Abstract

Introduction:

Chinese herbal medicine (CHM) taken orally is frequently utilized to enhance functional ability and independence in cerebral palsy (CP); nonetheless, there is a lack of current evidence regarding the efficacy of oral CHM in treating CP. Additionally, the general complexities of CHM prescriptions often obscure the underlying mechanisms. Our study aims to assess the efficacy of oral CHM in treating CP, a meta-analysis will be conducted on randomized clinical trials (RCTs).

Materials and methods:

We searched Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, PubMed Central, ClinicalTrials.gov, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), from 1990 to 2022. The primary outcome was the improvement in Effectiveness rate (ER). The secondary outcome was the improvement of motor function (GMFM). Subgroup analysis and trial sequential analysis (TSA) were conducted to confirm results consistency. Core CHMs were investigated through system pharmacology analysis.

Results:

Seventeen RCTs were analyzed, in which CHMs with Standard treatment (ST) were compared to ST alone. All participants were aged <11 years. More participants in the CHM group achieved prominent improvement in ER (RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.13–1.30, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 32%) and higher GMFM improvement (SMD: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.33–1.65, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 92%). TSA also showed similar results with proper statistical power. Core CHMs, such as Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Ex DC., Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf, Paeonia lactiflora Pall., processed Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC., Astragalus mongholicus Bunge, and Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, exerted effects on immune modulation and metabolism systems. The subgroup analysis showed participants using core CHMs or longer CHM treatment duration, and studies enrolling CP with spastic or mixed type, or mild-to-moderate severity had better outcomes in CHM groups with less heterogeneity.

Conclusion:

CHMs may have a positive impact on managing pediatric CP; however, the potential bias in study design should be improved.

Systematic Review Registration:

Identifier CRD42023424754.

1 Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the most common cause of disability in childhood, with an estimated global prevalence between 0.16% and 0.37% (McIntyre et al., 2022). The term refers to a group of neurological disorders that affect movement and posture along the lifespan, caused by damage to the developing brain. It results in motor disability, and some patients may also develop epilepsy or disturbance of cognition, behavior, communication, sensation, and perception (Rosenbaum et al., 2007; Novak et al., 2012). In terms of socioeconomic aspects, individuals with CP face the impact of multiple disabilities; consequently, they require long-term medication, rehabilitation, and care. Their necessary expenses are significantly higher compared with those of their healthy age-matched counterparts, thus imposing substantial burdens on caregiving families (Vadivelan et al., 2020).

The treatment of CP focuses on improving movement and reducing the disruptions caused to daily activities (Colver et al., 2014). Therefore, physical rehabilitation is currently the standard first-line therapy for CP (Demont et al., 2022). Other therapies include medication, speech rehabilitation, occupational rehabilitation, and surgical intervention (Vitrikas, Dalton, and Breish, 2020). However, recent research indicates that the improvement in gross motor skills through rehabilitation remains limited (Liang et al., 2021). Recent advances in treatment strategies, such as robot-assisted devices and virtual reality, have been used for motor learning and cortical reorganization; nevertheless, the efficacy of these approaches remains uncertain (Bekteshi et al., 2023; Paul et al., 2022).

Consequently, there is a growing interest in exploring alternative medical therapies for improving functional ability and independence of patients with CP. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has been commonly used for centuries as adjunctive therapy in Asia. Studies have found that combining TCM with Standard treatment (ST) can improve motor function and activities of daily living in patients with CP (Zhang et al., 2010; Liao et al., 2017). Moreover, a recent systematic review demonstrated that the combination of TCM and modern rehabilitation therapies may resulted in effective improvements in gross motor function, muscle tone, and functional independence in children with CP (Chen et al., 2023). Thereby, TCM seems to enhance the independence of patients’ daily activity and may reduce the burden on caregivers and the healthcare system. However, previous review articles on TCM interventions often encompassed oral Chinese herbal medicine (CHM), acupuncture, massage, or low-level laser therapy, whereas studies focusing exclusively on CHM remain relatively scarce.

As to CHM efficacy on CP, a recent study utilizing network pharmacology and bioinformatics has elucidated the therapeutic potential of Liuwei Dihuang pills, a traditional CHM, in the treatment and management of CP. The key bioactive constituents of Liuwei Dihuang pills, including quercetin, stigmasterol, and kaempferol, exert their effects of modulating immunological and inflammatory responses through the regulation of several critical signaling pathways, including the PI3K-Akt, IL-17, Jak-STAT, and NF-κB pathways, which are integral to the pathophysiology of CP (Wang et al., 2024). Additionally, in animal study, tanshinone IIA, ingredient of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, showed neuroprotective effect and weakened spasticity through inflammation, p38MAPK and VEGF pathway (Zhang et al., 2018). Moreover, a review article reported improved daily activity outcomes when Oriental herbal medicine was integrated into rehabilitation programs (Lee et al., 2018). However, there is still a lack of extensive and up-to-date literature, robust bias assessment, and statistical analysis regarding the efficacy and safety of oral CHMs as well as the core CHMs for CP.

The aim of this study was to compile evidence from recent Randomized clinical trials (RCT) on the use of oral CHM for pediatric CP and assess its potential effectiveness. Additionally, network pharmacology analysis was also undertaken to identify core CHMs utilized in the examined trials and elucidate potential pharmacological pathways involved.

2 Materials and methods

This study protocol was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (No. CRD42023424754).

2.1 Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

1) RCT studies.

2) CP diagnosis was based on diagnostic criteria evaluated by a physician.

3) Age < 18 years.

4) Interventions involved the oral administration of single or mixed traditional CHMs.

5) No limitations based on ethnicity, age, or language.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

1) Non-RCT studies.

2) Use of folk medicine or traditional medicine other than CHM (i.e., acupuncture, or massage).

3) Studies evaluating the effectiveness of CHMs administered topically (i.e., moxibustion, herbal bath, fumigation therapy).

4) Lack of a control group.

5) The control group did not receive ST.

6) The intervention group did not receive CHM combined with ST.

7) Outcome assessment other than Effectiveness rate (ER), Gross Motor Function Measure score (GMFM), Activities of Daily Living for CP recover evaluation (ADL) (Shuchun, 2000; Yingyuan, 2009), and Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) score.

8) Studies not published in peer-reviewed journals.

9) Lack of search strategy and information sources.

We conducted thorough searches in various electronic databases from 1 January 1990 to December 2022. The databases included Cochrane Library, PubMed, Embase, Scopus, PubMed Central, ClinicalTrials.gov, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The specific search approaches are provided in Supplementary Appendix S1. The search terms were used as follow: “Cerebral Palsy” (MeSH Terms) for patient group, and [“Medicine, Chinese Traditional” (Mesh) or “Herbal Medicine” (Mesh) or “Medicine, Korean Traditional” (Mesh) or “Medicine, Kampo” (Mesh)] for intervention.

2.2 Data extraction

Huang independently extracted data using a predefined format, as outlined in Table 1, which includes details on the study authors, publication year, sample size, sex, age, intervention, and primary outcomes. Any discrepancies were resolved via deliberations with Cheng, Yang, and Chen. The extracted information included the publication year, study country, study design, CHM content and duration, type of standard management, diagnostic criteria, sample size, participant age and sex, and outcome assessments. Additionally, information regarding interventions, including composition, dosage, and frequency of usage for both control and intervention groups, was recorded. If necessary, and at the discretion of the reviewing author, the corresponding authors of the clinical studies were contacted to obtain any missing data.

TABLE 1

| References | Sample size, n (T/C) | Sex, n M:F (T) | Sex, n M:F (C) | Age, mean ± SD (T) | Age, mean ± SD (C) | Type of CP | Treatment intervention (T) | Compare intervention (C) | Intervention formula | Number of compositions in formula | Frequency and duration | Primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wu J et al. (2022) | 30/30 | 18:12 | 19:11 | 43.07 ± 10.01 months | 42.73 ± 10.04 months | Dyskinetic | CHM, PT, OT, speech training, music therapy | PT, OT, speech training, music therapy | Liuwei Dihuang pill and Yigong powder (granule) | 10 | Unknown frequency for 1 month | GMFM-88, WeeFIM, Gesell |

| Tung (2022) | 45/45 | 23:22 | 24:21 | 4.2 ± 1.5 years | 4.1 ± 1.3 years | Spastic | CHM, PT | PT | Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu Tang (decocting pieces) | 14 | 1 dose/day for 30 days | TCM symptom score, ADL, FAC, MWS, 6MWT |

| Zhang (2021) | 36/35 | 18:18 | 17:18 | 34.65 ± 3.10 months | 34.36 ± 3.28 months | Mixed | CHM, WM, massage | WM, massage | Kaiqiao Xingshen Decoction (decocting pieces) | 7 | 1 dose/day for 1 month | TCM symptom score, FDA, brain Doppler ultrasound, ER (TDS) |

| Cai (2020) | 42/42 | 24:18 | 22:20 | 3.1 ± 0.8 years | 3.3 ± 0.5 years | Spastic | CHM, FES | FES | Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu Tang (decocting pieces) | 13 | 1 dose/day for 8 weeks | GMFM-88, PDMS-2, ER, MAS |

| Zhang Y et al. (2019) | 42/42 | 23:19 | 26:16 | 3.21 ± 0.16 years | 3.34 ± 0.18 years | Spastic | CHM, WM, PT | WM, PT | Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu Tang (decocting pieces) | 13 | 1 dose/day, and 4 weeks/course for 3 courses | GMFM-88, TCM symptom score, MAS, PDMS-2, PedsQL, serum BDNF, serum NSE, ER |

| Geng (2019) | 51/51 | 26:25 | 27:24 | 7.41 ± 2.71 years | 7.38 ± 2.68 years | Mixed | CHM, WM, acupuncture | WM, acupuncture | Xingnao Kaiqiao Tang (decocting pieces) | 14 | 1 dose/day for 3 months | ER, ADL, FMA PDMS, Berg, MDI, PDI |

| Liu and Dong (2019) | 74/74 | 44:30 | 41:33 | 28.65 ± 12.07 months | 28.75 ± 13.12 months | None recorded | CHM, WM, PT, massage | WM, PT, massage | Kaiqiao Xingshen Decoction (decocting pieces) | 7 | 1 dose/day for 1 month | FDA, GMFM, FMFM, ER, serum NSE, serum ET-1, serum IGF-1 |

| Ma et al. (2018) | 36/36 | 24:10 | 20:11 | 25.9 ± 18.3 months | 25.7 ± 13.4 months | Spastic | CHM, PT, OT, massage, acupuncture, steam therapy | PT, OT, massage, acupuncture, steam therapy | Pujin Keli (granule) | 4 | ≤4 years: 1 dose/day; 4–6 years: 2 doses/day 4 weeks/course for 3 courses |

GMFM, Gesell, MAS, TCM symptom score, ER |

| Sun et al. (2017) | 60/60 | 32:28 | 33:27 | 3.38 ± 2.01 years | 3.51 ± 2.17 years | Dystonia | CHM, PT | C1-healthy children: no intervention C2-CP: PT |

Xingnao Yizhi Fang (decocting pieces) | 11 | 1 dose/day, 10 times/course, 2 days off between courses for 1 year | GMFM-88, serum BDNF, serum TGF-β1, Manual Muscle Testing |

| Shan et al. (2017) | 34/34 | 24:13 | 21:10 | 2.5 ± 2.2 years | 2.6 ± 2.1 years | None recorded | CHM, PT, OT, massage, acupuncture, speech training, music therapy, wax therapy, medicinal baths | PT, OT, massage, acupuncture, speech training, music therapy, wax therapy, medicinal baths | Nourishing Kidney and Inducing Resuscitation for Expelling Phlegm Prescription (granule) | 10 | 1.5–3 years, 2/3 pack/day; 4–6 years: 1 pack/day for 4 months | Gesell, ER |

| Yu et al. (2016) | 40/40 | 21:19 | 23:17 | 6.6 ± 3.4 years | 6.4 ± 3.2 years | Spastic | CHM, PT, massage | PT, massage | Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu Tang (decocting pieces) | 13 | 1 dose/day for 4 weeks | ER, FAC, MWS, 6MWT |

| Cheng et al. (2016) | 17/13 | 10:7 | 8:5 | 14 months | 13 months | None recorded | CHM, PT | PT | High dose of Astragalus mongholicus (decocting pieces) | 5 | 1 dose/2 days, and 14 days/course for 10 courses | GMFM, ER |

| Du et al. (2016) | 32/30 | 20:12 | 20:10 | 10.46 ± 3.54 months | 9.96 ± 4.18 months | None recorded | CHM | WM | Modified Suanzaoren (granule) | 8 | 1 dose/day for 2 weeks | ER (sleep quality) |

| Lou and Shi (2016) | 30/30 | 19:11 | 18:13 | 2.5 ± 1.3 years | 2.6 ± 1.4 years | Spastic | CHM, WM | WM | Shujinhuoluo Wan (pill) | 13 | 1 dose/day, and 6 weeks/course for 10 courses | GMFM, MAS, ADL, WISC, serum IL4, serum IFN-γ, serum IFN-α |

| Lu et al. (2012) | 40/40 | 25:15 | 23:17 | 4.50 ± 1.08 years | 4.30 ± 0.79 years | Spastic | CHM, WM, PT | WM, PT | Shenluqizhi Decoction (decocting pieces) | 11 | 1 dose/day and 3 months/course for 2 courses | ER, TCM symptom score, ADL, MAS |

| Shi and Xie (2015) | 70/70 | 45:25 | 35:35 | 7.5 ± 1.5 years | 7.8 ± 1.4 years | Spastic | CHM, SPR, WM | SPR, WM | BuShen JianNao (capsule) | 9 | 4 doses/time, 3 times/day for 1.5 months | GMFM-88, ER |

| Qian (2009) | 35/35 | 24:11 | 22:13 | 3.37 ± 0.28 years | 3.20 ± 0.36 years | Mixed | CHM, PT | PT | Sijunzi Decoction (decocting pieces) | 4 | 1 dose/day <5 years: tapered for 3 months |

ER, saliva amylase amount, serum Zn, serum Fe, hemoglobin |

Characteristics of included RCTs.

6MWT, 6-min walking test; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; Berg, Berg Balance Scale; ET-1, endothelin-1; FAC, functional ambulation category scale; FDA, Frenchay dysarthria assessment; FES, functional electrical stimulation; FMA, Fugl–Meyer assessment scale; FMFM, fine motor function measur; IFN-α, interferon-α; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; IL4, interleukin 4; M:F, male:female; MDI, mental developmental index; MWS, maximum walking speed; NSE, neuron specific enolase; PDI, psychomotor development index; PedsQL, pediatric quality of life inventory; SD, standard deviation; SPR, selective posterior rhizotomy; TDS, Teacher’s Drooling Scale; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-beta 1; WeeFIM, wee functional independence measure for children; WISC, Wechsler intelligence scale for children.

2.3 Quality assessment

Huang and Cheng evaluated the methodological quality using the Risk-of-bias (RoB) assessment tool established by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins et al., 2011). Any discrepancies in the assessment were resolved through consultations with Yang and Chen.

2.4 Outcome measurements

The primary outcome was the percentage of participants in whom the treatment showed prominent effectiveness. ER was selected since it was commonly used in most studies and provided a composite outcome for participants. It was commonly presented by classifying the clinical response at the end of the study into three grades, such as prominent effectiveness, effectiveness, and ineffectiveness. Prominent improvement, including prominent effectiveness and effectiveness, was confirmed according to the following criteria varied according to different RCTs: 1) GMFM total score improved by ≥1% (Cheng et al., 2016); 2) ≥1/3 symptoms improved (Geng, 2019; Yu, 2016; Lu et al., 2012); 3) TCM syndrome score improved by ≥20% (Zhang L. Q. et al., 2019; Ma et al., 2018); 4) efficacy index improved by ≥1% (Liu and Dong, 2019); 5) drooling improved by ≥1 level (Zhang, 2021); 6) MAS score decreased by ≥1 grade (Shi and Xie, 2015); 7) Peabody developmental motor scale-2 (PDMS-2) improved by ≥1% (Cai, 2020); 8) sleep quality significantly improved (Du et al., 2016); and 9) 10 sports function score improved ≥10 (Qian, 2009). The percentage of prominent improvement was compared between the CHM + ST and ST groups, and this information was extracted as the primary outcome. The secondary outcome included improvement of solely evaluated clinical score systems, such as the Gesell Developmental Scale (Gesell), GMFM indicating motor function, ADL, and MAS presenting the severity of limb spasticity.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The analysis of all data was conducted utilizing Cochrane Review Manager 5.4.1. (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014). The proportion of participants with prominent improvement in ER was analyzed using the Risk ratio (RR) and a 95% Confidence interval (CI). Numerical outcomes were analyzed using the Standardized mean difference (SMD) and/or Mean difference (MD). For data synthesis, a random-effects model with the Mantel–Haenszel test was used to summarize inverse variance and dichotomous data for continuous data. Heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using the I2-statistic. A funnel plot was used to detect publication bias. If bias was present, the trim and fill method (Peters et al., 2007) would be applied for correction. Additionally, Trial sequential analysis (TSA) was performed to confirm the efficacy of CHM. TSA is a novel method for evaluating treatment efficacy through interventional meta-analysis study in a more robust manner to mimic large-scale clinical trials (Wetterslev, Jakobsen, and Gluud, 2017; De Cassai et al., 2021; Kang, 2021). In this study, we adopted 5% type I error with 90% power of statistical examination in TSA to evaluate the consistency of results and the adequacy of the number of cases. TSA was carried out using proprietary software (Lan and DeMets, 1983). A system pharmacology analysis was conducted on the prescriptions from the included studies. Detailed methodologies are outlined in Supplementary Appendix S2. In summary, the Chinese herbal medicine network (CMN) was employed to identify the core CHMs, illustrating graphically the commonly used CHMs for CP. The pharmacological pathways of these core CHMs were clarified by referencing online databases for pharmacology pathways. Utilizing this well-established approach, we previously compared the effectiveness of CHM versus Western medicine (WM) in managing Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), allergic diseases, and diabetic nephropathy (Lu et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2023).

We conducted four subgroup analyses. Firstly, based on the type of CP, we divided the participants into spastic and mixed types. Secondly, dividing different initial symptom severity into three groups due to CP baseline severity was a main influencing factor to prognosticate long-term functional outcome. We used the ADL, Gesell, and MAS scores for categorization (mild, ADL: ≥91, Gesell: ≥55, MAS: <2; moderate, ADL: 61–90, Gesell: 40–54, MAS: 2; and severe, ADL: ≤60, Gesell: ≤39, MAS: >2) (Yuan et al., 2021; Huifang, 2012; Winstein et al., 2016). We divided the subgroup into mild-to-moderate and severe. Thirdly, we used the duration of the treatment course. We divided the duration into three subgroups, namely, 0–1 month, 1–3 months, and 3–6 months. We selected 1 month as the first cut point due to the shortest period for observing the efficacy of CHM (Yoo et al., 2016). Three months was the fastest time for neural recovery (Boecker et al., 2022; Schalow, 2002), and 6 months represented chronic phase of recovery (Gao et al., 2022). Finally, we extracted the studies that utilized core CHMs. For all analyses, excluding TSA, p-values < 0.05 denoted statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Literature search

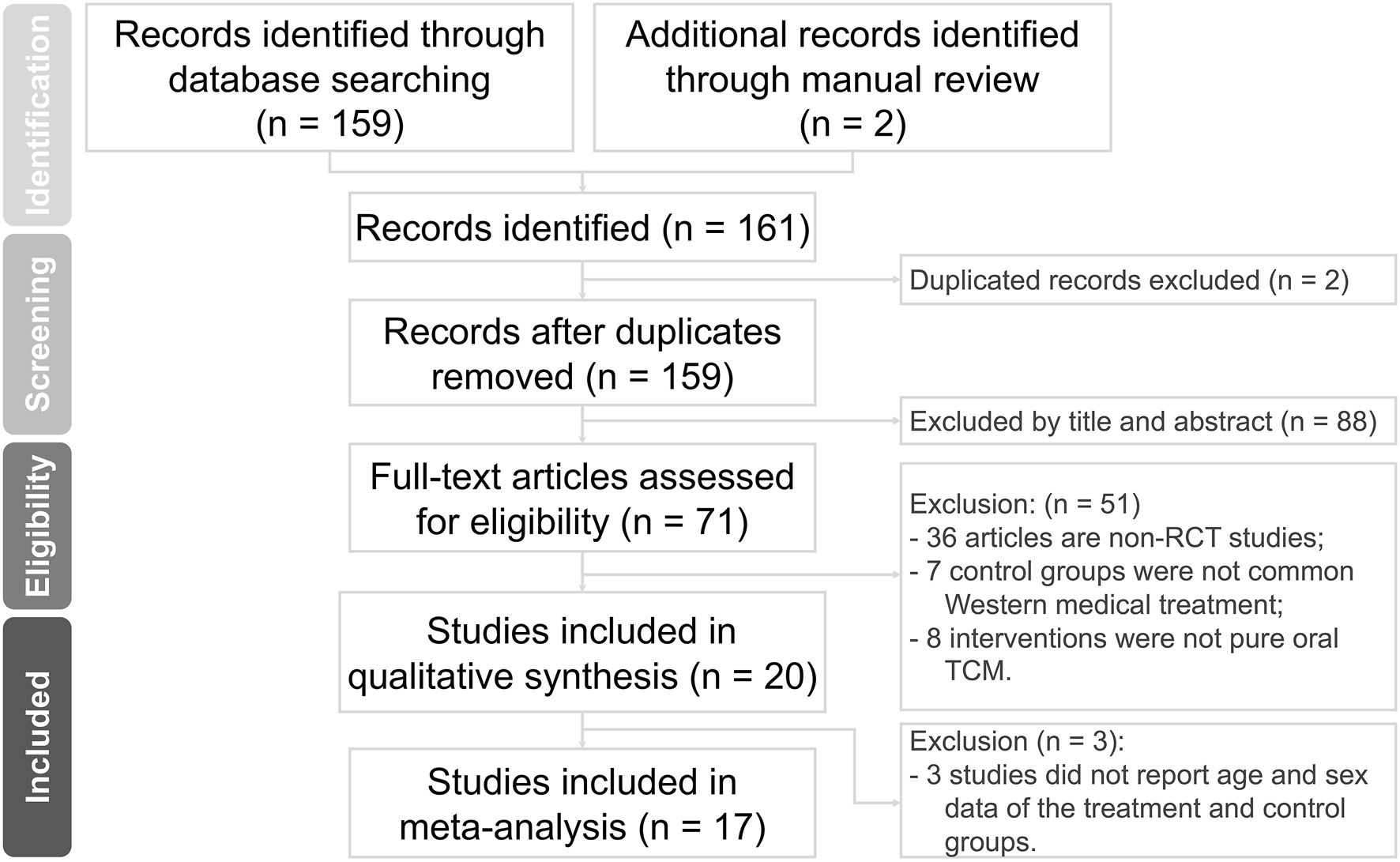

Our electronic and manual searches yielded a total of 161 references. After removing two duplicate records, 159 studies remained. A detailed examination of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 88 studies.

After this initial screening, we proceeded to retrieve and carefully evaluate the complete texts of 71 references. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 51 studies were removed. Furthermore, three studies were excluded due to the lack of detailed data on the CHM and ST groups. Finally, our comprehensive assessment led to the inclusion of 17 studies, involving a total of 1,421 participants. These data are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1

Flowchart of the search strategy.

3.2 Description of included studies

3.2.1 Characteristics of studies

Table 1 shows the detailed information of the analyzed studies, which were all RCTs. Sixteen studies adopted a two-arm parallel design, and only one used a three-arm design, in which only data from CHM and the control arm were extracted. All selected studies were sourced from China.

3.2.2 Characteristics of participants

In the analyzed studies, the age of the participants ranged from 0 to 11 years old. In terms of diagnostic criteria and classification, 11 studies followed the Chinese national clinical diagnostic criteria and classification as their standard, whereas six studies referred to the Rehabilitation Guideline for CP in China. Regarding the type of CP, eight studies enrolled only patients with the spastic type, while the remaining enrolled participants with all types of CP.

3.2.3 Design of the control group

ST, including Physical therapy (PT) and Occupational therapy (OT), was found in the control group of 11 trials. Five trials only used WM, and three trials used rehabilitation plus WM in the control group. The WM prescribed in trials included baclofen, dantrolene sodium, midazolam, phenobarbital, cerebrolysin, ligustrazine hydrochloride, or other medicines for nourishing neurons. With regard to ST, five trials added massage, and some added complementary therapy, such as speech training, dry needle therapy, steam therapy, music therapy, wax therapy, and medicinal baths. Notably, one study used Functional electrical stimulation (FES) in the control group, while another used Selective posterior rhizotomy (SPR) plus WM. The disparities among the experimental herbal formulas combined with PT, PT alone, and no treatment (i.e., healthy children) were discussed in a three-arm parallel trial.

3.2.4 Design of the intervention group

All included trials involved a combination of CHM with ST, and all prescriptions were mixed CHMs. The number of CHMs used in trials ranged from 4 to 14 (mean: 9; SD: 3). The frequency of CHMs combination usage was shown in Supplementary Appendix S3. Among all CHMs, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. (GU) and Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf. (PC) are the most frequently used combination of medications (47.059%). The duration of treatment ranged from 2 weeks to 15 months.

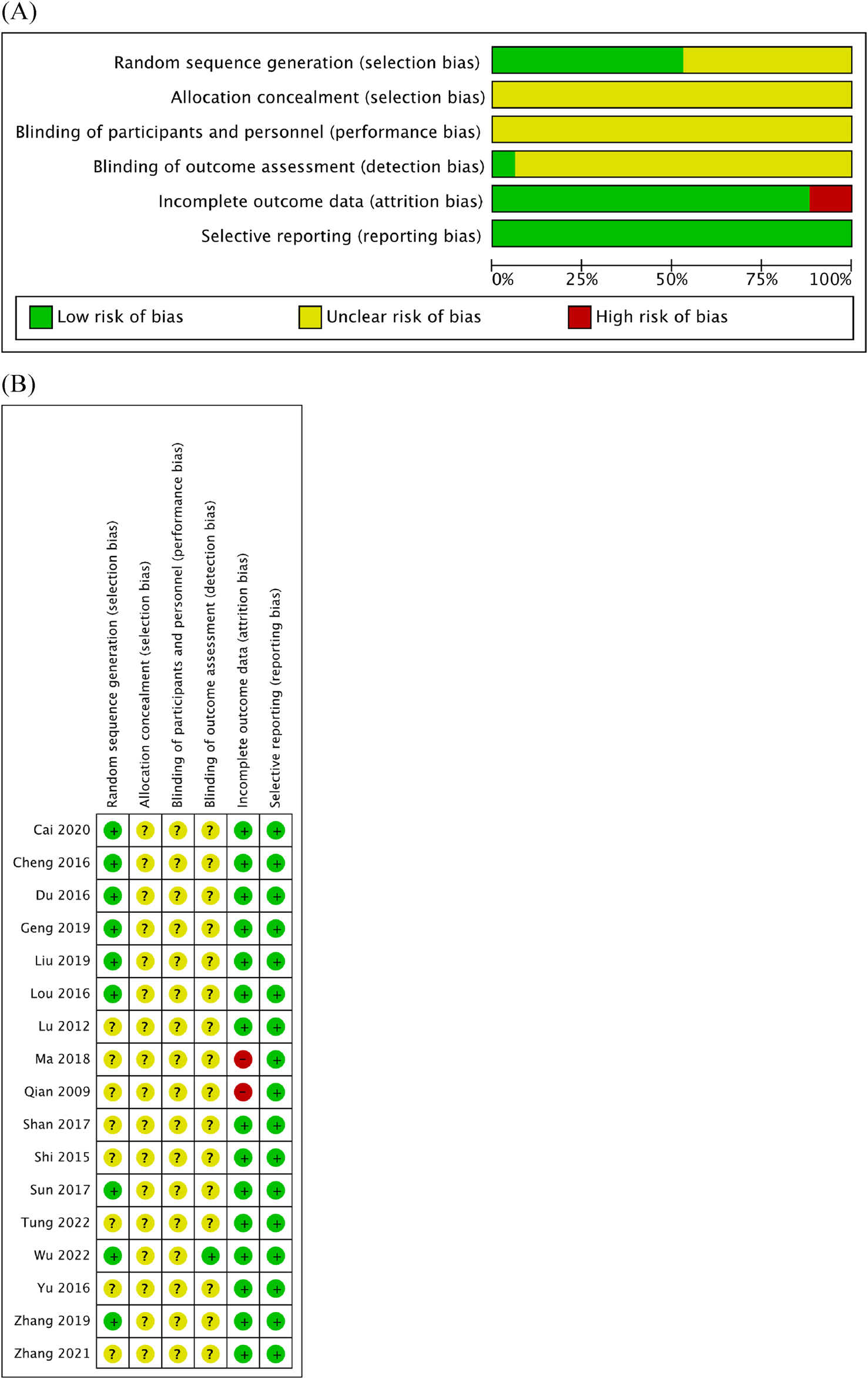

3.3 Quality of trials

Quality assessment was performed using Cochrane RoB (Figures 2A, B). Within the RoB assessment, most studies displayed unclear statuses of allocation bias, performance bias, and detection bias. Evaluation of the selection bias indicated that nine of the RCTs included in this analysis were at a low RoB, while the status of others remained unclear. Similarly, the risk of attrition bias was low across the majority of RCTs, except for two studies that were linked to high risk. Notably, all studies were rated as having a low risk of reporting bias.

FIGURE 2

Quality assessment of 17 included studies using the RoB assessment tool established by the Cochrane Collaboration. (A) RoB graph. (B) RoB summary.

3.4 Meta-analysis of included studies

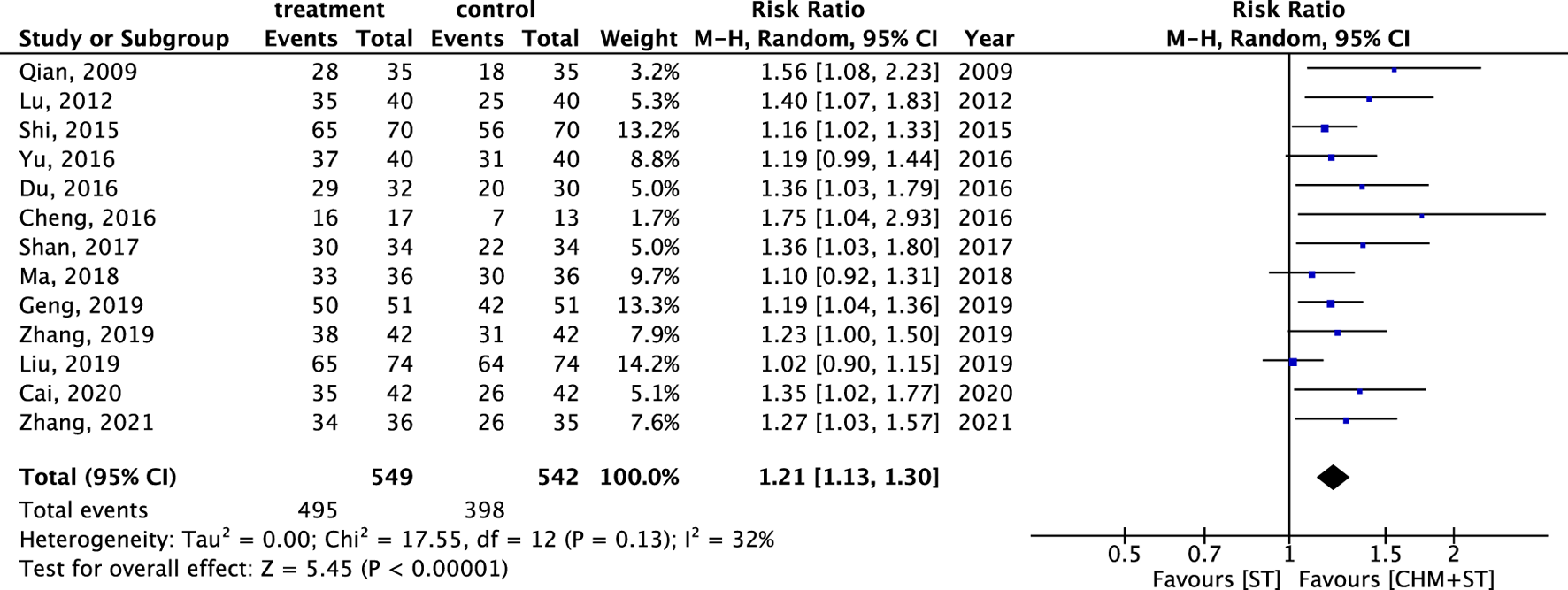

3.4.1 Primary outcome: the RR of achieving prominent improvement in ER

Generally, the CHM + ST group had better outcomes than the ST group. In 13 RCTs analyzed, the CHM + ST group had a superior proportion of participants with prominent improvement (495/549, 90.16%) compared with the ST group (398/542, 73.43%). The CHM + ST group demonstrated a 21% higher proportion of prominent improvement compared with the ST groups (RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.13–1.30, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 32%) (Figure 3). Moreover, the TSA confirmed this result, and the total pooled case number (n = 1,091) achieved the threshold of 90% statistical examination power (n = 310) (Supplementary Appendix S4).

FIGURE 3

Forest plot of meta-analysis comparing CHM + ST with ST in terms of ER.

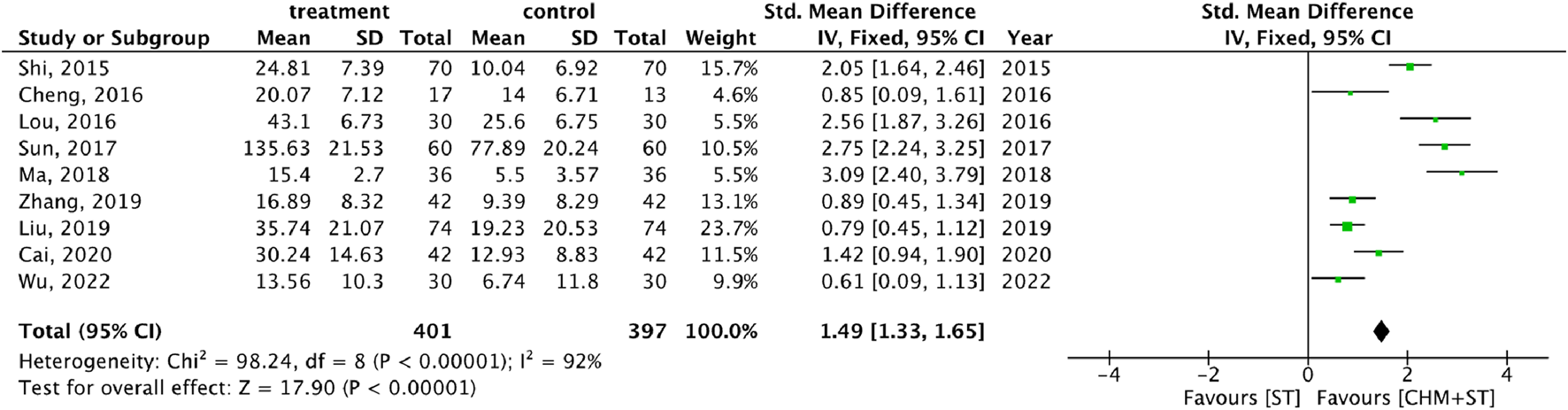

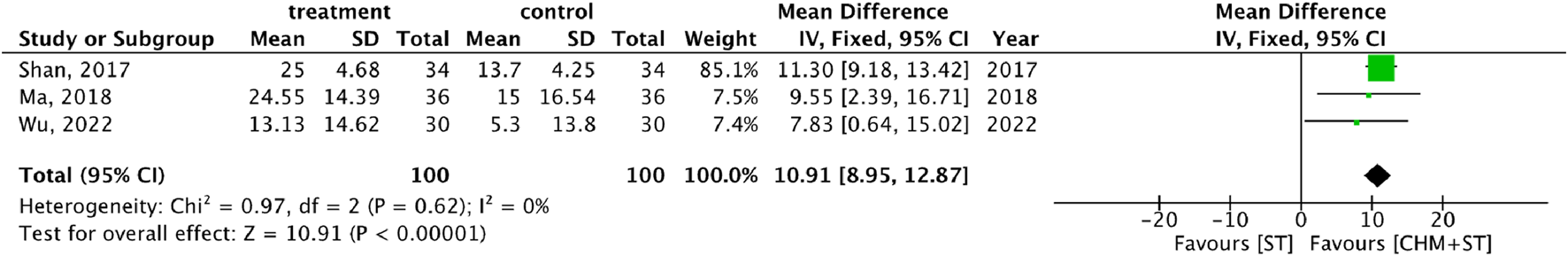

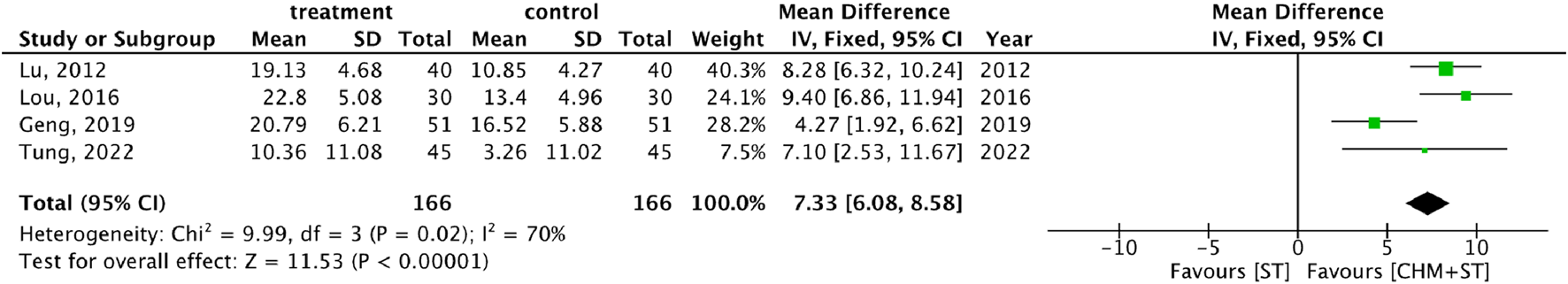

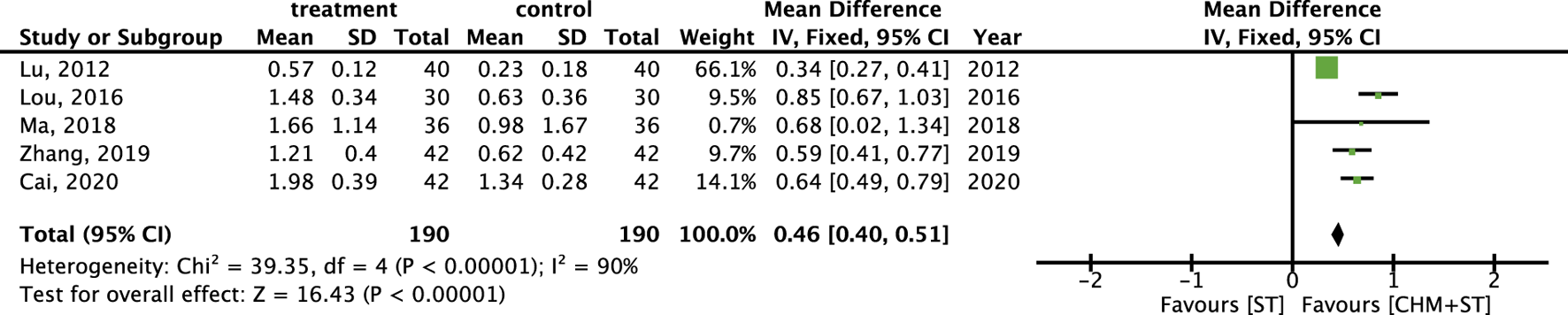

3.4.2 Secondary outcome: improvement of Gesell, GMFM, ADL, and MAS scores

More than half of the studies used GMFM (n = 9) to measure motor function disorder. The mean of improvement of GMFM scores of the intervention and control groups ranged from 13.56 (minimum)–135.63 (maximum) and 5.5 (minimum)–77.89 (maximum), respectively. The pooled analysis revealed a significantly better improvement in the GMFM score in the CHM + ST group versus the ST group (SMD: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.33–1.65, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 92%) (Figure 4). Three RCTs were included in the Gesell analysis. The CHM + ST group exhibited a more significant change in scores compared to the ST group (MD: 10.91; 95% CI: 8.95–12.87, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 0%) (Figure 5). Four studies reported the improvement of daily living function using the ADL score. Greater ADL improvement was noted in the CHM + ST group compared with the ST group (MD: 7.33; 95% CI: 6.08–8.58, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 70%) (Figure 6). Five studies were included in the MAS analysis. Greater MAS improvement was recorded in the CHM + ST group versus the ST group (MD: 0.46; 95% CI: 0.40–0.51, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 90%) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 4

Forest plot of meta-analysis comparing CHM + ST with ST in terms of improvement of GMFM score change from the baseline.

FIGURE 5

Meta-analysis comparing CHM + ST with ST in terms of Gesell Developmental Schedule improvement from baseline.

FIGURE 6

Meta-analysis comparing CHM + ST with ST in terms of improvement of ADL score from baseline.

FIGURE 7

Meta-analysis comparing CHM + ST with ST in terms of improvement of MAS level from baseline.

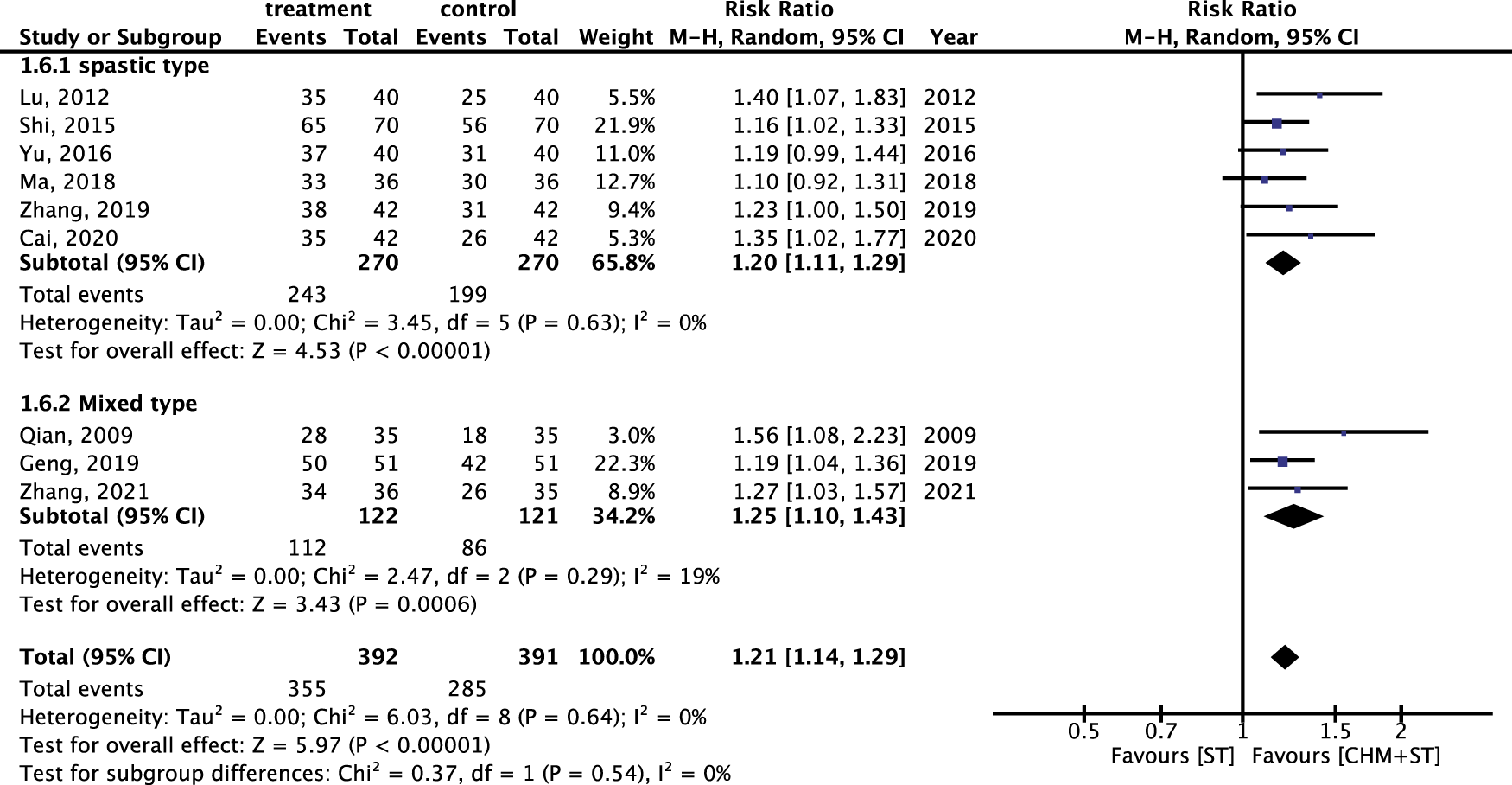

3.5 Subgroup meta-analysis

Within different subtypes of CP, durations, and degrees of severity, the subgroup analysis showed lower heterogeneity with consistent results. For both spastic (n = 540) and mixed types (n = 243) of CP, the CHM + ST group had a significantly higher proportion of prominent improvement in ER compared with the ST group (RR: 1.20, 95% CI: 1.11–1.29, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 0% vs. RR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.10–1.43, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 19%) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8

Subgroup analysis of RCTs. Comparison of spastic type with mixed type CP based on improvement in the ER.

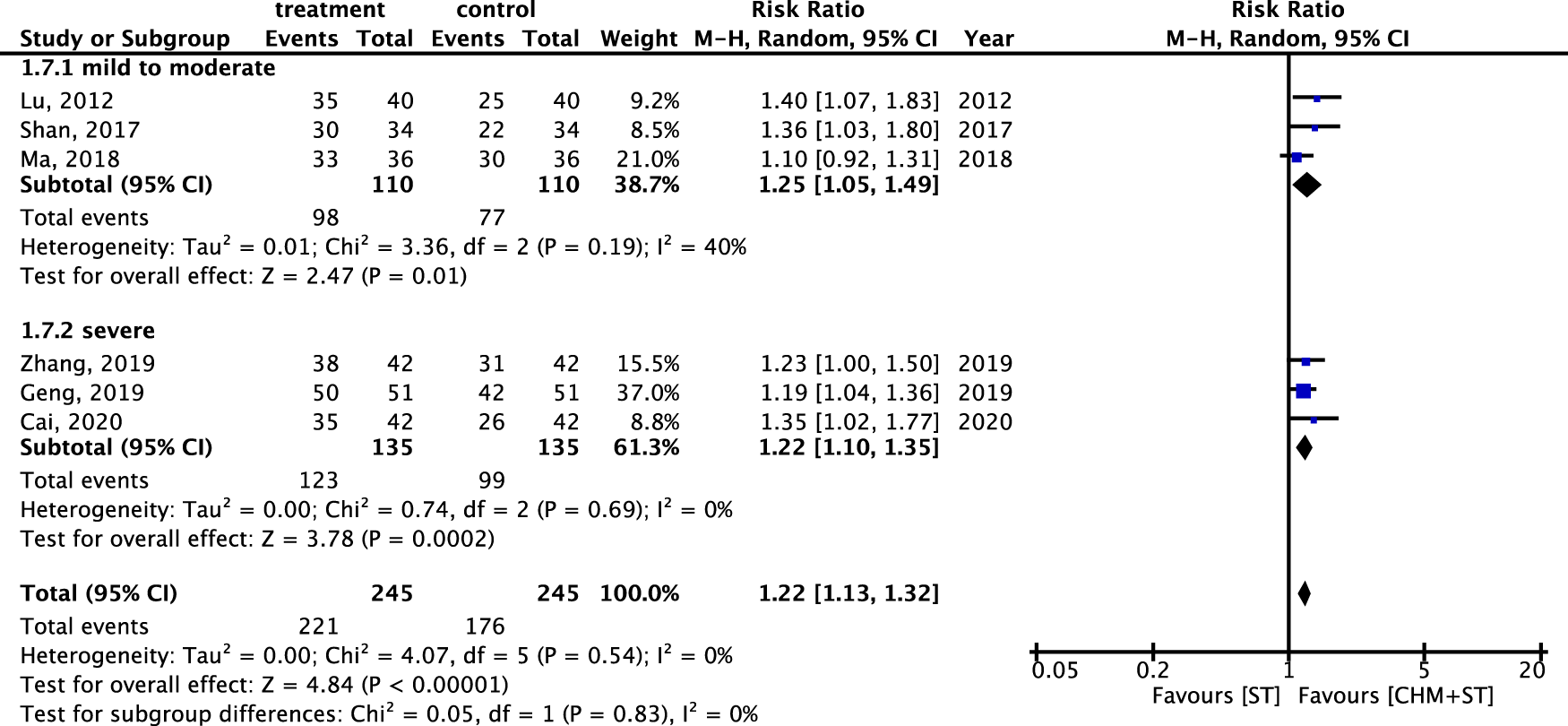

The RR of ER within different degrees of CP severity was also analyzed. Six studies were analyzed after screening. In both categories, there was a notable enhancement in ER in the CHM + ST group versus the ST group. In addition, the mild-to-moderate subgroup (n = 220, RR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.05–1.49, p-value = 0.001, I2 = 40%) exhibited better improvement than the severe subgroup (n = 270, RR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.10–1.35, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 0%) (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9

Meta-analysis of ER under subgroups for different degrees of CP severity.

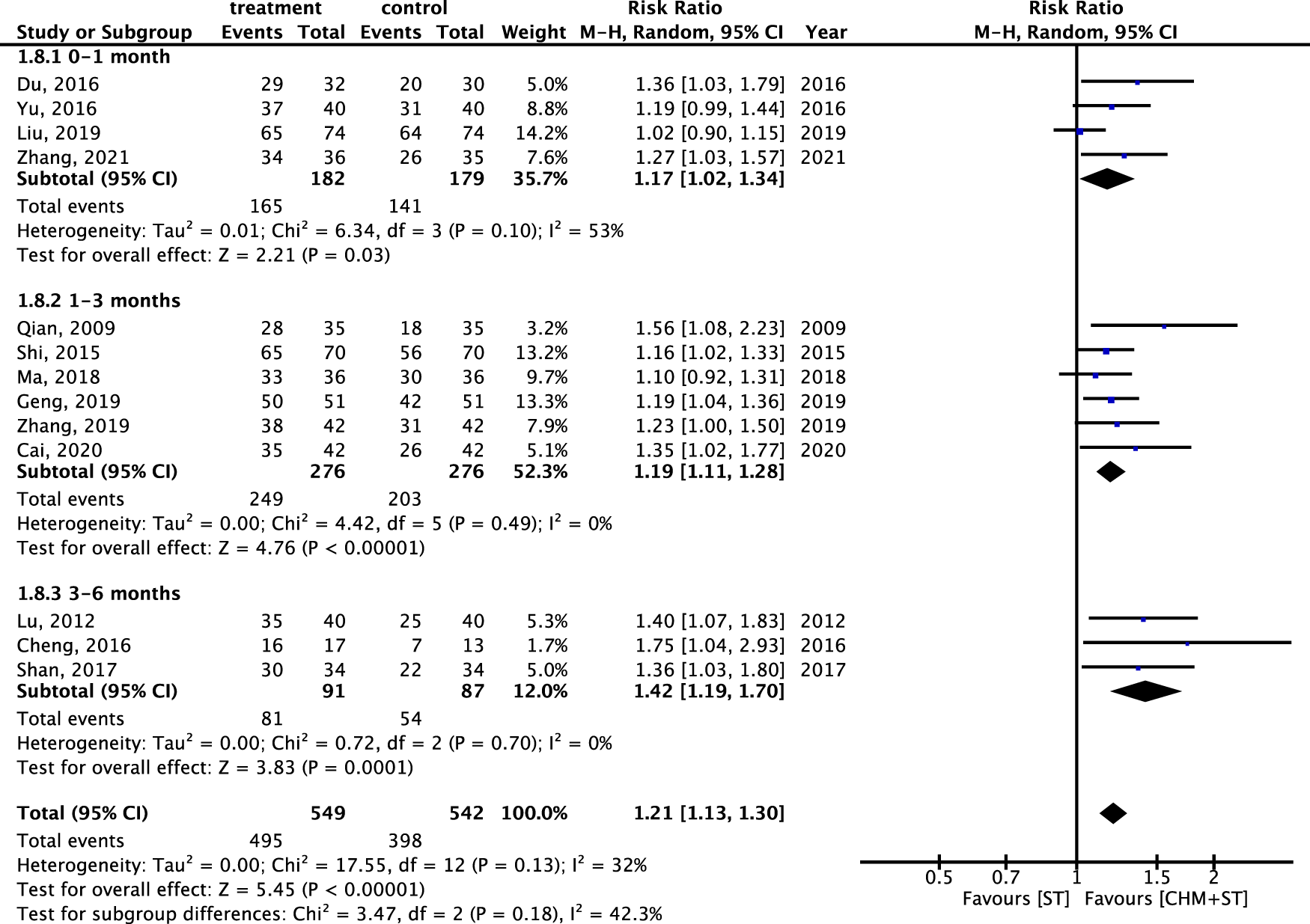

Furthermore, regarding the duration of the treatment course, the CHM + ST group also showed better results compared with the ST group. Patients receiving treatment for 3–6 months (n = 178, RR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.19–1.70, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 0%) showed the greatest improvement, followed by those treated for 1–3 months (n = 552, RR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.11–1.28, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 0%), and 0–1 month (n = 361, RR: 1.17, 95% CI: 1.02–1.34, p-value = 0.03, I2 = 53%) (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10

Meta-analysis of ER under subgroups for different durations of treatment.

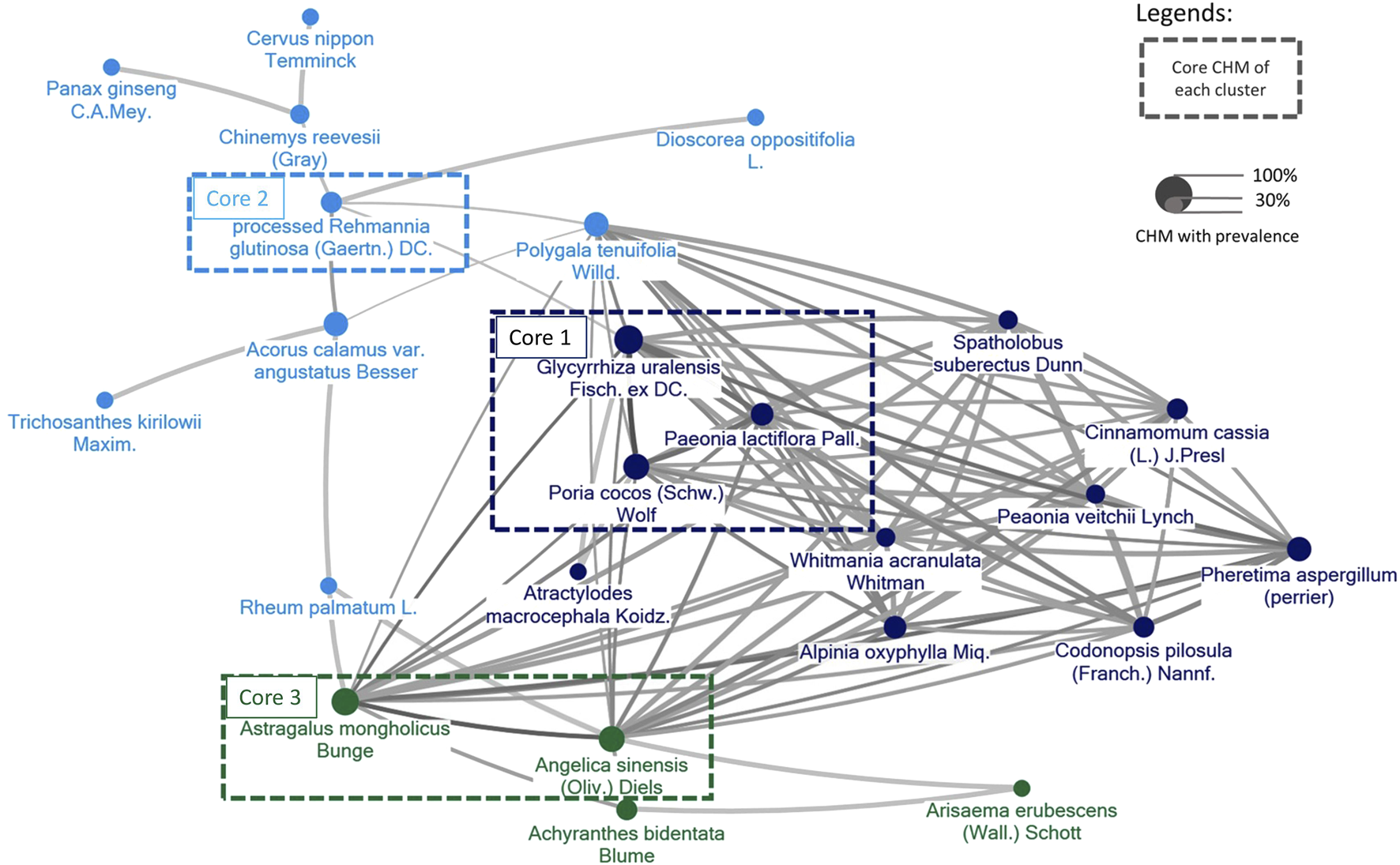

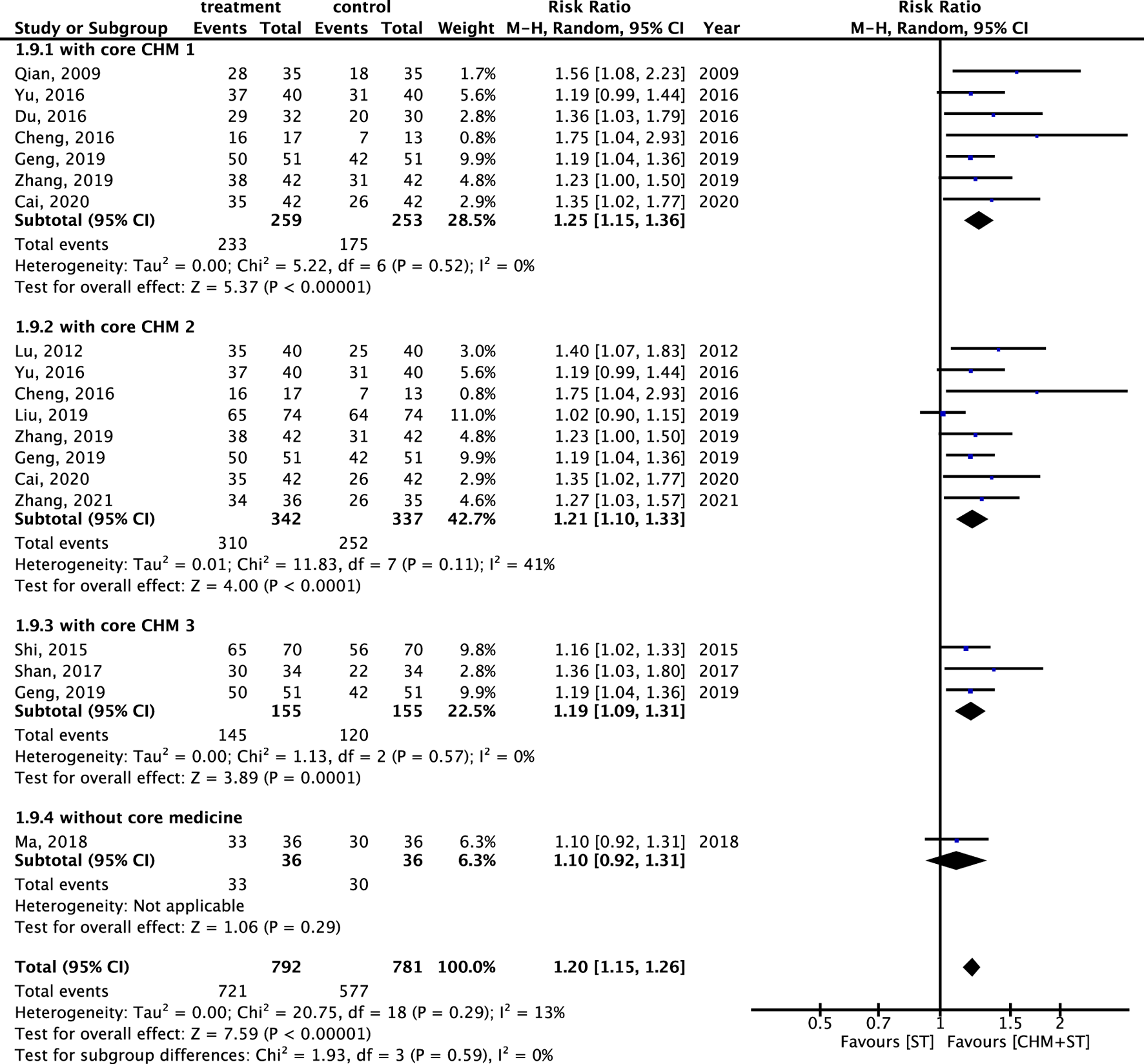

3.6 CMN for CP obtained from the included trials

The components of CHMs in each included study were itemized in Supplementary Appendix S5. The prevalence of CHM applied was presented in order in Supplementary Appendix S6. CMN could be constructed based on these CHM connections and present as Figure 11. Among these, three sets of core CHMs were found, i.e., core CHM1: GU, PC, and Paeonia lactiflora Pall. (PL); core CHM2: Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. (RG) (present in 29% of all studies); and core CHM3: Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) (AS) and Astragalus mongholicus Bunge (AM). Compared with CHM + WM that did not include core medicines, CHM + WM including the three aforementioned sets of core CHMs exhibited better effectiveness (core CHM1, n = 512, RR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15–1.36, p-value < 0.001; core CHM2, n = 679, RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.10–1.33, p-value < 0.001; core CHM3, n = 310, RR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.09–1.31, p-value < 0.001; without core medicine, n = 72, RR: 1.10, 95% CI: 0.92–1.31, p-value = 0.29) (Figure 12).

FIGURE 11

The CMN for CP was derived from the trials included in the study. Colors assigned to each node (agent) represent distinct clusters of CHM, with higher prevalence represented by larger node sizes. Darker colors and thicker connecting lines signify a more pronounced and frequent mixture of two CHMs.

FIGURE 12

Subgroup analysis of RCTs. Comparison of the effects of three clusters of core medicines on the improvement of ER.

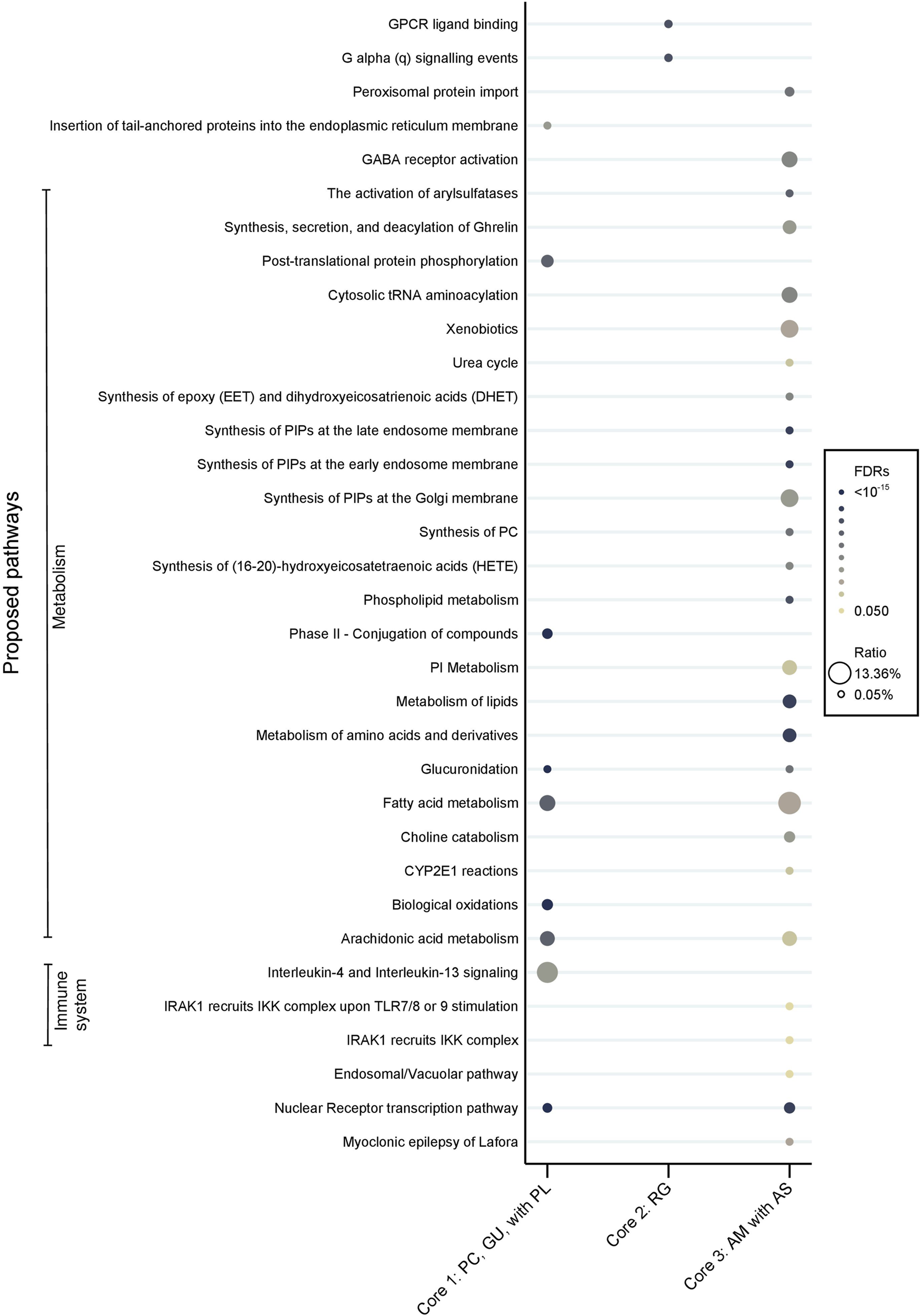

Moreover, noticeable disparities were observed in the proposed pharmacological pathways between the core CHMs (Figure 13). In terms of the immune system, core CHM1 (PC, GU, and PL) acted on Interleukin 4 (IL4) and Interleukin 13 (IL13) signaling. Additionally, core CHM3 (AS and AM) played a crucial role in modulating the activation of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor. Moreover, with regard to metabolism pathways, cores CHM1 and CHM3 demonstrated multiple advantages, particularly in aspects of arachidonic acid metabolism.

FIGURE 13

Pharmacologic pathways of CHM. Core 1: PC, GU, with PL; Core 2: RG; Core 3: AM with AS. (PC, Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf; GU, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC.; PL, Paeonia lactiflora Pall.; RG, processed Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.; AM, Astragalus mongholicus Bunge; AS, Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels.

3.7 Publication bias

The funnel plots exhibited a low risk of publication bias (Supplementary Appendix S7). Moreover, the corrected results using Trim and Fill approach remained significant (Effective size 1.170, 95% CI: 1.084–1.256) (Supplementary Appendix S8).

3.8 Adverse drug events (ADEs) of CHM

Of the 17 included studies, only five reported side effects. In one study, side effects were only observed in the control group. The remaining four studies described that the patients treated with CHM + ST experienced side effects, such as gastrointestinal discomfort (i.e., nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea), although of no significance in comparison to the ST group. Moreover, there were no significant changes in liver and renal function in the CHM groups.

4 Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis for pediatric CP involving core CHM exploration and TSA. In all studies, we found the use of oral CHM in combine with ST led to a significantly higher proportion of patients achieving prominent improvement in ER compared with control. Improvements in motor skills, developmental status, self-care abilities, and muscle rigidity were consistently observed. In addition, the ER was higher for CHM + ST versus ST regardless of the type or severity of CP. Additionally, our meta-analysis showed that a longer duration of treatment is associated with better results. Regarding prescriptions, various types of CHM were used in the studies as other meta-analyses of CHMs (Wieland et al., 2013; Chung et al., 2015). Through the CMN, it was possible to efficiently identify the potential core CHMs for pediatric CP.

Recent advances in the treatment of CP include numerous methods, such as hyperbaric oxygen (Laureau et al., 2022), stem cell therapy (Novak et al., 2023), virtual reality rehabilitation (Han and Park, 2023), and robot-assisted devices (Vezér et al., 2024; Conner et al., 2022), which are currently under investigation. However, pharmacological options for CP remain limited. For children with CP, early intervention is more beneficial, as it minimizes the potential impact of muscle tension and poor posture on motor skills, thereby preventing hindrances in daily activities (Bobath, 1967). Therefore, CHM could be used as a complementary therapy with a good safety profile. Additionally, according to our results, incorporating the use of CHM for 1 month can lead to noticeable improvements in CP syndromes. Moreover, continuing combined therapy for 3–6 months seems appropriate, as supported by the subgroup analysis conducted in this study. CHMs might not only have the effect of muscle relax like WM, but also the effect of motor function and developmental status improvement.

CP is caused by disturbance or injury to the developing brain, often as a consequence of hypoxia, infection, stroke, or hypotension; the subsequent inflammatory cascade follows the original insult (Wimalasundera and Stevenson, 2016). Recent studies found higher levels of inflammatory markers in infants and children with CP, which might have a relationship between inflammation and neural damage at the perinatal period and during development of children (Paton et al., 2022; Magalhães et al., 2019; Malaeb and Dammann, 2009; Bashiri et al., 2006). Increased of cytokine IL-4 and IL-13 in CP patient were mentioned in some studies and were thought to have relationship with neural injury (Than et al., 2023; Djukic et al., 2009; Kaukola et al., 2004). And arachidonic acid, which might activate neuroinflammatory response and overproduction of proinflammatory cytokine, might lead to the serious of white matter damage and CP development as a consequence (Kapitanović Vidak et al., 2017; Chun et al., 2015; Strickland, 2014). Therefore, there is a growing interest in neuroprotective effect in CP through anti-inflammatory agent (Salomon, 2024; Mallah et al., 2020). Based on the current hypothesis and our findings on the anti-inflammatory effects of CHM, core CHM1 (PC, PL, GU) can modulate IL4 and IL13, while cores CHM1 and CHM3 (PC, PL, GU, AS, AM) are related to the arachidonic acid pathway. Previous studies also revealed that all these agents possess anti-inflammatory properties (Li et al., 2022; Wu J et al., 2022; He and Dai, 2011; Li et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2022), which may have benefit in reducing nerve damage caused by inflammation.

As to core CHM2 (RG), catalpol is one of the active ingredients in RG; it exerts a neuroprotective effect against hypoxic/ischemic injury by inhibiting apoptosis and regulating Aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression (Jiang et al., 2015; Zhang Y et al., 2019). Besides, catalpol can promote angiogenesis via enhancing vascular endothelial growth factor-phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/protein kinase B (VEGF-PI3K/AKT) and VEGF- Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1/2/extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (VEGF-MEK1/2/ERK1/2) signaling (Wang et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022). Moreover, rehmannioside A, which is derived from RG, has neuroprotection effects and improves cognitive impairment by inhibiting ferroptosis and activating the PI3K/AKT/Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2) and solute carrier family 7 member 11/glutathione peroxidase 4 (SLC7A11/GPX4) signaling pathway (Fu et al., 2022). Additionally, catalpol and mannitol, which are two components of RG, have anticonvulsant effects via GABAA receptor regulation (Kim et al., 2020).

In our study, we found that core CHM3 (AS and AM) played a crucial role in modulating GABA receptor activation and arachidonic acid metabolism. Previous studies showed that AM and AS upregulated VEGF expression to modulate the function of capillaries (Song et al., 2009). Gelispirolide and riligustilide, which are two phthalide dimmers isolated from AS, exert a GABAergic effect to relax spastic muscle (Deng et al., 2006). Besides, previous studies have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory effects of AS and AM (Li et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2022). Collectively, the available evidence indicates that the combination of CHM with conventional therapy may bring more advantages for patients with CP.

The safety of treatment using CHM was assessed by analyzing reported adverse reactions. Only mild side effects, such as gastrointestinal discomfort (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea), were reported, without significant differences compared with the ST group. Furthermore, commonly used WM, such as baclofen, may cause central nervous system adverse reactions (e.g., confusion, dizziness, drowsiness, sedation, and asthenia) (Alstermark et al., 2008). Diazepam and clonazepam may be associated with side effects including sedation, cognitive impairment, amnesia, and ataxia (Vinkers and Olivier, 2012). Botulinum toxin injections lead to muscle atrophy and muscle weakness (Kaya Keles and Ates, 2022). Unlike WM, CHM does not cause drowsiness or muscle weakness; furthermore, it does not affect the daily life and rehabilitation schedule of children with CP.

5 Limitations

There are some limitations in this study. Firstly, there was a high heterogeneity observed in the results for the GMFM, ADL, and MAS scores. This heterogeneity may be due to the various types of CHM used. Therefore, we presented the core medicine network for CP to simplify the intervention and eliminate the diversity for future clinical trials. Secondly, although selection, attrition, and reporting biases were low, the allocation and performance biases were mostly unclear. Common sources of biases included uncertain concealment, lack of a specific blinding process, and randomization. Consequently, there is a need for high-quality clinical trials with improved designs. Thirdly, the generalizability of the present findings is poor. All studies included in this analysis were conducted in China; hence, the ethnic diversity is limited. These studies did not include participants from Caucasian, African, or Hispanic populations. Fourthly, the sample size in the included trials was comparatively modest (Sakpal, 2010). Therefore, we used TSA to confirm the results in this meta-analysis, which achieved the threshold of 90% statistical examination power. Fifthly, the hypothesis that CHM could improve CP through anti-inflammatory effects remains speculative. There was evidence supporting that CHM had anti-inflammatory properties and that inflammation can be mitigated in CP, but direct evidence is lacking. Therefore, larger CHM related RCTs with inflammatory biomarker analysis was needed to detail the mechanistic aspects and the relationship with CP.

6 Conclusion

CHM has the potential to treat pediatric CP in terms of improving motor function, developmental status, daily living function, and spasticity, as well as avoiding the occurrence of serious ADEs. We also identified core medications for treating CP and possible drug action pathways for reference in future clinical use. Subgroup analysis revealed that the combination of CHM with conventional treatment demonstrated better efficacy when core CHMs were included, the treatment duration was extended, or when patients had mild-to-moderate baseline severity. However, the included studies exhibited considerable biases over allocation and performance, high level of heterogeneity, poor generalizability, small sample size in the analysis. Therefore, further rigorous, multicenter, larger, and high-quality research is warranted.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Y-YH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing–original draft. Y-YC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing–original draft. H-YC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Supervision, Writing–review and editing. R-HF: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing. Y-JC: Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing–review and editing. T-HY: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology in Taiwan (MOST111-2320-B-182-035-MY3), and the Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW112-CMAP-M-113-000006-D).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1500095/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

- 6MWT

6-minute walking test

- ADEs

Adverse drug events

- ADL

Activities of Daily Living for CP recover evaluation

- AKT

Protein kinase B

- AM

Astragalus mongholicus Bunge

- AQP4

Aquaporin-4

- AS

Angelica sinensis (Oliv.)

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- Berg

Berg Balance Scale

- CHM

Chinese herbal medicine

- CI

Confidence interval

- CMN

Chinese herbal medicine network

- CNKI

China National Knowledge Infrastructure

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CP

Cerebral palsy

- ER

Effectiveness rate

- ERK1/2

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2

- ET-1

Endothelin-1

- FAC

Functional ambulation category scale

- FDA

Frenchay Dysarthria Assessment

- FES

Functional electrical stimulation

- FMA

Fugl–Meyer assessment scale

- FMFM

Fine motor function measure

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- Gesell

Gesell Developmental Scale

- GMFM

Gross Motor Function Measure score

- GPX4

Glutathione peroxidase 4

- GU

Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC.

- IFN-α

Interferon-α

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor 1

- IL13

Interleukin 13

- IL4

Interleukin 4

- M:F

Male:Female

- MAS

Modified Ashworth Scale

- MD

Mean difference

- MDI

Mental Developmental Index

- MEK1/2

Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 1/2

- MWS

Maximum walking speed

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2

- NSE

Neuron specific enolase

- OT

Occupational therapy

- PC

Poria cocos (Schw.) Wolf.

- PDI

Psychomotor Development Index

- PDMS-2

Peabody developmental motor scale-2

- PedsQL

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase

- PL

Paeonia lactiflora Pall.

- PT

Physical therapy

- RCT

Randomized clinical trial

- RG

Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC.

- RoB

Risk-of-bias

- RR

Risk ratio

- SD

Standard deviation

- SLC7A11

Solute carrier family 7 member 11

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

- SPR

Selective posterior rhizotomy

- ST

Standard treatment

- TCM

Traditional Chinese medicine

- TDS

Teacher’s Drooling Scale

- TGF-β1

Transforming growth factor-beta 1

- TSA

Trial sequential analysis

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- WeeFIM

Wee Functional Independence Measure for Children

- WISC

Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children

- WM

Western medicine

References

1

Alstermark C. Amin K. Dinn S. R. Elebring T. Fjellström O. Fitzpatrick K. et al (2008). Synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of novel gamma-aminobutyric acid type B (GABAB) receptor agonists as gastroesophageal reflux inhibitors. J. Med. Chem.51, 4315–4320. 10.1021/jm701425k

2

Bashiri A. Burstein E. Mazor M. (2006). Cerebral palsy and fetal inflammatory response syndrome: a review. J. Perinat. Med.34, 5–12. 10.1515/JPM.2006.001

3

Bekteshi S. Monbaliu E. McIntyre S. Saloojee G. Hilberink S. R. Tatishvili N. et al (2023). Towards functional improvement of motor disorders associated with cerebral palsy. Lancet Neurol.22, 229–243. 10.1016/S1474-4422(23)00004-2

4

Bobath B. (1967). The very early treatment of cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol.9, 373–390. 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1967.tb02290.x

5

Boecker A. H. Lukhaup L. Aman M. Bergmeister K. Schwarz D. Bendszus M. et al (2022). Evaluation of MR-neurography in diagnosis and treatment in peripheral nerve surgery of the upper extremity: a matched cohort study. Microsurgery42, 160–169. 10.1002/micr.30846

6

Cai M. (2020). Clinical observation on 42 cases of children with spastic cerebral palsy treated by Huangqi Guizhi Wuwu Tang combined with functional electrical stimulation. J. Pediatr. Traditional Chin. Med.16, 73–76. 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2020.02.22

7

Chen H. Y. Lin Y. H. Huang J. W. Chen Y. C. (2015). Chinese herbal medicine network and core treatments for allergic skin diseases: implications from a nationwide database. J. Ethnopharmacol.168, 260–267. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.04.002

8

Chen Z. Huang Z. Li X. Deng W. Gao M. Jin M. et al (2023). Effects of traditional Chinese medicine combined with modern rehabilitation therapies on motor function in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Neurosci.17, 1097477. 10.3389/fnins.2023.1097477

9

Cheng W. Zhang Z. Feng K. Cai Z. Li A. Lu Y. (2016). Effect observation of child cerebral palsy gross movement disorders treated with high dose of Astragalus mongholicus. Lishizhen Med. Materia Medica Res.27, 2192–2194. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-0805.2016.09.050

10

Chun P. T. McPherson R. J. Marney L. C. Zangeneh S. Z. Parsons B. A. Shojaie A. et al (2015). Serial plasma metabolites following hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in a nonhuman primate model. Dev. Neurosci.37, 161–171. 10.1159/000370147

11

Chung V. C. Ho R. S. Wu X. Fung D. H. Lai X. Wu J. C. et al (2015). Are meta-analyses of Chinese herbal medicine trials trustworthy and clinically applicable? a cross-sectional study. J. Ethnopharmacol.162, 47–54. 10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.028

12

Colver A. Fairhurst C. Pharoah P. O. (2014). Cerebral palsy. Lancet383, 1240–1249. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61835-8

13

Conner B. C. Remec N. M. Lerner Z. F. (2022). Is robotic gait training effective for individuals with cerebral palsy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Rehabil.36, 873–882. 10.1177/02692155221087084

14

De Cassai A. Tassone M. Geraldini F. Sergi M. Sella N. Boscolo A. et al (2021). Explanation of trial sequential analysis: using a post-hoc analysis of meta-analyses published in Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. Korean J. Anesthesiol.74, 383–393. 10.4097/kja.21218

15

Demont A. Gedda M. Lager C. de Lattre C. Gary Y. Keroulle E. et al (2022). Evidence-Based, implementable motor rehabilitation guidelines for individuals with cerebral palsy. Neurology99, 283–297. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200936

16

Deng S. Chen S. N. Lu J. Wang Z. J. Nikolic D. van Breemen R. B. et al (2006). GABAergic phthalide dimers from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels. Phytochem. Anal.17, 398–405. 10.1002/pca.937

17

Djukic M. Gibson C. S. Maclennan A. H. Goldwater P. N. Haan E. A. McMichael G. et al (2009). Genetic susceptibility to viral exposure may increase the risk of cerebral palsy. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol.49, 247–253. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.00999.x

18

Du X. Zheng G. Feng B. Ma B. (2016). Clinical research of modified suanzaoren granule in treating sleep disorders of cerebral palsy. Guangming J. Chin. Med.31, 1576–1577. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2016.11.026

19

Fu C. Wu Y. Liu S. Luo C. Lu Y. Liu M. et al (2022). Rehmannioside A improves cognitive impairment and alleviates ferroptosis via activating PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 and SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway after ischemia. J. Ethnopharmacol.289, 115021. 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115021

20

Gao Z. Pang Z. Chen Y. Lei G. Zhu S. Li G. et al (2022). Restoring after central nervous system injuries: neural mechanisms and translational applications of motor recovery. Neurosci. Bull.38, 1569–1587. 10.1007/s12264-022-00959-x

21

Geng L. (2019). The efficacy of Xingnao Kaiqiao decoction combined with acupuncture in the treatment of cerebral palsy and its impact on children’s movement and daily living abilities. Shaanxi J. Traditional Chin. Med.40, 664–666. 10.3969/j.issn.1000-7369.2019.05.035

22

Gong F. Qu R. Li Y. Lv Y. Dai J. (2022). Astragalus Mongholicus: a review of its anti-fibrosis properties. Front. Pharmacol.13, 976561. 10.3389/fphar.2022.976561

23

Han Y. Park S. (2023). Effectiveness of virtual reality on activities of daily living in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ11, e15964. 10.7717/peerj.15964

24

He D. Y. Dai S. M. (2011). Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of paeonia lactiflora pall, a traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Front. Pharmacol.2, 10. 10.3389/fphar.2011.00010

25

Higgins J. P. Altman D. G. Gøtzsche P. C. Jüni P. Moher D. Oxman A. D. et al (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ343, d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928

26

Huifang Y. (2012). A study on the correlation between work-related stress and perceived health status among home care providers. Chin. J. Occup. Med.19, 135–145.

27

Jiang B. Shen R. F. Bi J. Tian X. S. Hinchliffe T. Xia Y. (2015). Catalpol: a potential therapeutic for neurodegenerative diseases. Curr. Med. Chem.22, 1278–1291. 10.2174/0929867322666150114151720

28

Kang H. (2021). Trial sequential analysis: novel approach for meta-analysis. Anesth. Pain Med. Seoul.16, 138–150. 10.17085/apm.21038

29

Kapitanović Vidak H. Catela Ivković T. Vidak Z. Kapitanović S. (2017). COX-1 and COX-2 polymorphisms in susceptibility to cerebral palsy in very preterm infants. Mol. Neurobiol.54, 930–938. 10.1007/s12035-016-9713-9

30

Kaukola T. Satyaraj E. Patel D. D. Tchernev V. T. Grimwade B. G. Kingsmore S. F. et al (2004). Cerebral palsy is characterized by protein mediators in cord serum. Ann. Neurol.55, 186–194. 10.1002/ana.10809

31

Kaya Keles C. S. Ates F. (2022). Botulinum toxin intervention in cerebral palsy-induced spasticity management: projected and contradictory effects on skeletal muscles. Toxins (Basel)14, 772. 10.3390/toxins14110772

32

Kim M. Acharya S. Botanas C. J. Custodio R. J. Lee H. J. Sayson L. V. et al (2020). Catalpol and mannitol, two components of Rehmannia glutinosa, exhibit anticonvulsant effects probably via GABA(A) receptor regulation. Biomol. Ther. Seoul.28, 137–144. 10.4062/biomolther.2019.130

33

Lan G. DeMets D. L. (1983). Discrete sequential boundaries for clinical trials. Biometrika70, 659–663. 10.2307/2336502

34

Laureau J. Pons C. Letellier G. Gross R. (2022). Hyperbaric oxygen in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review of effectiveness and safety. PLoS One17, e0276126. 10.1371/journal.pone.0276126

35

Lee B. Kwon C. Y. Chang G. T. (2018). Oriental herbal medicine for neurological disorders in children: an overview of systematic reviews. Am. J. Chin. Med.46, 1701–1726. 10.1142/S0192415X18500866

36

Li M. M. Zhang Y. Wu J. Wang K. P. (2020). Polysaccharide from Angelica sinensis suppresses inflammation and reverses anemia in complete Freund’s adjuvant-induced rats. Curr. Med. Sci.40, 265–274. 10.1007/s11596-020-2183-3

37

Li M. T. Xie L. Jiang H. M. Huang Q. Tong R. S. Li X. et al (2022). Role of licochalcone A in potential pharmacological therapy: a review. Front. Pharmacol.13, 878776. 10.3389/fphar.2022.878776

38

Liang X. Tan Z. Yun G. Cao J. Wang J. Liu Q. et al (2021). Effectiveness of exercise interventions for children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Rehabil. Med.53, jrm00176. 10.2340/16501977-2772

39

Liao H. H. Yen H. R. Muo C. H. Lee Y. C. Wu M. Y. Chou L. W. et al (2017). Complementary traditional Chinese medicine use in Children with cerebral palsy: a nationwide retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. BMC Complementary Altern. Med.17, 155. 10.1186/s12906-017-1668-5

40

Liu Y. Dong H. (2019). Clinical study of massaging acupuncture points in head combined with kaiqiao xingshen decoction in treatment of motor and language dysfunction in children with cerebral palsy. Liaoning J. Traditional Chin. Med.46, 611–614. 10.13192/j.issn.1000-1719.2019.03.050

41

Lou Y. Shi H. (2016). Observing the clinical efficacy of pastic cerebral palsy with Shujinhuoluo Wan. Pharmacol. Clin. Chin. Materia Medica32, 185–188. 10.13412/j.cnki.zyyl.2016.03.054

42

Lu C. Zhou S. Guo G. (2012). Clinical effect of Shenluqizhi decoction on patients with spastic cerebral palsy. Hebei J. Tradit. Chin. Med.34, 21–23.

43

Lu Y. C. Tseng L. W. Huang Y. C. Yang C. W. Chen Y.-C. Chen H.-Y. (2022). The potential complementary role of using Chinese herbal medicine with western medicine in treating COVID-19 patients: pharmacology network analysis. Pharmaceuticals15, 794. 10.3390/ph15070794

44

Ma B. Zhang J. F. Chen T. Zheng H. (2018). Clinical observation on the effect of Pujin Keli in adjunctive treating of 34 cases of children with spastic cerebral palsy caused by phlegm and blood retention in head. J. Pediatr. Tradit. Chin. Med.14, 26–30. 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2018.03.08

45

Magalhães R. C. Moreira J. M. Lauar A. O. da Silva A. A. S. Teixeira A. L. Silva E. (2019). Inflammatory biomarkers in children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Res. Dev. Disabil.95, 103508. 10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103508

46

Malaeb S. Dammann O. (2009). Fetal inflammatory response and brain injury in the preterm newborn. J. Child. Neurol.24, 1119–1126. 10.1177/0883073809338066

47

Mallah K. Couch C. Borucki D. M. Toutonji A. Alshareef M. Tomlinson S. (2020). Anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective agents in clinical trials for CNS disease and injury: where do we go from here?Front. Immunol.11, 2021. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02021

48

McIntyre S. Goldsmith S. Webb A. Ehlinger V. Hollung S. J. McConnell K. et al (2022). Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic analysis. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol.64, 1494–1506. 10.1111/dmcn.15346

49

Novak I. Hines M. Goldsmith S. Barclay R. (2012). Clinical prognostic messages from a systematic review on cerebral palsy. Pediatrics130, e1285–e1312. 10.1542/peds.2012-0924

50

Novak I. Paton M. C. Griffin A. R. Jackman M. Blatch-Williams R. K. Finch-Edmondson M. (2023). The potential of cell therapies for cerebral palsy: where are we today?Expert Rev. Neurother.23, 673–675. 10.1080/14737175.2023.2234642

51

Paton M. C. B. Finch-Edmondson M. Dale R. C. Fahey M. C. Nold-Petry C. A. Nold M. F. et al (2022). Persistent inflammation in cerebral palsy: pathogenic mediator or comorbidity? a scoping review. J. Clin. Med.11, 7368. 10.3390/jcm11247368

52

Paul S. Nahar A. Bhagawati M. Kunwar A. J. (2022). A review on recent advances of cerebral palsy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev.2022, 2622310. 10.1155/2022/2622310

53

Peters J. L. Sutton A. J. Jones D. R. Abrams K. R. Rushton L. (2007). Performance of the trim and fill method in the presence of publication bias and between-study heterogeneity. Stat. Med.26, 4544–4562. 10.1002/sim.2889

54

Qian S. (2009) The role of Sijunzi Decoction in the treatment of patients with cerebral palsy in replenishing qi and strengthening the spleen. J. North China Univ. Sci. Technol.North China11310–311.

55

Rosenbaum P. Paneth N. Leviton A. Goldstein M. Bax M. Damiano D. et al (2007). A report: the definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. Suppl.109, 8–14.

56

Sakpal T. V. (2010). Sample size estimation in clinical trial. Perspect. Clin. Res.1, 67–69. 10.4103/2229-3485.71856

57

Salomon I. (2024). Neurobiological insights into cerebral palsy: a review of the mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Brain Behav.14, e70065. 10.1002/brb3.70065

58

Schalow G. (2002). Recovery from spinal cord injury achieved by 3 months of coordination dynamic therapy. Electromyogr. Clin. Neurophysiol.42, 367–376.

59

Shan H. Zhang Y. Zhang P. Cao C. Lou Y. Hou Y. (2017). Observation on the therapeutic effect of nourishing kidney and inducing resuscitation for expelling phlegm prescription in the treatment of cerebral palsy with mental retardation. Chin. Med. Mod. Distance Educ.15, 78–80. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2017.01.034

60

Shi J. Xie Q. (2015). Integrated medicine therapy in treating 70 children with cerebral palsy of convulsion pattern. West. J. Tradit. Chin. Med.28, 104–106.

61

Shuchun Li (2000). Cerebral palsy in children. China: Henan Science and Technology Publisher.

62

Song J. Meng L. Li S. Qu L. Li X. (2009). A combination of Chinese herbs, Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus and Angelica sinensis, improved renal microvascular insufficiency in 5/6 nephrectomized rats. Vasc. Pharmacol.50, 185–193. 10.1016/j.vph.2009.01.005

63

Strickland A. D. (2014). Prevention of cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Med. Hypotheses82, 522–528. 10.1016/j.mehy.2014.02.003

64

Sun J. Wang J. Lin X. Xie B. Wu F. (2017). Effects of xingnao yizhi fang combined with rehabilitation training on children with cerebral palsy due to dystonia and its effect on transforming growth factor beta 1 and nerve remodeling in children. World Chin. Med.12, 2975–2978. 10.3969/j.issn.1673-7202.2017.12.028

65

Than U. T. T. Nguyen L. T. Nguyen P. H. Nguyen X. H. Trinh D. P. Hoang D. H. et al (2023). Inflammatory mediators drive neuroinflammation in autism spectrum disorder and cerebral palsy. Sci. Rep.13, 22587. 10.1038/s41598-023-49902-8

66

The Cochrane Collaboration (2014). Review Manager 5.4 (RevMan) [computer program].

67

Tung S. (2022). Clinical observation on rehabilitation training combined with huangqi guizhi wuwu decoction in the treatment of spastic cerebral palsy in children. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Med.38, 364–366.

68

Vadivelan K. Sekar P. Sruthi S. S. Gopichandran V. (2020). Burden of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: an intersectional analysis of gender, poverty, stigma, and public policy. BMC Public Health20, 645. 10.1186/s12889-020-08808-0

69

Vezér M. Gresits O. Engh M. A. Szabó L. Molnar Z. Hegyi P. et al (2024). Evidence for gait improvement with robotic-assisted gait training of children with cerebral palsy remains uncertain. Gait Posture107, 8–16. 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2023.08.016

70

Vinkers C. H. Olivier B. (2012). Mechanisms underlying tolerance after long-term benzodiazepine use: a future for subtype-selective GABA(A) receptor modulators?Adv. Pharmacol. Sci.2012, 416864. 10.1155/2012/416864

71

Vitrikas K. Dalton H. Breish D. (2020). Cerebral palsy: an overview. Am. Fam. Physician101, 213–220.

72

Wang H. Xu X. Yin Y. Yu S. Ren H. Xue Q. et al (2020). Catalpol protects vascular structure and promotes angiogenesis in cerebral ischemic rats by targeting HIF-1α/VEGF. Phytomedicine78, 153300. 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153300

73

Wang H. J. Ran H. F. Yin Y. Xu X. G. Jiang B. X. Yu S. Q. et al (2022). Catalpol improves impaired neurovascular unit in ischemic stroke rats via enhancing VEGF-PI3K/AKT and VEGF-MEK1/2/ERK1/2 signaling. Acta Pharmacol. Sin.43, 1670–1685. 10.1038/s41401-021-00803-4

74

Wang L. Chen B. Xie D. Wang Y. (2024). Bioinformatics and network pharmacology discover the molecular mechanism of Liuwei Dihuang pills in treating cerebral palsy. Med. Baltim.103, e40166. 10.1097/MD.0000000000040166

75

Wang M. C. Chou Y. T. Kao M. C. Lin Q. Y. Chang S. Y. Chen H. Y. (2023). Topical Chinese herbal medicine in treating atopic dermatitis (eczema): a systematic review and meta-analysis with core herbs exploration. J. Ethnopharmacol.317, 116790. 10.1016/j.jep.2023.116790

76

Wetterslev J. Jakobsen J. C. Gluud C. (2017). Trial Sequential Analysis in systematic reviews with meta-analysis. BMC Med. Res. Methodol.17, 39. 10.1186/s12874-017-0315-7

77

Wieland L. S. Manheimer E. Sampson M. Barnabas J. P. Bouter L. M. Cho K. et al (2013). Bibliometric and content analysis of the Cochrane Complementary Medicine Field specialized register of controlled trials. Syst. Rev.2, 51. 10.1186/2046-4053-2-51

78

Wimalasundera N. Stevenson V. L. (2016). Cerebral palsy. Pract. Neurol.16, 184–194. 10.1136/practneurol-2015-001184

79

Winstein C. J. Stein J. Arena R. Bates B. Cherney L. R. Cramer S. C. et al (2016). Guidelines for adult stroke rehabilitation and recovery: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association. Stroke47, e98–e169. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000098

80

Wu C. W. Chen H. Y. Yang C. W. Chen Y. C. (2021). Deciphering the efficacy and mechanisms of Chinese herbal medicine for diabetic kidney disease by integrating web-based biochemical databases and real-world clinical data: retrospective cohort study. JMIR Med. Inf.9, e27614. 10.2196/27614

81

Wu J. Zong H. Wang Y. Xu D. M. (2022). Clinical observation on Liuwei Dihuang pill and yigong power in the treatment of dyskinetic cerebral palsy. Guangming J. Chin. Med.37, 3514–3517. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2022.19.018

82

Wu Y. Li D. Wang H. Wan X. (2022). Protective effect of Poria cocos polysaccharides on fecal peritonitis-induced sepsis in mice through inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and reduction of treg cells. Front. Microbiol.13, 887949. 10.3389/fmicb.2022.887949

83

Yoo J. E. Yun Y. J. Shin Y. B. Kim N. K. Kim S. Y. Shin M. J. et al (2016). Protocol for a prospective observational study of conventional treatment and traditional Korean medicine combination treatment for children with cerebral palsy. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.16, 172. 10.1186/s12906-016-1161-6

84

Yu M. (2016). The influence of clinical effects and walking function on 40 cases of children with spastic cerebral palsy treated by the combination of Chinese herbs and rehabilitation training. J. Pediatr. Tradit. Chin. Med.12, 78–81. 10.16840/j.issn1673-4297.2016.05.25

85

Yuan J. J. Wu D. Wang W. W. Duan J. Xu X. Y. Tang J. L. (2021). A prospective randomized controlled study on mouse nerve growth factor in the treatment of global developmental delay in children. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi23, 786–790. 10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2106042

86

Yingyuan Hu (2009). “Evaluation standards for rehabilitation efficacy and prediction of rehabilitation outcomes for children with cerebral palsy,” in The 6th national pediatric cerebral palsy academic exchange and international exchange conference, 8–9.

87

Zhang C. (2021). Kaiqiao Xingshen Decoction combined with head acupoint massage in the treatment of cerebral palsy in children. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Med.37, 745–746.

88

Zhang L. Q. Chen K. X. Li Y. M. (2019). Bioactivities of natural catalpol derivatives. Curr. Med. Chem.26, 6149–6173. 10.2174/0929867326666190620103813

89

Zhang W. L. Cao Y. A. Xia J. Tian L. Yang L. Peng C. S. (2018). Neuroprotective effect of tanshinone IIA weakens spastic cerebral palsy through inflammation, p38MAPK and VEGF in neonatal rats. Mol. Med. Rep.17, 2012–2018. 10.3892/mmr.2017.8069

90

Zhang Y. Liu J. Wang J. He Q. (2010). Traditional Chinese medicine for treatment of cerebral palsy in children: a systematic review of randomized clinical trials. J. Altern. Complement. Med.16, 375–395. 10.1089/acm.2009.0609

91

Zhang Y. Xiang S. Wang M. C. (2019). Influences of huangqi guizhi wuwu decoction combined with aerobic rehabilitation exercise on therapeutic effect, serum BDNF, NSE levels, and motor function in the treatment of children with spastic cerebral palsy. Chin. J. Integr. Med. Cardio-Cerebrovascular Dis.17, 2744–2747. 10.12102/j.issn.1672-1349.2019.18.006

Summary

Keywords

meta-analysis, cerebral palsy, Chinese herbal medicine, system pharmacology, traditional Chinese medicine

Citation

Huang Y-Y, Cheng Y-Y, Chen H-Y, Fu R-H, Chang Y-J and Yang T-H (2025) Chinese herbal medicine for the treatment of children with cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials with core herbs exploration. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1500095. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1500095

Received

22 September 2024

Accepted

02 January 2025

Published

26 February 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Karim Hosni, Institut National de Recherche et d'Analyse Physico-Chimique (INRAP), Tunisia

Reviewed by

Kylie Crompton, Royal Children’s Hospital, Australia

Afef Amri, Institut National des Sciences et Technologies de la Mer, Tunisia

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Huang, Cheng, Chen, Fu, Chang and Yang.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tsung-Hsien Yang, 8905001@cgmh.org.tw

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.