Abstract

Bile acids (BAs) are amphiphilic molecules traditionally recognized for their role in lipid digestion but have gained increased interest for their therapeutic potential. Among them, ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is the most widely prescribed and has been FDA-approved in the treatment of primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), the most common chronic cholestatic liver disease, while also being used off-label in multiple other disorders. The therapeutic effects of BAs are linked to their capacity to modulate signaling pathways, reduce hepatocellular injury, and regulate inflammation. Their physicochemical properties, particularly hydrophobicity, influence both efficacy and toxicity, of which the mechanisms involving receptors such as farnesoid X receptor (FXR), vitamin D receptor (VDR) and Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) help to explain. Recent regulatory milestones include the FDA-approval of chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) in the treatment of cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) and ongoing clinical trials such as that of norucholic acid (NCA) in the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). Expanding research is redefining the BA therapeutic landscape, with applications spanning cholestatic, metabolic, and neurodegenerative diseases. This review will explore established and emerging BA-based monotherapies, combination regimens, and novel BA-driven drug delivery systems.

Introduction

Bile acids (BAs), also referred to as bile salts (BSs) in their conjugated form, are the major organic constituents of bile in mammals and other vertebrates and play essential roles in digestion, endocrine signaling, immune homeostasis, gut health and metabolic functioning (Houten et al., 2006; Hofmann and Hagey, 2008; Chiang, 2013; Faustino et al., 2016). Beyond their well-established role in lipid absorption, accumulating evidence shows that BAs act as bioactive, endogenous ligands that regulate gene expression and cellular function by activating prominent nuclear receptors such as farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and vitamin D receptor (VDR) and by mediating signaling through membrane G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) like Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) (Chiang, 2013; Li and Chiang, 2014; Fuchs et al., 2025). Disruption in BA synthesis, storage and circulation can cause a wide spectrum of pathophysiological consequences if left untreated. Consequently, there is growing interest in harnessing BAs as therapeutic agents for a diverse range of disorders. This review will examine the mechanisms of BA synthesis, cytotoxicity, and therapeutic application in several cholestatic and non-cholestatic diseases, as well as explore emerging evidence for their use in neurodegenerative disorders and their efficacy as a drug delivery system.

BA synthesis and circulation

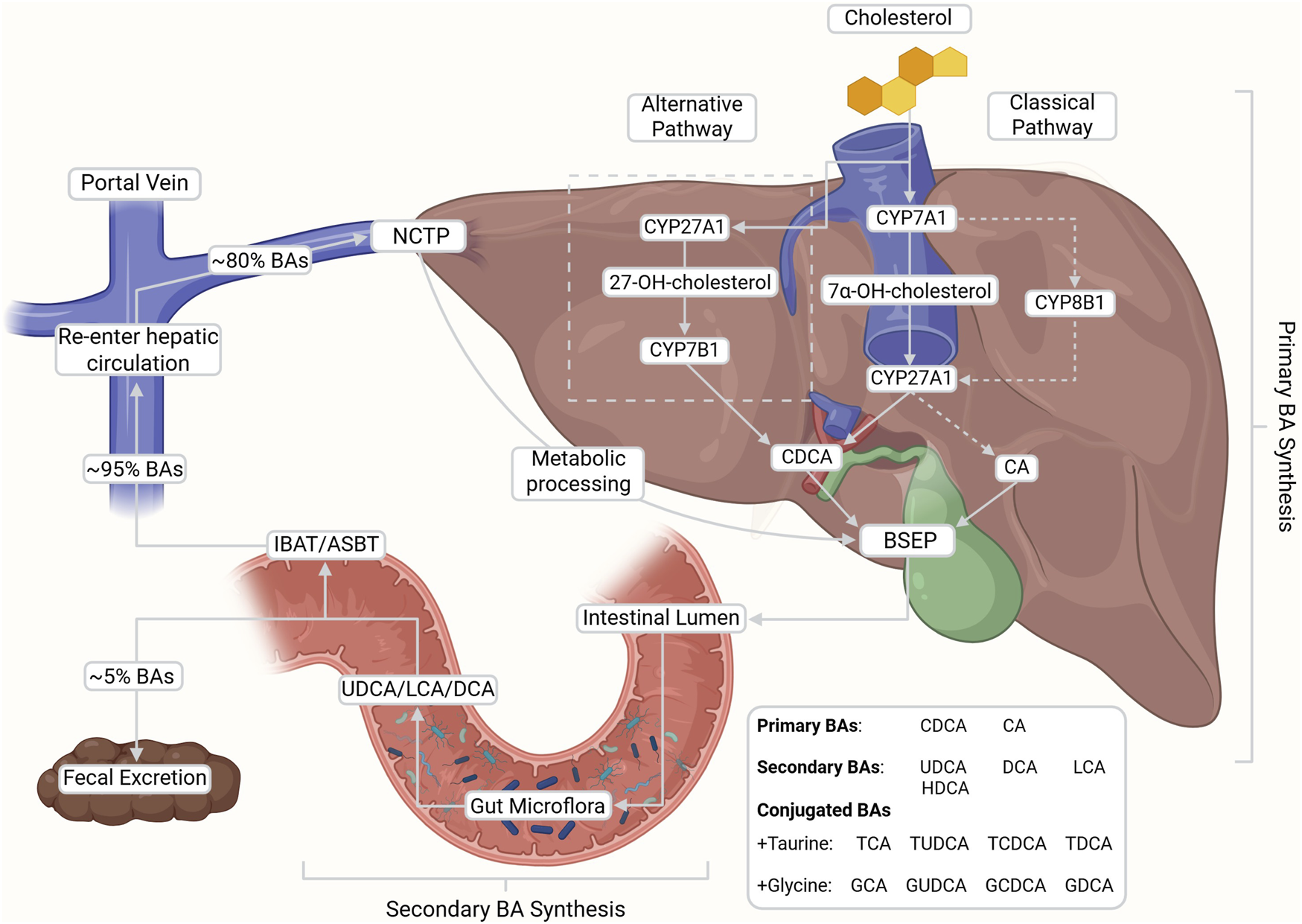

In humans, the multi-enzymatic process of de novo synthesis of BAs occurs in one of two main pathways and is regulated via negative feedback by BA-activated FXR (Shulpekova et al., 2022; Fuchs et al., 2025). BA synthesis represents a major route of cholesterol catabolism (Schwarz, 2004; Chiang, 2013; Li and Chiang, 2014; di Gregorio et al., 2021). The “classical” or neutral pathway, responsible for ∼90% of primary BA production, is initiated and rate-limited in the hepatocytes by cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) (Faustino et al., 2016; Chiang and Ferrell, 2020; di Gregorio et al., 2021; Collins et al., 2023). Hydroxylation at the C7 position yields the intermediate, 7α-hydroxycholesterol, which is then acted upon by sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27A1) to generate chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), or alternatively by 12α-hydroxylase (CYP8B1) before the CYP27A1 step to produce cholic acid (CA) (Figure 1) (Chiang, 2009; di Gregorio et al., 2021).

FIGURE 1

De novo synthesis, enterohepatic circulation, and microbial transformation of bile acids (BAs). Primary BAs, cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), are synthesized from cholesterol via the classical (CYP7A1-initiated) and alternative (CYP27A1-initiated) pathways in the liver. Upon conjugation with glycine or taurine, BAs are secreted into the intestine where they facilitate lipid digestion and are subsequently reabsorbed into portal circulation (∼95%) via the ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT/ASBT) and into the hepatocytes via sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP). After metabolic processing, BAs are reintroduced into the bile via bile salt export pumps (BSEP) at the bile canaliculi. A small fraction escapes reabsorption and is modified by gut microbiota into secondary BAs (e.g., DCA, LCA, UDCA), contributing to the recycling and regulatory feedback of the enterohepatic system. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

The “alternative” or acidic pathway, which accounts for ∼10% of primary BA synthesis, is initiated by mitochondrial CYP27A1 in both hepatic and extrahepatic tissues (Schwarz, 2004; di Gregorio et al., 2021). This hydroxylates cholesterol at the C27 position to produce the oxysterol intermediate 27-hydroxycholesterol, which is subsequently modified by oxysterol 7α-hydroxylase (CYP7B1) to generate CDCA (Schwarz, 2004; Chiang, 2009; di Gregorio et al., 2021; Shulpekova et al., 2022; Collins et al., 2023). Both pathways yield amphiphilic molecules with distinct hydrophilic and hydrophobic domains (Hofmann, 1999).

The major primary BAs (CA and CDCA) are predominantly conjugated with glycine and taurine as BSs (Chiang, 2013; Faustino et al., 2016). Conjugation is capable of lowering pKa, increasing hydrophilicity, reducing cytotoxicity, and enhancing solubility under physiological conditions (Faustino et al., 2016; Shulpekova et al., 2022). These properties improve lipid emulsification and facilitate mixed micelle formation in the small intestine (di Gregorio et al., 2021; Collins et al., 2023). Conjugated BAs are stored in the gallbladder during fasting and are released into the duodenum in response to meals (Schwarz, 2004; Chiang, 2009; Faustino et al., 2016). In addition to their digestive role, BAs have also been implicated in stimulating postprandial insulin secretion, thereby contributing to glucose metabolism (Li et al., 2012; Chiang and Ferrell, 2020). In the intestine, gut microbiota deconjugate and transform primary BAs into secondary BAs such as deoxycholic acid (DCA), lithocholic acid (LCA), hyodeoxycholic acid (HDCA) and ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) (Faustino et al., 2016; Shulpekova et al., 2022). More recently, gut microbiota are reported to deconjugate and transform primary BAs with amino acids besides glycine and taurine, producing microbial amino-acid-conjugated bile acids (MABAs), although their physiological significance remains to be elucidated (Quinn et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2025).

Approximately 95% of BAs are reabsorbed, with the majority of conjugated BA reuptake occurring in the ileum through the ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT), also known as the apical sodium-dependent bile acid transporter (ASBT), located on the brush border membrane of enterocytes (Chiang, 2009; 2013; Shulpekova et al., 2022). A smaller fraction of protonated, unconjugated BAs are largely absorbed passively along the colon with only about 5% escaping reabsorption for subsequent excretion in feces (Chiang, 2009; 2013; Shulpekova et al., 2022). Around 80% of these primary and secondary BAs then return to the liver from portal blood circulation via sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP) activity along the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes (Tan et al., 2024). This crucial reuptake maintains BA levels in systemic circulation and allows for the recycling and reuse of BAs in enterohepatic circulation (Hofmann and Hagey, 2008; Tan et al., 2024). From here, BAs are resecreted into the bile canaliculi via bile salt export pumps (BSEP) to reintegrate into bile (Kubitz et al., 2012). Notably, dysfunction in the regulation or expression of the BA transport proteins IBAT/ASBT, NTCP and or BSEP have been linked with numerous pathologies that will be discussed later in this review. BAs lost to excretion are replenished by de novo synthesis to maintain consistent levels within the body (Chiang, 2009, Ching, 2013).

Upon reentry to circulation in humans, both the conjugated and free forms of BA bind to FXR to regulate further production via one of two pathways (di Gregorio, Cautela and Galantini, 2021; Shulpekova et al., 2022). In the first, BA-bound FXR in ileal enterocytes induces the production of the endocrine peptide fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), which then activates hepatic FGF receptor 4 (FGFR4), resulting in the suppression of CYP7A1 expression and inhibition of the classical BA synthesis pathway (Chiang, 2009; Shulpekova et al., 2022). In the second pathway, BA-bound hepatic FXR forms a complex with retinoid X receptor to produce a small heterodimer partner, leading to suppression of CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 (di Gregorio et al., 2021; Shulpekova et al., 2022). In both pathways, FXR acts as a critical inhibitory receptor to regulate the over or underproduction of BAs (Schwarz, 2004; Chiang, 2009; di Gregorio et al., 2021).

Circulating BAs have also recently been implicated as important signaling metabolites and mediators of neurological disease in both the brain and blood brain barrier (BBB) (Ferrell and Chiang, 2021). The crosstalk between the metabolic functions of the liver, microbial modification and conjugation of BAs in the gut and cellular signaling of BAs within the brain constitute what is known as the gut-liver-brain axis (GLBA) (Ferrell and Chiang, 2021; Sun et al., 2024). Communication between these three systems impact numerous physiological processes including host immunity modulation, metabolism and neurodevelopment (Sun et al., 2024). Blood BAs are also able to cross the BBB to act directly or indirectly with receptors in the brain, though disruption to serum BA levels due to hepatointestinal pathology can influence systemic inflammatory responses, BBB permeability, and neuronal synaptic functioning (Yeo et al., 2023; Sun et al., 2024). Notably, increased serum BA levels have also been found to modulate the permeability of both the BBB through the compromise of tight junctions and gut vascular barrier via the FXR receptor (Quinn et al., 2014; Sun et al., 2024). This suggests interesting implications for the involvement of BA in neurodegenerative disease and its potential role as a therapeutic agent. Current knowledge regarding the mechanisms by which BAs affect the BBB are under investigation.

BAs as pathogenic agents

Pathogenesis of BA-associated diseases and symptoms

Dysfunction in the synthesis, storage or circulation of BAs can result in a range of physiological disturbances. Disorders arising from these defects in enterohepatic circulation are generally referred to as cholestatic diseases or cholestasis (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Beuers et al., 2023). This is defined as the impairment of BA flow resulting in a toxic accumulation of BAs and BA metabolites in the liver and systemic circulation (Li and Apte, 2015). Such impairments may be driven by genetic, hormonal, hepatobiliary, metabolic, exogenous, autoimmune or alloimmune factors (Li and Apte, 2015; Sarcognato et al., 2021).

Although the underlying pathophysiology varies, cholestasis can lead to inflammation, fibrosis, cirrhosis, hepatocyte dysfunction, hepatocellular carcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma, and ultimately end-stage liver disease (ESLD) requiring transplantation (Li and Apte, 2015; Sarcognato et al., 2021). Mechanical or structural obstructions to BA flow may further complicate disease progression (Cariello et al., 2022).

In response to rising intrahepatic concentrations of hydrophobic and hepatotoxic BAs, hepatocytes upregulate BA sulfation as a major adaptive detoxification pathway (Alnouti, 2009). Sulfotransferase-mediated conjugation increases BA solubility and reduces membrane-disruptive properties, promoting basolateral efflux and renal elimination (Alnouti, 2009). As a result, sulfated BAs function as a promising marker for distinguishing types of liver injuries and identifying BA overload as well as a protective mechanism to prevent further hepatic damage (Alnouti, 2009; Masubuchi et al., 2016). Dysregulated sulfation has been linked to increased disease severity in cholestasis and contributes to altered immune signaling (Alnouti, 2009; Ito et al., 2024).

Clinically, cholestasis often presents with jaundice due to hepatic insufficiency, persistent fatigue, features of sicca complex, and most notably, pruritus which is reported in up to 80% of affected individuals, which remains one of the most burdensome symptoms and a notable adverse effect of therapeutic BA usage (Beuers et al., 2014; Hirschfield et al., 2017; Beuers et al., 2023). Given this dual unique role of BAs in both disease causation and therapy, understanding their toxic potentials is essential to maximizing benefit and minimizing harm.

BA toxicity and hydrophobicity

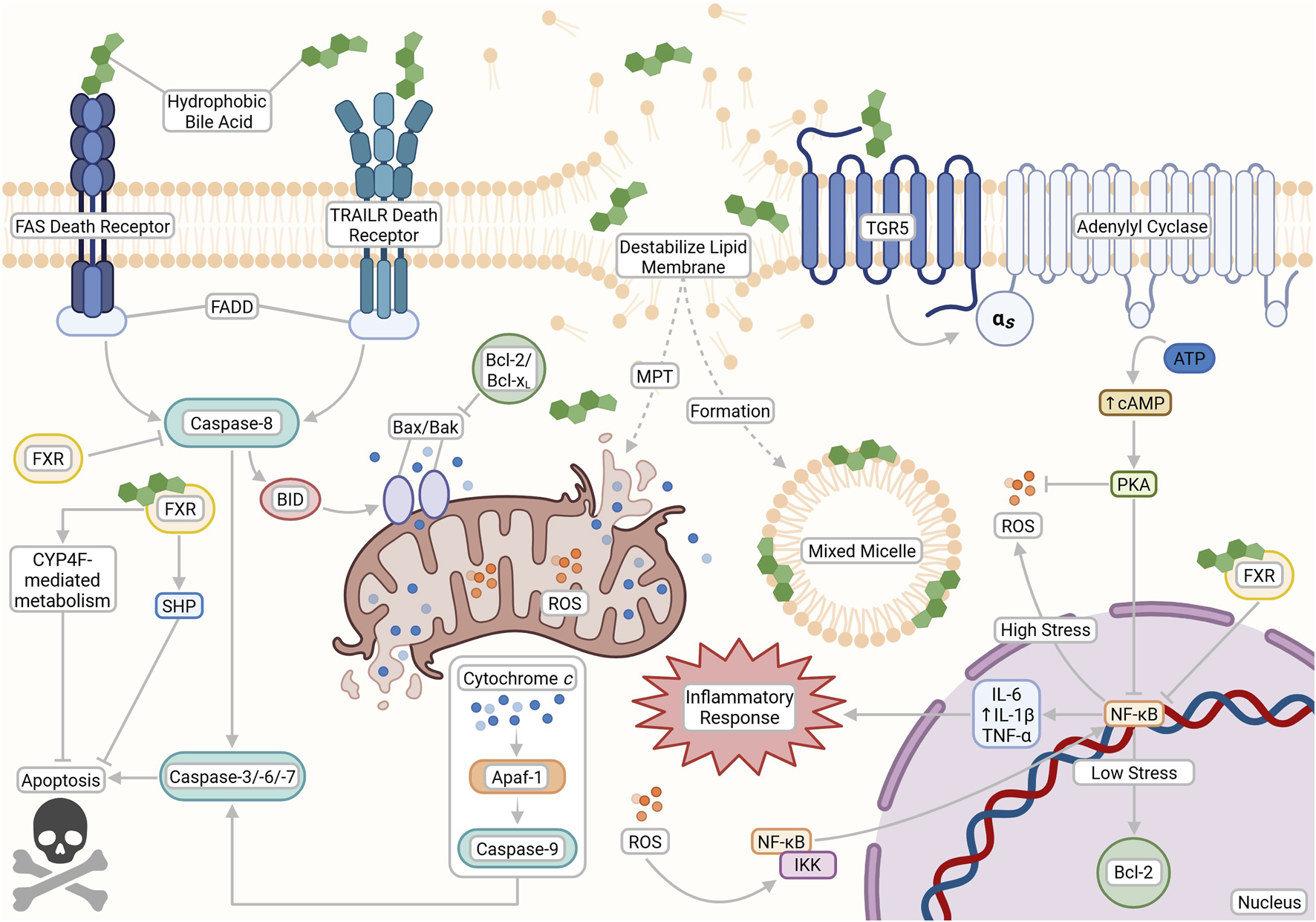

While all BAs are amphiphilic, their hydrophobic-hydrophilic balance influences digestive efficacy and cytotoxic potential (Perez and Briz, 2009). The same hydrophobicity that enables effective micelle formation for lipid digestion, also facilitates its interaction with nonpolar cell membranes (Hofmann, 1999). Highly hydrophobic BAs, such as LCA, can disrupt lipid bilayers, increasing membrane permeability and promoting apoptosis (Perez and Briz, 2009). In cholestasis, progressive accumulation of hydrophobic BAs within the bile has experimentally been shown to induce hepatocyte injury, necrosis and subsequent liver damage (Hofmann, 1999; Amaral et al., 2009; Perez and Briz, 2009). This process frequently involves mitochondrial dysfunction characterized by membrane disruption, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT) (Perez and Briz, 2009). As a result of this, the liver relies heavily on BA sulfation which markedly increases hydrophilicity, lowers detergent activity, and enhances solubility in biological fluids to reduce BA overload (Alnouti, 2009).

ROS production activates nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling via IκB kinase (IKK) activation, driven by upstream mediators such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (Lingappan, 2018). Activated NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, promoting transcription of pro-inflammatory, pro-oxidant and anti-apoptotic genes (e.g., Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL) and upregulating inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α (Catz and Johnson, 2001; Liu et al., 2017; Lingappan, 2018). Notably, prolonged or chronic ROS production can eventually inhibit NF-κB activity, while sustained inflammation further enhances oxidative stress, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of injury (Liu et al., 2017; Forrester et al., 2018).

At pathophysiological concentrations, hydrophobic BAs can also activate transmembrane death receptors such as Fas and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (TRAILR) (Wei et al., 2020). This recruits the Fas associated death domain (FADD), subsequently leading to the activation of caspases, a family of specialized proteases that execute programmed cell death (Amaral et al., 2009). Caspase-8, the main initiator of death receptor signaling, cleaves cytoplasmic Bid, which activates and induces conformational changes in the Bax and Bak proteins to relay the apoptotic signal to the mitochondria (Amaral et al., 2009; McArthur and Kile, 2018). Bax/Bak pore formation in mitochondrial membranes leads to cytochrome c release into the cytosol, apoptosome assembly with Apaf-1, and activation of caspase-9 and the effector caspases-3, -6, and -7, culminating ultimately in cell death (Amaral et al., 2009; Zhang M. et al., 2017; McArthur and Kile, 2018).

BA activation of TGR5 has been linked to pro-proliferative mechanisms that possess implications in both cancerous and regenerative settings (Pols et al., 2011; Guo et al., 2016). Varied findings have observed that TGR5 was overexpressed in cancers such as esophageal adenocarcinoma but suppressed the proliferation of gastric cancer cells, suggesting a potential tumorigenesis involvement (Guo et al., 2016). Elevated serum BA levels have also been found to enhance the proliferation of cholangiocarcinoma cells in animal models through a proposed TGR5-mediated mechanism (Reich et al., 2016).

The nuclear receptor VDR plays a critical role in hydrophobic BA regulation. Although best known as the mediator of the calcemic hormone 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3), VDR is also a high-affinity receptor for the secondary BA, LCA (Makishima et al., 2002; Pavek et al., 2010; Cheng et al., 2014). Activation of VDR by 1,25(OH)2D3 or LCA induces the expression of in vivo human cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4), a critical enzyme involved in the biotransformation of 50% of drugs as well as Vitamin D3 (Pavek et al., 2010; Kasarla et al., 2022). Although the pregnane X receptor (PXR) is the dominant regulator of CYP3A4 induction in the liver, VDR also transactivates CYP3A4 in the intestine and is broadly expressed across many tissues (Cheng et al., 2014). CYP3A4 hydroxylates LCA, reducing its hydrophobicity while also suppressing intestinal BA transporter expression, inhibiting CYP7A1 to limit further BA synthesis and reducing inflammation through the regulation of the NF-κB pathway (Han and Chiang, 2009; Cheng et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2020). In multiple studies, VDR-deficient mice show markedly worsened LCA-induced hepatotoxicity, altered body and colonic morphology, increased hepatic inflammation and heightened susceptibility to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) compared to controls, underscoring VDR’s importance in safeguarding against cholestatic injury (Cheng et al., 2014; Dong et al., 2020). Notably, high levels of LCA that activate VDR may limit its practical therapeutic capacity. However, recent studies have explored the potential of LCA derivatives such as LCA acetate which display greater potency and improved safety profiles compared to LCA itself (Adachi et al., 2005; Sasaki et al., 2021).

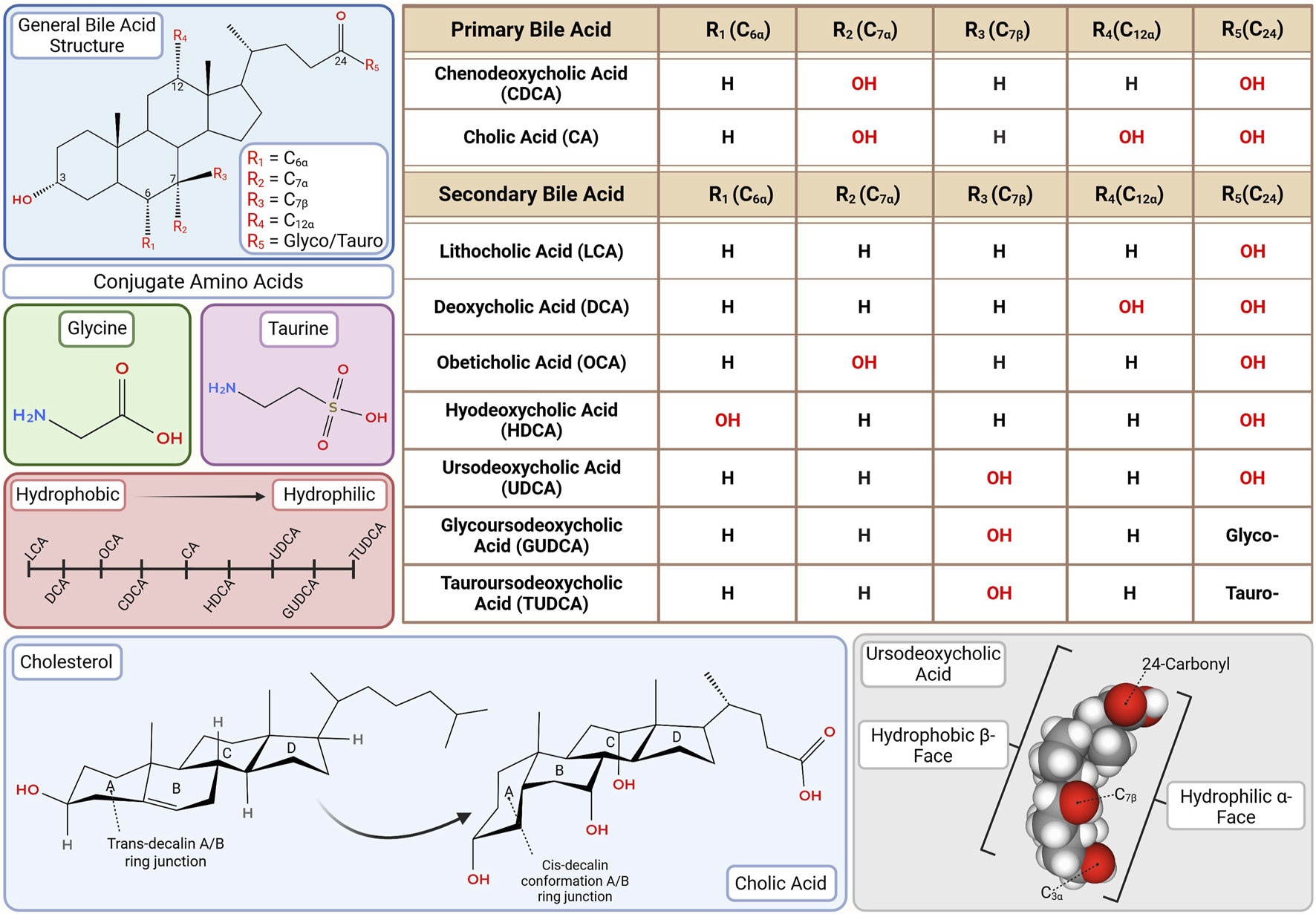

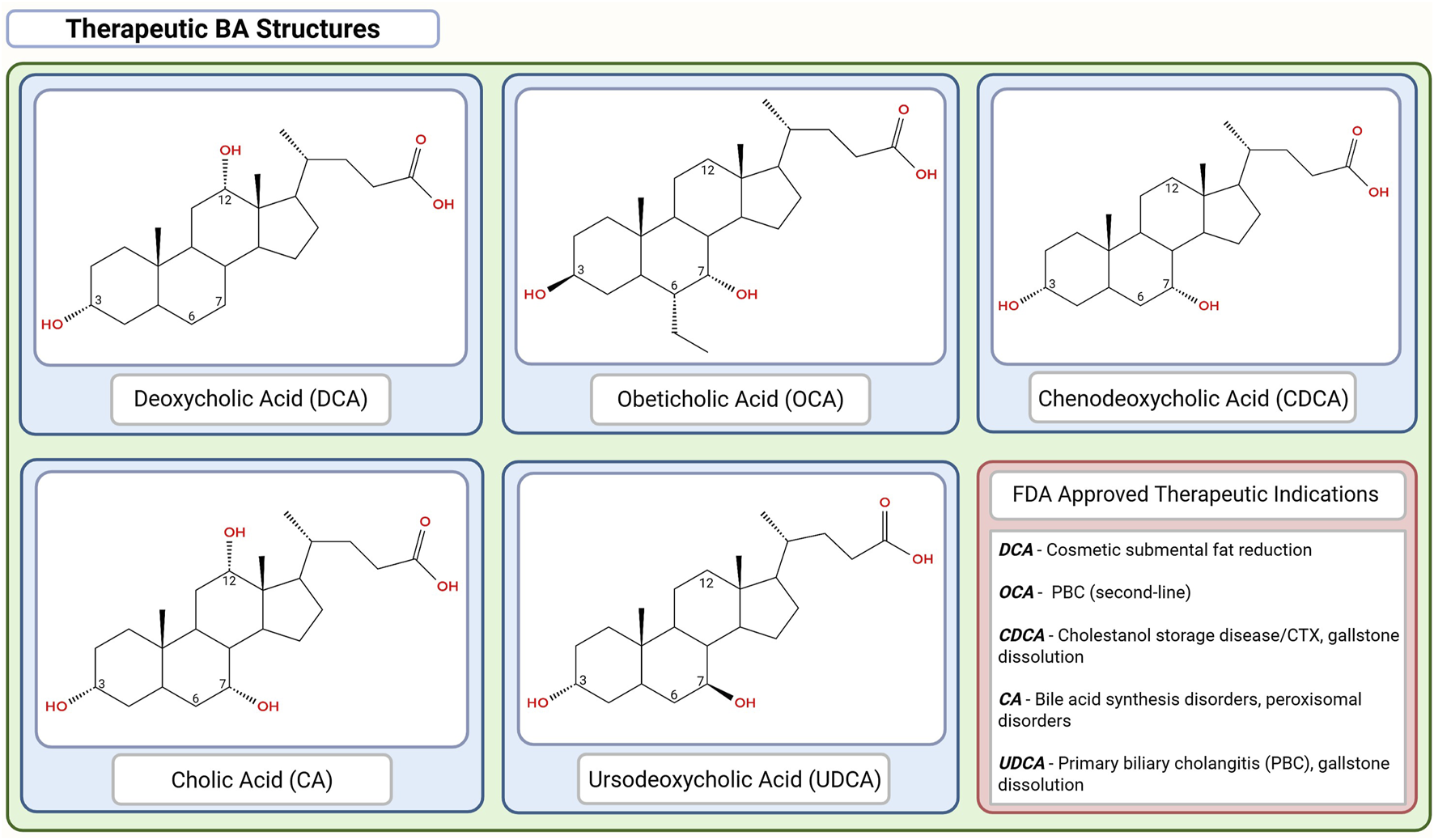

Hydrophobicity is dictated by the number, degree and position of hydroxylation on the cholesterol backbone, orientation of hydroxyl groups, and the nature of glycine or taurine conjugation (Thomas et al., 2008; Perez and Briz, 2009). Hydrophilic BAs, such as UDCA, glycoursodeoxycholic acid (GUDCA) and tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), are favored therapeutically for their lower toxicity and broad clinical utility (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002; Pusl and Beuers, 2006; Perez and Briz, 2009; Khalaf et al., 2022). In contrast, moderately hydrophobic BAs like CDCA and its semi-synthetic derivative obeticholic acid (OCA) are potent FXR agonists and used to modulate BA synthesis in selected cholestatic conditions (Liu et al., 2014; Zhang Y. et al., 2017). With EC50 values of ∼10 μM for CDCA and ∼100 nM for OCA, the latter’s greater potency has expanded its use despite higher toxicity risk at elevated doses though, notably, OCA has been banned for therapeutic usage in Europe (Zhang Y. et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2024). Hydrophobicity hierarchy (most to least) is: LCA > DCA > OCA > CDCA > CA > HDCA > UDCA > GUDCA > TUDCA (Figure 2) (Heuman, 1989; Perez and Briz, 2009).

FIGURE 2

Bile acid (BA) structure and hydrophilicity. The number, degree, position and stereochemistry of hydroxyl groups on the steroid nucleus (especially at C3, C6, C7, and C12) determine hydrophilic-hydrophobic balance, influencing toxicity and receptor binding. Glycine or taurine conjugation further moderates solubility, enterohepatic circulation, kinetics and receptor binding affinity. This diversity underpins the rationale for selective therapeutic application ranging from FXR agonist-based interventions with OCA to neuroprotective strategies using GUDCA and TUDCA. This figure was created in BioRender.com. The chemical structures were created in app.molview.com.

Notably, usage of more hydrophobic BAs, such as OCA, is predictably reported to cause BA-induced pruritus (Nevens et al., 2016), making it one of the most frequent and dose-limiting adverse effects of BAs that significantly impair patient quality of life. Although its molecular mechanism remains incompletely understood, our group and others have identified Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor X4 (MRGPRX4), a human GPCR specifically expressed in peripheral itch sensing neurons, as a receptor for BA and bilirubin that potentially mediate BA-induced pruritus (Meixiong et al., 2019; Meixiong, 2025; Yu et al., 2019). However, other studies have questioned this model, reporting that BSs and bilirubin activate MRGPRX4 or other known pruriceptors only at supraphysiological concentrations, and that albumin at physiological levels abolishes such activation, suggesting these metabolites may not directly drive cholestatic itch (Wolters et al., 2025).

BAs as therapeutic agents

Therapeutic mechanisms of BAs

Given the harmful effects of cholestasis, certain BAs demonstrate their therapeutic benefits via multiple mechanisms to address a variety of conditions. UDCA in particular is proposed to act through three primary therapeutic mechanisms (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002).

First, it protects cholangiocytes from BA-induced cytotoxicity by lowering the concentration of highly hydrophobic BAs that can accumulate and cause cellular necrosis in cholangiocytes and hepatocytes (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002; Perez and Briz, 2009). This reduction also limits the activation of both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent apoptotic death receptors by cytotoxic BA buildup and oxidative stress (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002; Amaral et al., 2009; Perez and Briz, 2009).

Second, immunomodulative properties activate cell survival signaling pathways that both attenuate apoptosis and prevent mitochondrial dysfunction (Amaral et al., 2009). While unbound FXR exhibits anti-apoptotic effects through the inhibition of caspase-8, BA–activated FXR has also been shown to protect against apoptosis induced by BA overload and deoxysphingolipids, while simultaneously modulating the NF-κB-mediated inflammatory response (Fleishman and Kumar, 2024). This occurs through the promotion of Cytochrome P450 Family 4 Subfamily F (CYP4F)-mediated metabolism of the pro-apoptotic deoxysphingolipids to prevent apoptosis (Fleishman and Kumar, 2024). BA overload is inhibited through the suppression of CYP7A1 and CYP8B1 expression, thereby helping to alleviate cholestasis through the reduction of BA synthesis (Fleishman and Kumar, 2024). BA–activated FXR induces the nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner (SHP), which represses the transcription of these key BA synthetic enzymes, thereby reducing BA accumulation and mitigating apoptosis (Fleishman and Kumar, 2024).

Third, enhanced bile secretion in the hepatocytes and bile duct epithelial cells improve enterohepatic circulation to limit cholestasis (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002; Amaral et al., 2009; Perez and Briz, 2009).

Recent studies have also elucidated the role of BA-activated TGR5 in NF-κB inflammatory suppression in the liver and stomach. Ligand-bound TGR5 induces a structural shift that activates its coupled Gαs protein and promotes the conversion of ATP to cAMP by adenylate cyclase, resulting in elevated intracellular cAMP levels (Zangerolamo et al., 2025). The increase in cAMP activates protein kinase A (PKA), which plays a key role in suppressing NF-κB signaling by disrupting its activation and limiting inflammatory gene expression (Zangerolamo et al., 2025). TGR5 activation has also been seen to suppress the production of cytokines in both Kupffer and THP-1 cells (Guo et al., 2016). TGR5 can be activated by both conjugated and unconjugated BAs. However, the most potent activators are, ironically, the hydrophobic LCA and DCA, with EC50 values of 0.53 and 1.25 μM respectively, in stark contrast to the significantly weaker activation by UDCA, which has an EC50 of 36.4 μM (Zangerolamo et al., 2025). Notably, evidence also suggests that BA-activated TGR5 may enhance caspase-8 activation, leading to increased apoptotic signaling (Yang et al., 2007). More research is needed to clarify the therapeutic role of BA-activated TGR5 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3

The opposing cytotoxic and cytoprotective effects of bile acids (BAs) based on their physicochemical properties and receptor interactions. Hydrophobic BAs can initiate apoptosis through both nonspecific interactions and death receptor pathways (FAS and TRAILR), leading to caspase activation, lipid membrane destabilization, mixed micelle formation, mitochondrial permeability transition (MPT), ROS production, and downstream inflammation. In contrast, cytoprotective pathways are activated by hydrophilic BAs and TGR5 signaling, which stimulates cAMP production via adenylyl cyclase to support anti-apoptotic responses and reduce oxidative stress. FXR signaling also plays a dual role by modulating BA metabolism and inhibiting apoptosis through transcriptional repression of pro-death genes. This figure was created with BioRender.com.

BAs have been increasingly implicated in the regulation of glycemic control and overall lipid and glucose metabolism (Zarrinpar and Loomba, 2012; Guo et al., 2016; Cadena Sandoval and Haeusler, 2025). BA activation of TGR5 has been shown to enhance the release of gut-derived incretins such as GLP-1, which stimulate insulin release and suppress glucagon production (Guo et al., 2016; Cadena Sandoval and Haeusler, 2025). Some studies suggest that hydrophilic BAs may act directly on pancreatic β-cells, exerting cytoprotective effects and promoting insulin secretion via TGR5-PKA signaling or through FXR-mediated induction of the TRPA1 ion channel or the FOXA2 transcription factor (Lee et al., 2010; Düfer et al., 2012). However, in vivo mouse models indicate that the predominant metabolic benefits of BAs are likely mediated indirectly through gut hormone release rather than direct β-cell stimulation (Kuhre et al., 2018). Further supporting their metabolic relevance, reduced circulating levels of 12α-hydroxylated BAs, including DCA, have been associated with improved insulin sensitivity in humans (Cadena Sandoval and Haeusler, 2025). TUDCA, an established inhibitor of endoplasmic reticular stress, is also currently being investigated for its role in vascular dysfunction, mitochondrial stabilization, and anti-apoptotic activity (Wu et al., 2024b).

These cytoprotective and metabolic regulatory properties have become the focus of recent research in the potential use of BAs in both metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases, which will be discussed later in this review. Lastly, therapeutic BAs have been suggested to stimulate the liver’s bile secretion by activating signaling pathways that help move transporter proteins such as BSEP and MRP2 to the cell membrane, allowing them to pump bile components more effectively (Paumgartner and Beuers, 2002). Indeed, BAs possess numerous mechanisms by which they are able to potentially treat cholestatic and non-cholestatic conditions. Therefore, this review will primarily focus on the potential therapeutic roles of BAs and their metabolites across a range of reported pathologies, examining specific treatment applications in relation to their corresponding conditions (Table 1).

TABLE 1

| Approval status | Bile acid/metabolite | Therapeutic use | Adverse effects | Typical dosage range | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FDA approved agents | Deoxycholic acid (DCA) |

|

Injection site reactions, swelling, pain, hypertension, erythema, pruritus |

|

Šarenac and Mikov (2018), Liu, Li and Alster (2021) |

| Obeticholic acid (OCA) |

|

Pruritus, fatigue, increased LDL, hepatotoxicity (dose-dependent) |

|

Fiorucci and Distrutti (2019b), Beuers et al. (2025) | |

| Chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) |

|

Diarrhea, reversible ↑ aminotransferases, GI upset, hepatotoxicity, and hypercholesterolemia |

|

Fiorucci and Distrutti (2019a), Zaccai et al. (2024) | |

| Cholic acid (CA) |

|

Diarrhea, abnormal LFTs, pruritus, rare hepatotoxicity |

|

Šarenac and Mikov (2018), Beuers et al. (2025) | |

| Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) |

|

Diarrhea, mild GI upset, rare hepatotoxicity |

|

Cabrera, Arab and Arrese (2019), Beuers et al. (2025) | |

| Non-FDA approved agents | Lithocholic acid (LCA) | None (not approved for any indication) | Hepatotoxicity, cholestatic injury, potential anti-inflammatory effects in colon (preclinical) | Not established | Ward et al. (2017), Lenci et al. (2023) |

| Hyodeoxycholic acid (HDCA) | None (Investigational) potential usage in NAFLD/MAFLD | Not established | Not established | Kuang et al. (2023) | |

| Glycoursodeoxycholic acid (GUDCA) | None (Investigational) potential usage in neurodegenerative and metabolic diseases | Not established | Not established | Huang et al. (2022a), Chen et al. (2023) | |

| Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) | None (Investigational) used in some countries for cholestatic liver disease, potential usage in neurodegenerative disease | Not established; generally well tolerated in studies | Not established | Zangerolamo et al. (2021), Khalaf et al. (2022) |

Therapeutic applications, safety profile, dosage ranges, and regulatory status of selected bile acids (BAs) and their derivatives (Figure 4).

This table summarizes the current FDA-approved indications, common and investigational therapeutic uses, reported adverse effects, typical dosage ranges for adults and pediatric populations (where available), and regulatory approval status of naturally occurring and synthetic BAs. References correspond to key supporting literature. Dosage ranges for investigational agents are provided only when available from preclinical or early clinical studies.

FIGURE 4

Chemical structures of the FDA-approved therapeutic bile acids (BAs). Chemical structures are organized in descending order of hydrophobicity with DCA > OCA > CDCA > CA > UDCA. This figure was created in BioRender.com. The chemical structures were created in app.molview.com.

Therapeutic effects of BAs

Adult cholestatic diseases

Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC)

PBC is a chronic autoimmune-mediated cholestatic disease characterized by loss of tolerance to the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex E2 (PDC-E2) which results in lymphocytic damage to intrahepatic bile duct epithelium (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Sarcognato et al., 2021; Houri and Hirschfield, 2024). It predominantly affects middle-aged women with an approximate 10:1 female-to-male ratio in reported prevalence (Sarcognato et al., 2021; Trivella et al., 2023).

The pathogenesis of PBC appears to be associated with a combination of genetic predisposition as well as specific environmental triggers such as cigarette smoking, cosmetic hair dye products, infectious agents, xenobiotics, reproductive hormone replacement and nail polish (Sarcognato et al., 2021; Levy et al., 2023; Houri and Hirschfield, 2024; Tanaka et al., 2024). The hallmark serological finding is the presence of antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) which is present in more than 90% of cases (Levy et al., 2023).

UDCA at 13–15 mg/kg/day is considered the first-line therapy, improving transplant-free survival and delaying disease progression (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Sarcognato et al., 2021). For patients with inadequate biochemical response or intolerance to UDCA, OCA, a steroidal FXR agonist, has received accelerated FDA-approval as the second-line therapy, either in combination with UDCA or as a monotherapy (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Levy et al., 2023; Beuers et al., 2025; Fuchs et al., 2025). Dosing is generally initiated at 5 mg/day and can be increased to 10 mg/day after 3 months if liver tests remain abnormal (Hasegawa et al., 2021). OCA’s relatively high hydrophobicity makes it a more toxic alternative to UDCA and is contraindicated in patients with decompensated cirrhosis or portal hypertension due to risk of serious hepatic adverse events (Beuers et al., 2025). This, coupled with inconsistent phase IV studies have led to the European Medicines Agency to revoke marketing for the drug.

Other BA related therapies include proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists and IBAT inhibitors. Both seladelpar (PPAR-δ agonist) and elafibranor (PPAR α/δ agonist) were granted accelerated FDA-approved as well as authorization by the European Commission for the treatment of PBC; phase 3 trials have demonstrated significant improvement in biochemical response and are generally well tolerated with seladelpar also being associated with reduced pruritus (Hirschfield et al., 2024; Kowdley et al., 2024). Bezafibrate (pan-PPAR) is not FDA-approved for PBC but it is used off-label for this condition (Levy et al., 2023; Houri and Hirschfield, 2024; Beuers et al., 2025). IBAT inhibitors in PBC are intended to reduce cholestatic pruritus by blocking ileal reabsorption of BAs; these agents have not shown disease-modifying biochemical benefits comparable to FXR/PPAR agonists and are positioned for symptom control rather than disease-modifying agents (Hegade et al., 2017).

Setanaxib, a selective NADPH oxidase (NOX) 1/4 inhibitor, has shown antifibrotic potential by reducing ROS, inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation, and myofibroblasts transformation in preclinical models (Fiorucci et al., 2024). A phase 2 trial in UDCA non-responders demonstrated reductions in ALP, liver stiffness (via elastography), and fatigue scores (Invernizzi et al., 2023). These promising findings have led to the ongoing phase 2b/3 TRANSFORM trial (NCT05014672) evaluating Setanaxib as an add-on therapy.

Foscenvivint, a selective inhibitor of the cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein/β-catenin interaction, has also demonstrated antifibrotic activity in animal models of cholestatic liver disease (Kimura et al., 2022). Findings from a phase 1 trial suggested that Foscenvivint was well tolerated at the dose of 280 mg/m2/4 h and that it may have antifibrotic effects in advanced PBC (Kimura et al., 2022). Additional trials are required to establish efficacy and long-term safety.

Nanoparticle-based immune modulation represents an emerging therapeutic avenue in PBC. CNP-104, a biodegradable nanoparticle encapsulating the PDC-E2 antigen, is designed to induce antigen-specific immune tolerance by suppressing autoreactive T cells. A phase 2a clinical trial (NCT05104853) is currently underway to evaluate its safety and efficacy (Levy and Bowlus, 2025).

Without effective therapy, PBC can progress to cirrhosis and liver failure, with liver transplantation as the definitive treatment for advanced or decompensated disease (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Sarcognato et al., 2021).

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

PSC is a rare, chronic autoimmune-mediated cholestatic liver disease characterized by fibroinflammatory injury of the biliary tree with multifocal strictures of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts and periductal fibrosis leading to impaired bile flow (Karlsen et al., 2017; Dyson et al., 2018; Cazzagon et al., 2024; Manns et al., 2025). The course of the disease ranges from indolent to progressive cholestasis, often advancing to portal hypertension, cirrhosis, and liver failure (Karlsen et al., 2017; Cazzagon et al., 2024). PSC is also associated with increased risk of colorectal cancer and cholangiocarcinoma (Karlsen et al., 2017; Cazzagon et al., 2024).

While its pathogenesis remains unclear, there also exists a strong association between PSC and IBD with studies reporting that 70%–88% of PSC patients develop comorbid IBD at some point during the disease process (Cariello et al., 2022; van Munster et al., 2024). Conversely, comorbid PSC is only observed in 2%–14% of patients with IBD (van Munster et al., 2024). IBD is characterized by chronic intestinal inflammation with conditions that include diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s Disease. Comorbidity is speculated to be associated with gut microbiome and BA profile alterations that arise due to complications related to defective BA metabolism (Thomas et al., 2022; Leibovitzh et al., 2024). PSC-IBD patients revealed lower levels of secondary conjugated BAs, including DCA and LCA, with a corresponding increase in the abundance of primary BAs compared to patients with IBD alone (Bai et al., 2024). Interestingly, these patients also tended to express milder IBD severity with one study suggesting that PSC may even attenuate the effects of IBD (Bedke et al., 2024). Even more unexpectedly, another study reported that intestinal inflammation actually improved acute cholestatic liver injury and reduced liver fibrosis in chronic colitis mouse models (Gui et al., 2023). PSC livers were also noted in one study to possess comparable levels of VDR expression to controls, suggesting another mechanism of pathology (Kempinska-Podhorodecka et al., 2017). More research is needed to fully elucidate the complicated relationship between these two conditions.

Diagnosis of PSC relies on cholestatic liver biochemistry and characteristic cholangiographic findings, typically in the absence of an identifiable cause (Karlsen et al., 2017; Cazzagon et al., 2024). Cases with known etiologies are classified as secondary sclerosing cholangitis which may arise from choledocholithiasis, recurrent infections, trauma, ischemia, toxic exposures, immunologic conditions, and congenital abnormalities, among others (Dyson et al., 2018; Ludwig et al., 2023).

As in PBC, liver transplantation remains the only definitive treatment for advanced PSC with hepatic decompensation (Karlsen et al., 2017; Dyson et al., 2018; Ludwig et al., 2023). No pharmacologic agent has been proven to significantly increase transplant-free survival (Dyson et al., 2018; Hasegawa et al., 2021). As a result, UDCA remains the most commonly prescribed off-label therapy. Low (13–15 mg/kg/day) and intermediate (17–23 mg/kg/day) doses have demonstrated biochemical improvements in alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), bilirubin, aminotransferases, as well as reduced intestinal ecological disorders and reshaped gut microbiota in IBD (Hasegawa et al., 2021; Cariello et al., 2022; Pan et al., 2024; Manns et al., 2025). High-dose UDCA (≥25 mg/kg/day) by contrast has been associated with increased side effects and is not recommended (Beuers et al., 1992; Manns et al., 2025).

Norucholic acid (NCA), previously known as norUDCA, a side chain–shortened homologue of UDCA, resists taurine and glycine conjugation, allowing for cholehepatic shunting and sustained cycling between hepatocytes and cholangiocytes (Assis and Bowlus, 2023; Bowlus et al., 2023). This promotes bicarbonate-rich, BA-independent bile flow, enhancing choleresis and protecting cholangiocytes with its predominant monomeric secretion augmenting these effects (Fickert et al., 2017; Assis and Bowlus, 2023). NCA also exhibits immunomodulatory activity-suppressing CD8+ T cell activation via mTORC1 inhibition and shows antiproliferative and antifibrotic properties in both preclinical and clinical studies (Assis and Bowlus, 2023). A phase II trial reported significant ALP reductions across all tested doses (500–1,500 mg/day), though adverse effects such as pruritus, fatigue, and nasopharyngitis occurred in all groups (Fickert et al., 2017). A phase III trial is underway to further assess long-term safety and efficacy (NCT03872921).

FXR agonists have shown promise in the management of PSC. OCA demonstrated good tolerability at standard dose (5–10 mg/day) in a phase II trial, resulting in significant ALP reduction. Dose-dependent pruritus was reported as the most common side effect (Kowdley et al., 2020). Cilofexor, a nonsteroidal FXR agonist, was evaluated in a 12-week phase II study in non-cirrhotic PSC patients and showed a 21% reduction in ALP at a dose of 100 mg/day (Trauner et al., 2019).

Emerging therapies such as PPAR agonists, IBAT inhibitors, anti-human CCL24 monoclonal CM-101 antibodies and FGF19 analogues are under active investigation. Elafibranor, in the ELMWOOD trial, was well tolerated and led to significant reductions in ALP and stabilization of fibrosis markers over 12 weeks, supporting further investigation of PPAR agonists as disease-modifying agents (Levy et al., 2025a). Similarly, IBAT inhibitors, including volixibat (NCT04663308) and maralixibat (NCT06553768) are in early-phase trials and their efficacy and safety in PSC remain to be determined. CM-101 antibodies (NCT04595825) are also being explored with a phase II trial revealing that dose-dependent (10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg) treatment was well tolerated and demonstrated anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic and anti-cholestatic effects in individuals with PSC compared to placebo. Another phase II trial demonstrated that aldafermin, an engineered FGF19 analogue, potently suppressed hepatic CYP7A1 activity, leading to reduced BA synthesis and significant improvements in non-invasive biomarkers of fibrosis in PSC patients, although it did not significantly reduce ALP levels (Hirschfield et al., 2019).

Given the progressive fibrotic nature of PSC, antifibrotic agents represent a critical area of therapeutic development. Simtuzumab, a monoclonal antibody against lysyl oxidase-like 2 (LOXL2), failed to show efficacy in a phase II trial in PSC, highlighting the complexity of targeting fibrosis in this disease (Muir et al., 2019). Bexotegrast, a αvβ6/αvβ1 integrin inhibitor, demonstrated a favorable safety profile and preliminary efficacy, including antifibrotic effects, liver function improvement, and symptom reduction (NCT04480840), positioning it as a promising candidate.

Considering the multifactorial nature of PSC pathogenesis, future BA-targeted therapies may benefit from combination approaches. For instance, pairing FXR agonists or NCA with antifibrotic agents like bexotegrast could potentially address both cholestatic and fibrotic components of the disease. Understanding how these agents influence BA signaling pathways, transporter expression, and microbiome interactions will be critical to optimizing therapeutic strategies.

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP)

ICP is the most common pregnancy-specific liver disorder, typically presenting in the second or third trimester. It is characterized by pruritus, elevated liver enzymes, and increased total BA (TBA) levels (Lee et al., 2021; Tang et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2024). Severity is stratified by third-trimester TBA levels: mild ICP is defined as 10–39 μmol/L and severe ICP as ≥ 40 μmol/L (Tang et al., 2024). Although ICP usually resolves postpartum and poses minimal risk to the pregnant individual, it has been associated with increased rates of postpartum hemorrhage, hepatobiliary malignancy, and immune or cardiovascular diseases (Tang et al., 2024). Importantly, it also poses significant fetal risk, including preterm labor, meconium-stained amniotic fluid, and intrauterine fetal demise, particularly when TBA levels exceed 100 μmol/L (Smith and Rood, 2020; Lee et al., 2021; Ovadia et al., 2021). The pathophysiology of ICP remains poorly understood, although evidence suggests that changes in the gut microbiome and genetic predisposition may play a role in its development (Pataia et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2023).

UDCA is the standard first-line, off-label treatment for ICP (Smith and Rood, 2020; Walker et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). Dosing typically ranges from 10–15 mg/kg/day, with escalation up to 21 mg/kg/day in refractory cases (Lee et al., 2021; Kothari et al., 2024). UDCA has been shown to reduce pruritus and improve serum liver tests compared to controls and alternative treatments (Pataia et al., 2017; Walker et al., 2020; Lee et al., 2021). However, its effectiveness in preventing adverse perinatal outcomes remains inconsistent across studies (Kong et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2020; Jiang et al., 2021). UDCA is generally well tolerated by both the mother and fetus with few reported adverse effects beyond nausea and emesis (Kong et al., 2016; Walker et al., 2020). Notably, one study reported enhanced improvements in pruritus and liver parameters when UDCA was co-administered with traditional Chinese medicines such as A. capillaris Thunb, Gardenia, and Rhubarb (Jiang et al., 2021). Further studies are needed to explore the mechanisms and clinical relevance of such combination therapies.

Pediatric cholestatic diseases

Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC)/Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC)

PFIC comprises a group of rare, autosomal recessive cholestatic liver diseases that typically present in infancy or early childhood and are characterized by progressive defects in bile production and transport (Gunaydin and Bozkurter Cil, 2018; Vinayagamoorthy et al., 2021; McKiernan et al., 2023). The main subtypes PFIC1, PFIC2, and PFIC3 result from mutations in genes encoding hepatocanalicular transporters essential for bile formation and flow (van der Woerd et al., 2017). In contrast, BRIC is a milder, non-progressive phenotype caused by mutations in the same genes as PFIC1 and PFIC2, and is characterized by intermittent cholestasis with complete resolution between episodes (van der Woerd et al., 2017).

Mutations in ATP8B1 (PFIC1/FIC1 deficiency) and ABCB11 (PFIC2/BSEP deficiency) may cause either BRIC1/BRIC2 or progressive cholestasis with severe pruritus (Baker et al., 2019; Hassan and Hertel, 2022). PFIC2 has an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma (McKiernan et al., 2023). Mutations in ABCB4 (PFIC3/MDR3 deficiency) are associated with progressive cholestasis, moderate to severe pruritus, extrahepatic manifestation, and increased risk of hepatobiliary malignancies (Baker et al., 2019; Hassan and Hertel, 2022). If untreated, all PFIC subtypes can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ESLD (Hassan and Hertel, 2022).

Maralixibat and odevixibat, both IBAT/ASBT inhibitors, are FDA-approved for the treatment of pruritus in PFIC and have shown significant reductions in both pruritus and serum BA levels (Thompson et al., 2022; Miethke et al., 2024). UDCA (10–30 mg/kg/day) remains the off-label drug of choice for PFIC3 and is often used in combination with rifampin and/or cholestyramine to improve bile flow and manage pruritus, though evidence for synergistic benefits is limited (van der Woerd et al., 2017; Gunaydin and Bozkurter Cil, 2018). UDCA is most effective in patients with ABCB4 missense mutations or MDR3 monoallelic-deficient grafts, while those with nonsense mutations and absent MDR3 expression are typically unresponsive (Gunaydin and Bozkurter Cil, 2018). Selected cases of PFIC1/BRIC1 and PFIC2/BRIC2 may also benefit symptomatically, though evidence remains inconsistent (van der Woerd et al., 2017). Prior to the IBAT inhibitor era, many PFIC1 and PFIC2 patients required surgical interventions, including partial external biliary diversion or liver transplantation (van der Woerd et al., 2017; McKiernan et al., 2023).

Therapeutic strategies for newly identified subtypes–PFIC4, PFIC5, and PFIC6 – are still under investigation. PFIC5, caused by mutations in NR1H4 encoding FXR, may be a candidate for OCA therapy, although no formal clinical trials have been conducted to date (Beuers et al., 2025). The efficacy of NCA observed in PSC suggests it may also offer enhanced therapeutic benefits across all PFIC and BRIC subtypes, but requires further validation (Stapelbroek et al., 2010).

Alagille syndrome (ALGS)

ALGS is a multisystem, autosomal dominant disorder commonly associated with intrahepatic bile duct paucity due to mutations in the JAG1 or NOTCH2 genes (Turnpenny and Ellard, 2012; Sutton et al., 2024). These genes encode key components of the Notch signaling pathway, essential for intrahepatic bile duct development (Turnpenny and Ellard, 2012; Kohut et al., 2021; Heinz and Vittorio, 2023; Sutton et al., 2024). Disruption of this pathway can cause a wide range of clinical manifestations, including cholestatic liver disease, cardiac, renal, vascular, skeletal and ocular anomalies, as well as characteristic facial features (Mitchell et al., 2018; Kohut et al., 2021; Ayoub et al., 2023). Diagnosis is often challenging due to variable phenotypes and incomplete penetrance, frequently requiring genetic confirmation (Ayoub et al., 2023). The incidence is estimated at approximately 1 in 30,000 live births (Mitchell et al., 2018; Kohut et al., 2021; Ayoub et al., 2023). While overall survival into adulthood approaches 90%, only 24%–40.3% retain their native liver (Kamath et al., 2020; Ayoub et al., 2023; Vandriel et al., 2023).

Early diagnosis improves native liver survival with genetic testing for JAG1 and NOTCH2 mutations being the gold standard (Fligor et al., 2022; Heinz and Vittorio, 2023). However, when genetic testing is unavailable or delayed, liver biopsy combined with syndromic features helps differentiation from biliary atresia (Kohut et al., 2021). Correct diagnosis is critical, as inappropriate Kasai procedures in ALGS patients have been linked to clinical deterioration (Kaye et al., 2010).

The heterogeneous clinical presentation and multisystem involvement of ALGS pose challenges for standardized treatment approach. Effective management requires comprehensive nutritional and medical support alongside pharmacological therapy (Cheng and Rosenthal, 2023). Odevixibat and maralixibat are FDA-approved for severe pruritus in children ≥12 months and ≥3 months of age, respectively. UDCA (10–20 mg/kg/day) has historically been used to manage cholestasis and pruritus, though evidence for efficacy is limited (Kohut et al., 2021; Ayoub and Kamath, 2022). UDCA can be used alone or combined with cholestyramine, rifampin, or naltrexone to improve symptom control (Turnpenny and Ellard, 2012). Liver transplantation remains the definitive treatment for advanced disease.

Biliary atresia

Biliary atresia is a progressive inflammatory and fibrosclerosing cholangiopathy that represents the most common cause of neonatal cholestasis and the leading indication for pediatric liver transplantation (Chung et al., 2020; Antala and Taylor, 2022). It is frequently misdiagnosed as ALGS due to overlapping clinical features such as neonatal jaundice with elevated GGT and histological similarities including giant cell hepatitis and ductular proliferation (Kohut et al., 2021; Ayoub and Kamath, 2022). If untreated, biliary atresia rapidly progresses to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and ESLD, with liver transplantation required in patients who do not respond to early surgical intervention (Chung et al., 2020; Antala and Taylor, 2022).

Early surgical treatment with hepatic portoenterostomy (Kasai procedure) within the first 60 days of life is associated with the most favorable long-term outcomes (Heinz and Vittorio, 2023). Post-Kasai, treatment with UDCA (10–15 mg/kg/day) has been shown to significantly improve serum bilirubin clearance and reduce TBA levels compared to controls; however, survival benefit remains unclear (Qiu et al., 2018). In one study of stable post-Kasai patients, UCDA discontinuation led to worsening liver enzyme profiles, which was reversed upon reintroduction. Despite no significant changes in clinical status such as pruritus, bacterial cholangitis, or hepatomegaly, suggesting a beneficial role in maintaining biochemical stability (Willot et al., 2008). By contrast, a retrospective study from Egypt involving 141 infants reported worse outcomes in those treated with UDCA, though this likely reflected the overall poor prognosis of the cohort, with UDCA possibly used as a last resort therapy in severely affected cases (Table 2) (Kotb, 2008).

TABLE 2

| Approval status | Combination/Monotherapy | Therapeutic use | Adverse effects | Typical dosage range | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-BA FDA approved agents | Seladelpar (PPAR-δ agonist) ± UDCA |

|

Headache, abdominal pain, nausea, abdominal distention, dizziness |

|

Abuelazm et al. (2025) |

| Elafibranor (PPAR α/δ agonist) ± UDCA |

|

Weight gain/loss, abdominal pain, NVD, arthralgia, constipation, muscle injury, GERD, dry mouth, rash |

|

Ergenc and Heneghan (2025), Levy et al. (2025b) | |

| Maralixibat (IBAT inhibitor) |

|

NVD, abdominal pain, fat-soluble vitamin deficiency, liver test abnormalities, GI bleeding, bone fractures |

|

Garcia, Hsu and Lin (2023), Miethke et al. (2024) | |

| Odevixibat (IBAT inhibitor) |

|

Liver test abnormalities, NVD, abdominal pain, fat-soluble vitamin deficiency |

|

Thompson et al. (2022), Ovchinsky et al. (2024) | |

| Cholestyramine |

|

Constipation, NVD |

|

Kremer et al. (2008), Patel et al. (2019) | |

| Resmetirom (THR-β agonist) |

|

NVD, pruritus, constipation, abdominal pain, dizziness |

|

Keam (2024) | |

| Colesevelam (BA sequestrant) |

|

Constipation, dyspepsia, nausea |

|

Hansen et al. (2017) |

Therapeutic applications, safety profile, dosage ranges, and regulatory status of current bile acid (BA) combination therapies.

This table summarizes the current commonly used indications and investigational therapeutic uses, reported adverse effects, typical dosage ranges for BA-involved combination therapies. References correspond to key supporting literature. NVD = nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.

Other diseases

Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)/Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH)

BA metabolism is markedly disrupted in MASLD and MASH, with characteristic changes in BA synthesis, pool composition, hydrophobicity, and receptor-mediated signaling (Arab et al., 2018). These alterations contribute to steatosis, inflammation, and fibrogenesis, positioning the FXR/FGF19 axis and enterohepatic BA circulation as central therapeutic targets (Simbrunner et al., 2025; Steinberg et al., 2025). Despite strong mechanistic rationale, no BA-directed therapy has yet achieved regulatory approval for MASLD/MASH.

FXR agonists represent the most extensively studied BA-derived approach. OCA demonstrated improvements in hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in early trials, but its development was ultimately discontinued after failing to meet histologic endpoints and due to concerns about pruritus and dyslipidemia in Phase III studies (Neuschwander-Tetri et al., 2015; Younossi et al., 2019). These limitations prompted the advancement of non-steroidal FXR agonists, which were designed to preserve FXR-mediated metabolic and antifibrotic activity while reducing BA-driven adverse effects. Cilofexor produced meaningful reductions in liver fat and aminotransferases, with additive benefits observed in combination studies using firsocostat ± semaglutide (Patel et al., 2020; Alkhouri et al., 2022). Tropifexor similarly reduced liver fat and ALT but remained limited by pruritus and LDL elevations (Sanyal et al., 2023). Additional agents, including vonafexor, TERN-101, and PX-104, have shown early biochemical improvements, whereas EDP-305 and nidufexor were discontinued due to safety concerns and strategic reprioritization, respectively (Fiorucci et al., 2020; Prikhodko et al., 2022; Ratziu et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2024).

Beyond FXR, the BA-responsive receptor TGR5 remains an attractive target. Selective TGR5 agonists such as INT-777 and dual FXR/TGR5 agonists such as INT-767 exhibit potent anti-steatotic and antifibrotic effects in preclinical models (Hodge and Nunez, 2016). However, their clinical translation has been limited by gallbladder filling, cholestasis, and species-dependent receptor expression patterns (Jin et al., 2024).

Additional BA-derived agents have demonstrated potential complementary benefits. NCA has shown improvements in aminotransferases, steatosis, and liver stiffness in Phase II studies, and its histologic efficacy is being further evaluated in the OASIS trial (NCT05083390). Conventional UDCA lowers ALT and GGT but does not significantly improve histology in MASLD/MASH (Lin et al., 2022). TUDCA has demonstrated robust cytoprotective effects in preclinical settings, though these findings have not been confirmed in controlled clinical trials (Wang et al., 2024).

Aramchol, a bile acid–fatty acid conjugate that inhibits stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), has shown meaningful reductions in liver fat and favorable metabolic effects in Phase II studies (Safadi et al., 2014). Although the ARREST Phase IIb trial did not meet its primary endpoint, trends toward MASH resolution, fibrosis improvement, and improved liver enzymes supported its advancement into the Phase III ARMOR program (Ratziu et al., 2021). In this ongoing trial, the optimized 300 mg BID dose has demonstrated promising antifibrotic activity based on conventional histology, paired-ranked reads, and AI-assisted digital pathology (Ratziu et al., 2025).

Aldafermin, an engineered analogue of FGF19, leads to rapid and substantial reductions in liver fat and improvements in circulating biomarkers of steatohepatitis and fibrosis (Harrison et al., 2021). Although it did not meet its primary histologic endpoint in patients with compensated cirrhosis, consistent improvements in non-invasive fibrosis measures were observed (Rinella et al., 2024). Because of theoretical risks related to FGF19-associated mitogenicity, long-term monitoring remains important (Ursic-Bedoya et al., 2024).

Agents that modulate enterohepatic BA circulation offer a more indirect therapeutic approach. ASBT/IBAT inhibitors reduce BA pool size and hepatic exposure, but the most advanced agent, volixibat, failed to meet prespecified MRI-PDFF and ALT efficacy thresholds and was discontinued (Salic et al., 2019; Newsome et al., 2020). Additional approaches, including BA sequestrants and microbiome-targeted therapies that reshape BA composition and influence FXR/TGR5 signaling, have shown encouraging effects in preclinical models but have not yet been studied in MASLD/MASH clinical trials (Takahashi et al., 2020; Duarte et al., 2025).

Non BA-directed therapies highlight the need for multi-pathway approaches in MASH. The THR-β agonist resmetirom, now FDA-approved for noncirrhotic MASH with fibrosis, produces substantial reductions in liver fat and steatohepatitis (Harrison et al., 2024; Targher et al., 2025). Additional late-stage investigational candidates include the GLP-1 receptor agonist semaglutide, the pan-PPAR agonist lanifibranor, the FGF21 analogues efruxifermin and pegozafermin, the fatty acid synthase inhibitor denifanstat, and survodutide, a dual glucagon/GLP-1 receptor agonist (Israelsen et al., 2024). Together, these therapies reflect the complex metabolic, inflammatory, and fibrotic pathways underlying MASH and support the rationale for combination strategies that integrate BA-directed, metabolic, and antifibrotic mechanisms.

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)

T2DM is the common, insulin-resistant variant of diabetes mellitus that is commonly associated with obesity, fatty liver disease, cardiovascular issues and presents a major crisis for human health (Nauck et al., 2021). As more research is being conducted on the role of BAs in insulin signaling, energy metabolism and glucose tolerance, BAs have become a promising therapeutic target in the treatment of T2DM.

BA sequestrants, such as colesevelam, are FDA-approved for T2DM and have demonstrated clinically meaningful reductions in HbA1c in meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials, with additional benefits for lipid profiles (Sonne et al., 2014; Hansen et al., 2017). The mechanism is thought to involve modulation of BA signaling through FXR and TGR5, which impacts glucose metabolism and GLP-1 secretion (Sonne et al., 2014).

Novel BA derivatives, such as berberine ursodeoxycholate (HTD1801), have shown promise in recent phase II randomized clinical trials (NCT06411275). HTD1801, an ionic salt of berberine and UDCA, led to significant reductions in HbA1c and improvements in glycemic, cardiometabolic, and liver-related parameters over 12 weeks, with a favorable safety profile (Ji et al., 2025). These effects are attributed to AMP kinase activation, NLRP3 inflammasome inhibition, and improved insulin sensitivity (Ji et al., 2025).

Another recent study identified MABAs as promising clinical markers of glycemic control (Lin et al., 2025). Tryptophan-conjugated CA (Trp-CA) was markedly reduced in patients with T2DM compared with healthy controls, and its administration improved glucose tolerance in diabetic mice (Lin et al., 2025). The GPCR MRGPRE was subsequently identified as the receptor mediating these metabolic effects (Lin et al., 2025). These findings suggest that Trp-CA–MRGPRE signaling may represent a novel therapeutic avenue for T2DM.

Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating additional BA-based therapies, including FXR and TGR5 agonists, and agents that modulate BA transport. Multiple trials on the efficacy and safety of UDCA in T2DM (NCT01337440, NCT05416580, NCT02033876) revealed that treatment resulted in a reduction of HbA1c levels, increased GLP-1 secretion, glucose homeostasis and showed beneficial effects on metabolic and oxidative stress parameters (Shima et al., 2018; Calderon et al., 2020; Lakić et al., 2024). Additional studies (NCT05902468) further exploring UDCA’s therapeutic potential in T2DM are currently underway.

Trials on TUDCA (NCT00771901, NCT03331432) revealed improvements to insulin action and vascular function in participants through the modulation of obesity-related insulin resistance and inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress (Amen et al., 2019). A phase II study of OCA (NCT00501592) revealed that a 25–50 mg treatment over 6 weeks led to improved insulin sensitivity, minor loss of body weight and enhanced FGF19 levels in the serum in patients with T2DM and MASLD (Mudaliar et al., 2013). These approaches aim to leverage the hormonal and signaling properties of BAs to improve glucose homeostasis, insulin sensitivity, and reduce inflammation.

Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX)

CTX is a rare, autosomal recessive disorder of BA synthesis and lipid storage caused by pathogenic mutation to the CYP27A1 gene (DeBarber and Duell, 2021; Islam, Hoggard and Hadjivassiliou, 2021). This leads to reduced levels of primary BAs, particularly CDCA, which in turn disrupts the normal negative-feedback regulation of CYP7A1, allowing for a toxic build up of intermediate metabolites, such as cholestanol, to accumulate in various tissues (Mandia et al., 2019; DeBarber and Duell, 2021; Duell et al., 2023). These deposits commonly aggregate in the central nervous system (CNS), namely the cerebellum, as well as tendons and the lenses of the eyes (Islam et al., 2021). Disease progression can manifest into severe neurocognitive impairment, Parkinsonism, peripheral neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia, dementia, behavioral and psychiatric disturbances, seizures, chronic diarrhea, early onset cataracts and tendon xanthomata if left untreated (Islam et al., 2021; Nóbrega et al., 2022; Kisanuki et al., 2025).

The FDA and European Medicines Agency have approved CDCA for treatment of CTX in adults (Bouwhuis et al., 2023; Jalal et al., 2025). Administration of 250 mg PO TID is generally well tolerated and has been reported to improve neurologic manifestations, slow disease progression and decrease all CTX biomarkers (Nóbrega et al., 2022; Kisanuki et al., 2025). A randomized CDCA withdrawal study on patients with CTX revealed significant increases in metabolite biomarkers when treatment with CDCA was not administered, with 61% of placebo participants requiring rescue medication (Kisanuki et al., 2025). Despite this, around 20% of patients who are administered CDCA for CTX continue to show signs of deterioration, in which case, CA may be utilized as an adjunctive or alternative therapy (Mandia et al., 2019; Nóbrega et al., 2022). Efficacy of CA is noted to significantly reduce cholestanol levels in all patients with no adverse effects reported in one study (Mandia et al., 2019). CDCA treatment does not typically reduce tendon xanthomas nor improve cataracts in patients with CTX and is currently contraindicated for use during pregnancy (Nóbrega et al., 2022). However, one case series of 19 pregnancies noted that no complications were reported in newborns delivered by CDCA-treated birth parents postterm (Duell et al., 2023; Zaccai et al., 2024). CDCA is not currently FDA-approved for usage in pediatric individuals although the current recommended dosing is 5–15 mg/kg/day (Table 3) (Nóbrega et al., 2022).

TABLE 3

| Categorization | Disease | Prevalence | BAs/BA derivatives used | Reported efficacy | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult cholestatic disorder | Primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) | ∼1.9–40.9 per 100,000 | UDCA, OCA (second-line) | UDCA improves transplant-free survival; OCA effective in UDCA non-responders | Levy et al. (2025a) |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) | ∼11.6 per 100,000 | UDCA, OCA, NCA (investigational) | Mixed results; UDCA improves biochemistry but no survival benefit; NCA promising in trials | Cooper et al. (2022) | |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) | ∼200–300 per 100,000 pregnancies | UDCA | Effective for maternal symptom relief and biochemical improvement; fetal outcome benefit uncertain | Sadeghi (2024) | |

| Pediatric cholestatic disorder | Progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) | ∼1 per 50,000–100,000 | UDCA (Particularly PFIC3) | Minimal in PFIC1/2; beneficial in PFIC3 with select genotypes (e.g., missense ABCB4) | Mighiu et al. (2022) |

| Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) | ∼1 per 50,000–100,000 | UDCA | Symptom relief in some patients; variable response between episodes | Daniel et al. (2022) | |

| Alagille syndrome | ∼3 per 100,000 live births | UDCA | Limited efficacy; may reduce pruritus and improve biochemistry in some cases | Kohut et al. (2021) | |

| Biliary atresia | ∼5 per 100,000 live births | UDCA | Adjunctive post-Kasai; improves biochemistry but unclear survival benefit | Hartley et al. (2009) | |

| Other diseases | Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)/Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis (MASH) | ∼15,000 per 100,000 | UDCA, OCA (investigational) | Limited efficacy, UDCA lowers ALT and GGT but not histology, OCA failed to meet histological endpoints in phase III trials | Huang et al. (2025) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | ∼11 per 100,000 | UDCA | Limited efficacy; reshapes the gut microbiome | Lewis et al. (2023), Caron et al. (2024) | |

| Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis (CTX) | ∼1 per 75,000–150,000 | CDCA | Effective in controlling abnormal biomarkers and avoiding disease progression | Mandia et al. (2019), Kisanuki et al. (2025) | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) | ∼6,000–7,000 per 100,000 | UDCA, TUDCA, OCA (investigational) | Limited efficacy; may help to control glucose metabolism and support altered BA profile | Khan et al. (2020) |

Cholestatic and non-cholestatic disease prevalence profile, recommended therapeutic bile acid (BA) agent and efficacy.

This table summarizes the approximate prevalence of the various cholestatic and non-cholestatic disorders. Efficacy is provided based on clinical trial data from the listed BAs.

Future considerations

The therapeutic potential of BAs extends far beyond classical roles in hepatic and metabolic regulations. Two particularly promising areas for future exploration are the neuroprotective properties of hydrophilic BAs and the expanding use of BA-stabilized vesicular systems (bilosomes) for targeted drug and vaccine delivery.

BAs in neuroprotection

Hydrophilic BAs, notably UDCA and its conjugates GUDCA and TUDCA, are increasingly recognized for their neuroprotective properties in models of neurological, neurodegenerative, and neuropsychiatric diseases (Zangerolamo et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022a; Khalaf et al., 2022). Conjugated BAs require active transport into the brain although lipophilic, unconjugated BAs, such as CDCA, are capable of crossing the BBB from peripheral circulation through passive diffusion and exert cytoprotective effects through multiple mechanisms (Mulak, 2021; Zangerolamo et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022a; Khalaf et al., 2022; Xing et al., 2023). Additionally, they serve as chemical chaperones that support proper protein folding and stability, which is crucial in diseases involving protein misfolding and aggregation (Zangerolamo et al., 2021; Khalaf et al., 2022; Xing et al., 2023).

Preclinical studies demonstrate that UDCA reduces neuronal apoptosis, ROS, and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in models of neurodegeneration, while GUDCA and TUDCA exhibit similar neuroprotective effects across neurological and neuropsychiatric models (Zangerolamo et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2022a). Their therapeutic potential appears to be disease-specific. For instance, all three have shown benefit in Huntington’s disease models, while UDCA and TUDCA are more effective in Parkinson’s (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) models, and GUDCA in bilirubin encephalopathy (Huang et al., 2022a).

Beyond their direct neuroprotective actions, BAs influence the microbiota-gut–brain axis. Recent animal studies demonstrate that disruptions in the gut microbiota can actively contribute to neurodegenerative disease by reshaping and promoting microglial behavior and activation which, in conjunction with neuroinflammatory responses, are central features of many neurodegenerative disorders (Sampson et al., 2016; Burberry et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2023; Loh et al., 2024). Although microglial cells exhibit phagocytic properties to eliminate protein aggregates in the brain, excessive uptake of such compounds can lead to neuroinflammation, phagocytic impairment and eventual neurodegeneration (Gao et al., 2023). Because microbial metabolites and signaling pathways exert powerful control over glial activity, the microbiota–gut–brain axis has emerged as a compelling therapeutic target for slowing or modifying the course of neurodegeneration (Cook and Prinz, 2022; Loh et al., 2024).

Importantly, gut microbes modify BA composition through biotransformation, while BAs shape the gut microbial community. Disturbances to bacterial BS hydrolases, which generate deconjugated BAs that are less toxic to the gut microbiota, reshape the BA profile in both the serum and brain, ultimately affecting signaling within the CNS (Wu et al., 2024a). These bidirectional interactions regulate metabolic and signaling pathways that impact neuroinflammation and immune responses relevant to neurodegeneration, and CNS health (Mulak, 2021; Wang et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2024b). Alterations in BA profiles and gut microbiota composition have been observed in AD and underscored by the aforementioned CTX, implicating GLBA crosstalk in neurodegeneration pathophysiology (Mulak, 2021; Wang et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2024b).

In AD, amyloid β (Aβ) plaques and Tau protein aggregates within neurons remain the most recognized biomarkers of disease progression (Wu et al., 2024b). Aβ exposure has been found to activate the early stress c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway which eventually induces apoptosis (Viana et al., 2010). Microtubule affinity–regulating kinase (MARK4), whose overexpression in AD induces synaptic and dendritic spine defects, is also associated with increases in Tau phosphorylation, leading to aggregates (Anwar et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2024b). In terms of BA profiles, LCA-CA and DCA-CA ratios are significantly elevated in reporting studies, with microbiota-derived glyco-DCA/LCA and tauro-LCA also showing significant increases and being associated with reduced cognitive outcomes in patients with AD (Pan et al., 2017; MahmoudianDehkordi et al., 2019).

Therapeutically, CA has been shown to inhibit the Tau phosphorylation activity of MARK4, thereby reducing cognitive deficits and neuronal lesions (Anwar et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2024b). Other MARK4 inhibitors such as donepezil and rivastigmine tartrate are currently undergoing research to explore similar therapeutic potential with promising results (Shamsi et al., 2020). TUDCA attenuates Aβ toxicity by dampening JNK-driven stress signaling, stabilizing mitochondrial membranes, and limiting activation of pro-apoptotic cascades (Wu et al., 2024b). Because clinical antibody therapies against Aβ have shown only modest benefit, these BA-mediated mechanisms offer a complementary therapeutic avenue targeting both Aβ and Tau pathology (Asher and Priefer, 2022). A current phase II trial is underway to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a combination therapy of TUDCA and sodium phenylbutyrate in patients with AD (NCT03533257).

PD by contrast, is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by the progressive loss of catecholamines and cholinergic neurons in conjunction with Lewy body formations composed of aggregated α-synuclein deposits (Hurley et al., 2022). Both UDCA and TUDCA have been observed to inhibit neuroinflammation and reduce glial activity in PD mouse models (Loh et al., 2024). Two recent clinical trials (NCT02967250, NCT03840005) that further evaluate the efficacy of UDCA in PD found that high-dose administration (30 mg/kg/day) was well tolerated in early PD (Payne et al., 2023). Treatment with dioscin, a TGR5 agonist, displayed increased GLP-1 activation and improvements to motor function in mouse models (Sun et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2023; Loh et al., 2024). GLP-1 activity enhances insulin secretion, lowering serum levels of glucose which lead to reduced levels of glial activity (Sun et al., 2021; Mao et al., 2023; Nowell et al., 2023). Co-administration of UDCA and dioscin was shown to enhance the neuroprotective properties of either drug by itself.

Several studies report elevated circulating secondary BAs such as DCA, LCA, and HDCA, and variable but notable changes in primary BAs (Yakhine-Diop et al., 2020; Li et al., 2021; Shao et al., 2021; Hurley et al., 2022). Some studies identify increased plasma CA and elevated glycine- or taurine-conjugated primary BAs, whereas others report reduced glycocholic acid and glycochenodeoxycholic acid in the frontal cortex, highlighting tissue-specific differences that may reflect distinct pathogenic mechanisms (Yakhine-Diop et al., 2020; Shao et al., 2021; Hurley et al., 2022; Kalecký and Bottiglieri, 2023). PD patients and prodromal PD mouse models also show reduced levels of the neuroprotective BAs UDCA and TUDCA, suggesting impaired BA-mediated cytoprotection (Graham et al., 2018; Shao et al., 2021). Additional evidence, including the increased PD risk after cholecystectomy and secondary BA elevations following gut microbiota transfer, supports a role for altered BA signaling within the GLBA in early PD pathogenesis (Kim et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2023).

Despite promising preclinical data, further research is needed to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of BA signaling within the CNS, optimize pharmacokinetics and dosing strategies, and establish efficacy and safety through large-scale clinical trials. Harnessing the neuroprotective and immunomodulatory effects of BAs may open new avenues for treating neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders, particularly when integrated with targeted delivery systems such as bilosomes.

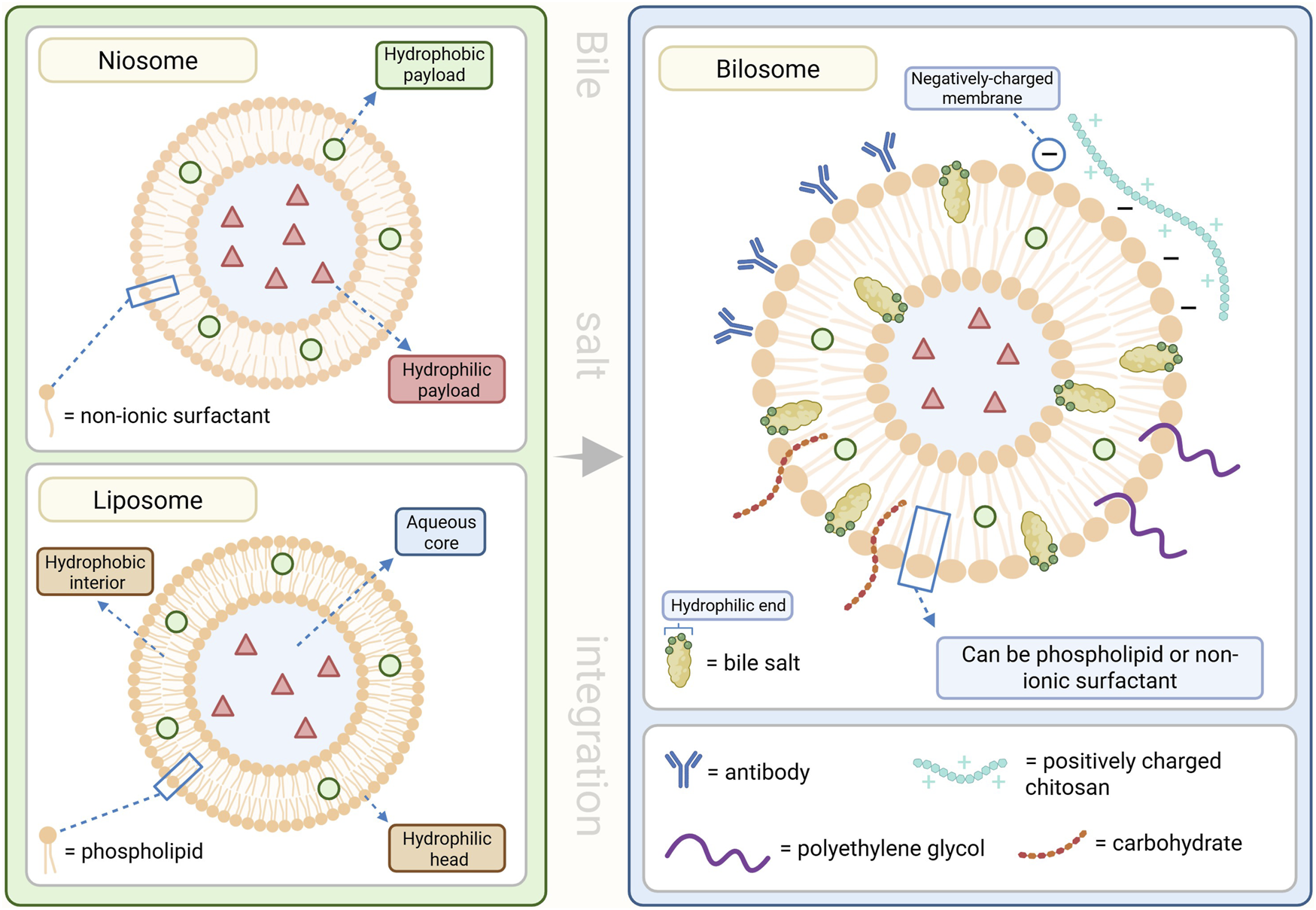

BA-based nanocarriers

Bilosomes are BA-stabilized vesicular systems composed of non-ionic surfactants (niosomes), phospholipids (liposomes), and amphiphilic BSs, which confer superior stability, deformability, and protection against enzymatic and acidic degradation compared to conventional liposomes and niosomes (Mitrović et al., 2025). The integration of BSs into the bilayer enhances vesicle integrity in the gastrointestinal tract, promotes mucosal penetration, and facilitates absorption, resulting in increased oral bioavailability of peptides, proteins, and other labile molecules (Aburahma, 2016; Nayak et al., 2023; Mitrović et al., 2025).

Bilosome-based delivery systems demonstrate remarkable versatility across multiple non-invasive administration routes. Surface-modification of bilosomes enhance cell surface receptor identification and ligand detection to allow for improved targeting efficiency and drug delivery to a diverse number of pathologies (Nayak et al., 2023; Priya et al., 2023; Mitrović et al., 2025). In oral drug delivery, bilosomes protect encapsulated agents from gastrointestinal deposition and enhance intestinal absorption (Aburahma, 2016; Nayak et al., 2023; Mitrović et al., 2025). For oral vaccines, bilosomes facilitate efficient antigen uptake via Peyer’s patches, leading to robust mucosal and systemic immune responses, with efficacy demonstrated in preclinical and early clinical studies (Wilkhu et al., 2013; Shukla et al., 2016). For transdermal administration, the ultra-deformable properties of bilosomes allow traversal of the stratum corneum, significantly improving skin penetration and drug deposition (Nayak et al., 2023; Mitrović et al., 2025). In ocular applications, bilosomes enhance corneal permeation, prolong retention time, and improve stability, resulting in better therapeutic availability for ophthalmic conditions (Nayak et al., 2023; Rajbhar et al., 2025). Intranasally, bilosomes protect encapsulated agents from enzymatic degradation, increase mucosal adhesion, and facilitate direct nose-to-brain transport, offering a promising strategy for CNS-targeted therapies and vaccines (Mitrović et al., 2025).

In the context of hepatobiliary diseases, bilosome-based formulations have shown promise in improving the delivery and therapeutic efficacy of agents such as daclatasvir, sofosbuvir, silymarin, and pitavastatin, as well as bioactive polysaccharides th anti-hepatocarcinogenic activity (Matloub et al., 2018; Joseph Naguib et al., 2020; El-Nabarawi et al., 2021). Studies demonstrate that bilosome encapsulation can enhance hepatic targeting, increase drug bioavailability in the liver, and improve pharmacodynamic outcomes in models hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma (Matloub et al., 2018; Joseph Naguib et al., 2020; El-Nabarawi et al., 2021).