Abstract

Aim:

This is a retrospective cohort study aimed to investigate the association of adverse drug related (ADR)-related hospital admissions with adverse clinical outcomes, including in-hospital mortality, length of stay (LOS), and hospital readmission among older adults with diabetes.

Methods:

All individuals aged 65 years and older with diabetes who were admitted to the three major public hospitals in Tasmania, Australia, between July 2017 and December 2023 were identified using International Classification of Diseases codes. Patients with at least one ADR-related hospital admission were propensity score matched with and those without ADR-related admissions based on age, sex, year of index admission, diagnosis-related groups, socioeconomic status, and comorbidities. Adjusted logistic regression was used to assess in-hospital mortality. Length of stay was analysed using a generalised linear model with a Gamma distribution, and readmission risk at 30, 60, and 90 days was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models.

Results:

After matching, a total of 5,038 older patients with diabetes were included in the in-hospital mortality analysis, and 4,674 were included in the LOS and readmission analyses. Patients with ADR-related hospitalisations had a significantly higher risk of in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio = 1.31; 95% CI: 1.03–1.66; p < 0.05), longer LOS (adjusted ratio = 1.24 (1.13–1.37); p < 0.001, and a greater risk of readmission (the highest adjusted hazard ratio was at 60 days = 1.29 (1.14–1.45); p < 0.001) compared to those without ADR-related hospital admissions.

Conclusion:

ADR-related hospital admissions were associated with poorer clinical outcomes in older adults with diabetes, including greater mortality, prolonged hospital stays, and increased risk of readmission. These findings underscore the importance of early ADR detection, structured medication review, ongoing monitoring, and patient-centered education to improve medication safety and optimise outcomes in this high-risk group.

1 Introduction

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are a persistent challenge to patient safety worldwide and represent a major contributor to morbidity and mortality (Le Louët and Pitts, 2023). A systematic review involving approximately 1.57 million patients reported that ADRs occurred in 8.32% (95% CI, 7.82, 8.83) of primary care patients during the observation periods of the included studies, with over 20% of these ADRs considered preventable (Insani et al., 2021). A previous systematic review in older adults reported that 3.3%–23.1% of all hospital admissions were attributable to ADRs (Cosgrave et al., 2025). These events represent a significant subset of medication-related problems with substantial implications for healthcare systems.

In Australia, an estimated 250,000 medication-related events result in hospital admissions annually, imposing an economic burden of around A$1.4 billion on the healthcare system (Lim et al., 2022). Reported rates of hospital admissions attributable to ADRs vary widely, ranging from 0.16% to 23.1% of total admissions (Kongkaew et al., 2008; Oscanoa et al., 2017; Howard et al., 2007). This variation reflects differences in study design, population characteristics, and healthcare settings. Risk factors commonly associated with ADRs include advanced age, with age-related physiological changes (e.g., impaired renal function), and polypharmacy (Cahir et al., 2023; Cheong et al., 2020; Pont et al., 2014; Yadesa et al., 2021).

Older adults with diabetes are particularly susceptible to ADRs due to multiple compounding factors. These include the chronic medical complications of diabetes and resultant co-morbidities (Chinmayee et al., 2024; Lu et al., 2023), often necessitating complex medication regimens (Remelli et al., 2022; Sinclair and Abdelhafiz, 2022; Umegaki, 2024). The elevated risk is also partly attributed to diabetes-related physiological changes, such as altered gastric emptying time that can affect drug absorption, and nephropathy, that can impair drug elimination (Dostalek et al., 2012).

Additionally, Australian studies have reported that patients with diabetes who are admitted to hospital for any reason are more likely to have poor clinical outcomes and increased hospital costs, compared to patients without diabetes (Gao et al., 2021; Karahalios et al., 2018). Despite this, evidence regarding the clinical impact of ADR-related hospital admissions in older adults with diabetes remains scarce. Previous studies have examined ADRs in general populations or in other specific conditions, such as dementia (Patel and Patel, 2018; Zaidi et al., 2021; Walter et al., 2017), but none, to our knowledge, have specifically evaluated mortality, length of stay (LOS), and readmission outcomes in older adults with diabetes who experience ADR-related admissions. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the association between ADR-related hospital admissions and key clinical outcomes, such as in-hospital mortality, LOS, and hospital readmission, among older adults with diabetes.

2 Methods

2.1 Data source

We conducted a retrospective, population-based cohort study using an administrative dataset routinely collected and reported for patients admitted to hospitals in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). The data set, Admitted Patient Care Australian National Minimum Data Set (APC-NMDS), captures summarised information on all hospital admissions. This incorporates patients’ demographics, admission characteristics, and both principal and additional diagnoses in accordance with the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th edition, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM). Details about the dataset and the data preparation process have been previously described (Vonna et al., 2025).

2.2 Study population

Firstly, older patients (aged 65 years and older) who were admitted to the three major public hospitals in Tasmania, Australia from July 2017 to December 2023 were identified. Eligible patients were Tasmanian residents with at least one overnight hospital stay. The presence of diabetes was identified using ICD-10-AM codes E10–14, flagged as either a principal or secondary diagnosis, and encompassing both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Patients were divided into two groups based on whether they had any ADR-related hospital admissions, considering both primary and secondary diagnoses. Similar to other studies (Walter et al., 2017; Du et al., 2017), we identified patients with ADR-related hospital admissions using the ICD-10-AM external cause codes between Y40-Y59 or ADR-related diagnosis codes (A1 and A2). The index admission was defined as the first ADR-related hospital admission during the study period for patients who experienced at least one ADR-related admission, or the earliest hospital admission during the study period for those without any ADR-related admission. Demographic and clinical characteristics, as well as in-hospital mortality and LOS, were obtained from this index admission. Readmission analyses were conducted based on outcomes following discharge from the index admission.

2.3 Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, year of index admission, socioeconomic status (SES), hospital, Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG), Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score and mode of admission (acute and non-acute). SES was assessed using one of the components of Socioeconomic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), which is the Index of Relative Socioeconomic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD). Based on the 2016 ABS census data, IRSAD ranks residential postcodes from 1 (most disadvantaged) to 10 (most advantaged) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2025). Patients in the lower half of the IRSAD scale (deciles 1–3) were classified as having disadvantaged SES, while those in the upper half of the IRSAD scale (deciles 4–10) were assigned to advantaged SES. The CCI score was calculated using the method described by Quan et al. (Vonna et al., 2025), modified to exclude age and diabetes since all patients were older adults diagnosed with diabetes. The AR-DRG system classifies inpatient admissions based on principal and secondary diagnoses, procedures, patient demographics, and admission/discharge characteristics (IHPA Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, 2025). For analysis, AR DRGs were grouped into twelve categories representing organ system disorders.

2.4 Adverse clinical outcomes

We evaluated three primary outcomes associated with ADR-related hospital admissions: (1) in-hospital mortality and (2) LOS (in days) during the index admission, and (3) all-cause rehospitalisation within 30, 60, and 90 days after discharge.

2.5 Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to balance baseline covariates between patients with and without an ADR-related hospital admission during the study period, to investigate the association between such admissions and adverse clinical outcomes (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024). Prior to finalising the propensity score model for matching, multicollinearity among covariates was assessed using correlation coefficients and variance inflation factors (VIF). Covariates with correlation coefficients above 0.8 (or below −0.8) and VIF >2 were excluded from the model. Nearest-neighbour matching with a 1:1 ratio, and a caliper width of 0.1 on the logit of propensity score without replacement was used for matching (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024).

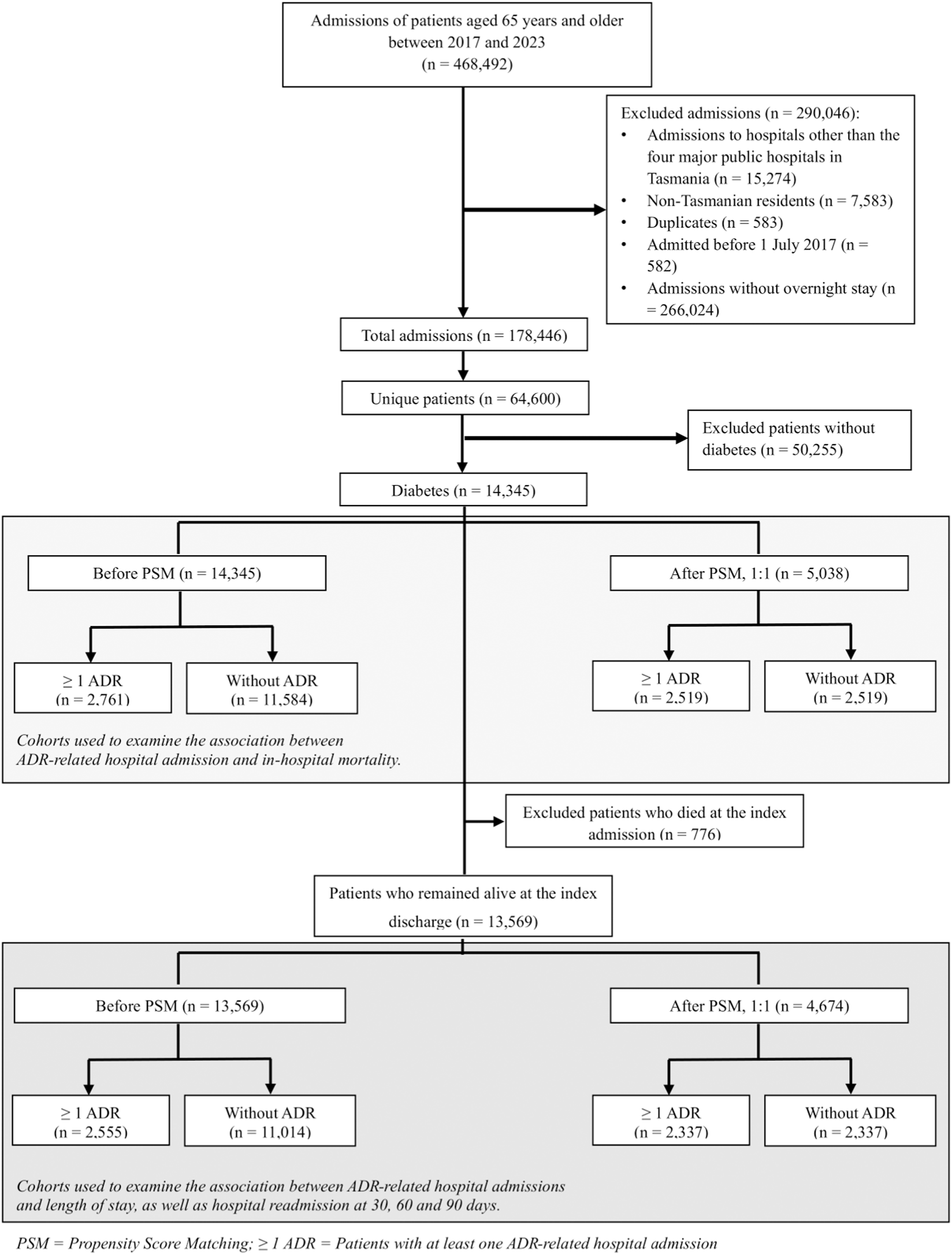

PSM was conducted twice: first on the total cohort and then on a subset. The total cohort included all patients, regardless of their survival status, and was used for in-hospital mortality analysis. The second PSM was applied to a subset of patients who survived the index hospital admission, this subset was used for LOS and rehospitalisation analyses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Patient selection flow chart.

2.6 Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics and were compared between unmatched (pre-PSM) and matched (post-PSM) groups for both the total cohort and the subset. Matching was considered successful for each characteristic if the standardised mean difference (SMD) between the cohorts was <0.1.

We used logistic regression to calculate odds ratios (ORs) for the association between ADR-related hospital admission and in-hospital mortality using the total cohort data. Only patients who survived the index hospital admission were included in the analyses of LOS and hospital readmission. LOS during the index admission was analysed using a generalised linear model (GLM) with a Gamma distribution and a log link, which is appropriate for modelling positively skewed, continuous outcomes, such as LOS (Du et al., 2017). Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) for all-cause rehospitalisation at 30, 60, and 90 days after index discharge. As a visual exploratory analysis, we also plotted stratified Kaplan–Meier survival curves to estimate survival (no rehospitalisation) at 30, 60, and 90 days. Based on clinical relevance, all models were adjusted for age (as a continuous variable), gender, SES, year of admission, hospital, CCI score (as a continuous variable), admission source, AR-DRG, and the total number of hospital admissions during the study period (as a continuous variable). The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist for cohort studies (see Supplementary Table S1) (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007).

All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), employing the “Matching” package for PSM, the glm () with a logit link for OR estimation, the lm () for ratio analysis, coxph () for HR analysis, and survfit () for Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2024).

2.7 Ethics

Ethics approval was obtained from the Tasmanian Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference: H0026248).

3 Results

Patient inclusion is shown in Figure 1. Among 14,345 older adults with diabetes admitted during the study period, 2,761 (19.2%) experienced at least one ADR-related hospital admission. Most patients were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (96.7%). The median age of the overall cohort was 76 years (IQR: 70–82), 56% were male, and 59% were classified as socioeconomically disadvantaged. The median number of hospital admissions per patient was 2 (IQR:1–3), and the median CCI score was 1 (IQR: 0–3). Detailed descriptions of patient demographics and ADR characteristics are reported elsewhere (Vonna et al., 2025). Among those with ADR-related admissions, the three most common AR-DRGs were digestive (17%), respiratory (14%), and 151 circulatory (13%) disorders (see Table 1 for details on the characteristics of patients with and without ADR-related admissions).

TABLE 1

| Characteristics | Unmatched | Matched | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (n = 13,569) | Total population (n = 4,674) | |||||

| With one or more ADR-related hospital admission | Without ADR-related hospital admission | SMD | With one or more ADR-related hospital admission | Without ADR-related hospital admission | SMD | |

| (2,555 (18.8%)) | (11,014(81.2%)) | (2,337 (50%)) | (2,337(50%)) | |||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age (years) (median (IQR)) | 76 (71, 82) | 75 (70, 82) | −0.08 | 76 (71, 82) | 77 (71, 83) | 0.03 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1,074 (42%) | 4,887 (44%) | 0.05 | 1,001 (43%) | 1,031 (44%) | 0.03 |

| Male | 1,481 (58%) | 6,127 (56%) | 1,336 (57%) | 1,306 (56%) | ||

| Year of first admission | ||||||

| 2017–2019 | 1,017 (40%) | 5,037 (46%) | 0.12 | 927 (40%) | 963 (41%) | 0.06 |

| 2020–2021 | 732 (29%) | 2,849 (26%) | 668 (29%) | 605 (26%) | ||

| 2022–2023 | 806 (32%) | 3,128 (28%) | 742 (32%) | 769 (33%) | ||

| Socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Disadvantage | 1,553 (61%) | 6,535 (59%) | 0.03 | 1,416 (61%) | 1,428 (61%) | 0.01 |

| Advantage | 1,002 (39%) | 4,479 (41%) | 921 (39%) | 909 (39%) | ||

| Source of hospital | ||||||

| Launceston general hospital | 954 (37%) | 3,445 (31%) | 0.14 | 864 (37%) | 905 (39%) | 0.04 |

| Northwest regional hospital | 574 (22%) | 2,440 (22%) | 530 (23%) | 517 (22%) | ||

| Royal hobart hospital | 1,027 (40%) | 5,129 (47%) | 943 (40%) | 915 (39%) | ||

| Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score | 2 (1, 4) | 1 (0, 2) | −0.73 | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | −0.02 |

| Diagnostic related group (DRG) | | | 0.4 | | | 0.05 |

| Diseases and disorders of the nervous system | 248 (9.7%) | 1,180 (11%) | | 232 (9.9%) | 247 (11%) | |

| Diseases and disorders of the respiratory system | 332 (13%) | 1,169 (11%) | 291 (12%) | 272 (12%) | ||

| Diseases and disorders of the circulatory system | 340 (13%) | 2,228 (20%) | 331 (14%) | 339 (15%) | ||

| Diseases and disorders of the digestive system | 430 (17%) | 1,085 (9.9%) | 365 (16%) | 364 (16%) | ||

| Diseases and disorders of the hepatobiliary system and pancreas | 107 (4.2%) | 421 (3.8%) | 90 (3.9%) | 81 (3.5%) | ||

| Diseases and disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 195 (7.6%) | 1,549 (14%) | 184 (7.9%) | 177 (7.6%) | ||

| Diseases and disorders of the skin, subcutaneous tissue and breast | 74 (2.9%) | 506 (4.6%) | 73 (3.1%) | 82 (3.5%) | ||

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases and disorders | 179 (7.0%) | 432 (3.9%) | 170 (7.3%) | 175 (7.5%) | ||

| Diseases and disorders of the kidney and urinary tract | 157 (6.1%) | 699 (6.3%) | 150 (6.4%) | 161 (6.9%) | ||

| Blood, immunological and neoplastic disorders | 104 (4.1%) | 210 (1.9%) | 95 (4.1%) | 99 (4.2%) | ||

| Infectious and parasitic diseases | 105 (4.1%) | 358 (3.3%) | 93 (4.0%) | 85 (3.6%) | ||

| Others | 284 (11%) | 1,177 (11%) | 263 (11%) | 255 (11%) | ||

| Admission source | | | 0.12 | | | 0.06 |

| Acute | 2,071 (81%) | 8,404 (76%) | | 1,909 (82%) | 1,963 (84%) | |

| Non-acute | 484 (19%) | 2,610 (24%) | 428 (18%) | 374 (16%) | ||

Baseline characteristics of participants (survived at the discharge index) included in LOS and readmission analyses.

SMD: standardised mean difference.

After PSM, 5,038 patients (2,519 in each group) were included in the in-hospital mortality analysis, and 4,674 patients (2,337 patients in each group) were included in the LOS and readmission analyses. Baseline characteristics before and after PSM are presented in Supplementary Table S2 for the full cohort, and in Table 1 for those who remained alive at index discharge.

Table 2 presents adjusted ORs for in-hospital mortality, comparing the results before and after PSM. Crude ORs are reported in Supplementary Table S3. In the unmatched cohort, the in-hospital mortality rate was 7.5% among patients with an ADR-related admission compared to 4.9% among those without any ADR-related hospital admissions. The adjusted OR for in-hospital mortality was 2.39 (95% CI: 1.96–2.91); p < 0.001. Following matching, ADR-related index hospital admissions remained associated with a 31% increase in odds of in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR = 1.31; 95% CI: 1.03–1.66; p < 0.05).

TABLE 2

| Outcome | Group | Before PSM (n = 14,345) | After PSM (n = 5,038) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude mortality (n, %) | Adjusted OR (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI); p-value | ||

| In-hospital mortality | ≥1 ADR (n = 2,761) | 206 (7.5) | 2.39 (1.96–2.91); p < 0.001 | 1.31 (1.03–1.66); p < 0.05 |

| Without ADR (n = 11,584) | 570 (4.9) | Reference | Reference | |

Number of events and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) with 95% confidence intervals for in-hospital mortality at index admission among all patients, before (n = 14,345) and after PSM (n = 5,038).

OR, odds ratio; ≥1 ADR, Patients with at least one ADR-related hospital admission; PSM, propensity score matching.

Table 3 summarises the association between ADR-related hospital admissions and LOS, as well as all-cause re-hospitalisation at 30-, 60- and 90-day post-index admission discharge. LOS was significantly increased in patients with an ADR-related hospital admission (pre-matching median [IQR] 6.0 [3.0–12.0] days) compared with that of patients without any ADR-related hospital admissions (pre-matching median [IQR] 3.0 [2.0–8.0] days) (p < 0.001). Those with ADRs had a significantly longer LOS, with a ratio of 1.35 (95% CI: 1.24–1.45; p < 0.001) in the unmatched cohort and 1.24 (95% CI: 1.13–1.37; p < 0.001) in the matched cohort (Table 3).

TABLE 3

| Outcomes | Cohort | ≥1 ADR | Without ADR | Ratio (95% CI); p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (Q1, Q3) (days) | ||||

| Length of stay | Before PSM | 6 (3, 12) | 3 (2, 8) | 1.35 (1.24–1.45); p < 0.001 |

| After PSM | 6 (3, 12) | 4 (2, 10) | 1.24 (1.13–1.37); p < 0.001 | |

| | Crude event (n, %) | Adjusted hazard ratio (95% CI); p-value | ||

| All-cause rehospitalisation | ||||

| Within 30 days | Before PSM | 532 (19.3) | 1,170 (10.6) | 1.29 (1.15–1.45); p < 0.001 |

| After PSM | 474 (20.3) | 296 (12.7) | 1.27 (1.08–1.48); p < 0.05 | |

| Within 60 days | Before PSM | 779 (28.2) | 1,683 (14.5) | 1.36 (1.23–1.49); p < 0.002 |

| After PSM | 696 (25.2) | 428 (18.3) | 1.31 (1.15–1.49); p < 0.001 | |

| Within 90 days | Before PSM | 917 (33.2) | 2,086 (18.9) | 1.31 (1.19–1.43); p < 0.001 |

| After PSM | 826 (35.3) | 515 (22.0) | 1.29 (1.14–1.45); p < 0.001 | |

Median length of stay with corresponding ratios and crude mortality (n, %), hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals for all-cause rehospitalisation among patients who remained alive at the index discharge, before (n = 13,569) and after PSM (n = 4,674).

≥ 1 ADR, Patients with at least one ADR-related hospital admission; PSM, propensity score matching; LOS, length of stay.

Readmission rates were consistently higher among patients with ADR-related hospitalisations. In the unmatched cohort, absolute rates at 30, 60, and 90 days were 19.3%, 28.2% and 33.2%, respectively. Adjusted HRs from both the unmatched and matched cohorts demonstrated consistent and statistically significant associations, with ADR-related hospital admissions linked to a 27%–31% increase in risk of rehospitalisation at 30, 60 and 90 days after index discharge (Table 3). In the post-matching analysis, the strongest association was observed at 60 days post-discharge, where ADR-related hospital admissions were associated with a 31% increase in hazard (HR = 1.31 (1.15–1.49); p < 0.001).

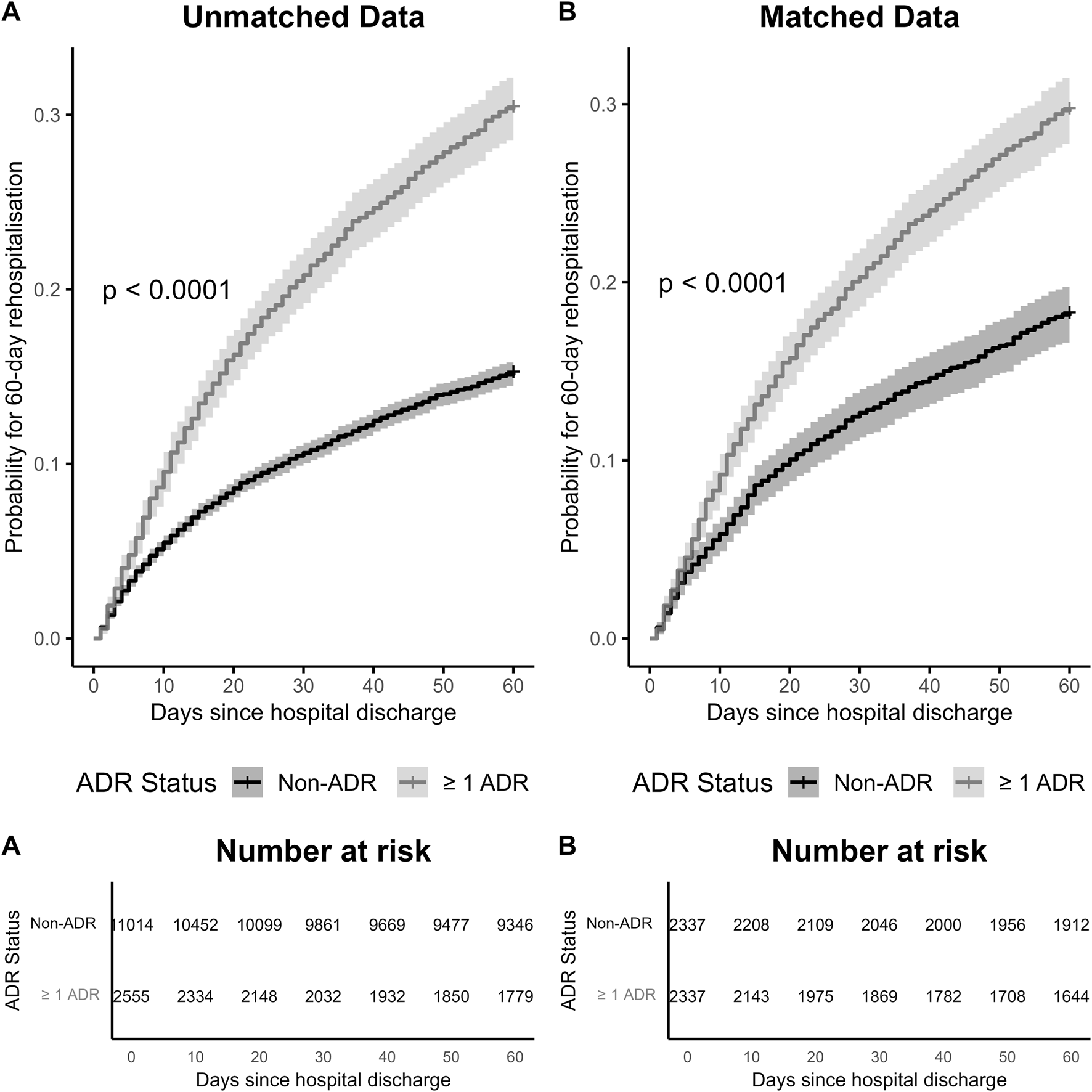

Kaplan-Meier curves (Figure 2) showed that among both matched and unmatched cohorts, patients who had an ADR-related hospital admission experienced significantly higher cumulative incidence for 60-day readmission, compared to those without any ADR-related admissions. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.0001).

FIGURE 2

Kaplan-Meier Curves for 60-Day Readmission in older patients with diabetes, included 13,569 patients who remained alive at the index discharge. (A) Unmatched patients, before PSM. (B) Matched patients, after PSM.

4 Discussion

In this population-based study, nearly one in five older adults with diabetes and hospital admissions experienced at least one ADR-related admission over a period of 6.5 years. Importantly, these patients had worse outcomes than patients without any ADRs.

We applied PSM to minimise confounding between the study and control groups, resulting in well-matched cohorts across demographic, clinical, and hospital-related characteristics. We found ADR-related hospital admissions were associated with an increased length of stay and in-hospital mortality, and readmission at 30, 60 and 90 days, either before or after PSM. However, the magnitude of the associations was lower after PSM and adjustment, particularly for in-hospital mortality analysis, confirming the importance of using propensity score methods to reduce confounding bias and increase the precision of the analysis (Elze et al., 2017; Han et al., 2022).

Older adults with diabetes are inherently at greater risk of ADRs due to multimorbidity, complex medication regimens, and altered pharmacokinetics associated with ageing (Remelli et al., 2022; Elsayed et al., 2025). Our findings indicated that ADR-related hospital admissions were associated with a 2.4-fold increase in the odds of in-hospital mortality among older adults with diabetes, compared to those without ADR-related hospital admissions. This association remained significant even after adjusting for key confounders such as age, sex, comorbidities, and admissions characteristics. This finding aligns with prior research showing that diabetes itself heightens the risk of mortality following an ADR by approximately 55% (Chinmayee et al., 2024), and that individuals with diabetes have nearly triple the in-hospital mortality rate of the general population (Gao et al., 2021). The additional mortality risk observed in our cohort likely reflects the cumulative effect of diabetes-related vulnerability and medication burden. This may be explained by the complexity of diabetes management, particularly in older adults, which relates to multiple comorbid conditions and more medications. These findings reinforce the importance of medication safety and early detection of ADRs in this population. Comparable findings were also reported in a Tasmanian cohort of older adults with dementia, where ADR-related admissions similarly increased the likelihood of adverse outcomes (Zaidi et al., 2024).

Older patients with diabetes and at least one ADR had significantly longer hospital stays than those without any ADRs. This difference was observed both in unmatched and matched groups, with hospital stay being 35% longer in the unmatched group and 24% longer in the matched group. In the unmatched cohort, the difference corresponded to an approximately 3-day longer hospital stay for patients with ADRs. Similarly, a previous prospective study of acutely ill, hospitalised older patients reported significantly longer stays for those with ADRs compared to patients without ADRs (mean 12.4 ± 11.6 days vs. 7.6 ± 6.9 days; log-rank p < 0.0001) (Sandoval et al., 2021). Extended LOS is known to be associated with increased healthcare costs and resource utilisation. Beyond its impact on the healthcare system, extended hospital stay may also be associated with negative effects on patients, which includes deterioration in physical health (e.g., increased risk of opportunistic infections), impaired emotional wellbeing (e.g., prolonged separation from family), and economic burden (e.g., potential out-of-pocket expenses) (Rocha et al., 2020; Alzahrani, 2021; Hirani et al., 2025).

Using the survivor cohort, our results demonstrated that patients with ADR-related hospital admissions had consistently higher rates and hazards of readmission at 30, 60, and 90 days compared to those without ADRs. The adjusted hazard ratios before and after PSM were similar, indicating robustness of the association, with the highest risk was observed at 60 days. A previous study in older adults in France reported that about 50% of patients with ADR-related hospitalisation had all-cause readmission during the 1-year follow-up (Jang et al., 2024). Given that our study had a shorter follow-up period, the readmission rates we observed (e.g., 33.2% at 90 days) are substantially higher in comparison. These findings suggest that ADRs are associated with an ongoing health burden that predisposes patients to subsequent hospitalisations following their initial discharge. This highlights the need for targeted interventions, particularly prior to discharge, such as medication reconciliation, patients’ education regarding medications, and comprehensive discharge planning to reduce readmission risk in this vulnerable population.

The principal strength of this study lies in its large, population-based sample encompassing all major public hospitals in Tasmania and the use of a standardised administrative dataset, ensuring comprehensive coverage and high external validity. The application of propensity score matching and adjusted models helped reduce confounding bias. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. We recognised that residual confounding remained from unmeasured covariates, such as frailty index and diabetes control, which are known to significantly influence mortality and morbidity risks in older adults with diabetes (Sinclair and Abdelhafiz, 2022; Jang et al., 2024). We were unable to access these data, which likely contributes to residual confounding. Additionally, the generalisability of our findings may be limited, as our data were restricted to one state in Australia.

5 Conclusion

This study demonstrates that older adults with diabetes who experience an ADR face a higher risk of in-hospital death, prolonged stays in hospital, and consistently elevated readmission risk across 30, 60 and 90 days. These findings emphasise the urgent need for proactive strategies to improve medication safety in community settings and optimise post-discharge care in this high-risk population. For example, this can be achieved by involving a pharmacist to perform a home medication review using a trigger tool in conjunction with a patient interview. Deprescribing, undertaken by a pharmacist, physician, or multidisciplinary team, can further reduce medication-related risks (Gray et al., 2023; Zhou et al., 2023). In addition, empowering patients through targeted medication education and ongoing support may reduce the likelihood of ADRs and subsequent admissions. Collectively, these measures have the potential to improve outcomes, enhance quality of care, and reduce healthcare burden among older people living with diabetes.

Statements

Data availability statement

The data analyzed in this study is subject to the following licenses/restrictions: All electronic de-identified data was password-protected and stored within Microsoft OneDrive on the UTAS College of Health and Medicine Server. The Tasmanian Department of Health provided a password-protected file listing the patient names and ID numbers for elderly patient admissions between 1 July 2017 and 31 December 2023. The research team added a study number for each individual (to enable tracing). The research data was archived in the UTAS Research Data Portal (RDP) after the completion of the research project. The RDP is noted as being encrypted and is recommended by UTAS to archive the research data (https://rdp.utas.edu.au/#/). The data is accessible to only the researchers listed on the ethics application and retained for five years after publication or longer (until it no longer has research value). After this time, access to the data will be removed, making the data inaccessible and unusable. Requests to access these datasets should be directed to a.vonna@utas.edu.au.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Ethics approval was obtained from the Tasmanian Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference: H0026248). The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The ethics committee/institutional review board waived the requirement of written informed consent for participation from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin because The data being retrospective, creating impracticalities with contacting participants to gain consent. In addition, participants were unaware of their participation, and there was no/low risk to the older resident or changes in treatment due to this research project. The only potential identifier collected was the medical record number, which was not included in the main data file.

Author contributions

AV: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review and editing, Data curation. MS: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing, Data curation. GP: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was not received for this work and/or its publication.

Acknowledgments

Miss Vonna thanks the Government of Aceh, Indonesia and the University of Tasmania for her PhD scholarship.

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author MS declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2025.1729848/full#supplementary-material

References

1

Alzahrani N. (2021). The effect of hospitalization on patients' emotional and psychological well-being among adult patients: an integrative review. Appl. Nurs. Res.61, 151488. 10.1016/j.apnr.2021.151488

2

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2025). National health survey: state and territory findings 2018. Available online at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/health/health-conditions-and-risks/national-health-survey-state-and-territory-findings/2017-18#data-downloads (Accessed March 14, 2025).

3

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2024). Admitted patient care national minimum data set: national health data dictionary version 12 2023. Available online at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/admitted-patient-care-nmds/summary (Accessed November 5, 2024).

4

Cahir C. Curran C. Walsh C. Hickey A. Brannigan R. Kirke C. et al (2023). Adverse drug reactions in an ageing PopulaTion (ADAPT) study: prevalence and risk factors associated with adverse drug reaction-related hospital admissions in older patients. Front. Pharmacol.13, 1029067. 10.3389/fphar.2022.1029067

5

Cheong V. L. Sowter J. Scally A. Hamilton N. Ali A. Silcock J. (2020). Medication-related risk factors and its association with repeated hospital admissions in frail elderly: a case control study. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm.16 (9), 1318–1322. 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.02.001

6

Chinmayee A. Subbarayan S. Myint P. K. Cherubini A. Cruz-Jentoft A. J. Petrovic M. et al (2024). Diabetes mellitus increases risk of adverse drug reactions and death in hospitalised older people: the SENATOR trial. Eur. Geriatr. Med.15 (1), 189–199. 10.1007/s41999-023-00903-w

7

Cosgrave N. Frydenlund J. Beirne F. Lee S. Faez I. Cahir C. et al (2025). Hospital admissions due to adverse drug reactions and adverse drug events in older adults: a systematic review. Age Ageing54 (8), afaf231. 10.1093/ageing/afaf231

8

Dostalek M. Akhlaghi F. Puzanovova M. (2012). Effect of diabetes mellitus on pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of drugs. Clin. Pharmacokinetics51 (8), 481–499. 10.2165/11631900-000000000-00000

9

Du W. Pearson S.-A. Buckley N. A. Day C. Banks E. (2017). Diagnosis-based and external cause-based criteria to identify adverse drug reactions in hospital ICD-coded data: application to an Australia population-based study. Public Health Res. Pract.27 (2), e2721716. 10.17061/phrp2721716

10

Elsayed N. A. McCoy R. G. Aleppo G. Balapattabi K. Beverly E. A. Briggs Early K. et al (2025). 13. Older adults: standards of care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care48 (Suppl. ment_1), S266–S282. 10.2337/dc25-S013

11

Elze M. C. Gregson J. Baber U. Williamson E. Sartori S. Mehran R. et al (2017). Comparison of propensity score methods and covariate adjustment: evaluation in 4 cardiovascular studies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.69 (3), 345–357. 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.060

12

Gao T. Agho K. E. Piya M. K. Simmons D. Osuagwu U. L. (2021). Analysis of in-hospital mortality among people with and without diabetes in south Western Sydney public hospitals (2014–2017). BMC Public Health21 (1), 1991. 10.1186/s12889-021-12120-w

13

Gray S. L. Perera S. Soverns T. Hanlon J. T. (2023). Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to reduce adverse drug reactions in older adults: an update. Drugs and Aging40 (11), 965–979. 10.1007/s40266-023-01064-y

14

Han Y. Hu H. Liu Y. Li Q. Huang Z. Wang Z. et al (2022). The association between congestive heart failure and one-year mortality after surgery in Singaporean adults: a secondary retrospective cohort study using propensity-score matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.9, 858068. 10.3389/fcvm.2022.858068

15

Hirani R. Podder D. Stala O. Mohebpour R. Tiwari R. K. Etienne M. (2025). Strategies to reduce hospital length of stay: evidence and challenges. Medicina61 (5), 922. 10.3390/medicina61050922

16

Howard R. L. Avery A. J. Slavenburg S. Royal S. Pipe G. Lucassen P. et al (2007). Which drugs cause preventable admissions to hospital? A systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.63 (2), 136–147. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02698.x

17

IHPA Independent Hospital Pricing Authority (2025). Australian refined diagnosis related groups version 11.0 technical specifications 2023. Available online at: https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-08/ar-drg_v11.0_technical_specifications_final.pdf (Accessed July 05, 2025).

18

Insani W. N. Whittlesea C. Alwafi H. Man K. K. C. Chapman S. Wei L. (2021). Prevalence of adverse drug reactions in the primary care setting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE16 (5), e0252161. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252161

19

Jang S. A. Kim K. M. Kang H. J. Heo S.-J. Kim C. S. Park S. W. (2024). Higher mortality and longer length of stay in hospitalized patients with newly diagnosed diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract.210, 111601. 10.1016/j.diabres.2024.111601

20

Karahalios A. Somarajah G. Hamblin P. S. Karunajeewa H. Janus E. D. (2018). Quantifying the hidden healthcare cost of diabetes mellitus in Australian hospital patients. Intern. Med. J.48 (3), 286–292. 10.1111/imj.13685

21

Kongkaew C. Noyce P. R. Ashcroft D. M. (2008). Hospital admissions associated with adverse drug reactions: a systematic review of prospective observational studies. Ann. Pharmacother.42 (7-8), 1017–1025. 10.1345/aph.1L037

22

Le Louët H. Pitts P. J. (2023). Twenty-first century global ADR management: a need for clarification, redesign, and coordinated action. Ther. Innovation and Regul. Sci.57 (1), 100–103. 10.1007/s43441-022-00443-8

23

Lim R. Ellett L. M. K. Semple S. Roughead E. E. (2022). The extent of medication-related hospital admissions in Australia: a review from 1988 to 2021. Drug Saf.45 (3), 249–257. 10.1007/s40264-021-01144-1

24

Lu L. Wang S. Chen J. Yang Y. Wang K. Zheng J. et al (2023). Associated adverse health outcomes of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medications in community-dwelling older adults with diabetes. Front. Pharmacol.14, 1284287. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1284287

25

Oscanoa T. J. Lizaraso F. Carvajal A. (2017). Hospital admissions due to adverse drug reactions in the elderly. A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.73 (6), 759–770. 10.1007/s00228-017-2225-3

26

Patel T. K. Patel P. B. (2018). Mortality among patients due to adverse drug reactions that lead to hospitalization: a meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol.74 (6), 819–832. 10.1007/s00228-018-2441-5

27

Pont L. Alhawassi T. Bajorek B. Krass I. (2014). A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors for adverse drug reactions in the elderly in the acute care setting. Clin. Interventions Aging9, 2079–2086. 10.2147/CIA.S71178

28

Remelli F. Ceresini M. G. Trevisan C. Noale M. Volpato S. (2022). Prevalence and impact of polypharmacy in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Aging Clin. Exp. Res.34 (9), 1969–1983. 10.1007/s40520-022-02165-1

29

Rocha J. V. M. Marques A. P. Moita B. Santana R. (2020). Direct and lost productivity costs associated with avoidable hospital admissions. BMC Health Serv. Res.20 (1), 210. 10.1186/s12913-020-5071-4

30

Sandoval T. Martínez M. Miranda F. Jirón M. (2021). Incident adverse drug reactions and their effect on the length of hospital stay in older inpatients. Int. J. Clin. Pharm.43 (4), 839–846. 10.1007/s11096-020-01181-3

31

Sinclair A. J. Abdelhafiz A. H. (2022). Multimorbidity, frailty and diabetes in older people–identifying interrelationships and outcomes. J. Personalized Med.12 (11), 1911. 10.3390/jpm12111911

32

Umegaki H. (2024). Management of older adults with diabetes mellitus: perspective from geriatric medicine. J. Diabetes Investigation15 (10), 1347–1354. 10.1111/jdi.14283

33

Vandenbroucke J. P. Elm Ev Altman D. G. Gøtzsche P. C. Mulrow C. D. Pocock S. J. et al (2007). Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann. Internal Medicine147 (8), W-163–94. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1

34

Vonna A. Salahudeen M. S. Peterson G. M. (2025). Adverse drug reaction-related hospital admissions in older adults with diabetes: incidence and implicated drug classes. Endocr. Pract.31 (11), 1441–1448. 10.1016/j.eprac.2025.06.026

35

Walter S. R. Day R. O. Gallego B. Westbrook J. I. (2017). The impact of serious adverse drug reactions: a population‐based study of a decade of hospital admissions in New South Wales, Australia. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol.83 (2), 416–426. 10.1111/bcp.13124

36

Yadesa T. M. Kitutu F. E. Deyno S. Ogwang P. E. Tamukong R. Alele P. E. (2021). “Prevalence, characteristics and predicting risk factors of adverse drug reactions among hospitalized older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med.9. 10.1177/20503121211039099

37

Zaidi A. S. Peterson G. M. Bereznicki L. R. E. Curtain C. M. Salahudeen M. (2021). Outcomes of medication misadventure among people with cognitive impairment or dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Pharmacother.55 (4), 530–542. 10.1177/1060028020949125

38

Zaidi A. S. Peterson G. M. Curtain C. M. Salahudeen M. S. (2024). Adverse clinical outcomes associated with drug-related hospitalizations in people with dementia. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol.17 (1), 73–78. 10.1080/17512433.2023.2294007

39

Zhou D. Chen Z. Tian F. (2023). Deprescribing interventions for older patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc.24 (11), 1718–1725. 10.1016/j.jamda.2023.07.016

Summary

Keywords

adverse drug reactions, diabetes mellitus, older adult, in-hospital mortality, length of stay, rehospitalisation, clinical outcomes

Citation

Vonna A, Salahudeen MS and Peterson GM (2026) Clinical outcomes of adverse drug reaction-related hospital admissions in older adults with diabetes. Front. Pharmacol. 16:1729848. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2025.1729848

Received

21 October 2025

Revised

24 November 2025

Accepted

15 December 2025

Published

12 January 2026

Volume

16 - 2025

Edited by

Luciane Cruz Lopes, University of Sorocaba, Brazil

Reviewed by

Fathi M. Sherif, University of Tripoli, Libya

Sankha Shubhra Chakrabarti, Banaras Hindu University, India

Updates

Copyright

© 2026 Vonna, Salahudeen and Peterson.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Azizah Vonna, a.vonna@utas.edu

ORCID: Azizah Vonna, orcid.org/0000-0001-6668-1281; Mohammed S. Salahudeen, orcid.org/0000-0001-9131-7465; Gregory M. Peterson, orcid.org/0000-0002-6764-3882

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.