Abstract

Clerodendrum trichotomum Thunb. (C. trichotomum) is a shrub or tree of the genus Clerodendrum, family Lamiaceae, which is widely distributed in China, Korea, India, Japan and Philippines. C. trichotomum is a kind of medicinal and edible plant which integrates ecological afforestation, garden greening, herbal medicine and flavor wild vegetable. As a traditional Chinese medicine, C. trichotomum is used to treat various diseases and conditions, which has inspired research on the pharmacological activities of its different parts, including roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits. These studies have revealed many biological properties of C. trichotomum, such as antihypertensive, antitumor, antioxidant, antiinflammatory, antibacterial, analgesic, sedative, anti-HIV-1 and whitening. A total of 164 secondary metabolites were isolated from C. trichotomum, and their structural types were mainly terpenoids, flavonoids, steroids, phenylpropanoids and phenylpropanoid glycosides, phenylethanosides, phenolic glycosides, anthraquinones, polyketones, cyclohexylethanoids, alkaloids and acid amides. The presence of a variety of phytochemicals, especially abietane diterpenes, clerodane diterpenes, phenylpropanoid glycosides and flavonoid glycosides, plays an important role in the activity diversity of this plant. The current study is attempt to comprehensively compile information regarding the phytochemicals and pharmacological activities of C. trichotomum, provide the chemotaxonomic proof for the taxonomic classification of the plant, and also highlight the current gaps and propose possible bridges for the development of C. trichotomum as a therapeutic against important diseases.

1 Introduction

Clerodendrum trichotomum Thunb. is a deciduous shrub or small tree widely distributed in China, Korea, India, Japan and the northern Philippines (Figure 1), and can be mostly found in hillside scrub below 2,400 m above sea level (Chen and Michael, 1994). The first mentioning of C. trichotomum was recorded in the book of Bencao Tujing of Song Dynasty. Historically, due to its origin in Haizhou area of Lianyungang, Jiangsu province, it was once used as Changshan (another kind of Chinese medicine Dichroa febrifuga Lour.), so it is named Haizhou Changshan in China. It is also known as “Chou Wu Tong,” “Di Wu Tong,” “Ai Tong Zi” and so on (Chinese Materia Medica editorial board, 1999). The flowering period of C. trichotomum is from June to October, and the fruiting period is from August to November (Peng and Chen, 1982). The inflorescence is large, the flowers and fruits are gorgeous. Especially, the white flowers, the red calyx and the blue fruit can coexist on the same tree at the same time, and the three colors complement each other. The flowers and fruits can reach a half-year long ornamental period, so it is one of the rare summer flower plants and owes high ornamental value. C. trichotomum has strong resistance and large absorption to sulfur dioxide (SO2) (Zheng et al., 2006), strong tolerance and enrichment ability to heavy metal arsenic (Mahmud et al., 2008). In addition, it has strong stress resistance to drought, salt, waterlogging, barren, high temperature and so on (Xie et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2009; Xie et al., 2012; Zeng et al., 2013). Therefore, it is a suitable tree for urban landscaping, saline-alkali land greening and abandoned land vegetation restoration.

FIGURE 1

The orange spots in the map depicted the main region of Clerodendrum trichotomum Thunb.

C. trichotomum is mainly used as a folk remedy for the treatment of rheumatism, hemiplegia, hypertension, migraine, malaria and dysentery (Xie, 1996; Chinese Materia Medica editorial board, 1999). Its roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits can be used as medicine (Table 1). What’s more, the young leaves of C. trichotomum are a kind of green woody wild vegetable favoured by local residents in Guizhou, Hubei, Sichuan, Yunnan and other places of China because of their unique flavor, fresh taste and slightly sweet aftertaste. The leaves are non-toxic, bitter and cold in taste, with special flavor and rich in pectin, vegetable protein and a variety of amino acids. They are essential raw materials for Enshi Tujia to make “fairy tofu,” and have been favored by the majority of consumers because of their unique flavor and natural pollution-free (Wang, 2002), and can also be made into special drinks (Zheng et al., 2013).

TABLE 1

| Part use | Disease cure | Country/origin /Area |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roots | Rheumatism, asthma and other inflammatory diseases (arthritis) | Guang dong | Shrivastava and Patel (2007); Au et al. (2008) |

| Stems | Inflammatory skin conditions, headaches, hypertension, rheumatism, rheumatic articular pain and rheumatism fever | China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan | Nagao et al. (2001); Kang et al. (2003); Zhang et al. (2022); Ogunlakin et al. (2023); Yang et al. (2024) |

| Leaves | Asthma, inflammatory skin conditions, headache, hypertension, anti-rheumatic, rheumatism and rheumatic articular pain, rheumatism fever | China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, Nepal | Nagao et al. (2001); Shrivastava and Patel (2007); Subba et al. (2016); Ogunlakin et al. (2023); Yang et al. (2024) |

| Flowers | Inflammatory conditions, headache, and hypertension | China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan | Ogunlakin et al. (2023) |

| Fruits | Anticancer | China, Japan | Nagao et al. (2001); Gomulski and Grzegorczyk-Karolak (2024) |

| Raw material | Eczema | China | Gomulski and Grzegorczyk-Karolak (2024) |

| Decoctions | Rheumatoid arthritis, joint pain, numbness, and paralysis | China | Gomulski and Grzegorczyk-Karolak (2024) |

| All | Anti-diabetic, neuralgia, arthritis, cough, abdominal lump, anti-hypertensive and sedative | China, Korea | Bae et al. (2012); Gomulski and Grzegorczyk-Karolak (2024); Yang et al. (2024) |

Ethnobotany of Clerodendrum trichotomum Thunb.

C. trichotomum is a kind of medicine homologous food which integrates ecological afforestation, garden greening, traditional Chinese medicine and flavor wild vegetable. Despite the existence of many bioactive phytochemicals and some potential biological properties, only one recent review of C. trichotomum has been published and only 50 references have been reviewed (Gomulski and Grzegorczyk-Karolak, 2024). A complete and comprehensive compilation of the phytochemicals and pharmacological activities of C. trichotomum is still absent in the literature. This may be an important reason for the underutilization of this medicinal and edible plant. Hence, in the current study, the comprehensive compilation of phytochemicals as well as pharmacological activities of C. trichotomum has been attempted, which also highlights the current gaps and proposes possible bridges for the development of C. trichotomum as a therapeutic against important diseases. C. trichotomum belongs to the genus Clerodendrum. However, it is still debated whether the genus Clerodendrum belongs to the Labiaceae family or the Verbenaceae family. Genus Clerodendrum was assigned to family Verbenaceae traditionally by Engler and Prantl (Briquet, 1895). This classification method is also adopted in Flora of China (Peng and Chen, 1982; Chen and Michael, 1994). But modern taxonomic systems mostly put it in the family Lamiaceae (Latta, 2008). Therefore, a review of its chemical constituents is of great significance in chemotaxonomy for the scientific definition of its placement in the plant classification system.

2 Methodology

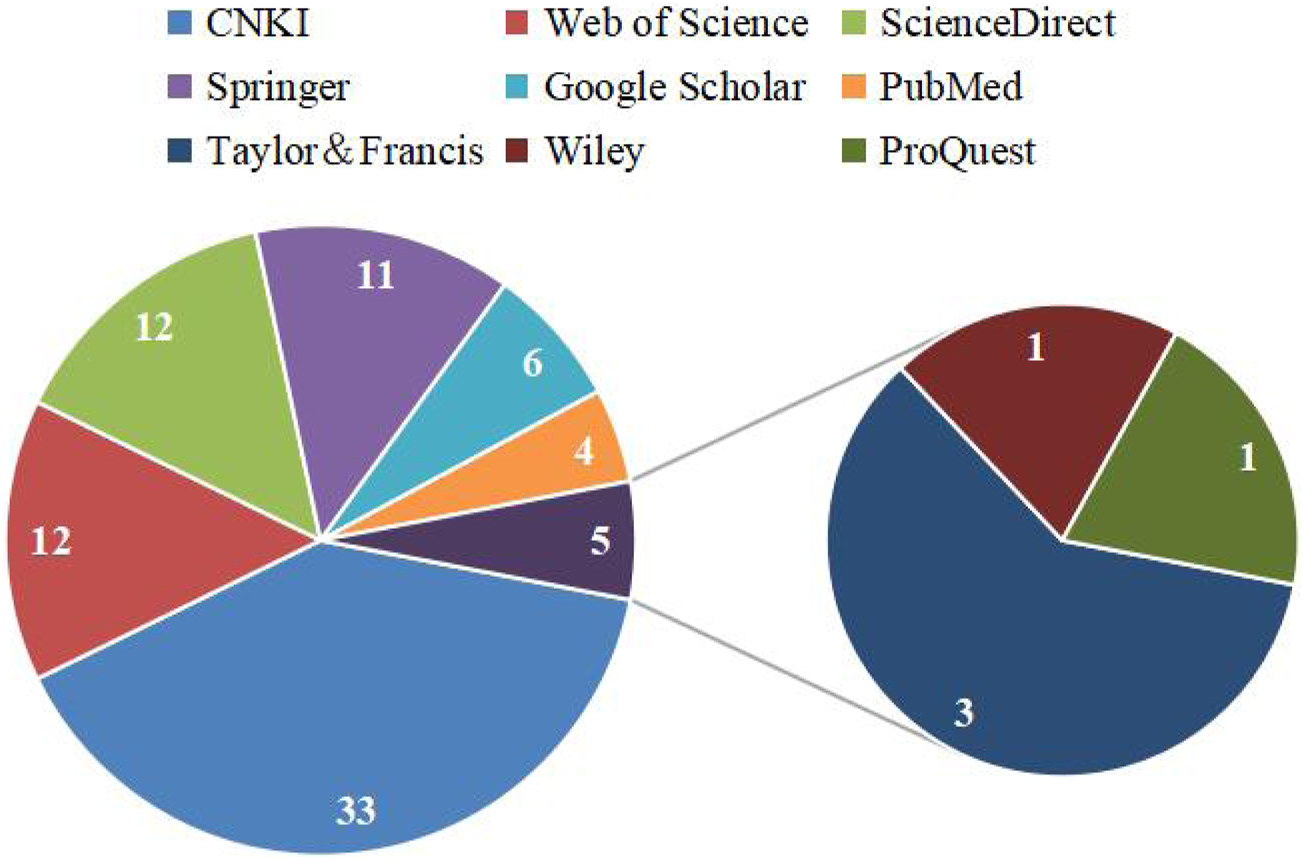

Information for this review was collected through several popular search engines and databases such as Web of Science, ScienceDirect, Springer, Google Scholar, PubMed, Taylor and Francis, Wiley, ProQuest, CNKI, and classic texts of Chinese herbal medicines (e.g., Bencao Tujing), and other websites, such as the Flora of China, the Plant List, YaoZh website (https://db.yaozh.com/). The selection criteria of this article were: 1) Research involves the botany, toxicity and adverse reactions, and the traditional application of C. trichotomum; 2) research involves the preparation of crude extract and the separation and identification of monomer compounds; 3) research involves the pharmacological activity of the crude extracts and isolated compounds; 4) research involves the mechanism of action and so on. Keywords used in the literature search were “C. trichotomum,” “海州常山,” “phytochemistry,” “chemical constituents,” “pharmacology,” “biological activity,” “traditional uses,” “medicinal uses,” “toxicology,” “safety,” and other related search terms. We searched all eligible literature up to July 2024, with no time and language restrictions. The sources of the literature database were shown in Figure 2. The chemical structures of these compounds isolated from C. trichotomum were drawn using the software ChemDraw 22.

FIGURE 2

Statistical map of literature database sources.

3 Botanical description

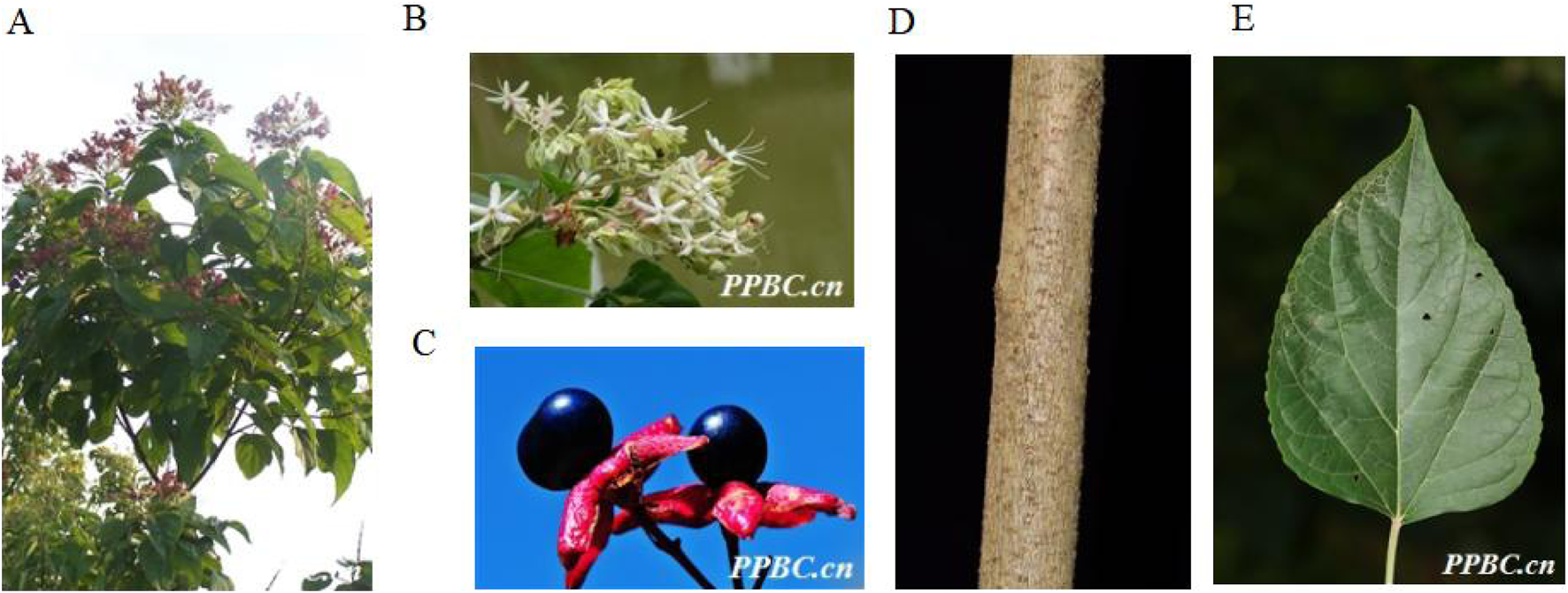

C. trichotomum is a deciduous shrub or tree that belongs to genus Clerodendrum family Verbenaceae, 1.5–10 m tall (Figure 3). The branchlets are lenticellate. The leaves of the plant are ovate-elliptic, triangular-ovate or ovate, with a size of around 5–16 cm × 2–13 cm. Their base is broadly cuneate, truncate, or rarely cordate, margin is entire or rarely undulate, apex is acuminate. The leaf blade is greenish abaxially and dark green adaxially. The veins are 3–5 pairs and the petiole is 2–8 cm long. The inflorescences are axillary or terminal, lax, corymbose cymes, dichotomous. The length of inflorescence is 8 and 18 cm and the peduncle is 3–6 cm long. The bracts are elliptic and the flowers are fragrant. The calyx is greenish firstly, then becoming purple, deeply 5-lobed; the lobes are triangular-lanceolate to ovate. The corolla is white or pinkish, with about 2 cm long, its tube is slender; its lobes are oblong, with the size of around 5–10 mm × 3–5 mm. The style is shorter than stamens, both exserted. The drupes are blue-purple, subglobose, ca. 6–8 mm in diam (Peng and Chen, 1982; Chen and Michael, 1994).

FIGURE 3

The aerial parts (A), Plant flowers (B), Plant fruits (C), Plant stems (D) and Plant leaves (E) of Clerodendrum trichotomum Thunb (http://ppbc.iplant.cn/).

4 Toxicity and adverse reactions

Limited toxicity research on C. trichotomum has been conducted in the literature, although C. trichotomum leaves and stems have been used as a medicine in different populations. The median lethal dose (LD50) of C. trichotomum water extract in mice was 20.6 g/kg by intraperitoneal injection (Yan et al., 1957). Rats were given 150 g/kg hot water (80°C) maceration extract by intragastric administration, and no animal death was observed within 72 h; The LD50 for intravenous injection was 19.4 g/kg (Xu and Xing, 1962). Mice were intraperitoneally injected with clerodendronin A (an active compound of C. trichotomum), the LD50 was 1.84 g/kg (equivalent to crude drug 370 g/kg); Intraperitoneally injected mice with clerodendronin B (another active compound of C. trichotomum), the LD50 was 3.21 g/kg (equivalent to crude drug 550 g/kg) (Xu et al., 1960a). The rats were given 0.25 g/(kg·d) and 2.5 g/(kg·d) hot water (80°C) maceration extract of C. trichotomum by intragastric administration for 60 days, separately, no abnormal changes were observed in growth, blood, urine and pathology except for quiet, reduced activity and loose stool in a few animals (Xu and Xing, 1962). When dogs were given 10 g/(kg·d) for 3 consecutive weeks, there were no significant effects on liver function, blood image, electrocardiogram and pathological examination of heart, liver and kidney, but the dose above 20 g/kg could induce vomiting (Wang et al., 1960).

5 Phytochemical investigation

The roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits of C. trichotomum can be used as medicinal parts. 164 phytochemicals have been reported in the roots and aerial parts of C. trichotomum (Table 2). Most of these studies were focused on leaves, stems, roots and fruits, while few papers have been done on the flowers so far. The prime objective behind the phytochemical identification in C. trichotomum was the discovery of phytochemicals responsible for the reported biological activities. Hence, in several studies, further biological properties were also analyzed after the phytochemical studies. Various important phytochemicals discovered in these studies may explain the reported biological properties of C. trichotomum. Among 164 secondary metabolites, there were 74 terpenoids (including 4 monoterpenes, 3 sesquiterpenes, 51 diterpenes and 16 triterpenes), 11 flavonoids, 16 steroids, 24 phenylpropanoids, 3 phenylethanosides, 2 phenolic glycosides, 3 anthraquinones, 2 polyketones, 7 cyclohexylethanoids, 7 alkaloids, 2 acid amides, and 13 other compounds (including 3 acids, 3 alcohols, 3 aldehydes, 2 esters, 1 alkane and 1 peroxide). In addition, the volatile oils from different parts of C. trichotomum also have been analyzed and reported.

TABLE 2

| No. | Compound name | Part of plant | Fraction | Type of extract | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monoterpenes | |||||

| 1 | Loliolide | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 2 | Melittoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 3 | 8-Epiloganic acid | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 4 | Neohancoside A | Flowers | EtOAc | MeOH | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Sesquiterpenes | |||||

| 5 | Clovane-2β,9α-diol | Leaves | n-BuOH | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 6 | Annuionone D | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 7 | Corchoionoside C | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Diterpenes | |||||

| 8 | Ferruginol | Stems | PE | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| 9 | Cyrtophyllone B | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 10 | Sugiol | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 11 | (4S,5S,10S)-12-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)oxy-11-hydroxyabieta-8,11,13-triene-19-oic acid β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyl ester | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 12 | Trichotomside B | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 13 | Villosin A | Stems | PE | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| 14 | Villosin B | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014b) |

| 15 | Villosin C | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014b) | ||

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |||

| 16 | 6-Methoxyvillosin C | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 17 | 18-Hydroxy-6-methoxyvillosin C | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 18 | (10R,16S)-12,16-epoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-6-methoxy17 (15→16)-abeo-abieta-5,8,11,13-tetraene-3,7-dione | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 19 | Teuvinceone A | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 20 | Teuvinceone B | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| 21 | 12,16-Epoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-6-methoxy-17 (15→16)-abeo-abieta-5,8,11,13, 15-pentaene-3,7-dione | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 22 | Teuvinceone H | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 23 | 15,16-Dehydroteuvincenone G | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 24 | 3-Dihydroteuvincenone G | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 25 | 17-Hydroxymandarone B | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 26 | Uncinatone | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |||

| Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| 27 | Mandarone E | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 28 | Formidiol | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 29 | Teuvincenone E | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |||

| 30 | Teuvincenone F | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |||

| Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| 31 | (10R,16S)-12,16-Epoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-18-oxo-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,11,13-pentaene-7-one | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 32 | (10R,16R)-12,16-Epoxy11,14,17-trihydroxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,11,13-pentaene-2,7-dione | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 33 | 15,16-Dihydroformidiol | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 34 | 18-Hydroxyteuvincenone E | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 35 | 2α-Hydrocaryopincaolide F | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 36 | 15α-Hydroxyuncinatone | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 37 | 15α-Hydroxyteuvincenone E | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 38 | Trichotomin B | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 39 | Trichotomside A | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH. | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 40 | Szemaoenoid A | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 41 | 3,12-O-β-D-Diglucopyranosyl-11,16-dihydroxyabieta-8,11,13-triene | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| 42 | Leucasinoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 43 | (3S,5S,10S,15S)-3β-[β-D-Glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]oxy-12-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)oxyabieta-8,11,13-triene-11,16-diol | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| 44 | (3S,4R,10R,16S)-3,4:12,16-Diepoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-5,8,11,13-tetraene-7-one | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 45 | 12,16-Epoxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,12,15-pentaene7,11,14-trione | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 46 | Trichotomin A | Roots | CH2Cl2 | 95% EtOH | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 47 | Clerodendrin A | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:2, v/v) | Nishida et al. (1989) | |

| 48 | Clerodendrin B | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:2, v/v) | Nishida et al. (1989) | |

| 49 | Clerodendrin D | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:2, v/v) | Nishida et al. (1989) | |

| 50 | Clerodendrin E | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:1, v/v) | Kawai et al. (1998) | |

| 51 | Clerodendrin F | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:1, v/v) | Kawai et al. (1998) | |

| 52 | Clerodendrin G | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:1, v/v) | Kawai et al. (1998) | |

| 53 | Clerodendrin H | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:1, v/v) | Kawai et al. (1998) | |

| 54 | Clerodendrin I | Leaves | Hexane/Acetone (1:1, v/v) | Kawai et al. (1999) | |

| 55 | (2R,3S,4R,5R,6S,9R,10R,11S,13S,16R)-6,19-Diacetoxy-3-[(2R)-2-acetoxy-2-methylbutyryloxy]-4,18:11,16:15,16-triepoxy-15-methoxy7-clerodene-2-ol | Leaves | MeOH | Ono et al. (2013) | |

| 56 | Phytol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) | ||

| 57 | Viridiol B | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 58 | Trichotomone | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Wang et al. (2013b) | |

| Triterpenes | |||||

| 59 | Friedelin | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) |

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) | ||

| 60 | Glutinol | Stems | PE | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| 61 | 3β-hydroxy-30-norlupan-20-one | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 62 | Platanic acid | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| 63 | Lupeol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) | ||

| 64 | Betulinic acid | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) | ||

| 65 | Taraxerol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) |

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) | ||

| 66 | Oleanolic acid | Fruits | PE | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| 67 | 3-O-Acetyl oleanolic aldehyde | Stems | PE | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| 68 | Ursolic aldehyde | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) | ||

| 69 | Ursolic acid | Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) |

| 70 | β-Amyrin | Stems | CH2Cl2 | MeOH | Choi et al. (2012) |

| 71 | Oleanolic aldehyde | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 72 | Maslinic acid | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 73 | Corosolic acid | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 74 | Trijugaoside A | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022a) |

| Flavonoids | |||||

| 75 | Apigenin | Leaves | PE | 90%EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| Leaves | EtOAc | Water | Yao and Guo (2010) | ||

| Leaves and twigs | PE | 95% EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) | ||

| 76 | Luteolin | Leaves | PE | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| 77 | Chrysoeriol | Leaves | EtOAc | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| 78 | Acacetin | Leaves | MeOH | Ono et al. (2013) | |

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) | ||

| 79 | 5,7-Dihydroxy3′,4′-dimethoxyflavone | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| 80 | Clerodendroside | Leaves | n-BuOH | MeOH | Morita et al. (1977) |

| 81 | Apigenin-7-galacturonide | Leaves | MeOH | Ono et al. (2013) | |

| 82 | Clerodendrin | Leaves | Calcium ion precipitates after water extraction | Zeng et al. (1963) | |

| Chen et al. (1988) | |||||

| 83 | Acacetin-7-β-D-glucurono-β-(1→2)-D-glucuronide | Leaves | — | Okigawa et al. (1970) | |

| 84 | Apigenin 7-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside | Leaves | — | Min et al. (2005) | |

| 85 | Apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucuronide buthyl ester | Leaves and twigs | n-BuOH | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Steroids | |||||

| 86 | β-Sitosterol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) |

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) | ||

| Fruits | PE | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) | ||

| Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) | ||

| 87 | Daucosterol | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| Leaves and twigs | EtOAc | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) | ||

| 88 | Stigmasterol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) |

| Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) | ||

| Fruits | PE | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) | ||

| 89 | Stigmasterol-3-O-glucopyranoside | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| 90 | 3-O-β-D-Galactopyranosyl-(24β)-ethylcholesta-5, 22, 25-trien | Leaves | EtOAc | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| 91 | 24-Ethyl-7-oxocholesta-5, 22(E), 25-trien-3β-ol | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Yang et al. (2014) | |

| 92 | Decortinone | Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Yang et al. (2014) | |

| 93 | 22-Dehydroclerosterol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) |

| Fruits | PE | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) | ||

| Stems | CH2Cl2 | MeOH | Choi et al. (2012) | ||

| Leaves | PE | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) | ||

| Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Yang et al. (2014) | |||

| 94 | Clerosterol | Leaves | MeOH | Ono et al. (2013) | |

| Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) | ||

| Roots | PE/EtOAc (1:1, v/v) | Yang et al. (2014) | |||

| 95 | (22E,24R)-Stigmasta-4,22,25-trien-3-one | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| 96 | (20R,22E,24R)-6β-Hydroxy-stigmasta-4,22,25-trien-3-one | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| 97 | (20R,22E,24R)-3β-Hydroxy-stigmasta-5,22,25-trien-7-one | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| 98 | (20R,22E,24R)-Stigmasta-5,22,25-trien-3β,7β-diol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| 99 | (20R,22E,24R)-Stigmasta-22,25-dien-3,6-dione | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| 100 | (20R,22E,24R)-Stigmasta-22,25-dien-3β,6β,9α-triol | Leaves | EtOAc | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| 101 | 22-Dehydroclerosterol 3β-O-β-D-(6′-O-margaroyl)-glucopyranoside | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2013) |

| Phenylpropanoids | |||||

| 102 | Acteoside (Verbascoside) | Flowers | EtOAc | MeOH | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Leaves | MeOH | Ono et al. (2013) | |||

| Leaves and twigs | n-BuOH | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kang et al. (2003) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) | ||

| Leaves | Water | 70% MeOH | Lee J. Y. et al. (2011) | ||

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) | ||

| Leaves | Water | 70% MeOH | Kim et al. (2009) | ||

| 103 | Martynoside | Flowers | EtOAc | MeOH | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| Leaves and twigs | n-BuOH | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kang et al. (2003) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) | ||

| 104 | Leucosceptoside A | Flowers | EtOAc | MeOH | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kang et al. (2003) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) | ||

| 105 | Jionoside D | Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) |

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Chae et al. (2004) | ||

| 106 | 2″-Acetylmartynoside | Stems | CH2Cl2 | MeOH | Chae et al. (2007) |

| 107 | 3″-Acetylmartynoside | Stems | CH2Cl2 | MeOH | Chae et al. (2007) |

| 108 | Isoacteoside (Isoverbascoside) | Flowers | EtOAc | MeOH | Lee et al. (2016) |

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kang et al. (2003) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) | ||

| Leaves | Water | 70% MeOH | Kim et al. (2009) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Chae et al. (2005) | ||

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) | ||

| 109 | Isomartynoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kang et al. (2003) | ||

| Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) | ||

| 110 | Plantainoside C | Stems | EtOAc | MeOH | Kim et al. (2001) |

| 111 | p-Hydroxyphenethyl-trans-ferulate | Fruits | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| 112 | Syringaresinol | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 113 | Syringaresinol-4ʹ-O-β-glucopyranoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 114 | Cistanoside F | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 115 | Glypentoside C | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 116 | Cannabisin E | Fruits | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| 117 | Cannabisin F | Fruits | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| 118 | Grossamide | Fruits | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| 119 | N-p-Coumaryltyramine | Fruits | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| 120 | Spicatolignan B | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 121 | Lyoniresinol | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| 122 | Lyonirenisol-3α-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| 123 | Ecdysanols D | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Gao et al. (2022) |

| 124 | Ecdysanols E | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Gao et al. (2022) |

| 125 | Trichotomoside | Stems | CH2Cl2 | MeOH | Chae et al. (2006) |

| Phenylethanosides | |||||

| 126 | Decaffeoylverbascoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Leaves | Water | 70% MeOH | Kim et al. (2009) | ||

| 127 | 2-(4-Hydroxyphenyl) ethanol-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 128 | Deacylisomartynoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Zhang et al. (2022) |

| Phenolic glycosides | |||||

| 129 | 3,4-Dimethoxyphenyl-1-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl (1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| 130 | 2,6-Dimethoxy-4-hydroxy-1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside | Stems | n-BuOH | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2022b) |

| Anthraquinones | |||||

| 131 | Aloe-emodin | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 132 | Emodin | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| 133 | Chrysophanol | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2014a) |

| Polyketones | |||||

| 134 | Clerodendruketone A | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Gao et al. (2022) |

| 135 | Clerodendruketone B | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Gao et al. (2022) |

| Cyclohexylethanoids | |||||

| 136 | Rengyolone | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 137 | 5-O-Butyl cleroindin D | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 138 | Cleroindin C | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 139 | 1-Hydroxy-1-(8-palmitoyloxyethyl) cyclohexanone | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 140 | Cleroindin B | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 141 | Rengyol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| 142 | Isorengyol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2014) |

| Alkaloids | |||||

| 143 | Trichotomine | Fruits | EtOH | Iwadare et al. (1974) | |

| 144 | Trichotomine G1 | Fruits | EtOH | Iwadare et al. (1974) | |

| 145 | 1H-Indole-3-carboxylic acid | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Hu et al. (2014) |

| 146 | Orixine | — | Xu and Xing (1962) | ||

| 147 | Orixidine | — | Xu and Xing (1962) | ||

| 148 | Iso-orixine | — | Xu and Xing (1962) | ||

| 149 | 1H-Imidazole-4-carboxylate | Fruits | PE | 95%EtOH | Wang et al. (2021) |

| Acid amides | |||||

| 150 | (2S,3S,4R,E)- 2-[(2′R)- 2′-Hydroxyl-octacosane amino-23-hexacosane-1,3,4-triol | Leaves | EtOAc | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| 151 | Aurantiamide acetate | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Acids | |||||

| 152 | Palmitic acid | Fruits | PE | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

| Leaves | PE | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) | ||

| Leaves | PE | Water | Yao and Guo (2010) | ||

| 153 | (2S,3S,4R,23E)-2-[(2′R)-2′-hydroxyl-octacosane amino]-hexacosane-1,3,4-triol | Leaves | PE | Water | Yao and Guo (2010) |

| 154 | Corchorifalty acid E | Leaves and twigs | EtOAc | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Alcohols | |||||

| 155 | n-Decanol | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| 156 | n-Heptadecanol | Leaves | PE | 90%EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| 157 | α-Tocopherol | Leaves | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Aldehydes | |||||

| 158 | Isovanillin | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| 159 | Syringaldehyde | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| 160 | 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Esters | |||||

| 161 | Dibutyl phthalate | Stems | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Li et al. (2019) |

| 162 | Monopalmitin | Leaves and twigs | PE | 95%EtOH | Xu et al. (2015) |

| Alkane | |||||

| 163 | n-Pentatriacontane | Leaves | EtOAc | 90% EtOH | Tian (2017) |

| Peroxide | |||||

| 164 | Bungein A | Fruits | EtOAc | 85%EtOH | Liu et al. (2020) |

Compounds isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

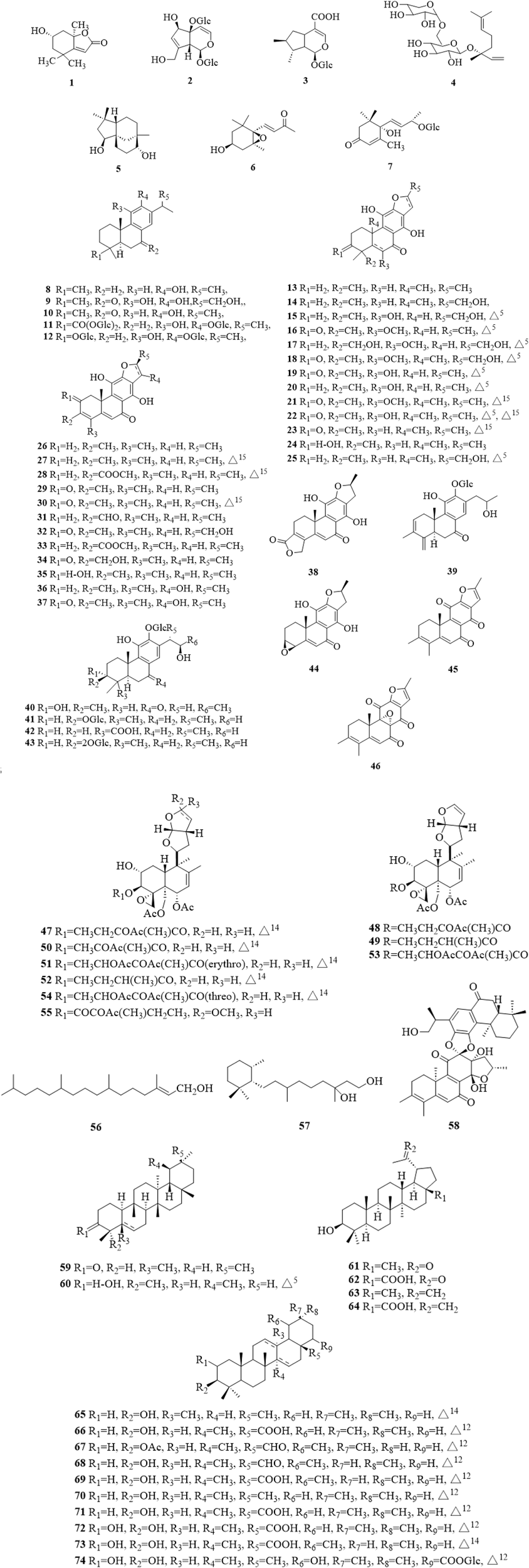

5.1 Terpenoids

Terpenoids are the most commonly reported types of compounds isolated from C. trichotomum, with a total of 74 compounds (Figure 4), including monoterpenes (1–4) (Nagao et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2016; Li et al., 2022a), sesquiterpenes (5–7) (Xu et al., 2015), diterpenes (8–58) and triterpenoids (59–74) (Choi et al., 2012; Hu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015; Li et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022a; Zhang et al., 2022). Among the diterpenes, there were 39 abietane-type diterpenes (8–46) (Wang et al., 2013a; Li et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2014b; Xu et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022a; Li et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2022), 9 clerodane-type diterpene (47–55) (Nishida et al., 1989; Kawai et al., 1998; Kawai et al., 1999; Ono et al., 2013), a chained diterpene (56) (Hu et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2015), a monocyclic diterpene (57) (Xu et al., 2015) and a dimeric diterpene (58) (Wang et al., 2013b). Abietane-type diterpenes are also the most abundant of all isolated secondary metabolites. Due to the limitation of science and technology at that time, there were some errors in some literatures. Li et al. discovered and revised the NMR data and chemical system names of some compounds in the literatures (Li et al., 2022a; Li et al., 2014b).

FIGURE 4

The chemical structure of terpenoids 1–74 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

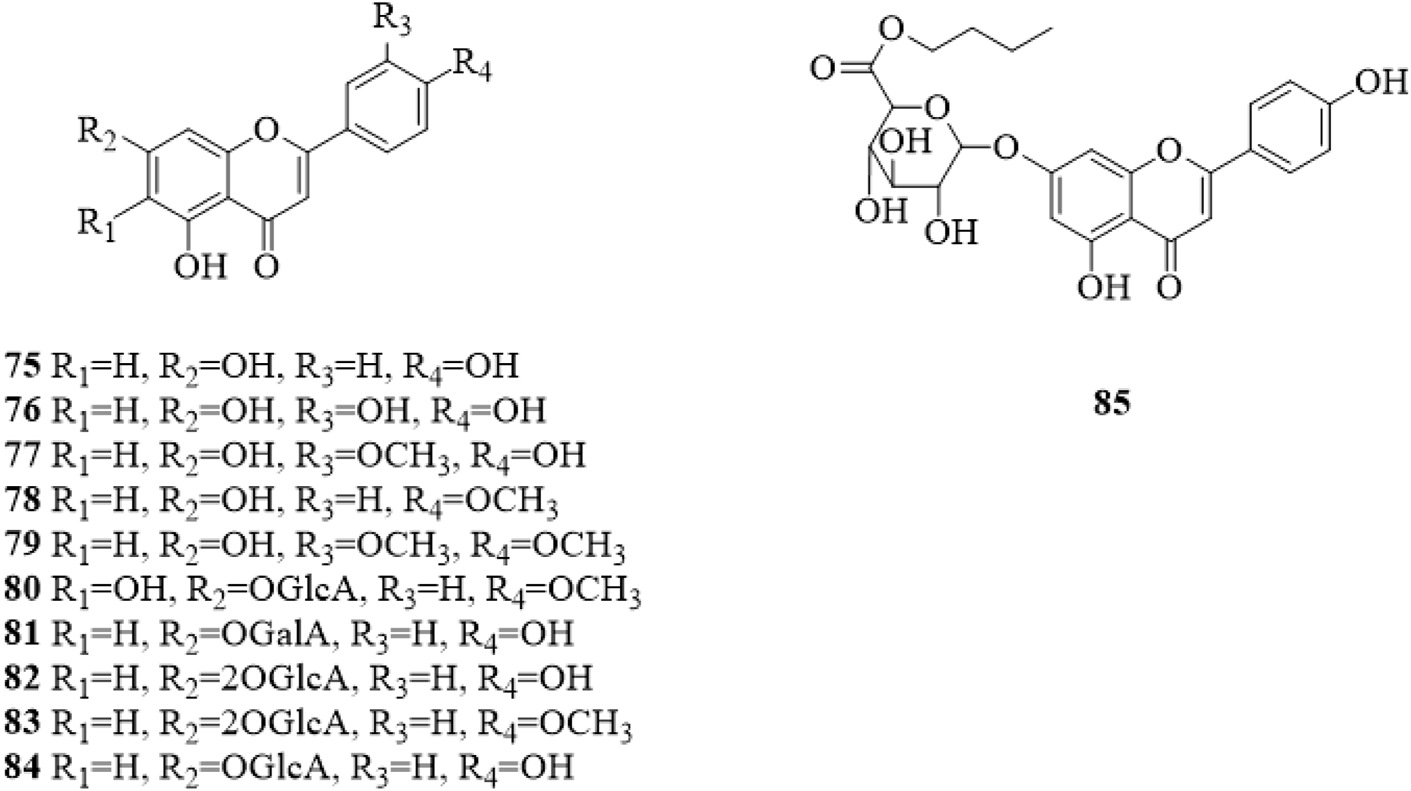

5.2 Flavonoids

Flavonoids are mainly found in the leaves of C. trichotomum. Up to now, only 11 flavonoids (75–85, Figure 5) (Zeng et al., 1963; Okigawa et al., 1970; Morita et al., 1977; Chen et al., 1988; Min et al., 2005; Yao and Guo, 2010; Ono et al., 2013; Xu and Shi, 2015; Tian, 2017; Li et al., 2019) have been isolated from C. trichotomum. The only difference is the substituents in the 6, 7, 3′ and 4′ positions of the flavonoid, the linked sugar group is mostly glucuronic acid (GlcA).

FIGURE 5

The chemical structure of flavonoids 75–85 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

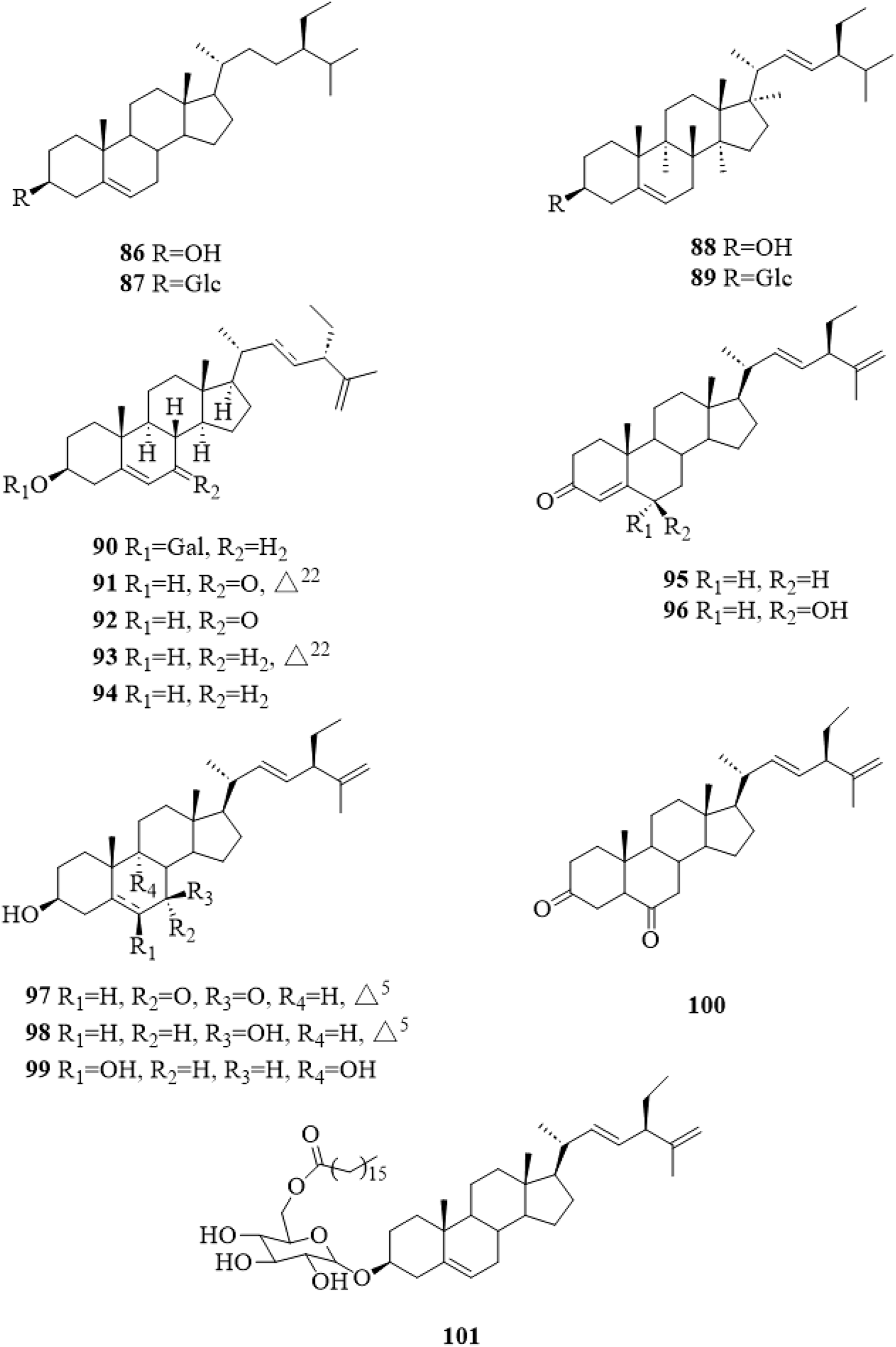

5.3 Steroids

There were 16 steroid compounds (86–101, Figure 6) (Choi et al., 2012; Ono et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2014; Xu and Shi, 2015; Tian, 2017; Li et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020) isolated from C. trichotomum. Interestingly, there are nine steroids with a side chain of C10H17 and two double bonds at C-22 and C-25.

FIGURE 6

The chemical structure of steroids 86–101 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

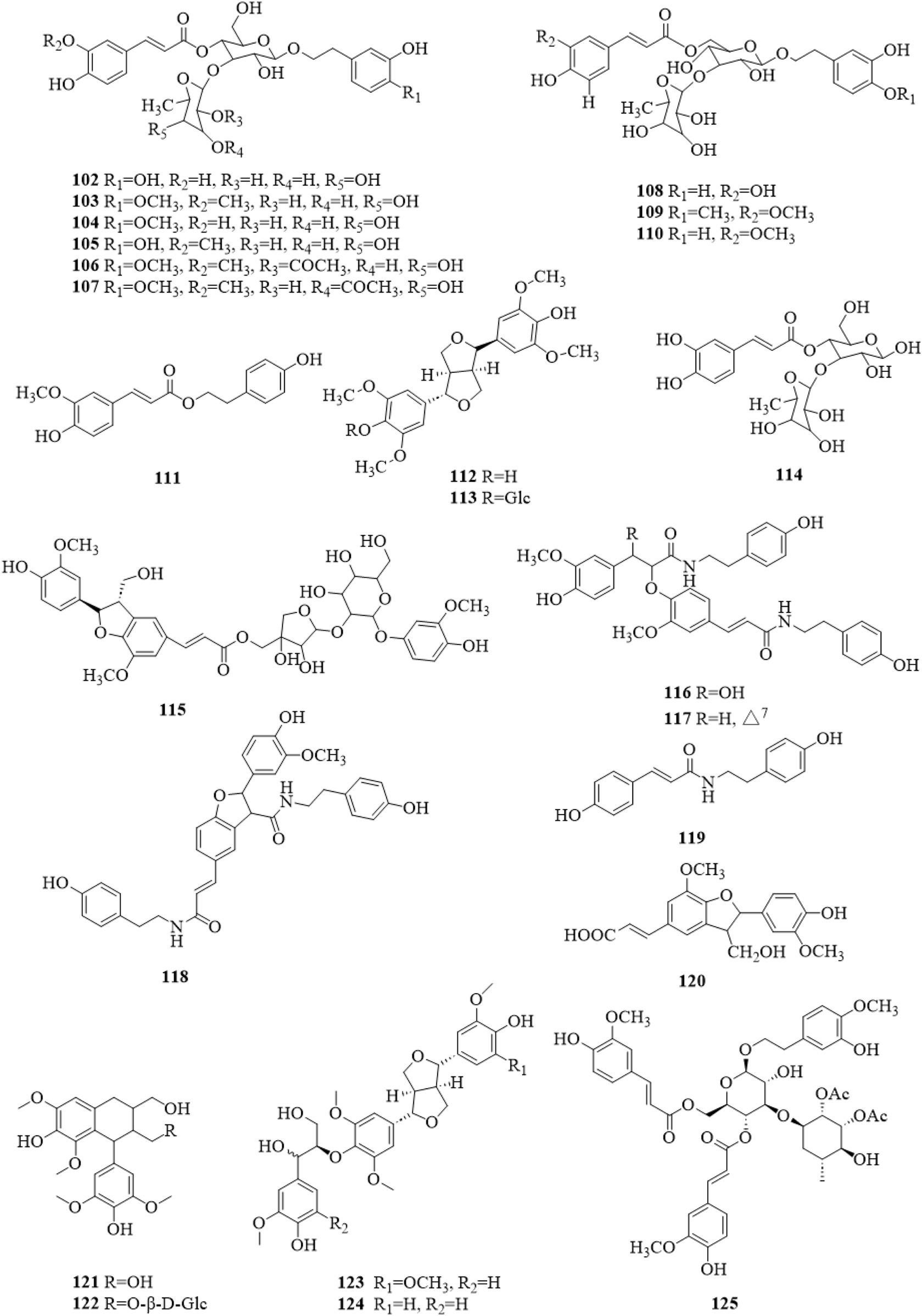

5.4 Phenylpropanoids

There were 24 phenylpropanoid compounds (102–125, Figure 7) reported in the literature (Kim et al., 2001; Kang et al., 2003; Chae et al., 2004; Chae et al., 2005; Chae et al., 2006; Chae et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2009; Lee D. G. et al., 2011; Ono et al., 2013; Li et al., 2014a; Xu and Shi, 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020; Gao et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022b; Zhang et al., 2022). The isolated phenylpropanoids were second only to terpenoids in quantity. They are more polar, mostly in the form of glycosides, and often contain caffeoyl groups in the molecule.

FIGURE 7

The chemical structure of phenylpropanoids 102–125 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

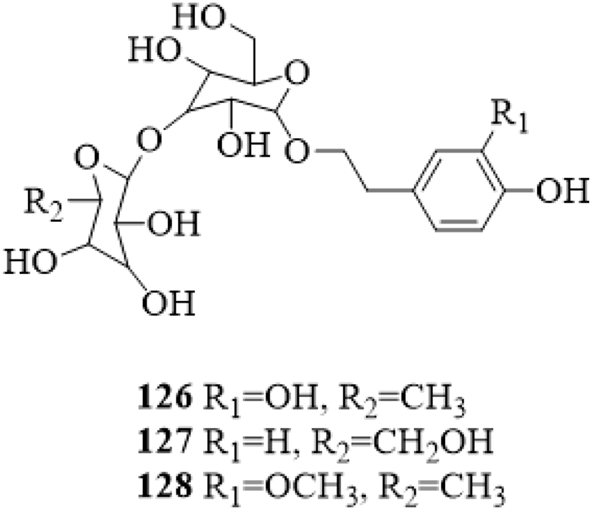

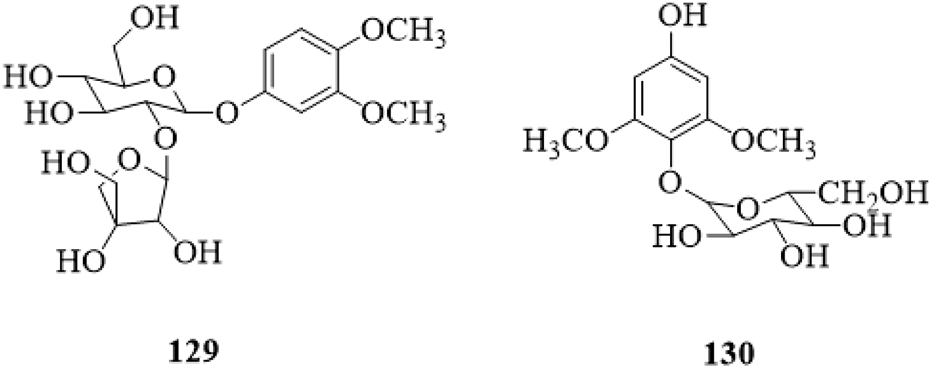

5.5 Phenylethanosides

Three phenylethanosides, decaffeoylverbascoside (126), 2-(4-hydroxyphenyl) ethanol-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (127) and deacylisomartynoside (128) were isolated from the stems of C. trichotomum (Zhang et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022b). Compound 126 was also yielded from the leaves (Kim et al., 2009). The structure of compounds 126–128 is shown in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8

The chemical structure of phenylethanosides 126–128 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

5.6 Phenolic glycosides

3,4-dimethoxyphenyl-1-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl (1→2)-β-D-glucopyranoside (129) and 2,6-dimethoxy-4-hydroxy-1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (130) have been isolated from the stems, and both of them are phenolic glycosides (Li et al., 2022b). The structures are shown in Figure 9.

FIGURE 9

|The chemical structure of phenolic glycosides 129,130 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

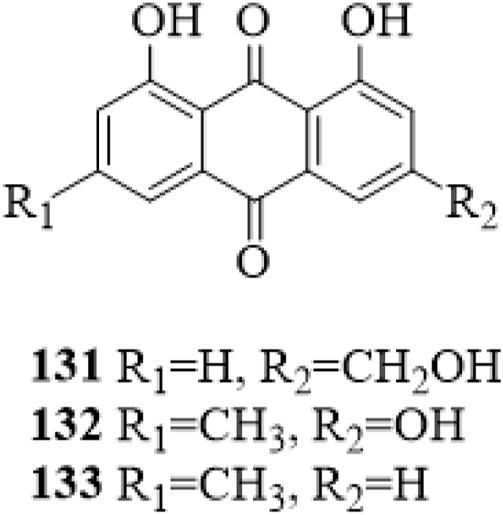

5.7 Anthraquinones

Three anthraquinones (131–133, Figure 10) were isolated from the stems of C. trichotomum (Li et al., 2014a). They were reported from the genus Clerodendrum for the first time.

FIGURE 10

The chemical structure of anthraquinones 131–133 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

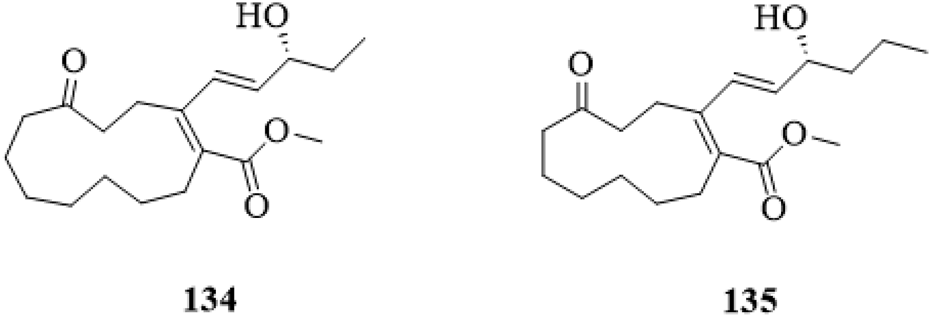

5.8 Polyketones

Two polyketones (Figure 11), Clerodendruketone A (134) and Clerodendruketone B (135), from the leaves and twigs of C. trichotomum were reported (Gao et al., 2022).

FIGURE 11

The chemical structure of polyketones 134,135 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

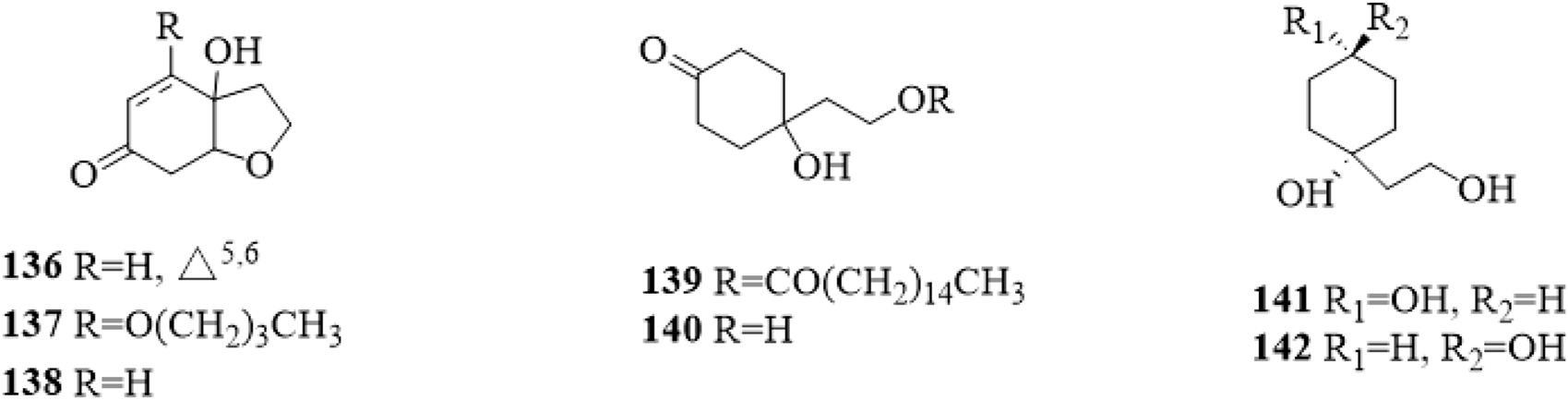

5.9 Cyclohexylethanoids

Cyclohexylethanoids are rarely isolated from C. trichotomum. In 2014, 7 cyclohexylethanoids (Figure 12), including rengyolone (136), 5-O-butyl cleroindin D (137), cleroindin C (138), 1-hydroxy-1-(8-palmitoyloxyethyl) cyclohexanone (139), cleroindin B (140), rengyol (141) and isorengyol (142), were isolated from the leaves and reported (Xu et al., 2014).

FIGURE 12

The chemical structure of cyclohexylethanoids 136–142 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

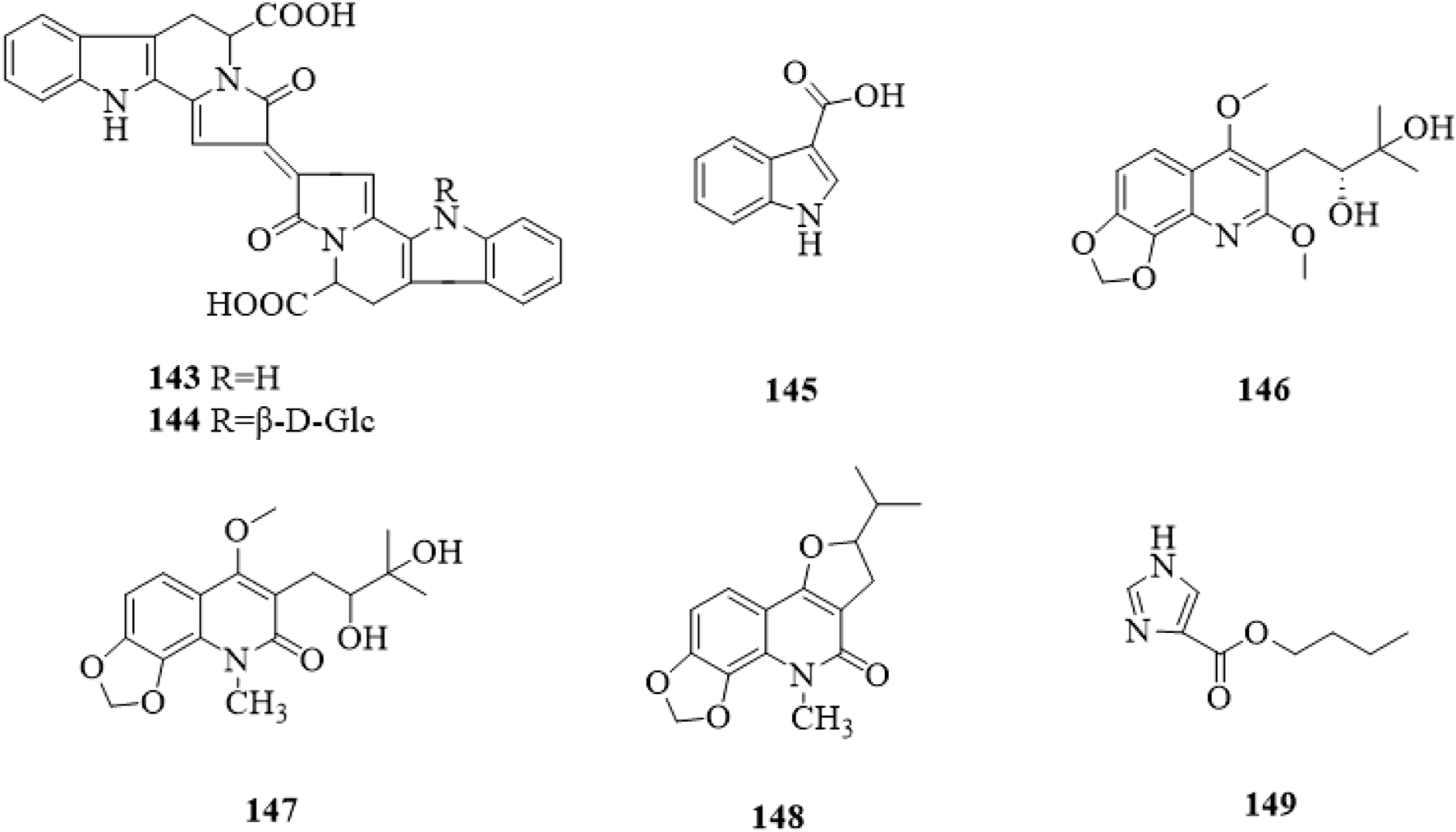

5.10 Alkaloids

So far, a total of 8 alkaloids (143–149, Figure 13) have been found from C. trichotomum. In the 1960s, Xu et al. isolated three quinoline alkaloids (Xu and Xing, 1962), namely, orixine (146), orixidine (147) and iso-orixine (148). Then, 1H-indole-3-carboxylic acid (145) (Hu et al., 2014), trichotomine (143) and trichotomine G1 (144) (Iwadare et al., 1974) have been discovered, which were all indole alkaloids. In recent years, 1H-imidazole-4-carboxylate (149) (Wang et al., 2021) were reported, and they belong to purine and imidazole, respectively.

FIGURE 13

The chemical structure of alkaloids 143–149 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

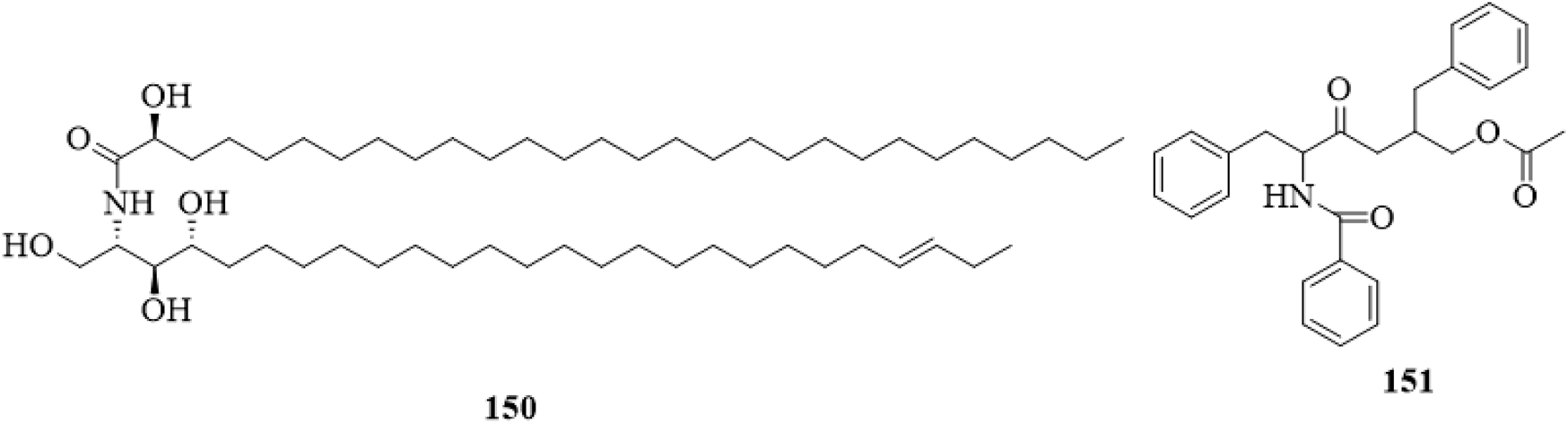

5.11 Acid amides

Two acid amides, including (2S,3S,4R,23E)-2-[(2′R)-2′-hydroxyl-octacosane amino]-hexacosane-1,3,4-triol (150) (Tian, 2017) and aurantiamide acetate (151) (Xu and Shi, 2015) have been isolated and reported. The structures of the two compounds are shown in Figure 14.

FIGURE 14

The chemical structure of acid amides 150,151 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

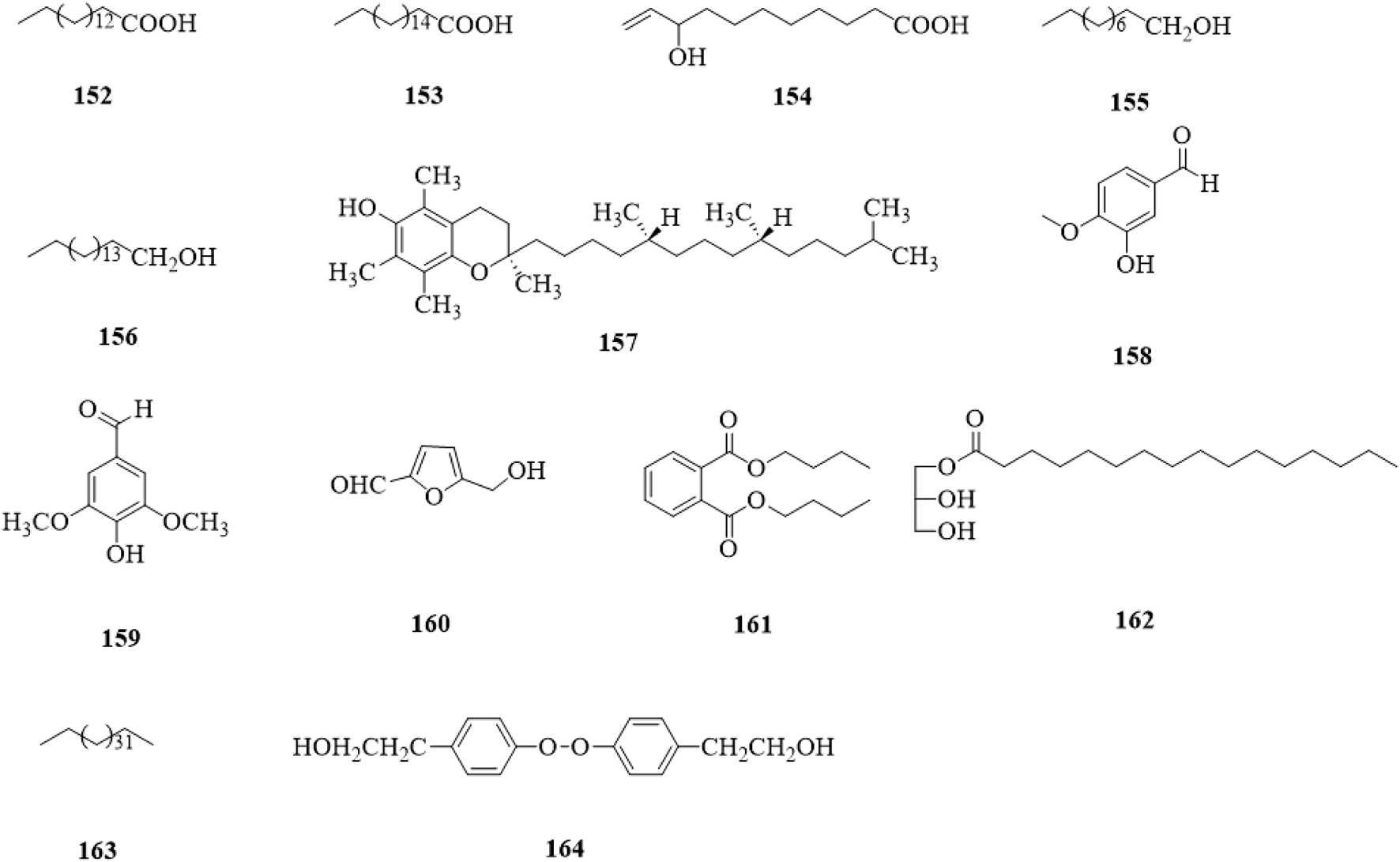

5.12 Others

Other types of compounds (152–164, Figure 15) include acids (152–154) (Yao and Guo, 2010; Xu and Shi, 2015; Tian, 2017; Liu et al., 2020), alcohols (155–157) (Xu et al., 2015; Xu and Shi, 2015; Tian, 2017), aldehydes (158–160) (Xu and Shi, 2015; Li et al., 2019), esters (161,162) (Xu and Shi, 2015; Li et al., 2019), a alkane (163) (Tian, 2017), and a peroxide (164) (Liu et al., 2020).

FIGURE 15

The chemical structure of other compounds 152–164 isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

5.13 Volatile compounds

Volatile compounds of C. trichotomum have been analyzed and reported by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and most of these studies were focused on the leaves, flowers and fruits (Table 3). Yan et al. extracted volatile oil from the leaves of C. trichotomum by steam distillation, analyzed and identified 47 compounds (Yan and Tian, 2003). Among them, (E,E,E)-9,12,15-octadecatrienoate methyl ester and (E,E,E) −9,12,15-octadecatrienol accounted for the higher content, accounting for 12.65% and 13.4% of the total components respectively. Lee et al. used GC-MS to analyse the volatile components of the leaves, and identified 50 compounds (Lee J. Y. et al., 2011), of which the main components were 2,6,10,15-tetramethylheptadecane (23.83%) and linalool (29%). The volatiles of the flowers were analyzed by headspace solid phase microextraction coupled with GC-MS (HS-SPME-GC-MS) for the first time (Tian et al., 2011). Twenty-seven compounds were identified, 2,6,10,14-tetramethylhexadecane, hexadecanal, octen-3-ol, benzaldehyde and n-hexadecanoic acid were the dominant components. Li et al. used GC-MS to analyse the volatile oil components in the fruits of C. trichotomum in 2020, and identified a total of 31 compounds (Li et al., 2020). The analysis showed that the components of volatile oil were different with different parts of plant, origin and extraction methods.

TABLE 3

| Source | Method | Chief components (≧4%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | GC-MS | (E,E,E)-9,12,15-Octadecatrien-1-ol (13.4%) (E,E,E)-9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid methyl ester (12.65%) Palmitic acid (12.51%) n-Pentadecanoic acid (7.66%) |

Yan and Tian (2003) |

| 2,6,10,15-Tetramethylheptadecane (23.83%) Linalool (29%) |

Lee D. G. et al. (2011) | ||

| Flowers | HS-SPME-GC-MS | 2,6,10,14-Tetramethylhexadecane (17.25%) Hexadecanal (10.57%) 1- Octen-3-ol (6.78%) Benzaldehyde (6.10%) n-Hexadecanoic acid (4.85%) |

Tian et al. (2011) |

| Fruits | GC-MS | Dotriacontane (7.117%) Tetratriacontane (7.111%) Hentriacontane (6.141%) Tritriacontane (5.753%) Pentatriacontane (5.107%) Triacontane (4.53%) Nonacosane (4.092%) |

Li et al. (2020) |

Volatile compounds from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

6 Pharmacological activities

C. trichotomum is widely used in the folk to nourish the liver and reduce blood pressure, dispell wind and eliminate dampness. Pharmacological studies have shown that it has a variety of pharmacological activities. In China, relevant studies mainly focus on the mechanism of reducing blood pressure, sedation and analgesia, most of which were in the 1950s and 1960s. Studies in other countries mainly concentrated in antiinflammatory, antioxidant and other mechanisms of action, with more reports in South Korea and Japan, and most of the studies were carried out in the 21st century. The chemical constituents isolated from the C. trichotomum have abundant pharmacological activities, the most important ones are antihypertensive, antitumour, antioxidant, antiinflammatory, antibacterial, sedative and analgesic. The pharmacological activities of all the compounds are shown in Table 4.

TABLE 4

| Activities | Compounds /Extracts |

Types | Testing subjects | Dose/Duration | Controls | Effects/Mechanisms | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-hypertensive activity | |||||||

| Water extracts | In vivo | Rats/dogs | 50–100 mg/kg for 2 weeks | NM | Showed hypotensive effect on anesthetized or awake rats and dogs, renal hypertensive rats and dogs | Xu and Xing (1962) | |

| In vivo | Rats/dogs | Rats: 2.5 mL/100 g for 3 h; Dogs: 0.2 g/kg for 30 min | NM | The antihypertensive effects are closely related to the central nervous and endovascular receptors. | Xu and Peng (1960) | ||

| In vivo | Dogs/rats/cats /rabbits |

Dogs/rabbits/cats: 0.5–1 g/kg; Rats: 25 g/kg, 10 g/kg | NM | The mechanism of antihypertensive action is related to the direct dilation of blood vessels and the blocking of ganglia. | Xu (1962) | ||

| In vivo | Rats/dogs | Rats: 0.1 g/kg 0.5 g/kg; Dogs: 0.24 g/kg |

NM | Reduces blood pressure by increasing renal blood flow and promoting urinary water and sodium excretion. | Lu et al. (1994) | ||

| Acteoside (102) | In vitro | ACE inhibitory activity | 10 μL for 15 min | NM | IC50 value was 373.3 ± 9.3 μg/mL | Kang et al. (2003) | |

| Martynoside (103) | In vitro | ACE inhibitory activity | 10 μL for 15 min | NM | IC50 value was 524.4 ± 28.1 μg/mL | Kang et al. (2003) | |

| leucosceptoside A (104) | In vitro | ACE inhibitory activity | 10 μL for 15 min | NM | IC50 value was 423.7 ± 18.8 μg/mL | Kang et al. (2003) | |

| Isoacteoside (108) | In vitro | ACE inhibitory activity | 10 μL for 15 min | NM | IC50 value was 376.0 ± 15.6 μg/mL | Kang et al. (2003) | |

| Isomartynoside (109) | In vitro | ACE inhibitory activity | 10 μL for 15 min | NM | IC50 value was 505.9 ± 26.7 μg/mL | Kang et al. (2003) | |

| Clerodendroside (82) | In vivo | Rats | 50 mg/kg | NM | Have a hypotensive effect on anaesthetised rats | Morita et al. (1977) | |

| Antitumour activity | |||||||

| Cyrtophyllone B (9) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (A549, HepG-2, MCF-7 and 4T1) | 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, 5, 15, 50 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were 14.96, 15.00, >50, and 35.46 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2014b) | |

| Villosin B (14) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (A549, HepG-2, MCF-7 and 4T1) | 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, 5, 15, 50 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were 15.00, 29.74, >50, and >50 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2014b) | |

| Villosin C (15) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (A549, HepG-2, MCF-7 and 4T1) | 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, 5, 15, 50 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were 14.93, 31.35, >50, and >50 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2014b) | |

| In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (K562, MCF-7, A549 and HepG2) | 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were 28.41, >100, >100 and 31.35 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| Teuvincenone A (19) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (A549, HepG-2, MCF-7, 4T1) | 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, 5, 15, 50 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were >50, >50, 25.00, and 17.83 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2014b) | |

| Teuvincenone B (20) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (K562, MCF-7, A549 and HepG2) | 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were >100, 43.18, >100, and 29.74 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2022b) | |

| Uncinatone (26) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (A549, HepG-2, MCF-7 and 4T1) | 0.15, 0.5, 1.5, 5, 15, 50 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were >50, 12.50, >50, and 8.79 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2014b) | |

| In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (K562, MCF-7, A549 and HepG2) | 0, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64 μM for 2 d | Doxorubicin | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were >100, 25.00, 22.34, and 12.50 μM, respectively | Li et al. (2022b) | ||

| In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | 72 h | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 5 tumor cells were 26.47, 43.88, 19.90, 32.94 and 17.95 μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013a) | ||

| Mandarone E (27) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | 72 h | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 5 tumor cells were 31.95, 50.99, 16.05, 32.69 and 16.83 μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| Teuvincenone E (29) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | 72 h | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 5 tumor cells were 3.95, 5.37, 1.18, 1.27 and 0.83μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| (10R,16S)-12,16-Epoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-18-oxo-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,11,13-pentaene-7-one (31) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | 72 h | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 5 tumor cells were 15.72, 29.33, 7.50, 10.39 and 8.58 μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| (3S,4R,10R,16S)-3,4:12,16-Diepoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-5,8,11,13-tetraene-7-one (44) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | 72 h | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 5 tumor cells were 8.02, 12.60, 5.45, 7.01 and 3.49μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| 12,16-Epoxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,12,15-pentaene7,11,14-trione (45) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | 72 h | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 5 tumor cells were 19.48, 29.41, 12.26, 28.19 and 18.10 μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013a) | |

| Trichotomone (58) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97 and Jurkat) | NM | Staurosporine | IC50 values against 4 tumor cells were 9.80, 19.38, 9.42, 7.51 μM, respectively | Wang et al. (2013b) | |

| (20R,22E,24R)-3β-Hydroxy-stigmasta-5,22,25-trien-7-one (97) | In vitro | HeLa cell line | 24 h | NM | IC50 value against Hela cell was 35.67 μM | Xu et al. (2014) | |

| (20R,22E,24R)-Stigmasta-5,22,25-trien-3β,7β-diol (98) | In vitro | HeLa cell line | 24 h | NM | IC50 value against Hela cell was 28.92 μM | Xu et al. (2014) | |

| Acteoside (102) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (MK-1, HeLa and B16F10) | 50 μL for 48 h | NM | GI50 values against 3 tumor cellswere 40, 66, 8 μM, respectively | Nagao et al. (2001) | |

| Isoacteoside (108) | In vitro | Human cancer cell lines (MK-1, HeLa and B16F10) | 50 μL for 48 h | NM | GI50 values against 3 tumor cells were 40, 61, 8 μM, respectively | Nagao et al. (2001) | |

| Antioxidant activity | |||||||

| Acteoside (102) | In vitro | DPPH, H2O2, O2− and NO | DPPH: 10 μL for 30 min; H2O2: 5 μL for 10 min; O2−: 10 μL for 10 min; NO: 5 μL for 150 min |

Trolox and curcumin | EC50 values were 22.2, 80.2, 23.4 μM in the scavenging of DPPH radical, H2O2 and O2 radical. | Ono et al. (2013) | |

| DPPH | 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL | L-Ascorbic acid | Scavenging effect were 92.29, 93.05, 92.61, 101.13% at 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL, respectively | Lee et al. (2016) | |||

| DPPH ROS |

DPPH: 20 µL for 30 min | DPPH: Ascorbate | DPPH scavenging effect were 9, 30, 78% at 0.1, 1, 10 μM, respectively. ROS generation were 200, 190, 150% at 1, 3, 10 μM, respectively. | Yoon et al. (2009) | |||

| Martynoside (103) | In vitro | DPPH | 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL | L-Ascorbic acid | Scavenging effect were 11.00, 38.82, 72.80, 85.66% at 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL, respectively | Lee et al. (2016) | |

| Leucosceptoside A (104) | In vitro | DPPH | 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL | L-Ascorbic acid | Scavenging effect were 35.47, 46.53, 95.95, 86.33% at 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL, respectively | Lee et al. (2016) | |

| Jionoside D (105) | In vitro | ROS DPPH |

30 min 5 h |

N-acetylcystein | Intracellular ROS scavenging activity activities were 41% (0.1 mg/mL), 62% (1 mg/mL) and 85% (10 mg/mL), respectively. DPPH radical scavenging activity was 25% at 0.1 mg/mL, 36% at 1 mg/mL, and 55% at 10 mg/mL | Chae et al. (2004) | |

| 2″-Acetylmartynoside (106) | In vitro | ROS DPPH |

ROS:10 μg/mL for 30 min; DPPH:10 μg/mL for 5 h | Negative: Glucose Positive: N-acetylcysteine |

ROS scavenging activity is 55.3% in 10 ug/mL. DPPH scavenging activity is 32.3% in 10 ug/mL | Chae et al. (2007) | |

| 3″-Acetylmartynoside (107) | In vitro | ROS DPPH |

ROS:10 μg/mL for 30 min; DPPH:10 μg/mL for 5 h | Negative: Glucose Positive: N-acetylcysteine |

ROS scavenging activity is 58.5% in 10 ug/mL. DPPH scavenging activity is 36.1% in 10 ug/mL | Chae et al. (2007) | |

| Isoacteoside (108) | In vitro | DPPH | 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL | L-Ascorbic acid | Scavenging effect were 90.94, 91.56, 91.87, 100.05% at 5, 10, 50, 100 μg/mL, respectively | Lee et al. (2016) | |

| DPPH ROS |

ROS: 0.1, 1, 10 μg/mL for 30 min; DDPH: 0.1, 1, 10 μg/mL for 5 h | N-acetylcysteine | ROS scavenging activity showed concentration dependence: 43% at 0.1 μg/mL, 68% at 1 μg/mL, and 83% at 10 μg/mL. DPPH radical scavenging activity and had significance only at 10 μg/mL. |

Chae et al. (2005) | |||

| DPPH ROS |

DPPH: 20 µL for 30 min | DPPH: Ascorbate | DPPH scavenging effect were 2, 10, 67% at 0.1, 1, 10 μM, respectively. ROS generation were 250, 230, 200% at 1, 3, 10 μM, respectively. | Yoon et al. (2009) | |||

| Ecdysanols D (123) | In vitro | DPPH | NM | Vitamin C | IC50 value was 66.07 ± 13.29 µM | Gao et al. (2022) | |

| Ecdysanols E (124) | In vitro | DPPH | NM | Vitamin C | IC50 value was 53.60 ± 6.68 µM | Gao et al. (2022) | |

| Trichotomoside (125) | In vitro | DPPH ROS |

5, 10, 20 and 40 μM for 48 h | Epigallocatechin gallate | The DPPH radical scavenging activity was 12, 20, 36, and 59% in 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM, respectively. The ROS-scavenging activity was 39, 49, 58% and 61% in 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM, respectively. | Chae et al. (2006) | |

| Apigenin 7-galacturonide (81) | In vitro | DPPH, H2O2, O2− and NO | DPPH: 10 μL for 30 min; H2O2: 5 μL for 10 min; O2−: 10 μL for 10 min; NO: 5 μL for 150 min | Trolox and curcumin | EC50 value against NO-scavenging activity was 452 μM. | Ono et al. (2013) | |

| Antiinflammatory activity | |||||||

| Methanol extracts |

In Vivo

/in vitro |

Rats, mice and Raw 264.7 cells | 1 mg/kg | Indomethacin | The anti-inflammatory activity of 60% methanol extract was higher than indomethacin, and it also inhibited the production of PGE2 in RAW 264.7 cells | Choi et al. (2004) | |

| In vitro | LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells | 0.1, 0.5, 1 mg/mL | NM | Iinhibited the expression of the pro-inflammation gene through the inhibition of NF-κB dependent pathway in RAW 264.7 cells. | Park and Kim (2007) | ||

| Villosin C (15) | In vitro | NO | NM | Aminoguanidine hydrochloride | IC50 value against NO production was 15.5 μM | Hu et al. (2018) | |

| 15,16-Dehydroteuvincenone G (23) | In vitro | NO | NM | Aminoguanidine hydrochloride | IC50 value against NO production was 6.0 μM | Hu et al. (2018) | |

| 2α-Hydrocaryopincaolide F (35) | In vitro | NO | NM | Aminoguanidine hydrochloride | IC50 value against NO production was 6.5 μM | Hu et al. (2018) | |

| 15α-Hydroxyteuvincenone E (37) | In vitro | NO | NM | Aminoguanidine hydrochloride | IC50 value against NO production was 38.6 μM | Hu et al. (2018) | |

| Trichotomin B (38) | In vitro | NO | NM | Aminoguanidine hydrochloride | IC50 value against NO production was 28.9 μM | Hu et al. (2018) | |

| Trichotomin A (46) | In vitro | NO | NM | Aminoguanidine hydrochloride | IC50 value against NO production was 10.6 μM | Hu et al. (2018) | |

| 80% Methanol | In vivo | Mice/rats | Mice: 1 mg/kg; Rats: 10 mg/kg for 4 h |

Indomethacin | The maximal inhibitory activity was 47.0% in the vascular permeability test. Inhibition rate of rat paw oedema was 59.5% at 1 h | Kim et al. (2009) | |

| Acteoside (102) | In vivo | Mice/rats | Mice: 1 mg/kg; Rats: 10 mg/kg for 4 h |

Indomethacin | The maximal inhibitory activity was 46.5% in the vascular permeability test. Inhibition rate of rat paw oedema was 63.82% at 1 h |

Kim et al. (2009) | |

| In vitro | Histamine, arachidonic acid release, PGE2, PLA2 | Histamine: 10 min; PLA2: 20 min | NM | Inhibition of histamine release induced by melittin, arachidonic acid, thapsigargin, possibly related to extracellular Ca2+ | Lee et al. (2006) | ||

| In vitro | Histamine, Phospholipase A2 | NM | NM | Inhibited protein content at a dose of 25 mg/kg, and histamine content and PLA2 activity at a dose of 50 mg/kg | Lee D. G. et al. (2011) | ||

| Apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside (84) | In vivo | Rats | 0.01–30 mg/kg | omeprazole | IC50 values were 0.2, 0.1, 0.2 mg/kg in reflux oesophagitis in rats, NSAID-induced gastritis, gastric secretion in reflux oesophagitis, respectively | Min et al. (2005) | |

| 24-Ethyl-7-oxocholesta-5,22(E),25-trien-3β-ol (91) | In vitro | HT-29 cells | 0–50 μg/mL for 24 h | Blank: IL-1β timulation alone | At 118, 59, and 30 μmol/L, the production of IL-8 was reduced to 20.8%, 40.0%, and 59.2% of the control level, respectively. | Yang et al. (2014) | |

| Antibacterial activity | |||||||

|

n-Hexane, MC, ethyl acetate And n-butanol fractions |

In vitro | S. aureus, E. coli and H. pylori | 1.7 mg/mL for 24 h | Penicillin | The n-hexane and MC fractions showed antibacterial activity against H. pylori and showed inhibition zones of 10 and 11 mm in disc assay, respectively. | Choi et al. (2012) | |

| β-Amyrin (70) | In vitro | S. aureus, E. coli and H. pylori | 3.4 mg/mL for 24 h | Penicillin | Clear inhibition zones were 12, 10, and 13 mm, respectively. | Choi et al. (2012) | |

| 22-Dehydroclerosterol (93) | In vitro | S. aureus, E. coli and H. pylori | 3.4 mg/mL for 24 h | Penicillin | Clear inhibition zones were 11, 11, and 9 mm, respectively. | Choi et al. (2012) | |

| Clerodendruketone A (134) | In vitro | E. Coli and S. aureus | 50 μg/mL | Cefalexin, Levofloxacin and Vancomycin | Bacteriostatic rates against E. coli, S. aureus were 30%–60%, 60%–80%, respectively | Gao et al. (2022) | |

| Clerodendruketone B (135) | In vitro | E. coli and S. aureus | 50 μg/mL | Cefalexin, Levofloxacin and Vancomycin | Bacteriostatic rates against E. coli and S. aureus were 30%–60% | Gao et al. (2022) | |

| Analgesic effect | |||||||

| Decoction | In vivo | Mice | 1.65, 6.6, 16.5 g/kg for 120 min | Morphine and antipyrine | The peak value appeared 20–40 min after administration, then gradually decreased, and could be maintained for 2 h | Wang and Shen (1957) | |

| Clerodendronin B | In vivo | Mice | 4, 8 mg/10 g for 2 h | Morphine | The analgesic percentage (50%–80%) was stronger than that of morphine (30%–60%) | Xu et al. (1960b) | |

| Sedative effect | |||||||

| Decoction | In vivo | Mice | 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2 mL for 24 h | NM | Have a mild sedative effect on mice, and increased doses did not induce sleep | Shen and Wang (1957) | |

| Clerodendronin A | In vivo | Mice | 5, 10 mg/20 g for 2 h | Chlorpromazine, rifampicin | Sedative index (5.58) was stronger than the effect of rifampicin (3.38) | Xu et al. (1960a) | |

| Anti HIV-1 activity | |||||||

| Acteoside (102) | In vitro | HIV-1 integrase | 90 min | Curcumin and L-chicoric acid | IC50 value against HIV-1 integrase was 7.8 μM | Kim et al. (2001) | |

| Isoacteoside (108) | In vitro | HIV-1 integrase | 90 min | Curcumin and L-chicoric acid | IC50 value against HIV-1 integrase was 13.7 μM | Kim et al. (2001) | |

| Whitening activity | |||||||

| Acteoside (102) | In vitro | Tyrosinase activity | 100 µM for 10 min | Arbutin | Inhibition ratios of tyrosinase activity were 102.9, 104.9, 107.7% at 1, 10, 100 µM. | Yoon et al. (2009) | |

| Isoacteoside (108) | In vitro | Tyrosinase activity | 100 µM for 10 min | Arbutin | Inhibition ratios of tyrosinase activity were 98.1, 100.3, 115.7% at 1, 10, 100 µM. | Yoon et al. (2009) | |

| Insect feeding stimulant activity | |||||||

| Clerodendrin B (48) | In vivo | Turnip sawfly | 0.1–10 μg/64 mm2 | NM | 100% feeding response at 10 μg/64 mm2 | Nishida et al. (1989) | |

| In vivo | Turnip sawfly | NM | NM | Effective dose was 2 μg/grain | Nishida and Fukami (1990) | ||

| Clerodendrin D (49) | In vivo | Turnip sawfly | 0.1–10 μg/64 mm2 | NM | At 10 μg/64 mm2, the feeding response is close to 100% | Nishida et al. (1989) | |

| In vivo | Turnip sawfly | NM | NM | Effective dose was 2 μg/grain | Nishida and Fukami (1990) | ||

| Clerodendrin H (53) | In vivo | Turnip sawfly | 10–11–10–6/filter paper | NM | 100% feeding response at 10−7g/64 mm2 | Kawai et al. (1998) | |

| Clerodendrin I (54) | NM | Kawai et al. (1999) | |||||

| Inhibition of Eichhornia crassipes activity | |||||||

| Extracts | In vitro | Chlorophyll content, catalase activity and malondialdehyde content | 0.04 g/mL for 18 d | Blank: sodium phosphate buffer; Control: glycerol | Chlorophyll content was 0.710 mg/g, peroxidase activity 67.500 U/g/min, malondialdehyde content 12.015 mmol/g. | Zheng and Lu (2012) | |

Pharmacological activities of compounds isolated from Clerodendrum trichotomum.

Note: NM, not mentioned; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; MC, methylene chloride; S. aureus, Staphylococcus aureus; E. coli, Escherichia coli; H. pylor, Helicobacter pylori.

6.1 Antihypertensive activity

The study on the antihypertensive pharmacology of C. trichotomum first began in China in the 1950s and 1960s. The water extracts of the leaves and twigs of C. trichotomum (“Chou Wu Tong” in Chinese) showed different degrees of hypotensive effect on anesthetized or awake rats and dogs, as well as renal hypertensive rats and dogs, regardless of oral administration or injection (Xu and Xing, 1962). Xu and Peng reported that the antihypertensive effects are closely related to the central nervous and endovascular receptors (Xu and Peng, 1960). Other research have shown that its antihypertensive mechanism is closely related to the direct dilation of blood vessels and the blocking of ganglia (Xu, 1962). Lu et al. found that C. trichotomum is effective in lowering blood pressure by increasing renal blood flow and promoting urinary water and sodium excretion (Lu et al., 1994).

Kang et al. isolated a series of phenylpropanoid glycosides from the stems of C. trichotomum and found that these compounds acteoside (102), martynoside (103), leucosceptoside A (104), isoacteoside (108), and isomartynoside (109) had significant angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity, with IC50 values were 373.3 ± 9.3 µg/mL, 524.4 ± 28.1 µg/mL, 423.7 ± 18.8 µg/mL, 376.0 ± 15.6 µg/mL, 505.9 ± 26.7 µg/mL, respectively. The antihypertensive effect of C. trichotomum may be, at least in part, due to ACE inhibitory effect of the phenylpropanoid glycosides (Kang et al., 2003).

Morita et al. isolated a flavonoid glycoside, clerodendroside (82), from the leaves of C. trichotomum, which proved to have a hypotensive effect on anaesthetised rats (Morita et al., 1977).

6.2 Antitumour activity

The large number of compounds in C. trichotomum has a variety of anti-tumour activities, including breast cancer cells MCF-7, 4T1, lung cancer cells A549, hepatocellular carcinoma cells HepG2, cervical cancer cells Hela, melanoma cells B16, haematological leukemia cells K562, acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells CEM, acute promyelocytic leukaemia cells HL-60, intestinal cancer cells HCT-8 and so on.

Li et al. isolated nine abietane diterpenoids from the EtOAc part of the stems of C. trichotomum, and cyrtophyllone B (9), villosin B (14), villosin C (15), teuvincenone A (19), uncinatone (26) were found to have remarkable cytotoxicity against four cancer cell lines (A549, HepG-2, MCF-7 and 4T1) with IC50 values ranging from 8.79 to 35.46 µM (Li et al., 2014b). Then, 4 abietane diterpenoids were obtained from the n-butanol portion by the same research group, and villosin C (15), teuvincenone B (20) and ucinatcone (26) were found to have good antitumour activity (Li et al., 2022b). Ucinatcone (26) inhibited the proliferation of MCF-7, A549 and HepG2 cells most strongly, with the IC50 of 25.00, 22.34, and 12.50 μM, respectively. Only villosin C (15) had inhibitory activity on the proliferation of K562 cells, with an IC50 of 28.41 μM. Teuvincenone B (20) had some inhibitory activity on the proliferation of MCF-7 and HepG2 cells, with IC50 of 43.18 and 29.74 μM, respectively. Wang et al. isolated and characterized 14 rearranged abietane diterpenoids from the roots of C. trichotomum (Wang et al., 2013a). All isolates were tested for their cytotoxicities against five human cancer cell lines (BGC-823, Huh-7, KB, KE-97, and Jurkat), only uncinatone (26), mandarone E (27), teuvincenone E (29), (10R,16S)-12,16-epoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-18-oxo-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,11,13-pentaene-7-one (31), (3S,4R,10R,16S)-3,4:12,16-diepoxy-11,14-dihydroxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-5,8,11,13-tetraene-7-one (44) and 12,16-epoxy-17(15→16),18(4→3)-diabeo-abieta-3,5,8,12,15-pentaene7,11,14-trione (45) were found to show cytotoxic effects with IC50 values of 0.83–50.99 μM. The study of structure-activity relationship (SAR) shows that the rearranged A-ring and an intact 2-methyl-2-dihydrofuran moiety are supposed to be necessary to demonstrate cytotoxicity. A dimeric diterpene trichotomone (58) was isolated from the roots and inhibited in vitro cytotoxicities against several human cancer cell lines (A549, Jurkat, BGC-823 and 293TWT) with IC50 values ranging from 7.51 to 19.38 μM (Wang et al., 2013b).

Five steroids were isolated from the leaves of C. trichotomum (Xu et al., 2013), of which (20R,22E,24R)-3β-hydroxy-stigmasta-5,22,25-trien-7-one (97) and (20R,22E,24R)-stigmasta-5,22,25-trien-3β,7β-diol (98) exhibited moderate cytotoxicity in vitro against HeLa cell line, with IC50 at 35.67 and 28.92 μg/mL, respectively. The same research group (Xu et al., 2014) also isolated seven cyclohexylethanoids from the leaves. 5-O-butyl cleroindin D (137) and 1-hydroxy-1-(8-palmitoyloxyethyl) cyclohexanone (139) were evaluated for their cytotoxicity against A549 human tumor cell line, but there were no obvious cytotoxicity.

Nagao et al. regarded acteoside (102) and isoacteoside (108) as the antiproliferative constituents and found that the content of active compounds was higher in the bark of C. trichotomum (ca. 4.6%) than in leaves (ca. 0.6%). The GI50 of acteoside (102) against three tumor cell lines (MK-1: human gastric adenocarcinoma, HeLa: human uterus carcinoma, and B16F10: murine melanoma) were 40, 66 and 8 μM, while GI50 of isoacteoside (108) were 40, 61, 8 μM, respectively. SAR study suggests that the antiproliferative activities of phenylpropanoids depend on the 3,4-dihydroxyphenethyl group with some contribution of the 3,4-dihydroxycinnamoyl (caffeoyl) group (Nagao et al., 2001).

6.3 Antioxidant activity

Phenylpropanoid glycosides 2″-acetylmartynoside (106) and 3″-acetylmartynoside (107), isolated from the stems of C. trichotomum, showed antioxidant activity in terms of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging effects (Chae et al., 2007). Jionoside D (105), isoacteoside (108) and trichotomoside (125), also isolated from the stems, exhibited scavenging activity of intracellular ROS and of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical, as well as lipid peroxidation inhibitory activity. This radical scavenging activity of them protected the cell viability of Chinese hamster lung fibroblast (V79-4) cells exposed H2O2 (Chae et al., 2004; Chae et al., 2005; Chae et al., 2006). Furthermore, jionoside D (105) and isoacteoside (108) increased the activities of cellular antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) (Chae et al., 2004; Chae et al., 2005). Gao et al. isolated ecdysanols D (123) and ecdysanols E (124) from the leaves and twigs, which had moderate antioxidant activity with respective IC50 values of 66.07 and 53.60 μM (Gao et al., 2022). Lee et al. isolated five compounds from the flowers and found that acteoside (102), martynoside (103), leucosceptoside A (104), isoacteoside (108) exhibited strong DPPH antioxidant activity (Lee et al., 2016). Yoon et al. isolated acteoside (102) and isoacteoside (108) from C. trichotomum, both of which dose-dependently inhibited silica-induced ROS production in B16 melanoma cells (Yoon et al., 2009). Ono et al. also reported that among six isolated compounds, acteoside (102) showed the strongest activity with EC50 values of 22.2, 80.2, 23.4 μM in the scavenging of DPPH radical, H2O2 and O2− radical (Ono et al., 2013). Taken together, these findings suggest that phenylpropanoid glycosides isolated from C. trichotomum exhibits antioxidant properties.

A flavonoid glycoside apigenin 7-galacturonide (81) was isolated from the leaves of C. trichotomum and exhibited moderate NO scavenging activity, with the EC50 452 μM (Ono et al., 2013).

6.4 Antiinflammatory activity

Choi et al. used carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema model to study the antiinflammatory effect of methanol extracts from C. trichotomum leaves and found that the antiinflammatory activity of 60% methanol extract was higher than indomethacin, and that this extract also inhibited the production of PGE2 in RAW 264.7 cells (Choi et al., 2004). Park et al. found that methanol extract of C. trichotomum leaves inhibited the production and expression of tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) in mononuclear macrophages in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells in a dose-dependent manner by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) (Park and Kim, 2007). Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed that the activity of NF-κB was also inhibited, which means that C. trichotomum inhibits the expression of the pro-inflammation gene through the inhibition of NF-κB dependent pathway in RAW 264.7 cells.

Hu et al. discovered a range of diterpenoids from the roots of C. trichotomum and assessed their abilities to inhibit NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Villosin C (15) 15,16-dehydroteuvincenone G (23), 2α-hydrocaryopincaolide F (35) and trichotomin A (46) exerted inhibitory effects at noncytotoxic concentrations with IC50 values of 15.5, 6.0, 6.5 and 10.6 μM, respectively, better than the positive control. Compounds 15α-hydroxyteuvincenone E (37) and trichotomin B (38) showed moderate or weak activities with IC50 values of 28.9–38.6 μM (Hu et al., 2018).

Lee et al. reported that acteoside (102) inhibited histamine release in RBL-2H3 mast cells stimulated by melittin, arachidonic acid and toxocarotene regardless of the presence of extracellular Ca2+ (Lee et al., 2006). The anti-asthmatic effect on the aerosolized ovalbumin (OA) challenge in the OA-sensitized guinea-pigs of acteoside (102) was also evaluated (Lee J. Y. et al., 2011). 102 inhibited specific airway resistance in immediate asthmatic response, inhibited protein content at a dose of 25 mg/kg, and histamine content and PLA2 activity at a dose of 50 mg/kg, in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). Kim et al. isolated three phenylpropanoid compounds from the leaves of C. trichotomum, the 80% methanol fraction and acteoside (102) were found to have in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory activity (Kim et al., 2009).

Min et al. found that apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucuronopyranoside (84) was more effective than omeprazole on reflux esophagitis and gastritis in mice (Min et al., 2005). Yang et al. isolated four 24-ethylcholestane derivatives from the roots of C. trichotomum; in vitro screening for anti-inflammatory activity showed that 24-ethyl-7-oxocholesta-5,22(E),25-trien-3β-ol (91) could dose-dependently inhibit IL-8 production in colon cancer HT-29 cells induced by IL-1β (Yang et al., 2014).

6.5 Antibacterial activity

Choi et al. tested the antibacterial activity of the MeOH extract from C. trichotomum. The n-hexane and methylene chloride (MC) fractions showed antibacterial activity against Helicobacter pylori at a concentration of 1.7 mg/mL and showed inhibition zones of 10 and 11 mm in disc assay, respectively. β-Amyrin (70) and 22-dehydroclerosterol (93), isolated from the MC fraction, revealed moderate antibacterial effects against Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and H. pylori. 70 showed clear zones of 12 and 13 mm against E. coli and H. pylori, respectively (Choi et al., 2012).

Gao et al. isolated two polyketides clerodendruketone A (134) and clerodendruketone B (135) from the leaves and twigs of C. trichotomum. The antibacterial activity evaluated by turbidimetry assay demonstrated significant antimicrobial activity of 134 (50 µg/mL) with the inhibition rate between 30%∼60% against E. coli and 60%∼80% against S. aureus, while the rates of 135 (50 µg/mL) were both between 30% and 60% (Gao et al., 2022).

6.6 Analgesic effect

Electric shock rat tail method (Wang and Shen, 1957) showed that the analgesic effect was shown when the injection of Chou Wu Tong (leaves and twigs of C. trichotomum) decoction into the abdominal cavity of mice was above 1.65 g/kg, and the peak value appeared 20–40 min after administration, and then gradually decreased, which could be maintained for 2 h. The effect before flowering was better than after flowering. The analgesic effect in mice was observed by hot plate and found that clerodendronin B, an acid soluble granular crystal of Chou Wu Tong, had a significant analgesic effect, and the effect was stronger and longer than that of morphine at a dose of 10–20 mg/Kg when injected into mice peritoneally at a dose of 400–800 mg/Kg (Xu et al., 1960b).

6.7 Sedative effect

Oral administration or intraperitoneal injection of the Chou Wu Tong decoction was found to have a mild sedative effect on mice, and increased doses did not induce sleep (Shen and Wang, 1957). Clerodendronin A, a water-soluble acicular crystal of Chou Wu Tong, has a strong sedative effect and has a synergistic effect with pentobarbital sodium (Xu et al., 1960b).

6.8 Anti HIV-1 activity

Kim et al. isolated seven phenylethanoid glycosides from the stems of C. trichotomum. Acteoside (102) and isoacteoside (108) showed inhibitory activities against HIV-1 integrase with IC50 values of 7.8 and 13.7 μM, respectively (Kim et al., 2001).

6.9 Others

Acteoside (102) and isoacteoside (108), isolated from C. trichotomum, showed whitening activity by the inhibition of tyrosinase activity and tyrosinase expression (Yoon et al., 2009). Clerodane-type diterpenes clerodendrin B (48), clerodendrin D (49), clerodendrin H (53) and clerodendrin I (54), were found to have insect feeding stimulant activity of the turnip sawflies, Athalia rosae ruficornis (Nishida et al., 1989; Nishida and Fukami, 1990; Kawai et al., 1998; Kawai et al., 1999). In addition, the sodium phosphate buffer extract of C. trichotomum leaves inhibited the growth of Eichhornia crassipes, causing the leaves dry, rot or even decline, which can be used for biological control of E. crassipes (Zheng and Lu, 2012).

7 Concluding remarks

C. trichotomum is endemic to East Asia and has been studied mainly in Japan, Korea and China. At present, the research of chemical composition mainly focus on terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, flavonoids and steroids. Most of the terpenoids are diterpenoids, and the main structural types are abietane-type and clerodane-type. Phenylpropanoids exist mainly in the form of glycosides. The quantity and category of volatile oil components in the literature reports are different, which may be related to different origin and extraction methods. The extracts and isolated compounds of C. trichotomum have showed many pharmacological effects such as antihypertensive, antitumor, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory, but their toxicological studies have rarely been reported.

It has been a matter of debate whether C. trichotomum belongs to the family Verbenaceae or the family Lamiaceae (Briquet, 1895; Latta, 2008). This review briefly summarises the secondary metabolites isolated from C. trichotomum reported in the literature. Among the 164 compounds, the largest number was abietane diterpenoids, with 39. Abietane diterpenoids are abundant in C. trichotomum, both in the aerial parts and the roots. From a chemotaxonomical point of view, the abundant presence of abietane diterpenoids supports the view that C. trichotomum transfers Verbenaceae to Labiaceae.

Studies on the chemical components of the plant mainly focus on leaves, stems, roots and fruits. So far, only one paper (Lee et al., 2016) has reported the isolation of four phenylpropanoid glycosides and a monoterpene glycoside from the flowers. However, Xu et al. found that the antihypertensive, analgesic and other activities of C. trichotomum were better before flowering than after flowering (Wang and Shen, 1957; Xu and Xing, 1962), and the reason is still unclear. Therefore, it is a very interesting and meaningful work to study the chemical compositions and pharmacological activities of flower parts and the difference between pre-flowering and post-flowering. In addition, early studies of C. trichotomum were focused on the isolation and identification of individual or several compounds from the extracts, or the pharmacological activity of crude extracts. Future research on chemical and pharmacological activities should be further closely combined to clarify the bioactive compounds of C. trichotomum. On this basis, one or several active compounds should be determined and the quality control standard of C. trichotomum will be established.

The active compounds isolated from C. trichotomum mainly included abietane diterpenoids, phenylpropanoid glycosides, flavonoid glycosides, clerodane diterpenoids and steroidal compounds, which showed excellent activities of reducing blood pressure, antitumor, antioxidant, antiinflammatory, anti-HIV-1 and promoting insect feeding. Among these ingredients, the plant’s major phytochemical is acteoside (102), which has rich pharmacological activities, such as anti-hypertension, antitumor, antioxidant, antiviral and whitening. Relevant studies have shown that it exists in various stages of clinical trials for anti-nephritic, hepatoprotective, and osteoarthritic activity (Srivastava and Shanker, 2022). Some of the isolates are structurally similar to the more highly active phytocompounds. However, they have not been tested for their potential biological activities. The study of the activity of analogues as well as other types of secondary metabolites is an important area for further research, as infectious diseases and civilizational diseases such as cancer require the search for new therapeutic active structures. At the same time, the active substances responsible for analgesic (Wang and Shen, 1957) and sedative (Shen and Wang, 1957) effects of C. trichotomum are still unclear, and Clerodendronin A (Xu et al., 1960a) and Clerodendronin B (Xu et al., 1960b), as reported crystals, need to be further purified and identified. Additionly, SAR studies were in focus of only 2 literatures (Nagao et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2013a) in the past. Therefore, the study of SAR is one of the future research directions. Of course, the chemical modifications of the isolated compounds are necessary in order to obtain semi-synthetic analogues with enhanced biological activity and improved bioavailability or safety. Recent studies have shown that there are abundant secondary metabolites associated with diverse biological activities in C. trichotomum. However, in numerous studies, the excellent pharmacological activity of C. trichotomum was established through cell culture and in vitro experiments. Still, an effective study through in vivo experiments is missing in the scientific literature. Future studies should employ appropriate animal models to elucidate the mechanism of action.

C. trichotomum is a kind of medicinal and edible plant which integrates ecological afforestation, garden greening, herbal medicine and flavor wild vegetable. But the practical application of C. trichotomum is still limited, and its pharmacological potential is also underutilized. In this paper, a comprehensive review of the literature was carried out, the information about extraction, isolation and pharmacological experiments were listed, and the isolated compounds were critically collated. The summary of the chemical compositions of C. trichotomum supports its attribution in plant classification. Compiled information on phytochemicals and pharmacological activities, as well as highlighted gaps and suggested precise directions, may contribute to the development of C. trichotomum as a drug for the treatment of disease, a Chinese herbal preparation, a plant pesticide or a functional food.

Statements

Author contributions

LL: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. ZT: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing–original draft. SX: Data curation, Resources, Software, Writing–original draft. XD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Writing–original draft. YW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Writing–original draft. XW: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding