- Mianyang Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Mianyang, China

Introduction: Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have emerged as a globally recognized public health concern. Currently, discrete trial teaching (DTT) is an effective intervention approach for ASD rehabilitation in hospitals. However, family-based interventions often yield limited outcomes. This study aims to develop a hospital-family collaborative DTT program guided by King's goal attainment theory, to support parents in delivering continuous and effective intervention within home environments.

Method: This single-blind randomized controlled study included 84 children with ASD aged 1 to 6 years. Participants were stratified by gender and age and randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n = 42) or the control group (n = 42) using a random number table. The experimental group received a hospital-family collaborative DTT program, consisting of one month of hospital intervention followed by three months of family-based intervention, while the control group received standard DTT rehabilitation. Outcomes were assessed using the Gesell Developmental Schedules (GESELL), Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF), Family Assessment Device (FAD), along with DTT theoretical and skill evaluations.

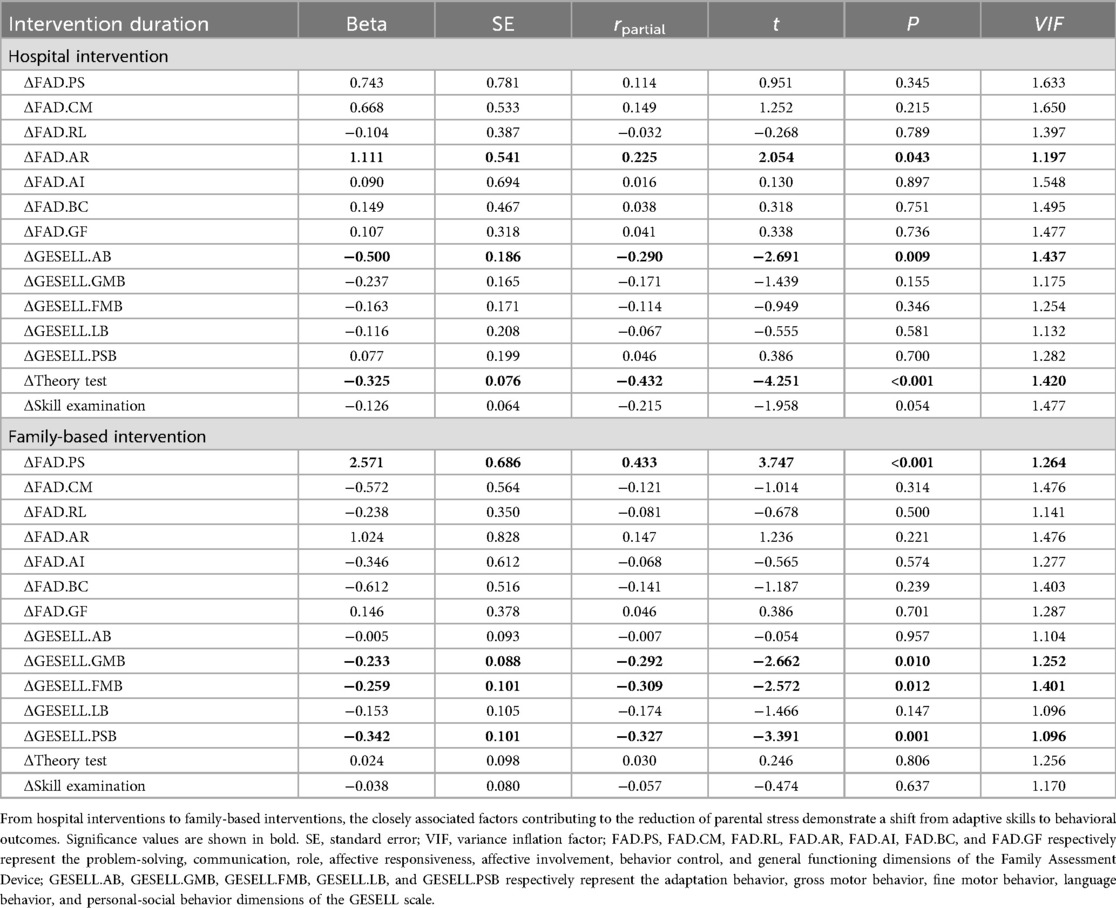

Results: Except that the PSI scores were unaffected by the intervention method, the GESELL, PSI, FAD, theoretical, and skill scores were significantly influenced by both intervention time (F = 37.70–896.12, all P < 0.001), intervention method (F = 37.70–896.12, all P < 0.001), and their interaction (F = 5.83–75.27, all P < 0.01). Partial correlation analysis revealed that improvements in parenting stress were initially linked to changes in “adaptive” items on the GESELL and FAD scales during the hospital intervention phase (Δ FAD. affective reaction: rpartial = 0.225, P = 0.043; Δ GESELL. adaptation behavior: rpartial = −0.290, P = 0.009; Δ parental knowledge: rpartial = −0.432, P < 0.001), followed by improvements in “behavioral” items during the family-based intervention phase (ΔFAD. problem-solving: rpartial = 0.433, P < 0.001; ΔGESELL. gross motor behavior: rpartial = −0.292, P = 0.010; ΔGESELL. fine motor behavior: rpartial = −0.309, P = 0.012; ΔGESELL. personal-social behavior: rpartial = −0.327, P = 0.001). For all participants, extremely high levels of parenting stress were independently associated with FAD disorders (particularly in problem-solving, affective responsiveness, and affective involvement), child factors (including male, language disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder), caregiver factors (including male, lower education level, and unversed DTT skills), as well as conventional DTT programs and shorter intervention durations (all P < 0.05).

Discussion: Our hospital-family collaborative DTT program significantly improved children's ASD symptoms, family function, and parenting stress, demonstrating the value of ongoing family-based DTT intervention. The improvements in children's symptoms and family function showed a time-dependent shift from adaptive to behavioral changes, which were linked to lower parental stress.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are a neurodevelopmental disorder primarily characterized by social communication impairments, repetitive stereotyped behaviors, and sensory perception abnormalities (1). In recent years, the prevalence of ASD has been steadily rising, and it has now become a widely recognized public health concern globally, placing a significant burden on both families and society. The latest data from the United States show that ASD incidence has increased from 1 in 45 to 1 in 36 (2, 3). In China, surveys indicate that about 0.7% of children have autism, making it the most common mental disability among children (4). There are currently no effective drugs for ASD; rehabilitation training remains the primary intervention (5), often requiring long-term or lifelong commitment and significant costs (6). As a result, parents not only have to confront the abnormal behaviors of children with ASD, but also have to bear multiple pressures and challenges on family life (7). Moreover, parents of ASD children experience higher stress levels compared to those with other disabilities like Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, or intellectual disabilities (8), which also negatively affect the rehabilitation interventions.

As the prevalence of ASD continues to rise, its rehabilitation strategies have become a top focus (9). Discrete trial teaching (DTT) is widely recognized as an effective intervention for children with ASD. This approach incorporates the core principles of applied behavior analysis (10) to break down training objectives into manageable steps and teach and strengthen the mastery of targeted skills through four simple and repetitive ways: instruction, response, outcome, and pause. Repeat these steps and adjust as needed until the trainees master the intended skills (11). Numerous studies have shown that DTT can significantly improve the social, self-care, and cognitive skills of children with ASD, reduce problem behaviors, and enhance social adaptability, thereby promoting overall development (12–14). However, most existing evidence focuses on short-term interventions conducted in clinical settings. There is limited empirical support for how to transform hospital-based DTT into continuous family-based interventions and integrate professional practices with daily life (15). Therefore, more research is needed to explore the family generalization and long-term maintenance of DTT intervention measures.

To achieve an effective implementation effect of family-based DTT interventions, the focus should be on how well family members master DTT measures. King's goal achievement theory, developed by American nursing theorist Imogene M. King, is a conceptual framework that emphasizes interpersonal interactions to achieve shared goals. As a patient-centered nursing theory, it can promote physical well-being through dynamic exchanges between nurses and patients. The theory encourages mutual goal-setting and active participation from both parties to achieve effective care outcomes (16). Due to its emphasis on prioritizing patients' perspectives, fostering interactive communication, and progressing incremental education, it has proven effective in improving self-management among patients with chronic conditions like diabetes, myocardial infarction, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (17–19). Yet, it has not been applied to ASD management or family caregiving education.

A meta-analysis and systematic review have confirmed that the current family-based interventions for ASD remain suboptimal, suggesting the need to incorporate professional skills into daily family interventions (20, 21). To more effectively reduce ASD symptoms, ease family financial and emotional burdens, and fill the gap in clinical evidence, this study integrates King's goal achievement theory with DTT teaching to support parents in delivering consistent, effective interventions in daily life.

Method

Ethical review

This study was a single-blind randomized controlled trial, and registered in the National Universal Health Security Platform (Registration No.: MR-51-25-036154, Date: May 12, 2025). The study followed the 2013 revised Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Mianyang Central Hospital (Approval No.: S20250313-01, Date: Feb. 12, 2025). All parents of children with ASD signed informed consent.

Participants

During March 2025 to July 2025, a total of 84 children with ASD and their primary caregivers were recruited from the Department of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics in Mianyang Central Hospital School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Child aged 1 to 6 years, accompanied by primary caregiver aged 20 to 65 years; (2) Child who were firstly diagnosed with ASD from a specialist physician, based on the diagnostic criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (22); (3) Primary caregiver who had no mental disorders and could communicate normally; (4) Parent and primary caregiver were willing to participate in the study and had provided written informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Child or primary caregiver had other serious diseases, such as serious behavioral disorder, mutism, Tic disorder, and epilepsy; (2) Child and/or primary caregiver had recently received other forms of systematic rehabilitation training; (3) Child was unable to cooperate, or primary caregiver lacked sufficient language proficiency to understand DTT instructions; (4) child who receive any form of therapy other than DTT during the study period.

According to a pre-prepared random number table stratified by gender (male and female) and age (1–3 years and 4–6 years), children and their primary caregivers were assigned to either the control group or the experimental group, following the order of their visits. Based on the research design, the sample size was estimated using the repeated measures module in PASS software. With a significance level (α) set at 0.05 and statistical power (1−β) set at 90% (β = 0.10), and incorporating the Huynh-Feldt and Greenhouse-Geisser corrections to account for potential violations of sphericity, the minimum required sample size per group was determined to be 28 participants. To accommodate an anticipated dropout rate of 30%, the adjusted sample size per group was calculated to be at least 37 participants.

Comparative implementation of conventional and collaborative DTT training

Establishment of two independent DTT intervention teams

Each comprised three members, including one developmental and behavioral pediatrician and two ASD specialist nurses. Each team received training on the DTT intervention, delivered either in the conventional mode or through the hospital-family program. The pediatrician was responsible for conducting the ASD diagnosis and initial evaluation, developing the DTT intervention plan with parents, and supervising the subsequent follow-up visits. Specialist nurses were responsible for conducting comprehensive evaluations of developmental level and disorder severity, assisting pediatricians to design personalized rehabilitation plans with primary caregivers, training primary caregivers in DTT intervention skills, and providing guidance for family-based DTT rehabilitation after discharge. Each team was allocated an independent diagnostic room and a dedicated rehabilitation training room to minimize cross-group interference. Appropriate teaching materials and assistive tools were provided within the dedicated rehabilitation room. Additionally, a shared supervision nurse, who remained blinded to the group allocation, was responsible for evaluating the DTT skill proficiency of primary caregivers and collecting scale-based survey data regarding the rehabilitation outcomes.

Conventional training program for the control group

Specialized nurses conducted a one-month hospital DTT intervention, and primary caregivers implemented three-month daily DTT exercises after in-class autonomous learning. During the hospital DTT intervention, a rehabilitation plan is jointly formulated by specialist nurses and a specialist doctor following a comprehensive assessment of the child's developmental level as well as the severity of social, language, and behavioral impairments. Subsequently, specialist nurses conducted one-on-one DTT sessions for children with ASD five days per week, with each session lasting 45 min. DTT training broke down targeted skills into small, manageable steps and delivered them through a structured instructional approach. Specific reinforcers, such as toys or snacks, were selected based on individual children's preferences to enhance their engagement and motivation during the learning process. Meanwhile, the specialist nurses provided in-class training and guidance to parents on DTT skills, covering how to break down training steps, formulate instructions, select and use reinforcers, and provide and adjust appropriate assistance. After the hospital intervention ended, primary caregivers continued the family-based DTT intervention in daily situations using the skills they learned in the hospital. Meanwhile, a nurse-caregiver WeChat group was created to support remote question-and-answer sessions. The family-based DTT intervention lasted three months, followed by a required outpatient follow-up visit.

King interactive achievement program for the experimental group

Based on the conventional DTT program for the control group, the King interactive attainment system was integrated to establish a hospital-family collaborative program. During the hospital DTT intervention, pediatricians, specialist nurses, and parents collaboratively developed a stepwise rehabilitation plan after thoroughly completing a comprehensive assessment of the child's condition and gathering relevant information (including parental personality, age, cultural background, family support, psychological characteristics, understanding of disease-related knowledge, and living environment). Subsequently, specialist nurses delivered DTT courses to children with ASD and their primary caregivers at the same frequency and duration.

During the first five days of hospital intervention, primary caregivers received 45 min training sessions each day, including two days of theory and three days of practice. Theoretical teaching encompassed key components such as task breakdown, instruction delivery, reinforcer selection and use, appropriate assistance provision, and determination of assistance levels. Practical training was conducted through one-on-one demonstrations by specialized nurses to enhance caregivers' proficiency in DTT skills. Meanwhile, a pediatrician-nurse-caregiver WeChat group was created to support remote question-and-answer sessions. Additionally, the pediatrician shared several rehabilitation training courses within the WeChat group to enhance caregivers' understanding of rehabilitation and to support the development of their intervention skills. These courses included topics such as “Children's Related Behaviors and Descriptions”, “Basic Knowledge of ASD and Analysis of Common Problem Behaviors”, and “Functional Games for Children with ASD”.

Near the end of the hospital intervention, the pediatrician, nurses, and caregivers formulated a family-based DTT rehabilitation plan together. During the home intervention, caregivers uploaded weekly videos to the WeChat group, showing the implementation of DTT in daily routines. Based on the rehabilitation condition, nurses adjusted the plan promptly and guided caregivers in conducting progressive rehabilitation training. Near the end of the hospital intervention, doctors, nurses, and parents jointly formulated a family DTT rehabilitation plan. During the family intervention period, the main caregiver uploaded videos of implementing DTT in daily situations to the WeChat group every week. The specialist nurse promptly adjusted the rehabilitation plan according to the child's rehabilitation progress and guided the caregivers to carry out progressive rehabilitation training. Additionally, caregivers were encouraged to share their experiences to enhance their confidence throughout the family-based rehabilitation process.

Investigation and evaluation of intervention effects

The survey content included the Gesell Developmental Schedules (GESELL), Family Assessment Device (FAD), Parenting Stress Index Short Form (PSI-SF), as well as the ASD theoretical examination and DTT skill assessment. The first three scales were investigated before intervention, one month after hospital intervention, and three months after family-based intervention. The ASD theoretical examination and DTT skill assessment were conducted at one week into hospital intervention, one month after hospital intervention, and three months after family-based intervention. Except for the pre-intervention GESELL assessment conducted by a specialist nurse, all other assessments were performed by the shared supervision nurse who remained blinded to the group allocation. At the time of pre-intervention GESELL assessment, the specialist nurse recorded the sociodemographic characteristics of the children and their primary caregivers, including the caregivers' gender, age, kinship, educational level, occupation, monthly family income, as well as the children's gender, physical age, age at diagnosis, and accompanying symptoms.

The GESELL scale was used to evaluate children's developmental levels across five dimensions: adaptation behavior, gross motor behavior, fine motor behavior, language behavior, and personal-social behavior, encompassing a total of 97 items. For each dimension, the developmental quotient (DQ) was calculated based on the child's performance using the formula: developmental age/chronological age × 100. Developmental Age refers to the age level that corresponds to the child's observed developmental stage. A DQ score of each dimension above 85 was considered within the normal developmental range, 76–85 indicated a borderline state, 55–75 indicated mild developmental delay, 40–54 indicated moderate developmental delay, and <40 indicated severe developmental delay. The Cronbach's α coefficient of five dimensions was reported as 0.85 to 0.95 (23).

The FAD scale comprised 60 items distributed across seven dimensions: problem-solving (6 items), communication (9 items), role (11 items), affective responsiveness (6 items), affective involvement (7 items), behavior control (9 items), and general functioning (12 items). Each item was rated on a 4-Likert scale, ranging from 1 (completely agree) to 4 (completely disagree) for positive items, while 1 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree) for negative items. Higher scores indicated poorer family functioning. The Cronbach's α coefficients for the scale range from 0.78 to 0.86 (24).

The PSI-SF scale comprised three dimensions: parental distress, parenting difficulty, and difficult child, each consisting of 12 items. Each item was rated on a 5-Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with higher total scores indicating higher levels of parenting stress. The level of parenting stress was classified into four categories: a total score of ≤85, 86–90, 91–98, and ≥99 indicated normal, borderline, high, and very high stress, respectively. This scale demonstrated strong internal consistency, with reliability coefficients exceeding 0.90, which reflects good reliability and validity (25).

Caregivers' mastery of DTT was evaluated through a self-made theoretical test (including single-choice, multiple-choice, and case analysis) and operational assessment, both scored out of 100.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was processed using SPSS v25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MedCalc v22.021 software (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium). Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The inter-group differences at the same time point were analyzed using the independent sample t-test (if equal variance) or Welch t-test (if unequal variance). For comparisons of inter-group differences across multiple time points, repeated measures ANOVA was employed, and the adjusted P-value for the effect value was determined by the Huynh-Feldt correction (if epsilon > 0.75) or the Greenhouse-Geisser correction (if epsilon < 0.75). Count data were expressed as frequency (percentage), and the inter-differences were compared using the Chi-square test. The significance level was set at α = 0.05 for two-tailed hypothesis testing.

Result

The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

The sociodemographic characteristics of 84 children with ASD and their caregivers are listed in Table 1. No statistically significant differences were observed in any of these characteristics between the experimental and control groups (all P > 0.05).

Comparison of GESELL, PSI-SF, and FAD scores between the two intervention groups

The inter-group difference analysis at the same time point showed (Table 2): Before the intervention, except for the AR dimension scores, no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in the total scores and dimension scores of GESELL, PSI-SF, and FAD scales (all P > 0.05). At one month after hospital intervention, statistically significant differences emerged between the two groups in the total scores and GMB, FMB, and PSB dimension scores of GESELL scale (t = −3.33 to −4.42, all P < 0.01), as well as in the total scores and CM, RL, AR, AI, and BC dimension scores of FAD scale (t = 2.81 to 4.24, all P < 0.01). At three months after family-based intervention, except for the LB dimension scores, statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in the total scores and dimension scores of GESELL, PSI-SF, and FAD scales (all P < 0.05).

Table 2. The GESELL, PSI-SF and FAD scores before intervention, during in-hospital intervention (the first month) and during home intervention (the third month).

The repeated measures ANOVA analysis revealed (Table 2): During the hospital-family collaborative intervention, the total scores and AB, GMB, FMB, and PSB dimension scores of GESELL scale were affected by the intervention method (F = 5.71 to 31.96, all P < 0.05), as well as the total scores and CM, RL, AR, AI, and BC dimension scores of FAD scale (F = 5.02–13.97, all P < 0.05); the total scores and each dimension scores of GESELL, PSI-SF, and FAD were all affected by the intervention duration (F = 37.70 to 896.12, all P < 0.001); except for the LB and PSB dimension scores, the total scores and each dimension scores of GESELL, PSI-SF, and FAD were also affected by the interaction of intervention method and duration (F = 5.83 to 75.27, all P < 0.01).

Comparison of theoretical and operational scores between the two intervention groups

The inter-group difference analysis at the same time point showed (Figure 1): Before the intervention, there were no statistically significant differences in the theoretical or operational scores between the two groups (t = 0.29 and 1.30, P = 0.769 and 0.198). Following one month of hospital intervention and three months of family-based intervention, both the theoretical and operational scores of the control group were significantly lower than those of the experimental group (t = −7.29 to −10.21, all P < 0.001). The repeated measures ANOVA analysis revealed that the intervention method (F = 53.56 and 52.92), duration (F = 269.88 and 96.59), and interaction between intervention method and duration (F = 33.91 and 40.68) all had significant impacts on theoretical and operational scores.

Figure 1. The theoretical and operational scores of the two intervention groups. (A) Theory test; (B) Skill examination. Con, the control group; Exp, the experimental group. There were no inter-group differences in theoretical and operational scores before the intervention, but differences emerged after the hospital intervention and persisted following three months of family-based intervention. The intervention method, duration, and their interaction all impacted on theoretical and operational scores.

Relationship between PSI-SF improvement and other evaluation improvements during hospital intervention and family-based intervention

We calculated the changes in scores for each scale and test in both the hospital and family-based interventions. For the hospital intervention, the score change was calculated as the difference between the hospital score and the pre-intervention score. For the family-based intervention, the score change was calculated as the difference between the family-based score and the hospital score. Using the PSI-SF score change as the dependent variable, and the score changes in each GESELL dimension, each FAD dimension, theory, and skill as covariates, the enter-method linear regression and partial correlation analysis revealed (Table 3): During hospital intervention, the ΔPSI-SF scores were positively correlated with those of ΔFAD.AR (affective reaction) (rpartial = 0.225, P = 0.043), while negatively correlated with those of ΔGESELL1.AB (adaptation behavior) and ΔTheory test (rpartial = −0.290 and −0.432, P = 0.009 and <0.001). During family intervention, the ΔPSI-SF scores were positively correlated with those of ΔFAD.PS (problem-solving) (rpartial = 0.433, P < 0.001), while negatively correlated with those of ΔGESELL gross motor behavior, ΔGESELL fine motor behavior, and ΔGESELL personal-social behavior (rpartial = −0.292, −0.309, and −0.327, P = 0.010, 0.012, and 0.001). All significances were confirmed by the stepwise method analysis. These findings suggest that moving from hospital to family-based interventions, the focus for children with ASD shifted from adaptive skills to behavioral outcomes, which significantly helped reduce parenting stress.

Table 3. Changes in PSI-SF scores in relation to changes in other evaluations during hospital and family-based interventions.

Independent influencing factors of parenting stress degree

Finally, we summarized the three survey data. Using the PSI degree as the dependent variable, and incorporating other evaluation outcomes, the sociodemographic characteristics of children and their caregivers, along with the intervention method and duration as covariates, the stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted (Table 4). Compared with normal degree PSI, male patient with language disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, male caregiver and his/her lower education, conventional DTT, and short intervention duration (pre-intervention and hospital intervention) were risk factors for very high degree PSI group (OR = 3.586 to 41.791, all P < 0.05), while higher scores in DTT skill, FAD.PS (problem-solving), FAD.AR (affective responsiveness) and FAD.AI (affective involvement) were protective factors for the very high degree PSI group (OR = 0.534 to 0.892, all P < 0.05). For the high degree PSI group, the effects of all aforementioned factors were attenuated, as indicated by no significant effects of DTT skill, FAD4.AR, and language disorder (all P > 0.05), as well as the diminished risk effects (OR = 4.112 to 27.450, all P < 0.05) or protective effects (OR = 0.688 and 0.705, both P < 0.05) of the remaining factors. No significant influencing factors were found in the borderline degree PSI group (all P > 0.05).

Discussion

Although DTT intervention has been shown to significantly improve symptoms in children with ASD, family-based continuation interventions remain less effective (20, 21). This study aimed to develop a hospital-family collaborative DTT program based on King's goal attainment theory, to enhance caregivers' ability to continue interventions and assess its impact on ASD symptoms and family functioning. Our findings revealed a significant improvement in caregivers' skills through the hospital-family collaborative DTT program, which contributed to sustained benefits in children's ASD symptoms, family functioning, and a reduction in parenting stress. Specifically, during the hospital intervention phase, the program significantly extended caregivers' theoretical knowledge of ASD and improved parental affective responsiveness and children's adaptation behavior to reduce parenting stress; subsequently, in the family-based phase, improvements in parental problem-solving skills and children's gross motor behavior, fine motor behavior, and personal-social behavior further reduced parenting stress. The two-phase intervention illustrated a transition from “adaptive” to “behavioral” improvements in children's symptoms and family functioning, highlighting the critical role of family-based DTT intervention in the treatment process for children with ASD. Further influencing factor analysis revealed that parenting stress was impacted by child-related factors (including gender, language disorder, and ADHD), caregiver-related factors (including gender, education, and DTT skill), family functioning (including problem-solving, affective responsiveness, and affective involvement abilities), intervention approach, and intervention duration.

Our hospital-family collaborative DTT program is developed based on the King's goal attainment theory. This theory includes three levels: individual, interpersonal, and social systems. During the healthcare process, greater emphasis is placed on patients' active involvement in health management and their interaction with nurses, fostering mutual influence and collaborative efforts to achieve rehabilitation goals (26). At the individual system level, DTT, an intervention grounded in behavior analysis, can effectively enhance perceptual-motor integration in children with ASD through structured and repetitive training. This approach facilitates the establishment of stable learning patterns and improvement in core symptoms (12). At the interpersonal system level, parents who master core skills through interactive attainment learning can implement DTT training more accurately, improving parent-child interactions and clarifying family roles and communication. The active participation of family members can enhance overall family functioning, ensure the success of family-based interventions, and thus sustain the effects of the DTT intervention. At the social system level, ongoing guidance and support from medical professionals can provide families with essential resources. Professional involvement goes beyond traditional family-based interventions by offering parents reliable technical help and emotional support. Ultimately, this hospital-family collaboration successfully eases parental stress and anxiety during interventions.

Our program can effectively reduce parenting stress by improving ASD core symptoms in children and enhancing family functioning. Evidence supporting this conclusion includes: (1) consistently lower GESELL, FAD, and PSI-SF scores in the experimental group compared to the control group during intervention; (2) significant independent influence of increased caregivers' DTT skills on reducing parental stress levels; and (3) notable antagonistic effect of hospital-family collaboration program on both high and extremely high levels of parental stress. Overall, these findings support the effectiveness of the intervention program. Noteworthily, the intervention effect showed a clear time-dependent trend. With the successive implementation of hospital and family-based interventions, parental stress gradually decreased. Repeated measures ANOVA also revealed a significant effect of intervention time on the GESELL, PSI-SF, and FAD scores, as well as a significant interaction effect between method and time on most dimensions except for the LB and PSB dimensions. These findings further suggest that the hospital-family collaboration DTT program has advantages in treating children with ASD, and that integrating professional guidance with family-based intervention improves parental caregiving capabilities.

As the hospital and family-based interventions were successively implemented, the crucial factor influencing parenting stress shifted from “adaptive” to “behavioral” improvements in the child's symptoms and family functioning. During the hospital intervention phase, increased parenting stress was positively linked to the decline in affective responsiveness within the family. Affective responsiveness refers to the emotional reactions of family members to external stimuli (27), whose deterioration may be linked to parents' first learning how to identify and respond to their autistic children's emotional signals. Parents not only require greater cognitive and emotional engagement to acquire new skills, but they also often experience concerns about whether their emotional responses meet professional expectations when participating in the structured interventions, commonly referred to as evaluation anxiety. These findings highlight the importance of including psychological support for parents during the hospital intervention phase to reduce negative emotions linked to professional skill acquisition. Consistent with previous studies (28), improvements in children's adaptation behaviors and parents' knowledge of ASD were negatively correlated with increased parenting stress. Improving children's adaptive behaviors can reduce parental care burdens, alleviate objective stressors, and potentially mitigate the cascading effects of problem behaviors between parents and children. Meanwhile, parents' understanding of ASD intervention theories helps them better grasp their children's problem behaviors and avoid blaming themselves for parenting failures. Overall, during the hospital intervention phase, improvements in both children and their families reflected their ability to actively adapt to ASD treatment, which was closely linked to reduced parenting pressure.

Unlike the hospital intervention phase, the factors influencing the reduction in parental stress shifted from “adaptive” to “behavioral” improvements during the family-based intervention phase. Improvements in children's behavioral indicators (gross motor behavior, fine motor behavior, and personal-social behavior) were negatively correlated with increased parenting stress. As gross and fine motor behaviors develop, children become more independent, reducing the need for daily parental assistance. Development in personal-social behavior can enhance parent-child communication and ease frustration from social difficulties, effectively lowering parenting stress. Overall, better motor and social skills reduced children's problem behaviors, increased parental confidence, and strengthened rehabilitation motivation. Meanwhile, the deterioration of problem-solving ability in family functioning was also found to be linked to the increase in parenting stress. Problem-solving ability refers to a family's capacity to handle challenges that could affect its structure and function. A higher PS score indicates lower problem-solving ability, which may increase parenting stress. Our findings underscore the relevance of parental problem-solving abilities in reducing parenting stress. Without professional support to enhance parental DTT skills, they may encounter greater difficulties in addressing child-rearing challenges. Therefore, professional institutions should provide psychological support and technical guidance to families in order to implement effective family-based interventions. Strategies such as structured play and sport activities can facilitate the healthy development of children with ASD and contribute to the establishment of a positive parenting cycle.

Finally, our study revealed the independent factors influencing parenting stress, such as family dysfunction (specifically, problem-solving, affective responsiveness, and affective involvement abilities), child-related factors (including gender, language disorder, and ADHD), caregiver-related factors (including gender, education, and DTT skills), intervention method, and duration. As protective factors: (1) the intervention strategy based on King's goal attainment theory and improved parental DTT skills reaffirms the effectiveness of our hospital-family collaborative intervention; and (2) among family functioning factors, problem-solving ability helps families manage challenges during intervention, and affective responsiveness and involvement can enhance empathy and mutual support among family members (29), reducing accumulated conflict. As risk factors: (1) male children often show more externalizing behaviors like aggression and hyperactivity (30); (2) language disorder or ADHD can worsen communication and behavior challenges (31); (3) male caregivers may feel more stress due to social roles and emotional regulation differences; and (4) caregivers with less education often face limited access to resources and difficulties in implementing interventions. These factors may contribute to increased parenting stress. Therefore, intervention plans should address both children's developmental needs and family psychological support. It is important to use hospital-family collaboration instead of a single hospital intervention, extend the intervention duration to ensure the optimized effects; and family-based intervention should enhance parental emotional interaction and problem-solving skills to support both children's improvement and family adaptation.

Conclusions

This study is the first to apply a DTT intervention based on King's goal attainment theory within a hospital-family collaboration framework. It shows promising results in improving core symptoms in children with ASD and family functioning, thus lowering parenting stress. The DTT teaching emphasized to primary caregivers during the in-hospital intervention phase, served as a critical foundation for effective ongoing family-based training. Simultaneously, Specialized nurses played a key role by expanding caregivers' ASD knowledge, enhancing their DTT skills, offering psychological support, and evaluating children's outcomes.

However, several limitations exist. First, as a small-sample, single-center study, the findings require further validation through larger sample sizes, multicenter investigations, and diverse racial and ethnic populations to minimize potential biases. Second, a three-month short-term family intervention yielded only immediate improvements, whereas sustained long-term effects necessitate extended follow-up periods. Third, certain individual and contextual factors related to parenting styles are not examined in this study, which may introduce potential bias.

Despite these limitations, the findings highlight the value of ongoing family involvement in DTT and provide useful insights for enhancing health management for children with ASD. Future long-term follow-up validation is recommended to better assess the effectiveness and applicability of this hospital-family collaboration DTT intervention.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Medical Ethics Committee of Mianyang Central Hospital. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardians/next of kin.

Author contributions

MD: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. JL: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. XC: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. LC: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. XT: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. HY: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. YQ: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization. YY: Writing – review & editing, Conceptualization.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was financially supported by the Social Science Circles Federation of Zi gong [YXJKCB-2024-07]. The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization apart from those disclosed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Iles A. Autism Spectrum disorders. Prim Care. (2021) 48(3):461–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2021.04.003

2. Maenner MJ, Shaw KA, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Durkin MS, Esler A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2021) 70(11):1–16. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1

3. Maenner MJ, Warren Z, Williams AR, Amoakohene E, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. (2023) 72(2):1–14. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss7202a1

4. Zhou H, Xu X, Yan W, Zou X, Wu L, Luo X, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder in China: a nationwide multi-center population-based study among children aged 6 to 12 years. Neurosci Bull. (2020) 36(9):961–71. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00530-6

5. Lord C, Elsabbagh M, Baird G, Veenstra-Vanderweele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Lancet. (2018) 392(10146):508–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31129-2

6. Hirota T, King BH. Autism spectrum disorder: a review. JAMA. (2023) 329(2):157–68. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.23661

7. van Niekerk K, Stancheva V, Smith C. Caregiver burden among caregivers of children with autism spectrum disorder. S Afr J Psychiatr. (2023) 29:2079. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v29i0.2079

8. Patel AD, Arya A, Agarwal V, Gupta PK, Agarwal M. Burden of care and quality of life in caregivers of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. (2022) 70:103030. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103030

9. Vivanti G. What does it mean for an autism intervention to be evidence-based? Autism Res. (2022) 15(10):1787–93. doi: 10.1002/aur.2792

10. Anderson LK. Autistic experiences of applied behavior analysis. Autism. (2023) 27(3):737–50. doi: 10.1177/13623613221118216

11. Gitimoghaddam M, Chichkine N, McArthur L, Sangha SS, Symington V. Applied behavior analysis in children and youth with autism spectrum disorders: a scoping review. Perspect Behav Sci. (2022) 45(3):521–57. doi: 10.1007/s40614-022-00338-x

12. Stone-Heaberlin M, Hartley N, Lynch JD, Fisher AP, Justice N. Implementation of a parent-mediated discrete trial teaching intervention for children with autism spectrum disorder. Behav Anal Pract. (2022) 16(1):302–6. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00735-3

13. Briggs AM, Zohr SJ, Harvey OB. Training individuals to implement discrete-trial teaching procedures using behavioral skills training: a scoping review with implications for practice and research. J Appl Behav Anal. (2024) 57(1):86–103. doi: 10.1002/jaba.1024

14. Ferguson JL, Cihon JH, Majeski MJ, Milne CM, Leaf JB, McEachin J, et al. Toward efficiency and effectiveness: comparing equivalence-based instruction to progressive discrete trial teaching. Behav Anal Pract. (2022) 15(4):1296–313. doi: 10.1007/s40617-022-00687-8

15. Bravo A, Schwartz I. Teaching imitation to young children with autism spectrum disorder using discrete trial training and contingent imitation. J Dev Phys Disabil. (2022) 34(4):655–72. doi: 10.1007/s10882-021-09819-4

16. Hadi F, Molavynejad S, Elahi N, Haybar H, Maraghi E. King’s theory of goal attainment: quality of life for people with myocardial infarction. Nurs Sci Q. (2023) 36(3):250–7. doi: 10.1177/08943184231169771

17. Araújo ESS, Silva LFD, Moreira TMM, Almeida PC, Freitas MC, Guedes MVC. Nursing care to patients with diabetes based on King’s theory. Rev Bras Enferm. (2018) 71(3):1092–8. (In Portuguese, English). doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0268

18. Yan M, Yu Y, Li S, Zhang P, Yu J. Effectiveness of King’s theory of goal attainment in blood glucose management for newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. (2024) 26:e59142. doi: 10.2196/59142

19. Yang H, Luo W, Du X, Guan Y, Peng W. The implementation and effect evaluation of AIDET standard communication health education mode under the king theory of goal attainment: a randomized control study. Medicine. (2023) 102(48):e36083. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000036083

20. Crowell JA, Keluskar J, Gorecki A. Parenting behavior and the development of children with autism spectrum disorder. Compr Psychiatry. (2019) 90:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.11.007

21. Althoff CE, Dammann CP, Hope SJ, Ausderau KK. Parent-mediated interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. (2019) 73(3):7303205010p1–7303205010p13. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2019.030015

22. Losada-Puente L, Baña M, Asorey MJF. Family quality of life and autism spectrum disorder: comparative diagnosis of needs and impact on family life. Res Dev Disabil. (2022) 124:104211. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2022.104211

23. Li JH, Zhao JZ, Hua L, Hu XL, Tang LN, Yang T, et al. Efficacy of children neuropsychological and behavioral scale in screening for autism spectrum disorders through a combination of developmental surveillance. Curr Med Sci. (2023) 43(3):592–601. doi: 10.1007/s11596-023-2698-5

24. Pedersen MAM, Kristensen LJ, Sildorf SM, Kreiner S, Svensson J, Mose AH, et al. Assessment of family functioning in families with a child diagnosed with type 1 diabetes: validation and clinical relevance of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster family assessment device. Pediatr Diabetes. (2019) 20(6):785–93. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12866

25. Luo J, Wang MC, Gao Y, Zeng H, Yang W, Chen W, et al. Refining the parenting stress index-short form (PSI-SF) in Chinese parents. Assessment. (2021) 28(2):551–66. doi: 10.1177/1073191119847757

26. Fronczek AE. Ushering in a new era for King’s conceptual system and theory of goal attainment. Nurs Sci Q. (2022) 35(1):89–91. doi: 10.1177/08943184211051373

27. Mansfield AK, Keitner GI, Dealy J. The family assessment device: an update. Fam Process. (2015) 54(1):82–93. doi: 10.1111/famp.12080

28. Zhou B, Xu Q, Li H, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Rogers SJ, et al. Effects of parent-implemented early start denver model intervention on Chinese toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: a non-randomized controlled trial. Autism Res. (2018) 11(4):654–66. doi: 10.1002/aur.1917

29. Du Y, Liu J, Lin R, Chattun MR, Gong W, Hua L, et al. The mediating role of family functioning between childhood trauma and depression severity in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. (2024) 365:443–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.155

30. Leeman J, Crandell JL, Lee A, Bai J, Sandelowski M, Knafl K. Family functioning and the well-being of children with chronic conditions: a meta-analysis. Res Nurs Health. (2016) 39(4):229–43. doi: 10.1002/nur.21725

Keywords: autism spectrum disorders, child, caregiver, gesell developmental schedules, parenting stress index, family assessment device (FAD)

Citation: Dai M, Li J, Chen X, Chen L, Tang X, Yu H, Qiu Y and Yang Y (2025) Hospital-family collaborative DTT intervention to reduce the parenting stress through improving core symptoms and family functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Front. Pediatr. 13:1708217. doi: 10.3389/fped.2025.1708217

Received: 18 September 2025; Revised: 27 October 2025;

Accepted: 21 November 2025;

Published: 5 December 2025.

Edited by:

Aparecido José Couto Soares, Federal University of São Paulo, BrazilReviewed by:

Amanda Tragueta Ferreira-Vasques, University of Sorocaba, BrazilTelma Pantano, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Brazil

Copyright: © 2025 Dai, Li, Chen, Chen, Tang, Yu, Qiu and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuwei Yang, eXl3MzE4QHNjLW1jaC5jbg==; Yun Qiu, MTYwNjU4NTgwM0BxcS5jb20=

These authors have contributed equally to this work

Mengqin Dai

Mengqin Dai Juan Li†

Juan Li† Yuwei Yang

Yuwei Yang