- 1Department of Pediatrics, Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy

- 2Mucosal Immunology and Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital-Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Background and aim: The prevalence and clinical spectrum of symptoms due to inadvertent gluten exposure in children with celiac disease (CeD) on a gluten-free diet (GFD) are not well defined. This study aimed to assess these acute reactions through an online survey.

Methods: Parents of children with CeD treated with a GFD for at least 12 months completed an online questionnaire. The survey focused on symptoms occurring within 24 h of gluten-contaminated food ingestion.

Results: Data were collected for 296 children. Acute reactions after unintentional gluten ingestion were reported in 98 cases (33.1%). The most common symptoms were abdominal pain (57.1%), diarrhea (42.9%), vomiting (31.6%), headache (12.2%), and fatigue (14.3%). Less frequent symptoms included nausea, constipation, urticaria, aphthous stomatitis, and arthropathy (each ∼5%–7%). In 86% of cases, symptoms appeared within 2–3 h. Gluten exposure most often occurred while dining out, especially in restaurants and school cafeterias.

Conclusions: One-third of children with CeD on a GFD experience acute reactions to accidental gluten ingestion. These reactions typically arise rapidly and are dominated by gastrointestinal symptoms, aligning with reports from existing literature, where vomiting and nausea have been observed in 3%–46% of patients at the time of CeD diagnosis and in 13%–61% during gluten challenge.

1 Introduction

Celiac disease (CeD) is an autoimmune enteropathy characterized by a chronic inflammatory response to the ingestion of gluten, a protein found in wheat, rye, and barley (1, 2). The disease can cause a wide variety of symptoms, both gastrointestinal and extraintestinal, and is estimated to affect approximately 1%–2% of the global population (3–5).

The treatment of CeD is a strict, lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD) which allows the intestinal mucosa to heal and prevents long-term complications of the disease (6, 7). However, some patients continue to report persistent symptoms despite following a GFD, often caused by gluten contamination into the diet (8).

Adhering to a GFD, which eliminates a common dietary staple across many countries, poses significant challenges and can negatively impact patients' psychosocial well-being and quality of life, particularly during vulnerable periods like adolescence. The complete avoidance of gluten is difficult to achieve, as naturally gluten-free items like oats and lentils can be cross-contaminated during processing. Furthermore, gluten is a widely used ingredient added for its functional properties and can be found in unsuspected food products (9). Cross-sectional studies have found that up to 50% of individuals with CeD who follow a GFD report consuming gluten, either intentionally or unintentionally (10, 11). Incomplete adherence to a GFD is more prevalent among males, adolescents, and individuals with clinically silent CeD (12). This unintended gluten intake can trigger an immune response and the reappearance of gastrointestinal and other symptoms (13, 14). Symptoms of active CeD usually manifest gradually over weeks or months. However, after starting treatment with the GFD, acute reactions to gluten ingestion are frequently reported by patients. To date, the prevalence of symptomatic acute reactions following unintentional gluten ingestion while on a GFD has not been fully investigated, particularly in children.

The aim of this study was to assess the occurrence and characteristics of such symptoms through an online survey of a large cohort of patients with CeD.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design

This is a cross-sectional study, with data collected through an online survey performed from March to July 2024 at a regional referral center for pediatric CeD (Ancona, Italy). Prior to participating in the survey, parents of children with CeD who had been followed for at least 1 year were provided comprehensive details about the study and required to give written informed consent. All respondents were informed about the study's objectives, data usage, privacy, anonymity, confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of their participation, including the right to withdraw. The survey took approximately 15 min to complete. Participants who reported experiencing symptoms were followed up by a trained dietitian to verify the accuracy of their responses. Individuals were classified as having a positive reaction if they met the following criteria: (a) consistent symptom patterns following gluten exposure on at least two separate occasions, (b) symptom onset within 24 h of consuming a gluten-containing meal, (c) complete resolution of symptoms within 72 h. The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Marche, section AOU delle Marche (Ancona, Italy, ID 220059, approved 8th August 2023).

2.2 Survey participants

This online survey involved children/adolescents (age <18 years old) with a confirmed CeD diagnosis according to the ESPGHAN guidelines (15). Participants were asked about the occurrence of symptoms that manifested within 24 h following a documented incident of unintentional gluten consumption. The list of symptoms included abdominal pain, diarrhea, vomiting, headache, fatigue, nausea, constipation, urticaria, aphthous stomatitis and arthropathy. In symptomatic patients the timing, duration and severity of symptoms, as well as the setting in which the contamination occurred, were asked.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR) and compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05. All analyses were performed using the R software (version 4.3.3).

3 Results

3.1 Study population

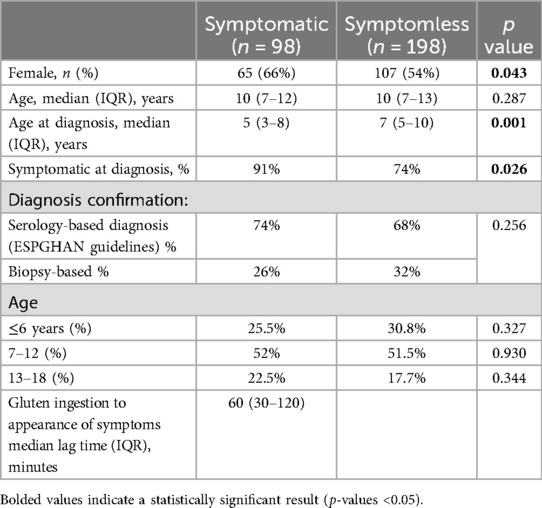

A total of 422 eligible patients were invited to participate in the study, and 296 of them completed the online survey (70%). Of these, 113 participants reported experiencing symptoms after gluten ingestion. However, following a structured follow-up with a trained dietitian to verify the timing, pattern, and resolution of symptoms, 15 participants did not fulfill the predefined criteria for a clear positive reaction to inadvertent gluten exposure. Ultimately, 98 participants (33.1%) (herein defined as “symptomatic”) reported experiencing symptoms after consuming gluten-contaminated meals. Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparative analysis of clinical and demographic features of symptomatic and asymptomatic celiac disease patients.

Female participants were more likely to report experiencing symptoms (66%) after the ingestion of contaminating gluten. The group of patients who reported symptoms differed from the asymptomatic group in the timing of their CeD diagnosis and symptoms at diagnosis. No significant differences were found among different age groups.

3.2 Symptom profile

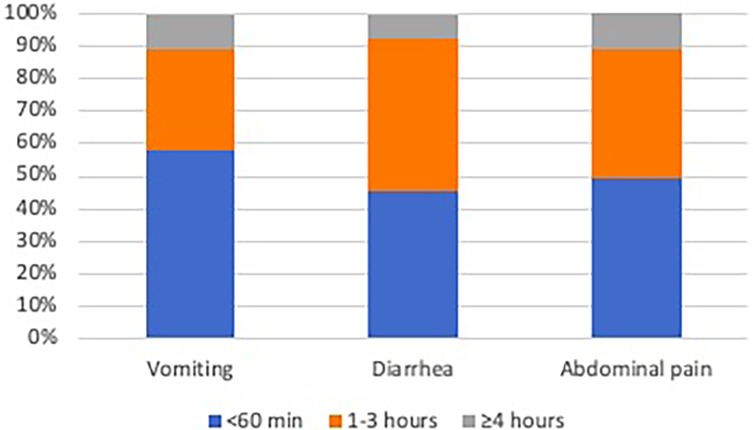

The most prevalent symptoms were abdominal pain (56/98, 57.1%), followed by diarrhea (42/98, 42.9%), vomiting (31/98, 31.6%), headache (12/98, 12.2%), fatigue (14/98, 14.2%), nausea (7/98, 7.1%), constipation (7/98, 7.1%), urticaria (7/98, 7.1%), aphthous stomatitis (5/98, 5.1%) and arthropathy (5/98, 5.1%). The majority (>90%) of patients who experienced adverse effects reported that the symptoms emerged within a brief timeframe of less than 3 h (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cumulative frequency of the onset timing of the three most commonly reported symptoms (vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain).

Among the symptomatic participants, 63% (95% CI: 47.55–76.79) reported experiencing the same symptoms they had prior to CeD diagnosis and the initiation of the GFD. The most frequently reported new symptoms were gastrointestinal, such as diarrhea (58.8%), abdominal pain (47.0%), and vomiting (35.3%). Notably, 13 of the 98 symptomatic patients (13.3%) had been completely asymptomatic before diagnosis, indicating that acute reactions may occur even in children without previous clinical manifestations of CeD.

3.3 Context of gluten exposure

The reported contamination incidents most frequently occurred in external dining settings, such as restaurants (46.2%), school cafeterias (26.9%), and during international travels (7.7%). Nonetheless, contamination events were not limited to external environments, as 19.2% of the cases occurred in the home setting. Further analysis of the types of foods implicated in these episodes revealed that contamination most often involved commonly consumed, high-risk items. In the majority of these episodes, the foods were believed by caregivers to be gluten-free at the time of consumption. Often, they were either purchased as labeled gluten-free products (e.g., certified gluten-free ice cream) or prepared in settings where caregivers had received assurances about gluten-free preparation, such as restaurants or social events. All of these food types were reported at similar frequencies (25%).

4 Discussion

This study highlights the high frequency of symptoms experienced by children with CeD on treatment with the GFD following unintentional gluten exposure, predominantly manifesting as gastrointestinal disturbances such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting. These symptoms usually manifest abruptly, may be severe but tend to disappear spontaneously within hours or a few days. Interestingly they can present also in children who have been symptomless before starting treatment with the GFD. This finding suggests that acute reactions can occur regardless of pre-diagnosis symptom profile.

Our findings are consistent with other studies evaluating symptoms after gluten challenge reporting vomiting in 8%–44% and nausea in 13%–61% of the patients (15). A survey conducted by Silvester et al. (16) found a higher prevalence of symptomatic patients after suspected gluten exposure compared to the findings in the current study. This discrepancy may be attributed to population differences. Specifically, the adult population in Silvester's study may have experienced higher exposure rates due to less stringent supervision compared to the pediatric population in the current study, where parents or caregivers likely ensure greater dietary vigilance and reduce the likelihood of gluten contamination.

As expected, patients who were symptomatic at diagnosis and those diagnosed at an earlier age appeared more likely to experience symptoms following inadvertent gluten exposure. This may be due to the heightened mucosal sensitivity and immunological responses in those with more severe or long-standing disease.

The context of symptom onset is also of considerable importance. The high proportion of patients reporting symptoms when dining outside the home underscores the challenges faced by individuals with CeD in strictly adhering to a GFD (13, 14). This is particularly problematic in settings where they lack direct control over food preparation and ingredients. Interestingly, a study by Monzani et al. (17) found that one-third of survey respondents experienced improved adherence to the GFD during COVID lockdown measures, especially among those with previously poorer disease control. This suggests that the opportunity to avoid potential sources of gluten contamination and increased use of naturally gluten-free products contribute to better dietary adherence and symptom management in this patient population. Current methods for monitoring GFD adherence, such as dietary questionnaires, celiac serology, or clinical symptoms, are not sensitive enough to detect occasional dietary transgression (18). Novel non-invasive biomarkers such as gluten immunogenic peptides (GIP), while looking promising for assessing gluten ingestion, fall short of reliably capturing all meaningful exposures and comprehensively monitor adherence to a GFD (19).

While the reported symptoms may be attributable to factors other than gluten, such as FODMAPs, fructose or lactose intolerance, or the “nocebo” effect, a recent double-blind study found that patients with challenged with vital wheat gluten exhibited an elevated interleukin-2 response in 97% of participants, which correlated with the severity of nausea and vomiting, in contrast to a sham low-FODMAP challenge (20). This suggests that inadvertent gluten consumption is a key driver of the elevated immune response and associated symptoms in these individuals. Additionally, the rapid onset of symptoms within 2–3 h of gluten ingestion indicates that unintentional gluten exposure is the primary trigger for an heightened non-IgE immune response, not only in the chronic exposure scenario typical of the T cell-mediated condition, but also following an acute gluten challenge. A study by Tye-Din et al. (21) demonstrated that serum interleukin-2 levels, which were undetectable at baseline, became elevated within 4 h in 92% of patients with CeD following an acute gluten challenge. Additionally, the peak interleukin-2 concentration was correlated with the severity of symptoms, particularly nausea and vomiting. Other research has corroborated these findings, with most reactions occurring within 1 h of suspected gluten ingestion and resolving within 48 h (22). These findings are of major significance for understanding the pathophysiology of CeD, as they highlight the previously unappreciated importance of interleukin-2 together with interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 in driving the gluten-specific CD4+ T cell response responsible for the early immune events and clinical symptoms observed after gluten exposure (23). These recent insights into the acute immune response to gluten exposure highlight an evolving trend in CeD research. Traditionally, CeD has been considered a condition primarily driven by chronic immune activation. However, increasing evidence points to the presence of immediate, measurable immune responses following even minor gluten exposure, fundamentally shifting our understanding of symptom manifestation in patients with CeD (23). Future research should aim to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying these reactions and develop strategies to mitigate inadvertent gluten exposure.

A particularly noteworthy observation from our study is that 63% of symptomatic participants reported experiencing symptoms similar to those they had at the time of CeD diagnosis, while a distinct subset reported new symptom patterns following gluten re-exposure. This variation suggests a complex and individualized clinical response to gluten that may change over time. The recurrence of similar symptoms in the majority of cases likely reflects the reactivation of immune pathways previously involved in the initial disease presentation (24). However, the emergence of new symptoms in others—most commonly gastrointestinal—points to a dynamic interplay between immunological memory, dietary factors, and mucosal adaptation. One potential explanation is that ongoing low-level immune sensitization, despite mucosal healing on a strict GFD, may prime the gut for exaggerated responses upon re-exposure (25). Alternatively, shifts in gut microbiota composition, evolving dietary patterns, or partial recovery of intestinal barrier function may alter the symptomatic profile over time (26, 27). These evolving insights into the acute phase of gluten-induced symptoms have practical consequences for clinical care and research. They reinforce the concept that acute responses to gluten are multifaceted and patient-specific, which has important implications for clinical follow-up. It also highlights the need for individualized dietary counseling and symptom tracking, particularly for patients who develop novel symptoms post-diagnosis.

The retrospective design and reliance on self-reported data in this study may have led to potential recall bias. Additionally, the researchers did not independently confirm the reported instances of gluten contamination. However, the responses were validated by a dietitian, and strict criteria were used to determine a positive reaction. Furthermore, the relatively large sample size and real-world referral context help to mitigate these limitations, as this type of information is commonly encountered by clinicians during their interactions with patients. Most previous studies exploring symptoms in response to gluten exposure have focused on controlled gluten challenges, but we know that the specific type of grain consumed, and the food processing methods can also influence the resulting symptom profiles. Therefore, the variable nature of the inadvertent gluten exposures encountered in real life may yield symptom patterns that differ from those observed in the controlled challenge settings.

5 Conclusion

This study offers valuable insights into the frequency and nature of symptomatic responses experienced by children and adolescents with CeD following an acute gluten exposure. The findings in symptomatic patients highlight the high prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, and vomiting, within this patient population. The reactions are acute, usually occurring within 1–3 h after ingestion, with the most suspected settings of contamination being school cafeterias and dining outside the home. These results emphasize the critical need for continued research and development of effective tools to monitor and manage inadvertent gluten intake, in order to improve the quality of life of individuals living with CeD.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Marche, section AOU delle Marche. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

DP: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Investigation. DD: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Writing – original draft. CM: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SR: Writing – review & editing. MA: Writing – review & editing. SG: Writing – review & editing. CC: Validation, Supervision, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. EL: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

CC reports personal fees for consultancy for Dr. Schar Food.

The remainingauthors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Catassi C, Verdú EF, Bai JC, Lionetti E. Coeliac disease. Lancet. (2022) 399:2413–26. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00794-2

2. Şahin Y. Celiac disease in children: a review of the literature. World J Clin Pediatr. (2021) 10:53–71. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v10.i4.53

3. Ramakrishna B, Makharia G, Chetri K, Dutta S, Mathur P, Ahuja V, et al. Prevalence of adult celiac disease in India: regional variations and associations. Am J Gastroenterol. (2016) 111:115–23. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.398

4. Levinson-Castiel R, Eliakim R, Shinar E, Perets T-T, Layfer O, Levhar N, et al. Rising prevalence of celiac disease is not universal and repeated testing is needed for population screening. United European Gastroenterol J. (2018) 7:412–8. doi: 10.1177/2050640618818227

5. Lebwohl B, Rubio–Tapia A. Epidemiology, presentation, and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. (2020) 160:63–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.06.098

6. Aljada B, Zohni A, El-Matary W. The gluten-free diet for celiac disease and beyond. Nutrients. (2021) 13:3993. doi: 10.3390/nu13113993

7. Leonard MM, Weir DC, DeGroote M, Mitchell PD, Singh P, Silvester JA, et al. Value of IgA tTG in predicting mucosal recovery in children with celiac disease on a gluten-free diet. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2016) 64:286–91. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000001460

8. Hujoel IA, Hujoel MLA, Choung RS, Murray JA. Symptom outcomes of celiac disease in those on a gluten-free diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. (2023) 58:781–8. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000001946

9. Wieser H, Segura V, Ruiz-Carnicer Á, Sousa C, Comino I. Food safety and cross-contamination of gluten-free products: a narrative review. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2244. doi: 10.3390/nu13072244

10. Hall N, Rubin GP, Charnock A. Intentional and inadvertent non-adherence in adult coeliac disease. A cross-sectional survey. Appetite. (2013) 68:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.04.016

11. Monachesi C, Verma AK, Catassi G, Galeazzi T, Franceschini E, Perticaroli V, et al. Quantification of accidental gluten contamination in the diet of children with treated celiac disease. Nutrients. (2021) 13:190. doi: 10.3390/nu13010190

12. Rodrigues M, Yonamine GH, Satiro CAF. Rate and determinants of non-adherence to a gluten-free diet and nutritional status assessment in children and adolescents with celiac disease in a tertiary Brazilian referral center: a cross-sectional and retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. (2018) 18:15. doi: 10.1186/s12876-018-0740-z

13. Costantino A, Aversano GM, Lasagni G, Smania V, Doneda L, Vecchi M, et al. Diagnostic management of patients reporting symptoms after wheat ingestion. Front Nutr. (2022) 9:1007007. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.1007007

14. Leonard MM, Cureton P, Fasano A. Indications and use of the gluten contamination elimination diet for patients with non-responsive celiac disease. Nutrients. (2017) 9:1129. doi: 10.3390/nu9101129

15. Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Kurppa K, Mearin ML, Ribes-Koninckx C, et al. European society paediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2019) 70:141–56. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000002497

16. Ahonen I, Laurikka P, Koskimaa S, Huhtala H, Lindfors K, Kaukinen K, et al. Prevalence of vomiting and nausea and associated factors after chronic and acute gluten exposure in celiac disease. BMC Gastroenterol. (2023) 23:301. doi: 10.1186/s12876-023-02934-w

17. Monzani A, Lionetti E, Felici E, Fransos L, Azzolina D, Rabbone I, et al. Adherence to the gluten-free diet during the lockdown for COVID-19 pandemic: a web-based survey of Italian subjects with celiac disease. Nutrients. (2020) 12:3467. doi: 10.3390/nu12113467

18. Wieser H, Ruiz-Carnicer Á, Segura V, Comino I, Sousa C. Challenges of monitoring the gluten-free diet adherence in the management and follow-up of patients with celiac disease. Nutrients. (2021) 13:2274. doi: 10.3390/nu13072274

19. Monachesi C, Catassi G, Catassi C. The use of urine peptidomics to define dietary gluten peptides from patients with celiac disease and the clinical relevance. Expert Rev Proteomics. (2023) 20:281–90. doi: 10.1080/14789450.2023.2270775

20. Daveson AJM, Tye-Din JA, Goel G, Goldstein KE, Hand HL, Neff KD, et al. Masked bolus gluten challenge low in FODMAPs implicates nausea and vomiting as key symptoms associated with immune activation in treated coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 51:244–52. doi: 10.1111/apt.15551

21. Tye-Din JA, Daveson AJM, Ee HC, Goel G, MacDougall JA, Acaster S, et al. Elevated serum interleukin-2 after gluten correlates with symptoms and is a potential diagnostic biomarker for coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 50:901–10. doi: 10.1111/apt.15477

22. Silvester JA, Graff LA, Rigaux L, Walker JR, Duerksen DR. Symptomatic suspected gluten exposure is common among patients with coeliac disease on a gluten-free diet. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. (2016) 44:612–9. doi: 10.1111/apt.13725

23. Goel G, Tye-Din JA, Qiao S, Russell AK, Mayassi T, Ciszewski C, et al. Cytokine release and gastrointestinal symptoms after gluten challenge in celiac disease. Sci Adv. (2019) 5:eaaw7756. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaw7756

24. Anderson RP. Innate and adaptive immunity in celiac disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. (2020) 36(6):470–8. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000672

25. Mandile R, Maglio M, Mosca C, Marano A, Discepolo V, Troncone R, et al. Mucosal healing in celiac disease: villous architecture and immunohistochemical features in children on a long-term gluten-free diet. Nutrients. (2022) 14:3696. doi: 10.3390/nu14183696

26. Olshan KL, Leonard MM, Serena G, Zomorrodi AR, Fasano A. Gut microbiota in celiac disease: microbes, metabolites, pathways and therapeutics. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. (2020) 16(11):1075–92. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2021.1840354

Keywords: celiac disease, gluten-free diet, gluten exposure, gastrointestinal symptoms, gluten contamination

Citation: Pjetraj D, Damiani D, Monachesi C, Ricci S, Ascani M, Gatti S, Catassi C and Lionetti E (2025) Prevalence of acute reactions to gluten contamination of the diet in children with celiac disease. Front. Pediatr. 13:1635944. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1635944

Received: 27 May 2025; Accepted: 22 August 2025;

Published: 10 September 2025.

Edited by:

Nafiye Urganci, Şişli Hamidiye Etfal Education and Research Hospital, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Yasin Sahin, Gaziantep Islam Science and Technology University, TürkiyeTuğba Önalan, Türkiye Hastanesi, Türkiye

Copyright: © 2025 Pjetraj, Damiani, Monachesi, Ricci, Ascani, Gatti, Catassi and Lionetti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carlo Catassi, Yy5jYXRhc3NpQHVuaXZwbS5pdA==

Dorina Pjetraj

Dorina Pjetraj Denise Damiani1

Denise Damiani1 Carlo Catassi

Carlo Catassi