- 1Guangdong Cardiovascular Institute, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital, Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (Guangdong Academy of Medical Sciences), Southern Medical University, Guangzhou, China

Background: Ovarian cancer (OC) remains a lethal gynecologic cancer marked by substantially reduced 5-year survival probabilities. Elevated BMI (≥25 kg/m²) constitutes a progressively recognized OC risk determinant mediated by chronic inflammatory states and metabolic pathway perturbations. Leveraging GBD 2021 repositories, this investigation quantified high BMI-attributable ovarian cancer burden trajectories among reproductive-age women (WCBA, 15–49 years) worldwide.

Methods: Leveraging GBD 2021 repositories, we evaluated worldwide OC burden mediated by elevated BMI across women of childbearing age (WCBA) during 1990-2021. Evaluated metrics comprised deaths, DALYs, YLDs, YLLs, and ASR (EAPC-based trend analysis). ARIMA and Exponential Smoothing models generated 2050 burden projections.

Results: From 1990 to 2021, the global burden of OC attributable to high BMI increased significantly. In 2021, there were 17,344 deaths (95% UI: 4,141–30,810) and 477,248 DALYs (95% UI: 113,449–840,002) among WCBA. The ASMR rose from 0.32 (95% UI: 0.07–0.61) to 0.38 (95% UI: 0.09–0.67) per 100,000 (EAPC: 1.03, 95% CI: 0.85–1.21). The ASDR increased from 8.72 (95% UI: 1.78–16.41) to 10.56 (95% UI: 2.50–18.57) per 100,000 (EAPC: 1.09, 95% CI: 0.93–1.25). The burden peaked in the 45–49 age group, with 995 deaths and 44,223 DALYs. High SDI regions had the highest ASMR (0.57, 95% UI: 0.14–1.01) and ASDR (15.13, 95% UI: 3.79–26.82). Projections indicate a continued increase in the OC burden attributable to high BMI by 2050, with the ASMR reaching 0.43 (95% HDI: 0.40–0.46) and the ASDR reaching 12.28 (95% HDI: 11.58–12.98).

Conclusion: This study highlights the escalating global burden of OC attributable to high BMI among WCBA, particularly in high SDI regions. This investigation delineates progressively intensifying worldwide OC burden mediated by elevated BMI in WCBA, disproportionately affecting high SDI territories.

Introduction

Among gynecological malignancies worldwide, ovarian cancer (OC) maintains exceptionally poor survival outcomes, with 5-year survival rates substantially below those of comparable female reproductive tract cancers (1, 2). The elevated mortality associated with OC is predominantly attributable to advanced-stage diagnosis, with current epidemiological data indicating a 5-year survival rate of merely 47% (3). However, accumulating empirical evidence underscores the role of BMI modulation (body mass index) in ovarian carcinogenesis (4). The standard BMI metric derives from the quotient of weight (kg) and height squared (m²), where values >25 kg/m² indicate clinically significant elevation according to WHO classification (5). Mechanistic investigations have revealed that genetic predisposition (e.g., BRCA1/2 mutations) and endocrine dysregulation (particularly estrogen-progesterone axis alterations) contribute to OC pathogenesis (6). Specifically, OC pathogenesis and disease progression are substantially influenced by persistent inflammatory states resulting from obesity, manifesting as insulin pathway dysregulation and adipokine homeostasis impairment (7, 8). At the same time, BMI is an indirect proxy of adiposity and metabolic risk and does not capture body fat distribution or lean mass; recent work demonstrates that body-composition phenotypes and visceral adiposity can be more strongly associated with cancer outcomes, including ovarian cancer, than BMI alone (34, 35). Moreover, meta-analytic evidence indicates that the relationship between anthropometric factors and OC risk differs across histologic subtypes and menopausal status, underscoring the biological heterogeneity underlying adiposity–OC associations (33). To situate this work within the broader GBD 2021 landscape of female cancers, we note that breast cancer drives the highest incidence globally, cervical cancer patterns vary widely by screening and HPV vaccination coverage, uterine cancer has risen in tandem with adiposity, and ovarian cancer remains the most lethal among the four major female cancers; these context-setting trends are summarized in recent GBD-based syntheses (29).

Although these relationships are documented, methodologically robust investigations quantifying worldwide OC burden specifically linked to high BMI levels in 15–49 year old women remain scarce (9). While prior investigations have predominantly focused on regional populations or particular histopathological subtypes (e.g., serous epithelial OC), they have generally omitted the systematic integration of age-standardized mortality rates (ASMR), disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), and longitudinal projections (10). Moreover, variations among Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) quintiles and age-specific groups remain inadequately characterized, hindering the development of targeted preventive strategies (10). In global health and demographic reporting, women of childbearing age (WCBA) are conventionally defined as those aged 15–49 years, a period during which OC carries unique implications for fertility preservation, pregnancy planning, and long-term quality of life despite accounting for a minority of all OC deaths. In addition, the heterogeneity of adiposity–OC associations across histologic subtypes and menopausal categories highlighted by recent meta-analyses has not yet been translated into global, risk-attributable estimates for WCBA (33). In this context, by isolating high BMI–attributable OC burden in WCBA, our estimates are designed to complement all-age GBD 2021 analyses rather than replace them, and they should not be generalized to predominantly postmenopausal disease outside the 15–49-year range (29).

Utilizing the GBD 2021 database, this research quantifies historical trajectories (1990-2021) and models prospective burdens (2050 horizon) of ovarian cancer attributable to elevated BMI, directly targeting identified evidence gaps (11, 12). Systematic assessment of obesity-attributable OC mortality and morbidity burdens provides foundational evidence for developing targeted risk stratification frameworks and equitable resource distribution strategies across heterogeneous populations. By focusing specifically on WCBA (15–49 years), our analysis complements all-age GBD evaluations of gynecologic cancers, providing age-specific, high BMI–attributable estimates that are directly relevant to reproductive health policy and pre-/perimenopausal care (10, 29).

Materials and methods

Data source

The GBD 2021 repository (https://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-2021) constituted an extensive epidemiological resource quantifying disease burden impacts from 371 pathologies, 88 risk factors, and injuries spanning five Socio-Demographic Index (SDI) categories and 204 nations and territories. The SDI operates on a continuous scale of 0-1, where zero denotes minimal developmental attainment and unity indicates maximal development status. Countries and territories were classified into five groups based on SDI quintiles: high SDI (>0.81), high-middle SDI (0.70-0.81), middle SDI (0.61-0.69), low-middle SDI (0.46-0.60), and low SDI (<0.46) (13). Utilizing data from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2021 Study, we extracted global burden estimates for BMI-attributable OC among women of childbearing age (WCBA) covering the period 1990-2021. These estimates included deaths, disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), years lived with disability (YLDs), years of life lost (YLLs), and their corresponding age-standardized rates (ASR). In this study, women of childbearing age were defined as those aged 15–49 years, consistent with standard GBD age groupings. Within the GBD comparative risk assessment, “high BMI” is treated as a continuous risk factor defined in adults using BMI ≥ 25 kg/m², and ovarian cancer is modelled as a single cause without histologic or menopausal stratification. Our estimates therefore reflect the aggregated high BMI–attributable OC burden across all histologic subtypes occurring in women aged 15–49 years rather than subtype- or menopausal-status–specific effects.

Statistical analysis

The age-standardized mortality rate (ASMR), age-standardized DALYs rate (ASDR), age-standardized YLDs rate (ASYR) were utilized as indicators to evaluate the disease burden of OC attributable to high BMI. The Estimated Annual Percentage Change (EAPC) was used to analyze trends in ASR over a specified time interval. The formula for EAPC was calculated as:

where is the slope from the linear regression of the natural logarithm of the ASR on the year (14). Confidence interval (CI) of EAPC can be obtained from the linear regression model.

All statistical computations employed R software (v4.1.0). Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05. We computed 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) by extracting the 2.5th-97.5th percentile range across 1,000 posterior distribution iterations per estimation phase. Projections of the burden attributable to BMI for OC through 2050 were developed employing Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) and Exponential Smoothing (ES) modeling frameworks. These classical univariate time-series approaches were selected because they are widely applied to annual, non-linear disease trends and provide transparent parameterization and diagnostics. For each outcome (ASMR, ASDR, ASYR and YLLs), we fitted ARIMA and ES models to the 1990–2021 series following standard Box–Jenkins procedures, including visual inspection of temporal patterns, assessment of stationarity, and comparison of candidate model orders using information criteria to guide model selection. Residual diagnostics were examined to ensure that substantial autocorrelation was not present in the final models. For all projections we derived 95% prediction intervals (expressed as highest density intervals, HDIs), which are reported alongside point forecasts in the text. ARIMA and ES yielded qualitatively similar trajectories, providing internal consistency for our projections.

Results

The global burden of OC attributable to high BMI from 1990 to 2021

In 2021, there were 17344 (95% UI: 4141-30810) deaths among WCBA caused by OC attributable to high BMI, increased from 6850 (95% UI: 1422-12864) in 1990. Similarly, the DALYs for OC attributable to high BMI increased from 188874 (95% UI: 38401-355691) in 1990 to 477248 (95% UI: 113449-840002) in 2021 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trends in the global burden of OC attributable to high BMI from 1990 to 2021. Indicators include ASMR, ASDR and ASYR (rates per 100,000) and counts (deaths, DALYs, YLDs, YLLs) as applicable; where shown, uncertainty is 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs).

Figure 1 demonstrates progressive increases in ASMR, ASDR, and ASYR for high BMI-attributable OC from 1990-2021. Specifically, ASMR/100000 rose from 0.32 (95% UI: 0.07-0.61) in 1990 to 0.38 (95% UI: 0.09-0.67) in 2021, with EAPC 1.03 (95% CI: 0.85-1.21) (Table 1). Concurrently, ASDR/100000 increased from 8.72 (95% UI: 1.78-16.41) to 10.56 (95% UI: 2.5-18.57) over this period, yielding EAPC 1.09 (95% CI: 0.93-1.25) (Table 2). The Figure further illustrates YLLs, YLDs, and corresponding ASR trends.

Age-specific disease burden of OC attributable to high BMI from 1990 to 2021

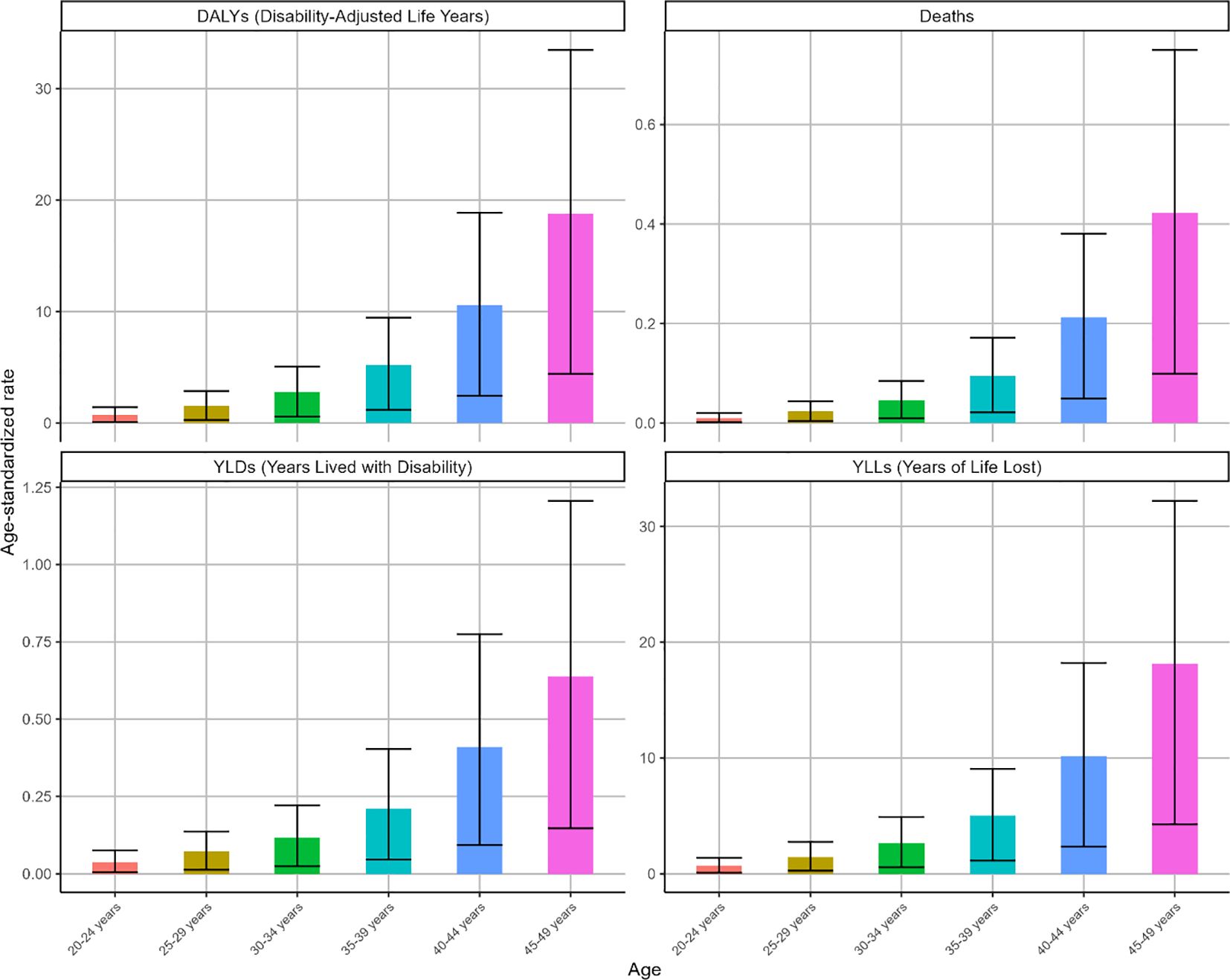

Globally, both deaths and DALYs for high BMI-attributable OC demonstrated age-dependent escalation in 2021 (Supplementary Figure S1), peaking within the 45–49 age cohort. Parallel trends were observed in ASMR and ASDR metrics. This age group recorded 995 deaths (95% UI: 234-1767) and 44223 DALYs (95% UI: 10412-78821), with an ASMR of 0.42 (95% UI: 0.1-0.75) and an ASDR of 18.77 (95% UI: 4.42-33.45) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The ASR of deaths, DALYs, YLDs and YLLs for OC attributable to high BMI by age in 2021. Indicators: age-specific ASMR and ASDR (per 100,000), with corresponding deaths and DALYs counts.

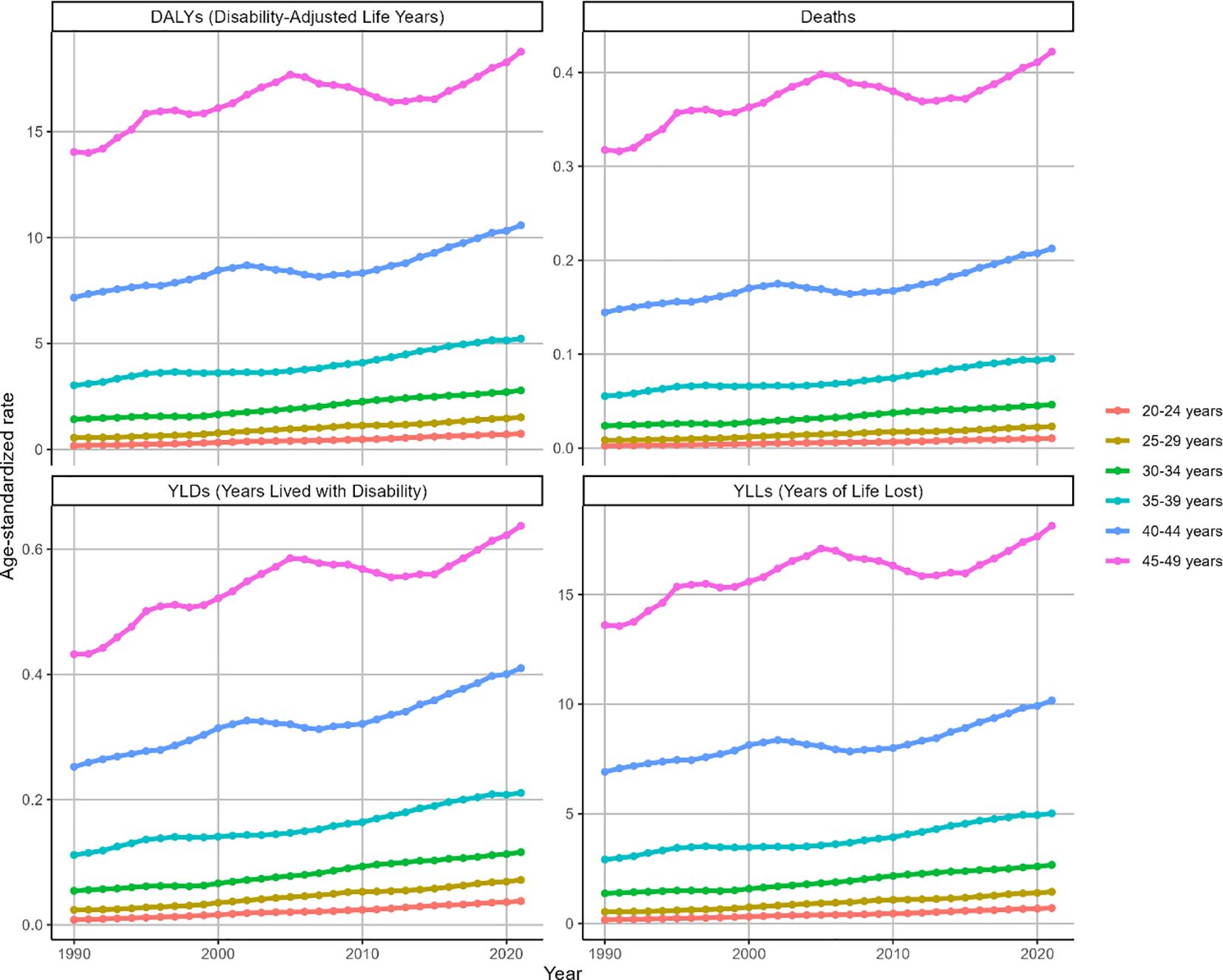

Globally, ASMR and ASDR for high BMI-attributable OC exhibited upward trajectories across all age groups during the observation period (Figure 3). Notably, while other cohorts demonstrated gradual increases, the 45–49 age group displayed distinct fluctuations: an initial ascent (1990-2005), subsequent decline (2005-2012), and marked resurgence (2012-2021). Overall, this cohort maintained upward trends in ASMR (EAPC = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.48-0.79) and ASDR (EAPC = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.49-0.8) as shown in Figure 3. Corresponding changes in deaths, DALYs, YLDs, and YLLs are presented in Supplementary Figure S2.

Figure 3. Trends in the ASR of deaths, DALYs, YLDs and YLLs for OC attributable to high BMI by age from 1990 to 2021. Trends shown for ASMR, ASDR, ASYR (per 100,000) and deaths, DALYs, YLDs, YLLs counts across age groups.

Disease burden of OC attributable to high BMI in different SDI regions and countries from 1990 to 2021

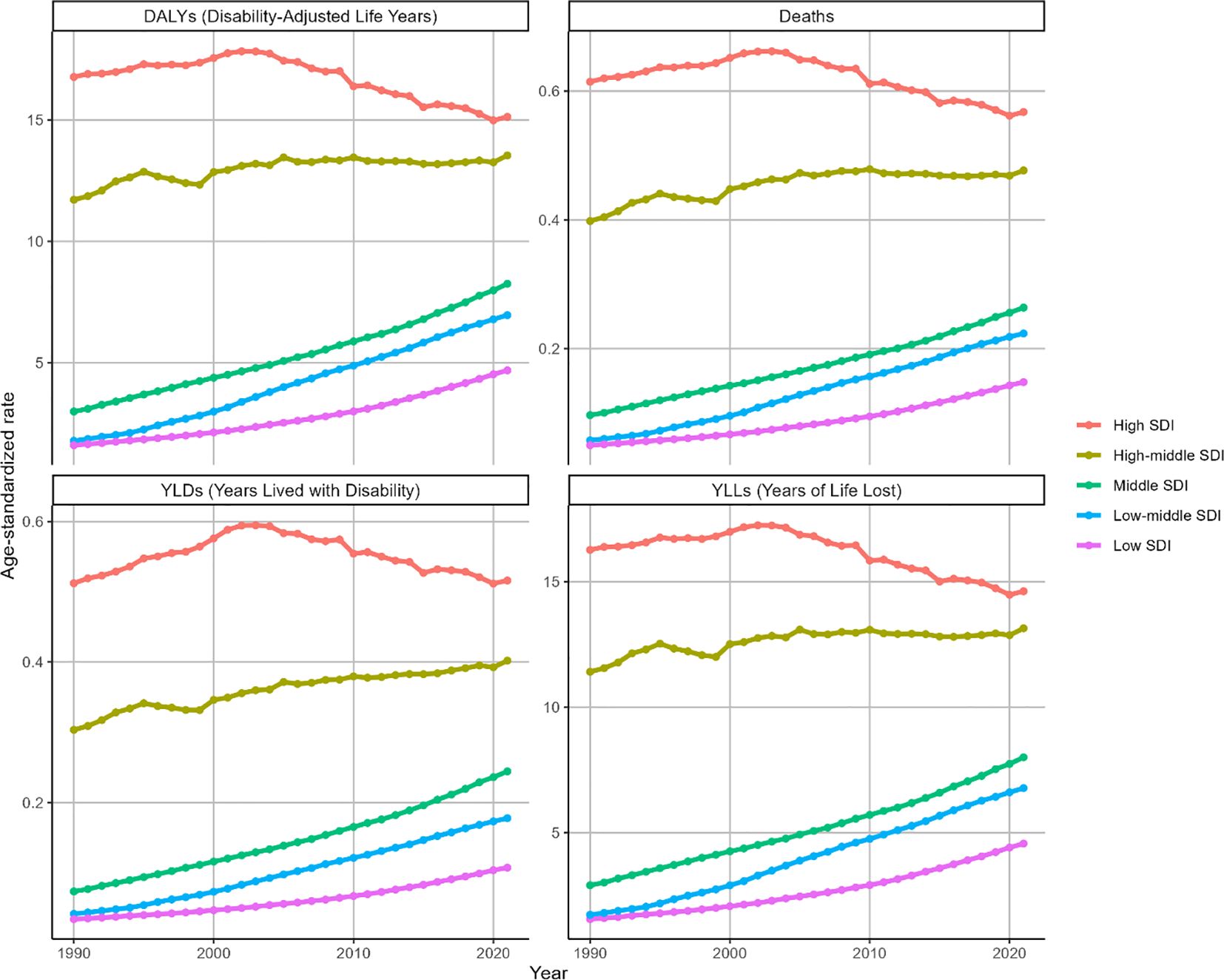

In 2021, low SDI regions recorded the minimal ASMR/100000 for BMI-attributable OC (0.15, 95% UI: 0.02-0.29), while high SDI regions exhibited the peak value (0.57, 95% UI: 0.14-1.01). A similar trend was seen for the ASDR (per 100,000) [low SDI regions (4.68, 95% UI: 0.74-9.04); high SDI region (15.13, 95% UI: 3.79-26.82)]. ASMR and ASDR for ovarian cancer demonstrated positive correlations with rising SDI levels globally (Supplementary Figure S3). Corresponding deaths and DALYs metrics are illustrated in Supplementary Figure S4.

During 1990-2021, ASMR for BMI-attributable OC exhibited significant upward trends across multiple SDI regions: low SDI (EAPC = 3.61, 95% CI: 3.52-3.7), lower-middle SDI (EAPC = 4.69, 95% CI: 4.49-4.89), middle SDI (EAPC = 3.16, 95% CI: 3.09-3.24), and high-middle SDI (EAPC = 0.47, 95% CI: 0.37-0.58). Notably, the high-middle SDI region demonstrated a comparatively attenuated increase. Conversely, high SDI regions displayed distinct patterns: gradual ASMR elevation from 1990 to 2003 (peak: 0.66, 95% UI: 0.16-1.21), followed by marked decline through 2021, culminating in an overall downward trajectory (EAPC=-0.36, 95% CI:-0.49–0.23) as depicted in Figure 4. Parallel ASDR trends are documented in Figure 4 and Table 2.

Figure 4. Trends in the ASR of deaths, DALYs, YLDs and YLLs for OC attributable to high BMI by SDI region from 1990 to 2021. Indicators: ASMR, ASDR, ASYR by SDI region (per 100,000), with matching deaths and DALYs counts.

In 2021, the highest ASMR for BMI-attributable OC occurred in United Arab Emirates (3.73, 95% UI: 1.05-6.55), Bahrain (1.35, 95% UI: 0.41-2.54), and Qatar (1.23, 95% UI: 0.38-2.27). Correspondingly, the top ASDR values were documented in United Arab Emirates (80.08, 95% UI: 22.77-140.04), Bahrain (36.75, 95% UI: 11.28-67.96), and Bahamas (35.80, 95% UI: 9.60-65.14) (Supplementary Figure S7). National variations in deaths, DALYs, YLDs, and YLLs are visualized in Supplementary Figure S6. During 1990-2021, ASMR declined in 12 nations but increased in 192, with Ecuador (EAPC = 9.36, 95% CI: 7.96-10.78), Republic of Korea (EAPC = 7.77, 95% CI: 7.23-8.31), and Indonesia (EAPC = 7.28, 95% CI: 6.86-7.69) showing the most rapid ascents. Similarly, ASDR decreased in 17 countries while rising in 187, where Ecuador (EAPC = 9.1, 95% CI: 7.7-10.52), Republic of Korea (EAPC = 7.34, 95% CI: 6.85-7.83), and Indonesia (EAPC = 6.97, 95% CI: 6.57-7.37) exhibited the steepest increases (Figure 5).

Figure 5. World map of EAPC for OC attributable to high BMI from 1990 to 2021. Choropleth maps report ASMR and ASDR (per 100,000) and EAPC as specified; to facilitate cross-figure comparison, color-scale categories are harmonized across all world maps (see also Supplementary Figures S6, S7).

Projections to 2050 on the burden of OC attributable to high BMI

ARIMA model projections indicate a steady rise in ASMR for BMI-attributable OC from 2022-2050, reaching 0.43 (95% HDI: 0.40–0.46) by 2050. Conversely, obesity-attributable OC deaths are projected to decline during this period. The ASR of YLLs parallels ASMR trajectories, while DALYs demonstrate significant elevation from 2022 onward. ASDR shows moderate but consistent growth, attaining 12.28 (95% HDI: 11.58-12.98) by 2050, with ASYR exhibiting analogous trends as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 6. The projection of the burden for OC attributable to high BMI from 2022 to 2050 worldwide by using ARIMA model. Projections shown for ASMR, ASDR and other outcomes where applicable; point forecasts are presented alongside 95% prediction intervals.

ES model projections forecast a moderate yet consistent rise in BMI-attributable OC ASMR, reaching 0.38 (95% HDI: 0.35–0.41) by 2050. Conversely, obesity-driven OC deaths are projected to decline at rates marginally exceeding ARIMA model predictions. ASR of YLLs closely parallels ASMR trajectories, while DALYs demonstrate substantial elevation during 2022-2050. ASDR exhibits gradual growth, attaining 11.16 (95% HDI: 9.36-12.95) by 2050, with ASYR showing analogous progression as illustrated in Supplementary Figure S8.

Discussion

Employing the GBD framework, we quantify global OC burdens associated with excessive BMI in 15–49 year females across 1990-2021, with modeling extending to 2050. This investigation reveals an intensifying burden disproportionately affecting high and upper-middle SDI territories. The evidence mandates tailored interventions targeting escalating OC rates and deaths attributable to clinically significant obesity.

Attributable to elevated BMI, worldwide OC burden has demonstrated substantial growth since 1990, revealing pronounced interregional divergences. Distinct disease burden gradients are observed, with North American and Western European high-SDI populations demonstrating significantly greater age-standardized incidence and mortality versus low/low-middle SDI counterparts (15, 16). This trend aligns with established epidemiological patterns linking socioeconomic development to obesity-related cancers, where sedentary lifestyles and calorie-dense diets drive metabolic dysregulation (17, 18). Conversely, low-SDI regions demonstrate a concerning upward trajectory in BMI-attributable OC burden despite lower baseline rates, emphasizing the urgency of implementing cost-effective screening programs in resource-limited settings (19).

Age-specific analyses reveal peak disease burden in the 45–49 age group, consistent with ovarian cancer’s propensity for late-stage presentation (20). This finding supports intensified screening protocols (e.g., transvaginal ultrasound with CA-125 testing) and lifestyle counseling for perimenopausal women (21). Younger WCBA populations may benefit from preventive education on weight management, while postmenopausal women require enhanced surveillance given diagnostic challenges in this demographic (22).

Significantly, this analysis identified diverging future trajectories: a continuing upward trajectory in OC incidence contrasted with progressive mortality burden reduction. The documented mortality reduction likely reflects refinements in cytoreductive surgery protocols, particularly the adoption of intraoperative tumor mapping and R0 resection criteria, which collectively enhance therapeutically meaningful cytoreduction outcomes (23). Bevacizumab and PARP inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib) exhibit therapeutic synergy, yielding substantial survival gains in OC through prolonged PFS and OS durations—especially within homologous recombination-deficient cohorts where VEGF blockade augments DNA repair pathway suppression (24, 25). Emerging immune checkpoint modulators (including PD-1/PD-L1 antagonists) in active clinical development show potential to extend survival outcomes alongside platinum-taxane chemotherapy regimens (26, 27). Given the globally escalating BMI trends, implementing multifaceted public health interventions becomes imperative. Promoting physical activity, optimizing dietary patterns (e.g., Mediterranean diet adoption), and enhancing accessibility to preventive healthcare services constitute critical strategies for mitigating the future burden of OC (28).

Our findings align with other global burden studies that underscore the escalating trend of obesity-related cancers (29). Empirical evidence indicates marked breast cancer incidence escalation linked to BMI elevation, underscoring metabolic dysregulation’s central contribution to cancer pathogenesis (30). Independent research reveals hyperglycemia-associated OC burden escalation, confirming metabolic dysregulation’s pivotal role in shaping global oncological disease patterns (31). Collectively, these studies highlight the critical need to address metabolic risk factors to effectively mitigate the growing global cancer burden (32).

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, by design, we restricted the analysis to women aged 15–49 years. Although this age range corresponds to the conventional definition of WCBA used in global health reporting and is of particular relevance for reproductive health, most OC cases and deaths occur after age 50. Our results cannot be generalized to the full lifetime burden of OC and should be interpreted as quantifying the high BMI–attributable component of OC burden among pre- and perimenopausal women, complementing all-age GBD analyses (10, 29). Second, because GBD 2021 provides cause-level OC estimates without histologic or menopausal stratification, we were unable to investigate the known heterogeneity of adiposity–OC associations across histologic subtypes and menopausal status (33). Third, high BMI was the only adiposity indicator consistently available in the GBD comparative risk assessment; more refined measures of body composition and fat distribution have been shown to be stronger predictors of cancer outcomes but are not yet available at the global time-series scale required for our approach (34, 35). Fourth, we focused on high BMI as a single risk factor and did not formally model the joint or mediating effects of other metabolic and lifestyle exposures (e.g., high fasting glucose, physical inactivity, diet) and health-system determinants. Recent cluster-based analyses of gynecologic cancers and large-scale machine learning–Mendelian randomization frameworks illustrate how multifactorial, data-driven approaches can extend beyond the single-risk-factor design used here (36, 37). Our projections should therefore be interpreted as a conservative, BMI-specific component of the future OC burden among WCBA rather than a comprehensive model of all contributing determinants.

Conclusion

Collectively, this investigation delineates a progressively intensifying worldwide OC burden mediated by elevated BMI in WCBA. These findings necessitate precision-based interventions disproportionately targeting high-SDI settings, aiming to counteract expanding adiposity epidemics and their oncological impact. By informing evidence-based policies and advocating for lifestyle modifications, we can strive to diminish the future impact of this devastating disease. Subsequent research must prioritize delineating adiposity-oncogenesis pathways and formulating risk-tailored preventive frameworks to optimize global female health trajectories.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

HC: Writing – original draft. ZL: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. JC: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SH: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.82403298) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2025A1515011933).

Conflict of interest

The authors declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1695717/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Azangou-Khyavy M, Ghasemi E, Rezaei N, Khanali J, Kolahi AA, Malekpour MR, et al. Global, regional, and national quality of care index of cervical and ovarian cancer: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 1990-2019. BMC Womens Health. (2024) 24:69. doi: 10.1186/s12905-024-02884-9

2. Collins Y, Holcomb K, Chapman-Davis E, Khabele D, and Farley JH. Gynecologic cancer disparities: a report from the Health Disparities Taskforce of the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Gynecol Oncol. (2014) 133:353–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.039

3. Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. Ca-Cancer J Clin. (2018) 68:284–96. doi: 10.3322/caac.21456

4. Argyrakopoulou G, Dalamaga M, Spyrou N, and Kokkinos A. Gender differences in obesity-related cancers. Curr Obes Rep. (2021) 10:100–15. doi: 10.1007/s13679-021-00426-0

5. Zhou XD, Chen QF, Yang W, Zuluaga M, Targher G, Byrne CD, et al. Erratum: Burden of disease attributable to high body mass index: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Eclinicalmedicine. (2024) 78:102958. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102958

6. Norquist BM, Pennington KP, Agnew KJ, Harrell MI, Pennil CC, Lee MK, et al. Characteristics of women with ovarian carcinoma who have BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations not identified by clinical testing. Gynecol Oncol. (2013) 128:483–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.015

7. Khalid M, Alkaabi J, Khan M, and Adem A. Insulin signal transduction perturbations in insulin resistance. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22:8590. doi: 10.3390/ijms22168590

8. Kawai T, Autieri MV, and Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol-Cell Ph. (2021) 320:C375–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00379.2020

9. Cen J, Wang Q, Cheng L, Gao Q, Wang H, and Sun F. Global, regional, and national burden and trends of migraine among women of childbearing age from 1990 to 2021: insights from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. J Headache Pain. (2024) 25:96. doi: 10.1186/s10194-024-01798-z

10. Li Y, Song W, Gao P, Guan X, Wang B, Zhang L, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of breast, cervical, uterine, and ovarian cancer and their risk factors among women from 1990 to 2021, and projections to 2050: findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. BMC Cancer. (2025) 25:330. doi: 10.1186/s12885-025-13741-9

11. Wu Z, Xia F, and Lin R. Global burden of cancer and associated risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1980-2021: a systematic analysis for the GBD 2021. J Hematol Oncol. (2024) 17:119. doi: 10.1186/s13045-024-01640-8

12. Murray C. Findings from the global burden of disease study 2021. Lancet. (2024) 403:2259–62. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00769-4

13. Wang P, Huang S, Wang R, Shi X, Xu H, Peng J, et al. Global burden and cross-country inequalities in diseases associated with high body mass index from 1990 to 2019: Result from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J Glob Health. (2024) 14:4200. doi: 10.7189/jogh.14.04200

14. Zi H, He SH, Leng XY, Xu XF, Huang Q, Weng H, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of kidney, bladder, and prostate cancers and their attributable risk factors, 1990-2019. Military Med Res. (2021) 8:60. doi: 10.1186/s40779-021-00354-z

15. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca-Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

16. Lin Z, Gan M, Wang X, and Su Z. Burden of uterine cancer in China from 1990 to 2021 and 15-year projection: a systematic analysis and comparison with global levels. Reprod Health. (2024) 21:144. doi: 10.1186/s12978-024-01882-2

17. Pati S, Irfan W, Jameel A, Ahmed S, and Shahid RK. Obesity and cancer: A current overview of epidemiology, pathogenesis, outcomes, and management. Cancers. (2023) 15:485. doi: 10.3390/cancers15020485

18. Anekwe CV, Jarrell AR, Townsend MJ, Gaudier GI, Hiserodt JM, and Stanford FC. Socioeconomics of obesity. Curr Obes Rep. (2020) 9:272–9. doi: 10.1007/s13679-020-00398-7

19. Feng X, Li R, Yi H, Chen S, Liu M, and Wu Y. Global cancer burden attributable to excess body weight, 1990 to 2021, decomposed by population size, aging, and epidemiological change. Obesity. (2025) 33:567–77. doi: 10.1002/oby.24219

20. Han X, Wang Z, Huang D, Deng K, Wang Q, Li C, et al. Analysis of the disease burden trend of Malignant tumors of the female reproductive system in China from 2006 to 2020. BMC Womens Health. (2022) 22:504. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-02104-2

21. Duan H, Liu X, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Ji Y, Zhang Y, et al. Risk-stratified CA125 screening integrating CA125 trajectories, trajectory-specific progression and transvaginal ultrasound for ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. (2024) 17:210. doi: 10.1186/s13048-024-01535-9

22. Chien J and Poole EM. Ovarian cancer prevention, screening, and early detection: report from the 11th biennial ovarian cancer research symposium. Int J Gynecol Cancer. (2017) 27:S20–2. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000001118

23. Colombo N, Sessa C, du Bois A, Ledermann J, McCluggage WG, McNeish I, et al. ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent diseasedagger. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:672–705. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz062

24. Bartoletti M, Pelizzari G, Gerratana L, Bortot L, Lombardi D, Nicoloso M, et al. Bevacizumab or PARP-inhibitors maintenance therapy for platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: A network meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:3805. doi: 10.3390/ijms21113805

25. Suh YJ, Lee B, Kim K, Jeong Y, Choi HY, Hwang SO, et al. Bevacizumab versus PARP-inhibitors in women with newly diagnosed ovarian cancer: a network meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. (2022) 22:346. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09455-x

26. Peng H, Romero DM, and Horvat EA. Dynamics of cross-platform attention to retracted papers. P Natl Acad Sci USA. (2022) 119:e2119086119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2119086119

27. Tatsuki S, Shoji T, Abe M, Tomabechi H, Takatori E, Kaido Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of platinum rechallenge in patients with platinum-resistant ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer: A multicenter retrospective study. Anticancer Res. (2022) 42:4603–10. doi: 10.21873/anticanres.15964

28. Yanachkova V, Staynova R, Stoev S, and Naseva E. Benefits of using a microencapsulated vitamin D delivery system in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Hosp Pharm. (2023) 30:284–7. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2021-002967

29. Li T, Zhang H, Lian M, He Q, Lv M, Zhai L, et al. Global status and attributable risk factors of breast, cervical, ovarian, and uterine cancers from 1990 to 2021. J Hematol Oncol. (2025) 18:5. doi: 10.1186/s13045-025-01660-y

30. Dehesh T, Fadaghi S, Seyedi M, Abolhadi E, Ilaghi M, Shams P, et al. The relation between obesity and breast cancer risk in women by considering menstruation status and geographical variations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Womens Health. (2023) 23:392. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02543-5

31. Wu P, Jiang Q, Han L, and Liu X. Systematic analysis and prediction for disease burden of ovarian cancer attributable to hyperglycemia: a comparative study between China and the world from 1990 to 2019. Front Med-Lausanne. (2023) 10:1145487. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2023.1145487

32. Paul B, Hare DJ, Bishop DP, Paton C, Nguyen VT, Cole N, et al. Correction: Visualising mouse neuroanatomy and function by metal distribution using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry imaging. Chem Sci. (2016) 7:6576. doi: 10.1039/c6sc90060g

33. Ellwanger B, Schüler-Toprak S, Jochem C, Leitzmann MF, and Baurecht H. Anthropometric factors and the risk of ovarian cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Rep. (2022) 5:e1618. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.1618

34. Bradshaw PT. Body composition and cancer survival: a narrative review. Br J Cancer. (2024) 130:176–83. doi: 10.1038/s41416-023-02470-0

35. Davis EW, Attwood K, Prunier J, Paragh G, Joseph JM, Klein A, et al. The association of body composition phenotypes before chemotherapy with epithelial ovarian cancer mortality. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2024) 116:1513–24. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djae112

36. Cuello MA, Gomez-Valenzuela F, Wichmann I, and Olawaiye AB. Global determinants of gynecologic cancer incidence and mortality: A cluster-based analysis with predictive insights. Int J Gynecol Obstet. (2025) 171:23–36. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.70279

Keywords: BMI, disease burden, GBD 2021, ovarian cancer, women of childbearing age (WCBA)

Citation: Chen H, Lin Z, Chen J and He S (2025) Global burden of ovarian cancer attributable to high body mass index among women of childbearing age from 1990 to 2021 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Front. Oncol. 15:1695717. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1695717

Received: 01 September 2025; Accepted: 30 November 2025; Revised: 27 November 2025;

Published: 18 December 2025.

Edited by:

Eva Chalas, New York University, United StatesReviewed by:

Ming Yi, Zhejiang University, ChinaMauricio Cuello, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

Copyright © 2025 Chen, Lin, Chen and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shanyang He, Z2Rmc2NoeDIwMDBAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Hongxi Chen

Hongxi Chen Zidan Lin2†

Zidan Lin2† Shanyang He

Shanyang He