Abstract

Background:

For patients requiring extended anticoagulation therapy, clinicians often prescribe reduced-dose direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) rather than full-dose, which may be related to concerns about the higher bleeding risk associated with full-dose DOACs, despite potentially better efficacy in preventing VTE recurrence. This meta-analysis aims to evaluate the net clinical benefit of reduced-dose DOACs versus full-dose DOACs in extended anticoagulation therapy.

Methods:

This study has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO identifier: CRD420251089110). A systematic search was conducted in the PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases from their inception to 30 June 2025. Data extraction was done independently and in duplicate. A random-effects meta-analysis model was used to report the pooled treatment effects and 95% confidence intervals.

Results:

A total of 5 randomized clinical trials were included (8,781 cases). Compared with full-dose DOAC, reduced-dose DOAC did not significantly increase the risk of recurrent VTE or death [(RR, 0.94 (95% CI, 0.68–1.29)), (RR, 0.84 (95% CI, 0.65–1.09))], but significantly reduced the risk of major bleeding/CRNMB (RR, 0.71 (95% CI, 0.61–0.82)). In the analysis of DOAC drugs, the prospective estimates for recurrent VTE were as follows: apixaban, RR, 0.93 (95% CI, 0.63–1.37); rivaroxaban, RR 0.96 (95% CI, 0.54–1.69). The prospective estimates for major bleeding/CRNMB were as follows: apixaban, RR, 0.74 (95% CI, 0.63–0.89); rivaroxaban, RR, 0.63 (95% CI, 0.48–0.84). Most findings were consistent within subgroups.

Conclusion:

Reduced-dose DOACs were associated with a significant decrease in the risk of major bleeding/CRNMB compared with full-dose DOACs, but were not associated with a significant increase in the risk of recurrent VTE. These findings support the net clinical benefit of reduced-dose DOACs compared with full-dose DOACs and reinforce adherence with current VTE guidelines.

Systematic Review Registration:

Identifier CRD420251089110.

1 Introduction

Reduced-dose direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are commonly used in clinical practice for extended anticoagulation therapy, which helps prevent recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) and reduces bleeding (Stevens et al., 2021; Ortel et al., 2020). However, the net clinical benefit of reduced-dose DOACs compared to full-dose treatment in high-risk VTE patients, such as those with cancer, is not well-defined (Ghorbanzadeh et al., 2025). In these situations, any potential advantages of reduced-dose DOACs must be carefully balanced against the potential increase in recurrent VTE risk.

Whether recurrent VTE and bleeding risk differs between reduced-dose and full-dose DOACs remains unclear. An analysis of the AMPLIFY-EXT (reduced-dose and full-dose apixaban versus placebo for extended treatment of VTE) trial showed no difference between reduced-dose and full-dose apixaban in the prevention of recurrent VTE and even a lower risk of bleeding in extended VTE treatment. However only 15% of the patients were over 75 years old, and few had a weight below 60 kg or moderate to severe renal impairment (Agnelli et al., 2013). Previous meta-analyses have likewise suggested that reduced-dose DOACs may be an attractive option for extended phase anticoagulation after VTE, but the results are not generalizable to groups that were not included or were under-represented in the trials (Vasanthamohan et al., 2018). Clinicians continue to face a difficult challenge in accurately balancing the risks versus benefits of reduced-dose and full-dose DOACs in different populations.

Multiple randomized controlled trials comparing reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs have recently been completed (McBane et al., 2024; Couturaud et al., 2025; Mahé et al., 2025). By combining events from these and earlier studies, we could estimate the risks of recurrent VTE and bleeding more precisely while possessing sufficient power to analyze key subgroups. We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the effects of reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs on the risks of recurrent VTE and bleeding during extended anticoagulation therapy.

2 Methods

Our research was reported in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2021). This study has been registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO identifier: CRD420251089110).

2.1 Data sources and search strategy

We identified relevant studies through a systematic literature search in Embase, PubMed, and Web of Science from database inception to 30 June 2025. The searches was not limited by language. We employed a search strategy that combined keywords and MeSH terms related to DOACs and VTE (Supplementary Methods). We also searched the reference lists of included studies and relevant review articles.

2.2 Data extraction

We included randomized controlled trials of patients aged 18 years or older with VTE who required extended anticoagulation therapy for at least 6 months, and reported outcomes of recurrent VTE and bleeding events in patients receiving reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs. Two researchers independently screened each title and abstract according to inclusion and exclusion criteria, with a third researcher conducting further analysis in case of disagreement. Following this screening process, each reviewer assessed the eligibility of full-text articles. We extracted the following data: study characteristics, baseline demographic data of participants, descriptions of the intervention (reduced-dose DOAC) and comparator (full-dose DOAC).

2.3 Study outcomes

Our primary outcomes were recurrent VTE and major bleeding/CRNMB. Other outcomes included death from any cause. For major bleeding, we used the definition from the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, which stipulates one or more of the following: fatal bleeding, symptomatic bleeding in a critical area or organ, or bleeding causing a decrease in hemoglobin level of 20 g/L or more or leading to transfusion of 2 or more units of whole blood or red blood cells (Schulman et al., 2010). We used the Cochrane Collaboration criteria to determine the risk of bias for each included study (Higgins et al., 2011). We then used the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) tool to assess the reporting quality of the primary study results (Guyatt et al., 2011).

2.4 Statistical analysis

We conducted meta-analyses separately for each type of DOACs. For each of the meta-analysis, the Mantel-Haenszel method using a random-effects model was employed to calculate the pooled relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). The I2 statistic was used to assess heterogeneity among studies, and a value greater than 50% indicates the presence of substantial heterogeneity (Cochrane, 2024). We conducted post hoc subgroup analyses for sex, age, BMI, renal impairment, index VTE, and cancer to explore subgroups that require dose reduction. For these analyses, we performed interaction tests to evaluate possible subgroup effects.

In the RENOVE (high risk of recurrent VTE) trial, patients in the DOACs group received treatment with apixaban or rivaroxaban. Since the proportions of the two were similar, we included them separately in the apixaban and rivaroxaban trial analyses. To assess the stability of the study, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a fixed-effects model instead of a random-effects model.

Risk of bias assessment was performed using RevMan (Version 5.1, Copenhagen: Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011) software. Data analysis was conducted using R version 4.5.1 software with the package meta. Summary tables related to GRADE were constructed using GRADEpro (Version 3.6. Copyright © 2004–2009 GRADE Working Group). Analyses were 2-tailed, with statistical significance set at a 2-sided P value less than 0.05.

3 Result

Through database searching, we identified 1,388 unique citations (Supplementary Figure 1), of which 5 met eligibility criteria (Table 1). Included trials studied patients with extended VTE treatment (VTE, 2 trials (Agnelli et al., 2013; Weitz et al., 2017); cancer-related VTE, 2 trials (McBane et al., 2024; Mahé et al., 2025); high-risk VTE, 1 trial (Couturaud et al., 2025)).

TABLE 1

| Study, year (Reference) | Trial | Participants, n | Average age, y |

Male sex, % | Population | Intervention | Comparator | Follow-up, mo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agnelli et al. (2013) | AMPLIFY-EXT | 1,653 | 56.5 | 956 (57.8) | VTE | Apixaban 2.5 mg bid | Apixaban 5 mg bid | 12 |

| Weitz et al. (2017) | EINSTEIN CHOICE | 2,234 | 58.4 | 1,222 (54.7) | VTE | Rivaroxaban 10 mg qd | Rivaroxaban 20 mg qd | 12 |

| McBane et al. (2024) | EVE | 360 | 64.0 | 161 (44.7) | Cancer-related VTE | Apixaban 2.5 mg bid | Apixaban 5 mg bid | 12 |

| Couturaud et al. (2025) | RENOVE | 2,768 | 62.7 | 1797 (64.9) | High risk of recurrent VTE | Apixaban 2.5 mg bid; Rivaroxaban 10 mg qd | Apixaban 5 mg bid; Rivaroxaban 20 mg qd | 37.1 |

| Mahé et al. (2025) | API-CAT | 1,766 | 67.5 | 766 (43.4) | Cancer-related VTE | Apixaban 2.5 mg bid | Apixaban 5 mg bid | 12 |

Trial characteristics.

DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; mo, month; n, number; y, year; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Among the 8,781 participants, the average age across the 5 trials was 61.82 years, and trial male population were 55.8% on average. The mean follow-up time across trials was 17 months. All trials reported on study outcomes during the entire follow-up duration, and all reported on the main outcomes of recurrent thromboembolism and major bleeding/CRNMB. Major bleeding was defined per International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis criteria for 5 trials.

For the reduced-dose DOACs group, trials used apixaban (2.5 mg twice daily, 4 trials), rivaroxaban (10 mg once daily, 2 trials). For the full-dose DOACs group, trials used apixaban (5 mg twice daily, 4 trials) and rivaroxaban (20 mg once daily, 2 trials). Overall, the risk of bias in the included studies was low (Supplementary Figure 2). Table 2 summarizes our review findings.

TABLE 2

| Outcome (study type) | No of patients | Effect | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced-dose DOACs | Full-dose DOACs | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | ||

| Recurrent VTE (five RCTs) | 73/4,261 (1.7%) | 78/4,249 (1.8%) | RR 0.94 (0.68–1.29) | 1 fewer per 1,000 (from 6 fewer to 5 more) | MODERATEa |

| Recurrent VTE - apixaban (four RCTs) | 48/2,460 (2%) | 52/2,459 (2.1%) | RR 0.93 (0.63–1.37) | 1 fewer per 1,000 (from 8 fewer to 8 more) | MODERATEa |

| Recurrent VTE - rivaroxaban (two RCTs) | 25/1801 (1.4%) | 26/1790 (1.5%) | RR 0.96 (0.54–1.69) | 1 fewer per 1,000 (from 7 fewer to 10 more) | MODERATEa |

| Major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding (five RCTs) | 268/4,266 (6.3%) | 383/4,269 (9%) | RR 0.71 (0.61–0.82) | 26 fewer per 1,000 (from 16 fewer to 35 fewer) | HIGH |

| Major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding - apixaban (four RCTs) | 193/2,465 (7.8%) | 263/2,468 (10.7%) | RR 0.74 (0.63–0.89) | 28 fewer per 1,000 (from 12 fewer to 39 fewer) | HIGH |

| Major or clinically relevant non-major bleeding - rivaroxaban (two RCTs) | 75/1,801 (4.2%) | 120/1801 (6.7%) | RR 0.63 (0.48–0.84) | 25 fewer per 1,000 (from 11 fewer to 35 fewer) | HIGH |

| Death (four RCTs) | 209/3,555 (5.9%) | 251/3,573 (7%) | RR 0.84 (0.65–1.09) | 11 fewer per 1,000 (from 25 fewer to 6 more) | MODERATEb |

Summary of review findings for RCTs comparing reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs.

Cl, confidence interval; DOACs, direct oral anticoagulants; GRADE, grading of recommendation assessment development and evaluation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Low sample sizes and wide confidence intervals.

Wide confidence intervals.

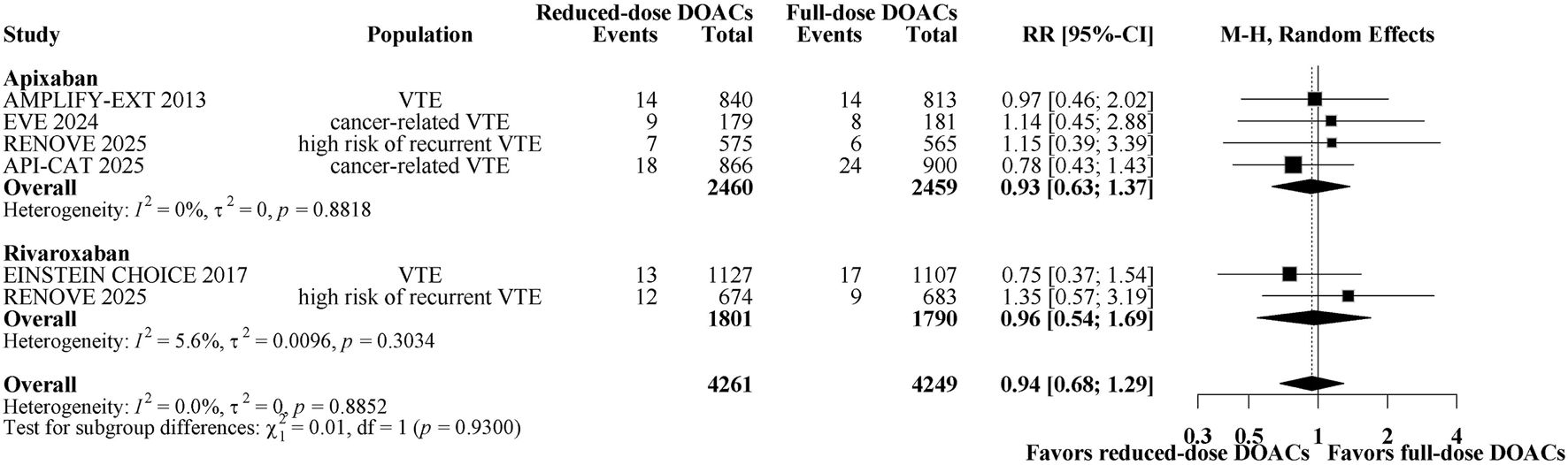

3.1 Recurrent VTE

A total of 151 patients (1.78%) had recurrent VTE. Figure 1 shows a forest plot of trials comparing reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs on risk for recurrent VTE. Reduced-dose DOACs was not associated with significantly higher risks of recurrent VTE compared with full-dose DOACs (1.7% vs 1.8%; RR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.68–1.29). There was no heterogeneity among DOACs agents (overall I2 = 0%). In the analysis by DOACs agent, the respective estimates for recurrent VTE risk were as follows: apixaban, RR, 0.93 (95% CI, 0.63–1.37); rivaroxaban, RR, 0.96 (95% CI, 0.54–1.69). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the results remain unchanged when using a fixed-effect model (Supplementary Figure 5A). The quality of evidence was moderate for the comparison between reduced-dose and full-dose DOACs, also being graded down because of imprecision (Table 2).

FIGURE 1

Forest plot of randomized controlled trials comparing reduced-dose DOACs vs. full-dose DOACs for risk for Recurrent VTE.

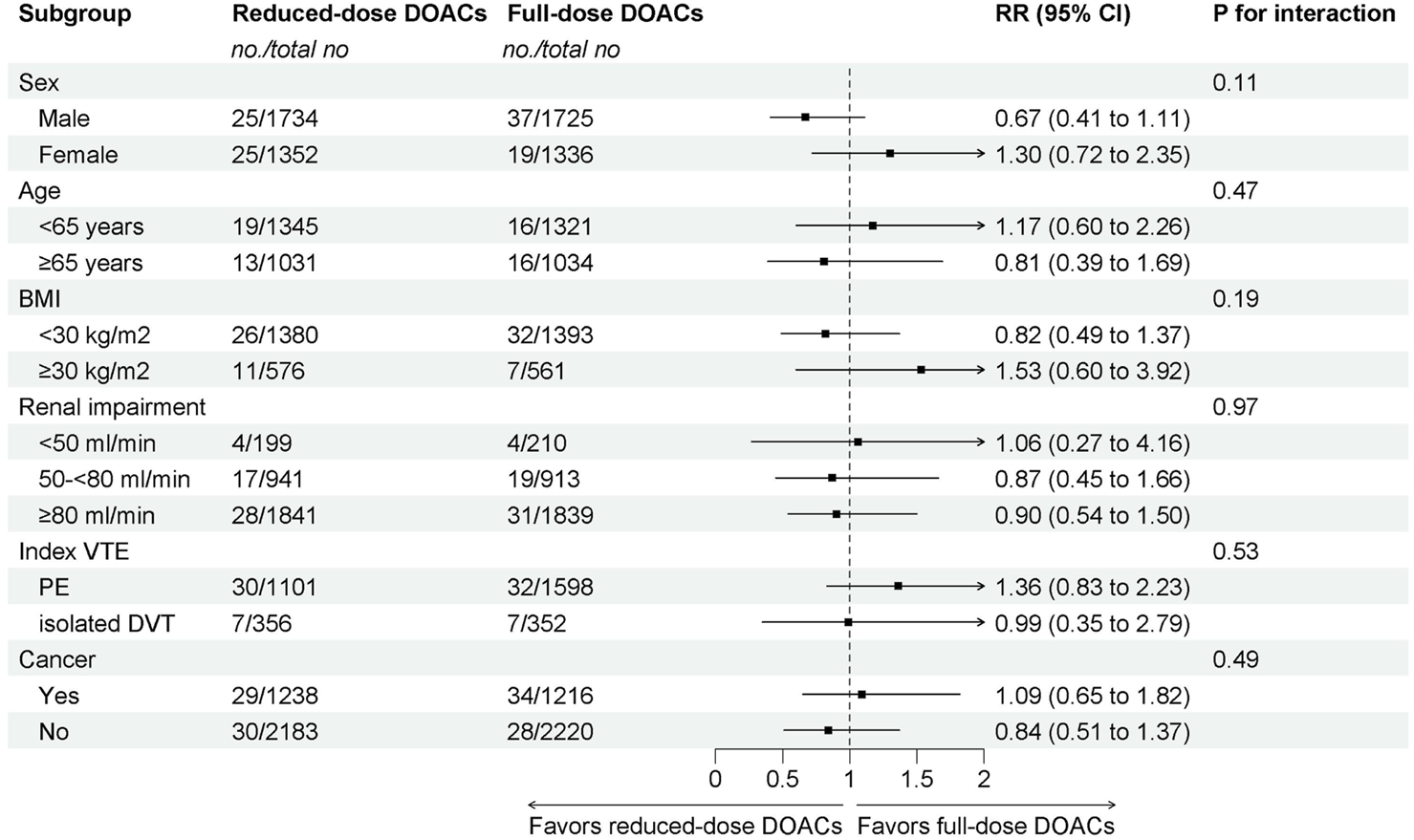

The subgroup analyses demonstrated that reduced-dose DOACs did not significantly increase the risk of recurrent VTE compared to full-dose DOACs, regardless of sex, age, BMI, renal function, VTE type, or cancer. Test for subgroup differences indicated that there was no statistically significant subgroup effect (p = 0.11 for sex, p = 0.47 for age, p = 0.19 for BMI, p = 0.97 for renal impairment, p = 0.53 for index VTE, p = 0.49 for cancer). These results indicate that sex, age, BMI, renal function, VTE type, or cancer, as included in the trials, did not modify the effect of reduced-dose DOACs in comparison to full-dose DOACs on the risks of recurrent VTE (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2

Subgroup analysis of Recurrent VTE.

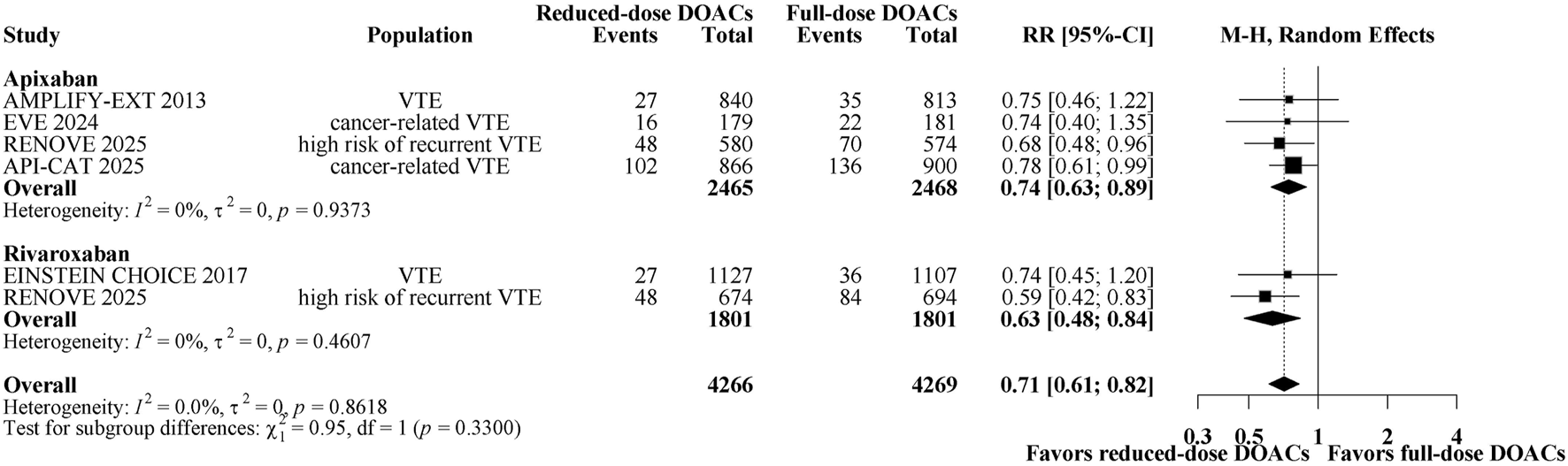

3.2 Major bleeding/CRNMB

A total of 651 patients (7.63%) had major bleeding/CRNMB. Figure 3 shows a forest plot of comparing reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs on risk for major bleeding/CRNMB. Reduced-dose DOACs was associated with significantly lower risk of major bleeding/CRNMB compared with full-dose DOACs (6.3% vs 9%; RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.61–0.82). There was no heterogeneity among DOACs (overall I2 = 0%). In the analysis by DOAC agents, the respective estimates for major bleeding/CRNMB risk were as follows: apixaban, RR, 0.74 (95% CI, 0.63–0.89); rivaroxaban, RR 0.63 (95% CI, 0.48–0.84). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the results remain unchanged when using a fixed-effect model (Supplementary Figure 5B). The quality of evidence was high for the comparison between reduced-dose and full-dose DOACs (Table 2). Major and CRNMB bleeding events were reported separately (Supplementary Figures S4, S5). Reduced-dose DOACs was associated with significantly lower risks of major bleeding or CRNMB compared with full-dose DOACs [(RR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.41–0.88), (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63–0.88)].

FIGURE 3

Forest plot of randomized controlled trials comparing reduced-dose DOACs vs. full-dose DOACs for risk for Major bleeding/CRNMB.

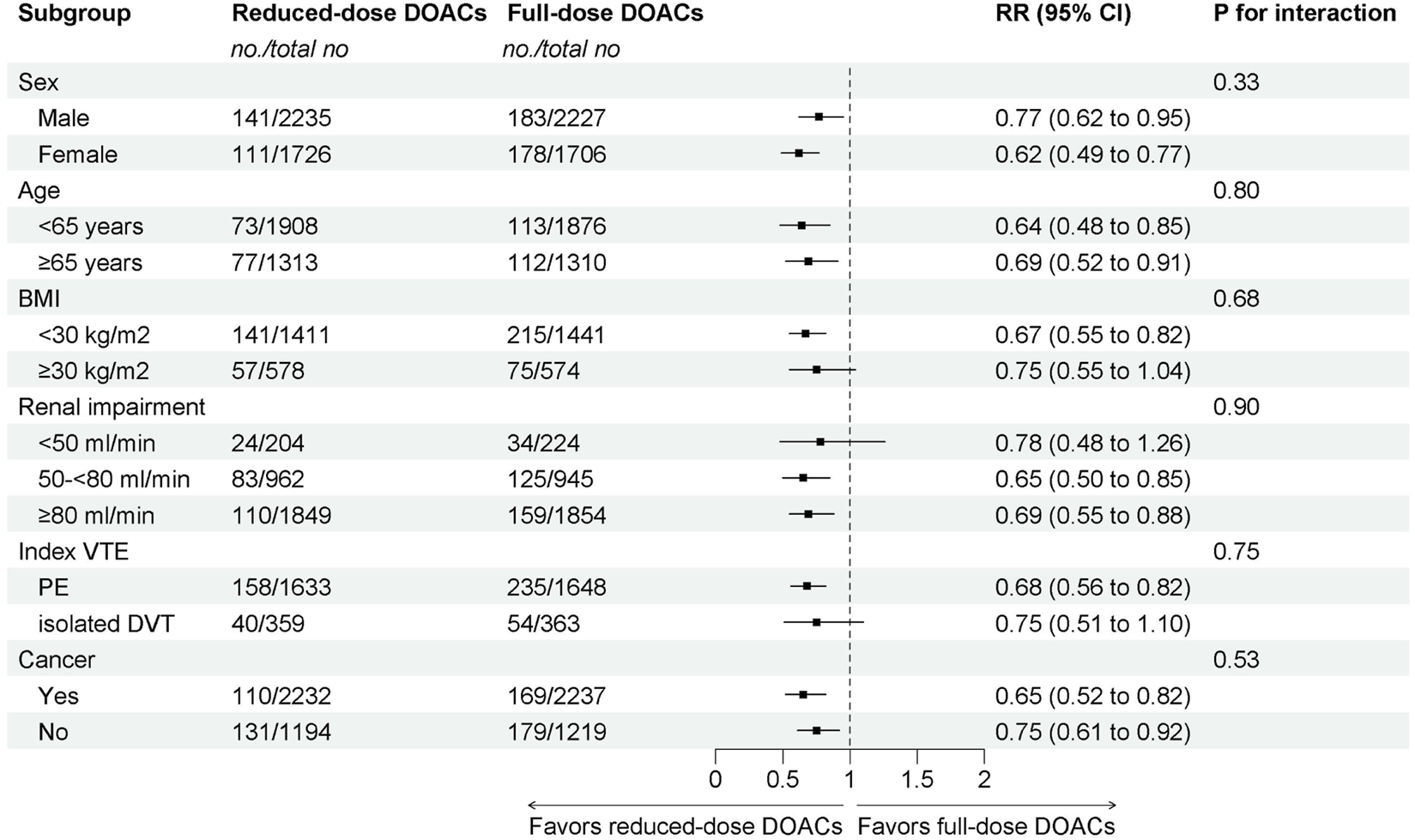

The subgroup analyses demonstrated that reduced-dose DOACs did significantly decrease the risk of Major bleeding/CRNMB compared to full-dose DOACs, regardless of sex, age, BMI, renal function, VTE type, or cancer. Test for subgroup differences indicated that there was no statistically significant subgroup effect (p = 0.33 for sex, p = 0.80 for age, p = 0.68 for BMI, p = 0.90 for renal impairment, p = 0.75 for index VTE, p = 0.53 for cancer). These results indicate that sex, age, BMI, renal function, VTE type, or cancer, as included in the trials, did not modify the effect of reduced-dose DOACs in comparison to full-dose DOACs on the risks of Major bleeding/CRNMB (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4

Subgroup analysis of Major bleeding/CRNMB.

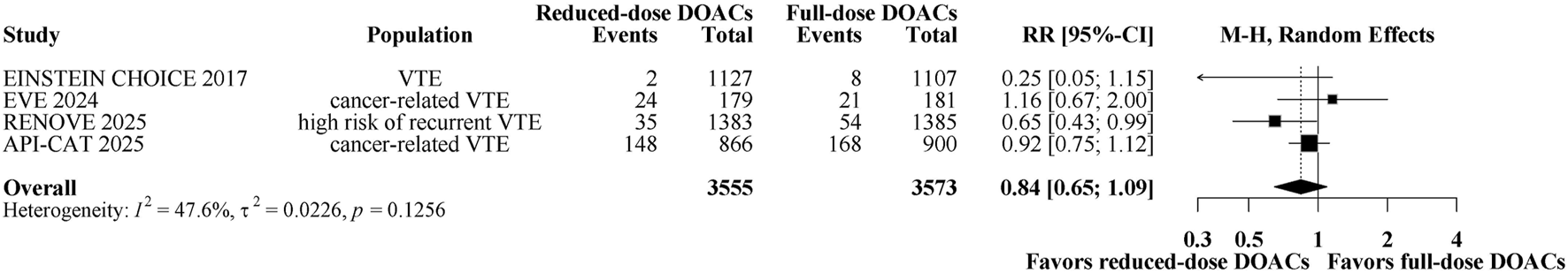

3.3 Other results

A total of 460 patients (6.45%) had death. Figure 5 shows a forest plot of comparing reduced-dose versus full-dose DOACs on risk for death. Reduced-dose DOACs was not associated with significantly higher risks of death compared with full-dose DOACs (5.9% vs 7%; RR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.65–1.09). There was no heterogeneity among studies (overall I2 = 47.65%). Sensitivity analysis indicated that the results remain unchanged when using the fixed-effect model (Supplementary Figure 5C). The quality of evidence was moderate for the comparison between reduced-dose and full-dose DOACs, also being graded down because of imprecision (Table 2).

FIGURE 5

Forest plot of randomized controlled trials comparing reduced-dose DOACs vs. full-dose DOACs for risk for death.

4 Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing reduced-dose with full-dose DOACs for the treatment of extended VTE (5 trials included for the primary outcome; 8,781 participants). We found no significant increase in risk of recurrent VTE, but significant decrease in risk of major bleeding/CRNMB. Additionally, our exploration of heterogeneity among trials suggested consistent effects by agent. Our subgroups results suggest a decreased risks of major bleeding/CRNMB, in patients taking reduced-dose DOACs compared to full-dose DOACs, regardless of sex, age, BMI, renal impairment, index VTE, and cancer.

These findings provide pooled estimates from high-quality studies to guide clinical decision-making. For patients requiring extended VTE therapy, there is currently insufficient strong evidence demonstrating that reduced-dose anticoagulation is superior to full-dose anticoagulation, resulting in some guidelines being unable to provide strong recommendations. Our results expand the existing knowledge on this topic by providing pooled estimates from five RCTs that increased statistical power and by providing subgroup-specific analyses. None of the tests for subgroup differences was statistically significant to indicate effect modification in such a way that reassures about the safety of reduced-dose DOACs for patients with extended VTE treatment. The difference in point estimates for major bleeding/CRNMB events among renal impairment could suggest an effect modification, such that even high risks of major bleeding/CRNMB events are observed for GFR <50 mL/min who receive reduced-dose DOACs compared to GFR ≥50–80 and ≥80 mL/min (RR: 0.65 vs 0.69 vs 0.78). Nonetheless, patients of both renal impairment manifested decreased risks of major bleeding/CRNMB on reduced-dose DOACs compared to full-dose DOACs.

Sex and age did not affect the superior safety profile of reduced-dose direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) compared to the full-dose regimen, whereas the optimal dosing for other patient populations, such as those with cancer, obesity, renal impairment or isolated DVT, remains contested. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolism requires further prospective studies to determine whether it is beneficial to reduce the dose of DOACs during extended anticoagulation therapy. The EVE and API-CAT trials recently demonstrated that reduced-dose DOACs have more net clinical benefits than full-dose DOACs (McBane et al., 2024; Mahé et al., 2025). To further investigate this in the context of cancer, we performed a subgroup analysis incorporating data from the RENOVE trial, which specifically included high-risk patients with cancer-associated VTE (Couturaud et al., 2025). Our findings demonstrate that reduced-dose DOACs are indeed safer for managing cancer-related VTE.

Currently, there is still a lack of evidence regarding the applicability of reduced-dose DOACs in the extended VTE treatment of obese patients (Martin et al., 2021; Rosovsky et al., 2023). The previous EINSTEIN CHOICE and AMPLIFY EXTENSION trials had different weight groupings, making it impossible to conduct a meta-analysis to provide evidence-based guidance (Agnelli et al., 2013; Weitz et al., 2017). Therefore, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on BMI. The results showed that reduced-dose DOACs are suitable not only for patients with BMI <30 kg/m2 but also for those with BMI ≥30 kg/m2, thus filling this clinical gap. The routine use of reduced-dose DOACs provides greater protection for VTE patients with moderate to severe renal impairment, especially apixaban (Knueppel et al., 2022). However, the advantages of reduced-dose DOACs in the extended treatment of VTE associated with renal impairment remain insufficiently established. Our subgroup analysis based on renal impairment revealed that for patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <50 mL/min, reduced-dose DOACs are safer than full-dose DOACs. However, no significant difference was observed between full-dose and reduced-dose DOACs in patients with an eGFR ≥50 mL/min. This suggests that reduced-dose DOACs may offer additional advantages in the extended management of VTE associated with renal impairment.

Similarly, we conducted a subgroup analysis based on VTE classification for patients with independent DVT. The results showed no significant difference in recurrent VTE or massive bleeding/CRNMB events between DOACs with reduced and full doses. This indicates that reduced-dose DOACs can be used for extended therapy in patients with independent DVT. Through our subgroup analyses, we have further identified populations requiring reduced-dose DOACs during extended VTE treatment, such as those with cancer, obesity, renal impairment, and isolated DVT. However, more research is needed to refine dosing strategies for these specific groups.

This study has several limitations. First, our findings were imprecise due to the low incidence of certain outcomes and wide confidence intervals, especially for recurrent VTE. Second, there are differences in the enrolled populations across different trials (e.g., cancer patients and those with high-risk recurrent VTE). Although the absolute risk of bleeding events may vary by population, the absolute risk estimates of treatment effects are expected to be consistent across populations. Third, we did not find studies comparing doses of dabigatran and edoxaban, and it is unclear whether our results can be extrapolated to these scenarios. Fourth, given that only a few studies were identified for each comparison of reduced-dose DOACs versus full-dose DOACs, we did not create funnel plots to assess publication bias due to the increased risk for potential error (Sterne et al., 2011). This meta-analysis expands on previous work by including 5 large randomized trials and provides the most up-to-date synthesis of evidence synthesis to address this clinical question.

In summary, this study provides crucial evidence-based support for extended VTE therapy, demonstrating that reduced-dose DOACs significantly lowers the risk of major bleeding while maintaining anticoagulation efficacy. The consistent benefit-risk advantage demonstrated across key patient subgroups, including variations in sex, age, cancer, obesity, renal impairment, and isolated DVT, lays a robust foundation for treatment personalization. However, prospective studies are warranted to refine precise dosing strategies in these subgroups, to address the current evidence gaps for dabigatran and edoxaban, and to optimize the overall anticoagulation management strategy.

5 Conclusion

In conclusion, this meta-analysis founds that reduced-dose DOACs significantly lowered the risk of major bleeding/CRNMB compared to full-dose DOACs, with no significant change in the risk of recurrent VTE. Subgroup analyses based on sex, age, weight, renal impairment, type of VTE, and cancer did not show evidence of effect modification. This provides definitive evidence that reduced-dose DOACs should be considered the preferred strategy for most patients requiring extended VTE anticoagulation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

RZ: Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Supervision, Data curation. RW: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Writing – original draft. YL: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Formal Analysis. WT: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Formal Analysis, Data curation. DN: Writing – review and editing, Data curation, Supervision. WC: Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review and editing. XN: Writing – original draft, Formal Analysis, Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – review and editing, Supervision.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by grants from Heze Municipal Hospital Young Scientific and Technological Talents Program, 2025QN03.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1708316/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Agnelli G. Buller H. R. Cohen A. Curto M. Gallus A. S. Johnson M. et al (2013). Apixaban for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med.368 (8), 699–708. 10.1056/NEJMoa1207541

2

Cochrane (2024). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions, version 6.5. Available online at: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (Accessed October 30, 2025).

3

Couturaud F. Schmidt J. Sanchez O. Ballerie A. Sevestre M. A. Meneveau N. et al (2025). Extended treatment of venous thromboembolism with reduced-dose versus full-dose direct oral anticoagulants in patients at high risk of recurrence: a non-inferiority, multicentre, randomised, open-label, blinded endpoint trial. Lancet405 (10480), 725–735. 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02842-3

4

Ghorbanzadeh A. Porres-Aguilar M. McBane R. Gerotziafas G. Tafur A. (2025). Extended anticoagulation in patients with cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. Pol. Arch. Intern Med.135 (6), 17025. 10.20452/pamw.17025

5

Guyatt G. Oxman A. D. Akl E. A. Kunz R. Vist G. Brozek J. et al (2011). GRADE guidelines: 1. Introduction-GRADE evidence profiles and summary of findings tables. J. Clin. Epidemiol.64 (4), 383–394. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.026

6

Higgins J. P. Altman D. G. Gøtzsche P. C. Jüni P. Moher D. Oxman A. D. et al (2011). The cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ343, d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928

7

Knueppel P. Bang S. H. Troyer C. Barriga A. Shin J. Cadiz C. L. et al (2022). Evaluation of standard versus reduced dose apixaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe renal disease (ESRD-VTE). Thromb. Res.220, 91–96. 10.1016/j.thromres.2022.10.014

8

Mahé I. Carrier M. Mayeur D. Chidiac J. Vicaut E. Falvo N. et al (2025). Extended reduced-dose apixaban for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med.392 (14), 1363–1373. 10.1056/NEJMoa2416112

9

Martin K. A. Beyer-Westendorf J. Davidson B. L. Huisman M. V. Sandset P. M. Moll S. (2021). Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with obesity for treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism: updated communication from the ISTH SSC subcommittee on control of anticoagulation. J. Thromb. Haemost.19 (8), 1874–1882. 10.1111/jth.15358

10

McBane R. D. 2nd Loprinzi C. L. Zemla T. Tafur A. Sanfilippo K. Liu J. J. et al (2024). Extending venous thromboembolism secondary prevention with apixaban in cancer patients. The EVE trial. J. Thromb. Haemost.22 (6), 1704–1714. 10.1016/j.jtha.2024.03.011

11

Ortel T. L. Neumann I. Ageno W. Beyth R. Clark N. P. Cuker A. et al (2020). American society of hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv.4 (19), 4693–4738. 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001830

12

Page M. J. McKenzie J. E. Bossuyt P. M. Boutron I. Hoffmann T. C. Mulrow C. D. et al (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71

13

Rosovsky R. P. Kline-Rogers E. Lake L. Minichiello T. Piazza G. Ragheb B. et al (2023). Direct oral anticoagulants in Obese patients with venous thromboembolism: results of an expert consensus panel. Am. J. Med.136 (6), 523–533. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.01.010

14

Schulman S. Angerås U. Bergqvist D. Eriksson B. Lassen M. R. Fisher W. et al (2010). Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in surgical patients. J. Thromb. Haemost.8 (1), 202–204. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03678.x

15

Sterne J. A. C. Sutton A. J. Ioannidis J. P. A. Terrin N. Jones D. R. Lau J. et al (2011). Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in Meta analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ343, d4002. 10.1136/bmj.d4002

16

Stevens S. M. Woller S. C. Kreuziger L. B. Bounameaux H. Doerschug K. Geersing G. J. et al (2021). Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: Second update of the CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest160 (6), e545–e608. 10.1016/j.chest.2021.07.055

17

Vasanthamohan L. Boonyawat K. Chai-Adisaksopha C. Crowther M. (2018). Reduced-dose direct oral anticoagulants in the extended treatment of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost.16 (7), 1288–1295. 10.1111/jth.14156

18

Weitz J. I. Lensing A. W. A. Prins M. H. Bauersachs R. Beyer-Westendorf J. Bounameaux H. et al (2017). Rivaroxaban or aspirin for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism. N. Engl. J. Med.376 (13), 1211–1222. 10.1056/NEJMoa1700518

Summary

Keywords

dose, direct oral anticoagulants, venous thromboembolism, extended treatment, randomized controlled trials

Citation

Zhang R, Wang R, Li Y, Tian W, Niu D, Cheng W and Niu X (2025) Full-dose versus reduced-dose comparison of direct oral anticoagulants for extended treatment of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1708316. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1708316

Received

19 September 2025

Revised

01 November 2025

Accepted

20 November 2025

Published

04 December 2025

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Lukasz Pyka, Silesian Center for Heart Disease, Poland

Reviewed by

Omar A. Almohammed, King Saud University, Saudi Arabia

Danielle Vlazny, Mayo Clinic, United States

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Zhang, Wang, Li, Tian, Niu, Cheng and Niu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaofang Niu, nxf819@126.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.