic acid analogs, are being actively considered for Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) approval or novel food authorization. Their dual mode of action as both pigments and antioxidants optimize their use in the development of clean-label and functional food industries (Poorniammal et al., 2021; Chatterjee and Pandey, 2023). Commercialization is currently being hindered primarily by regulatory constraints, scale-up challenges, and gaps in safety data, but is offset by growing research and development efforts.

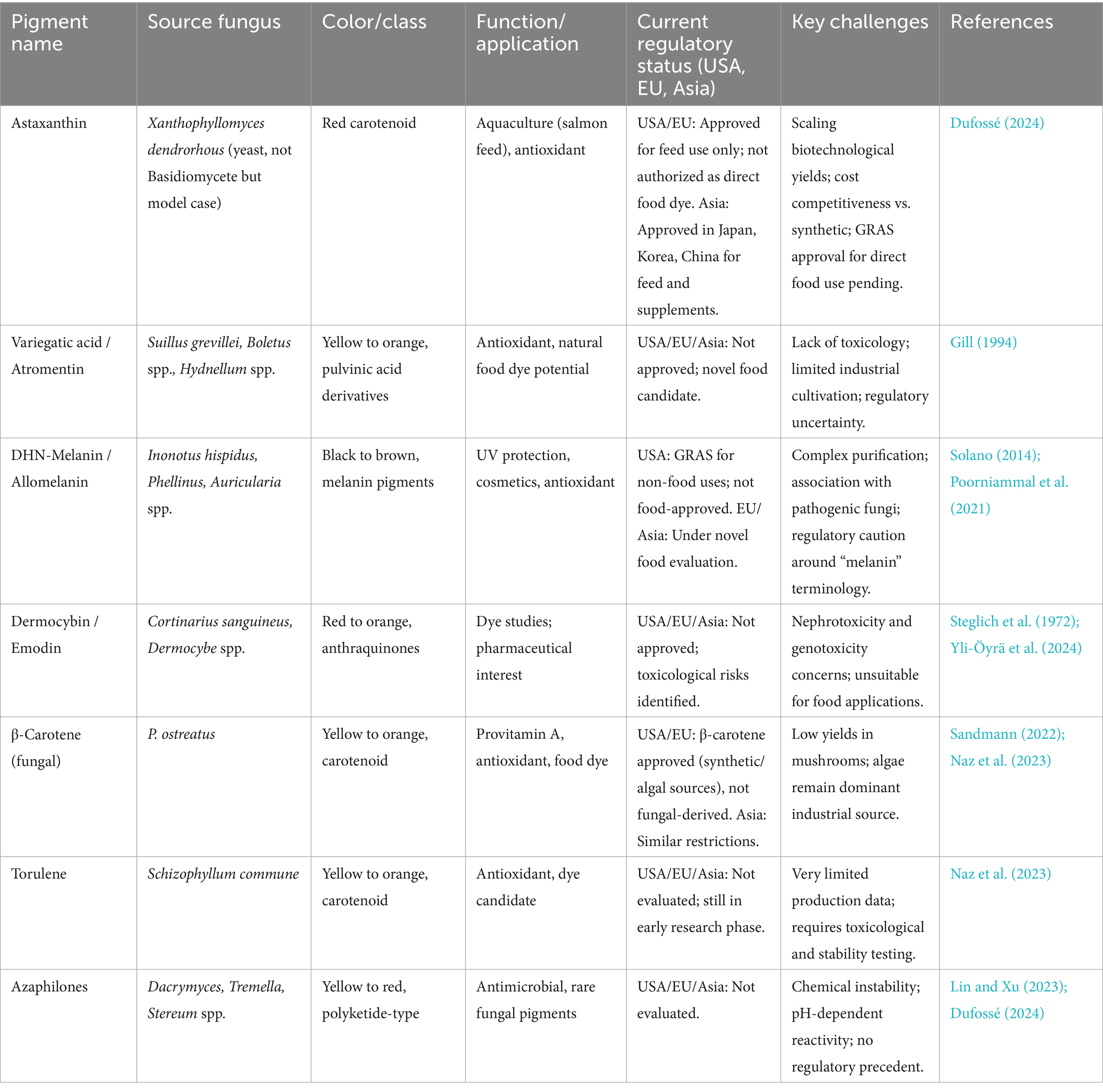

It is given the utmost priority to safety testing. Fungal pigments must be tested strictly for mycotoxin content, including citrinin—a non-specific Monascus species product—and possible allergenicity, according to Poorniammal et al. (2021). Pigments of Talaromyces purpureogenus, for instance, were non-toxic to rodent models of toxicity, while Fusarium species naphthoquinone pigments are of safety concern due to being co-produced alongside toxic metabolites. Basidiomycetes, such as Pleurotus and Pycnoporus, have been reported to possess acceptable safety profiles; however, toxicity testing, including subacute oral toxicity testing and Artemia salina lethality testing, should be standardized to determine their safety for food applications. Regulation acceptance will be a follow-up later based on these data gaps, as with the evolution of the Ascomycete pigment industry (Table 4).

Table 4. Regulatory status and industrial potential of basidiomycete-derived pigments across major regions.

7 Industrial potential and challenges

Basidiomycete pigments yield excellent industrial benefits due to their natural origin, aligning with the trend of increasing consumer demand for clean-label, vegan, and multifunctional products. They also have nutrition or bioactive properties in most instances, which further make them highly desirable to be utilized in food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical applications. Secondly, the integration of pigment extraction with established mushroom processing infrastructure offers the potential for both the economic viability and environmental sustainability of mushroom-based biorefineries to be enhanced. Despite these promising conditions, commercialization of Basidiomycete pigments is plagued by a comparatively high number of outstanding issues of critical importance (Table 5).

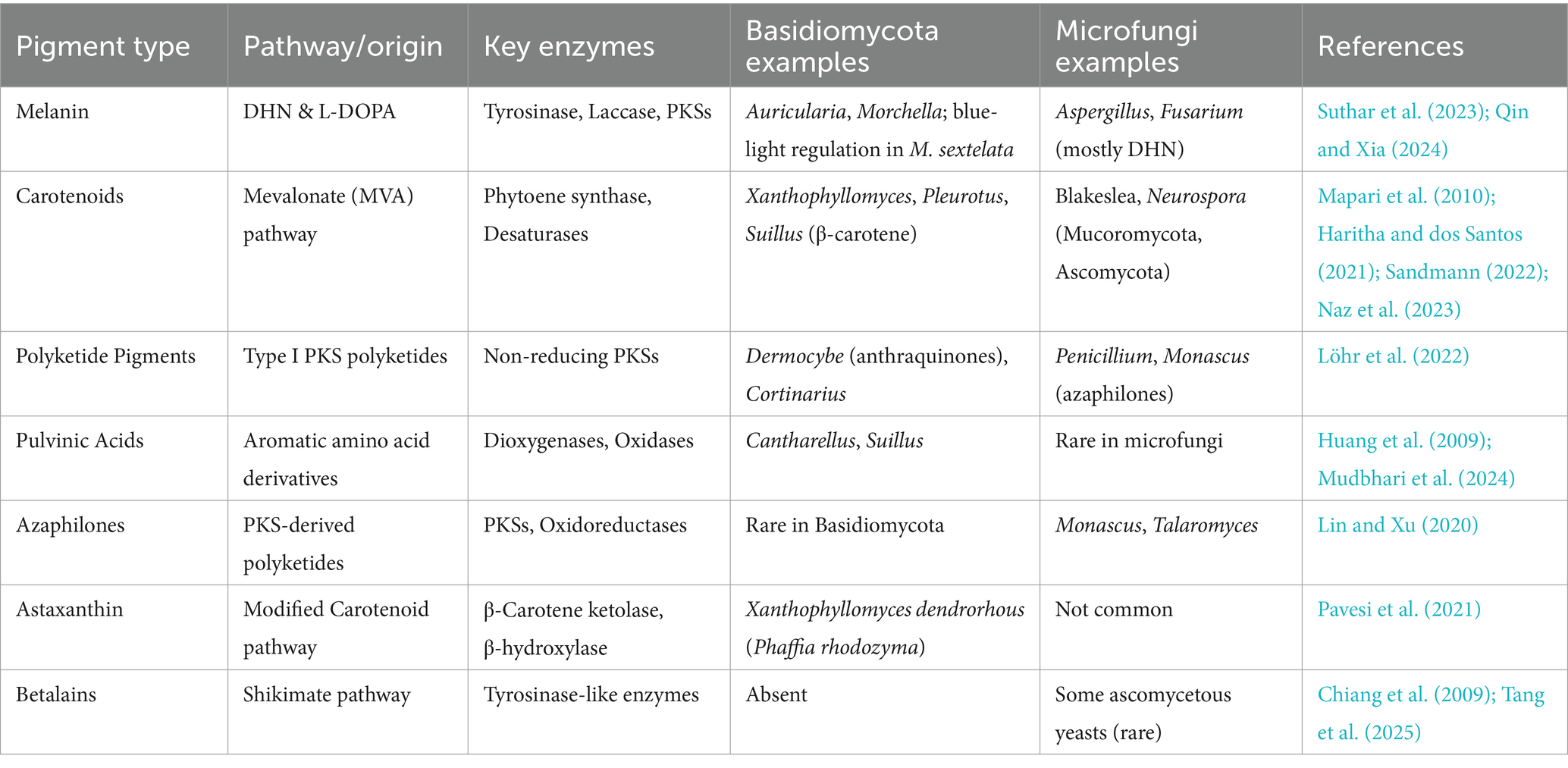

Among the most notable issue is the lack of Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status for the majority of pigments from wild Basidiomycete strains. The local strain yield is usually low and can vary broadly with respect to the genetic background of the strain and culture conditions. The unreliability of yield complicates large-scale production, as well as the reproduction of quality. A critical assessment of these production challenges is provided by the quantitative data on yields and costs for representative pigments (Table 6). The data highlight a stark contrast; while fermented pigments like laetiporic acid and fungal astaxanthin achieve promising titers, others reliant on wild harvests or simple cultivation (e.g., Cantharellus β-carotene) exhibit yields that are commercially non-viable, directly impacting their economic competitiveness.

Moreover, fungal pigments are not yet broadly accepted for commercial use, and only some major genera, such as Pleurotus and Cantharellus, have demonstrated market potential.

Safety is always the first consideration. Basidiomycete pigments, like all fungal pigments, need to be rigorously screened for toxic metabolites. A case in point is the nephrotoxin citrinin, found in Monascus species, that can act as an example. Gyromitra species contain a toxin gyromitrin, which is why it is required to maintain the pigment safety under control before commercial use. Gene engineering methodologies, such as CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing, offer an encouraging answer to such safety concerns by enabling the targeted deletion of biosynthetic gene clusters for toxin production. Species-specific toxicological testing must be performed, as exemplified by the European Union’s ban on hydroquinone due to safety concerns despite having occurred naturally for centuries. This indicates that safety measures can trump natural status when regulation is in place.

To counteract these issues, some solutions are currently being developed. Genetically modified organisms and adaptive laboratory evolution strategies can be utilized to boost the quantity and range of pigments with improved safety profiles. Mimicking nature’s ecological processes through the co-cultivation of fungi has the potential to increase pigment complexity as well as pigment yield efficiency. Marketing the fungal pigments as “fermented fungal colorants” would also increase consumer acceptance by putting the products in an acceptable and familiar category. The introduction of novel analysis methods, e.g., Raman spectroscopy, promises real-time and non-destructive analysis of pigment biosynthesis during the process of fermentation or co-cultivation, thus accelerating process optimization and strain selection.

Basidiomycete melanins, in particular those from Auricularia species, are shown to possess the same functional activities as human-pathogenic fungi, e.g., Wangiella dermatitidis, such as radioprotection and metal chelation. These above-mentioned characteristics create new functional food possibilities for humans with high exposure to radiation, e.g., astronauts. The application of Auricularia auricula extracts in traditional Chinese medicine to protect against the effects of radiation also attests to their functional viability.

Economically, the global carotenoid industry, currently valued at approximately $1.5 billion and dominated by firms such as DSM, can have its scope of activity broadened to Basidiomycete-derived carotenoids if economically viable methods of obtaining compounds such as β-carotene from the Cantharellus mushroom are realized. Melanin-producing mushrooms will also be on hand for niche use in radioprotection for occupational defense, space exploration, and medical radiology.

This future work would include the establishment of dose–response relationships for regulatory approvals, e.g., GRAS status, the impact of food processing on pigment bioactivity, and the characterization of synergistic action with other fungal antioxidants, e.g., ergothioneine in L. edodes. While toxin contamination is still a major regulatory hurdle, illustrated by the case of Monascus citrinin, CRISPR—Cas9—mediated elimination of the toxin biosynthetic pathway, demonstrated to work for Ascomycetes, holds promise for Basidiomycete pigment producers. Several companies, including start-ups such as Microtechnology, are leading the charge in overcoming these hurdles using innovative fermentation technologies, genetic engineering, and bioprocess optimization to yield commercially important fungal pigments. Despite decades of struggle to optimize yields and regulatory challenges, the prospects of Basidiomycete pigments for industrial applications are being revolutionized by advances in biotechnology and analytical methods.

The commercialization of Basidiomycete pigments is propelled by powerful market trends but is simultaneously constrained by a complex regulatory landscape. On the market front, unprecedented consumer demand for clean-label, natural, and vegan products is driving the food industry away from synthetic dyes like tartrazine and Red 40 (Savastano, 2025). This shift is complemented by the positive perception of fermentation as a natural process, allowing fungal pigments to be marketed as sustainable and innovative (Gomes, 2024). The global natural food colorant market, projected to exceed USD 3.5 billion, represents a significant opportunity (ECHEMI, 2025). Potential applications are diverse, spanning stable colorants for plant-based meats, functional ingredients in nutraceuticals leveraging their inherent bioactivity, and cost-effective alternatives in aquaculture feed, as demonstrated by the success of fungal astaxanthin (Gomes, 2024). However, this promising market potential is tempered by formidable regulatory hurdles. Critically, no Basidiomycete pigment extract currently holds Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) status in the US or full novel food authorization in the European Union (Elkhateeb and Daba, 2023). The regulatory path requires extensive and costly toxicological studies including subchronic toxicity and allergenicity assessments, to establish safety. A paramount concern for regulators is the rigorous exclusion of potential co-extracted toxins, such as mycotoxins, from the fungal material (Elkhateeb and Daba, 2023). Furthermore, achieving the batch-to-batch consistency and standardized composition demanded by regulatory agencies for approval remains a significant technical challenge for complex biological extracts. This divergence between robust market pulls and stringent regulatory push defines the current industrial paradigm for Basidiomycete pigments. Navigating this landscape will require the continued integration of biotechnology, robust safety science, and strategic market positioning to fully realize their commercial potential.

8 Conclusion

Basidiomycete pigments are in the dynamic area of natural, clean-label food color with bright colors and inherent natural bioactivity and fermentative scalability. As detailed throughout this review, their potential is significant, yet commercialization faces distinct challenges, as summarized in Table 7.

However, to unleash the promise into commercial reality, an integrated and focused approach is crucial. Future progress will be driven by potent genetic tools, such as CRISPR-Cas9, for strain improvement, innovative fermentation technologies derived from Ascomycete systems to optimize yield, and nanoencapsulation technologies for enhancing food stability. Concurrently, a concerted effort must be made to obtain good safety data and navigate the regulatory pathways in order to reach the market. Some of the promising candidates such as the red pigments of Pycnoporus and functional melanins of Auricularia are already making a mark. Finally, the full utilization of these versatile fungal pigments will depend on ongoing cross-disciplinary studies among mycologists, food chemists, and biotechnologists to overcome the final limitations of scale, stability, and application, ultimately leading to a brighter and healthier future for food dyes.

Author contributions

SK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ST: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. WL: Formal analysis, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. HP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ET: Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. BK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. D-qD: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. JK: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. CK: Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – review & editing. KH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. NS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number 32260004).

Acknowledgments

SK and ST thank the Yunnan Provincial Department of Science and Technology “Zhihui Yunnan” plan (202403 AM140023), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number 32260004), the High-Level Talent Recruitment Plan of Yunnan Province (High-End Foreign Experts program), and the Key Laboratory of Yunnan Provincial Department of Education of the Deep-Time Evolution on Biodiversity from the Origin of the Pearl River for their support. Nakarin Suwannarach and Jaturong Kumla thank Chiang Mai University for the partial support.

Conflict of interest

HP is employed by the company Zest Lanka International (Private) Limited.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ali, N. A., Jansen, R., Pilgrim, H., Liberra, K., and Lindequist, U. (1996). Hispolon, a yellow pigment from Inonotus hispidus. Phytochemistry 41, 927–929.

Aman Mohammadi, M., Ahangari, H., Mousazadeh, S., Hosseini, S. M., and Dufossé, L. (2022). Microbial pigments as an alternative to synthetic dyes and food additives: a brief review of recent studies. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 45, 1–2. doi: 10.1007/s00449-021-02621-8,

AstaReal (2024). AstaReal: Natural astaxanthin from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Available online at: https://www.astareal.com (accessed on 23 May 2024).

Aulinger, K., Besl, H., Spiteller, P., Spiteller, M., and Steglich, W. (2001). Melanocrocin, a polyene pigment from melanogaster broomeianus (Basidiomycetes). Z. Naturforsch. 56, 495–498. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-7-803,

Aumann, D. C., Cloth, G., Steffan, B., and Steglich, W. (1989). Complexation of cesium 137 by the cap pigments of the bay bolete (Xerocomus badius). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 28, 453–454.

Avalos, J., and Limón, M. C. (2015). Biological roles of fungal carotenoids. Curr. Genet. 61, 309–324. doi: 10.1007/s00294-014-0454-x,

Babitskaya, V. G., and Shcherba, V. V. (1999). Phenolic compounds produced by some basidiomycetous fungi. Microbiology 68, 58–62.

Babitskaya, V. G., Shcherba, V. V., and Osadchaya, O. V. (1998). Melanin pigments from micromycetes. Vestsi Nats. Akad. Navuk Belarusi, Ser. Biyal. Navuk 3, 83–88.

Bao, H. N., Osako, K., and Ohshima, T. (2010). Value-added use of mushroom ergothioneine as a colour stabilizer in processed fish meats. J. Sci. Food Agric. 90, 1634–1641. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.3992,

Bell, A. A., and Wheeler, M. H. (1986). Biosynthesis and functions of fungal melanins. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 24, 411–451.

Belscak-Cvitanovic, A., Nedovic, V., Salevic, A., Despotovic, S., Komes, D., Niksic, M., et al. (2017). Modification of functional quality of beer by using microencapsulated green tea (Camellia sinensis L.) and Ganoderma mushroom (Ganoderma lucidum L.) bioactive compounds. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 23, 457–471. doi: 10.2298/CICEQ160722060B

Bergmann, P., Frank, C., Reinhardt, O., Takenberg, M., Werner, A., Berger, R. G., et al. (2022). Pilot scale production of the natural colorant laetiporic acid, its stability and potential applications. Fermentation 8:684. doi: 10.3390/fermentation8120684

Besl, H., and Bresinsky, A. (1997). Chemosystematics of Suillaceae and Gomphidiaceae (suborder Suillineae). Plant Syst. Evol. 206, 223–242.

Better Nature. (2024). Supercharged plant-based protein. Available online at: https://www.betternature.co.uk/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

BioMyc. (2024). High-quality mushroom ingredients & spawn. Available online at: https://biomyc.eu/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

Cardwell, G., Bornman, J. F., James, A. P., and Black, L. J. (2018). A review of mushrooms as a potential source of dietary vitamin D. Nutrients 10:1498. doi: 10.3390/nu10101498,

Caro, Y., Venkatachalam, M., Lebeau, J., Fouillaud, M., and Dufossé, L. (2017). “Pigments and colorants from filamentous fungi” in Fungal metabolites. Reference series in Phytochemistry. eds. J. M. Mérillon and K. Ramawat (Cham: Springer).

Cerón-Guevara, M. I., Santos, E. M., Lorenzo, J. M., Pateiro, M., Bermúdez-Piedra, R., Rodríguez, J. A., et al. (2021). Partial replacement of fat and salt in liver pâté by addition of Agaricus bisporus and Pleurotus ostreatus flour. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 56, 6171–6181. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.15076

Chatragadda, R., and Dufossé, L. (2021). Ecological and biotechnological aspects of pigmented microbes: a way forward in development of food and pharmaceutical grade pigments. Microorganisms 9:637. doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9030637,

Chatterjee, S., and Pandey, S. (2023). Degradation of complex textile dyes by some leaf-litter dwelling fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 93, 213–223. doi: 10.1007/s40011-022-01379-7

Chattopadhyay, P., Chatterjee, S., and Sen, S. K. (2008). Biotechnological potential of natural food grade biocolorants. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 7, 2972–2985. doi: 10.4314/ajb.v7i17.59211

Chavan, A., Pawar, J., Kakde, U., Venkatachalam, M., Fouillaud, M., Dufossé, L., et al. (2025). Pigments from microorganisms: a sustainable alternative for synthetic food coloring. Fermentation 11:395. doi: 10.3390/fermentation11070395

Chen, X. Q., Zhao, W., Xie, S. W., Xie, J. J., Zhang, Z. H., Tian, L. X., et al. (2019). Effects of dietary hydrolyzed yeast (Rhodotorula mucilaginosa) on growth performance, immune response, antioxidant capacity and histomorphology of juvenile nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 90, 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.068,

Chiang, Y. M., Szewczyk, E., Davidson, A. D., Keller, N., Oakley, B. R., and Wang, C. C. (2009). A gene cluster containing two fungal polyketide synthases encodes the biosynthetic pathway for a polyketide, asperfuranone, in aspergillus nidulans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 2965–2970. doi: 10.1021/ja8088185,

Chinova Bioworks. (2024). Natural preservation solutions. Available online at: https://www.chinovabioworks.com/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

Daniewski, W. M., and Vidari, G. (1999). “Constituents of Lactarius (mushrooms)” in Fortschritte der chemie organischer naturstoffe/Progress in the chemistry of organic natural products. eds. W. A. Ayer, E. V. Brandt, J. Coetzee, W. M. Daniewski, and G. Vidari. 1st ed (Vienna: Springer Nature), 69–171.

Davoli, P., Mucci, A., Schenetti, L., and Weber, R. W. S. (2005). Laetiporic acids, a family of non-carotenoid polyene pigments from fruit-bodies and liquid cultures of Laetiporus sulphureus (Polyporales, Fungi). Phytochemistry 66, 817–823. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.01.023,

de Oliveira, Z. B., Silva da Costa, D. V., da Silva dos Santos, A. C., da Silva Júnior, A. Q., de Lima Silva, A., de Santana, R. C. F., et al. (2024). Synthetic colors in food: a warning for children’s health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 21:682. doi: 10.3390/ijerph21060682

de Souza, R. A., Kamat, N. M., and Nadkarni, V. S. (2018). Purification and characterisation of a Sulphur rich melanin from edible mushroom Termitomyces albuminosus Heim. Mycology 9, 296–306. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2018.1494060,

Delna, N. S., Mishra, R., and Prakash, A. (2025). Molecular and functional characterization of pigment-producing bacteria: exploring secondary metabolites with antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Microbe 9:100540. doi: 10.1016/j.microb.2025.100540,

Deng, H., Chen, J., Gao, R., Liao, X., and Cai, Y. (2016). Adaptive responses to oxidative stress in the filamentous fungal Shiraia bambusicola. Molecules 21:1118. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091118,

Dubost, N. J., Ou, B., and Beelman, R. B. (2007). Quantification of polyphenols and ergothioneine in cultivated mushrooms and correla-tion to total antioxidant capacity. Food Chem. 105, 727–735. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.030

Dufossé, L. (2016). Pigments, microbial; reference module in life sciences. Saint-Denis, France: University of Reunion Island.

Dufossé, L. (2024). “Current and potential natural pigments from microorganisms (bacteria, yeasts, fungi, and microalgae)” in Handbook on natural pigments in food and beverages. ed. R. Schweiggert. 2nd ed (UK: Woodhead Publishing), 419–436.

Durán, N., Teixeira, M. F., De Conti, R., and Esposito, E. (2002). Ecological-friendly pigments from fungi. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 42, 53–66. doi: 10.1080/10408690290825457,

ECHEMI (2025) Global pigment industry transformation driven by innovation. CHEMII Insights Available online at: https://www.echemi.com (accessed on 23 May 2024).

Eisenman, H. C., and Casadevall, A. (2012). Synthesis and assembly of fungal melanin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 93, 931–940. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3757-1

Elkhateeb, W., and Daba, G. (2023). Fungal pigments: their diversity, chemistry, food and non-food applications. Appl. Microbiol. 3, 735–751. doi: 10.3390/applmicrobiol3030051

European Food Safety Authority (2021). Safety assessment of certain natural food colourants. EFSA J. 19:6582. (Accessed 1 December 2025).

European Food Safety Authority. (2025). Available online at: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/about (accessed on 25 Sep 2025).

FDA. (2025). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Available online at: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda (accessed on 25 Sep 2025).

Food Navigator. (2024). News & analysis on food & beverage development & technology. Available online at: https://www.foodnavigator.com/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

Four Sigmatic. (2024). Functional mushrooms & adaptogens. Available online at: https://us.foursigmatic.com/ (accessed on 23 May 2024).

Fu, Y., Yu, Y., Tan, H., Wang, B., Peng, W., and Sun, Q. (2022). Metabolomics reveals dopa melanin involved in the enzymatic browning of the yellow cultivars of east Asian golden needle mushroom (Flammulina filiformis). Food Chem. 370:131295. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131295,

Gadd, G. M. (1982). Melanin production and differentiation in Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128, 1993–2000.

Gawel, K. (2024). A review on the role and function of cinnabarinic acid, a "forgotten" metabolite of the kynurenine pathway. Cells 13:453. doi: 10.3390/cells13050453,

Gill, M., Giménez, A., and Watling, R. (1992). Pigments of fungi, part 26. Incorporation of sodium [1, 2-13C2] acetate into torosachrysone by mushrooms of the genus Dermocybe. J. Nat. Prod. 55, 372–375.

Gil-Ramírez, A., Pavo-Caballero, C., Baeza, E., Baenas, N., Garcia-Viguera, C., Marína, F. R., et al. (2016). Mushrooms do not contain flavonoids. J. Funct. Foods 25, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2016.05.005

Gomes, D. C. (2024). “Fungal pigments: applications and their medicinal potential” in Fungi bioactive metabolites. eds. S. K. Deshmukh, J. A. Takahashi, and S. Saxena (Singapore: Springer).

Google Patents. (1996). Strain of basidiomycete Inonotus obliquus - producer of melanin pigment possessing antiviral and antitumoral activity. Available online at: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2716590C1/ru (accessed on 25 Sep 2025).

Gripenberg, J. (1958). Fungus pigments. VIII. Structure of cinnabarin and cinnabarinic acid. Acta Chem. Scand. 12, 603–610.

Hanson, J. R. (2008). “Pigments and odours of fungi” in The chemistry of Fungi. ed. J. R. Hanson (Cambridge, UK: The Royal Society of Chemistry), 127–142.

Haritha, M., and dos Santos, J. C. (2021). Colors of life: a review on fungal pigments. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 41, 1153–1177. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2021.1901647

Harki, E., Talou, T., and Dargent, R. (1997). Purification, characterisation and analysis of melanin extracted from tuber melanosporum Vitt. Food Chem. 58, 69–73.

Hasnat, M. A., Pervin, M., and Lim, B. O. (2013). Acetylcholinesterase inhibition and in vitro and in vivo antioxidant activities of Ganoderma lucidum grown on germinated brown rice. Molecules 18, 6663–6678. doi: 10.3390/molecules18066663,

Hornyak, T. J. (2018). Commentary on tyrosinase inhibitor development. J. Invest. Dermatol. 138, 1470–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.03.003

Hou, R., Liu, X., Xiang, K., Chen, L., Wu, X., Lin, W., et al. (2019). Characterization of the physicochemical properties and extraction optimization of natural melanin from Inonotus hispidus mushroom. Food Chem. 277, 533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.002,

Huang, R., Ding, R., Liu, Y., Li, F., Zhang, Z., and Wang, S. (2022). GATA transcription factor WC2 regulates the biosynthesis of astaxanthin in yeast Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Microb. Biotechnol. 15, 2578–2593. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.14115,

Huang, Y. T., Onose, J., Abe, N., and Yoshikawa, K. (2009). In vitro inhibitory effects of pulvinic acid derivatives isolated from Chinese edible mushrooms, boletus calopus and Suillus bovinus, on cytochrome P450 activity. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 73, 855–860. doi: 10.1271/bbb.80759,

IndexBox. (2025). Global Organic Pigments Market Report 2025. Available online at: https://www.indexbox.io/store/world-synthetic-organic-coloring-matter-and-pigments-market-report-analysis-and-forecast-to-2020/ (accessed on 25 Sep 2025).

Jin, L. (2010). Stability and safety assessment of the exudates from Lentinula edodes sp. used as a food colorant [master’s thesis]. China: Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Kaur, P., and Anand, S. (2025). “From fungi to food safety: advancing mycotoxin research and solutions” in Research on mycotoxins—From Mycotoxigenic Fungi to innovative strategies of diagnosis, control and detoxification. eds. M. Razzaghi-Abyaneh, M. Shams-Ghahfarokhi, and M. Rai (London, UK: Intech Open).

Keller, N. P., Turner, G., and Bennett, J. W. (2015). Fungal secondary metabolism — from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 937–947. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1286,

Kim, S. (2020). Antioxidant compounds for the inhibition of enzymatic browning by polyphenol oxidases in the fruiting body extract of the edible mushroom Hericium erinaceus. Foods 9:951. doi: 10.3390/foods9070951,

Kim, J. H., Kim, S. J., Park, H. R., Choi, J. I., Ju, Y. C., Nam, K. C., et al. (2009). The different antioxidant and anticancer activities depending on the color of oyster mushrooms. J. Med. Plant Res. 3, 1016–1020. Available at: http://www.academicjournals.org/JMPR

Knight, D. W., and Pattenden, G. (1976). Synthesis of the pulvinic acid pigments of lichen and fungi. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. (1976), 660–661.

Koyyalamudi, S. R., Jeong, S. C., Song, C. H., Cho, K. Y., and Pang, G. (2009). Vitamin D2 formation and bioavailability from Agaricus bisporus button mushrooms treated with ultraviolet irradiation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 3351–3355. doi: 10.1021/jf803908q,

Kozarski, M., Klaus, A., Vunduk, J., Zizak, Z., Niksic, M., Jakovljevic, D., et al. (2015). Nutraceutical properties of the methanolic extract of edible mushroom Cantharellus cibarius (fries): primary mechanisms. Food Funct. 6, 1875–1886. doi: 10.1039/C5FO00312A,

Kurt, A., and Gençcelep, H. (2018). Enrichment of meat emulsion with mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) powder: impact on rheological and structural characteristics. J. Food Eng. 237, 128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.05.028

Leasca, S. (2024). More Than 10,000 Chemical Food Additives Ended Up in the U.S. Food System — Here's Why. Available online at: https://www.foodandwine.com/fda-food-additives-gras-designation-loophole-8761817 (accessed on 25 Sep 2025).

Lee, I. K., and Yun, B. S. (2011). Styrylpyrone-class compounds from medicinal fungi Phellinus and Inonotus spp., and their medicinal importance. J. Antibiot. 64, 349–359. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.2,

Li, C., and Oberlies, N. H. (2005). The most widely recognized mushroom: chemistry of the genus amanita. Life Sci. 78, 532–538. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.09.003,

Li, X., Wu, W., Zhang, F., Hu, X., Yuan, Y., Wu, X., et al. (2022). Differences between water-soluble and water-insoluble melanin derived from Inonotus hispidus mushroom. Food Chem. X 16:100498. doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100498,

Libkind, D., Moliné, M., Sampaio, J. P., and van Broock, M. (2009). Yeasts from high-altitude lakes: influence of UV radiation. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 69, 353–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2009.00728.x

Lin, L., and Xu, J. (2020). Fungal pigments and their roles associated with human health. J. Fungi 6:280. doi: 10.3390/jof6040280,

Lin, L., and Xu, J. (2023). Production of fungal pigments: molecular processes and their applications. J. Fungi 9:44. doi: 10.3390/jof9010044

Löhr, N. A., Eisen, F., Thiele, W., Platz, L., Motter, J., Hüttel, W., et al. (2022). Unprecedented mushroom polyketide synthases produce the universal anthraquinone precursor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Eng. 61:e202116142. doi: 10.1002/anie.202116142,

Löhr, N. A., Rakhmanov, M., Wurlitzer, J. M., Lackner, G., Gressler, M., and Hoffmeister, D. (2023). Basidiomycete non-reducing polyketide synthases function independently of SAT domains. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 10:17. doi: 10.1186/s40694-023-00164-z,

Mansuri, A. F., Sarmah, D. K., and Saikia, A. N. (2017). Antioxidant properties of some common oyster mushrooms grown in Northeast India. Indian Phytopathol. 70, 98–103. doi: 10.24838/ip.2017.v70.i1.48998

Mapari, S. A., Thrane, U., and Meyer, A. S. (2010). Fungal polyketide azaphilone pigments as future natural food colorants? Trends Biotechnol. 28, 300–307. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.03.004,

Market Data Forecast. (2024). Natural Food Colors Market Size, Share & Trends 2024–2027. Available online at: https://www.marketdataforecast.com/ (accessed on 25 Sep 2025)