- 1Day Chemotherapy Center, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

- 2Department of Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Nanning, China

- 3Department of Thoracic Surgery, Nanxishan Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (The Second People's Hospital of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Guilin, China

Objective: Sleep disorders are prevalent among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and are influenced by multiple psychological, social, and physiological factors. This study aims to explore the determinants of sleep disturbances in this population using a structural equation model (SEM), focusing on the role of social support, psychological distress, coping strategies, and pain.

Methods: A cross-sectional study was conducted with 383 breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy from the Department of Oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Guangxi, China, from May 2023 to June 2024. The survey questionnaire contained a general data questionnaire and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ), Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to examine direct and indirect pathways affecting sleep quality. Model fit was assessed using CMIN/DF, RMSEA, GFI, AGFI, NFI, TLI, and CFI.

Results: The SEM demonstrated good model fit (CMIN/DF = 2.061, RMSEA = 0.053, CFI = 0.959). Social support negatively correlated with psychological distress (β = -0.158, P = 0.013) and positively influenced sleep quality (β = -0.122, P = 0.028). Psychological distress (β = 0.567, P < 0.001) and pain (β = 0.191, P < 0.001) had significant negative effects on sleep quality. Mediation analysis confirmed that psychological distress significantly mediated the effects of social support and pain on sleep quality.

Conclusions: Social support and psychological distress are key determinants of sleep quality in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Psychological distress mediates the relationship between pain, social support, and sleep disturbances, emphasizing the need for psychosocial interventions to improve sleep quality in this population.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most prevalent malignant tumor among women worldwide (1), with chemotherapy serving as a cornerstone treatment to improve survival rates (2). However, chemotherapy is often accompanied by a range of adverse effects, including pain, fatigue, and psychological distress, all of which contribute to high rates of sleep disturbances in this population (3). Studies indicate that up to 65% of breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy experience significant sleep disturbances, including difficulty initiating sleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, and reduced sleep efficiency (4). Poor sleep quality not only exacerbates cancer-related symptoms but also increases treatment-related toxicity, compromises quality of life, and may even elevate the risk of recurrence or mortality (5). Despite the high prevalence of sleep disorders among breast cancer patients, the underlying mechanisms remain inadequately studied, particularly the complex interactions between psychological status, social support, pain, and coping strategies. A deeper understanding of these factors is crucial to developing targeted interventions aimed at improving sleep quality in this vulnerable population.

The biopsychosocial model provides a robust theoretical framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of sleep disturbances in breast cancer patients (6, 7). Within this model, psychological distress has been widely recognized as a key determinant of sleep disorders (8). Chronic stress and heightened nervous system arousal prolong sleep latency, increase nocturnal awakenings, and reduce deep sleep stages. Moreover, pain—a common symptom among chemotherapy patients—has been shown to disrupt sleep architecture, increasing wakefulness and reducing sleep quality (9). Beyond physiological factors, social support plays a crucial role in mitigating psychological distress and enhancing sleep quality (10). Studies suggest that strong social support networks are associated with lower anxiety and depression levels, which in turn improve sleep outcomes (11). Additionally, coping strategies significantly influence how patients manage psychological distress, further impacting sleep quality (12). Positive coping strategies, such as cognitive restructuring and problem-solving, have been linked to better psychological resilience and improved sleep, while maladaptive coping styles, such as avoidance and emotional suppression, may worsen sleep disturbances. However, the interactions among these variables in breast cancer patients remain unclear.

Given the complexity of these relationships, this study employs structural equation modeling (SEM) to simultaneously assess the direct and indirect pathways between social support, psychological status, coping strategies, pain, and sleep quality in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. SEM allows for a more comprehensive analysis of the interconnections between these factors, enabling the identification of key mediators and moderators. By constructing and validating an SEM-based model, this research aims to provide empirical evidence for targeted psychosocial and pain management interventions that can enhance sleep quality and overall well-being in breast cancer patients. The findings of this study will contribute to the development of evidence-based interventions to improve the quality of life for this high-risk population.

Methods

Formulation of research hypotheses

Theoretical framework and research hypotheses

This study is based on the Biopsychosocial Model as the theoretical foundation for understanding the influencing factors of sleep disorders in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. The model integrates biological (pain), psychological (anxiety and depression), behavioral (coping strategies), and social (social support) factors to provide a comprehensive explanation of sleep disturbances in this population. Sleep disorders are often associated with complex interactions between these factors, making a multidimensional approach essential.

Based on this framework, the study formulated the following hypotheses (Table 1).

To test these hypotheses, SEM was employed, which allows the simultaneous analysis of multiple interrelated pathways. Finally, a sleep disorder analysis model for breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy was constructed (Figure 1).

Sample selection

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Department of Oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, Guangxi, China, from May 2023 to June 2024. Sample inclusion criteria: (1) patients who undergoing chemotherapy and had been diagnosed breast cancer; (2) age ≥ 18; (3) No severe cardiovascular, hepatic, renal dysfunction, or other major diseases; (4) No severe psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairments, capable of understanding and following intervention requirements. (5) patients who gave informed consent and voluntarily participated in the study. Exclusion criteria: (1) patients with severe audio-visual impairment and an inability to communicate; (2) patients in poor condition who had difficulties completing the survey questionnaire.

Sample size calculation

The sample size required for this study was determined using an online Sample Size Calculator for SEM, available at https://wnarifin.ocpu.io/sscalc/www/ssrmsea.html. The calculation was based on the Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) method, which is widely used for estimating sample size requirements in SEM studies (13). The parameters were set for the calculation: Expected RMSEA = 0.05, df=77, α=0.05, 1-β=90%, Expected dropout rate=20%. Based on these inputs, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 231 participants. Considering a 20% dropout rate, the final recommended sample size for recruitment was 289 participants. However, to enhance the robustness and reliability of the study findings, a total of 383 patients were ultimately included in the final analysis, exceeding the estimated requirement to account for potential missing data and ensure adequate statistical power.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (Approval No. Z-A20230453). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection, and all procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Survey instruments

In order to ensure the scientific validity of the study and the good reliability of the questionnaire, all the measurement items in this study were referred to existing, well-established scales and adapted to the context of this study. The survey covered five areas: sleep quality, social support, psychological status, coping style, and pain.

Sleep quality

The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), developed by Buysse et al. in 1989 (14). It is a self-rated questionnaire which assesses sleep quality and disturbances over 1 month time interval. Nineteen individual items generate seven “component” scores: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction. The sum of scores for these seven components yields one global score. Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality. A global PSQI score greater than 5 yielded a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% in distinguishing good and poor sleepers. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84.

Psychological status

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Developed by Zigmond and Snaith, 1983 (15). It is a self-rated instrument for anxiety and depression symptoms in the past week. It has seven items for anxiety and seven items for depression (14 total items, with each score ranging from 0 to 3) and has been widely used for people with cancer (16). The scores for these seven items are then added for a single total score with a range of 0–21 for HADS anxiety and HADS depression. HADS has demonstrated good reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.68 to 0.93 (17).

Social support

The Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS), developed by Xiao Shuiyuan according to China’s national conditions with good reliability and validity (18). It includes 10 items in three dimensions: subjective support, objective support and support availability. The sum of the scores of 10 items is the total score. Higher scores indicate stronger support networks.

Coping style

The Simplified Coping Style Questionnaire (SCSQ), developed by Xie (19). It is a 20-question self-report scale divided into two dimensions: positive coping style and negative coping style. It is used to assess a person’s coping style when dealing with things. These questions are rated on a scale from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The total score of SCSQ is the positive dimension standard score minus the negative dimension standard score. The higher the score, the more likely the individual is to use positive coping styles. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.9.

Pain

The Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) (20), is an 11-point scale comprising a number from 0 through 10; 0 indicates “no pain”, and 10 indicates the “worst imaginable pain”, with higher scores indicating more severe pain. Patients are instructed to choose a single number from the scale that best indicates their level of pain.

Data acquisition

This study applied an electronic questionnaire and paper questionnaires to complete data collection by a person on a one-to-one basis. Prior to the start of the survey, all questionnaire entries and survey technical details were discussed in detail by the four investigators to ensure consistency in the research process. Accompanied by the medical and nursing staff of the department, a professionally trained investigator introduces the purpose and content of the survey to the patients, seeks their informed consent, and then invites them to participate in this survey. The survey was limited to 10–20 min per respondent.

Data collection

A questionnaire survey was conducted on patients who were able to cooperate with the study, and information was collected and evaluated when the patients were admitted to the hospital for chemotherapy. The collected information included the patients’ general information, disease-related information, and the patients’ sleep conditions, coping styles, social support, and anxiety and depression were assessed.

Quality control

Investigators received training to ensure data consistency. The training content included research objectives, questionnaire filling requirements, and evaluation methods for each scale. Trained investigators stated point by point and completed the questionnaire based on the patient’s answers. The questionnaires were distributed and collected on site to check for omissions, verification, and recall. The data were recorded by two researchers, and questionnaires with errors or omissions exceeding 20% or completely similar were eliminated.

Statistical methods

All data were entered using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 25.0 software. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages N (%), while continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations (Mean ± SD). Independent samples t-tests and one-way ANOVA were conducted to compare sleep quality scores across different groups. Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore bivariate relationships between key variables, including sleep quality, psychological distress, social support, pain, and coping strategies. P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SEM was employed to test the hypothesized relationships among social support, coping strategies, psychological distress, pain, and sleep quality. Model fit was assessed using multiple goodness-of-fit indices following established SEM guidelines. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF) was used as an overall measure of model fit, with values < 3.0 indicating acceptable fit. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) evaluates approximate fit; values ≤ 0.08 indicate acceptable fit, and values ≤ 0.05 indicate good fit. The goodness-of-fit index (GFI) and adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) assess absolute model fit, with recommended thresholds of ≥ 0.90. Incremental fit was evaluated using the normed fit index (NFI), Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), and comparative fit index (CFI), for which values ≥ 0.90 indicate acceptable fit and values ≥ 0.95 indicate excellent fit. These criteria align with widely accepted recommendations for SEM model evaluation (21, 22). The model was iteratively modified based on modification indices and theoretical considerations to achieve the best fit. Mediation effects were tested using bias-corrected bootstrapping with 2000 samples to estimate indirect effects and 95% confidence intervals. P-value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Results

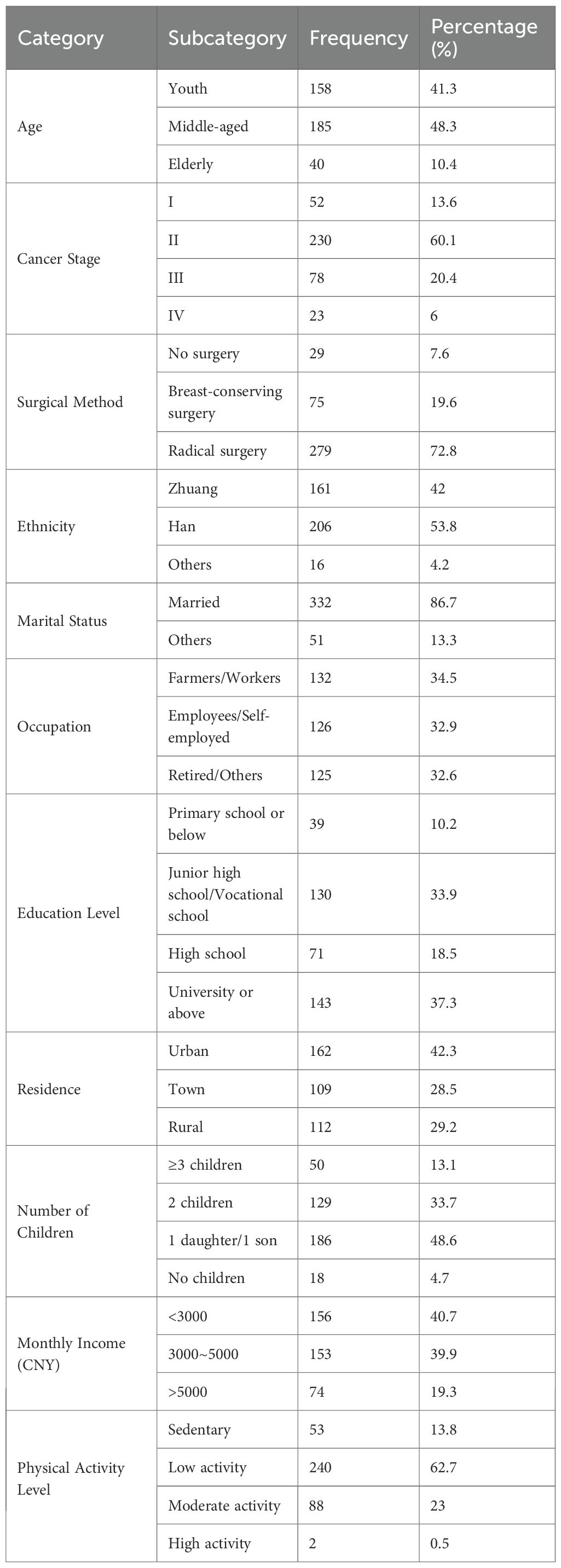

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

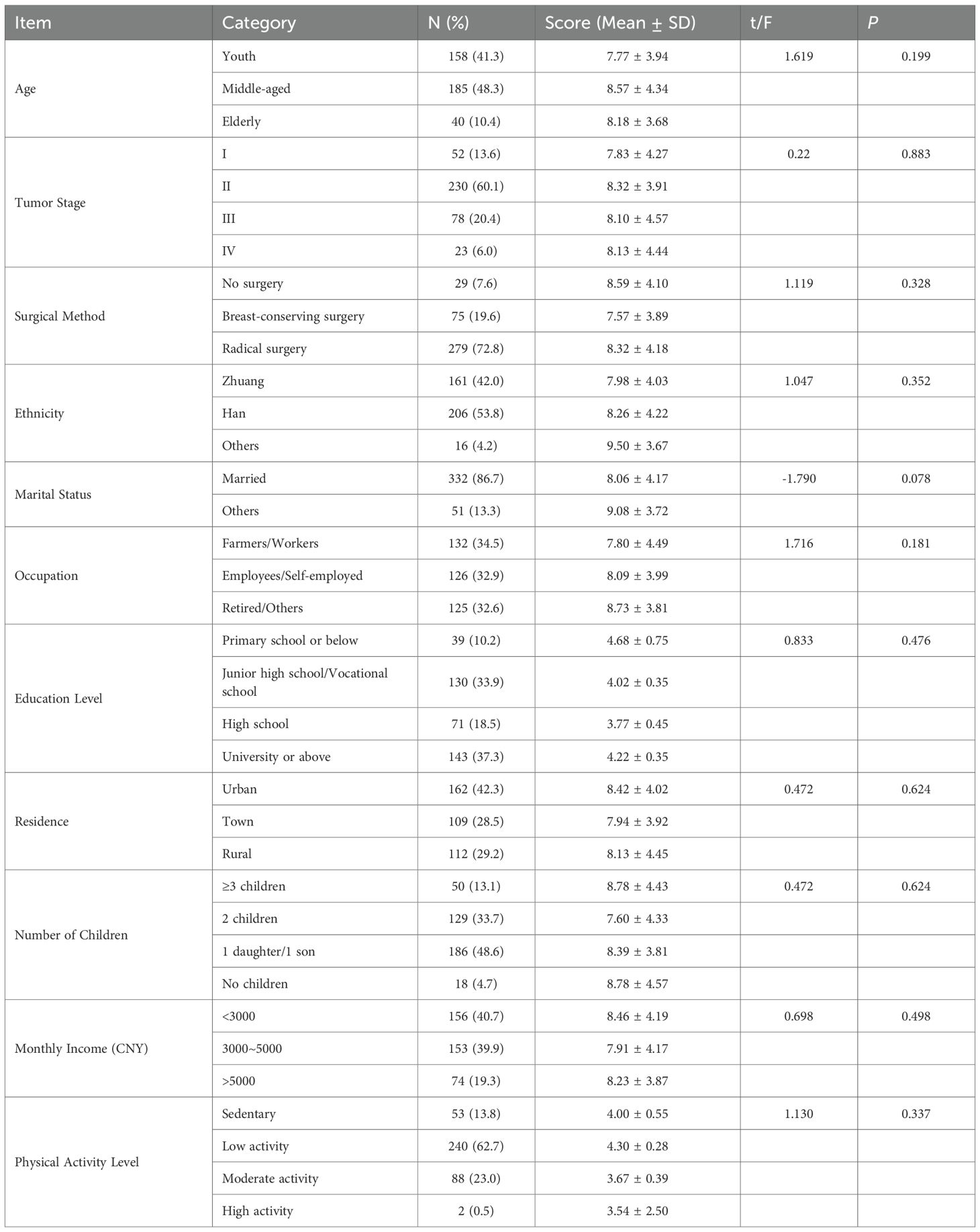

A total of 383 breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy were enrolled in this study. The majority were middle-aged (48.3%) and married (86.7%), with most diagnosed at stage II of breast cancer (60.1%). Radical surgery was the most frequently adopted treatment (72.8%). In terms of ethnicity, Han and Zhuang populations predominated. Nearly half of the participants (48.6%) had two children, and a significant proportion resided in urban areas (42.3%). Regarding education and income, 37.3% of participants held a university degree or higher, while 40.7% reported a monthly income below CNY 3, 000. Physical activity levels were generally low, with 62.7% engaging in minimal physical activity and only 0.5% reporting high levels of exercise. These findings reflect considerable sociodemographic and clinical diversity across the sample, which provides a comprehensive foundation for subsequent structural equation modeling analysis (Table 2).

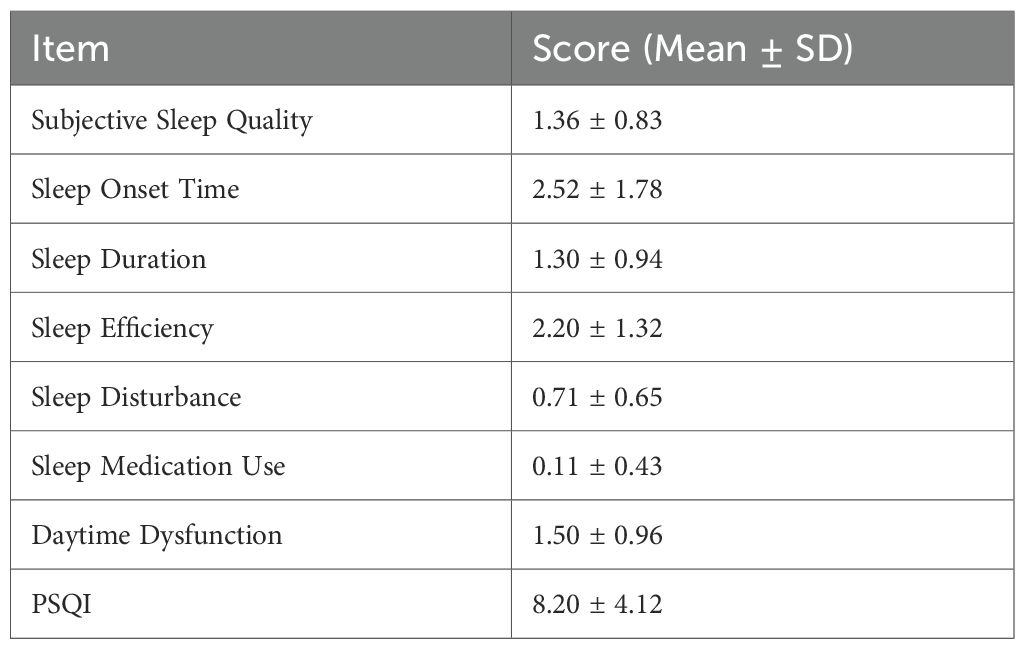

Sleep quality scores of breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy

The overall PSQI score among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy was 8.20 ± 4.12, indicating generally poor sleep quality. Among the subcomponents, sleep onset time had the highest mean score, reflecting difficulties in falling asleep, followed by reduced sleep efficiency. In contrast, the use of sleep medication had the lowest mean score. These data present a detailed profile of sleep disturbances in this population (Table 3).

Comparison of sleep conditions in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with different characteristics

An analysis of sleep scores among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy revealed no statistically significant differences across demographic and clinical variables (P > 0.05). Sleep quality did not significantly vary by age, cancer stage, surgical method, ethnicity, marital status, occupation, education level, residence, number of children, income level, or physical activity level. While some subgroups, such as retired individuals or those without children, had numerically higher PSQI scores, these differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

Table 4. Comparison of sleep score in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy with different characteristics.

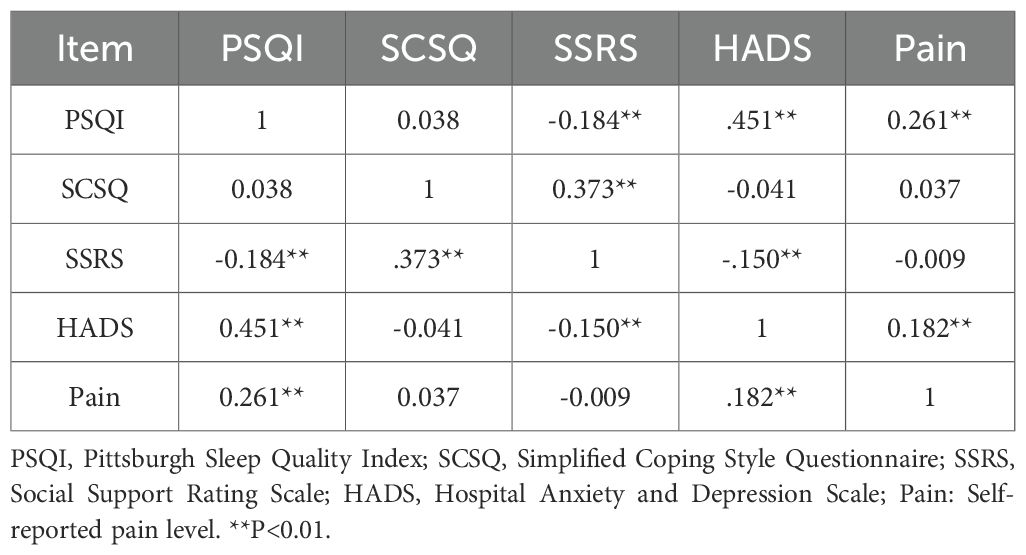

Correlation analysis

As shown in Table 5, sleep quality was significantly correlated with several key psychological and physical factors. PSQI scores were positively associated with psychological distress (r = 0.451, P < 0.01) and pain levels (r = 0.261, P < 0.01), suggesting that greater anxiety, depression, and pain were linked to poorer sleep quality. In contrast, social support (SSRS) demonstrated a negative correlation with PSQI (r = –0.184, P < 0.01), indicating a protective role of support networks in sleep. Additionally, HADS was significantly related to both pain (r = 0.182, P < 0.01) and SSRS (r = –0.150, P < 0.01), further reinforcing the interconnectedness of psychological and social variables. Notably, coping strategies (SCSQ) were not significantly correlated with sleep quality (r = 0.038, P > 0.05).

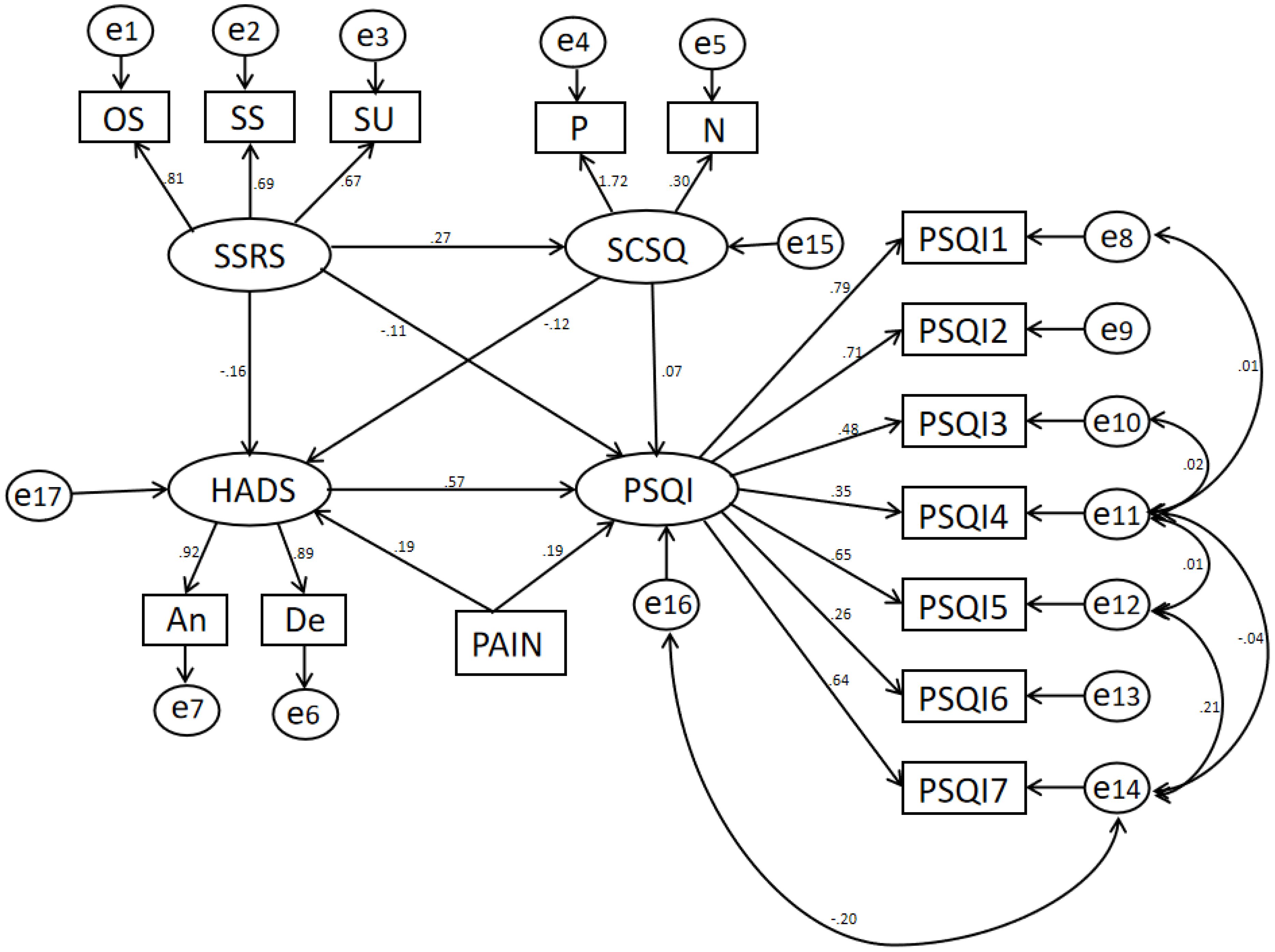

Model construction of influencing factors of sleep disorders in breast cancer chemotherapy patients

The SEM analysis revealed the interrelationships among social support, psychological status, coping strategies, pain, and sleep quality in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy (Figure 2). Social support (SSRS) was negatively associated with psychological distress (HADS), indicating that higher levels of social support correlated with lower anxiety and depression. Additionally, psychological distress exhibited a significant positive association with sleep disturbances, suggesting that increased anxiety and depression negatively impacted sleep quality. Pain was found to exert both direct and indirect effects on sleep quality (PSQI). The direct pathway indicated that higher pain levels were associated with poorer sleep quality, while the indirect effect, mediated through psychological distress, reinforced this relationship. Coping strategies (SCSQ) were incorporated into the model to assess their moderating role. However, the influence of coping strategies on sleep quality did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that coping mechanisms might not independently affect sleep outcomes in this patient population. These findings underscore the critical role of psychological distress and pain in determining sleep quality among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Note: The SEM analyzing the factors influencing sleep quality (PSQI) in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. The model includes several latent variables: social support (SSRS), coping style (SCSQ), hospital anxiety and depression (HADS), and pain, with their corresponding observed indicators. SSRS (Social Support) is influenced by three observed variables: OS (Objective Support), SS (Subjective Support), and SU (Support Utilization).SCSQ (coping style) is influenced by positive (P) and negative (N) components. HADS (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) is determined by Anxiety (An) and Depression (De). The measurement model includes PSQI subcomponents (PSQI1 to PSQI7) as observed variables linked to PSQI, illustrating how sleep quality is assessed.

Model fit results

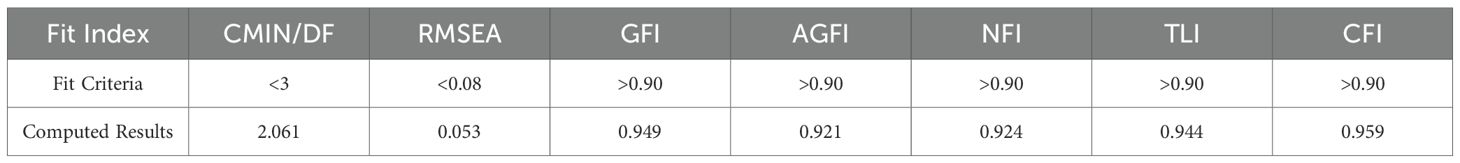

The structural equation model demonstrated acceptable fit. The CMIN/DF was 2.061, within the recommended threshold of <3. The RMSEA was 0.053, indicating a good fit (<0.08). Fit indices including GFI (0.949), AGFI (0.921), NFI (0.924), TLI (0.944), and CFI (0.959) all exceeded the standard cutoff of 0.90, indicating satisfactory model performance (Table 6).

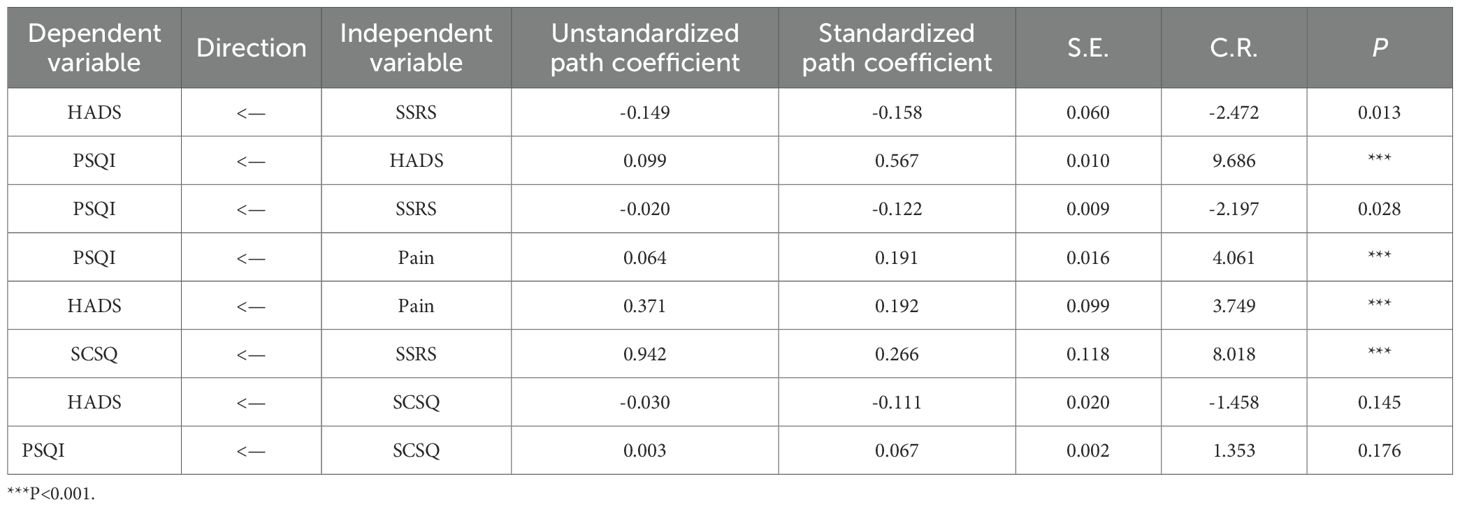

Results of path analysis

The structural equation modeling analysis provided empirical support for several of the proposed hypotheses (Table 7). H1 was supported, as social support (SSRS) was negatively associated with psychological distress (HADS) (β = -0.158, P = 0.013), indicating that patients with higher social support experienced lower levels of anxiety and depression. H2 was also confirmed, with psychological distress showing a strong positive association with sleep disturbance (PSQI) (β = 0.567, P < 0.001), suggesting that increased psychological distress contributed to poorer sleep quality. H3, proposing that social support indirectly improves sleep quality through its effect on psychological distress, was partially supported: social support showed a direct negative effect on PSQI (β = -0.122, P = 0.028) and an indirect pathway via HADS. H4 was validated, as pain had both a direct positive effect on sleep disturbance (β = 0.191, P < 0.001) and an indirect effect mediated by its significant positive influence on psychological distress (β = 0.192, P < 0.001). In contrast, H5, which hypothesized that coping strategies (SCSQ) mediate the relationship between social support and psychological distress, was not supported. Although social support positively predicted coping strategies (β = 0.266, P < 0.001), coping strategies did not significantly affect psychological distress (β = -0.111, P = 0.145). Similarly, H6 was not supported, as coping strategies showed no significant direct effect on sleep quality (β = 0.067, P = 0.176).

These findings indicate that while social support and pain influence sleep quality both directly and indirectly via psychological distress, coping strategies did not have a statistically significant role in the pathway model.

Mediation effect test

The mediation analysis further confirmed the hypothesized indirect effects among the key variables. In support of H3, psychological distress (HADS) significantly mediated the relationship between social support (SSRS) and sleep quality (PSQI). The total indirect effect was 0.089 (P < 0.005), while the direct effect remained significant at 0.122, resulting in a total effect of 0.211. This indicates that social support improves sleep quality both directly and indirectly by reducing psychological distress. Similarly, H4 was supported by the finding that psychological distress also mediated the association between pain and sleep quality. The total mediation effect of pain through HADS was 0.109 (P < 0.005), while the direct effect of pain on PSQI was 0.191, yielding a total effect of 0.300. These findings confirm that pain contributes to sleep disturbances not only through a direct pathway but also by exacerbating psychological distress, which in turn impairs sleep quality. Overall, the mediation analysis highlights the central role of psychological distress as a mediator linking both social and biological factors to sleep outcomes in this population.

Discussion

This study investigated the factors influencing sleep disturbances in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy using a SEM approach. The results revealed that psychological distress (HADS) and pain levels (NRS) were significant predictors of sleep quality (PSQI), with higher psychological distress and pain leading to poorer sleep outcomes. Social support (SSRS) was found to have an indirect effect on sleep quality, primarily mediated through its impact on psychological distress. Coping strategies (SCSQ) did not show a statistically significant direct effect on sleep quality. The path analysis confirmed that pain significantly influenced both psychological distress and sleep quality, suggesting that pain management is crucial for improving sleep among these patients. The model fit indices indicated a good fit, supporting the robustness of the proposed framework. These findings highlight the importance of psychological well-being, pain management, and social support interventions in mitigating sleep disturbances in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

To further contextualize these findings, several psychophysiological mechanisms may help explain how pain and psychological distress contribute to sleep disturbance in this population. Cognitive–emotional hyperarousal, maladaptive sleep-related beliefs, and attentional bias toward somatic sensations contribute to a heightened state of arousal that interferes with normal sleep regulation (23). Patients experiencing pain or elevated psychological distress may become overly attentive to bodily cues and develop negative interpretations of sleep difficulties, which further exacerbate sleep disruption (24). These mechanisms provide theoretical support for the mediating role of psychological distress found in our structural equation model.

Building on these mechanisms, anxiety and depression—two key components of psychological distress—may influence sleep through distinct pathways. Anxiety is more strongly associated with difficulties in initiating sleep, whereas depression tends to contribute to early morning awakenings and reduced total sleep time. Using a combined HADS score may therefore obscure these differential effects, and future studies may consider analyzing anxiety and depression separately to better elucidate their specific contributions to sleep disturbance.

Another plausible explanation for the non-significant association between coping strategies and sleep quality is that coping was modeled as a single composite construct in this study. Coping is inherently multidimensional, and different subtypes—such as avoidant versus approach-based coping, and emotion-focused versus problem-focused coping—may have divergent effects on psychological distress and sleep (25, 26). Some maladaptive strategies, such as avoidance, may exacerbate distress without directly influencing sleep, whereas more adaptive, problem-focused coping may reduce stress but still fail to produce immediate improvements in sleep outcomes. In addition, cultural characteristics common among Chinese cancer patients, including collectivistic values, family-centered decision-making, and cancer-related stigma, may shape coping preferences and lead individuals to rely more on internalized or avoidant strategies (27). These culturally influenced tendencies may partly explain why coping did not demonstrate a direct effect on sleep in our model. Future research should distinguish coping subtypes to clarify their specific roles in the psychosocial pathways affecting sleep.

The findings of this study align with previous research on the association between psychological distress, pain, and sleep disturbances in cancer patients. Prior studies have demonstrated that higher levels of anxiety and depression significantly impact sleep quality, leading to increased sleep latency, poorer sleep efficiency, and greater daytime dysfunction (28, 29). Similarly, our study confirmed that psychological distress, as measured by the HADS, had a significant negative effect on sleep quality, consistent with these earlier reports. Furthermore, pain has been well-documented as a major contributor to sleep disturbances in cancer patients, with studies indicating that pain interferes with sleep continuity and exacerbates nocturnal awakenings (30). Our findings reinforced this relationship, showing that pain directly impacted both psychological distress and sleep quality, emphasizing the necessity of pain management interventions in improving sleep outcomes.

However, a key difference between our study and previous research lies in the role of coping strategies. While some studies have suggested that adaptive coping mechanisms significantly improve sleep quality in cancer patients (31), our results did not identify a statistically significant direct effect of coping style on sleep quality. This discrepancy may be due to differences in measurement tools, cultural factors, or variations in coping strategy effectiveness depending on patient characteristics. Additionally, while social support has been widely recognized as a protective factor in mental health and sleep quality (32, 33), our findings indicate that its effect on sleep was mediated through psychological distress rather than having a direct impact, which has been similarly observed in other cancer populations (34). These findings contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how psychological, behavioral, and physiological factors interact in influencing sleep disturbances in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

This study employed SEM to analyze the complex relationships between social support, psychological distress, pain, coping strategies, and sleep quality among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. Unlike conventional regression-based analyses, SEM allows for simultaneous examination of direct and indirect pathways between multiple variables, providing a more comprehensive understanding of causal mechanisms (35). The model demonstrated a good fit with the data, suggesting that the hypothesized relationships were well-supported. This advanced statistical method has been increasingly utilized in psycho-oncology research (36, 37).

One novel aspect of our study is the identification of psychological distress as a key mediator in the relationship between social support and sleep quality. While previous studies have established that social support improves sleep quality (38), our results suggest that its effect is indirect and mediated through reductions in anxiety and depression. This finding highlights the need for psychosocial interventions that not only enhance social support but also target mental health to achieve improvements in sleep outcomes. Another unique contribution is the examination of pain as both a direct and indirect determinant of sleep disturbances. Our results indicate that pain directly impairs sleep quality, while also increasing psychological distress, further exacerbating sleep problems. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of sleep disturbances in breast cancer patients and emphasize the importance of comprehensive symptom management strategies that integrate pain control, psychological support, and sleep interventions. Furthermore, while previous research has suggested a significant role of coping strategies in mental health and sleep quality (39), our study did not find a statistically significant direct effect of coping strategies on sleep. This result suggests that coping strategies may function more as an intermediary factor influencing psychological distress rather than directly affecting sleep quality. Future research should further explore the role of different coping styles in relation to long-term sleep outcomes and whether specific coping interventions could enhance psychological resilience and improve sleep patterns in breast cancer patients.

Conclusion

This study highlights the complex interplay of social support, psychological distress, pain, and coping strategies in influencing sleep disturbances among breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. By employing a structural equation model, the findings emphasize the need for a multidimensional approach to improving sleep quality in this population. Psychological distress and pain were identified as key contributors to poor sleep, suggesting that targeted interventions focusing on mental health support and pain management may be beneficial. Moreover, the role of social support in alleviating sleep disturbances underscores the importance of strengthening support networks for patients during treatment. While this study provides valuable insights, future research should consider longitudinal designs to establish causality and explore individualized interventions incorporating cognitive-behavioral and psychosocial strategies. Additionally, integrating objective sleep measures alongside self-reported data could enhance the accuracy of sleep assessments. Addressing these factors through a multidisciplinary approach may improve not only sleep outcomes but also the overall well-being of breast cancer patients during chemotherapy.

Limitations and future directions

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between psychological distress, coping strategies, and sleep disturbances. Second, the reliance on self-reported measures introduces potential recall bias and social desirability bias, which may affect the accuracy of responses. Third, the study was conducted in a single tertiary hospital, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations. Future research should employ longitudinal designs to establish causality, incorporate objective sleep measures such as actigraphy, and expand sample diversity across multiple centers to enhance generalizability. Additionally, exploring biological markers and developing targeted interventions, may provide further insights into improving sleep quality in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University. The studies were conducted in accordance with local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

TL: Methodology, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation. JW: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. RX: Writing – review & editing. YX: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Methodology.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the Self-Funded Scientific Research Project of the Health Commission of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (Grant No. Z-A20230453).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

13 January 2026 A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/fonc.2026.1768585.

02 February 2026 This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the scientific content of the article.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

2. Soewoto W and Nunik A. Estradiol levels and chemotherapy in breast cancer patients: A prospective clinical study. World J. Oncol. (2023) 14:60–6. doi: 10.14740/wjon1549

3. Zhang J, Qin Z, So TH, Chang TY, Yang S, Chen H, et al. Acupuncture for chemotherapy-associated insomnia in breast cancer patients: an assessor-participant blinded, randomized, sham-controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res. (2023) 25:49. doi: 10.1186/s13058-023-01645-0

4. Sanford SD, Wagner LI, Beaumont JL, Butt Z, Sweet JJ, Cella D, et al. Longitudinal prospective assessment of sleep quality: before, during, and after adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Support Care Cancer. (2013) 21:959–67. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1612-7

5. Trivedi R, Hong M, Madut A, Mather M, Elder E, Dhillon HM, et al. Irregular sleep/wake patterns are associated with reduced quality of life in post-treatment cancer patients: A study across three cancer cohorts. Front Neurosci. (2021) 15:700923. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.700923

6. Tagliaferri SD, Miller CT, Owen PJ, Mitchell UH, Brisby H, Fitzgibbon B, et al. Domains of chronic low back pain and assessing treatment effectiveness: A clinical perspective. Pain Pract. (2020) 20:211–25. doi: 10.1111/papr.12846

7. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. (1977) 196:129–36. doi: 10.1126/science.847460

8. Lee Y-H. Relationship analogy between sleep bruxism and temporomandibular disorders in children: A narrative review. Children (Basel). (2022) 9:1466. doi: 10.3390/children9101466

9. Cohen SP, Vase L, and Hooten WM. Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet. (2021) 397:2082–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00393-7

10. Wu N, Ding F, Ai B, Zhang R, and Cai Y. Mediation effect of perceived social support and psychological distress between psychological resilience and sleep quality among Chinese medical staff. Sci Rep. (2024) 14:19674. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-70754-3

11. Zhao Y, Hu B, Liu Q, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Zhu X, et al. Social support and sleep quality in patients with stroke: The mediating roles of depression and anxiety symptoms.I. nt J Nurs Pract. (2022) 28:e12939. doi: 10.1111/ijn.12939

12. Corey KL, McCurry MK, Sethares KA, Bourbonniere M, Hirschman KB, Meghani SH, et al. Predictors of psychological distress and sleep quality in former family caregivers of people with dementia. Aging Ment Health. (2020) 24:233–41. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1531375

13. Kim Kevin H. relation among fit indexes, power, and sample size in structural equation modeling.Structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. (2005) 12:368–90.

14. Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, and Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. (1989) 28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4

15. Lloyd M, Sugden N, Thomas M, McGrath A, and Skilbeck C. The structure of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Br J Psychol. (2023) 114:457–75. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12637

16. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, and Neckelmann D. The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: an updated literature review. J Of Psychosomatic Res. (2002) 52:69–77. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(01)00296-3

17. Bao T, Baser R, Chen C, Weitzman M, Zhang YL, Seluzicki C, et al. Health-related quality of life in cancer survivors with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: A randomized clinical trial. Oncologist. (2021) 26:e2070–8. doi: 10.1002/onco.13933

18. Shuiyuan X. The theoretical basis and research application of social support rating scale. J Of Clin Psychiatry. (1994) 2:98–100.

19. Xie YN. A preliminary study on the reliability and validity of the simple coping style scale. Chin J Clin Psychol. (1998) 6:114–5.

20. Ferreira-Valente M, Pais-Ribeiro JL, and Jensen MP. Validity of four pain intensity rating scales. Pain. (2011) 152:2399–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.07.005

21. O’Boyle Ernest H and Williams LJ. Decomposing model fit: measurement vs. theory in organizational research using latent variables. J Appl Psychol. (2011) 96:1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0020539

22. Lamoureux BE, Palmieri PA, Jackson AP, and Hobfoll SE. Child sexual abuse and adulthood-interpersonal outcomes: Examining pathways for intervention. Psychol Trauma. (2012) 4:605–13. doi: 10.1037/a0026079

23. Fernández-Mendoza J, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN, Ramos-Platón MJ, Olavarrieta-Bernardino S, Bixler EO, et al. Cognitive-emotional hyperarousal as a premorbid characteristic of individuals vulnerable to insomnia. Psychosom Med. (2010) 72:397–403. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181d75319

24. Savard J and Morin CM. Insomnia in the context of cancer: a review of a neglected problem. J Clin Oncol. (2001) 19:895–908. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.3.895

25. Carver CS, Scheier MF, and Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. (1989) 56:267–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267

26. Folkman S and Moskowitz JT. Coping: pitfalls and promise. Annu Rev Psychol. (2004) 55:745–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141456

27. You J, Wang C, Rodriguez L, Wang X, and Lu Q. Personality, coping strategies and emotional adjustment among Chinese cancer patients of different ages. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). (2018) 27(1). doi: 10.1111/ecc.12781

28. Cho O-H and Hwang K-H. Association between sleep quality, anxiety and depression among Korean breast cancer survivors. Nurs Open. (2021) 8:1030–7. doi: 10.1002/nop2.710

29. Pecorari G, Moglio S, Gamba D, Briguglio M, Cravero E, Sportoletti Baduel E, et al. Sleep quality in head and neck cancer. Curr Oncol. (2024) 31:7000–13. doi: 10.3390/curroncol31110515

30. Daniel LC, Meltzer LJ, Gross JY, Flannery JL, Forrest CB, Barakat LP, et al. Sleep practices in pediatric cancer patients: Indirect effects on sleep disturbances and symptom burden. Psychooncology. (2021) 30:910–8. doi: 10.1002/pon.5669

31. Hoyt MA, Thomas KS, Epstein DR, and Dirksen SR. Coping style and sleep quality in men with cancer. Ann Behav Med. (2009) 37:88–93. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9079-6

32. Yung ST, Main A, Walle EA, Scott RM, and Chen Y. Associations between sleep and mental health among latina adolescent mothers: the role of social support. Front Psychol. (2021) 12:647544. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647544

33. Yang L-L, Guo C, Li G-Y, Gan K-P, and Luo J-H. Mobile phone addiction and mental health: the roles of sleep quality and perceived social support. Front Psychol. (2023) 14:1265400. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1265400

34. Geremew H, Abdisa S, Mazengia EM, Tilahun WM, Haimanot AB, Tesfie TK, et al. Anxiety and depression among cancer patients in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1341448. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1341448

35. Trumello C, Vismara L, Sechi C, Ricciardi P, Marino V, Babore A, et al. Internet addiction: the role of parental care and mental health in adolescence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:12876. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182412876

36. Wolyniec K, Sharp J, Fisher K, Tothill RW, Bowtell D, Mileshkin L, et al. Psychological distress, understanding of cancer and illness uncertainty in patients with Cancer of Unknown Primary. Psychooncology. (2022) 31:1869–76. doi: 10.1002/pon.5990

37. Ulibarri-Ochoa A, Macía P, Ruiz-de-Alegría B, García-Vivar C, and Iraurgi I. The role of resilience and coping strategies as predictors of well-being in breast cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. (2024) 71:102620. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2024.102620

38. Cui C and Wang L. Role of social support in the relationship between resilience and sleep quality among cancer patients. Front Psychiatry. (2024) 15:1310118. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1310118

Keywords: breast cancer, chemotherapy, sleep disorders, psychological distress, pain, social support, coping strategies, structural equation modeling

Citation: Lu T, Wei J, Xiong R and Xu Y (2025) A structural equation model study on the influencing factors of sleep disorders in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Front. Oncol. 15:1633763. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1633763

Received: 02 September 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 18 November 2025;

Published: 12 December 2025; Corrected: 02 February 2026.

Edited by:

Francesco Bruno, Mercatorum University, ItalyReviewed by:

Valentina Laganà, ASP Catanzaro, ItalyPaolo Abondio, IRCCS Institute of Neurological Sciences of Bologna (ISNB), Italy

Copyright © 2025 Lu, Wei, Xiong and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Xu, NDkxOTEyNzk2QHFxLmNvbQ==

Ting Lu1

Ting Lu1