- 1Department of Nuclear Medicine, Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan, China

- 2Nuclear Medicine and Theranostics Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province, Luzhou, Sichuan, China

- 3Institute of Nuclear Medicine, Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan, China

Objective: This meta-analysis aims to evaluate the therapeutic efficacy and toxicity of 225Ac-DOTATATE in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs).

Methods: This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines. PubMed and Embase were searched to identify studies that met the inclusion criteria. The primary endpoints were the evaluation of therapeutic efficacy through disease response rates (DRRs) and disease control rates (DCRs), and then toxicity is assessed. Additionally, a subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate the influence of prior 177Lu-peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) on efficacy.

Results: This meta-analysis included five studies involving a total of 153 patients. The results showed that the DRR following 225Ac-DOTATATE treatment was 52% [95% confidence interval (CI): 43%–61%], and the DCR was 88% (95% CI: 81%–94%). The incidence of hematological toxicity was low at 2% (95% CI: 0.00%–5%), with only two patients experiencing Grade I–II renal toxicity, and no Grade III–IV toxicities were observed. Subgroup analysis indicated that patients who had previously received 177Lu-PRRT treatment had a DRR of 51% (95% CI: 35%–66%) and a DCR of 90% (95% CI: 69%–100%), while 177Lu-naive patients had a DRR of 47% (95% CI: 1%–97%) and a DCR of 89% (95% CI: 72%–100%).

Conclusion: Our preliminary analysis shows that 225Ac-DOTATATE is an effective and safe treatment option for advanced metastatic NETs, significantly improving patients’ quality of life and demonstrating considerable disease control even in cases where other treatments have failed.

Systematic review registration: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42025633806.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms originating from neuroendocrine cells, commonly occurring in the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and stomach. The incidence of NETs has been steadily increasing in recent years (1, 2). Traditional therapeutic approaches mainly include surgery, endocrine therapy, targeted chemotherapeutic agents, and radiochemotherapy (3). Despite recent progress in the diagnosis and treatment of NETs, therapeutic options remain limited for patients with advanced or metastatic disease, and their prognosis is generally poor, highlighting an urgent need for new treatment strategies (4).

Emerging peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) has garnered significant research attention due to its demonstrated efficacy in NET treatment, with radiolabeled somatostatin analogs (e.g., DOTATATE) being the most widely applied (5, 6). The β-emitting radionuclide 177Lu is currently the most commonly used, with 177Lu-DOTATATE receiving Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2018 for the treatment of metastatic NETs (5). However, studies have shown that even patients with high somatostatin receptor expression and an initially favorable response to 177Lu-DOTATATE eventually develop resistance to this β-emitting PRRT, resulting in disease progression (7, 8).

Targeted alpha therapy (TAT) has emerged as a promising alternative to β-emitting radionuclides, with 225Ac being the most widely studied alpha-emitting radionuclide (9, 10). Compared to 177Lu, 225Ac (T1/2 = 9.9 days), as a high-energy (5.8–8.4 MeV) and short-range (47–85 μm) alpha emitter, exhibits significantly higher linear energy transfer (LET ≈ 100 keV/μm), allowing for potent tumoricidal effects with relatively minimal damage to surrounding normal tissues (10–12). Preliminary studies suggest that 225Ac-DOTATATE offers superior potential in targeting NETs, making it a promising alternative to 177Lu-based therapies (13, 14).

However, clinical studies on 225Ac-DOTATATE for NETs remain limited, with small sample sizes and inconsistent findings. Thus, this meta-analysis aims to systematically evaluate the safety and efficacy of 225Ac-DOTATATE in the treatment of NETs, providing robust evidence for clinical practice and a reference for future TAT research.

Materials and methods

This systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (15). The registration number on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) is CRD42025633806.

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed and Embase from establishment to 15 December 2024. The search terms were as follows: “225Ac-DOTATATAE” AND (“neuroendocrine tumor” [Mesh] OR “neuroendocrine tumour*” OR “neuroendocrine neoplasm*” OR “neuroendocrine cancer*” OR “neuroendocrine carcinoma*”). Two researchers independently screened the literature and extracted data. Eventually, they selected the studies to be finally included and the data extraction results through a unanimous agreement. In case of disagreement, a third party is consulted in order to reach a consensus.

Study selection and quality assessment

The search was limited to human studies published in English. The studies discussed the treatment efficacy and toxicity of 225Ac-DOTATATE that meet the following criteria: (1) Patients confirmed neuroendocrine tumors by biopsy, laboratory examination, and imaging examination; (2) patients with incomplete or unresectable tumors, postoperative tumor recurrence, and distant metastases, as well as patients who were either treatment-naive or resistant to conventional therapies or 177Lu-PRRT were included; and (3) baseline 68Ga-DOTATATE/DOTANOC PET/CT scan showed high somatostatin receptor (SSTR) expression (uptake greater than the liver). Studies about animal experiments, cell studies, reviews, meta-analyses, replications, case reports, or letters were excluded. The quality of these studies was assessed based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series (16).

Data extraction

The data extracted from the chosen studies included the following: basic characteristics (the first author, publication time, treatment response criteria, number of patients, gender, type of primary tumor, Ki-67 index, previous treatment methods, and metastatic site), treatment details (dose, total cycles, interval time, follow-up time, and cumulative activity), and therapeutic efficacy, which included disease response rates (DRRs) and disease control rates (DCRs). The main outcomes are DRRs and DCRs as assessed by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.1 (RECIST 1.1) or PET Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.0 (PERCIST 1.0). DRRs were assessed by the proportion of complete response (CR) + partial response (PR); DCRs were assessed by the proportion of complete response (CR) + partial response (PR) + stable disease (SD). Potential toxicity was collected according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 5.0 (CTCAE5.0).

Statistical analysis

Stata16.0 was used for this meta-analysis. Generated forest plots were used for the analysis of DRRs and DCRs. I2 statistic was used for the heterogeneity test. If there was no significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 ≤ 50%, p < 0.10), a fixed-effects model was used to merge data. If there was significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 > 50%, p ≥ 0.10), the random-effects model was used to merge the data. In addition, subgroup analyses were carried out to explore the efficacy of patients who had previously received 177Lu PRRT. The funnel plot and Egger’s test were used to evaluate the publication bias of the studies, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Literature search

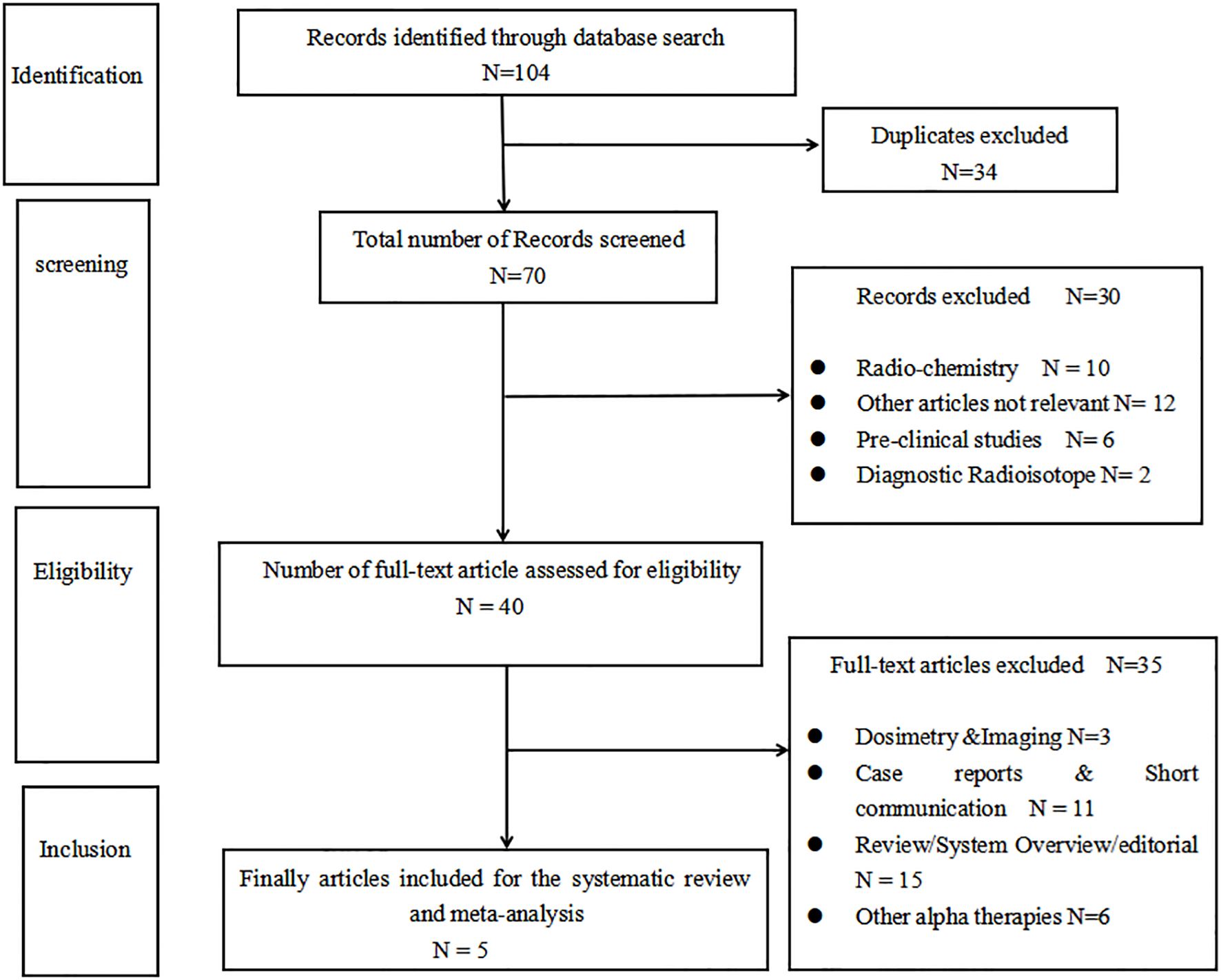

According to the search strategy, a total of 104 records were identified. Thirty-four duplicate records were excluded, and 30 articles were excluded by reading the title and the abstract. By further reading the full articles, five articles (17–21) that met the inclusion criteria were included. There is a flowchart that details how the articles were selected in Figure 1.

Quality assessment

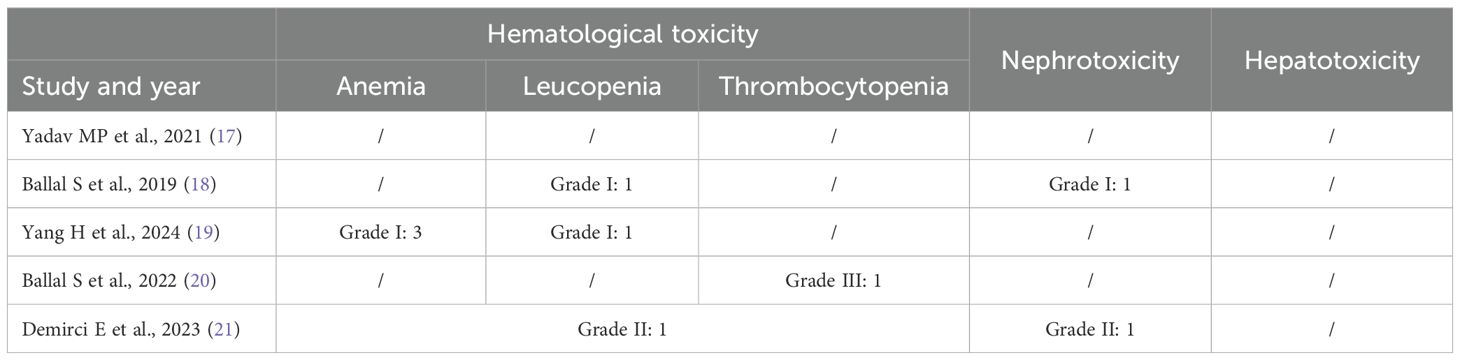

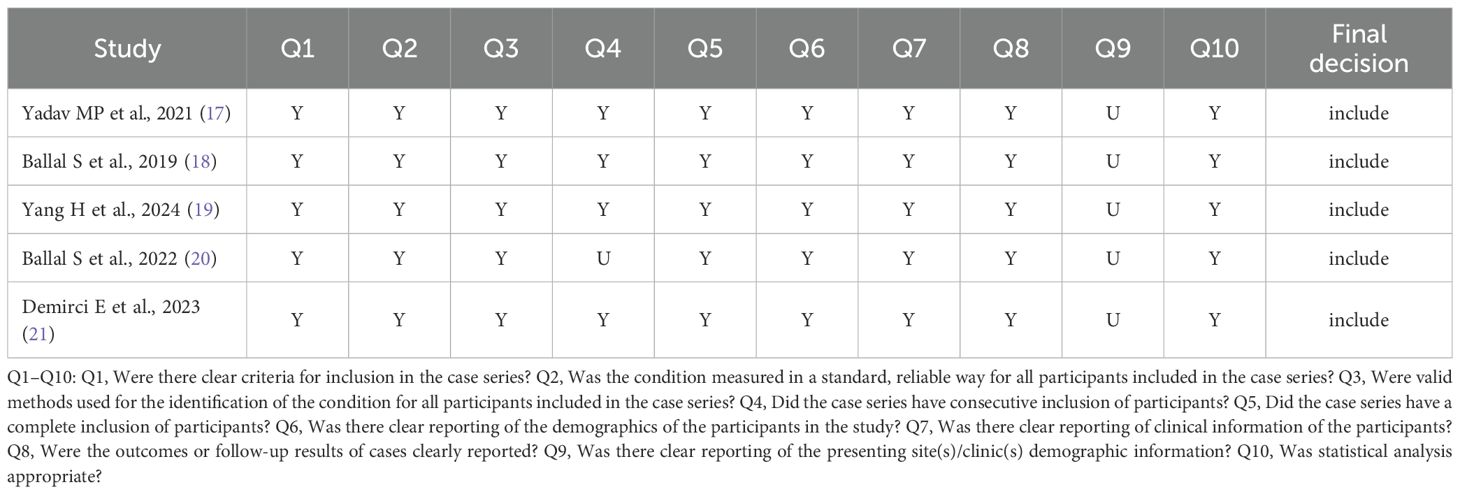

Based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series, five clinical studies were assessed, comprising 10 items. In Ballal et al., the case series that have consecutive inclusion of participants were not clear. The demographic information from the presenting sites/clinics was not clearly reported in all studies. The assessment results are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Quality assessment of the included studies based on the JBI critical appraisal checklist for case series.

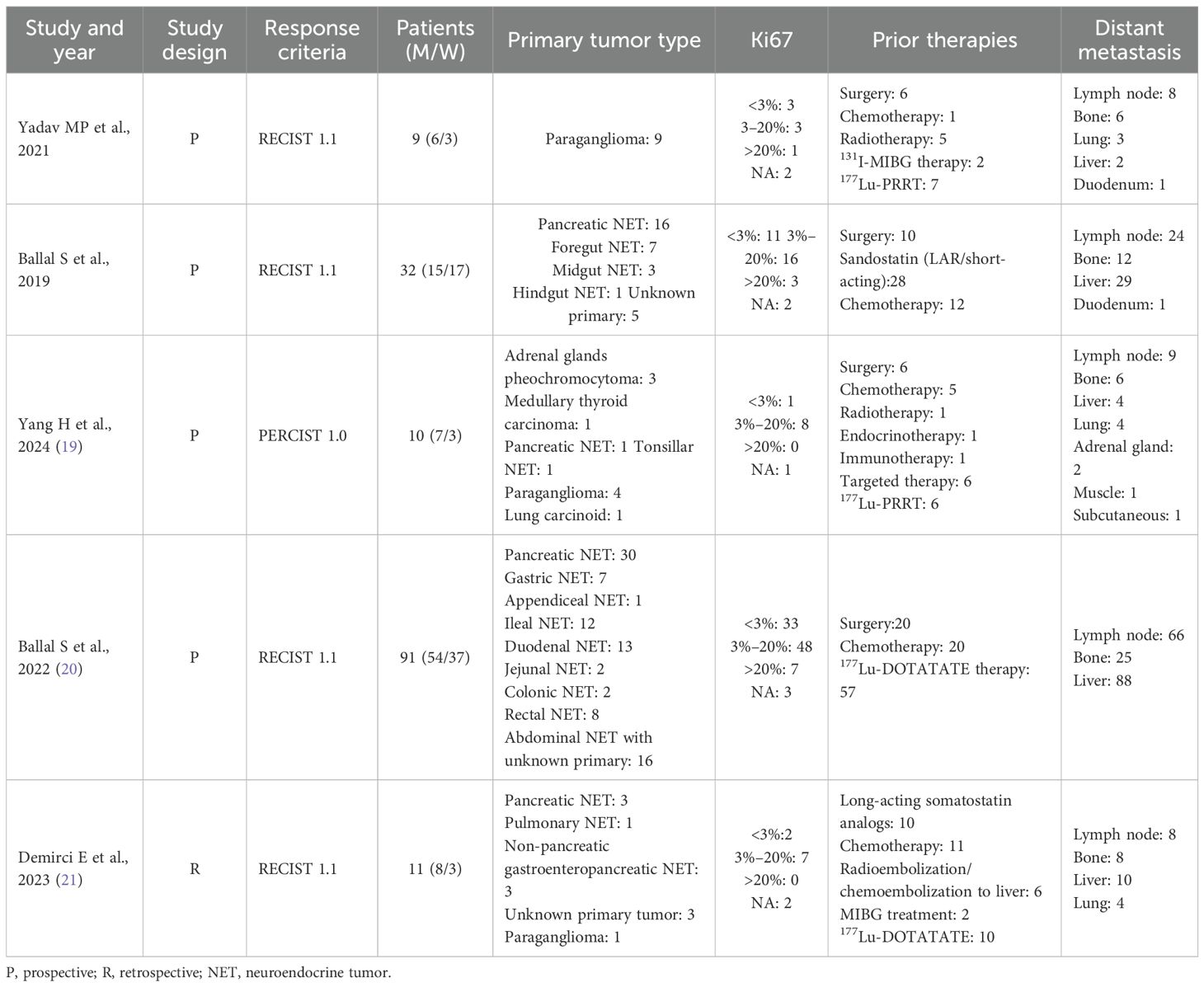

Study characteristics

A total of five studies consisting of 153 patients were included in the analysis.

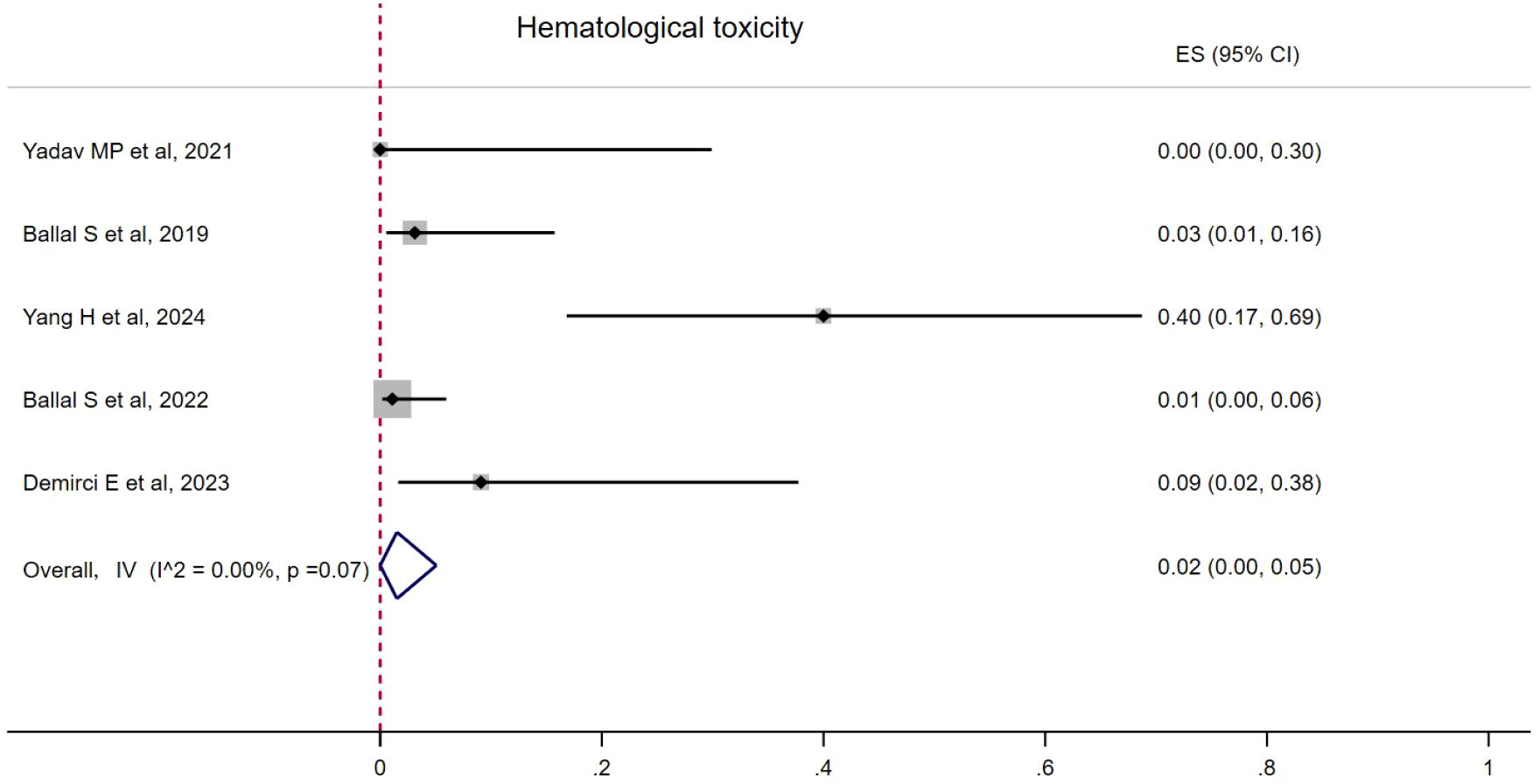

The total treatment cycles ranged from 1 to 9, and the follow-up time was from 5 to 41 months. Four studies have previously reported the use of 177Lu-PRRT in patients. RECIST 1.1 criteria were used to evaluate therapeutic efficacy in four studies (17, 18, 20, 21), and PERCIST 1.0 was used in one study (19). Toxicity was reported in four studies. In two studies (17, 20), capecitabine was used as a radiosensitizer, and amino acids were used to protect the kidneys in all studies, as shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Therapeutic efficacy

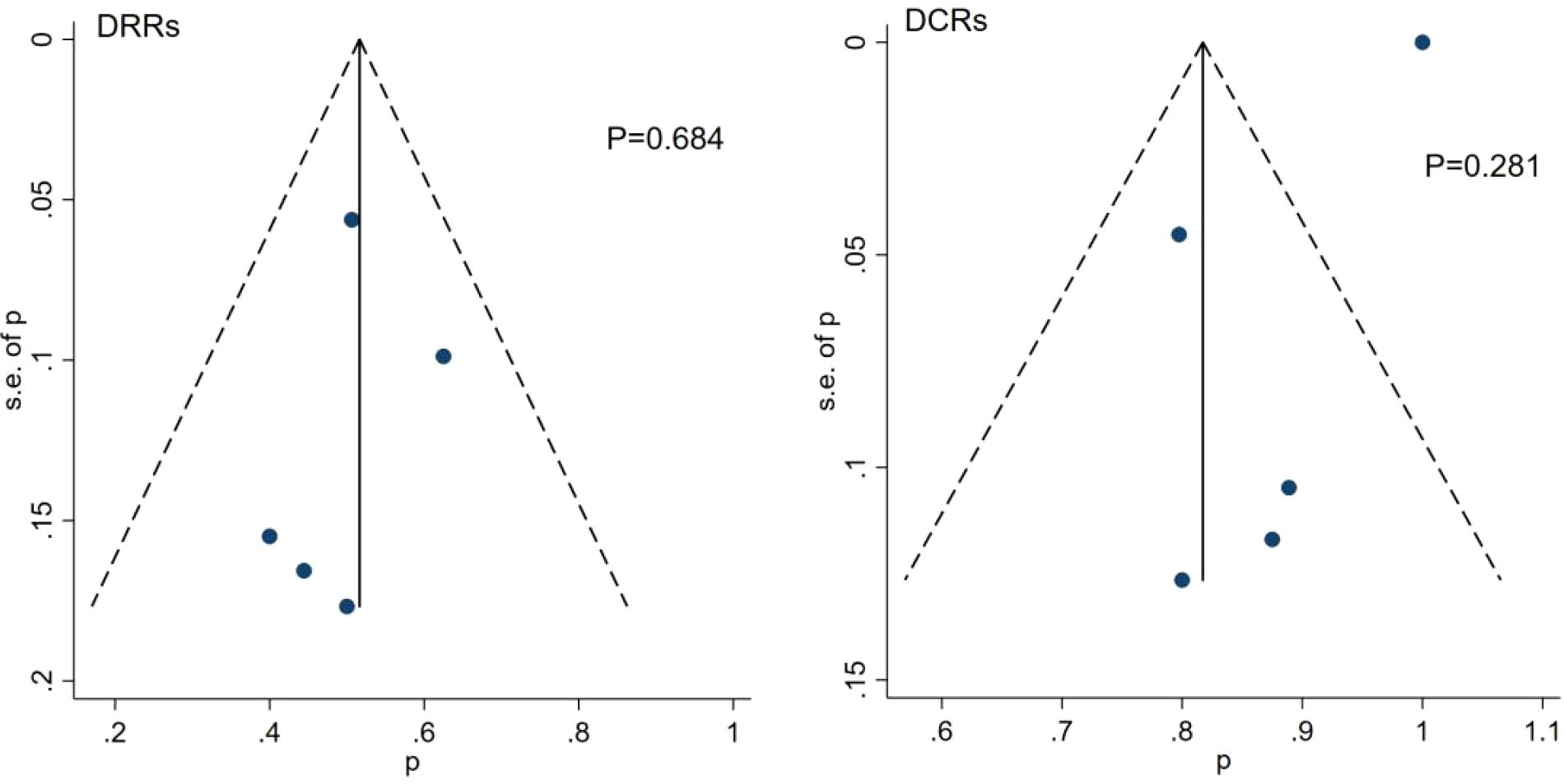

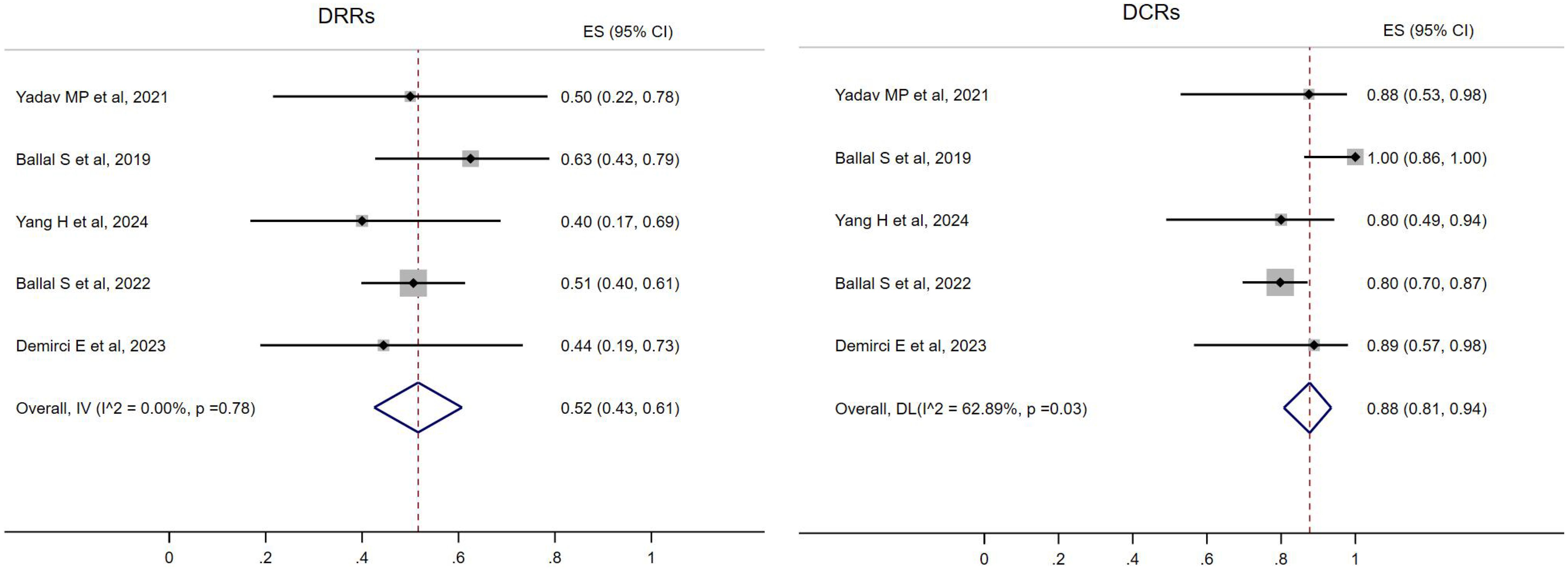

All five studies reported the treatment response of DRRs and DCRs. A fixed-effects model (I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.78) was used and the pooled proportion of DRRs was 0.52 (95% CI, 0.43–0.61). A random-effects model (I2 = 62.89%, p = 0.03) was used and the pooled proportion of DCRs was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.81–0.94), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Forest plot of the proportions of disease response rates (DRRs) and disease control rates (DCRs) for all.

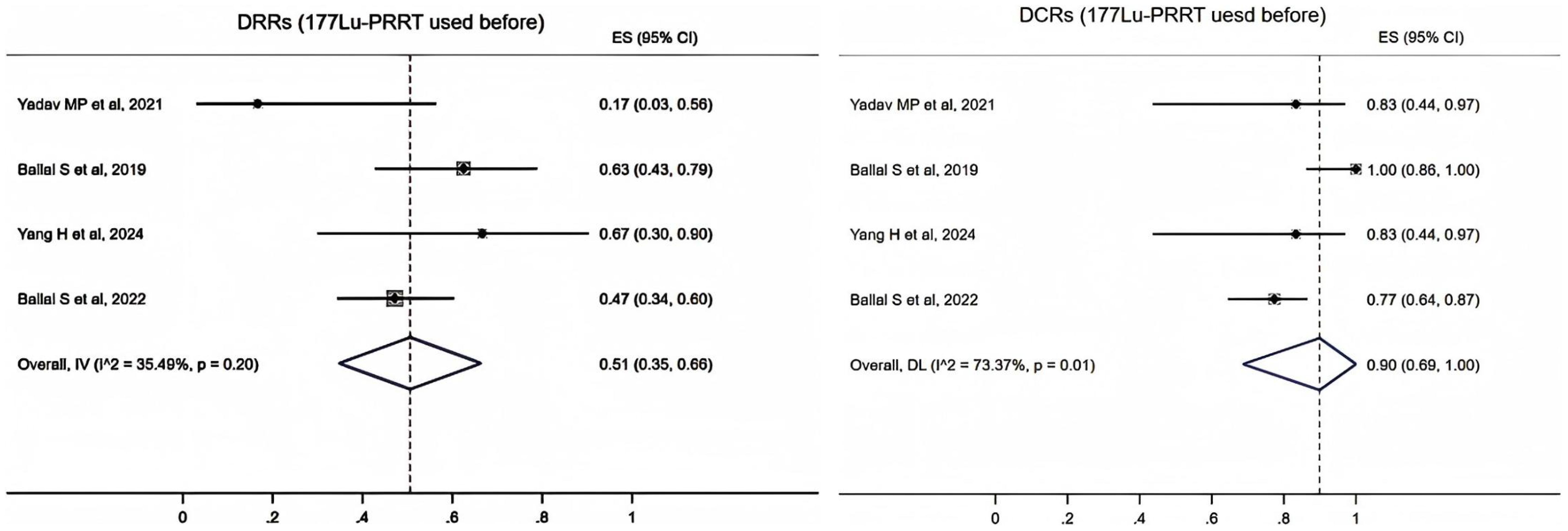

In four studies (17–20), 89 patients reported the use of 177Lu-PRRT before 225Ac-DOTATATE. A fixed-effects model (I2 = 35.49%, p = 0.2) was used and the pooled proportion of DRRs was 0.51 (95% CI, 0.35–0.66). A random-effects model (I2 = 73.37%, p = 0.01) was used and the pooled proportion of DCRs was 0.9 (95% CI, 0.69–1.00) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of the proportions of disease response rates (DRRs) and disease control rates (DCRs) for patients with 177Lu-PRRT.

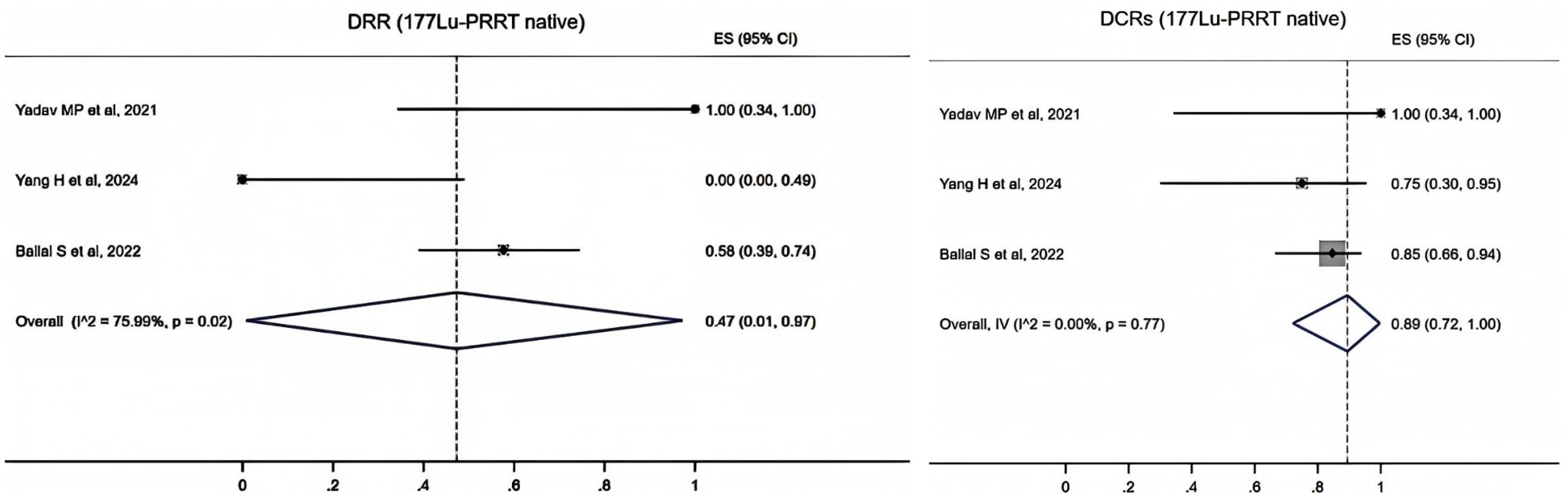

The data of 177Lu-PRRT native patients were extracted from three studies. It showed that the pooled proportion of DRRs was 0.47 (95% CI, 0.01–0.97) using a random-effects model (I2 = 75.99%, p = 0.02). The pooled proportion of DCRs was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.72–1.00) using a fixed-effects model (I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.77) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Forest plot of the proportions of disease response rates (DRRs) and disease control rates (DCRs) for patients with 177Lu-PRRT native.

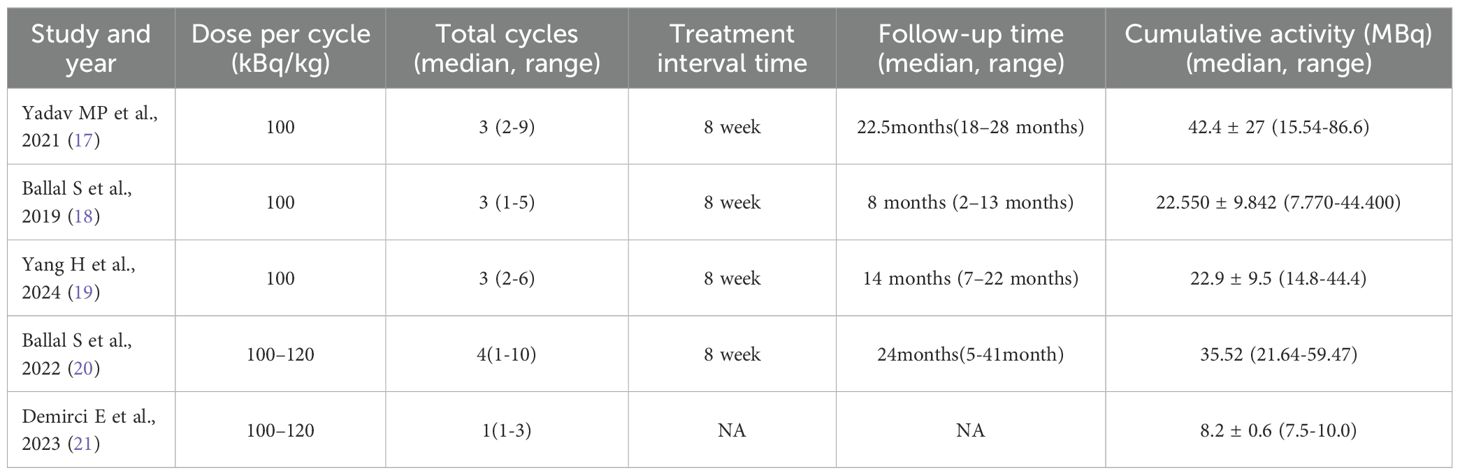

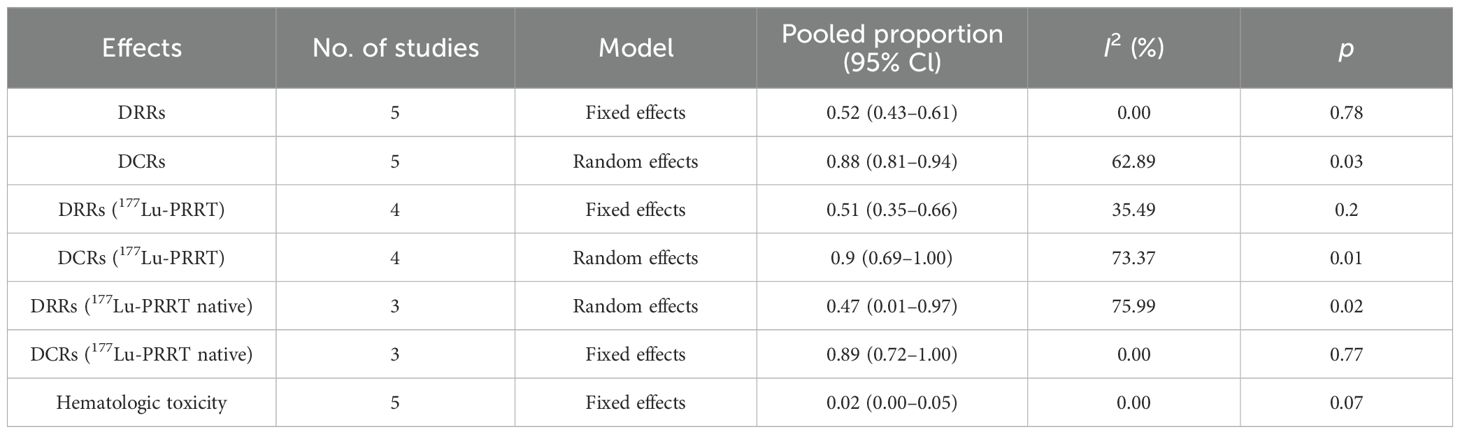

Toxicity

Hematological toxicity was seen in four studies, with seven patients (18–20). The pooled proportion of hematological toxicity was 0.02 (95% CI, 0.00–0.05) using a fixed-effects model (I2 = 0.00%, p = 0.07). Nephrotoxicity was seen in two patients and no hepatotoxicity was reported (Figure 5). Toxicity details are summarized in Table 4.

The pooled proportion therapeutic efficacy and toxicity results are summarized in Table 5.

Publication bias

Funnel plots and the Egger’s test were used to assess the publication bias of the studies. The results showed that there was no significant publication bias among these studies (Figure 6).

Discussion

225Ac-DOTATATE has demonstrated immense potential in TAT for NETs in clinical practice. Our study included five research articles on the treatment of NETs with 225Ac-DOTATATE, with a focus on analyzing the therapeutic efficacy and toxicity of 225Ac-DOTATATE in advanced metastatic NETs. The tumor types included paraganglioma (PGL), gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs), and adrenal gland pheochromocytoma, among others. Our meta-analysis showed that 52% of patients achieved DRRs, and 88% of patients exhibited DCRs following treatment with 225Ac-DOTATATE. In contrast, published meta-analyses on 177Lu-PRRT reported the DRRs ranging from approximately 20% to 35% (22, 23). Patients who had not previously undergone 177Lu-PRRT and directly received 225Ac treatment achieved a DRR of 47%, which is higher than 18% and 43% observed in the NETTER-1 trial and NETTER-2 trial for patients treated with 177Lu-DOTATATE (24, 25). Among the 89 patients who had previously undergone 177Lu-PRRT, they either opted for 225Ac due to disease progression after 177Lu treatment or discontinued 177Lu after reaching the maximum tolerated dose. The results showed that in these patients, the DRR was 51% and the DCR was 90% following 225Ac-DOTATATE therapy. 177Lu emits beta particles, which, despite their relatively wide range of action, have lower energy and may contribute to the development of resistance in tumor cells. Potential mechanisms for this resistance include the downregulation of receptor expression, enhanced DNA repair mechanisms in tumor cells, and changes in the tumor microenvironment (26). Because of their high LET (~100 keV/μm), alpha particles induce DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) that are typically difficult for tumor cells to repair. Additionally, they exhibit strong cytotoxic effects even against resistant tumor cells in a low proliferative state (11, 27). Therefore, for patients who have developed resistance or shown no response to targeted beta therapy, 225Ac-DOTATATE has demonstrated significant potential in overcoming resistance to 177Lu-PRRT (28). Furthermore, we observed that although the DRRs and DCRs were slightly higher in patients who had undergone prior 177Lu-PRRT compared to 177Lu-naive patients, the results should be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size of the included studies.

The incidence of hematological toxicity was 2%, with grade I–II hematological toxicity observed in six patients, and grade III thrombocytopenia occurring in one patient.

Only grade I or grade II nephrotoxicity was observed in two patients (18, 21). Grade III/IV hematological or renal toxicity was not reported during the follow-up period, nor was any degree of hepatic toxicity observed. Kavanal et al. (29) reported a case of subclinical hypothyroidism following 225Ac-DOTATATE treatment in a patient with metastatic NETs, but no similar findings were noted in this study.

Four studies (17–20) have reported transient symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea during the treatment process due to amino acid infusion. However, these symptoms were resolved after the treatment was completed.

The average cumulative activity ranged from 7.5 to 86.6 MBq, with the longest follow-up period reaching 41 months. During the follow-up, patients exhibited good tolerance, and Grade III or higher adverse events were uncommon, transient, or unlikely to be related to the treatment. Further research is still needed to accurately measure the absorbed doses in target and non-target organs and to evaluate the maximum tolerated dose associated with alpha therapy. Four studies (17–20) demonstrated significant improvements in patients’ physical function, emotional state, and social functioning following treatment. As a salvage therapy, 225Ac-DOTATATE has shown remarkable potential in improving the quality of life and clinical symptoms of patients with NETs.

This meta-analysis has certain limitations. The sample sizes of the included studies were relatively small, and there were differences in the demographic characteristics of the patients. Because of limited data, it was not possible to explore the long-term prognostic efficacy of 225Ac-DOTATATE, such as overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). This is a preliminary summary of 225Ac-DOTATATE in NETs. Owing to the limited number of participants included in the study, the conclusions drawn still lack robustness. Therefore, future high-quality, prospective, multicenter randomized controlled trials are needed to further clarify the optimal therapeutic dosage of 225Ac-DOTATATE and to explore combination treatment strategies in advanced metastatic NETs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

JM: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology. YJ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZY: Writing – review & editing. JY: Writing – review & editing. CZ: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Abbreviations

NETs, neuroendocrine tumors; TAT, targeted alpha therapy; LET, linear energy transfer; SSTR, somatostatin receptor; PRRT, peptide receptor radionuclide therapy; DRRs, disease response rates; DCRs, disease control rates; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; RECIST 1.1, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.1; PERCIST 1.0, PET Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors 1.0; CTCAE5.0, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events 5.0; PGL, paraganglioma; GEP-NETs, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors; DSBs, double-strand breaks; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

References

1. Huguet I, Grossman AB, and O’Toole D. Changes in the epidemiology of neuroendocrine tumours. Neuroendocrinology. (2015) 104:105–11. doi: 10.1159/000441897

2. Das S and Dasari A. Epidemiology, incidence, and prevalence of neuroendocrine neoplasms: are there global differences? Curr Oncol Rep. (2021) 23:43. doi: 10.1007/s11912-021-01029-7

3. Zandee WT and de Herder WW. The evolution of neuroendocrine tumor treatment reflected by ENETS guidelines. Neuroendocrinology. (2018) 106:357–65. doi: 10.1159/000486096

4. Caplin ME and Ratnayake GM. Diagnostic and therapeutic advances in neuroendocrine tumours. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2020) 17:81–2. doi: 10.1038/s41574-020-00458-x

5. Di Santo G, Santo G, Sviridenko A, and Virgolini I. Peptide receptor radionuclide therapy combinations for neuroendocrine tumours in ongoing clinical trials: status 2023. Theranostics. (2024) 14:940–53. doi: 10.7150/thno.91268

6. Rizen EN and Phan AT. Neuroendocrine tumors: a relevant clinical update. Curr Oncol Rep. (2022) 24:703–14. doi: 10.1007/s11912-022-01217-z

7. Sitani K, Parghane R, Talole S, and Basu S. The efficacy, toxicity and survival of salvage retreatment PRRT with177 Lu-DOTATATE in patients with progressive NET following initial course of PRRT. Br J Radiol. (2022) 95:20210896. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20210896

8. Strosberg J, Leeuwenkamp O, and Siddiqui M. Peptide receptor radiotherapy re-treatment in patients with progressive neuroendocrine tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. (2021) 93:102141. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102141

9. Singh S, Bergsland EK, Card CM, Hope TA, Kunz PL, Laidley DT, et al. Commonwealth neuroendocrine tumour research collaboration and the north american neuroendocrine tumor society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with lung neuroendocrine tumors: an international collaborative endorsement and update of the 2015 european neuroendocrine tumor society expert consensus guidelines. J Thorac Oncol. (2020) 15:1577–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.06.021

10. Navalkissoor S and Grossman A. Targeted alpha particle therapy for neuroendocrine tumours: the next generation of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Neuroendocr Tumours. (2018) 108:256–64. doi: 10.1159/000494760

11. Kunikowska J and Królicki L. Targeted α-emitter therapy of neuroendocrine tumors. Semin Nucl Med. (2020) 50:171–6. doi: 10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2019.11.003

12. Morgenstern A, Apostolidis C, Kratochwil C, Sathekge M, Krolicki L, Bruchertseifer F, et al. An overview of targeted alpha therapy with225 actinium and213 bismuth. Curr Radiopharm. (2018) 11:200–8. doi: 10.2174/1874471011666180502104524

13. Guerra Liberal FDC, O’Sullivan JM, McMahon SJ, and Prise KM. Targeted alpha therapy: current clinical applications. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. (2020) 35:404–17. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2020.3576

14. Targeted Alpha Therapy Working Group, Parker C, Lewington V, Shore N, Kratochwil C, Levy M, et al. Targeted alpha therapy, an emerging class of cancer agents: A review. JAMA Oncol. (2018) 4:1765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4044

15. Moher D, Liberati A, and Tetzlaff J. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PloS Med. (2009) 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

16. Munn Z, Barker TH, Moola S, Tufanaru C, Stern C, McArthur A, et al. Methodological quality of case series studies: an introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid Synth. (2020) 18:2127–33. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-D-19-00099

17. Yadav MP, Ballal S, Sahoo RK, and Bal C. Efficacy and safety of 225Ac-DOTATATE targeted alpha therapy in metastatic paragangliomas: a pilot study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2021) 49:1595–606. doi: 10.1007/s00259-021-05632-5

18. Ballal S, Yadav MP, Bal C, Sahoo RK, and Tripathi M. Broadening horizons with 225Ac-DOTATATE targeted alpha therapy for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumour patients stable or refractory to 177Lu-DOTATATE PRRT: first clinical experience on the efficacy and safety. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2019) 47:934–46. doi: 10.1007/s00259-019-04567-2

19. Yang H, Zhang Y, Li H, Zhang Y, Feng Y, Yang X, et al. Efficacy and safety of 225 ac-DOTATATE in the treatment of neuroendocrine neoplasms with high SSTR expression. Clin Nucl Med. (2024) 49:505–12. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000005149

20. Ballal S, Yadav MP, Tripathi M, Sahoo RK, and Bal C. Survival outcomes in metastatic gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor patients receiving concomitant 225Ac-DOTATATE targeted alpha therapy and capecitabine: A real-world scenario management based long-term outcome study. J Nucl Med. (2022), jnumed.122.264043. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.122.264043

21. Demirci E, Alan Selçuk N, Beydağı G, Ocak M, Toklu T, Akçay K, et al. Initial findings on the use of [225Ac]Ac-DOTATATE therapy as a theranostic application in patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Mol Imaging Radionucl Ther. (2023) 32:226–32. doi: 10.4274/mirt.galenos.2023.38258

22. Wang LF, Lin L, Wang MJ, and Li Y. The therapeutic efficacy of 177Lu-DOTATATE/DOTATOC in advanced neuroendocrine tumors: A meta-analysis. Med (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e19304. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000019304

23. Zhang J, Song Q, Cai L, Xie Y, and Chen Y. The efficacy of 177Lu-DOTATATE peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2020) 146:1533–43. doi: 10.1007/s00432-020-03181-2

24. Strosberg J, El-Haddad G, Wolin E, Hendifar A, Yao J, Chasen B, et al. NETTER-1 trial investigators. Phase 3 trial of 177Lu-dotatate for midgut neuroendocrine tumors. N Engl J Med. (2017) 376:125–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1607427

25. Singh S, Halperin D, Myrehaug S, Herrmann K, Pavel M, Kunz PL, et al. 177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TATE plus long-acting octreotide versus high dose long-acting octreotide for the treatment of newly diagnosed, advanced grade 2-3, well-differentiated, gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (NETTER-2): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet. (2024) 403(10446):2807–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00701-3

26. Bodei L, Kidd M, Paganelli G, Grana CM, Drozdov I, Cremonesi M, et al. Long-term tolerability of PRRT in 807 patients with neuroendocrine tumours: the value and limitations of clinical factors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. (2015) 42:5–19. doi: 10.1007/s00259-014-2893-5

27. Bhimaniya S, Shah H, and Jacene HA. Alpha-emitter peptide receptor radionuclide therapy in neuroendocrine tumors. PET Clin. (2024) 19:341–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cpet.2024.03.005

28. Feuerecker B, Kratochwil C, Ahmadzadehfar H, Morgenstern A, Eiber M, Herrmann K, et al. Clinical translation of targeted α-therapy: an evolution or a revolution? J Nucl Med. (2023) 64:685–92. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.122.265353

Keywords: neuroendocrine tumors, 225Ac-DOTATATE, efficacy, meta-analysis, radionuclide therapy

Citation: Ma J, Ji Y, Yao Z, Yangqing J and Zhang C (2025) The therapeutic efficacy of 225Ac-DOTATATE in neuroendocrine tumors: a preliminary meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 15:1696063. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1696063

Received: 31 August 2025; Accepted: 13 October 2025;

Published: 31 October 2025.

Edited by:

Sangeeta Ray Banerjee, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesReviewed by:

Pablo Minguez Gabina, Cruces University Hospital, SpainMercedes Mitjavila, Puerta de Hierro University Hospital Majadahonda, Spain

Copyright © 2025 Ma, Ji, Yao, Yangqing and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Chunyin Zhang, emhhbmdjaHVueWluMzQ1QHNpbmEuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Jiao Ma1,2,3†

Jiao Ma1,2,3† Yang Ji

Yang Ji Chunyin Zhang

Chunyin Zhang