Abstract

Alternariol is a toxic metabolite of Alternaria fungi and studies have shown multiple potential pharmacological effects. To outline the anticancer effects and mechanisms of alternariol and its derivatives based on database reports, an updated search of PubMed/MedLine, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and Scopus databases was performed with relevant keywords for published articles. The studies found to suggest that this mycotoxin and/or its derivatives have potential anticancer effects in many pharmacological preclinical test systems. Scientific reports indicate that alternariol and/or its derivatives exhibit anticancer through several pathways, including cytotoxic, reactive oxygen species leading to oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction-linked cytotoxic effect, anti-inflammatory, cell cycle arrest, apoptotic cell death, genotoxic and mutagenic, anti-proliferative, autophagy, and estrogenic and clastogenic mechanisms. In light of these results, alternariol may be one of the hopeful chemotherapeutic agents.

1 Introduction

Chemotherapy is a type of anticancer treatment that uses one or more chemical substances (extracts from natural substances or products of chemical synthesis) that stop the multiplication of cancer cells, either by destroying them or by stopping their division. Chemotherapy is an essential component of the pharmacotherapeutic management of cancer. (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021b; GBD, 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators, 2022). On the other hand, the resistance of cancer cells towards chemotherapeutic drugs has become prevalent, being associated with unfavourable clinical evolution in cancer patients directly and indirectly (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021e; Sharma et al., 2022). The progress of new drug research and development may overcome the occurrence of drug resistance (Ali et al., 2022b). It has been also reported that natural products and derivatives with diverse chemical structures and pharmacological effects serve as useful compounds against cancer and drug-resistant cancer (Ali et al., 2022a; Dhyani et al., 2022b; Kitic et al., 2022; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2022a). Mycotoxins are types of toxins produced by a variety of fungal species of crops or stored commodities. Mycotoxins appear as primary or secondary contaminants via the carryover effect in the food chain (Degen, 2017). Due to various biological effects, mycotoxins have come to the attention of scientists in the context of research done to discover and develop new anticancer drugs (Islam, 2017; Islam et al., 2018). Generally, mycotoxins are ubiquitous and unavoidable harmful fungal products and vary significantly in structure and biochemical effects. These toxins cause disease in both animals and humans and are found in almost all types of foods, with a higher prevalence in hot, humid environments (El Khoury et al., 2019). Unfortunately, most of the published data has concerned the major mycotoxins aflatoxins, ochratoxin A, zearalenone, fumonisins and trichothecenes, especially deoxynivalenol (Smith et al., 2016), although, there are aspects of mycotoxin relations with strain improvement strategies and genetic modification for improved detoxifying properties in test systems (Pfliegler et al., 2015).

Alternariol (AOH), a toxic mycotoxins metabolite of Alternaria fungi, is an essential contaminant in cereals and fruits. Alternaria fungi are plant and human pathogens, saprophytes, a strong allergen and exposure has been associated with allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, chronic rhinosinusitis and asthma (Grover and Lawrence, 2017; Aichinger et al., 2021). Mycotoxins enter the body through contaminated food, but can also enter the airway or through direct skin contact. In general, mycotoxins are resistant to high temperatures, and many mycotoxins are also resistant to industrial food processing, so to have mycotoxin-free foods, the raw material (wheat, milk, vegetables, meat, etc.) must be analyzed. Because they are resistant to processing, they can also be found in highly processed foods such as bread, breakfast cereals, wine, and beer. Many pharmacological activities, including antifungal (da Cruz Cabral et al., 2019), anti-inflammatory (Kollarova et al., 2018), and anticancer effects have been done (Meena and Samal, 2019). This updated review sketches a current scenario of AOH’s anticancer effect and possible action mechanisms behind it based on database information.

2 Review methodology

A literature study was conducted up to December 2021 using the following databases: PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Web of Science, Scopus, and the American Chemical Society using the next MeSH terms: “Alternariol,” “Alternariol monomethyl ether,” “Alternaria/metabolism,” “Mycotoxins,” “Cell Line,” “Tumor,” “Cell Survival/drug effects,” “Humans,” “Mycotoxins/toxicity,” “Reactive Oxygen Species.” No language restrictions were imposed. Articles were evaluated in detail and summarized information on the dose, concentration, administration route, experimental model, results discussion, conclusion, and the proposed action mechanism.

2.1 Inclusion criteria

1. Pharmacological studies carried out in vitro, in vivo with or without using experimental animals, including humans and their derived tissue and cells

2. Studies with AOH and its derivatives and joint effects with other substances (including drugs or chemicals/biochemicals)

3. Studies with or without proposing activity mechanisms.

2.2 Exclusion criteria

1. Studies with extracts without phytochemical analysis

2. Studies with homeopathic drugs

3. Other studies of AOH uncover the current topic.

3 Stability, bioavailability and pharmacokinetics

A recent study showed a significant reduction in AOH when exposed to a temperature of 35°C, and very high temperatures above 100°C significantly affect its stability. Compared to this, its derivative, alternariol monomethyl ether (AME) is much more stable; at high temperatures of 80°C–110°C (Estiarte et al., 2018). AOH suffers several reactions of biotransformation, as has been demonstrated by studies performed in vivo, in rat liver slices, cell culture or purified enzymes. The identified chemical modifications of AOH include hydroxylation (phase I biotransformation), sulfation and glucuronidation (phase II biotransformation), which are executed mainly by cytochrome P450 isoforms (Tran et al., 2020). The principal organ of AOH metabolization is the liver, although other organs like the kidneys, the bladder and components of the gastrointestinal tract have also been involved. Of note is the lack of relevant participation of gut microbiota in the biotransformation of AOH (Lemke et al., 2016). Some enzymes responsible for AOH metabolization are uridine 5′-diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase, glutathione S-transferase and CYP1A1 (Appel et al., 2021). The last one is responsible for hydroxylation at C-2, C-4, and C-8. Subsequently, 4-hydroxy-AOH is glycosylated to 3-glucoside (58%) and 9-glucoside (5%) in the whole-cell system. The metabolite 9-diglucoside can also be hydrolyzed to 9-glucoside. Some metabolites of AOH, as catechols formed by its hydroxylation, can also be methylated and hydroxylated.

In vivo studies performed in rodents reveal that a high percentage (85%–91%) of AOH given orally is excreted in the faeces, and a low percentage in the urine (>2.6%), with 0.8% urine excretion of alternariol-3-sulphate (Schuchardt et al., 2014). The blood concentration of AOH only reaches 0.06% after 24 h when 2000 mg/kg are administrated orally. However, when doses were applied in triplicate at 0, 24 and 45 h, AOH reached a blood concentration of 0.5 µM after 3 h of administration. The study performed by Schuchardt et al. (2014), could detect 4, 10, 8, and 2 hydroxy metabolites of AOH in urine the following three days after the triple doses. Using polarized human colon adenocarcinoma Caco-2 cells culture as a model of the intestinal barrier, it has been established that between 23% and 26% of the apically applied AOH crosses the cell barrier, founding several metabolites on the basolateral side (Appel et al., 2021). When CaCo-2 cells were cultured with AOH or 9-glucoside alternariol, a similar distribution of derivates were found on the apical and basolateral side. Particularly, after 3 h of apical exposure, 45% of the initial compounds of the supernatant corresponded to 9-glucoside, 15% to 3-glucuronide, 14% to 3-sulphate and 11% to 9-glucuronide. Using AOH unconjugated molecule, there was 8% of the recovered compounds. Specifically, in the cell, the glucuronides and the glucoside also could be detected. The 3-glucoside plant metabolite displays a different distribution in the whole cell system, showing over 90% of metabolites recovered. Also, in the cells, only traces of the same metabolites were detected, including the unmodified AOH. On the other hand, 9-diglucoside has no significant absorption. In summary, the glucuronides and sulfates of AOH showed moderate absorption (20%–70%), meanwhile, the free mycotoxin and the 9-glycoside have higher absorption (Burkhardt et al., 2009). These data reveal that AOH and its metabolites are significatively absorbed by epithelial cells, but the localization of the glycosylation position affects its absorption and metabolization.

4 Anticancer mechanisms and targeting signaling pathways by alternariol

4.1 Cytotoxicity

Cytotoxic effect test for an anticancer agent is the first option as it tells whether the agent should be considered an anticancer drug or not (Zlatian et al., 2015; Docea et al., 2016). In this context, time and concentration-dependent cytotoxic effect measurements are crucial (Docea et al., 2012; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021c). Due to its cytotoxic properties, AOH could be a good candidate for exploring anticancer effects (Figure 2). This possibility was evaluated in a recent study by Palanichamy et al. (2019) where human hepatocarcinoma cells (HUH-7), and human alveolar epithelial cells (A549) were exposed to purified AME for 48 h. HUH-7 cells were the most sensitive to the cytotoxic effect, with an IC50 of 50 μM and showing a cell cycle arrest at the G1 phase. Within the same study, AME was able to protect from neoplastic transformation induced by diethylnitrosamine in rat livers.

AOH and alternariol monomethyl ether (AME) are evident to show strong cytotoxic effect (IC50 values of 3.12–3.17, and 4.82–4.94 μg/mL), while AOH derivative, alternariol 4-methyl-10-acetyl ether, and alternariol 3,9-dimethyl ether exhibited weak activities (IC50 values > 50 μg/mL) against human epidermoid carcinoma (KB and KBv200) cell lines (Tan et al., 2008). AOH (3.125–100 μM) was found to exert cytotoxic effects in CaCo-2 cells (Vila-Donat et al., 2015). In another study, AOH (12.5–100 µM) was found to augment reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and eventually exert a cytotoxic effect in CaCo-2 cells (Chiesi et al., 2015). Moreover, AOH and AME at 3.125–100 µM exerted cytotoxic and combined cytotoxic effects in CaCo-2 cells (Fernández-Blanco et al., 2016).

4.2 Induced oxidative stress in cancer cells

Chemotherapeutic agents act through many pathways (Mitrut et al., 2016; Hossain et al., 2021). Chronic ROS induction and mitochondrial dysfunction-linked exerting a cytotoxic effect are one of them (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2020; Scheau et al., 2021). Therefore, the regulation of oxidative stress is an essential factor in anticancer therapies (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021a; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021c). AOH (25–200 µM) caused ROS generation, leading to mitochondrial dysfunction-dependent cytotoxic effect in human colon carcinoma (HCT116) cells (Bensassi et al., 2012). AOH-induced ROS production and an increase in cellular stress were also evident in RAW264.7 macrophages (Solhaug et al., 2012; Solhaug et al., 2014), and CaCo-2 cells (Fernández-Blanco et al., 2014; Fernández-Blanco et al., 2015). In another study, AOH and AME at 0.1–50 µM modulated the redox balance of HT29 cells (human colon cancer cell line), but without apparent adverse effect on DNA integrity (Tiessen et al., 2013).

4.3 Effects on inflammation and immunity

There is a relationship between inflammation and cancer (Jain et al., 2021). Chronic inflammation can induce tumorigenesis by initiating and perpetuating local inflammatory processes that promote the proliferation and dissemination of tumor cells. Therefore, inflammatory pathways may be targeted by alternariol in an attempt to control cancer (Ali et al., 2022a; Hossain et al., 2022; Iqbal et al., 2022).

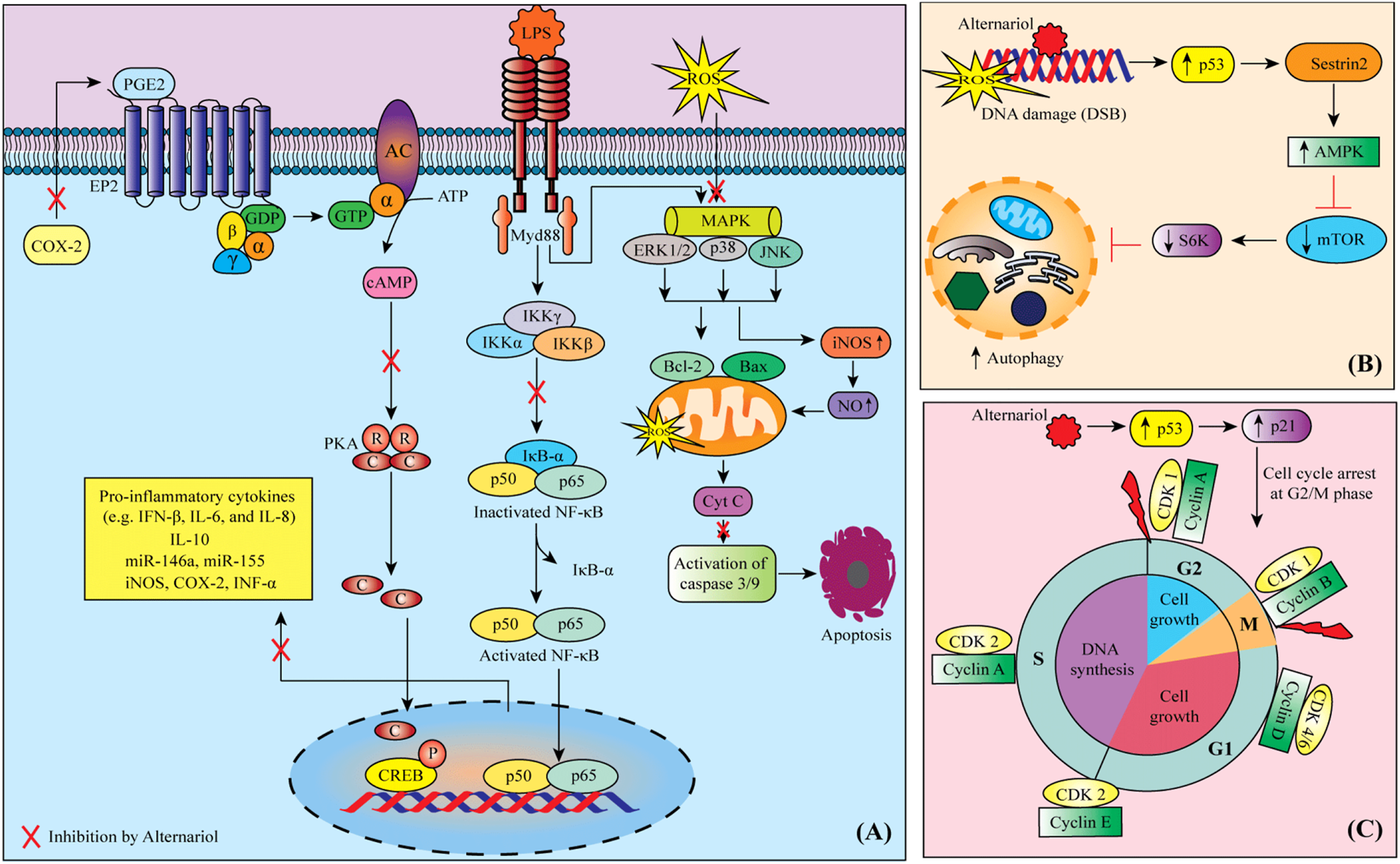

MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is vital for the adaptation of the cell to stress and its activation is highly involved in the inflammation process (Motyka et al., 2023; Prasher et al., 2023). The cell inflammation induction by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) triggers a series of signaling pathways including MAPK and nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) (Li et al., 2016; Capó et al., 2021; Pezzani et al., 2023). MAPKs are involved in the phosphorylation of JNK, ERK and p38 which regulate the expression of MSK 1/2 and then p65 (Xie et al., 2019; Garzoli et al., 2022; Li et al., 2023). Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) are also key enzymes involved in inflammation and cell stress, being NO an important regulator of COX-2 expression and activity (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2022c; Li et al., 2023). AOH showed to lead to the phosphorylation of cAMP response element-binding (CREB) and increased the expression of COX-2 (Bansal et al., 2019).

AOH (12.5–50 µg/animal (single topical) in mice showed dermal toxicity by activating the EP2/cAMP/p-CREB signaling cascade (Bansal et al., 2019). In this study, an increase in bi-fold thickness, as well as hyperplasia and higher production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) along with cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), COX-2, cyclin D1 as well as prostanoid EP2 receptor in the skin, was also seen. Moreover, AOH (1–20 µM) showed to suppress the LPS-induced NF-κB pathway activation, decreased the secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-8, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and induced IL-10 secretion (Kollarova et al., 2018). In the latter case, a dose-dependent downregulation of miR-146a while upregulation of miR-155 was also seen in THP-1-derived macrophage cells. AOH and AME have been reported to counteract pro-inflammatory stimuli in different cell models (Grover and Lawrence, 2017; Kollarova et al., 2018; Schmutz et al., 2019; Aichinger, 2021). The hematology and serum biochemistry results obtained in a study performed in male Sprague-Dawley rats showed that the administration of AME (1.84, 3.67, or 7.35 μg/kg body weight/day) for 28 days compromises the immune system (Tang et al., 2022). The suggested mechanisms involved are the cholesterol-like intercalation into the cell membranes of macrophages (Del Favero et al., 2020) and the interaction with NF-κB signaling mediated via Nrf2 activation (Khandia et al., 2019).

4.4 Cell cycle arrest

All cells that multiply do so through what is known as the cell cycle (Asgharian et al., 2022; Sharma et al., 2022). The cell cycle is a succession of carefully controlled phases so that if things do not go well in a certain phase (for example, genetic alterations occur), the cell cannot progress to the next phases of the cycle (Javed et al., 2022; Chaudhary et al., 2023). In cancer, these checkpoints are disrupted (Ianoși et al., 2019; Limas and Cook, 2019; Dhyani et al., 2022a). Some of the drugs and bioactive natural compounds used in cancer treatment, can restore normal signaling and control pathways or disrupt the activity of signaling and control pathways that no longer function normally (Salehi et al., 2019; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2022b; Taheri et al., 2022). In porcine endometrial cancer cells, AOH (0.39-15.5 µM) decreased cell number and reduced cells in the S phase together with the arrest of the cells in the G0/G1 phase (Wollenhaupt et al., 2008). It is also found to cause abnormal nuclear morphology and cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells (Solhaug et al., 2013; Solhaug et al., 2014).

4.5 Apoptosis of cancer cells

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in our body in which many intrinsic and extrinsic events lead to characteristic cell changes (morphology) and death (Amin et al., 2022; Irfan et al., 2022; Javed et al., 2022). Many anticancer drugs are evident to enhance this process of cell death (Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021b; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021e; Dhyani et al., 2022b). AME (25–200 µM) induced cell death in human colon carcinoma (HCT116) cells by activating the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis (Bensassi et al., 2011). In the same cell line, AOH induced apoptosis via the mitochondria-dependent pathway, characterized by a p53 activation, an opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP), triggering a loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (DWm), and a downstream generation of anion superoxide and caspase −9 and −3 activation (Bensassi et al., 2012). In addition, the deficiency of the pro-apoptotic protein Bax was also observed in this study. AOH (20 µM) and AME (40 µM) were found to induce CYP1A1 and cause apoptotic cell death in murine hepatoma (Hepa-1c1c7, Hepa-1c1c4) cells (Schreck et al., 2012).

4.6 Genotoxicity and mutagenic effects

Anticancer drugs can also act by exerting genotoxic and mutagenic effects on cancer cells. These are also reported as cytotoxic mechanisms (Buga et al., 2019; Islam et al., 2021; Asgharian et al., 2022). An earlier report suggests that AOH inhibited DNA strand breakage in an in vitro model (Xu et al., 1996). AOH (15–30 µM), in RAW 264.7 cells, caused DNA damage via phosphorylation of histone H2AX and checkpoint kinase (Chk-1/2). Activated p53 and increased the expression of p21, Cyclin B, MDM2, and Sestrin 2 likewise, the level of several miRNAs was also affected (Solhaug et al., 2012). AOH, AME, and altertoxin II (0–20 µM) caused DNA strand breaking and showed a mutagenic effect in cultured Chinese hamster V79 cells (Fleck et al., 2012). In this study, altertoxin II was more potent than AOH and AME. AOH, in RAW264.7 macrophage cells, caused DNA damage (double-strand breakage) (Solhaug et al., 2014). In a recent study, AOH and altertoxin II have been also evident to cause DNA damage and exert genotoxic effects in nucleotide excision repair-deficient cells (Fleck et al., 2016). AOH (10 µM) was found to exert mutagenic effects in V79 and mouse lymphoma L5178Y tk ± cells (Brugger et al., 2006). Moreover, in a molecular docking study, AOH and AME were found to disrupt topoisomerases and lead to genotoxic outcomes (Dellafiora et al., 2015).

4.7 Anti-proliferative effect

Cancer is characterized by the uncontrolled proliferation of abnormal cells (Salehi et al., 2021; Sharifi-Rad et al., 2021d). AOH exerted an anti-proliferative effect in CaCo-2 cells (Vila-Donat et al., 2015). AOH is also evident to exert an anti-proliferative influence on RAW 264.7 (Solhaug et al., 2012) and CaCo-2 cells (Fernández-Blanco et al., 2014). AOH also inhibited cell proliferation by interfering with the cell cycle in Ishikawa and V79 cells (Lehmann et al., 2006).

4.8 Autophagy

Anticancer drugs can induce autophagy in cancer cells (Sani et al., 2017). In a study, of RAW264.7 macrophage cells when treated with AOH (15–60 µM) the autophagy marker LC3 was markedly increased (Solhaug et al., 2014). In this study, activation of p53 and the Sestrin2-AMPK-mTOR-S6K signaling pathway was also seen.

Anticancer effects of AOH and/or its derivatives from in vitro studies have been shown in Table 1. The chemical structures of AOH and its most representative derivatives are represented in Figure 1.

TABLE 1

| AOH/Derivatives | in vitro cell Lines/IC50 | Potential anticancer mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOH | colon cancer cells | AOH 65 μM | Bensassi et al. (2012) |

| HCT116 | ↑apoptosis | ||

| HCT116 Bax-KO | - ↑ROS, ↓O2 radicals | ||

| (HCT116 deficient for Bax cells) | - ↑mitochondrial PTP | ||

| IC50 = 25–200 µM | - ↓DWm | ||

| control: H2O21 mM | AOH 50 μM | ||

| ↑apoptosis, ↑caspase-3, ↑caspase-9, ↑ p53, ↑DNA damage, ↑Bax, ↑mitochondrial permeabilization ↓ionic homeostasis ↑membrane rupture | |||

| ↑death-promoting factors cytC, EndoG | |||

| colon carcinoma cells | AOH 3,125 μM | Vila-Donat et al. (2015) | |

| CaCo-2 | ↑LPO, ↑ROS, ↑oxidative stress, ↑cytotoxicity | ||

| IC50 = 3.125–100 μM | AOH 50–100 µM | ||

| control: 1% DMSO | ↓cell proliferation | ||

| colon carcinoma cells | ↓ROS | Chiesi et al. (2015) | |

| CaCo-2 | ↑cytotoxicity | ||

| IC50 = 12.5–100 µM | ↓cells viability | ||

| control: 1% DMSO | |||

| murine macrophage cell lines | AOH 30 μM | Solhaug et al. (2014) | |

| RAW 264.7 | ↑ROS, ↑cellular stress, ↑cell cycle arrest, ↑ autophagy, ↑ senescence, ↑DNA damage, ↑p53 ↑topoisomerase, ↑ Sestrin2-AMPK-mTOR-S6Ks | ||

| IC50 = 15–60 µM | ↑abnormal nuclear morphology, | ||

| positive control: salt solution (EBSS) | ↑vacuolization of the cytoplasm | ||

| colon carcinoma cells | ↑ROS | Fernández-Blanco et al. (2014) | |

| CaCo-2 | ↑oxidative stress | ||

| IC50 = 3.125–100 µM | ↓ cancer cells proliferation | ||

| control: 1% DMSO | |||

| porcine endometrial cells | ↓cells number | Wollenhaupt et al. (2008) | |

| IC50 = 0.39–15.5 µM | ↓cells in the S phase | ||

| control: 1% DMSO | ↑arrest of the cells in the G0/G1 phase | ||

| neoplastic Chinese hamster cell lines | DNA strand breakage | Fleck et al. (2012) | |

| V79 | ↑cell cycle arrest in the G2/M phase | ||

| IC50 = 0.1–5 µM | ↑HPRT gene mutations | ||

| control: 1% DMSO | |||

| recombinant yeast | ↑androgenic response | Stypuła-Trębas et al. (2017) | |

| Saccharomycescerevisiae strains | |||

| EC50 = 269.4 μM. | |||

| control: 1% DMSO | |||

| AOH | murine hepatoma cells | ↑ CYP1A1 | Schreck et al. (2012) |

| AME | Hepa-1c1c7 | ↑apoptosis | |

| Hepa-1c1c4 | ↓ cell numbers | ||

| Hepa c1c12 | |||

| IC50 = 20–40 µM | |||

| control: 0.4% DMSO | |||

| human colorectal cancer cell line | ↑cytotoxicity | Tiessen et al. (2013) | |

| HT29 | ↑intracellular redox status, ↑Nrf2, ↑GSH, ↑GST, ↑oxidative DNA-damage | ||

| IC50 = 0.1–50 µM | ↑Nrf2/ARE-dependent gene transcription | ||

| control: 1% DMSO | |||

| CaCo-2 cells | ↑ cytotoxicity, ↓ cell viability | Fernández-Blanco et al. (2016) | |

| IC50 = 3.125–100 µM | ↓CaCo-2 cells growth | ||

| control:1% DMSO | AOH + AME→ ↑cytotoxicity effect | ||

| AOH, AME, alternariol 4-methyl-10-acethyl ether alternariol 3,9-dimethyl ether | human oral squamous carcinoma cell line KB | ↑cytotoxicity | Tan et al. (2008) |

| multiple-drug resistant human oral squamous cells KBv200 | |||

| IC50 = 3.12–3.17 μg/mL | |||

| IC50 = 82–4.94 μg/mL | |||

| control: 0.1% DMSO | |||

| AOH | neoplastic Chinese hamster cell lines | ↑DNA damage | Fleck et al. (2016) |

| Altertoxin II | V79 | ↑genotoxicity | |

| hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines | |||

| HepG2 | |||

| Nucleotide excision repair-deficient cells | |||

| AOH, AME | neoplastic Chinese hamster cell lines | AOH 0.75 μM: | Fleck et al. (2012) |

| Altertoxin II | V79 | ↑mutagenic effect | |

| IC50 = 0–20 µM | ↑HPRT mutation, ↑DNA damage | ||

| positive control: salt solution (EBSS) | altertoxin II was more potent than AOH and AME | ||

| AME | human colon carcinoma cells | ↑cell death | Bensassi et al. (2011) |

| HCT116 | ↑apoptosis | ||

| IC50 = 25–200 µM |

Anticancer effects of alternariol and/or its derivatives in different in vitro experimental studies.

Abbreviations and symbols: ↑ increased, ↓ decreased, AIF, apoptosis-inducing factor; AME, alternariol monomethyl ether; AOH, alternariol; CYP, cytochrome c, DMSO, dimethylsulfoxide; DWm, mitochondrial transmembrane potential; EBSS, Earle’s balanced salt solution, EndoG endonuclease G, GSH, glutathione; GST, glutathione transferase; HPRT, hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase; LPO, lipid peroxidation; NQO, 4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide, Nrf2 nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, PTP, mitochondrial permeability transition pore, and ROS, reactive oxygen species.

FIGURE 1

The chemical structures of Alternariol and its derivatives and their anticancer potential mechanisms. Symbols: ↑ (increased), ↓(decreased).

FIGURE 2

Possible mechanisms of anti-cancer activity of alternariol: (A) Alternariol induces apoptosis through targeting multiple deregulated signaling pathways in cancer cells, (B) Possible autophagy mechanism of alternariol through the activation of Sestrin2-AMPK-mTOR-S6K signaling pathway, (C) alternariol moderates the activity of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases to induce cell cycle arrest at G2/M phase. Abbreviations and symbols: ↑ increased, ↓ decreased, CDK cyclin-dependent kinase, COX-2 cyclooxygenase-2, CREB cAMP response element-binding, IFN interferon, IL interleukin, iNOS inducible nitric oxide synthase, LPS lipopolysaccharide, MAPK mitogen-activated protein kinase, mTOR mammalian target of rapamycin, PGE2 prostaglandin E2, PKA protein kinase A, ROS reactive oxygen species.

4.9 Other effects

AOH (0–10 µM) showed estrogenic and clastogenic potential, where replacement of E2 from human estrogen receptors α and β and increased the transcription of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and its enzymatic activity in Ishikawa and V79 cells (human endometrial adenocarcinoma cell lines) (Lehmann et al., 2006). In this study, AOH also induced kinetochore-negative micronucleus in both cell lines. AOH and AOH derivatives, such as AME, alternariol-9-methyl ether-3-O-sulphate, and maculosin in leukemia, colon, lung and liver cancer cell lines, showed an efficient anticancer activity against leukemia, colon, lung and liver cancer cells (Hawas et al., 2015).

AOH (0.1–1000 ng/mL) in steroid hormone receptors, oestrogens androgens, progestagens, glucocorticoids and the H295R steroidogenesis assay, exhibited a weak oestrogenic response and binding of progesterone to the progestagen receptor was shown to be synergistically increased in the presence of AOH (Frizzell et al., 2013). In this study, was not observed a significant change in testosterone and cortisol hormones, but a significant increase in estradiol and progesterone production. Only one gene NR0B1 was downregulated, whereas expression of mRNA of CYP1A1, MC2R, HSD3B2, CYP17, CYP21, CYP11B2 and CYP19 was upregulated. On the other hand, in yeast estrogen and androgen reporter bioassays, AOH induced a full androgenic response in this eukaryotic test system (EC50 of 269.4 μM) (Stypuła-Trębas et al., 2017).

5 Toxicology and safety data

The toxicity of AOH has been studied since the 70s, mainly through in vitro models (Pero et al., 1973). However, insufficient in vivo data has prevented the assessment of AOH health risks for different species, including humans (EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain et al., 2019). Among the first in vivo data, it is reported that toxins from Alternaria cultures are lethal when injected intraperitoneally at a dose of 100 mg/kg per day in DBA/2 mice (Pero et al., 1973). AOH is one of the 70 mycotoxins present in the Alternaria culture and produces itself, a median lethal dose of 400 mg/kg of body weight when administered in isolation in DBA/2 mice (Woody and Chu, 1992).

Another in vivo study aimed to study the genotoxic potential of AOH administered by oral gavage in NMRI mice (Schuchardt et al., 2014). The oral AOH did not cause an effect on the general health status during 7 days of observation, at doses up to 2000 mg/kg. Of note, the lack of toxicity could be related to the low systemic absorption of AOH, which reached blood levels of 0.5 µM representing less than 0.06% of the administered dose. At this low systemic concentration, AOH was negative for bone marrow micronuclei test and alkaline comet assay in the liver but the assays to investigate local genotoxicity in gastrointestinal tissues failed due to adverse effects of the AOH vehicle (corn oil) (Schuchardt et al., 2014).

A recent study investigated the effect of AOH in early-stage embryonic development through the injection of pregnant mice with AOH for 4 days. The highest dose of 5 mg/kg body weight/day caused injurious effects on embryonic development from the zygote to the blastocyst stage and also embryo degradation. Additionally, AOH also provoked a redox to unbalance in the offspring of mice during early gestation, suggesting that the toxin could act through an epigenetic mechanism (Huang et al., 2021). The reproductive and developmental toxicity of AOH could be related to its ability to act as an estrogen agonist. In this regard, AOH is a diphenolic compound that has some structural similarities to estrogen molecules and acts as a weak estrogen agonist as revealed by reporter assays in H295R cells (Frizzell et al., 2013). However, in other estrogen-responsive cells, like porcine granuloma cells, AOH failed to activate estrogen receptor a (Tiemann et al., 2009). In contrast to the effect on embryonic development in mammals, the injection of AOH into the yolk sac did not cause mortality or teratogenic effect in chicken embryos at doses up to 1 mg per egg (Griffin and Chu, 1983).

There is broader evidence regarding AOH toxicity in vitro models, including studies performed in bacterial strains and mammalian cell lines that show genotoxic activity (Solhaug et al., 2016). In Salmonella strains, AOH induces direct-acting AT base pair mutagenicity (Schrader et al., 2006). Also, its capacity to induce frameshift mutations was probed in Bacillus subtilis and Escherichia coli ND160 (EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain et al., 2019). In mammalian cell lines, it has been reported that 1-h exposure to AOH in the range of 5–10 µM causes DNA strand breaks in V79 fibroblasts from Chinese hamsters, HepG2 hepatoma cells and HT-29 colon cells (Pfeiffer et al., 2007). Along with the mutagenic effect, AOH is also responsible for chromosome aberrations that are evident after 48 h of 10 µM exposure to the mycotoxin. Particularly, AOH induces kinetochore-negative micronuclei in Ishikawa and V79 cells, unscheduled DNA synthesis in the primary culture of human amniotic cells and increased mutations at the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase 1 (HPRT) gene in V79 fibroblasts (Lehmann et al., 2006). Another line of evidence suggests that DNA damage at molecular and chromosome levels is mediated by ROS production induced by AOH (Solhaug et al., 2016). This proposed mechanism is based on cytotoxicity assays of AOH, performed in cell lines including HT29, V79, RAW264.7 and Caco2 (Solhaug et al., 2012; Tiessen et al., 2013; Fernández-Blanco et al., 2014). For example, when Caco2 cells are exposed to AOH in a range of 15–60 µM for 24 h, there is a significant increase in ROS species, lipid peroxidation and a decrease in catalase and superoxide dismutase activities. Despite its oxidative effect, AOH produced a minor reduction in cell viability on Caco2, even at doses of 100 µM for 72 h (Fernández-Blanco et al., 2014).

Tiessen et al. (2013) also reported that AOH and AME induce an oxidative response in HT29 cells, including a transient decrease in glutathione levels, with a short exposure of 1 h. However, this effect did not produce DNA damage probably due to the activation of the redox-sensitive transcriptional response elicited by the transcription of Nrf2 (Tiessen et al., 2013). Another proposed mechanism for AOH genotoxicity is related to the inhibition of DNA topoisomerase I and IIa (Fehr et al., 2009). This enzyme is important to resolve topological constraints during DNA replication and therefore, it is likely that AOH-induced inhibition of topoisomerases could be responsible for the clastogenic effects observed in cell lines.

6 Limitations

Therapeutic limitations derive from insufficient knowledge of the pharmacokinetics, solubility, bioavailability, metabolism of alternariol, insufficient understanding of the molecular targets of action at the tumour cellular level, and their regulatory pathways. Although only experimental in vitro pharmacological studies have demonstrated and justified the anticancer effects of alternariol, translational pharmacological studies establishing the effective anticancer dose in humans, as well as clinical studies in humans, are lacking. Also, the development of new nanoformulations of alternariol in which it can be incorporated into different nanocarriers at the target should be the focus of future research. As a result, alternariol cannot be used in anticancer therapy as a first-line treatment, but only as an adjuvant in combination with standard chemotherapeutic treatment.

7 Concluding remarks

AOH and its derivatives, such as AME, alternariol-9-methyl ether-3-O-sulphate, alternariol 3,9-dimethyl ether and altertoxin II, exhibit an anticarcinogenic effect through several pathways, with ROS generation leading to the induction of oxidative stress and a cytotoxic effect linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory pathway, cell cycle arrest in G0/G1, G2/M and S phases, apoptotic cell death, genotoxic and mutagenic mechanisms, antiproliferative, autophagy, as well as estrogenic and clastogenic mechanisms. To our knowledge, no other studies have explored the anticarcinogenic effect of AOH or its metabolites in animal models or clinical trials. This was corroborated by a search of the literature and also of US and European databases for completed or ongoing clinical trials (www.clinicaltrail.gov, www.clinicaltrailregister.eu). Given these promising results of experimental pharmacological studies, AOH and its derivatives can be considered potential adjunctive chemotherapeutic agents.

Statements

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

MM wants to thank ANID CENTROS BASALES ACE210012.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- AIF

apoptosis-inducing factor

- ALP

alkaline phosphatase

- AME

alternariol monomethyl ether

- AOH

alternariol

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- Chk-1/2

checkpoint kinase

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- CREB

cAMP response element-binding

- CYP

Cytochrome c

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- DWm

mitochondrial transmembrane potential

- EBSS

Earle’s balanced salt solution

- EndoG

endonuclease G

- GSH

glutathione

- GST

glutathione transferase

- HPRT

hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyl transferase

- IFN

interferon

- IL

interleukin

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LPO

lipid peroxidation

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells

- NQO

4-nitroquinoline-N-oxide

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PTP

mitochondrial permeability transition pore

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

References

1

Aichinger G. Del Favero G. Warth B. Marko D. (2021). Alternaria toxins—still emerging?Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf.20, 4390–4406. 10.1111/1541-4337.12803

2

Aichinger G. (2021). Natural dibenzo-α-pyrones: Friends or foes?Int. J. Mol. Sci.22, 13063. 10.3390/ijms222313063

3

Ali E. S. Akter S. Ramproshad S. Mondal B. Riaz T. A. Islam M. T. et al (2022a). Targeting ras-ERK cascade by bioactive natural products for potential treatment of cancer: An updated overview. Cancer Cell Int.22, 246. 10.1186/s12935-022-02666-z

4

Ali E. S. Mitra K. Akter S. Ramproshad S. Mondal B. Khan I. N. et al (2022b). Recent advances and limitations of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of cancer. Cancer Cell Int.22, 284. 10.1186/s12935-022-02706-8

5

Amin R. Thalluri C. Docea A. O. Sharifi-Rad J. Calina D. (2022). Therapeutic potential of cranberry for kidney health and diseases. eFood3, e33. 10.1002/efd2.33

6

Appel B. N. Gottmann J. Schäfer J. Bunzel M. (2021). Absorption and metabolism of modified mycotoxins of alternariol, alternariol monomethyl ether, and zearalenone in Caco-2 cells. Cereal Chem.98, 109–122. 10.1002/cche.10360

7

Asgharian P. Tazekand A. P. Hosseini K. Forouhandeh H. Ghasemnejad T. Ranjbar M. et al (2022). Potential mechanisms of quercetin in cancer prevention: Focus on cellular and molecular targets. Cancer Cell Int.22, 257. 10.1186/s12935-022-02677-w

8

Bansal M. Singh N. Alam S. Pal S. Satyanarayana G. N. V. Singh D. et al (2019). Alternariol induced proliferation in primary mouse keratinocytes and inflammation in mouse skin is regulated via PGE(2)/EP2/cAMP/p-CREB signaling pathway. Toxicology412, 79–88. 10.1016/j.tox.2018.11.013

9

Bensassi F. Gallerne C. El Dein O. S. Hajlaoui M. R. Bacha H. Lemaire C. (2011). Mechanism of Alternariol monomethyl ether-induced mitochondrial apoptosis in human colon carcinoma cells. Toxicology290, 230–240. 10.1016/j.tox.2011.09.087

10

Bensassi F. Gallerne C. Sharaf El Dein O. Hajlaoui M. R. Bacha H. Lemaire C. (2012). Cell death induced by the Alternaria mycotoxin Alternariol. Toxicol Vitro26, 915–923. 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.04.014

11

Brugger E. M. Wagner J. Schumacher D. M. Koch K. Podlech J. Metzler M. et al (2006). Mutagenicity of the mycotoxin alternariol in cultured mammalian cells. Toxicol. Lett.164, 221–230. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2006.01.001

12

Buga A. M. Docea A. O. Albu C. Malin R. D. Branisteanu D. E. Ianosi G. et al (2019). Molecular and cellular stratagem of brain metastases associated with melanoma. Oncol. Lett.17, 4170–4175. 10.3892/ol.2019.9933

13

Burkhardt B. Pfeiffer E. Metzler M. (2009). Absorption and metabolism of the mycotoxins alternariol and alternariol-9-methyl ether in Caco-2 cells in vitro. Mycotoxin Res.25, 149–157. 10.1007/s12550-009-0022-2

14

Capó X. Martorell M. Tur J. A. Sureda A. Pons A. (2021). 5-Dodecanolide, a compound isolated from pig lard, presents powerful anti-inflammatory properties. Molecules26, 7363. 10.3390/molecules26237363

15

Chaudhary P. Mitra D. Das Mohapatra P. K. Oana Docea A. Mon Myo E. Janmeda P. et al (2023). Camellia sinensis: Insights on its molecular mechanisms of action towards nutraceutical, anticancer potential and other therapeutic applications. Arabian J. Chem.16, 104680. 10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104680

16

Chiesi C. Fernandez-Blanco C. Cossignani L. Font G. Ruiz M. J. (2015). Alternariol-induced cytotoxicity in Caco-2 cells. Protective effect of the phenolic fraction from virgin olive oil. Toxicon93, 103–111. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.11.230

17

Da Cruz Cabral L. Delgado J. Patriarca A. Rodríguez A. (2019). Differential response to synthetic and natural antifungals by Alternaria tenuissima in wheat simulating media: Growth, mycotoxin production and expression of a gene related to cell wall integrity. Int. J. Food Microbiol.292, 48–55. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.12.005

18

Degen G. H. (2017). Mycotoxins in food: Occurrence, importance and health risk. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforsch. Gesundheitsschutz60, 745–756. 10.1007/s00103-017-2560-7

19

Del Favero G. Mayer R. M. Dellafiora L. Janker L. Niederstaetter L. Dall'Asta C. et al (2020)., 9. Cells, 847. 10.3390/cells9040847 Structural similarity with cholesterol reveals crucial insights into mechanisms sustaining the immunomodulatory activity of the mycotoxin alternariolCells.

20

Dellafiora L. Dall'Asta C. Cruciani G. Galaverna G. Cozzini P. (2015). Molecular modelling approach to evaluate poisoning of topoisomerase I by alternariol derivatives. Food Chem.189, 93–101. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.083

21

Dhyani P. Quispe C. Sharma E. Bahukhandi A. Sati P. Attri D. C. et al (2022a). Anticancer potential of alkaloids: A key emphasis to colchicine, vinblastine, vincristine, vindesine, vinorelbine and vincamine. Cancer Cell Int.22, 206. 10.1186/s12935-022-02624-9

22

Dhyani P. Sati P. Sharma E. Attri D. C. Bahukhandi A. Tynybekov B. et al (2022b). Sesquiterpenoid lactones as potential anti-cancer agents: An update on molecular mechanisms and recent studies. Cancer Cell Int.22, 305. 10.1186/s12935-022-02721-9

23

Docea A. O. Mitrut P. Grigore D. Pirici D. Calina D. C. Gofita E. (2012). Immunohistochemical expression of TGF beta (TGF-beta), TGF beta receptor 1 (TGFBR1), and Ki67 in intestinal variant of gastric adenocarcinomas. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol.53, 683–692.

24

Docea A. O. Calina D. Goumenou M. Neagu M. Gofita E. Tsatsakis A. (2016). Study design for the determination of toxicity from long-term-low-dose exposure to complex mixtures of pesticides, food additives and lifestyle products. Toxicol. Lett.258, S179. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2016.06.1666

25

EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain Schrenk D. Bodin L. Chipman J. K. Del Mazo J. Grasl-Kraupp B. Hogstrand C. et al (2019). Scientific opinion on the risks for animal and human health related to the presence of quinolizidine alkaloids in feed and food, in particular in lupins and lupin-derived products. EFSA J.17, e05860. 10.2903/j.efsa.2019.5860

26

El Khoury D. Fayjaloun S. Nassar M. Sahakian J. Aad P. Y. (2019). Updates on the effect of mycotoxins on male reproductive efficiency in mammals. Toxins (Basel)11, 515. 10.3390/toxins11090515

27

Estiarte N. Crespo-Sempere A. Marín S. Ramos A. J. Worobo R. W. (2018). Stability of alternariol and alternariol monomethyl ether during food processing of tomato products. Food Chem.245, 951–957. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.11.078

28

Fehr M. Pahlke G. Fritz J. Christensen M. O. Boege F. Altemöller M. et al (2009). Alternariol acts as a topoisomerase poison, preferentially affecting the IIalpha isoform. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.53, 441–451. 10.1002/mnfr.200700379

29

Fernández-Blanco C. Font G. Ruiz M. J. (2014). Oxidative stress of alternariol in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Lett.229, 458–464. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.07.024

30

Fernández-Blanco C. Font G. Ruiz M. J. (2015). Oxidative DNA damage and disturbance of antioxidant capacity by alternariol in Caco-2 cells. Toxicol. Lett.235, 61–66. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.03.013

31

Fernández-Blanco C. Font G. Ruiz M. J. (2016). Role of quercetin on Caco-2 cells against cytotoxic effects of alternariol and alternariol monomethyl ether. Food Chem. Toxicol.89, 60–66. 10.1016/j.fct.2016.01.011

32

Fleck S. C. Burkhardt B. Pfeiffer E. Metzler M. (2012). Alternaria toxins: Altertoxin II is a much stronger mutagen and DNA strand breaking mycotoxin than alternariol and its methyl ether in cultured mammalian cells. Toxicol. Lett.214, 27–32. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.08.003

33

Fleck S. C. Sauter F. Pfeiffer E. Metzler M. Hartwig A. Köberle B. (2016). DNA damage and repair kinetics of the Alternaria mycotoxins alternariol, altertoxin II and stemphyltoxin III in cultured cells. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen798-799, 27–34. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2016.02.001

34

Frizzell C. Ndossi D. Kalayou S. Eriksen G. S. Verhaegen S. Sørlie M. et al (2013). An in vitro investigation of endocrine disrupting effects of the mycotoxin alternariol. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.271, 64–71. 10.1016/j.taap.2013.05.002

35

Garzoli S. Alarcón-Zapata P. Seitimova G. Alarcón-Zapata B. Martorell M. Sharopov F. et al (2022). Natural essential oils as a new therapeutic tool in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int.22, 407. 10.1186/s12935-022-02806-5

36

GBD 2019 Colorectal Cancer Collaborators (2022). Global, regional, and national burden of colorectal cancer and its risk factors, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol., 7, 627–647. Accessed on 5.08.2022. 10.1016/S2468-1253(22)00044-9

37

Griffin G. F. Chu F. S. (1983). Toxicity of the Alternaria metabolites alternariol, alternariol methyl ether, altenuene, and tenuazonic acid in the chicken embryo assay. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.46, 1420–1422. 10.1128/aem.46.6.1420-1422.1983

38

Grover S. Lawrence C. B. (2017). The Alternaria alternata mycotoxin alternariol suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci.18, 1577. 10.3390/ijms18071577

39

Hawas U. W. El-Desouky S. Abou El-Kassem L. Elkhateeb W. (2015). Alternariol derivatives from Alternaria alternata, an endophytic fungus residing in red sea soft coral, inhibit HCV NS3/4A protease. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol.51, 579–584. 10.1134/s0003683815050099

40

Hossain R. Quispe C. Herrera-Bravo J. Islam M. S. Sarkar C. Islam M. T. et al (2021). Lasia spinosa chemical composition and therapeutic potential: A literature-based review. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev.2021, 1602437. 10.1155/2021/1602437

41

Hossain R. Ray P. Sarkar C. Islam M. S. Khan R. A. Khalipha A. B. R. et al (2022). Natural compounds or their derivatives against breast cancer: A computational study. BioMed Res. Int.2022, 5886269. 10.1155/2022/5886269

42

Huang C. H. Wang F. T. Chan W. H. (2021). Alternariol exerts embryotoxic and immunotoxic effects on mouse blastocysts through ROS-mediated apoptotic processes. Toxicol. Res. (Camb)10, 719–732. 10.1093/toxres/tfab054

43

Ianoși S. L. Batani A. Ilie M. A. Tampa M. Georgescu S. R. Zurac S. et al (2019). Non-invasive imaging techniques for the in vivo diagnosis of Bowen's disease: Three case reports. Oncol. Lett.17, 4094–4101. 10.3892/ol.2019.10079

44

Iqbal M. J. Javed Z. Herrera-Bravo J. Sadia H. Anum F. Raza S. et al (2022). Biosensing chips for cancer diagnosis and treatment: A new wave towards clinical innovation. Cancer Cell Int.22, 354. 10.1186/s12935-022-02777-7

45

Irfan M. Javed Z. Khan K. Khan N. Docea A. O. Calina D. et al (2022). Apoptosis evasion via long non-coding RNAs in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int.22, 280. 10.1186/s12935-022-02695-8

46

Islam M. T. Mishra S. K. Tripathi S. De Alencar M. Jmc E. S. Rolim H. M. L. et al (2018). Mycotoxin-assisted mitochondrial dysfunction and cytotoxicity: Unexploited tools against proliferative disorders. IUBMB Life70, 1084–1092. 10.1002/iub.1932

47

Islam M. T. Quispe C. El-Kersh D. M. Shill M. C. Bhardwaj K. Bhardwaj P. et al (2021). A literature-based update on Benincasa hispida (thunb.) cogn.: Traditional uses, nutraceutical, and phytopharmacological profiles. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev.2021, 6349041. 10.1155/2021/6349041

48

Islam M. T. (2017). Mycotoxins, in a prospection in the causes and treatment of metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Complementary Altern. Med.8, 00281. 10.15406/ijcam.2017.08.00281

49

Jain D. Chaudhary P. Varshney N. Bin Razzak K. S. Verma D. Khan Zahra T. R. et al (2021). Tobacco smoking and liver cancer risk: Potential avenues for carcinogenesis. J. Oncol.2021, 5905357. 10.1155/2021/5905357

50

Javed Z. Khan K. Herrera-Bravo J. Naeem S. Iqbal M. J. Raza Q. et al (2022). Myricetin: Targeting signaling networks in cancer and its implication in chemotherapy. Cancer Cell Int.22, 239. 10.1186/s12935-022-02663-2

51

Khandia R. Dadar M. Munjal A. Dhama K. Karthik K. Tiwari R. et al (2019). A comprehensive review of autophagy and its various roles in infectious, non-infectious, and lifestyle diseases: Current knowledge and prospects for disease prevention, novel drug design, and therapy. Cells8, 674. 10.3390/cells8070674

52

Kitic D. Miladinovic B. Randjelovic M. Szopa A. Sharifi-Rad J. Calina D. et al (2022). Anticancer potential and other pharmacological properties of Prunus armeniaca L.: An updated overview. Plants11, 1885. 10.3390/plants11141885

53

Kollarova J. Cenk E. Schmutz C. Marko D. (2018). The mycotoxin alternariol suppresses lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in THP-1 derived macrophages targeting the NF-κB signalling pathway. Arch. Toxicol.92, 3347–3358. 10.1007/s00204-018-2299-4

54

Lehmann L. Wagner J. Metzler M. (2006). Estrogenic and clastogenic potential of the mycotoxin alternariol in cultured mammalian cells. Food Chem. Toxicol.44, 398–408. 10.1016/j.fct.2005.08.013

55

Lemke A. Burkhardt B. Bunzel D. Pfeiffer E. Metzler M. Huch M. et al (2016). Alternaria toxins of the alternariol type are not metabolised by human faecal microbiota. World Mycotoxin J.9, 41–50. 10.3920/wmj2014.1875

56

Li X. Shen J. Jiang Y. Shen T. You L. Sun X. et al (2016). Anti-inflammatory effects of chloranthalactone B in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17, 1938. 10.3390/ijms17111938

57

Li K. Hu W. Yang Y. Wen H. Li W. Wang B. (2023). Anti-inflammation of hydrogenated isoflavones in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells via inhibition of NF-κB and MAPK signaling pathways. Mol. Immunol.153, 126–134. 10.1016/j.molimm.2022.11.019

58

Limas J. C. Cook J. G. (2019). Preparation for DNA replication: The key to a successful S phase. FEBS Lett.593, 2853–2867. 10.1002/1873-3468.13619

59

Meena M. Samal S. (2019). Alternaria host-specific (HSTs) toxins: An overview of chemical characterization, target sites, regulation and their toxic effects. Toxicol. Rep.6, 745–758. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2019.06.021

60

Mitrut P. Docea A. O. Kamal A. M. Mitrut R. Calina D. Gofita E. et al (2016). Colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Colon Rectal Surg.31, 168–178. 10.1055/s-0037-1602237

61

Motyka S. Jafernik K. Ekiert H. Sharifi-Rad J. Calina D. Al-Omari B. et al (2023). Podophyllotoxin and its derivatives: Potential anticancer agents of natural origin in cancer chemotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother.158, 114145. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.114145

62

Palanichamy P. Kannan S. Murugan D. Alagusundaram P. Marudhamuthu M. (2019). Purification, crystallization and anticancer activity evaluation of the compound alternariol methyl ether from endophytic fungi Alternaria alternata. J. Appl. Microbiol.127, 1468–1478. 10.1111/jam.14410

63

Pero R. W. Posner H. Blois M. Harvan D. Spalding J. W. (1973). Toxicity of metabolites produced by the "Alternaria". Environ. Health Perspect.4, 87–94. 10.1289/ehp.730487

64

Pezzani R. Jiménez-Garcia M. Capó X. Sönmez Gürer E. Sharopov F. Rachel T. Y. L. et al (2023). Anticancer properties of bromelain: State-of-the-art and recent trends. Front. Oncol.12, 1068778. 10.3389/fonc.2022.1068778

65

Pfeiffer E. Eschbach S. Metzler M. (2007). Alternaria toxins: DNA strand-breaking activity in mammalian cellsin vitro. Mycotoxin Res.23, 152–157. 10.1007/BF02951512

66

Pfliegler W. P. Pusztahelyi T. Pócsi I. (2015). Mycotoxins - prevention and decontamination by yeasts. J. Basic Microbiol.55, 805–818. 10.1002/jobm.201400833

67

Prasher P. Sharma M. Sharma A. K. Sharifi-Rad J. Calina D. Hano C. et al (2023). Key oncologic pathways inhibited by erinacine A: A perspective for its development as an anticancer molecule. Biomed. Pharmacother.160, 114332. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114332

68

Salehi B. Shetty M. S. Kumar N. V. A. Zivkovic J. Calina D. Docea A. O. et al (2019). Veronica plants-drifting from farm to traditional healing, food application, and phytopharmacology. Molecules24, 2454. 10.3390/molecules24132454

69

Salehi B. Quispe C. Chamkhi I. El Omari N. Balahbib A. Sharifi-Rad J. et al (2021). Pharmacological properties of chalcones: A review of preclinical including molecular mechanisms and clinical evidence. Front. Pharmacol.11, 592654. 10.3389/fphar.2020.592654

70

Sani T. A. Mohammadpour E. Mohammadi A. Memariani T. Yazdi M. V. Rezaee R. et al (2017). Cytotoxic and apoptogenic properties of Dracocephalum kotschyi aerial part different fractions on CALU-6 and MEHR-80 lung cancer cell lines. Farmacia65, 189–199.

71

Scheau C. Caruntu C. Badarau I. A. Scheau A. E. Docea A. O. Calina D. et al (2021). Cannabinoids and inflammations of the gut-lung-skin barrier. J. Pers. Med.11, 494. 10.3390/jpm11060494

72

Schmutz C. Cenk E. Marko D. (2019). The Alternaria mycotoxin alternariol triggers the immune response of IL-1β-stimulated, differentiated caco-2 cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.63, 1900341. 10.1002/mnfr.201900341

73

Schrader T. J. Cherry W. Soper K. Langlois I. (2006). Further examination of the effects of nitrosylation on Alternaria alternata mycotoxin mutagenicity in vitro. Mutat. Res.606, 61–71. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2006.02.008

74

Schreck I. Deigendesch U. Burkhardt B. Marko D. Weiss C. (2012). The Alternaria mycotoxins alternariol and alternariol methyl ether induce cytochrome P450 1A1 and apoptosis in murine hepatoma cells dependent on the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Arch. Toxicol.86, 625–632. 10.1007/s00204-011-0781-3

75

Schuchardt S. Ziemann C. Hansen T. (2014). Combined toxicokinetic and in vivo genotoxicity study on Alternaria toxins. EFSA Support. Publ.11. 10.2903/sp.efsa.2014.en-679

76

Sharifi-Rad J. Rodrigues C. F. Sharopov F. Docea A. O. Karaca A. C. Sharifi-Rad M. et al (2020). Diet, lifestyle and cardiovascular diseases: Linking pathophysiology to cardioprotective effects of natural bioactive compounds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health17, 2326. 10.3390/ijerph17072326

77

Sharifi-Rad J. Bahukhandi A. Dhyani P. Sati P. Capanoglu E. Docea A. O. et al (2021a). Therapeutic potential of neoechinulins and their derivatives: An overview of the molecular mechanisms behind pharmacological activities. Front. Nutr.8, 664197. 10.3389/fnut.2021.664197

78

Sharifi-Rad J. Quispe C. Butnariu M. Rotariu L. S. Sytar O. Sestito S. et al (2021b). Chitosan nanoparticles as a promising tool in nanomedicine with particular emphasis on oncological treatment. Cancer Cell Int.21, 318. 10.1186/s12935-021-02025-4

79

Sharifi-Rad J. Quispe C. Herrera-Bravo J. Akram M. Abbaass W. Semwal P. et al (2021c). Phytochemical constituents, biological activities, and health-promoting effects of the Melissa officinalis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2021, 6584693.

80

Sharifi-Rad J. Quispe C. Imran M. Rauf A. Nadeem M. Gondal T. A. et al (2021d). Genistein: An integrative overview of its mode of action, pharmacological properties, and health benefits. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2021, 3268136. 10.1155/2021/3268136

81

Sharifi-Rad J. Quispe C. Patra J. K. Singh Y. D. Panda M. K. Das G. et al (2021e). Paclitaxel: Application in modern oncology and nanomedicine-based cancer therapy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2021, 3687700. 10.1155/2021/3687700

82

Sharifi-Rad J. Herrera-Bravo J. Kamiloglu S. Petroni K. Mishra A. P. Monserrat-Mesquida M. et al (2022a). Recent advances in the therapeutic potential of emodin for human health. Biomed. Pharmacother.154, 113555. 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113555

83

Sharifi-Rad J. Quispe C. Bouyahya A. El Menyiy N. El Omari N. Shahinozzaman M. et al (2022b). Ethnobotany, phytochemistry, biological activities, and health-promoting effects of the genus Bulbophyllum. Evid. Based Complementary Altern. Med.2022, 6727609. 10.1155/2022/6727609

84

Sharifi-Rad J. Rapposelli S. Sestito S. Herrera-Bravo J. Arancibia-Diaz A. Salazar L. A. et al (2022c). Multi-target mechanisms of phytochemicals in alzheimer's disease: Effects on oxidative stress, neuroinflammation and protein aggregation. J. Pers. Med.12, 1515. 10.3390/jpm12091515

85

Sharma E. Attri D. C. Sati P. Dhyani P. Szopa A. Sharifi-Rad J. et al (2022). Recent updates on anticancer mechanisms of polyphenols. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.10, 1005910. 10.3389/fcell.2022.1005910

86

Smith M. C. Madec S. Coton E. Hymery N. (2016). Natural Co-occurrence of mycotoxins in foods and feeds and their in vitro combined toxicological effects. Toxins (Basel)8, 94. 10.3390/toxins8040094

87

Solhaug A. Vines L. L. Ivanova L. Spilsberg B. Holme J. A. Pestka J. et al (2012). Mechanisms involved in alternariol-induced cell cycle arrest. Mutat. Res.738-739, 1–11. 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2012.09.001

88

Solhaug A. Holme J. A. Haglund K. Dendele B. Sergent O. Pestka J. et al (2013). Alternariol induces abnormal nuclear morphology and cell cycle arrest in murine RAW 264.7 macrophages. Toxicol. Lett.219, 8–17. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.02.012

89

Solhaug A. Torgersen M. L. Holme J. A. Lagadic-Gossmann D. Eriksen G. S. (2014). Autophagy and senescence, stress responses induced by the DNA-damaging mycotoxin alternariol. Toxicology326, 119–129. 10.1016/j.tox.2014.10.009

90

Solhaug A. Eriksen G. S. Holme J. A. (2016). Mechanisms of action and toxicity of the mycotoxin alternariol: A review. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol.119, 533–539. 10.1111/bcpt.12635

91

Stypuła-Trębas S. Minta M. Radko L. Jedziniak P. Posyniak A. (2017). Nonsteroidal mycotoxin alternariol is a full androgen agonist in the yeast reporter androgen bioassay. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol.55, 208–211. 10.1016/j.etap.2017.08.036

92

Taheri Y. Quispe C. Herrera-Bravo J. Sharifi-Rad J. Ezzat S. M. Merghany R. M. et al (2022). Urtica dioica-derived phytochemicals for pharmacological and therapeutic applications. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2022, 4024331. 10.1155/2022/4024331

93

Tan N. Tao Y. Pan J. Wang S. Xu F. She Z. et al (2008). Isolation, structure elucidation, and mutagenicity of four alternariol derivatives produced by the mangrove endophytic fungus No. 2240. Chem. Nat. Compd.44, 296–300. 10.1007/s10600-008-9046-7

94

Tang X. Chen Y. Zhu X. Miao Y. Wang D. Zhang J. et al (2022). Alternariol monomethyl ether toxicity and genotoxicity in male sprague-dawley rats: 28-Day in vivo multi-endpoint assessment. Mutat. Res. Genetic Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen.873, 503435. 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2021.503435

95

Tiemann U. Tomek W. Schneider F. Müller M. Pöhland R. Vanselow J. (2009). The mycotoxins alternariol and alternariol methyl ether negatively affect progesterone synthesis in porcine granulosa cells in vitro. Toxicol. Lett.186, 139–145. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.01.014

96

Tiessen C. Fehr M. Schwarz C. Baechler S. Domnanich K. Böttler U. et al (2013). Modulation of the cellular redox status by the Alternaria toxins alternariol and alternariol monomethyl ether. Toxicol. Lett.216, 23–30. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.005

97

Tran V. N. Viktorová J. Ruml T. (2020). Mycotoxins: Biotransformation and bioavailability assessment using caco-2 cell monolayer. Toxins (Basel)12, 628. 10.3390/toxins12100628

98

Vila-Donat P. Fernández-Blanco C. Sagratini G. Font G. Ruiz M. J. (2015). Effects of soyasaponin I and soyasaponins-rich extract on the alternariol-induced cytotoxicity on Caco-2 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol.77, 44–49. 10.1016/j.fct.2014.12.016

99

Wollenhaupt K. Schneider F. Tiemann U. (2008). Influence of alternariol (AOH) on regulator proteins of cap-dependent translation in porcine endometrial cells. Toxicol. Lett.182, 57–62. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.08.005

100

Woody M. A. Chu F. S. (1992). “Toxicology of Alternaria mycotoxins,” in Alternaria Biology, plant diseases and metabolites. Editors CHEŁKOWSKIJ.VISCONTIA. (Amsterdam: Elsevier).

101

Xie C. Li X. Zhu J. Wu J. Geng S. Zhong C. (2019). Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate suppresses LPS-induced inflammation and oxidative stress through inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK pathways in RAW264.7 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem.27, 516–524. 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.12.033

102

Xu D. S. Kong T. Q. Ma J. Q. (1996). The inhibitory effect of extracts from Fructus lycii and Rhizoma polygonati on in vitro DNA breakage by alternariol. Biomed. Environ. Sci.9, 67–70.

103

Zlatian O. M. Comanescu M. V. Rosu A. F. Rosu L. Cruce M. Gaman A. E. et al (2015). Histochemical and immunohistochemical evidence of tumor heterogeneity in colorectal cancer. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol.56, 175–181.

Summary

Keywords

alternariol, mycotoxin, cancer, molecular targets, cytotoxic effect, apoptosis, chemotherapy

Citation

Islam MT, Martorell M, González-Contreras C, Villagran M, Mardones L, Tynybekov B, Docea AO, Abdull Razis AF, Modu B, Calina D and Sharifi-Rad J (2023) An updated overview of anticancer effects of alternariol and its derivatives: underlying molecular mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1099380. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1099380

Received

15 November 2022

Accepted

14 March 2023

Published

23 March 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Lekshmi R. Nath, Amrita College of Pharmacy, India

Reviewed by

Vinod B. S., Sree Narayana College, Kollam, India

Minakshi Saikia, Washington University in St. Louis, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Islam, Martorell, González-Contreras, Villagran, Mardones, Tynybekov, Docea, Abdull Razis, Modu, Calina and Sharifi-Rad.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Miquel Martorell, mmartorell@udec.cl; Ahmad Faizal Abdull Razis, madfaizal@upm.edu.my; Daniela Calina, calinadaniela@gmail.com; Javad Sharifi-Rad, javad.sharifirad@gmail.com

This article was submitted to Pharmacology of Anti-Cancer Drugs, a section of the journal Frontiers in Pharmacology

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.