Abstract

Background:

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), an ancient affliction, continues to present significant challenges in modern medicine. Baihe Gujin Decoction, a traditional Chinese botanical drug remedy, has been widely utilized in clinical practice for tuberculosis treatment, yet its efficacy has been inconsistent. This meta-analysis aims to ascertain its effectiveness and contribute to evidence-based medicine.

Methods:

A comprehensive search was conducted across multiple databases, including PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, China Science and Technology Journal Database, Wanfang Database, China Biomedical Literature Database, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure, to identify relevant randomized controlled trials from January 2010 to February 2024. The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool, and meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager and Stata to evaluate the comparative outcomes.

Results:

This meta-analysis encompassed 32 studies. The control group exhibited a notably higher clinical overall efficacy rate [OR = 5.50, 95%CI (4.18, 7.24), P < 0.05], lesion absorption rate [OR = 5.83, 95%CI (4.08, 8.33), P < 0.05], cavity change rate [OR = 2.35, 95%CI (1.50, 3.69), P < 0.05], and sputum negative conversion rate [OR = 2.85, 95%CI (2.12, 3.83), P < 0.05]. In contrast, the treatment group demonstrated an increase in CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels post-treatment, with a weighted mean difference of [OR = 4.87, (95%CI (1.91, 7.83), P < 0.05]. Furthermore, safety indices, including the incidence of total adverse reactions, liver function abnormalities, and gastrointestinal reactions, were significantly lower in the treatment group.

Conclusion:

The combination of Baihe Gujin Decoction with biomedicine is more efficacious than biomedicine alone for treating PTB. This superiority is evident in improved clinical efficacy rates, lesion absorption, cavity changes, sputum negative conversion rates, and immune indices, alongside a reduced incidence of adverse reactions.

Systematic review registration::

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/, CRD42023462056

1 Introduction

Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB), characterized by chronic infection of the lungs, remains a formidable threat to global health. Identified as the causative agent, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) has emerged as a leading cause of mortality from infectious diseases, second only to COVID-19 (Peng et al., 2024). In 2023 alone, tuberculosis (TB) claimed an estimated 1.08 million lives among HIV-negative individuals (WHO, 2024; Chen et al., 2025). Despite advancements in TB management through strategic treatment protocols and anti-tuberculosis drugs such as isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and either ethambutol or streptomycin, the prevalence of adverse drug reactions often leads to treatment discontinuation, hindering efforts to control the disease. The conventional chemotherapy for PTB, while effective, necessitates prolonged treatment durations and is not without its drawbacks, including a high incidence of adverse reactions that can compromise patient adherence and therapeutic success. This underscores an urgent need for innovative pharmacotherapies that are both safe and efficacious, enhancing patient compliance and bolstering the global fight against TB.

Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), deeply rooted in China’s cultural heritage, has made significant contributions to the prevention and management of TB within the country (Liang et al., 2021). From a TCM perspective, PTB is classified as “Fei Lao,” attributed to a deficiency in vital energy and the invasion of pathogenic factors into the lungs (Chen, 2020; Su HT et al., 2020). TCM, with its extensive array of natural metabolites, coherent theoretical framework, and minimal side effects, offers distinct advantages in managing PTB. It employs strategies that aim to strengthen the body’s essential energy, expel pathogens, nourish the liver and kidneys, enhance blood circulation, and address both the root causes and specific manifestations of the disease. As a complementary therapy, TCM not only boosts immune responses but also accelerates lesion resolution and aids in swift recovery. The integration of TCM with Chemotherapy has the potential to reduce adverse reaction rates, improve patient compliance, and achieve more favorable therapeutic outcomes (Lei FY and Wang, 2006). This approach highlights the value of combining traditional and modern medical practices for a holistic treatment of PTB.

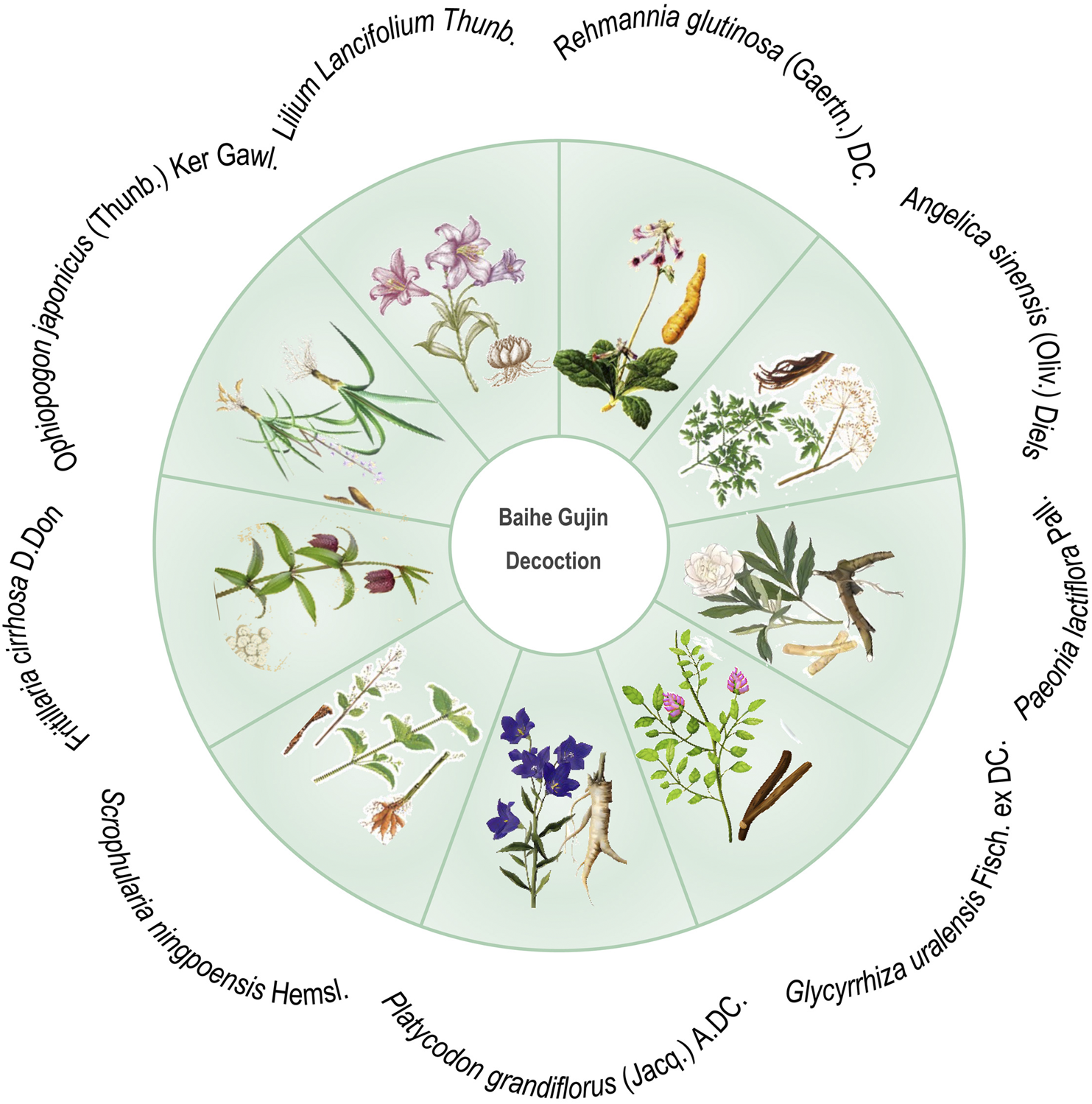

Baihe Gujin Decoction (BGD), a TCM prescription formula, is composed of nine botanical drugs known for their potent immunomodulatory, including Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. [Liliaceae; Lilii bulbus], Rehmannia glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC. [Scrophulariaceae; Rehmanniae radix], Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels [Apiaceae; Angelicae sinensis radix], Paeonia lactiflora Pall. [Paeoniaceae; Paeoniae radix], Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. [Fabaceae; Glycyrrhizae radix et rhizoma], Platycodon grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. [Campanulaceae; Platycodonis radix], Scrophularia ningpoensis Hemsl. [Scrophulariaceae; Scrophulariae radix], Fritillaria cirrhosa D. Don [Liliaceae; Fritillariae cirrhosae bulbus] and Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. [Asparagaceae; Ophiopogonis radix] (Figure 1). In attention to anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties, it exhibits spasmolytic, anti-asthmatic, and expectorant effects, making it particularly effective in treating conditions such as PTB, chronic bronchitis, hemoptysis secondary to bronchiectasis, chronic pharyngitis, and spontaneous pneumothorax (Ge and Zhu, 2020; Jia et al., 1992). The clinical efficacy of BGD in PTB patients has been supported by various systematic reviews (Liu et al., 2022). However, its antimicrobial action against MTB and other pathogens is relatively moderate, suggesting that its therapeutic potential may be attributed to its regulatory effects on immune function (Wang et al., 2022). In managing MTB infection, combining BGD with conventional anti-tuberculosis pharmacotherapy is advisable to optimize patient outcomes. As we all know, one of the most common side effects of biomedicine is a strong liver damage. Wang et al. found that the combination of BGD and modern anti-TB drugs in the treatment of TB is not only beneficial to the improvement of symptoms and recovery of health, but also reduces the liver damage caused by anti-TB drugs (Wang, 2004). BGD is clearly preferred over other TCM formulas because it has a longer history of treating TB and is one of the preferred formulas for treating TB in combination with biomedicine. Despite numerous studies on the drug composition, metabolites, clinical efficacy, and mechanism of action of BGD, there is a paucity of specific evaluations regarding the combination therapy of BGD with anti-tuberculosis drugs for PTB.

FIGURE 1

Schematic diagram of botanical drugs involved in Baihe Gujin Decoction formula.

To bridge this knowledge gap, the present systematic meta-analysis incorporates randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to compare the efficacy and safety of BGD combined with anti-tuberculosis drugs versus the use of anti-tuberculosis drugs alone for PTB treatment. This study aims to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the effectiveness of BGD in combination therapy, offering more reliable evidence for clinical practice.

2 Materials and methods

This study strictly adhered to the guidelines set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. A PRISMA checklist is provided as a supplementary file (Supplementary File S1), and the protocol for this review has been registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42023462056).

2.1 Literature search strategy

A thorough computer-based search was conducted across both Chinese and English databases to ensure a comprehensive literature review. The search timeframe from database inception to 1 September 2024. The databases included PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Wanfang Database, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, The China Science and Technology Journal Database, and China Biomedical Literature Database. The search strategy was meticulously crafted to encompass relevant studies, utilizing terms such as “Baihe Gujin Decoction,” “pulmonary tuberculosis,” “Traditional Chinese Medicine,” and “tuberculosis”. The dual-language approach aimed to ensure the inclusion of all pertinent studies, as detailed in Table 1.

TABLE 1

| Databases | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | ((Pulmonary Tuberculosis [MeSH Major Topic]) OR ((Tuberculoses, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Tuberculoses):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Tuberculosis):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Consumption):ab,ti,kw OR (Consumption, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Consumptions, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Consumptions):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Phthisis):ab,ti,kw OR (Phthises, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Phthisis, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Phthises):ab,ti,kw [Title/Abstract])) AND (Baihe Gujin Decoction [Title/Abstract]) OR (Traditional Chinese Medicine):MeSH]) |

| Embase | #1 = ‘lung tuberculosis’/exp |

| #2 = ‘lung tuberculosis’:ab,ti OR ‘lung tb’:ab,ti OR ‘pulmonary tb’:ab,ti OR ‘lung tuberculous cavity’:ab,ti OR ‘chronic pulmonary tuberculosis’:ab,ti | |

| #3 = #1 OR #2 | |

| #4 = ‘baihe gujin decoction’ OR ‘baihe gu jin decoction’ OR ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine’ | |

| #5 = #3 And #4 | |

| The Cochrane Library | #1 Tuberculosis, Pulmonary |

| #2 (Tuberculoses, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Tuberculoses):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Tuberculosis):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Consumption):ab,ti,kw OR (Consumption, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Consumptions, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Consumptions):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Phthisis):ab,ti,kw OR (Phthises, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Phthisis, Pulmonary):ab,ti,kw OR (Pulmonary Phthises):ab,ti,kw | |

| #3 = #1 OR #2 | |

| #4 (Baihe Gujin decoction):ti,ab,kw OR (Baihe Gujin*):ti,ab,kw OR (Traditional Chinese Medicine):ti,ab,kw | |

| #5 = #3 AND #4 | |

| Wanfang Database | 主题: (百合固金汤or百合固金汤加味or百合固金汤加减) and 主题: (肺结核) |

| China National Knowledge Infrastructure | 主题: (百合固金汤+百合固金汤加味+百合固金汤加减) AND主题: (肺结核 + 肺结核病 + 典型肺结核) |

| The China Science and Technology Journal Database | 题名或关键词 = 百合固金汤or百合固金汤加味or百合固金汤加减 AND 题名或关键词 = 肺结核 |

| Chian Biomedical Literature | (“百合固金汤” [常用字段:智能] OR “百合固金汤加味” [常用字段:智能] OR “百合固金汤加减” [常用字段:智能] AND “肺结核” [常用字段:智能]) |

Search strategy.

Furthermore, a reference search methodology was employed, which involved scrutinizing the reference lists of identified articles to uncover additional relevant studies. This rigorous search strategy was designed to enhance the robustness and reliability of our meta-analysis.

2.2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) study subjects diagnosed with PTB based on clinical diagnostic criteria, irrespective of age or gender; (2) intervention measures where the control group received conventional anti-TB treatment with chemical drugs alone, and the treatment group received BGD in conjunction with conventional anti-TB treatment; (3) language restrictions limited to Chinese or English literature.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) duplicated publications; (2) literature with incomplete or incorrect data, or lacking complete content; (3) non-randomized controlled trials; (4) case reports, conference records, and review articles.

2.3 Data extraction and quality assessment

The included literature was subjected to risk assessment using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment Tool. Two independent researchers performed literature screening and data extraction, with disagreements resolved through consultation with the corresponding author. The primary outcome measures extracted included the clinical efficacy rate and lesion absorption rate. Secondary outcome measures encompassed sputum negative conversion rate, changes in cavities, the incidence of adverse reactions, such as liver function abnormalities, gastrointestinal reactions, and CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels post-treatment.

2.4 Statistical analysis

The meta-analysis data were rigorously analyzed using RevMan (version 5.4; Copenhagen, Denmark) and Stata (version SE 15.1; College station, TX, United States of America), employing a dual-software approach to ensure robustness and accuracy (Wang et al., 2023). Dichotomous variables were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), assessing the strength of association between interventions and outcomes. Continuous variables were articulated as weighted mean differences (WMDs) with 95% CIs, facilitating comparison of average outcomes between groups.

Heterogeneity among the included studies was evaluated, with significant heterogeneity indicated by P-values ≤0.05 or I2 ≥ 50%. A random-effects model was selected for analysis in such cases, acknowledging variability across studies. A fixed-effects model was applied when P-values >0.05 and I2 < 50%, assuming observed variability was due to chance.

Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s quantitative test, crucial for evaluating potential bias. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using Stata 15.1 by sequentially excluding leading outcome measure indicators. The stability and reliability of the results were inferred from the absence of significant changes upon these exclusions. The significance level for the meta-analysis was set at an alpha (α) of 0.05, establishing a rigorous threshold for statistical significance.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening process

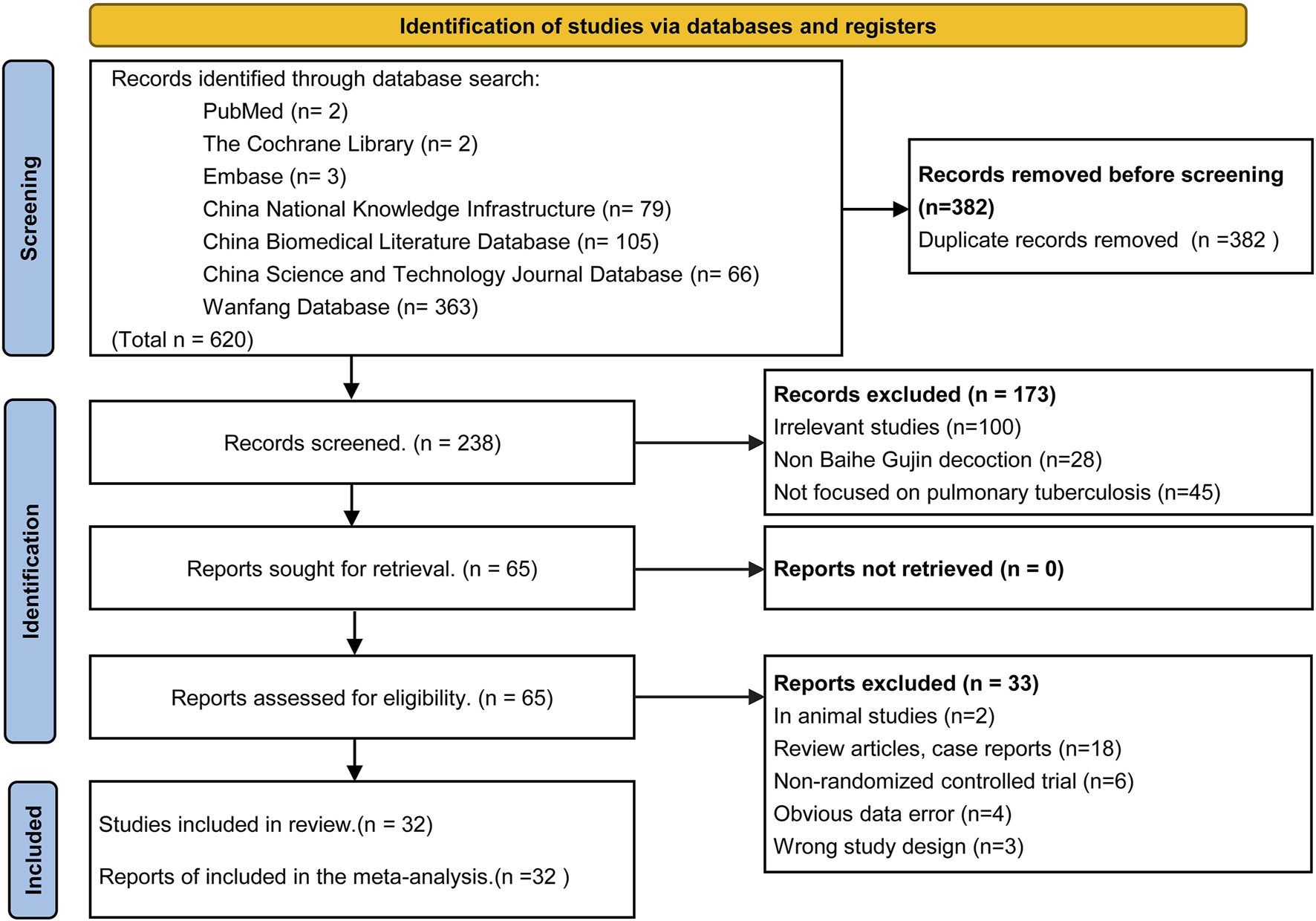

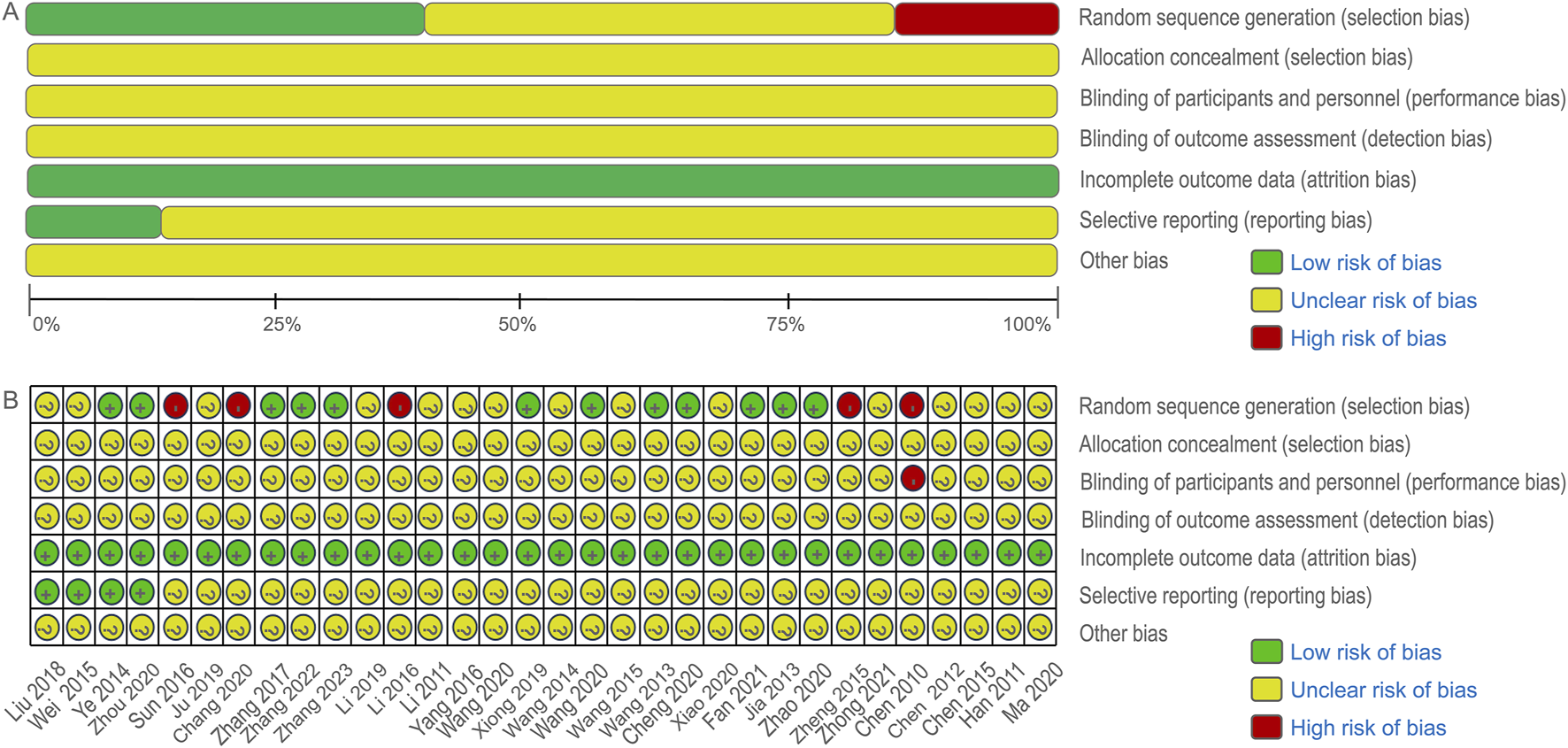

The initial search yielded 620 articles, of which 238 remained after duplicate removal using Endnote X9 software. Following title and abstract review, 173 articles were excluded, leaving 65 articles for initial inclusion. Full-text screening led to the exclusion of 33 articles for various reasons, including two animal experiments, four articles with data errors, six non-randomized controlled trials, 18 case reports and reviews, and three for other reasons. Ultimately, 32 RCTs were included in the analysis, of which only 27 explicitly mentioned random allocation concealment and 12 were double-blind designs. The literature screening process is depicted in Figure 2, and the risk of bias in the included studies is presented in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2

Flow diagram of the article selection process (PRISMA 2020).

FIGURE 3

Cochrane risk bias assessment tool.

3.2 Characteristics of included studies

Table 2 summarizes the main characteristics of the included studies, which were published between 2010 and 2024 and originated from Chinese publications. A total of 2,761 patients were randomly assigned to treatment with either anti-tuberculosis drugs alone or a combination therapy with BGD, as detailed in the Jadad scale provided in Supplementary File S2.

TABLE 2

| Study ID | Sample size (C/T) | Male/Female (C/T) | Mean age (years, C/T) | Control group | Treatment group | Durations (days) | Outcomes | JADAD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li 2016 (Li, 2016) | 46/49 | 23:23/28:21 | 48.0 ± 2.9/49.0 ± 3.6 | National standard chemotherapy regimen | BGD + C | 30d | ① | 4 |

| Jia 2013 (Jia, 2013) | 59/59 | 41:18/39:40 | 49 ± 4.89/51 ± 5.57 | National standard chemotherapy regimen | BGD + C | 7d is one course of treatment, with 1 month of treatment | ① | 3 |

| Liu 2018 (Liu, 2018) | 54/54 | 23:41/24:30 | 44.29 ± 6.24/42.13 ± 5.88 | 6ZAmLfxPASPto (Cs)/18ZLfxPtoPAs scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①③⑧ | 4 |

| Xiao 2020 (Xiao, 2020) | 82/82 | 42:40/44:38 | 50.97 ± 3.48/51.02 ± 3.53 | HRZES (Qod) scheme | BGD + C | 7d is one course of treatment, with 1 month of treatment | ① | 2 |

| Chen 2015 (Chen et al., 2015) | 30/30 | 18:12/16:14 | 36.7 ± 1/40.2 ± 1 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 60d | ①②⑤⑥⑦ | 3 |

| Wei 2015 (Wei, 2015) | 34/34 | NA | NA | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①⑤⑦ | 4 |

| Zheng 2015 (Zheng, 2015) | 60/60 | NA | NA | 6ZKm (Am,Cm)Lfx (Mfx)Cs(PAS,E)Pto/18ZLfx (Mfx)Cs(PAS,E)Pto scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①②③ | 4 |

| Chen 2010 (Chen and Zhou, 2010) | 35/40 | NA | NA | National standard chemotherapy regimen | BGD + C | 180d | ①②③④ | 2 |

| Ye 2014 (Ye, 2014) | 37/38 | 24:13/26:12 | 39/37 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ②③ | 5 |

| Li 2011 (Li, 2011) | 30/30 | 18:12/20:10 | NA | 3PaAmThVZ/15PaThVZ scheme | BGD + C | 90d | ② | 4 |

| Chang 2020 (Chang and Jin, 2020) | 75/75 | 48:27/45:30 | 47.53 ± 3.68/45.37 ± 3.41 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 90d | ①③ | 3 |

| Wang 2015 (Wang, 2015) | 53/53 | 30:23/28:25 | 47.5/46 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 90d | ① | 3 |

| Wang 2014 (S. and W. 36 Cases of, 2014) | 36/36 | 23:13/24:12 | 46.88 ± 3.98/47.52 ± 5.43 | Conventional anti tuberculosis treatment with biomedicine | BGD + C | 90d | ① | 3 |

| Chen 2012 (Chen, 2012) | 31/31 | 17:14/23:8 | NA | 3PaAmThVZ/15PaThVZ scheme | BGD + C | 90d | ② | 2 |

| Li 2019 (Li, 2019) | 42/42 | 20:22/24:18 | 41.6 ± 0.5/40.5 ± 0.5 | Conventional anti tuberculosis treatment with biomedicine | BGD + C | NA | ①⑤⑦ | 2 |

| Wang 2013 (Wang, 2013) | 30/30 | 19:11/18:12 | 48.3 ± 18.2/47.9 ± 19.1 | 2HBZES/6HBE scheme | BGD + C | 90d | ①②③ | 5 |

| Fan 2021 (Fan et al., 2021) | 30/30 | 15:15/16:14 | 49.52 ± 3.26/49.50 ± 3.20 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①③④ | 5 |

| Han 2011 (Han et al., 2011) | 40/40 | 25:15/19:21 | 66.5/64.5 | Conventional anti tuberculosis treatment with biomedicine | BGD + C | 14d is one course of treatment, with 4 courses of treatment | ①② | 3 |

| Sun 2016 (Sun, 2016) | 60/60 | 30:30/31:29 | 44.51 ± 12.8/46.25 ± 13.6 | Initial treatment 2HRZE/4HR, re treatment 2HRZSE/5HRE | BGD + C | 180–240d | ①③④ | 3 |

| Zhang 2022 (Zhang, 2022) | 31/31 | 17:14/18:13 | 49.25 ± 6.56/49.30 ± 6.40 | 3HRZE/6HR scheme | BGD + C | 60d is one course of treatment, with 3 courses of treatment | ①⑤⑥⑦ | 5 |

| Zhang 2023 (Zhang, 2023) | 40/40 | 24:16/22:18 | 66.05 ± 7.26/65.93 ± 7.14 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 90d | ①⑤⑥⑦⑨ | 5 |

| Zhang 2017 (Zhang, 2017) | 50/50 | 26:24/23:27 | 45.3 ± 13.6/40.8 ± 13.6 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①②③④ | 4 |

| Zhao 2020 (Zhao and Wang, 2020) | 41/41 | 24:17/22:19 | 46.73 ± 5.62/46.85 ± 5.17 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①⑧ | 4 |

| Wang 2020 (Wang et al., 2020a) | 43/43 | 25:18/24:19 | 53.01 ± 4.45/52.49 ± 4.56 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①③⑧ | 4 |

| Ju 2019 (Ju, 2019) | 21/21 | 12:9/11:10 | 44.5 ± 3.6/44.0 ± 3.5 | biomedicine anti tuberculosis treatment (6Z-AM-V-PAS-Pto-Cs) | BGD + C | 180d | ①⑧ | 2 |

| Zhong 2021 (Zhong et al., 2021) | 46/46 | 24:22/26:20 | 39.1 ± 5.1/41.3 ± 5.3 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①③⑤⑥ | 3 |

| Yang 2016 (Yang et al., 2016) | 30/30 | 15:15/16:14 | 48/50 | HRZE quadruple therapy alone | BGD + C | 7d is one course of treatment, with 1 month of treatment | ① | 3 |

| Cheng 2020 (Cheng et al., 2020) | 47/47 | 26:21/28:19 | 66.9 ± 1.5/67.1 ± 1.8 | 2HRZE/4HR scheme | BGD + C | 180d | ①③④⑧ | 5 |

| Xiong 2019 (Xiong, 2019) | 44/44 | 24:20/25:19 | 38.43 ± 2.43 | Conventional anti tuberculosis treatment with biomedicinee | BGD + C | 180d | ①②③④ | 4 |

| Zhou 2020 (Zhou, 2020) | 47/47 | 23:24/26:21 | 36.11 ± 8.58/37.85 ± 9.61 | Conventional anti tuberculosis treatment with biomedicine | BGD + C | 180d | ①⑤⑥⑦ | 5 |

| Wang 2020 (Wang et al., 2020b) | 36/36 | 19:17/21:15 | 48.3 ± 10.4/47.8 ± 11.6 | The treatment plan formulated according to the “New Guidelines for the Treatment of Multidrug resistant tuberculosis” proposed by WHO | BGD + C | 90d | ①②③ | 3 |

| Ma 2020 (Ma, 2020) | 36/36 | 16:20/19:17 | 34.8 ± 4.6/38 ± 4.9 | Conventional anti tuberculosis treatment with biomedicine | BGD + C | NA | ②⑦ | 3 |

Characteristics of the included studies.

Am: Amikacin; BGD: baihe gujin decoction; C: control group; Cm: Capreomycin; Cs: Cycloserine; d: Days; E: ethambutol; H: isoniazid; Km: Kanamycin; Lfx (V): levofloxacin; Mfx: Moxifloxacin; NA: no relevant information; PAS: paza-aminosalicylate; Pto/Pa/Th: Protionamide; Qod: Take medication the next day; R: rifampicin; S: streptomycin; T: treatment group; Z: pyrazinamide.

①: the clinical efficacy rate ②: the lesions absorption rate ③: the sputum negative conversion rate ④: the changes in cavities ⑤: the incidence of totl adverse reactions ⑥: the incidence of liver function abnormalities ⑦: the incidence of gastrointestinal reactions ⑧: the CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels.

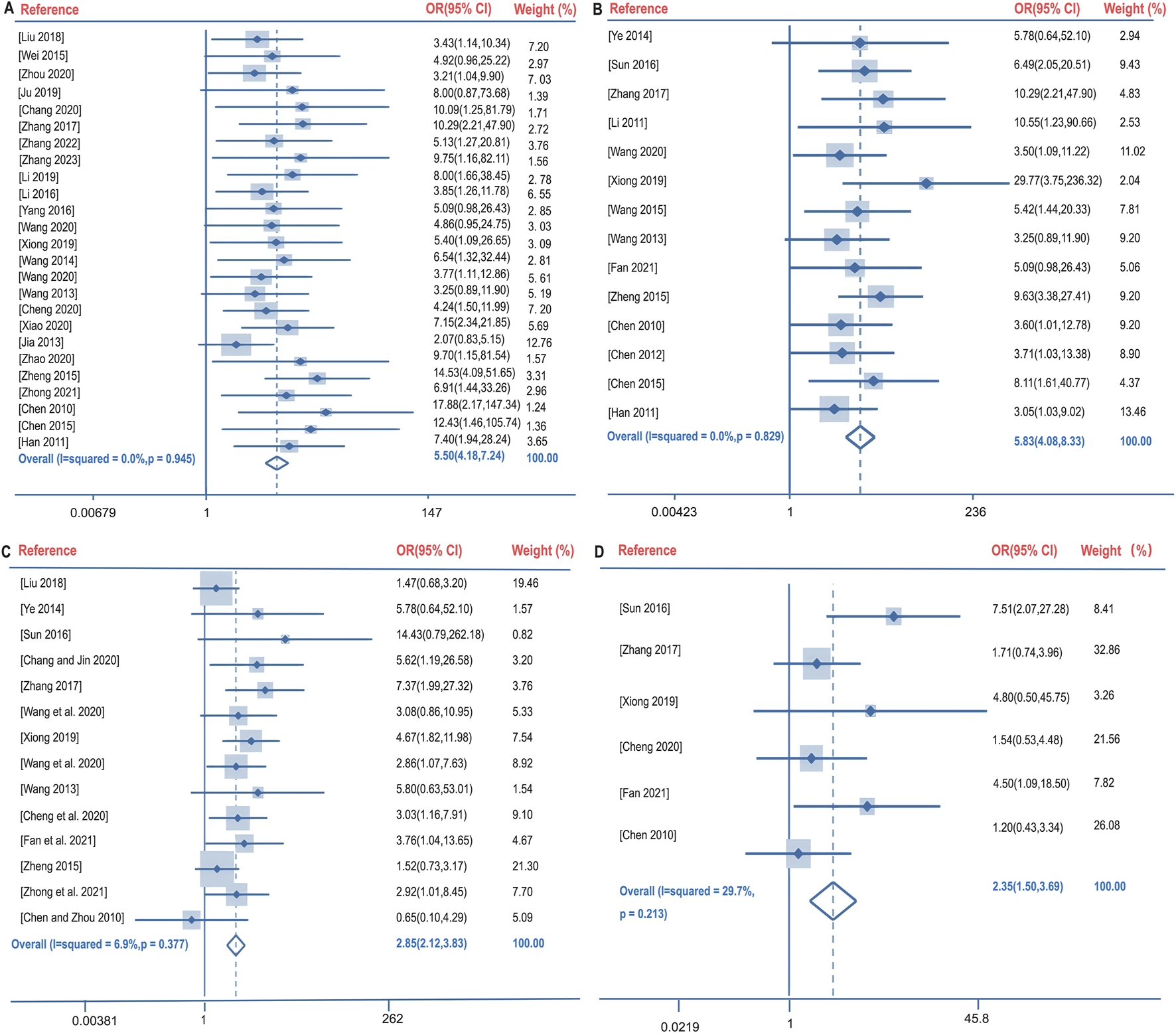

3.3 Clinical efficacy rate

Clinical efficacy is defined as a significant improvement in the clinical symptoms of the patient after treatment, supported by imaging (e.g., chest X-ray or CT), and a comprehensive assessment in combination with laboratory indices. The clinical efficacy rate of BGD combined with chemotherapy for PTB treatment was compared with chemotherapy alone across 28 studies (Chang and Jin, 2020; Chen et al., 2015; Chen and Zhou, 2010; Cheng et al., 2020; Han et al., 2011; Jia, 2013; Ju, 2019; Li, 2019; Liu, 2018; Wang, 2013; Wang M. et al., 2020; Wang, 2014; Wang Y. et al., 2020; Wei, 2015; Xiao, 2020; Xiong, 2019; Yang et al., 2016; Zhang, 2017; Zhang, 2023; Zheng, 2015; Wang, 2015; Fan et al., 2021; Sun, 2016; Zhang, 2022; Zhao and Wang, 2020; Zhong et al., 2021; Zhou, 2020; Li, 2016). No significant heterogeneity was observed (P = 0.945, I2 = 0%), leading to the use of a fixed-effects model for meta-analysis. The results indicated a significantly higher clinical efficacy rate in the treatment group compared to the control group [OR = 5.50, 95%CI (4.18, 7.24), P < 0.05], as shown in Figure 4A.

FIGURE 4

Forest plot of the clinical efficacy rate (A), lesions absorption rate (B), sputum negative conversion rate (C), and changes in cavities (D).

3.4 Lesion absorption rate

Lesion absorption refers to the reduction in lesion size observed through imaging techniques. The lesion absorption rate following BGD combined with chemotherapy was compared with chemotherapy alone in 11 studies (Chen et al., 2015; Chen and Zhou, 2010; Han et al., 2011; Wang, 2013; Wang Y. et al., 2020; Xiong, 2019; Zhang, 2017; Zheng, 2015; Ye, 2014; Chen, 2012; Li, 2011). Again, no significant heterogeneity was found (P = 0.829, I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effects model was utilized. The treatment group demonstrated a significantly better lesion absorption rate than the control group [OR = 5.83, 95%CI (4.08, 8.33), P < 0.05], as illustrated in Figure 4B.

3.5 Sputum negative conversion rate

The sputum negative conversion rate after BGD combined with chemotherapy was compared with chemotherapy alone in 15 studies (Chang and Jin, 2020; Chen and Zhou, 2010; Cheng et al., 2020; Liu, 2018; Wang, 2013; Wang M. et al., 2020; Wang Y. et al., 2020; Xiong, 2019; Zhang, 2017; Zheng, 2015; Fan et al., 2021; Sun, 2016; Zhong et al., 2021; Ye, 2014; Ma, 2020). No significant heterogeneity was present (P = 0.377, I2 = 6.9%), and a fixed-effects model was applied. The treatment group had a higher sputum negative conversion rate than the control group, with a statistically significant difference [OR = 2.85, 95%CI (2.12, 3.83), P < 0.05], depicted in Figure 4C.

3.6 Changes in cavities

The changes in cavities following BGD combined with chemotherapy were compared with chemotherapy alone in six studies (Chen and Zhou, 2010; Cheng et al., 2020; Xiong, 2019; Zhang, 2017; Fan et al., 2021; Sun, 2016). No significant heterogeneity was detected (P = 0.213, I2 = 29.7%), and a fixed-effects model was employed. The treatment group showed significantly better cavity changes than the control group [OR = 2.35, 95%CI (1.50, 3.69), P < 0.05], as shown in Figure 4D.

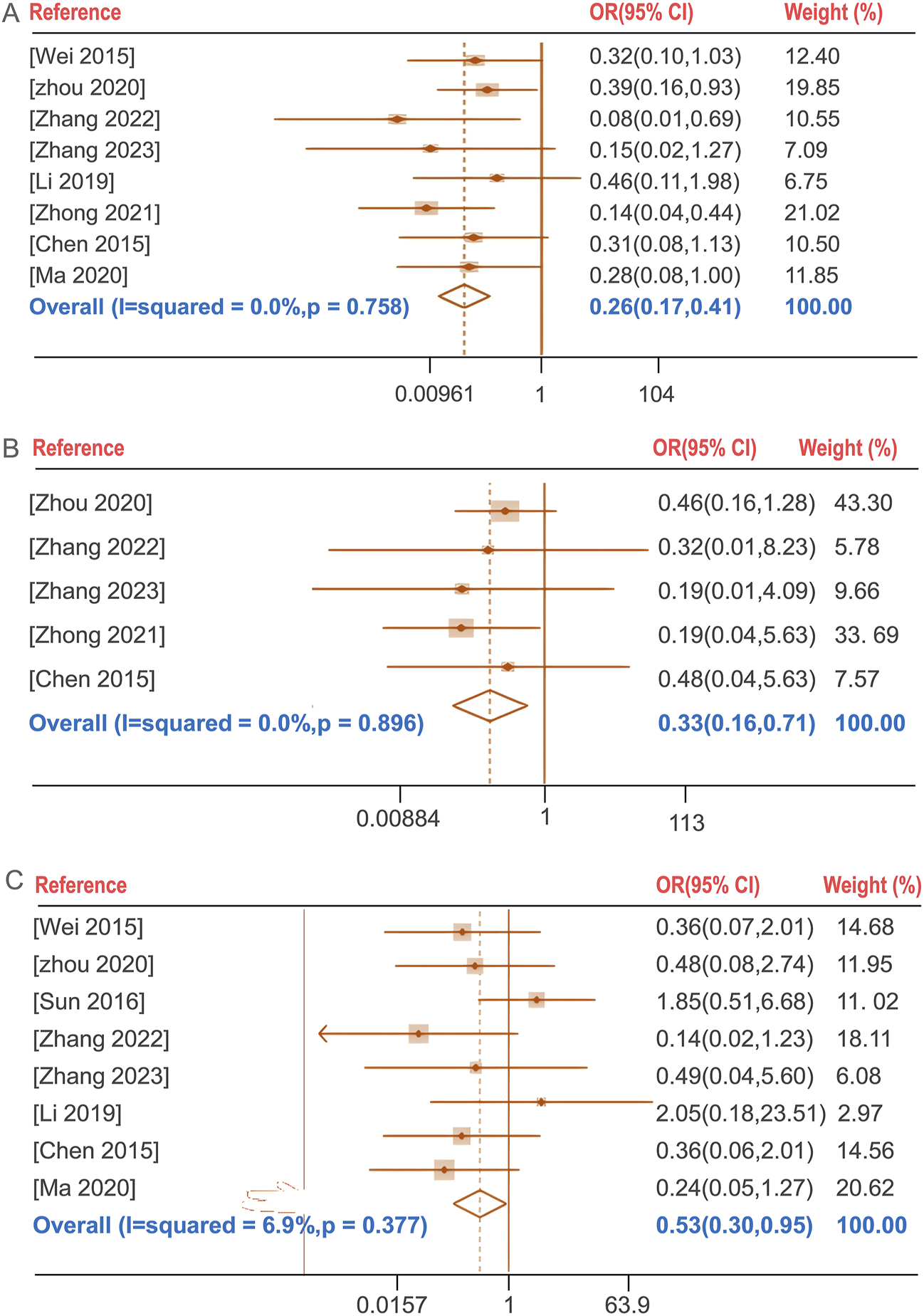

3.7 Safety evaluation indicators

The incidence of total adverse events following BGD combined with chemotherapy was compared with chemotherapy alone in seven studies (Chen et al., 2015; Li, 2019; Wei, 2015; Zhang, 2023; Zhang, 2022; Zhong et al., 2021; Zhou, 2020). No significant heterogeneity was found (P = 0.758, I2 = 0%), and a fixed-effects model was used. The treatment group exhibited a lower incidence of total adverse reactions compared to the control group [OR = 0.26, 95%CI (0.17, 0.41), P < 0.05]. The total adverse reactions include gastrointestinal reactions (nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhea, etc.), allergic reactions (rash), Blood system (leukopenia), liver function abnormalities and neurological reactions (headache, dizziness, drowsiness, etc.). Notably, the incidence of liver function abnormalities and gastrointestinal reactions showed statistically significant differences with OR (95%CI) values of 0.33 (0.16, 0.71) and 0.53 (0.30, 0.95), respectively (P < 0.05) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5

Forest plot of the incidence of total adverse reactions (A), the incidence of liver function abnormalities (B), the incidence of gastrointestinal reactions (C).

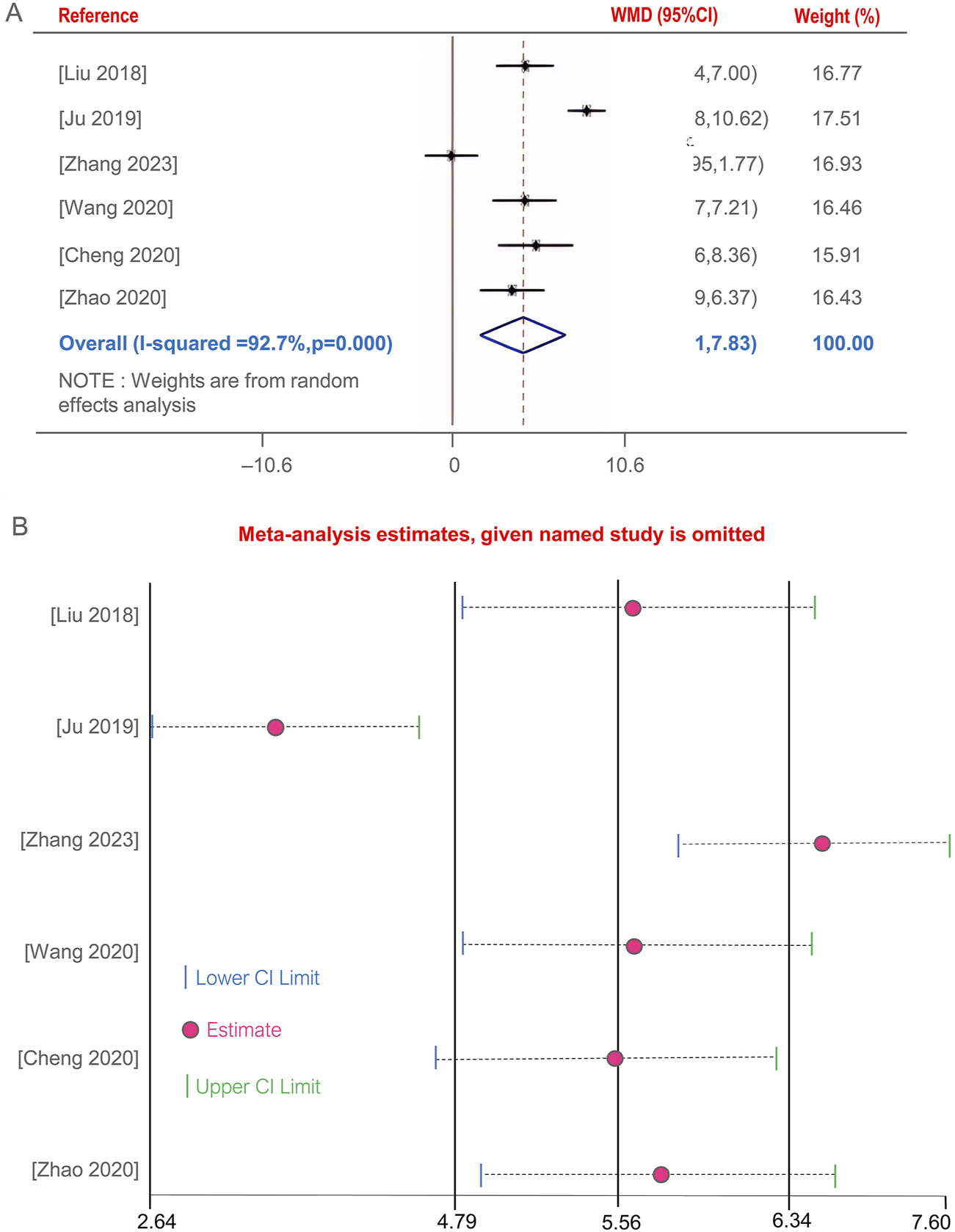

3.8 CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels

Five studies (Cheng et al., 2020; Ju, 2019; Liu, 2018; Wang M. et al., 2020; Zhang, 2023; Zhao and Wang, 2020)evaluated the improvement of CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels before and after BGD treatment for PTB. The combined therapy with BGD significantly enhanced immune status, with a weighted mean difference [OR = 4.87, 95%CI (1.91, 7.83), P < 0.05] (Figure 6A). Due to high heterogeneity was observed (P = 0, I2 = 92.7%). Sensitivity analysis through one-by-one exclusion did not reveal a cause for the high heterogeneity, and the overall results remained statistically significant, indicating robust findings, as shown in Figure 6B.

FIGURE 6

Forest plot of the CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels (A), Sensitivity analysis of the CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels (B).

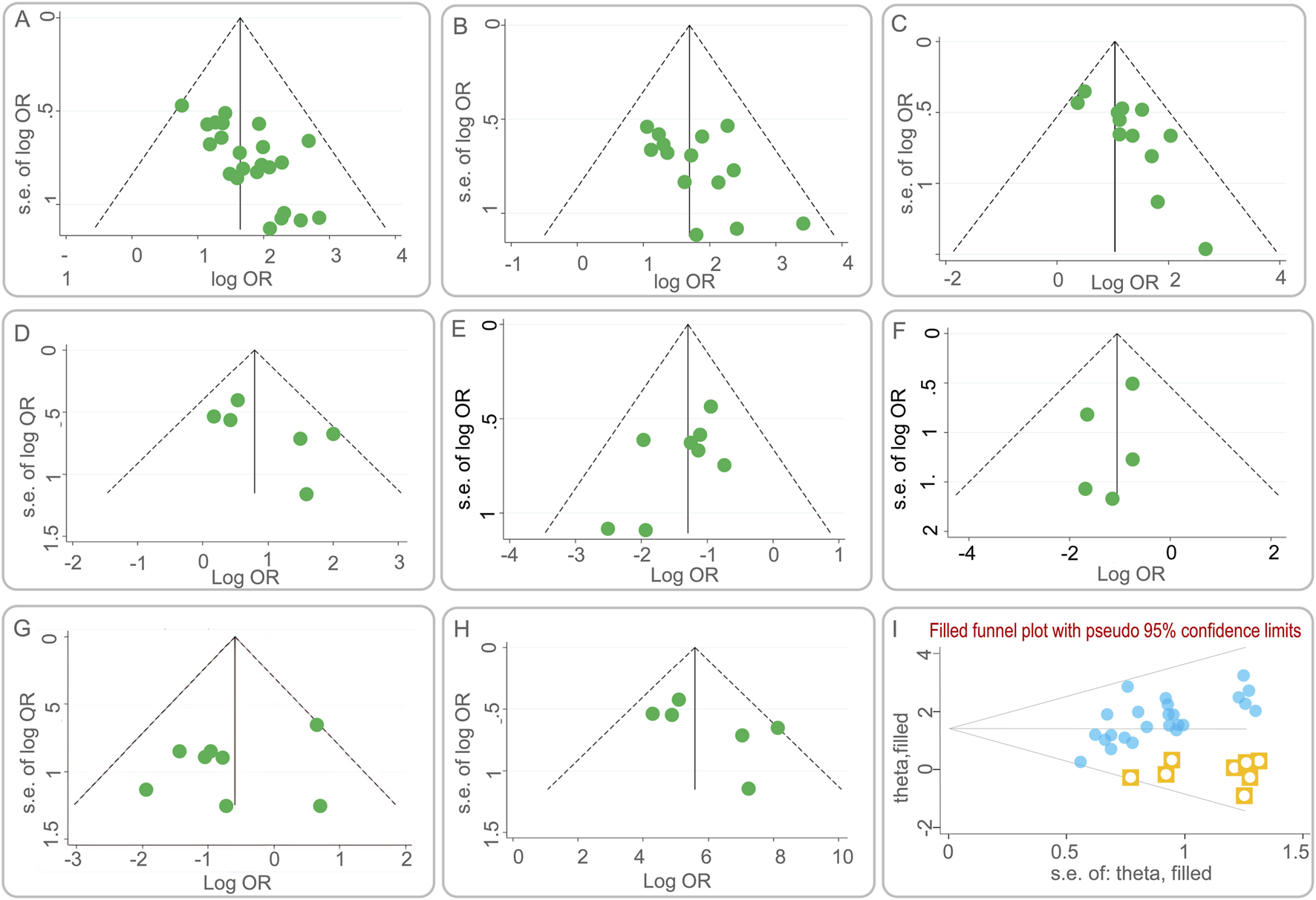

3.9 Publication bias

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots, a graphical representation that can indicate the presence of asymmetry, suggesting potential bias. Figures 7A–H presents the funnel plots for various outcome measures. Symmetrical funnel plots for the lesion absorption rate and the incidence of liver function abnormalities suggest that the combination of BGD with chemical drugs is more effective. However, asymmetry in the funnel plots for the clinical efficacy rate, sputum negative conversion rate, changes in cavities, incidence of total adverse reactions, incidence of gastrointestinal reactions, and CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels indicates potential publication bias.

FIGURE 7

Funnel plots of publication bias. (A) the clinical efficacy rate; (B) the lesion absorption rate; (C) the sputum negative conversion rate; (D) the changes in cavities; (E) the incidence of total adverse reactions; (F) the incidence of liver function abnormalities; (G) the incidence of gastrointestinal reactions; (H) the CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels; (I) Funnel plot of the clinical efficacy rate after using the trim-and-fill method.

To quantitatively assess publication bias, Egger’s test was employed using Stata 15.1. The results are detailed in Table 3. While the P-values for most outcome measures were greater than 0.05, indicating no significant publication bias, the clinical efficacy rate showed a P-value less than 0.05, suggesting the presence of publication bias.

TABLE 3

| Index | P value |

|---|---|

| The clinical efficacy rate | 0.029 |

| The lesion absorption rate | 0.997 |

| The sputum negative conversion rate | 0.668 |

| The changes in cavities | 0.279 |

| The incidence of total adverse reactions | 0.294 |

| The incidence of liver function abnormalities | 0.495 |

| The incidence of gastrointestinal reactions | 0.141 |

| The CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels | 0.510 |

Egger’s test for publication bias in outcome indicators after Baihe Gujin Decoction combined with anti-tuberculosis drugs for the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis.

To further evaluate the impact of publication bias on the clinical efficacy rate, a trim and fill analysis was conducted. Figure 7I illustrates the results after adjusting for potential missing studies that could cause asymmetry. The inclusion of data from eight hypothetical studies, derived from the trim and fill method, was used to re-estimate the effect size. The adjusted results showed a heterogeneity test Q-value of 26.672, with a log OR of 1.434 and a 95% CI of (1.180, 1.688). This suggests that the initial effect size estimation was minimally affected by publication bias, reinforcing the robustness of the study’s findings.

4 Evaluation of the quality of evidence

The quality of evidence for each outcome indicator was assessed using the GRADE pro GDT system, with RCTs without major flaws preset as the highest level of evidence in GRADE. Evidence was evaluated for quality and processed according to five downgrading factors. The results suggested that the quality of evidence was moderate in Changes in Cavities and low quality for the remaining indicators (As shown in Table 4).

TABLE 4

| Outcome indicator | Limitations of the study | Incoherence | Indirect | Inaccuracy | Publish bias | Sample size (C/T) | Quantity of effect (95%CI) | Quality of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Efficacy Rate | Insignificant① | Insignificant | Insignificant | Insignificant | Undetected | 1,242/1,250 | OR = 5.50 (4.18, 7.24) | Low quality |

| Lesion Absorption Rate | Insignificant① | Insignificant | Insignificant | Insignificant | Non-serious | 393/399 | OR = 5.83 (4.08, 8.33) | Low quality |

| Sputum Negative Conversion Rate | Insignificant① | Insignificant | Insignificant | Insignificant | Serious | 683/689 | OR = 2.85 (2.12, 3.83) | Low quality |

| Changes in Cavities | Insignificant① | Insignificant | Insignificant | Insignificant | Serious | 266/271 | OR = 2.35 (1.50, 3.69) | Moderate quality |

| the incidence of liver function abnormalities | Insignificant① | Insignificant | Insignificant | Serious③ | Non-serious | 194/194 | OR = 0.33 (0.16, 0.71) | Low quality |

| the incidence of gastrointestinal reactions | Insignificant① | Insignificant | Insignificant | Insignificant | Serious | 260/260 | OR = 0.53 (0.30, 0.95) | Low quality |

| CD4+ T Lymphocyte Subset Levels | Insignificant① | Serious② | Insignificant | Insignificant | Serious | 206/206 | OR = 4.87 (1.91, 7.83) | Low quality |

GRADE evidence quality evaluation form.

C: control group; T: treatment group; CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

①:Most of the literature does not mention blinding and some of the literature does not mention allocation concealment methods, thus reducing the level of evidence due to risk of bias; ②:I2 > 50%; ③: The study involved a sample size of <400 individuals.

5 Discussion

PTB is characterized by symptoms such as cough, hemoptysis, fever, night sweats, and weight loss. Despite advances in TB management, it remains a significant global health challenge, with high incidence and mortality rates (Zhuang et al., 2020; Gong et al., 2024; Gong and Du, 2024a). The effectiveness of current chemotherapy treatments is increasingly compromised by the emergence of multidrug-resistant TB strains. TCM, with its long-standing understanding of TB, emphasizes the importance of lung health and the potential spread to other organs. The TCM approach to treating TB focuses on strengthening the lungs, eradicating the disease, and eliminating pathogens. There is a growing body of evidence highlighting the therapeutic benefits of BGD in TB treatment, advocating for its broader clinical application (Pan et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2022; Yuan and Zhao, 2018).

BGD, a renowned anti-TB formulation derived from “Shenzhai Yishu,” is frequently utilized as an adjunct to conventional TB treatment. It is composed of Lilium Lancifolium Thunb, R. glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC., Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels, P. lactiflora Pall., G. uralensis Fisch. ex DC., P. grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC., S. ningpoensis Hemsl, F. cirrhosa D. Don, and O. japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. It is favored for its capacity to enhance clinical efficacy and modulate immunological responses. Modern pharmacological studies have revealed that BGD contains various bioactive metabolites, including saponins, polysaccharides, phenolic glycerides, flavonoids, and alkaloids (Zhou J. et al., 2021). For example, Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. has been shown to possess anti-inflammatory effects by modulating specific inflammatory pathways (Kwon et al., 2010). Kwon et al. found that anti-inflammatory effects of methanol extracts of the root of Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. are due to downregulation of iNOS and COX-2 via suppression of NF-κB activation and nuclear translocation as well as blocking of ERK and JNK signaling in LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) stimulated Raw264.7 cells (Kwon et al., 2010). Some studies have found that polysaccharides extracted from Lilium Lancifolium Thunb. have immune-enhancing effects and can achieve immune enhancement by increasing monocyte macrophage phagocytic activity, thymic and splenic indices, serum-specific antibody capacity, and proliferation of splenocytes in mice (Pan et al., 2017; Mi et al., 2007). Among them, the thymic and splenic indices reflect the state of the immune system in experimental animals, and changes in their weights may be associated with changes in immune function (Calculation Formula: thymic index = Thymus Weight (mg)/Animal Body Weight (g); splenic index = Spleen Weight (mg)/Animal Body Weight (g)). The polysaccharide extracted from R. glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC can enhance cellular immune function. Zhou et al. found that two polysaccharides (SDH-WA and SDH-0.2A) extracted from R. glutinosa (Gaertn.) DC showed cytotoxic effects on RAW264.7 cells, significantly promoted their phagocytic activity and induced the production of TNF-α and IL-6 in RAW264.7 cells (Zhou Y. et al., 2021). The extracted from Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels exert an anti-inflammatory effect on LPS-induced RAW 264.7 via NO-bursting/calcium-mediated JAK-STAT pathway (Kim et al., 2018). Paeonia lactiflora Pall. has stronger antioxidant activity (Sun et al., 2022), in addition, its extracts are effective in alleviating mucus producing respiratory inflammation, through inhibits the production of MUC5AC mucin protein and gene expression in TNF-α-induced H292 cells and may be closely related to the modulation of the activation of the ERK signaling pathway (Han et al., 2023). Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. ex DC. may exert anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting the release of pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines and down-regulating the expression of iNOS and COX-2 mRNA (Jiang et al., 2021). It has been found that the extracted from S. ningpoensis Hemsl. may exert anti-inflammatory effects by modulating the NF-κB signaling pathway (Shin et al., 2020). Fritillaria cirrhosa D. Don may exert anti-inflammatory effects through various pathways. It has been found that the extracted from F. cirrhosa D. Don can mitigate pulmonary structural impairment and inhibit inflammatory responses by mediating expression of cytokines, such as IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, NF-κB, TGF-β1, MMP-9, and TIMP-1 (Wang et al., 2016). Ophiopogon japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. is a Chinese herb with immunomodulatory effects, and malt polysaccharide is a significant member of its composition. Zhou et al. found that the polysaccharide extracted from O. japonicus (Thunb.) Ker Gawl. could attenuate macrophage damage induced by LPS, reduce inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, inhibit the activation of NF-κB signaling pathway, reduce oxidative stress, and decrease the secretion of inflammatory factors (Zhou et al., 2019). In conclusion, BGD can effectively assist in treating tuberculosis thanks to the synergistic effect of multiple botanical drugs. Polysaccharides from P. grandiflorus (Jacq.) A.DC. can increase the proliferative activity of lymphocytes, promote the progression of the lymphocyte cycle from the G0/G1 phase to the S and G2/M phases and, and simultaneously, increase the levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Zhao et al., 2017). Specifically speaking, when MTB infects the human body, it triggers both innate and adaptive immune responses, and CD4+ T cells, a subset of T lymphocytes, are crucial in TB immunomodulation (Zhuang et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023; Jiang et al., 2023). In previous studies, mice or human lacking CD4+ T cells are more susceptible to TB, highlighting their key role in the disease’s immunology (Leveton et al., 1989; Gong and Du, 2024b; Gong and Du, 2023; Gong et al., 2023; Yang et al., 2023). The findings of this meta-analysis indicate that BGD, in combination with anti-TB Chemotherapy, can significantly increase CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels, suggesting an immunomodulatory effect (Yang et al., 2021; Xie et al., 2023). Meanwhile, specific botanical drug metabolites can regulate the immune function, thereby improving the clinical symptoms and accelerating the recovery process of TB patients. However, whether there is a direct link between these mechanisms of action still needs to be demonstrated in further studies.

Although biomedicine has significant efficacy in treating pulmonary tuberculosis, which is currently our clinical preference, the inevitable adverse reactions remain. Combining TCM with biomedicine to assist in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis has achieved integration of Chinese and biomedicine, complementing each other’s strengths and weaknesses, accelerating the improvement of patients’ conditions, thereby improving the treatment efficacy and reducing the incidence of adverse reactions. In addition to Baihe Gujin Decoction, Chinese patent medicine for treating of pulmonary tuberculosis also includes various Chinese medicines, such as JieHeWan, Shen Ling Bai Zhu San, Astragalus Injection, and TanReqing Injection, from the increase in clinical effectiveness, reduction in sputum culture conversion rate and incidence of adverse reactions, it can be seen that the effectiveness of treating pulmonary tuberculosis with the combination of Chinese medicine and anti-tuberculosis drugs is better than using anti-tuberculosis drugs alone, and is safer (Yan and Gao, 2017; Ding et al., 2017). They play a complementary role to a certain extent, possibly by inhibiting inflammatory cytokines to reduce pulmonary inflammation, enhance immune function, and accelerate recovery. However, given the complexity and individual differences of Chinese medicine, it is particularly important to use it reasonably and safely. Botanical drug decoctions are not like fixed commercial Chinese polyherbal preparations (CCPP), they can be adjusted flexibly according to the patient’s condition, controlling the intake amount from the source to further reduce the incidence of adverse reactions in patients. In addition to the therapeutic effect, the potential interaction of BGD with traditional anti-TB Chemotherapy is also of concern. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the combination of the two treatments can more effectively reduce inflammatory factor levels in patients, enhance their immune function, and result in no significant adverse reactions (Guo, 2014; Liu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024).

This meta-analysis systematically reviewed 32 RCTs, showing that BGD combined with anti-TB Chemotherapy is significantly more effective and safer than conventional chemotherapy alone. The findings are multifaceted: (1) A rigorous literature search was conducted across seven databases, adhering to PRISMA guidelines and yielding studies with a moderate Jadad score; (2) Various outcome measures revealed the efficacy and safety advantages of BGD combination therapy for PTB; (3) The combination therapy significantly reduced the incidence of total adverse reactions; (4) The therapy also significantly increased CD4+ T lymphocyte subset levels; (5) High heterogeneity and publication bias were addressed through sensitivity analysis and statistical tests, confirming the robustness of the results.

However, this study has several limitations that warrant consideration. First, the methodological quality of included RCTs exhibited significant heterogeneity, with common issues including limited sample sizes, inconsistent treatment protocols across studies, and insufficient reporting of randomization procedures. Second, substantial variations in BGD dosage regimens (e.g., decoction concentration, administration frequency) and observation periods were noted, compounded by the absence of standardized efficacy evaluation criteria. Third, critical phytochemical parameters—such as the mass ratios of constituent herbs and extraction methodologies—were frequently omitted in original studies, potentially undermining the pharmacological reproducibility and cross-trial comparability. Furthermore, methodological shortcomings (e.g., lack of blinding and allocation concealment) may have introduced selection and performance biases.

To address these limitations, future investigations should prioritize large-scale, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with rigorous allocation concealment. Concurrently, establishing standardized quality control protocols for BGD preparation and harmonized clinical endpoints is imperative. As mechanistic studies continue to elucidate BGD’s multi-target pharmacological actions—particularly its immunomodulatory and organ-protective properties—this formulation holds promising potential for expanded therapeutic applications in both disease prevention and integrated management strategies.

6 Conclusion

This meta-analysis, encompassing 32 RCTs, demonstrates that BGD can enhance clinical efficacy, facilitate lesion regression, and mitigate the side effects of pharmaceutical drugs, underscoring its therapeutic potential as an adjuvant treatment for PTB. The results indicate that BGD may offer significant benefits in the management of PTB, contributing to a more effective and safer treatment strategy. However, the quality of evidence, as indicated by the Jadad score, varies, with many studies falling into the moderate or low quality categories. This variability underscores the need for future research to be conducted with greater methodological rigor. Large-scale, randomized, double-blind, high-quality trials are essential to further substantiate the efficacy and safety of BGD in the treatment of PTB.

As we look to the future, it is anticipated that an increasing number of high-quality RCTs will be conducted on a global scale. With these studies, the mechanisms of action of BGD in vivo will be elucidated with greater clarity. This enhanced understanding will not only bolster the evidence base for BGD’s role in PTB treatment but also expand its application in the broader spectrum of disease prevention and management.

Statements

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study were included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Author contributions

YZ: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Software. YH: Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – original draft. JL: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. HN: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. PW: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. YL: Data curation, Methodology, Writing – original draft. JL: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. WG: Conceptualization, Visualization, Writing – review and editing.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the reviewers and editors for their excellent contributions to the improvement of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1538692/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

BGD, Baihe Gujin Decoction; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MTB, M. tuberculosis; ORs, Odds ratios; PTB, pulmonary tuberculosis; RCTs, randomized controlled trials; TB, tuberculosis; TCM, traditional Chinese medicine; WMDs, weighted mean differences; commercial Chinese polyherbal preparations (CCPP).

References

1

Chang Y. Jin Z. (2020). Clinical effect of integrated traditional Chinese and western medicine on pulmonary tuberculosis. Shenzhen J. Integr. Tradit. Chin. West Med.30, 35–37. 10.16458/j.cnki.1007-0893.2020.13.018

2

Chen J. (2012). Clinical observation on the treatment of 62 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis with the combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine. J. Psychol. Doc., 135–136. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-8231.2012.04.154

3

Chen J. Guo Z. Zhu Z. (2015). Effectiveness and value of combined Chinese and western medicine treatment methods applied to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Med. Inf., 380. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2015.42.571

4

Chen J. J. Z. N. (2020). Overview of Chinese medicine assisted western medicine in treating tuberculosis. Shandong Zhong Yi Yao Da Xue Xue Bao44, 211–214. 10.16294/j.cnki.1007-659x.2020.02.019

5

Chen L. Zhou Y. (2010). Clinical comparative study on the treatment of cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis with integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine. Pract Clini J. Integr Tradit. Chin. West Med.10, 5–6. 10.3969/j.issu.1671-4040.2010.03.003

6

Chen Z. Wang T. Du J. Sun L. Wang G. Ni R. et al (2025). Decoding the WHO global tuberculosis report 2024: a critical analysis of global and Chinese key data. Zoonoses5, 1. 10.15212/zoonoses-2024-0061

7

Cheng H. Li Y. Zhai Y. (2020). Clinical trial on the modified Baihe Gujin Decoction combined with routine chemotherapy for the elderly patients with primary treated pulmonary tuberculosis and lung-kidney yin deficiency. Int. J. Trad. Chin. Med.42, 842–846. 10.3760/cma.j.cn115398-20190210-00026

8

Ding F. Zheng Y. Chen Y. Wen W. Gu Y. (2017). Treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis with the addition and subtraction of shen ling Bai Zhu san, systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. Nei Mongol J. Traditional Chin. Med.36, 106–107. 10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2017.07.095

9

Fan Z. Zhao Z. Chen H. (2021). Study on the effect of baihe gujin decoction combined with anti-tuberculosis western medicine on focal absorption and cavity closure of pulmonary tuberculosis patients. Guangming Tradit. Chin. Med.36, 3676–3678. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-8914.2021.21.041

10

Ge H. B. Zhu J. (2020). Clinical efficacy of Baihe Gujin decoction combined with anti-tuberculosis therapy for pulmonary tuberculosis with Yin-deficiency and Fire-hyperactivity syndrome. J. Int. Med. Res.5, 300060519875535. 10.1177/0300060519875535

11

Gong W. Du J. (2023). Excluding participants with mycobacteria infections from clinical trials: a critical consideration in evaluating the efficacy of BCG against COVID-19. J. Korean Med. Sci.38, e343. 10.3346/jkms.2023.38.e343

12

Gong W. Du J. (2024a). Optimising the vaccine strategy of BCG, ChAdOx1 85A, and MVA85A for tuberculosis control. Lancet Infect. Dis.24, 224–226. 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00514-5

13

Gong W. Du J. (2024b). Optimising the vaccine strategy of BCG, ChAdOx1 85A, and MVA85A for tuberculosis control. Lancet Infect. Dis.24, 224–226. 10.1016/s1473-3099(23)00514-5

14

Gong W. Du J. Aspatwar A. Zhuang L. Zhao Y. (2024). Revisiting Bacille Calmette‐Guérin revaccination strategies: timing of immunization, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and non‐tuberculous mycobacteria infections, strain potency and standardization of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Transl. Discov.4, e301. 10.1002/ctd2.301

15

Gong W. Liu Y. Xue Y. Zhuang L. (2023). Two issues should be noted when designing a clinical trial to evaluate BCG effects on COVID-19. Front. Immunol.14, 1207212. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1207212

16

Guo F. L. (2014). Observation of curative effect on initial treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis by combining traditional Chinese and Western medicine. Inn. Mongo. J. Tradit. Chin. Med., 54–55. 10.16040/j.cnki.cn15-1101.2014.04.076

17

Han S. Y. Lim S. K. Kim H. J. (2023). Effect of Paeoniae Radix Rubra (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) extract on mucin secretion, gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. J. Ethnopharmacol.303, 115959. 10.1016/j.jep.2022.115959

18

Han X. Bao Y. Li Z. (2011). Observations on 40 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis in the elderly treated with Baihe Gujin Tang combined with chemotherapy. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Med.27, 611. 10.3969/j.issn.1004-2814.2011.09.023

19

Jia W. (2013). Observation on the therapeutic effect of 118 cases of hemoptysis in pulmonary tuberculosis treated with combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine. Guide Chin. Med.11, 693–694. 10.15912/j.cnki.gocm.2013.17.082

20

Jia Y. R. Li T. L. Li X. X. Xu S. B. Pan M. D. (1992). Thin layer chromatography for identification of 9 species of traditional Chinese medicine in baihe gujin tang granules. China J. Chin. Mat. Med.17, 410–411+445.

21

Jiang F. Wang L. Wang J. Cheng P. Shen J. Gong W. (2023). Design and development of a multi-epitope vaccine for the prevention of latent tuberculosis infection. Med. Adv.1, 361–382. 10.1002/med4.40

22

Jiang L. Akram W. Luo B. Hu S. Faruque M. O. Ahmad S. et al (2021). Metabolomic and pharmacologic insights of aerial and underground parts of Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch. Ex DC. For maximum utilization of medicinal resources. Front. Pharmacol.12, 658670. 10.3389/fphar.2021.658670

23

Ju W. (2019). Analysis of symptom regression of pulmonary tuberculosis treated with Baihe Gujin Tang plus western medicine. Heal-Readma21.

24

Kim Y. J. Lee J. Y. Kim H. J. Kim D. H. Lee T. H. Kang M. S. et al (2018). Anti-inflammatory effects of Angelica sinensis (Oliv.) Diels water extract on RAW 264.7 induced with lipopolysaccharide. Nutrients10, 647. 10.3390/nu10050647

25

Kwon O. K. Lee M. Y. Yuk J. E. Oh S. R. Chin Y. W. Lee H. K. et al (2010). Anti-inflammatory effects of methanol extracts of the root of Lilium lancifolium on LPS-stimulated Raw264.7 cells. J. Ethnopharmacol.130, 28–34. 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.002

26

Lei FY L. D. Wang B. (2006). Disease diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis with evidence-based treatment. Shan Xi Zhong Yi4, 454–455. CNKI:SUN:SXZY.0.2006-04-050.

27

Leveton C. Barnass S. Champion B. Lucas S. De S. B. Nicol M. et al (1989). T-cell-mediated protection of mice against virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect. Immun.57, 390–395. 10.1128/iai.57.2.390-395.1989

28

Li H. Z. Gao X. Cao X. J. Liu D. D. Li Z. (2024). Effect of added Lilihe Gujin Decoction on CD4+ T cell subsets and prognosis of patients with rifampicin-sensitive pulmonary Yin deficiency pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin. Archi. Tradit. Chin. Med., 1–6.

29

Li L. Yang L. Zhuang L. Ye Z. Zhao W. Gong W. (2023). From immunology to artificial intelligence: revolutionizing latent tuberculosis infection diagnosis with machine learning. Mil. Med. Res.10, 58. 10.1186/s40779-023-00490-8

30

Li N. (2019). Analyzing the clinical effect of Baihe Gujin Tang plus reduction combined with anti-tuberculosis drugs in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Diet. Heal. Care6, 104–105.

31

Li Y. (2011). Clinical observation on Chinese and western medicine combined treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Clini Pulm. Med.16, 150–151. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6663.2011.01.095

32

Li Y. (2016). Clinical observation on hemoptysis in pulmonary tuberculosis treated with combination of Chinese and western medicine. Shenzhen J. Integr. Tradit. Chin. West Med.26, 38–39. 10.16458/j.cnki.1007-0893.2016.08.017

33

Liang Y. Gong W. P. Wang X. M. Zhang J. X. Ling Y. B. et al (2021). Chinese traditional medicine NiuBeiXiaoHe (NBXH) extracts have the function of antituberculosis and immune recovery in BALB/c mice. J. Immunol. Res.2021, 6234560. 10.1155/2021/6234560

34

Liu X. Guo S. H. Guo R. X. Wu C. H. Wang W. H. (2023). Effects of adjuvant therapy of modified baihe gujin decoction combined with western medicine on immune function of retreated pulmonary tuberculosis patients and its safety. J. Guangzhou Univ. Tradit. Chin. Med., 1890–1895. 10.13359/j.cnki.gzxbtcm.2023.08.006

35

Liu Y. (2018). Clinical effect of baihegujin decoction combined with western medicine in the treatment of multi drug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis and its influence on immune function. Drug Eval.15, 57–60. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2809.2018.06.015

36

Liu Y. J. Wang R. Liu Q. Zhong K. (2022). Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Baihe Gujin Decoction combined with 2HRZE/4HR regimen in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin. Sci. Techn J.

37

Ma C. (2020). Study on the therapeutic effect of Baihe Gujin Decoction on pulmonary tuberculosis. Diet. Heal. Care7, 103.

38

Mi M. Ren L. Mei Q. Li F. Wang D. Liu S. (2007). Effects of polysaccharides from Lily on immune functions of mice. J. Fourth Mil. Med. Univ., 2034–2036.

39

Pan G. Xie Z. Huang S. Tai Y. Cai Q. Jiang W. et al (2017). Immune-enhancing effects of polysaccharides extracted from Lilium lancifolium Thunb. Int. Immunopharmacol.52, 119–126. 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.08.030

40

Pan J. Liu T. Huang J. Huang T. (2022). Observation of clinical effect of modified Baihe Gujin decoction in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis patients. J. Pract. Med.38, 1614–1617.

41

Peng C. Jiang F. Liu Y. P. Xue Y. Cheng P. Wang J. et al (2024). Development and evaluation of a promising biomarker for diagnosis of latent and active tuberculosis infection. Infect. Dis. and Immun.4, 10–24. 10.1097/id9.0000000000000104

42

Shin N. R. Lee A. Y. Song J. H. Yang S. Park I. Lim J. O. et al (2020). Scrophularia buergeriana attenuates allergic inflammation by reducing NF-κB activation. Phytomedicine67, 153159. 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.153159

43

Su HT L. T. Lv H. Q. Deng K. Wang M. Ma G. R. Han T. L. (2020). Overview of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of multidrug-resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin. J. Chin. Med.12, 140–143. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7860.2020.24.054

44

Sun X. Chen L. Yan H. Cui L. Hussain H. Xie L. et al (2022). An efficient high-speed counter-current chromatography method for the preparative separation of potential antioxidants from Paeonia lactiflora Pall. combination of in vitro evaluation and molecular docking. J. Sep. Sci.45, 1856–1865. 10.1002/jssc.202200082

45

Sun Y. (2016). Clinical observation of baihe gujin decoction combined with chemotherapy in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin. Med. Mode Dist. Educ. Chin.14, 101–103. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2016.11.046

46

S., W. 36 Cases of (2014). Pulmonary tuberculosis treated with combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine. Chin. Med. Mode. Dist. Educ. Chin.12, 54–55. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2014.04.03

47

Wang C. Z. W. (2004). Influence of Baihe Gujin decoction on medicamentous liver lesion caused by antiphthisic medicine. Hubei J. Tradit. Chin. Med.40.

48

Wang D. Du Q. Li H. Wang S. (2016). The isosteroid alkaloid imperialine from bulbs of Fritillaria cirrhosa mitigates pulmonary functional and structural impairment and suppresses inflammatory response in a COPD-like rat model. Mediat. Inflamm.2016, 4192483. 10.1155/2016/4192483

49

Wang K. Li L. Wang Y. Fang G. Wei M. Ding H. et al (2022). Effect of Baihe Gujin decoction combined with Shengmai powder on the expression of IL-1β and IL-1Ra in peripheral blood CD14+ monocytes from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Cell Mol. Biol. (Noisy-le-grand)68, 60–63. 10.14715/cmb/2022.68.2.9

50

Wang L. (2013). Rondom parallel control study of baihegujintang treated recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Prac. Tradit. Chin. Med.27, 104–105. CNKI:SUN:SYZY.0.2013-07-055.

51

Wang M. Wang H. Cao X. (2020a). Clinical study on baihe gujin tang combined with 2HRZE/4HR regimen for multi-drug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. New J. Tradit. Chin. Med.52, 20–23. 10.13457/j.cnki.jncm.2020.06.007

52

Wang S. (2014). 36 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis treated with combination of traditional Chinese and western medicine. Chin. Med. Mode. Dist. Educ. Chin.12, 54–55. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2014.04.03

53

Wang Y. (2015). Therapy of integrated medicine in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis for 53 cases. Chin. Med. Mode. Dist. Educ. Chin.13, 71–73. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-2779.2015.24.037

54

Wang Y. He Y. Wang L. Zhang Y.-A. Wang M.-S. (2023). Diagnostic yield of nucleic acid amplification tests in oral samples for pulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis.10, ofad082. 10.1093/ofid/ofad082

55

Wang Y. Huang Y. Liu Y. (2020b). Observation on the curative effect of chemotherapy assisted with Baihe Gujin Decoction on multidrug resistance tuberculosis. Mod. J. Integr. Tradit. Chin. West. Med.29, 4034–4037. 10.3969/j.issn.1008-8849.2020.36.010

56

Wei F. (2015). Observation of the effect and clinical significance of combined Chinese and Western medicine treatment methods applied to patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. E-J Transl. Med.2, 65–66. CNKI:SUN:ZHDZ.0.2015-03-033.

57

WHO (2024). Global tuberculosis report 2024. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1–68.

58

Xiao C. (2020). Clinical evaluation of baihe gujin decoction combined with antituberculosis drugs in the treatment of 82 cases of pulmonary tuberculosis and hemoptysis. Chin. Med.221.

59

Xie F. Huang W. Meng X. Li S. Li J. (2023). Clinical efficacy of Baihe Gujin Decoction combined with anti-tuberculosis drugs on patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and T-lymphocyte subpopulations. Mod. Med Heal Res.7, 89–92.

60

Xiong S. (2019). Clinical observation on the treatment of pulmonary yin deficiency in secondary tuberculosis with the addition and subtraction of Baihe Gujin Tang. J. Prac. Tradit. Chin. Med.35, 1139–1140. CNKI:SUN:ZYAO.0.2019-09-066.

61

Yan B. Gao Y. (2017). Meta-analysis of conventional anti-tuberculosis chemotherapy combined with Chinese patent medicine JieHeWan in the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. Chin. J. Traditional Med. Sci. Technol.24, 533–537.

62

Yang C. Wang Q. Chen T. Ma M. (2022). Observation on the effect of adjuvant treatment of recurrent pulmonary tuberculosis with Baihe Gujin decoction and its influence on T cell subsets. Chin. J. Tradit. Med. Sci. Technol.29, 876–878.

63

Yang H. Fang Y. Gong X. (2016). Thirty-five cases of depression treated with in combination with method of activating brain for resuscitation. Henan Traditi. Chin. Med.36, 1094–1096. 10.16367/j.issn.1003-5028.2016.06.0455

64

Yang L. Zhuang L. Ye Z. Li L. Guan J. Gong W. (2023). Immunotherapy and biomarkers in patients with lung cancer with tuberculosis: recent advances and future Directions. iScience26, 107881. 10.1016/j.isci.2023.107881

65

Yang Y. Zhang Y. Dong L. (2021). Effect of baihe gujin decoction combined with standard anti-tuberculosis regimen on serum inflammatory factor levels in elderly pulmonary tuberculosis patients with pneumonia. Word J. Integr. Tradit. West Med.16, 1967–1971. 10.13935/j.cnki.sjzx.211102

66

Ye W. (2014). Clinical observation on combination of Chinese and western medicine in treating pulmonary tuberculosis. J. Pract. Tradit. Chin. Med.30, 45–46. CNKI:SUN:ZYAO.0.2014-01-042.

67

Yuan Y. Zhao W. (2018). Clinical observation on the treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis with the addition and subtraction of Baihe Gujin Tang combined with anti-tuberculosis drugs. Chin. Naturo26, 55–56. 10.19621/j.cnki.11-3555/r.2018.0338

68

Zhang H. (2017). Treatment of 50 cases of initially treated pulmonary tuberculosis with positive sputum smear by baihe gujin decoction in combination with standard chemotherapy. Shandong J. Tradit. Chin. Med.36, 945–947. 10.16295/j.cnki.0257-358x.2017.11.010

69

Zhang J. (2023). Baihe gujin decoction combined with conventional anti-tuberculosis regimen in treating senile pulmonary tuberculosis. Acta Chin. Med.38, 638–643. 10.16368/j.issn.1674-8999.2023.03.105

70

Zhang Z. (2022). Effects of Baihe Gujin decoction in treatment of patients with retreatment active pulmonary tuberculosis and its inffuence on liver function. Med. J. Chin. Peop. Heal.34, 84–87. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2022.15.025

71

Zhao M. Wang Y. (2020). Effect of Baihe Gujin decoction combined with standard chemotherapy regimen on T-lymphocyte subsets in patients with relapsed tuberculosis. J. Aeros. Med.31, 173–175. CNKI:SUN:HKHT.0.2020-02-025.

72

Zhao X. Wang Y. Yan P. Cheng G. Wang C. Geng N. et al (2017). Effects of polysaccharides from Platycodon grandiflorum on immunity-enhancing activity in vitro. Molecules22, 1918. 10.3390/molecules22111918

73

Zheng L. (2015). Clinical observation of combining Chinese medicine with chemical medicine on MED-TB. Chin. Med.And Pharm.5, 43–45+48. CNKI:SUN:GYKX.0.2015-12-014.

74

Zhong Y. Fan S. Wen W. (2021). Treatment of 46 cases of Yin deficiency and fire exuberance type of first-treatment coated-yang pulmonary tuberculosis by adding flavor to Baihe Gujin decoction. Hunan J. Traditional Chin. Med.37, 35–37. 10.16808/j.cnki.issn1003-7705.2021.02.013

75

Zhou J. (2020). Curative observation of using baihe gujin decoction combined with feilao decoction in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis of yin-deficiency heat-excess syndrome. J. Sichuan Tradit. Chin. Med.38, 73–76. CNKI:SUN:SCZY.0.2020-08-027.

76

Zhou J. An R. Huang X. (2021a). Genus Lilium: a review on traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol.270, 113852. 10.1016/j.jep.2021.113852

77

Zhou M. Yuan H. Wu S. (2019). Protective effects and mechanism of ophiopogon japonicus polysaccharide on lipopolysaccharide-induced macrophage damage. Pharm. Clin. Res.27, 416–420. 10.13664/j.cnki.pcr.2019.06.004

78

Zhou Y. Wang S. Feng W. Zhang Z. Li H. (2021b). Structural characterization and immunomodulatory activities of two polysaccharides from Rehmanniae Radix Praeparata. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.186, 385–395. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.06.100

79

Zhuang L. Yang L. Li L. Ye Z. Gong W. (2020). Mycobacterium tuberculosis: immune response, biomarkers, and therapeutic intervention. MedComm2024, e419. 10.1002/mco2.419

80

Zhuang L. Ye Z. Li L. Yang L. Gong W. (2023). Next-generation TB vaccines: progress, challenges, and prospects. Vaccines (Basel)11, 1304. 10.3390/vaccines11081304

Summary

Keywords

pulmonary tuberculosis, Baihe Gujin decoction, anti-tuberculosis drugs, meta-analysis, randomized controlled trial

Citation

Zhao Y, Han Y, Liu J, Niu H, Wang P, Li Y, Liang J and Gong W (2025) Efficacy and safety of baihe gujin decoction as an adjunct to chemotherapy in pulmonary tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1538692. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1538692

Received

03 December 2024

Accepted

23 April 2025

Published

13 May 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Zifeng Yang, Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Health, China

Reviewed by

Jun Jiao, Academy of Military Medical Sciences (AMMS), China

Hao Li, Beijing Institute of Microbiology and Epidemiology, China

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhao, Han, Liu, Niu, Wang, Li, Liang and Gong.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jianqin Liang, ljqbj309@163.com Wenping Gong, gwp891015@whu.edu.cn

†These authors have contributed equally to this work to the study and shared the first author position.

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.