Abstract

Objective:

Investigate the high risk factors contributed to voriconazole-induced liver injury and develop a predictive nomogram for voriconazole-induced liver injury risk, thereby optimizing the clinical medication safety.

Methods:

This observational study retrospectively analyzed the electronic health records of hospitalized patients who received voriconazole treatment or prophylaxis at a tertiary hospital. Patients who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled between June 2020 and June 2024, and their general biological data were collected. The diagnosis and severity grading of voriconazole-associated liver injury were determined according to the diagnostic and treatment guidelines for drug-induced liver injury. Patients were categorized into liver injury and non-injury groups based on the results of post-treatment liver function tests. Associations between baseline characteristics and liver injury were analyzed using non-parametric and chi-squared tests. To avoid omitting potentially significant factors, variables demonstrating P ≤ 0.1 in univariate screening and retained through least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression underwent multivariate logistic regression to identify independent predictors. The nomogram was developed and internally validated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis, calibration curves, and decision curve analysis (DCA).

Results:

Among the 1,964 patients screened, 1,196 were excluded, leaving 768 patients included in the statistical analysis. Liver injury occurred in 95 patients, resulting in an incidence rate of 12.4%. Multivariable logistic regression analysis demonstrated that total cholesterol (TC) (OR = 1.893, P < 0.01), concomitant use of glucocorticoids (OR = 1.861, P = 0.041), ezetimibe (OR = 7.453, P = 0.047), and caspofungin (OR = 2.485, P = 0.032). Patients with TC levels exceeding 4.485 mmol/L exhibited a significantly elevated risk of liver injury. ROC analysis revealed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.728 (95% CI: 0.66–0.797), with a sensitivity of 0.661 and specificity of 0.722. Internal validation indicated good discrimination and calibration, with predicted probabilities closely aligned with actual outcomes. The decision curve analysis suggested a substantial net clinical benefit. These findings were subsequently validated in a test cohort.

Conclusion:

Concomitant use of ezetimibe, caspofungin, glucocorticoids, and TC levels exceeding 4.485 mmol/L are independent risk factors for voriconazole-induced liver injury. The developed nomogram model offers clinically meaningful predictions for drug-induced liver injury risk, facilitating the optimization of voriconazole therapy safety.

1 Introduction

Invasive Fungal Infections (IFD) typically occur in individuals with severely compromised immune systems, impaired host barrier functions, or exposure to high-risk environments (Taccone et al., 2015; Perreault et al., 2019; Boutin et al., 2024). Voriconazole, a broad-spectrum triazole antifungal, is extensively employed in treat severe IFD (Patterson et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2022). However, as the clinical use of voriconazole has increased, adverse effects such as drug-induced liver injury (DILI), neurotoxicity, visual disturbances, and gastrointestinal reactions have become more prevalent (Jin et al., 2016). Among these, DILI is the most common and severe adverse reaction, and it is a major reason for treatment discontinuation. DILI can be categorized into non-idiosyncratic and idiosyncratic types. Non-idiosyncratic liver injury is dose- or duration-dependent, with a short latency period, and is attributed to direct hepatotoxicity from drugs or their metabolites (Tiwari et al., 2025). In contrast, voriconazole-associated DILI is primarily idiosyncratic and linked to individual genetic and metabolic variations, as well as immune responses, with no clear dose dependency. Conventional animal toxicology studies often fail to accurately predict clinical toxicity risks in such cases (Tiwari et al., 2025; Du et al., 2023). Recent studies have reported a DILI incidence of 12.9%–32.45% during voriconazole therapy (Perreault et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2022; Hanai et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022), highlighting it as a critical safety concern in clinical practice. Early identification and timely intervention can significantly mitigate these risks; however, there remains a lack of specific predictive tools for voriconazole-related liver injury.

Voriconazole-induced DILI has been linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and disrupted bile acid homeostasis (Watkins, 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Critically, the specific targets responsible for the induction of liver injury remain unidentified. Therefore, it is crucial to elucidate the risk factors associated with voriconazole-induced DILI and to predict its occurrence following voriconazole administration. Previous studies have employed machine learning algorithms to develop predictive models. These models utilized clinical features to forecast voriconazole trough plasma concentrations, aiding in liver injury risk assessment (Cheng et al., 2023). Furthermore, comparisons among various machine learning models revealed that the logistic regression model exhibited superior performance in predicting voriconazole-related hepatotoxicity (Ma et al., 2023). Despite the development of these models, limitations persist, including inadequate interpretability, a strong dependence on clinical features, and a lack of intuitive visualization of the risk assessment process in clinical applications.

This study delineates key predictors of voriconazole-associated DILI and to develop a nomogram-based risk prediction model utilizing the identified independent risk factors. This approach addresses the limitations of existing research by enhancing model interpretability and clinical utility, thereby facilitating individualized dosing regimens and improving medication safety.

2 Population and methods

2.1 Patients

This study retrospectively analyzed the electronic health records of patients who used voriconazole for therapeutic and prophylactic indications of invasive fungal diseases at The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University from June 2020 to June 2024.

Inclusion criteria: age ≥18 years, who received voriconazole for the treatment or prophylaxis of IFD, underwent liver function biochemical tests during voriconazole therapy, and had all baseline liver function indices (prior to voriconazole initiation) within the upper limit of normal (ULN).

Exclusion criteria: age <18 years; presence of liver injury caused by viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hepatic failure, alcohol-related liver diseases, metabolic-associated and fatty liver diseases, drug and toxin-induced liver injury, biliary tract diseases, or hepatocellular carcinoma; absence of baseline liver function tests performed before voriconazole initiation; and baseline liver indices (alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (γ-GGT), total bilirubin (T-BiL), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP)) exceeding 1×ULN).

2.2 Methods

The electronic health records of enrolled patients were retrospectively extracted from the hospital’s integrated information system. The data collection encompassed demographic characteristics, therapeutic regimens, serial laboratory parameters (specifically liver function profiles), documented adverse drug reactions (ADRs), and clinical outcomes.

Severity Grading of Acute DILI: Following diagnosis of acute DILI, severity was classified into four grades based on criteria established by the International DILI Expert Working Group: Grade 1 (Mild): ALT ≥ 5×ULN or ALP ≥ 2×ULN with total bilirubin (T-BiL) < 2×ULN. Grade 2 (Moderate): ALT ≥ 5×ULN or ALP ≥ 2×ULN with T-BiL ≥ 2×ULN, or symptomatic hepatitis. Grade 3 (Severe): ALT ≥ 5×ULN or ALP ≥ 2×ULN with T-BiL ≥ 2×ULN, plus one of the following: INR ≥ 1.5, ascites/hepatic encephalopathy, disease duration <26 weeks (without pre-existing cirrhosis), or DILI-induced extrahepatic organ failure. Grade 4 (Fatal): DILI-related death or the necessity for liver transplantation for survival (Meunier and Larrey, 2023).

The causal relationship between liver injury and voriconazole use was evaluated using the Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) (Danan and Teschke, 2015). Patients with a RUCAM score of ≥6 were classified as having highly probable or probable voriconazole-induced drug-induced liver injury. Those with a RUCAM score of <6 were excluded from further risk factor analyses due to insufficient evidence to reliably attribute liver injury to voriconazole therapy.

Diagnosis of Liver Injury Clinical Types: The clinical type of liver injury is classified using the R-value, which is calculated as the ratio of [ALT/(ALT ULN)] to [ALP/(ALP ULN)]. The categories are defined as follows: Hepatocellular Injury (R ≥ 5): Characterized by a predominant elevation of ALT or AST. Cholestatic Injury (R ≤ 2): Defined by elevated ALP and/or γ-GGT. Mixed Pattern (2 < R < 5): Exhibits combined hepatocellular and cholestatic biochemical features (Aithal et al., 2011; Colombo, 2020; Andrade et al., 2019; Freites-Martinez et al., 2021). Classification by Disease Course: Acute Liver Injury: Resolves within 6 months of onset. Chronic Liver Injury: Persists for more than 6 months with unresolved biochemical or histological abnormalities.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Patient data were systematically entered and organized using Microsoft Excel 2020. After thorough verification, the dataset was imported into SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp.) for comprehensive statistical analysis. Normality for all continuous variables was tested with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For non-normally distributed data, between-group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test, with data reported as median (interquartile range). Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation and compared via Student's t-test. Categorical variables underwent χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test when the expected frequencies were less than.

2.4 Feature selection and model development

Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was applied to identify significant risk factors for voriconazole-associated drug-induced liver injury by shrinking the coefficients of less relevant predictors to zero. To avoid omitting potential risk factors, candidate variables selected by both univariate analysis (P ≤ 0.1) and LASSO regression were included in a final multivariable logistic regression model to define independent risk factors (Hanai et al., 2023; Ranganathan et al., 2017).

To ensure a robust and unbiased model evaluation, random stratified sampling was employed to partition the dataset into training and testing sets in a 7:3 ratio. The training set was utilized for model development, while the testing set served for model performance evaluation. The dataset was stratified based on the binary outcome of liver injury occurrence (yes/no). This approach ensured a comparable prevalence of positive events (liver injury = 1) across the two resulting subsets. Within each stratum, a simple random sampling procedure was implemented using a fixed random seed [set.seed (42)] to guarantee the reproducibility of the data split. The class imbalance between positive cases (hepatotoxicity) and negative cases was addressed using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique. A nomogram model was developed using R software (version 4.4.2) to visualize the risk prediction algorithm. The model’s performance was evaluated by its area under the curve (AUC), with internal validation via 1,000 bootstrap resamples to correct for overfitting. Its clinical utility was further quantified using decision curve analysis (DCA).

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

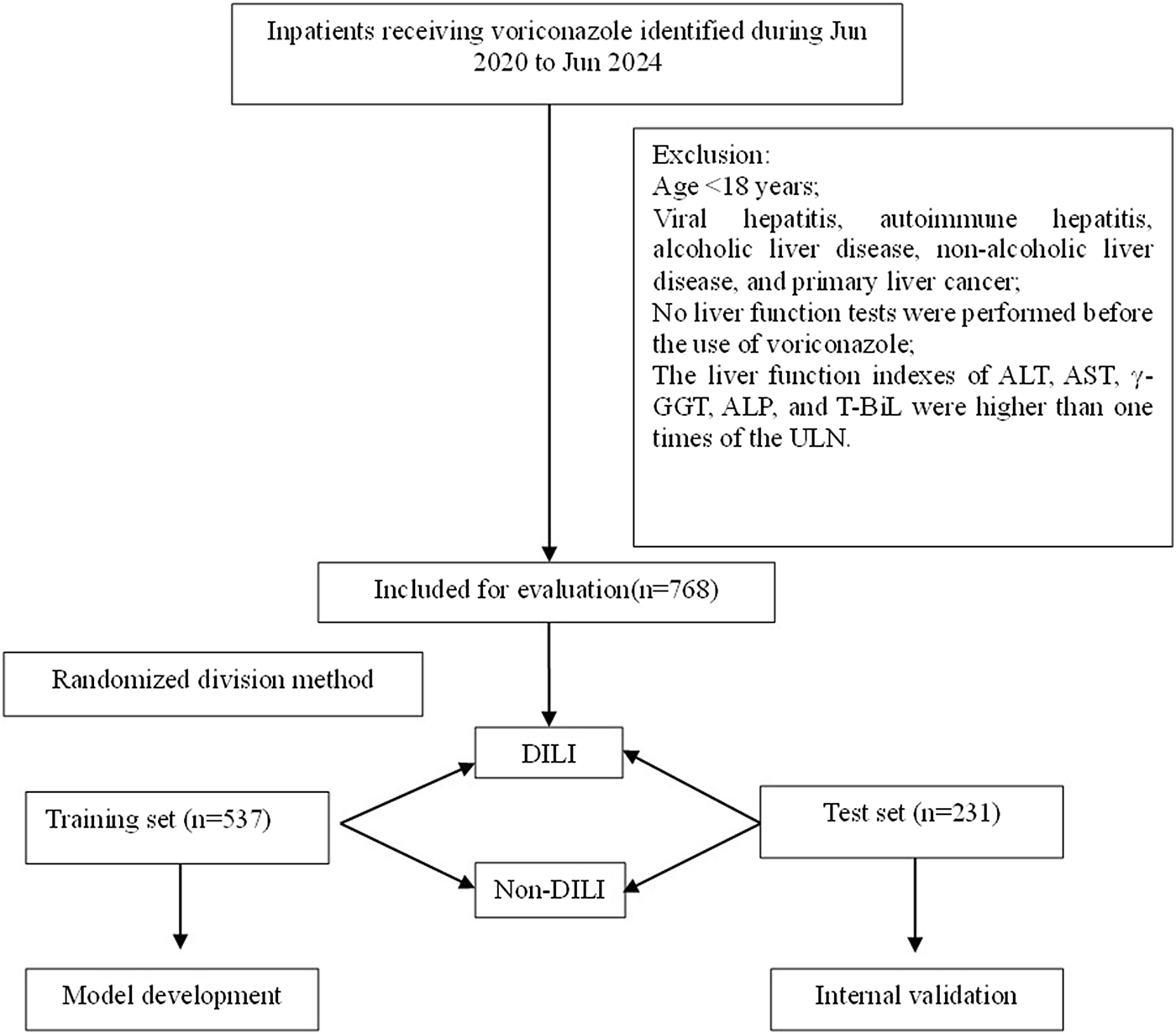

A total of 768 patients who were exposed to voriconazole between June 2020 and June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined in Figure 1. The cohort comprised 487 males (63.4%) and 281 females (36.6%), with 39 patients (5.1%) reported a history of alcohol use and 91 patients (11.8%) had a smoking history.

FIGURE 1

Flowchart of patient inclusion and exclusion.

The majority of patients were from the hematology department (n = 387, 50.4%), followed by the respiratory department (n = 120, 15.6%) and the ICU (n = 108, 14.1%). The identified fungal pathogens included Aspergillus spp. (n = 152, 19.8%), Candida spp. (n = 122, 15.9%), and other fungi (n = 63, 8.2%), such as fungal spores, Lichtheimia corymbifera, Trichosporon asahii, and Pneumocystis jirovecii.

Infections predominantly involved the respiratory system (n = 365, 47.5%), followed by the urinary system (n = 38, 4.9%). Following voriconazole therapy, 508 patients (66.1%) demonstrated clinical improvement. Detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

3.2 Adverse drug reactions, management strategies, and clinical outcomes of voriconazole therapy

A total of 213 patients (27.7%) experienced ADRs during voriconazole therapy, with a median onset time of 4 days. The most common ADR was DILI (n = 95, 12.4%), followed by neurotoxicity (n = 25, 3.3%), visual disturbances (n = 9, 1.2%), and other reactions (n = 24, 3.1%), which included rash, flushing, transient fever, tinnitus, diarrhea, elevated serum creatinine, and palpitations. Among 95 patients with voriconazole-induced liver injury, the severity was graded as 1 in 44 (46.3%), 2 in 30 (31.6%), 3 in 18 (18.9%), and 4 in 3 (3.2%) patients. According to clinical phenotype, the injury was classified as hepatocellular in 33 (34.7%), cholestatic in 42 (44.2%), and mixed in 20 (21.1%) patients.

Management strategies involved switching from oral voriconazole tablets to intravenous formulations for patients experiencing intractable nausea or vomiting, administering hepatoprotective agents (e.g., glutathione, polyene phosphatidylcholine) to those with abnormal liver function, adding mecobalamin for mild neurotoxicity, and discontinuing voriconazole in cases of severe ADRs. These interventions led to symptom resolution or significant improvement in 89.2% of affected patients (n = 190/213). Detailed results are presented in Supplementary Table S1.

3.3 High-risk factors of voriconazole DILI

The study cohort of 768 patients was randomly divided into a training set (n = 537, 70%) and a test set (n = 231, 30%) using a 7:3 allocation ratio. Clinical data from the training set underwent univariate analysis and LASSO regression analysis, followed by logistic regression to identify independent risk factors for voriconazole-induced liver injury. The results of these analyses were summarized in Table 1; Figure 2.

TABLE 1

| Risk factor | Training set (n = 537) | P-value | Test set (n = 231) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DILI (62) | Non-DILI (475) | DILI (33) | Non-DILI (198) | |||

| Basic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 61 (50.5,70) | 62 (48,72) | 0.638 | 66 (42.5,81) | 66 (50,76) | 0.776 |

| Gender (female) | 42 (67.7) | 303 (63.8) | 0.541 | 21 (63.6) | 121 (61.1) | 0.783 |

| Alcohol | 4 (6.5) | 24 (5.1) | 0.641 | 1 (3.0) | 10 (5.1) | 0.594 |

| Smoking | 7 (11.3) | 63 (13.3) | 0.664 | 4 (12.1) | 17 (8.6) | 0.528 |

| Length of hospital stay | 27 (14.5,46.5) | 23 (13,38) | 0.244 | 23 (15,43) | 25 (14,35) | 0.853 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypoproteinemia | 21 (33.9) | 136 (28.6) | 0.394 | 12 (36.4) | 59 (29.8) | 0.449 |

| Malignant tumor | 6 (9.7) | 51 (10.7) | 0.799 | 5 (15.2) | 18 (9.1) | 0.308 |

| Hematologic malignancies | 24 (38.7) | 186 (39.2) | 0.946 | 12 (36.4) | 79 (39.9) | 0.700 |

| Septic shock | 11 (17.7) | 48 (10.1) | 0.071 | 10 (30.3) | 17 (8.6) | 0.001 |

| Hyperuricemia | 3 (4.8) | 38 (8.0) | 0.351 | 0 (0) | 11 (5.6) | 0.062 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1 (1.6) | 23 (4.8) | 0.191 | 2 (6.1) | 10 (5.1) | 0.813 |

| Anemia | 10 (16.1) | 51 (10.7) | 0.208 | 7 (21.2) | 19 (9.6) | 0.071 |

| COPD | 2 (3.2) | 24 (5.1) | 0.506 | 1 (3.0) | 7 (3.5) | 0.881 |

| Hypertension | 17 (27.4) | 151 (31.8) | 0.485 | 12 (36.4) | 61 (30.8) | 0.525 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (25.8) | 89 (18.7) | 0.187 | 10 (30.3) | 31 (15.7) | 0.041 |

| Pretreatment laboratory parameters for voriconazole | ||||||

| Body temperature (°C) | 36.95 (36.7,37.8) | 36.9 (36.5,37.6) | 0.323 | 37 (36.8,38.1) | 36.9 (36.5,37.6) | 0.254 |

| WBC (×109/L) | 8.01 (3.72,12.56) | 6.15 (2.88,9.33) | 0.089 | 9.18 (4.03,12.47) | 6.25 (2.77,8.93) | 0.017 |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 83 (64.83,132.29) | 78.3 (56.9,132.29) | 0.225 | 107.7 (63.5,172.6) | 78 (57.88,132.29) | 0.111 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 8.69 (5.69,12.99) | 6.69 (4.61,12.4) | 0.127 | 11.61 (5.55,20.69) | 7.38 (4.69,11.61) | 0.054 |

| PCT (ng/mL) | 1.32 (0.27,5.25) | 0.48 (0.14,5.25) | 0.048 | 1.04 (0.31,6.06) | 0.46 (0.14,5.25) | 0.034 |

| γ-GGT (U/L) | 32.55 (24.75,47) | 32.55 (25,35) | 0.122 | 37 (29,47.5) | 32.51 (25,37) | 0.02 |

| ALT (U/L) | 17 (11,23.5) | 20 (12,29) | 0.433 | 20 (14,30.5) | 17.5 (12,24.25) | 0.102 |

| AST (U/L) | 20.5 (15,27) | 23 (16,30) | 0.368 | 26 (20.5,31) | 22 (17,28.25) | 0.046 |

| ALB (g/L) | 33.05 (28.7,35.73) | 33.57 (30,38.2) | 0.118 | 32.4 (25.6,37.35) | 33.57 (29.78,37.65) | 0.115 |

| D-BiL (μmol/L) | 3.46 (2.98,4.53) | 3.46 (2.5,3.9) | 0.266 | 2.9 (2.3,3.48) | 3.46 (2.48,3.73) | 0.155 |

| T-BiL (μmol/L) | 10.2 (7.9,12) | 11.27 (8.4,11.5) | 0.266 | 10.8 (6.3,14.3) | 11.27 (8.7,11.27) | 0.557 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.96 (4.06,5.64) | 3.94 (3.22,4.61) | <0.001 | 5.11 (4.06,5.87) | 3.84 (2.94,4.59) | <0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.51 (1.07,2.04) | 1.54 (0.99,2.12) | 0.771 | 1.78 (1.15,2.23) | 1.37 (0.91,2.0) | 0.238 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 0.98 (0.71,1.21) | 0.93 (0.7,1.21) | 0.901 | 0.98 (0.64,1.22) | 0.915 (0.67,1.19) | 0.499 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.02 (1.41,2.63) | 2.17 (1.6,2.76) | 0.266 | 2.01 (1.62,2.55) | 2.05 (1.44,2.53) | 0.847 |

| Concomitant medications - antibiotics | ||||||

| Carbapenems | 29 (46.8) | 175 (36.8) | 0.130 | 16 (48.5) | 80 (40.4) | 0.383 |

| Beta-lactam/enzyme inhibitor combinations | 19 (30.6) | 190 (40) | 0.308 | 11 (33.3) | 83 (41.9) | 0.353 |

| Fluoroquinolones | 21 (33.9) | 137 (28.8) | 0.414 | 11 (33.3) | 71 (35.9) | 0.779 |

| Polypeptides | 15 (24.2) | 109 (22.9) | 0.827 | 7 (21.2) | 37 (18.7) | 0.732 |

| Cephalosporins | 6 (9.7) | 35 (7.4) | 0.697 | 3 (9.1) | 17 (8.6) | 0.924 |

| Aminoglycosides | 3 (4.8) | 14 (2.9) | 0.452 | 0 (0) | 6 (3.0) | 0.171 |

| Macrolides | 1 (1.6) | 6 (1.3) | 0.825 | 0 (0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.334 |

| Tetracyclines | 7 (11.3) | 48 (10.1) | 0.772 | 3 (9.1) | 16 (8.1) | 0.847 |

| Linezolid | 14 (22.6) | 81 (17.1) | 0.283 | 6 (18.2) | 36 (18.2) | 1.0 |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 9 (14.5) | 30 (6.3) | 0.034 | 3 (9.1) | 12 (6.1) | 0.532 |

| Other medications | ||||||

| Glucocorticoids | 24 (38.7) | 127 (26.7) | 0.049 | 11 (33.3) | 49 (24.7) | 0.298 |

| Statins | 6 (9.7) | 45 (9.5) | 0.959 | 5 (15.2) | 19 (9.6) | 0.356 |

| Fenofibrate | 2 (3.2) | 13 (2.7) | 0.83 | 0 (0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.334 |

| Caspofungin | 10 (16.1) | 36 (7.6) | 0.024 | 4 (12.1) | 15 (7.6) | 0.379 |

| Cytarabine | 4 (6.5) | 33 (6.9) | 0.884 | 4 (12.1) | 11 (5.6) | 0.193 |

| Calcium channel blockers | 8 (12.9) | 45 (9.5) | 0.394 | 5 (15.2) | 23 (11.6) | 0.575 |

| β-adrenergic antagonist | 4 (6.5) | 78 (16.4) | 0.04 | 6 (18.2) | 32 (16.2) | 0.772 |

| Ezetimibe | 2 (3.2) | 3 (0.6) | 0.045 | 0 (0) | 2 (1.0) | 0.431 |

| Metformin | 2 (3.2) | 17 (3.6) | 0.886 | 1 (3.0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.569 |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 3 (4.8) | 10 (2.1) | 0.236 | 0 (0) | 6 (3.0) | 0.171 |

| Idarubicin | 1 (1.6) | 13 (2.7) | 0.578 | 0 (0) | 7 (3.5) | 0.139 |

| Vincristine | 1 (1.6) | 3 (0.6) | 0.454 | 0 (0) | 3 (1.5) | 0.334 |

| Rabeprazole | 4 (6.5) | 11 (2.3) | 0.063 | 2 (6.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0.153 |

| Omeprazole | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.088 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Ilaprazole | 2 (3.2) | 6 (1.3) | 0.287 | 2 (6.1) | 3 (1.5) | 0.153 |

| Pantoprazole | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | 0.483 | 1 (3.0) | 0 (0) | 0.048 |

| Bromhexine | 4 (6.5) | 12 (2.5) | 0.087 | 1 (3.0) | 7 (3.5) | 0.881 |

| Salbutamol | 1 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) | 0.088 | 1 (3.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.229 |

| Montelukast sodium | 2 (3.2) | 4 (0.8) | 0.093 | 3 (9.1) | 2 (1.0) | 0.016 |

| Terbutaline | 8 (12.9) | 24 (5.1) | 0.028 | 5 (15.2) | 8 (4.0) | 0.026 |

Univariate Logistic Regression: Voriconazole and Liver Injury in training and test Sets.

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; WBC, white blood cell count; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; PCT, procalcitonin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALB, albumin; T-BiL, total bilirubin; D-BiL, direct bilirubin; γ-GGT, Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL, High-Density Lipoprotein; LDL, Low-Density Lipoprotein. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test, Fisher’s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank-sum test to estimate P-values, while continuous variables were evaluated via the Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate.

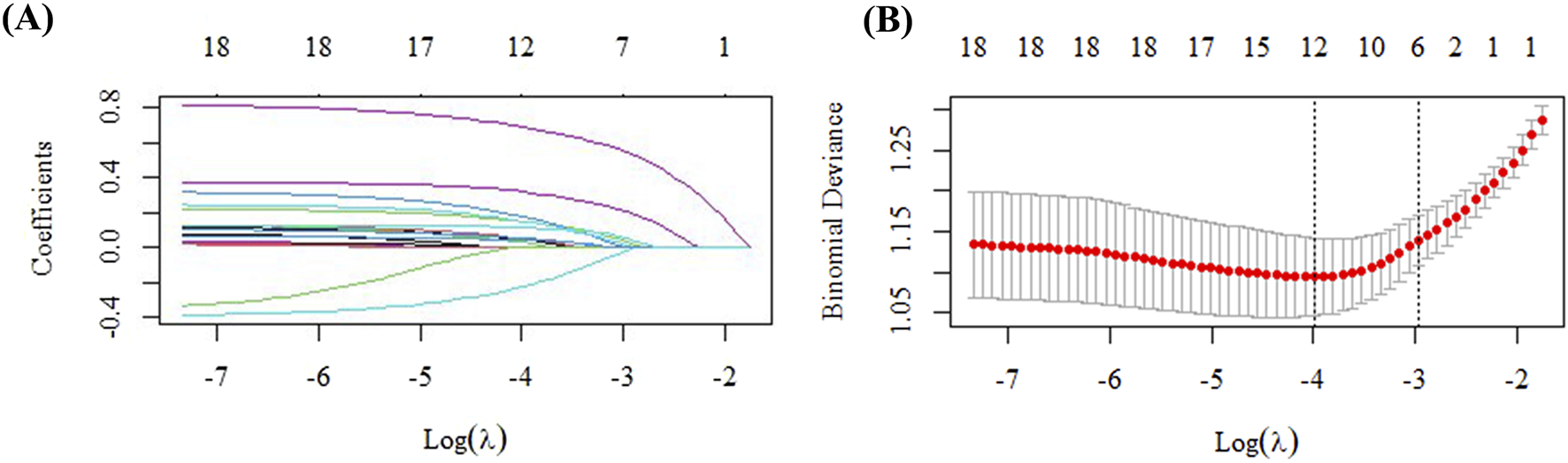

FIGURE 2

Variable selection via LASSO regression in the training cohort. (A) Identification of the optimal penalty parameter (λ) through 10-fold cross-validation. (B) Profile of the LASSO coefficients for all clinical features across different λ values.

In the training set (n = 537), patients were stratified into two groups: DILI (n = 62) and Non-DILI (n = 475). Analysis of the training set indicated that the occurrence of voriconazole-induced DILI was marginally associated with septic shock (P = 0.071). Significant associations were found with the concomitant use of sulfamethoxazole (P = 0.034), glucocorticoids (P = 0.049), caspofungin (P = 0.024), ezetimibe (P = 0.045), and terbutaline (P = 0.028). Additionally, borderline trends were noted for rabeprazole (P = 0.063), omeprazole (P = 0.088), bromhexine (P = 0.087), salbutamol (P = 0.088), and montelukast (P = 0.093). Laboratory parameters associated with DILI risk included an elevated white blood cell count (P = 0.089), procalcitonin (PCT) (P = 0.048), and total cholesterol (TC) (P < 0.05). These key indices were subsequently entered into a LASSO regression model, and variables with non-zero coefficients were retained. At λ.1se = 0.0367, the selected variables included sulfamethoxazole, caspofungin, glucocorticoids, β-blockers, bromhexine, montelukast sodium, terbutaline, ezetimibe, PCT, white blood cell count, and total cholesterol, which were then incorporated into a logistic regression to establish a new prediction model (Supplementary Table S2).

The final model identified the concomitant use of glucocorticoids, ezetimibe, caspofungin, and elevated TC levels as independent risk factors for voriconazole-induced DILI. Detailed regression coefficients, odds ratios, and corresponding P-values are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2

| Risk factor | B | SE | Wald | Exp(B) | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucocorticoids | 0.62 | 0.31 | 4.57 | 1.86 | 1.03–3.38 | 0.041 |

| Ezetimibe | 2.01 | 0.57 | 3.93 | 7.45 | 1.02–54.3 | 0.047 |

| Caspofungin | 0.91 | 0.42 | 4.61 | 2.49 | 1.08–5.71 | 0.032 |

| TC | 0.64 | 0.12 | 29.84 | 1.89 | 1.51–2.38 | <0.01 |

Multivariate analysis of the risk factors for voriconazole-induced liver injury.

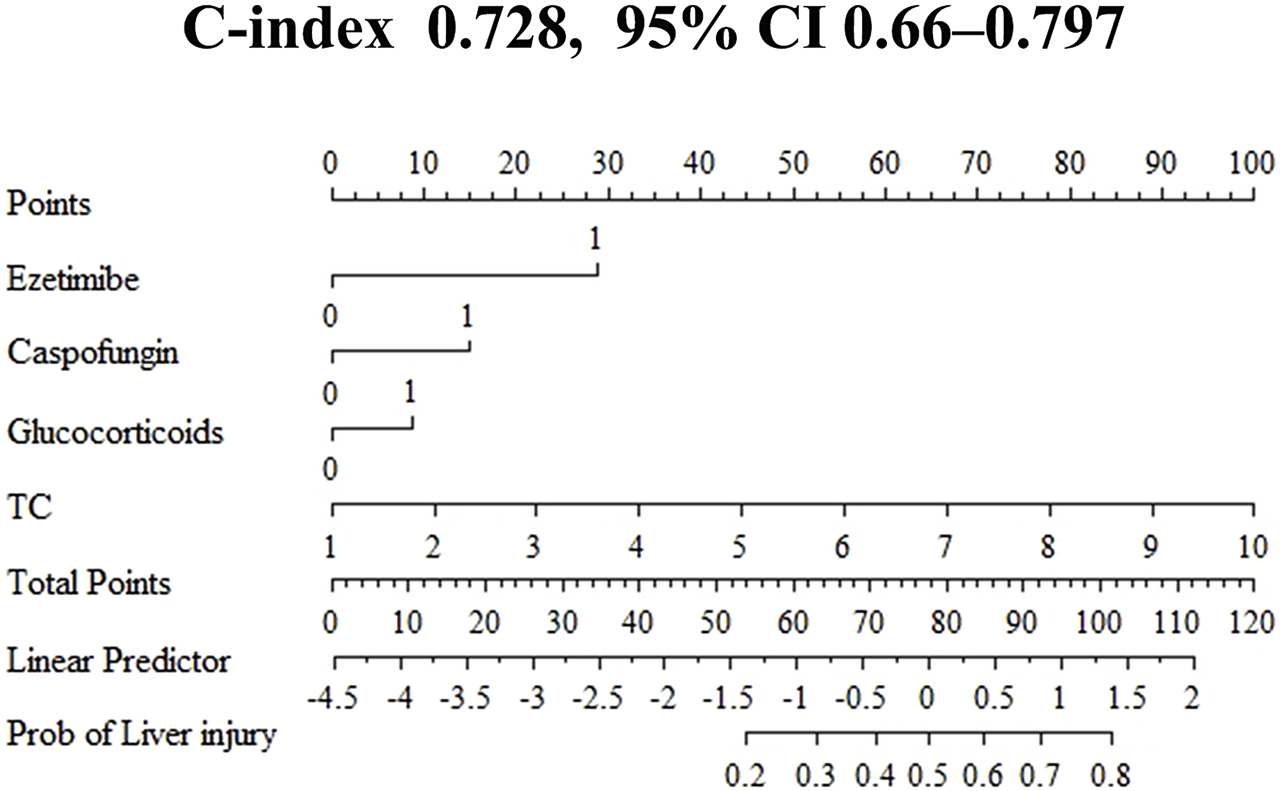

3.4 Prediction model development

Based on the high risk factors identified through logistic regression, a nomogram for predicting voriconazole-induced DILI was constructed using R 4.4.2 (Figure 3). Each risk factor-ezetimibe use, glucocorticoid use, caspofungin use, and TC levels—was assigned a score ranging from 0 to 100 points, proportional to its contribution to the outcome. Individual scores were calculated based on the value of each predictor, and the total score was converted into a probability of DILI occurrence through a predefined functional relationship. Higher total scores correlated with an increased risk of DILI.

FIGURE 3

Nomogram for predicting the risk of voriconazole-induced liver injury. All binary clinical variables are coded as 0 or 1, where 0 represents “No” (or absence) and 1 represents “Yes” (or presence). Specifically for the variables “ezetimibe,” “caspofungin,” and “glucocorticoids,” a value of 0 indicates “not used” and 1 indicates “used.” TC, total cholesterol (mmol/L). The “Points” scale assigns a score for each variable level; the total points correspond to the value on the “Linear Predictor” axis, which is then converted to the estimated risk of liver injury (“Risk” axis).

3.5 Prediction model evaluation

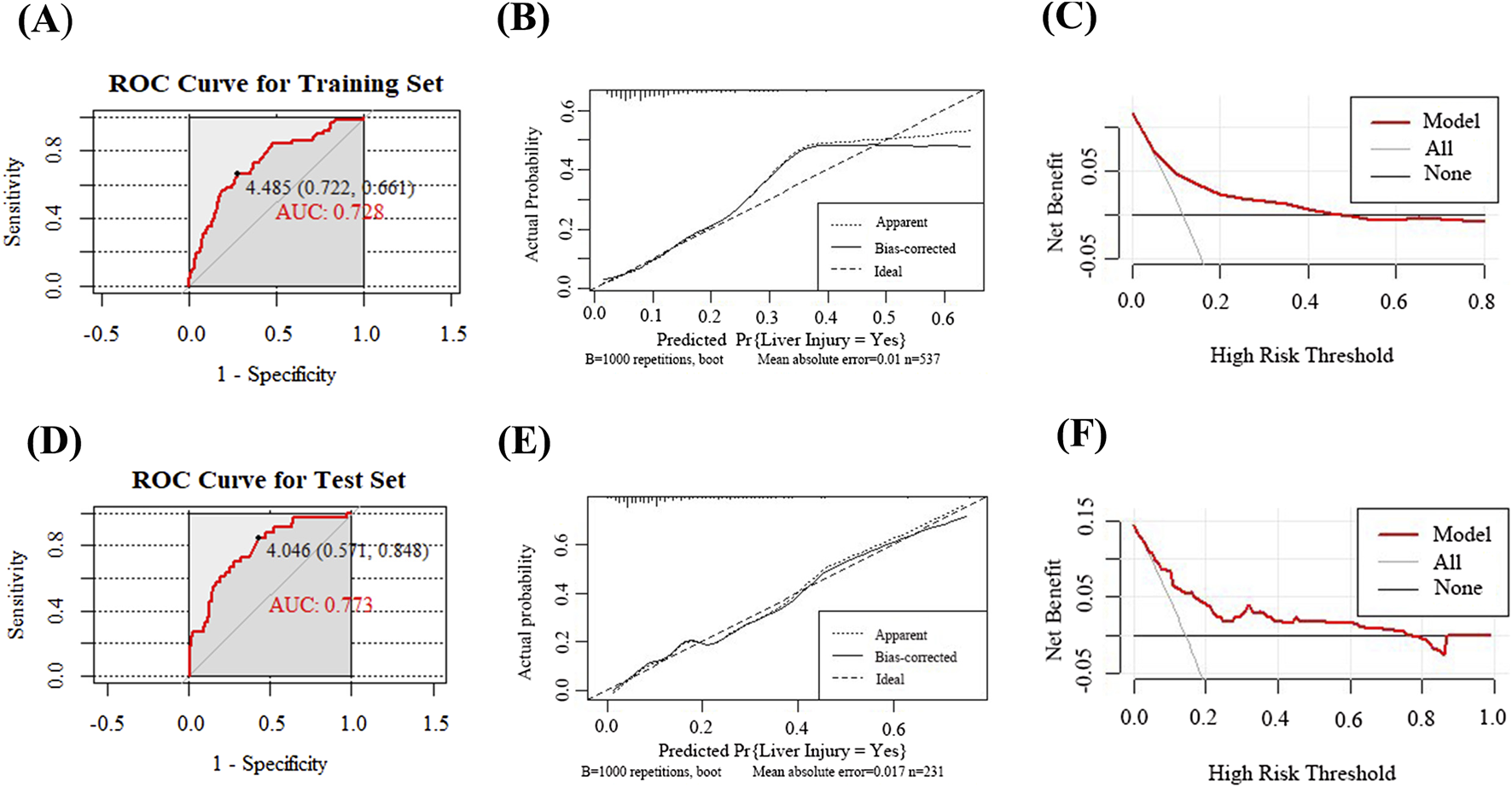

The ROC curve for the training set (Figure 4A) demonstrated an AUC of 0.728 (95% CI: 0.660–0.797), with a sensitivity of 0.661, specificity of 0.722, and an optimal cut off value for TC of 4.485 mmol/L to stratify the risk of DILI.

FIGURE 4

Evaluation and validation of the voriconazole-induced liver injury prediction model. (A) ROC curve of the model in the training set; (B) Calibration curve in the training set; (C) DCA in the training set; (D) ROC curve in the test set; (E) Calibration curve in the test set; (F) DCA in the test set.

The calibration of the nomogram was evaluated to assess the accuracy of the predicted probabilities for clinical outcomes. The calibration curve illustrated the concordance between the predicted and observed event rates. Following internal validation with 1,000 bootstrap resamples, the calibration curve of the training set demonstrated close alignment with the ideal line (45° reference), indicating good calibration performance with minimal deviation between the predicted and observed results (Figure 4B).

The model’s clinical value was assessed via DCA, as illustrated in Figure 4C. The black line, representing the “None” strategy, indicates the net benefit when no patients are diagnosed with DILI, while the light gray line, corresponding to the “All” strategy, reflects the net benefit assuming all patients are diagnosed with DILI. Within the threshold probability range of 20%–50% (0.2–0.5), the nomogram, depicted by the red curve, demonstrated a higher net benefit compared to both the “All” and “None” strategies. This finding suggests that the nomogram is optimal for guiding clinical decisions in patients with moderate-risk thresholds. At lower threshold probabilities, the model may also assist in identifying individuals who require intervention, thereby enhancing the overall net clinical benefit.

3.6 Prediction model validation

Following the successful development of the prediction model, the nomogram underwent internal validation using the test set. ROC curve analysis (Figure 4D) revealed an AUC of 0.773 (95% CI: 0.689–0.857), with a sensitivity of 0.848 and specificity of 0.571, indicating a robust discriminative ability. The calibration curve for the test set displayed close alignment with the ideal line, reflecting minimal deviation between predicted and observed outcomes, thereby confirming good calibration performance (Figure 4E). DCA further demonstrated that the model provided substantial net clinical benefit at low-risk thresholds; however, its utility diminished progressively with increasing threshold probabilities, suggesting limited clinical applicability in high-risk scenarios (Figure 4F).

4 Discussion

Voriconazole, this triazole-class antifungal is indicated for systemic IFD (Boutin et al., 2024; Allegra et al., 2020). However, the increasing clinical use of voriconazole has been associated with a rise in reported ADRs, including DILI, neurotoxicity, and visual disturbances. Idiosyncratic liver injury is one of the most common and severe complications, serving as a leading cause for the discontinuation of drug development in clinical trials and restrictions on post-marketing use (Yang et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2016). Notably, hepatotoxicity accounted for 32% of drug withdrawals between 1975 and 2007 (Stevens and Baker, 2009), highlighting its significant impact on drug safety and regulatory decision-making (Andrade et al., 2019). This retrospective study analyzed the risk factors for ADRs in patients receiving voriconazole treatment or prophylaxis. The overall incidence of ADRs was 27.7%, with DILI occurring in 12.4% of cases. Importantly, the observed DILI rate in this Chinese cohort exceeds the 1%–10% incidence of hepatic dysfunction reported in Western populations (Den Hollander et al., 2006; Shehab et al., 2007). This discrepancy may be attributed to genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C19, a key enzyme involved in voriconazole metabolism. Asian populations exhibit a higher prevalence of CYP2C19 poor metabolizers, resulting in a prolonged voriconazole half-life, delayed attainment of steady-state concentrations, and altered plasma levels (Shimizu et al., 2003; Chen et al., 2018). The concomitant use of CYP inducers (e.g., rifampicin, phenytoin) reduces voriconazole plasma concentrations, whereas coadministration with CYP inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole) or competitive substrates (e.g., warfarin) may elevate drug exposure, thereby increasing the risk of hepatotoxicity (Schulz et al., 2019).

In hospitalized patients, ADRs include hepatic dysfunction, gastrointestinal disturbances, neurotoxicity, delirium, and visual impairments, which typically emerge within 2–8 days of therapy initiation. Early hepatic injury is characterized by elevated γ-GGT levels, followed by subsequent increases in transaminase levels (ALT/AST). The increase in γ-GGT may serve as an early warning signal for hepatotoxicity, while transaminase elevation reflects progressive hepatocellular damage.

DILI is typically attributed to three primary mechanisms: mitochondrial dysfunction, disruption of bile acid homeostasis and oxidative stress (Watkins, 2019; Wu et al., 2020). This study identified TC and the concomitant use of ezetimibe, caspofungin, and glucocorticoids as independent risk factors for voriconazole-induced DILI. Prior research indicates that voriconazole therapy increases serum triglycerides and TC to 4.55-fold and 3.31-fold above baseline levels, respectively, with dyslipidemia positively correlating with voriconazole plasma concentrations (Wu et al., 2021). TC, a biomarker of lipid metabolism, may reflect hepatic lipid accumulation, potentially impairing the metabolic capacity of voriconazole and increasing susceptibility to DILI. Excessive cholesterol reduces membrane fluidity, disrupts microdomains, and alters protein function, culminating in cellular dysfunction and death (Song et al., 2021). Elevated TC levels may also exacerbate hepatotoxicity through chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, both of which are known contributors to drug-induced liver injury. Excessive cholesterol induces hepatocyte damage primarily via mitochondrial dysfunction and Kupffer cell foaming. In mitochondria, it increases membrane rigidity, disrupts protein function, and depletes glutathione, promoting reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Marí et al., 2020). Concurrently, cholesterol crystal formation triggers hepatocyte necrosis and inflammasome activation in Kupffer cells, driving inflammation and liver injury (Ioannou et al., 2017).

This study identifies ezetimibe as a significant risk factor for voriconazole-induced liver injury. As an intestinal cholesterol absorption inhibitor, ezetimibe may alter bile composition or flow and inhibit drug transporters (e.g., P-glycoprotein or Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptide), potentially elevating voriconazole plasma concentrations and exacerbating hepatotoxicity (Couture and Lamarche, 2013). Although ezetimibe is primarily metabolized via glucuronidation, its partial metabolism still depends on CYP3A4. Concurrent use of voriconazole, a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor, may lead to increased plasma concentrations of ezetimibe, prolong its hepatic exposure, and elevate the metabolic burden on hepatocytes, thereby potentially inducing or exacerbating liver injury (LiverTox, 2012). Ezetimibe has been reported to cause severe cholestatic hepatitis, which resolved after drug discontinuation. Notably, the metabolite of ezetimibe, ezetimibe glucuronide, is a substrate of multidrug resistance-associated protein 2, the primary canalicular transporter responsible for biliary excretion of conjugated bilirubin from hepatocytes. Ezetimibe glucuronide competes with bilirubin for multidrug resistance-associated protein 2-mediated transport, thereby impairing bilirubin excretion and leading to isolated hyperbilirubinemia (Ritchie et al., 2008).

Prior studies have suggested that a dosage of 150 mg/day of caspofungin is associated with a lower risk of hepatic dysfunction (12%), making it a preferred option for treating invasive candidiasis (Domingos et al., 2022). However, the high incidence of hepatotoxicity observed in our cohort may indicate synergistic toxicity between caspofungin and voriconazole, necessitating further mechanistic studies to validate this hypothesis.

This retrospective study included 387 patients (50.4%) from the hematology department, where voriconazole was primarily administered for the prophylaxis of IFD in high-risk patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Glucocorticoids (GCs), commonly utilized as adjunctive therapy for hematologic malignancies, may correlate with an increased risk of DILI. Previous studies indicate that GCs, particularly dexamethasone, significantly reduce voriconazole plasma concentrations, with dexamethasone exhibiting the most pronounced effect in lowering voriconazole levels and increasing the incidence of subtherapeutic concentrations (Imataki et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2021). As potent CYP3A4 inducers, GCs may accelerate voriconazole metabolism, resulting in diminished plasma concentrations. Clinicians may need to escalate voriconazole doses to maintain therapeutic efficacy; however, inter-individual variability (e.g., CYP2C19 polymorphisms) could lead to drug accumulation and heightened hepatotoxicity in certain patients. Enhanced voriconazole metabolism via alternative pathways (e.g., CYP2C9) may produce hepatotoxic metabolites, such as voriconazole N-oxide, which can directly harm hepatocytes.

Prolonged or high-dose GC therapy may exacerbate liver injury through mechanisms such as steatosis, which occurs via lipolysis and the deposition of free fatty acids (Marino et al., 2016) or through mitochondrial dysfunction (Hernández-Alvarez et al., 2013). Although GCs exhibit weak intrinsic hepatotoxicity, their combination with Voriconazole may produce synergistic effects. Voriconazole induces ROS-mediated oxidative stress, while GCs may suppress antioxidant defenses, such as superoxide dismutase, thereby collectively amplifying hepatocellular damage (Luan et al., 2019).

This study reveals a significant inverse association between β-blocker use and the risk of voriconazole-induced hepatotoxicity (OR = 0.295, P = 0.032). Preclinical studies have demonstrated that carvedilol (CVL), a non-selective β-blocker, exerts hepatoprotective effects in toxin-induced liver injury models, independent of its β-adrenergic blocking properties (Wong et al., 2018). Specifically, CVL attenuates hepatic injury and ibrogenesis in a murine model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by suppressing ROS-dependent NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome activation (Wong et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2022). Additionally, CVL downregulates inflammatory cytokine signaling in Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells, thereby mitigating oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in ethanol-induced liver injury models (Araújo et al., 2016). Furthermore, β-blockers have been shown to improve hepatic sinusoidal endothelial dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis by reducing portal pressure, alleviating sinusoidal congestion, and enhancing endothelial hypoxia resistance (Wu et al., 2019).Although β-blockers have demonstrated efficacy in reducing oxidative stress markers in models of alcoholic liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, their protective role against DILI remains insufficiently explored. Further studies are necessary to validate the effects of β-blockers on oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, and sinusoidal hemodynamics in voriconazole-induced hepatotoxicity using preclinical animal models. Additionally, analysis of clinical cohort data is essential to confirm the observed inverse association between β-blocker use and voriconazole-related liver injury.

Thus, polypharmacy, especially with medications that are metabolized by the liver, represents an independent risk factor for DILI. When implementing combination therapy regimens, it is imperative to thoroughly evaluate the potential hepatotoxicity of each agent, as well as the possible drug-drug interactions and pharmacokinetic dynamics, to ensure both therapeutic safety and efficacy.

This study developed a nomogram prediction model for voriconazole-induced DILI by identifying key predictors through binary logistic regression analysis. The model demonstrated predictive accuracy, with AUC values of 0.728 and 0.773 for the training and test sets. Calibration curves revealed minimal deviation between predicted and observed results, with mean absolute errors of 0.01 and 0.018, respectively. DCA further confirmed the clinical utility of the model, showing substantial net benefits across a wide range of threshold probabilities. This study was the first to identify elevated TC levels as a novel predictor of voriconazole-induced hepatotoxicity. By integrating patient-specific characteristics, the nomogram provides actionable insights for clinicians to stratify DILI risk and optimize therapeutic decisions, such as initiating targeted monitoring or adjusting treatment regimens. However, this study has several limitations. First, trough plasma concentrations of voriconazole, which have been strongly linked to hepatotoxicity in prior studies, were excluded as a predictor due to insufficient therapeutic drug monitoring data at our institution. Incorporating trough plasma concentrations in future research could enhance the model’s predictive accuracy. Additionally, ALP, a key biomarker for cholestatic liver injury, was not included in the analysis because over 50% of the retrospective records lacked ALP measurements. Furthermore, this single-center, retrospective study included a limited number of ezetimibe-exposed cases (n = 7, <1%), representing a rare exposure. Although ezetimibe was associated with a significantly increased risk (adjusted OR = 7.45, P = 0.047) in the multivariate model, such rare events are susceptible to selection bias. Future multicenter studies with expanded sample sizes are warranted to validate the association between ezetimibe and voriconazole-associated DILI and to further explore its dose-response relationship. Finally, the impact of genetic polymorphisms in CYP2C19 and CYP3A4, critical enzymes governing voriconazole metabolism, could not be assessed due to the unavailability of genotypic data. These polymorphisms may contribute to inter-individual variability in hepatotoxicity risk by altering drug clearance and metabolite profiles.

5 Conclusion

In summary, the concomitant use of ezetimibe, glucocorticoids, or caspofungin is significantly associated with an increased risk of voriconazole-induced DILI. Based on these identified risk factors, we developed a nomogram prediction model for voriconazole-related DILI. This model facilitates the early identification of high-risk patients, enabling personalized treatment strategies to mitigate hepatotoxicity and reduce the incidence of voriconazole-related adverse effects.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by scientific research ethics committee of the first affiliated hospital of Jinan University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because this study did not involve patient blood or tissue samples.

Author contributions

DF: Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Writing – original draft. YM: Writing – review and editing, Funding acquisition. XL: Data curation, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. ST: Visualization, Writing – original draft. SX: Supervision, Writing – review and editing. JW: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Project administration, Resources. SL: Funding acquisition, Resources, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. Funding by the Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau, Guangzhou Science and Technology Plan Project – City-University Joint Funding Program (No. SL2023A03J01057).the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (11623309). Science and Technology Projects in Guangzhou (2024A04J404).

Acknowledgments

We are profoundly grateful to the reviewers for their insightful suggestions. Their rigorous scholarship and invaluable recommendations were instrumental in enhancing the theoretical framework, methodological robustness, and logical coherence of this work. We also extend sincere appreciation to all cited authors whose pioneering research established the foundational knowledge for our study. Finally, we acknowledge with gratitude the institutional support provided by the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1688711/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Aithal G. P. Watkins P. B. Andrade R. J. Larrey D. Molokhia M. Takikawa H. et al (2011). Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.89 (6), 806–815. 10.1038/clpt.2011.58

2

Allegra S. De Francia S. De Nicolò A. Cusato J. Avataneo V. Manca A. et al (2020). Effect of gender and age on voriconazole trough concentrations in Italian adult patients. Eur. J. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet.45 (3), 405–412. 10.1007/s13318-019-00603-6

3

Andrade R. J. Chalasani N. BjöRNSSON E. S. Suzuki A. Kullak-Ublick G. A. Watkins P. B. et al (2019). Drug-induced liver injury. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim.5 (1), 58. 10.1038/s41572-019-0105-0

4

Araújo R. F. Garcia V. B. LeitãO R. F. Brito G. A. d. C. Miguel E. d. C. Guedes P. M. M. et al (2016). Carvedilol improves inflammatory response, oxidative stress and fibrosis in the alcohol-induced liver injury in rats by regulating kuppfer cells and hepatic stellate cells. PLoS One11 (2), e0148868. 10.1371/journal.pone.0148868

5

Boutin C. A. Durocher F. Beauchemin S. Ziegler D. Abou Chakra C. N. Dufresne S. F. (2024). Breakthrough invasive fungal infections in patients with high-risk hematological disorders receiving voriconazole and posaconazole prophylaxis: a systematic review. Clin. Infect. Dis.79 (1), 151–160. 10.1093/cid/ciae203

6

Chen K. Zhang X. Ke X. Du G. Yang K. Zhai S. (2018). Individualized medication of voriconazole: a practice guideline of the division of therapeutic drug monitoring, Chinese pharmacological society. Ther. Drug Monit.40 (6), 663–674. 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000561

7

Cheng L. Zhao Y. Liang Z. You X. Jia C. Liu X. et al (2023). Prediction of plasma trough concentration of voriconazole in adult patients using machine learning. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.188, 106506. 10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106506

8

Colombo M. (2020). EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of occupational liver diseases. Liver Int.40 (Suppl. 1), 136–141. 10.1111/liv.14349

9

Couture P. Lamarche B. (2013). Ezetimibe and bile acid sequestrants: impact on lipoprotein metabolism and beyond. Curr. Opin. Lipidol.24 (3), 227–232. 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283613a55

10

Danan G. Teschke R. (2015). RUCAM in drug and herb induced liver injury: the update. Int. J. Mol. Sci.17 (1), 14. 10.3390/ijms17010014

11

Den Hollander J. G. Van Arkel C. Rijnders B. J. Lugtenburg P. J. de Marie S. Levin M. D. (2006). Incidence of voriconazole hepatotoxicity during intravenous and oral treatment for invasive fungal infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.57 (6), 1248–1250. 10.1093/jac/dkl108

12

Domingos E. L. Vilhena R. O. Santos J. Fachi M. M. Böger B. Adam L. M. et al (2022). Comparative efficacy and safety of systemic antifungal agents for candidemia: a systematic review with network meta-analysis and multicriteria acceptability analyses. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents60 (2), 106614. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2022.106614

13

Du Q. Teng M. Yang L. Meng C. Qiu Y. Wang C. et al (2023). Metabolic characteristics of voriconazole - induced liver injury in rats. Chem. Biol. Interact.383, 110693. 10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110693

14

Freites-Martinez A. Santana N. Arias-Santiago S. Viera A. (2021). Using the common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE - Version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of adverse events of anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr. Engl. Ed.112 (1), 90–92. 10.1016/j.ad.2019.05.009

15

Hanai Y. Ueda T. Hamada Y. Oda K. Takahashi Y. Nakajima K. et al (2023). Optimal timing for therapeutic drug monitoring of voriconazole to prevent adverse effects in Japanese patients. Mycoses66 (12), 1035–1044. 10.1111/myc.13639

16

Hernández-Alvarez M. I. Paz J. C. SebastiáN D. Muñoz J. P. Liesa M. Segalés J. et al (2013). Glucocorticoid modulation of mitochondrial function in hepatoma cells requires the mitochondrial fission protein Drp1. Antioxid. Redox Signal19 (4), 366–378. 10.1089/ars.2011.4269

17

Imataki O. Yamaguchi K. Uemura M. Fukuoka N. (2018). Voriconazole concentration is inversely correlated with corticosteroid usage in immunocompromised patients. Transpl. Infect. Dis.20 (4), e12886. 10.1111/tid.12886

18

Ioannou G. N. Subramanian S. Chait A. Haigh W. G. Yeh M. M. Farrell G. C. et al (2017). Cholesterol crystallization within hepatocyte lipid droplets and its role in murine NASH. J. Lipid Res.58 (6), 1067–1079. 10.1194/jlr.M072454

19

Jia S. J. Gao K. Q. Huang P. H. Guo R. Zuo X. C. Xia Q. et al (2021). Interactive effects of glucocorticoids and cytochrome P450 polymorphisms on the plasma trough concentrations of voriconazole. Front. Pharmacol.12, 666296. 10.3389/fphar.2021.666296

20

Jin H. Wang T. Falcione B. A. Olsen K. M. Chen K. Tang H. et al (2016). Trough concentration of voriconazole and its relationship with efficacy and safety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.71 (7), 1772–1785. 10.1093/jac/dkw045

21

LiverTox (2012). Clinical and research information on drug-induced liver injury.

22

Luan G. Li G. Ma X. Jin Y. Hu N. Li J. et al (2019). Dexamethasone-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and insulin resistance-study in 3T3-L1 adipocytes and mitochondria isolated from mouse liver. Molecules24 (10), 1982. 10.3390/molecules24101982

23

Ma J. Wang Y. Ma S. Li J. (2023). The investigation and prediction of voriconazole-associated hepatotoxicity under therapeutic drug monitoring. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc.2023, 1–4. 10.1109/EMBC40787.2023.10340343

24

Marí M. De Gregorio E. De DIOS C. Roca-Agujetas V. Cucarull B. Tutusaus A. et al (2020). Mitochondrial glutathione: recent insights and role in disease. Antioxidants (Basel)9 (10), 909. 10.3390/antiox9100909

25

Marino J. S. Stechschulte L. A. Stec D. E. Nestor-Kalinoski A. Coleman S. Hinds T. D. Jr (2016). Glucocorticoid receptor β induces hepatic steatosis by augmenting inflammation and inhibition of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α. J. Biol. Chem.291 (50), 25776–25788. 10.1074/jbc.M116.752311

26

Meunier L. Larrey D. (2023). Hepatotoxicity of drugs used in multiple sclerosis, diagnostic challenge, and the role of HLA genotype susceptibility. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24 (1), 852. 10.3390/ijms24010852

27

Patterson T. F. Thompson G. R. Denning D. W. Fishman J. A. Hadley S. Herbrecht R. et al (2016). Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aspergillosis: 2016 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis.63 (4), e1–e60. 10.1093/cid/ciw326

28

Perreault S. Mcmanus D. Anderson A. Lin T. Ruggero M. Topal J. E. (2019). Evaluating a voriconazole dose modification guideline to optimize dosing in patients with hematologic malignancies. J. Oncol. Pharm. Pract.25 (6), 1305–1311. 10.1177/1078155218786028

29

Ranganathan P. Pramesh C. S. Aggarwal R. (2017). Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: logistic regression. Perspect. Clin. Res.8 (3), 148–151. 10.4103/picr.PICR_87_17

30

Ritchie S. R. Orr D. W. Black P. N. (2008). Severe jaundice following treatment with ezetimibe. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.20 (6), 572–573. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f1752d

31

Schulz J. Kluwe F. Mikus G. Michelet R. Kloft C. (2019). Novel insights into the complex pharmacokinetics of voriconazole: a review of its metabolism. Drug Metab. Rev.51 (3), 247–265. 10.1080/03602532.2019.1632888

32

Shehab N. Depestel D. D. Mackler E. R. Collins C. D. Welch K. Erba H. P. (2007). Institutional experience with voriconazole compared with liposomal amphotericin B as empiric therapy for febrile neutropenia. Pharmacotherapy27 (7), 970–979. 10.1592/phco.27.7.970

33

Shen K. Gu Y. Wang Y. Lu Y. Ni Y. Zhong H. et al (2022). Therapeutic drug monitoring and safety evaluation of voriconazole in the treatment of pulmonary fungal diseases. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf.13, 20420986221127503. 10.1177/20420986221127503

34

Shimizu T. Ochiai H. Asell F. Yokono Y. Kikuchi Y. Nitta M. et al (2003). Bioinformatics research on inter-racial difference in drug metabolism II. Analysis on relationship between enzyme activities of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 and their relevant genotypes. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet.18 (1), 71–78. 10.2133/dmpk.18.71

35

Song Y. Liu J. Zhao K. Gao L. (2021). Cholesterol-induced toxicity: an integrated view of the role of cholesterol in multiple diseases. Cell Metab.33 (10), 1911–1925. 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.09.001

36

Stevens J. L. Baker T. K. (2009). The future of drug safety testing: expanding the view and narrowing the focus. Drug Discov. Today14 (3-4), 162–167. 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.11.009

37

Taccone F. S. Van Den Abeele A. M. Bulpa P. Misset B. Meersseman W. Cardoso T. et al (2015). Epidemiology of invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: clinical presentation, underlying conditions, and outcomes. Crit. Care19 (1), 7. 10.1186/s13054-014-0722-7

38

Tiwari V. Shandily S. Albert J. Mishra V. Dikkatwar M. Singh R. et al (2025). Insights into medication-induced liver injury: understanding and management strategies. Toxicol. Rep.14, 101976. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2025.101976

39

Wang T. Miao L. Shao H. Wei X. Yan M. Zuo X. et al (2022). Voriconazole therapeutic drug monitoring and hepatotoxicity in critically ill patients: a nationwide multi-centre retrospective study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents60 (5-6), 106692. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2022.106692

40

Watkins P. B. (2019). The DILI-Sim initiative: insights into hepatotoxicity mechanisms and biomarker interpretation. Clin. Transl. Sci.12 (2), 122–129. 10.1111/cts.12629

41

Wong W. T. Li L. H. Rao Y. K. Yang S. P. Cheng S. M. Lin W. Y. et al (2018). Repositioning of the β-Blocker carvedilol as a novel autophagy inducer that inhibits the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Immunol.9, 1920. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01920

42

Wu Y. Li Z. Xiu A. Y. Meng D. X. Wang S. N. Zhang C. Q. (2019). Carvedilol attenuates carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis and hepatic sinusoidal capillarization in mice. Drug Des. Devel Ther.13, 2667–2676. 10.2147/DDDT.S210797

43

Wu S. L. Cheng C. N. Wang C. C. Lin S. W. Kuo C. H. (2020). Metabolomics analysis of plasma reveals voriconazole-induced hepatotoxicity is associated with oxidative stress. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.403, 115157. 10.1016/j.taap.2020.115157

44

Wu J. Chen N. Yao Y. Zhou J. Zhou H. (2021). Hyperlipidemia caused by voriconazole: a case report. Infect. Drug Resist14, 483–487. 10.2147/IDR.S301198

45

Yang L. Wang C. Zhang Y. Wang Q. Qiu Y. Li S. et al (2022). Central nervous system toxicity of voriconazole: risk factors and threshold - a retrospective cohort study. Infect. Drug Resist15, 7475–7484. 10.2147/IDR.S391022

46

Yu L. Hong W. Lu S. Guan Y. Weng X. et al (2022). The NLRP3 inflammasome in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis: therapeutic targets and treatment. Front. Pharmacol.13, 780496. 10.3389/fphar.2022.780496

47

Zhou Z. X. Yin X. D. Zhang Y. Shao Q. H. Mao X. Y. Hu W. J. et al (2022). Antifungal drugs and drug-induced liver injury: a real-world study leveraging the FDA adverse event reporting system database. Front. Pharmacol.13, 891336. 10.3389/fphar.2022.891336

Summary

Keywords

voriconazole, nomogram, drug-induced liver injury, predictive model, real-world study

Citation

Feng D, Ma Y, Liu X, Tang S, Xiang S, Wang J and Li S (2026) Voriconazole-associated liver injury: clinical risk factor identification and predictive nomogram construction. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1688711. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1688711

Received

19 August 2025

Revised

21 November 2025

Accepted

01 December 2025

Published

05 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Xinling Pan, Dongyang Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, China

Reviewed by

Hao Wang, AbbVie, United States

Oscar Ardila-Suárez, Universidad CES, Colombia

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Feng, Ma, Liu, Tang, Xiang, Wang and Li.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Shasha Li, s19861020@jnu.edu.cn; Jinghao Wang, wangjinghaojnu@163.com

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.