- 1Department of Pediatric Surgery, Fujian Children’s Hospital (Fujian Branch of Shanghai Children’s Medical Center), College of Clinical Medicine for Obstetrics & Gynecology and Pediatrics, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

- 2Department of Pediatric Surgery, Fujian Maternity and Child Health Hospital, College of Clinical Medicine for Obstetrics & Gynecology and Pediatrics, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou, China

Objectives: To analyze the risk factors for postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis (HAEC) and establish a nomogram to predict the incidence of HAEC.

Methods: All patients with Hirschsprung disease who underwent definitive surgery at Fujian Provincial Children's Hospital from January 2015 to December 2023 were included in the study. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression were used to analyze the influencing factors of chylous ascites and a nomogram was established. The predictive performance of the nomogram was evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, calibration plots, and decision curve analysis (DCA) curves.

Results: Of the included 204 patients, 53 patients (25.9%) experienced postoperative HAEC. Preoperative HAEC, the type of HSCR (long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis), no-preoperative bowel preparation, and anastomotic leaks or strictures were considered important risk factors. The area under the ROC curve of the model is 0.79, the nomogram has great discriminative ability, calibration and significant clinical utility.

Conclusion: We found a nomogram for predicting the postoperative HAEC. It can be used as a reference for risk assessment and early detection of postoperative HAEC.

Introduction

Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) is characterized by the complete absence of neuronal ganglion cells in a segment of the intestinal tract, most commonly in the large intestine (1). At present, surgery remains the primary effective treatment option for patients with HSCR, with the aganglionic section being removed. Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis (HAEC) is a prevalent and severe complication after radical surgery for HSCR, which can lead to bowel obstruction and sepsis, with a high mortality rate (2). The typical clinical features of HAEC include explosive diarrhea, abdominal distension, fever, lethargy and vomiting. However, these symptoms are non-specific and can be similar to those of other diseases like gastroenteritis, which makes it difficult to identify HAEC in clinical practice and may lead to delayed treatment (3).

Although all patients diagnosed with HSCR are theoretically at risk of developing HAEC, a variety of factors have been identified that contribute to an elevated risk of this complication. These include family history of HSCR, trisomy-21, long-segment aganglionosis, delayed diagnosis, anastomotic leaks or strictures and prior episodes of HAEC (4–12). In addition, intestinal dysbiosis, macrophage infiltration, and neuroimmune abnormalities collectively promote the occurrence of HAEC (5, 13–15). Despite the identification of multiplerisk factors for HAEC, a predictive model for postoperative HAEC has not yet been established. Accordingly, we developed the first nomogram to predict the incidence of HAEC.

Materials and methods

Study design and patients

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fujian Children's Hospital. Patients with confirmed HSCR were conducted at Fujian Children's Hospital, from January 2015 to December 2023. Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients who received surgical treatment at the Fujian Children's Hospital. (2) Patients diagnosed with HSCR based on postoperative pathological results. Exclusion criteria: (1) Postoperative loss of visit. (2) Combination with other congenital anomalies. Diagnostic criteria for HAEC: A score of ≥4 was included in the diagnosis of HAEC according to the scoring system proposed by Pastor (16). The HAEC scoring criteria developed include 18 indicators, covering aspects such as medical history, physical examination, radiological examination, and laboratory examination (17).

Variables

Variables analyzed as risk factors for HAEC included weight, age, sex, enterostomy, standardized anal dilatation, preoperative bowel preparation, preoperative HAEC, type of surgery, type of HSCR, anastomotic leaks or strictures, preoperative hemoglobin concentration and preoperative serum albumin concentrations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS (23.0) and R software (4.4.1). Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and were compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. The categorical data were presented in count and percentage. The continuous data were presented in mean with SD for normally distributed data and the median with interquartile range for non-normal data distribution. Univariate and multivariate factors were analyzed by logistic regressions. When the P-value <0.05, the differences were determined of statistical significance. Nomograms are constructed based on the independent prognostic factors. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves are generated using the data from the training and validation sets, and the area under the curve (AUC) is determined to evaluate the discriminatory capacity of the model. Calibration curves are plotted to examine the accuracy of the model, while decision curve analysis (DCA) is utilized to assess the clinical practicality of the model.

Result

Clinical characteristics and risk factors of postoperative HAEC

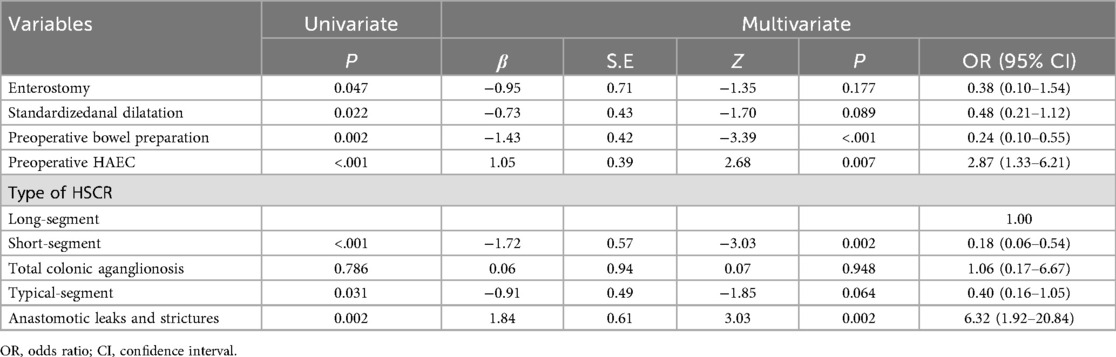

A total of 204 (165 males and 39 females) patients with HSCR, among whom 53 (43 males and 10 females) with HAEC (HAEC group) and 151 (122 males and 29 females) did not with HAEC (non-HAEC group). After univariate logistic regression analysis of the clinical data of the two groups, we found patients who underwent preoperative bowel preparation [HAEC (43.34%) vs. non-HAEC (67.55%), P = 0.002] or standardized anal dilatation [HAEC (20.75%) vs. non-HAEC (38.41%), P = 0.019] were significantly fewer in the postoperative HAEC group compared with the non-HAEC group. The HAEC group had a higher frequency of enterostomy [HAEC (18.87%) vs. non-HAEC (8.61%), P = 0.042] and preoperative HAEC [HAEC (49.06%) vs. non-HAEC (22.52%), P < 0.01]. In the HAEC group, the long-segment and the total colonic aganglionosis were significantly more than the non-HAEC group. Patients with postoperative anastomotic leaks or strictures [HAEC (18.87%) vs. non-HAEC (3.97%), P = 0.002] had a higher incidence of HAEC (Table 1).

Multivariate analysis of predictive factors for postoperative HAEC

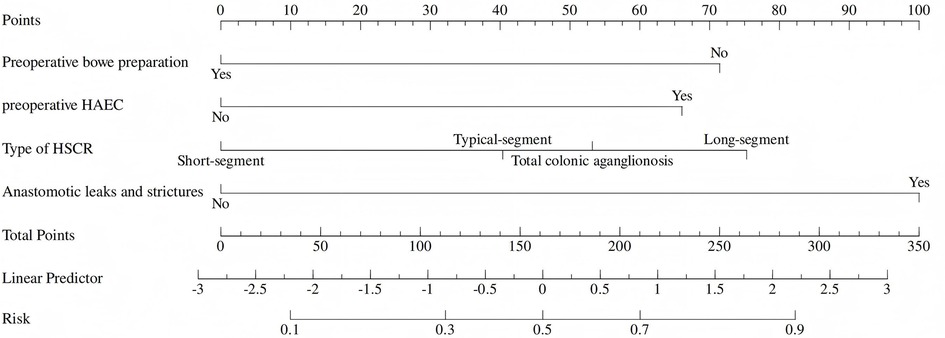

We incorporated all predictors with statistical significance in univariate logistic regression analysis into the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Among them, preoperative HAEC, long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis, and anastomotic leaks or strictures are independent predictive factors influencing postoperative HAEC (P < 0.05). Preoperative bowel preparation is a protective factor for postoperative HAEC (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

Nomogram for predicting postoperative HAEC

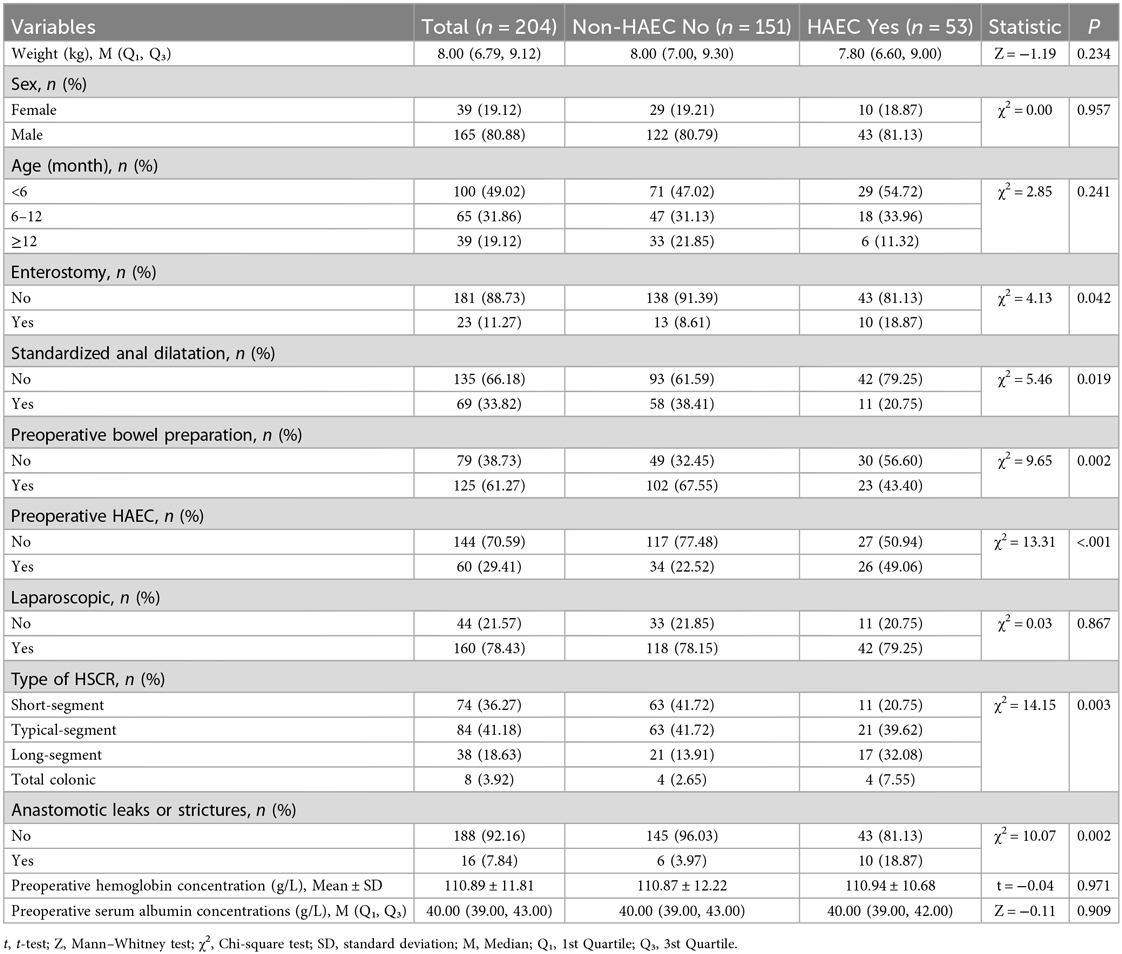

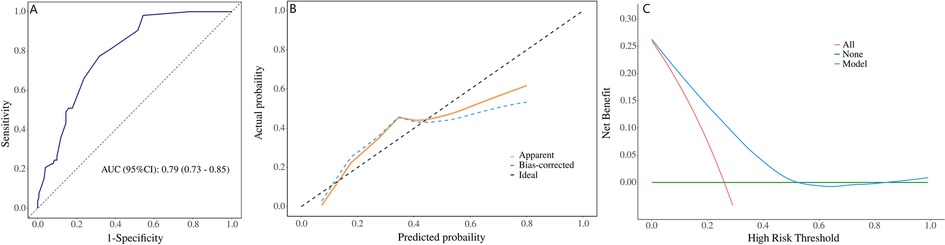

The independent factors above-mentioned including preoperative HAEC, long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis, anastomotic leaks or strictures, and preoperative bowel preparation are used to construct a nomogram (Figure 1). The AUC of the ROC curve of the nomogram is 0.79, the sensitivity is 0.68 (95% CI: 0.61–076), and the specificity is 0.77 (95% CI: 0.66–0.89). Indicating that the nomogram has a great performance in predicting postoperative HAEC. Calibration curves shown that the calibration curve is relatively evenly distributed around the ideal line, indicating great consistency between the nomogram's predictions and the actual results. Decision plots (DCA) demonstrate that our predictive model has great clinical applicability (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Nomogram for predicting postoperative HAEC. (The nomogram to predict the postoperative HAEC was created based on four independent risk factors, including postoperative HAEC, long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis, anastomotic leaks or strictures, and preoperative bowel preparation).

Figure 2. Validation of the nomogram. [(A) ROC curve for the nomogram, AUC = 0.79 (95% CI: 0.73–0.85). (B) Nomogram calibration curve. (C) DCA curve of nomogram. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; DCA, decision curve analysis].

Discussion

HAEC is a serious complication and significant cause of mortality among patients after operation for HSCR (18). Previous studies reported an incidence of postoperative HAEC ranging from 17% to 50% (3, 19, 20). In our study, the prevalence of HAEC was 26%, which is consistent with previous reports. The etiology and pathogenesis of HAEC are still unclear, the diagnosis of HAEC relies on clinical manifestations and symptoms which are often non-specific, making it difficult to establish a definitive diagnosis in many patients (21). In 2009, Pastor (16) proposed a scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of HAEC, which combines clinical, laboratory, and radiological parameters. They use a HAEC score of 10 or greater indicated diagnosis of HAEC. In 2018, Frykman (17) conducted an evaluation involving 116 children diagnosed with HSCR and posited that when the HAEC score was set at 4 or greater, the sum of sensitivity (83.7%) and specificity (98.6%) was optimal. Despite the HAEC scoring system's recent surge in popularity as a diagnostic tool, it is imperative to acknowledge its primary function as a diagnostic instrument rather than a predictive one. The purpose of this study is to construct a prediction model of HAEC for early detection of HAEC.

In recent years, research has identified a variety of risk factors associated with the development of HAEC. However, no studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between factors such as gender, age, preoperative hypoalbuminemia, and surgical method and the occurrence of HAEC (22, 23). In this study, we found the risk factors for HAEC include postoperative HAEC, long-segment or total colonic aganglionosis, and anastomotic leaks or strictures. Preoperative bowel preparation is a protective factor for postoperative HAEC.

We defined aganglionosis from the sigmoid colon onward as long segment and aganglionosis from the whole colon as total colonic aganglionosis (1). Previous studies have found that long-segment and total colonic aganglionosis are risk factors for HAEC (5, 24–26). A widely acknowledged predictor, long-segment have been proved to increase risk of postoperative HAEC by several studies (5). In terms of pathogenesis, long-segment and total colonic aganglionosis may lead to more severe intestinal motility and stasis due to a wider range of enteric nervous system dysfunction, which may lead to an increased risk of bacterial retention, overgrowth and translocation. This series of changes may contribute to the development of HAEC. Preoperative HAEC indicates that the intestine is already in an inflammatory state, and the intestinal barrier function, microbiota balance and immune state may have been impaired. In children with preoperative HAEC, there is an elevation in the quantity of Candida within the feces, concurrent with a reduction in the numbers of Malassezia and yeast (13). All of these factors augment the probability of postoperative recurrence of HAEC, thereby subjecting the postoperative intestine to an elevated risk of inflammation. The history of preoperative HAEC may persistently influence the incidence of postoperative HAEC (11). Intestinal flora translocation, macrophage phenotypic imbalance, and neuroimmune regulatory dysfunction collectively contribute to the pathogenesis of HAEC via intricate interactions. Postoperative intestinal motility disorders in HSCR lead to fecal stasis, which triggers dysbiosis, impairs the integrity of the intestinal barrier, and induces intestinal inflammation (13). The infiltration of M1-type macrophages increases in the lesioned intestinal segments (14). Neuroimmune regulatory disorders further amplify the inflammatory effect (15).

Anastomotic stenosis represents the primary etiological factor for intestinal obstruction subsequent to HSCR. Mechanical intestinal obstruction resulting from anastomotic complications will remarkably augment the risk of postoperative HAEC (7). Anastomotic leaks significantly elevates the risk and severity of postoperative HAEC through disrupting the intestinal barrier, facilitating bacterial translocation, and triggering chronic inflammation, thus emerging as a critical adverse prognostic factor warranting focused clinical surveillance (11, 27). Preoperative rectal irrigation preparation to alleviate mechanical intestinal obstruction can decrease the incidence of HAEC (28). In 2017, a guideline in the United States proposed that routine rectal washouts should be considered a preventative effective measure for HAEC (3). For prophylactic prevention of HAEC, some have advocated for routine rectal washouts in select populations (29). In addition, routine anal dilation within 2 weeks postoperatively and continue for three months can decrease the incidence of HAEC (30). However, there are also questions about the necessity of daily anal dilation. A study found daily dilation by family members to have similar efficacy to weekly dilations by medical staff with similar rates of HAEC (31). Antibiotics are a mainstay of treatment for HAEC, early administration of antibiotics to prevent disease progression should be considered in clinical suspicion of HAEC. Metronidazole is the most commonly used agent and should be instituted even if patients are manifesting mild symptoms (32). A prospective randomized trial found that 4 weeks of probiotic therapy reduced the incidence and severity of HAEC, but more research is needed to further determine its effectiveness in preventing HAEC (33).

Nomogram is a simple visual clinical prediction model. In this study, the AUC of the ROC curve is 0.79, indicating that the nomogram has a great performance in predicting postoperative HAEC. The calibration curve is relatively evenly distributed around the ideal line, indicating great consistency between the nomogram's predictions and the actual results. However, this study has several limitations. First, this study was of a small sample size and was conducted at a single- centre. Second, Most of the risk factors such as preoperative bowel preparation and preoperative HAEC, were hypothetical and have not been confirmed on a scientific basis. We expect to evaluate the performance of this nomogram through prospective external validation and provide treatment guidance for patients with HAEC.

Conclusion

In this study, the risk factors for postoperative HAEC were selected by multivariate analysis, and a nomogram was constructed to predict the possibility of HAEC. The nomogram has good predictive ability for HAEC, and may provide a reference for the need of postoperative preventive measures.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of Fujian Children's Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin. Written informed consent was obtained from the minor(s)' legal guardian/next of kin for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

WZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. WC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. FC: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. YW: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Data curation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. ML: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was funded by the Startup Fund for scientific research, Fujian Medical University (Grant number: 2020QH1213).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patient for their support in this study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Klein M, Varga I. Hirschsprung’s disease-recent understanding of embryonic aspects, etiopathogenesis and future treatment avenues. Medicina (Kaunas). (2020) 56(11):611. doi: 10.3390/medicina56110611

2. Ambartsumyan L, Smith C, Kapur RP. Diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease. Pediatr Devel Pathol. (2019) 23(1):8–22. doi: 10.1177/1093526619892351

3. Gosain A, Frykman PK, Cowles RA, Horton J, Levitt M, Rothstein DH, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Pediatr Surg Int. (2017) 33 (5):517–21. doi: 10.1007/s00383-017-4065-8

4. Chung PHY, Yu MON, Wong KKY, Tam PKH. Risk factors for the development of post-operative enterocolitis in short segment Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatr Surg int. (2018) 35(2):187–91. doi: 10.1007/s00383-018-4393-3

5. Zhang X, Sun D, Xu Q, Liu H, Li Y, Wang D, et al. Risk factors for Hirschsprung disease-associated enterocolitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. (2023) 109(8):2509–24. doi: 10.1097/JS9.0000000000000473

6. Halleran DR, Ahmad H, Maloof E, Paradiso M, Lehmkuhl H, Minneci PC, et al. Does Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis differ in children with and without down syndrome? J Surg Res. (2019) 245:564–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2019.06.086

7. Le-Nguyen A, Righini-Grunder F, Piché N, Faure C, Aspirot A. Factors influencing the incidence of Hirschsprung associated enterocolitis (HAEC). J Pediatr Surg. (2019) 54(5):959–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.026

8. Sakurai T, Tanaka H, Endo N. Predictive factors for the development of postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis in children operated during infancy. Pediatr Surg Int. (2020) 37(2):275–80. doi: 10.1007/s00383-020-04784-z

9. Chantakhow S, Tepmalai K, Tantraworasin A, Khorana J. Development of prediction model for Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis (HAEC) in postoperative Hirschsprung patients. J Pediatr Surg. (2024) 59(12):161696. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2024.161696

10. Wang G, Gao K, Zhang R, Liu Q, Kang C, Guo C. Surgical and clinical determinants of postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: multivariate analysis in a large cohort. Pediatr Discov. (2024) 2(2):e45. doi: 10.1002/pdi3.45

11. Gershon EM, Rodriguez L, Arbizu RA. Hirschsprung’s disease associated enterocolitis: a comprehensive review. World J Clin Pediatr. (2023) 12(3):68–76. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v12.i3.68

12. Lewit RA, Kuruvilla KP, Fu M, Gosain A. Current understanding of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Semin Pediatr Surg. (2022) 31(2):151162. doi: 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2022.151162

13. Shi H, She Y, Mao W, Xiang Y, Xu L, Yin S, et al. 16S rRNA sequencing reveals alterations of gut bacteria in Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Glob Med Genet. (2024) 11(4):263–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0044-1789237

14. Ji H, Lai D, Tou J. Neuroimmune regulation in Hirschsprung’s disease associated enterocolitis. Front Immunol. (2023) 14:1127375. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1127375

15. Zheng Z, Lin L, Lin H, Zhou J, Wang Z, Wang Y, et al. Acetylcholine from tuft cells promotes M2 macrophages polarization in Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Front Immunol. (2025) 16:1559966. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1559966

16. Pastor AC, Osman F, Teitelbaum DH, Caty MG, Langer JC. Development of a standardized definition for Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis: a Delphi analysis. J Pediatr Surg. (2009) 44(1):251–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.052

17. Frykman PK, Kim S, Wester T, Nordenskjöld A, Kawaguchi A, Hui TT, et al. Critical evaluation of the Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis (HAEC) score: a multicenter study of 116 children with Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. (2017) 53(4):708–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.07.009

18. Pini Prato A, Rossi V, Avanzini S, Mattioli G, Disma N, Jasonni V. Hirschsprung’s disease: what about mortality? Pediatr Surg Int. (2011) 27(5):473–8. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2848-2

19. Demehri FR, Halaweish IF, Coran AG, Teitelbaum DH. Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: pathogenesis, treatment and prevention. Pediatr Surg Int. (2013) 29(9):873–81. doi: 10.1007/s00383-013-3353-1

20. Bernstein CN, Kuenzig ME, Coward S, Nugent Z, Nasr A, El-Matary W, et al. Increased incidence of inflammatory bowel disease after Hirschsprung disease: a population-based cohort study. J Pediatr U S. (2021) 233:98–104.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.01.060

21. Bachetti T, Rosamilia F, Bartolucci M, Santamaria G, Mosconi M, Sartori S, et al. The OSMR gene is involved in Hirschsprung associated enterocolitis susceptibility through an altered downstream signaling. Int J Mol Sci. (2021) 22(8):3831. doi: 10.3390/ijms22083831

22. Gunadi , Luzman RA, Kencana SMS, Arthana BD, Ahmad F, Sulaksmono G, et al. Comparison of two different cut-off values of scoring system for diagnosis of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis after transanal endorectal pull-through. Front Pediatr. (2021) 9:705663. doi: 10.3389/fped.2021.705663

23. Yulianda D, Sati AI, Makhmudi A, Gunadi . Risk factors of preoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. BMC Proc. (2019) 13 (Suppl 11):18. doi: 10.1186/s12919-019-0172-y

24. Wardhani AK, Dwiantama K, Iskandar K, Yunus J, Gunadi . Outcomes of children with long-segment and total colon Hirschsprung disease following pull-through. Med J Malaysia. (2024) 79(Suppl 4):1–5.39215407

25. Hagens J, Reinshagen K, Tomuschat C. Prevalence of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis in patients with Hirschsprung disease. Pediatr Surg Int. (2021) 38(1):3–24. doi: 10.1007/s00383-021-05020-y

26. Xie C, Yan J, Zhang Z, Kai W, Wang Z, Chen Y. Risk factors for Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis following soave: a retrospective study over a decade. BMC Pediatr. (2022) 22(1):654. doi: 10.1186/s12887-022-03692-6

27. Chantakhow S, Tepmalai K, Singhavejsakul J, Tantraworasin A, Khorana J. Prognostic factors of postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: a cohort study. Pediatr Surg Int. (2023) 39(1):77. doi: 10.1007/s00383-023-05364-7

28. Hackam DJ, Filler RM, Pearl RH. Enterocolitis after the surgical treatment of Hirschsprung’s disease: risk factors and financial impact. J Pediatr Surg. (1998) 33 (6):830–3. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90652-2

29. Frykman PK, Shor SS. Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: prevention and therapy. Semin Pediatr Surg. (2012) 21(4):328–35. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2012.07.007

30. Singh R, Cameron BH, Walton JM, Farrokhyar F, Borenstein SH, Fitzgerald PG. Postoperative Hirschsprung’s enterocolitis after minimally invasive Swenson’s procedure. J Pediatr Surg. (2007) 42(5):885–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.055

31. Temple SJ, Shawyer A, Langer JC. Is daily dilatation by parents necessary after surgery for Hirschsprung disease and anorectal malformations? J Pediatr Surg. (2012) 47(1):209–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.10.048

32. Bischoff W, Bubnov A, Palavecino E, Beardsley J, Williamson J, Johnson J, et al. The impact of diagnostic stewardship on clostridium difficile infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. (2017) 4(suppl_1):S398. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx163.992

Keywords: nomogram, Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis, risk factors, children, predicting

Citation: Zheng W, Chen W, Chen F, Wang Y, Zhu L and Liu M (2025) Development of a nomogram for predicting postoperative Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Front. Pediatr. 13:1640331. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1640331

Received: 3 June 2025; Accepted: 2 September 2025;

Published: 16 September 2025.

Edited by:

Li Hong, Shanghai Children's Medical Center, ChinaReviewed by:

Zhiyan Zhan, Shanghai Children's Medical Center, ChinaHongxing Li, Children's Hospital of Nanjing Medi, China

Copyright: © 2025 Zheng, Chen, Chen, Wang, Zhu and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mingkun Liu, bGl1bWluZ2t1bkBmanNldHl5LmNvbQ==

†These authors share first authorship

Weijun Zheng

Weijun Zheng Weiming Chen

Weiming Chen Fei Chen

Fei Chen Yunjin Wang1

Yunjin Wang1 Mingkun Liu

Mingkun Liu