Abstract

Nuclear receptors are ligand-regulated transcription factors that regulate vast cellular activities and serve as an important class of drug targets. Among them, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are members of the nuclear receptor family and have been extensively studied for their roles in metabolism, differentiation, development, and cancer, among others. Recently, there has been considerable interest in understanding and defining the function of PPARs and their agonists in regulating innate and adaptive immune responses and their pharmacological potential in combating chronic inflammatory diseases. In this review, we focus on emerging evidence for the potential role of PPARγ in macrophage biology, which is the prior innate immune executive in metabolic and tissue homeostasis. We also discuss the role of PPARγ as a regulator of macrophage function in inflammatory diseases. Lastly, we discuss the possible application of PPARγ antagonists in metabolic pathologies.

1 Introduction

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are transcription factors that rely on ligands for their activation. They belong to the nuclear receptor superfamily and share a conserved structure. In mammals, there are three types of PPARs: PPARα, PPARδ (sometimes referred to as PPARβ), and PPARγ, also known as NR1C1, NR1C2, and NR1C3, respectively (Kliewer et al., 1994; Chawla et al., 2001b). Each type is encoded by a separate gene located on a different chromosome. PPARs are expressed in various tissues and cell types, influencing several cellular functions such as proliferation, differentiation, glucose and lipid metabolism, insulin signaling, inflammation, and tumorigenesis, among others (Chawla et al., 1994; Giusti et al., 2003; Odegaard et al., 2007; Harmon et al., 2011). PPARγ is the most extensively studied among the PPAR types. It comprises of four main domains: a ligand-dependent transcriptional activation domain (A/B domain) at the N-terminus, a DNA-binding domain (C domain), a hinge region (D domain), and a ligand-binding domain (E/F domain) at the C-terminus (Escher and Wahli, 2000). PPARγ is highly conserved in humans and mice, sharing 96% homology in amino acid sequences. The open reading frame (ORF) of the PPARγ gene in both species consists of six exons. Exons 2 and 3 encode the DNA-binding domain, while exons 5 and 6 encode the ligand-binding domain (Chen et al., 2006). PPARγ has two isoforms, γ1 and γ2, generated from alternate promoter usage and differential splicing with different cell expression pattern (Zhu et al., 1995). For example, PPARγ1 is the dominant form in macrophages and actually broadly expressed; in contrast, PPARγ2 is mostly restricted in adipocytes, regulating almost every aspect of adipocyte biology (Berger and Moller, 2002). Given their different expression pattern and function, PPARγ1 and PPARγ2 should be more carefully distinguished.

The significance of PPARγ in immune cells, particularly macrophages, has been well established (Chawla, 2010). Macrophages are specialized cells derived from bone marrow, playing crucial roles in tissue homeostasis and the innate immune response. Macrophage activation is essential for the innate immune response and serves as the initial defense against disruptions in tissue homeostasis. Dysregulation of macrophage activities is closely linked to the development of chronic diseases such as obesity, atherosclerosis, aging, fibrosis, and cancer. Macrophages within different organs possess specific functions dictated by tissue heterogeneity (Wculek et al., 2022).

PPARγ has been demonstrated to regulate the key activities in macrophages, including differentiation, inflammatory activation, polarization, and lipid metabolism. This review is focused on the recent progress of PPARγ function in macrophages and the connection with immunometabolism. In addition, we highlight some understudied directions in metabolism and cellular communication.

2 Transcriptional mechanisms of PPARγ

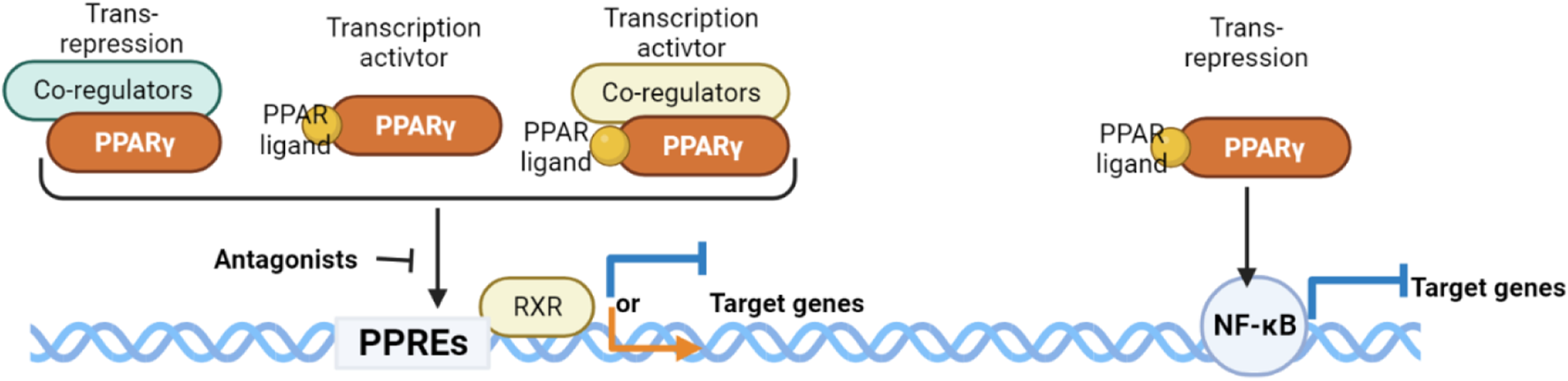

PPARγ exerts its regulatory influence on multiple metabolic and inflammatory signaling pathways by controlling the transcriptional activity of target genes. This regulation occurs through direct binding to PPAR response elements (PPREs) located on the promoters of specific genes, either in a ligand-dependent or ligand-independent manner (Figure 1). This binding event modifies the structure of chromatin and facilitates the recruitment of various cofactors, including coactivators and corepressors, which ultimately govern gene expression (Glass and Ogawa, 2006). PPARγ primarily forms a heterodimeric complex with the retinoid X receptor (RXR) to enhance transcriptional activity (Li et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2002) positively regulates the expression of target genes or to exert transrepressive effects (Kamei et al., 1996) negatively regulates gene expression, effectively repressing the activity of certain genes. These versatile functions of PPARγ allow it to regulate an extensive network of genes involved in lipid metabolism and glucose homeostasis across diverse tissues such as adipose tissue, muscle, liver, and others. While the exact nature of endogenous ligands for PPARγ in vivo is still not well characterized, they are believed to be derivatives of fatty acids that are produced locally through paracrine or autocrine mechanisms (Kliewer et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2019b). Notably, various fatty acid metabolites generated during the inflammatory response can activate PPARs, and macrophages play a significant role in the production of endogenous ligands for PPARγ (Glass and Saijo, 2010).

FIGURE 1

Mechanisms of action exerted by the PPARγ/RXRα heterodimer.

3 Macrophage activation

Macrophages are crucial innate immune cells with a phagocytic function that involves clearing microorganisms, apoptotic and necrotic cells, and contributing to tissue remodeling (Gordon et al., 2014). The functional diversity of macrophages is primarily manifested through their distinct roles governed by signaling factors, metabolic changes (Glass and Natoli, 2016) and crosstalk (Sárvári et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2023). Historically, activation studies have predominantly focused on primary macrophages and macrophage cell lines, which were exposed to single polarizing ligands such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), interferon gamma (IFNγ), or interleukin 4 (IL-4) in vitro (Glass and Natoli, 2016). These ligands trigger signaling cascades upon engaging cell surface receptors. For instance, in response to invading pathogens and Th1 cytokines like IFNγ, macrophages assume a proinflammatory immune response (known as the proinflammatory/classical activation state, M1), which involves pathogen phagocytosis (Gordon, 2003; Gosselin et al., 2014). Conversely, in the presence of Th2 cytokines like IL-4 and IL-13, macrophages adopt an anti-inflammatory immune tolerance state (termed the anti-inflammatory/alternative activation state, M2) to facilitate tissue repair processes (Gordon, 2003; Gosselin et al., 2014; Toobian et al., 2021). Apart from cell surface receptor activation, macrophage phenotypes are significantly influenced by intracellular and extracellular signals that are regulated by members of the nuclear receptor superfamily. Notably, PPARγ, glucocorticoid receptor, and liver X receptor (LXR) act as counter-regulators, inhibiting the transcriptional activity of proinflammatory transcription factors, including NF-κB, through direct and indirect mechanisms (Glass and Saijo, 2010; Li et al., 2013; Ito et al., 2015). These intricate regulatory networks determine macrophage distinct activity states and impose their tissue-specific properties.

Macrophages in different activation states exhibit corresponding gene expression profiles. The proinflammatory state is characterized by the presence of immunoreactive cytokine markers such as NOS2, TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, and MCP1. In contrast, macrophages in an immune tolerance state express anti-inflammatory markers including CD36, IL-13, Arg1, Ym1, Fizz1, CD206, IL-4, and IL-10. The expression of these markers is tightly coordinated. For instance, treatment with LPS induces the typical proinflammatory activation of mouse macrophages, upregulating Th1 cytokines such as TNF-α, IL1-β, IL-6, and IL-12 while downregulating Th2 cytokine IL-10 (Shapouri-Moghaddam et al., 2018). Macrophages possess heterogeneity to maintain a balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory immune states to function appropriately. Impaired switching between these two states is implicated in tissue damage and the development of chronic diseases.

4 The connection between macrophage and PPARγ

Activated macrophages are multifaceted immune cells that play crucial roles in both innate and adaptive immunity. They can present processed antigens to T cells, while activated T cells, in turn, secrete cytokines that further activate macrophages (Guerriero, 2019). Growing evidence suggests that PPARγ also plays a significant role in the immune system. In addition to its role as a master regulator of adipocyte differentiation, PPARγ is induced during the differentiation of monocytes into macrophages. It is expressed on various immune cells, including monocytes/macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), T and B lymphocytes, and platelets (Padilla et al., 2000; Gosset et al., 2001; Setoguchi et al., 2001; Alleva et al., 2002; Rotondo and Davidson, 2002). However, PPARγ-deficient embryonic stem cells have been shown to differentiate into macrophages (Chawla et al., 2001b). PPARγ also influences the differentiation of fetal monocytes into alveolar macrophages (Ginhoux, 2014).

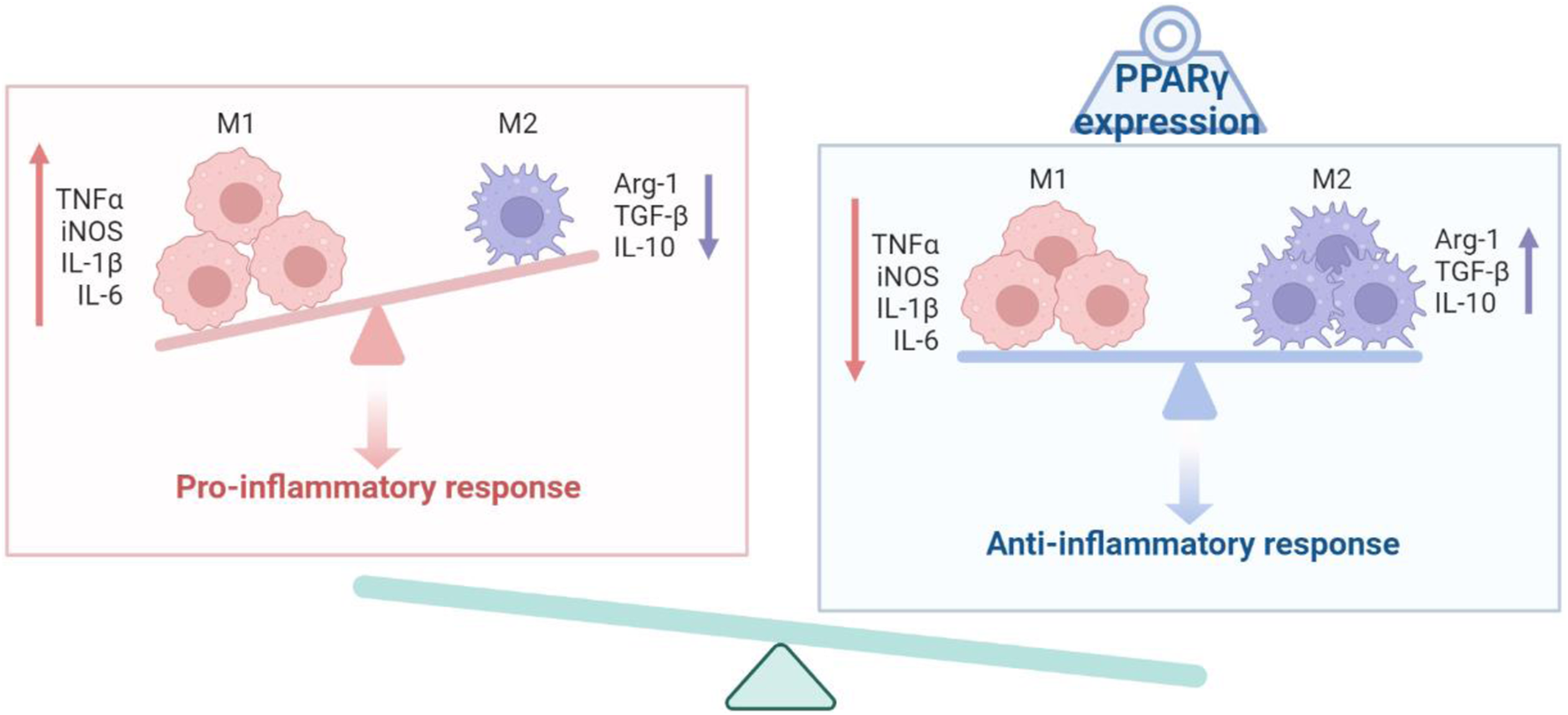

PPARγ activation has been reported to suppress the immune response of macrophages (Figure 2). In the absence of PPARγ, mouse macrophages exhibited upregulation of proinflammatory levels and downregulation of anti-inflammatory cytokines when induced with LPS (Heming et al., 2018). Additionally, PPARγ inhibits the expression of HIF1a, a crucial regulator of immune responsiveness, thereby increasing the expression of arginase 1, an anti-inflammatory marker (Blum et al., 2016). PPARγ exerts its effects on immune cells by directly activating the transcription of target genes through DNA binding. Moreover, IL-4/STAT6 signaling and IL-13 induce PPARγ expression, with STAT6 or PSTPIP2 acting as a “facilitator” of PPARγ signaling, resulting in the promotion of anti-inflammatory responses (Huang et al., 1999; Xu and Lv, 2023). Notably, specific anti-inflammatory genes, such as Arg1 and Mgl1, are identified as direct PPARγ target genes (Gallardo-Soler et al., 2008). These findings indicate that PPARγ not only influences the immune state of macrophages but also plays a role in regulating the overall metabolic states (Bouhlel et al., 2007; Odegaard et al., 2007). In vivo studies have also shown the response of PPARγ to infection. Macrophages are involved in post-infection repair and the clearance of immune antigenic fragments. Activation of PPARγ increased Fcg receptor-mediated phagocytosis in murine alveolar macrophages, indicating its role in regulating phagocytic clearance (Aronoff et al., 2007). PPARγ-deficient mice have consistently shown impaired skin wound healing due to defective clearance of apoptotic cells (Chen et al., 2015). PPARγ has also been implicated in proper tissue repair after influenza infection, as PPARγ-deficient mice exhibited increased collagen deposition in the lungs (Huang et al., 2019a). Furthermore, PPARγ has demonstrated its ability to promote the macrophage phenotype of immune tolerance.

FIGURE 2

Schematic diagram of the PPARγ and the activation state of macrophages.

Apart from its direct effects on insulin sensitization and adipocyte development, PPARγ plays a role in macrophages present in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle, and liver. PPARγ, functioning as a metabolic sensor and transcriptional regulator, governs the expression of GDF3, a member of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) family. GDF3, in turn, plays a crucial role in restoring skeletal muscle integrity by promoting the fusion of muscle progenitor cells, thereby mediating the regenerative effects of specialized macrophage-derived factors in tissue repair (Hevener et al., 2007; Varga et al., 2016). Macrophages also infiltrate adipose tissue, facilitating the mobilization of macrophages from the bone marrow into adipose tissue (mediated through MCP1) and efficiently clearing impaired adipocytes (Kanda et al., 2006). Additionally, macrophage migration is induced by localized microhypoxic regions in adipose tissue (Hif1a) (Lolmède et al., 2003; Trayhurn and Wood, 2004; Hosogai et al., 2007), contributing to hepatic fatty acid shunting processes during fasting conditions (Nguyen et al., 2005; Suganami et al., 2005; Shi et al., 2006). Post-infiltration, macrophages display significant heterogeneity in their activity and function, reflecting changes in metabolic and immune disturbances (Gordon and Taylor, 2005). Central in the pathogenesis of chronic liver injury, hepatic macrophages are a highly heterogeneous population of immune cells that perform multiple functions in homeostasis, disease progression, and resolution of injury (Zimmermann et al., 2012; Tacke and Zimmermann, 2014). Furthermore, macrophages help to clear pathogens or cellular debris and to maintain immune tolerance under homeostatic conditions (Fallowfield et al., 2007), promoting hepatic fibrosis through activation of hepatic stellate cells in chronic liver damage (Imamura et al., 2005; Mitchell et al., 2009), ultimately underscoring their central role in tissue response to injury and inflammation (Miura et al., 2012).

In addition to macrophage infiltration into tissue, bone formation (Stechschulte et al., 2016), bone resorption (Stechschulte et al., 2016), anti-atherogenesis (Grbić et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020a; Zahr et al., 2022), inflammation (Yang et al., 2016), metabolic rhythmicity (He et al., 2022), lung fibrotic sequelae (Huang et al., 2019a), and adipose tissue browning (Qiang et al., 2012) are regulated by PPARγ post-translational modifications. Multiple factors regulate PPARγ expression levels, which may affect the polarization of macrophages, and thus affect the disease process (Doyle et al., 2002; Gu et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2021).

5 PPARγ related signaling pathways in macrophage regulation

Activated macrophages express significant levels of PPARγ (Chawla et al., 2001b). The absence of PPARγ signaling leads to continued secretion of high levels of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages (Bouhlel et al., 2007), indicating that PPARγ may have multiple effects on macrophage state. Studies have demonstrated that PPARγ agonists act as negative regulators of monocytes and macrophages, inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNFa, IL-1b, and IL-6 (Jiang et al., 1998; Reddy, 2008). Moreover, the PPARγ agonist rosiglitazone has been shown to suppress the expression of proinflammatory cytokines induced by LPS, particularly at higher concentrations (Welch et al., 2003).

Inflammation and oxidative stress caused by macrophages are common pathological processes that accompany, promote and even trigger various cancers or various chronic metabolic diseases, such as aging, obesity, Alzheimer’s disease, etc. Many of them involved in Wnt/β-catenin, p-JNK, p-AKT, AMPK/eNOS, etc (Khansari et al., 2009). 1) Activation of the canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway induces PPARγ inactivation, whereas PPARγ activation induces inhibition of canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling. The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is increased while PPARγ is downregulated in pathogenesis (Vallée et al., 2018). 2) PPARγ-dependent mechanism downregulates cardiovascular, inflammatory markers through p-JNK signaling (Mohanty et al., 2004). 3) TZDs prevent cardiomyocyte apoptosis through PPARγ ligand-dependent induction of upregulation of AKT phosphorylation (Kilter et al., 2009). 4) Activation of PPARγ induces phenotypic changes from M1 to M2 in macrophages at sites of inflammation through a heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1)-dependent mechanism (von Knethen et al., 2011). 5) Evidence that activation of PPARγ by TZDs regulates muscle and cardiac glucose metabolism through AMPK (Ye et al., 2006) and AMPK/eNOS phosphorylation (Xiao et al., 2010), respectively.

6 PPARγ and cholesterol metabolism in macrophages

Monocytes migrate to the arterial wall and undergo differentiation into macrophage “foam cells,” characterized by the accumulation of cholesteryl esters, a key feature of early and advanced atherosclerotic lesions. The uptake of modified forms of Low-density lipoprotein (LDL), particularly through scavenger receptors (SR-A), is believed to mediate cholesterol accumulation in macrophages (Krieger and Herz, 1994; de Villiers and Smart, 1999). SR-A recognizes acetylated and oxidized LDL, while CD36 exhibits greater selectivity for oxidized LDL (oxLDL), resulting in reduced uptake and degradation by macrophages from CD36-null mice compared to control macrophages (Podrez et al., 2000). Given the strong expression of PPARγ in macrophages within atherosclerotic plaques (Ricote et al., 1998), it was hypothesized that pharmacological activation of PPARγ could reduce plaque inflammation and impairments. Supporting this hypothesis, the Evans lab demonstrated that components of oxLDL, specifically 9- and 13-hydroxyoctanoic acid (HODE), transcriptionally activate PPARγ, implicating PPARγ in promoting atherogenesis (Nagy et al., 1998; Tontonoz et al., 1998). Consequently, activation of the LXR/RXR heterodimer via the PPARγ pathway upregulates the expression of ApoE, ABCA1, and SREBP1c, facilitating cholesterol outflow in macrophages and reinforcing reverse cholesterol transport to diminish lipid accumulation in macrophages (Janowski et al., 1996; Li et al., 2004).

The effects of PPARγ activation vary depending on the nature of the activator. Notably, exposure of macrophages to oxLDL has been reported to activate PPARγ in a PKC-dependent manner (Nagy et al., 1998; Feng et al., 2000). To date, CD36 has been identified as the canonical macrophage gene directly regulated by PPARγ, leading to enhanced CD36 expression and subsequent stimulation of oxLDL uptake (Febbraio et al., 2000; Rahaman et al., 2006). Consequently, exogenous activation of the PPARγ ligand-dependent pathway may promote CD36 expression and oxLDL uptake. However, in PPARγ-null macrophages, the loss of CD36 regulation does not significantly alter lipid uptake, suggesting that PPARγ-CD36 does not solely govern the pathway for oxLDL uptake (Chawla et al., 2001a). Furthermore, PPARγ can enhance cholesterol efflux from cells by inducing the expression of LXRα.

7 Therapeutic potential and challenges associated with modulating PPARγ

Modulating PPARγ in macrophages holds significant therapeutic promise for various diseases. Which are involved in anti-inflammatory, metabolic disorders, immunomodulation and tissue repair and regeneration. Activating PPARγ can shift macrophage polarization towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, dampening excessive inflammation and promoting tissue repair (Eming et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2018; Abdalla et al., 2020; Wculek et al., 2022). This approach shows potential in treating chronic inflammatory conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and metabolic disorders such as diabetes and dyslipidemia (Gu et al., 2014; Jalil et al., 2014; Baillie et al., 2017; Na et al., 2019; Cataldi et al., 2021). Additionally, PPARγ activation can modulate macrophage phagocytosis, antigen presentation, and cytokine production, influencing the overall immune response (Yu et al., 2016; Ciavarella et al., 2020; Mierzejewski et al., 2022). Harnessing these immunomodulatory effects may hold potential in immunotherapeutic strategies and cancer treatment, as macrophages play a critical role in tumor microenvironments.

However, challenges need to be addressed for successful clinical applications. One such challenge is the off-target effects: PPARγ is widely expressed in various tissues, and its modulation may have unintended effects on other cell types beyond macrophages (Ahmadian et al., 2013). These off-target effects could lead to adverse reactions and complicate treatment strategies. Furthermore, the context-specific nature of PPARγ modulation presents complexities, as therapeutic outcomes may vary depending on the disease context and microenvironment (Kung and Henry, 2012). Tailored approaches for different diseases may be necessary to optimize treatment efficacy (Mayerson et al., 2002). Patient heterogeneity also poses a challenge, as individual responses to PPARγ modulation may be influenced by genetic and environmental factors (Liu et al., 2020b). Implementing personalized medicine approaches will be essential to maximize treatment benefits and minimize potential risks.

In conclusion, targeting PPARγ in macrophages presents exciting therapeutic possibilities for various diseases. However, addressing the challenges, such as off-target effects, drug-specific effects, and patient heterogeneity, is essential to realize the full potential of PPARγ modulation for effective and safe clinical applications. Continued researches and clinical trials are necessary to unravel the complexities and refine the use of PPARγ modulation in the context of macrophages for precision medicine approaches.

8 PPARγ antagonists and their therapeutic potential

Considering the high expression of PPARγ in the pro-inflammatory state and the partial anti-inflammatory properties of PPARγ activation, PPARγ seems to play a role in the regulation of macrophage lipid metabolism in activated macrophages. Overactivation and persistent chronic inflammation are major pathogenic features of impaired healing in multiple metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis, SARS-CoV-2 et, al. (Yu et al., 2019; Jabbari et al., 2021; Kumar et al., 2021; Eleftheriotis et al., 2023).The overactivation of phagocytes can be inhibited by PPARγ antagonists, in addition to rebalancing the lipid metabolism and glucose metabolism of macrophages, it also improves the pro-inflammatory state of macrophages in the immune tolerant state (Toobian et al., 2021), and PPARγ was also regard as modulator of inflammation in pulmonary sarcoidosis (Pejcić et al., 2013). The use of PPARγ antagonists is also a novel therapeutic strategy being explored, for example, as it pertains to the ability of PPARγ antagonists to regulate lipid metabolism in mouse models of type 2 diabetes (T2DM), like the Gleevec, a renowned anticancer drug, acts as a PPARγ ligand without classical agonism, inhibiting PPARγ phosphorylation at S273 (Rieusset et al., 2002; Burton et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2015; Choi et al., 2016), cervical cancer (An et al., 2014), and to inhibit adipose tissue differentiation (Wright et al., 2000). Additionally, PPARγ antagonists are considered a potentially novel oncology therapeutic because of their antiproliferative effects on cancer cells (Burton et al., 2008). Furthermore, there is a vital link between fatty acid metabolism and tumorigenesis (Hoy et al., 2021), especially in adipose tissue organ-related breast cancer (Seargent et al., 2004; Zaytseva et al., 2011). Of most interest, PPARγ antagonists (GW9662) play a role in macrophage differentiation, regulating the expression of apoptosis-phagocytosis genes in apoptotic cells (Seargent et al., 2004; Majai et al., 2007) and inhibits growth of breast tumour cells (Seargent et al., 2004), which support a PPARγ-mediated transrepression mechanism, previously shown to be responsible for the anti-inflammatory effects of PPARγ ligands through the NF-κB signaling pathway (Pascual et al., 2005). As previously mentioned, immunosuppressive macrophages functions include post-infection repair and clearance of debris (Cui and Ferrucci, 2020). Additional studies below elaborate on PPARγ antagonists and their related application (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| PPARγ antagonist | Indication | Functional related | Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW9662 | Cancer, T2DM, Obesity | Tumor growth inhibition, Cell differentiation and apoptosis-phagocytosis | Preclinical | Rieusset et al. (2002), Seargent et al. (2004), Majai et al. (2007) |

| T0070907 | Cervical cancer | Increase G2/M phase cell ratio | Preclinical | Zaytseva et al. (2011), An et al. (2014) |

| Mifobate (SR-202) | Obesity, T2DM | Improve adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance | Phase II clinical trials | Rieusset et al. (2002) |

| Bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) | Adipocyte differentiation, PPARγ ligand | Wright et al. (2000) | ||

| N-((1H-benzo[d]imidazol-2-yl)methyl) aniline (Compound Q) | Reduce RXRa-PPARγ heterodimer activity | Wang et al. (2015) | ||

| Betulinic acid | HIV, malaria dysplastic, nevus syndrome, melanoma | Induces apoptosis, Increases ROS and caspase activation | Phase II clinical trials | Huang et al. (2018), Jiang et al. (2021), Oliveira-Costa et al. (2022) |

| Gleevec | Leukemia, T2DM | Inhibits tyrosine kinase, Improve insulin resistance | Approved | Lin et al. (2013), Choi et al. (2016) |

PPAR antagonists in development.

Conclusion

Over the past decade, much has been learned about the function of PPARs in macrophages. While initial studies focused on the transcriptional mechanisms by which PPARγ may regulate cholesterol metabolism in macrophages, recent work has elucidated several novel regulatory roles for PPARγ during pathological changes. Furthermore, the elucidation of macrophage activation and diverse signaling pathways provides multiple possible explanations for the mechanisms that integrate lipid signaling into macrophage activation. The in-depth studies performed to date on the PPARγ-macrophage mechanism will provide guidance for the application and development of PPARγ antagonists as well as potential regulation of other nuclear receptors.

Statements

Author contributions

LY: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. YG: Writing–review and editing. NA: Writing–review and editing. LQ: Funding acquisition, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by NIH R01DK112943 (LQ), R00DK97455 (LQ), P30DK063608 pilot grant (LQ), the Russell Berrie Foundation (LQ).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Abdalla H. B. Napimoga M. H. Lopes A. H. de Macedo Maganin A. G. Cunha T. M. Van Dyke T. E. et al (2020). Activation of PPAR-γ induces macrophage polarization and reduces neutrophil migration mediated by heme oxygenase 1. Int. Immunopharmacol.84, 106565. 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106565

2

Ahmadian M. Suh J. M. Hah N. Liddle C. Atkins A. R. Downes M. et al (2013). PPARγ signaling and metabolism: The good, the bad and the future. Nat. Med.19 (5), 557–566. 10.1038/nm.3159

3

Alleva D. G. Johnson E. B. Lio F. M. Boehme S. A. Conlon P. J. Crowe P. D. (2002). Regulation of murine macrophage proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines by ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ: Counter-regulatory activity by IFN-γ. J. Leukoc. Biol.71 (4), 677–685. 10.1189/jlb.71.4.677

4

An Z. Muthusami S. Yu J. R. Park W. Y. (2014). T0070907, a PPAR γ inhibitor, induced G2/M arrest enhances the effect of radiation in human cervical cancer cells through mitotic catastrophe. Reprod. Sci.21 (11), 1352–1361. 10.1177/1933719114525265

5

Aronoff D. M. Serezani C. H. Carstens J. K. Marshall T. Gangireddy S. R. Peters-Golden M. et al (2007). Stimulatory effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma on fcgamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages. PPAR Res.2007, 52546. 10.1155/2007/52546

6

Baillie J. K. Arner E. Daub C. De Hoon M. Itoh M. Kawaji H. et al (2017). Analysis of the human monocyte-derived macrophage transcriptome and response to lipopolysaccharide provides new insights into genetic aetiology of inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS Genet.13 (3), e1006641. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006641

7

Berger J. Moller D. E. (2002). The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annu. Rev. Med.53, 409–435. 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018

8

Blum J. I. Bijli K. M. Murphy T. C. Kleinhenz J. M. Hart C. M. (2016). Time-dependent PPARγ modulation of HIF-1α signaling in hypoxic pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Am. J. Med. Sci.352 (1), 71–79. 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.03.019

9

Bouhlel M. A. Derudas B. Rigamonti E. Dièvart R. Brozek J. Haulon S. et al (2007). PPARgamma activation primes human monocytes into alternative M2 macrophages with anti-inflammatory properties. Cell Metab.6 (2), 137–143. 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.010

10

Burton J. D. Goldenberg D. M. Blumenthal R. D. (2008). Potential of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma antagonist compounds as therapeutic agents for a wide range of cancer types. PPAR Res.2008, 494161. 10.1155/2008/494161

11

Cataldi S. Costa V. Ciccodicola A. Aprile M. (2021). PPARγ and diabetes: Beyond the genome and towards personalized medicine. Curr. Diabetes Rep.21 (6), 18. 10.1007/s11892-021-01385-5

12

Chawla A. Barak Y. Nagy L. Liao D. Tontonoz P. Evans R. M. (2001a). PPAR-gamma dependent and independent effects on macrophage-gene expression in lipid metabolism and inflammation. Nat. Med.7 (1), 48–52. 10.1038/83336

13

Chawla A. (2010). Control of macrophage activation and function by PPARs. Circ. Res.106 (10), 1559–1569. 10.1161/circresaha.110.216523

14

Chawla A. Repa J. J. Evans R. M. Mangelsdorf D. J. (2001b). Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: Opening the X-files. Science294 (5548), 1866–1870. 10.1126/science.294.5548.1866

15

Chawla A. Schwarz E. J. Dimaculangan D. D. Lazar M. A. (1994). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma: Adipose-predominant expression and induction early in adipocyte differentiation. Endocrinology135 (2), 798–800. 10.1210/endo.135.2.8033830

16

Chen H. Shi R. Luo B. Yang X. Qiu L. Xiong J. et al (2015). Macrophage peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ deficiency delays skin wound healing through impairing apoptotic cell clearance in mice. Cell Death Dis.6 (1), e1597. 10.1038/cddis.2014.544

17

Chen L. Zhang J. Zou Y. Wang F. Li J. Sun F. et al (2021). Kdm2a deficiency in macrophages enhances thermogenesis to protect mice against HFD-induced obesity by enhancing H3K36me2 at the Pparg locus. Cell Death Differ.28 (6), 1880–1899. 10.1038/s41418-020-00714-7

18

Chen Y. Jimenez A. R. Medh J. D. (2006). Identification and regulation of novel PPAR-γ splice variants in human THP-1 macrophages. Biochimica Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Gene Struct. Expr.1759 (1), 32–43. 10.1016/j.bbaexp.2006.01.005

19

Choi S. S. Kim E. S. Jung J. E. Marciano D. P. Jo A. Koo J. Y. et al (2016). PPARγ antagonist Gleevec improves insulin sensitivity and promotes the browning of white adipose tissue. Diabetes65 (4), 829–839. 10.2337/db15-1382

20

Ciavarella C. Motta I. Valente S. Pasquinelli G. (2020). Pharmacological (or synthetic) and nutritional agonists of PPAR-γ as candidates for cytokine storm modulation in COVID-19 disease. Molecules25 (9), 2076. 10.3390/molecules25092076

21

Cui C. Y. Ferrucci L. (2020). Macrophages in skeletal muscle aging. Aging (Albany NY)12 (1), 3–4. 10.18632/aging.102740

22

de Villiers W. J. Smart E. J. (1999). Macrophage scavenger receptors and foam cell formation. J. Leukoc. Biol.66 (5), 740–746. 10.1002/jlb.66.5.740

23

Doyle S. Vaidya S. O'Connell R. Dadgostar H. Dempsey P. Wu T. et al (2002). IRF3 mediates a TLR3/TLR4-specific antiviral gene program. Immunity17 (3), 251–263. 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00390-4

24

Eleftheriotis G. Tsounis E. P. Aggeletopoulou I. Dousdampanis P. Triantos C. Mouzaki A. et al (2023). Alterations in gut immunological barrier in SARS-CoV-2 infection and their prognostic potential. Front. Immunol.14, 1129190. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1129190

25

Eming S. A. Wynn T. A. Martin P. (2017). Inflammation and metabolism in tissue repair and regeneration. Science356 (6342), 1026–1030. 10.1126/science.aam7928

26

Escher P. Wahli W. (2000). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Insight into multiple cellular functions. Mutat. Research/Fundamental Mol. Mech. Mutagen.448 (2), 121–138. 10.1016/S0027-5107(99)00231-6

27

Fallowfield J. A. Mizuno M. Kendall T. J. Constandinou C. M. Benyon R. C. Duffield J. S. et al (2007). Scar-associated macrophages are a major source of hepatic matrix metalloproteinase-13 and facilitate the resolution of murine hepatic fibrosis. J. Immunol.178 (8), 5288–5295. 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5288

28

Febbraio M. Podrez E. A. Smith J. D. Hajjar D. P. Hazen S. L. Hoff H. F. et al (2000). Targeted disruption of the class B scavenger receptor CD36 protects against atherosclerotic lesion development in mice. J. Clin. Invest.105 (8), 1049–1056. 10.1172/jci9259

29

Feng J. Han J. Pearce S. F. Silverstein R. L. Gotto A. M. Jr. Hajjar D. P. et al (2000). Induction of CD36 expression by oxidized LDL and IL-4 by a common signaling pathway dependent on protein kinase C and PPAR-γ. J. Lipid Res.41 (5), 688–696. 10.1016/s0022-2275(20)32377-4

30

Gallardo-Soler A. Gómez-Nieto C. Campo M. L. Marathe C. Tontonoz P. Castrillo A. et al (2008). Arginase I induction by modified lipoproteins in macrophages: A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma/delta-mediated effect that links lipid metabolism and immunity. Mol. Endocrinol.22 (6), 1394–1402. 10.1210/me.2007-0525

31

Ginhoux F. (2014). Fate PPAR-titioning: PPAR-γ 'instructs' alveolar macrophage development. Nat. Immunol.15 (11), 1005–1007. 10.1038/ni.3011

32

Giusti V. Verdumo C. Suter M. Gaillard R. C. Burckhardt P. Pralong F. (2003). Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma2 in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women. Diabetes52 (7), 1673–1676. 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1673

33

Glass C. K. Natoli G. (2016). Molecular control of activation and priming in macrophages. Nat. Immunol.17 (1), 26–33. 10.1038/ni.3306

34

Glass C. K. Ogawa S. (2006). Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol.6 (1), 44–55. 10.1038/nri1748

35

Glass C. K. Saijo K. (2010). Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol.10 (5), 365–376. 10.1038/nri2748

36

Gordon S. (2003). Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat. Rev. Immunol.3 (1), 23–35. 10.1038/nri978

37

Gordon S. Plüddemann A. Martinez Estrada F. (2014). Macrophage heterogeneity in tissues: Phenotypic diversity and functions. Immunol. Rev.262 (1), 36–55. 10.1111/imr.12223

38

Gordon S. Taylor P. R. (2005). Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat. Rev. Immunol.5 (12), 953–964. 10.1038/nri1733

39

Gosselin D. Link V. M. Romanoski C. E. Fonseca G. J. Eichenfield D. Z. Spann N. J. et al (2014). Environment drives selection and function of enhancers controlling tissue-specific macrophage identities. Cell159 (6), 1327–1340. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.023

40

Gosset P. Charbonnier A. S. Delerive P. Fontaine J. Staels B. Pestel J. et al (2001). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators affect the maturation of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Eur. J. Immunol.31 (10), 2857–2865. 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2857::aid-immu2857>3.0.co;2-x

41

Grbić E. Peterlin A. Kunej T. Petrovič D. (2018). PPARγ gene and atherosclerosis: Genetic polymorphisms, epigenetics and therapeutic implications. Balk. J. Med. Genet. 21 (1), 39–46. 10.2478/bjmg-2018-0011

42

Gu S.-J. Guo Z.-R. Zhou Z.-Y. Hu X.-S. Wu M. (2014). PPAR α and PPAR γ polymorphisms as risk factors for dyslipidemia in a Chinese Han population. Lipids Health Dis.13 (1), 23. 10.1186/1476-511X-13-23

43

Gu X. Zhang Y. Li D. Cai H. Cai L. Xu Q. (2020). N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO promotes M1 and M2 macrophage activation. Cell Signal69, 109553. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109553

44

Guerriero J. L. (2019). Macrophages: Their untold story in T cell activation and function. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol.342, 73–93. 10.1016/bs.ircmb.2018.07.001

45

Harmon G. S. Lam M. T. Glass C. K. (2011). PPARs and lipid ligands in inflammation and metabolism. Chem. Rev.111 (10), 6321–6340. 10.1021/cr2001355

46

He Y. B'Nai Taub A. Yu L. Yao Y. Zhang R. Zahr T. et al (2022). PPARγ acetylation orchestrates adipose plasticity and metabolic rhythms. Adv. Sci. (Weinh)10, e2204190. 10.1002/advs.202204190

47

Heming M. Gran S. Jauch S. L. Fischer-Riepe L. Russo A. Klotz L. et al (2018). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ modulates the response of macrophages to lipopolysaccharide and glucocorticoids. Front. Immunol.9, 893. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00893

48

Hevener A. L. Olefsky J. M. Reichart D. Nguyen M. T. Bandyopadyhay G. Leung H. Y. et al (2007). Macrophage PPAR gamma is required for normal skeletal muscle and hepatic insulin sensitivity and full antidiabetic effects of thiazolidinediones. J. Clin. Invest.117 (6), 1658–1669. 10.1172/jci31561

49

Hosogai N. Fukuhara A. Oshima K. Miyata Y. Tanaka S. Segawa K. et al (2007). Adipose tissue hypoxia in obesity and its impact on adipocytokine dysregulation. Diabetes56 (4), 901–911. 10.2337/db06-0911

50

Hoy A. J. Nagarajan S. R. Butler L. M. (2021). Tumour fatty acid metabolism in the context of therapy resistance and obesity. Nat. Rev. Cancer21 (12), 753–766. 10.1038/s41568-021-00388-4

51

Huang J. T. Welch J. S. Ricote M. Binder C. J. Willson T. M. Kelly C. et al (1999). Interleukin-4-dependent production of PPAR-gamma ligands in macrophages by 12/15-lipoxygenase. Nature400 (6742), 378–382. 10.1038/22572

52

Huang Q. X. Chen H. F. Luo X. R. Zhang Y. X. Yao X. Zheng X. (2018). Structure and anti-HIV activity of betulinic acid analogues. Curr. Med. Sci.38 (3), 387–397. 10.1007/s11596-018-1891-4

53

Huang S. Goplen N. P. Zhu B. Cheon I. S. Son Y. Wang Z. et al (2019a). Macrophage PPAR-γ suppresses long-term lung fibrotic sequelae following acute influenza infection. PLoS One14 (10), e0223430. 10.1371/journal.pone.0223430

54

Huang S. Zhu B. Cheon I. S. Goplen N. P. Jiang L. Zhang R. et al (2019b). PPAR-Γ in macrophages limits pulmonary inflammation and promotes host recovery following respiratory viral infection. J. Virology93(9), 000300-e119. 10.1128/JVI.00030-19

55

Imamura M. Ogawa T. Sasaguri Y. Chayama K. Ueno H. (2005). Suppression of macrophage infiltration inhibits activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrogenesis in rats. Gastroenterology128 (1), 138–146. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.005

56

Ito A. Hong C. Rong X. Zhu X. Tarling E. J. Hedde P. N. et al (2015). LXRs link metabolism to inflammation through Abca1-dependent regulation of membrane composition and TLR signaling. Elife4, e08009. 10.7554/eLife.08009

57

Jabbari P. Sadeghalvad M. Rezaei N. (2021). An inflammatory triangle in sarcoidosis: PPAR-γ, immune microenvironment, and inflammation. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther.21 (11), 1451–1459. 10.1080/14712598.2021.1913118

58

Jalil S. F. Ahmed I. Gauhar Z. Ahmed M. Malik J. M. John P. et al (2014). Association of Pro12Ala (rs1801282) variant of PPAR gamma with rheumatoid arthritis in a Pakistani population. Rheumatol. Int.34 (5), 699–703. 10.1007/s00296-013-2768-2

59

Janowski B. A. Willy P. J. Devi T. R. Falck J. R. Mangelsdorf D. J. (1996). An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXR alpha. Nature383 (6602), 728–731. 10.1038/383728a0

60

Jiang C. Ting A. T. Seed B. (1998). PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature391 (6662), 82–86. 10.1038/34184

61

Jiang W. Li X. Dong S. Zhou W. (2021). Betulinic acid in the treatment of tumour diseases: Application and research progress. Biomed. Pharmacother.142, 111990. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111990

62

Kamei Y. Xu L. Heinzel T. Torchia J. Kurokawa R. Gloss B. et al (1996). A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell85 (3), 403–414. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81118-6

63

Kanda H. Tateya S. Tamori Y. Kotani K. Hiasa K. Kitazawa R. et al (2006). MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J. Clin. Invest.116 (6), 1494–1505. 10.1172/jci26498

64

Khansari N. Shakiba Y. Mahmoudi M. (2009). Chronic inflammation and oxidative stress as a major cause of age-related diseases and cancer. Recent Pat. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Discov.3 (1), 73–80. 10.2174/187221309787158371

65

Kilter H. Werner M. Roggia C. Reil J. C. Schäfers H. J. Kintscher U. et al (2009). The PPAR-γ agonist rosiglitazone facilitates Akt rephosphorylation and inhibits apoptosis in cardiomyocytes during hypoxia/reoxygenation. Diabetes, Obes. Metabolism11 (11), 1060–1067. 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01097.x

66

Kliewer S. A. Forman B. M. Blumberg B. Ong E. S. Borgmeyer U. Mangelsdorf D. J. et al (1994). Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.91 (15), 7355–7359. 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7355

67

Kliewer S. A. Sundseth S. S. Jones S. A. Brown P. J. Wisely G. B. Koble C. S. et al (1997). Fatty acids and eicosanoids regulate gene expression through direct interactions with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and gamma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.94 (9), 4318–4323. 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4318

68

Krieger M. Herz J. (1994). Structures and functions of multiligand lipoprotein receptors: Macrophage scavenger receptors and LDL receptor-related protein (LRP). Annu. Rev. Biochem.63, 601–637. 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.003125

69

Kumar N. Sharma N. Mehan S. (2021). Connection between JAK/STAT and PPARγ signaling during the progression of multiple sclerosis: Insights into the modulation of T-cells and immune responses in the brain. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol.14 (5), 823–837. 10.2174/1874467214666210301121432

70

Kung J. Henry R. R. (2012). Thiazolidinedione safety. Expert Opin. Drug Saf.11 (4), 565–579. 10.1517/14740338.2012.691963

71

Li A. C. Binder C. J. Gutierrez A. Brown K. K. Plotkin C. R. Pattison J. W. et al (2004). Differential inhibition of macrophage foam-cell formation and atherosclerosis in mice by PPARalpha, beta/delta, and gamma. J. Clin. Invest.114 (11), 1564–1576. 10.1172/jci18730

72

Li J. Wang J. Wang J. Nawaz Z. Liu J. M. Qin J. et al (2000). Both corepressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. Embo J.19 (16), 4342–4350. 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4342

73

Li L. Fu J. Liu D. Sun J. Hou Y. Chen C. et al (2020). Hepatocyte-specific Nrf2 deficiency mitigates high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis: Involvement of reduced PPARγ expression. Redox Biol.30, 101412. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101412

74

Li P. Spann N. J. Kaikkonen M. U. Lu M. Oh D. Y. Fox J. N. et al (2013). NCoR repression of LXRs restricts macrophage biosynthesis of insulin-sensitizing omega 3 fatty acids. Cell155 (1), 200–214. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.054

75

Lin Y. L. Meng Y. Jiang W. Roux B. (2013). Explaining why Gleevec is a specific and potent inhibitor of Abl kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.110 (5), 1664–1669. 10.1073/pnas.1214330110

76

Liu L. Fan L. Chan M. Kraakman M. J. Yang J. Fan Y. et al (2020a). PPARγ deacetylation confers the antiatherogenic effect and improves endothelial function in diabetes treatment. Diabetes69 (8), 1793–1803. 10.2337/db20-0217

77

Liu L. Wang J. Luo S. Zhan Y. Lu Q. (2020b). The roles of PPARγ and its agonists in autoimmune diseases: A comprehensive review. J. Autoimmun.113, 102510. 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102510

78

Lolmède K. Bouloumié A. Durand de Saint Front V. Galitzky J. Lafontan M. Bouloumié A. (2003). Effects of hypoxia on the expression of proangiogenic factors in differentiated 3T3-F442A adipocytes. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord.27(10), 1187–1195. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802407

79

Majai G. Sarang Z. Csomós K. Zahuczky G. Fésüs L. (2007). PPARgamma-dependent regulation of human macrophages in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Eur. J. Immunol.37 (5), 1343–1354. 10.1002/eji.200636398

80

Mayerson A. B. Hundal R. S. Dufour S. Lebon V. Befroy D. Cline G. W. et al (2002). The effects of rosiglitazone on insulin sensitivity, lipolysis, and hepatic and skeletal muscle triglyceride content in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes51 (3), 797–802. 10.2337/diabetes.51.3.797

81

Mierzejewski K. Paukszto Ł. Kurzyńska A. Kunicka Z. Jastrzębski J. P. Makowczenko K. G. et al (2022). PPARγ regulates the expression of genes involved in the DNA damage response in an inflamed endometrium. Sci. Rep.12 (1), 4026. 10.1038/s41598-022-07986-8

82

Mitchell C. Couton D. Couty J.-P. Anson M. Crain A.-M. Bizet V. et al (2009). Dual role of CCR2 in the constitution and the resolution of liver fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Pathology174 (5), 1766–1775. 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080632

83

Miura K. Yang L. van Rooijen N. Ohnishi H. Seki E. (2012). Hepatic recruitment of macrophages promotes nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through CCR2. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiology302 (11), G1310–G1321. 10.1152/ajpgi.00365.2011

84

Mohanty P. Aljada A. Ghanim H. Hofmeyer D. Tripathy D. Syed T. et al (2004). Evidence for a potent antiinflammatory effect of rosiglitazone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism89 (6), 2728–2735. 10.1210/jc.2003-032103

85

Na Y. R. Stakenborg M. Seok S. H. Matteoli G. (2019). Macrophages in intestinal inflammation and resolution: A potential therapeutic target in IBD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterology Hepatology16 (9), 531–543. 10.1038/s41575-019-0172-4

86

Nagy L. Tontonoz P. Alvarez J. G. Chen H. Evans R. M. (1998). Oxidized LDL regulates macrophage gene expression through ligand activation of PPARgamma. Cell93 (2), 229–240. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81574-3

87

Nelson V. L. Nguyen H. C. B. Garcìa-Cañaveras J. C. Briggs E. R. Ho W. Y. DiSpirito J. R. et al (2018). PPARγ is a nexus controlling alternative activation of macrophages via glutamine metabolism. Genes Dev.32 (15-16), 1035–1044. 10.1101/gad.312355.118

88

Nguyen M. T. Satoh H. Favelyukis S. Babendure J. L. Imamura T. Sbodio J. I. et al (2005). JNK and tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediate free fatty acid-induced insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J. Biol. Chem.280 (42), 35361–35371. 10.1074/jbc.M504611200

89

Odegaard J. I. Ricardo-Gonzalez R. R. Goforth M. H. Morel C. R. Subramanian V. Mukundan L. et al (2007). Macrophage-specific PPARgamma controls alternative activation and improves insulin resistance. Nature447 (7148), 1116–1120. 10.1038/nature05894

90

Oliveira-Costa J. F. Meira C. S. Neves M. Dos Reis B. Soares M. B. P. (2022). Anti-inflammatory activities of betulinic acid: A review. Front. Pharmacol.13, 883857. 10.3389/fphar.2022.883857

91

Padilla J. Kaur K. Cao H. J. Smith T. J. Phipps R. P. (2000). Peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-gamma agonists and 15-deoxy-Delta(12,14)(12,14)-PGJ(2) induce apoptosis in normal and malignant B-lineage cells. J. Immunol.165 (12), 6941–6948. 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6941

92

Pascual G. Fong A. L. Ogawa S. Gamliel A. Li A. C. Perissi V. et al (2005). A SUMOylation-dependent pathway mediates transrepression of inflammatory response genes by PPAR-gamma. Nature437 (7059), 759–763. 10.1038/nature03988

93

Pejcić T. Stanković I. Petković T. R. Borovac D. N. Djordjević I. Jeftović-Stoimenov T. (2013). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma as modulator of inflammation in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Srp. Arh. Celok. Lek.141 (9-10), 705–709. 10.2298/sarh1310705p

94

Podrez E. A. Febbraio M. Sheibani N. Schmitt D. Silverstein R. L. Hajjar D. P. et al (2000). Macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 is the major receptor for LDL modified by monocyte-generated reactive nitrogen species. J. Clin. Invest.105 (8), 1095–1108. 10.1172/jci8574

95

Qiang L. Wang L. Kon N. Zhao W. Lee S. Zhang Y. et al (2012). Brown remodeling of white adipose tissue by SirT1-dependent deacetylation of Pparγ. Cell150 (3), 620–632. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.027

96

Rahaman S. O. Lennon D. J. Febbraio M. Podrez E. A. Hazen S. L. Silverstein R. L. (2006). A CD36-dependent signaling cascade is necessary for macrophage foam cell formation. Cell Metab.4 (3), 211–221. 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.007

97

Reddy R. C. (2008). Immunomodulatory role of PPAR-gamma in alveolar macrophages. J. Investig. Med.56 (2), 522–527. 10.2310/JIM.0b013e3181659972

98

Ren X. Manzanares L. D. Piccolo E. B. Urbanczyk J. M. Sullivan D. P. Yalom L. K. et al (2023). Macrophage-endothelial cell crosstalk orchestrates neutrophil recruitment in inflamed mucosa. J. Clin. Invest.2023, e170733. 10.1172/jci170733

99

Ricote M. Huang J. Fajas L. Li A. Welch J. Najib J. et al (1998). Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) in human atherosclerosis and regulation in macrophages by colony stimulating factors and oxidized low density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.95 (13), 7614–7619. 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7614

100

Rieusset J. Touri F. Michalik L. Escher P. Desvergne B. Niesor E. et al (2002). A new selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma antagonist with antiobesity and antidiabetic activity. Mol. Endocrinol.16 (11), 2628–2644. 10.1210/me.2002-0036

101

Rotondo D. Davidson J. (2002). Prostaglandin and PPAR control of immune cell function. Immunology105 (1), 20–22. 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01361.x

102

Sárvári A. K. Van Hauwaert E. L. Markussen L. K. Gammelmark E. Marcher A. B. Ebbesen M. F. et al (2021). Plasticity of epididymal adipose tissue in response to diet-induced obesity at single-nucleus resolution. Cell Metab.33 (2), 437–453.e5. 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.12.004

103

Seargent J. M. Yates E. A. Gill J. H. (2004). GW9662, a potent antagonist of PPARgamma, inhibits growth of breast tumour cells and promotes the anticancer effects of the PPARgamma agonist rosiglitazone, independently of PPARgamma activation. Br. J. Pharmacol.143 (8), 933–937. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705973

104

Setoguchi K. Misaki Y. Terauchi Y. Yamauchi T. Kawahata K. Kadowaki T. et al (2001). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma haploinsufficiency enhances B cell proliferative responses and exacerbates experimentally induced arthritis. J. Clin. Invest.108 (11), 1667–1675. 10.1172/jci13202

105

Shapouri-Moghaddam A. Mohammadian S. Vazini H. Taghadosi M. Esmaeili S. A. Mardani F. et al (2018). Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell Physiol.233 (9), 6425–6440. 10.1002/jcp.26429

106

Shi H. Kokoeva M. V. Inouye K. Tzameli I. Yin H. Flier J. S. (2006). TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. J. Clin. Invest.116 (11), 3015–3025. 10.1172/jci28898

107

Stechschulte L. A. Czernik P. J. Rotter Z. C. Tausif F. N. Corzo C. A. Marciano D. P. et al (2016). PPARG post-translational modifications regulate bone formation and bone resorption. EBioMedicine10, 174–184. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.040

108

Suganami T. Nishida J. Ogawa Y. (2005). A paracrine loop between adipocytes and macrophages aggravates inflammatory changes: Role of free fatty acids and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.25 (10), 2062–2068. 10.1161/01.atv.0000183883.72263.13

109

Tacke F. Zimmermann H. W. (2014). Macrophage heterogeneity in liver injury and fibrosis. J. Hepatology60 (5), 1090–1096. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.025

110

Tontonoz P. Nagy L. Alvarez J. G. Thomazy V. A. Evans R. M. (1998). PPARgamma promotes monocyte/macrophage differentiation and uptake of oxidized LDL. Cell93 (2), 241–252. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81575-5

111

Toobian D. Ghosh P. Katkar G. D. (2021). Parsing the role of PPARs in macrophage processes. Front. Immunol.12, 783780. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.783780

112

Trayhurn P. Wood I. S. (2004). Adipokines: Inflammation and the pleiotropic role of white adipose tissue. Br. J. Nutr.92 (3), 347–355. 10.1079/bjn20041213

113

Vallée A. Lecarpentier Y. Guillevin R. Vallée J. N. (2018). Opposite interplay between the canonical WNT/β-catenin pathway and PPAR gamma: A potential therapeutic target in gliomas. Neurosci. Bull.34 (3), 573–588. 10.1007/s12264-018-0219-5

114

Varga T. Mounier R. Patsalos A. Gogolák P. Peloquin M. Horvath A. et al (2016). Macrophage PPARγ, a lipid activated transcription factor controls the growth factor GDF3 and skeletal muscle regeneration. Immunity45 (5), 1038–1051. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.10.016

115

von Knethen A. Neb H. Morbitzer V. Schmidt M. V. Kuhn A.-M. Kuchler L. et al (2011). PPARγ stabilizes HO-1 mRNA in monocytes/macrophages which affects IFN-β expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med.51 (2), 396–405. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.04.033

116

Wang R. Dai L. Chen J. (2015). Identification of a proliferator-activated receptor-γ antagonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp. Ther. Med.9 (2), 446–450. 10.3892/etm.2014.2096

117

Wculek S. K. Dunphy G. Heras-Murillo I. Mastrangelo A. Sancho D. (2022). Metabolism of tissue macrophages in homeostasis and pathology. Cell. Mol. Immunol.19 (3), 384–408. 10.1038/s41423-021-00791-9

118

Welch J. S. Ricote M. Akiyama T. E. Gonzalez F. J. Glass C. K. (2003). PPARgamma and PPARdelta negatively regulate specific subsets of lipopolysaccharide and IFN-gamma target genes in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A.100 (11), 6712–6717. 10.1073/pnas.1031789100

119

Wright H. M. Clish C. B. Mikami T. Hauser S. Yanagi K. Hiramatsu R. et al (2000). A synthetic antagonist for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits adipocyte differentiation. J. Biol. Chem.275 (3), 1873–1877. 10.1074/jbc.275.3.1873

120

Xiao X. Su G. Brown S. N. Chen L. Ren J. Zhao P. (2010). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma and alpha agonists stimulate cardiac glucose uptake via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Nutr. Biochem.21 (7), 621–626. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.03.011

121

Xu J. Lv H. (2023). PSTPIP2 alleviates obesity associated adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance in diabetes mice through promoting M2 macrophage polarization via activation of PPARγ. J. Diabetes Complicat.37 (6), 108479. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2023.108479

122

Yang D. Chen H. Zeng X. Xie P. Wang X. Liu C. (2016). Macrophage CGI-58 attenuates inflammatory responsiveness via promotion of PPARγ signaling. Cell Physiol. Biochem.38 (2), 696–713. 10.1159/000443027

123

Ye J.-M. Dzamko N. Hoy A. J. Iglesias M. A. Kemp B. Kraegen E. (2006). Rosiglitazone treatment enhances acute AMP-activated protein kinase–mediated muscle and adipose tissue glucose uptake in high-fat–fed rats. Diabetes55 (10), 2797–2804. 10.2337/db05-1315

124

Yu J. Qiu Y. Yang J. Bian S. Chen G. Deng M. et al (2016). DNMT1-PPARγ pathway in macrophages regulates chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis development in mice. Sci. Rep.6, 30053. 10.1038/srep30053

125

Yu T. Gao M. Yang P. Liu D. Wang D. Song F. et al (2019). Insulin promotes macrophage phenotype transition through PI3K/Akt and PPAR-γ signaling during diabetic wound healing. J. Cell Physiol.234 (4), 4217–4231. 10.1002/jcp.27185

126

Zahr T. Liu L. Chan M. Zhou Q. Cai B. He Y. et al (2022). PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) deacetylation suppresses aging-associated atherosclerosis and hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.43, 30–44. 10.1161/atvbaha.122.318061

127

Zaytseva Y. Y. Wallis N. K. Southard R. C. Kilgore M. W. (2011). The PPARgamma antagonist T0070907 suppresses breast cancer cell proliferation and motility via both PPARgamma-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Anticancer Res.31 (3), 813–823.

128

Zhang J. Kalkum M. Chait B. T. Roeder R. G. (2002). The N-CoR-HDAC3 nuclear receptor corepressor complex inhibits the JNK pathway through the integral subunit GPS2. Mol. Cell9 (3), 611–623. 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00468-9

129

Zhu Y. Qi C. Korenberg J. R. Chen X. N. Noya D. Rao M. S. et al (1995). Structural organization of mouse peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (mPPAR gamma) gene: Alternative promoter use and different splicing yield two mPPAR gamma isoforms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.92 (17), 7921–7925. 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7921

130

Zimmermann H. W. Trautwein C. Tacke F. (2012). Functional role of monocytes and macrophages for the inflammatory response in acute liver injury. Front. physiology3, 56. 10.3389/fphys.2012.00056

Summary

Keywords

macrophage, antagonists, inflammatory diseases, PPARγ, anti-inflammatory

Citation

Yu L, Gao Y, Aaron N and Qiang L (2023) A glimpse of the connection between PPARγ and macrophage. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1254317. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1254317

Received

10 July 2023

Accepted

31 July 2023

Published

28 August 2023

Volume

14 - 2023

Edited by

Lian Xiang Luo, Guangdong Medical University, China

Reviewed by

Wei Yang, University of Georgia, United States

Xingsheng Ren, Northwestern University, United States

Mengyi Song, University of California, San Francisco, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2023 Yu, Gao, Aaron and Qiang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lexiang Yu, ylxconquer01@gmail.com; Li Qiang, lq2123@cumc.columbia.edu

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.