- 1Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine (DIM), University of “Aldo Moro”, Polyclinic of Bari, Bari, Italy

- 2Unit of Oncologic Gynecology, IRCCS “Giovanni Paolo II” Oncologic Institute, Bari, Italy

Introduction: Cancer during pregnancy is a rare event and often presents at an advanced stage due to delayed diagnosis. Clinical symptoms are frequently misattributed to normal pregnancy changes, leading to diagnostic challenges. Moreover, concerns regarding fetal safety limit the use of certain imaging modalities and treatment options. Managing cancer in pregnancy requires careful coordination across specialties to balance maternal treatment with fetal preservation.

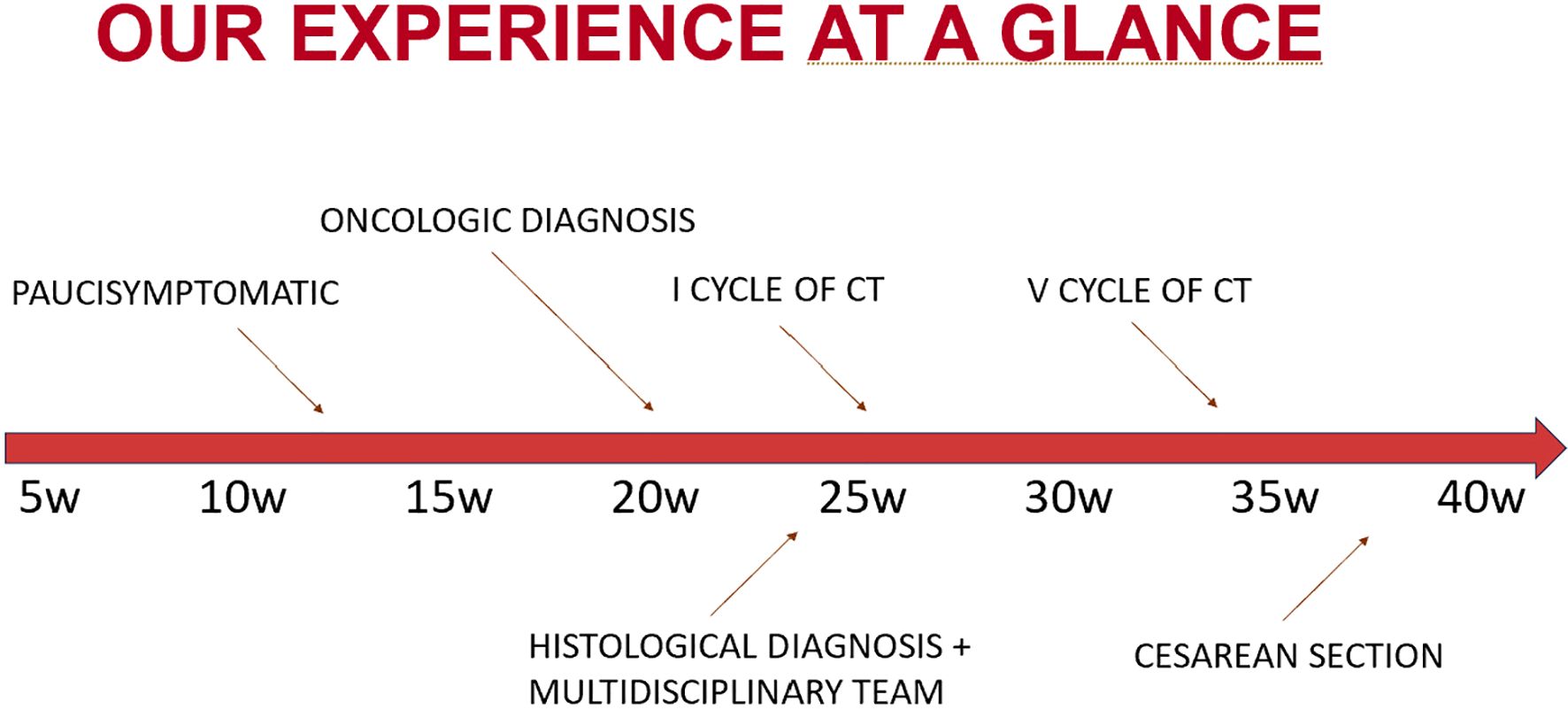

Case-report: We present the case of a pregnant woman diagnosed in the second trimester with advanced metastatic colorectal cancer. The disease involved multiple intra-abdominal sites, and the patient was managed through a multidisciplinary approach. Chemotherapy with FOLFOX scheme was administered during the second and third trimester of pregnancy, leading to a favorable clinical and radiologic response. Delivery was planned at term, with no complications for the newborn. Postpartum oncologic management was continued without delay.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of individualized care in such complex scenarios and the feasibility and safety of administering chemotherapy during pregnancy.

Introduction

Pregnancy-associated cancer (PAC), defined as cancer diagnosed during pregnancy or within one year postpartum, presents a rare but complex clinical scenario with significant implications for both maternal and fetal health. (1) The coexistence of pregnancy and malignancy introduces unique challenges in diagnosis, management, and ethical decision-making. (2) Due to the rarity of PAC and the exclusion of pregnant patients from most clinical trials, evidence-based treatment guidelines are limited, and therapeutic strategies are often based on expert opinion, case reports, and retrospective studies. (3, 4).

It is estimated that approximately 1 in every 1,000 to 2,000 pregnancies is complicated by a cancer diagnosis. (5) The most commonly encountered malignancies during pregnancy are breast cancer, melanoma, and cervical cancer, which collectively account for the majority of PAC cases. In contrast, colorectal cancer (CRC) in pregnancy is exceedingly rare, constituting only 1–3% of all pregnancy-related cancers. (6).

Diagnosing CRC during pregnancy can be particularly challenging, as symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal discomfort may be misattributed to normal gestational changes, often resulting in delayed diagnosis and more advanced disease at presentation. (7, 8) Furthermore, management options must be carefully balanced to optimize maternal outcomes while minimizing fetal risks. (9, 10) Chemotherapy is contraindicated during the first trimester due to teratogenicity but may be considered in the second and third trimesters. (11, 12) Surgical interventions, when indicated, are generally safe throughout pregnancy, whereas radiotherapy is typically deferred until after delivery due to substantial fetal risk. (13).

With the increasing trend of early-onset CRC and the rise in maternal age, the incidence of CRC diagnosed during pregnancy is expected to grow. (14) In this context, we report a rare and instructive case of a pregnant woman diagnosed with CRC, highlighting the diagnostic challenges, multidisciplinary decision-making, and therapeutic approach tailored to both maternal and fetal considerations.

Case report

A 37-year-old Albanian pregnant patient, with no prior medical or surgical history and a negative family history for oncological disease, was referred for an abdominal MRI due to persistent abdominal pain unresponsive to medication for over a month. Symptoms were initially self-managed with over-the-counter analgesics, as she believed they were pregnancy-related. However, due to worsening discomfort and increasing abdominal girth, she sought medical evaluation. At that time, she was 21 weeks pregnant with her second child (the first pregnancy uneventful). She reported that routine prenatal examinations performed in Albania were described to her as normal, although only limited documentation was available for review.

While residing in her home country, the patient underwent an abdominal MRI, which revealed an enlarged liver (right lobe measuring approximately 23 cm), with multiple focal lesions in both hepatic lobes, suggestive of metastases, ranging in size from 1 to approximately 10 cm. There were also multiple peritoneal and omental thickenings. Ascites filled all peritoneal recesses. No lymphadenopathy was identified. Bilateral adnexal masses were also observed and initially interpreted as possible primary ovarian malignancies.

The patient elected to continue diagnostic evaluation and treatment in Italy and was referred to our unit at approximately 24 weeks of gestation. An abdominal ultrasound confirmed diffuse ascites, peritoneal thickenings forming an omental cake-like appearance, a solid pelvic mass on the left side of uncertain origin, possible intestinal or ovarian relevance, measuring up to 12 cm in maximal diameter, poorly vascularized, and another pelvic lesion on the right side, likely originating from the right adnexa. Multiple hepatic lesions were also noted, consistent with metastatic disease. Gynecologic evaluation raised suspicion of a gastrointestinal primary tumor with widespread metastases. The original MRI from Albania was reviewed by a local radiologist, who confirmed the suspicion of a bowel-origin neoplasm.

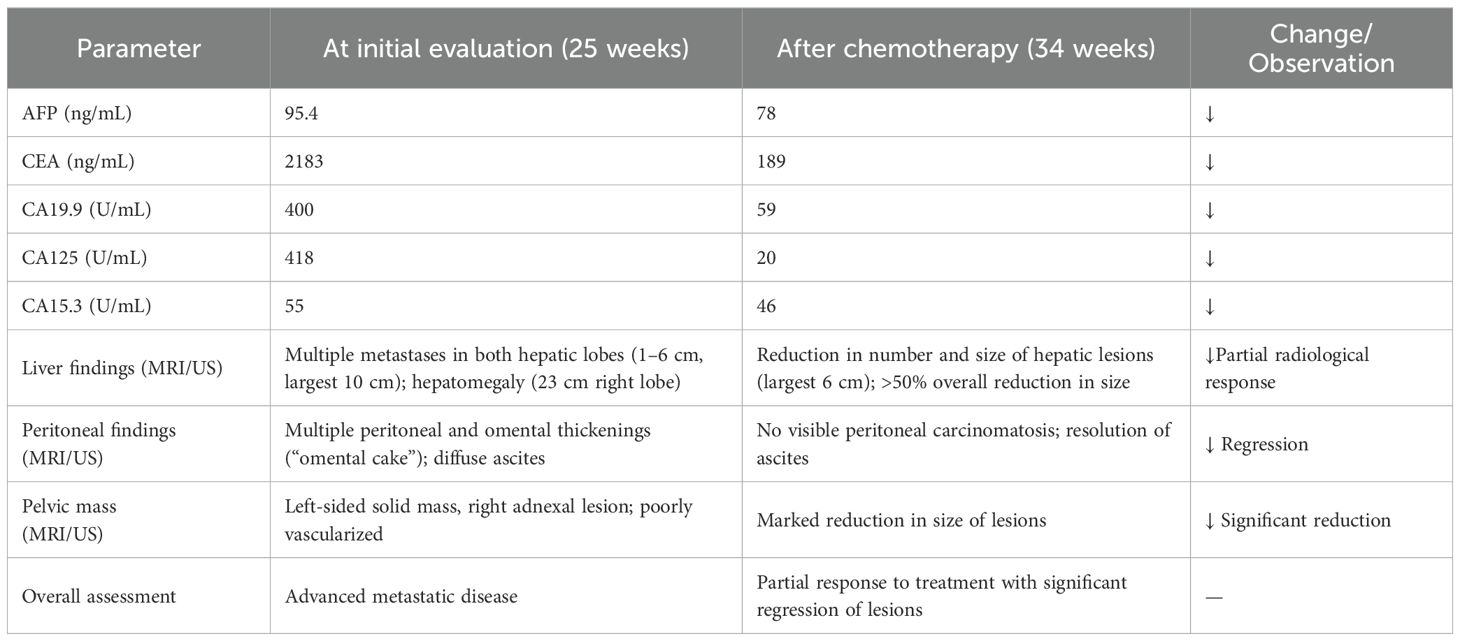

Upon admission to our center in Italy, the patient presented in poor general conditions, with severe anemia (hemoglobin level was 7.5 g/dL), dispnea, and abdominal pain due to large volume of ascites. She underwent evacuative paracentesis and received two blood transfusions, along with corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation. Electrocardiogram showed sinus rhythm. Laboratory investigations showed elevated tumor markers (AFP 95.4 ng/mL, CEA 2183 ng/mL, CA15.3–55 U/mL, CA125–418 U/mL, and CA19.9–400 U/mL), while platelet count, white cell count, electrolytes, liver and renal function tests, and coagulation profile were within normal limits. Obstetric ultrasound revealed no signs of fetal distress and the estimated fetal weight (EFW) at first assessment was at the 30th percentile (Hadlock charts). A liver biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of gastrointestinal malignancy.

During hospitalization, the patient underwent rectosigmoidoscopy, which revealed an infiltrative lesion at the rectosigmoid junction. Histological examination of biopsy specimens confirmed the diagnosis of metastatic adenocarcinoma of intestinal origin, moderately differentiated (G2), with immunohistochemistry positive for CDX2 and CK20, and negative for CK7 and PAX8.

The case was discussed at a multidisciplinary tumor board involving obstetricians, neonatologists, oncologists, and psychologists. It was decided to initiate chemotherapy during pregnancy, starting at 26 weeks of gestation. The patient received a total of five biweekly cycles of FOLFOX (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m² + 5-FU bolus 400 mg/m²) from week 26 to week 34. The patient tolerated chemotherapy well, with no treatment-related adverse events such as neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, or gastrointestinal toxicity. Supportive therapy consisted of ondansetron for nausea, and no additional supportive measures were required. Serial ultrasound assessments demonstrated preserved fetal Doppler studies and biophysical parameters, although a progressive growth restriction emerged, with the estimated fetal weight decreasing to the 5th percentile at 37 weeks.

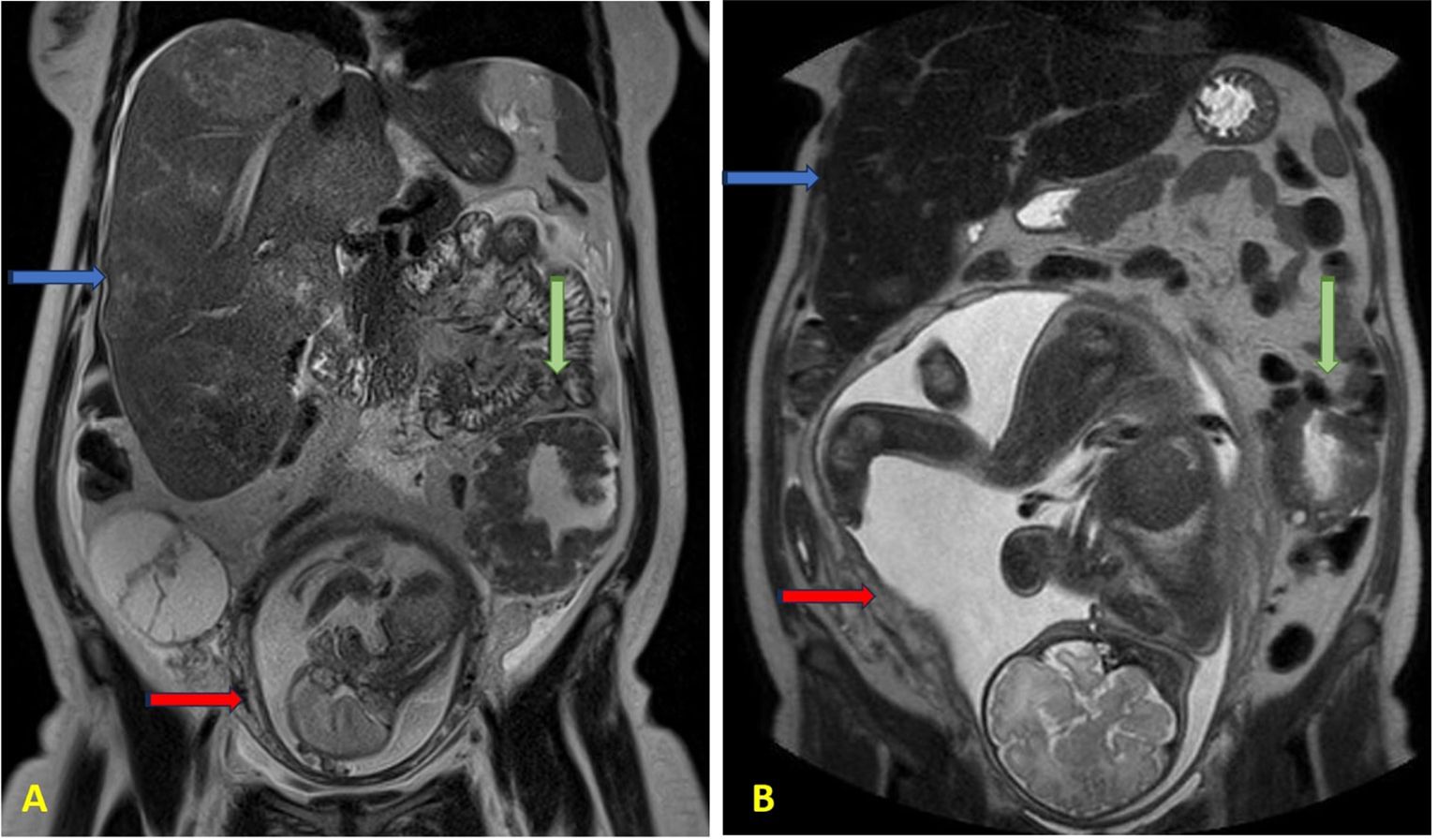

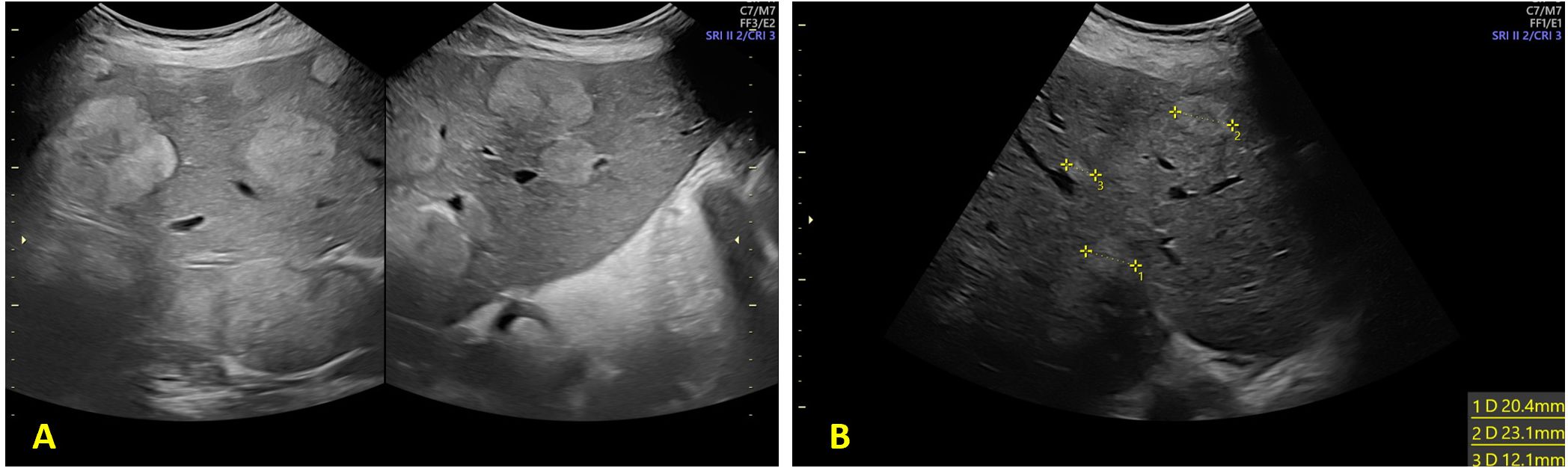

Following completion of five chemotherapy cycles, the tumor marker levels showed marked reduction: AFP 78 ng/mL, CEA 189 ng/mL, CA15.3–46 U/mL, CA125–20 U/mL, and CA19.9–59 U/mL. Radiological re-evaluation thruough MRI documented a significant reduction in the number and size of hepatic metastases. Peritoneal carcinomatosis was no longer visible and ascites had resolved (Figure 1) On ultrasound evaluation the largest hepatic lesion decreased from 10 cm to 6 cm, and all previously identified liver nodules showed a reduction in size of at least 50%. (Figure 2) The pelvic masses had also substantially decreased in size. (Table 1).

Figure 1. Abdomen MRI at (A) 21 weeks of gestation and (B) 37 weeks of gestation. The blue arrows indicate enlarged liver containing multiple metastatic lesions; the green arrows indicate the left pelvic mass; the red arrows indicate the fetus in the uterus.

Figure 2. Ultrasound evaluation of hepatic metastasis (A) 28 weeks of gestation and (B) at 33 weeks of gestation.

Table 1. Table summarizing tumor markers and imaging findings at initial evaluation (25 weeks) vs post-chemotherapy (34 weeks).

A second multidisciplinary discussion was held to determine the timing and mode of delivery. It was agreed to deliver the fetus via elective caesarean section (CS) at 37 weeks of gestation - ensuring a three-week interval from the last chemotherapy cycle - with concurrent bilateral adnexectomy.

The CS was performed at 37 weeks and 4 days, delivering a female infant weighing 2355 g. Neonatal condition was good: arterial pH was 7.28, base excess (B) -1.2 mmol/L, extracellular base excess (BEecf) 0.1 mmol/L, and Apgar scores were 9 and 10 at 1 and 5 minutes, respectively. The newborn showed no signs of distress during hospitalization. After thorough counseling with the neonatology team regarding the risks and benefits of breastfeeding in her oncologic context, the patient opted to suppress lactation.

Bilateral adnexectomy was performed during the procedure. Histopathology confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma involvement in both ovaries (CDX2+, CK20+, CK7–, PAX8–, WT1–; HER2 score 0; microsatellite stability detected). Examination of the placenta, membranes, and umbilical cord revealed no tumor infiltration. Both fallopian tubes were free of malignancy. The postoperative course was uneventful, the patient underwent radiologic reassessment and continued first-line chemotherapy as per oncologic plan (Figure 3).

Discussion

Colorectal cancer during pregnancy remains a rare and challenging diagnosis, particularly due to symptom overlap with physiological changes of pregnancy, and concerns over fetal exposure during imaging and treatment. In our case, early symptoms were underestimated by the patient causing a delay in medical evaluation. Once referred to our unit, however, diagnostic work-up and treatment were initiated without delay, as our center has established experience in managing cancer during pregnancy.

In the differential diagnosis of a pelvic mass on ultrasound, it is important to consider the possibility of a pelvic abscess or infectious complication in pregnant women - particularly in presence of systemic symptoms such as fever, pelvic pain, asthenia, and vomiting. (15, 16) Pelvic abscesses typically present with more irregular margins, internal content consisting of dense fluid collections with debris, thin septations or fluid-fluid levels, and tend to show low and peripheral vascularization on Doppler imaging. Additionally, compression with the ultrasound probe often elicits significant tenderness. Laboratory findings may further support the diagnosis, with elevated inflammatory markers and negative tumor markers.

Our case reflects current literature trends showing an increasing incidence of early-onset CRC, often presenting as symptomatic, left-sided, and advanced disease. (14) Similar to other reported cases, timely multidisciplinary management—including chemotherapy during the second and third trimesters—was essential in balancing maternal treatment needs with fetal safety. In our patient’s case, chemotherapy administered during pregnancy, led to disease stabilization and a favorable neonatal outcome, aligning with evidence that such regimens can be used safely in pregnancy with appropriate monitoring. (17, 18).

Regarding timing of delivery, the patient’s compromised clinical condition at presentation did not allow us to confidently rule out the possibility of urgent preterm birth; therefore, antenatal corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation were administered. As her condition stabilized, we prioritized continuation of therapy and prolonged gestation, ultimately achieving a term delivery. This case reinforces that, whenever clinically feasible, term birth offers the best neonatal outcomes and should remain the primary goal.

Although the neonatal outcome was reassuring and the newborn did not require intensive care, we acknowledge that our follow-up is currently limited to the short term. Reports have described the presence of platinum–DNA adducts in children exposed in utero to DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, or oxaliplatin, raising the possibility of long-term effects that remain insufficiently understood. (19, 20) Continued pediatric surveillance will therefore be essential to assess potential late consequences of fetal chemotherapy exposure.

Overall, this case further supports the role of a tailored, team-based approach in managing cancer during pregnancy. It highlights the feasibility of administering chemotherapy after the first trimester, achieving disease control while allowing for fetal maturation and delivery at term.

Conclusions

This case highlights the complexity of diagnosing and managing colorectal cancer during pregnancy, particularly in advanced stages. Despite the challenges, timely multidisciplinary coordination allowed for effective maternal treatment with chemotherapy during the second and third trimesters, leading to significant tumor response and the delivery of a healthy newborn at term. This experience reinforces the feasibility and safety of chemotherapy in selected pregnant patients and underscores the importance of individualized care to optimize both maternal and fetal outcomes.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the study was a summary of data and outcomes of routine management (without direct intervention) and not an experimental protocol. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

AG: Data curation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. MC: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. GS: Data curation, Writing – original draft. PM: Writing – original draft, Data curation. TD: Data curation, Writing – original draft. GC: Visualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. MM: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. RA: Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. EC: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Validation. AV: Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Pavlidis NA. Coexistence of pregnancy and Malignancy. Oncologist. (2002) 7:279–87. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2002-0279

2. Murgia F, Marinaccio M, Cormio G, Loizzi V, Cicinelli R, Bettocchi S, et al. Pregnancy related cancer in Apulia. A population based linkage study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X. (2019) 3:100025. doi: 10.1016/j.eurox.2019.100025

3. Galante A, Cerbone M, Mannavola F, Marinaccio M, Schonauer LM, Dellino M, et al. Diagnostic, management, and neonatal outcomes of colorectal cancer during pregnancy: two case reports, systematic review of literature and metanalysis. Diagnostics (Basel). (2024) 14:559. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14050559

4. Scholz F, Starrach T, Holch J, Heinemann V, Wirth U, Werner J, et al. Management of metastatic colorectal cancer in pregnancy: A systematic review of a multidisciplinary challenge. Visc Med. (2025), 1–11. doi: 10.1159/000545464

5. Amant F, Berveiller P, Boere IA, Cardonick E, Fruscio R, Fumagalli M, et al. Gynecologic cancers in pregnancy: guidelines based on a third international consensus meeting. Ann Oncol. (2019) 30:1601–12. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz228

6. Peccatori FA, Azim HA, Orecchia R, Hoekstra HJ, Pavlidis N, Kesic V, et al. Cancer, pregnancy and fertility: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2013) 24 Suppl 6:vi160–170. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt199

7. Cao S, Okekpe CC, Dombrovsky I, Valenzuela GJ, and Roloff K. Colorectal cancer diagnosed during pregnancy with delayed treatment. Cureus. (2020) 12:e8261. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8261

8. Sorouri K, Loren AW, Amant F, and Partridge AH. Patient-centered care in the management of cancer during pregnancy. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. (2023) 43:e100037. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_100037

9. Alkhamis WH, Naama T, Arafah MA, and Abdulghani SH. Good outcome of early-stage rectal cancer diagnosed during pregnancy. Am J Case Rep. (2020) 21:e925673. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.925673

10. Parpinel G, Laudani ME, Giunta FP, Germano C, Zola P, and Masturzo B. Use of positron emission tomography for pregnancy-associated cancer assessment: A review. J Clin Med. (2022) 11:3820. doi: 10.3390/jcm11133820

11. Cardonick E, Usmani A, and Ghaffar S. Perinatal outcomes of a pregnancy complicated by cancer, including neonatal follow-up after in utero exposure to chemotherapy: results of an international registry. Am J Clin Oncol. (2010) 33:221–8. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181a44ca9

12. Rogers JE, Dasari A, and Eng C. The treatment of colorectal cancer during pregnancy: cytotoxic chemotherapy and targeted therapy challenges. Oncologist. (2016) 21:563–70. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0362

13. Walsh C and Fazio VW. Cancer of the colon, rectum, and anus during pregnancy. The surgeon’s perspective. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. (1998) 27:257–67. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70356-3

14. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

15. Nigro G, Adler SP, and Congenital Cytomegalic Disease Collaborating Group. High-dose cytomegalovirus (CMV) hyperimmune globulin and maternal CMV DNAemia independently predict infant outcome in pregnant women with a primary CMV infection. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) 71:1491–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz1030

16. Vimercati A, De Nola R, Trerotoli P, Metta ME, Cazzato G, Resta L, et al. COVID-19 infection in pregnancy: obstetrical risk factors and neonatal outcomes-A monocentric, single-cohort study. Vaccines (Basel). (2022) 10:166. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10020166

17. Amant F, Van Calsteren K, Halaska MJ, Gziri MM, Hui W, Lagae L, et al. Long-term cognitive and cardiac outcomes after prenatal exposure to chemotherapy in children aged 18 months or older: an observational study. Lancet Oncol. (2012) 13:256–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70363-1

18. Maggen C, Wolters VERA, Van Calsteren K, Cardonick E, Laenen A, Heimovaara JH, et al. Impact of chemotherapy during pregnancy on fetal growth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2022) 35:10314–23. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2022.2128645

19. Henderson CE, Elia G, Garfinkel D, Poirier MC, Shamkhani H, and Runowicz CD. Platinum chemotherapy during pregnancy for serous cystadenocarcinoma of the ovary. Gynecologic Oncol. (1993) 49:92–4. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1993.1092

Keywords: cancer, pregnancy, pregnancy associated cancer, colorectal cancer, chemotherapy, chemotherapy in pregnancy

Citation: Galante A, Cerbone M, Sorgente G, Moramarco P, Difonzo T, Cormio G, Marinaccio M, Alfonso R, Cicinelli E and Vimercati A (2025) Case Report: Advanced colorectal cancer diagnosed and treated with chemotherapy during pregnancy. Front. Oncol. 15:1699233. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1699233

Received: 04 September 2025; Accepted: 19 November 2025; Revised: 02 November 2025;

Published: 02 December 2025.

Edited by:

Tullio Golia D’Augè, Sapienza University of Rome, ItalyReviewed by:

Estelle Heggarty, CHI Poissy-Saint-Germain-en-Laye Site Hospitalier de Poissy, FranceOlivier Mir, Amgen SAS, France

Copyright © 2025 Galante, Cerbone, Sorgente, Moramarco, Difonzo, Cormio, Marinaccio, Alfonso, Cicinelli and Vimercati. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Arianna Galante, YXJpYW5uYWdhbGFudGU5NEBnbWFpbC5jb20=; YS5nYWxhbnRlMTJAc3R1ZGVudGkudW5pYmEuaXQ=

Arianna Galante

Arianna Galante Marco Cerbone1

Marco Cerbone1 Gennaro Cormio

Gennaro Cormio Ettore Cicinelli

Ettore Cicinelli Antonella Vimercati

Antonella Vimercati