Abstract

Cinquefoils have been widely used in local folk medicine in Europe and Asia to manage various gastrointestinal inflammations and/or infections, certain forms of cancer, thyroid gland disorders, and wound healing. In the present paper, acetone extracts from aerial parts of selected Potentilla species, namely P. alba (PAL7), P. argentea (PAR7), P. grandiflora (PGR7), P. norvegica (PN7), P. recta (PRE7), and the closely related Drymocalis rupestris (syn. P. rupestris) (PRU7), were analysed for their cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activities against human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 and human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN. Moreover, quantitative assessments of the total polyphenolic (TPC), total tannin (TTC), total proanthocyanidins (TPrC), total flavonoid (TFC), and total phenolic acid (TPAC) were conducted. The analysis of secondary metabolite composition was carried out by LC-PDA-HRMS. The highest TPC and TTC were found in PAR7 (339.72 and 246.92 mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE)/g extract, respectively) and PN7 (332.11 and 252.3 mg GAE/g extract, respectively). The highest TPrC, TFC, and TPAC levels were found for PAL7 (21.28 mg catechin equivalents (CAT)/g extract, 71.85 mg rutin equivalents (RE)/g extract, and 124.18 mg caffeic acid equivalents (CAE)/g extract, respectively). LC-PDA-HRMS analysis revealed the presence of 83 compounds, including brevifolincarboxylic acid, ellagic acid, pedunculagin, agrimoniin, chlorogenic acid, astragalin, and tiliroside. Moreover, the presence of tri-coumaroyl spermidine was demonstrated for the first time in the genus Potentilla. Results of the MTT assay revealed that all tested extracts decreased the viability of both cell lines; however, a markedly stronger effect was observed in the colon cancer cells. The highest selectivity was demonstrated by PAR7, which effectively inhibited the metabolic activity of LS180 cells (IC50 = 38 μg/ml), while at the same time causing the lowest unwanted effects in CCD841 CoN cells (IC50 = 1,134 μg/ml). BrdU assay revealed a significant decrease in DNA synthesis in both examined cell lines in response to all investigated extracts. It should be emphasized that the tested extracts had a stronger effect on colon cancer cells than normal colon cells, and the most significant antiproliferative properties were observed in the case of PAR7 (IC50 LS180 = 174 μg/ml) and PN7 (IC50 LS180 = 169 μg/ml). The results of LDH assay revealed that all tested extracts were not cytotoxic against normal colon epithelial cells, whereas in the cancer cells, all compounds significantly damaged cell membranes, and the observed effect was dose-dependent. The highest cytotoxicity was observed in LS180 cells in response to PAR7, which, in concentrations ranging from 25 to 250 μg/ml, increased LDH release by 110%–1,062%, respectively. Performed studies have revealed that all Potentilla species may be useful sources for anti-colorectal cancer agents; however, additional research is required to prove this definitively.

Introduction

The modern world struggles with the increasing problem of cancer, a significant cause of death worldwide. In 2020, the third most commonly diagnosed type of cancer after breast and lung cancers was colorectal cancer, estimated to represent 10.0% of total cancer cases and the second leading cause of cancer death (9.4% of total cancer deaths) (Sung et al., 2021). However, due to the Western lifestyle, which is closely associated with low physical activity, a high-fat diet, and high red meat consumption, the projected number of global new colorectal cancer cases will rise from 1.93 million in 2020 to 3.15 million cases in 2040 (Xi and Xu, 2021). Therefore, the economic burden of treatment and the high mortality rate of patients resulting from cancer recurrence after chemotherapy suggests a significant need for more efficient and safer drug candidates. However, access to the most effective and modern diagnostic methods and treatments is limited for a large proportion of people. Especially in rural areas, people predominantly still depend on phytotherapy (Edgar et al., 2007). Notably, Potentilla species, known as cinquefoils, are widely used, since they are well known in traditional medicine throughout the Asian and European continents as valuable phytomedicines in a remedy inter alia against diarrhoea, ulcers, fever, jaundice, oral inflammations, topical infections, and thyroid gland disorders (Tomczyk and Latte, 2009). Moreover, ancient Chinese medical works, in particular Compendium of Chinese Materia Medica and Mingyi Bielu mentioned that aerial parts of two Potentilla species, namely P. indica and Duchesnea chrysantha were used as anticancer agents in monotherapy or as a main ingredient of complex formulas against unspecified types of cancers (Peng et al., 2009). A number of studies have reported on the abundance of secondary metabolites in Potentilla species, which determine their anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and antioxidative properties (Augustynowicz et al., 2021b). Moreover, earlier studies on several Potentilla species have shown their anti-cancer potential against various cell lines, e.g., triterpenoids isolated from P. chinensis were cytotoxicity against MCF7 (human breast cancer), Hep G2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) and T84 (human colonic adenocarcinoma), while extracts and fractions from aerial parts of P. alba decreased proliferation and viability of HT-29 (human colon adenocarcinoma) (Zhang et al., 2017; Kowalik et al., 2020).

We hypothesized that aerial parts of selected Potentilla species, similarly to other species from this genus, would exhibit broad pharmacological potential. Therefore, the primary aim of our study was to assess their cytotoxicity and antiproliferative activities against human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 and human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN. Moreover, we identified the marker metabolites present in extracts through LC-PDA-HRMS analysis to uncover correlations between the qualitative chemical composition of extracts and their possible mechanism of action.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The reference substances, including procyanidin B1, procyanidin B2 and procyanidin C1 were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, United States). Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide and isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside were obtained from Extrasynthese (Genay, France) (+)-Catechin, (-)-epicatechin and gallic acid were the products of Carl Roth (Karlsruhe, Germany). Quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-rutinoside, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside (purity >96%) were isolated from flowers of Ficaria verna L. Hud (Ranunculaceae) (Gudej and Tomczyk, 1999). Quercetin 3-O-galactoside (purity >96%) was isolated from aerial parts of Rubus saxatilis L. (Rosaceae) (Tomczyk and Gudej, 2005) and pedunculagin was isolated from leaves of Rubus caesius L. (Rosaceae) (Grochowski et al., 2020). Quercetin 3-O-arabinofuranoside, ellagic acid and tiliroside (purity >96%) were isolated from aerial parts of Drymocalis rupestris (L.) Soják (Rosaceae) (Tomczyk, 2011). Agrimoniin and ellagic acid 3,3′-di-O-methyl ether 4-O-xyloside (purity >96%) were isolated from aerial parts of P. recta (Tomczyk, 2011; Bazylko et al., 2013). Apigenin and 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid (purity >96%) were isolated from leaves and inflorescences of Arctium tomentosum Mill. (Asteraceae) (Strawa et al., 2020). All other chemicals of analytical grade used in the study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, United States). A POLWATER DL3-100 Labopol (Kraków, Poland) assembly was used to obtain ultra-pure water. Stock solutions of investigated extracts (100 mg/ml), as well as 5-fluorouracil (50 mM), were prepared by dissolving the compounds in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (POCH, Gliwice, Poland). Working solutions of investigated compounds were prepared by dissolving an appropriate stock solution in a culture medium. The final concentration of DMSO in all working solutions used in the studies was the same including control and it was 0.25%.

Plant materials and procedure of plant extracts preparation

Seeds of five species, namely P. alba (ind. sem. 354), P. grandiflora (ind. sem. 758), P. norvegica (ind. sem. 303), P. recta (ind. sem. 1549) and P. rupestris (ind. sem. 763) were kindly provided by the Botanical Garden of Vilnius University (Vilnius, Lithuania), Giardino Botanico Alpino (Cogne, Italy), Hortus Botanicus Universitatis Masarykianae (Brno, Czech Republic) and Hortus Botanicus University of Tartu (Tartu, Estonia). Plants were cultivated in common plots at the Medicinal Plant Garden at the Medical University of Białystok (Białystok, Poland), and aboveground materials were collected in June-August 2016–2019. Aerial parts of P. argentea were collected in June-July 2017–2019 from natural habitat, at Puszcza Knyszyńska (Poland, 53°15′6″N 23°27′58″E). The taxonomic identification of plant material was carefully authenticated by one of the authors (M.T.). Voucher specimens of P. alba (PAL-17039), P. argentea (PAR-02009), P. grandiflora (PGR-06020), P. norvegica (PNO-08024), P. recta (PRE-06019) and P. rupestris (PRU-06021) have been deposited at the Herbarium of the Department of Pharmacognosy, Medical University of Białystok (Poland). Collected dried materials were subsequently finely grounded with an electric grinder and stored in air-tight containers at ambient temperature. Powdered dry plant materials (2.0 g each time) were separately submitted to ultrasound-assisted extraction with 70% acetone (3 × 50 ml) using an ultrasonic bath (Sonic-5, Polsonic, Warszawa, Poland) at a controlled temperature (40 ± 2 °C) for 45 min in a 1:75 (w:v) solvent ratio. The obtained raw extracts after solvent evaporation were diluted with water (50 ml) and subsequently portioned with chloroform (10 × 20 ml). The acetone extracts were obtained using this method for P. alba (PAL7), P. argentea (PAR7), P. grandiflora (PGR7), P. norvegica (PN7), P. recta (PRE7) and P. rupestris (PRU7).

Determination of total phenolic content

The total phenolic content (TPC) was measured by the Folin-Ciocalteu assay with some modifications (Slinkard and Singleton, 1977). Briefly, 25 µl of tested solution (1 mg/ml) was mixed with 100 µl of diluted Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1:9, v/v) and the mixture was allowed to react for 3 min. Thereafter, 75 µl of 1% Na2CO3 solution was added and the prepared mixture was incubated for 2 h at ambient temperature. The absorbance was measured at 760 nm using a microplate reader EPOCH2 BioTech (Winooski, VT, United States). The TPC determination was repeated at least three times for each sample solution. Obtained results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per Gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g extract).

Determination of total tannin content

The total tannin content (TTC) of each extract was measured by the employment of the protein-binding method and Folin-Ciocalteu assay described in the European Pharmacopoeia 10th ed (European Pharmacopoeia, 2019). with modifications. Briefly, each extract dissolved in water (1 mg/ml) was partitioned into two parts. For the first part of extracts total polyphenols were determined for each aliquot (25 µl) by mixing with 100 µl of diluted Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1:9, v/v). After 3 min 75 µl of 1% Na2CO3 was added and the mixture was allowed to stand for 2 h at room temperature. Thereafter the absorbance of each sample (A1) was recorded at 760 nm using a EPOCH2 microplate reader. Subsequently, the second part of aliquots of 0.5 ml each were mixed with 10 mg of hide powder. These preparations were shaken for 1 h without light and then centrifugated. A 25 µl of supernatants were assayed for total polyphenolics as described above and the absorbance of each sample (A2) was recorded at 760 nm. Afterwards, the total tannin content was determined by subtraction of absorbances of total polyphenols (A1) from total non-tannin polyphenols (A2) and the obtained absorbance values were referred to a gallic acid calibration curve to obtain their values as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per Gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g extract). The determination of TTC was repeated at least three times for each sample solution.

Determination of total proanthocyanidin content

The total proanthocyanidin content (TPrC) was analysed with the employment of a 4-dimethylamino-cinnamaldehyde (DMCA) reagent (Feliciano et al., 2012). The analysis was carried out in a microplate reader. A 50 µl of sample solution (1 mg/ml) dissolved in methanol was mixed with 250 µl of 0.1% DMCA in 6 M HCl in methanol. The mixture was incubated at ambient temperature for 15 min, and thereafter, the absorbance was recorded at 635 nm. The TPrC determination was repeated at least five times for each sample solution and was expressed as milligrams of catechin equivalents per Gram of dry extract (mg CE/g extract).

Determination of total flavonoid content

The total flavonoid content (TFC) of each extract was determined using the previously described aluminium chloride (AlCl3) colorimetric method (Augustynowicz et al., 2021a) with slight modifications. In brief, 100 µl of tested solution or 100 µl of blank sample (methanol) was mixed with 100 µl of 2% (w:v) AlCl3 solution. The mixture was kept at ambient temperature for 10 min. Then the absorbance of the mixture was recorded at 415 nm using a EPOCH2 microplate reader. The TFC determination was repeated at least three times for each sample solution. TFC was expressed as milligrams of rutin equivalents per Gram of dry extract (mg RE/g extract).

Determination of total phenolic acid content

The total phenolic acid content (TPAC) determination was carried out using the procedure with the use of Arnov’s reagent (1 g of sodium molybdate and 1 g of sodium nitrate dissolved in 10 ml of distilled water) (Polumackanycz et al., 2019). A 30 µl of the tested solution, 180 µl of water, 30 µl of 0.5 M HCl, 30 µl of Arnov’s reagent and 30 µ of 1 M NaOH were sequentially added to the microplate well. After incubation of mixture at room temperature for 20 min, the absorbance was measured at 490 nm. The TPAC determination was repeated at least three times for each sample solution and the obtained values were expressed as milligrams of caffeic acid equivalents per Gram of dry extract (mg CAE/g extract).

Estimation of qualitative composition with the employment of LC-PDA-HRMS

Evaluation of the secondary metabolite composition of each extract was conducted using an Agilent 1260 Infinity LC chromatography system coupled to a photo-diode array (PDA) detector and 6230 time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometer (Santa Clara, CA, California). The MS conditions were as follows: electrospray ionization (ESI) source in both negative and positive ionization mode, drying and sheath gas flow 11 L/min and temperature of 350°C, nebulizer pressure of 60 psi, capillary voltages of 2,500 and 4500 V for negative and positive ion modes, respectively and fragmentor experiments at 60, 180 and 320 V. The data were collected in the 120–3,000 m/z range. The separation was performed using a Kinetex XB-C18 column (150 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, United States). The mobile phases were ultra pure water (A) and acetonitrile (B) with 0.2% formic acid. The separation was achieved by a gradient of 0–3 min 65% B; 3–35 min 1% B, 35–80 min 12% B, 80–113 min 45% B, extended by 7 min of equilibrating time. The flow rate was 0.2 ml/min, and the column temperature was maintained at 35 ± 0.8°C. The UV-vis spectra were recorded in the range of 190–540 nm with selective wavelength monitoring at 280 and 360 nm. Data were processed with the employment of MassHunter Qualitative 10.0. Analysis software. Compounds were characterized based on UV–Vis and MS spectra and retention time of standards.

Cell cultures

Human colonic epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, United States). Human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 was obtained from the European Collection of Cell Cultures (ECACC, Centre for Applied Microbiology and Research, Salisbury, United Kingdom). Cell cultures were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the collections in which they were purchased.

Examination of the anticancer potential of extracts

Both colon epithelial, as well as colon adenocarcinoma cells, were seeded on 96-well microplates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/mL. The following day, the culture medium was exchanged for fresh medium supplemented with investigated extracts or 25 μM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). After 48 h of cell treatment, the compounds’ antiproliferative effect was determined using Cell Proliferation ELISA BrdU, following the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Penzberg, Germany), while the compounds’ cytotoxicity was examined by the In Vitro Toxicology Assay Kit Lactate Dehydrogenase Based according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). Furthermore, cell viability in response to 48 h of exposure to investigated compounds was determined by MTT assays. A detailed description of the execution of the above-mentioned assays was presented by Langner and co-authors (Langner et al., 2019).

Statistical analysis

The analysed data were presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using One way-ANOVA with the Tukey post-hoc test and column statistics. Statistical significance was accepted at p < 0.05. The IC50 value (concentration leading the 50% inhibition of proliferation compared to the control) was calculated using GraphPad PRISM.

Results

In the first set of experiments, the studied extracts were examined for their TPC, TTC, TPrC, TFC, and TPAC using colorimetric methods. The obtained results are presented in Table 1. PAR7 and PN7, followed by PRU7, were found to contain the highest TPC (339.72, 332.11, and 304.08 mg GAE/g extract, respectively) and TTC (246.92, 252.30, and 209.43 mg GAE/g extract, respectively). PAL7 had the lowest TPC and TTC values (159.87 and 84.89 mg GAE/g). However, PAL7 was found to contain the highest TPrC (21.28 mg CE/g extract), while the other extracts had low proanthocyanidin content. The TFC levels for all tested samples were found to be similar, with the highest values for PAL7 and PAR7 (71.85 and 56.79 mg RE/g extract, respectively). Moreover, the highest TPAC values were revealed for PAL7 and PN7 (124.18 and 78.95 mg CAE/g extract, respectively).

TABLE 1

| Samples | TPC (mg GAE/g extract) | TTC (mg GAE/g extract) | TPrC (mg CE/g extract) | TFC (mg RE/g extract) | TPAC (mg CAE/g extract) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAL7 | 159.87 ± 1.79 | 84.89 ± 1.40 | 21.28 ± 0.04 | 71.85 ± 1.40 | 124.18 ± 1.18 |

| PAR7 | 339.72 ± 5.29 | 246.92 ± 4.64 | 6.95 ± 0.07 | 56.79 ± 0.98 | 78.95 ± 0.90 |

| PGR7 | 228.36 ± 3.40 | 156.53 ± 3.71 | 3.80 ± 0.06 | 47.61 ± 0.35 | 58.61 ± 0.34 |

| PN7 | 332.11 ± 1.40 | 252.30 ± 1.70 | 1.14 ± 0.02 | 38.06 ± 0.79 | 92.78 ± 1.03 |

| PRE7 | 257.68 ± 2.95 | 170.45 ± 2.86 | 2.70 ± 0.08 | 43.37 ± 0.84 | 75.20 ± 1.23 |

| PRU7 | 304.08 ± 2.51 | 209.43 ± 2.57 | 1.11 ± 0.02 | 47.74 ± 0.73 | 55.45 ± 0.59 |

Total phenolic (TPC), tannin (TTC), proanthocyanidin (TPrC), flavonoid (TFC) and phenolic acid contents (TPAC) of selected acetone extracts of Potentilla species.

*GAE, gallic acid equivalent; CE, catechin equivalent; RE, rutin equivalent; CAE, caffeic acid equivalent.

To unveil the secondary metabolite composition, acetone extracts of selected Potentilla species were analysed via LC-PDA-HRMS. The analysis demonstrated the presence of 83 compounds, predominately polyphenolic compounds, ascribed to hydrolysable and condensed tannins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. Hydrolysable tannins were present in all extracts with the exception of PAL7, primarily represented by ellagitannins, such as pedunculagin α and β (3,8), agrimoniin (69), laevigatin isomers (39, 40, 47), galloyl-HHDP-glucose isomers (6, 9, 18), galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose isomers (38, 42, 63), ellagic acid (51), ellagic acid 3,3′-di-O-methyl ether 4-O-xyloside (75), ellagic acid 3′-O-methyl ether 4-O-xyloside (54), and ellagic acid 3′-O-methyl ether 4-O-arabinoside (70). PRU7 showed the presence of gallotannins, such as tri-, tetra-, and pentagalloylglucose isomers (32, 55, 72). Moreover, the degradation products of hydrolysable tannins, namely brevifolincarboxylic acid 19) and brevifolin (33), were found. On the other hand, PAL7 and PAR7 were rich in the condensed tannins, such as (+)-catechin 13) and (-)-epicatechin (27), and oligomeric procyanidins, such as procyanidin B1 (12), B2 (20), and C1 (37). A number of flavonoids were detected and characterized, including apigenin 78) and its O-hexoside (68), isorhamnetin (36, 64, 71, 73, 74), kaempferol (31, 59, 61, 62, 66, 67, 77, 79–81), and quercetin (23, 24, 26, 41, 43–48, 52, 56–58, 60, 65, 76) derivatives. In addition, phenolic acids were also present in extracts, such as gallic acid (1), caffeic acid derivatives (5, 14, 17, 28, 30), p-coumaroylquinic acid isomers (10, 11, 25, 29), and N1, N5, N10-tricoumaroyl spermidine (83). The detailed chromatographic data are shown in Table 2 and in Supplementary Figures S1–S6.

TABLE 2

| No. | Compounds | Rt [min] | UV spectra [λ max nm] | Observeda | Δ [ppm] | Formula | Fragmentation | Presence in extracts | Ref | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | PAL7 | PAR7 | PGR7 | PN7 | PRE7 | PRU7 | ||||||||

| 1 | Gallic acid | 5.70 | 270 | 169.01370 | -3.44 | C7H6O5 | 169, 125 | + | + | + | + | + | (s) | ||

| 2 | 2-Pyrone-4,6-dicarboxylic acid | 6.65 | 316 | 182.99276 | -3.46 | C7H4O6 | 366, 182, 139 | + | + | + | + | + | Wilkes and Glasl, (2001) | ||

| 3 | Pedunculagin α or β | 15.35 | 260sh | 783.06883 | 0.38 | C34H24O22 | 783, 481, 301 | + | + | + | + | + | Grochowski et al. (2020), (s) | ||

| 4 | Polyphenol derivative | 15.70 | 280 | 337.11359 | -1.03 | C13H22O10 | 193, 125 | + | |||||||

| 5 | 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 20.07 | 295sh, 325 | 353.08747 | -0.96 | C16H18O9 | 353, 191, 179 | 355, 163 | + | + | + | (s) | |||

| 6 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose | 22.26 | 250sh | 633.07245 | -0.24 | C27H22O18 | 633, 301 | + | |||||||

| 7 | Unknown | 22.45 | 276 | 345.11788 | -2.82 | C15H22O9 | 345, 299, 161 | + | |||||||

| 8 | Pedunculagin α or β | 23.30 | 260sh | 783.06929 | 0.85 | C34H24O22 | 783, 481, 301 | + | + | + | + | + | Grochowski et al. (2020), (s) | ||

| 9 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose | 24.07 | 280sh | 633.07359 | 0.36 | C27H22O18 | 633, 481, 301 | + | + | + | |||||

| 10 | p-Coumaroylquinic acid isomer | 24.41 | 308 | 337.09247 | -0.92 | C16H18O8 | 337, 191, 163 | 339, 147 | + | ||||||

| 11 | p-Coumaroylquinic acid isomer | 25.27 | 312 | 337.09218 | -1.59 | C16H18O8 | 337, 191, 163 | 339, 147 | + | ||||||

| 12 | Procyanidin B1 | 26.20 | 280 | 577.13507 | 0.81 | C30H26O12 | 577, 289 | 579, 291, 139 | + | (s) | |||||

| 13 | Catechin | 27.10 | 280 | 289.07136 | -1.42 | C15H14O6 | 289, 245 | 291, 139 | + | + | (s) | ||||

| 14 | 3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 28.21 | 295sh, 325 | 353.08729 | -1.45 | C16H18O9 | 353, 191 | 355, 163 | + | + | + | + | Strawa et al. (2020), (s) | ||

| 15 | Digalloyl-HHDP-glucose | 28.56 | 275 | 785.08369 | -0.63 | C34H26O22 | 785, 301 | + | |||||||

| 16 | Feruloylquinic acid isomer | 29.86 | 295sh, 325 | 367.10365 | 0.61 | C17H20O9 | 367, 193 | 369, 177 | + | + | |||||

| 17 | Caffeoylquinic acid isomer | 30.91 | 295sh, 325 | 353.08779 | -0.08 | C16H18O9 | 353, 191, 179 | 355, 163 | + | ||||||

| 18 | Galloyl-HHDP-glucose | 31.61 | 275 | 633.07366 | -0.27 | C27H22O18 | 633, 463, 301 | + | + | + | + | + | |||

| 19 | Brevifolincarboxylic acid | 32.11 | 278, 360 | 291.01385 | -2.02 | C13H8O8 | 291, 247 | 293 | + | + | + | + | + | Luo et al. (2020) | |

| 20 | Procyanidin B2 | 33.73 | 278 | 577.13556 | 0.82 | C30H26O12 | 577, 289 | 579, 291, 139 | + | (s) | |||||

| 21 | Ellagic acid derivative | 33.89 | 285sh | 898.13313 | -1.54 | C29H39O32 | 898, 633, 301 | + | |||||||

| 22 | Ellagic acid derivative | 34.13 | 325sh | 632.06474 | -1.85 | C27H21O18 | 632, 463, 301 | + | |||||||

| 23 | Quercetin O-hexoso O-uronic acid derivative | 34.20 | 255, 350 | 639.12125 | 1.20 | C27H28O18 | 639, 300 | 641, 479, 303 | + | ||||||

| 24 | Quercetin O-di-uronic acid derivative | 34.40 | 255, 355 | 653.09958 | -0.45 | C27H26O19 | 653, 477, 301 | 655, 479, 303 | + | + | + | ||||

| 25 | p-Coumaroylquinic acid isomer | 35.13 | 312 | 337.09285 | 0.02 | C16H18O8 | 337, 191 | 339, 147 | + | + | |||||

| 26 | Quercetin O-hexoso O-uronic acid derivative | 35.35 | 270, 350 | 639.12105 | -0.61 | C27H28O18 | 639, 463, 301 | 641, 465, 303 | + | + | |||||

| 27 | Epicatechin | 35.74 | 280 | 289.07133 | -1.43 | C15H14O6 | 289, 245 | 291, 139 | + | (s) | |||||

| 28 | 2-Caffeoylisocitric acid | 36.30 | 300sh, 328 | 353.05046 | -2.69 | C15H14O10 | 353, 191, 155 | + | + | + | Manyelo et al. (2020) | ||||

| 29 | p-coumaroylquinic acid isomer | 36.52 | 312 | 337.09314 | -0.26 | C16H18O8 | 337, 163 | 339, 147 | + | ||||||

| 30 | Caffeoylmalic acid | 38.51 | 295sh, 326 | 295.04541 | -1.72 | C13H12O8 | 591, 295, 179, 133 | 135 | + | + | + | + | Szajwaj et al. (2011) | ||

| 31 | Kaempferol O-di-uronic acid derivative | 38.97 | 265, 350 | 637.10470 | -0.62 | C27H26O18 | 637, 461, 285 | 639, 463, 287 | + | + | |||||

| 32 | Trigalloylglucose isomer | 39.10 | 276 | 635.08918 | 0.20 | C27H24O18 | 635, 465, 313, 169 | + | Luo et al. (2020) | ||||||

| 33 | Brevifolin | 39.4 | 275, 350 | 247.02433 | -1.83 | C12H8O6 | 247, 191 | 249 | + | + | + | + | + | Luo et al. (2020) | |

| 34 | Procyanidin A-type trimer | 40.51 | 280 | 863.18353 | 1.19 | C45H36O18 | 863, 573, 289 | 865, 287 | + | ||||||

| 35 | Ellagic acid O-hexoside derivative | 41.20 | 252, 365 | 463.05162 | -0.79 | C20H16O13 | 463, 301 | + | + | ||||||

| 36 | Isorhamnetin O-di-uronic acid derivative | 41.78 | 254, 352 | 667.11555 | 1.29 | C28H28O19 | 667, 315, 300 | 669, 493, 317 | + | + | + | ||||

| 37 | Procyanidin C1 | 41.88 | 280 | 865.19924 | 0.68 | C45H38O18 | 865, 577, 289 | 867, 579, 291 | + | (s) | |||||

| 38 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose | 43.98 | 255 | 935.07947 | 0.30 | C41H28O26 | 935, 633, 467, 301 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 39 | Laevigatin isomer | 44.46 | 255 | 1,567.14331 | -1.15 | C68H48O44 | 1,567, 783, 301 | + | + | + | + | + | Fecka et al. (2015) | ||

| 40 | Laevigatin isomer | 45.94 | 255 | 1,567.14331 | -1.15 | C68H48O44 | 1,567, 783, 301 | + | + | Fecka et al. (2015) | |||||

| 41 | Quercetin O-hexoso O-deoxyhexoside isomer | 46.98 | 255, 352 | 609.14615 | -0.73 | C27H30O16 | 609, 446, 299 | 611, 499, 303 | + | ||||||

| 42 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose | 47.33 | 276sh | 935.07900 | -0.79 | C41H28O26 | 935, 783, 633, 467, 301 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 43 | Quercetin O-hexoso-deoxyhexo-pentoside isomer | 47.90 | 255, 355 | 741.18912 | -0.64 | C32H38O20 | 741, 447, 300 | 743, 611, 465, 303 | + | ||||||

| 44 | Quercetin O-deoxyhexoso-O-hexoso-deoxyhexoside isomer | 48.66 | 256, 356 | 755.20326 | -0.67 | C33H40O20 | 755, 609, 446, 299 | 757, 611, 449, 303 | + | ||||||

| 45 | Quercetin O-hexoso-pentoside isomer | 49.55 | 255, 355 | 595.13019 | -0.10 | C26H28O16 | 595, 300, 271 | 597, 465, 303 | + | + | |||||

| 46 | Quercetin O-hexoso-pentoside isomer | 50.48 | 255, 355 | 595.13046 | -0.72 | C26H28O16 | 595, 300, 271 | 597, 465, 303 | + | + | |||||

| 47 | Laevigatin isomer | 51.09 | 255 | 1,567.14239 | -1.74 | C68H48O44 | 1,567, 783, 301 | + | + | + | + | Fecka et al. (2015) | |||

| 48 | Quercetin O-pentoso-O-uronic acid derivative | 52.30 | 255, 354 | 609.11075 | -1.11 | C26H26O17 | 609, 301 | 611, 479, 303 | + | + | |||||

| 49 | Ellagic acid 3′-O-methyl ether O-uronic acid derivative | 54.10 | 254, 360 | 491.04709 | 0.29 | C21H16O14 | 491, 315, 301 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 50 | Ellagic acid O-pentoside | 55.7 | 252, 360 | 433.04108 | 0.30 | C19H14O12 | 433, 301 | + | + | ||||||

| 51 | Ellagic acid | 56.71 | 254, 370 | 300.99841 | -1.60 | C14H6O8 | 301, 271 | 303 | + | + | + | + | + | Tomczyk (2011), (s) | |

| 52 | Quercetin 3-O-glucoside | 59.30 | 255, 355 | 463.08816 | 0.13 | C21H20O12 | 463, 300, 271 | 465, 303 | + | + | + | + | (s) | ||

| 53 | Unknown | 59.80 | 290 | 435.09238 | -2.77 | C20H20O11 | 871, 435, 285, 151 | + | |||||||

| 54 | Ellagic acid 3′- O-methyl ether 4-O-pentoside | 60.40 | 252, 362 | 447.05600 | -1.85 | C20H16O12 | 447, 301 | + | |||||||

| 55 | Tetragalloylglucose isomer | 62 | 278 | 787.09898 | -1.57 | C34H28O22 | 787, 617, 465, 169 | + | Luo et al. (2020) | ||||||

| 56 | Quercetin 3-O-rutoside | 63.38 | 256, 354 | 609.14571 | -0.32 | C27H30O16 | 609, 300, 271 | 611, 465, 303 | + | + | + | Gudej and Tomczyk, (1999), (s) | |||

| 57 | Quercetin 3-O-galactoside | 64.03 | 255, 355 | 463.08816 | -0.70 | C21H20O12 | 463, 300, 271 | 465, 303 | + | + | + | + | + | Tomczyk and Gudej, (2005), (s) | |

| 58 | Quercetin O-glucuronide | 64.83 | 255, 355 | 477.06649 | -1.73 | C21H20O13 | 477, 300, 271 | 479, 303 | + | + | + | (s) | |||

| 59 | Kaempferol O-hexoso-pentoside | 64.85 | 265, 350 | 579.13594 | 1.19 | C26H28O15 | 579, 284 | 581, 449, 287 | + | ||||||

| 60 | Quercetin O-uronic acid derivative | 66.18 | 256, 354 | 477.06713 | -0.49 | C21H18O13 | 477, 301 | 479, 303 | + | ||||||

| 61 | Kaempferol O-hexoso-pentoside | 66.85 | 265, 350 | 579.13520 | -0.41 | C26H28O15 | 577, 284 | 581, 449, 287 | + | ||||||

| 62 | Kaempferol O-hexoside | 67.40 | 252, 350 | 447.09365 | -0.44 | C21H20O11 | 447, 284 | 449, 287 | + | + | |||||

| 63 | Galloyl-bis-HHDP-glucose | 69 | 260sh | 935.07978 | -0.18 | C41H28O26 | 935, 467, 301 | + | + | + | + | ||||

| 64 | Isorhamnetin O-hexoso-pentoside | 73.99 | 255, 352 | 609.14611 | 0.20 | C27H30O16 | 609, 314, 271 | 611, 479, 317 | + | + | |||||

| 65 | Quercetin 3-O-arabinofuranoside | 85.20 | 254sh, 350 | 433.07665 | -2.12 | C20H18O11 | 433, 300 | 435, 303 | + | Tomczyk (2011), (s) | |||||

| 66 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | 88.33 | 265, 350 | 447.09298 | -1.70 | C21H20O11 | 447, 284 | 449, 287 | + | + | + | + | + | + | Gudej and Tomczyk, (1999), (s) |

| 67 | Kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide | 89.30 | 265, 346 | 461.07171 | -0.92 | C21H18O12 | 461, 285 | 463, 287 | + | + | + | (s) | |||

| 68 | Apigenin O-hexoside | 90.04 | 266, 340 | 431.09754 | -0.71 | C21H20O10 | 431, 268 | 433, 271 | + | ||||||

| 69 | Agrimoniin | 90.30 | 250sh | 1870.15689 | -0.95 | C82H54O52 | 1870, 1,085, 934, 783, 301 | + | + | + | + | + | Bazylko et al. (2013), (s) | ||

| 70 | Ellagic acid 3′-O-methyl ether 4-O-pentoside | 90.42 | 280sh, 365 | 447.05604 | -0.72 | C20H16O12 | 447, 315, 301 | + | + | + | Luo et al. (2020) | ||||

| 71 | Isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside | 91.43 | 265, 355 | 477.10387 | 0.49 | C22H22O12 | 477, 314 | 479, 317 | + | (s) | |||||

| 72 | Pentagalloyloglucose isomer | 91.68 | 280 | 939.11105 | 0.49 | C41H32O26 | 939, 769, 469, 169 | + | |||||||

| 73 | Isorhamnetin O-deoxyhexoso-hexoso-O-pentoside isomer | 91.92 | 254sh, 355 | 753.18766 | -0.45 | C33H38O20 | 753, 314, 299 | 755, 623, 317 | + | ||||||

| 74 | Isorhamnetin O-uronic acid derivative | 92.81 | 255, 354 | 491.08356 | 0.77 | C22H20O13 | 491, 315, 300 | 493, 317 | + | + | |||||

| 75 | Ellagic acid 3,3′-di-O-methyl ether 4-O-xyloside | 94.14 | 245, 370 | 461.07148 | -1.26 | C21H18O12 | 461, 328, 297 | 463, 331 | + | + | Tomczyk (2011), (s) | ||||

| 76 | Quercetin O-uronic acid derivative | 94.80 | 270sh, 370 | 477.06758 | 0.10 | C21H18O13 | 477, 301 | 479, 303 | + | ||||||

| 77 | Kaempferol derivative | 94.90 | 266sh, 348 | 533.09391 | 0.27 | C24H22O14 | 533, 489, 284 | 535, 287 | + | ||||||

| 78 | Apigenin | 98.04 | 268, 338 | 269.04538 | -2.04 | C15H10O5 | 269, 227 | 271 | + | Strawa et al. (2020), (s) | |||||

| 79 | trans-Tiliroside | 101.48 | 268, 315 | 593.12979 | -0.55 | C30H26O13 | 593, 284 | 595, 287 | + | + | + | + | + | + | Tomczyk (2011), (s) |

| 80 | Kaempferol derivative | 101.87 | 268, 330 | 623.14131 | 1.02 | C31H28O14 | 623, 284 | 625, 595, 287 | + | + | + | ||||

| 81 | cis-Tiliroside | 102.37 | 268, 315 | 593.12928 | 0.44 | C30H26O13 | 593, 284 | 595, 287 | + | + | + | + | + | Luo et al. (2020) | |

| 82 | Unknown | 102.54 | 280 | 445.18621 | -1.13 | C24H30O8 | 445, 385 | + | + | ||||||

| 83 | N1, N5, N10-tricoumaroyl spermidine | 104.47 | 295, 310sh | 582.26072 | -0.06 | C34H37N3O6 | 582, 462, 342, 285 | 584, 438, 292, 147 | + | + | + | + | + | + | Elejalde-Palmett et al. (2015) |

MS and UV-Vis data of compounds detected in acetone extracts prepared from aerial parts of selected Potentilla species.

Exact mass of [M-H]- ion; sh–peak shoulder; bold–most aboundantion; (s)—reference substance; HHDP, hexahydroxydiphenoyl group.

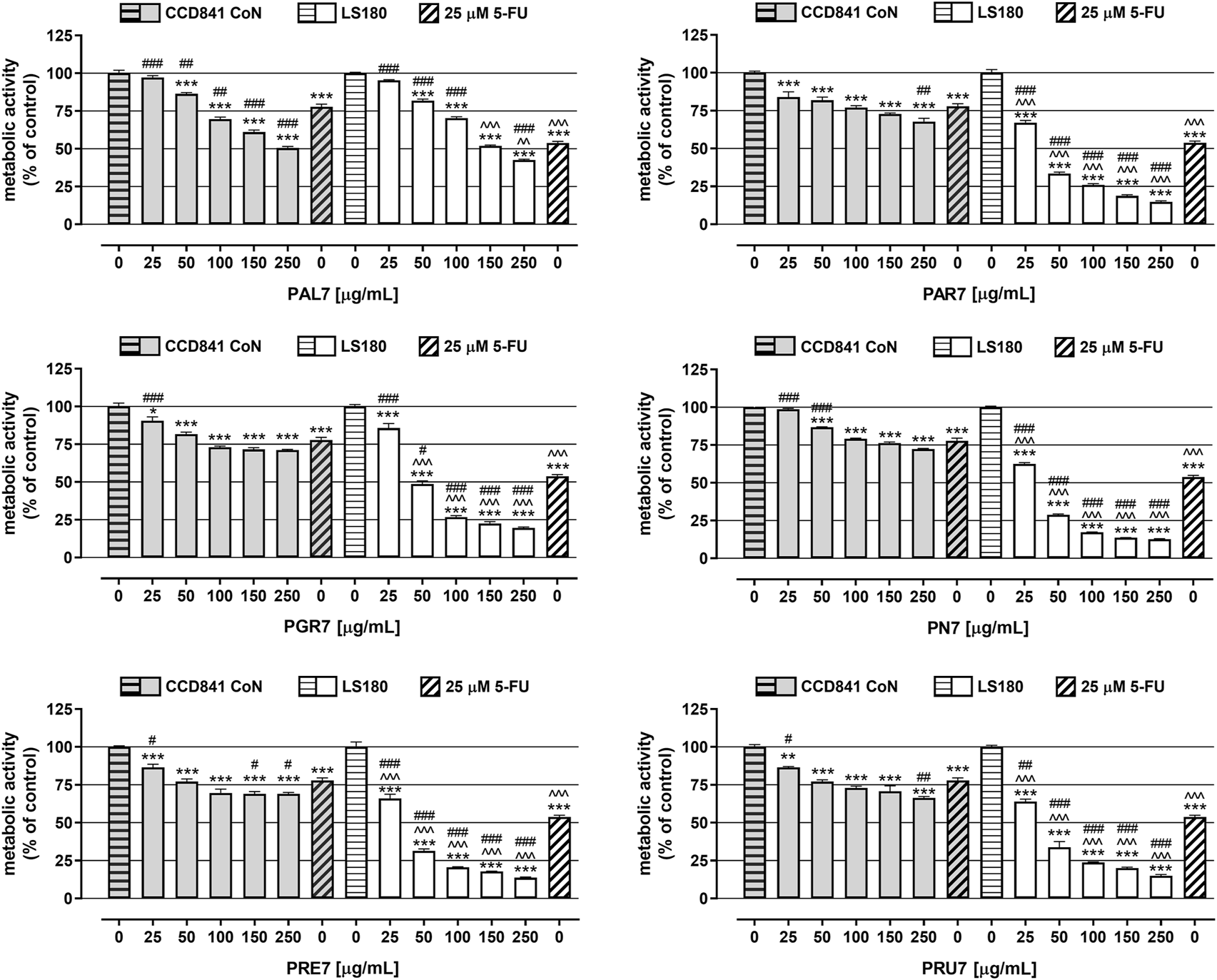

In the next set of experiments, the viability of both human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN and human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 was examined in response to the investigated Potentilla extracts. Cells were exposed to either culture medium (control) or extracts (25–250 μg/ml) for 48 h and, afterward, an MTT test was performed. As presented in Figure 1 and Table 3, all investigated acetone extracts inhibited, in a dose-dependent manner, the metabolic activity of both the normal and cancer colon cell lines. The most significant anticancer effect was achieved by extract PN7, which at the highest tested concentration decreased LS180 cell proliferation by 87.3% (IC50 PN7 LS180 = 32 μg/ml), while the weakest effect was noted for PAL7, which at a concentration of 250 μg/ml inhibited cancer cells division by 57.5% (IC50 PAL7 LS180 = 182 μg/ml). In the case of colon epithelial cells, the strongest reduction (49.5%) of their metabolic activity was observed after exposure to 250 μg/ml PAL7 (IC50 PAL7 CCD841 CoN = 233 μg/ml), while the weakest effect, as reflected by the IC50 value, was for PAR7 (IC50 PAR7 CCD841 CoN = 1,134 μg/ml). Although all investigated extracts affected both normal and cancer colon cells, LS180 cells were more sensitive to the tested compounds. Comparing the metabolic activity in both analysed cell lines in response to extracts at the corresponding concentrations, greater sensitivity of cancer cells was observed in the entire range of analysed concentrations in the case of PAR7, PRE7, PRU7, and PN7, while PGR7 showed statistically significant differences in concentrations from 50 μg/ml to 250 μg/ml. Even PAL7 at the highest tested concentrations (150 and 250 μg/ml) strongly inhibited the viability of cancer cells than colon epithelial cells. As a positive control of the experiment, 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) at a concentration of 25 µM was used (Figure 1). The metabolic activity of CCD841 CoN and LS180 cells decreased in response to 5-FU by 22.2% and 46.2%, respectively. Comparing data obtained from the extracts with cell responses to 5-FU revealed that four of six investigated fractions at higher concentrations inhibited the metabolic activity of CCD841 CoN cells more strongly than 25 µM 5-FU: PAL7 (100, 150, 250 μg/ml); PRE7 (150, 250 μg/ml); and both PAR7 and PRU7 (250 μg/ml). In the case of colon cancer cells, PGR7, PAR7, PRE7, PRU7, and PN7 at concentrations from 50 to 250 μg/ml and PAL7 at a concentration of 250 μg/ml showed a stronger anti-metabolic effect than the analysed cytostatic.

FIGURE 1

Influence of acetone extracts isolated from the aerial parts of Potentilla L. on the viability of human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN and human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180. The cells were exposed for 48 h to the culture medium alone (control), or extract at concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 250 μg/ml, or 25 μM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; positive control). The metabolic activity of investigated cell lines in response to tested compounds was examined photometrically by means of MTT assay. Results are presented as mean ± SEM of at least six measurements. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. control, #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 vs. positive control, ^^p < 0.01; ^^^p < 0.001 colon cancer cells treated with extract/5-FU vs. colon epithelial cells exposed to the extract/5-FU at the corresponding concentration; one-way ANOVA test; post-test: Tukey.

TABLE 3

| Sample | MTT assay | BrdU assay | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS180 | CCD841 CoN | LS180 | CCD841 CoN | |||||||||

| IC50 (µg/ml) | Trust range (µg/ml) | R 2 | IC50 (µg/ml) | Trust range (µg/ml) | R 2 | IC50 (µg/ml) | Trust range (µg/ml) | R 2 | IC50 (µg/ml) | Trust range (µg/ml) | R 2 | |

| PAL7 | 182 | 169–196 | 0.983 | 233 | 209–261 | 0.971 | 12,008 | 2096–68,805 | 0.752 | 4,164 | 1759–9,859 | 0.867 |

| PAR7 | 38 | 32–44 | 0.974 | 1,134 | 575–2,235 | 0.902 | 174 | 165–183 | 0.982 | 217 | 203–231 | 0.977 |

| PGR7 | 58 | 50–67 | 0.957 | 982 | 498–1938 | 0.890 | 372 | 338–409 | 0.968 | 570 | 488–666 | 0.965 |

| PN7 | 32 | 28–37 | 0.981 | 757 | 459–1,248 | 0.903 | 169 | 159–179 | 0.974 | 217 | 202–233 | 0.958 |

| PRE7 | 35 | 30–42 | 0.969 | 918 | 449–1879 | 0.882 | 237 | 223–251 | 0.966 | 268 | 248–289 | 0.943 |

| PRU7 | 36 | 30–42 | 0.974 | 846 | 481–1,489 | 0.916 | 360 | 311–416 | 0.95 | 538 | 425–681 | 0.926 |

| 5-FU | 31 | 28–33 | 0.977 | 113 | 81–157 | 0.884 | 15 | 13–16 | 0.956 | 94 | 80–111 | 0.933 |

IC50 values (concentration causing viability/proliferation inhibition by 50% compared to control) of acetone extracts isolated from the aerial parts of Potentilla L and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). IC50 values were calculated for human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN and human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180 based on results of MTT and BrdU assays performed after 48 h of cells treatment with investigated compounds.

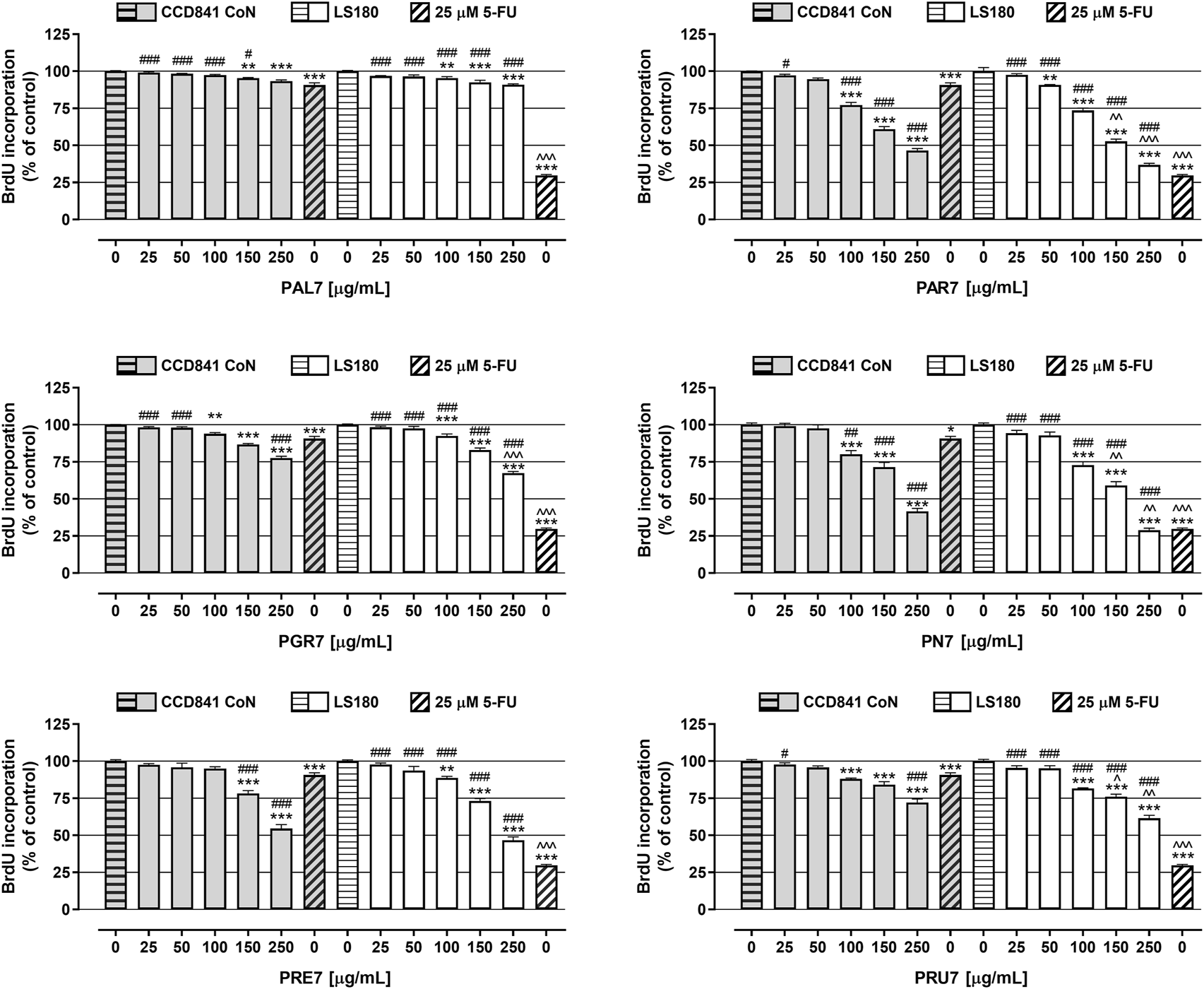

In the next step, the antiproliferative activity of Potentilla extracts was assessed in the abovementioned cell lines using BrdU assay (Figure 2; Table 3). A significant decrease of DNA synthesis in colon cancer cells was observed in response to all investigated extracts at concentrations ranging from 100 μg/ml to 250 μg/ml, and simultaneously in the case of PAR7 a statistically significant antiproliferative effect was also noted at the concentration 50 μg/ml. Furthermore, PAR7 and PN7 showed the strongest inhibition of cancer cell proliferation, as reflected by the lowest IC50 values (IC50 PAR7 LS180 = 174 μg/ml and IC50 PN7 LS180 = 169 μg/ml) and the greatest decrease of DNA synthesis in LS180 cells in response to the extracts at a concentration of 250 μg/ml (cell proliferation was reduced by 63.1% (PAR7) and 71.1% (PN7)). Colon cancer cell division was least inhibited by PAL7 (IC50 PAL7 LS180 = 12 mg/ml), which at the highest tested concentration decreased DNA synthesis by only 9.1%. The investigated extracts also affected the proliferation of colon epithelial cells and statistically significant inhibition of DNA synthesis was noted in response to all compounds at concentrations of 150 and 250 μg/ml, while in the case of PN7, PAR7, PRU7, and PGR7 the antiproliferative effect was observed also at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. Similar to the colon cancer cells, epithelial cells were the most sensitive to PN7 and PAR7, which at a concentration of 250 μg/ml reduced their proliferation by 58.4% and 53.4%, respectively (IC50 PN7 CCD841 CoN = 217 μg/ml and IC50 PAR7 CCD841 CoN = 217 μg/ml). The weakest antiproliferative effect in CCD841 CoN cells was observed after exposure to PAL7, which at the highest tested concentration inhibited cell division by only 6.7%. Studies have revealed the antiproliferative abilities of Potentilla extracts in both normal and cancer colon cells, nevertheless PGR7 at the highest tested concentration, as well as PAR7, PRU7, and PN7 at concentrations 150 and 250 μg/ml, inhibited DNA synthesis significantly more strongly in LS180 cells than CCD841 CoN cells. As presented in Figure 2, 25 µM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) decreased DNA synthesis in the investigated cell lines by 90.7% (CCD841 CoN) and 29.7% (LS180). The antiproliferative effect of 5-FU observed in colon cancer cells was significantly stronger than changes induced by examined extracts. On the contrary, data collected from colon epithelial cells revealed that five out of six investigated extracts in higher concentrations inhibited DNA synthesis more strongly than 25 µM 5-FU: both PAR7 and PN7 (100, 150, 250 μg/ml); PRE7 (150, 250 μg/ml); and both PGR7 and PRU7 (250 μg/ml). The obtained data indicated a higher selectivity of the analysed cytostatic compared with examined extracts in the case of influence on DNA synthesis.

FIGURE 2

Antiproliferative effect of acetone extracts isolated from the aerial parts of Potentilla L. on human colon epithelial cell line CCD841 CoN and human colon adenocarcinoma cell line LS180. The cells were exposed for 48 h to the culture medium alone (control), or the extracts at concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 250 μg/ml, or 25 μM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; positive control). The antiproliferative impact of the investigated compounds was measured by immunoassay based on BrdU incorporation into newly synthesized DNA. Results are presented as mean ± SEM of at least six measurements. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 vs. control, #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 vs. positive control, ^p < 0.05; ^^p < 0.01; ^^^p < 0.001 colon cancer cells treated with extract/5-FU vs. colon epithelial cells exposed to the extract/5-FU at the corresponding concentration; one-way ANOVA test; post-test: Tukey.

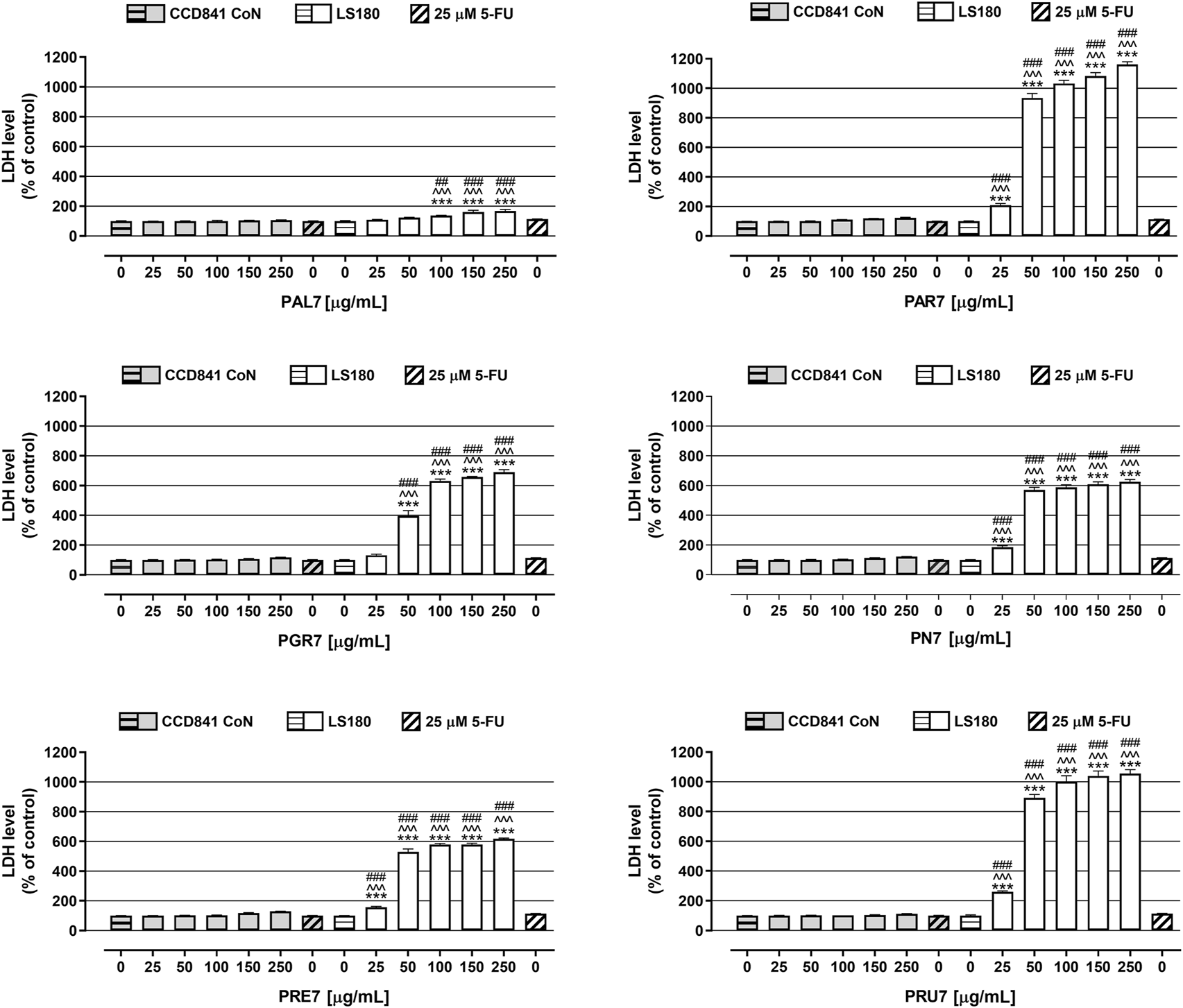

In the last step of the in vitro studies, extracts cytotoxicity was examined in CCD841 CoN cells and LS180 cells using LDH-based assay. As presented in Figure 3, the tested extracts were not cytotoxic against human colon epithelial cells, while they significantly damaged the cell membranes of colon cancer cells, and the observed effect was dose-dependent. The strongest release of LDH was noted in LS180 cells in response to PAR7, which in concentrations ranging from 25 to 250 μg/ml increased the LDH level by 110% and 1,062%, respectively. Very similar results were obtained after LS180 cell exposure to PRU7, which in the mentioned range of concentrations increased LDH release by 161% (25 μg/ml) and 956% (250 μg/ml). The weakest cytotoxic effect was noted in colon cancer cells treated with PAL7, which at the highest tested concentration caused an increase in the LDH level of 68%. Used as a positive control, 5-FU at a concentration of 25 µM was not cytotoxic against colon epithelial or colon cancer cells (Figure 3). The LDH levels of the cells were 100.7% (CCD841 CoN) and 113.4% (LS180). All investigated extracts damaged colon cancer cell membranes more effectively than 5-FU, and this difference was especially evident in the case of PRU7, PAR7, PN7, and PRE7, which even at the lowest tested concentration (25 μg/ml) increased the LDH level to 261, 210, 185, and 156%, respectively.

FIGURE 3

Influence of acetone extracts isolated from the aerial parts of Potentilla L. on cell membrane integrity of human colon epithelial CCD841 CoN cells and human colon adenocarcinoma LS180 cells. The cells were exposed for 48 h to the culture medium alone (control), or extracts at concentrations of 25, 50, 100, 150, and 250 μg/ml, or 25 μM 5-fluorouracil (5-FU; positive control). Compound cytotoxicity (level of LDH released into the cell culture medium from damaged cell membranes) was measured using LDH assay. Results are presented as mean ± SEM of at least six measurements. ***p < 0.001 vs. control, #p < 0.05; ##p < 0.01; ###p < 0.001 vs. positive control, ^^^p < 0.001 colon cancer cells treated with extract/5-FU vs. colon epithelial cells exposed to the extract/5-FU at the corresponding concentration; one-way ANOVA test; post-test: Tukey.

Discussion

Many studies have shown that Potentilla species are a source of a wide spectrum of secondary metabolites, mainly polyphenols, such as hydrolysable and condensed tannins, flavonoids and their glycosides, and phenolic acids, which show a variety of biological activities (Augustynowicz et al., 2021b). Potentilla species have a long history of use to treat intestinal problems, such as diarrhoea, inflammatory bowel disease (Tomczyk and Latte, 2009). Selected species for the present study are common in the Europe and were rarely selected as a subject of anticancer evaluation. Basing on the literature search we hypothesized that similarly to other species from this genus would exhibit anticancer potential. The quantitative identification of polyphenolic classes present in extracts using colorimetric methods offers information on their general contents. In our study, high TPC, TFC, and TTC values were observed in all tested samples. The TPC and TFC results were significantly higher compared to previous studies on aerial parts of P. argentea, P. grandiflora, P. recta, and P. norvegica (Tomczyk et al., 2010; Sut et al., 2019; Augustynowicz et al., 2021a). The differences in results can be partially explained by the type of solvent used in the extraction process. Aqueous acetone during the extraction process inhibits the interaction between tannins and proteins, and decreases the cleaving of depside bonds in hydrolysable tannins in comparison to aqueous alcohols. These mechanisms may lead to higher contents of high-molecular tannins in acetone extracts (Hagerman, 1988; Mueller-Harvey, 2001). Moreover, on several occasions, acetone has been reported as a good solvent for the extraction of flavonoids with higher contents, in comparison to water and alcoholic solvents (Dirar et al., 2019; Patel and Ghane, 2021). Furthermore, LC-PDA-HRMS analysis revealed a number of polyphenols, such as ellagitannins and products of their degradation, flavonoids, and phenolic acids, that were present in all extracts. Ellagitannins are plant secondary metabolites that tend to form relatively high molecular weight dimers and oligomers, ranging from 300 to 20,000 Da. Plants from the Rosaceae family accumulate a series of oligomeric, macrocyclic oligomeric, and C-glycosidic ellagitannins that can be used as chemophenetic markers (Grochowski et al., 2017; Gesek et al., 2021). On several occasions the presence of dimeric ellagitannin - agrimoniin in aerial parts of Potentilla species, in particular P. anserina and P. kleiniana, P. recta, have been reported (Okuda et al., 1982; Fecka, 2009; Bazylko et al., 2013). The chromatographic analysis reported herein indicates that agrimoniin is the most abundant ellagitannin in all extracts except PAL7. Moreover, several other phenolic compounds, such as pedunculagin, laevigatins, brevifolincarboxylic acid, and ellagic acid, an artifact, are released as a product of hydrolysis of ellagitannins. These compounds are widely present in the aerial parts of different species belonging to the genus Potentilla, including P. indica, P. freyniana, Duchesnea chrysantha, and P. anserina, and therefore could be considered significant in the chemophenetics of this genus (Okuda et al., 1992; Lee and Yang, 1994; Fecka, 2009; Luo et al., 2020). Furthermore, flavonol derivatives, such as quercetin 3-O-rutoside, quercetin 3-O-galactoside, quercetin 3-O-glucuronide, quercetin 3-O-arabinoside, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, kaempferol 3-O-glucuronide, and tiliroside, were found in at least one of the 17 investigated Potentilla species (Tomczyk and Latte, 2009; Augustynowicz et al., 2021b). More interestingly, N-acylated biogenic amine derivative, N1, N5, N10-tricoumaroyl spermidine, was reported for the first time in the genus Potentilla. This compound accumulates exclusively in the pollen coat and has been detected in several other genera in the Rosaceae family (Elejalde-Palmett et al., 2015).

The anticancer potential of acetone extracts isolated from selected Potentilla species was examined in both colon cancer LS180 cells as well as normal colon epithelial CCD841 CoN cells by investigation compounds influence on cell viability (MTT assay), proliferation (BrdU assay), and cytotoxicity (LDH assay). All investigated extracts decreased viability of both normal and cancer colon cells in a dose-dependent manner; however, LS180 cells were more sensitive to the tested compounds. The results of MTT assay indicated that the tested extracts effectively decreased the mitochondrial metabolism of human colon cancer cells, which could be associated with the presence of hydrolysable tannins in all extracts except the PAL7, which revealed the weakest anticancer effect. Moreover, the highest impact in decrease of cancer cells viability by PAR7, PN7 and PRU7 correlate with their highest TPC and TTC values. Agrimoniin was shown to have prominent antioxidative, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer effects. Hoffman et al. (2016) found that agrimoniin-enriched fractions from rhizomes of P. erecta directly inhibit UVB-induced cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression and production of PGE2 in human keratinocytes (HaCaT), as well as in an in vivo model, and inhibit epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation. Shi et al. (2015) demonstrated that lyophilized strawberries (Fragaria x ananasa, Rosaceae) containing 16.2% agrimoniin downregulated the mRNA expression of COX-2, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS in AOM/DSS-induced colon cancer in mice. BrdU assay revealed a significant decrease of DNA synthesis in both colon cancer and non-cancer cells in response to all investigated extracts. The strongest antiproliferation effect in cancer cells was observed after treatment with PAR7 and PN7. Those extracts revealed to posess the highest total polyphenol and tannin contents. Notably, the antiproliferative effect of 5-FU observed in colon cancer cells was significantly stronger than that of the examined extracts. Similarly, data collected from colon epithelial cells revealed that five out of six investigated extracts in higher concentrations inhibited DNA synthesis stronger than the positive control. The in vivo bioavailability of high weight ellagitannins is relatively low. Ellagitannins at neutral or alkaline pH are hydrolysed with the release of free ellagic acid, which exerts a number of biological activities (Ismail et al., 2016). Whitley et al. (2003) found that the human colorectal adenocarcinoma cell line Caco-2 strongly accumulated ellagic acid and, furthermore, 93% of it was irreversibly bounded to cellular DNA and proteins. Moreover, ellagic acid significantly decreased the expression of genes involved in the p53, PI3K-Akt, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and TGF-β signaling pathways in human colorectal carcinoma cell line HCT 116 (Zhao et al., 2017). Ellagic acid also reduced the viability of human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line NPC-BM1 via activation of caspase-3 and inhibition of Bcl-2 and telomerase (Huang et al., 2009). Our results are in agreement with the studies by Kowalik and co-authors (2020), showing that selected extracts and fractions from aerial parts of P. alba significantly decreased proliferation of human colon cancer HT-29 cells. Additionally the authors found out that selected extracts and fractions from P. alba increased proliferation of human normal epithelial CCD 841 CoTr cells. Moreover, the tested samples damaged cell membranes and decreased their viability (Kowalik et al., 2020). Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, present in all investigated extracts, exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects. A recent study conducted on human colon cancer HCT 116 cells revealed that kaempferol 3-O-glucoside induces cell apoptosis by increasing expression of pro-apoptotic caspases (caspase 3, caspase 6, caspase 7, caspase 8, and caspase 9), protein p53, and Bax, and decreasing expression of anti-apoptotic proteins, cleaved caspase 3, and Bcl-2. Moreover, the investigated compound causes G0/G1 arrest, inhibits the expression of metalloproteinases MMP-2 and MMP-9, and decreases the activity of the NF-κB signalling pathway (Yang et al., 2021). Notably, tiliroside isolated from P. argentea exerted inhibitory activity against topoisomerase I and II and showed moderate cytotoxicity against human breast carcinoma cell line MCF-7 (Tomczyk et al., 2008). Finally, the LDH assay showed that the tested extracts even at the lowest concentration (25 μg/ml) significantly damaged the cell membranes of investigated colon cancer cells, releasing the high doses of LDH into the cell culture medium. The weakest effect was observed for PAL7, which may be due to the absence of hydrolysable tannins, which modify the permeability of cell membranes. However, strong observed effect of rest of tested extracts can be explained by high TTC. Moreover, the exerted the strongest cytotoxic effects of PAR7 and PRU7 among all extracts can be explained by their higher TPC and TTC values. At the same time, all tested samples were not cytotoxic against normal colon cells. In a recent paper, Borisowa and co-authors (2019) found that hydrolysable tannins selectively block calcium-activated chloride channels and form selective pores in the cell membrane (Borisova et al., 2019). Moreover, pedunculagin increased cytotoxicity of 5-FU against human liver cancer cells QGY-7703, probably through increased permeability of the cancer cell membrane, as observed by the authors through a microscope (Xiao et al., 2012). A recent study revealed that agrimoniin stimulates apoptosis via the mitochondria pathway, inducing activity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), which leads to mitochondria swelling and a decrease in energy production. Moreover, the authors found that agrimoniin is cytotoxic against K562 and HeLa cell lines (Fedotcheva et al., 2021). The in vivo effects of tannin-rich acetone extracts from selected Potentilla species may vary from obtained in vitro results. A recent study on aerial parts of P. anserina and rhizomes of P. erecta revealed that human intestinal microbiota convert ellagitannins to urolithins, which possess potent anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities (Piwowarski et al., 2014). Moreover, several studies suggest that the chronic application of tannin-rich extracts may lead to iron-deficiency anemia. Hydrolysable tannins posess antinutritional properties, due to their potential to complex iron ions and reduce their absorption (Petry et al., 2010). However, those effect may be offset by the development of formulations with modified release of extract or by the inclusion in diet of other bioactives, such as ascorbic acid, which prevents the inhibitory effect of polyphenols on iron absorption (Petroski and Minich, 2020). The acute complications of advanced stages of colorectal cancers includes a number of complications, such as bleeding, perforation and/or obstruction (Yang and Pan, 2014). Hydrolysable tannins are well known for their anti-bleeding properties. The tannin-rich extracts from Potentilla species may be used as potent, plant-based styptic agents as a complementary therapy in advanced stages of colorectal cancers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study reports, for the first time, analysis of the LC-PDA-HRMS profile of acetone extracts of selected Potentilla species. The analysis revealed the presence of several phenolic compounds, such as agrimoniin, pedunculagin, brevifolincarboxylic acid, ellagic acid, tiliroside, and tricoumaroyl spermidine. These secondary metabolites can be considered as chemophenetic markers for the genus Potentilla. Four of six investigated extracts (PAR7, PRE7, PRU7, PN7) showed great chemopreventive potential, manifested by the effective elimination of colon cancer cells, causing both damage to their cell membranes and inhibition of their proliferation and metabolic activity, with a simultaneous lack of a cytotoxic effect on normal colon epithelial cells and a significantly weaker effect on their metabolism and DNA synthesis compared to cancer cells. While it is impossible to specify the extract with the greatest therapeutic potential, these studies unequivocally showed that PAL7 had the lowest anti-cancer potential in a cellular model of colon cancer.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

DA and MT designed the research, DA performed experiments, analysed the data, and wrote the draft of the manuscript. MKL and JWS performed experiments, analysed the data, and revised the manuscript. AW and MT supervised the research and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2022.1027315/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Augustynowicz D. Jakimiuk K. Uysal S. Strawa J. W. Juszczak A. M. Zengin G. et al (2021a). LC-ESI-MS profiling of Potentilla norvegica and evaluation of its biological activities. S. Afr. J. Bot.142, 259–265. 10.1016/j.sajb.2021.06.042

2

Augustynowicz D. Latte K. P. Tomczyk M. (2021b). Recent phytochemical and pharmacological advances in the genus Potentilla L. sensu lato - an update covering the period from 2009 to 2020. J. Ethnopharmacol.266, 113412. 10.1016/j.jep.2020.113412

3

Bazylko A. Piwowarski J. P. Filipek A. Bonarewicz J. Tomczyk M. (2013). In vitro antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of extracts from Potentilla recta and its main ellagitannin, agrimoniin. J. Ethnopharmacol.149, 222–227. 10.1016/j.jep.2013.06.026

4

Borisova M. P. Kataev A. A. Sivozhelezov V. S. (2019). Action of tannin on cellular membranes: Novel insights from concerted studies on lipid bilayers and native cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Biomembr.1861, 1103–1111. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.03.017

5

Dirar A. I. Alsaadi D. H. M. Wada M. Mohamed M. A. Watanabe T. Devkota H. P. (2019). Effects of extraction solvents on total phenolic and flavonoid contents and biological activities of extracts from Sudanese medicinal plants. S. Afr. J. Bot.120, 261–267. 10.1016/j.sajb.2018.07.003

6

Edgar A. D. Levin R. Constantinou C. E. Denis L. (2007). A critical review of the pharmacology of the plant extract of Pygeum africanum in the treatment of LUTS. Neurourol. Urodyn.26, 458–463. 10.1002/nau.20136

7

Elejalde-Palmett C. De Bernonville T. D. Glevarec G. Pichon O. Papon N. Courdavault V. et al (2015). Characterization of a spermidine hydroxycinnamoyltransferase in Malus domestica highlights the evolutionary conservation of trihydroxycinnamoyl spermidines in pollen coat of core Eudicotyledons. J. Exp. Bot.66, 7271–7285. 10.1093/jxb/erv423

8

European Pharmacopoeia (2019). Tannins in herbal drugs. 10th ed. Luxembourg: European Commision.

9

Fecka I. (2009). Development of chromatographic methods for determination of agrimoniin and related polyphenols in pharmaceutical products. J. AOAC Int.92, 410–418. 10.1093/jaoac/92.2.410

10

Fecka I. Kucharska A. Z. Kowalczyk A. (2015). Quantification of tannins and related polyphenols in commercial products of tormentil (Potentilla tormentilla). Phytochem. Anal.26, 353–366. 10.1002/pca.2570

11

Fedotcheva T. A. Sheichenko O. P. Fedotcheva N. I. (2021). New properties and mitochondrial targets of polyphenol agrimoniin as a natural anticancer and preventive agent. Pharmaceutics13, 2089. 10.3390/pharmaceutics13122089

12

Feliciano R. P. Shea M. P. Shanmuganayagam D. Krueger C. G. Howell A. B. Reed J. D. (2012). Comparison of isolated cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Ait.) proanthocyanidins to catechin and procyanidins A2 and B2 for use as standards in the 4-(dimethylamino)cinnamaldehyde assay. J. Agric. Food Chem.60, 4578–4585. 10.1021/jf3007213

13

Gesek J. Jakimiuk K. Atanasov A. G. Tomczyk M. (2021). Sanguiins- promising molecules with broad biological potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 12972. 10.3390/ijms222312972

14

Grochowski D. M. Skalicka-Woźniak K. Orhan I. E. Xiao J. Locatelli M. Piwowarski J. P. et al (2017). A comprehensive review of agrimoniin. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci.1401, 166–180. 10.1111/nyas.13421

15

Grochowski D. M. Strawa J. W. Granica S. Tomczyk M. (2020). Secondary metabolites of Rubus caesius (Rosaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol.92, 104111. 10.1016/j.bse.2020.104111

16

Gudej J. Tomczyk M. (1999). Polyphenolic compounds from flowers of Ficaria verna Huds. Acta Pol. Pharm.56, 475–476.

17

Hagerman A. E. (1988). Extraction of tannin from fresh and preserved leaves. J. Chem. Ecol.14, 453–461. 10.1007/BF01013897

18

Hoffman J. Casetti F. Bullerkotte U. Haarhaus B. Vagedes J. Schempp C. M. et al (2016). Anti-inflammatory effects of agrimoniin-enriched fractions of Potentilla erecta. Molecules21, 792.

19

Huang S. T. Wang C. Y. Yang R. C. Chu C. J. Wu H. T. Pang J. H. (2009). Phyllanthus urinaria increases apoptosis and reduces telomerase activity in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Forsch. Komplementmed.16, 34–40. 10.1159/000194154

20

Ismail T. Calcabrini C. Diaz A. R. Fimognari C. Turrini E. Catanzaro E. et al (2016). Ellagitannins in cancer chemoprevention and therapy. Toxins (Basel)8, 151. 10.3390/toxins8050151

21

Kowalik K. Paduch R. Strawa J. W. Wiater A. Wlizło K. Waśko A. et al (2020). Potentilla alba extracts affect the viability and proliferation of non-cancerous and cancerous colon human epithelial cells. Molecules25, 3080. 10.3390/molecules25133080

22

Langner E. Lemieszek M. K. Rzeski W. (2019). Lycopene, sulforaphane, quercetin, and curcumin applied together show improved antiproliferative potential in colon cancer cells in vitro. J. Food Biochem.43, e12802. 10.1111/jfbc.12802

23

Lee I. R. Yang M. Y. (1994). Phenolic compounds from Duchesnea chrysantha and their cytotoxic activities in human cancer cell. Arch. Pharm. Res.17, 476–479. 10.1007/BF02979129

24

Luo S. Guo L. Sheng C. Zhao Y. Chen L. Li C. et al (2020). Rapid identification and isolation of neuraminidase inhibitors from mockstrawberry (Duchesnea indica Andr.) based on ligand fishing combined with HR-ESI-Q-TOF-MS. Acta Pharm. Sin. B10, 1846–1855. 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.04.001

25

Manyelo T. G. Sebola N. A. Hassan Z. M. Mabelebele M. (2020). Characterization of the phenolic compounds in different plant parts of Amaranthus cruentus grown under cultivated conditions. Molecules25, 4273. 10.3390/molecules25184273

26

Mueller-Harvey I. (2001). Analysis of hydrolysable tannins. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol.91, 3–20. 10.1016/s0377-8401(01)00227-9

27

Okuda T. Yoshida T. Hatano T. Iwasaki M. Kubo M. Orime T. et al (1992). Hydrolysable tannins as chemotaxonomic markers in the Rosaceae. Phytochemistry31, 3091–3096. 10.1016/0031-9422(92)83451-4

28

Okuda T. Yoshida T. Kuwahara M. Memon M. U. Shingu T. (1982). Agrimoniin and potentillin, an ellagitannin dimer and monomer having an α-glucose core. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun.3, 163–164. 10.1039/c39820000163

29

Patel S. B. Ghane S. G. (2021). Phytoconstituents profiling of Luffa echinata and in vitro assessment of antioxidant, anti-diabetic, anticancer and anti-acetylcholine esterase activities. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.28, 3835–3846. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.03.050

30

Peng B. Hu Q. Liu X. Wang L. Chang Q. Li J. et al (2009). Duchesnea phenolic fraction inhibits in vitro and in vivo growth of cervical cancer through induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Exp. Biol. Med.234, 74–83. 10.3181/0806-RM-204

31

Petroski W. Minich D. M. (2020). Is there such a thing as “anti-nutrients”? A narrative review of perceived problematic plant compounds. Nutrients12, 2929. 10.3390/nu12102929

32

Petry N. Egli I. Zeder C. Walczyk T. Hurrell R. (2010). Polyphenols and phytic acid contribute to the low iron bioavailability from common beans in young women. J. Nutr.140, 1977–1982. 10.3945/jn.110.125369

33

Piwowarski J. P. Granica S. Zwierzyńska M. Stefańska J. Schopohl P. Melzig M. F. et al (2014). Role of human gut microbiota metabolism in the anti-inflammatory effect of traditionally used ellagitannin-rich plant materials. J. Ethnopharmacol.155, 801–809. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.06.032

34

Polumackanycz M. Śledzinski T. Goyke E. Wesolowski M. Viapiana A. (2019). A comparative study on the phenolic composition and biological activities of Morus alba L. commercial samples. Molecules24, 3082. 10.3390/molecules24173082

35

Shi N. Clinton S. K. Liu Z. Wang Y. Riedl K. M. Schwartz S. J. et al (2015). Strawberry phytochemicals inhibit azoxymethane/dextran sodium sulfate-induced colorectal carcinogenesis in crj: CD-1 mice. Nutrients7, 1696–1715. 10.3390/nu7031696

36

Slinkard K. Singleton V. L. (1977). Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am. J. Enol. Vitic.28, 49–55.

37

Strawa J. Wajs-Bonikowska A. Jakimiuk K. Waluk M. Poslednik M. Nazaruk J. et al (2020). Phytochemical examination of Woolly Burdock Arctium tomentosum leaves and flower heads. Chem. Nat. Compd.56, 345–347. 10.1007/s10600-020-03027-w

38

Sung H. Ferlay J. Siegel R. L. Laversanne M. Soerjomataram I. Jemal A. et al (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca. Cancer J. Clin.71, 209–249. 10.3322/caac.21660

39

Sut S. Dall’acqua S. Uysal S. Zengin G. Aktumsek A. Picot-Allain C. et al (2019). LC-MS, NMR fingerprint of Potentilla argentea and Potentilla recta extracts and their in vitro biopharmaceutical assessment. Ind. Crops Prod.131, 125–133. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.01.047

40

Szajwaj B. Moldoch J. Masullo M. Piacente S. Oleszek W. Stochmal A. (2011). Amides and esters of phenylpropenoic acids from the aerial parts of Trifolium pallidum. Nat. Prod. Commun.6, 1934578X1100600–1296. 10.1177/1934578x1100600921

41

Tomczyk M. Dozdowska D. Bielawska A. Bielawski K. Gudej J. (2008). Human DNA topoisomerase inhibitors from Potentilla argentea and their cytotoxic effect against MCF-7. Pharmazie63, 389–393.

42

Tomczyk M. Gudej J. (2005). Polyphenolic compounds from Rubus saxatilis. Chem. Nat. Compd.41, 349–351. 10.1007/s10600-005-0148-1

43

Tomczyk M. Latte K. P. (2009). Potentilla-a review of its phytochemical and pharmacological profile. J. Ethnopharmacol.122, 184–204. 10.1016/j.jep.2008.12.022

44

Tomczyk M. Pleszczyńska M. Wiater A. (2010). Variation in total polyphenolics contents of aerial parts of Potentilla species and their anticariogenic activity. Molecules15, 4639–4651. 10.3390/molecules15074639

45

Tomczyk M. (2011). Secondary metabolites from Potentilla recta L. And Drymocallis rupestris (L.) Soják (syn. Potentilla rupestris L.) (Rosaceae). Biochem. Syst. Ecol.39, 893–896. 10.1016/j.bse.2011.07.006

46

Whitley A. C. Stoner G. D. Darby M. V. Walle T. (2003). Intestinal epithelial cell accumulation of the cancer preventive polyphenol ellagic acid-extensive binding to protein and DNA. Biochem. Pharmacol.66, 907–915. 10.1016/s0006-2952(03)00413-1

47

Wilkes S. Glasl H. (2001). Isolation, characterization, and systematic significance of 2-pyrone-4, 6-dicarboxylic acid in Rosaceae. Phytochemistry58, 441–449. 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00256-4

48

Xi Y. Xu P. (2021). Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol.14, 101174. 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101174

49

Xiao S. Wen B. Zhuang H. Wang J. Tang J. Chen H. et al (2012). “Extraction and antitumor activity of pedunculagin from eucalyptus leaves,” in 2012 International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Biotechnology, Macau, Macao, 28-30 May 2012, 280–282.

50

Yang M. Li W. Y. Xie J. Wang Z. L. Wen Y. L. Zhao C. C. et al (2021). Astragalin inhibits the proliferation and migration of human colon cancer HCT116 cells by regulating the NF- κB signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol.12, 639256. 10.3389/fphar.2021.639256

51

Yang X. F. Pan K. (2014). Diagnosis and management of acute complications in patients with colon cancer: Bleeding, obstruction, and perforation. Chin. J. Cancer Res.26, 331–340. 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2014.06.11

52

Zhang J. Liu C. Huang R. Z. Chen H. F. Liao Z. X. Sun J. Y. et al (2017). Three new C-27-carboxylated-lupane-triterpenoid derivatives from Potentilla discolor Bunge and their in vitro antitumor activities. PLoS One12, e0175502. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175502

53

Zhao J. Li G. Bo W. Zhou Y. Dang S. Wei J. et al (2017). Multiple effects of ellagic acid on human colorectal carcinoma cells identified by gene expression profile analysis. Int. J. Oncol.50, 613–621. 10.3892/ijo.2017.3843

Summary

Keywords

Potentilla , Rosaceae, LC-PDA-HRMS, polyphenols, colorectal cancer, LS180 cells, cytotoxicity

Citation

Augustynowicz D, Lemieszek MK, Strawa JW, Wiater A and Tomczyk M (2022) Anticancer potential of acetone extracts from selected Potentilla species against human colorectal cancer cells. Front. Pharmacol. 13:1027315. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2022.1027315

Received

24 August 2022

Accepted

13 September 2022

Published

29 September 2022

Volume

13 - 2022

Edited by

Javier Echeverria, University of Santiago, Chile

Reviewed by

Monika Anna Olszewska, Medical University of Lodz, Poland

Dinesh Kumar, Chitkara University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2022 Augustynowicz, Lemieszek, Strawa, Wiater and Tomczyk.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michał Tomczyk, michal.tomczyk@umb.edu.pl

This article was submitted to Ethnopharmacology, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.