Abstract

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) remains a major global health challenge, with limited long-term survival in the recurrent/metastatic (R/M) setting. Here, we present a rare case of a patient with metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma who survived eight years after diagnosis of metastatic disease, treated only with standard chemotherapy, metastasectomy, and palliative radiotherapy. To explore potential genomic underpinnings of this unusually favorable outcome, we performed next-generation sequencing of tumor (lymph node and lung metastases) and germline DNA. Mutations were analyzed across ten key oncogenic signaling pathways and compared with the COSMIC and OncoKB databases. Somatic mutations were found in all ten pathways, with multiple 3′ UTR variants in EIF4EBP1 and CTBP2, genes implicated in translational regulation and transcriptional repression, respectively. Germline analysis revealed 21 high-impact mutations, three of which were rare and potentially deleterious. Our findings suggest that subtle regulatory variants may contribute to favorable clinical outcomes in rare long-term survivors of R/M HNSCC. Further studies are needed to identify predictive biomarkers in this unique subgroup of patients.

Introduction

Head and neck cancer (HNC) ranks as the seventh most common cancer globally, accounting for more than 890,000 new cases and 450,000 deaths annually (1). Approximately 90% of HNCs are squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), that arise from the epithelial lining of the oral cavity, pharynx and larynx (2). Laryngeal cancer accounts for almost 25-30% of all HNCs. At diagnosis, nearly half of patients present with locoregionally advanced disease, and approximately 50% will experience relapse after primary treatment with distant metastases and/or local or regional disease (3). Synchronous distant metastases occur in up to 15% of patients (3), with the lungs being the most common site, accounting for two-thirds of all distant metastases (4).

The prognosis of patients with recurrent or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC) is generally poor. Surgery and/or radiotherapy is possible in 20% of patients while the majority of them are treated with systemic treatment. Since 2008, the addition of cetuximab to platinum based chemotherapy in the first line therapy as well as the implementation of pembrolizumab and nivolumab in the second line therapy, and finally the use of pembrolizumab alone or in combination with chemotherapy in programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) positive tumors in the first line therapy have improved the survival of these patients (5–8). In spite of that, the best median survival is no longer than 15 months depending on patient- and tumor- related factors. Furthermore, spatial and temporal tumor heterogeneity has been well recognized (9). New effective treatment options are needed to further improve treatment outcomes.

Nonetheless, rare long-term survivors exist even among patients treated with chemotherapy alone. In the control arms of the EXTREME (5) and ECOG-ACRIN E1305 (10) trials, a small proportion of patients (0.9% and 1.5%, respectively) survived five years or longer. Although the biology of their disease already proved the aggressiveness by the formation of metastases and relapses they had somehow better outcome than other patients. These outliers raise the question: is their survival merely an anomaly, or do they represent a unique prognostic subgroup of R/M HNSCC patients who may benefit from less intensive treatment? If so, how to recognize them?

Here, we report the case of a patient with metastatic laryngeal SCC who survived for eight years following diagnosis of metastatic disease, despite receiving only standard chemotherapy without targeted therapy or immunotherapy. We performed genomic profiling on lymph node and lung metastases, along with germline DNA analysis, aligning our findings with cancer-associated genes catalogued in the COSMIC (11) and OncoKB (12, 13) databases. Additionally, mutations were mapped onto ten key oncogenic signaling pathways (14).

Materials and methods

Germline DNA was extracted from whole blood using Nucleon spin blood kit (Merchey-Nagel). DNA from paraffin was extracted using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The purity of the FFPE samples was assessed by a pathologist from H&E-stained slides and both samples were of sufficient quality. Whole genome sequencing was performed in commercial facility as follows: libraries were constructed using Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free kit and TruSeq Nano DNA Sample Preparation Kit. Sequencing was performed on Illumina HiSeq sequencing system. The raw images and base calling were generated on Illumina Platform. Phred quality scores were as follows genomic DNA: Q20: 97.8%, Q30: 96.5%; lung metastasis: Q20: 97.5%, Q30: 94.0%; lymph node: Q20: 96.7%, Q30: 92.2%. Coverage depth metrics revealed that over 99.5% of bases were covered at least 1X across all samples, with approximately 88%, 65%, and 46% reaching 30X coverage in the genomic, lung metastasis and lymph node samples, respectively. Data quality and coverage uniformity were evaluated to ensure suitability for downstream variant analysis. Paired-end sequences were mapped to the human genome using Isaac aligner (iSAAC-04.18.11.09) where the reference sequence is GRCh38 (NCBI, Dec. 2013). Strelka 2.9.10 (15) was used to identify single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and short insertions and deletions (Indels). The gvcftools, was used to generate Variant-only VCF. Variants were annotated using SnpEff v4.3 (16). SnpEff is applied to annotate the VCF file with additional databases, including ESP6500, ClinVar (17) and dbNSFP3.5 (18, 19). Somatic mutations from tumor-germline sample pairs were confirmed using VarScan (Galaxy Version 2.4.3.6) (20, 21). Variants identified by both callers were classified as confirmed. Each discrepant variant in the investigated genes was manually inspected using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Cancer consensus genes listed in Cosmic database, genes from cancer gene list in OncoKB database and genes from oncogenic signaling pathways (14) were extracted from VCF file and presented in this paper. Results presented in this paper are achieved from have high quality reads.

Case description

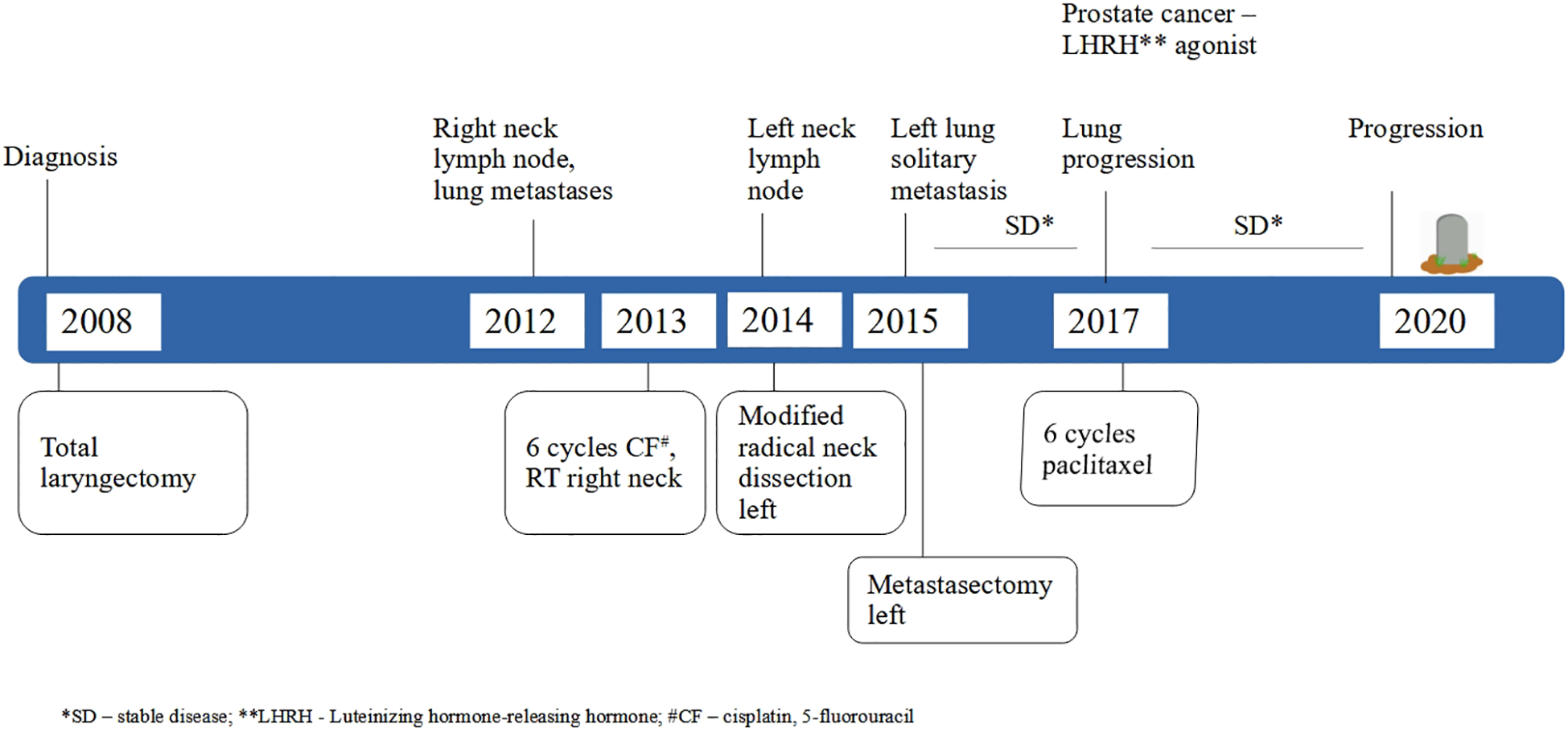

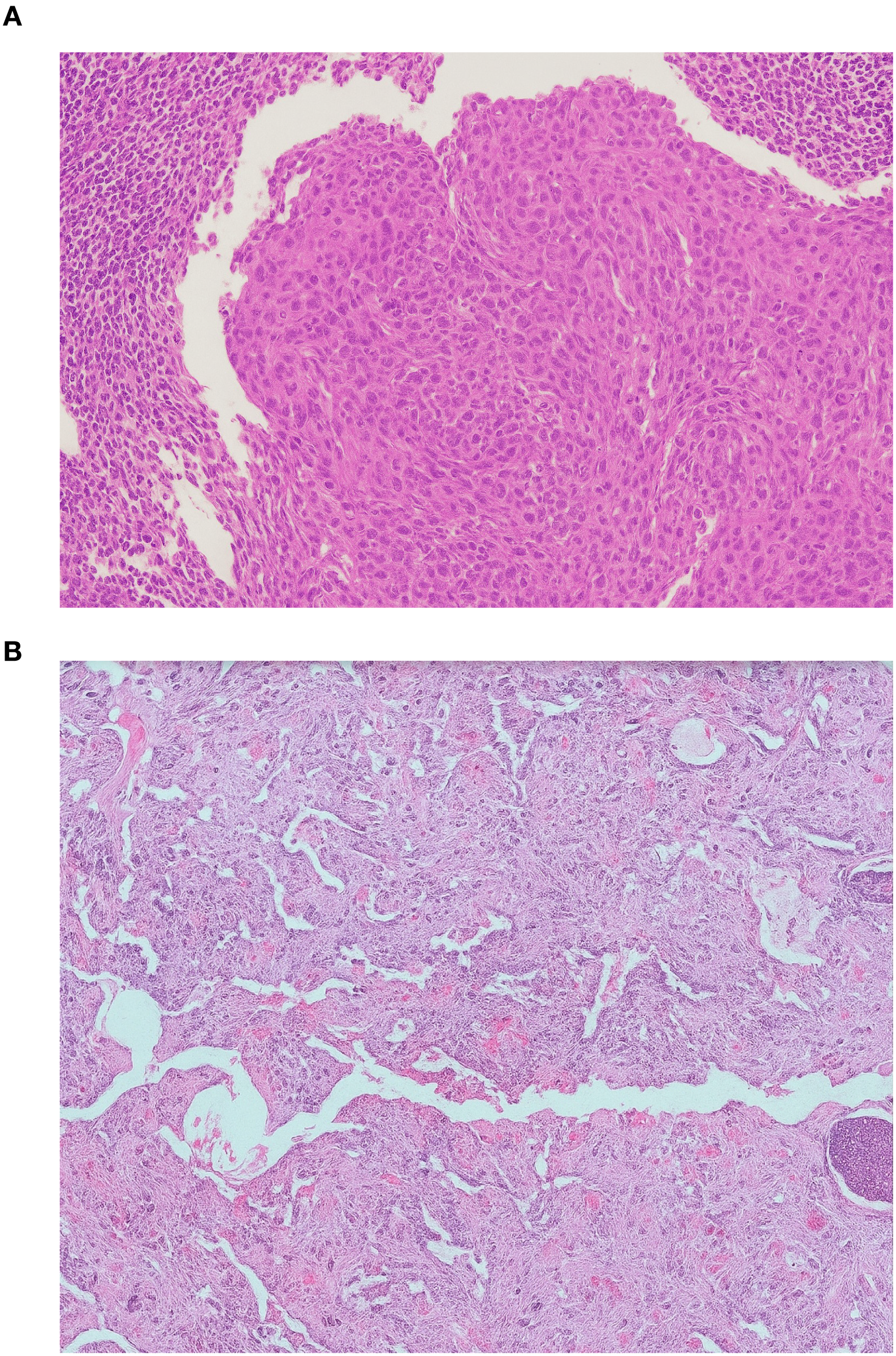

A 46-year-old patient, a long-term smoker, presented to the ENT clinic in January 2008 with a two months of dysphonia. Laryngoscopic examination and neck computed tomography (CT) revealed a glottic tumor extending into the subglottic region, without evidence of cervical lymphadenopathy. The tumor was staged as cT2cN0cM0 (Figure 1). His medical history was notable only for previous tuberculosis. Total laryngectomy was performed. Histological analysis confirmed SCC, pT2NxMx, without adverse pathological features. The patient remained in regular follow-up without signs of recurrence until November 2012, when a palpable, painless mass was detected in the right level II neck region. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) confirmed a right cervical mass measuring 2.3 x 2.2 cm, along with a solitary 1.2 cm lesion in the left upper lung lobe and a suspicious 1.5 cm nodule in the right upper lung lobe. Cytological examination of the cervical lymph node revealed SCC. From a differential diagnostic perspective, in addition to metastases from laryngeal carcinoma, a second primary lung tumor with metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes was also considered. Although metastases from a primary lung tumor are more commonly found in the supraclavicular region than in level II cervical nodes, this possibility was taken into account. Bronchoscopy did not reveal any malignant cells, and a transthoracic biopsy of the pulmonary lesion was not performed. From March to August 2013, the patient received 6 cycles of chemotherapy consisting of cisplatin 100 mg/m2 and 5-fluorouracil 1000 mg/m2 every 3 weeks. Follow-up CT imaging of the neck and chest showed stable pulmonary lesions but further enlargement of the cervical lymph node, without new metastases. In December 2013, palliative radiotherapy to the right neck was administered using 6 MV photon beams delivered by a Primus Plus linear accelerator (Siemens, Germany), equipped with an 82-leaf multileaf collimator (MLC). Total dose of 30 Gy was given in 10 fractions over two weeks. In January 2014, follow-up imaging showed significant regression of the right cervical lymph node, now 8 x 8 mm, while the right pulmonary nodule remained unchanged and the left pulmonary nodule was no longer visible. In March 2014, PET/CT revealed a solitary suspicious lymph node in the left level II neck region, without other signs of active disease. Cytology confirmed SCC. In May 2014, a modified radical neck dissection was performed, preserving the XI cranial nerve and internal jugular vein. Of 22 resected lymph nodes, one was positive for malignancy (Figure 2A). In October 2014, CT imaging once again identified a 14 x 12 mm nodule in the left upper lung lobe and an 8 x 8 mm necrotic lymph node in the left level II neck. PET/CT showed the pulmonary nodule as the sole site of active disease. Given the patient’s good general condition (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status 0), a pulmonary metastasectomy was performed in January 2015. Histopathological examination revealed a 1 cm tumor nodule composed of cells that were strongly positive for CK5/6 and negative for TTF-1 on immunohistochemistry. The tumor was located at one margin of the resection (Figure 2B). Although it is challenging to histologically distinguish a metastatic laryngeal SCC in the lung from a primary pulmonary SCC, as both share similar morphological features, the clinical history, radiologic findings, and immunohistochemistry in this case supported the conclusion that the pulmonary lesions represented metastases from the laryngeal carcinoma. No clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence was observed until February 2017, when PET/CT detected progression in the left lung. An incidental focal radiotracer uptake in the prostate prompted biopsy, confirming prostate adenocarcinoma with a Gleason score 4 + 4 = 8. At diagnosis, the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was 6.78 μg/l. Androgen deprivation therapy with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists was initiated in April 2017. According to the available literature, there is no known etiological or molecular link between laryngeal SCC and prostate adenocarcinoma. Thus, the simultaneous occurrence of these two tumor types in this patient likely reflected the independent development of two distinct malignancies with different risk factors. Due to progression of pulmonary metastases, the patient received 6 cycles of paclitaxel 175 mg/2 every 3 weeks from May to September 2017. Imaging showed stable disease with no significant progression. Prostate cancer remained well-controlled with PSA nadir < 0.01μg/l by January 2018. The patient tolerated the treatment well, experiencing no adverse effects other than occasional fatigue and showed good adherence to the therapy schedule. No dose modifications of chemotherapy were required, likely due to the relatively short duration of therapy, which was never longer than six consecutive months and included treatment-free intervals. The patient maintained a good quality of life until early 2018 and remained generally optimistic, although some concern arose with disease relapse. Despite radiological stability of the lung metastases and consistently low PSA levels, the patient’s general condition gradually declined starting in early 2018. Regular follow-up was continued with CT imaging, laboratory tests, and clinical examinations every four months. In November 2020, CT imaging revealed widespread metastatic disease, including new lesions in the lung, liver, cervical, mediastinal and retroperitoneal lymph nodes as well as osteolytic bone metastases. PSA had risen to 6.70 μg/l and the patient’s performance status deteriorated to ECOG 4. He died on December 14, 2020, eight years following the diagnosis of metastatic laryngeal disease.

Figure 1

Timeline of the patient’s clinical course.

Figure 2

Histopathological features of metastatic laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. (A) Cervical lymph node metastasis showing nests of atypical squamous epithelial cells with keratinization and intercellular bridges. (B) Lung metastasis displaying similar morphological characteristics confirming metastatic squamous cell carcinoma (hematoxylin and eosin stain, ×200).

We performed next generation sequencing on tumor (lymph node and lung) and germline DNA from described patient. In this paper we analyzed only single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions and deletions (INDELs). The putative impact of genetic variants was categorized into four predefined impact levels based on their predicted effect on protein function, as determined by SnpEff. High-impact variants cause disruptive changes such as frameshifts, stop codon gains or losses, or splice site disruptions that are likely to severely affect protein function. Moderate-impact variants include non-synonymous changes such as amino acid substitutions or in-frame insertions/deletions that may alter protein function but are less likely to be fully disruptive. Low-impact variants are typically synonymous changes that do not alter the amino acid sequence and are expected to have minimal or no effect on protein function. MODIFIER-impact variants are generally located in non-coding regions or upstream/downstream regions where the functional consequences are less clear or indirect. Highimpact variants were further cross-checked against population frequency data from gnomAD, and for variants with low population frequency, pathogenicity was assessed using online resources including MutationMapper at cBioPortal and in silico predictors available on gnomAD.

Somatic mutations in oncogenic signaling pathways

Since genetic alterations in signaling pathways that control cell-cycle progression, apoptosis, and cell growth are common hallmarks of cancer we analyzed oncogenic signaling pathways (cell cycle, Hippo, Myc, Notch, Nrf2, PI-3-Kinase/Akt, RTK-RAS, TGFβ signaling, p53 and β-catenin/WNT) comprising a total of 266 genes (14), in both tumor and germline DNA. Table 1 summarizes the mutated genes identified in the lymph node and lung metastases, along with the corresponding mutation types. Somatic mutations were found in all 10 oncogenic signaling pathways. Lymph node sample harbored 35 mutations across 19 genes, including 11 mutations in EIF4EBP1 (Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1). The lung metastasis sample contained 39 mutations in 31 genes with 3 mutations in CTBP2 (C-Terminal Binding Protein 2). Two mutations, one in MXI1 and one in PIK3R2, belonging to the MYC and PI3K pathways, respectively, were shared between both tumor samples. We compared our data with a curated set of non-redundant studies in cBioPortal (22–24) for cancer genomics (80085 samples) and found four identical mutations but none of them were observed in HNC samples within the database. Putative impact of all but one mutation was unknown, low or moderate.

Table 1

| Signal pathway | Gene | Samples | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymph nodes | Lung metastasis | ||||

| Cell Cycle | CDK2 | 1 | |||

| CDKN2C | 1 | ||||

| HIPPO | DCHS2 | 1 | |||

| HIPK2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| LIMD1 | 2 | ||||

| MOB1B | 1 | 1 | |||

| PTPN14 | 1 | ||||

| TAOK1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| TAOK2 | 1 | ||||

| WTIP | 2 | 1 | |||

| WWC1 | 1 | ||||

| MYC | MAX | 2 | |||

| MXI1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| NOTCH | CNTN6 | 1 | |||

| CTBP2 | 3 | ||||

| DLK1 | 1 | ||||

| DLL3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| HES2 | 1 | ||||

| HEY1 | 1 | ||||

| HEYL | 1 | ||||

| MAML3 | 1 | ||||

| NUMB | 1 | ||||

| PSENEN | 1 | ||||

| FBXW7 | 1 | ||||

| ADAM17 | 1 | ||||

| NRF2 | CUL3 | 1 | |||

| NFE2L2 | 2 | ||||

| PI3K | AKT1S1 | 1 | |||

| EIF4EBP1 | 11 | ||||

| PIK3R2 | 2 | 1 | |||

| TSC1 | 1 | ||||

| RTK RAS | IRS2 | 1 | |||

| KSR2 | 1 | ||||

| PIN1 | 1 | ||||

| TFK-β | SMAD2 | 1 | |||

| TP53 | MDM4 | 3 | |||

| TP53 | 1 | ||||

| WNT | AMER1 | 1 | |||

| FZD1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| FZD3 | 1 | ||||

| LZTR1 | 1 | ||||

| TLE3 | 1 | ||||

| WNT4 | 1 | ||||

| DKK1 | 1 | ||||

Somatic mutation distribution in signal pathway genes.

5_prime_UTR_variant

5_prime_UTR_premature_start_codon_gain_variant

synonymous_variant

missense_variant

missense_variant&splice_region_variant

splice_region_variant&non_coding_transcript_exon_variant

3_prime_UTR_variant

Germline variants in oncogenic signaling pathways

In Germline DNA, we identified 21 high impact mutations in genes from the analyzed oncogenic signaling pathways, all of which have been previously reported (Supplementary Table S1). Notably, only three of the 21 variants had a population frequency below 1%, making them potentially deleterious (25). One such rare, high impact variant, rs774201781, is an in-frame deletion or intronic variant in the MLL3 gene, found in the germline sample in heterozygous form. This variant has a population frequency of 0.0335% in individuals of European ancestry (26), and has recently been associated with Lynch syndrome in a Chinese family (27). Another high impact mutation is a synonymous mutation in LGR5 which is characterized as a structural interaction variant (rs140637499). Although silent mutations were historically considered functionally irrelevant, emerging evidence suggests they may influence transcription and translation in various ways (28). The third high impact germline mutation was found in TP53, gene not only involved in one of the analyzed signaling pathways but also among the most extensively studied genes in cancer biology.

Somatic and germline variants in consensus cancer genes

Furthermore, we searched somatic and germline variants in genes listed as cancer consensus genes in the COSMIC database and in the OncoKB cancer gene database. In germline DNA, 23 high-impact mutations were identified but most of these were common variants according to gnomAD population frequency data (26). Only three were rare: two frameshift mutations in SERPINB3 (rs60533853 and rs201374310), each with a population frequency of ~1%, and one rare variant in ASMTL (chrX:1418076), present in only four samples in the gnomAD database. According to the CADD in silico predictor, this variant is likely deleterious (29). In tumor DNA, a high-impact mutation in a cancer consensus gene was identified in the SH2B3 gene in the lymph node sample. This T>C transition at position 12:111447546 is a splice donor variant found in a heterozygous state and is predicted to be moderately pathogenic by CADD.

The lung metastasis sample contained high-impact mutations in four cancer-related genes. Among them, variants in RAD51B (rs751355274), IRF8 (rs903202), and SYK (rs35758162) were found to be common in the general population (e.g. gnomAD database) and therefore are unlikely to be deleterious. One rare mutation was detected in FOLH1 (rs79155991) reported in six samples in cBioPortal but not in any HNC cases. ClinVar classifies it as benign. Another mutation, in FGFR3 (rs587777857), was identified in one colon adenocarcinoma sample in cBioPortal and is predicted to be moderately benign by CADD.

According to Malone and Siu (30), the most frequently mutated genes in head and neck cancers include TP53, CDKN2A, PIK3CA, KMT2D, NOTCH1, and FAT1. Supplementary Figure S1 shows the mutation positions in these genes across germline, lymph node, and lung metastasis samples.

Discussion

Despite recent treatment advances in R/M HNSCC, survival has lagged behind other tumor sites, with only 15–23.9% of patients alive at five years (5–8, 31). Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated considerable variability in treatment and survival outcomes for recurrent/metastatic HNSCC in real-world settings (32), largely due to regulatory and reimbursement limitations, as well as restricted access to certain therapies.

At the time of our patient’s metastatic diagnosis in 2012, cetuximab was not available for advanced HNSCC treatment in Croatia, nor were immunotherapy or advanced radiotherapy techniques such as stereotactic radiotherapy. Consequently, the patient received only standard chemotherapy, supplemented by metastasectomy and palliative radiation when appropriate.

Despite the suboptimal systemic treatment, several clinical factors likely contributed to the patient’s prolonged survival. Notably, the patient presented with oligometastatic disease at the time of R/M diagnosis, an intermediate disease state between localized and widespread metastases, associated with improved survival outcomes (4). Additionally, metastatic disease was diagnosed four years after initial treatment of the primary tumor, a longer interval than typically expected (33). However, despite the early stage at initial diagnosis and generally low relapse risk, the patient still experienced disease recurrence.

Whole genome sequencing data provided valuable insights into genomic alterations associated with tumor samples from lymph node and lung metastases in comparison to the patient’s germline DNA. Focusing on SNPs and small INDELs we concentrated our analysis on key oncogenic signaling pathways known to play critical roles in cancer biology (14). In line with previous reports, mutations were detected across all ten analyzed pathways, reinforcing the ubiquity of such alterations in tumorigenesis.

The lymph node sample exhibited a total of 35 mutations across 19 genes with a striking prevalence of 11 mutations in the EIF4EBP1 gene. It plays a crucial role in the regulation of protein synthesis, which can impact various cellular processes, including cell growth and proliferation. In HNC, EIF4EBP1 is particularly relevant due to its inhibition of eIF4E, a key translation initiation factor. Phosphorylation of EIF4EBP1 releases eIF4E, facilitating oncogenic protein synthesis. In cancer, especially HNSCC, this mechanism can contribute to the overexpression of oncogenic proteins (34). Huang et al. (35) suggested that the expression of eIF4E and p-4EBP1 should be considered as predictive biomarkers for the HNSCC patients. All 11 mutations in this gene were located in the 3′ untranslated region (3′ UTR), which may affect post-transcriptional regulation.

In the lung metastasis sample the most frequently mutated gene was CTBP2 with four mutations also located in the 3′ UTR. CTBP2 functions as a transcriptional corepressor that interacts with transcription factors and chromatin-modifying complexes, primarily acting to repress tumor suppressor genes and those involved in differentiation, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation. While no studies have specifically focused on EIF4EBP1 or CTPB2 3’ UTR variants in HNSCC, the general role of 3’ UTR variants in cancer suggests they could affect the function of these genes. Variants in the 3’ UTR of other genes have been shown to disrupt regulatory elements such as microRNA binding sites, alter transcript stability, or change mRNA localization, potentially leading to altered protein expression or function. Recent findings also suggest that 3′ UTR variants can influence mRNA abundance post-transcriptionally (36). Overall, mutations in cancer signaling pathways were predominantly located in the 3′ UTR and included other splice-related variants.

Analysis of the germline genome revealed 21 high-impact mutations in cancer signaling pathway genes. Only three of these variants were rare and potentially deleterious. One such mutation is an in-frame deletion in MAML3, a transcriptional coactivator involved in the Notch signaling pathway (37). This variant has been associated with Lynch syndrome in a recent study (27), underscoring the need to monitor rare germline variants linked to hereditary cancer risk. While functional validation is required, such findings support the value of integrating germline data into cancer profiling. Although direct connections between germline and somatic mutations could not be established in this case, growing evidence suggests that the interplay between germline and somatic variants contributes significantly to tumor development (38).

Comprehensive cancer genome sequencing studies have shown that most cancers contain a small number of frequently mutated well-known oncogenes and tumor suppressors (such as p53 and PIK3CA), alongside a larger pool of less frequent, unique mutations. Every individual carries numerous germline variants, both common and rare, that may affect gene function, influence disease susceptibility, and contribute to the heritability of cancer. While a subset of cancers can be attributed to high penetrance germline mutations, the majority arise in the absence of such variants (39). In our analysis of cancer consensus genes from the Cosmic and OncoKB databases, we identified several high-impact mutations. Most were common variants, but rare mutations were found in SERPINB3 and ASMTL, meriting further investigation. High impact somatic mutations were detected in the lymph node sample in MSH2, OMD, and SH2B3. These mutations are predicted to be pathogenic, although they are not well-characterized in current databases. In contrast, the lung metastasis sample exhibited high impact mutations in RAD51B, IRF8, and SYK, all of which are common in the general population and thus less likely to be deleterious. Notably, methylation of RAD51B has been associated with immune checkpoint expression and inflammatory signatures in HNSCC (40), and SYK is recognized as a downstream effector of EGFR signaling implicated in HNSCC development (35). A rare mutation was also identified in FOLH1, though it is currently classified as benign in ClinVar.

We also compared germline and somatic mutations in genes most frequently altered in HNSCC. Interestingly, these genes harbored more germline than somatic mutations. Somatic TP53 mutation C176S occurs within its DNA-binding domain (41). This variant is associated with increased protein stability (42), it impairs p21 induction and disrupts disulfide-dependent complex formation, leading to predicted loss of TP53 function (43). The germline variant P72R is a common polymorphism located within the regions of TP53 that interact with CCAR2, HRMT1L2, and WWOX (44). Previous studies have reported a lower frequency of TP53 mutations in metastases compared to the primary HNC (45, 46).

Although most research has focused on identifying mutations that lead to cancer, studies on long-term cancer survivors are much rarer. Bowell et al. (47) have found that specific combinations of germline and somatic gene alterations, tumor cell phenotypes, and differential immune responses appear to contribute to long-term survival in high-grade serous ovarian cancers. Similar studies in log-term HNSCC survivors could provide insights into individual risks profiles and tumor behaviors, and the present case would be a valuable example to include in such an investigation.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare but significant occurrence of long-term survival in a patient with metastatic laryngeal SCC treated solely with conventional chemotherapy, surgery, and palliative radiotherapy. Despite the absence of targeted therapy or immunotherapy, the patient achieved an exceptional overall survival of eight years from the onset of metastatic disease. Our genomic analysis revealed diverse somatic and germline alterations across multiple oncogenic signaling pathways, including frequent 3′ UTR mutations in EIF4EBP1 and CTBP2, and rare germline mutations with potential deleterious effects. These findings support the hypothesis that unique molecular features may underlie unusually favorable outcomes in a subset of patients with R/M HNSCC. Further research is warranted to investigate the functional relevance of these alterations and to explore whether they may serve as biomarkers for prognosis or treatment de-escalation in selected individuals.

Statements

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available beceause they are part of ongoing research. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to MPS (mpericic@inantro.hr).

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by The Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Center Zagreb (No 02/013 AG). The patient provided written informed consent for blood collection for the purpose of germline analysis. The patient’s wife provided written consent for publication of the case report. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

VB: Formal Analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MS: Formal Analysis, Writing – review & editing. AŠ: Writing – review & editing, Resources. SS: Resources, Writing – review & editing. MP: Formal Analysis, Writing – original draft, Resources, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by European Union - NextGenerationEU through Institute for Anthropological Research's grant Individual scientific career development (20250064) to MPS. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient’s wife for providing her consent for the publication of this case report.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1691802/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Bray F Laversanne M Sung H Ferlay J Siegel RL Soerjomataram I et al . Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J Clin. (2024) 74:229–63. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834

2

Johnson DE Burtness B Leemans CR Lui VWY Bauman JE Grandis JR . Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2020) 6:92. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3

3

Mastronikolis NS Delides A Kyrodimos E Piperigkou Z Spyropoulou D Giotakis E et al . Insights into metastatic roadmap of head and neck cancer squamous cell carcinoma based on clinical, histopathological and molecular profiles. Mol Biol Rep. (2024) 51:597. doi: 10.1007/s11033-024-09476-8

4

Tonneau M Nebbache R Larnaudie A Thureau S Pointreau Y Blanchard P et al . Management of head and neck carcinomas with synchronous or metachronous oligometastatic disease: Role of locoregional radiotherapy and metastasis-directed radiotherapy. Cancer Radiother. (2024) 28:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2023.03.004

5

Vermorken JB Mesia R Rivera F Remenar E Kawecki A Rottey S et al . Platinum-based chemotherapy plus cetuximab in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. (2008) 359:1116–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802656

6

Ferris RL Blumenschein G Jr. Fayette J Guigay J Colevas AD Licitra L et al . Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. (2016) 375:1856–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252

7

Cohen EEW Soulieres D Le Tourneau C Dinis J Licitra L Ahn MJ et al . Pembrolizumab versus methotrexate, docetaxel, or cetuximab for recurrent or metastatic head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-040): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. (2019) 393:156–67. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31999-8

8

Burtness B Harrington KJ Greil R Soulieres D Tahara M de Castro G Jr. et al . Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. (2019) 394:1915–28. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7

9

Dagogo-Jack I Shaw AT . Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166

10

Argiris A Flamand Y Savvides P Johnson JM Vathiotis I Levine M et al . A new prognostic model in chemotherapy-treated patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck cancer: An analysis of ECOG-ACRIN E1305. Eur J Cancer. (2024) 199:113509. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113509

11

Sondka Z Dhir NB Carvalho-Silva D Jupe S Madhumita McLaren K et al . COSMIC: a curated database of somatic variants and clinical data for cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. (2024) 52:D1210–D7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad986

12

Suehnholz SP Nissan MH Zhang H Kundra R Nandakumar S Lu C et al . Quantifying the expanding landscape of clinical actionability for patients with cancer. Cancer Discovery. (2024) 14:49–65. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-0467

13

Chakravarty D Gao J Phillips S Kundra R Zhang H Wang J et al . OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precis Oncol. (2017) 1):1–16. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00011

14

Sanchez-Vega F Mina M Armenia J Chatila WK Luna A La KC et al . Oncogenic signaling pathways in the cancer genome atlas. Cell. (2018) 173:321–37 e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.035

15

Kim S Scheffler K Halpern AL Bekritsky MA Noh E Källberg M et al . Strelka2: fast and accurate calling of germline and somatic variants. Nat Methods. (2018) 15:591–4. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0051-x

16

Cingolani P Platts A Wang le L Coon M Nguyen T Wang L et al . A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. (2012) 6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695

17

Landrum MJ Lee JM Riley GR Jang W Rubinstein WS Church DM et al . ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. (2014) 42:D980–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113

18

Liu X Jian X Boerwinkle E . dbNSFP: a lightweight database of human nonsynonymous SNPs and their functional predictions. Hum mutation. (2011) 32:894–9. doi: 10.1002/humu.21517

19

Liu X Wu C Li C Boerwinkle E . dbNSFP v3.0: A one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum Mutat. (2016) 37:235–41. doi: 10.1002/humu.22932

20

Koboldt DC Zhang Q Larson DE Shen D McLellan MD Lin L et al . VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res. (2012) 22:568–76. doi: 10.1101/gr.129684.111

21

Koboldt DC Larson DE Wilson RK . Using varScan 2 for germline variant calling and somatic mutation detection. Curr Protoc Bioinf. (2013) 21:15–17. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1504s44

22

Cerami E Gao J Dogrusoz U Gross BE Sumer SO Aksoy BA et al . The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. (2012) 2:401–4. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0095

23

Gao J Aksoy BA Dogrusoz U Dresdner G Gross B Sumer SO et al . Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. Sci Signal. (2013) 6:pl1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088

24

de Bruijn I Kundra R Mastrogiacomo B Tran TN Sikina L Mazor T et al . Analysis and visualization of longitudinal genomic and clinical data from the AACR project GENIE biopharma collaborative in cBioPortal. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:3861–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0816

25

Karczewski KJ Francioli LC Tiao G Cummings BB Alfoldi J Wang Q et al . The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. (2020) 581:434–43. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7

26

Chen S Francioli LC Goodrich JK Collins RL Kanai M Wang Q et al . A genomic mutational constraint map using variation in 76,156 human genomes. Nature. (2024) 625:92–100. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06045-0

27

He W Dong S Shen J Wu J Zhao P Li D et al . Whole-genome sequencing identified novel mutations in a Chinese family with lynch syndrome. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1036356. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1036356

28

Gutman T Goren G Efroni O Tuller T . Estimating the predictive power of silent mutations on cancer classification and prognosis. NPJ Genom Med. (2021) 6:67. doi: 10.1038/s41525-021-00229-1

29

Rentzsch P Witten D Cooper GM Shendure J Kircher M . CADD: predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. (2018) 47:D886–D94. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1016

30

Malone E Siu LL . Precision medicine in head and neck cancer: myth or reality? Clin Med Insights Oncol. (2018) 12:1179554918779581. doi: 10.1177/1179554918779581

31

Tahara M Greil R Rischin D Harrington KJ Burtness B de Castro G et al . Pembrolizumab with or without chemotherapy in recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: 5-year follow-up from the randomized phase III KEYNOTE-048 study. Eur J Cancer. (2025) 221:115395. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2025.115395

32

Grunwald V Chirovsky D Cheung WY Bertolini F Ahn MJ Yang MH et al . Global treatment patterns and outcomes among patients with recurrent and/or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Results of the GLANCE H&N study. Oral Oncol. (2020) 102:104526. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2019.104526

33

Duprez F Berwouts D De Neve W Bonte K Boterberg T Deron P et al . Distant metastases in head and neck cancer. Head Neck. (2017) 39:1733–43. doi: 10.1002/hed.24687

34

Sunavala-Dossabhoy G Palaniyandi S Clark C Nathan CO Abreo FW Caldito G . Analysis of eIF4E and 4EBP1 mRNAs in head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. (2011) 121:2136–41. doi: 10.1002/lary.22144

35

Huang CI Wang CC Tai TS Hwang TZ Yang CC Hsu CM et al . eIF4E and 4EBP1 are prognostic markers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma recurrence after definitive surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. PloS One. (2019) 14:e0225537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0225537

36

Fu T Amoah K Chan TW Bahn JH Lee JH Terrazas S et al . Massively parallel screen uncovers many rare 3’ UTR variants regulating mRNA abundance of cancer driver genes. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:3335. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46795-7

37

Oyama T Harigaya K Sasaki N Okamura Y Kokubo H Saga Y et al . Mastermind-like 1 (MamL1) and mastermind-like 3 (MamL3) are essential for Notch signaling in vivo. Dev (Cambridge England). (2011) 138:5235–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.062802

38

Carter H Ideker T . Common genetic variation in the germline influences where and how tumors develop. Mol Cell Oncol. (2017) 4:e1302905. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2017.1302905

39

Qing T Mohsen H Marczyk M Ye Y O’Meara T Zhao H et al . Germline variant burden in cancer genes correlates with age at diagnosis and somatic mutation burden. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:2438. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16293-7

40

Rieke DT Ochsenreither S Klinghammer K Seiwert TY Klauschen F Tinhofer I et al . Methylation of RAD51B, XRCC3 and other homologous recombination genes is associated with expression of immune checkpoints and an inflammatory signature in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck, lung and cervix. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:75379–93. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12211

41

Freed-Pastor WA Prives C . Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev. (2012) 26:1268–86. doi: 10.1101/gad.190678.112

42

Klemke L Fehlau CF Winkler N Toboll F Singh SK Moll UM et al . The gain-of-function p53 R248W mutant promotes migration by STAT3 deregulation in human pancreatic cancer cells. Front Oncol. (2021) 11:642603. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.642603

43

Shi T Polderman PE Pages-Gallego M van Es RM Vos HR Burgering BMT et al . p53 forms redox-dependent protein-protein interactions through cysteine 277. Antioxidants (Basel). (2021) 10:1578. doi: 10.3390/antiox10101578

44

Consortium TU . UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase in 2025. Nucleic Acids Res. (2024) 53:D609–D17. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkae1010

45

Liu F Ou YM Yu AR Xiong L Xin HW . Long-term influence of CYP3A5, CYP3A4, ABCB1, and NR1I2 polymorphisms on tacrolimus concentration in chinese renal transplant recipients. Genet testing Mol biomarkers. (2017) 21:663–73. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2017.0088

46

Klinakis A Rampias T . TP53 mutational landscape of metastatic head and neck cancer reveals patterns of mutation selection. EBioMedicine. (2020) 58:102905. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102905

47

Garsed DW Pandey A Fereday S Kennedy CJ Takahashi K Alsop K et al . The genomic and immune landscape of long-term survivors of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat Genet. (2022) 54:1853–64. doi: 10.1038/s41588-022-01230-9

Summary

Keywords

laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma, recurrent-metastatic, case-report, long-term survival, genomic profiling

Citation

Bišof V, Soče M, Škrtić A, Seiwert S and Peričić Salihović M (2025) Genomic landscape of a long-term surviving patient with metastatic cancer of the larynx: a case report. Front. Oncol. 15:1691802. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1691802

Received

24 August 2025

Revised

02 November 2025

Accepted

17 November 2025

Published

02 December 2025

Volume

15 - 2025

Edited by

Bodour Salhia, University of Southern California, United States

Reviewed by

Sankar Jagadeeshan, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel

Cristina Conde-Lopez, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Bišof, Soče, Škrtić, Seiwert and Peričić Salihović.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vesna Bišof, vbisof@gmail.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.