- 1Division of Neonatology, Department of Paediatrics, Willem-Alexander Children’s Hospital, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, Netherlands

- 2The Ritchie Centre, Hudson Institute of Medical Research, Clayton, VIC, Australia

- 3Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

- 4Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

- 5Athena Institute, VU University, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 6Department of Paediatrics, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Rationale: During pregnancy, prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is released from the placenta and circulates in relatively high concentrations in the fetus. As PGE2 suppresses breathing, PGE2 concentrations must decrease after birth, but the timing and mechanisms behind this decrease are unknown. We hypothesised that both umbilical cord clamping and lung aeration contribute to the reduction in PGE2 concentrations after birth.

Materials and methods: Instrumented premature lambs (138–141 days gestation) were randomised to receive either physiological-based cord clamping (PBCC; cord clamping after ventilation onset; n = 5) or immediate cord clamping (ICC; before ventilation onset; n = 6). PGE2 concentrations were measured in pulmonary and carotid arterial blood 30 s after ventilation onset, after lung aeration and 30 s after cord clamping. All PGE2 data are expressed relative to fetal PGE2 concentrations.

Results: Relative to fetal concentrations, ventilation onset decreased PGE2 concentrations in the carotid (p = 0.036) and pulmonary arteries (p = 0.052) in PBCC lambs, whereas cord clamping had no further additional effect on PGE2 concentrations in these lambs. In ICC lambs, cord clamping decreased PGE2 concentrations, relative to fetal concentrations, in both the carotid (p = 0.001) and pulmonary arteries (p < 0.001). Ventilation onset further decreased PGE2 concentrations in both the carotid (p = 0.002) and pulmonary arteries (p = 0.014).

Conclusion: Both umbilical cord clamping and ventilation onset independently decrease PGE2 concentrations immediately after birth, which may enhance breathing activity, although the effect of cord clamping is reduced by ventilation onset.

Introduction

Lung aeration at birth triggers the cardiopulmonary changes that characterise the transition of a fetus into a neonate and is largely achieved by hydrostatic pressure gradients generated by spontaneous breathing or positive pressure inflations (1). Lung aeration not only initiates the onset of pulmonary gas exchange, but also stimulates a large decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance (2). The resulting large increase in pulmonary blood flow (PBF) plays a vital role in sustaining cardiac output after birth by taking over the role of supplying preload for the left ventricle following umbilical cord clamping (hereafter cord clamping) (3).

Although non-invasive respiratory support is now the preferred approach for supporting premature infants at birth (4), recent studies in both animals and humans have shown that the success of this approach is dependent upon the presence of spontaneous breathing (5, 6). This is because the larynx actively adducts during apnoea, thereby sealing the airways and obstructing non-invasive respiratory support and only opens during spontaneous breathing (5, 6). Thus, the success of non-invasive ventilation after birth relies heavily on stimulating spontaneous breathing, while avoiding factors that may inhibit breathing. These factors involve transient hypoxia, antenatal inflammation, the infant's arousal state and circulating mediators that can inhibit breathing (4), which include prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and adenosine (7, 8). Both hypoxia and inflammation increase production of prostaglandins (PGs), particularly PGE2 (8–11), which inhibits breathing by direct action on the brainstem. PGE2 is thought to bind to receptors and alter the excitability of nerve cells responsible for the central pattern generator for breathing by hyperpolarising cell membranes and thereby lowering neuronal firing rates (12). Indeed, PGE2 is thought to lower phrenic nerve output, as inhibiting PGE2 production with indomethacin increases peak phrenic nerve activity in newborn piglets (13).

In utero, PGE2 is produced and released by the placenta, circulates in the fetus in relatively high concentrations, and plays a role in the episodic nature of fetal breathing movements (FBMs) (14, 15). Hours-to-days after birth, circulating PGE2 concentrations decrease significantly and may contribute to the onset of continuous spontaneous breathing in the newborn (16–18). However, the relationship between breathing activity and PGE2 concentrations is complex, as FBMs occur in utero and continuous breathing can commence after birth even when PGE2 concentrations are high (19). While the decrease in circulating PGE2 appears to be associated with cord clamping, which removes access to the main source of PGE2 production (i.e., the placenta) (20), the increase in PBF associated with lung aeration may also explain this decrease (21). The lung is the primary site of prostaglandin metabolism after birth, because it contains a high expression of 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) (22), the rate-limiting step for prostaglandin metabolism, which converts PGE2 into the stable prostaglandin E metabolite (PGEM) (23). Therefore, the redirection of right ventricular output through the lungs, following a decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance, would be expected to markedly increase prostaglandin metabolism and reduce circulating PGE2 concentrations (2, 16). However, as circulating PGE2 concentrations must reflect a balance between production vs. metabolism, the factors regulating circulating PGE2 concentrations after birth are unclear (16, 17, 24). Accordingly, the objective of this study was to investigate how circulating PGE2 concentrations change in response to cord clamping and lung aeration (either before or after cord clamping) in the immediate newborn period.

Material and methods

Ethical approval

All animal procedures were approved by the Monash Medical Centre Animal Ethics Committee (MMCA 2019/30) and were conducted as stipulated by the National Health and Medical Research Council code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes (25). Methodological reporting is per the relevant ARRIVE guidelines (26).

Experimental protocol

Blood samples described in this study were collected from premature lambs included in a separate study (27), with all samples being collected 30 min before the onset of that study. This was designed to minimise the number of animals subjected to experimental procedures. As such, methods for the animal preparation have been described previously (27) and will be only described briefly here.

Twin pregnant ewes (138–141 days of gestation) were initially anaesthetised (Pentothal, i.v. 20 mg/kg: Jurox, New South Wales, Australia) and intubated, before anaesthesia was maintained with inhaled isoflurane (Isoflow, 1.5%–2.5%, Abbott Pty. Ltd., New South Wales, Australia) in air/oxygen mixture (30% oxygen). Ewes were monitored regularly (heart rate, oxygenation, expired CO2 and absent corneal reflex) to ensure adequate anaesthesia and maternal wellbeing. Each fetus was instrumented with catheters (internal diameter: 0.86 mm, external diameter: 1.52 mm, Dural Plastic Inc., New South Wales, Australia) in the right carotid and left pulmonary arteries (blood samples) and right jugular vein (anaesthesia drug administration). Transonic blood flow probes were placed around the left carotid (3 mm, Transonic System, Ithaca, NY) and pulmonary (4 mm, Transonic System, Ithaca, NY) arteries. Lambs were intubated (4 mm cuffed endotracheal tube) and their body temperatures were measured using a rectal temperature probe to correct their arterial blood gas measurements. All physiological measurements and ventilation parameters were digitally recorded using a data acquisition system running Labchart v8 software (Powerlab; ADInstruments, New South Wales, Australia).

Delivery and ventilation protocol

Following delivery, lambs were sedated (Alfaxane 10 mg/mL, 5 mL/h; Jurox New Zealand Pty. Ltd., New Zealand). Anaesthesia in the lamb was maintained using alfaloxone diluted in 5% glucose (Alfaxan, 5–15 mL/kg/h; Jurox New Zealand Pty. Ltd., New Zealand). Lambs were subsequently randomised to receive either physiological-based cord clamping (PBCC; n = 5) or immediate cord clamping (ICC; n = 6) to separate the effects of cord clamping and ventilation onset on circulating PGE2 concentrations. PBCC lambs were mechanically ventilated using air until their lungs were aerated before the umbilical cord was clamped. Lung aeration was defined by an increase in PBF that resulted in an absence of retrograde flow (i.e., blood flow out of the lungs) during diastole (3–5 min after ventilation onset). Lambs randomised to ICC (ICC lambs) had their cords clamped prior to the onset of ventilation.

Intermittent positive pressure ventilation was set in volume-guaranteed mode with a tidal volume of 7 mL/kg estimated body weight (Babylog 8000 Plus, Dräger, Germany), a respiratory rate of 60 breaths/min (0.4/0.6 s, Ti/Te), maximum peak inflation pressures of 35 cmH2O, a positive end-expiratory pressure of 5 cmH2O and, following cord clamping, oxygen was given as needed based on the lamb's oxygen levels.

Blood sample protocol

Blood samples of 1 mL were collected from the pulmonary artery, carotid artery and umbilical vein for blood gas analyses and measurements of PGE2 concentrations; indomethacin was added to the blood collection tubes to prevent post-collection prostaglandin synthesis. In PBCC lambs, blood samples were collected while the fetus was in utero, 30 s after ventilation onset, directly after lung aeration (indicated by the increase in PBF and absence of retrograde flow) and 30 s after cord clamping. In ICC lambs, blood samples were collected while the fetus was in utero, 30 s after cord clamping, 30 s after ventilation onset and after lung aeration. A protocol amendment was made halfway through the experiment to also collect a blood sample from the umbilical vein after cord clamping. This was performed in 6 lambs.

Postmortem protocol

Ewes were euthanised with an intravenous sodium pentobarbitone solution (>100 mg/kg; Lethabarb, Virbac Pty. Ltd., New South Wales, Australia) after both twins were delivered. Newborn lambs were also euthanised with intravenous sodium pentobarbitone solution (>100 mg/kg) following experimental procedures. In addition, postmortem analyses were performed to record body and organ weights. The right lung of each lamb was fixed and analysed to demonstrate the presence of 15-PGDH.

Physiological recording analysis

PBF and carotid artery blood flow were continuously measured and recorded using LabChart throughout the delivery and ventilation periods.

PGE2 concentration analysis

The blood samples were analysed to determine the primary outcome of circulating PGE2 concentrations (pg/mL) using a commercially available bovine monoclonal PGE2 ELISA kit (cat# 514010, Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, United States). The analysis was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, with the methodology described in Supplementary File S1.

Prostaglanin E metabolite (PGEM) concentration analysis

Circulating concentrations of PGEM were measured using a commercially available monoclonal ELISA kit (cat# 514531, Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, United States), according to manufacturer's instructions (described in Supplementary File S1).

15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH) analysis

At postmortem examination, the right lungs of all lambs were pressure fixed (20 cmH2O) with formalin. Following fixation, the lungs were cut into 5 mm transverse sections, before the slices were further subdivided with different lung sections selected at random. The randomly selected lung tissue was paraffin-embedded and stained for the presence of 15-PGDH; as specified in Supplementary File S1. The 15-PGDH analysis was displayed in Supplementary File S2 (Figure S3).

Statistical analysis

All continuous data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Binary data were presented as n (%). Missing data were noted in the results section. All PGE2 and PGEM data were described and graphically displayed in Supplementary File S2 (Table S1, Figure S2). PGE2 and PGEM concentrations in the fetal umbilical vein were compared with concentrations in the carotid artery and pulmonary artery using a Paired-Samples T-test in 6 lambs. As basal fetal PGE2 concentrations were quite variable between lambs [Supplementary File S2 (Figure S3)], carotid and pulmonary artery PGE2 concentrations were expressed as a percentage of fetal PGE2 concentrations measured in each lamb. This ensured that the changes associated with ventilation and cord clamping were not obscured by the large variability in basal values between lambs. The PGE2 data were then transformed (square root) and analysed over time with a One-Way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Differences at each time point within each group (PBCC and ICC) were analysed using post-hoc Fisher's least significant differences tests. The results of the post-hoc tests are depicted in the text results and Figure 3. In addition, the change in PGE2 concentrations in response to ventilation (combined ventilation onset and lung aeration samples) and cord clamping were also separately analysed with Paired-Samples t-tests for both PBCC and ICC lambs. This analysis was performed to evaluate the specific effects of cord clamping and ventilation of the lung on PGE2 concentrations, irrespective of whether cord clamping or ventilation occurred first. PGEM concentrations were analysed over time with a One-Way Repeated Measures Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Differences between specific treatments within each group were also analysed with post-hoc Fisher's least significant differences tests. The outcomes of the PGEM analyses were reported in the text results. The researchers could not be blinded during sample collection and analysis due to the nature of the study.

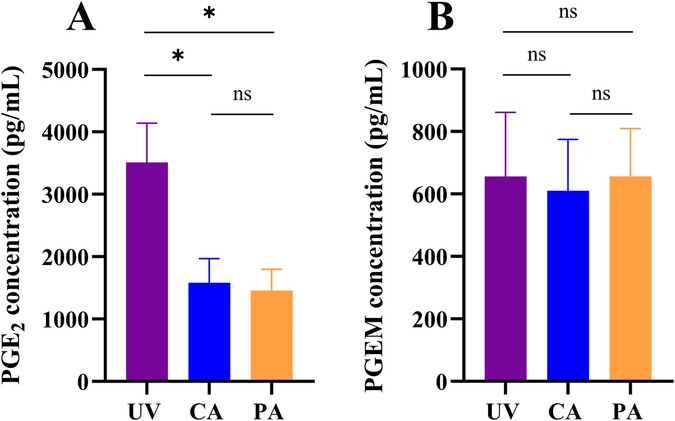

Figure 1. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and prostaglandin E metabolite (PGEM) concentrations in the fetal circulation.PGE2 (A) and PGEM (B) concentrations measured in the umbilical vein (UV), carotid artery (CA) and pulmonary artery (PA) in n = 6 fetal sheep. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. * represents a p-value ≤0.05; ns represents a p-value >0.05.

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics V.29.0 (IBM Software, Chicago, Illinois, USA, 2022), and data were graphed using GraphPad Prism (v.9) and Adobe Illustrator 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, California, USA, 2023). A two-sided p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Animal inclusion

A total of 13 lambs (from seven ewes) were instrumented, but two lambs could not be included due to surgical complications prior to initiation of the experiments. The remaining 11 lambs were randomised to PBCC (n = 5) or ICC (n = 6) groups. Samples for PGE2 and PGEM concentrations were available from four PBCC lambs and six ICC lambs.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics are displayed in Table 1. Baseline characteristics were similar between PBCC and ICC lambs. The majority of both PBCC (80%) and ICC lambs (83%) were male with similar body and lung weights between groups (Table 1). Fetal arterial blood gas parameters were similar between PBCC and ICC lambs (Table 1).

Blood sampling

A reference blood sample was withdrawn prior to starting the protocol (fetal sample), followed by blood samples taken 30 ± 7 s after cord clamping and 33 ± 6 s after ventilation onset. A final, “lung aeration” sample was collected at 199 ± 25 s after ventilation onset, which was the average time it took for PBF to increase and abolish retrograde flow (lung aeration sample). Blood flow measurements are displayed in Supplementary File S2 (Figure S1).

Fetal PGE2 and PGEM concentrations

In utero, PGE2 concentrations in the umbilical vein were significantly higher than in the fetal carotid (p = 0.020; Figure 1A) and pulmonary arteries (p = 0.013; Figure 1A) of all lambs. In the fetal sample, PGE2 concentrations were also higher in the carotid artery compared to the pulmonary artery in 5/6 lambs (p = 0.080; Figure 1A). In contrast, PGEM concentrations in the umbilical vein were similar to the concentrations measured in the carotid (656 ± 502 vs. 611 ± 401 pg/mL, p = 0.495; Figure 1B) and pulmonary arteries (656 ± 502 vs. 656 ± 377 pg/mL, p = 0.999; Figure 1B). PGEM concentrations in the fetal carotid and pulmonary artery were also similar (611 ± 401 vs. 656 ± 377, p = 0.678; Figure 1B).

Figure 2. Prostaglandin (PGE2) changes in response to cord clamping, ventilation onset and lung aeration.PGE2 concentrations, expressed as a percentage of fetal concentrations, in lambs that received physiological-based cord clamping (PBCC, n = 4; A and C) or immediate cord clamping (ICC, n = 6; B and D) at birth. Concentrations were measured in both the carotid (A and B) and pulmonary (C and D) artery. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean and were analysed by a One-Way Repeated Measures ANOVA followed by post-hoc Fisher's least square differences test between each consecutive timepoint. * represents a p-value ≤0.05; ns represents a p-value >0.05.

Changes in PGE2 concentrations

PGE2 concentrations after birth are displayed in Supplementary File S2 (Figure S2, S3), providing absolute values for reference. For analyses, PGE2 concentrations relative to fetal concentrations are displayed in Figure 2. In PBCC lambs, ventilation onset significantly reduced PGE2 concentrations, expressed relative to fetal concentrations, in both the carotid (100 ± 0 vs. 82 ± 4%, p = 0.036; Figure 2A) and pulmonary (100 ± 0 vs. 66 ± 9%, p = 0.052; Figure 2C) arteries. While PGE2 concentrations in the carotid artery did not change following lung aeration and cord clamping, PGE2 concentrations in the pulmonary artery significantly increased once the lungs were aerated (66 ± 9 vs. 86 ± 8%, p = 0.012; Figure 2C).

Figure 3. Effect of ventilation onset, lung aeration and cord clamping on prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) concentrations in the carotid artery.PGE2 concentrations in the carotid artery (CA) expressed as the percentage of the sample taken before (A) ventilation and lung aeration (vent) and (B) before cord clamping (cc) in both physiological-based cord clamping (PBCC, n = 4; orange closed bars) and immediate cord clamping (ICC, n = 6; orange open bars) lambs. “Before vent” samples consisted of the fetal sample in PBCC lambs or the 30 s after cord clamping sample in ICC lambs. “After vent” sample consisted of the combined mean of the ventilation onset and lung aeration sample in PBCC or ICC lambs. “Before cc” samples consisted of the lung aeration sample in PBCC lambs or the fetal sample in ICC lambs. “After cc” samples consisted of the 30 s after cord clamping sample in PBCC or ICC lambs. Data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. * represents a p-value ≤0.05; ns represents a p-value >0.05.

In ICC lambs, both cord clamping (100 ± 0 vs. 80 ± 3%, p = 0.001; Figure 2B) and ventilation onset (80 ± 3 vs. 67 ± 1%, p = 0.002; Figure 2B) decreased PGE2 concentrations, expressed relative to fetal concentrations, in the carotid artery. Similarly, PGE2 concentrations in the pulmonary artery also decreased after cord clamping (100 ± 0 vs. 80 ± 1%, p < 0.001; Figure 2D) and ventilation onset (80 ± 1 vs. 71 ± 3%, p = 0.014). PGE2 concentrations did not significantly change in the carotid or pulmonary arteries following lung aeration.

Effect of pulmonary ventilation and cord clamping

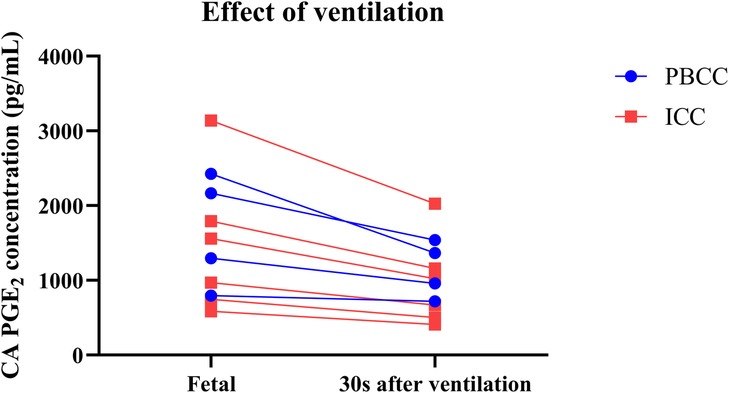

In PBCC lambs, ventilation of the lung (combined mean of ventilation onset and lung aeration samples from the carotid artery) significantly reduced PGE2 concentrations by 24 ± 4% (p = 0.012; Figure 3A) compared to fetal concentrations. However, PGE2 concentrations were not decreased further in response to cord clamping (lung aeration vs. cord clamping %; 100 ± 0 vs. 103% ± 3%, p = 0.314; Figure 3B). The effect of ventilation on PGE2 concentrations in individual lambs is displayed in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) concentrations before and after ventilation onset.PGE2 concentrations in the carotid artery (CA) of lambs that received physiological-based cord clamping (PBCC, n = 4; blue) or immediate cord clamping (ICC, n = 6; red) immediately before and 30 s after ventilation onset.

In ICC lambs, cord clamping reduced PGE2 concentrations by 20% ± 3% relative to fetal concentrations (p = 0.001; Figure 3A) and subsequent ventilation of the lung (combined mean of ventilation onset and lung aeration samples) from the carotid artery also significantly reduced PGE2 concentrations by 33% ± 3% (p < 0.001; Figure 3B).

Changes in PGEM concentrations

In PBCC lambs, PGEM concentrations in the carotid and pulmonary arteries, displayed in Supplementary File S2 (Figure S2), did not significantly change in response to ventilation onset (carotid artery: p = 0.265; pulmonary artery: p = 0.925), lung aeration (p = 0.334; p = 0.829), and cord clamping (p = 0.460; p = 0.233). Similarly, in ICC lambs, PGEM concentrations in the carotid and pulmonary artery did not change in response to cord clamping (p = 0.444; p = 0.771), ventilation onset (p = 0.362; p = 0.219), and lung aeration (p = 0.420; p = 0.165) [Supplemental file S2 (Figure S2)].

Discussion

This study demonstrates that circulating prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) concentrations, but not its metabolite (PGEM), decrease during the fetal-to-neonatal transition at birth, largely in response to ventilation onset and cord clamping. To separate the independent effects of cord clamping and ventilation onset on circulating PGE2 concentrations, blood samples were collected following both PBCC (ventilation onset prior to cord clamping) and ICC (cord clamping prior to ventilation onset) in premature lambs. During PBCC, it was found that circulating PGE2 concentrations in the carotid artery decreased in response to ventilation onset and lung aeration compared to fetal concentrations, but not did not decrease further in response to cord clamping. In contrast, cord clamping prior to ventilation onset significantly decreased PGE2 concentrations and PGE2 concentrations were further reduced by ventilating and aerating the lung. Therefore, while the effects of cord clamping depend on its timing, ventilation onset and subsequent lung aeration consistently decrease PGE2 concentrations, which would be expected to promote spontaneous breathing after birth.

Circulating PGE2 concentrations are much higher in the fetus than in the neonate (16, 17, 28), likely due to high production rates and the release of PGE2 into the fetal circulation by the placenta. This explains the much higher PGE2 concentrations in the umbilical vein compared with other fetal vessels (14). Higher circulating PGE2 concentrations in the fetus are also thought to result from reduced prostaglandin metabolism rates. This is due to redirection of right ventricular output away from the fetal lungs (and through the ductus arteriosus), the primary site of prostaglandin metabolism in the adult (23). As a result, in utero, PGE2 is thought to act as a circulating hormone that has a variety of actions including regulating FBMs, organ maturation, thermogenesis, patency of the ductus arteriosus, glucose homeostasis, stress hormone concentrations, and may even contribute to the onset of labour (29). Circulating PGE2 concentrations also increase in response to fetal hypoxia (30, 31) and although it is not clear what role they play, the inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis during fetal hypoxia causes severe acidaemia and fetal demise (32). Similarly, PGE2 also plays an important role in the fetal response to intrauterine inflammation, particularly in the lung (33). However, relevant to this study is PGE2's well-established inhibitory effect on FBMs, which could restrict the onset of continuous breathing at birth, if postnatal concentrations remained elevated (29). As the onset of continuous breathing is critical for postnatal survival, exposure of the newborn to inhibitory factors, such as hypoxia and elevated PGE2 concentrations, should be avoided or minimised. Based on our findings, this can simply be achieved by aerating the lungs before cord clamping, which would be expected to increase both oxygenation and decrease PGE2 concentrations by increasing its metabolism. While clamping the cord will also decrease PGE2 supply, this provides no additional benefit with regard to reducing PGE2 concentrations in the immediate newborn period.

In contrast to the fetus, PGE2 is thought to act in a more paracrine fashion in neonates and adults, largely due to the highly efficient metabolism of PGE2 as it passes through the lungs (16, 17, 23, 24, 34). The current study found that PGE2 concentrations decreased in the carotid and pulmonary arteries following cord clamping in ICC lambs, although this effect of cord clamping was masked if it was preceded by ventilation onset. By removing the placental source of PGE2, the decrease in PGE2 concentrations in ICC lambs is likely due to ongoing metabolism, as otherwise concentrations would remain stable. However, as PGE2 concentrations decreased immediately after cord clamping and before ventilation onset, increased metabolism by the lung could not be responsible. Instead, this most likely occurred in the liver, which is known to have high 15-PGDH levels, the enzyme largely responsible for prostaglandin metabolism (35, 36). While PGE2 concentrations decreased following cord clamping (and ventilation onset), concentrations rapidly stabilised which is indicative of ongoing production from sources other than the placenta. However, following ventilation onset in PBCC lambs, we were unable to detect a decrease in PGE2 concentrations in response to cord clamping. The disparity was presumably due to a combination of factors associated with ventilation onset. These include a reduction in umbilical venous flow associated with the onset of left-to-right ductal shunting and the redirection of left and right ventricular output through the lungs, rather than through the placenta, following lung aeration (37, 38). In addition, the increase in pulmonary venous return to the left atrium, which has lower PGE2 concentrations, likely overwhelms the high PGE2 influx of the (already reduced) umbilical venous blood flow entering via the foramen ovale. As a result, the impact of cord clamping on PGE2 concentrations was not detectable.

By aerating the lung, ventilation onset greatly increases PGE2 metabolism at birth by stimulating a large decrease in pulmonary vascular resistance, which redirects 100% of right ventricular output through the lungs. In addition, the onset of left-to right shunting through the ductus arteriosus means that a large proportion of left ventricular output will also pass through the lungs (37). As the lung is the primary site of prostaglandin metabolism in the adult/newborn (23), the huge (30-fold) increase in blood passing through the lungs explains why a rapid decrease in PGE2 concentrations following ventilation onset was observed. This result is consistent with our finding of marked 15-PGDH staining in lung tissue from these preterm newborn lambs, which is primarily found in distal, rather than proximal, airways (22). Furthermore, a reduction in umbilical venous flow may also contribute to less influx of PGE2 into the circulation of PBCC lambs following ventilation onset. It is interesting that, in ICC lambs, cord clamping decreased PGE2 concentrations, which were further decreased by ventilation onset. This result clearly demonstrates that increased PGE2 metabolism via the lung is a major contributor to the decrease in circulating PGE2 concentrations after birth, whereas the effect of cord clamping is complicated by the presence or absence of lung aeration.

Our findings confirm and extend those of other experimental studies that reported a decrease in PGE2 concentrations after birth (16, 17, 24); though concentrations were much higher in the current study and more reflective of fetal concentrations. The concentration differences are likely due to different sampling positions and sampling time points. Indeed, we measured PGE2 concentrations both before and in the first few minutes after birth, whereas other experimental studies have evaluated concentrations hours-to-days after birth, when we would expect that PGE2 clearance would be much greater (16, 17, 24). In this experiment, we chose to compare changes in PGE2 concentrations relative to fetal levels measured in the same animal, to counter the variability in PGE2 concentrations between animals [Supplementary File S2 (Figure S3)]. As circulating fetal PGE2 concentrations are known to depend on factors such as time of day, nutritional status and oxygenation level, large variations in circulating concentrations between animals are expected (14, 32). However, despite this large variability in concentrations between animals, the changes in PGE2 concentrations in response to cord clamping and ventilation onset within each animal were remarkably similar (Figure 4). Indeed, all ICC lambs reacted similarly to cord clamping and ventilation onset (Figure 4), although this variability tended to increase following lung aeration. This likely reflects the variability in the degree of lung aeration and increase in PBF between animals, which also likely explains the slightly higher variability in percentage change observed in PBCC lambs (Figures 1A,C) than ICC lambs.

In premature infants, delayed cord clamping strategies (including PBCC) can significantly reduce mortality and the need for blood transfusions compared to earlier cord clamping strategies (39, 40). As PGE2 is an inflammatory mediator known to inhibit respiratory drive (11, 41, 42) and PGE2 concentrations decrease with ventilation onset (current study), this highlights the importance of stimulating and supporting spontaneous breathing at birth when cord clamping is delayed. By stimulating and supporting spontaneous breathing, clinicians can assist in establishing lung aeration and commence a positive feedback mechanism with subsequent decreases in PGE2 concentration and promotion of spontaneous breathing (21).

As the placenta is the primary source of circulating PGE2 in the fetus, it is logical that PGE2 concentrations were higher in the carotid than pulmonary artery in 5/6 lambs. This is because umbilical venous return mostly passes through the ductus venosus and foramen ovale to directly enter the left atrium (43). As a result, like oxygen levels, PGE2 concentrations in the carotid artery should be higher than in the pulmonary artery. Interestingly, the significant increase in PGE2 concentrations in the pulmonary artery between ventilation onset and lung aeration in the PBCC lambs was probably due to the onset of left-to-right shunting through the ductus arteriosus. As the samples were collected from a catheter with its tip in the left pulmonary artery, distal to its junction with the ductus arteriosus, the large contribution of left ventricular output to PBF would be expected to increase PGE2 concentrations to similar levels as the carotid artery. It is also possible that the redirection of umbilical venous return into the right atrium, rather than through the foramen ovale, may also contribute to higher PGE2 concentrations in the pulmonary artery following ventilation onset (44). While overall fetal PGE2 metabolism must equal placental PGE2 production, otherwise concentrations would continue to increase, the difference in PGE2 concentrations in the umbilical vein and fetal arteries is likely due to dilution as it enters the fetal circulation, but could in part also be explained by hepatic metabolism, as discussed above.

It is interesting that PGEM concentrations remained relatively stable throughout the sampling protocol in both PBCC and ICC lambs, particularly as an increase in metabolism partly explains the decrease in PGE2 concentrations at birth. However, PGEM has a much longer half-life than PGE2 so PGEM concentrations are unlikely to change as rapidly as PGE2 concentrations (45). It is also unclear how quickly metabolised PGE2 re-enters the circulation as PGEM and if it takes more than a few minutes, then it is not surprising that we did not detect the contribution of metabolised PGE2 to circulating PGEM concentrations following ventilation onset.

This study is mostly limited by the small sample size as well as missing data that lower our statistical power. PGE2 concentrations in this study were elevated compared to clinical and experimental studies (16–18, 24, 28, 46), but given the consistency of PGE2 changes between animals, we consider that the relative changes accurately reflect the changes in PGE2 concentrations directly at birth.

In summary, we have shown that PGE2 concentrations change within 30 s in the carotid and pulmonary arteries of premature lambs in response to umbilical cord clamping and ventilation onset at birth, whereas PGEM concentrations do not. Ventilation onset and lung aeration likely reduce PGE2 concentrations by increasing PBF and thereby increasing PGE2 metabolism within the lung. Decreases in PGE2 concentrations associated with cord clamping are most likely due to endogenous metabolism following cessation of the supply of high PGE2 concentrations from the placenta. While ventilation onset reduced PGE2 concentrations irrespective of cord clamping timing, ventilation onset and subsequent lung aeration tended to obscure the effect of cord clamping on circulating PGE2 concentrations, likely due to the circulatory changes induced by ventilation onset.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Monash Medical Centre Animal Ethics Committee. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

TP: Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Project administration, Investigation. JD: Supervision, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Conceptualization, Validation, Formal analysis. KC: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization, Validation, Project administration, Visualization. CD: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Validation, Conceptualization. KK: Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Validation. EC: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. PR: Investigation, Project administration, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. FB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Data curation. AT: Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Methodology. TA: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. GP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. AP: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. SH: Visualization, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Supervision, Data curation, Conceptualization. ID: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization, Investigation, Visualization, Project administration, Validation, Data curation.

Funding

The authors declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This research was funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) ideas grant (APP1187580) as well as the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program. SH was supported by an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellowship (APP1154914). The stay and travel for TP were supported by the Leiden University Fund (W222147-2-50) and the Prince Bernard Culture fund (40042629).

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Olivia Martinez for assisting with data collection for the experiments and the efforts of Hui Lu for performing the immunohistochemistry data processing and analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fped.2025.1636459/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

15-PGDH, 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase; ANOVA, Analysis of variance; CA, Carotid artery; CBF, Carotid blood flow; CC, Cord clamping; FBM, Fetal breathing movement; ICC, Immediate cord clamping; PA, Pulmonary artery; PGEM, Prostaglandin E metabolite; PGE2, Prostaglandin E2; PBCC, Physiological-based cord clamping; PBF, Pulmonary blood flow; UV, Umbilical vein; Vent, Ventilation onset.

References

1. Hooper SB, Roberts C, Dekker J, Te Pas AB. Issues in cardiopulmonary transition at birth. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. (2019) 24(6):101033. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2019.101033

2. Lang JA, Pearson JT, te Pas AB, Wallace MJ, Siew ML, Kitchen MJ, et al. Ventilation/perfusion mismatch during lung aeration at birth. J Appl Physiol (1985). (2014) 117(5):535–43. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01358.2013

3. Bhatt S, Alison BJ, Wallace EM, Crossley KJ, Gill AW, Kluckow M, et al. Delaying cord clamping until ventilation onset improves cardiovascular function at birth in preterm lambs. J Physiol. (2013) 591(8):2113–26. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.250084

4. Dekker J, van Kaam AH, Roehr CC, Flemmer AW, Foglia EE, Hooper SB, et al. Stimulating and maintaining spontaneous breathing during transition of preterm infants. Pediatr Res. (2021) 90(4):722–30. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0468-7

5. Heesters V, Dekker J, Panneflek TJ, Kuypers KL, Hooper SB, Visser R, et al. The vocal cords are predominantly closed in preterm infants <30 weeks gestation during transition after birth; an observational study. Resuscitation. (2023) 194:110053. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2023.110053

6. Crawshaw JR, Kitchen MJ, Binder-Heschl C, Thio M, Wallace MJ, Kerr LT, et al. Laryngeal closure impedes non-invasive ventilation at birth. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2018) 103(2):F112–9. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-312681

7. Kitterman JA, Liggins GC, Clements JA, Tooley WH. Stimulation of breathing movements in fetal sheep by inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis. J Dev Physiol. (1979) 1(6):453–66.551120

8. Koos BJ, Mason BA, Punla O, Adinolfi AM. Hypoxic inhibition of breathing in fetal sheep: relationship to brain adenosine concentrations. J Appl Physiol (1985). (1994) 77(6):2734–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.6.2734

9. Stojanovska V, Atta J, Kelly SB, Zahra VA, Matthews-Staindl E, Nitsos I, et al. Increased prostaglandin E2 in brainstem respiratory centers is associated with inhibition of breathing movements in fetal sheep exposed to progressive systemic inflammation. Front Physiol. (2022) 13:841229. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.841229

10. Gluckman PD, Johnston BM. Lesions in the upper lateral pons abolish the hypoxic depression of breathing in unanaesthetized fetal lambs in utero. J Physiol. (1987) 382:373–83. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016372

11. Hofstetter AO, Saha S, Siljehav V, Jakobsson PJ, Herlenius E. The induced prostaglandin E2 pathway is a key regulator of the respiratory response to infection and hypoxia in neonates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2007) 104(23):9894–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611468104

12. Vitaliti G, Falsaperla R. Chorioamnionitis, inflammation and neonatal apnea: effects on preterm neonatal brainstem and on peripheral airways: chorioamnionitis and neonatal respiratory functions. Children (Basel). (2021) 8(10):917. doi: 10.3390/children8100917

13. Long WA. Prostaglandins and control of breathing in newborn piglets. J Appl Physiol (1985). (1988) 64(1):409–18. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1988.64.1.409

14. Fowden AL, Harding R, Ralph MM, Thorburn GD. The nutritional regulation of plasma prostaglandin E concentrations in the fetus and pregnant ewe during late gestation. J Physiol. (1987) 394:1–12. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016856

15. Hohimer AR, Richardson BS, Bissonnette JM, Machida CM. The effect of indomethacin on breathing movements and cerebral blood flow and metabolism in the fetal sheep. J Dev Physiol. (1985) 7(4):217–28.4045129

16. Simberg N. The metabolism of prostaglandin E2 in perinatal rabbit lungs. Prostaglandins. (1983) 26(2):275–85. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(83)90095-3

17. Jones SA, Adamson SL, Bishai I, Lees J, Engelberts D, Coceani F. Eicosanoids in third ventricular cerebrospinal fluid of fetal and newborn sheep. Am J Physiol. (1993) 264(1 Pt 2):R135–42.8381613

18. Mitchell MD, Brunt J, Bibby J, Flint AP, Anderson AB, Turnbull AC. Prostaglandins in the human umbilical circulation at birth. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. (1978) 85(2):114–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1978.tb10463.x

19. Lee DS, Choy P, Davi M, Caces R, Gibson D, Hasan SU, et al. Decrease in plasma prostaglandin E2 is not essential for the establishment of continuous breathing at birth in sheep. J Dev Physiol. (1989) 12(3):145–51.2625514

20. Adamson SL, Kuipers IM, Olson DM. Umbilical cord occlusion stimulates breathing independent of blood gases and pH. J Appl Physiol (1985). (1991) 70(4):1796–809. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.70.4.1796

21. Panneflek TJR, Kuypers K, Polglase GR, Derleth DP, Dekker J, Hooper SB, et al. The influence of chorioamnionitis on respiratory drive and spontaneous breathing of premature infants at birth: a narrative review. Eur J Pediatr. (2024) 183(6):2539–47. doi: 10.1007/s00431-024-05508-4

22. Conner CE, Kelly RW, Hume R. Regulation of prostaglandin availability in human fetal lung by differential localisation of prostaglandin H synthase-1 and prostaglandin dehydrogenase. Histochem Cell Biol. (2001) 116(4):313–9. doi: 10.1007/s004180100323

23. Piper PJ, Vane JR, Wyllie JH. Inactivation of prostaglandins by the lungs. Nature. (1970) 225(5233):600–4. doi: 10.1038/225600a0

24. Clyman RI, Mauray F, Roman C, Rudolph AM, Heymann MA. Circulating prostaglandin E2 concentrations and patent ductus arteriosus in fetal and neonatal lambs. J Pediatr. (1980) 97(3):455–61. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(80)80205-8

25. Council N. Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes. Australian Government[Abstract][Google Scholar] (2013).

26. Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: updated guidelines for reporting animal research. Br J Pharmacol. (2020) 177(16):3617–24. doi: 10.1111/bph.15193

27. Diedericks C, Crossley KJ, Davies IM, Riddington PJ, Cannata ER, Martinez OL, et al. Influence of the chest wall on respiratory function at birth in near-term lambs. J Appl Physiol (1985). (2024) 136(3):630–42. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00496.2023

28. Mitchell MD, Lucas A, Etches PC, Brunt JD, Turnbull AC. Plasma prostaglandin levels during early neonatal life following term and pre-term delivery. Prostaglandins. (1978) 16(2):319–26. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(78)90033-3

29. Thorburn GD. The placenta, PGE2 and parturition. Early Hum Dev. (1992) 29(1-3):63–73. doi: 10.1016/0378-3782(92)90059-P

30. Hooper SB, Coulter CL, Deayton JM, Harding R, Thorburn GD. Fetal endocrine responses to prolonged hypoxemia in sheep. Am J Physiol. (1990) 259(4 Pt 2):R703–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.4.R703

31. Hooper SB. Fetal metabolic responses to hypoxia. Reprod Fertil Dev. (1995) 7(3):527–38. doi: 10.1071/RD9950527

32. Hooper SB, Harding R, Deayton J, Thorburn GD. Role of prostaglandins in the metabolic responses of the fetus to hypoxia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. (1992) 166(5):1568–75. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91635-N

33. Westover AJ, Moss TJ. Effects of intrauterine infection or inflammation on fetal lung development. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2012) 39(9):824–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2012.05742.x

34. Greystoke AP, Kelly RW, Benediktsson R, Riley SC. Transfer and metabolism of prostaglandin E(2)in the dual perfused human placenta. Placenta. (2000) 21(1):109–14. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0452

35. Falkay G, Herczeg J, Sas M. Prostaglandin synthesis and metabolism in the human uterus and midtrimester fetal tissues. J Reprod Fertil. (1980) 59(2):525–9. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0590525

36. Keirse MJ, Hicks BR, Kendall JZ. Fetal and maternal metabolism of prostaglandin F2 alpha in the Guinea pig. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. (1979) 9(4):265–71. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(79)90067-4

37. Crossley KJ, Allison BJ, Polglase GR, Morley CJ, Davis PG, Hooper SB. Dynamic changes in the direction of blood flow through the ductus arteriosus at birth. J Physiol. (2009) 587(Pt 19):4695–704. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.174870

38. Blank DA, Polglase GR, Kluckow M, Gill AW, Crossley KJ, Moxham A, et al. Haemodynamic effects of umbilical cord milking in premature sheep during the neonatal transition. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2018) 103(6):F539–46. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314005

39. Seidler AL, Libesman S, Hunter KE, Barba A, Aberoumand M, Williams JG, et al. Short, medium, and long deferral of umbilical cord clamping compared with umbilical cord milking and immediate clamping at preterm birth: a systematic review and network meta-analysis with individual participant data. Lancet. (2023) 402(10418):2223–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02469-8

40. Knol R, Brouwer E, van den Akker T, DeKoninck PLJ, Onland W, Vermeulen MJ, et al. Physiological versus time based cord clamping in very preterm infants (ABC3): a parallel-group, multicentre, randomised, controlled superiority trial. Lancet Reg Health Eur. (2025) 48:101146. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2024.101146

41. Siljehav V, Olsson Hofstetter A, Jakobsson PJ, Herlenius E. mPGES-1 and prostaglandin E2: vital role in inflammation, hypoxic response, and survival. Pediatr Res. (2012) 72(5):460–7. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.119

42. Siljehav V, Hofstetter A, Leifsdóttir K, Herlenius E. Prostaglandin E2 mediates cardiorespiratory disturbances during infection in neonates. J Pediatr. (2015) 167(6):1207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.08.053

43. Marty M, Kerndt CC, Lui F. Embryology, fetal circulation. In: Shams P, Editor-in-Chief. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2024).

44. Morton SU, Brodsky D. Fetal physiology and the transition to extrauterine life. Clin Perinatol. (2016) 43(3):395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.04.001

45. Nagafuji M, Fujiyama S, Doki K, Ishii R, Okada Y, Hanaki M, et al. Assessment of blood prostaglandin E(2) metabolite levels among infants born preterm with patent ductus arteriosus: a prospective study. J Pediatr. (2025) 276:114285. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2024.114285

Keywords: prostaglandins, perinatal transition, preclinical, ventilation, cord clamping

Citation: Panneflek TJR, Dekker J, Crossley KJ, Diedericks C, Kuypers KLAM, Cannata ER, Riddington PJ, Bloem FE, Thiel AM, van den Akker T, Polglase GR, te Pas AB, Hooper SB and Davies IM (2025) Circulating prostaglandin E2 concentrations decrease at birth in premature lambs. Front. Pediatr. 13:1636459. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1636459

Received: 27 May 2025; Revised: 6 November 2025;

Accepted: 11 November 2025;

Published: 28 November 2025.

Edited by:

Hans Fuchs, University of Freiburg Medical Center, GermanyReviewed by:

Emmanuelle Motte-Signoret, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit—CHI Poissy St Germain, FranceFlorens Lohrmann, University of Freiburg Medical Center, Germany

Copyright: © 2025 Panneflek, Dekker, Crossley, Diedericks, Kuypers, Cannata, Riddington, Bloem, Thiel, van den Akker, Polglase, te Pas, Hooper and Davies. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stuart B. Hooper, c3R1YXJ0Lmhvb3BlckBtb25hc2guZWR1

Timothy J. R. Panneflek

Timothy J. R. Panneflek Janneke Dekker

Janneke Dekker Kelly J. Crossley

Kelly J. Crossley Cailin Diedericks

Cailin Diedericks Kristel L. A. M. Kuypers

Kristel L. A. M. Kuypers Ebony R. Cannata

Ebony R. Cannata Paige J. Riddington

Paige J. Riddington Femmie E. Bloem1

Femmie E. Bloem1 Alison M. Thiel

Alison M. Thiel Thomas van den Akker

Thomas van den Akker Graeme R. Polglase

Graeme R. Polglase Arjan B. te Pas

Arjan B. te Pas Stuart B. Hooper

Stuart B. Hooper Indya M. Davies

Indya M. Davies