- Department of Radiology, The Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Xinjiang Medical University, Urumqi, China

Tumor heterogeneity is a core challenge in gynecologic oncology, driving therapeutic resistance and limiting the efficacy of single-point biopsies. Artificial intelligence (AI) and radiomics are emerging as a “digital biopsy” to non-invasively decode tumor biology from medical radiological modalities images(including MRI, CT, and PET). This review synthesizes the state of AI in predicting key molecular features across gynecologic cancers, including homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) in ovarian cancer, microsatellite instability (MSI) and PI3K activation in endometrial cancer, and, as an illustrative case, HPV integration and DNA methylation in cervical cancer. We further explore how advanced architectures like Vision Transformers (ViTs) and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) can delineate the tumor microenvironment and predict therapeutic response. Finally, we discuss critical hurdles to clinical translation—such as model generalizability, the need for causal AI, and the data bottleneck—while examining future paradigms like foundation models and patient-specific “digital twins.” This review highlights AI’s revolutionary potential to link imaging phenotype with molecular genotype, advancing a new era of precision medicine in gynecologic oncology.

1 Introduction

One of the central challenges in clinical oncology stems from the fundamental nature of cancer: evolution (1, 2). A tumor is not a homogenous mass of cells but a complex, dynamically evolving ecosystem populated by subclones with diverse genotypes and phenotypes (3, 4). This profound intratumor heterogeneity (ITH) is a significant contributing factor to therapeutic resistance, disease relapse, and metastasis (5–7). Consider a clinical scenario: a 58-year-old woman with endometrial cancer whose single-site biopsy reveals a G2 endometrioid adenocarcinoma, p53 wild-type (8). This sample, however, may represent only a fraction of the tumor landscape, missing a distant, more aggressive p53-mutant subclone, thereby leading to suboptimal treatment decisions and a poor outcome (8–10). This scenario precisely exposes the fundamental limitation of the current “gold standard” reliance on single-point, invasive biopsies: inherent spatial sampling bias (8, 10). A particularly striking example is cervical cancer, where the HPV genome integrates into the host chromosome.—a key event in malignant progression—can be highly heterogeneous across the tumor, making it difficult to assess comprehensively with a small tissue sample (10).

Gynecologic cancers, primarily ovarian, endometrial, and cervical cancers, are a major threat to women’s health globally (11, 12). Thanks to large-scale sequencing initiatives like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), our understanding of their molecular landscapes has expanded exponentially (10, 13, 14). These studies have directly linked specific molecular features to clinical decisions. For instance, in high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) status is a critical biomarker for Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors (PARPi) therapy (12, 15, 16). In endometrial cancer, a molecular classification system profoundly changes prognostic stratification and treatment strategies (17–19). Notably, mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), or its surrogate high microsatellite instability (MSI-H), is a “pan-cancer” biomarker for immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (20–22). However, obtaining this molecular information remains a challenge. Tissue biopsies see the “trees” but miss the “forest,” while liquid biopsies lack spatial information (23, 24). This dilemma has created a critical unmet need for tools that can non-invasively characterize the entire tumor.

It is against this backdrop that the convergence of radiomics and artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged (25, 26). The core scientific hypothesis is that a tumor’s molecular genotype drives microscopic biological changes that manifest on macroscopic medical images as unique, quantifiable imaging phenotypes (25, 27, 28). This “digital biopsy” approach aims to decode the tumor’s biology directly from voxels, bridging the gap between genotype and phenotype. This concept forms the basis of the field of radiomics, which aims to bridge medical imaging and personalized medicine (26). We will explore how AI decodes key molecular markers, with a special focus on using cervical cancer to illustrate how AI can predict specific molecular events like HPV integration and DNA methylation, thereby showcasing the full potential of the digital biopsy paradigm (29, 30). The subsequent sections will delve into specific molecular markers, including the aforementioned HPV-driven events and DNA methylation patterns, to build a robust case for this transformative (31).

1.1 Search strategy and selection criteria

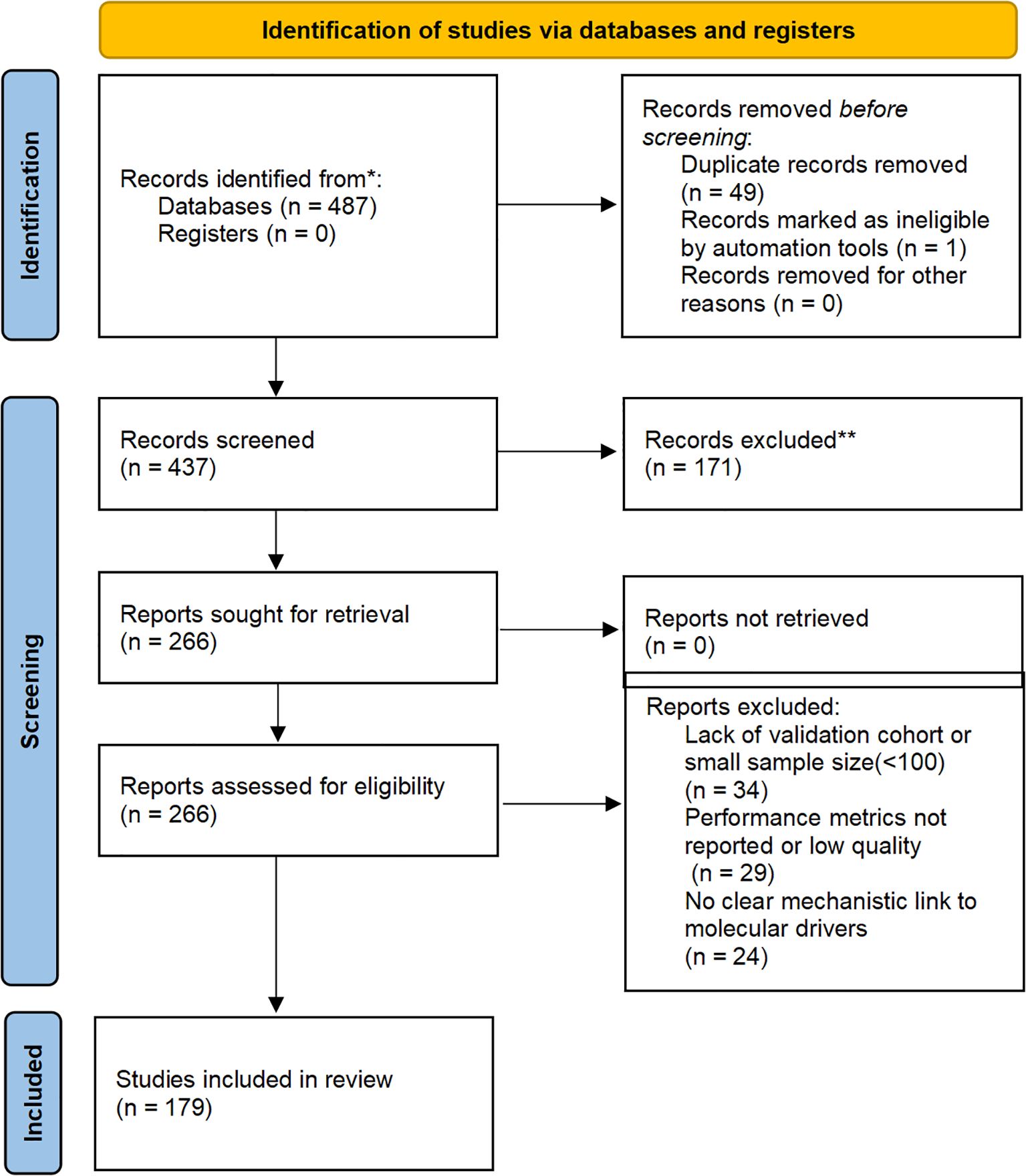

To enhance transparency in our narrative review, we conducted a structured literature search across PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar from January 2020 to October 2025. Search terms included combinations such as “AI gynecologic oncology,” “radiogenomics ovarian cancer,” “digital biopsy cervical cancer,” and “molecular imaging endometrial cancer.” Inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed articles applying AI/deep learning to radiological imaging (CT, MRI, PET) or digital pathology for molecular profiling in ovarian, endometrial, or cervical cancers, with at least retrospective validation (≥100 patients preferred), performance metrics (e.g., AUC ≥0.70), and explicit mechanistic links to drivers like HRD or MSI. From 487 initial records, duplicates were removed (n=50 excluded), titles/abstracts screened (n=171 excluded), and full-texts assessed (n=87), yielding 179 key studies for synthesis. The process is illustrated in Figure 1.

2 The AI toolkit: from feature engineering to application-driven architectures

Transforming medical images into quantitative biological probes relies on a powerful AI toolkit, moving from hypothesis-driven feature engineering to application-driven deep learning architectures (32–34). Utilizing the advanced AI architectures discussed below, researchers are now able to probe the molecular underpinnings of gynecologic cancers with unprecedented, non-invasive depth.

2.1 The classical radiomics workflow

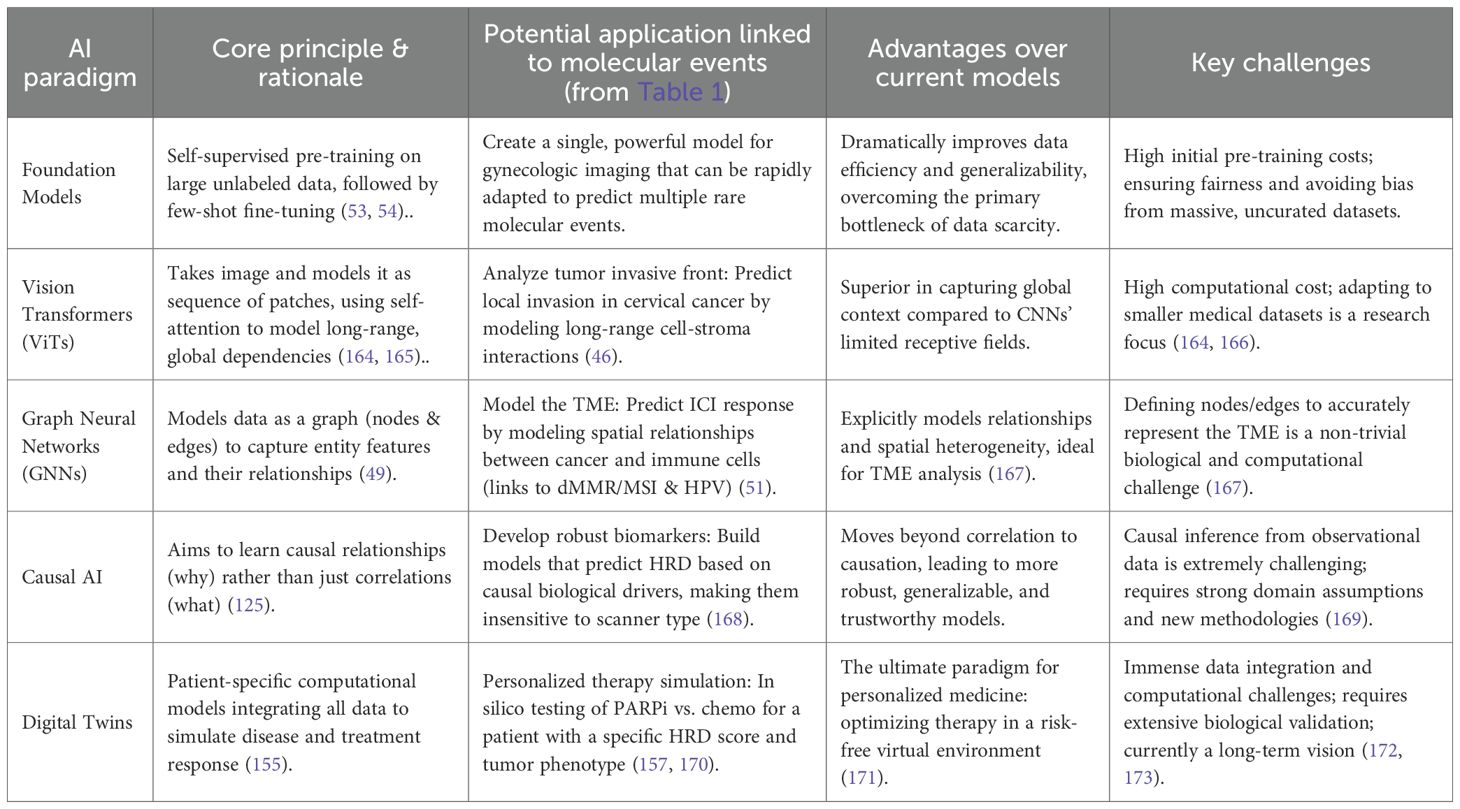

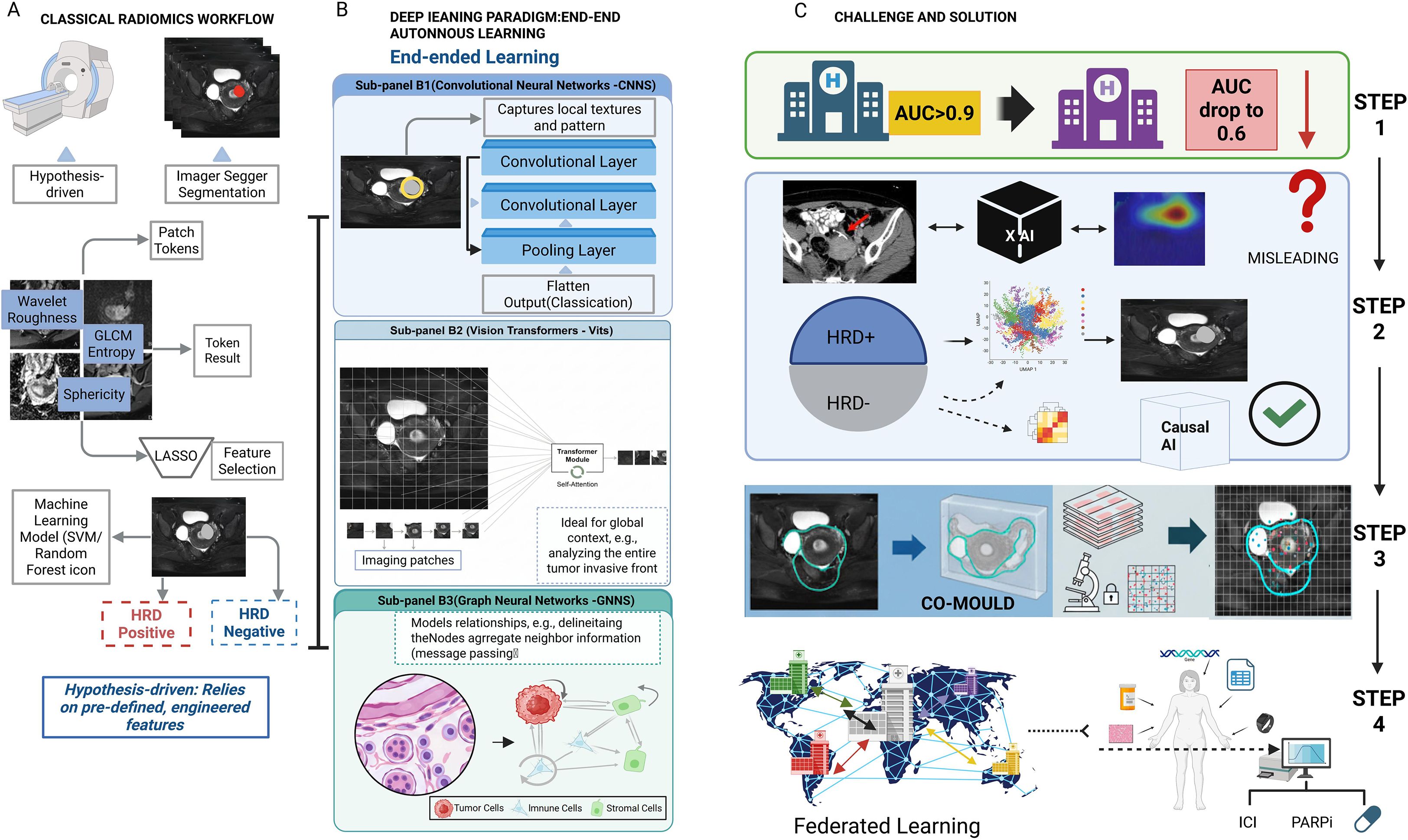

The traditional radiomics pipeline is a multi-step process, involving standardized image acquisition, reproducible segmentation, high-throughput extraction of IBSI-compliant features (shape, texture, wavelet) (35). In gynecologic oncology, these features serve as quantitative proxies for heterogeneity; for instance, high-order texture features (e.g., GLCM entropy) may reflect the chaotic micro-architecture of high-grade serous ovarian cancer (27, 64). Finally, robust feature selection (e.g., LASSO) to train machine learning models (36) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The paradigm shift to “digital biopsy” and the biological causal chain underlying imaging phenotypes. (A) Limitations of Physical Biopsy: The current “gold standard” relies on single-point sampling, which is prone to spatial bias and often underestimates tumor aggressiveness. (B) AI-Driven Digital Biopsy: A non-invasive approach that captures comprehensive intratumor heterogeneity across the entire tumor volume. (C) Decoding the Biological Causal Chain: This panel links molecular events to imaging signatures: HRD induces genomic chaos and necrosis, manifesting as high texture entropy and irregular morphology; dMMR/MSI-H triggers immune infiltration (e.g., Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction), resulting in distinct peritumoral texture features; and HPV integration drives structural disorganization, reflected as a heterogeneous “salt-and-pepper” texture on ADC maps.

2.2 Deep learning: the end-to-end autonomous learning paradigm

Deep learning (DL) represents a fundamental shift (37), using deep neural networks (DNNs) to learn relevant features automatically from raw pixels (38, 39).

2.2.1 Convolutional neural networks

As the cornerstone of image analysis (40), architectures like U-Net are now standard for cervical tumor segmentation on MRI (41), while ResNet and DenseNet (42, 43) variants effectively distinguish benign from malignant adnexal masses by learning hierarchical feature representations (174).

2.2.2 Vision transformers

ViTs treat an image as a sequence of patches and use a self-attention mechanism to model long-range, global dependencies (44, 45). This global context modeling is particularly powerful for analyzing the tumor invasive front, a complex micro-anatomical structure whose features are strong predictors of cancer progression (46, 47). By assessing the entire tumor boundary simultaneously, ViTs are uniquely positioned to identify subtle patterns of invasion in cervical cancer that are missed by the limited receptive fields of CNNs (47, 48).

2.2.3 Graph neural networks

GNNs model data as a graph of nodes and edges (49) making them ideal for capturing relationships (50). This is uniquely suited for modeling the tumor microenvironment (TME) (51). For instance, in endometrial cancer, individual cells (cancer, immune, stromal) can be modeled as ‘nodes’ and their spatial adjacencies as ‘edges.’ This topology-aware approach allows the GNN to quantify the interplay between tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and cancer cells—such as the Crohn’s-like lymphocytic response—which is a key predictor of MSI status and immunotherapy response (52).

2.3 The paradigm shift towards foundation models

The data bottleneck remains a primary challenge (38). A paradigm shift is underway from task-specific models to Foundation Models (53). Pre-trained on vast, unlabeled datasets using self-supervised learning, these models learn rich, generalizable representations of medical images (54–56). They can then be fine-tuned for specific tasks (e.g., HRD prediction) with very few labeled examples (“few-shot learning”), representing a promising solution to the data scarcity problem in medical imaging. complexity of a tumor cannot be fully captured by a single data source (56, 57). Multi-modal AI aims to build more comprehensive models by fusing data from imaging, digital pathology, and genomics (e.g., PIK3CA, KRAS mutations) (58, 59). This enables a more holistic view of the tumor’s biological state, leading to more precise predictions (59, 60).

3 Decoding key molecular signatures: from broad correlations to a mechanistic digital biopsy

The transformative potential of AI lies in its ability to non-invasively predict clinically critical molecular features (Table 1).

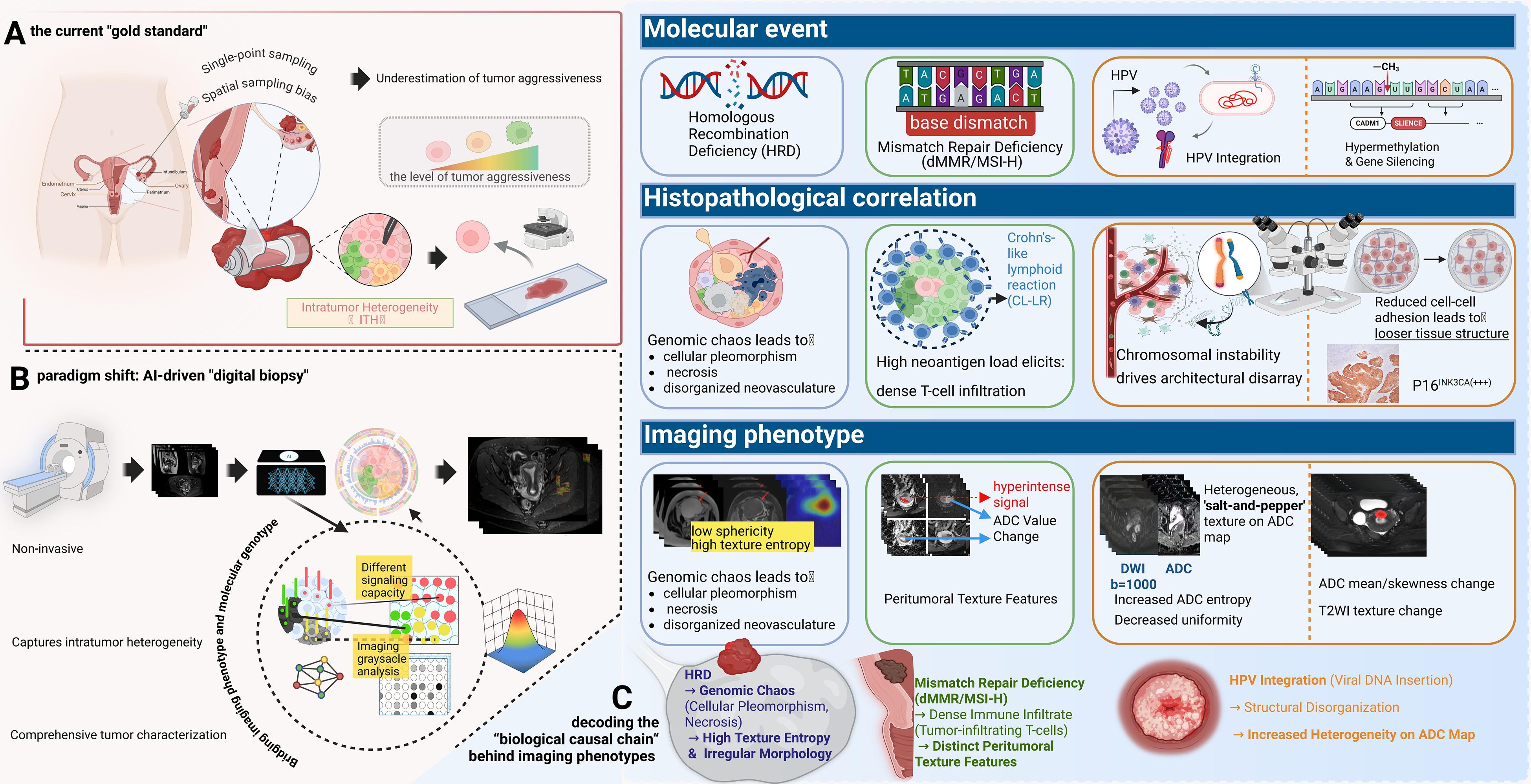

Table 1. Application cases, mechanistic links, predictive accuracies, and clinical values for AI molecular imaging in gynecologic cancers.

3.1 Ovarian cancer: deconstructing the “genomic chaos” of HRD biological rationale

The core causal chain is as follows: The molecular event of Homologous Recombination Deficiency (HRD) (61) leads to the genomic consequence of an inability to precisely repair DNA double-strand breaks. This results in the accumulation of large-scale structural variants known as “genomic scars” (loss of heterozygosity [LOH], telomeric allelic imbalance [TAI], and large-scale state transitions [LST]) (62–64). This profound genomic instability serves as an engine for rapid clonal evolution, leading to the key histopathological correlate of significant cellular pleomorphism, areas of necrosis (as some clones outgrow their blood supply), and disorganized, leaky neovasculature (64). This structural chaos directly translates into a measurable imaging phenotype. On CT/MRI, this is observed as irregular tumor morphology, central non-enhancing regions (necrosis), and heterogeneous, avid contrast enhancement (disorganized vasculature) (65). Therefore, radiomic features quantifying texture heterogeneity (e.g., entropy) and shape irregularity (e.g., low sphericity) are direct surrogates for the underlying biological state of HRD. Current Research & Critical Assessment: Numerous studies have built models to predict HRD or BRCA status based on these principles (66, 67). However, a key challenge is distinguishing the imaging phenotype of BRCA-mutated HRD from non-BRCA HRD, which may have different biological underpinnings (68). Furthermore, predicting ubiquitous mutations like TP53 remains a complex task, though it is often linked to features of necrosis and architectural disarray (69).

3.2 Endometrial cancer: linking MSI to histopathological immune signatures biological rationale

The molecular event of Mismatch Repair Deficiency (dMMR) leads to high microsatellite instability (MSI-H) (17). The immunological consequence is the accumulation of frameshift mutations, creating a high neoantigen load and rendering the tumor highly immunogenic (70). This elicits the key histopathological correlate of dense infiltration by cytotoxic T-lymphocytes and other immune cells, often organized into a distinct “Crohn’s-like lymphocytic response” at the tumor’s invasive margin (71). This physical immune barrier alters the tumor-stroma interface and tissue density. This leads to the imaging phenotype hypothesis that this dense peritumoral immune reaction is visible on MRI, manifesting as unique peritumoral signals (e.g., enhancement or T2 signal changes) (72). The altered internal cellular composition (mix of tumor and immune cells) also changes diffusion properties (ADC values) and texture compared to the typically “immune-desert” microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors (73).AI models have shown high accuracy in predicting MSI status from MRI (74, 75), and multi-modal models incorporating PET have further improved performance (76). These findings are analogous to successes in predicting MSI from digital pathology slides (77).

3.3 Cervical cancer: a flagship case for a mechanistic digital biopsy

As a disease with a clear viral etiology and a well-defined molecular progression, cervical cancer serves as the perfect model system to demonstrate the profound potential of the digital biopsy paradigm (10, 78).

3.3.1 AI for predicting HPV integration (a “digital karyotype”) mechanistic link

The concept of “digital karyotyping” suggests that genomic instability manifests as distinct morphological phenotypes. In cervical cancer, HPV integration induces ‘genomic scars’ and chromosomal instability (10), which may lead to cellular pleomorphism and architectural disarray. We hypothesize that these microscopic changes alter water diffusion, allowing DWI-derived texture features to potentially serve as a macroscopic ‘digital karyotype’ of tumor aggressiveness (9, 81).The molecular event of HPV integration into the host genome frequently occurs at common fragile sites, leading to the genomic consequence of significant chromosomal instability and amplification of adjacent oncogenes like MYC (10, 79). This “genomic chaos” is a direct biological driver of ITH (9). The histopathological correlate is disordered tissue architecture and marked cellular pleomorphism (4). This structural disarray disrupts the uniform environment for water molecule diffusion, creating complex interfaces between cell populations, which translates to a measurable imaging phenotype of increased high-order texture features (higher entropy, lower uniformity in GLCM) and a more heterogeneous ADC map on MRI (80, 81).

The core hypothesis is that an AI model can learn these textural and diffusion signatures to non-invasively predict HPV integration status, providing a powerful risk stratification tool beyond simple HPV DNA detection (82).

3.3.2 AI for predicting DNA methylation (a “digital methylome”) mechanistic link

The molecular event of hypermethylation and believes that the epigenetic state of the host tumor suppressor genes is one of the most important drivers of cervical cancer (83, 84). In recent years, the role of DNA methylation as an important indicator for the early detection of cervical cancer has been confirmed. For instance, methylation panels targeting key genes such as ZSCAN1 and ST6GALNAC5 (e.g., the WID-qCIN test), have been validated in large-scale, real-world studies as a highly effective triage tool, highlighting their growing importance (85). The cellular consequence of silencing these genes includes reduced cell-cell adhesion and evasion of apoptosis, allowing damaged cells to survive. Concurrently, a core protein-level biomarker is the overexpression of p16INK4a. The underlying mechanism is directly linked to the E7 oncoprotein of high-risk HPV types: the E7 protein interacts with and degrades the retinoblastoma protein (pRb), which lifts the negative feedback inhibition on the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a, leading to its massive intracellular accumulation. This serves as a hallmark event of HPV-driven cellular transformation (86). The histopathological correlate is a less cohesive, more disorganized tissue structure with an altered ratio of viable to apoptotic cells, changing the density of the xtracellular matrix. This directly impacts the imaging phenotype: these microstructural changes alter the mobility of water molecules. A looser structure may increase the extracellular water space, leading to higher ADC values, while uncontrolled proliferation could do the opposite. The heterogeneity of these processes across the tumor is captured by texture features on ADC maps and T2-weighted images.

The feasibility of predicting DNA methylation from MRI is no longer purely hypothetical. High-impact studies in other cancers (e.g., glioblastoma) have already demonstrated a strong correlation between global DNA methylation levels and specific radiomic features (87). The hypothesis is that a similar “digital methylome” model can be built for cervical cancer, elevating the digital biopsy from the genetic to the epigenetic level.

However, decoding these tumor cell-intrinsic molecular features is only the beginning of the story. A core concept in modern oncology is that a tumor is not merely a collection of malignant cells, but a complex and dynamically evolving community of cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, and vasculature (4). Therefore, to truly understand and ultimately control the tumor, we must achieve a “leap in scale”: from decoding the biology of the “single cancer cell” to delineating the complex biological behavior of the “entire tumor ecosystem.

4 Delineating the tumor microenvironment and guiding therapy

Building upon the decoding of cell-intrinsic molecular features from imaging in the previous section, this section elevates the perspective to a more macroscopic biological scale: the tumor microenvironment (TME). Beyond cell-intrinsic features, AI can characterize the broader TME.

4.1 Characterizing “cold” and “hot” immune landscapes

Tumors are broadly categorized into “hot” (inflamed) and “cold” (immune-desert) phenotypes, a critical distinction for immunotherapy (92, 93). For example, MSI-high endometrial cancers typically present as “hot” tumors with dense CD8+ T-cell infiltration, whereas many ovarian cancers exhibit a “cold”, immunosuppressive stroma.The rationale is that this immune infiltration alters tissue density and vascularity, creating a detectable radiomic signature—such as specific texture patterns at the tumor-stroma interface. AI models have successfully predicted ICI response in other cancers from CT scans (94). Similar work in gynecologic cancers is emerging (95).

4.2 Assessing tumor hypoxia and guiding “dose-painting” radiotherapy

Hypoxia drives treatment resistance (96, 97). Functional imaging can visualize hypoxic regions (98), and AI can generate voxel-level hypoxia maps. This is crucial for “dose-painting” radiotherapy, where radiation doses are adaptively escalated to the most resistant subregions (99, 100).

4.3 Delta-radiomics: gaining insight into early treatment response

RECIST 1.1 criteria are often a late indicator of response (101). Delta-radiomics analyzes the change (Δ) in radiomic features between baseline and early on-treatment scans (102, 103). Effective therapy induces rapid cellular changes that alter imaging textures long before tumor shrinkage (104, 105). This has shown great promise for early response assessment in ovarian and cervical cancer (105, 106).

4.4 AI in predicting radiotherapy toxicity: protecting the patient

While “dose-painting” focuses on escalating therapeutic effects, an equally critical clinical challenge is the mitigation of therapeutic harm. In gynecologic oncology, particularly for cervical and endometrial cancers, radiotherapy is a cornerstone of treatment, but it carries a significant risk of acute and late toxicity to surrounding organs at risk (OARs), such as the bladder and rectum, leading to conditions like radiation cystitis and proctitis that severely impact patient quality of life (107). Predicting which patients are at high risk for severe toxicity is a key unmet need for treatment individualization.

AI and machine learning models offer a powerful new solution (108, 109). By integrating multi-dimensional data, these models can build complex, non-linear predictive tools to identify high-risk patients before treatment initiation (110). The input features for these models are diverse, typically including: 1) Clinical features like patient age, BMI, comorbidities (e.g., Charlson Comorbidity Index), and performance status (KPS); 2) Dosimetric features extracted from dose-volume histograms (DVHs), such as the minimum dose to 2cc (D2cc of the rectum or bladder; and 3) Radiomic features from pre-treatment CT or MRI scans that quantify tissue texture and morphology of the OARs (111).

Current research has demonstrated the promise of this approach, with models based on Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, and other architectures achieving encouraging performance (often with an AUC > 0.7, considered clinically useful) in predicting grade 3 or higher toxicities (108, 112). However, echoing the challenges discussed in the next section, these models often suffer from a lack of generalizability and external validation, underscoring the critical need for standardized data collection and multi-institutional collaborative studies to translate this potential into a reliable clinical tool (108, 110, 113).

5 The path to clinical translation: from algorithms to clinical practice

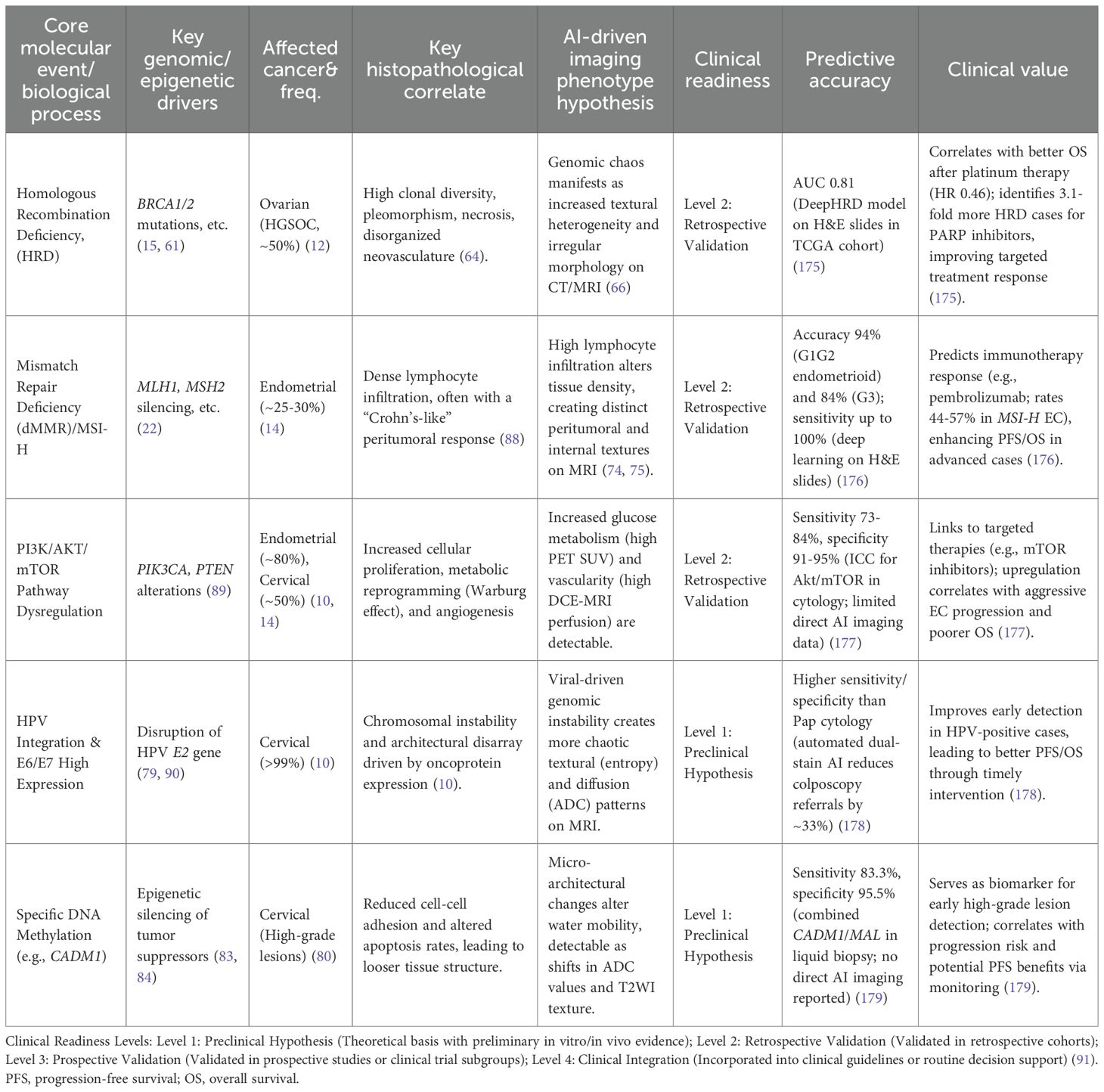

Despite immense promise, translating AI models into clinical practice faces significant hurdles (114) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Comparison of classical radiomics versus deep learning paradigms and strategies for clinical translation. (A) Classical Radiomics Workflow: A hypothesis-driven pipeline involving tumor segmentation, extraction of handcrafted features (e.g., GLCM, wavelet), and feature selection (LASSO) to train machine learning classifiers. (B) Deep Learning Paradigm: An end-to-end autonomous learning approach comprising: (B1) CNNs for capturing local textures; (B2) Vision Transformers (ViTs) for encoding global context via self-attention; and (B3) Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for modeling cellular topology and neighbor relationships. (C) Challenges and Solutions: The diagram outlines steps to bridge clinical gaps. Federated Learning addresses generalization issues (AUC drops). The CO-MOULD framework serves as a central engine for precise HRD stratification. Finally, Causal AI is integrated to filter misleading confounders, guiding targeted therapies like ICI and PARP inhibitors.

5.1 Generalizability and reproducibility: “from my data to your data”

Many models fail to generalize due to “dataset shift” (115, 116). While “underspecification” is a correct term (117), a more mechanistic explanation for these failures is the phenomenon of “Shortcut Learning” (118). Shortcut learning describes a model’s tendency not to learn the intended, biologically relevant causal features of a disease, but to instead seize upon spurious, non-generalizable correlations that happen to be associated with the label in the training data. For example, a model might learn to associate the presence of a surgical clip, text annotations on an image, or the unique noise profile of a specific scanner with a particular diagnosis, rather than the actual tumor morphology (119). When deployed on new data from a different institution lacking these “shortcuts,” the model’s performance collapses, revealing it never learned the underlying biology at all. This is a primary threat to model credibility. Rigorous, independent, multi-center external validation is the non-negotiable minimum standard (120). The significant variability in MRI and PET parameters across institutions is a particularly acute bottleneck.

5.2 Beyond explainability: the need for causal AI and interpretable-by-design models

Clinicians are rightfully hesitant to trust “black box” algorithms (121, 122). While Explainable AI (XAI) techniques like Grad-CAM (123) and SHAP (124) provide post-hoc correlations, their value in high-stakes clinical decisions is fundamentally limited because they reveal correlation, not causation. These methods show what a model is looking at, but cannot guarantee why it is looking there (125). Critically, if a model has learned via a “shortcut,” XAI heatmaps may misleadingly highlight a confounding artifact, providing a false sense of security and an incorrect explanation to the clinician (126, 127).

The next frontier is therefore Causal AI, which represents a paradigm shift from asking “what” to asking “why” (128). The goal of Causal AI is to learn a model that reflects the true biological cause-and-effect chain. For instance, a causal model for HRD prediction would not merely correlate image texture with the label, but would learn to identify the specific imaging manifestations of disorganized neovasculature and necrosis that are caused by HRD-driven genomic instability. Such a model, grounded in causality, is inherently more robust to confounders and more trustworthy. Furthermore, this aligns with a growing movement towards interpretable-by-design (“white box”) models, which, as argued by proponents like Cynthia Rudin, offer a more reliable path to clinical trust than attempting to explain a “black box” post-hoc (126, 129).

5.3 The data bottleneck and the need for a gold standard validation

The biggest bottleneck remains the availability of high-quality, curated, multi-modal data governed by FAIR principles (130, 131). Moreover, for the digital biopsy paradigm to be validated, a new “gold standard” is required (132). Spatial Transcriptomics (ST) is the definitive technology for this (133, 134). By co-registering pre-operative imaging with post-operative ST data from the same tumor, one can directly verify whether a radiomic feature for “immune hot” truly corresponds to a region with high T-cell gene expression (134–136). ST is not just a research tool; it is the necessary ground truth for validating the biological basis of any digital biopsy model before clinical consideration (137).

This vision is no longer hypothetical but is being actively implemented in pioneering clinical trials. A perfect exemplar is the NCT06324175 (CO-MOULD) trial for high-grade serous ovarian cancer. This study directly tackles the core challenge of radiogenomic validation: achieving perfect spatial co-registration between in vivo imaging and ex vivo tissue analysis. The trial employs an innovative methodology: based on a patient’s pre-operative CT/MRI scans, a patient-specific 3D-printed mould of the tumor is created. After surgical resection, this mould acts as a precise cutting guide, allowing pathologists to slice the tumor along anatomical planes that perfectly correspond to the original imaging slices (e.g., axial plane) (138).

The significance of this technique is profound. It enables, for the first time, a direct, spatially-matched validation of whether a radiomic feature observed in a specific tumor “habitat” on an MRI scan truly corresponds to a specific gene expression profile (via ST) or histological pattern at that exact physical location. This represents a revolutionary leap from macro-level, whole-tumor correlation studies to micro-level, spatially-resolved ground-truth validation, setting a new, rigorous standard for the entire digital biopsy field (138).

5.4 Federated learning: collaborative innovation while protecting privacy

For rare diseases, federated learning provides an elegant solution (139). Enables multiple centers to collaboratively train a global model while never accessing private patient data (140, 141). Key challenge is to address data heterogeneity (non-IID data) across centers, a problem being addressed by emerging techniques like federated personalization (142–144).

5.5 Clinical integration and regulatory approval

An AI tool must integrate seamlessly into clinical workflows (145). As “Software as a Medical Device” (SaMD), diagnostic AI tools require rigorous regulatory approval from bodies like the FDA (146) (Table 2).

6 Conclusion and future perspectives

Artificial intelligence is no longer a distant concept but an increasingly imminent clinical reality in gynecologic oncology (147–149). We are on the cusp of a paradigm shift: medical imaging is evolving from a qualitative, anatomical tool into a powerful, quantitative probe capable of non-invasively decoding the core biology of a patient’s cancer (150). We have moved beyond simple prognosis to inferring specific, actionable molecular targets directly from pixels.

The road ahead is paved with immense opportunity. The next wave of innovation will stem from foundation models (53, 151). These models are usually pre-trained on large, unlabeled data sets using self-supervised learning algorithms., such as contrastive learning (e.g., ConVIRT, MedCLIP), which learns rich visual representations by aligning paired images and their corresponding text reports (152). However, their development in medicine faces unique challenges, including: 1) the scarcity of large-scale, diverse, and publicly available clinical imaging datasets; 2) the immense computational resources required to train on 3D volumetric data like CT and MRI; and 3) significant regulatory and ethical hurdles related to fairness, bias, and patient privacy (153). The deep fusion of imaging with spatial omics and liquid biopsies, and widespread implementation of privacy-preserving federated learning will also drive innovation (154).

The ultimate vision is the creation of patient-specific “digital twins”—in silico models that integrate all longitudinal data to simulate disease progression and predict individual responses to therapies, enabling truly dynamic, personalized treatment plan selection in a risk-free environment (155–157). However, the path to this vision is fraught with immense challenges. These include the profound complexity of integrating multi-scale longitudinal data (from genomics to imaging), the difficulty of biologically validating that the virtual model accurately reflects in vivo processes, and formidable computational, ethical, and regulatory barriers (158). Despite these hurdles, preliminary successes are emerging. For instance, technologies like FarrSight®-Twin have demonstrated the ability to accurately replicate the results of real-world clinical trials in silico for cancers including ovarian cancer, suggesting that, while challenging, the digital twin is steadily moving from a purely conceptual future to a scientific reality.

Turning this vision into reality requires unprecedented collaboration. We must insist on the highest standards of scientific rigor, champion high-quality data sharing, and demand algorithmic transparency and causality (159, 160). Only then can we fully harness the power of AI to deconstruct the complexity of gynecologic cancers, pixel by pixel, and deliver on the ultimate promise of precision medicine for every patient (161–163).

7 Clinical implications of the digital biopsy paradigm

Clinical integration is envisioned as a multi-step workflow. Representative models like DeepHRD (175) have demonstrated the feasibility of predicting molecular status from histology, a concept now expanding to radiology. A potential workflow includes: 1) Diagnostic Triage (e.g., distinguishing benign/malignant ovarian cysts via CT (174)); 2) Risk Stratification (e.g., predicting cervical cancer prognosis via MRI (81)); and 3) Therapeutic Prediction (e.g., using “digital twins” to simulate PARP inhibitor response (170)), thereby guiding precision management.

Guiding precision therapy: The paradigm provides imaging-based evidence to select targeted therapies, such as identifying HRD status to inform the use of PARP inhibitors in ovarian cancer or predicting MSI-H status for immune checkpoint inhibitors in endometrial cancer.

Optimizing risk stratification: It offers a more nuanced view of disease progression beyond simple HPV DNA detection in cervical cancer by non-invasively predicting molecular events like viral integration.

Characterizing the tumor microenvironment: AI can delineate “hot” vs. “cold” immune landscapes to predict immunotherapy response, providing insights that transcend the tumor cell itself.

Personalizing radiotherapy: This technology enables “dose-painting” by mapping tumor hypoxia and helps mitigate harm by predicting patients at high risk for severe radiotherapy-related toxicity.

Enabling early response assessment: Through “delta-radiomics,” clinicians can assess therapeutic response much earlier than traditional criteria, allowing for timely adjustments to treatment plans.

8 Key takeaways for future research and clinical translation

Expanding AI from molecular profiling to diagnostic triage: Beyond predicting molecular status, AI should be leveraged for accurate differentiation between benign and malignant gynecologic lesions. Emerging studies already demonstrate exceptional performance (e.g., AUC 0.97 for tumoral vs. non-tumoral ovarian lesions on contrast-enhanced CT, with further subtyping of endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer at AUC 0.85) (174). Integrating this diagnostic capacity into clinical workflows will enable fertility-sparing decisions, reduce overtreatment, and optimize follow-up strategies, thereby extending the value of AI-driven imaging across the entire patient journey.

Prioritizing rigorous validation: The foremost challenge is model generalizability. Future research must prioritize rigorous, independent, multi-center external validation to combat “shortcut learning” and ensure that AI models are robust and reliable across different patient populations and imaging equipment.

Moving from correlation to causation: For AI to be trusted in high-stakes clinical decisions, the field must evolve from explainable AI (XAI), which only reveals correlations, to Causal AI. Developing models that learn the underlying biological cause-and-effect chains is essential for creating trustworthy and robust clinical tools.

Establishing a new gold standard: The clinical translation of digital biopsies requires an accepted “ground truth” for validation. Spatial transcriptomics, especially when combined with innovative co-registration techniques like the 3D-printed moulds used in the CO-MOULD trial, represents the necessary standard to biologically validate imaging-based predictions.

Harnessing next-generation AI: Foundation models, pre-trained on vast datasets, hold immense promise for overcoming data scarcity in medicine. However, their development requires addressing significant challenges related to data availability, computational cost, and ethical considerations such as fairness and bias.

Embracing collaborative and privacy-preserving models: Federated learning offers a critical solution to the data bottleneck. Fostering such collaborations is key to developing large-scale, diverse training datasets by allowing multiple institutions to train powerful models without compromising patient privacy.

Pursuing the “digital twin” as the ultimate goal: While a long-term vision, the patient-specific “digital twin” represents the pinnacle of personalized medicine, enabling in silico clinical trials to optimize therapy. Realizing this vision will require unprecedented interdisciplinary collaboration to overcome immense data integration, biological validation, and computational challenges.

Author contributions

QK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. YB: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was provided financial support from the following projects: the 2023 ‘Tianshan Talents’ Medical and Health Training Program of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (grant no. TSYC202301B083), and the 2025 Innovation and Entrepreneurship Fund of Xinjiang Medical University (grant no. CXCY2025014).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Gerstung M, Jolly C, Leshchiner I, Dentro SC, Gonzalez S, Rosebrock D, et al. The evolutionary history of 2,658 cancers. Nature. (2020) 578:122–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1907-7

2. Turajlic S, Sottoriva A, Graham T, and Swanton C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. (2019) 20:404–16. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0114-6

3. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA Jr., and Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. (2013) 339:1546–58. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122

4. Hanahan D and Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. (2011) 144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

5. Marusyk A, Almendro V, and Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. (2012) 12:323–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc3261

6. Dagogo-Jack I and Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2018) 15:81–94. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166

7. Zhu Q, Dai H, Qiu F, Lou W, Wang X, Deng L, et al. Heterogeneity of computational pathomic signature predicts drug resistance and intra-tumor heterogeneity of ovarian cancer. Transl Oncol. (2024) 40:101855. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2023.101855

8. Eich M-L, Siemanowsk-Hrach J, Drebber U, Friedrichs N, Mallmann P, Domröse C, et al. Assessment of p53 in endometrial carcinoma biopsy and corresponding hysterectomy cases in a real-world setting: which cases need molecular work-up? Cancers (Basel). (2025) 17:1506. doi: 10.3390/cancers17091506

9. Burrell RA, McGranahan N, Bartek J, and Swanton C. The causes and consequences of genetic heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Nature. (2013) 501:338–45. doi: 10.1038/nature12625

10. Network CGAR. Integrated genomic and molecular characterization of cervical cancer. Nature. (2017) 543:378. doi: 10.1038/nature21386

11. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. (2021) 71:209–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660

12. Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, and Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. (2019) 393:1240–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32552-2

13. Network CGAR. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature. (2011) 474:609. doi: 10.1038/nature10166

14. Levine DA and Network CGAR. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. (2013) 497:67–73. doi: 10.1038/nature12113

15. Konstantinopoulos PA, Norquist B, Lacchetti C, Armstrong D, Grisham RN, Goodfellow PJ, et al. Germline and somatic tumor testing in epithelial ovarian cancer: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. (2020) 38:1222–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02960

16. González-Martín A, Pothuri B, Vergote I, DePont Christensen R, Graybill W, Mirza MR, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. New Engl J Med. (2019) 381:2391–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962

17. Oaknin A, Bosse T, Creutzberg C, Giornelli G, Harter P, Joly F, et al. Endometrial cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. (2022) 33:860–77. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.05.009

18. Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, Fotopoulou C, Gaffney D, Kehoe S, et al. Endometrial Cancer Staging Subcommittee, FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int J Gynecology Obstetrics. (2023) 162:383–94. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.14923

19. Menendez-Santos M, Gonzalez-Baerga C, Taher D, Waters R, Virarkar M, and Bhosale P. Endometrial cancer: 2023 revised FIGO staging system and the role of imaging. Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:1869. doi: 10.3390/cancers16101869

20. Lee V, Murphy A, Le DT, and Diaz LA Jr. Mismatch repair deficiency and response to immune checkpoint blockade. oncologist. (2016) 21:1200–11. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0046

21. Oaknin A, Tinker AV, Gilbert L, Samouëlian V, Mathews C, Brown J, et al. Clinical activity and safety of the anti–programmed death 1 monoclonal antibody dostarlimab for patients with recurrent or advanced mismatch repair–deficient endometrial cancer: a nonrandomized phase 1 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. (2020) 6:1766–72. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4515

22. Cohen R, Buhard O, Cervera P, Hain E, Dumont S, Bardier A, et al. Clinical and molecular characterisation of hereditary and sporadic metastatic colorectal cancers harbouring microsatellite instability/DNA mismatch repair deficiency. Eur J Cancer. (2017) 86:266–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.09.022

23. Heitzer E, Haque IS, Roberts CE, and Speicher MR. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat Rev Genet. (2019) 20:71–88. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0071-5

24. Swanton C. Intratumor heterogeneity: evolution through space and time. Cancer Res. (2012) 72:4875–82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2217

25. Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, and Hricak H. Radiomics: images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiol. (2016) 278:563–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169

26. Lambin P, Leijenaar RT, Deist TM, Peerlings J, De Jong EE, Van Timmeren J, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:749–62. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141

27. Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, Parmar C, Grossmann P, Carvalho S, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun. (2014) 5:4006. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5006

28. Bodalal Z, Trebeschi S, Nguyen-Kim TDL, Schats W, and Beets-Tan R. Radiogenomics: bridging imaging and genomics. Abdominal Radiol. (2019) 44:1960–84. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02028-w

29. Wang W, Jiao Y, Zhang L, Fu C, Zhu X, Wang Q, et al. Multiparametric MRI-based radiomics analysis: differentiation of subtypes of cervical cancer in the early stage. Acta Radiol. (2022) 63:847–56. doi: 10.1177/02841851211014188

30. Apoorva V, Batra S, and Arora V. UNet with attention networks: A novel deep learning approach for DNA methylation prediction in heLa cells. Genes. (2025) 16:655. doi: 10.3390/genes16060655

31. Sahiner B, Pezeshk A, Hadjiiski LM, Wang X, Drukker K, Cha KH, et al. Deep learning in medical imaging and radiation therapy. Med Phys. (2019) 46:e1–e36. doi: 10.1002/mp.13264

32. Kaul V, Enslin S, and Gross SA. History of artificial intelligence in medicine. Gastrointest. Endosc. (2020) 92:807–12. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.040

33. Rizzo S, Botta F, Raimondi S, Origgi D, Fanciullo C, Morganti AG, et al. Radiomics: the facts and the challenges of image analysis. Eur Radiol Exp. (2018) 2:36. doi: 10.1186/s41747-018-0068-z

34. Hosny A, Parmar C, Quackenbush J, Schwartz LH, and Aerts HJ. Artificial intelligence in radiology. Nat Rev Cancer. (2018) 18:500–10. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0016-5

35. Zwanenburg A, Vallières M, Abdalah MA, Aerts HJ, Andrearczyk V, Apte A, et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology. (2020) 295:328–38. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191145

36. Parmar C, Grossmann P, Bussink J, Lambin P, and Aerts HJ. Machine learning methods for quantitative radiomic biomarkers. Sci Rep. (2015) 5:13087. doi: 10.1038/srep13087

37. LeCun Y, Bengio Y, and Hinton G. Deep learning. Nature. (2015) 521:436–44. doi: 10.1038/nature14539

38. Litjens G, Kooi T, Bejnordi BE, Setio AAA, Ciompi F, Ghafoorian M, et al. A survey on deep learning in medical image analysis. Med Image Anal. (2017) 42:60–88. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.07.005

39. Shen D, Wu G, and Suk H-I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. (2017) 19:221–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071516-044442

40. LeCun Y, Bottou L, Bengio Y, and Haffner P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc IEEE. (2002) 86:2278–324. doi: 10.1109/5.726791

41. Ronneberger O, Fischer P, and Brox T. (2015). U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation, in: International Conference on Medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, (Cham (Switzerland): Springer) pp. 234–41.

42. He K, Zhang X, Ren S, and Sun J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. Proc IEEE Conf Comput Vision Pattern recognition. (2016), 770–8. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2016.90

43. Huang G, Liu Z, van der Maaten L, and Weinberger KQ. Densely connected convolutional networks. Proc IEEE Conf Comput Vision Pattern recognition. (2017), 4700–8. doi: 10.1109/CVPR35066.2017

44. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale, in: International Conference on Learning Representations, (Virtual: International Conference on Learning Representations) (2021).

45. Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv Neural Inf Process. Syst. (2017) 30:5998–6008. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762

46. Shamshad F, Khan S, Zamir SW, Khan MH, Hayat M, Khan FS, et al. Transformers in medical imaging: A survey. Med Image Anal. (2023) 88:102802. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2023.102802

47. Takahashi S, Sakaguchi Y, Kouno N, Takasawa K, Ishizu K, Akagi Y, et al. Comparison of vision transformers and convolutional neural networks in medical image analysis: A systematic review. J Med Syst. (2024) 48:84. doi: 10.1007/s10916-024-02105-8

48. Raghu M, Unterthiner T, Kornblith S, Zhang C, and Dosovitskiy A. Do vision transformers see like convolutional neural networks? Adv Neural Inf Process. Syst. (2021) 34:12116–28. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762

49. Zhou J, Cui G, Hu S, Zhang Z, Yang C, Liu Z, et al. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open. (2020) 1:57–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aiopen.2021.01.001

50. Chami I, Abu-El-Haija S, Perozzi B, Ré C, and Murphy K. Machine learning on graphs: A model and comprehensive taxonomy. J Mach Learn Res. (2022) 23:1–64. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2005.03675

51. Gogoshin G and Rodin AS. Graph neural networks in cancer and oncology research: Emerging and future trends. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:5858. doi: 10.3390/cancers15245858

52. Zhao M, Yao S, Li Z, Wu L, Xu Z, Pan X, et al. The Crohn’s-like lymphoid reaction density: a new artificial intelligence quantified prognostic immune index in colon cancer. Cancer Immunology Immunotherapy. (2022) 71:1221–31. doi: 10.1007/s00262-021-03079-z

53. Bommasani R. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv. (2021) 2108:07258. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2108.07258

54. Moor M, Banerjee O, Abad ZSH, Krumholz HM, Leskovec J, Topol EJ, et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature. (2023) 616:259–65. doi: 10.1038/s41586-023-05881-4

55. Nasajpour M, Pouriyeh S, Parizi RM, Han M, Mosaiyebzadeh F, Xie Y, et al. Advances in application of federated machine learning for oncology and cancer diagnosis. Information. (2025) 16:487. doi: 10.3390/info16060487

56. Chen RJ, Ding T, Lu MY, Williamson DF, Jaume G, Song AH, et al. Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology, Nat. Med. (2024) 30:850–62. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-02857-3

57. Azizi S, Mustafa B, Ryan F, Beaver Z, Freyberg J, Deaton J, et al. Big self-supervised models advance medical image classification. Proc IEEE/CVF Int Conf Comput Vision. (2021) pp:3478–88. doi: 10.1109/ICCV48922.2021.00346

58. Cui C, Yang H, Wang Y, Zhao S, Asad Z, Coburn LA, et al. Deep multimodal fusion of image and non-image data in disease diagnosis and prognosis: a review. Prog Biomed Eng. (2023) 5:022001. doi: 10.1088/2516-1091/acc2fe

59. Cheerla A and Gevaert O. Deep learning with multimodal representation for pancancer prognosis prediction. Bioinformatics. (2019) 35:i446–54. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz342

60. Warner E, Lee J, Hsu W, Syeda-Mahmood T, Kahn CE Jr., Gevaert O, et al. Multimodal machine learning in image-based and clinical biomedicine: Survey and prospects. IJCV. (2024) 132:3753–69. doi: 10.1007/s11263-024-02032-8

61. van der Wiel AM, Schuitmaker L, Cong Y, Theys J, Van Hoeck A, Vens C, et al. Homologous recombination deficiency scar: mutations and beyond—implications for precision oncology. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14:4157. doi: 10.3390/cancers14174157

62. Abkevich V, Timms K, Hennessy B, Potter J, Carey M, Meyer L, et al. Patterns of genomic loss of heterozygosity predict homologous recombination repair defects in epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. (2012) 107:1776–82. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.451

63. Melchor L and Benítez J. The complex genetic landscape of familial breast cancer. Hum Genet. (2013) 132:845–63. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1299-y

64. Telli ML, Timms KM, Reid J, Hennessy B, Mills GB, Jensen KC, et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score predicts response to platinum-containing neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. (2016) 22:3764–73. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2477

65. Wang Y, Lin W, Zhuang X, Wang X, He Y, Li L, et al. Advances in artificial intelligence for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer, Oncol. Rep. (2024) 51:1–17. doi: 10.3892/or.2023.8685

66. Zhang K, Qiu Y, Feng S, Yin H, Liu Q, Zhu Y, et al. Development of model for identifying homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status of ovarian cancer with deep learning on whole slide images. J Transl Med. (2025) 23:267. doi: 10.1186/s12967-025-06234-7

67. Mingzhu L, Yaqiong G, Mengru L, and Wei W. Prediction of BRCA gene mutation status in epithelial ovarian cancer by radiomics models based on 2D and 3D CT images. BMC Med Imaging. (2021) 21:180. doi: 10.1186/s12880-021-00711-3

68. Gourley C, McCavigan A, Perren T, Paul J, Michie CO, Churchman M, et al. Molecular subgroup of high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) as a predictor of outcome following bevacizumab. Am Soc Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:5502. doi: 10.1200/jco.2014.32.15_suppl.5502

69. Saxena S, Jena B, Gupta N, Das S, Sarmah D, Bhattacharya P, et al. Role of artificial intelligence in radiogenomics for cancers in the era of precision medicine. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14:2860. doi: 10.3390/cancers14122860

70. Luchini C, Bibeau F, Ligtenberg M, Singh N, Nottegar A, Bosse T, et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach, Ann. Oncol. (2019) 30:1232–43. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz116

71. Bostan I-S, Mihaila M, Roman V, Radu N, Neagu MT, Bostan M, et al. Landscape of endometrial cancer: molecular mechanisms. biomarkers target therapy Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:2027. doi: 10.3390/cancers16112027

72. Celli V, Guerreri M, Pernazza A, Cuccu I, Palaia I, Tomao F, et al. MRI-and histologic-molecular-based radio-genomics nomogram for preoperative assessment of risk classes in endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel). (2022) 14:5881. doi: 10.3390/cancers14235881

73. Zhang C, Wang M, and Wu Y. Features of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in endometrial cancer based on molecular subtype, Front. Oncol. (2023) 13:1278863. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1278863

74. Jia Y, Hou L, Zhao J, Ren J, Li D, Li H, et al. Radiomics analysis of multiparametric MRI for preoperative prediction of microsatellite instability status in endometrial cancer: a dual-center study, Front. Oncol. (2024) 14:1333020. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2024.1333020

75. Bae H, Rha SE, Kim H, Kang J, and Shin YR. Predictive value of magnetic resonance imaging in risk stratification and molecular classification of endometrial cancer. Cancers (Basel). (2024) 16:921. doi: 10.3390/cancers16050921

76. García-Vicente AM, Ortiz SAG, Perlaza-Jiménez MP, Tormo-Ratera M, Sánchez-Márquez A, Cortés-Romera M, et al. Molecular imaging in endometrial cancer: A narrative review. Cancers (2025) 17:2608. doi: 10.20944/preprints202506.1616.v1

77. Echle A, Rindtorff NT, Brinker TJ, Luedde T, Pearson AT, and Kather JN. Deep learning in cancer pathology: a new generation of clinical biomarkers. Br J Cancer. (2021) 124:686–96. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-01122-x

78. Burd EM. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2003) 16:1–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.1-17.2003

79. Wentzensen N, Schiffman M, Palmer T, and Arbyn M. Triage of HPV positive women in cervical cancer screening. J Clin Virol. (2016) 76:S49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.11.015

80. Steenbergen RD, Snijders PJ, Heideman DA, and Meijer CJ. Clinical implications of (epi) genetic changes in HPV-induced cervical precancerous lesions. Nat Rev Cancer. (2014) 14:395–405. doi: 10.1038/nrc3728

81. Zheng R-R, Cai M-T, Lan L, Huang XW, Yang YJ, Powell M, et al. An MRI-based radiomics signature and clinical characteristics for survival prediction in early-stage cervical cancer. Br J Radiol. (2022) 95:20210838. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20210838

82. İnce O, Uysal E, Durak G, Önol S, Yılmaz BD, Ertürk ŞM, et al. Prediction of carcinogenic human papillomavirus types in cervical cancer from multiparametric magnetic resonance images with machine learning-based radiomics models. Diagn. Interv. Radiol. (2023) 29:460. doi: 10.4274/dir.2022.221335

83. Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. New Engl J Med. (2008) 358:1148–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067

84. Baylin SB and Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. (2011) 11:726–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130

85. Schreiberhuber L, Barrett JE, Wang J, Redl E, Herzog C, Vavourakis CD, et al. Cervical cancer screening using DNA methylation triage in a real-world population. Nat Med. (2024) 30:2251–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-024-03014-6

86. Garg P, Krishna M, Subbalakshmi AR, Ramisetty S, Mohanty A, Kulkarni P, et al. Emerging biomarkers and molecular targets for precision medicine in cervical cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. (2024) 1879:189106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2024.189106

87. Doniselli FM, Pascuzzo R, Mazzi F, Padelli F, Moscatelli M, Akinci D’Antonoli T, et al. Quality assessment of the MRI-radiomics studies for MGMT promoter methylation prediction in glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol. (2024) 34:5802–15. doi: 10.1007/s00330-024-10594-x

88. Li J, Wu C, Hu H, Qin G, Wu X, Bai F, et al. Remodeling of the immune and stromal cell compartment by PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell. (2023) 41:1152–1169. e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.04.011

89. Avila M, Grinsfelder MO, Pham M, and Westin SN. Targeting the PI3K pathway in gynecologic Malignancies. Curr Oncol Rep. (2022) 24:1669–76. doi: 10.1007/s11912-022-01326-9

90. Mirabello L, Yeager M, Yu K, Clifford GM, Xiao Y, Zhu B, et al. HPV16 E7 genetic conservation is critical to carcinogenesis. Cell. (2017) 170:1164–1174. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.001

91. Sayyari M, Karimi H, Keshtan SB, Saleknezhad A, Bemana R, and Rezaie I. Toward a unified technology readiness ladder for clinical artificial intelligence: A systematic review and delphi synthesis. InfoScience Trends. (2025) 2:49–64. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0046

92. Galon J and Bruni D. Approaches to treat immune hot, altered and cold tumours with combination immunotherapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2019) 18:197–218. doi: 10.1038/s41573-018-0007-y

93. Zhang J, Huang D, Saw PE, and Song E. Turning cold tumors hot: from molecular mechanisms to clinical applications. Trends Immunol. (2022) 43:523–45. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2022.04.010

94. Sun R, Limkin EJ, Vakalopoulou M, Dercle L, Champiat S, Han SR, et al. A radiomics approach to assess tumour-infiltrating CD8 cells and response to anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy: an imaging biomarker, retrospective multicohort study. Lancet Oncol. (2018) 19:1180–91. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30413-3

95. Huang K, Huang X, Zeng C, Wang S, Zhan Y, Cai Q, et al. Radiomics signature for dynamic changes of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells and macrophages in cervical cancer during chemoradiotherapy. Cancer Imaging. (2024) 24:54. doi: 10.1186/s40644-024-00680-0

96. Horsman MR and Overgaard J. The impact of hypoxia and its modification of the outcome of radiotherapy. J Radiat Res. (2016) 57:i90–8. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrw007

97. Perez RC, Kim D, Maxwell AWP, and Camacho JC. Functional imaging of hypoxia: PET and MRI. Cancers (Basel). (2023) 15:3336. doi: 10.3390/cancers15133336

98. Huang M, Law HKW, and Tam SY. Use of radiomics in characterizing tumor hypoxia. Int J Mol Sci. (2025) 26:6679. doi: 10.3390/ijms26146679

99. Anghel B, Serboiu C, Marinescu A, Taciuc IA, Bobirca F, and Stanescu AD. Recent advances and adaptive strategies in image guidance for cervical cancer radiotherapy. Med (Kaunas). (2023) 59:1735. doi: 10.3390/medicina59101735

100. Heide UAVd, Houweling AC, Groenendaal G, Beets-Tan RG, and Lambin P. Functional MRI for radiotherapy dose painting. Magn Reson Imaging. (2012) 30:1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.04.010

101. Schwartz LH, Litière S, De Vries E, Ford R, Gwyther S, Mandrekar S, et al. RECIST 1.1—Update and clarification: From the RECIST committee. Eur J Cancer. (2016) 62:132–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081

102. Fave X, Zhang L, Yang J, Mackin D, Balter P, Gomez D, et al. Delta-radiomics features for the prediction of patient outcomes in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:588. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00665-z

103. Nardone V, Reginelli A, Rubini D, Gagliardi F, Del Tufo S, Belfiore MP, et al. Delta radiomics: an updated systematic review. Radiol Med. (2024) 129:1197–214. doi: 10.1007/s11547-024-01853-4

104. Wu R-R, Zhou Y-M, Xie X-Y, Chen J-Y, Quan K-R, Wei Y-T, et al. Delta radiomics analysis for prediction of intermediary-and high-risk factors for patients with locally advanced cervical cancer receiving neoadjuvant therapy. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:19409. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-46621-y

105. Cheng X, Li P, Jiang R, Meng E, and Wu H. ADC: a deadly killer of platinum resistant ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. (2024) 17:196. doi: 10.1186/s13048-024-01523-z

106. Barwick TD, Taylor A, and Rockall A. Functional imaging to predict tumor response in locally advanced cervical cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. (2013) 15:549–58. doi: 10.1007/s11912-013-0344-2

107. Mirabeau-Beale KL and Viswanathan AN. Quality of life (QOL) in women treated for gynecologic Malignancies with radiation therapy: a literature review of patient-reported outcomes. Gynecol. Oncol. (2014) 134:403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.05.008

108. Luo L, Wang J, Xie H, Chen B, Wang H, and Tang Q. Combined clinical and MRI-based radiomics model for predicting acute hematologic toxicity in gynecologic cancer radiotherapy. Front Oncol. (2025) 15. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2025.1644053

109. Le Z, Wu D, Chen X, Wang L, Xu Y, Zhao G, et al. A radiomics approach for predicting acute hematologic toxicity in patients with cervical or endometrial cancer undergoing external-beam radiotherapy. Radiother. Oncol. (2023) 182:109489. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2023.109489

110. Chen L, He Z, Ni Q, Zhou Q, Long X, Yan W, et al. Dual-radiomics based on SHapley additive explanations for predicting hematologic toxicity in concurrent chemoradiotherapy patients. Discov Oncol. (2025) 16:541. doi: 10.1007/s12672-025-02336-2

111. Lucia F, Bourbonne V, Visvikis D, Miranda O, Gujral DM, Gouders D, et al. Radiomics analysis of 3D dose distributions to predict toxicity of radiotherapy for cervical cancer. J Personalized Med. (2021) 11:398. doi: 10.3390/jpm11050398

112. Elhaminia B, Gilbert A, Scarsbrook A, Lilley J, Appelt A, and Gooya A. Deep learning combining imaging, dose and clinical data for predicting bowel toxicity after pelvic radiotherapy. Phys Imaging Radiat Oncol. (2025) 33:100710. doi: 10.1016/j.phro.2025.100710

113. Jha AK, Mithun S, Sherkhane UB, Jaiswar V, Osong B, Purandare N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prediction models used in cervical cancer. Artif Intell Med. (2023) 139:102549. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2023.102549

114. Bluemke DA, Moy L, Bredella MA, Ertl-Wagner BB, Fowler KJ, Goh VJ, et al. Assessing radiology research on artificial intelligence: a brief guide for authors, reviewers, and readers—from the radiology editorial board. Radiological Society of North America (2020) p. 487–9.

115. Gichoya JW, Banerjee I, Bhimireddy AR, Burns JL, Celi LA, Chen L-C, et al. AI recognition of patient race in medical imaging: a modelling study. Lancet Digital Health. (2022) 4:e406–14. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00063-2

116. Park SH and Han K. Methodologic guide for evaluating clinical performance and effect of artificial intelligence technology for medical diagnosis and prediction. Radiology. (2018) 286:800–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017171920

117. Beam AL, Manrai AK, and Ghassemi M. Challenges to the reproducibility of machine learning models in health care. JAMA. (2020) 323:305–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.20866

118. Geirhos R, Jacobsen J-H, Michaelis C, Zemel R, Brendel W, Bethge M, et al. Shortcut learning in deep neural networks. Nat Mach Intell. (2020) 2:665–73. doi: 10.1038/s42256-020-00257-z

119. Zech JR, Badgeley MA, Liu M, Costa AB, Titano JJ, and Oermann EK. Variable generalization performance of a deep learning model to detect pneumonia in chest radiographs: a cross-sectional study. PloS Med. (2018) 15:e1002683. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002683

120. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, and Moons KG. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. J Br Surg. (2015) 102:148–58. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9736

121. Wiens J, Saria S, Sendak M, Ghassemi M, Liu VX, Doshi-Velez F, et al. Do no harm: a roadmap for responsible machine learning for health care, Nat. Med. (2019) 25:1337–40. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0548-6

122. Vayena E, Blasimme A, and Cohen IG. Machine learning in medicine: addressing ethical challenges. PloS Med. (2018) 15:e1002689. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002689

123. Selvaraju RR, Cogswell M, Das A, Vedantam R, Parikh D, and Batra D. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient-based localization. Proc IEEE Int Conf Comput Vision. (2017), 618–26. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.2017.74

124. Lundberg SM and Lee S-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. Adv Neural Inf Process. Syst. (2017) 30:4765–74. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.1705.07874

125. Farahani FV, Fiok K, Lahijanian B, Karwowski W, Douglas PK, and Explainable AI. A review of applications to neuroimaging data. Front Neurosci. (2022) 16:906290. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.906290

126. Ghassemi M, Oakden-Rayner L, and Beam AL. The false hope of current approaches to explainable artificial intelligence in health care. Lancet Digital Health. (2021) 3:e745–50. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00208-9

127. Van der Velden BH, Kuijf HJ, Gilhuijs KG, and Viergever MA. Explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) in deep learning-based medical image analysis, Med. Image Anal. (2022) 79:102470. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2022.102470

128. Holzinger A, Langs G, Denk H, Zatloukal K, and Müller H. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdiscip reviews: Data Min knowledge Discov. (2019) 9:e1312. doi: 10.1002/widm.1312

129. Rudin C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpreta ble models instead. Nat Mach Intell. (2019) 1:206–15. doi: 10.1038/s42256-019-0048-x

130. Wilkinson MD, Dumontier M, Aalbersberg IJ, Appleton G, Axton M, Baak A, et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci Data. (2016) 3:1–9. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2016.18

131. Vesteghem C, Brøndum RF, Sønderkær M, Sommer M, Schmitz A, Bødker JS, et al. Implementing the FAIR Data Principles in precision oncology: review of supporting initiatives, Brief. Bioinform. (2020) 21:936–45. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbz044

132. Maiorano MFP, Cormio G, Loizzi V, and Maiorano BA. Artificial intelligence in ovarian cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of predictive AI models in genomics. Radiomics Immunotherapy AI. (2025) 6:84. doi: 10.3390/ai6040084

133. Asp M, Bergenstråhle J, and Lundeberg J. Spatially resolved transcriptomes—next generation tools for tissue exploration. Bioessays. (2020) 42:1900221. doi: 10.1002/bies.201900221

134. Lyubetskaya A, Rabe B, Fisher A, Lewin A, Neuhaus I, Brett C, et al. Assessment of spatial transcriptomics for oncology discovery. Cell Reports Methods (2022) 100340. doi: 10.1016/j.crmeth.2022.100340

135. Ståhl PL, Salmén F, Vickovic S, Lundmark A, Navarro JF, Magnusson J, et al. Visualization and analysis of gene expression in tissue sections by spatial transcriptomics. Science. (2016) 353:78–82. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf2403

136. Martin-Gonzalez P, Crispin-Ortuzar M, Rundo L, Delgado-Ortet M, Reinius M, Beer L, et al. Integrative radiogenomics for virtual biopsy and treatment monitoring in ovarian cancer. Insights Imaging. (2020) 11:94. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-00895-2

137. Ju HY, Youn SY, Kang J, Whang MY, Choi YJ, and Han MR. Integrated analysis of spatial transcriptomics and CT phenotypes for unveiling the novel molecular characteristics of recurrent and non-recurrent high-grade serous ovarian cancer. biomark Res. (2024) 12:80. doi: 10.1186/s40364-024-00632-7

138. Delgado-Ortet M, Reinius MAV, McCague C, Bura V, Woitek R, Rundo L, et al. Lesion-specific 3D-printed moulds for image-guided tissue multi-sampling of ovarian tumours: A prospective pilot study. Front Oncol. (2023) 13:1085874. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2023.1085874

139. Haripriya R, Khare N, and Pandey M. Privacy-preserving federated learning for collaborative medical data mining in multi-institutional settings, Sci. Rep. (2025) 15:12482. doi: 10.1038/s41598-025-97565-4

140. Sheller MJ, Edwards B, Reina GA, Martin J, Pati S, Kotrotsou A, et al. Federated learning in medicine: facilitating multi-institutional collaborations without sharing patient data. Sci Rep. (2020) 10:12598. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69250-1

141. Li T, Sahu AK, Talwalkar A, and Smith V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. ISPM. (2020) 37:50–60. doi: 10.1109/MSP.2020.2975749

142. Kaissis GA, Makowski MR, Rückert D, and Braren RF. Secure, privacy-preserving and federated machine learning in medical imaging. Nat Mach Intell. (2020) 2:305–11. doi: 10.1038/s42256-020-0186-1

143. Price WN and Cohen IG. Privacy in the age of medical big data. Nat Med. (2019) 25:37–43. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0272-7

144. Alekseenko J, Karargyris A, and Padoy N. (2024). Distance-aware non-IID federated learning for generalization and personalization in medical imaging segmentation, in: Proceedings of The 7nd International Conference on Medical Imaging with Deep Learning, PMLR, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, (Paris (France): PMLR (Proceedings of Machine Learning Research)) pp. 33–47.

145. He J, Baxter SL, Xu J, Xu J, Zhou X, and Zhang K. The practical implementation of artificial intelligence technologies in medicine. Nat Med. (2019) 25:30–6. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0307-0

146. Zhang K, Khosravi B, Vahdati S, and Erickson BJ. FDA review of radiologic AI algorithms: process and challenges. Radiology. (2024) 310:e230242. doi: 10.1148/radiol.230242

147. Rajpurkar P, Chen E, Banerjee O, and Topol EJ. AI in health and medicine. Nat Med. (2022) 28:31–8. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01614-0

148. Abràmoff MD, Lavin PT, Birch M, Shah N, and Folk JC. Pivotal trial of an autonomous AI-based diagnostic system for detection of diabetic retinopathy in primary care offices. NPJ digital Med. (2018) 1:39. doi: 10.1038/s41746-018-0040-6

149. Bi WL, Hosny A, Schabath MB, Giger ML, Birkbak NJ, Mehrtash A, et al. Artificial intelligence in cancer imaging: clinical challenges and applications. CA Cancer J Clin. (2019) 69:127–57. doi: 10.3322/caac.21552

150. Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: the convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. (2019) 25:44–56. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

151. Bi Q, Ai C, Qu L, Meng Q, Wang Q, Yang J, et al. Foundation model-driven multimodal prognostic prediction in patients undergoing primary surgery for high-grade serous ovarian cancer. NPJ Precis Oncol. (2025) 9:114. doi: 10.1038/s41698-025-00900-1

152. Paschali M, Chen Z, Blankemeier L, Varma M, Youssef A, Bluethgen C, et al. Foundation models in radiology: what, how, why, and why not. Radiology. (2025) 314:e240597. doi: 10.1148/radiol.240597

153. Noh S and Lee BD. A narrative review of foundation models for medical image segmentation: zero-shot performance evaluation on diverse modalities. Quant Imaging Med Surg. (2025) 15:5825–58. doi: 10.21037/qims-2024-2826

154. Rieke N, Hancox J, Li W, Milletari F, Roth HR, Albarqouni S, et al. The future of digital health with federated learning. NPJ digital Med. (2020) 3:119. doi: 10.1038/s41746-020-00323-1

155. Giansanti D and Morelli S. Exploring the potential of digital twins in cancer treatment: A narrative review of reviews. J Clin Med. (2025) 14:3574. doi: 10.3390/jcm14103574

156. Shen S, Qi W, Liu X, Zeng J, Li S, Zhu X, et al. From virtual to reality: innovative practices of digital twins in tumor therapy. J Transl Med. (2025) 23:348. doi: 10.1186/s12967-025-06371-z

157. Lammert J, Pfarr N, Kuligin L, Mathes S, Dreyer T, Modersohn L, et al. Large language models-enabled digital twins for precision medicine in rare gynecological tumors. NPJ Digital Med. (2025) 8:420. doi: 10.1038/s41746-025-01810-z

158. Kaul R, Ossai C, Forkan ARM, Jayaraman PP, Zelcer J, Vaughan S, et al. The role of AI for developing digital twins in healthcare: The case of cancer care. WIREs Data Min Knowledge Discov. (2023) 13:e1480. doi: 10.1002/widm.1480

159. Char DS, Shah NH, and Magnus D. Implementing machine learning in health care—addressing ethical challenges. New Engl J Med. (2018) 378:981. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1714229

160. D’Amiano AJ, Cheunkarndee T, Azoba C, Chen KY, Mak RH, and Perni S. Transparency and representation in clinical research utilizing artificial intelligence in oncology: A scoping review. Cancer Med. (2025) 14:e70728. doi: 10.1002/cam4.70728

161. Fountzilas E, Pearce T, Baysal MA, Chakraborty A, and Tsimberidou AM. Convergence of evolving artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques in precision oncology. NPJ Digital Med. (2025) 8:75. doi: 10.1038/s41746-025-01471-y

162. Collins FS and Varmus H. A new initiative on precision medicine. New Engl J Med. (2015) 372:793–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500523

163. Paiboonborirak C, Abu-Rustum NR, and Wilailak S. Artificial intelligence in the diagnosis and management of gynecologic cancer, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics n/a(n/a). (2025) 171:199–209. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.70094

164. Azad R, Kazerouni A, Heidari M, Aghdam EK, Molaei A, Jia Y, et al. Advances in medical image analysis with vision Transformers: A comprehensive review. Med Image Anal. (2024) 91:103000. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2023.103000

165. Dosovitskiy A, Beyer L, Kolesnikov A, Weissenborn D, Zhai X, Unterthiner T, et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv. (2020) 2010:11929. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929

166. Li J, Chen J, Tang Y, Wang C, Landman BA, and Zhou SK. Transforming medical imaging with Transformers? A comparative review of key properties, current progresses, and future perspectives. Med Image Anal. (2023) 85:102762. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2023.102762

167. Zhang XM, Liang L, Liu L, and Tang MJ. Graph neural networks and their current applications in bioinformatics. Front Genet. (2021) 12:690049. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2021.690049

168. Sanchez P, Voisey JP, Xia T, Watson HI, O’Neil AQ, and Tsaftaris SA. Causal machine learning for healthcare and precision medicine. R Soc Open Sci. (2022) 9:220638. doi: 10.1098/rsos.220638

169. Smit JM, Krijthe JH, Kant WMR, Labrecque JA, Komorowski M, Gommers D, et al. Causal inference using observational intensive care unit data: a scoping review and recommendations for future practice. NPJ Digit Med. (2023) 6:221. doi: 10.1038/s41746-023-00961-1

170. Strobl MAR, Martin AL, West J, Gallaher J, Robertson-Tessi M, Gatenby R, et al. To modulate or to skip: De-escalating PARP inhibitor maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer using adaptive therapy. Cell Syst. (2024) 15:510–525.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2024.04.003

171. Papachristou K, Katsakiori PF, Papadimitroulas P, Strigari L, and Kagadis GC. Digital twins’ Advancements and applications in healthcare, towards precision medicine. J Pers Med. (2024) 14:1101. doi: 10.3390/jpm14111101

172. Domenico M, Allegri L, Caldarelli G, d’Andrea V, Camillo B, Rocha LM, et al. Challenges and opportunities for digital twins in precision medicine from a complex systems perspective. NPJ Digital Med. (2025) 8:37. doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01402-3

173. Jamshidi MB, Hoang DT, Nguyen DN, Niyato D, and Warkiani ME. Revolutionizing biological digital twins: Integrating internet of bio-nano things, convolutional neural networks, and federated learning. Comput Biol Med. (2025) 189:109970. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2025.109970

174. Macis C, Santoro M, Zybin V, Di Costanzo S, Coada CA, Dondi G, et al. A convolutional neural network tool for early diagnosis and precision surgery in endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. Appl Sci. (2025) 15:3070. doi: 10.3390/app15063070

175. Bergstrom EN, Abbasi A, Díaz-Gay M, Galland L, Ladoire S, Lippman SM, et al. Deep learning artificial intelligence predicts homologous recombination deficiency and platinum response from histologic slides. J Clin Oncol. (2024) 42:3550–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.23.02641

176. Wang CW, Muzakky H, Firdi NP, Liu TC, Lai PJ, Wang YC, et al. Deep learning to assess microsatellite instability directly from histopathological whole slide images in endometrial cancer. NPJ Digit Med. (2024) 7:143. doi: 10.1038/s41746-024-01131-7

177. Ma K, Yang X, Yang Z, Meng Y, Wen J, Chen R, et al. Immunocytochemical examination of Akt, mTOR, and Pax-2 for endometrial carcinoma through thin-layer endometrial cytology. Front Med (Lausanne). (2025) 12:1576060. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1576060

178. Wentzensen N, Lahrmann B, Clarke MA, Schiffman M, Cheung LC, Katki HA, et al. Accuracy and efficiency of deep-learning-based automation of dual stain cytology in cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. (2021) 113:72–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa066

Keywords: artificial intelligence, digital biopsy, foundation models, gynecologic oncology, radiogenomics, tumor heterogeneity

Citation: Kong Q and Ban Y (2026) AI-driven radiogenomics in gynecologic oncology: from radiological digital biopsy to a new paradigm in precision therapy. Front. Oncol. 16:1745519. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2026.1745519

Received: 13 November 2025; Accepted: 19 January 2026; Revised: 15 January 2026;

Published: 04 February 2026.

Edited by:

Stefania Rizzo, University of Italian Switzerland, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Camelia Alexandra Coada, University of Medicine and PHarmacy “Iuliu Ha-ieganu”, RomaniaAshok Kumar Sah, Amity University Gurgaon, India

Jean-Sebastien Frenel, Institut de Cancérologie de l’Ouest (ICO), France

Copyright © 2026 Kong and Ban. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yunqing Ban, YmFueXFfNUAxNjMuY29t

Qiqi Kong

Qiqi Kong Yunqing Ban

Yunqing Ban