- 1School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Cheeloo College of Medicine, Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

- 2University of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences, Qingdao, Shandong, China

- 3Department of Infection Control, Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Jinan, Shandong, China

Background: Neonatal sepsis (NS) is a serious infection in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) that treatment challenges due to evolving antimicrobial resistance and a substantial healthcare burden. The aim of this study was to analyze the pathogenic characteristics of NS in Chinese NICUs and its independent impact on length of stay (LOS) and hospitalization costs.

Methods: A retrospective case-control study was conducted including 978 neonates from two tertiary NICUs between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024. Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to balance the baseline characteristics between the NS and non-NS groups. Generalized linear models (GLM) were used to quantify the LOS and hospitalization costs attributable to NS. Pathogen distribution and antimicrobial resistance patterns were also assessed.

Results: The incidence of NS was 8.28%. The predominant pathogens of NS were Gram-positive bacteria (71.7%), with Staphylococcus epidermidis (50.5%) being the predominant pathogen. Notably, multidrug-resistant (MDR) strains accounted for 65.7% of all isolates. Antimicrobial resistance analysis revealed high resistance rates of Gram-positive bacteria to penicillin G (94.6%) and oxacillin (89.3%). Gram-negative pathogens exhibited high resistance to levofloxacin (75.0%), ceftriaxone (66.7%), cefepime (66.7%), and meropenem (58.3%). After PSM, the attributable LOS for NS was 11 days (P = 0.002) and the attributable cost for NS was $6,035.34 (P < 0.001). GLM analysis showed that the LOS attributable to NS was 3.99 times longer (95% CI: 3.46–4.68) and total hospitalization costs were 1.68 times higher (95% CI: 1.42–2.00) than in non-NS patients.

Conclusions: NS significantly increases the hospitalization resource consumption in NICUs. This study provides key evidence for optimizing antibiotic use strategies and advancing precision healthcare payment reform, and calls for integrating resistance surveillance with cost-control measures to reduce the health economic impact of NS.

1 Introduction

Neonatal sepsis (NS), a common and often fatal infection in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), has become a major global public health challenge due to its high incidence and mortality. Epidemiological data estimate the global incidence of NS at 2,824 cases per 100,000 live births, with approximately 11%–19% of neonatal deaths attributed to NS annually (1, 2). Studies from China report that the incidence of NS in NICUs ranges from 1.8% to 15.2%, which significantly increases the risk of infant mortality and adverse outcomes (3, 4).

In recent years, advances in perinatal medicine and critical care technologies have led to improved survival of preterm infants and increased use of various invasive procedures. Consequently, the spectrum of pathogens causing NS has evolved significantly. In China, Gram-positive bacteria, particularly coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS) and Staphylococcus aureus, have emerged as the predominant pathogens (5, 6). In addition, the detection rates of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE), have been rising annually, further complicating treatment and increasing healthcare costs (7). Therefore, clarifying the pathogen distribution and antimicrobial resistance characteristics of NS is crucial for developing effective infection control strategies, optimizing antibiotic use policies, and reducing the economic burden on healthcare systems.

Neonatal sepsis is clinically categorized based on the time of onset into early-onset (EONS, within 72 h of birth) and late-onset (LONS, after 72 h) neonatal sepsis, which have distinct pathogenesis and etiologies. EONS is primarily caused by vertical transmission of bacteria from mother to infant during delivery, with pathogens such as Group B Streptococcus and Escherichia coli being historically predominant (8–10). Its incidence shows significant geographical variation, being considerably higher in South Asia (approximately 9.8 per 1,000 live births) compared to North America (0.2–1.0 per 1,000 live births) (11–13). In contrast, LONS is mainly acquired from the postnatal hospital environment, often involving nosocomial pathogens like Klebsiella spp., Staphylococcus aureus, and fungi (14, 15). LONS is particularly prevalent among preterm and low-birth-weight infants, with up to 15% of this vulnerable population in high-income countries being affected (13). Both forms of sepsis are associated with substantial mortality, ranging from 18% to 36%, and an increased risk of adverse long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes among survivors (16–18). This distinction is critical for guiding empirical antibiotic therapy and infection control strategies.

NS not only threatens individual health but also imposes a significant economic burden on healthcare systems through resource consumption. Once present, NS can exacerbate the condition of neonates and prolong the length of stay (LOS), which reduces bed utilization efficiency and generates additional economic burdens on healthcare systems (19). However, the economic burden of sepsis has been extensively studied in adult populations (20, 21), while evidence on its health economics in neonatal populations remains scarce, particularly from China. Data from Brazil indicated that the average hospitalization cost for NS ranges from $2,970.60 to $4,305.03 (22). However, these findings may not be generalizable to different healthcare systems due to differences in national or regional economic levels, hospital levels, and medical insurance reimbursement policies. In addition, most previous studies failed to control for confounding factors such as sex, gestational age, and birth weight, which may introduce bias into cost assessments. Therefore, this study aims to establish comparable groups of septic and non-septic neonates using propensity score matching (PSM) to quantify the impact of NS on NICU LOS and hospitalization costs. Meanwhile, by integrating data on pathogenetic characteristics, antimicrobial resistance patterns and economic burden results of NS, the findings collectively provide localized evidence to optimize infection control strategies and rationalize healthcare resource allocation in the NICU.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study design and population

This retrospective case-control study was conducted in the NICUs of two university-affiliated tertiary hospitals in Shandong Province, China, between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024. The obstetric ward of each hospital admits approximately 5,000–7,000 births per year, and the NICU admits over 1,500 neonates annually. The case group included neonates diagnosed with NS, and the control group comprised non-NS neonates hospitalized during the same period. To compare the differences in LOS and hospitalization costs between the two groups, confounders were controlled through PSM. All neonates admitted to the NICU aged ≤28 days during the study period were included in this study. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) neonates with severe congenital malformations or inherited metabolic diseases; (2) neonates with concurrent severe infections in other organs, as these conditions can independently prolong hospital stays and increase costs, thereby confounding the attribution of resource use solely to sepsis; (3) neonates who died or were discharged within 24 h of admission, to ensure a sufficient observation period for assessing the development and impact of NS; and (4) neonates with incomplete medical records. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shandong University (2024-R-174). As a non-interventional observational study, the committee waived the requirement for informed consent.

2.2 Diagnostic criteria for NS

The diagnosis of NS was based on the Expert Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Neonatal Bacteria Sepsis (2024) (23). Confirmed cases required pathogen identification through blood culture or sterile cavity fluid culture (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid), with clinical manifestations consistent with the identified pathogens. According to the time of onset, NS was classified into early-onset sepsis (EONS, occurring ≤72 h after birth) and late-onset sepsis (LONS, occurring >72 h after birth).

2.3 Data collection

Demographic data (sex, gestational age, birth weight, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min, mode of delivery) and perinatal risk factors (duration of rupture of membranes, meconium-stained amniotic fluid) were collected from the hospital electronic medical record system for all participants. Outcome variables included total LOS and hospitalization costs. The total LOS was defined as the difference between the date of admission and discharge (in days). The total hospitalization costs covered direct medical expenses, including comprehensive medical service category (general medical service costs, general treatment operating costs, nursing costs), diagnosis category (pathological diagnosis costs, laboratory diagnostic costs, imaging diagnostic costs, clinical diagnosis project costs), treatment category (non-surgical clinical physiotherapy costs, surgical treatment costs), Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) costs (refers to costs incurred from treatments using TCM techniques or herbal medicines), medication category (western medicine costs, which includes antibacterial drug costs), blood product costs, consumable material category (treatment disposable medical materials costs and Surgical disposable medical materials costs). The totals were converted to US dollars based on the 2024 exchange rate (1 US$ = 7.1217 RMB). In addition, NS-related pathogenic data, including infection onset time, pathogen type, antimicrobial susceptibility testing results and MDR status [defined as bacteria resistant to at least one agent in three or more antimicrobial categories (24)], were extracted from the hospital infection management information system.

2.4 Statistical analysis

A logistic regression model was used to calculate the propensity score, with NS as the dependent variable and covariates including sex, gestational age, birth weight, Apgar scores, mode of delivery, duration of rupture of membranes, and meconium-stained amniotic fluid. The matching process was performed using the “MatchIt” R package with optimal matching at a 1:2 ratio between cases and controls to ensure balanced baseline characteristics. Continuous variables were described as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range, IQR) based on data distribution, while categorical variables were expressed as frequency (percentage). Differences between continuous variables were compared using the two independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, and differences between categorical variables were compared using the chi-square or Fisher's exact tests.

Then, generalized linear models (GLMs) were constructed with LOS (negative binomial distribution) or hospitalization costs (gamma distribution) as the dependent variable, using a log-link function. All covariates and NS occurrence were included as independent variables. The missing data were imputed using the multiple imputation approach implemented with the “mice” package in R. Data were analyzed using R software 4.4.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). For standard analyses, a two-sided P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Patient inclusion

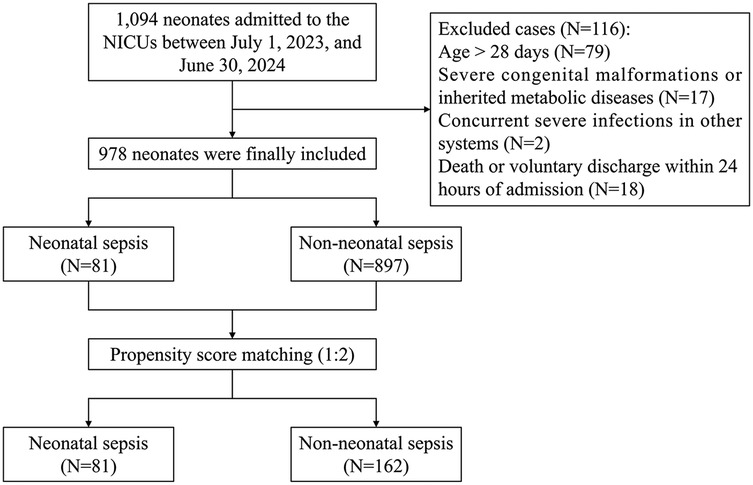

A total of 1,094 neonates were admitted to the NICUs of the two hospitals between July 1, 2023, and June 30, 2024. After excluding 116 neonates who did not meet the inclusion criteria, 978 neonates were finally included. Throughout the study period, only three in-hospital deaths (0.3%) were recorded. However, a notably high rate of discharge against medical advice was observed, accounting for 4.6% (45/978) of the cohort. Before matching, the cohort comprised 81 neonates in the NS group and 897 in the non-NS group. Following 1:2 PSM, there were 81 in the NS group and 162 in the non-NS group. Figure 1 presents a flow chart of patient selection and study design.

3.2 Pathogen distribution of neonatal sepsis

Among the 978 neonates included, 81 were diagnosed with NS, with an incidence of 8.28%. A total of 99 pathogens were isolated. Gram-positive bacteria (71.7%) were predominant, with S. epidermidis (50.5%) being the most common. As detailed in Table 1, the pathogen profile differed between EONS and LONS. Although Gram-positive bacteria were predominant in both groups, they constituted a higher proportion in LONS (83.3%) than in EONS (69.1%). Conversely, Gram-negative bacteria were more prevalent in EONS (28.4%) than in LONS (16.7%).

Further stratification by gestational age revealed that the incidence of NS was significantly higher in preterm infants (69/586, 11.77%) than in term infants (12/392, 3.06%). The etiology also varied by gestational age group. In preterm infants, the vast majority of cases were EONS (64/69, 92.8%), characterized by a high prevalence of Gram-positive bacteria (68.8% of isolates). In contrast, term infants with NS were more likely to develop LONS (8/12, 66.7%), which also exhibited a Gram-positive dominant profile (84.6% of isolates).

In addition, most of the isolated pathogens were found to be MDR, with 65 of 99 isolates classified as MDR pathogens. The most frequent MDR bacteria included methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis (43/65), carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae (4/65), extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli (4/65), and carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa (4/65).

3.3 Antimicrobial resistance of neonatal sepsis pathogens

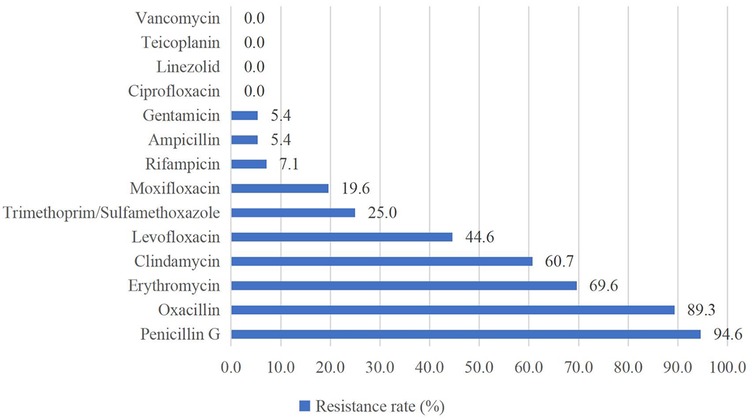

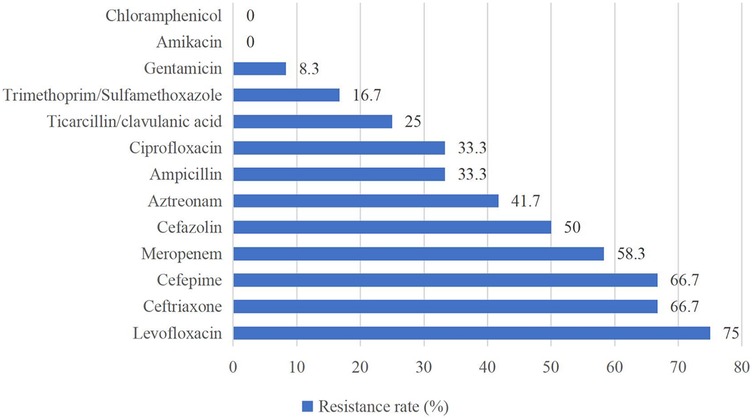

Of the Gram-positive bacteria detected, almost all strains were resistant to penicillin G (94.6%) and oxacillin (89.3%). None of the strains were resistant to vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid, or ciprofloxacin (Figure 2). For Gram-negative bacteria, high resistance rates (above 50%) were observed for levofloxacin (75.0%), ceftriaxone (66.7%), cefepime (66.7%), and meropenem (58.3%). Gram-negative bacteria showed the highest susceptibility to chloramphenicol and amikacin (Figure 3).

3.4 Baseline characteristics before and after PSM

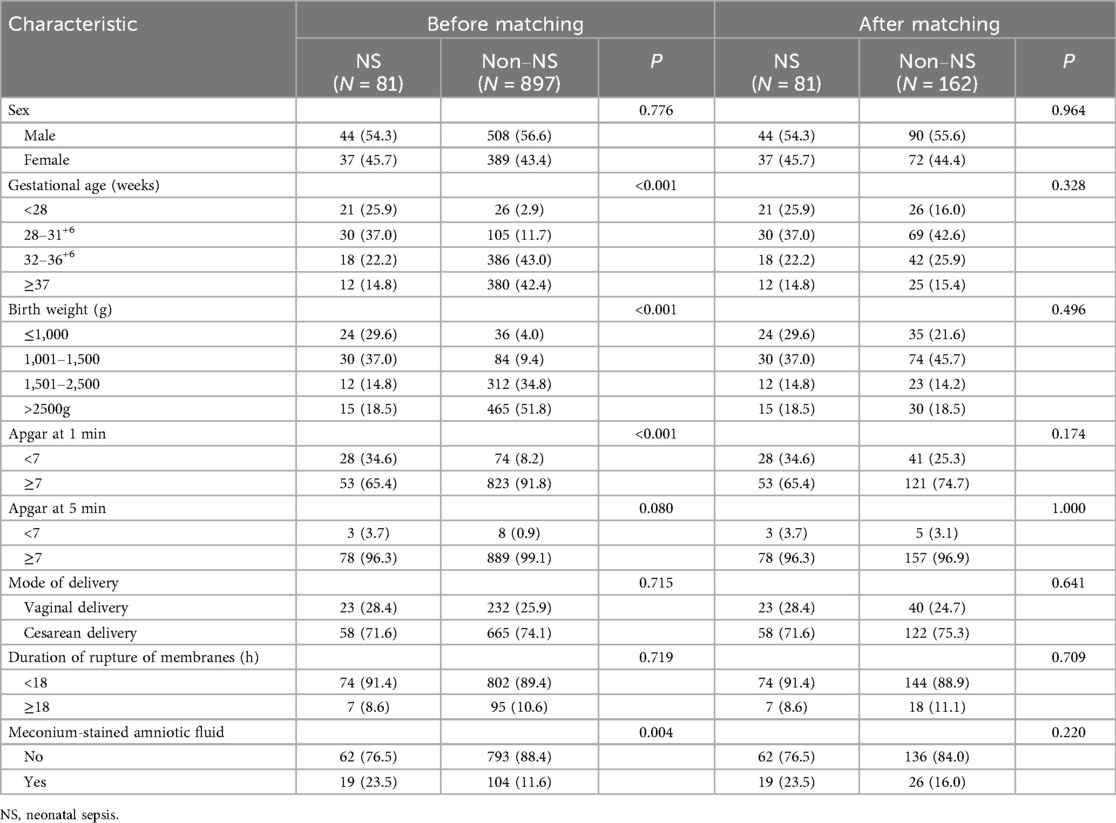

The baseline characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 2. Among all included neonates, males were more common, and most deliveries were by cesarean section. Before matching, the NS group and the non-NS group differed significantly in several baseline clinical characteristics. The NS group had a higher proportion of extremely preterm infants (<28 weeks: 25.9% vs. 2.9%) and extremely low birth weight infants (≤1,000 g: 29.6% vs. 4.0%), lower Apgar scores at 1 min (<7: 34.6% vs. 8.2%), and higher rates of meconium-stained amniotic fluid (23.5% vs. 11.6%) (all P < 0.05). After 1:2 PSM, all variables were balanced between the case and control groups with no significant differences (all P > 0.05).

3.5 Comparison of LOS and hospitalization costs after PSM

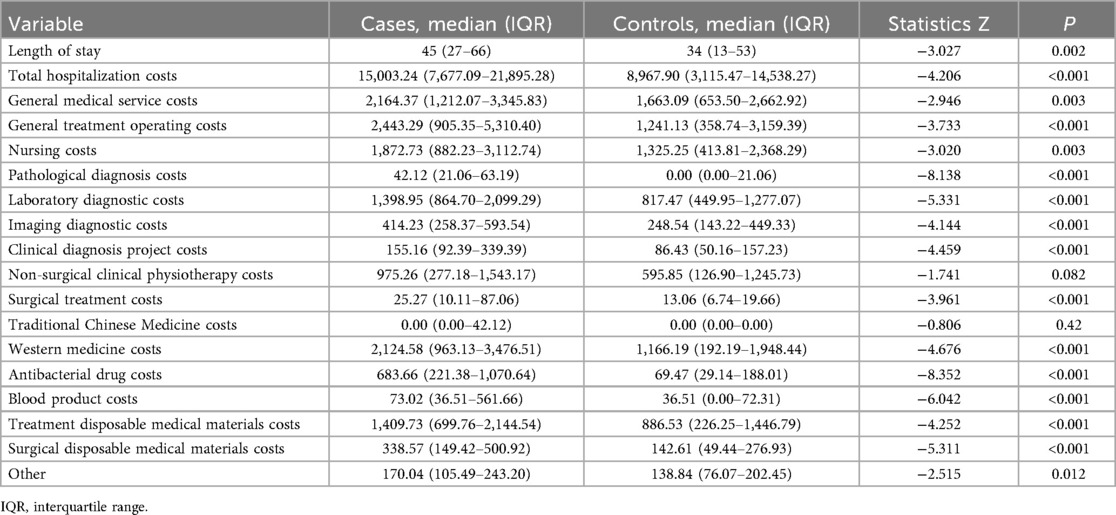

After PSM, the median LOS in the case group was 45 days, significantly longer than the 34 days in the control group (P = 0.002), with a median difference of 11 days. The median total hospitalization costs were $15,003.24 and $8,967.90 for the case and control groups, respectively, with a difference of $6,035.34 (P < 0.001). Comparison of hospitalization costs between groups showed statistically significant differences in all categories except for non-surgical clinical physiotherapy costs and TCM costs, as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of length of stay (days) and hospitalization cost (US$) between the matched pairs (neonatal sepsis group vs. control group).

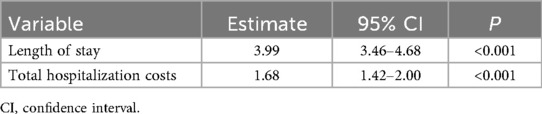

3.6 GLM analysis of LOS and hospitalization costs between groups

In the negative binomial regression model, the LOS attributable to NS was 3.99 times (95% CI: 3.46–4.68, P < 0.001) higher than that in non-NS infants. Gamma regression analysis showed that total hospitalization costs attributable to NS were 1.68 times (95% CI: 1.42–2.00, P < 0.001) higher than those in non-NS infants, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Generalized linear model analysis of neonatal sepsis-associated length of stay (days) and total hospitalization costs (US$).

4 Discussion

This study systematically assessed the impact of NS on hospitalization resource consumption by constructing a comparable cohort through PSM. Our findings revealed an NS incidence of 8.28% among all infants admitted to the NICUs during the study period, with S. epidermidis as the predominant pathogen. Post-PSM analysis demonstrated that NS prolonged hospitalization by 11 days and increased total costs by $6,035.34. GLM analysis quantified the attributable effects of NS, demonstrating a 3.99-fold increase in LOS and a 68% higher total hospitalization cost compared to non-NS infants.

Globally, the incidence of NS shows significant geographical heterogeneity (0.30%–17.0%) (1, 25). In this study, the NS incidence was 8.28%, which was higher than the prevalence reported in a multicenter study covering seven low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (4.69%) (26). This discrepancy may be attributed to differences in preterm birth rates and the proportion of low birth weight (LBW) infants in different countries, as well as to socioeconomic disparities affecting access to healthcare resources and the quality of perinatal care. Due to the specific nature of the hospitals included in this study as regional tertiary referral centers, they admitted more preterm and LBW infants, suggesting that our study population had greater clinical severity. It is important to note that our incidence estimate was limited to neonates admitted to NICUs and did not cover potential cases in community or general obstetrics wards, which may overestimate the actual burden of disease at the population level. Notably, the in-hospital mortality was low (0.3%), but a substantial number of families chose discharge against medical advice. This reflects scenarios where families may have opted to withdraw treatment due to the infant's critical condition, financial constraints, or a perceived poor prognosis. Thus, the true mortality burden may be higher than recorded.

Pathogenic analysis showed that Gram-positive bacteria (71.7%) were the major pathogens in our study, with CoNS being the most prevalent, a finding consistent with reports from other tertiary NICUs (4, 7, 27). This contrasts sharply with the Gram-negative bacterial dominance commonly reported in studies from LMICs (28–31), highlighting the influence of healthcare settings on etiology. Our findings confirm the significant epidemiological and etiological distinctions between EONS and LONS. The higher incidence of EONS in our study aligns with its established link to maternal peripartum factors and vertical transmission. Given this established link, the management of conditions like preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) becomes essential. Current obstetrical guidelines universally advocate for the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in cases of PPROM, a practice aimed at reducing the incidence of EONS (32). Our data indicate that EONS imposes a significant burden, underscoring the value of this evidence-based intervention. In contrast, the lower incidence of LONS likely reflects its association with prolonged hospitalization and invasive procedures in a more selected, high-risk preterm population.

Notably, the particularly high rate of S. epidermidis in EONS, especially among preterm infants, highlights its role as a primary opportunistic pathogen in the NICU environment. Its ability to form biofilms on medical device surfaces and resist a wide range of disinfectants provides a transmission advantage in NICUs where invasive procedures are frequent (33). The notable absence of Group B Streptococcus in our EONS cases likely reflects the successful implementation of maternal screening and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis.

The absence of fungal pathogens in our LONS cases may be partly attributable to the 12-month study period. Given the declining incidence and sporadic nature of invasive fungal infections in neonates in recent years (34), a longer surveillance period is often required to adequately capture their true prevalence. Additionally, the routine use of antifungal prophylaxis in high-risk infants and strict infection control practices in our unit may have further contributed to this observed absence. Nevertheless, continuous surveillance remains imperative, as fungal sepsis continues to be a significant threat in NICUs worldwide.

The stratification by gestational age unveiled critical insights. Preterm infants constituted the overwhelming majority of our sepsis cases, primarily presenting with EONS. This underscores the paramount role of prematurity and its associated immune immaturity as the principal risk factor for NS (8, 35). Conversely, term infants with sepsis in our study predominantly developed LONS, a finding that warrants further investigation but may relate to specific nosocomial exposures or unmeasured clinical complexities. This stark contrast emphasizes that the profile of neonatal sepsis in a given population is largely dictated by the proportion of preterm births, necessitating tailored prevention strategies for different gestational age groups.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing indicated that Gram-positive bacteria showed widespread resistance to β-lactam antibiotics (penicillin G 94.6%, oxacillin 89.3%), which is consistent with findings from other studies (36, 37). Additionally, 100% of Gram-positive bacteria in this study remained susceptible to vancomycin, teicoplanin, linezolid, and ciprofloxacin, similar to the results reported by Tessema et al. (36). These findings provide critical therapeutic options for Gram-positive bacterial infections, but these “last-resort” antibiotics need to be used with caution to avoid the development of resistance. Both our study and studies in other regions demonstrated high susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria to chloramphenicol and amikacin (37–39), suggesting that these two drugs may be considered as potential antibiotics for the empirical treatment of NS caused by Gram-negative bacteria in the future, but their inherent toxicities (e.g., gray baby syndrome, ototoxicity) necessitate rigorous risk-benefit evaluation. Furthermore, the high percentage of MDR strains (65.7%), predominantly MRSE, may be closely related to mecA-mediated β-lactam resistance and selection pressure for broad-spectrum antibiotics in the hospital setting (40). In addition, MRSE enhances colonization through biofilm formation and may acquire additional resistance genes (e.g., aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes) through horizontal gene transfer, further entrenching its MDR phenotype (41).

Our study quantified the independent impact of NS on healthcare resources through PSM. The median LOS for infants with NS was 45 days, and the median total hospitalization cost was $15,003. A systematic review of sepsis studies in several countries (21) reported that the average total hospitalization cost for sepsis patients in China was $13,292, which was similar to our findings. However, another systematic review that included 20 studies from high- and middle-income countries (HMICs) showed that the cost of sepsis treatment in all middle-income countries ($55–$3,607) was much lower than that in the United States ($64,047–$129,632) (42). This disparity stems from the differences in healthcare cost allocation, treatment strategies, and medical insurance systems between countries of different income levels. High-income countries are dominated by expenditures on labor costs, advanced antibiotics, and organ support technologies, while middle-income countries face higher spending on medications and consumables due to antimicrobial resistance challenges and resource constraints. At the same time, variations in insurance coverage, reimbursement rates, and payment models in different countries further influence patient financial burdens and healthcare cost control. In addition, differences in LOS can further exacerbate cost differentiation, as the above review (42) noted that high-income countries reported an average LOS of 24–72 days, while middle-income countries reported only 4–14 days. In our study, the LOS (45 days) and total cost ($15,003) were intermediate. As a upper-middle-income country, China's healthcare system has unique characteristics. Whereas regional disparities in healthcare resources have led to the concentration of critically ill infants in tertiary hospitals similar to our study sites, prolonging LOS, medical insurance cost-containment policies such as centralized procurement and diagnosis-related groups (DRGs)/disease intervention package (DIP) payment reforms have partially reduced healthcare costs for both patients and hospitals.

Our study also showed that the NS group had significantly higher expenditures in each medical cost subcategory, except for non-surgical clinical physiotherapy costs and TCM costs. The greatest differences were observed in general treatment operating costs, western medicine costs, and laboratory diagnostic costs, consistent with the results of a related study in China (43). The high expenditure of general treatment operating costs stemmed from frequent invasive procedures and intensive care required by NS infants due to their critical health status. The disparity in western medicine costs was primarily caused by antibacterial drug costs, as NS management necessitates the long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the prevalence of multidrug-resistant bacteria often forces clinics to use expensive combination regimens. In addition, the increase in laboratory diagnostic costs may be associated with additional pathogen identification tests, repeated blood cultures, and dynamic monitoring of inflammatory markers (e.g., procalcitonin, IL-6), which are essential for guiding antibiotic therapy but significantly increase the frequency and costs of testing. Therefore, while ensuring precision in NS diagnosis and treatment, it is still necessary to rationally control the costs of general treatment operations, antimicrobial drug use, and laboratory diagnostics to optimize resource utilization and reduce patient financial burdens.

This study has several limitations. First, as a retrospective observational study, although PSM was applied to control for known confounders, the potential influence of unmeasured confounders cannot be fully excluded. For instance, missing data on perinatal antibiotic exposure preclude a detailed analysis of its impact on initial microbial colonization and subsequent pathogen characteristics in sepsis cases, which represents a potential confounding factor. Second, the data were obtained from only two tertiary hospitals, potentially leading to overestimation of NS incidence due to the concentration of critically ill neonates. Future studies should include data from community hospitals or general obstetrics wards to fully reflect the epidemiological characteristics of NS. Third, the cost analysis did not include indirect costs (e.g., family productivity loss and long-term sequelae costs), which may have led to underestimation of the overall economic burden of NS. Finally, the 12-month study period limited the assessment of seasonal epidemiological changes or long-term antimicrobial resistance trends. Prospective multicenter cohort studies are needed in the future to comprehensively evaluate the health economic impacts of NS and the dynamics of antimicrobial resistance transmission.

5 Conclusion

This study systematically assessed the independent impact of NS on NICU LOS and hospitalization costs through the PSM approach and provided localized evidence of NS-attributable costs in the Chinese context. The findings demonstrated that NS had a significant impact on healthcare resource consumption, highlighting its role as a major health economic challenge in NICUs. The study also suggests that policymakers to combine antimicrobial resistance surveillance and cost-containment strategies to promote the implementation of precision health economy policies.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing and Rehabilitation, Shandong University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because As a non-interventional observational study, the committee waived the requirement for informed consent.

Author contributions

BZ: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. PZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ZL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. ZW: Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. LG: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. SM: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. FX: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. XL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 72474121).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Fleischmann C, Reichert F, Cassini A, Horner R, Harder T, Markwart R, et al. Global incidence and mortality of neonatal sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. (2021) 106(8):745–52. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-320217

2. Dong Y, Basmaci R, Titomanlio L, Sun B, Mercier JC. Neonatal sepsis: within and beyond China. Chin Med J (Engl). (2020) 133(18):2219–28. doi: 10.1097/cm9.0000000000000935

3. Ji H, Yu Y, Huang L, Kou Y, Liu X, Li S, et al. Pathogen distribution and antimicrobial resistance of early onset sepsis in very premature infants: a real-world study. Infect Dis Ther. (2022) 11(5):1935–47. doi: 10.1007/s40121-022-00688-8

4. Lim WH, Lien R, Huang YC, Chiang MC, Fu RH, Chu SM, et al. Prevalence and pathogen distribution of neonatal sepsis among very-low-birth-weight infants. Pediatr Neonatol. (2012) 53(4):228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.06.003

5. de Mello Freitas FT, Viegas APB, Romero GAS. Neonatal healthcare-associated infections in Brazil: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Public Health. (2021) 79(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13690-021-00611-6

6. Wu R, Cui X, Pan R, Li N, Zhang Y, Shu J, et al. Pathogenic characterization and drug resistance of neonatal sepsis in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. (2025) 44(4):779–88. doi: 10.1007/s10096-025-05048-1

7. Song WS, Park HW, Oh MY, Jo JY, Kim CY, Lee JJ, et al. Neonatal sepsis-causing bacterial pathogens and outcome of trends of their antimicrobial susceptibility a 20-year period at a neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Exp Pediatr. (2022) 65(7):350–7. doi: 10.3345/cep.2021.00668

8. Shane AL, Sánchez PJ, Stoll BJ. Neonatal sepsis. Lancet. (2017) 390(10104):1770–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)31002-4

9. Bethou A, Bhat BV. Neonatal sepsis-newer insights. Indian J Pediatr. (2022) 89(3):267–73. doi: 10.1007/s12098-021-03852-z

10. Simonsen KA, Anderson-Berry AL, Delair SF, Davies HD. Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2014) 27(1):21–47. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00031-13

11. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Sánchez PJ, Faix RG, Poindexter BB, Van Meurs KP, et al. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group b streptococcal and E. Coli disease continues. Pediatrics. (2011) 127(5):817–26. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2217

12. Sgro M, Kobylianskii A, Yudin MH, Tran D, Diamandakos J, Sgro J, et al. Population-based study of early-onset neonatal sepsis in Canada. Paediatr Child Health. (2019) 24(2):e66–73. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxy018

13. Giannoni E, Agyeman PKA, Stocker M, Posfay-Barbe KM, Heininger U, Spycher BD, et al. Neonatal sepsis of early onset, and hospital-acquired and community-acquired late onset: a prospective population-based cohort study. J Pediatr. (2018) 201:106–114.e104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.05.048

14. Carl MA, Ndao IM, Springman AC, Manning SD, Johnson JR, Johnston BD, et al. Sepsis from the gut: the enteric habitat of bacteria that cause late-onset neonatal bloodstream infections. Clin Infect Dis. (2014) 58(9):1211–8. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu084

15. Downie L, Armiento R, Subhi R, Kelly J, Clifford V, Duke T. Community-acquired neonatal and infant sepsis in developing countries: efficacy of who’s currently recommended antibiotics–systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. (2013) 98(2):146–54. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-302033

16. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Higgins RD, Fanaroff AA, Duara S, Goldberg R, et al. Very low birth weight preterm infants with early onset neonatal sepsis: the predominance of gram-negative infections continues in the national institute of child health and human development neonatal research network, 2002–2003. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2005) 24(7):635–9. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000168749.82105.64

17. Pammi M, Weisman LE. Late-onset sepsis in preterm infants: update on strategies for therapy and prevention. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. (2015) 13(4):487–504. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1008450

18. Kohli-Lynch M, Russell NJ, Seale AC, Dangor Z, Tann CJ, Baker CJ, et al. Neurodevelopmental impairment in children after group b streptococcal disease worldwide: systematic review and meta-analyses. Clin Infect Dis. (2017) 65(suppl_2):S190–s199. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix663

19. Sisay EA, Mengistu BL, Taye WA, Fentie AM, Yabeyu AB. Length of hospital stay and its predictors among neonatal sepsis patients: a retrospective follow-up study. Int J Gen Med. (2022) 15:8133–42. doi: 10.2147/ijgm.S385829

20. van den Berg M, van Beuningen FE, Ter Maaten JC, Bouma HR. Hospital-related costs of sepsis around the world: a systematic review exploring the economic burden of sepsis. J Crit Care. (2022) 71:154096. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2022.154096

21. Arefian H, Heublein S, Scherag A, Brunkhorst FM, Younis MZ, Moerer O, et al. Hospital-related cost of sepsis: a systematic review. J Infect. (2017) 74(2):107–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2016.11.006

22. de Abreu M, Ogata JFM, Fonseca MCM, Sansone D, Guinsburg R. The financial impact of neonatal sepsis on the Brazilian unified health system. Clinics (Sao Paulo. (2023) 78:100277. doi: 10.1016/j.clinsp.2023.100277

23. Subspecialty Group of Neonatology tSoPCMA, Editorial Board CJoP. Expert consensus on diagnosis and management of neonatal bacteria sepsis (2024). Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. (2024) 62(10):931–40. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112140-20240505-00307

24. Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect. (2012) 18(3):268–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x

25. Fleischmann-Struzek C, Goldfarb DM, Schlattmann P, Schlapbach LJ, Reinhart K, Kissoon N. The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review. Lancet Respir Med. (2018) 6(3):223–30. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(18)30063-8

26. Milton R, Gillespie D, Dyer C, Taiyari K, Carvalho MJ, Thomson K, et al. Neonatal sepsis and mortality in low-income and middle-income countries from a facility-based birth cohort: an international multisite prospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. (2022) 10(5):e661–72. doi: 10.1016/s2214-109x(22)00043-2

27. Downey LC, Smith PB, Benjamin DK Jr. Risk factors and prevention of late-onset sepsis in premature infants. Early Hum Dev. (2010) 86(Suppl 1):7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.01.012

28. Uwe NO, Ezenwa BN, Fajolu IB, Oshun P, Chukwuma ST, Ezeaka VC. Antimicrobial susceptibility and neonatal sepsis in a tertiary care facility in Nigeria: a changing trend? JAC Antimicrob Resist. (2022) 4(5):dlac100. doi: 10.1093/jacamr/dlac100

29. Worku E, Fenta DA, Ali MM. Bacterial etiology and risk factors among newborns suspected of sepsis at hawassa, Ethiopia. Sci Rep. (2022) 12(1):20187. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-24572-0

30. Kabwe M, Tembo J, Chilukutu L, Chilufya M, Ngulube F, Lukwesa C, et al. Etiology, antibiotic resistance and risk factors for neonatal sepsis in a large referral center in Zambia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2016) 35(7):e191–198. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000001154

31. Akbarian-Rad Z, Riahi SM, Abdollahi A, Sabbagh P, Ebrahimpour S, Javanian M, et al. Neonatal sepsis in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis on national prevalence and causative pathogens. PLoS One. (2020) 15(1):e0227570. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227570

32. Tsakiridis I, Mamopoulos A, Chalkia-Prapa EM, Athanasiadis A, Dagklis T. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: a review of 3 national guidelines. Obstet Gynecol Surv. (2018) 73(6):368–75. doi: 10.1097/ogx.0000000000000567

33. Chokr A, Watier D, Eleaume H, Pangon B, Ghnassia JC, Mack D, et al. Correlation between biofilm formation and production of polysaccharide intercellular adhesin in clinical isolates of coagulase-negative staphylococci. Int J Med Microbiol. (2006) 296(6):381–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2006.02.018

34. Weimer KED, Smith PB, Puia-Dumitrescu M, Aleem S. Invasive fungal infections in neonates: a review. Pediatr Res. (2022) 91(2):404–12. doi: 10.1038/s41390-021-01842-7

35. Melville JM, Moss TJ. The immune consequences of preterm birth. Front Neurosci. (2013) 7:79. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00079

36. Tessema B, Lippmann N, Knüpfer M, Sack U, König B. Antibiotic resistance patterns of bacterial isolates from neonatal sepsis patients at university hospital of Leipzig, Germany. Antibiotics (Basel). (2021) 10(3):323. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics10030323

37. Majigo M, Makupa J, Mwazyunga Z, Luoga A, Kisinga J, Mwamkoa B, et al. Bacterial aetiology of neonatal sepsis and antimicrobial resistance pattern at the regional referral hospital, Dar es Salam, Tanzania; a call to strengthening antibiotic stewardship program. Antibiotics (Basel). (2023) 12(4):767. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics12040767

38. Sorsa A, Früh J, Stötter L, Abdissa S. Blood culture result profile and antimicrobial resistance pattern: a report from neonatal intensive care unit (nicu), Asella teaching and referral hospital, Asella, south east Ethiopia. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. (2019) 8:42. doi: 10.1186/s13756-019-0486-6

39. Mhada TV, Fredrick F, Matee MI, Massawe A. Neonatal sepsis at muhimbili national hospital, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; aetiology, antimicrobial sensitivity pattern and clinical outcome. BMC Public Health. (2012) 12:904. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-904

40. Naccache SN, Callan K, Burnham CA, Wallace MA, Westblade LF, Dien Bard J. Evaluation of oxacillin and cefoxitin disk diffusion and microbroth dilution methods for detecting meca-mediated β-lactam resistance in contemporary staphylococcus epidermidis isolates. J Clin Microbiol. (2019) 57(12):e00961–19. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00961-19

41. Ardic N, Sareyyupoglu B, Ozyurt M, Haznedaroglu T, Ilga U. Investigation of aminoglycoside modifying enzyme genes in methicillin-resistant staphylococci. Microbiol Res. (2006) 161(1):49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2005.05.002

42. Salman O, Procter SR, McGregor C, Paul P, Hutubessy R, Lawn JE, et al. Systematic review on the acute cost-of-illness of sepsis and meningitis in neonates and infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. (2020) 39(1):35–40. doi: 10.1097/inf.0000000000002500

Keywords: neonatal sepsis, economic burden, hospital costs, length of stay, propensity score matching

Citation: Zhang B, Zhou P, Long Z, Wang Z, Gao L, Meng S, Xue F and Luan X (2025) Pathogen distribution, antimicrobial resistance and attributable cost analysis of neonatal sepsis in neonatal intensive care units: a propensity score matching study. Front. Pediatr. 13:1700766. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1700766

Received: 7 September 2025; Accepted: 7 November 2025;

Published: 19 November 2025.

Edited by:

Teresa Semedo-Lemsaddek, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Amresh Kumar Singh, Baba Raghav Das Medical College, IndiaMaria Livia Ognean, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania

Copyright: © 2025 Zhang, Zhou, Long, Wang, Gao, Meng, Xue and Luan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaorong Luan, MTk5MTYyMDAwODE0QHNkdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Bingyan Zhang1,†

Bingyan Zhang1,† Peiyun Zhou

Peiyun Zhou Xiaorong Luan

Xiaorong Luan