- 1Department of Clinical Laboratory, The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University & Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, China

- 2Department of Hematology, The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University & Henan Cancer Hospital, Zhengzhou, China

Background: Identifying the early markers of transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) and mild or severe acute graft-versus-host disease poses a significant challenge in the differential diagnosis of severe complications after allo-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT).

Methods: We conducted an analysis of 109 patients who developed TA-TMA, grade I-II aGVHD , and grade III-IV aGVHD following allo-HSCTs at our center between 2019 and 2024. Clinical features, laboratory data and outcomes were compared among these groups.

Results: The median diagnostic time for TA-TMA was 94 days post-transplant, with median survival of 1 month for TA-TMA and 2 months for grade III-IV aGVHD, significantly shorter than 5 months for grade I-II aGVHD. Survival curves for TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD were poorer. Risk factors (RFs) for TA-TMA included fragmented red blood cell proportion, elevated LDH, and renal injury, with hemoglobin showing a protective effect. Cox analysis identified hypertension, cardiac insufficiency, renal injury, fragmented red blood cells, LDH, platelet counts, hemoglobin, and albumin as significant mortality factors for TA-TMA. For grade III-IV aGVHD, hypertension, renal injury, fragmented red blood cells, LDH, TBIL, platelet counts, hemoglobin, and albumin were significant. Multivariate analysis showed that fragmented red blood cells, elevated LDH, and renal injury predicted higher mortality for TA-TMA, while higher platelet counts and albumin levels predicted lower mortality. No independent prognostic factors were found for grade III-IV aGVHD.

Conclusion: Our analysis highlights the significant challenge of late diagnosis and high mortality in TA-TMA following allo-HSCT. It further identifies a panel of accessible clinical indicators that can aid in early risk assessment and prognostication.

Introduction

Transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA) and acute graft-versa-host disease (aGVHD) are typically manifesting within the first 100 days post-transplant. These conditions represent critical factors influencing the success of HSCT, with aGVHD being the most prevalent, but TA-TMA poses a greater threat due to its rapid progression and high mortality rate (1–7). Diagnosis is usually based on the criteria stipulated by either Europe (European Bone Marrow Transplant International Working Group) (8) or United States (Blood and Marrow Transplantation Clinical Trial Network) (9), but the uniformity of these standards remains to be studied. Grade 2–4 aGVHD was found to be an adjusted risk factor for TA-TMA (10) and lead to an increased risk of death in TA-TMA (11), but further research is needed to understand the overlap of disease mechanisms and the underlying relationships. aGVHD usually occurs in the acute phase after allo-HSCT, when TA-TMA is most commonly observed (5). Both TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD exhibit numerous overlapping clinical symptoms, making it more difficult to distinguish between these two diseases. To date, there have been no reports on distinguishing TA-TMA from aGVHD, an accurate diagnosis and early start of etiological treatment that alter the natural history of these serious conditions may best improve patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Patient selection/data source

This study was conducted at the Hematology Department of Henan Cancer Hospital, and this trial was registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (SBGJ202102069). This retrospective study consecutively enrolled 376 patients who underwent allo-HSCT at our institution between January 2019 and June 2024. Among them, 38 patients (10.1%) developed TA-TMA, 153 (40.7%) developed grade I–II aGVHD, and 64 (17.0%) developed grade III–IV aGVHD. Patients in the TA-TMA cohort were excluded if they met any of the following criteria: (1) missing essential clinical or laboratory data at the time of diagnosis; (2) co-occurrence of other severe thrombotic disorders, such as disseminated intravascular coagulation or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; or (3) death within 21 days after transplantation, which precluded adequate assessment of complications. 33 patients with TA-TMA were included in the final analysis. For comparative purposes, 51 patients with grade I–II aGVHD and 25 with grade III–IV aGVHD were randomly selected using matching ratios ranging from 1:2 to 1:3. Matching was based on age (± 3 years), transplantation modality, and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) compatibility. The exclusion criteria for patients with aGVHD are the same as those for TA-TMA. The information collected includes primary diseases (including acute myeloid leukemia [AML], acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL], myelodysplastic syndrome [MDS], severe aplastic anemia [SAA]), other hematological diseases [others]), clinical course records, clinical symptoms, laboratory test results, and patient follow-up information.

TA-TMA, GVHD definitions and managements

The diagnostic criteria for TA-TMA can meet any of the following established standards: the BMT-CTN criteria (9), the O-TMA criteria (12), the Probable-TA-TMA criteria (12), or the Jodele criteria (13, 14). Acute GVHD was graded and staged using Glucksberg criteria, and grading of cGVHD was performed according to Seattle criteria (15). And the concordance among patients meeting different TA-TMA criteria was shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Data collection and definition

Routine laboratory tests included complete blood count, urine routine, liver function, renal function, myocardial enzymes, c-reactive protein (CRP), and the fragmented red blood cell proportion in peripheral blood. The virus serological status was determined to be either negative or positive based on the quantitative results of cytomegalovirus (CMV), Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), and polyomavirus BK (PBK) before HSCT and at the time of diagnosis. Transplant-related factors included transplant type, stem cell sources, ABO blood type compatibility between donor and recipient, disease status before HSCT, minimal residual disease (MRD) status before HSCT, number of mononuclear cells (MNC) received, number of CD34+ cells received, pretreatment protocol.

Treatment, outcome and follow-up

Conditioning regimens were selected based on disease status, patient age, and comorbidities. The primary myeloablative conditioning (MAC) regimens were busulfan/cyclophosphamide (Bu/Cy) and cyclophosphamide/total body irradiation (Cy/TBI). The main reduced-intensity conditioning (RIC) regimens were fludarabine/busulfan (Flu/Bu) and fludarabine/melphalan (Flu/Mel). For GVHD prophylaxis, most patients with matched related or unrelated donors received a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) plus methotrexate. Effective management of TA-TMA is hampered by obscure pathogenesis and delayed diagnosis. There are no well-acknowledged therapeutic strategies for TA-TMA. The effective management of TA-TMA is hindered by an elusive pathogenesis and often delayed diagnosis. Currently, no universally standardized therapy exists. Management primarily centers on complement-targeted agents (eculizumab) and comprehensive supportive care to address complications such as hypertension and renal dysfunction. While interventions like therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), rituximab, or defibrotide may be considered in specific cases, they lack robust evidence and are not routinely recommended. Follow-up was conducted by telephone until December 31, 2024, including efficacy of treatment, patient outcomes and survival status.

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. The probabilities of overall survival (OS) was estimated using Kaplan-Meier method and the groups were compared using log-rank test. Multivariate analysis of potential confounders associated with diagnosis was conducted using Cox proportional hazards regression model, both univariate and multivariate analyses of key factors associated with diagnosis and prognosis were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression model, with hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) reported. p value <0.05 was considered significant. Data were processed and analyzed using SPSS Version 27.0 (SPSS, Inc) and R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Clinical features of patients with TA-TMA and aGVHD

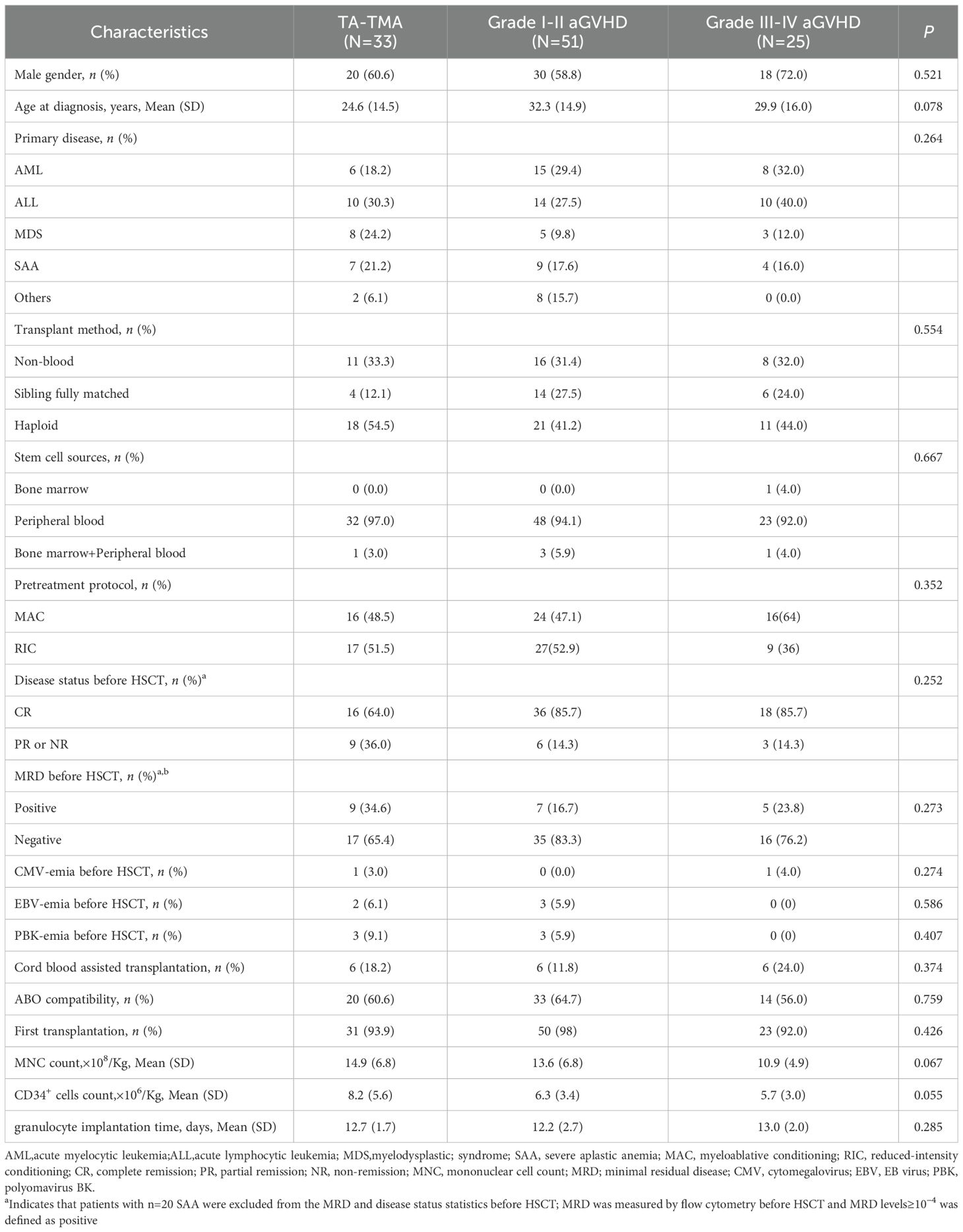

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the included cases are shown in Table 1. Our data showed no obvious gender tendency (p>0.05) and no significant age concentration (p>0.05) in the disease groups, and there were no significant differences in the type of primary disease, the pre-transplant MRD positivity rate, and the pre-transplant disease remission status (all p>0.05; Table 1). Among the 33 patients diagnosed with TA-TMA, 21.2% (7/33) developed the disease within one month post allo-HSCT, 57.6% (19/33) within three months post allo-HSCT, and 97.0% (32/33) within one year post allo-HSCT. The median time post-transplant diagnosis of TA-TMA, grade I-II aGVHD, and grade III-IV aGVHD was 94 days (range 39 to 667 days), 30 days (range 6 to 136 days), and 28 days (range 6 to 184 days), respectively, with TA-TMA being the latest (p < 0.001). 31 TA-TMA patients were combined with aGVHD (one of which was late aGVHD, and five were converted from aGVHD to cGVHD), one was combined with cGVHD, and one had no GVHD. All TA-TMA diagnosis were during GVHD process.

Analysis of transplant-related factors and laboratory data of three groups

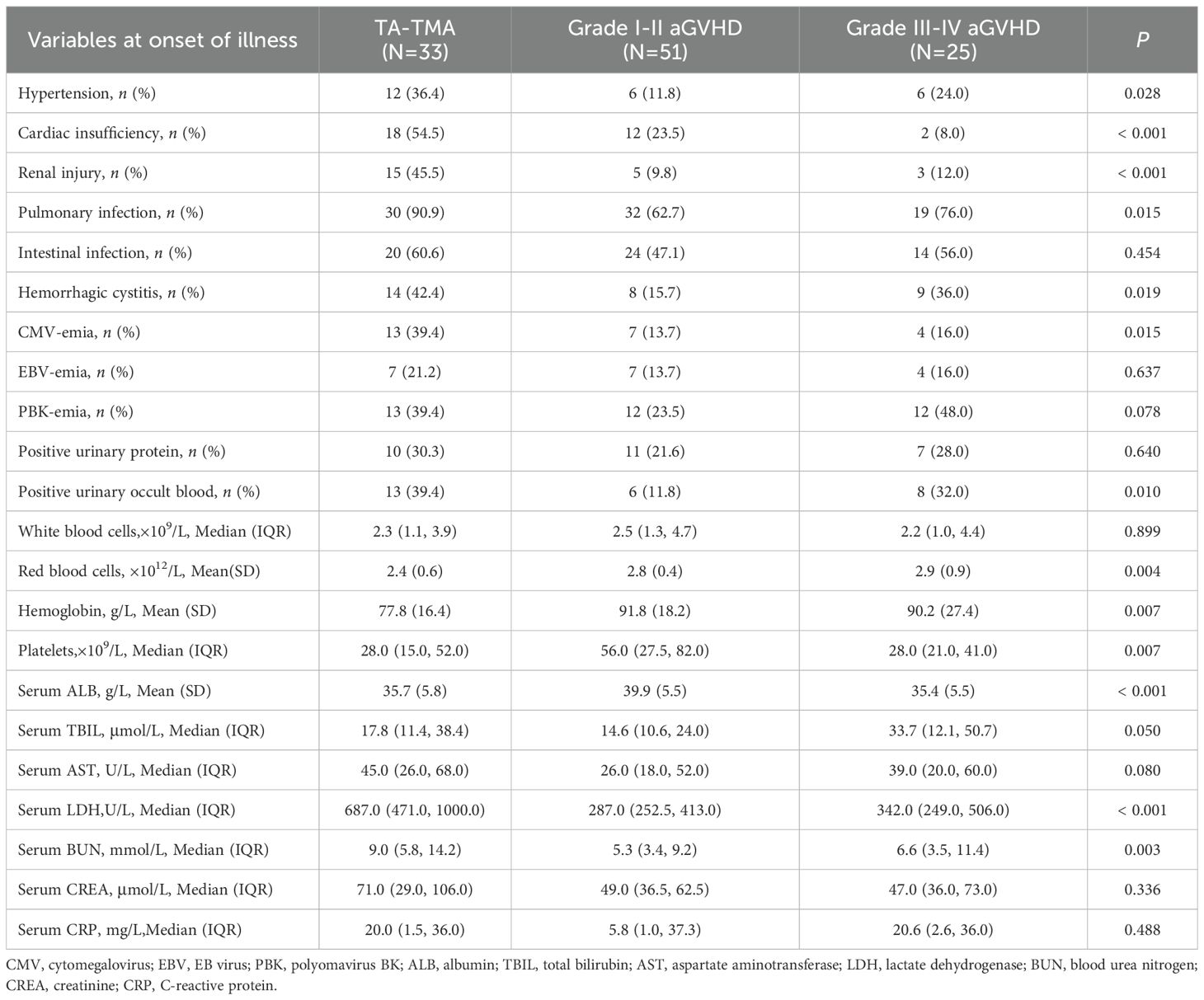

Transplant-related results showed that there were no significant differences among the groups in first transplantation or not, transplantation method, stem cell sources, with or without cord blood assisted transplantation, ABO compatibility, pretreatment protocol, incidence of CMV-emia, EBV-emia, and PBK-emia before HSCT, CD34+ cells count, MNC count, and granulocyte implantation time post-transplantation (all p>0.05; Table 1). Three disease groups were prone to intestinal infection, EBV-emia, PBK-emia, and positive urinary protein at the onset of disease, and there was no significant difference in symptoms (all p>0.05). There were no significant differences among the three groups in numbers of white blood cells, AST, CREA, and CRP levels (all p>0.05). The incidence of hypertension, cardiac insufficiency, renal injury, pulmonary infection, CMV-emia and serum LDH and BUN levels in TA-TMA group were significantly higher than those in grade I-II aGVHD and grade III-IV aGVHD groups, and the counts of red blood cells and hemoglobin levels were significantly lower in the TA-TMA group (all p < 0.05). The incidence of positive urinary occult blood and hemorrhagic cystitis in TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD groups were higher than those in aGVHD I-II group, and the levels of platelet and serum ALB in TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD groups were lower than those in grade I-II aGVHD group. Serum TBIL levels in III-IV aGVHD group were lower than those in TA-TMA and grade I-II aGVHD groups (all p < 0.05 or p = 0.05; Table 2).

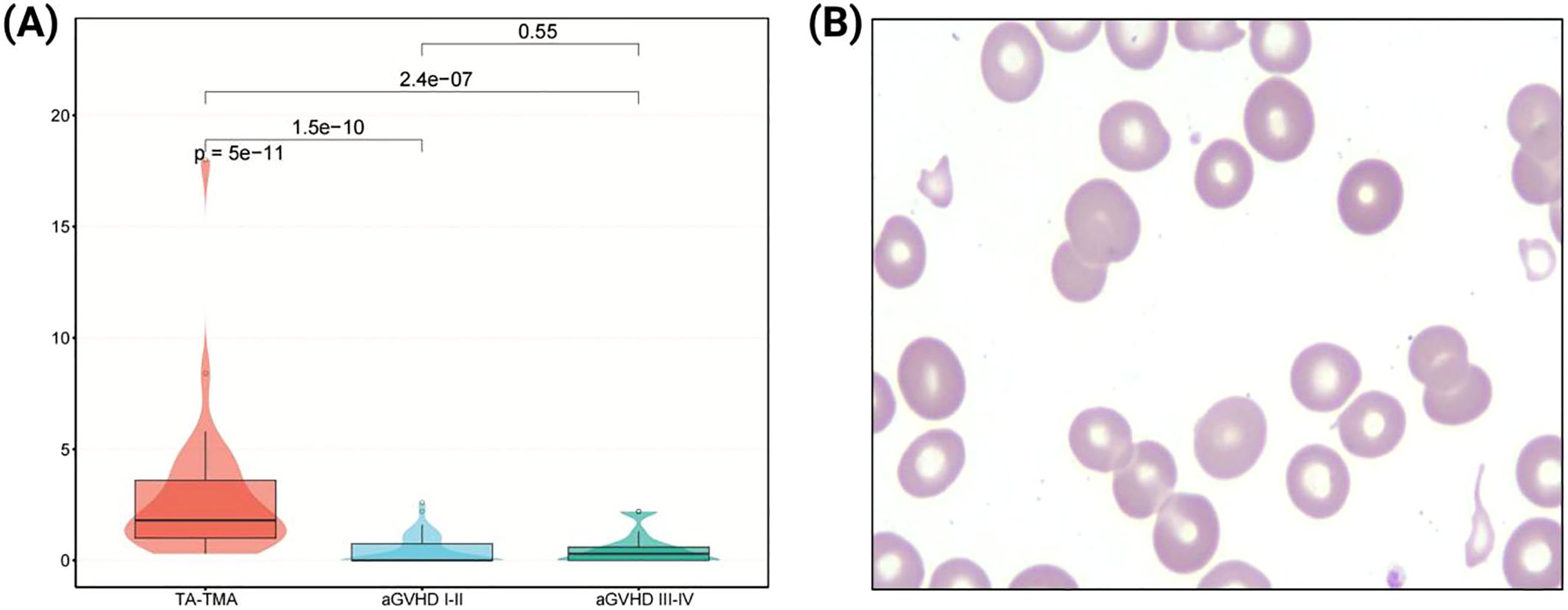

Fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood

At the time of diagnosis, the proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood of TA-TMA patients ranged from 0.6% to 18%, with a Median (IQR) of 1.8% (1.0%, 3.6%), of which only 6 cases (18.2%) were <1%, and 16 cases (48.5%) were between 1% and 3%, 11 cases (33.3%) were ≥3%. Meanwhile, in patients with grade I-II aGVHD, the proportion ranged from 0.0% to 2.6%, with a Median (IQR) of 0.0% (0.0%, 0.8%), of which 39 cases (76.5%) were <1%, and the rest were <3%. In patients with grade III-IV aGVHD, the proportion ranged from 0.0% to 2.2%, with a median (IQR) of 0.3% (0.0%, 0.6%), of which 21 cases (84.0%) were <1%, and the rest were <3%. Proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood in TA-TMA patients was significantly higher (p < 0.001; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analysis of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood. (A) Comparison of the proportion of fragmented red blood cells among three groups. (B) Morphological features of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood smear (1000×).

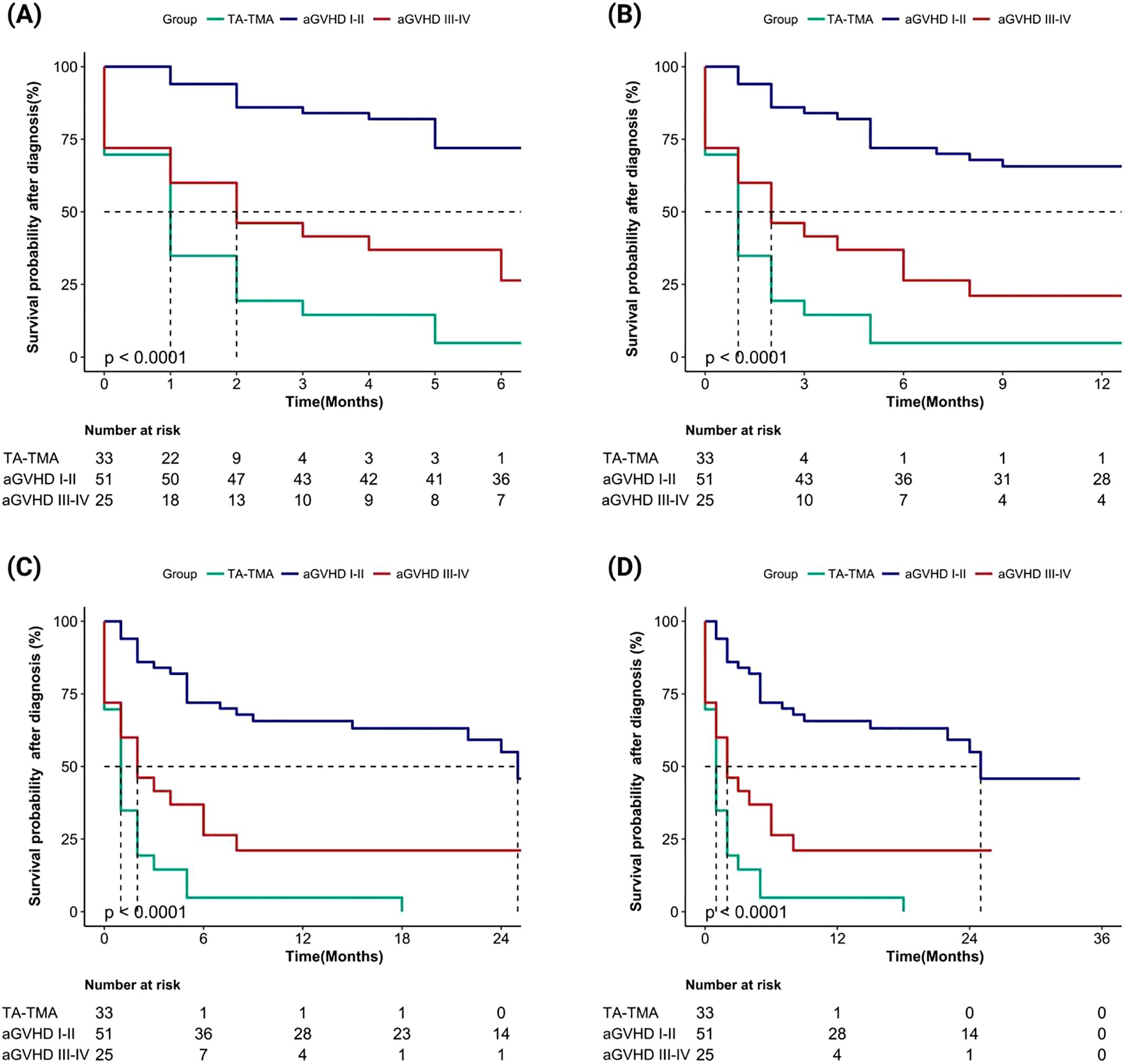

Analysis of patients’ survival

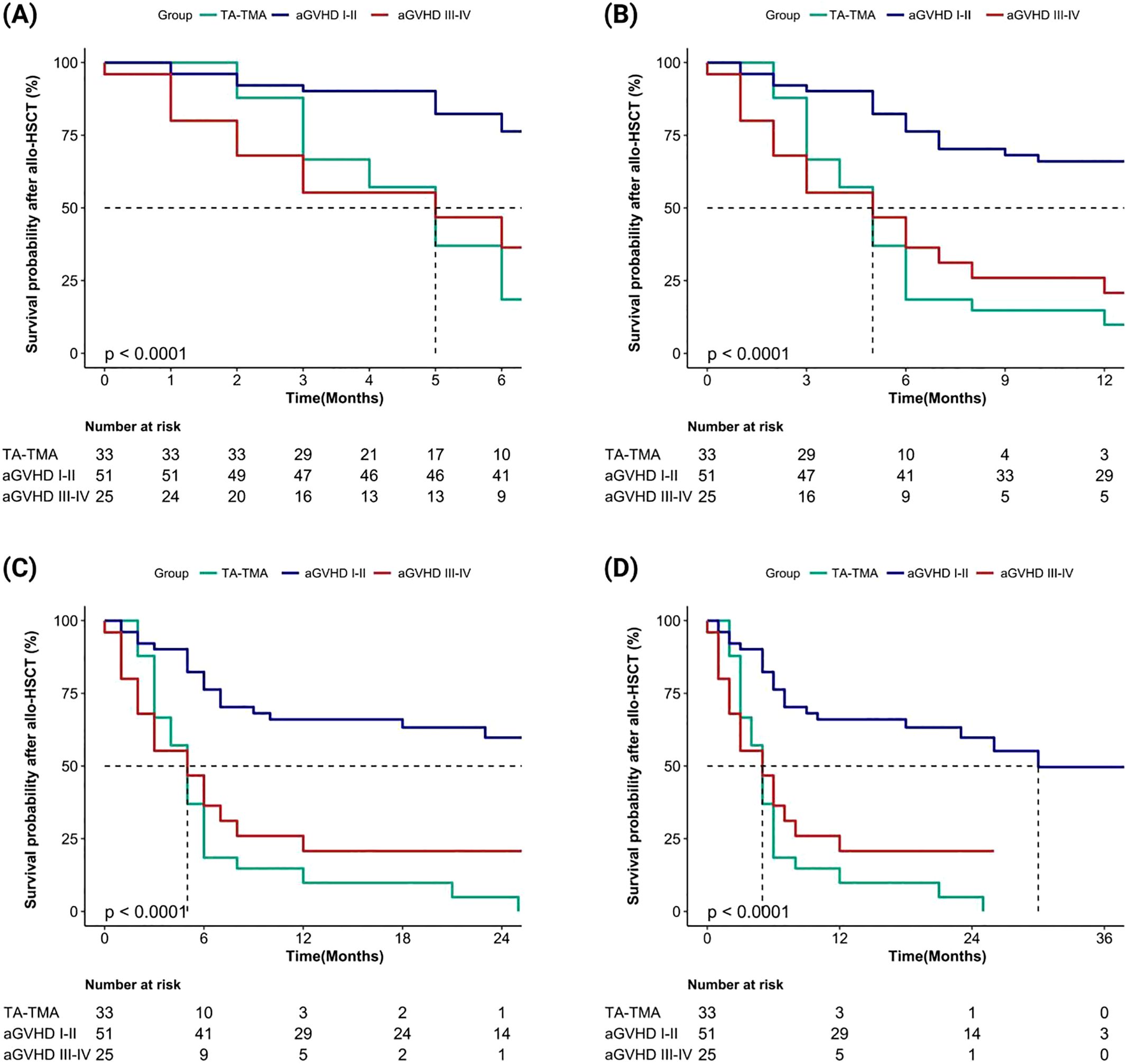

We evaluated the cumulative mortality and overall survival of 109 patients up to the follow-up date. The cumulative mortality rates for TA-TMA, grade I-II aGVHD, and grade III-IV aGVHD were 90.9% (30/33), 43.1% (22/51), and 72.0% (18/25), respectively. The interquartile range (IQR) of overall survival months after allo-HSCT were 5.0 (3.0, 6.0), 16.0 (7.0, 26.0), and 5.0 (2.0, 7.0), respectively. The IQR of the overall survival months after diagnosis were 1.0 (0.0, 2.0), 15.0 (5.0, 24.0), and 2.0 (0.0, 6.0), respectively. Compared to grade I-II aGVHD, the mortality rates of TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD were significantly higher, and both survival months after allo-HSCT and after diagnosis were significantly worse (all p < 0.001). We further calculated the overall survival rates of patients at 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, and 3 years after allo-HSCT and after diagnosis, the results showed that the overall survival rate of TA-TMA was the worst, followed by grade III-IV aGVHD and grade I-II aGVHD, and the differences among the three groups were statistically significant (all p<0.001; Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 2. Comparison of overall survival rates after diagnosis among TA-TMA, aGVHD I-II and aGVHD III-IV groups (aGVHD I-II: grade I-II aGVHD; aGVHD III-IV: grade III-IV aGVHD ). (A) Patients’ survival at 6 months; (B) Patients’ survival at 1 year; (C) Patients’ survival at 2 years; (D) Patients’ survival at 3 years.

Figure 3. Comparison of overall survival rates after allo-HSCT among TA-TMA, aGVHD I-II and aGVHD III-IV groups (aGVHD I-II: grade I-II aGVHD; aGVHD III-IV: grade III-IV aGVHD). (A) Patients’ survival at 6 months; (B) Patients’ survival at 1 year; (C) Patients’ survival at 2 years; (D) Patients’ survival at 3 years.

Multivariate analysis for the occurrence of disease

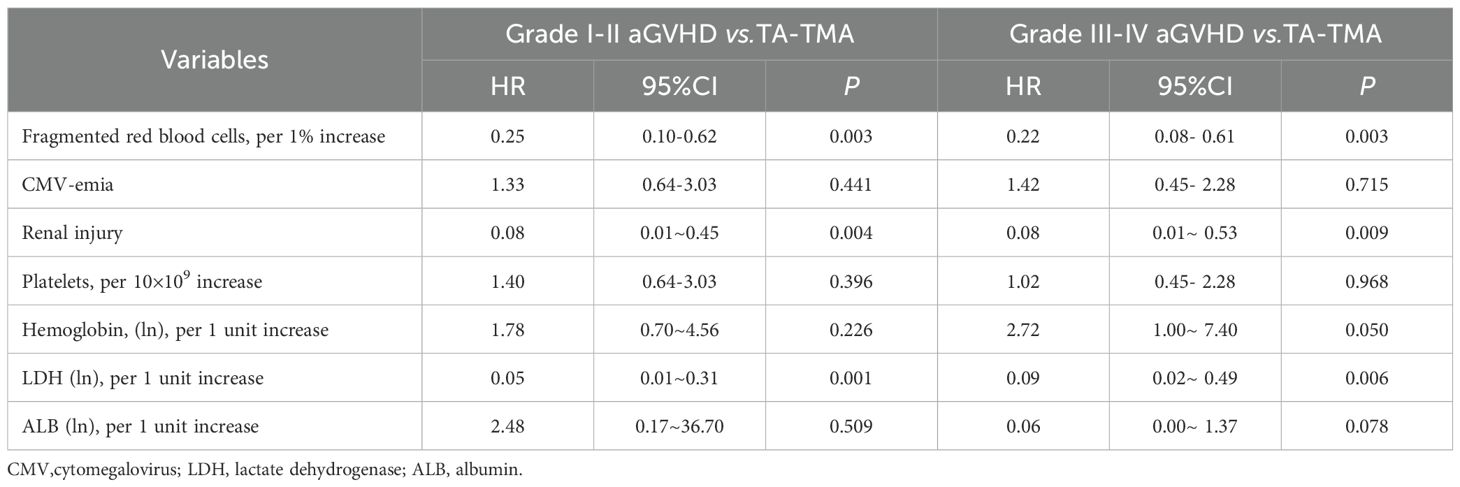

To further understand the risk factors for disease occurrence, we performed multivariate Cox regression analysis between groups separately. Risk assessment results, with outcome variable set as TA-TMA and grade I-II aGVHD showed that an increased proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood (per 1% increase, HR 0.25, 95% CI 0.10-0.62, p = 0.003), serum LDH levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 0.05, 95% CI 0.10-0.31, p = 0.001), and renal injury (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01-0.45, p = 0.004) were significantly associated with the risk of developing TA-TMA (Table 3). For outcome variables set as TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD, the risk assessment revealed that an increased proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood (per 1% increase, HR 0.22, 95% CI 0.08-0.61, p = 0.003), hemoglobin levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 2.72, 95% CI 1.00-7.40, p = 0.050), serum LDH levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 0.09, 95% CI 0.02-0.49, p = 0.006), and renal injury (HR 0.08, 95% CI 0.01-0.53, p = 0.009) were significantly associated with the risk of developing TA-TMA, among which hemoglobin was a protective factor for TA-TMA (Table 3).

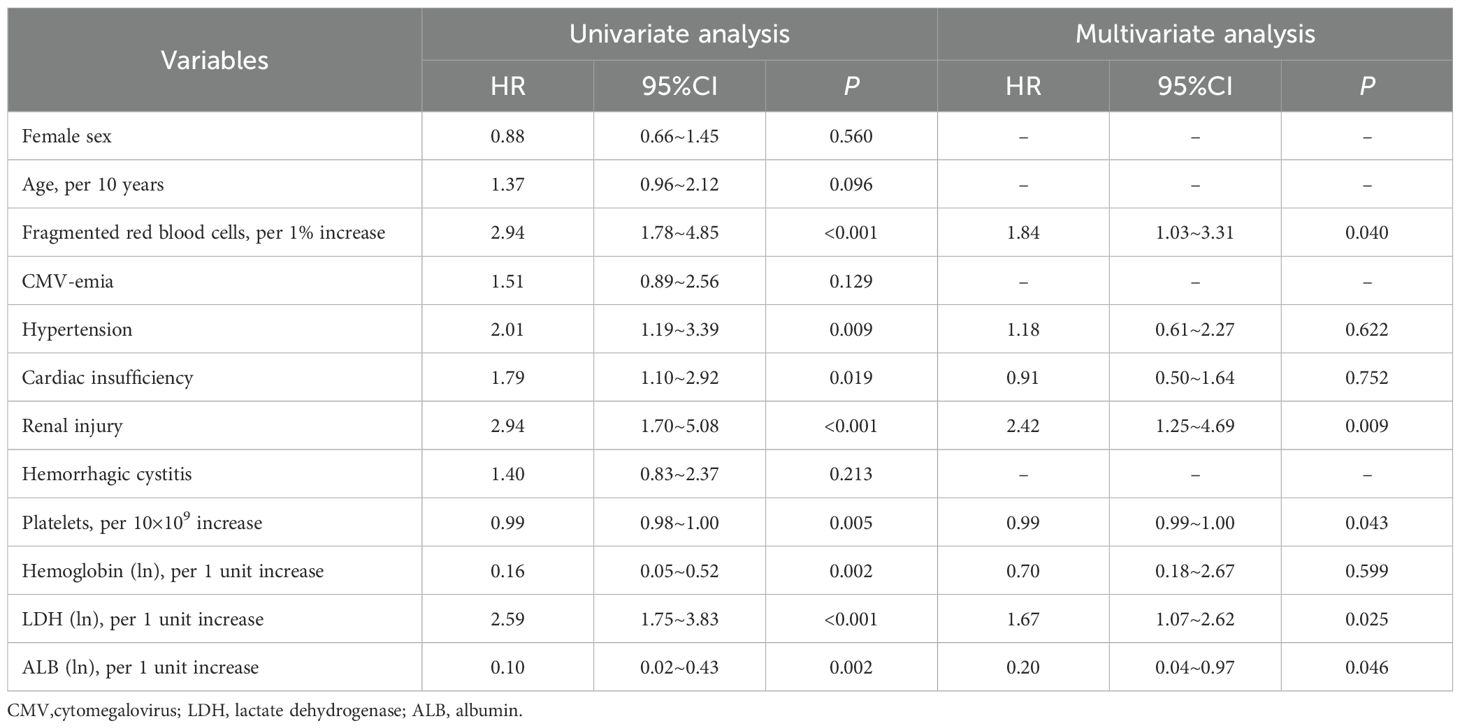

Risk factors for death in TA-TMA

The median overall survival of TA-TMA after allo-HSCT and diagnosis was only 5 months and 1 month, respectively, although treatment measures were taken immediately after diagnosis, there was no significant improvement in the survival rate of TA-TMA. The leading causes of death were infection, active TA-TMA, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Therefore, we introduced variables into COX regression model, with death for all causes as the competing risk. Univariate analysis showed that CMV-emia and hemorrhagic cystitis did not increase the risk of death from TA-TMA (both p>0.05), in contrast, several factors were found to be significantly associated with the risk of death from TA-TMA: hypertension (HR 2.01, 95%CI 1.19-3.39, p = 0.009), cardiac insufficiency (HR 1.79, 95%CI 1.10-2.92, p = 0.019), renal injury (HR 2.94, 95%CI 1.70-5.08, p < 0.001), proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood (per 1% increase, HR 2.94, 95%CI 1.78-4.85, p < 0.001), LDH levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 2.59, 95%CI 1.75-3.83, p < 0.001), platelet counts (per 10×109 increase, HR 0.99, 95%CI 0.98-1.00, p = 0.005), hemoglobin levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 0.16, 95%CI 0.05-0.52, p = 0.002), and ALB levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 0.10, 95%CI 0.02-0.43, p = 0.002) (Table 4). Cox multivariate analysis showed that a higher proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood (per 1% increase, HR 1.84, 95%CI 1.03-3.31, p = 0.040), elevated serum LDH levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 1.67, 95%CI 1.07-2.62, p = 0.025) and renal injury (HR 2.42, 95%CI 1.25-4.69, p = 0.009) were prone to be independent risk factors associated with an increased risk of death for TA-TMA, conversely, higher platelet counts (per 10×109 increase, HR 0.99, 95%CI 0.99-1.00, p = 0.043) and elevated serum ALB levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed ln, HR 0.20, 95%CI 0.04-0.97, p = 0.046) were prone to be independent protective factors associated with a decreased risk of death for TA-TMA (Table 4).

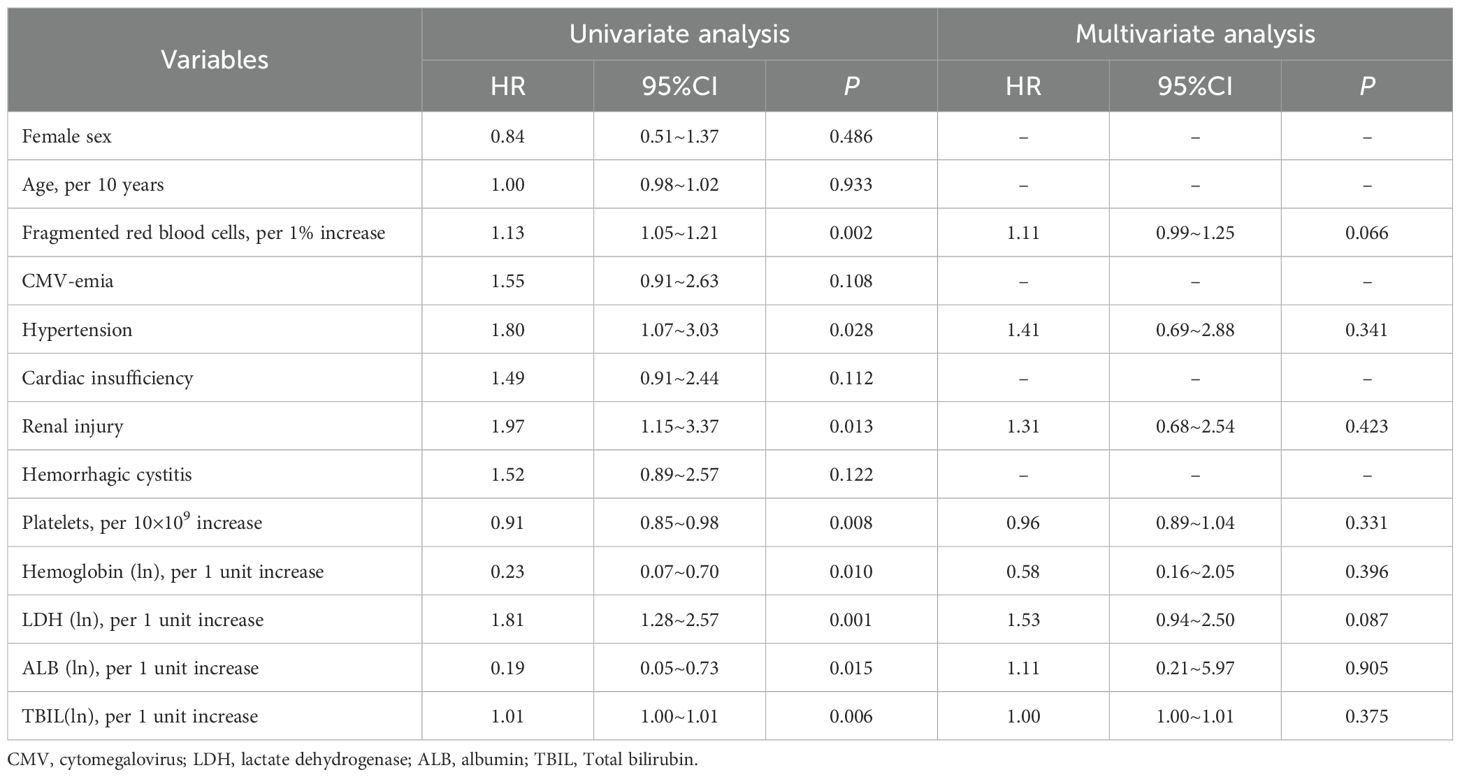

Risk factors for death in grade III-IV aGVHD

The survival curve for patients with grade III-IV aGVHD was inferior only to that of TA-TMA. By analyzing univariate Cox proportional risk ratios, it was determined that hypertension (HR 1.80, 95%CI 1.07~3.03, p = 0.028), renal injury (HR 1.97, 95%CI 1.15~3.37, p = 0.013), proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood (transformed-ln, HR 1.81, 95%CI 1.28~2.57, p = 0.001), TBIL levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed-ln, HR 1.01, 95%CI 1.00~1.01, p = 0.006), platelet counts (per 10×109 increase, HR 0.91, 95%CI 0.85~0.98, p = 0.008), hemoglobin levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed-ln, HR 0.23, 95%CI 0.07~0.70, p = 0.010), ALB levels (per 1 unit increase of transformed-ln, HR 0.19, 95%CI 0.05~0.73, p = 0.015) jointly affected the survival of grade III-IV aGVHD patients. Cox multivariate analysis showed that none of the above factors exhibited independent clinical prognostic significance (all p>0.05; Table 5).

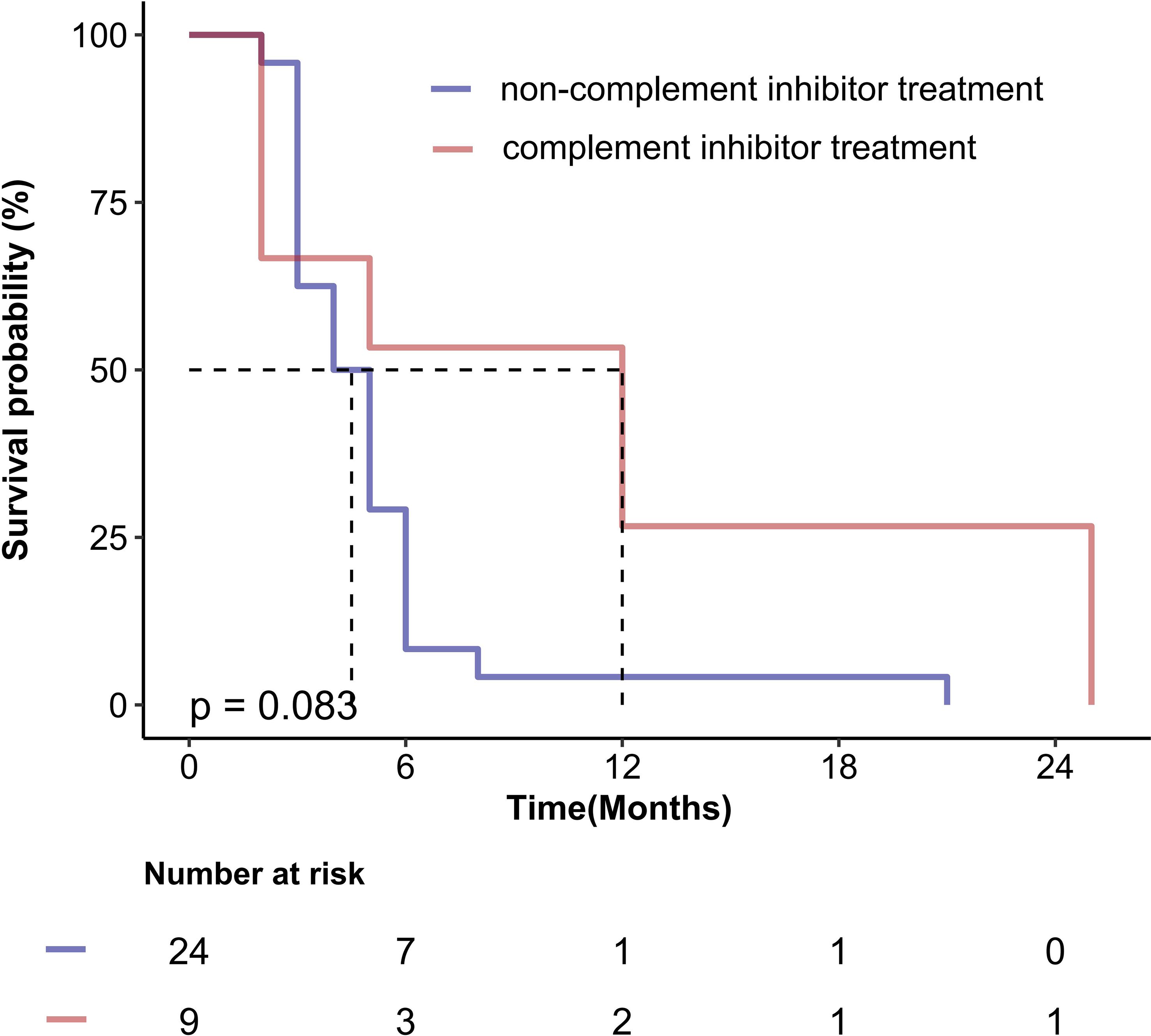

Survival outcomes of TA-TMA patients

Given the critical importance of treatment strategy, we performed an exploratory comparison of survival outcomes based on the primary therapies received by patients with TA-TMA. Among the 33 patients in the cohort, 9 received complement inhibitor treatment therapy, while the remaining 24 received only supportive care for complications and/or therapeutic plasma exchange. It is noteworthy that all three surviving patients were treated with eculizumab, although no statistically significant difference was observed between the groups (p = 0.083). The corresponding Kaplan-Meier survival curve is presented in Figure 4.

Discussion

TA-TMA is a microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and platelet consumption resulting from complement-mediated endothelial injury following allo-HSCT, resulting in microvascular thrombosis and fibrin deposition in the microcirculation (16). aGVHD, another more common and early complication after allo-HSCT, is induced by the direct endothelial injury mediated by host-reactive, donor-derived cytotoxic T cells (5). TA-TMA and grade 2–4 aGVHD are recognized risk factors for mortality after allo-HSCT (5, 17, 18), the clinical differentiation of the two represents a diagnostic challenge for transplant clinicians. All TA-TMAs in this study occurred during the process of GVHD. In our study, the cumulative mortality rate of TA-TMA was 90.9%, while the cumulative mortality rate of grade III-IV aGVHD was also as high as 72.0%, both of which are serious complications after allo-HSCT. Most studies have shown that the occurrence time of TA-TMA is between 32 days and 303 days after HSCT (5, 13, 17–25). In our study, the median onset time of TA-TMA was the 94th day after allo-HSCT, which was later than that of aGVHD, indicating that the occurrence of TA-TMA is more insidious, and may have a slow onset but a dangerous development.

The impact of various transplantation factors on TA-TMA has been reported by multiple institutions, including aGVHD, sex, prior autologous transplant, GVHD prophylaxis, donor type, source of stem cells (25, 26). And factors related to the risk of aGVHD are mainly reported as age and donor type (27–29). Our results showed no obvious tendency in age and gender between TA-TMA and aGVHD, nor were there any notable differences in the transplant-related factors examined in this study. To date, no literature has concurrently compared and analyzed these factors in both TA-TMA and aGVHD, precluding reference to differing outcomes. It is therefore worthy to incorporate a broader range of transplant-related indicators in future multi-center and long-term studies.

In 2012, the International Council for Standardization in Hematology (ICSH) proposed that more than 1% of morphologically identified schistocytes on the blood film are considered suspicious for TMA (30). Report for 2021 suggested that the detection of more than 1% schistocytes on PB smears in adults and full-term neonates remained a robust cytomorphological threshold that favors a diagnosis of TMA (31). In our study, the proportion of fragmented red blood cells in TA-TMA was more than 1%, which was consistent with the literature reports. The proportion of fragmented red blood cells in TA-TMA was significantly higher compared to those in aGVHD, and the decrease in the proportion of these fragmented cells can reduce the risk of TA-TMA. The increased proportion of fragmented red blood cells elevated the risk of death of TA-TMA by 80%, which can independently predict TA-TMA, highlighting its close association with the occurrence, development and prognosis of TA-TMA. On the other hand, it is worth noting that although all TA-TMA patients in this study consistently exhibited fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood, a lack such cells does not exclude a priori the diagnosis of TMA, it had been reported that the absence of fragmented red blood cells in patient with TA-TMA had led to a delay diagnosis and treatment (32), emphasizing the importance of fragmented red blood cells combined with specific laboratory tests and comprehensive analysis.

Not only that, the injury to vascular endothelial cells in TA-TMA patients may lead to microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, as well as thrombosis in the microcirculation (33, 34). These adverse effects may subsequently cause ischemic damage to end-organs, particularly the kidneys, as well as the lungs, heart, and gastrointestinal tract. In contrast, the initial phase of aGVHD is characterized by tissue damage mediated through the regulation and release of inflammatory cytokines, primarily affecting three areas: the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and liver (35). Based on the different pathogenesis and the analysis results of this study, we identified five symptoms that are more likely to co-occur with TA-TMA: hypertension, renal injury, cardiac insufficiency, pulmonary infection, and CMV-emia. Additionally, three significantly elevated indicators in TA-TMA patients were identified: proportion of fragmented red blood cells in peripheral blood, serum LDH levels, and serum BUN levels. Two significantly reduced indicators were also noted: red blood cell counts and hemoglobin levels. For grade III-IV aGVHD, TBIL levels were higher and associated with a higher risk of death, and increased serum TBIL was a unique marker of hepatic involvement (35), suggesting that patients with grades III-IV aGVHD are more likely to liver involvement. Although TA-TMA was associated with a higher incidence of hemorrhagic cystitis and urinary occult blood and a reduction in platelet and ALB levels, these indicators were similarly observed in our grade III-IV aGVHD patients, therefore, hemorrhagic cystitis, urinary occult blood, platelets counts, and ALB levels are more significant only when differentiating between TA-TMA and grade I-II aGVHD cases.

Existing studies have reported varying evidence of the prognostic impact of LDH and renal injury in TA-TMA. High baseline LDH level was associated with definite and probable TMA, definite and probable TMA were each independently associated with long-term kidney dysfunction (19), elevated LDH levels, proteinuria on routine urinalysis, and hypertension were the earliest markers of TMA (13). HSCT-TMA was associated with renal dysfunction, renal failure, renal replacement therapy and hypertension (36). Our findings determined that LDH elevation and renal injury were more likely significantly associated with an increased risk of TA-TMA. On this basis, we also noticed that elevated LDH, and renal injury predicted higher mortality for TA-TMA, representing one of the novel findings of this study. This finding is consistent with recent literature indicating that the ASTCT/CIBMTR/EBMT/APBMT consensus risk stratification for pediatric TA-TMA identifies LDH >2 times ULN is one of the most important predictors of nonrelapse mortality of TA-TMA, allowing risk stratification even in the absence of available sC5b-9 testing (37). Although proteinuria is closely related to TA-TMA, our study did not reveal a significant difference in the incidence of proteinuria between TA-TMA and aGVHD, so no further analysis was conducted, considering that proteinuria frequently occurs when aGVHD involves the kidneys. These data suggest that more transplant recipients should be included in our subsequent studies and clinical trials to verify the discriminatory and prognostic value of proteinuria between these two diseases.

A pre-emptive strategy has successfully decreased the incidence of CMV disease after allo-HSCT, however, it is difficult to completely prevent that (38). Positive CMV serostatus is also associated with probable TMA (19), which may act as an independent risk factor for TA-TMA and directly damage microvascular endothelial cells, causing TMA (13, 14). Kraft S’s research showed that CMV reactivation/end-organ disease was a risk factor for development of TA-TMA (5), only a limited number of studies suggested that the risk factors for TA-TMA were not associated with CMV-emia (28). In this study, no significant difference was observed in the CMV positivity rate between TA-TMA and aGVHD prior to transplantation. However, at the time of diagnosis, the CMV positivity rate of TA-TMA was significantly higher than that of aGVHD. Compared to grade I-II and III-IV aGVHD, post-transplant CMV viremia may increase the risk of TA-TMA development and death, although the result was not statistically significant after adjusting for risk variables. Regardless, post-transplant CMV viremia should not be ignored, while considering aGVHD after transplantation, clinicians should be more vigilant for the development of TA-TMA.

Hemoglobin levels, platelet counts, ALB levels were identified as protective factors for the occurrence, development, and prognosis of TA-TMA in our study. Severe anemia and severe thrombocytopenia had been recognized as significant prognostic indicators in a large-scale external validation trial of the TA-TMA prognostic model (39), and our findings are in agreement with the existing literature reports. Furthermore, we found that the levels of hemoglobin and platelets in TA-TMA were significantly lower than those in aGVHD, which has certain clinical value for the differential diagnosis between TA-TMA and aGVHD, and increased hemoglobin and platelet levels can reduce the risk of death for TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD, serving as protective factors against the death for TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD. Notably, platelet levels retained independent prognostic significance for TA-TMA even after adjusting for various risk variables. Although platelets are often at low levels due to the insufficiency of megakaryocyte engraftment in the early stages after allo-HSCT, the onset of TA-TMA typically occurs later than that of aGVHD, so we speculate that it is not difficult to exclude the interference of low platelet levels in the differential diagnosis of TA-TMA and aGVHD at this time, despite the current inability to fully evaluate this hypothesis. Furthermore early post-allo-HSCT studies are warranted to validate the applicability of this finding in contemporary patient cohorts. In addition, ALB has been identified as an independent prognostic factor following allo-HSCT in leukemia patients, capable of predicting long-term outcomes (40). In this study, ALB levels in TA-TMA and grade III-IV aGVHD were significantly lower compared to those in grade I-II aGVHD, and was significantly associated with a reduced risk of mortality in TA-TMA, acting as an independent predictor of favorable prognosis for TA-TMA. Patients with TA-TMA may consume ALB through urinary albumin loss and inflammation. The underlying mechanism is primarily associated with kidney lesions and inflammation resulting from microvascular endothelial injury, while ALB depletion in aGVHD is mainly attributed to protein loss caused by gastrointestinal injury, so in clinical practice, dynamic monitoring of ALB levels should be integrated with other biomarkers for a comprehensive evaluation. Despite limitations of sample size and retrospective design, our exploratory analysis revealed a non-significant trend toward improved survival with complement inhibitor in TA-TMA. Recent studies have demonstrated that complement inhibitors can markedly enhance survival outcomes in both adult and pediatric patients with TA-TMA (3, 41), suggesting a potential survival benefit for high-risk individuals. Prospective studies are urgently needed to definitively establish the efficacy of targeting the complement pathway in high-risk TA-TMA.

To our knowledge, this study provides one of the first comprehensive analyses aimed at differentiating TA-TMA from aGVHD following transplantation. Our findings suggest that fragmented red blood cells, renal injury, and serum LDH levels may serve as independent diagnostic indicators for distinguishing TA-TMA from aGVHD. Furthermore, hemoglobin levels appear to have diagnostic utility in differentiating TA-TMA from severe (grade III-IV) aGVHD. In terms of prognosis, our data provide preliminary evidence that fragmented red blood cells, LDH, and renal injury are associated with an increased risk of mortality, whereas platelet counts and ALB levels may be potential protective factors in TA-TMA patients.

There are some limitations in this study, due to the limited sample size and the large range of screened variables, there is no further analysis of all potentially significant and important indicators. An important aspect of our study design was the comparative analysis of TA-TMA and aGVHD as mutually exclusive groups, despite the established fact that aGVHD is a significant risk factor for TA-TMA development. Our rationale for this approach was pragmatic and aimed at addressing a specific clinical question: at the moment of initial clinical deterioration, which parameters can most effectively help the clinician distinguish whether the primary driver is aGVHD or TA-TMA? We sought to delineate the relatively “pure” clinical profiles of each entity at onset. We acknowledge that this design is a simplification and does not capture the complexity of cases where both entities manifest simultaneously or sequentially. Future dynamic studies should build upon to unravel their complex interplay. In addition, the small sample size and single-center design limit the statistical power and generalizability of our findings. The prognostic outcomes of TA-TMA in this study, particularly the independent prognostic factors identified through multivariate analysis-including schistocytes, lactate dehydrogenase, renal injury, platelets, and albumin should be regarded as exploratory preliminary results. These findings require validation in larger sample sizes and should not be considered definitive independent prognostic factors. The primary value of this study lies in its detailed descriptions and the provision of valuable real-world insights, which offer robust hypotheses for future research.

Based on our findings, we recommend a rapid TA-TMA diagnostic approach using key lab parameters (Hb, fragmented RBCs, LDH, renal injury), alongside monitoring platelets and albumin for risk stratification and renal protection. Future studies should investigate the protective roles of these factors, assess early interventions, and validate the survival benefit of complement blockade in high-risk patients.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University & Henan Cancer Hospital. The patients signed written informed consent to participate in this study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

Y-YW: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft. G-PL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. S-ZF: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. Y-WF: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. YS: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft. Q-XX: Investigation, Resources, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by grants from the Henan Province Young and Middle-aged Talent Plan Project (No. YXKC2022046).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the patients and the co-investigators for their cooperation in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1668243/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Matsui H, Arai Y, Imoto H, Mitsuyoshi T, Tamura N, Kondo T, et al. Risk factors and appropriate therapeutic strategies for thromboticmicroangiopathy after allogeneic HSCT. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:3169–79. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020002007

2. Vivek M, Connelly-Smith L, and Panch S. Incidence, risk association and outcomes of adult transplant associated thrombotic microangiopathy by applying modified jodele criteria-a single center experience. Blood. (2024) 144:7300–0. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-211370

3. Acosta-Medina AA, Sridharan M, Go RS, Moyer AM, Leung N, Willrich MAV, et al. Clinical outcomes and treatment strategies of adult transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: external validation of harmonizing definitions and high-risk criteria. Am J Hematol. (2025) 100:830–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27651

4. Schoettler ML, French K, Harris A, Bryson E, Deeb L, Hudson Z, et al. D-dimer and sinusoidal obstructive syndrome-novel poor prognostic features of thrombotic microangiopathy in children after hematopoietic cellular therapy in a single institution prospective cohort study. Am J Hematol. (2024) 99:370–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.27186

5. Mahmoudjafari Z, Alencar MC, Alexander MD, Johnson DJ, Yeh J, and Evans MD. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy and the role of advanced practice providers and pharmacists. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2023) 58:625–34. doi: 10.1038/s41409-023-01951-3

6. Vasu S, Bostic M, Zhao Q, Sharma N, Puto M, Knight S, et al. BK virus hemorrhagic cystitis and age are risk factors for transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in adults. Blood Adv. (2022) 6:1342–9. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004933

7. Sridharan M, Go R, Shah M, Litzow MR, Hogan WJ, and Alkhateeb HB. Incidence and mortality outcomes in allogeneic transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. (2018) 24:S329–30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.12.387

8. Ruutu T, Hermans J, Niederwieser D, Gratwohl A, Kiehl M, Volin L, et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a survey of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT). Br J Haematol. (2002) 118:1112–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03721.x

9. Ho VT, Cutler C, Carter S, Martin P, Adams R, Horowitz M, et al. Blood and marrow transplant clinical trials network toxicity committee consensus summary: thrombotic microangiopathy after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. (2005) 11:571–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.06.001

10. Ma S, Bhar S, Guffey D, Kim R, Jamil M, Morales M, et al. Prospective clinical and biomarker validation of the ASTCT consensus definition for transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy (TA-TMA). Blood. (2023) 142:4902–2. doi: 10.1182/blood-2023-174143

11. Wall SA, Zhao Q, Yearsley M, Blower L, Agyeman A, Ranganathan P, et al. Complement-mediated thrombotic microangiopathy as a link between endothelial damage and steroid-refractory GVHD. Blood Adv. (2018) 2:2619–28. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018020321

12. Cho BS, Yahng SA, Lee SE, Eom KS, Kim YJ, Kim HJ, et al. Validation of recently proposed consensus criteria for thrombotic microangiopathy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation. (2010) 90:918–26. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f24e8d

13. Jodele S, Davies SM, Lane A, Khoury J, Dandoy C, and Goebel J. et al, Diagnostic and risk criteria for HSCT-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a study in children and young adults. Blood. (2014) 124:645–53. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-564997

14. Jodele S, Dandoy CE, Lane A, Laskin BL, Teusink-Cross A, Myers KC, et al. Complement blockade for TA-TMA: lessons learned from a large pediatric cohort treated with eculizumab. Blood. (2020) 135:1049–57. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019004218

15. Schoemans HM, Lee SJ, Ferrara JL, Wolff D, Levine JE, Schultz KR, et al. EBMT-NIH-CIBMTR Task Force position statement on standardized terminology & guidance for graft-versus-host disease assessment. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2018) 53:1401–15. doi: 10.1038/s41409-018-0204-7

16. Epperla N, Li A, Logan B, Fretham C, Chhabra S, Aljurf M, et al. Risk factors for and outcomes of transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Br J Haematol. (2020) 189:1171–81. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16457

17. Nangia U, Metheny L, and Mahajan N. Effect of age, timing of thrombotic microangiopathy and timing of acute graft-versus-host disease on overall survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2025) 144:3530–0. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-202240

18. Nangia U, Metheny L, and Mahajan N. Impact of timing of acute graft-versus-host-disease on incidence of thrombotic microangiopathy after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. (2024) 144:1241–1. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-202257

19. Postalcioglu M, Kim HT, Obut F, Yilmam OA, Yang J, Byun BC, et al. Impact of thrombotic microangiopathy on renal outcomes and survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. (2018) 24:2344–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.05.010

20. Labrador J, López-Corral L, López-Godino O, Vázquez L, Cabrero-Calvo M, Pérez-López R, et al. Risk factors for thrombotic microangiopathy in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell recipients receiving GVHD prophylaxis with tacrolimus plus MTX or sirolimus. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2014) 49:684–90. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2014.17

21. Shayani S, Palmer J, Stiller T, Liu X, Thomas SH, Khuu T, et al. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with sirolimus level after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with tacrolimus/sirolimus-based graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. (2013) 19:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2012.10.006

22. Nakamae H, Yamane T, Hasegawa T, Nakamae M, Terada Y, Hagihara K, et al. Risk factor analysis for thrombotic microangiopathy after reduced-intensity or myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Am J Hematol. (2006) 81:525–31. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20648

23. Uderzo C, Bonanomi S, Busca A, Renoldi M, Ferrari P, Iacobelli M, et al. Risk factors and severe outcome in thrombotic microangiopathy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Transplantation. (2006) 82:638–44. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000230373.82376.46

24. Willems E, Baron F, Seidel L, Frère P, Fillet G, and Beguin Y. Comparison of thrombotic microangiopathy after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation with high-dose or nonmyeloablative conditioning. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2010) 45:689–93. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.230

25. Nangia U, Metheny L, and Mahajan N. Risk factors for thrombotic microangiopathy after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation by disease groups in competing risk analysis. Blood. (2024) 144:1239–39. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-202248

26. Elfeky R, Lucchini G, Lum SH, Ottaviano G, Builes N, Nademi Z, et al. New insights into risk factors for transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in pediatric HSCT. Blood Adv. (2020) 4:2418–29. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001315

27. Saliba R, Aljawai Y, Alousi A, Oran B, Popat U, Champlin R, et al. Predictors of graft-versus-host disease with post-transplant cyclophosphamide. Blood. (2024) 144:4890–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2024-210660

28. El Fakih R, Kotb A, Hashmi S, Chaudhri N, Alsharif F, Shaheen M, et al. Outcomes of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant for acute myeloid leukemia in adolescent patients. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2020) 55:182–8. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0667-1

29. Asensi Cantó P, Gómez-Seguí I, Montoro J, Villalba Montaner M, Chorão P, Solves Alcaína P, et al. Incidence, risk factors and therapy response of acute graft-versus-host disease after myeloablative hematopoietic stem cell transplantation with posttransplant cyclophosphamide. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2024) 59:1577–84. doi: 10.1038/s41409-024-02391-3

30. Huh HJ, Chung JW, and Chae SL. Microscopic schistocyte determination according to International Council for Standardization in Hematology recommendations in various diseases. Int J Lab Hematol. (2013) 35:542–7. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.12059

31. Zini G, d’Onofrio G, Erber WN, Lee SH, Nagai Y, and Basak GW. 2021 update of the 2012 ICSH Recommendations for identification, diagnostic value, and quantitation of schistocytes: Impact and revisions. Int J Lab Hematol. (2021) 43:1264–71. doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13682

32. Murphree CR, Nguyen NN, Shatzel JJ, Olson SR, Chung PD, and Lockridge JB. Biopsy-proven thrombotic microangiopathy without schistocytosis on peripheral blood smear: A cautionary tale. Am J Hematol. (2019) 94:E234–7. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25551

33. Khosla J, Yeh AC, Spitzer TR, and Dey BR. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: current paradigm and novel therapies. Bone Marrow Transpl. (2018) 53:129–37. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2017.207

34. Rosenthal J. Hematopoietic cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy: a review of pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Blood Med. (2016) 7:181–6. doi: 10.2147/JBM.S102235

35. Olivieri A and Mancini G. Current approaches for the prevention and treatment of acute and chronic GVHD. Cells. (2024) 13:1524. doi: 10.3390/cells13181524

36. Dandoy CE, Tsong WH, Sarikonda K, McGarvey N, and Perales MA. Systematic review of signs and symptoms associated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Transplant Cell Ther. (2023) 29:282.e1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2022.12.023

37. Schoettler ML, Ofori J, Bryson E, Spencer K, Qayed M, Stenger E, et al. Real-world application of recently proposed ASTCT/CIBMTR/EBMT/APBMT consensus risk stratification for transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy in children. Transplant Cell Ther. (2024) 30:929.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtct.2024.06.017

38. Akahoshi Y, Kimura S, Tada Y, Matsukawa T, Tamaki M, Doki N, et al. Cytomegalovirus gastroenteritis in patients with acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. (2021) 138:3918–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2021-147658

39. Zhao P, Wu YJ, He Y, Chong S, Qu QY, Deng RX, et al. A prognostic model (BATAP) with external validation for patients with transplant-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood Adv. (2021) 5:5479–89. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004530

40. Drokov M, Popova N, Vasilyeva V, Mikhaltsova E, Koroleva O, Konova Z, et al. Serum Albumin Level, but Not Nutritional Risk Index Predicts Outcomes in Acute Leukemia Patients after Allo-HSCT. Blood. (2019) 134:1987–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-126822

Keywords: clinical differential analysis, severe complications, thrombotic microangiopathy, acute graft-versus-host disease, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Citation: Wang Y-y, Li G-p, Fu S-z, Fu Y-w, Shen Y and Xu Q-x (2025) Clinical differential analysis of severe complications thrombotic microangiopathy and acute graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Front. Oncol. 15:1668243. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1668243

Received: 17 July 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Revised: 17 November 2025;

Published: 08 December 2025.

Edited by:

Meng Lv, Peking University People’s Hospital, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Wang, Li, Fu, Fu, Shen and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gang-ping Li, bGdwODYxMTI2QDE2My5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Yuan-yuan Wang

Yuan-yuan Wang Gang-ping Li

Gang-ping Li Shu-zhen Fu1

Shu-zhen Fu1