Abstract

Ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) refers to a condition in which ischemia is followed by reperfusion, leading to an exacerbation of the initial tissue damage. Currently, there are no specific therapeutic methods for IRI. Phytochemicals from natural products have the potential to develop noble drugs for IRI. Naringenin (NGE) and naringin (NG) are natural dietary flavonoids derived from ethnobotanical plants in Southeast and South Asia. NGE and NG have a wide range of pharmacological properties, including antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects. As research on NGE and NG deepens, it has been found that they protect against IRI. We first summarize plant species containing NGE and NG from Southeast and South Asia in this article. Then, we highlight recent advances in NGE and NG for treating IRI in the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, retinal, liver, spinal cord, skeletal muscles, and testicles. We find that NGE and NG possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, anti-endoplasmic reticulum stress, anti-ferroptosis, anti-pyroptosis, and autophagy regulatory properties that protect organs from IRI. In addition, NGE and NG alleviate organ IRI through certain signaling pathways, including nuclear factor-κB, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT, cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate synthase–stimulator of interferon genes, sirtuin (SIRT) 1/SIRT 3, and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α. Furthermore, we investigate the interactions between these signaling pathways and inflammation, oxidative stress, and programmed cell death. Nevertheless, NGE and NG still face challenges related to pharmacokinetic interactions, bioavailability, and clinical safety assessments. Further studies will be needed to verify their safety and efficacy in clinical settings.

1 Introduction

Ischemia/reperfusion injury (IRI) refers to the restoration of blood flow after ischemia and is one of the leading causes of death in ischemic diseases (Tian et al., 2024). IRI is a highly destructive pathological process present in various organs, such as the myocardium, brain, liver, lungs, kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, and retina (de Groot and Rauen, 2007). In addition to tissue damage, IRI can even trigger systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (Wu et al., 2018). IRI’s pathological mechanism is highly complex, and oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis participate in the mechanism, forming an intricate network (Kalogeris et al., 2016; Turer and Hill, 2010). Different strategies have been developed for preventing and treating IRI, including physical therapies, gene therapies, drug therapies, and cell protection strategies (Li et al., 2025). At present, there is no specific drug for IRI owing to complex multifactorial damage and side effects. Consequently, novel agents with better efficacy and fewer side effects are needed to prevent IRI.

Increasingly, studies are focusing on natural products, including metabolites derived from plants (Ahmadi and Shadboorestan, 2016; Ahmadi et al., 2015). Southeast and South Asia are abundant in natural plant biodiversity, with a long history of medicinal plants (Ware et al., 2023). Naringenin (NGE) and its glycoside, naringin (NG), are natural dietary flavonoids found in citrus fruits (e.g., grapefruit and tomatoes) and ethnobotanical plants in Southeast and South Asia (Heidary Moghaddam et al., 2020; Stabrauskiene et al., 2022). Several studies have demonstrated that NGE and NG exhibit multiple biological properties, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-ulcerative, and anticancer properties (Ahmadi and Shadboorestan, 2016). Meanwhile, multiple studies have demonstrated that NGE and NG improve IRI, including the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, retina, liver, spinal cord, skeletal muscle, and testicles. Despite several reviews describing the role of NGE and NG in myocardial infarction (Kampa et al., 2023), brain ischemic (Chen et al., 2020), and acute kidney injury (Amini et al., 2022), to the best of our knowledge, the protective mechanisms of NGE and NG in multi-organ IRI have not been summarized. Integrated multi-organ studies can identify pathways that play protective roles across different organs, which may be overlooked in organ-specific research. This article reviews the latest preclinical evidence of NGE and NG on organ IRI, providing a more comprehensive and in-depth perspective on therapeutic strategies.

2 Isolation report of NGE and NG in Southeast and South Asian plants

Numerous natural products and medicinal plants are found in tropical and subtropical areas (particularly Southeast Asia and South Asia) (Prasad et al., 2016; Ware et al., 2023). Southeast Asia and South Asia have the highest levels of medicinal plant diversity due to their favorable environmental and geographical conditions (Prasad et al., 2016). There are several countries in the Southeast Asia region, including Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, Cambodia, Malaysia, Laos, Vietnam, Timor-Lest, Myanmar, the Philippines, and Brunei. As the largest country in Southeast Asia, Indonesia is known for its endemism and rich diversity of species (Sun et al., 2024). Indonesia has 56%, 22%, and 8.7% of the world’s vascular plants in terms of families, genera, and species, respectively (Sun et al., 2024). As the second largest country in Southeast Asia, Myanmar’s rich biodiversity is well known, with an estimated 11,800 species of angiosperms and gymnosperms (Kyaw et al., 2021). Southern Asia has eight countries, namely, India, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, and the Maldives (Mukherjee and Mackessy, 2021). India covers 2.4% of global land area and 8% of the world’s biodiversity (Gupta et al., 2022). More than 4,000 medicinal plant species have been recorded in the Indian Western Ghats, one of the 36 worldwide biodiversity hot spots (Gupta et al., 2022). As a country belonging to the Indian subcontinent, Bangladesh is also renowned for its herbal medicines, which feature more than 500 plant species (Rouf et al., 2021). Pakistan possesses unique biodiversity, with 1,572 genera and 5,521 species of flowering plants, of which approximately 400–600 are medicinally relevant (Bibi et al., 2015). NGE and NG have been isolated from plants in these regions, either from whole plants or specific parts such as roots and fruits. Table 1 and Table 2 summarize these plant species. The scientific names and families have been verified by Flora of China (http://www.iplant.cn/) and World Checklist of Selected Plant Families (https://wcsp.science.kew.org/).

TABLE 1

| Serial number | Plants’ scientific name | Plants’ local name | Family | Plant part | Extract | Origin/country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Salacia oblonga Wall. | Ponkoranti | Celastraceae | Leaves | Methanol/water | India | Singh et al. (2018) |

| 2 | Citrus reticulata Blanco | Santra | Rutaceae | Peel | Methanol | India | Srimathi et al. (2022) |

| 3 | Nymphaea mexicana Zucc. | Neel kamal | Nymphaeaceae | Dried shoot | Methanol | India | Din et al. (2022) |

| 4 | Ficus racemosa L. | Gular | Moraceae | Fresh stem bark | Methanol/water | India | Keshari et al. (2016) |

| 5 | Carica papaya L. | Papaya | Caricaceae | Leaves and seeds | Extraction solvent | India | Gogna et al. (2015) |

| 6 | Halodule pinifolia (Miki) Hartog | Neettu korai | Cymodoceaceae | Leaves | Chloroform/methanol | India | Danaraj et al. (2020) |

| 7 | Afzelia xylocarpa (Kurz) Craib | Makha-hua-kham | Fabaceae | Twigs | Methanol | Thailand | Pitchuanchom et al. (2022) |

| 8 | Wendlandia tinctoria (Roxb.) DC. | Kara-kholi Kadam |

Rubiaceae | Aerial portion | Methanol | Bangladesh | Farzana et al. (2022) |

| 9 | Garcinia atroviridis L. | Asam Gelugur | Clusiaceae | Dried fruits and leaves | Methanol | Indonesia | Muchtaridi et al. (2022) |

| 10 | Bouea macrophylla Griff. | Kundang | Anacardiaceae | Fresh leaves | Methanol | Vietnam | Nguyen et al. (2023) |

| 11 | Hibiscus rosa sinensis L. | Semparuthi | Malvaceae | Red flower petals | Ethanol | Vietnam | Tran Trung et al. (2020) |

| 12 | Coix lachryma-jobi L. | Yi-mi | Poaceae | Seeds | Ethanol | China | Chen et al. (2011) |

| 13 | Selaginella doederleinii Hieron. | Da-ye-cai | Selaginellaceae | Whole herbs | Ethanol/water | China | Zou et al. (2017) |

| 14 | Craibiodendron yunnanense W. W. Sm. | Jin-ye-zi | Ericaceae | Leaves | Ethanol | China | Wang Y. et al. (2023) |

| 15 | Eleocharis tuberosa Schult. | Bi-qi | Cyperaceae | Fruits | Ethanol | China | Pan et al. (2015) |

| 16 | Iris domestica L. | She-gan | Iridaceae | Rhizomes | Ethanol | China | Liu et al. (2022a) |

| 17 | Malus prunifolia (Willd.) Borkh. | Shan-zha | Rosaceae | Fresh fruits | Ethanol and ultrasounds | China | Wen et al. (2018) |

| 18 | Smilax glaucochina Warb. | Hei-guo-ba-qia | Smilacaceae | Rhizomes | Ethanol/water | China | Shu et al. (2018) |

| 19 | Viburnum utile Hemsl. | Yan-guan-jia-mi | Viburnaceae | Flowers and leaves | Ethanol | China | Long et al. (2024) |

| 20 | Clinopodium chinense (Benth.) Kuntze | Feng-lun-cai | Labiatae | Aerial parts | Ethanol/water | China | Zhong et al. (2012) |

| 21 | Xanthoceras sorbifolium Bunge | Wen-guan-guo | Sapindaceae | Husk | Ethanol | China | Li et al. (2006) |

| 22 | Euphorbia humifusa Willd. | Di-jin-cao | Euphorbiaceae | Whole herb | Methanol | China | Dai et al. (2024) |

| 23 | Angelica dahurica Hoffm. | Bai-zhi | Apiaceae | Roots | Ethanol | China | Wang M. et al. (2023) |

| 24 | Citrus aurantium L. | Zhi-qiao | Rutaceae | Raw herb | Methanol | China | Liu et al. (2018b) |

| 25 | Morus atropurpurea Roxb. | Guang-dong-sang | Moraceae | Seeds | Cyclohexane/ethyl acetate/n-butanol | China | Ya et al. (2006) |

| 26 | Citrus sinensis L. | Tian-cheng | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate buffer solution | China | Lin et al. (2021) |

| 27 | Citrus lemon L. | Ning-meng | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate buffer solution | China | Pei et al. (2022) |

| 28 | Citrus paradisi L. | You-zi | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate buffer solution | China | Pei et al. (2022) |

| 29 | Citrus reticulata L. | Bu-zhi-huo | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate buffer solution | China | Pei et al. (2022) |

| 30 | Dictamnus dasycarpus Turcz. | Bai-xian | Rutaceae | Root barks | Methanol | China | Guo et al. (2018) |

Isolation report of naringenin from Southeast and South Asian plants.

TABLE 2

| Serial number | Plants’ scientific name | Plants’ local name | Family | Plant part | Extract | Origin/country | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Holarrhena pubescens Wall. | Kuthuppaalai | Apocynaceae | Leaves | Methanol | Thailand | Tuntiwachwuttikul et al. (2007) |

| 2 | Tagetes erecta L. | Chendu malli | Asteraceae | Petals | Ethanol/acetone/ethyl acetate/hexane | Thailand | Laovachirasuwan et al. (2024) |

| 3 | Citrus grandis L. | Pambalimas | Rutaceae | Peel | Methanol/water | Thailand | Caengprasath et al. (2013) |

| 4 | Morinda citrifolia L. | Aal | Rubiaceae | Air-dried powdered fruits | Ethanol | Malaysia | Ezzat et al. (2021) |

| 5 | Labisia pumila (Blume) Fern.-Vill | Kacip fatimah | Primulaceae | Herb | Methanol | Malaysia | Balachandran et al. (2023) |

| 6 | Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb. | Biriyani Chedi, Rambha | Pandanaceae | Fresh leaves | Methanol | Malaysia | Ghasemzadeh and Jaafar (2013) |

| 7 | Murraya koenigii L. | Khadilimb, Karipatta | Rutaceae | Fresh leaves | Methanol | Malaysia | Ghasemzadeh et al. (2014) |

| 8 | Hibiscus cannabinus L. | Ambadi, Ambada | Malvaceae | Seeds | Ethanol and ultrasounds | Malaysia | Kai et al. (2015) |

| 9 | Basella alba L. | Poi, Pui | Basellaceae | Fresh leaves | Methanol | Malaysia | Baskaran et al. (2015) |

| 10 | Pyrrosia longifolia (Burm. f.) C.V. | Sulai | Polypodiaceae | Aerial parts | Methanol | Indonesia | Teruna et al. (2024) |

| 11 | Ailanthus integrifolia Lam. | Ai lanit | Simaroubaceae | Dried bark | CHCl3/methanol | Indonesia | Kosuge et al. (1994) |

| 12 | Coffea arabica L. | Kahawa, Arabic coffee | Rubiaceae | Roasting green beans | Ethanol/water | Indonesia | Hayes et al. (2023) |

| 13 | Coffea robusta L. | Coffee-gida | Rubiaceae | Roasting green beans | Ethanol/water | Indonesia | Hayes et al. (2023) |

| 14 | Tadehagi triquetrum L. | Doddotte | Fabaceae | Roots | Hydroalcoholic | India | Vedpal et al. (2020) |

| 15 | Albizia myriophylla Benth. | Koroi Hikaru | Fabaceae | Bark | Microwave-assisted | India | Mangang et al. (2020) |

| 16 | Phaleria macrocarpa (Scheff.) Boerl | Mahkota Dewa | Thymelaeaceae | Pericarp | Methanol | Indonesia | Hendra et al. (2011) |

| 17 | Achyranthes aspera L. | Valiya kadaladi | Amaranthaceae | Whole plants | Methanol | Bangladesh | Huq et al. (2024) |

| 18 | Bridelia tomentosa Blume | Khy, serai | Phyllanthaceae | Fresh leaves | Methanol | Bangladesh | Mondal et al. (2021) |

| 19 | Neurada procumbens L. | Chapri-booti | Neuradaceae | Mature plant | Methanol | Pakistan | Khurshid et al. (2022) |

| 20 | Galega officinalis L. | Citrus paradesi | Fabaceae | Fruits | Solvent evaporation | Pakistan | Mehmood et al. (2024) |

| 21 | Morus atropurpurea Roxb. | Guang-dong-sang | Moraceae | Seeds | Cyclohexane/ethyl acetate/n-butanol | China | Ya et al. (2006) |

| 22 | Citrus sinensis L. | Tian-cheng | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate-buffered solution | China | Lin et al. (2021) |

| 23 | Citrus lemon L. | Ning-meng | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate-buffered solution | China | Pei et al. (2022) |

| 24 | Citrus paradisi L. | You-zi | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate-buffered solution | China | Pei et al. (2022) |

| 25 | Citrus reticulata L. | Bu-zhi-huo | Rutaceae | Fruits | Deuterated phosphate-buffered solution | China | Pei et al. (2022) |

| 26 | Davallia trichomanoides Blume | Gu-sui-bu | Davalliaceae | Dried rhizome | Methanol | China | Dong et al. (2023) |

| 27 | Selliguea hastata (Thunb.) H. | Jin-ji-jiao | Polypodiaceae | Dried rhizome | Ethanol | China | Duan et al. (2012) |

| 28 | Euphorbia humifusa Willd. | Di-jin | Euphorbiaceae | Whole herb | Methanol | China | Dai et al. (2024) |

| 29 | Angelica dahurica Fisch. | Bai-zhi | Apiaceae | Roots | Ethanol | China | Wang M. et al. (2023) |

| 30 | Litchi chinensis Sonn. | Li-zhi | Sapindaceae | Seeds | Ethanol | China | Liu et al. (2019) |

Isolation report of Naringin from Southeast and South Asian plants.

3 Methods

This review was conducted by searching three databases (PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus) up to January 2025, using keywords such as “naringenin,” “naringin,” “ischemia reperfusion,” “reperfusion injury,” “stroke,” and “infarction.” The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) IRI models, including both in vitro and in vivo studies, regardless of organ, gender, age, species, or language; 2) the presence of a control group; and 3) at least one experimental group using NGE or NG as an intervention. The exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) conference papers, reviews, comments, case reports, posters, and editorials; 2) incomplete data; and 3) studies on other compounds and diseases. As shown in File 1, the complete electronic search strategy was implemented across the three databases.

4 Chemical properties and pharmacokinetics of NGE and NG

Structurally, NGE (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone; molecular weight: 272.256 g/mol) consists of two benzene rings (A and B) connected by a chromane ring (C ring). There are three hydroxyl groups on the ring: one at position 4′ on the B ring and two at positions 5 and 7 on the A ring (Joshi et al., 2018; Kaźmierczak et al., 2025). There is one glycosylated derivative of NGE called NG (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavanone-7-rhamnoglucoside; molecular weight: 580.5 g/mol) (Shilpa et al., 2023). Compared to NGE, NG has a rhamnoside group attached to C7 in the A ring. As a result of their hydroxyl groups (7-OH, 4′-OH, and 5-OH groups), which are responsible for free radical scavenging and metal ion chelating properties, NGE and NG are potent antioxidant agents (Panche et al., 2016; Rani et al., 2016).

As soon as NGE and NG reach the cells, they undergo phase I metabolism by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (oxidation or demethylation), followed by phase II metabolism by intestinal cells or liver cells (glucuronidation, sulfation, or methylation) (Kawaguchi et al., 2011; Yang X. et al., 2022; Yang Y. et al., 2022). Microbes in the gut further metabolize metabolites and unabsorbed flavonoids into catabolites of phenolic and aromatic rings, boosting their bioavailability (Kay et al., 2017). There are two common ways to excrete NGE and NG: through bile and urine (Joshi et al., 2018). Bile excretes metabolites into the enterohepatic circulation, prolonging their elimination half-life (Ma et al., 2006). It has been demonstrated that NGE and NG are extensively distributed in certain rat tissues, such as the gut, liver, kidneys, lungs, and trachea (Zeng et al., 2019). There is evidence that NGE and NG can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), possibly through passive diffusion or active transport (Lai et al., 2025). In addition, new evidence suggests that gender and age are associated with pharmacokinetics, which in turn affects bioactivity in vivo (Yang Y. et al., 2022). Due to poor oral absorption, first-pass metabolism, and metabolite elimination, NGE and NG only have 5%–15% oral bioavailability, which limits their clinical potential (Flores-Peña et al., 2025; Joshi et al., 2018; Lavrador et al., 2018). Various strategies have been examined to improve the bioavailability of NGE and NG, including polymeric nanoparticles, hydrogel nanocarriers, lipid nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles, and nanoemulsions (Flores-Peña et al., 2025). There is no doubt that these novel approaches have the potential to enhance the therapeutic effects of NGE and NG. However, their advantages and limitations must be carefully evaluated prior to clinical application.

5 Comparison of NGE and NG

Apart from their chemical structures, NGE and NG are different in many aspects. In some studies, NGE and NG pharmacokinetics have been compared. A mean concentration–time profile in plasma was calculated after oral administration of NGE and NG to rabbits, and NG and its conjugates reached maximal concentrations after nearly 90 min, whereas NGE peaked after 10 min (Hsiu et al., 2002). A study on RAW264.7 cells showed that NGE had a weaker anti-inflammatory effect than NG in response to lipopolysaccharide-stimulated inflammation. NGE reduced inflammation by inhibiting nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and p38 phosphorylation, and NG reduced inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) (Cho and Shaw, 2024). Additionally, researchers have found that NGE scavenges hydroxyl and superoxide radicals more effectively than NG (Cavia-Saiz et al., 2010). As a result of its sugar group partially blocking access to active hydroxyl groups, NG has lower effectiveness at neutralizing free radicals (Li P. et al., 2020). Currently, only limited research compares NGE and NG effects. Hence, the varied bioactivities between NGE and NG necessitate further research.

6 Pharmacokinetic interactions and clinical safety considerations

It has been demonstrated that NGE and NG are the primary culprits in grapefruit-related food–drug interactions (Memariani et al., 2021). Cytochrome P450 enzymes participate in drug metabolism and detoxify carcinogens (Burkina et al., 2016). Research shows that NGE and NG inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes, which can increase drug blood concentrations when co-administered with other drugs (Fuhr and Kummert, 1995). Further research has found that both NGE and NG inhibit the cytochrome P450 enzymes 1A2 and 3A4, which belong to the subfamily of cytochrome P450 enzymes (Burkina et al., 2016; Fuhr et al., 1993). Carboxylesterase 1 is a major esterase present in the liver, and it hydrolyzes a wide variety of therapeutic agents and toxins. In one study, NGE showed the highest inhibition potential for carboxylesterase 1 (Qian and Markowitz, 2020). In addition, NGE inhibited P-glycoprotein activity, another efflux transporter (Romiti et al., 2004). In IRI patients, some drugs (including antidepressants, anti-infectives, calcium antagonists, and statins) can interact with grapefruit juice (Kane and Lipsky, 2000). Due to these food–drug interactions, NGE and NG should be used cautiously when co-administered with certain drugs.

Currently, insufficient clinical studies have been conducted because NGE and NG are poorly soluble in water and have low bioavailability. One study found that among healthy adults, ingestion of 150–900 mg of NGE was safe (Rebello et al., 2020). Commercial grapefruit juices contain NG concentrations ranging from 50 to 1,200 mg/L (Ho et al., 2000), and some dietary supplements recommend doses of 200–1,000 mg/day of NG (Jung et al., 2003). For a more comprehensive understanding of safety and efficacy in humans, further clinical studies are urgently needed.

7 Protective effect of NGE and NG against IRI

Experimental studies have found that NGE and NG improve IRI in the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, and other organs (Table 3; Table 4). Through this review, we found that NGE and NG alleviated IRI through multiple pathways involving the inhibition of oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, ferroptosis, and pyroptosis and the regulation of autophagy.

TABLE 3

| Type of disease | Experimental model | Dose/route | Key quantitative outcome | Primary proposed mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial IRI | Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/4, 6 h) | 50 mg/kg/days, i.g., 5 days | ↑LVSP, +dP/dtmax, −dP/dtmax ↓Infarct size |

Anti-apoptotic Anti-oxidative stress Anti-ER stress Activating cGMP-PKGIα signaling |

Yu et al. (2019b) |

| H9C2 cells (H/R: 1 h/4 h) | 80 μM, 6 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| Male SD diabetic rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 25 and 50 mg/kg/days, p.o., 30 days | ↑LVSP, ±dP/dtmax ↓Infarct size, CK-MB, LVEDP |

Anti-oxidative stress Upregulating the miR-126-PI3K/AKT axis |

Li et al. (2021b) | |

| SD rats (I/R: 30 min/4 h) | 10 and 50 mg/kg/days, i.g., 7 days | ↓Myocardial infarct size | Anti-ferroptosis Regulating the Nrf2/system xc-/GPX4 axis |

Xu et al. (2021) | |

| H9C2 cells (H/R: 6 h/12 h) | 20, 40, and 80 μM, 24 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| H9C2 cells (H/R: 6 h/12 h) | 40, 80, and 160 μM | ↑Cell viability | Anti-ER stress Anti-apoptotic |

Tang et al. (2017) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/4, 6 h) | 50 mg/kg/days, 7 days | ↑LVSP, +dP/dtmax, −dP/dtmax ↓Infarct size |

Anti-oxidative stress Anti-apoptotic Activating AMPK–SIRT3 signaling |

Yu et al. (2019a) | |

| H9C2 cells (H/R: 1 h/4 h) | 80 μM, 6 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 50 mg/kg/days, i.g., 7 days | ↓Myocardial pathological damage | Regulating the miR-24-3p/Cdip1 axis | Jin et al. (2024b) | |

| H9C2 cells (H/R: 6 h/24 h) | 80 μM, 1 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 100 mg/kg, i.p. | ↑LVDP, dP/dt ↓Injured areas |

Activating mitochondrial BK channels | Testai et al. (2013b) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/1–2 h) | 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 40 μM | ↑LVDP, +LVdP/dtmax, –LVdP/dtmax ↓LVEDP, infarct area |

Anti-oxidative stress | Meng et al. (2016) | |

| One-year-old male Wistar rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 100 mg/kg, i.p. | ↓Ai/ALV, calcium up-take, Tl influx into the matrix | Activating the mitoBK channel; | Testai et al. (2017) | |

| Senescent H9C2 cells (H/R: 16 h/2 h) | 4–40 μM, 16 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| SD rats (I/R: 45 min/4 h) | 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg; | ↓CK-MB | Anti-oxidative stress Anti-apoptotic |

Ren et al. (2022) | |

| H9C2 cells (H/R: 6 h/16 h) | 1.25, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 μM, 12 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 100 mg/kg, i.p. | ↑Rate pressure product, time required to reach half-maximal ischemic contracture ↓Ischemic area |

| Testai et al. (2013a) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 100 mg/kg, i.p., 7 days; | ↓cTnI, myocardial pathological damage, infarction area | Anti- ER stress Anti-apoptotic Activating the PI3K/AKT pathway |

Lan et al. (2021) | |

| Cerebral IRI | Male Wistar rats (I/R: 2 h/24 h) | 50 and 100 mg/kg/days, p.o., 30 days | ↑Cognitive function | Anti-oxidative stress; anti-inflammatory Upregulating BDNF/TrkB signaling |

Zhu and Gao (2024) |

| HT22 cells (OGD/R:6 h/24 h) | 80 μM, 24 h | ↑Cell viability | Anti-oxidative stress Anti-apoptosis Anti-inflammatory Activating SIRT1/FOXO1 signaling |

Zhao et al. (2023) | |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 1 h/23 h) | 50 mg/kg/days, p.o., 21 day | ↑Motor coordination skill, grip strength, neurological deficits, tapes removal test ↓Infarct volume, neuronal damage |

Suppressing NF-κB mediated neuroinflammation | Raza et al., 2013 | |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 1 h/1 h) | 50 and 100 mg/kg/days, i.p., 14 days | ↓AQP4; | Anti-DNA damage Anti-inflammatory |

Somuncu, et al., 2021 | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/5.5 h) | 0.1, 1, and 10 mg/kg, iv. | ↓Infarct volume; | Anti-oxidative stress | Saleh et al. (2017) | |

| Mixed neuronal (OGD/R: 24 h/24 h) | 0.25–1,250 μM, 24 h | | |||

| Male SD rats (I/R: 2 h) | 80 μM, i.p. | ↓mNSS score, Wet-Dry weight ratio; | Anti-apoptotic Anti-oxidative stress |

Wang et al. (2017) | |

| Cortical neurons (OGD/R: 2 h/24 h) | 20, 40, and 80 μM, 48 h | ↑Cell viability; | |||

| Male C57BL/6 mice (I/R: 1 h/7 d) | 1, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg/day, i.p., 6 days | ↑Neurological deficits ↓Infarct volumes |

Anti-inflammatory Activating the GSK-3β/β-catenin pathway; |

Yang et al. (2024) | |

| Intestinal IRI | Male C57BL/6J mice (I/R: 45 min/30 min) | 50 and 100 mg/kg/days, i.g., 7 days | ↓Chiu’s score | Anti-oxidative stress; anti-ferroptosis | Hou et al. (2024) |

| IEC-6 cells (OGD/R: 3 h/1 h) | 50, 75, and 100 μM, 12 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| Renal IRI | Male C57Bl/6 mice (I/R: 30 min/24 h) | 50 mg/kg/days, i.g., 3 days | ↓Cr, BUN, kidney injury scores | Anti-ER stress Anti-pyroptosis Anti-apoptosis Activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling |

Zhang et al. (2022) |

| HK-2 cells (H/R: 12 h/4 h) | 5 mM for 24 h | | |||

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 45 min/24 h) | 50 mg/kg/days, i.p., 7 days | ↓Renal tubular injury score, Cr | Anti-inflammatory Inhibiting the NF-κB pathway |

Dai et al. (2021) | |

| Retinal IRI | Male Wistar rats (I/R: 1 h/24 h) | 20 mg/kg, i.p. | ↑Retinal thickness ↓Retinal damage |

Anti-apoptosis | Kara et al. (2014) |

| Male C57BL/6 mice (I/R: 1 h/7 d) | 100 and 300 mg/kg, i.g., 7 days | ↑Number of cells in ganglion cell layer, ganglion cell layer thickness ↓Ocular hypertension |

Inhibiting neuroinflammation Regulating CD38/SIRT1 signaling |

Zeng et al. (2024) | |

| | Female Long–Evans rats (I/R: 30 min/240 min) | 10 mg/kg, i.p.; | ↑b-wave of electroretinogram; | | Chiou and Xu, 2004 |

Protective effect of NGE against organ IRI.

Abbreviations: AKT, protein kinase B; AMPK, adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase; AQP4, aquaporin-4; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CK, creatine kinase; Cr, creatinine; cGMP, cyclic guanosine monophosphate; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FOXO1,: forkhead box O1; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; H/R, hypoxia–reoxygenation; HO-1, heme oxygenase (decycling) 1; i. g., intragastric; i. p., intraperitoneal; i. v., intravenous; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; LVEDP, left ventricular end-diastolic pressure; LVSP, left ventricular systolic pressure; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; Nrf2, nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; OGD/R, oxygen and glucose deprivation/reperfusion; p.o., oral administration; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PKGIα, protein kinase GIα; SIRT, silent information regulator; TrkB, tyrosine receptor kinase B.

TABLE 4

| Type of disease | Experimental model | Dose/route | Key quantitative outcome | Primary proposed mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myocardial IRI | AC16 cells (OGD/R: 6 h/6 h) | 200 μM | ↑ Cell viability | Anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, regulating miR-126/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling | Guo et al. (2022) |

| Male SD rat (I/R: 30 min/1–7 days) | 50 mg/kg | ↓ Myocardia damage | |||

| Male wistar rats (I/R: 40 min/45 min) | 40 and 100 mg/kg/day, i.g., 8 weeks | ↑ LVDP, dp/dtmax ↓Myocardial hypertrophy, CK-MB |

Anti-oxidative stress, anti-inflammatory | Shackebaei et al. (2024) | |

| Male SD rat (I/R: 30 min/3 h) | 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg/days, i.p., 7 days | ↑ Fractional shortening ↓ CK-MB, cTnI, damage score, infarct size |

Anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory Anti-oxidative stress Anti-autophagy Activating PI3K/AKT signaling |

Li et al. (2021a) | |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 30 min/1 h) | 25 mg/kg/days, 7 days | ↑ LVDP, +dP/dt, −dP/dt; ↓ Arrhythmia episodes, myocardial infarct area |

Anti-apoptotic Anti-oxidative stress |

Araujo et al. (2023) | |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 45 min/1 h) | 20, 40, and 80 mg/kg/days, p.o., 14 days | ↑ ±LVdP/dt max ↓ LVEDP, CK-MB |

Anti-inflammatory Anti-oxidative stress Regulating Hsp27, Hsp70, p-eNOS/p-Akt/p-ERK signaling |

Rani et al. (2013) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/4 h) | 5 mg/kg, i.p., 5 days | ↓Myocardial infarction size, CK-MB, cTnl | Anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory Anti-oxidative stress Activating SIRT1 signaling |

Liu et al. (2022a) | |

| Cerebral IRI | Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 10, 50, and 100 mg/kg, i.p. | ↓ Myocardial infarction area, myocardial pathological damage, CK | Anti-pyroptosis | Wang T. T. et al. (2021) |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 30 min/2 h) | 10, 20, and 40 mg/kg/days, i.g., 7 days | ↓ Apoptotic cells | Anti- ER stress Anti-apoptotic |

Liu et al. (2018a) | |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 30 min/7.14 days) | 100 mg/kg/days, i.g., 14 days | ↓ Neurologic score, rotarod test values | Increasing neurogenesis | Yilmaz et al. (2024) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 2 h/24 h) | 5 mg/kg/days, i.p., 7 days | ↓ Brain water content, cerebral infarction volume, neurological deficit score | Anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory Activating the PI3K/AKT pathway |

Yang et al. (2020) | |

| Primary nerve cells (OGD: 72 h) | 6, 12, and 25 μg/mL, 48 h | ↑ Cell viability | |||

| SH-SY5Y cells (OGD/R: 10 h/14 h) | 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 150, and 200 μM, 24 h | ↑ Cell viability | Attenuating mitophagy | Feng et al. (2018) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 2 h/22 h | 120 mg/kg, i.v. | ↓ Neurological deficit score, pathomorphological injury, infarct size | |||

| PC12 cells (OGD/R: 2 h/12 h) | 0, 1, 5, 10, and 50 μM | ↑ Cell viability | Anti-apoptosis, Targeting NFKB1; Modulating HIF-1α/AKT/mTOR signaling |

Cao et al. (2021) | |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 30 min/24 h) | 50 and 100 mg/kg, i.p., 7 days | ↑ Hanging latency time, locomotor activity ↓ Neurological score, pathomorphological injury |

Anti-oxidative stress Anti-free radical scavenging property |

Gaur et al. (2009) | |

| Females and males, SD rats (I/R: 2 h/24 h) | 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg/days, i.g., 7 days | ↓ Zea-Longa score, infarct size, brain water content | Anti-oxidative stress, anti-inflammatory, anti-ER stress | Wang L. et al. (2021) | |

| Intestinal IRI | Male Wistar rats (I/R: 2 h/2 h) | 50 mg/kg, i.p. | ↓ Chiu’s score | Anti-oxidative stress | Bakar et al. (2019) |

| Male Wistar rats (I/R: 2 h/2 h) | 50 mg/kg, i.p. | | Anti-oxidative stress | Cerkezkayabekir et al. (2017) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 1 h/2 h) | 50 and 100 mg/kg/days, i.g., 3 days | ↓ Chiu’s score | Anti-oxidative stress Anti-apoptosis, anti-inflammatory Deactivating cGAS–STING signaling |

Gu et al. (2023) | |

| IEC-6 cells (H/R: 12 h/4 h) | 16, 32, 64, 128, and 256 μM, 12 h | ↑Cell viability | |||

| Male SD rats (I/R: 1 h/1 h) | 80 mg/kg, i.p. | ↓ Chiu’s score | | Isik et al. (2015) | |

| Renal IRI | Male Wistar rats (I/R: 45 min/72 h) | 50 and 100 mg/kg/day, i.p., 3 days | ↓ HE staining score | Anti-inflammation Anti-apoptosis |

Danis et al. (2024) |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 45 min/4 h) | 100 mg/kg/days, i.p., 7 days | | Anti-oxidative stress Activating Nrf2 expression |

Amini et al. (2019a) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 45 min/24 h) | 400 mg/kg, p.o. | ↑ Creatinine clearance ↓ Histopathological injury, Cr, BUN |

Anti-oxidative stress | Singh and Chopra (2004) | |

| Male SD rats (I/R: 45 min/4 h) | 100 mg/kg/days, i.p., 7 days | ↑ Renal blood flow, creatinine clearance, fractional excretion of sodium ↓ Histopathology scoring, BUN, Cr |

Anti-oxidative stress Anti-apoptosis |

Amini et al. (2019b) | |

| | Male SD rats (I/R: 45 min/4 h) | 100 mg/kg/days, i.p., 7 days | ↑ Nucleus tractus solitarius electrical activity, baroreceptor sensitivity | | Amini et al. (2021) |

| | Male SD rats (I/R: 45 min/4 h) | 100 mg/kg/days, i.p., 3 days | | Anti-oxidative stress Preserving the kidney mitochondria |

Amini and Goudarzi,2022 |

| Hindlimb IRI |

Male SD rats (I/R: 2 h/2 h) | 400 mg/kg, p.o., three times with an 8 h interval | | Anti-oxidative stress | Gürsul et al., 2016 |

| Testicular IRI |

Male Wistar rats (I/R: 4 h/4 h) | 5 and 10 mg/kg, i.p. | ↓ Histological injury | Anti-oxidative stress | Akondi et al. (2011) |

| Spinal cord IRI |

Female SD rats (I/R: 30 min/1–7 days) | 50 and 100 mg/kg, i.p., 7 days | ↑ Locomotor function, BBB score ↓ Spinal edema |

Anti-inflammatory Anti-oxidative stress |

Cui et al. (2017) |

| Liver IRI | Male SD rats (I/R: 70 min/2 h) | 80 mg/kg, i.p. | | Anti-oxidative stress | Gursul et al., 2017 |

Protective effect of NG against organ IRI.

Abbreviations: AKT, protein kinase B; BBB, Basso, Beattie, and Bresnahan; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; cGAS, cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate synthase; CK, creatine kinase; Cr, creatinine; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; GSK, glycogen synthase kinase; HIF-1α, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α; i. g., intragastric; i. p., intraperitoneal; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; LVDP, left ventricular diastolic pressure; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; Nrf2, nuclear factor E2-related factor 2; OGD/R, oxygen and glucose deprivation/reperfusion; p. o., oral administration; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; SIRT, silent information regulator; STING, stimulator of interferon genes.

7.1 Inhibition of oxidative stress

Several studies have concluded that oxidative stress leads to IRI (Yi et al., 2023). During oxidative stress, cells are exposed to pathogenic stimuli, which produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen oxides (Zhang et al., 2025). Superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), glutathione (GSH), and glutathione peroxidase (GPX) are endogenous antioxidant enzymes that eliminate free radicals (Yuan et al., 2021). The imbalance between antioxidants and oxidation results in cell death, which is a major cause of IRI (Ramachandra et al., 2020). Several in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that NGE and NG protect against IRI by attenuating oxidative stress. In the IRI models of the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, hindlimb, testicles, spinal cord, and liver, NGE and NG increased SOD, GPX, GSH, and CAT levels and reduced ROS and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels (Akondi et al., 2011; Amini and Goudarzi, 2022; Amini et al., 2019a; b; Araujo et al., 2023; Bakar et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2021; Cui et al., 2017; Gaur et al., 2009; Gu et al., 2023; Gürsul et al., 2016; Gursul et al., 2017; Hou et al., 2024; Isik et al., 2015; Jin X. et al., 2024; Li F. et al., 2021; Li S. H. et al., 2021; Liu Y. et al., 2022; Meng et al., 2016; Rani et al., 2013; Raza et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2022; Saleh et al., 2017; Shackebaei et al., 2024; Singh and Chopra, 2004; Wang et al., 2017; Wang T. T. et al., 2021; Wang T. T. et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2019a; Yu et al., 2019b; Zhao et al., 2023; Zhu and Gao, 2024). 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) is a product of oxidative metabolism (Somuncu et al., 2021). In diabetic myocardial IRI rats and cerebral IRI rats, NGE decreased 8-OHdG levels (Li S. H. et al., 2021; Somuncu et al., 2021). Furthermore, IRI increases the activity of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), thereby promoting nitric oxide (NO) formation (Yuan et al., 2021). When NO combines with the superoxide anion to form peroxynitrite, it induces oxidative stress (Wu et al., 2010). NG possessed a strong peroxynitrite (ONOO−) scavenging capability (Feng et al., 2018). In cerebral and intestinal IRI models, NG inhibited iNOS and nNOS expressions and prevented NO release (Cerkezkayabekir et al., 2017; Feng et al., 2018; Raza et al., 2013). Researchers have found that arginase inhibits oxidative stress by regulating NO production in IRI. In intestinal IRI, arginase activity was significantly elevated, whereas NG alleviated oxidative stress by reducing arginase activity (Cerkezkayabekir et al., 2017).

7.2 Inhibition of inflammation

Inflammation is considered a crucial factor in pathophysiological variations following IRI (Mo et al., 2020). In IRI, neutrophils are recruited and release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, exacerbating cellular damage (Hou et al., 2023). Several studies have reported that NGE and NG have anti-inflammatory effects on IRI. In IRI models of the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, and spinal cord, NGE and NG reduced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) (Cui et al., 2017; Dai et al., 2021; Danis et al., 2024; Gu et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2022; Li F. et al., 2021; Liu Y. et al., 2022; Rani et al., 2013; Raza et al., 2013; Shackebaei et al., 2024; Wang L. et al., 2021; Wang T. T. et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023; Zhu and Gao, 2024). Meanwhile, NGE and NG remarkably increased IL-10 levels in middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion (MCAO/R)-induced cerebral IRI rats and in oxygen and glucose deprivation/reperfusion (OGD/R)-induced HT22 cells (Wang l. et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2023). In intestinal IRI-induced rats and hypoxia–reoxygenation (H/R)-induced IEC-6 cells, NG reduced interferon (IFN)-β levels (Gu et al., 2023). Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is an enzyme secreted by neutrophils and macrophages during inflammation, and it is highly expressed during IRI (Netala et al., 2025). It has been shown that NGE and NG reduced MPO levels in the IRI of the myocardium, brain, intestines, and spinal cord (Cui et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2023; Raza et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2021). As a key rate-limiting enzyme, cyclooxygenase (COX) plays a critical role in the biosynthesis of prostanoids, which activate complex inflammatory cascades (Jiang and Yu, 2021). A study of MCAO/R-induced cerebral IRI rats found that NGE treatment decreased COX-2 expression (Raza et al., 2013).

7.3 Inhibition of apoptosis

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death process activated by IRI (Sun et al., 2025). According to the studies, apoptosis occurs in almost all IRI pathological processes (Zhai et al., 2024). Following IRI, expression of B-cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) was significantly downregulated, whereas Bcl-2-associated X (Bax) and cleaved caspase-3 were significantly elevated (Yu et al., 2019a). Numerous experiments have shown that NGE and NG protect IRI through anti-apoptotic mechanisms. In IRI models of the myocardium, brain, intestines, and kidneys, NGE and NG reduced apoptosis index, cleaved caspase-3, and Bax levels and significantly increased Bcl-2 expression (Amini et al., 2019b; Araujo et al., 2023; Cao et al., 2021; Danis et al., 2024; Gu et al., 2023; Guo et al., 2022; Kara et al., 2014; Lan et al., 2021; Li F. et al., 2021; Liu Y. et al., 2022; Rani et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2022; Tang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2019a; Yu et al., 2019b; Zhang et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2023). Caspase-9, an essential caspase that initiates apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway, is activated during the apoptotic process (Würstle et al., 2012). In a study of OGD/R-induced cortical neurons, NGE inhibited caspase-9 (Wang et al., 2017).

7.4 Inhibition of ER stress

The presence of ER stress also contributes to IRI (Feng et al., 2019). During IRI, free radicals and hypoxia exposure disrupt ER homeostasis, leading to ER stress (Feng et al., 2019). ER stress is triggered by accumulating misfolded and unfolded proteins, which are marked by glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78), unfolded protein response (UPR), and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein (CHOP) (Yu et al., 2019b; Zhang J. et al., 2024). Meanwhile, ER stress is mediated by three ER stress sensors: inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), and protein kinase R-like ER kinase (PERK) (Jin H. et al., 2024). Caspase-12 is found in the ER cytoplasm and mediates the death of cells exposed to ER stress (Momoi, 2004). According to studies, NGE and NG significantly inhibited ER stress, as evidenced by a reduction in CHOP, GRP78, and cleaved caspase-12 in myocardial IRI, cerebral IRI, and renal IRI (Lan et al., 2021; Liu D. et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2017; Wang L. et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2019b; Zhang et al., 2022). In myocardial IRI rats and H/R-induced H9C2 cells, NGE also decreased ATF6 (Tang et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2019b). NGE treatment inhibited ER stress via activation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase Iα signaling (Yu et al., 2019b). Meanwhile, in MCAO/R-induced cerebral IRI rats, NG also improved ER stress by decreasing ATF6 (Wang L/et al., 2021).

7.5 Inhibition of ferroptosis

Ferroptosis is a significant driver of IRI and organ failure, especially in the later phases of reperfusion (Cai et al., 2023). In contrast to other forms of cell death, ferroptosis causes mitochondrial dysfunction, abnormal iron metabolism, and an imbalance in the GPX4/GSH axis (Li J. et al., 2020). In several studies, NG and NGE inhibited ferroptosis, protecting against IRI. In myocardial IRI rats, NGE significantly reduced Fe2+ and total iron levels, while ferritin heavy chain 1, solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), and GPX4 levels were significantly increased (Xu et al., 2021). In a study of intestinal IRI, NGE decreased long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4 and iron levels while increasing GPX4 and SLC7A11 levels (Hou et al., 2024). In intestinal IRI, NGE inhibited ferroptosis by activating Yes-associated protein, which regulated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 phosphorylation (Hou et al., 2024).

7.6 Regulation of autophagy

Among metabolic pathways, autophagy plays a crucial role in cell survival (Ding et al., 2024). Autophagy involves the engulfment of organelles and metabolic waste into the autophagosome, which then fuses with the lysosome to eliminate them (Debnath et al., 2023). In IRI, autophagy plays a double-edged role (Ding et al., 2024). When autophagy is activated during ischemic conditions, metabolic waste is removed and protects cells, whereas excessive autophagy upon reperfusion results in the depletion of intracellular components and eventual cell death (Mokhtari and Badalzadeh, 2022). Autophagy can be assessed by several autophagy-related proteins, including light chain (LC) 3B, Beclin 1, and P62 (Gao et al., 2022). A study of myocardial IRI found that NG enhanced autophagy levels by increasing autophagosome formation, autophagy flux, Beclin 1, and LC3B-II/LC3B-I while reducing P62 (Li F. et al., 2021). In cerebral IRI, researchers found that NG lowered the ratio of LC3B-II/LC3B-I in mitochondrial fractions and inhibited Parkin translocation into mitochondria (Feng et al., 2018).

7.7 Inhibition of pyroptosis

Unlike necrosis and apoptosis, pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of cell death that causes the formation of plasma membrane pores, cell swelling, osmotic lysis, and the release of inflammatory factors such as IL-1β and IL-18 (Du et al., 2025). Pyroptosis can be induced by caspase-1, 4, 5, or 11 and mediated by gasdermin D (GSDMD) (Zhang S. et al., 2024). Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein (ASC) and procaspase-1 are recruited by Nod-like receptor protein 3 (NLRP3) to form inflammasomes, which initiate pyroptosis. In turn, this triggers GSDMD, which leads to cell death, also known as the classical pathway to pyroptosis (Liu W. et al., 2022). Pyroptosis is crucial to IRI progression. Many experiments have demonstrated that NGE and NG inhibit pyroptosis in IRI. In myocardial IRI rats, NG inhibited pyroptosis by decreasing ASC, caspase-1, NLRP3, and GSDMD levels (Wang L. et al., 2021). It was also found that NGE significantly inhibited the pyroptosis-related markers, including NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, in renal IRI (Zhang et al., 2022).

7.8 Other mechanisms

There is evidence that ischemia triggers neurogenesis in the usual neurogenic niches, namely, the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle and the subgranular zone of the dentate gyrus (Jhelum et al., 2022). It was found that NG significantly increased neurogenesis in cerebral IRI rats by restoring the mature neuron marker (NeuN) and immature neuron marker (DCX) (Yilmaz et al., 2024). In terms of adult neurogenesis and stroke-induced neurogenesis, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is the most extensively researched neurotrophic factor (Leal et al., 2017). An increase in BDNF levels enhanced learning, memory, and function in animals induced by cerebral IRI (Ni et al., 2020). A study found that NG increased BDNF levels in the cerebral IRI, contributing to neurogenesis (Yilmaz et al., 2024).

As a specific barrier between the blood and the brain, the BBB maintains brain stability by regulating the transport of beneficial and harmful substances between the blood and the brain (Hu et al., 2024). After cerebral IRI, BBB integrity is compromised, resulting in increased paracellular permeability and allowing the passage of toxins, inflammatory factors, and immune cells into the brain, ultimately leading to brain edema and death (Liao et al., 2020). Strategies targeting BBB integrity may be valuable for preventing disability and enhancing recovery after cerebral IRI (Hou et al., 2023). Tight junction (TJ) proteins are critical for BBB integrity. It has been found that ischemic injuries result in reduced levels of TJ proteins, including zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1) and claudin-5 (Hu et al., 2024). In MCAO/R-induced cerebral IRI rats, NGE increased TJ expression (occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1) and prevented Evans blue dye leakage (Yang et al., 2024). It has been found that GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling is required for NGE-alleviated BBB in cerebral IRI (Yang et al., 2024).

8 Signaling pathways and target proteins of NGE and NG in protection against IRI

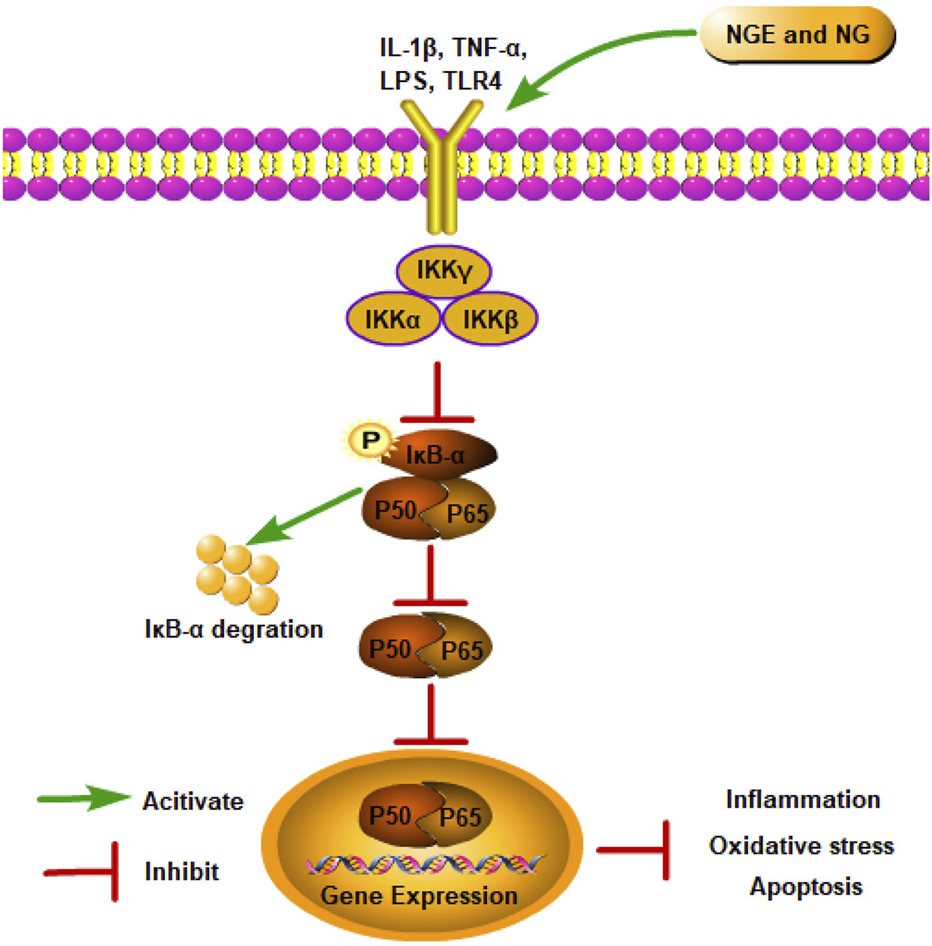

8.1 NF-κB signaling pathway

As a classical signaling pathway, the NF-κB pathway is involved in inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death (Gasparini and Feldmann, 2012). At rest, NF-κB exists in the cell as an inactive dimer bound to the inhibitor protein (IκB) (Karin, 1999). After IRI, cells are stimulated, and IκB proteins are degraded through phosphorylation, triggering NF-κB activation (Li et al., 2022). Activated NF-κB translocates into the nucleus and exerts its transcriptional function, enhancing the production of inflammatory factors and ultimately aggravating IRI (van Delft et al., 2015).

As shown in MCAO/R-induced cerebral IRI rats and kidney IRI rats, NGE treatment reduced oxidative stress and inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB signaling (Dai et al., 2021; Raza et al., 2013). In OGD/R-induced PC12 cells, NG inhibited apoptosis by suppressing NF-κB signaling (Cao et al., 2021). In myocardial IRI, NG alleviated inflammation by suppressing IKK-β/NF-κB (Rani et al., 2013). Additionally, NG showed neuroprotective effects by downregulating excessive free radicals and decreasing inflammation markers via inhibition of NF-κB signaling in spinal cord IRI rat models (Cui et al., 2017) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

NGE and NG alleviate IRI by inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway.

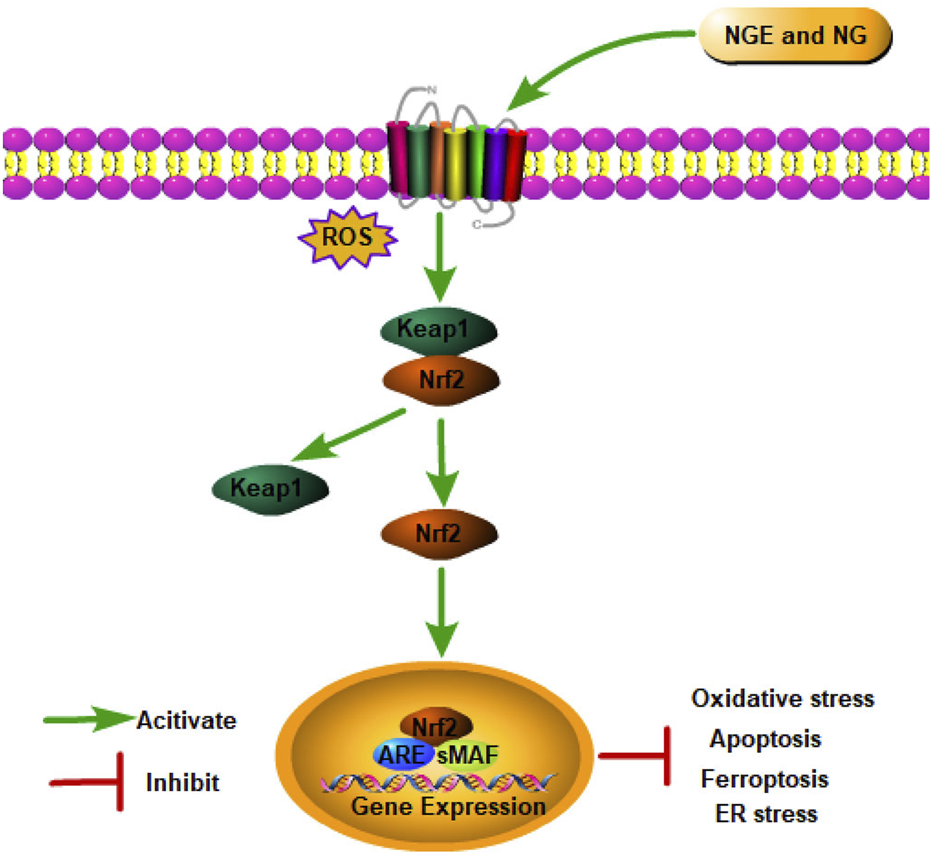

8.2 Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 signaling pathway

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), an essential nuclear transcription factor, serves as a key regulator in mediating the intracellular antioxidant defense system (Zhang et al., 2022). Physiologically, Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1 (Keap1) degrades Nrf2 via ubiquitination complex-dependent mechanisms to maintain Nrf2 dormancy (Sun et al., 2023). As soon as Keap1 is degraded after IRI, its inhibitory effect on Nrf2 is lost. Subsequently, Nrf2 is transferred to the nucleus to activate antioxidant genes (such as heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 (HO-1)) and antioxidant enzymes by forming a heterodimer with the Maf protein (Zhang et al., 2022). In addition to maintaining redox homeostasis, Nrf2 also regulates inflammation and metabolism (Mata and Cadenas, 2021).

In myocardial IRI, NGE improved IRI and alleviated oxidative stress by activating Nrf2 signaling (Xu et al., 2021). In cerebral IRI, NGE exerted antioxidant and anti-apoptosis effects by regulating the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway (Wang et al., 2017). NGE was also shown to inhibit ferroptosis by regulating the Nrf2/GPX4 axis, thus alleviating myocardial IRI in rats (Xu et al., 2021). A study conducted on rats with renal IRI found that NG increased Nrf2 expression in kidney tissue, which improved oxidative stress (Amini et al., 2019b). Meanwhile, the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway plays a significant role in ER stress (Yu et al., 2022). In renal IRI, NGE administration attenuated apoptosis and pyroptosis in part by inhibiting ER stress through the activation of Nrf2/HO-1 signaling (Zhang et al., 2022) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

NGE and NG alleviate IRI by activating the Nrf2 signaling pathway.

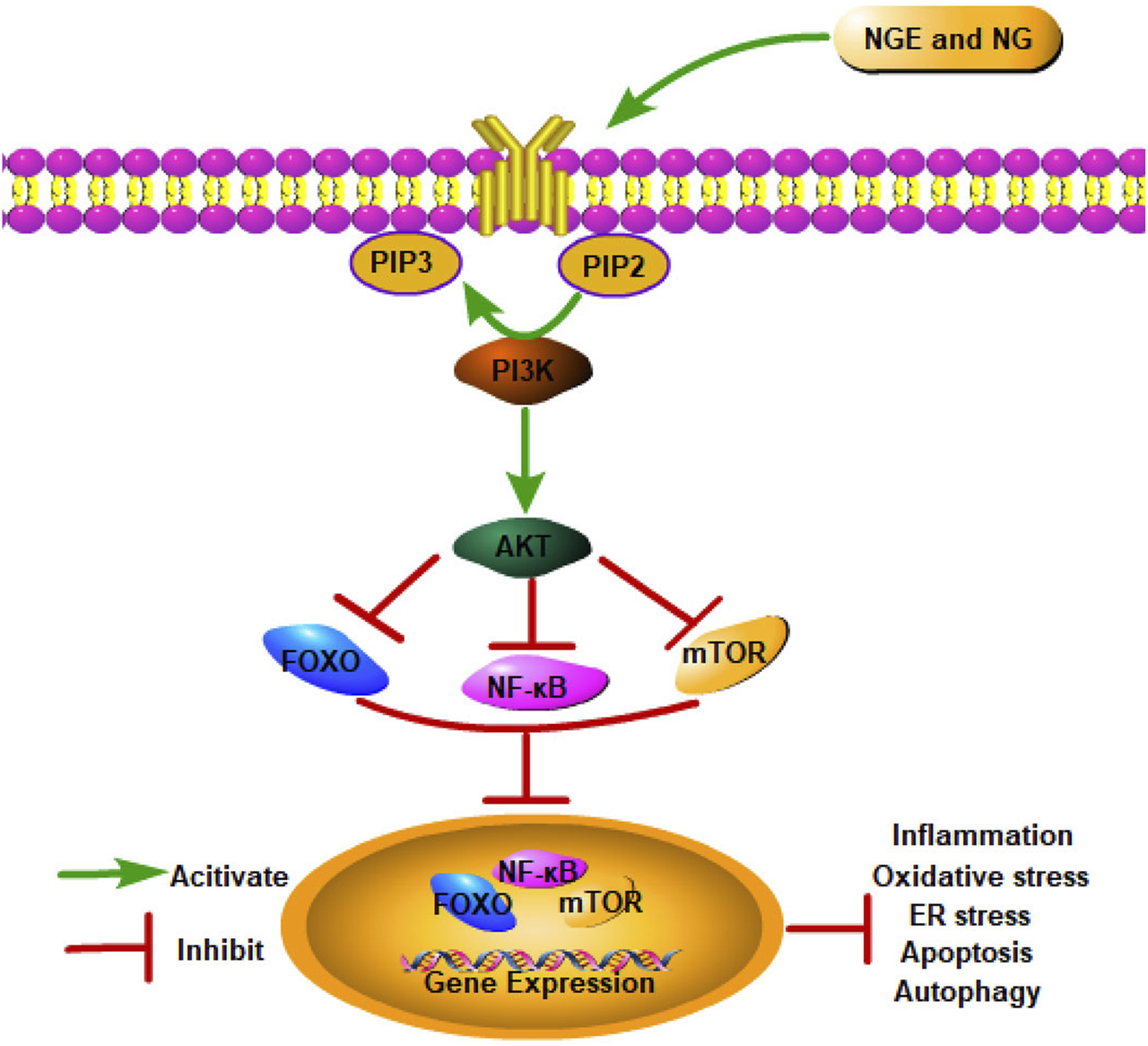

8.3 Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT signaling pathway

As a bridge between extracellular signals and cellular reactions, the Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling pathway regulates cell growth, proliferation, survival, and metabolism (Fukuchi et al., 2004). As PI3K is activated, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate is formed on the plasma membrane, which changes AKT conformation. Thr308 and Ser473 are the two most significant phosphorylation sites exposed by AKT after it migrates to the cell membrane. Following the phosphorylation of Thr308 and Ser473 by PDK1 and PDK2, AKT is fully activated, regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Mayer and Arteaga, 2016). As a critical signaling pathway, PI3K/AKT plays a crucial role in IRI.

In myocardial IRI, NGE and NG were reported to suppress the IRI-induced cardiac apoptosis, oxidative stress, and inflammation by facilitating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (Lan et al., 2021; Li F. et al., 2021). As a result of activating PI3K/AKT signaling, NGE also significantly reduced ER stress in myocardial IRI (Lan et al., 2021). Meanwhile, in myocardial IRI rats, NG inhibited autophagy by activating the PI3K/AKT pathway (Li F. et al., 2021). In cerebral IRI, NG inhibited inflammation and apoptosis via activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway (Yang et al., 2020) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

NGE and NG alleviate IRI by activating the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway.

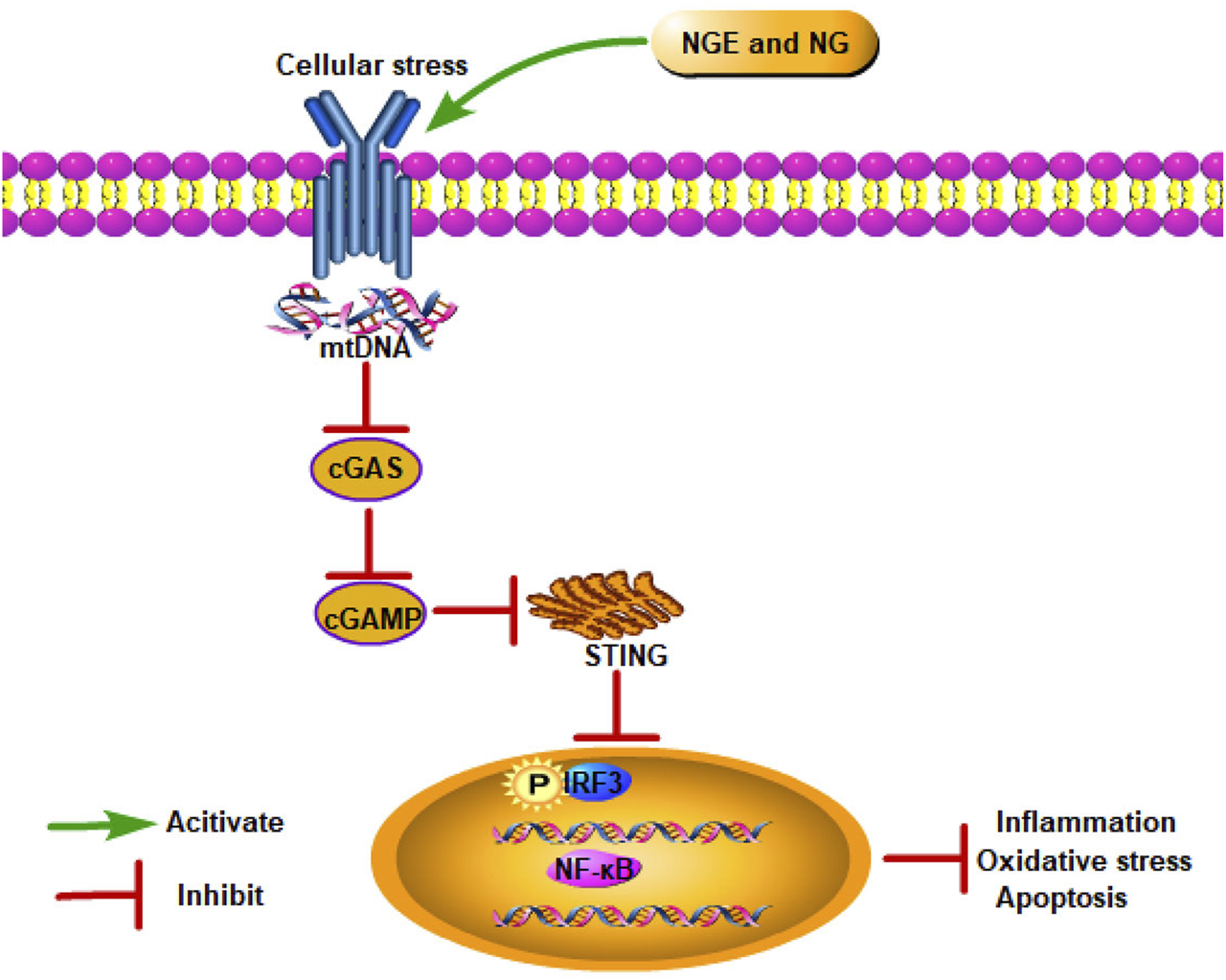

8.4 Cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate synthase–stimulator of interferon genes signaling pathway

In recent studies, the cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate synthase–stimulator of interferon genes (cGAS–STING) signaling pathway has been found to be critical to IRI progression (Lei et al., 2022). As a DNA pattern recognition receptor, cGAS recognizes DNA and generates cGAMP to activate STING, subsequently activating NF-κB and IFN regulatory factor (IRF) 3 via TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) (Gu et al., 2023). After translocating to the nucleus, NF-κB and IRF3 trigger interferon type I synthesis (IFN-β) and inflammatory cytokines (Wu et al., 2013). In intestinal IRI, NG alleviated inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis by blocking cGAS–STING signaling (Gu et al., 2023) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

NGE and NG alleviate IRI by inhibiting the cGAS–STING signaling pathway.

8.5 Sirtuin 1/Sirtuin 3

Sirtuin (SIRT) 1 is a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent histone deacetylase that deacetylates a variety of histones and non-histones (D'Onofrio et al., 2018), modulating downstream targets such as forkhead box O1 (FOXO1) to modulate pathological processes including oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis (Zhao et al., 2023). In myocardial IRI, NG reduced oxidative stress, inflammatory response, and apoptosis by activating the SIRT1 pathway (Liu Y. et al., 2022). In cerebral IRI in vitro, NGE also inhibited oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis by enhancing SIRT1/FOXO1 signaling (Zhao et al., 2023). CD38 is a transmembrane glycoprotein that operates via receptors and enzymes to regulate inflammation or autoimmune responses (Zeng et al., 2024). A study found that NGE inhibited astrocyte activation in retinal IRI by regulating CD38/SIRT1 signaling, which ultimately reduced retinal inflammation (Zeng et al., 2024). Under stress conditions, SIRT3, a central modulator of mitochondrial protein acetylation, preserves myocardial mitochondrial function and acts as a major downstream component of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in modulating cardiomyocyte survival (Yu et al., 2019a). A study in myocardial IRI found that NGE decreased mitochondrial oxidative stress and promoted mitochondrial biogenesis by activating the AMPK–SIRT3 pathway (Yu et al., 2019a).

8.6 Hypoxia-inducible factor -1α

As a transcriptional regulator of the cellular response to hypoxia, hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α activates multiple hypoxia-responsive genes to regulate energy metabolism and maintain oxygen homeostasis (Koyasu et al., 2018). Under hypoxic conditions, prolyl hydroxylase activity is inhibited, preventing the degradation of HIF-1α, which is then induced to enter the nucleus and bind to HIF-1β, thus regulating tissue cells to adapt to a hypoxia environment (Shang et al., 2024). It was found that NG normalized HIF-1α levels and alleviated kidney tissue damage in renal IRI (Danis et al., 2024). Meanwhile, in cerebral IRI, NG was shown to inhibit cell apoptosis by modulating the HIF-1α/AKT/mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (Cao et al., 2021).

9 Future recommendations

In future studies, it will be imperative to address the following issues. More research is needed to determine whether NGE and NG are effective and safe for patients. It is also critical to improve NGE and NG bioavailability and pharmacokinetics for clinical applications. In clinical trials, new formulations and techniques such as nanocarriers and crystallization modifications that improve NGE and NG bioavailability and release should also be investigated. At present, NGE and NG are the primary culprits in grapefruit-associated food–drug interactions. It is imperative to explore the mechanisms of drug–drug interactions (augmentation or attenuation) before conducting clinical trials. In addition to determining the correct dose and duration of investigation, it is also imperative to consider the impact of other drugs or supplements that may interact with flavonoids. Meanwhile, research on intestinal microflora would enrich our understanding of the mechanisms behind NGE and NG therapeutic effects in the future. As different flavonoids synergize, combination drug therapy merits further research.

10 Discussion

IRI is associated with complex pathological processes, which can be life-threatening, and can be found in various tissues, such as the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, retina, and liver (Lu et al., 2021). Inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, and multiple cell death pathways are involved in IRI pathogenesis and are common across different organs (Li et al., 2025). Furthermore, clinical manifestations of IRI vary considerably across organ systems and are further affected by patients’ underlying conditions, posing difficulties in diagnosis and treatment (Li et al., 2025).

Currently, there are many strategies for preventing and treating IRI. In light of their therapeutic effects and minimal side effects, natural products hold substantial promise in reducing IRI in various organs (Kumar et al., 2025). The natural dietary flavonoids NGE and NG have been shown to exhibit potential therapeutic effects against IRI in preclinical models. In this article, we summarize the recent relevant studies on NGE and NG for treating IRI, covering the myocardium, brain, intestines, kidneys, retina, liver, spinal cord, skeletal muscles, and testicles. Consistent with our review, other flavonoids (quercetin, hesperidin, and luteolin) have also shown protective effects against IRI (Kumar et al., 2025; Xu et al., 2024). Meanwhile, other natural products, such as phenols, terpenoids, and polysaccharides, have been shown to be beneficial for IRI in a variety of organs (Dong et al., 2016; Kumar et al., 2025). In this review, studies focused on the myocardium, brain, kidneys, and intestine. However, research on the retina, liver, spinal cord, skeletal muscles, and testicles is scarce, and further studies are needed.

It has been shown that many signaling pathways (NF-κB, Wnt, Nrf2, and AMPK) are involved in IRI, and they show cross-talk with inflammation, oxidative stress, and programmed cell death, forming a complex network (Zhang M. et al., 2024). In this review, we summarize for the first time the multiple signaling pathways modulated by NGE and NG in organ IRI, which include NF-κB, Nrf2, PI3K/AKT, cGAS–STING, SIRT1/SIRT3, and HIF-1α. Furthermore, we investigate the interactions between these signaling pathways and inflammation, oxidative stress, and programmed cell death. At present, most research remains preliminary, and further studies are required to clarify the cross-talk mechanisms.

Currently, there are few clinical trials of NGE and NG. Studies have found that NGE and NG play a role in hyperlipidemic and overweight patients (Dallas et al., 2014; Salehi et al., 2019). As of now, we have not found any published clinical trials directly related to IRI for NGE and NG. As more preclinical studies report positive results, clinical translation should be accelerated. However, NGE and NG still face many challenges and require well-designed trials utilizing precision medicine approaches and nanotechnology-enabled delivery systems to confirm experimental results in human clinical trials.

11 Limitations of the study

Despite this, current research on NGE and NG for the prevention and treatment of IRI has several limitations. First, IRI experiments involve animal and cell experiments. It is difficult to maximize the value of research results because of the differences between experimental animals, modeling methods, and the timing of IRI. Meanwhile, some studies fell short of the high scientific standards. In light of the limited number of studies, we did not exclude any studies based on their quality. Second, the research methods are relatively simple, and most studies measure relevant indicators repeatedly. Although numerous signaling pathways have been identified, there is still no clear understanding of how they interact or regulate one another. Third, we focus exclusively on the biological effects of NGE or NG as there have been very few comparative studies between them. Most animal experiments compare the effects of different dose gradients of NGE and NG longitudinally with modeled groups, but there are few cross-sectional efficacy comparisons with positive control drugs. Finally, only NGE and NG were analyzed for their effects on organ IRI. Other structurally related flavonones, such as hesperidin and nobiletin, were not evaluated. The potential of flavonones to improve organ IRI has not been fully explored.

12 Conclusion

During this review, we found that NGE and NG possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, anti-ER stress, anti-ferroptosis, anti-pyroptosis, and autophagy regulation properties that protect organs from IRI. Furthermore, NGE and NG reduced organ IRI through certain signaling pathways, including NF-κB, Nrf2, PI3K/AKT, cGAS–STING, SIRT1/SIRT3, and HIF-1α, which were summarized for the first time. Overall, NGE and NG show considerable promise in preclinical organ IRI models. A clear statement must be made that the protective effects of NGE and NG on organ IRI remain at the preclinical trial stage. Further studies are needed to verify their safety and efficacy in clinical settings.

Statements

Author contributions

MH: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing. DW: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Validation, Formal Analysis. YW: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Validation. XZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review and editing. ZY: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This project was supported by grants from the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (No. ZR2024QH113), Shandong Province medical health science and technology project (No. 202307010965) and Tai'an Science and Technology Innovation Development Project (No. 2023NS456).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Glossary

- 8-OHdG

8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine

- ASC

Apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a carboxy-terminal

- ATF6

Activating transcription factor 6

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X

- BBB

Blood–brain barrier

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma-2

- BDNF

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- CAT

Catalase

- cGAS

Cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate synthase

- CHOP

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein homologous protein

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- FOXO1

Forkhead box O1

- GPX

Glutathione peroxidase

- GRP78

Glucose-regulated protein 78

- GSDMD

Gasdermin D

- GSH

Glutathione

- H/R

Hypoxia–reoxygenation

- HIF

Hypoxia-inducible factor

- HO-1

Heme oxygenase (decycling) 1

- IFN

Interferon

- IL

Interleukin

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IRE1α

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1α

- IRF

IFN regulatory factor

- IRI

Ischemia/reperfusion injury

- Keap1

Kelch-like ECH-associated protein-1

- LC

Light chain

- MACO/R

Middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion

- MAPK

Mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MDA

Malondialdehyde

- MPO

Myeloperoxidase

- NF-κB

Nuclear factor-κB

- NG

Naringin

- NGE

Naringenin

- NLRP3

Nod-like receptor protein 3

- nNOS

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

Nitric oxide

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- OGD/R

Oxygen and glucose deprivation/reperfusion

- PERK

Protein kinase R-like ER kinase

- PI3K

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- ROS

Reactive oxygen species

- SIRT

Sirtuin

- SLC7A11

Solute carrier family 7 member 11

- SOD

Superoxide dismutase

- STING

Stimulator of interferon genes

- TBK1

TANK-binding kinase 1

- TJs

Tight junctions

- TNF

Tumor necrosis factor

- UPR

Unfolded protein response

- ZO-1

Zonula occludens 1

References

1

Ahmadi A. Shadboorestan A. (2016). Oxidative stress and cancer; the role of hesperidin, a citrus natural bioflavonoid, as a cancer chemoprotective agent. Nutr. Cancer68, 29–39. 10.1080/01635581.2015.1078822

2

Ahmadi A. Shadboorestan A. Nabavi S. F. Setzer W. N. Nabavi S. M. (2015). The role of Hesperidin in cell signal transduction pathway for the prevention or treatment of cancer. Curr. Med. Chem.22, 3462–3471. 10.2174/092986732230151019103810

3

Akondi B. R. Challa S. R. Akula A. (2011). Protective effects of rutin and naringin in testicular ischemia-reperfusion induced oxidative stress in rats. J. Reprod. Infertil.12, 209–214.

4

Amini N. B. M. Goudarzi M. (2022). A new combination of naringin and trimetazidine protect kidney mitochondria dysfunction induced by renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci.58, e19870. 10.1590/s2175-97902022e19870

5

Amini N. Sarkaki A. Dianat M. Mard S. A. Ahangarpour A. Badavi M. (2019a). Protective effects of naringin and trimetazidine on remote effect of acute renal injury on oxidative stress and myocardial injury through Nrf-2 regulation. Pharmacol. Rep.71, 1059–1066. 10.1016/j.pharep.2019.06.007

6

Amini N. Sarkaki A. Dianat M. Mard S. A. Ahangarpour A. Badavi M. (2019b). The renoprotective effects of naringin and trimetazidine on renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats through inhibition of apoptosis and downregulation of micoRNA-10a. Biomed. Pharmacother.112, 108568. 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.01.029

7

Amini N. Sarkaki A. Dianat M. Mard S. A. Ahangarpour A. Badavi M. (2021). Naringin and trimetazidine improve Baroreflex sensitivity and nucleus Tractus solitarius electrical activity in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Arq. Bras. Cardiol.117, 290–297. 10.36660/abc.20200121

8

Amini N. Maleki M. Badavi M. (2022). Nephroprotective activity of naringin against chemical-induced toxicity and renal ischemia/reperfusion injury: a review. Avicenna J. Phytomed12, 357–370. 10.22038/AJP.2022.19620

9

Araujo A. M. Cerqueira S. V. S. Menezes-Filho J. E. R. Heimfarth L. Matos K. Mota K. O. et al (2023). Naringin improves post-ischemic myocardial injury by activation of K(ATP) channels. Eur. J. Pharmacol.958, 176069. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.176069

10

Bakar E. Ulucam E. Cerkezkayabekir A. Sanal F. Inan M. (2019). Investigation of the effects of naringin on intestinal ischemia reperfusion model at the ultrastructural and biochemical level. Biomed. Pharmacother.109, 345–350. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.10.045

11

Balachandran A. Choi S. B. Beata M. M. Małgorzata J. Froemming G. R. A. Lavilla C. A. Jr. et al (2023). Antioxidant, wound healing potential and in silico assessment of naringin, eicosane and octacosane. Molecules28, 1043. 10.3390/molecules28031043

12

Baskaran G. Salvamani S. Ahmad S. A. Shaharuddin N. A. Pattiram P. D. Shukor M. Y. (2015). HMG-CoA reductase inhibitory activity and phytocomponent investigation of Basella alba leaf extract as a treatment for hypercholesterolemia. Drug Des. Devel Ther.9, 509–517. 10.2147/DDDT.S75056

13

Bibi T. Ahmad M. Mohammad Tareen N. Jabeen R. Sultana S. Zafar M. et al (2015). The endemic medicinal plants of Northern Balochistan, Pakistan and their uses in traditional medicine. J. Ethnopharmacol.173, 1–10. 10.1016/j.jep.2015.06.050

14

Burkina V. Zlabek V. Halsne R. Ropstad E. Zamaratskaia G. (2016). In vitro effects of the citrus flavonoids diosmin, naringenin and naringin on the hepatic drug-metabolizing CYP3A enzyme in human, pig, mouse and fish. Biochem. Pharmacol.110-111, 109–116. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.04.011

15

Caengprasath N. Ngamukote S. Mäkynen K. Adisakwattana S. (2013). The protective effects of pomelo extract (Citrus grandis L. Osbeck) against fructose-mediated protein oxidation and glycation. Excli J.12, 491–502.

16

Cai W. Liu L. Shi X. Liu Y. Wang J. Fang X. et al (2023). Alox15/15-HpETE aggravates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting cardiomyocyte ferroptosis. Circulation147, 1444–1460. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060257

17

Cao W. Feng S. J. Kan M. C. (2021). Naringin targets NFKB1 to alleviate oxygen-glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation-Induced injury in PC12 cells via modulating HIF-1α/AKT/mTOR-Signaling pathway. J. Mol. Neurosci.71, 101–111. 10.1007/s12031-020-01630-8

18

Cavia-Saiz M. Busto M. D. Pilar-Izquierdo M. C. Ortega N. Perez-Mateos M. Muñiz P. (2010). Antioxidant properties, radical scavenging activity and biomolecule protection capacity of flavonoid naringenin and its glycoside naringin: a comparative study. J. Sci. Food Agric.90, 1238–1244. 10.1002/jsfa.3959

19

Cerkezkayabekir A. Sanal F. Bakar E. Ulucam E. Inan M. (2017). Naringin protects viscera from ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating the nitric oxide level in a rat model. Biotech. Histochem92, 252–263. 10.1080/10520295.2017.1305499

20

Chen H. J. Chung C. P. Chiang W. Lin Y. L. (2011). Anti-inflammatory effects and chemical study of a flavonoid-enriched fraction from adlay bran. Food Chem.126, 1741–1748. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.12.074

21

Chen H. He Y. Chen S. Qi S. Shen J. (2020). Therapeutic targets of oxidative/nitrosative stress and neuroinflammation in ischemic stroke: applications for natural product efficacy with omics and systemic biology. Pharmacol. Res.158, 104877. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104877

22

Chiou G. C. Xu X. R. (2004). Effects of some natural flavonoids on retinal function recovery after ischemic insult in the rat. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 20, 107–113. 10.1089/108076804773710777

23

Cho S. C. Shaw S. Y. (2024). Comparison of the inhibition effects of naringenin and its glycosides on LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Mol. Biol. Rep.51, 56. 10.1007/s11033-023-09147-0

24

Cui Y. Zhao W. Wang X. Chen M. Zhang L. Liu Z. (2017). Protective effects of Naringin in a rat model of spinal cord ischemia–reperfusion injury. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.16, 649–656. 10.4314/tjpr.v16i3.21

25

D'Onofrio N. Servillo L. Balestrieri M. L. (2018). SIRT1 and SIRT6 signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease protection. Antioxid. Redox Signal28, 711–732. 10.1089/ars.2017.7178

26

Dai J. Li C. Y. Guan C. Yang C. Y. Wang L. Zhang Y. et al (2021). Naringenin protects ischemia-reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by nuclear factor κB. Chin. J. Nephrol.37, 739–748. 10.3760/cma.j.cn441217-20200702-00109

27

Dai P. Y. Huang J. H. Zhang K. H. Liu F. L. Wang M. Q. Zhu C. C. et al (2024). Chemical constituents from the whole herb of Euphorbia humifusa. Chin. Med. Mat.47, 1688–1693. 10.13863/j.issn1001-4454.2024.07.016

28

Dallas C. Gerbi A. Elbez Y. Caillard P. Zamaria N. Cloarec M. (2014). Clinical study to assess the efficacy and safety of a citrus polyphenolic extract of red orange, grapefruit, and orange (Sinetrol-XPur) on weight management and metabolic parameters in healthy overweight individuals. Phytother. Res.28, 212–218. 10.1002/ptr.4981

29

Danaraj J. Mariasingarayan Y. Ayyappan S. Karuppiah V. (2020). Seagrass Halodule pinifolia active constituent 4-methoxybenzioic acid (4-MBA) inhibits quorum sensing mediated virulence production of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb. Pathog.147, 104392. 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104392

30

Danis E. G. Acar G. Dasdelen D. Solmaz M. Mogulkoc R. Baltaci A. K. (2024). Naringin affects Caspase-3, IL-1β, and HIF-1α levels in experimental kidney ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Curr. Pharm. Des.30, 3339–3349. 10.2174/0113816128324562240816095551

31

de Groot H. Rauen U. (2007). Ischemia-reperfusion injury: processes in pathogenetic networks: a review. Transpl. Proc.39, 481–484. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.12.012

32

Debnath J. Gammoh N. Ryan K. M. (2023). Autophagy and autophagy-related pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.24, 560–575. 10.1038/s41580-023-00585-z

33

Din S. Hamid S. Yaseen A. Yatoo A. M. Ali S. Shamim K. et al (2022). Isolation and characterization of flavonoid naringenin and evaluation of cytotoxic and biological efficacy of water Lilly (Nymphaea mexicana Zucc.). Plants (Basel)11, 3588. 10.3390/plants11243588

34

Ding X. Zhu C. Wang W. Li M. Ma C. Gao B. (2024). SIRT1 is a regulator of autophagy: implications for the progression and treatment of myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. Pharmacol. Res.199, 106957. 10.1016/j.phrs.2023.106957

35

Dong Q. Lin X. Shen L. Feng Y. (2016). The protective effect of herbal polysaccharides on ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.92, 431–440. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.052

36

Dong Y. Toume K. Kimijima S. Zhang H. Zhu S. He Y. et al (2023). Metabolite profiling of Drynariae Rhizoma using (1)H NMR and HPLC coupled with multivariate statistical analysis. J. Nat. Med.77, 839–857. 10.1007/s11418-023-01726-6

37

Du B. Fu Q. Yang Q. Yang Y. Li R. Yang X. et al (2025). Different types of cell death and their interactions in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cell Death Discov.11, 87. 10.1038/s41420-025-02372-5

38

Duan S. Tang S. Qin N. Duan H. (2012). Chemical constituents of Phymatopteris hastate and their antioxidant activity. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi37, 1402–1407. 10.4268/cjcmm20121012

39

Ezzat M. I. Hassan M. Abdelhalim M. A. El-Desoky A. M. Mohamed S. O. Ezzat S. M. (2021). Immunomodulatory effect of Noni fruit and its isolates: insights into cell-mediated immune response and inhibition of LPS-induced THP-1 macrophage inflammation. Food Funct.12, 3170–3179. 10.1039/d0fo03402a

40

Farzana M. Hossain M. J. El-Shehawi A. M. Sikder M. A. A. Rahman M. S. Al-Mansur M. A. et al (2022). Phenolic constituents from Wendlandia tinctoria var. grandis (Roxb.) DC. Stem deciphering pharmacological potentials against oxidation, hyperglycemia, and diarrhea: phyto-pharmacological and computational approaches. Molecules27, 5957. 10.3390/molecules27185957

41

Feng J. Chen X. Lu S. Li W. Yang D. Su W. et al (2018). Naringin Attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury through inhibiting peroxynitrite-mediated mitophagy activation. Mol. Neurobiol.55, 9029–9042. 10.1007/s12035-018-1027-7

42

Feng S. Q. Zong S. Y. Liu J. X. Chen Y. Xu R. Yin X. et al (2019). VEGF antagonism attenuates cerebral Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced injury via inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated apoptosis. Biol. Pharm. Bull.42, 692–702. 10.1248/bpb.b18-00628

43

Flores-Peña R. Monroy-Ramirez H. C. Caloca-Camarena F. Arceo-Orozco S. Salto-Sevilla J. A. Galicia-Moreno M. et al (2025). Naringin and naringenin in liver health: a review of molecular and epigenetic mechanisms and emerging therapeutic strategies. Antioxidants (Basel)14, 979. 10.3390/antiox14080979

44

Fuhr U. Kummert A. L. (1995). The fate of naringin in humans: a key to grapefruit juice-drug interactions?Clin. Pharmacol. Ther.58, 365–373. 10.1016/0009-9236(95)90048-9

45

Fuhr U. Klittich K. Staib A. H. (1993). Inhibitory effect of grapefruit juice and its bitter principal, naringenin, on CYP1A2 dependent metabolism of caffeine in man. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.35, 431–436. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04162.x

46

Fukuchi M. Nakajima M. Fukai Y. Miyazaki T. Masuda N. Sohda M. et al (2004). Increased expression of c-Ski as a co-repressor in transforming growth factor-beta signaling correlates with progression of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer108, 818–824. 10.1002/ijc.11651

47

Gao M. Zhang Z. Lai K. Deng Y. Zhao C. Lu Z. et al (2022). Puerarin: a protective drug against ischemia-reperfusion injury. Front. Pharmacol.13, 927611. 10.3389/fphar.2022.927611

48

Gasparini C. Feldmann M. (2012). NF-κB as a target for modulating inflammatory responses. Curr. Pharm. Des.18, 5735–5745. 10.2174/138161212803530763

49

Gaur V. Aggarwal A. Kumar A. (2009). Protective effect of naringin against ischemic reperfusion cerebral injury: possible neurobehavioral, biochemical and cellular alterations in rat brain. Eur. J. Pharmacol.616, 147–154. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.056

50

Ghasemzadeh A. Jaafar H. Z. (2013). Profiling of phenolic compounds and their antioxidant and anticancer activities in pandan (Pandanus amaryllifolius Roxb.) extracts from different locations of Malaysia. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.13, 341. 10.1186/1472-6882-13-341

51

Ghasemzadeh A. Jaafar H. Z. Rahmat A. Devarajan T. (2014). Evaluation of Bioactive compounds, pharmaceutical quality, and anticancer activity of curry leaf (Murraya koenigii L.). Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med.2014, 873803. 10.1155/2014/873803

52

Gogna N. Hamid N. Dorai K. (2015). Metabolomic profiling of the phytomedicinal constituents of Carica papaya L. leaves and seeds by 1H NMR spectroscopy and multivariate statistical analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.115, 74–85. 10.1016/j.jpba.2015.06.035

53

Gu L. Wang F. Wang Y. Sun D. Sun Y. Tian T. et al (2023). Naringin protects against inflammation and apoptosis induced by intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury through deactivation of cGAS-STING signaling pathway. Phytother. Res.37, 3495–3507. 10.1002/ptr.7824

54