- 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

- 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Chongqing General Hospital, Chongqing University, Chongqing, China

- 3Department of Ultrasound, Chongqing Nan’an District People’s Hospital, Chongqing, China

- 4Department of Laboratory Medicine, Chonggang General Hospital, Chongqing, China

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) remains a prevalent epithelial malignancy. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors have reshaped first-line therapy for recurrent/metastatic disease; yet durable benefit is confined to a subset, reflecting myeloid-centric mechanisms—SPP1+ TAM barriers, cDC1/IL-12 insufficiency, and CXCL8–CXCR1/2–driven neutrophil trafficking—distinct from, and complementary to, classical lymphoid exhaustion. In this review we summarize advances from single-cell RNA and ATAC profiling and spatial transcriptomics that resolve macrophage, dendritic-cell and neutrophil programs, and appraise translational opportunities spanning myeloid reprogramming, innate–adaptive combinations and spatial biomarkers. We also discuss enduring challenges—including HPV-status heterogeneity, limited assay standardization and a scarcity of predictive metrics—that temper implementation. By integrating myeloid-informed readouts (e.g., SPP1–TAM burden, cDC1 competency, serum IL-8) with PD-1–based regimens, EGFR-directed antibodies and myeloid checkpoints (CD47–SIRPα, PI3Kγ, CXCR1/2), emerging strategies aim to restore antigen presentation, improve lymphocyte trafficking and remodel tumor–stroma interfaces. Our synthesis provides an appraisal of the evolving landscape of myeloid-informed precision immuno-oncology in HNSCC and outlines pragmatic standards and avenues for clinical translation. We hope these insights will assist researchers and clinicians as they endeavor to implement more effective, individualized regimens.

1 Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) remains a common epithelial malignancy with heterogeneous etiologies and outcomes, including tobacco- and alcohol-associated disease and virally driven subsets (1–3), and immune checkpoint inhibitors have become part of first-line therapy for recurrent or metastatic disease on the basis of randomized evidence (4–7); nonetheless, durable benefit is restricted to a subset of patients, underscoring the need to resolve mechanisms of immune failure at tissue and single-cell resolution.

Across HNSCCs, myeloid lineages constitute a dominant—and markedly heterogeneous—fraction of the tumor microenvironment, varying by HPV status, anatomic site, and spatial niche, and are repeatedly linked to immunosuppression and adverse prognosis (8–10). Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) quantified by canonical markers correlate with inferior survival in aggregated cohorts, while mechanistic studies implicate macrophage programs in antigen presentation deficits and T-cell exclusion (11–13). Monocytic and granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are enriched in HNSCC and dampen antitumor effector functions through arginase activity, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen intermediates, and checkpoint ligand expression; contemporary reviews in HNSCC synthesize these developmental routes and therapeutic entry points (14–16). Neutrophils also show context-dependent roles in HNSCC with functional states that range from cytotoxic to immunoregulatory, aligning with clinical observations that neutrophil phenotypes vary with stage and microenvironmental cues (17, 18). These data converge on a model in which myeloid circuits—rather than lymphoid scarcity alone—are primary architects of immune resistance.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) established the cellular framework for this model by resolving malignant programs, stromal elements, and discrete immune states in primary and metastatic HNSCC (19–21). Foundational datasets defined partial epithelial–mesenchymal transition trajectories in malignant epithelium, exhausted and progenitor-like T-cell states, and macrophage heterogeneity with ligand–receptor interactions that forecast immune dysfunction (22, 23). Subsequent scRNA-seq maps across HPV-positive and HPV-negative tumors show site- and virus-dependent shifts, with HPV+ disease enriched for B/Tfh/TLS and antigen-presenting/CXCL9+ macrophages, and HPV− lesions enriched for SPP1+/TREM2+ lipid-handling TAMs and CXCL8-high neutrophil/MDSC programs, informing biomarker recalibration (e.g., SPP1–TAM thresholds, PD-L1 CPS context) and therapy selection (EGFR-antibody or myeloid-modulating combinations) (24, 25). These atlases provide candidate axes for immunologic failure (e.g., SPP1+ macrophages, interferon-conditioned dendritic cells, CXCL chemokine circuits) that are testable in prospective cohorts.

Complementing transcriptomic views, single-cell chromatin accessibility profiling now captures cis-regulatory logic in HNSCC. In HNSCC myeloid cells, scATAC peak–gene links reveal accessible enhancers at SPP1/APOE–TREM2 and CIITA that track, respectively, with SPP1+ lipid-handling TAMs and antigen-presenting macrophages, while motif deviations for IRF/STAT, AP-1, C/EBPβ, PPAR/MAF and PU.1 align with polarization and CXCL8–CXCR1/2–neutrophil programs, with orthogonal evidence still required for causality (26–28). Broader single-nucleus ATAC-seq efforts across carcinomas validate the feasibility of mapping lineage-restricted enhancer usage and transcription-factor dependencies at single-cell resolution, enabling cross-cancer comparison of myeloid regulatory programs relevant to HNSCC (29–31).

Spatially resolved transcriptomic profiling has further demonstrated that the organization of myeloid, lymphoid, and malignant niches carries prognostic information and aligns with therapeutic responsiveness (32, 33). In HNSCC cohorts analyzed by single-cell-aware spatial methods, reproducible architectures—such as macrophage-dense tumor cores juxtaposed with immune-excluded epithelial fronts or myeloid-enriched stromal corridors—associate with survival and with inferred sensitivity to targeted and immune therapies (34, 35), indicating that spatial context is not incidental but determinative. Spatial analyses also connect early dissemination and nodal progression to immune-evasion ecosystems that feature coordinated myeloid–tumor signaling, reinforcing the translational value of mapping myeloid topology alongside malignant trajectories.

This review takes a myeloid-centric perspective on immunosuppression in HNSCC and synthesizes evidence from single-cell RNA and ATAC assays and spatial transcriptomic studies. The objectives are to delineate conserved and context-specific myeloid programs that constrain antitumor immunity; to map crosstalk between myeloid states and lymphoid dysfunction within spatial ecosystems; and to connect these features to emerging biomarkers and therapeutic strategies. Emphasis is placed on studies from Springer Nature and Elsevier journals to ensure methodological transparency and reproducibility. Examine tumor-associated myeloid programs in HNSCC at single-cell resolution, analyze spatially organized immune ecosystems and myeloid–lymphoid interactions, assess clinical translation through biomarker development and myeloid-directed interventions, and propose practical standards for integrative myeloid profiling in HNSCC.

2 Single-cell programs of tumor-associated myeloid cells in head and neck cancer

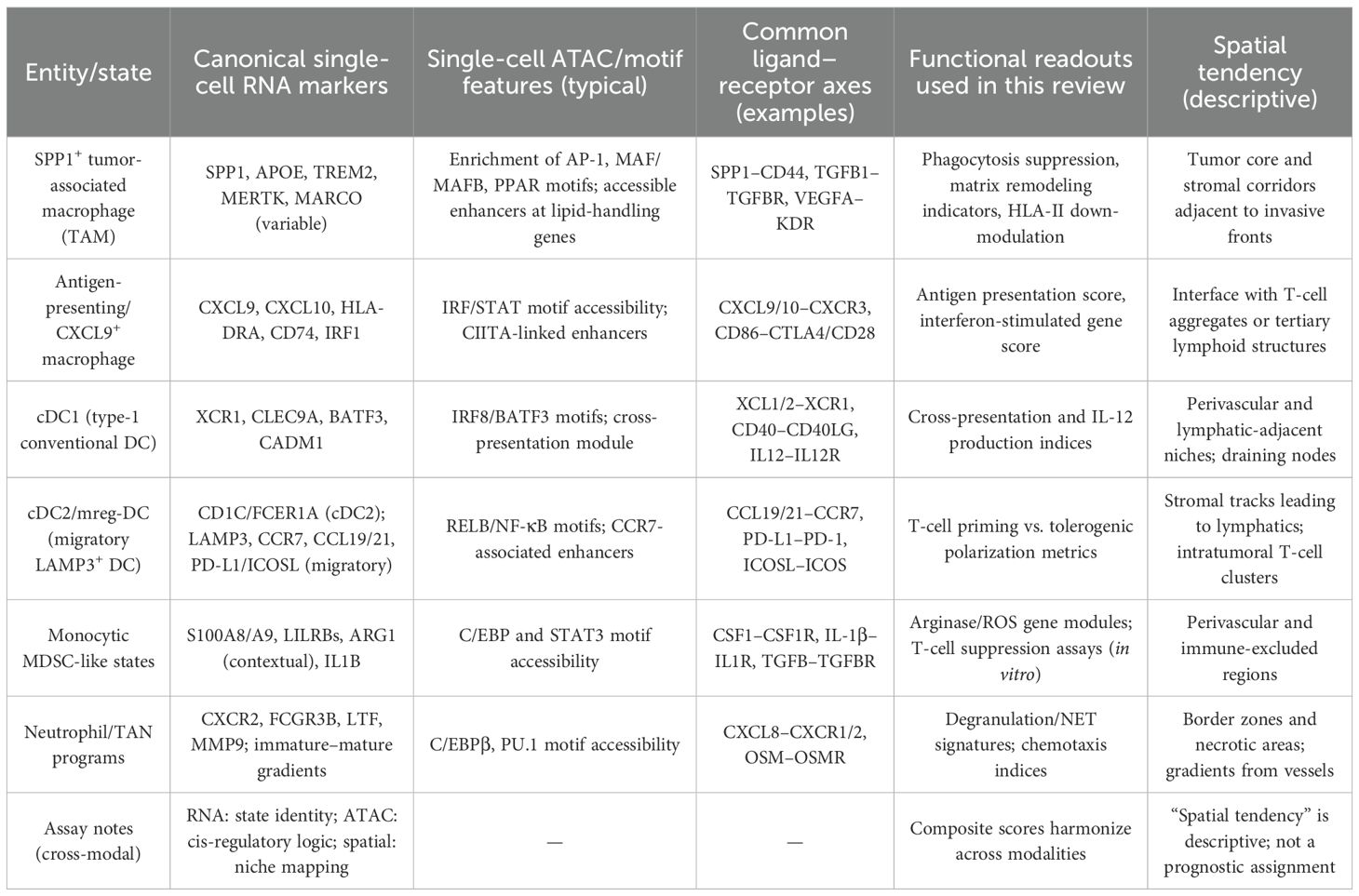

Single-cell profiling delineates recurrent myeloid states in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) that are mechanistically linked to antigen presentation deficits, T-cell dysfunction, and malignant progression (36, 37). As shown in Table 1, early atlases established the cellular framework of the HNSCC microenvironment and revealed macrophage and dendritic-cell diversity across primary tumors and nodal metastases, with differences between HPV-positive and HPV-negative disease in compartment proportions and transcriptional programs (38, 39).

Macrophages constitute the dominant myeloid compartment and separate along axes of SPP1+ lipid-handling, matrix-remodeling TAMs versus interferon-conditioned, antigen-presenting CXCL9/10+ states (40, 41). In HNSCC, SPP1+ TAMs show functional coupling to tumor and stromal programs and are linked to invasive phenotypes, while antigen-presenting macrophages co-localize with T-cell aggregates and tertiary lymphoid features (42, 43). Single-cell studies and integrative analyses in HNSCC demonstrate that SPP1+ TAMs engage CD44 and NF-κB–linked pathways, under PI3Kγ–AKT–CREB/STAT3 control, and form reciprocal interactions with SFRP2+ cancer-associated fibroblasts, supporting a pro-invasive ecosystem (44, 45).

Dendritic-cell programs bifurcate along an immature→mature continuum: pre-cDC1 (IRF8high/BATF3+) mature into XCR1+CLEC9A+ cDC1 that cross-present and deliver IL-12, whereas cDC2 transition to LAMP3+CCR7+ migratory ‘mreg-DC’ that upregulate PD-L1/ICOSL and acquire immunoregulatory secretomes (46, 47). In HNSCC models that preserve tumor-draining lymphatics, cDC1 accumulation and type-I-interferon signaling are necessary for response to checkpoint blockade; disruption of lymphatic egress abrogates these features and diminishes efficacy (48, 49). Single-cell phenotyping also links a PD-L1high ICOSLlow “secretory” DC state to attenuated T-helper polarization, whereas ICOSL-dominant DC associate with improved immune activation, including in HNSCC cohorts.

Myeloid-derived suppressor phenotypes emerge along monocytic and granulocytic lineages, with monocytes (LYZ+, S100A8/A9+) differentiating toward SPP1+ TAMs or antigen-presenting-like macrophages, and neutrophils progressing from immature CXCR2+/LTF+ states to antigen-presenting-like, MHC-II+/CD74+ subsets. Pan-cancer single-cell integrations identify conserved TREM2+/FOLR2+ myeloid states and clarify that suppressive programs can be misclassified when analyzed in bulk; within HNSCC datasets these states co-occur with hypoxia and cytokine-rich niches (50, 51). In parallel, neutrophil programs span immature, inflammatory, and antigen-presenting-like trajectories; single-cell compendia across tumors, including head and neck cancers, resolve transcriptional continua that explain prior context-dependent associations of tumor-associated neutrophils with either immune control or suppression.

Transcriptional states are underpinned by cis-regulatory logic that is now measurable in HNSCC using single-cell and bulk ATAC-seq. Under EGFR blockade, enhancer remodeling occurs rapidly in epithelial and myeloid compartments, with IRF/STAT and AP-1 network shifts that presage adaptive resistance and track with interferon and antigen-presentation programs (52, 53). These observations support integrating single-cell ATAC with RNA to resolve lineage dependencies and to nominate tractable regulators of myeloid polarization in HNSCC.

Single-cell RNA and ATAC assays in HNSCC converge on a structured view of tumor-associated myeloid biology: SPP1+ macrophages and suppressive MDC/MDSC modules organize immune-excluded niches; cDC1 insufficiency and migratory LAMP3+ DC reprogramming constrain priming; and neutrophil states reinforce chemokine and matrix circuits. These axes provide testable links to spatial organization.

3 Spatial immune ecosystems and myeloid–lymphoid crosstalk

In HNSCC, spatial profiling shows TLS-rich lymphoid hubs and CD8–cDC1 corridors associate with survival and checkpoint response, whereas continuous SPP1+ TAM–tumor borders and POSTN+ CAF corridors mark immune exclusion and worse outcomes, indicating that topology adds prognostic and pharmacodynamic information beyond bulk composition. Single-cell–aware multiplex tissue imaging in human papillomavirus–negative tumors links greater compartmentalization of tumor–immune territories and mesenchymal neighborhood organization with improved progression-free survival, indicating that spatial topology is an informative dimension of immune competence in this disease (54, 55). Complementary spatial proteogenomic analyses in clinical specimens further show that heterogeneous tumor hubs are flanked by immune niches with distinct ligand–receptor activity, supporting the use of multi-omic spatial readouts to nominate therapeutic targets within location-defined ecosystems (56, 57).

Humoral–cellular immune hubs are prominent features of favorable ecosystems. In HPV-positive tumors, B-cell–rich aggregates with germinal-center architecture and T-follicular-helper activity form tertiary lymphoid structures that correlate with superior outcomes, where local antigen presentation, Tfh-guided affinity maturation, and HEV-mediated trafficking sustain CD8 and memory responses (58, 59). Distance-based spatial metrics generalize these observations: in pre-operative ipilimumab+nivolumab cohorts, nearest-neighbor relationships—rather than density—discriminate response; a pragmatic schema uses median CD8→cDC1 and CD8→HEV distances and macrophage–tumor interface length as spatial biomarkers of checkpoint benefit, derivable from multiplex IHC/CODEX or MIBI (60–62).

Myeloid positioning at tumor–stroma interfaces provides a mechanistic substrate for immune exclusion and checkpoint signaling. Spatial interaction mapping that resolves in situ PD-1/PD-L1 ligation identifies macrophage-dense layers at tumor margins in non-responders, consistent with a barrier that restricts effective lymphocyte access; in contrast, responders show B- and T-cell aggregates at tumor edges with fewer continuous macrophage–tumor interfaces (63–65). These findings align with single-cell and spatial views in oral cavity tumors in which SPP1+ tumor-associated macrophages co-localize with POSTN+ fibroblasts and malignant programs to form a desmoplastic, immunoregulatory network capable of shaping T-cell trafficking and function (66, 67), offering a tractable axis for ecosystem remodeling. For clinical sampling, prioritize cores that include the tumor–stroma interface and perivascular regions (and nodal metastases when present), because these sites maximize measurable myeloid–lymphoid adjacency and reduce false-negative proximity scores.

Antigen-presenting cell geography further constrains priming and effector function. Across carcinomas, tumor-retained CCR7+ migratory dendritic cells downregulate antigen-presentation programs with dwell time, implying that retention within the tumor parenchyma diminishes cross-priming potential (68, 69). Lymphatic-localized crosstalk between mature, immunoregulatory LAMP3+ dendritic cells and regulatory T cells has been shown to limit CD8+ T-cell immunity, highlighting a spatially delimited checkpoint that likely intersects with the architectures observed in head and neck cancer (70–72). Embedding these dendritic-cell circuits within HNSCC spatial atlases will clarify whether restoring cDC1 access to T cells within peritumoral or intratumoral niches can convert excluded to inflamed phenotypes.

These data indicate that spatial ecosystems in head and neck cancer are defined by adjacency rules—macrophage–tumor interfaces at borders, TLS-like lymphoid hubs, and dendritic-cell corridors linking tissue and lymphatics—that govern myeloid–lymphoid communication, checkpoint engagement, and therapeutic responsiveness. Mapping and perturbing these arrangements provide a pathway to convert suppressive architectures into productive antigen-presentation and T-cell–effector niches, and justify spatially informed biomarkers for clinical decision-making in this disease.

4 Clinical translation: biomarkers and myeloid-directed therapeutics

Clinically deployed biomarkers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma currently prioritize PD-L1 combined positive score to select regimens containing pembrolizumab, yet response heterogeneity underlines the need for composite models that quantify myeloid-driven suppression in parallel with adaptive immune competence (73, 74). Randomized evidence demonstrated overall-survival benefit with pembrolizumab-based therapy in recurrent/metastatic disease and established PD-L1 thresholds for treatment assignment, but predictive performance remains incomplete, supporting development of adjunct biomarkers that index myeloid state and spatial organization (75–77).

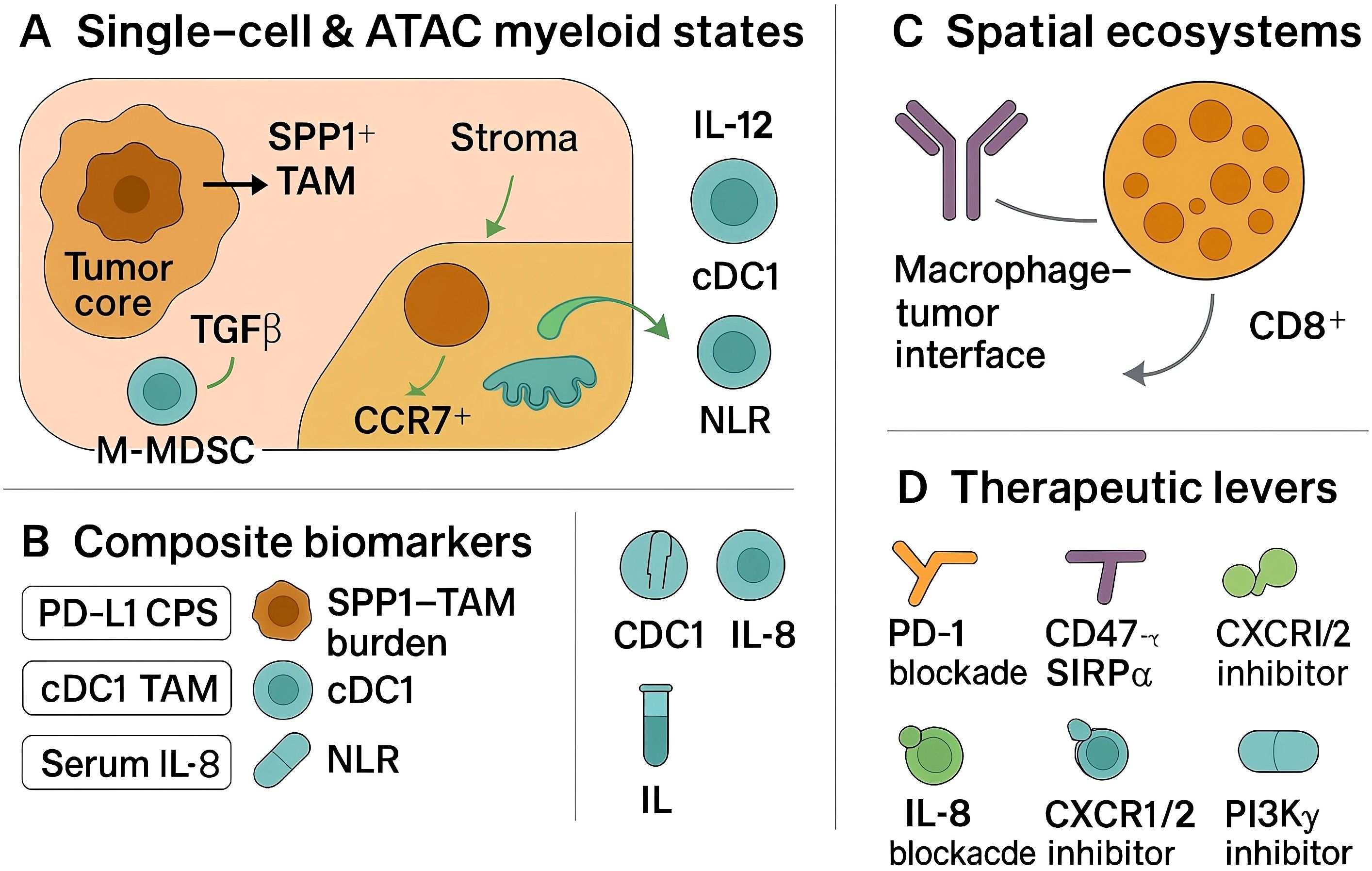

Myeloid-informed tissue biomarkers are increasingly tractable. Single-cell–grounded signatures and immunohistochemical surrogates for SPP1+ tumor-associated macrophages correlate with immunosuppressive programs, matrix remodeling, and inferior outcomes in head and neck and oral cavity cohorts, nominating an “SPP1–TAM burden” as a candidate readout to complement PD-L1 and tumor mutation burden in clinical decision-making (78, 79). Quantification can be implemented in routine tissue: compute XCR1+CLEC9A+ cDC1 density (cells/mm2 by multiplex IHC) and an IL-12 module score from RNA panels (IL12A/IL12B with CXCL9/CXCL10 co-expression), alongside an SPP1–TAM burden (SPP1/CD68/MERTK IHC or RNA) (80, 81). As shown in Figure 1, circulating inflammatory signals that reflect myeloid trafficking also carry prognostic and pharmacodynamic information; baseline serum interleukin-8 predicts inferior benefit across anti–PD-1/PD-L1 and anti–CTLA-4 regimens (and PD-1–cetuximab combinations), consistent with its role in neutrophil/MDSC recruitment, supporting inclusion in pre-treatment risk stratification and on-therapy monitoring (82, 83). Readily available systemic indices, such as the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, have shown association with pembrolizumab efficacy in real-world head and neck cohorts and may provide cost-efficient triage when high-parameter profiling is not feasible (84, 85). Spatial biomarkers derived from tissue imaging and spatial transcriptomics further refine risk: tertiary lymphoid structures and B-cell–rich aggregates are reproducibly associated with favorable outcomes in head and neck cancer and can be co-analyzed with myeloid topology to contextualize checkpoint signaling and antigen presentation (86, 87). Preservation or restoration of cDC1-linked migratory circuits between tumor and draining lymphatics appears necessary for effective checkpoint responses, providing a mechanistic axis for spatially informed stratification.

Figure 1. Myeloid-driven immunosuppression in HNSCC: single-cell states, spatial interfaces, and therapeutic levers.

Therapeutic strategies that directly target myeloid checkpoints or reprogram suppressive myeloid circuits are entering head and neck–relevant clinical testing. CD47–SIRPα blockade enhances macrophage-mediated phagocytosis; the high-affinity CD47 inhibitor evorpacept has demonstrated manageable safety and signs of activity across solid tumors including a head and neck expansion, and its biology supports combination with PD-1 inhibitors and with Fc-active EGFR antibodies used in this disease (88, 89). Dual targeting of the adaptive and innate compartments is further supported by pembrolizumab plus cetuximab: cetuximab engages FcγRIIIa on NK cells (ADCC) and FcγR on macrophages (ADCP), while PD-1 blockade reinvigorates effectors; however, macrophage ‘walls’ at tumor margins and FcγR polymorphisms may modulate benefit, motivating assays of myeloid exclusion and Fc competence (90, 91). Neutralization of IL-8 is a rational adjunct to checkpoint blockade given its association with primary resistance and myeloid chemotaxis; translational and preclinical data indicate that IL-8 axis inhibition can diminish suppressive myeloid infiltration and restore antitumor immunity (92, 93). TAM reprogramming via PI3Kγ inhibition has strong mechanistic support—PI3Kγ functions as a switch enforcing immunosuppressive transcriptional programs in myeloid cells—and represents a complementary route to enhance checkpoint efficacy, though definitive head and neck–specific clinical benefit remains to be established. Additional upstream interventions that curb myeloid recruitment, such as blockade of CXCR2-dependent neutrophil trafficking, are justified by preclinical evidence and early translational studies and warrant head and neck–focused evaluation with prespecified myeloid pharmacodynamic endpoints (94, 95). Emerging evidence in human papillomavirus–negative head and neck models also supports combined disruption of inflammatory cytokine and monocyte-chemokine pathways—for example, IL-6 plus CCR2 blockade—to limit suppressive myeloid niches and potentiate cytotoxic effector function (96, 97).

Implementation should prioritize analytically validated assays, predefined thresholds, and prospective integration into trial designs that randomize myeloid-directed combinations against current standard immunotherapy backbones. A pragmatic biomarker panel would pair PD-L1 CPS with a myeloid score (e.g., SPP1–TAM burden), serum IL-8, and a spatial readout capturing myeloid–lymphoid adjacency or tertiary lymphoid structure status, with adaptive sampling to evaluate on-treatment myeloid plasticity. Such schema allow attribution of benefit to myeloid modulation, enable early stopping for futility when myeloid targets are not engaged, and create a pathway to deploy myeloid-directed therapeutics in a biologically selected subset of patients with head and neck cancer.

5 Outlook and standards for integrative myeloid profiling in head and neck cancer

Integrative myeloid profiling in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma should advance from descriptive atlases to standardized, decision-oriented pipelines that co-register single-cell RNA, single-cell ATAC, and spatial readouts with harmonized metadata and predefined endpoints. Foundational single-cell and chromatin studies justify a state dictionary anchored on SPP1+ tumor-associated macrophages, antigen-presenting/CXCL9+ macrophages, cDC1, LAMP3+ migratory dendritic cells, monocytic/granulocytic MDSC, and context-dependent neutrophil programs, with motif-level regulators (IRF/STAT/AP-1) reported alongside ligand–receptor inferences (26–31, 40–47, 50, 51).

Spatial analyses indicate that adjacency metrics—macrophage–tumor interface length, tertiary lymphoid structure burden, and nearest-neighbor distances between myeloid and lymphoid cells—capture clinically relevant architecture beyond cell fractions and should be quantified with assay-specific quality controls (32–35, 58–62, 86, 87). For clinical translation, composite models should pair PD-L1 combined positive score with a myeloid score (e.g., SPP1-TAM burden), serum IL-8 and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte indices, and a spatial topology score, all benchmarked to response and survival under contemporary immunotherapy backbones (73–85).

Prospective trials should embed these assays with prespecified analytical thresholds, transparent batch correction, cross-platform validations, and on-treatment pharmacodynamic criteria that attribute benefit to myeloid modulation (depletion/reprogramming of suppressive states, restoration of cDC1 circuits, remodeling of macrophage–tumor borders) (46–49, 78–81).

We anticipate that HPV-negative tumors with high SPP1-TAM burden and continuous macrophage–tumor interfaces will be candidates for TAM-directed or IL-8–axis combinations layered onto PD-1 regimens, whereas HPV-positive, TLS-rich ecosystems may preferentially benefit from strategies that preserve cDC1 trafficking and enhance dendritic-cell priming (24, 25, 58, 59, 86, 87). Establishing these reporting and performance standards will enable reproducible risk stratification, facilitate cross-study synthesis, and accelerate deployment of myeloid-informed precision therapy in head and neck cancer.

Author contributions

RL: Visualization, Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JY: Visualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. ZC: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. BL: Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Ruffin AT, Cillo AR, Tabib T, Liu A, Onkar S, Kunning SR, et al. B cell signatures and tertiary lymphoid structures contribute to outcome in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. (2021) 12:3349. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23355-x

2. Sacco AG, Chen R, Worden FP, Wong DJ, Adkins D, Swiecicki P, et al. Pembrolizumab plus cetuximab in patients with recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: an open-label, multi-arm, non-randomised, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:883–92. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00136-4

3. Causer A, Tan X, Lu X, Moseley P, Teoh SM, Molotkov N, et al. Deep spatial-omics analysis of Head & Neck carcinomas provides alternative therapeutic targets and rationale for treatment failure. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2023) 7:89. doi: 10.1038/s41698-023-00444-2

4. Arora R, Cao C, Kumar M, Sinha S, Chanda A, McNeil R, et al. Spatial transcriptomics reveals distinct and conserved tumor core and edge architectures that predict survival and targeted therapy response. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:5029. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40271-4

5. Liu C, Wu K, Li C, Zhang Z, Zhai P, Guo H, et al. SPP1+ macrophages promote head and neck squamous cell carcinoma progression by secreting TNF-α and IL-1β. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. (2024) 43:332. doi: 10.1186/s13046-024-03255-w

6. Coulton A, Murai J, Qian D, Thakkar K, Lewis CE, and Litchfield K. Using a pan-cancer atlas to investigate tumour associated macrophages as regulators of immunotherapy response. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:5665. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-49885-8

7. Liu H, Zhao Q, Tan L, Wu X, Huang R, Zuo Y, et al. Neutralizing IL-8 potentiates immune checkpoint blockade efficacy for glioma. Cancer Cell. (2023) 41:693–710. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.03.004

8. Schalper KA, Carleton M, Zhou M, Chen T, Feng Y, Huang SP, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-8 is associated with enhanced intratumor neutrophils and reduced clinical benefit of immune-checkpoint inhibitors. Nat Med. (2020) 26:688–92. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0856-x

9. Farmer A, Thibivilliers S, Ryu KH, Schiefelbein J, and Libault M. Single-nucleus RNA and ATAC sequencing reveals the impact of chromatin accessibility on gene expression in Arabidopsis roots at the single-cell level. Mol Plant. (2021) 14:372–83. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2021.01.001

10. Fang K, Ohihoin AG, Liu T, Choppavarapu L, Nosirov B, Wang Q, et al. Integrated single-cell analysis reveals distinct epigenetic-regulated cancer cell states and a heterogeneity-guided core signature in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer. Genome Med. (2024) 16:134. doi: 10.1186/s13073-024-01407-3

11. Tayyebi Z, Pine AR, and Leslie CS. Scalable and unbiased sequence-informed embedding of single-cell ATAC-seq data with CellSpace. Nat Methods. (2024) 21:1014–22. doi: 10.1038/s41592-024-02274-x

12. Su K, Wang F, Li X, Chi H, Zhang J, He K, et al. Effect of external beam radiation therapy versus transcatheter arterial chemoembolization for non-diffuse hepatocellular carcinoma (≥ 5 cm): a multicenter experience over a ten-year period. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1265959. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1265959

13. Li W, Pan L, Hong W, Ginhoux F, Zhang X, Xiao C, et al. A single-cell pan-cancer analysis to show the variability of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells in immune checkpoint blockade. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:6142. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-50478-8

14. Jhaveri N, Ben Cheikh B, Nikulina N, Ma N, Klymyshyn D, DeRosa J, et al. Mapping the spatial proteome of head and neck tumors: key immune mediators and metabolic determinants in the tumor microenvironment. Gen Biotechnol. (2023) 2:418–34. doi: 10.1089/genbio.2023.0029

15. Kasikova L, Rakova J, Hensler M, Lanickova T, Tomankova J, Pasulka J, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures and B cells determine clinically relevant T cell phenotypes in ovarian cancer. Nat Commun. (2024) 15:2528. doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-46873-w

16. Su X, Liang C, Chen R, and Duan S. Deciphering tumor microenvironment: CXCL9 and SPP1 as crucial determinants of tumor-associated macrophage polarity and prognostic indicators. Mol Cancer. (2024) 23:13. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01931-7

17. O'Connell BC, Hubbard C, Zizlsperger N, Fitzgerald D, Kutok JL, Varner J, et al. Eganelisib combined with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and chemotherapy in frontline metastatic triple-negative breast cancer triggers macrophage reprogramming, immune activation and extracellular matrix reorganization in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunotherapy Cancer. (2024) 12:e009160. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-009160

18. Sitaru S, Budke A, Bertini R, and Sperandio M. Therapeutic inhibition of CXCR1/2: where do we stand? Internal Emergency Med. (2023) 18:1647–64.

19. Lakhani NJ, Chow LQ, Gainor JF, LoRusso P, Lee KW, Chung HC, et al. Evorpacept alone and in combination with pembrolizumab or trastuzumab in patients with advanced solid tumours (ASPEN-01): a first-in-human, open-label, multicentre, phase 1 dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. Lancet Oncol. (2021) 22:1740–51. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00584-2

20. Li H, Guo L, Su K, Li C, Jiang Y, Wang P, et al. Construction and validation of TACE therapeutic efficacy by ALR score and nomogram: a large, multicenter study. J Hepatocellular Carcinoma. (2023) 10:1009–17. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S414926

21. Colonna M. The biology of TREM receptors. Nat Rev Immunol. (2023) 23:580–94. doi: 10.1038/s41577-023-00837-1

22. Berrell N, Monkman J, Donovan M, Blick T, O'Byrne K, Ladwa R, et al. Spatial resolution of the head and neck cancer tumor microenvironment to identify tumor and stromal features associated with therapy response. Immunol Cell Biol. (2024) 102:830–46. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12811

23. Sundaram L, Kumar A, Zatzman M, Salcedo A, Ravindra N, Shams S, et al. Single-cell chromatin accessibility reveals Malignant regulatory programs in primary human cancers. Science. (2024) 385:eadk9217. doi: 10.1126/science.adk9217

24. Mei S, Zhang H, Hirz T, Jeffries NE, Xu Y, Baryawno N, et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveal a tumor-associated macrophage subpopulation that mediates prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Mol Cancer Res. (2025) 23:653–65. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-24-0791

25. Sadeghirad H, Monkman J, Tan CW, Liu N, Yunis J, Donovan ML, et al. Spatial dynamics of tertiary lymphoid aggregates in head and neck cancer: insights into immunotherapy response. J Trans Med. (2024) 22:677. doi: 10.1186/s12967-024-05409-y

26. Bill R, Wirapati P, Messemaker M, Roh W, Zitti B, Duval F, et al. CXCL9: SPP1 macrophage polarity identifies a network of cellular programs that control human cancers. Science. (2023) 381:515–24. doi: 10.1126/science.ade2292

27. Zhang P, Zhang H, Tang J, Ren Q, Zhang J, Chi H, et al. The integrated single-cell analysis developed an immunogenic cell death signature to predict lung adenocarcinoma prognosis and immunotherapy. Aging (Albany NY). (2023) 15:10305. doi: 10.18632/aging.205077

28. Lee H, Park S, Yun JH, Seo C, Ahn JM, Cha HY, et al. Deciphering head and neck cancer microenvironment: single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveals human papillomavirus-associated differences. J Med Virol. (2024) 96:e29386. doi: 10.1002/jmv.29386

29. Quek C, Pratapa A, Bai X, Al-Eryani G, da Silva IP, Mayer A, et al. Single-cell spatial multiomics reveals tumor microenvironment vulnerabilities in cancer resistance to immunotherapy. Cell Rep. (2024) 43:114392. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2024.114392

30. Yuan K, Zhao S, Ye B, Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhang P, et al. A novel T-cell exhaustion-related feature can accurately predict the prognosis of OC patients. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1192777. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1192777

31. Muijlwijk T, Nijenhuis DN, Ganzevles SH, Ekhlas F, Ballesteros-Merino C, Peferoen LA, et al. Immune cell topography of head and neck cancer. J Immunotherapy Cancer. (2024) 12:e009550. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-009550

32. Dayao MT, Trevino A, Kim H, Ruffalo M, D’Angio HB, Preska R, et al. Deriving spatial features from in situ proteomics imaging to enhance cancer survival analysis. Bioinformatics. (2023) 39:i140–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btad245

33. Wang M, Zhai R, Wang M, Zhu W, Zhang J, Yu M, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma improve prognosis by recruiting CD8+ T cells. Mol Oncol. (2023) 17:1514–30. doi: 10.1002/1878-0261.13403

34. Xu L, Chen Y, Liu L, Hu X, He C, Zhou Y, et al. Tumor-associated macrophage subtypes on cancer immunity along with prognostic analysis and SPP1-mediated interactions between tumor cells and macrophages. PloS Genet. (2024) 20:e1011235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1011235

35. Wu J, Shen Y, Zeng G, Liang Y, and Liao G. SPP1+ TAM subpopulations in tumor microenvironment promote intravasation and metastasis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther. (2024) 31:311–21. doi: 10.1038/s41417-023-00704-0

36. Choi JH, Lee BS, Jang JY, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Roh J, et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling of the stepwise progression of head and neck cancer. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1055. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36691-x

37. Terekhanova NV, Karpova A, Liang WW, Strzalkowski A, Chen S, Li Y, et al. Epigenetic regulation during cancer transitions across 11 tumour types. Nature. (2023) 623:432–41. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-06682-5

38. Raviram R, Raman A, Preissl S, Ning J, Wu S, Koga T, et al. Integrated analysis of single-cell chromatin state and transcriptome identified common vulnerability despite glioblastoma heterogeneity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. (2023) 120:e2210991120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2210991120

39. Bhat-Nakshatri P, Gao H, Khatpe AS, Adebayo AK, McGuire PC, Erdogan C, et al. Single-nucleus chromatin accessibility and transcriptomic map of breast tissues of women of diverse genetic ancestry. Nat Med. (2024) 30:3482–94. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03011-9

40. Zhang H, Mulqueen RM, Iannuzo N, Farrera DO, Polverino F, Galligan JJ, et al. txci-ATAC-seq: a massive-scale single-cell technique to profile chromatin accessibility. Genome Biol. (2024) 25:78. doi: 10.1186/s13059-023-03150-1

41. Cao Q, Zhang Q, Zhou KX, Li YX, Yu Y, He ZX, et al. Lung cancer screening study from a smoking population in Kunming. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. (2022) 26:7091–8.

42. Smith EA and Hodges HC. The spatial and genomic hierarchy of tumor ecosystems revealed by single-cell technologies. Trends Cancer. (2019) 5:411–25. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.05.009

43. Del Prete A, Salvi V, Soriani A, Laffranchi M, Sozio F, Bosisio D, et al. Dendritic cell subsets in cancer immunity and tumor antigen sensing. Cell Mol Immunol. (2023) 20:432–47. doi: 10.1038/s41423-023-00990-6

44. Reschke R and Olson DJ. Leveraging STING, batf3 dendritic cells, CXCR3 ligands, and other components related to innate immunity to induce A “Hot” Tumor microenvironment that is responsive to immunotherapy. Cancers. (2022) 14:2458. doi: 10.3390/cancers14102458

45. O'Connell BC, Hubbard C, Zizlsperger N, Fitzgerald D, Kutok JL, Varner J, et al. Eganelisib combined with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy and chemotherapy in frontline metastatic triple-negative breast cancer triggers macrophage reprogramming, immune activation and extracellular matrix reorganization in the tumor microenvironment. J Immunotherapy Cancer. (2024) 12:e009160. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-009160

46. Garcia-Manero G, Przespolewski A, Abaza Y, Byrne M, Fong AP, Jin F, et al. Evorpacept (ALX148), a CD47-blocking myeloid checkpoint inhibitor, in combination with azacitidine and venetoclax in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (ASPEN-05): results from phase 1a dose escalation part. (2022) 138:2601. doi: 10.1182/blood-2022-157606

47. Mir MA, Bashir M, and Ishfaq. Role of the CXCL8–CXCR1/2 axis in cancer and inflammatory diseases. In: Cytokine and Chemokine Networks in Cancer. Springer Nature Singapore, Singapore (2023). p. 291–329.

48. Greene S, Robbins Y, Mydlarz WK, Huynh AP, Schmitt NC, Friedman J, et al. Inhibition of MDSC trafficking with SX-682, a CXCR1/2 inhibitor, enhances NK-cell immunotherapy in head and neck cancer models. Clin Cancer Res. (2020) 26:1420–31. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2625

49. Jiang C, Sun H, Jiang Z, Tian W, Cang S, and Yu J. Targeting the CD47/SIRPα pathway in Malignancies: recent progress, difficulties and future perspectives. Front Oncol. (2024) 14:1378647. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1378647

50. Gong D, Arbesfeld-Qiu JM, Perrault E, Bae JW, and Hwang WL. Spatial oncology: Translating contextual biology to the clinic. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:1653–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.09.001

51. Li H, Guo L, Su K, Li C, Jiang Y, Wang P, et al. Construction and validation of TACE therapeutic efficacy by ALR score and nomogram: a large, multicenter study. J Hepatocellular Carcinoma. (2023) 10:1009–17. doi: 10.2147/JHC.S414926

52. Weed DT, Zilio S, McGee C, Marnissi B, Sargi Z, Franzmann E, et al. The tumor immune microenvironment architecture correlates with risk of recurrence in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. (2023) 83:3886–900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0379

53. Ding DY, Tang Z, Zhu B, Ren H, Shalek AK, Tibshirani R, et al. Quantitative characterization of tissue states using multiomics and ecological spatial analysis. Nat Genet. (2025) 57:910–21. doi: 10.1038/s41588-025-02119-z

54. Hu Y, Rong J, Xu Y, Xie R, Peng J, Gao L, et al. Unsupervised and supervised discovery of tissue cellular neighborhoods from cell phenotypes. Nat Methods. (2024) 21:267–78. doi: 10.1038/s41592-023-02124-2

55. Keren L, Bosse M, Thompson S, Risom T, Vijayaragavan K, McCaffrey E, et al. MIBI-TOF: A multiplexed imaging platform relates cellular phenotypes and tissue structure. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaax5851. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax5851

56. Patwa A, Yamashita R, Long J, Risom T, Angelo M, Keren L, et al. Multiplexed imaging analysis of the tumor-immune microenvironment reveals predictors of outcome in triple-negative breast cancer. Commun Biol. (2021) 4:852. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02361-1

57. Liu CC, Bosse M, Kong A, Kagel A, Kinders R, Hewitt SM, et al. Reproducible, high-dimensional imaging in archival human tissue by multiplexed ion beam imaging by time-of-flight (MIBI-TOF). Lab Invest. (2022) 102:762–70. doi: 10.1038/s41374-022-00778-8

58. Kuswanto W, Nolan G, and Lu G. Highly multiplexed spatial profiling with CODEX: bioinformatic analysis and application in human disease. In: Seminars in immunopathology, vol. 45. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin/Heidelberg (2023). p. 145–57.

59. Zhang P, Zhang H, Tang J, Ren Q, Zhang J, Chi H, et al. The integrated single-cell analysis developed an immunogenic cell death signature to predict lung adenocarcinoma prognosis and immunotherapy. Aging (Albany NY). (2023) 15:10305. doi: 10.18632/aging.205077

60. Semba T and Ishimoto T. Spatial analysis by current multiplexed imaging technologies for the molecular characterisation of cancer tissues. Br J Cancer. (2024) 131:1737–47. doi: 10.1038/s41416-024-02882-6

61. Zhang SK, Jiang L, Jiang CL, Cao Q, Chen YQ, and Chi H. Unveiling genetic susceptibility in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and revolutionizing pancreatic cancer diagnosis through imaging. World J Gastrointestinal Oncol. (2025) 17:102544. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v17.i6.102544

62. Bilusic M, Heery CR, Collins JM, Donahue RN, Palena C, Madan RA, et al. Phase I trial of HuMax-IL8 (BMS-986253), an anti-IL-8 monoclonal antibody, in patients with metastatic or unresectable solid tumors. J immunotherapy Cancer. (2019) 7:240. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0706-x

63. Mitra S, Malik R, Wong W, Rahman A, Hartemink AJ, Pritykin Y, et al. Single-cell multi-ome regression models identify functional and disease-associated enhancers and enable chromatin potential analysis. Nat Genet. (2024) 56:627–36. doi: 10.1038/s41588-024-01689-8

64. Yuan K, Zhao S, Ye B, Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhang P, et al. A novel T-cell exhaustion-related feature can accurately predict the prognosis of OC patients. Front Pharmacol. (2023) 14:1192777. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1192777

65. Liu R, Liu J, Cao Q, Chu Y, Chi H, Zhang J, et al. Identification of crucial genes through WGCNA in the progression of gastric cancer. J Cancer. (2024) 15:3284. doi: 10.7150/jca.95757

66. Wang X, Wu X, Hong N, and Jin W. Progress in single-cell multimodal sequencing and multi-omics data integration. Biophys Rev. (2024) 16:13–28. doi: 10.1007/s12551-023-01092-3

67. Lee S, Kim G, Lee J, Lee AC, and Kwon S. Mapping cancer biology in space: applications and perspectives on spatial omics for oncology. Mol Cancer. (2024) 23:26. doi: 10.1186/s12943-024-01941-z

68. Gong Y, Bao L, Xu T, Yi X, Chen J, Wang S, et al. The tumor ecosystem in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and advances in ecotherapy. Mol Cancer. (2023) 22:68. doi: 10.1186/s12943-023-01769-z

69. Adimi Y, Levin C, Lombardi EP, Classe M, and Badoual C. A new spatial multi-omics approach to deeply characterize human cancer tissue using a single slide: a new spatial muti-omics approach to deeply characterize human cancer tissue using a single slide. Cancer Res. (2025) 85:7483–3. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2025-7483

70. Wu M, Tao H, Xu T, Zheng X, Wen C, Wang G, et al. Spatial proteomics: unveiling the multidimensional landscape of protein localization in human diseases. Proteome Sci. (2024) 22:7. doi: 10.1186/s12953-024-00231-2

71. Yan Z, Fan KQ, Zhang Q, Wu X, Chen Y, Wu X, et al. Comparative analysis of the performance of the large language models DeepSeek-V3, DeepSeek-R1, open AI-O3 mini and open AI-O3 mini high in urology. World J Urol. (2025) 43:416. doi: 10.1007/s00345-025-05757-4

72. Tan CW, Berrell N, Donovan ML, Monkman J, Lawler C, Sadeghirad H, et al. The development of a high-plex spatial proteomic methodology for the characterisation of the head and neck tumour microenvironment. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2025) 9:191. doi: 10.1038/s41698-025-00963-0

73. Antoranz A, Van Herck Y, Bolognesi MM, Lynch SM, Rahman A, Gallagher WM, et al. Mapping the immune landscape in metastatic melanoma reveals localized cell–cell interactions that predict immunotherapy response. Cancer Res. (2022) 82:3275–90. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-0363

74. Li Z, Mirjahanmardi SH, Sali R, Eweje F, Gopaulchan M, Kloker L, et al. Automated cell annotation and classification on histopathology for spatial biomarker discovery. Nat Commun. (2025) 16:6240. doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-61349-1

75. Williams HL, Frei AL, Koessler T, Berger MD, Dawson H, Michielin O, et al. The current landscape of spatial biomarkers for prediction of response to immune checkpoint inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2024) 8:178. doi: 10.1038/s41698-024-00671-1

76. Liu W, Xia L, Peng Y, Cao Q, Xu K, Luo H, et al. Unraveling the significance of cuproptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma heterogeneity and tumor microenvironment through integrated single-cell sequencing and machine learning approaches. Discover Oncol. (2025) 16:900. doi: 10.1007/s12672-025-02696-9

77. Choi JH, Lee BS, Jang JY, Lee YS, Kim HJ, Roh J, et al. Single-cell transcriptome profiling of the stepwise progression of head and neck cancer. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1055. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36691-x

78. Heller G, Fuereder T, Grandits AM, and Wieser R. New perspectives on biology, disease progression, and therapy response of head and neck cancer gained from single cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics. Oncol Res. (2023) 32:1. doi: 10.32604/or.2023.044774

79. Huang Q, Wang F, Hao D, Li X, Li X, Lei T, et al. Deciphering tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells in the single-cell era. Exp Hematol Oncol. (2023) 12:97. doi: 10.1186/s40164-023-00459-2

80. Zhong J, Xing X, Gao Y, Pei L, Lu C, Sun H, et al. Distinct roles of TREM2 in central nervous system cancers and peripheral cancers. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:968–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.05.001

81. Molgora M, Liu YA, Colonna M, and Cella M. TREM2: A new player in the tumor microenvironment. In: Seminars in immunology, vol. 67. Elsevier: Academic Press (2023). p. 101739.

82. Li J, Zhou J, Huang H, Jiang J, Zhang T, and Ni C. Mature dendritic cells enriched in immunoregulatory molecules (mregDCs): a novel population in the tumour microenvironment and immunotherapy target. Clin Trans Med. (2023) 13:e1199. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.1199

83. Ma T, Chu X, Wang J, Li X, Zhang Y, Tong D, et al. Pan-cancer analyses refine the single-cell portrait of tumor-infiltrating dendritic cells. Cancer Res. (2025) 85(19):3596–613. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.30255751

84. Cilento MA, Sweeney CJ, and Butler LM. Spatial transcriptomics in cancer research and potential clinical impact: a narrative review. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2024) 150:296. doi: 10.1007/s00432-024-05816-0

85. Chen B, Fan H, Pang X, Shen Z, Gao R, Wang H, et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics reveals an anti-tumor neutrophil subgroup in microwave thermochemotherapy-treated lip cancer. Int J Oral Sci. (2025) 17:40. doi: 10.1038/s41368-025-00366-8

86. Li C, Guo H, Zhai P, Yan M, Liu C, Wang X, et al. Spatial and single-cell transcriptomics reveal a cancer-associated fibroblast subset in HNSCC that restricts infiltration and antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. (2024) 84:258–75. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-1448

87. Jiang D, Wu X, Deng Y, Yang X, Wang Z, Tang Y, et al. Single-cell profiling reveals conserved differentiation and partial EMT programs orchestrating ecosystem-level antagonisms in head and neck cancer. J Cell Mol Med. (2025) 29:e70575. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.70575

88. Liu YT, Liu HM, Ren JG, Zhang W, Wang XX, Yu ZL, et al. Immune-featured stromal niches associate with response to neoadjuvant immunotherapy in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Rep Med. (2025) 6:102024. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2025.102024

89. Chen N, Vohra M, and Saladi SV. Protocol for Bulk-ATAC sequencing in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. STAR Protoc. (2023) 4:102233. doi: 10.1016/j.xpro.2023.102233

90. Shi ZD, Pang K, Wu ZX, Dong Y, Hao L, Qin JX, et al. Tumor cell plasticity in targeted therapy-induced resistance: mechanisms and new strategies. Signal Transduction Targeted Ther. (2023) 8:113. doi: 10.1038/s41392-023-01383-x

91. Chen C, Liu J, Chen Y, Lin A, Mou W, Zhu L, et al. Application of ATAC-seq in tumor-specific T cell exhaustion. Cancer Gene Ther. (2023) 30:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41417-022-00495-w

92. Adimi Y, Levin C, Lombardi EP, Classe M, and Badoual C. A new spatial multi-omics approach to deeply characterize human cancer tissue using a single slide: a new spatial muti-omics approach to deeply characterize human cancer tissue using a single slide. Cancer Res. (2025) 85:7483–3. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2025-7483

93. Wu C, Zhang G, Wang L, Hu J, Ju Z, Tao H, et al. Spatial proteomic profiling elucidates immune determinants of neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. (2024) 43:2751–67. doi: 10.1038/s41388-024-03123-z

94. Williams HL, Frei AL, Koessler T, Berger MD, Dawson H, Michielin O, et al. The current landscape of spatial biomarkers for prediction of response to immune checkpoint inhibition. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2024) 8:178. doi: 10.1038/s41698-024-00671-1

95. de Souza N, Zhao S, and Bodenmiller B. Multiplex protein imaging in tumour biology. Nat Rev Cancer. (2024) 24:171–91. doi: 10.1038/s41568-023-00657-4

96. Wang X, Wu X, Hong N, and Jin W. Progress in single-cell multimodal sequencing and multi-omics data integration. Biophys Rev. (2024) 16:13–28. doi: 10.1007/s12551-023-01092-3

Keywords: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, myeloid reprogramming, single-cell RNA/ATAC, spatial transcriptomics, checkpoint blockade, PD-1/PD-L1

Citation: Luo R, Yang J, Cao Z and Li B (2025) Myeloid-driven immunosuppression in head and neck cancer: single-cell ATAC/RNA and spatial transcriptomic perspectives. Front. Oncol. 15:1693152. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1693152

Received: 26 August 2025; Accepted: 13 November 2025; Revised: 31 October 2025;

Published: 18 December 2025.

Edited by:

John Maher, King’s College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Shaoqiu Chen, University of Hawaii at Mānoa, United StatesJinyan Yang, Southwest Medical University, China

Copyright © 2025 Luo, Yang, Cao and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zimeng Cao, bTE4NTgwNTY4MTg4QDE2My5jb20=; Bing Li, ZGNsaWJpbmdAc2luYS5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Rui Luo

Rui Luo Jianzheng Yang

Jianzheng Yang Zimeng Cao3,4*

Zimeng Cao3,4*