Abstract

Breast cancer (BC), cervical cancer (CC), and ovarian cancer (OC) are among the most prevalent and life-threatening malignancies affecting women worldwide. While conventional therapies have improved patient outcomes, they often result in suboptimal survival and quality of life. In recent years, ultrasound (US) has emerged as a promising therapeutic tool, not only for its well-established role in diagnostic imaging but also for its safety, deep tissue penetration, and real-time capabilities. The integration of US with nanotechnology has further expanded its potential, enabling nanoparticles (NPs) to function as contrast agents, drug delivery vehicles, and energy mediators in cancer theranostics. This review explores the synergistic effects of NPs and US in the diagnosis and treatment of breast and gynecologic cancers, with a focus on OC and CC, while also including BC due to its clinical significance and shared imaging modalities. We examine the biophysical mechanisms underlying US-based therapies, the design of multifunctional nanoplatforms, and their applications in enhanced imaging, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), sonodynamic therapy (SDT), and US-triggered drug delivery. Finally, we discuss the translational challenges and future prospects of these innovative technologies, emphasizing their potential to transform the clinical management of BC, CC, and OC.

1 Introduction

Cancer remains a leading threat to global health, necessitating the development of novel therapeutic strategies to overcome the limitations of conventional treatments (1). Nanotechnology has emerged as a transformative tool in biomedicine, enabling breakthroughs in diagnostics and targeted drug delivery (2).

The development of multifunctional nanoplatforms that integrate imaging and therapeutic capabilities represents a significant advancement in theranostic medicine (3). Ultrasound (US) technology offers distinct advantages for cancer management, including its excellent safety profile, real-time imaging capability, and clinical practicality. These features make it particularly valuable for managing both breast and gynecologic cancers (4–6). Recent advances have substantially expanded US applications through nanoparticle (NP)-enhanced approaches, enabling more precise interventions such as targeted drug delivery, sonodynamic therapy (SDT), and high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for tissue ablation. The strategic combination of US with nanotechnology creates powerful synergies that address multiple limitations of conventional cancer therapies. This integrated approach enhances both diagnostic accuracy and treatment efficacy while demonstrating strong potential for clinical translation (3).

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of NP-enhanced US applications in breast and gynecologic malignancies, including CC and OC. We examine current treatment modalities, fundamental biophysical mechanisms of US, and recent advances in NP-enhanced technology. The integration of cutting-edge nanotechnology with established US techniques shows considerable promise for developing more effective diagnostics and personalized treatments for these cancers (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Nanoplatform-based ultrasound application structural framework.

2 Current approaches and diagnostic limitations

2.1 Breast cancer

BC is the most prevalent malignancy affecting women worldwide (7). It primarily arises from uncontrolled ductal cell proliferation that can develop into benign or metastatic tumors following carcinogen exposure (8). Current treatment protocols rely heavily on hormone therapies, particularly estrogen blockers such as tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (letrozole, anastrozole, and exemestane) (9). However, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), an especially aggressive subtype, presents significant therapeutic challenges. Current approaches are limited primarily to chemotherapy and anti-VEGF monoclonal antibodies like bevacizumab (10, 11). The emergence of nanomedicine has revolutionized BC treatment strategies, offering improved imaging capabilities and targeted therapeutic approaches. Cutting-edge molecular biology techniques facilitate the design of sophisticated multifunctional nanostructures capable of delivering chemotherapeutic agents, particularly in drug resistant cases. A recent review indicates promising nanotheranostic strategies for TNBC. These include a CRISPR-Cas detection system and engineered CAR-T cells with nanoliposomal viral vectors to target hypoxic CSCs. Engineered liposomes and polymeric NPs show particular promise for personalized treatment approaches through selective targeting of BC cells to induce apoptosis, offering new potential for managing refractory TNBC cases (12).

2.2 Cervical cancer

CC is the fourth most common gynecologic malignancy globally, accounting for over 300, 000 deaths annually (13). Treatment modalities include radiotherapy, surgical resection, and chemotherapy. Platinum-based agents like cisplatin and paclitaxel are commonly used (14–16). However, these conventional approaches face significant challenges, including high recurrence rates (35%) and substantial treatment-related toxicities such as multidrug resistance (MDR) and systemic organ damage (17, 18). In this context, nanobiotechnology has emerged as a promising therapeutic alternative. Various nanostructures—including metal-based, carbon-based, lipid-based, and polymer-based NPs—demonstrate considerable potential for improving CC treatment outcomes (19). These novel approaches aim to overcome the limitations of traditional therapies while minimizing adverse effects.

2.3 Ovarian cancer

OC remains one of the most aggressive gynecologic malignancies, with mortality rates exceeded only by CC (13). While current treatment modalities, including surgical debulking, platinum-based chemotherapy, and radiotherapy continue to evolve (20), their clinical efficacy remains limited by several critical challenges (21). Surgical interventions carry significant risks of peritoneal and abdominal lymph node metastasis, often leading to severe postoperative complications and increased mortality (22). Chemotherapeutic approaches, though widely employed, are hampered by substantial toxicity profiles and the development of drug resistance. Radiotherapy demonstrates restricted applicability and often fails to achieve durable remission, with repeated treatments potentially compromising progression free survival (23, 24). These persistent challenges highlight the critical need for innovative therapeutic strategies. NP-enhanced US approaches, especially those integrating imaging with targeted therapeutic delivery, provide a transformative framework for real-time treatment monitoring and precision oncology in OC management (21, 25).

3 Biophysical effects of ultrasound

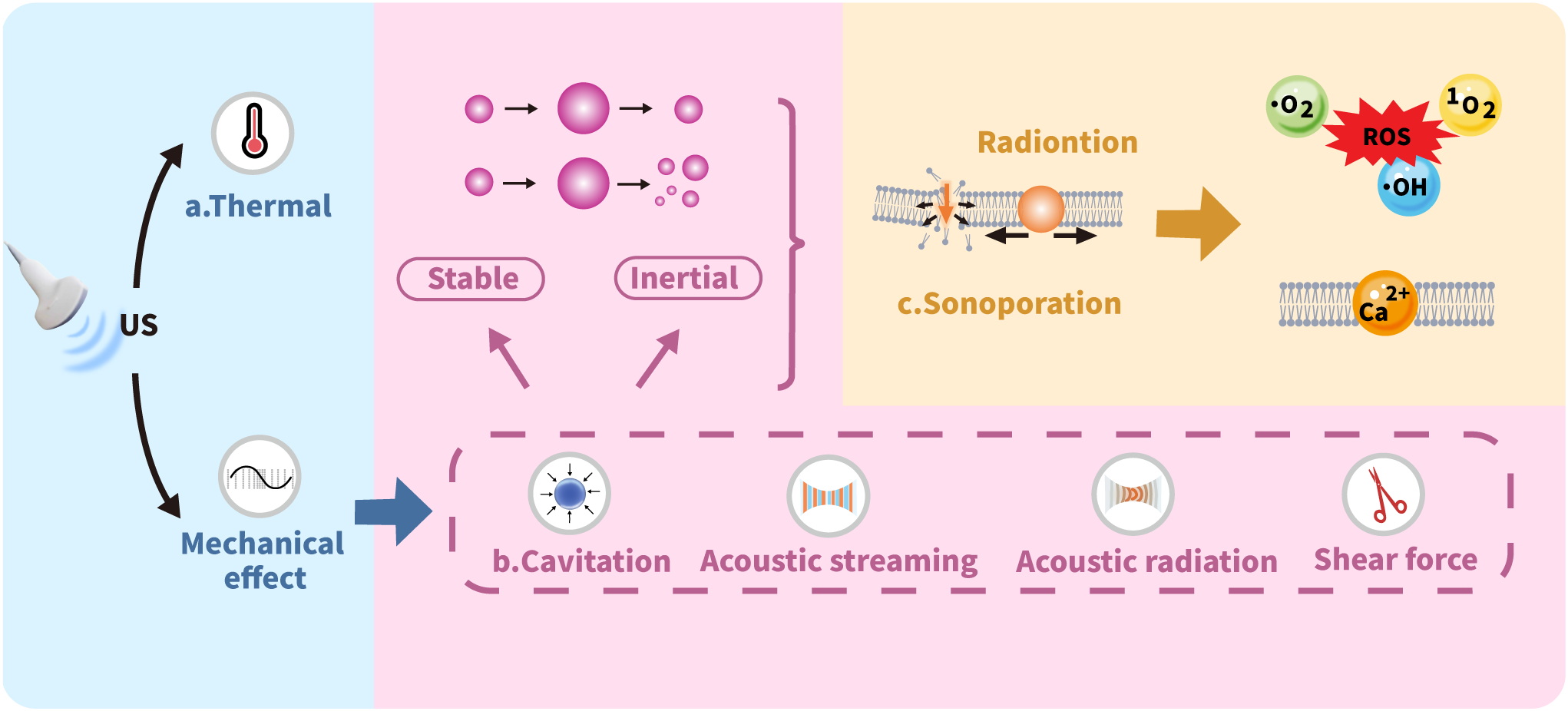

US imaging serves as a widely adopted clinical tool for disease diagnosis and assessment. This technology offers significant advantages including noninvasiveness, cost-effectiveness, and real-time imaging capability, while providing deep tissue penetration without ionizing radiation exposure (26–29). The therapeutic potential of US is mediated through distinct thermal and mechanical mechanisms, with key processes illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Mechanisms of ultrasound biophysical effects.

3.1 Thermal effect

The thermal effects of US primarily arise from the temperature increase in the medium due to US energy absorption. The generated heat is directly proportional to both the wave frequency and exposure time while inversely proportional to the specific absorption coefficient of the target tissue. Consequently, media with higher absorption coefficients exhibit more pronounced temperature elevations, leading to more significant thermal effects on tissues (30, 31). Elevated temperatures typically induce changes in the fluidity of cell membrane phospholipid bilayers, generally enhancing membrane permeability to nanomedicines. Even moderate temperature increases can induce structural deformation in NPs. This may progress to complete disruption through US-based expansion, ultimately triggering NPs rupture that facilitates localized drug release. Such thermally responsive materials, commonly composed of polymers or lipids, called as heat-sensitive NPs, which US can activate to improve targeted drug release. Additionally, US-triggered thermal effects enable localized thermal ablation, particularly through HIFU application (32).

3.2 Cavitation

Cavitation significantly enhances sonoporation effects when microbubbles (MBs) are introduced into the cellular microenvironment. MBs serve as contrast agents to improve US image quality. To achieve optimal imaging and therapeutic outcomes while minimizing risks, careful adjustment of US frequency and intensity is required to preserve bubble integrity. Beyond imaging, MBs enable targeted drug delivery by using US to selectively disrupt bubbles at specific sites, triggering controlled drug release. Cavitation occurs in two distinct forms: stable cavitation and inertial cavitation. Stable cavitation features sustained, nonlinear oscillations of gas-filled MBs around an equilibrium radius. This process continues until the encapsulated gas fully dissolves into the bloodstream and is cleared through pulmonary exhalation. Inertial cavitation presents a markedly different behavior, defined by the catastrophic implosion of MBs that happens immediately when US is applied (32–35).

3.3 Sonoporation

Sonoporation refers to the US induced formation of transient pores in cell membranes through mechanical interactions. This process physically compromises membrane integrity, creating micropores that facilitate passive entry of drug molecules, NPs, and genetic material into cells (36). Cavitation plays a pivotal role in sonoporation by generating gas-filled MBs that undergo creation, oscillation, and eventual disintegration under US exposure. When US waves interact with MBs, they induce high-frequency oscillations that produce fluid shock waves and exert shear forces on cell membranes. These mechanical effects alter membrane structure and significantly enhance permeability, thereby improving cellular uptake of therapeutic NPs (32).

4 Clinical application of US

4.1 Nanoplatforms for US imaging

The growing demand for early disease detection and diagnosis continues to drive innovations in imaging technologies and contrast agent development. The ongoing advancement of NPs as imaging contrast agents holds significant promise for diverse clinical applications in the future (36). Their appeal in biomedical imaging stems from multifunctional targeting capabilities-encompassing passive, active, and physical targeting mechanisms. A key advantage lies in their nanoscale dimensions, which facilitate the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect in tumor tissues. This property significantly prolongs contrast agent retention at target sites and markedly improves imaging efficacy (37). While conventional MB contrast agents (typically 1-10 μm in diameter) remain the clinical gold standard for blood pool imaging in contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS), their inability to extravasate beyond the vasculature limits their utility for extravascular targeting. Recent years have consequently witnessed the rise of nanoscale ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs) as a transformative approach for molecular US imaging (6). Consequently, nanoscale UCAs have emerged as a transformative platform for molecular US imaging. These nanoplatforms enable precise visualization of tumor tissues at the molecular level, and their representative designs and applications are systematically summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

| Cancer type | Nanoparticle | Size | Effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | NBs | 478.2 ± 29.7 nm | • This ND showed good US enhancement, displaying a peak intensity of 104.5 ± 2.1 dB under US contrast scanning. | (40) |

| NBs-Her | 613.0 ± 25.4 nm | • NBs-Her improves the quality of contrast-enhanced US imaging and also penetrates tumor tissue for extravascular imaging, but does not penetrate normal skeletal muscle. | (41) | |

| MSNs | 1-30 µm | • Increasing US image contrast. | (43) | |

| Silica NP | 200 nm | • It can be used as a highly effective contrast agent for color Doppler US imaging of human breast tissue. | (44) | |

| Cur-NDs-2 | 101.2 nm | • Even at low concentrations, chitosan nanodroplets produce a strong ultrasonic contrast through the droplet-to-bubble transition. | (45) | |

| DiR-MB | 0.4-6 μm | • US-targeted DiR-MB disruption and then conversion to DiR-NP identifies and directs inaccessible cancer lesions. | (46) | |

| Na2CO3/Fe3O4@PLGA/ Cy5.5/RGD NPs |

117.6 nm | • This pH-responsive NP system provides good effects in MR/US/fluorescent imaging. | (51) | |

| Cervical Cancer | AB-NB | 74.6 ± 16.7 nm | • OVCAR-3 tumors showed higher peak US signal intensity and lower washout compared to CA-125-negative SKOV-3 tumors. Targeted MBs also exhibited increased tumor retention and prolonged echogenicity compared to untargeted NBs. | (42) |

| Ovarian Cancer | FA-OINPs | 300 nm | • It has good contrast as a US/PA contrast agent both in vivo and in vitro. | (54) |

Nanoplatforms for ultrasound imaging.

4.1.1 US molecular imaging

The engineering of molecularly specific antibodies or ligands onto ultrasound contrast agents (UCAs) creates targeted nanoplatforms—including nanobubbles, echogenic liposomes, and nanodroplets—that enable molecular ultrasound imaging by specifically binding to disease markers through ligand-receptor interactions. This advancement transforms ultrasound from a conventional anatomical imaging tool into a molecular-targeted modality, where functionalized UCAs serve as the fundamental component by concentrating in diseased tissues and enhancing lesion-specific signals. Nanoscale UCAs further excel in tumor imaging due to their superior vascular penetration via the EPR effect and modifiable surfaces for improved target retention, with each variant offering distinct imaging advantages (6, 38, 39). The comparison between various UCAs used in molecular US imaging is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

| Type | Size | Core | Shell | Advantage | Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanobubble | <1μm | Perfluorocarbon Gas | Lipid, Polymer | • Small size • Potential for long circulation |

• Weaker Signal than microbubbles • Poor physical stability • Difficult fabrication |

| Microbubble | 1-10 μm | Perfluorocarbon Gas | Lipid, Albumin, Polymer | • Strong Signal, clinical gold standard • Well-established technology |

• Large Size • Short circulation half-life |

| Gas Vesicle | 45-800nm | Air | Protein | • Ultra-stable | • Potential immunogenicity |

| Nanodroplet | <1μm | Perfluorocarbon Liquid | Lipid, Polymer, Surfactant | • Activatable via phase-change • Capable of tissue extravasation for enhanced targeting |

• Requires high-energy ultrasound for activation • Risk of embolism from spontaneous phase change • Weak echo signal in liquid state |

| Echogenic Liposomes | 100–500 nm | Gas or Perfluorocarbon Liquid/Gas | Phospholipid Bilayer | • Mature liposome platform • Easy functionalization |

• Weaker and less stable acoustic signal • Challenges in consistent gas/liquid loading |

Comparison of ultrasound contrast agents for molecular ultrasound imaging.

Recent advances in NP-enhanced UCAs have substantially improved imaging capabilities. Gas-filled nanobubbles (NBs) show particular promise with their surfactant-stabilized phospholipid shells and fluorocarbon cores. Yang et al. pioneered HER2-targeted NBs using biotin-streptavidin interactions, achieving enhanced US signals despite immunogenicity limitations (40). Jiang et al. subsequently improved this approach through covalent herceptin conjugation, creating more stable HER2-targeted NBs that maintained tumor specific signal enhancement for 40 minutes (41). Further developments have expanded the UCA repertoire. Gao et al. developed CA125 antibody-coupled NBs demonstrating twofold greater signals in OC xenografts (42). Milgroom’s team created herceptin-functionalized mesoporous silica NPs for BC imaging (43), while Martinez et al. designed gas-filled hollow silica NPs that enhance Doppler imaging (44).

Innovative approaches continue to emerge. Baghbani et al. introduced phase transitioning curcumin-loaded chitosan nanodroplets (45), and Lin et al. developed a convertible DiR-MB system for intraoperative tumor visualization (46). These technologies collectively advance US from conventional imaging toward precise cancer diagnosis and image-guided therapy. Enhanced stability, improved specificity, and multifunctionality characterize this new generation of contrast agents.

4.1.2 Multimodal US imaging

Multimodal US imaging represents a major diagnostic advance by integrating complementary techniques to provide comprehensive molecular level information (47). This strategy leverages the unique advantages of individual imaging methods while overcoming their limitations through nanotechnology-enabled probes (48). In cancer diagnosis and treatment monitoring, combining photoacoustic (PA), US, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) within multifunctional nanoplatforms shows particular promise (49). These systems utilize PA’s excellent optical contrast, US’s real-time capability, and MRI’s superior soft tissue resolution, creating synergistic platforms that outperform single modality approaches and enable more accurate tumor evaluation (49).

Integrating MRI and US combines their complementary strengths: MRI provides high spatial resolution for deep tissues, while US enables real-time imaging. Together they improve sensitivity and reduce acquisition time (50). Nanocontrast agents further enhance this approach by boosting each modality’s sensitivity and enabling targeted tumor visualization (50). For example, Nie et al. developed a pH-responsive NP system that generates CO2 in acidic tumor environments. This produces strong US echoes while enabling excellent MRI and fluorescence imaging (51). This smart platform demonstrates the potential of combining MRI/US/fluorescence through tumor microenvironment responsive agents (51).

PA imaging generates acoustic waves through laser induced photothermal effects, detected and converted into PA signals. Combined with US, it synergistically enhances imaging by leveraging PA’s high optical selectivity with US’s deep penetration and resolution (52, 53). Liu et al. created folate receptor-targeted NPs (FA-OINPs) that demonstrated robust US/PA contrast enhancement in both cellular systems and OC xenografts (54). This platform successfully enabled image guided therapy, showing strong potential for clinical translation (54).

4.2 Nanoplatform-based US targeted therapy

Recent advances in NP-enhanced US have expanded its applications in oncology, including drug delivery, HIFU, and SDT (55–57). Engineered NPs leverage their small size and surface properties to achieve tumor targeting via the EPR effect and specific tumor microenvironment interactions (58). These NPs enhance US imaging, improve SDT efficacy, augment HIFU ablation, and enable controlled drug release (56, 59, 60). Representative therapeutic nanoplatforms are summarized in Table 3. Furthermore, they can integrate multiple imaging and therapeutic functions into single theranostic platforms (61). These combined systems, detailed in Table 4, enable simultaneous diagnosis and treatment while providing real-time monitoring capabilities. The integration of different modalities in these nanoplatforms significantly improves treatment precision and therapeutic outcomes.

Table 3

| Cancer type | Nanoparticle | Size | Effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanodroplets | 39.2 ± 3 nm | • In the BC mice models, US-mediated therapy with doxorubicin-loaded PFH nanodroplets showed excellent anti-cancer effects characterized by tumor regression. | (63) | |

| PFP/ICG/DOX@LIP | 362.23 nm | • Such PFP nanodroplets with phase/size tunable properties enable site-specific drug delivery efficiently and exhibit their potent in cancer theranostics. | (64) | |

| Breast Cancer | CLs | 81 ± 2 nm | • The efective utilization of liposomes as a delivery system for curcumin, thereby ofering a promising avenue for targeted breast and other cancer treatments. | (67) |

| TRA-liposomes | 101.10 ± 1.13 nm | • Exposing the liposomes to LFUS triggered drug release which increased with the increase in power density. | (68) | |

| FA-PL-dMSN | 169 ± 47 nm | • Localized enhancement of the mechanical effects of HIFU in cancer cells. | (71) | |

| Lip-ABC | 174.8 ± 58.26 nm | • In an in vitro synergistic HIFU ablation of mammary tumors in bovine liver and BALB/c nude mice, Lip-ABC outperformed controls. | (74) | |

| Catalase@MONs | 145.9 nm | • It can serve as both a contrast agent for US-guided HIFU tumor ablation and a HIFU synergist. | (75) | |

| Mn-MOF | 70 nm | • It catalyzes the production of O2 from H2O2 to alleviate tumor hypoxia, while decreasing the expression of GSH and GPX4, thereby enhancing SDT and producing better antitumor effects in H22- and 4T1-loaded mice. | (82) | |

| T80(T-ce6/PL) | 18.28 ± 8.49 nm | • Intracellular ROS production was significantly elevated in MCF-7 human BC cells after US exposure. | (85) | |

| BFIP | 114 nm | • BFIP demonstrates superior carrier separation over bismuth fluoride and generates abundant ROS under US. It also depletes glutathione via oxidative pathways, disrupting the TME through oxidative stress. | (86) | |

| LDH-MTX@CMM-Ce6 | 225.1 ± 9.5 nm | • This formulation achieves homologous BC targeting and induces potent apoptosis by combining MTX-mediated cell cycle arrest with ultrasound-triggered SDT. | (87) | |

| IR780@LD-Fe3O4/OA | 217.35 ± 13.53 nm | • Providing accurate and effective SDT for MDR BC. | (88) | |

| CpMBs | 2.02 ± 1.5 μm | • Enhancement of siRNA transfection efficiency and porphyrin uptake in MCF-7 cells by sonoporation effect. | (94) | |

| siHIF@CpMB | 1-7 μm | • Ultrasound-triggered siHIF@CpMBs-to-NPs conversion boosts tumor delivery of porphyrin/siRNA through cavitation. | (95) | |

| ABCG2-siRNA-loaded PEAL NPs | 131.5 ± 6.5 nm | • ABCG2-siRNA-loaded NP with UTMD effectively silenced the ABCG2 gene and enhanced ADR susceptibility in MCF-7/ADR (ADR-resistant human cancer cells). | (96) | |

| (G5-TPGS@y-CDs)-DOX | 279.2 nm | • It can overcome the MDR of cancer cells and effectively inhibit the growth of cancer cells and tumors. | (92) | |

| SLNs | 450.9 nm | • The TNO variant it produces can be used as a potential stimulus response platform for site-specific delivery of chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-FU for the treatment of CC. | (66) | |

| Cervical Cancer | PEI-FA-DSTNs | 173 ± 15 nm | • It is a potent drug delivery system that, in combination with SDT, enhances the anticancer activity of curcumin. | (83) |

| AIBA@MSN | 80–100 nm | • Under hypoxic conditions, azo radicals induce tumor cell death via the non-oxygen radical pathway. | (84) | |

| Bubble liposomes | 500nm-1μm | • Bubble liposomes in combination with US are an excellent non-viral vector system for IL-12 cancer gene therapy. | (65) | |

| Fe3O4@SiO2-Ce6, FSC | 460 nm | • It improves the efficacy of SDT and applies it to the in vitro treatment of OC. | (80) | |

| Ovarian Cancer | SIM@TR-NPs | 119.1 ± 1.9 nm | • The platform converts cold to hot tumors via ICD and TAM modulation, showing potent ovarian cancer suppression and TME reprogramming. | (89) |

| PSP@MB | 500 nm | • US biophysical effects with PSP@MB delivery of ALDH1-shRNA promotes OCSC apoptosis. | (93) |

Nanoplatforms for ultrasound-based therapy.

Table 4

| Cancer type | Nanoparticle | Size | Effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | PCSTD-Gd | 309.5 ± 39.4 nm | • CSTD enhances tumor targeting via amplified EPR effects, boosts MRI sensitivity with a higher r1 relaxation rate, improves gene delivery through efficient DNA compaction and serum resistance, and increases drug loading capacity. | (103) |

| Doc-PFH@SL@PD-HA | 248.07 ± 5.74 nm | • Enhancing US imaging signals and facilitating drug release. | (98) | |

| LP@PFH@HMME | 105 ± 1.64 nm | • This nanoplatform enables robust 19F MRI/CEUS bimodal imaging, offering excellent aqueous solubility, a long T2 relaxation time (1.072 s), and high 19F content for sensitive 19F MRI. It also promotes effective nanomedicine accumulation after intravenous injection. | (99) | |

| AS1411-PLGA@FePc@PFP | 201.87 ± 1.60 nm | • This dual-mode PA/US contrast agent enables precise diagnostic imaging and therapy guidance, while exhibiting effective NIR-triggered heating for potent antitumor effects in vitro and in vivo. | (100) | |

| LIP3 | 200 nm | • It features active targeting, bimodal imaging, visualization of drug release, and precise treatment in the presence of LIFU. | (101) | |

| Her2-GPH NPs | 282.3 nm | • Her2-functionalized NPs significantly enhanced US/MRI molecular imaging of target cells. It acts as an effective light absorber and specifically induces SKBR3 cell death under near-infrared laser irradiation. | (102) | |

| Cervical Cancer | PFeRu-PL@SiO2(R) NPs | 225 nm | • It enables MRI/US dual-modality imaging-guided synergistic HIFU for CC. | (105) |

| Ovarian Cancer | AIPH-MSTN@BSA-MnO2@CCM | 225.9 ± 1.7 nm | • US-triggered AIPH decomposition amplifies TiO2-mediated ROS/imaging, while CCM coating enables targeted tumor delivery through homologous targeting and immune evasion. | (104) |

Nanoplatforms for combined imaging and therapy.

4.2.1 US- guided drug delivery

Beyond imaging, US enables targeted drug delivery by triggering controlled release from NPs and enhancing tumor penetration (32). Its deep tissue reach and safety make US ideal for activating NPs carrying drugs, genes or proteins (3, 62). US enhances therapy through three primary mechanisms: releasing drugs from NPs, increasing tumor NPs uptake, and improving tumor penetration (32).

State-of-the-art US-triggered nanocarriers show remarkable potential for targeted oncological interventions. Baghbani et al. developed adriamycin-loaded alginate nanodroplets that showed both enhanced anticancer effects and durable US contrast under sonication (63). Sheng et al. confirmed the potential of tunable nanodroplets for US guided BC treatment (64). Suzuki’s team achieved successful IL-12 gene delivery to tumors using bubble liposomes combined with US, inducing local immune responses (65). Innovative approaches include thermo-sensitive nanoorganogels (TNOs) incorporating solid lipid NPs (SLNs) for 5-FU release in CC under thermal/US stimulation (66), and curcumin-loaded liposomes that exhibited improved stability and antitumor effects when combined with US and MBs (67). Furthermore, Elamir et al. developed trastuzumab-functionalized immunoliposomes showing power dependent drug release under low frequency US (68). These US-based nanoplatforms enable focused drug release within the US target area, allowing for dose reduction and selective tumor targeting while minimizing systemic side effects (32, 65–68). Collectively, these advances highlight the transformative potential of US-triggered NP systems for precision cancer therapy.

4.2.2 High-intensity focused ultrasound

HIFU is an emerging noninvasive ablation technique for localized tumors. By concentrating low energy US on target tissues, HIFU induces tumor cell necrosis through instantaneous thermal effects, cavitation, and mechanical forces (69). NP integration has significantly enhanced HIFU therapy. NPs improve ablation efficiency while minimizing damage to surrounding healthy tissues (3). Notably, modern multifunctional NPs serve dual roles as HIFU potentiating agents and diagnostic contrast agents, enabling precise image-guided ablation procedures (70).

NP-enhanced HIFU therapy improves tumor ablation precision and efficacy. Adem Yildirim et al. developed phospholipid capped mesoporous silica NPs (MSNs) that locally amplify HIFU’s mechanical effects in BC cells (71). Phase change NPs have further enhanced HIFU efficacy by modifying the acoustic microenvironment to improve energy deposition in tumors (72, 73). Feng et al.’s ammonium bicarbonate-loaded liposomes (Lip-ABC) demonstrated superior stability and tumor accumulation, significantly enhancing HIFU ablation in both ex vivo and in vivo models (74). Liu et al. created a catalytic nanoreactor (catalase@MONs) that serves as both UCA and HIFU synergist through oxygen generation (75). These nanoplatforms address key challenges in HIFU therapy by improving targeting precision, reducing required energy doses, and integrating diagnostic capabilities.

4.2.3 Sonodynamic therapy

SDT combines low intensity US with specialized sensitizers to generate reactive oxygen species. This approach induces cancer cell death through oxidative damage and is particularly effective for deep seated tumors (76, 77). Traditional SDT faces limitations due to suboptimal sensitizer performance. Recent advances in nanomedicine have led to engineered nanosensitizers that enhance tumor accumulation, improve ROS generation efficiency, and enable multifunctional theranostic capabilities (78–80). NP-based systems overcome depth limitations by focusing US energy in deep tissues. They transform SDT into a clinically viable treatment option through enhanced tumor targeting and therapeutic performance (76–79, 81).

Significant advancements include Zhou et al.’s magnetically guided nanorobots that deliver sonosensitizers to OC sites (80). Xu et al.’s Mn-MOF nanosensitizers alleviate tumor hypoxia and suppress antioxidant defenses (82). Malekmohammadi et al. developed folate targeted silica titanium dioxide mesoporous NPs for combined chemo-SDT in CC (83) and Wang et al. designed AIBA@MSNs to induce immunogenic cell death in CC through non-oxygen-dependent pathways (84). Further innovations include Kang’s Tween 80-based nanocarriers for BC specific SDT (85), and Zhu’s bismuth-based heterostructures that synergize radiotherapy with SDT (86). Li’s cell membrane camouflaged platform enables chemo-SDT (87), while Shi’s lipid droplet-based system overcomes multidrug resistance in BC (88). Wang’s NPs combine SDT with immunotherapy to reprogram macrophages (89).These developments collectively demonstrate how engineered NPs are overcoming traditional SDT limitations by improving sensitizer delivery, enhancing ROS generation, enabling combination therapies, and integrating diagnostic capabilities for more effective cancer treatment.

4.2.4 Ultrasound-targeted microbubble destruction

UTMD has emerged as a safe strategy for enhanced drug and gene delivery (62). This technology leverages dual mechanisms: increasing vascular and cellular membrane permeability through sonoporation, and facilitating in situ MBs-to-NPs conversion to improve cellular uptake and therapeutic outcomes (70). MBs serve as multifunctional US-based carriers. They enable targeted drug release and CEUS, enabling real-time treatment monitoring and precise spatiotemporal control of delivery (90). Their structure supports versatile cargo loading, accommodating drugs, genes, NPs, or therapeutic gases (91).

UTMD technology enhances cancer therapy through improved drug/gene delivery and real-time monitoring. Li et al. developed yellow fluorescent carbon dot/dendrimer nanocarriers that enhance drug uptake and efficacy in MDR BC via sonoporation effects (92). Similarly, PSP@MB NPs exhibit US-triggered, GSH-responsive properties for improved OC stem cell treatment through enhanced endocytosis (93). For gene therapy, Zhao’s porphyrin-grafted MBs deliver FOXA1-siRNA and convert to NPs under low frequency US (94). Sun et al. extended this approach using HIF1α-siRNA-loaded MBs (95). Bai’s team demonstrated UTMD-enhanced delivery of ABCG2-siRNA NPs can overcome chemotherapy resistance in vivo (96). These studies establish UTMD as a powerful platform for enhanced delivery, real-time imaging guidance, and overcoming treatment resistance.

4.2.5 US-based theranostics

Nanotheranostic platforms combine imaging and therapeutic capabilities within single NP systems. These integrated approaches enable real-time monitoring of drug distribution while facilitating therapeutic intervention (97).

Mou et al. developed Doc-PFH@SL@PD-HA NPs that simultaneously enhance US imaging under NIR irradiation while delivering combined photothermal-chemotherapy (98). Chen’s LP@PFH@HMME liposomes enable bimodal imaging-guided SDT and immunotherapy in TNBC (99). He’s A-FP NPs achieve targeted BC therapy with integrated PA/US imaging (100). Zhao’s LIP3 nanoplatform exemplifies sophisticated design with active targeting, bimodal imaging, and visualized drug release under LIFU guidance (101). Further innovations include Dong’s HER-2-targeted nanocarriers for US/MRI and photothermal therapy (102), Gong’s Gd-based dendritic polymers for MRI-guided chemotherapy (103), and Xie’s dual-responsive AMBC platform overcoming hypoxia for US/MRI-guided SDT (104). Mai’s hybrid nanovesicles combine US/MRI imaging with HIFU-triggered chemotherapy to prevent tumor recurrence (105). These multifunctional nanosystems collectively represent a paradigm shift in cancer management. They enable real-time treatment monitoring, precision image-guided therapy, and synergistic combination of multiple treatment modalities.

5 Discussion

The integration of nanotechnology with US has established a powerful theranostic platform that synergistically combines the inherent advantages of US, including its safe, deep tissue penetration capability, and real-time imaging features, with the multifunctional properties of NPs. This convergence enables highly targeted therapeutic interventions coupled with real-time treatment monitoring, fundamentally reshaping management strategies for breast and gynecologic cancers. Accumulating preclinical evidence demonstrates the superior efficacy of these US-triggered multimodal approaches over conventional monotherapies, primarily achieved through enhanced and synergistic tumor suppression mechanisms. Particularly noteworthy is the unique value proposition of NP-enhanced US technology, which integrates real-time operation, cost-effectiveness, absence of radiation exposure, and exceptional deep tissue penetration capacity. These combined characteristics render this technology especially suitable for treating deep seated gynecological tumors such as OC located within the pelvic cavity, presenting a compelling alternative to conventional diagnostic and therapeutic modalities.

US imaging has been extensively validated in diverse preclinical models, driving the development of numerous targeted contrast agents that have significantly advanced our understanding of disease mechanisms. However, the transition to clinical application requires improved standardization of these agents, particularly in manufacturing and characterization processes. While targeted MBs like BR55 remain the current clinical gold standard due to their established safety profile, most nanoscale contrast agents still await large scale clinical trials to demonstrate human applicability. The translation pathway faces additional challenges in funding allocation, as industrial support typically focuses on late stage clinical trials, creating significant financial barriers for academic research investigating novel molecular targets. This funding gap substantially hinders the bridging of preclinical discoveries to clinical applications and slows the overall progress of US molecular imaging translation.

Beyond these validation and standardization hurdles, several critical barriers impede the clinical translation of NP-enhanced US theranostics. A primary concern lies in the comprehensive biosafety and long term toxicity profile of engineered NPs. While many systems show favorable biocompatibility in acute settings, their long term fate, including potential immunogenicity, off-target accumulation, and the clearance pathways of nondegradable components, demands thorough investigation. Concurrently, the regulatory pathway for such complex theranostic agents remains arduous. Regulatory bodies like the FDA have well established protocols for drugs or devices separately, but combination products present unique hurdles. Defining critical quality attributes, ensuring manufacturing reproducibility at scale, and establishing standardized characterization methods for these multifunctional systems are significant obstacles that must be overcome.

Further technical and translational barriers persist. The targeting efficiency of NPs in heterogeneous human tumors needs enhancement beyond the often unreliable passive EPR effect. For therapies like SDT, translating efficacy from small animal models to human patients requires overcoming challenges in US energy delivery at greater tissue depths while sparing healthy structures. Moreover, the field currently lacks standardized protocols for US parameters across different NP systems, hindering comparative analysis and clinical optimization. The inherent complexity of these platforms also raises the question of cost-effectiveness and scalability, which will be crucial for widespread clinical adoption.

Looking forward, overcoming these hurdles necessitates a concerted, interdisciplinary effort. Future research must prioritize the rational design of next generation “smart” nanoplatforms that respond specifically to the tumor microenvironment for precision action. There is also a compelling need to explore novel therapeutic mechanisms, such as the induction of unconventional cell death pathways like ferroptosis, which may help overcome treatment resistance. Expanding the repertoire of combination therapies to include partnerships with immunotherapy or gene therapy represents another fertile ground for innovation. Ultimately, the goal is to leverage the rich diagnostic data provided by these systems to create truly personalized treatment protocols, tailoring both US parameters and NP dosing to individual patient needs.

In summary, while the path to clinical translation is paved with challenges in safety, regulatory compliance, and standardization, the potential of NP-enhanced US therapeutics to revolutionize cancer care is undeniable. Through ongoing collaboration across materials science, biology, clinical oncology, and regulatory science, the field can advance these sophisticated nanoplatforms from promising prototypes to practical clinical tools, ultimately paving the way for more effective, personalized, and less invasive treatments for breast and gynecologic cancers.

Statements

Author contributions

TY: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition. YL: Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by 2024 Scientific Research Cultivation Fund Project of Jinhua Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital JHFB-2024-2-06.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Shi J Kantoff PW Wooster R Farokhzad OC . Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. (2017) 17:20–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.108

2

Nayak V Singh KR Verma R Pandey MD Singh J Pratap Singh R . Recent advancements of biogenic iron nanoparticles in cancer theranostics. Mat Lett. (2022) 313:131769. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2022.131769

3

Zhou L-Q Li P Cui X-W Dietrich CF . Ultrasound nanotheranostics in fighting cancer: Advances and prospects. Cancer Lett. (2020) 470:204–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.034

4

Guo R Lu G Qin B Fei B . Ultrasound imaging technologies for breast cancer detection and management: A review. Ultrasound Med Biol. (2018) 44:37–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2017.09.012

5

Fischerova D Smet C Scovazzi U Sousa DN Hundarova K Haldorsen IS . Staging by imaging in gynecologic cancer and the role of ultrasound: an update of European joint consensus statements. Int J Gynecol Cancer. (2024) 34:363–78. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2023-004609

6

Zhang G Ye H-R Sun Y Guo Z-Z . Ultrasound molecular imaging and its applications in cancer diagnosis and therapy. ACS Sens. (2022) 7:2857–64. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.2c01468

7

Jain V Kumar H Anod HV Chand P Gupta NV Dey S et al . A review of nanotechnology-based approaches for breast cancer and triple-negative breast cancer. J Control Rel. (2020) 326:628–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.003

8

Sun Y-S Zhao Z Yang Z-N Xu F Lu H-J Zhu Z-Y et al . Risk factors and preventions of breast cancer. Int J Biol Sci. (2017) 13:1387–97. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.21635

9

Reinert T Barrios CH . Optimal management of hormone receptor positive metastatic breast cancer in 2016. Ther Adv Med Oncol. (2015) 7:304–20. doi: 10.1177/1758834015608993

10

He H Li F Tang R Wu N Zhou Y Cao Y et al . Ultrasound controllable release of proteolysis targeting chimeras for triple-negative breast cancer treatment. Biomater Res. (2024) 28:64. doi: 10.34133/bmr.0064

11

Berrada N Delaloge S André F . Treatment of triple-negative metastatic breast cancer: toward individualized targeted treatments or chemosensitization? Ann Oncol. (2010) 21. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq279

12

Nayak V Patra S Singh KR Ganguly B Kumar DN Panda D et al . Advancement in precision diagnosis and therapeutic for triple-negative breast cancer: Harnessing diagnostic potential of CRISPR-cas & engineered CAR T-cells mediated therapeutics. Environ Res. (2023) 235:116573. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2023.116573

13

Sung H Ferlay J Siegel RL Laversanne M Soerjomataram I Jemal A et al . Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

14

Jiang L Wang X . The miR-133b/brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein 1 (ARFGEF1) axis represses proliferation, invasion, and migration in cervical cancer cells. Bioengineered. (2022) 13:3323–32. doi: 10.1080/21655979.2022.2027063

15

de Sousa C Eksteen C Riedemann J Engelbrecht A-M . Highlighting the role of CD44 in cervical cancer progression: immunotherapy’s potential in inhibiting metastasis and chemoresistance. Immunol Res. (2024) 72:592–604. doi: 10.1007/s12026-024-09493-6

16

Kumar L Harish P Malik PS Khurana S . Chemotherapy and targeted therapy in the management of cervical cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. (2018) 42:120–8. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.01.016

17

Nussbaumer S Bonnabry P Veuthey J-L Fleury-Souverain S . Analysis of anticancer drugs: a review. Talanta. (2011) 85:2265–89. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2011.08.034

18

Zeien J Qiu W Triay M Dhaibar HA Cruz-Topete D Cornett EM et al . Clinical implications of chemotherapeutic agent organ toxicity on perioperative care. BioMed Pharmacother. (2022) 146:112503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112503

19

Xie W Xu Z . (Nano)biotechnological approaches in the treatment of cervical cancer: integration of engineering and biology. Front Immunol. (2024) 15:1461894. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2024.1461894

20

Kengsakul M Nieuwenhuyzen-de Boer GM Udomkarnjananun S Kerr SJ Niehot CD van Beekhuizen HJ . Factors predicting postoperative morbidity after cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gynecol Oncol. (2022) 33:e53. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2022.33.e53

21

Di Lorenzo G Ricci G Severini GM Romano F Biffi S . Imaging and therapy of ovarian cancer: clinical application of nanoparticles and future perspectives. Theranostics. (2018) 8:4279–94. doi: 10.7150/thno.26345

22

Di Donato V Kontopantelis E Aletti G Casorelli A Piacenti I Bogani G et al . Trends in mortality after primary cytoreductive surgery for ovarian cancer: A systematic review and metaregression of randomized clinical trials and observational studies. Ann Surg Oncol. (2017) 24:1688–97. doi: 10.1245/s10434-016-5680-7

23

Coleman RL Monk BJ Sood AK Herzog TJ . Latest research and treatment of advanced-stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2013) 10:211–24. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.5

24

Durno K Powell ME . The role of radiotherapy in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. (2022) 32:366–71. doi: 10.1136/ijgc-2021-002462

25

Lammers T Aime S Hennink WE Storm G Kiessling F . Theranostic nanomedicine. Acc Chem Res. (2011) 44:1029–38. doi: 10.1021/ar200019c

26

Lin X Liu S Zhang X Zhu R Chen S Chen X et al . An ultrasound activated vesicle of janus au-mnO nanoparticles for promoted tumor penetration and sono-chemodynamic therapy of orthotopic liver cancer. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. (2020) 59:1682–8. doi: 10.1002/anie.201912768

27

Gil B Anastasova S Yang G-Z . Low-powered implantable devices activated by ultrasonic energy transfer for physiological monitoring in soft tissue via functionalized electrochemical electrodes. Biosens Bioelectron. (2021) 182:113175. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113175

28

Lu GJ Farhadi A Szablowski JO Lee-Gosselin A Barnes SR Lakshmanan A et al . Acoustically modulated magnetic resonance imaging of gas-filled protein nanostructures. Nat Mater. (2018) 17:456–63. doi: 10.1038/s41563-018-0023-7

29

Pandit R Leinenga G Götz J . Repeated ultrasound treatment of tau transgenic mice clears neuronal tau by autophagy and improves behavioral functions. Theranostics. (2019) 9:3754–67. doi: 10.7150/thno.34388

30

Ayana G Ryu J Choe S-W . Ultrasound-responsive nanocarriers for breast cancer chemotherapy. Micromach (Basel). (2022) 13:1508. doi: 10.3390/mi13091508

31

Tong CWS Wu M Cho WCS To KKW . Recent advances in the treatment of breast cancer. Front Oncol. (2018) 8:227. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00227

32

Tharkar P Varanasi R Wong WSF Jin CT Chrzanowski W . Nano-enhanced drug delivery and therapeutic ultrasound for cancer treatment and beyond. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2019) 7:324. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00324

33

Unger EC Porter T Culp W Labell R Matsunaga T Zutshi R . Therapeutic applications of lipid-coated microbubbles. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. (2004) 56:1291–314. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.12.006

34

Greillier P Bawiec C Bessière F Lafon C . Therapeutic ultrasound for the heart: state of the art. IRBM. (2018) 39:227–35. doi: 10.1016/j.irbm.2017.11.004

35

Jin Q Kang S-T Chang Y-C Zheng H Yeh C-K . Inertial cavitation initiated by polytetrafluoroethylene nanoparticles under pulsed ultrasound stimulation. Ultrason Sonochem. (2016) 32:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2016.02.009

36

Han X Xu K Taratula O Farsad K . Applications of nanoparticles in biomedical imaging. Nanoscale. (2019) 11:799–819. doi: 10.1039/c8nr07769j

37

Oh I Min HS Li L Tran TH Lee Y Kwon IC et al . Cancer cell-specific photoactivity of pheophorbide a-glycol chitosan nanoparticles for photodynamic therapy in tumor-bearing mice. Biomaterials. (2013) 34:6454–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.017

38

Wen Q Wan S Liu Z Xu S Wang H Yang B . Ultrasound contrast agents and ultrasound molecular imaging. J Nanosci Nanotechnol. (2014) 14:190–209. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.9114

39

Güvener N Appold L de Lorenzi F Golombek SK Rizzo LY Lammers T et al . Recent advances in ultrasound-based diagnosis and therapy with micro- and nanometer-sized formulations. Methods. (2017) 130:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.05.018

40

Yang H Cai W Xu L Lv X Qiao Y Li P et al . Nanobubble-Affibody: Novel ultrasound contrast agents for targeted molecular ultrasound imaging of tumor. Biomaterials. (2015) 37:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.013

41

Jiang Q Hao S Xiao X Yao J Ou B Zhao Z et al . Production and characterization of a novel long-acting Herceptin-targeted nanobubble contrast agent specific for Her-2-positive breast cancers. Breast Cancer. (2016) 23:445–55. doi: 10.1007/s12282-014-0581-8

42

Gao Y Hernandez C Yuan H-X Lilly J Kota P Zhou H et al . Ultrasound molecular imaging of ovarian cancer with CA-125 targeted nanobubble contrast agents. Nanomedicine. (2017) 13:2159–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2017.06.001

43

Milgroom A Intrator M Madhavan K Mazzaro L Shandas R Liu B et al . Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a breast-cancer targeting ultrasound contrast agent. Colloids Surf B Biointerf. (2014) 116:652–7. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2013.10.038

44

Martinez HP Kono Y Blair SL Sandoval S Wang-Rodriguez J Mattrey RF et al . Hard shell gas-filled contrast enhancement particles for colour Doppler ultrasound imaging of tumors. Medchemcomm. (2010) 1:266–70. doi: 10.1039/c0md00139b

45

Baghbani F Chegeni M Moztarzadeh F Hadian-Ghazvini S Raz M . Novel ultrasound-responsive chitosan/perfluorohexane nanodroplets for image-guided smart delivery of an anticancer agent: Curcumin. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. (2017) 74:186–93. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.11.107

46

Lin X Zhang X Wang S Liang X Xu Y Chen M et al . Intraoperative identification and guidance of breast cancer microfoci using ultrasound and near-infrared fluorescence dual-modality imaging. ACS Appl Bio Mater. (2019) 2:2252–61. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00206

47

Bai J-W Qiu S-Q Zhang G-J . Molecular and functional imaging in cancer-targeted therapy: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. (2023) 8:89. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01366-y

48

Yin C Hu P Qin L Wang Z Zhao H . The current status and future directions on nanoparticles for tumor molecular imaging. Int J Nanomed. (2024) 19:9549–74. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S484206

49

Dai T Wang Q Zhu L Luo Q Yang J Meng X et al . Combined UTMD-nanoplatform for the effective delivery of drugs to treat renal cell carcinoma. Int J Nanomed. (2024) 19:8519–40. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S459960

50

Perlman O Weitz IS Azhari H . Copper oxide nanoparticles as contrast agents for MRI and ultrasound dual-modality imaging. Phys Med Biol. (2015) 60:5767–83. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/60/15/5767

51

Nie Z Luo N Liu J Zeng X Zhang Y Su D . Multi-mode biodegradable tumour-microenvironment sensitive nanoparticles for targeted breast cancer imaging. Nanoscale Res Lett. (2020) 15:81. doi: 10.1186/s11671-020-03309-w

52

Das D Sharma A Rajendran P Pramanik M . Another decade of photoacoustic imaging. Phys Med Biol. (2021) 66. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/abd669

53

Attia ABE Balasundaram G Moothanchery M Dinish US Bi R Ntziachristos V et al . A review of clinical photoacoustic imaging: Current and future trends. Photoacoustics. (2019) 16:100144. doi: 10.1016/j.pacs.2019.100144

54

Liu Y Chen S Sun J Zhu S Chen C Xie W et al . Folate-targeted and oxygen/indocyanine green-loaded lipid nanoparticles for dual-mode imaging and photo-sonodynamic/photothermal therapy of ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo. Mol Pharm. (2019) 16:4104–20. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00339

55

Hallez L Touyeras F Hihn J-Y Bailly Y . Characterization of HIFU transducers designed for sonochemistry application: Acoustic streaming. Ultrason Sonochem. (2016) 29:420–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2015.10.019

56

Trendowski M Wong V Zoino JN Christen TD Gadeberg L Sansky M et al . Preferential enlargement of leukemia cells using cytoskeletal-directed agents and cell cycle growth control parameters to induce sensitivity to low frequency ultrasound. Cancer Lett. (2015) 360:160–70. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.02.001

57

Zhu L Torchilin VP . Stimulus-responsive nanopreparations for tumor targeting. Integr Biol (Camb). (2013) 5:96–107. doi: 10.1039/c2ib20135f

58

Torchilin VP . Targeted pharmaceutical nanocarriers for cancer therapy and imaging. AAPS J. (2007) 9:E128–147. doi: 10.1208/aapsj0902015

59

Moon GD Choi S-W Cai X Li W Cho EC Jeong U et al . A new theranostic system based on gold nanocages and phase-change materials with unique features for photoacoustic imaging and controlled release. J Am Chem Soc. (2011) 133:4762–5. doi: 10.1021/ja200894u

60

Huang P Qian X Chen Y Yu L Lin H Wang L et al . Metalloporphyrin-encapsulated biodegradable nanosystems for highly efficient magnetic resonance imaging-guided sonodynamic cancer therapy. J Am Chem Soc. (2017) 139:1275–84. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11846

61

Wang J Liu L You Q Song Y Sun Q Wang Y et al . All-in-one theranostic nanoplatform based on hollow moSx for photothermally-maneuvered oxygen self-enriched photodynamic therapy. Theranostics. (2018) 8:955–71. doi: 10.7150/thno.22325

62

Pitt WG Husseini GA Staples BJ . Ultrasonic drug delivery–a general review. Expert Opin Drug Delivery. (2004) 1:37–56. doi: 10.1517/17425247.1.1.37

63

Baghbani F Moztarzadeh F Mohandesi JA Yazdian F Mokhtari-Dizaji M . Novel alginate-stabilized doxorubicin-loaded nanodroplets for ultrasounic theranosis of breast cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. (2016) 93:512–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.09.008

64

Sheng D Deng L Li P Wang Z Zhang Q . Perfluorocarbon nanodroplets with deep tumor penetration and controlled drug delivery for ultrasound/fluorescence imaging guided breast cancer therapy. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. (2021) 7:605–16. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.0c01333

65

Suzuki R Namai E Oda Y Nishiie N Otake S Koshima R et al . Cancer gene therapy by IL-12 gene delivery using liposomal bubbles and tumoral ultrasound exposure. J Control Rel. (2010) 142:245–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.10.027

66

Adeyemi SA Az-Zamakhshariy Z Choonara YE . In vitro prototyping of a nano-organogel for thermo-sonic intra-cervical delivery of 5-fluorouracil-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles for cervical cancer. AAPS PharmSciTech. (2023) 24:123. doi: 10.1208/s12249-023-02583-y

67

Radha R Paul V Anjum S Bouakaz A Pitt WG Husseini GA . Enhancing Curcumin’s therapeutic potential in cancer treatment through ultrasound mediated liposomal delivery. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:10499. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-61278-x

68

Elamir A Ajith S Sawaftah NA Abuwatfa W Mukhopadhyay D Paul V et al . Ultrasound-triggered herceptin liposomes for breast cancer therapy. Sci Rep. (2021) 11:7545. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86860-5

69

Haar GT Coussios C . High intensity focused ultrasound: past, present and future. Int J Hyperther. (2007) 23:85–7. doi: 10.1080/02656730601185924

70

Sun S Wang P Sun S Liang X . Applications of micro/nanotechnology in ultrasound-based drug delivery and therapy for tumor. Curr Med Chem. (2021) 28:525–47. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200212100257

71

Yildirim A Chattaraj R Blum NT Shi D Kumar K Goodwin AP . Phospholipid capped mesoporous nanoparticles for targeted high intensity focused ultrasound ablation. Adv Healthc Mater. (2017) 6. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700514

72

Qian X Han X Chen Y . Insights into the unique functionality of inorganic micro/nanoparticles for versatile ultrasound theranostics. Biomaterials. (2017) 142:13–30. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.07.016

73

Sun Y Zheng Y Ran H Zhou Y Shen H Chen Y et al . Superparamagnetic PLGA-iron oxide microcapsules for dual-modality US/MR imaging and high intensity focused US breast cancer ablation. Biomaterials. (2012) 33:5854–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.062

74

Feng G Hao L Xu C Ran H Zheng Y Li P et al . High-intensity focused ultrasound-triggered nanoscale bubble-generating liposomes for efficient and safe tumor ablation under photoacoustic imaging monitoring. Int J Nanomed. (2017) 12:4647–59. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S135391

75

Liu T Zhang N Wang Z Wu M Chen Y Ma M et al . Endogenous catalytic generation of O2 bubbles for in situ ultrasound-guided high intensity focused ultrasound ablation. ACS Nano. (2017) 11:9093–102. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b03772

76

Lin X Song J Chen X Yang H . Ultrasound-activated sensitizers and applications. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. (2020) 59:14212–33. doi: 10.1002/anie.201906823

77

Sang W Zhang Z Dai Y Chen X . Recent advances in nanomaterial-based synergistic combination cancer immunotherapy. Chem Soc Rev. (2019) 48:3771–810. doi: 10.1039/c8cs00896e

78

Liang S Deng X Ma P Cheng Z Lin J . Recent advances in nanomaterial-assisted combinational sonodynamic cancer therapy. Adv Mater. (2020) 32:e2003214. doi: 10.1002/adma.202003214

79

Qian X Zheng Y Chen Y . Micro/nanoparticle-augmented sonodynamic therapy (SDT): breaking the depth shallow of photoactivation. Adv Mater. (2016) 28:8097–129. doi: 10.1002/adma.201602012

80

Zhou Y Cao Z Jiang L Chen Y Cui X Wu J et al . Magnetically actuated sonodynamic nanorobot collectives for potentiated ovarian cancer therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2024) 12:1374423. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2024.1374423

81

Chen Y-W Liu T-Y Chang P-H Hsu P-H Liu H-L Lin H-C et al . A theranostic nrGO@MSN-ION nanocarrier developed to enhance the combination effect of sonodynamic therapy and ultrasound hyperthermia for treating tumor. Nanoscale. (2016) 8:12648–57. doi: 10.1039/c5nr07782f

82

Xu Q Zhan G Zhang Z Yong T Yang X Gan L . Manganese porphyrin-based metal-organic framework for synergistic sonodynamic therapy and ferroptosis in hypoxic tumors. Theranostics. (2021) 11:1937–52. doi: 10.7150/thno.45511

83

Malekmohammadi S Hadadzadeh H Rezakhani S Amirghofran Z . Design and synthesis of gatekeeper coated dendritic silica/titania mesoporous nanoparticles with sustained and controlled drug release properties for targeted synergetic chemo-sonodynamic therapy. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. (2019) 5:4405–15. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.9b00237

84

Wang Y Lv B Wang H Ren T Jiang Q Qu X et al . Ultrasound-triggered azo free radicals for cervical cancer immunotherapy. ACS Nano. (2024) 18:11042–57. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c10625

85

Kang HJ Truong Hoang Q Min J Son MS Tram LTH Kim BC et al . Efficient combination chemo-sonodynamic cancer therapy using mitochondria-targeting sonosensitizer-loaded polysorbate-based micelles. Int J Mol Sci. (2024) 25:3474. doi: 10.3390/ijms25063474

86

Zhu L Chen G Wang Q Du J Wu S Lu J et al . High-Z elements dominated bismuth-based heterojunction nano-semiconductor for radiotherapy-enhanced sonodynamic breast cancer therapy. J Colloid Interface Sci. (2024) 662:914–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2024.02.069

87

Li G Guo Y Ni C Wang Z Zhan M Sun H et al . A functionalized cell membrane biomimetic nanoformulation based on layered double hydroxide for combined tumor chemotherapy and sonodynamic therapy. J Mater Chem B. (2024) 12:7429–39. doi: 10.1039/d4tb00813h

88

Shi Z Zeng Y Luo J Wang X Ma G Zhang T et al . Endogenous magnetic lipid droplet-mediated cascade-targeted sonodynamic therapy as an approach to reversing breast cancer multidrug resistance. ACS Nano. (2024) 18:28659–74. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.4c05938

89

Wang X Wang H Li Y Sun Z Liu J Sun C et al . Engineering macrophage membrane-camouflaged nanoplatforms with enhanced macrophage function for mediating sonodynamic therapy of ovarian cancer. Nanoscale. (2024) 16:19048–61. doi: 10.1039/d4nr01307g

90

Rojas JD Lin F Chiang Y-C Chytil A Chong DC Bautch VL et al . Ultrasound molecular imaging of VEGFR-2 in clear-cell renal cell carcinoma tracks disease response to antiangiogenic and notch-inhibition therapy. Theranostics. (2018) 8:141–55. doi: 10.7150/thno.19658

91

Ho Y-J Huang C-C Fan C-H Liu H-L Yeh C-K . Ultrasonic technologies in imaging and drug delivery. Cell Mol Life Sci. (2021) 78:6119–41. doi: 10.1007/s00018-021-03904-9

92

Li D Lin L Fan Y Liu L Shen M Wu R et al . Ultrasound-enhanced fluorescence imaging and chemotherapy of multidrug-resistant tumors using multifunctional dendrimer/carbon dot nanohybrids. Bioact Mater. (2021) 6:729–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.09.015

93

Liufu C Li Y Lin Y Yu J Du M Chen Y et al . Synergistic ultrasonic biophysical effect-responsive nanoparticles for enhanced gene delivery to ovarian cancer stem cells. Drug Delivery. (2020) 27:1018–33. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2020.1785583

94

Zhao R Liang X Zhao B Chen M Liu R Sun S et al . Ultrasound assisted gene and photodynamic synergistic therapy with multifunctional FOXA1-siRNA loaded porphyrin microbubbles for enhancing therapeutic efficacy for breast cancer. Biomaterials. (2018) 173:58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.04.054

95

Sun S Xu Y Fu P Chen M Sun S Zhao R et al . Ultrasound-targeted photodynamic and gene dual therapy for effectively inhibiting triple negative breast cancer by cationic porphyrin lipid microbubbles loaded with HIF1α-siRNA. Nanoscale. (2018) 10:19945–56. doi: 10.1039/c8nr03074j

96

Bai M Shen M Teng Y Sun Y Li F Zhang X et al . Enhanced therapeutic effect of Adriamycin on multidrug resistant breast cancer by the ABCG2-siRNA loaded polymeric nanoparticles assisted with ultrasound. Oncotarget. (2015) 6:43779–90. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6085

97

Chen S Liu Y Zhu S Chen C Xie W Xiao L et al . Dual-mode imaging and therapeutic effects of drug-loaded phase-transition nanoparticles combined with near-infrared laser and low-intensity ultrasound on ovarian cancer. Drug Delivery. (2018) 25:1683–93. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2018.1507062

98

Mou C Yang Y Bai Y Yuan P Wang Y Zhang L . Hyaluronic acid and polydopamine functionalized phase change nanoparticles for ultrasound imaging-guided photothermal-chemotherapy. J Mater Chem B. (2019) 7:1246–57. doi: 10.1039/c8tb03056a

99

Chen Q Xiao H Hu L Huang Y Cao Z Shuai X et al . 19F MRI/CEUS dual imaging-guided sonodynamic therapy enhances immune checkpoint blockade in triple-negative breast cancer. Adv Sci (Weinh). (2024) 11:e2401182. doi: 10.1002/advs.202401182

100

He Y Wang M Fu M Yuan X Luo Y Qiao B et al . Iron(II) phthalocyanine loaded and AS1411 aptamer targeting nanoparticles: A nanocomplex for dual modal imaging and photothermal therapy of breast cancer. Int J Nanomed. (2020) 15:5927–49. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S254108

101

Zhao X-Z Zhang W Cao Y Huang S-S Li Y-Z Guo D et al . A cleverly designed novel lipid nanosystem: targeted retention, controlled visual drug release, and cascade amplification therapy for mammary carcinoma. vitro. Int J Nanomed. (2020) 15:3953–64. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S244743

102

Dong Q Yang H Wan C Zheng D Zhou Z Xie S et al . Her2-functionalized gold-nanoshelled magnetic hybrid nanoparticles: a theranostic agent for dual-modal imaging and photothermal therapy of breast cancer. Nanoscale Res Lett. (2019) 14:235. doi: 10.1186/s11671-019-3053-4

103

Gong J Song C Li G Guo Y Wang Z Guo H et al . Ultrasound-enhanced theranostics of orthotopic breast cancer through a multifunctional core-shell tecto dendrimer-based nanomedicine platform. Biomater Sci. (2023) 11:4385–96. doi: 10.1039/d3bm00375b

104

Xie M Duan T Wan Y Zhang X Shi J Zhao M et al . Ultrasound and glutathione dual-responsive biomimetic nanoplatform for ultrasound/magnetic resonance imaging and sonodynamic therapy of ovarian cancer. J Colloid Interface Sci. (2024) 682:311–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2024.11.221

105

Mai X Chang Y You Y He L Chen T . Designing intelligent nano-bomb with on-demand site-specific drug burst release to synergize with high-intensity focused ultrasound cancer ablation. J Control Rel. (2021) 331:270–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.09.051

Summary

Keywords

ultrasound imaging, ultrasound therapy, nanoparticles, theranostics, gynecologic oncology

Citation

Yang T, Lou Y and Ying Z (2025) Nanoparticle-ultrasound synergy: an emerging theranostic paradigm for breast and gynecologic cancers. Front. Oncol. 15:1617939. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1617939

Received

25 April 2025

Revised

20 November 2025

Accepted

21 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Giovanna Rassu, University of Sassari, Italy

Reviewed by

Kshitij Rb Singh, Kyushu Institute of Technology, Japan

Abu Md Ashif Ikbal, Assam University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Yang, Lou and Ying.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yelin Lou, snowflack100@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.